Summary

The Bactrian camel includes various domestic (Camelus bactrianus) and wild (Camelus ferus) breeds that are important for transportation and for their nutritional value. However, there is a lack of extensive information on their genetic diversity and phylogeographic structure. Here, we studied these parameters by examining an 809‐bp mtDNA fragment from 113 individuals, representing 11 domestic breeds, one wild breed and two hybrid individuals. We found 15 different haplotypes, and the phylogenetic analysis suggests that domestic and wild Bactrian camels have two distinct lineages. The analysis of molecular variance placed most of the genetic variance (90.14%, P < 0.01) between wild and domestic camel lineages, suggesting that domestic and wild Bactrian camel do not have the same maternal origin. The analysis of domestic Bactrian camels from different geographical locations found there was no significant genetic divergence in China, Russia and Mongolia. This suggests a strong gene flow due to wide movement of domestic Bactrian camels.

Keywords: Camelus bactrianus, Camelus ferus, mitochondrial DNA, phylogeography

The Bactrian camel is adapted to the specific weather conditions of both desert and semi‐desert regions and is an important livestock species in many areas. The Bactrian camel's wool, meat and milk are all useful products, the latter two especially due to their high nutritional value. In addition, these camels are used as transportation within small, remote regions.

The domestic Bactrian camel is distributed mainly in central Asian countries, including Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, North Eastern Afghanistan, Russia and Uzbekistan (Mirzaei 2012; Vyas et al. 2015). In addition, it is also found in north Pakistan (Isani & Baloch 2000), Iran, Turkey (Moqaddam & Namaz‐Zadeh 1998) and India (Vyas et al. 2015). In China, the domestic Bactrian camels are distributed mainly in Inner Mongolia, Xinjing, Qinghai and Gansu, and there are six breeds of Bactrian camel currently recognized: the Alashan, Sunit, Qinghai, Tarim, Zhungeer and Mulei (Jirimutu et al. 2009). The domestic Bactrian camel population of Mongolia is distributed mainly in the following regions: Umnegobi, Dornogobi, Dundgobi, Bayankhongor, Gobi‐Altai, Khovd, Uvs and Uvurkhangai (Temuulun et al. 2013). There are three breeds recognized: the Hos Zogdort, Galbiin Gobiin Ulaan and Haniin Hetsiin Huren (Saipolda 2004). The Russian Kalmyk Bactrian camel is found mainly in and around the Astrakhan province. Most of the extant wild Bactrian camels are distributed in the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Areas in Mongolia, with an estimated population size of 350 to 1950 (Hare 1997; Reading et al. 2005; Dovchindorj et al. 2006).

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has been used to determine the genetic diversity and phylogeography of many animals such as goats (Chen et al. 2005), cattle (Lai et al. 2006) and pigs (Yang et al. 2003). Although these parameters have been studied in domestic Mongolian Bactrian camels (Chuluunbat et al. 2014), they are not yet well understood in Bactrian camels from wider geographical locations. In the present study, we investigated the 809‐bp mtDNA fragment nucleotides 15120–15928 (accession no. NC_009628.2) in 113 individuals from seven Chinese breeds, three Mongolian breeds, one Russian breed, one wild breed and two hybrid individuals to investigate the genetic diversity and phylogeography of Bactrian camel populations.

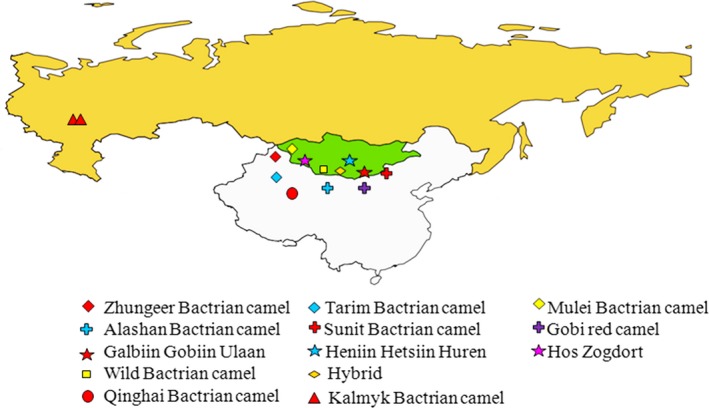

Blood or ear samples from 92 domestic Bactrian camels (Camelus bactrianus) representing 11 domestic breeds were collected from China, Mongolia and Russia (Fig. 1, Table S1). Ear samples were collected from 19 wild Bactrian camels (Camelus ferus) and two hybrid Bactrian camel samples in the Gobi‐Altai province of Mongolia (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the domestic and wild Bactrian camel samples analysed in this study.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from ear samples using a standard phenol–chloroform extraction method and from blood samples using a QIAmp DNA kit (Qiagen). Detailed information on the breeds, geographic regions and sample sizes is given in Table 1. In all, 809 bp of mtDNA (nucleotides 15120–15928; accession no. NC_009628.2) from 113 individuals were sequenced in both directions with two overlapping primer pairs (Silbermayr et al. 2010) on a MegaBACE 1000 sequencing system. The amplicons were aligned to reference sequence NC_009628.2 using codoncode aligner (version 3.0.2).

Table 1.

The geographic regions, sample sizes, numbers of haplotypes, haplotype diversity, and nucleotide diversity for each Bactrian camel breed

| Geographical region | Breed | Geographic distribution | Number of individuals | Haplotypes | Haplotype diversity (Hd) | Nucleotide diversity (π) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | Alashan | Inner Mongolia | 10 | 3 | 0.5110 ± 0.1640 | 0.0012 |

| Gobi Red camel | Inner Mongolia | 10 | 4 | 0.7780 ± 0.0910 | 0.0021 | |

| Sunit | Inner Mongolia | 10 | 3 | 0.6890 ± 0.1040 | 0.0022 | |

| QingHai | Qinghai | 10 | 5 | 0.6670 ± 0.1630 | 0.0012 | |

| Zhungeer | Xinjiang | 5 | 4 | 0.9000 ± 0.1610 | 0.0032 | |

| Tarim | Xinjiang | 5 | 2 | 0.6000 ± 0.1750 | 0.0015 | |

| MuLei | Xinjiang | 5 | 2 | 0.6000 ± 0.1750 | 0.0007 | |

| Mongolia | Galbiin Gobiin Ulaan | Hanbogd soum | 8 | 4 | 0.7500 ± 0.1390 | 0.0018 |

| Haniin Hetsiin Huren | Mandal‐Ovoo soum | 10 | 6 | 0.8890 ± 0.0750 | 0.0029 | |

| Hos Zogdort | Tugrug soum | 10 | 4 | 0.7110 ± 0.1170 | 0.0025 | |

| Russia | Kalmyk | Astrakhan | 9 | 5 | 0.7220 ± 0.1590 | 0.0017 |

| Mongolia | Wild | Gobi Altai | 19 | 2 | 0.4560 ± 0.0850 | 0.0011 |

| Hybrid | Gobi Altai | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Sequences of the partial mtDNA were aligned using mega (version 6.0.6) (Kumar et al. 2001). To investigate the comparison research, 23 sequences of mtDNA fragment—six sequences from wild Bactrian camels (EF507800, EF507801, FJ792684, FJ792685, NC_009629 and EF212038) and 17 sequences from domestic Bactrian camels (EF507798, EF507799, EF212037, FJ792680–FJ792683, KF640722–KF640727, KF640729–KF640731 and NC_009628)—were also aligned using the mega program.

The parameters of the mitochondrial polymorphisms were computed using dnasp (version 5.1.0) (Librado & Rozas 2009), including nucleotide diversity (π), the number of haplotypes, haplotype diversity (Hd) and its standard error (SE). A median‐joining network (Bandelt et al. 1999) was drawn using the program network (version 4.6.1) to investigate possible relationships among the haplotypes. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbour‐joining method (Saitou & Nei 1987). The analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) (ExcoYer et al. 1992) was computed using integrated software for population genetics data analysis (arlequin, version 3.5.2) (Excoffier et al. 2007).

The analysis of 809‐bp mtDNA sequences in 113 Bactrian camels yielded 25 variable positions defining 15 different haplotypes (Table S2). These haplotypes included six previously described haplotypes (H1–H3, H6, H14 and H15; Silbermayr et al. 2010) and nine new ones (H4, H5, H7–H13; sequences deposited under accession nos. KX377598–KX377606). The largest haplotype group (H1) consisted of 41 individuals, and four haplotype groups (H1, H2, H3 and H14) included more than 10 individuals.

In the domestic Bactrian camel populations, the number of haplotypes detected in each domestic breed varied from two to six, and the haplotype diversity values ranged from 0.9000 ± 0.1610 in the Zhungeer to 0.5110 ± 0.1640 in the Alashan (Table 1). The level of nucleotide diversity (π = 0.00106) and haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.429± 0.089) of all the wild Bactrian camels were both lower than that of domestic Bactrian camels (π = 0.00207, Hd = 0.739 ± 0.035; Table S2). The nucleotide diversity (π = 0.0072) and haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.808 ± 0.025) of all the Bactrian camels in this study were calculated.

A variation was found in mtDNA among camels from China, Russia and Mongolia. The level of nucleotide diversity and haplotype diversity within Mongolia (π = 0.0026, Hd = 0.796 ± 0.048) were slightly higher than that of camels from China (π = 0.0019, Hd = 0.719 ±0.048) and Russia (π = 0.0017, Hd = 0.722 ± 0.159). Furthermore, we combined previously published sequences of Bactrian camel mtDNA fragment with 23 sequences in our data. The analysis showed 25 haplotypes in all 136 sequences, and the levels of nucleotide and haplotype diversity were 0.00897 and 0.972 ± 0.013, respectively.

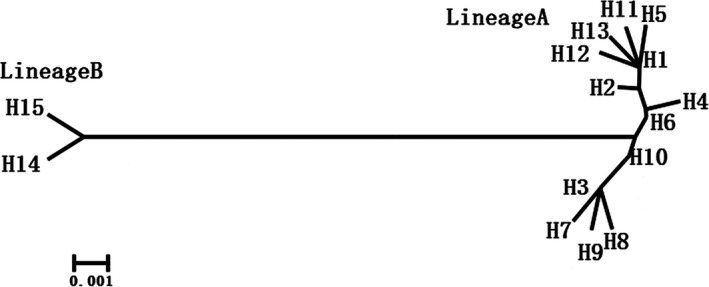

A neighbour‐joining phylogenetic tree was constructed to investigate the relationship between the 15 Bactrian camel mtDNA haplotypes (Fig. 2). The result clearly showed that all Bactrian camels were divided into two distinct lineages: A and B. Lineage A included 13 haplotypes from all domestic individuals, and Lineage B included two haplotypes from all wild and hybrid individuals. Furthermore, we combined previously published sequences from six wild Bactrian camels and 17 domestic Bactrian camels with our data to construct a phylogenetic tree using the dromedary camel (Dromedary camelus) as the outgroup (accession no. NC_009849.1) (Fig. S1). The result also supported the above statement and indicated that the wild and domestic Bactrian camel did not share a recent common ancestor and may have a long‐term divergence in their maternal origins. This is in agreement with a previous study that showed that the extant wild and domestic Bactrian camel had different maternal origins (Ji et al. 2009).

Figure 2.

Neighbour‐joining phylogeny with relationships among 15 Bactrian camel mtDNA haplotypes. Haplotypes are grouped in two main lineages (A and B).

The two distinct lineages were also identified using a median‐joining network method with 25 haplotypes from 136 sequences (Fig. S2). The 23 haplotypes of domestic Bactrian camels showed that breeds from different geographic regions intermingled. Some haplotypes were shared by individuals of different breeds from different geographical regions. In domestic Bactrian camels, all of the three main haplotypes—H1, H2 and H3—were found to comprise Chinese, Russian and Mongolian Bactrian camels. Haplotypes specific to a geographic region were also found. However, these region‐specific haplotypes accounted for only a small proportion of our samples (6.2%).

We performed several AMOVA to investigate geographical structuring. AMOVA analysis placed most of the genetic variance (90.14%, P < 0.01) between the wild and domestic camel clusters and little variance within the clusters (9.86%, P < 0.01). This result is similar to that from a previous study (95.64% and 4.36% respectively; Silbermayr et al. 2010).

In conclusion, the domestic Bactrian camel and wild Bactrian camel evolved as two distinct lineages, and it is suggested that they do not have the same maternal origins. The wild Bactrian camels displayed lower levels of nucleotide diversity and haplotype diversity, which may be due to the extremely small effective population size of the wild Bactrian camel. In addition, there was no significant geographical structuring among domestic Bactrian camels, and these results imply that gene flow and genetic admixture may exist between these domesticated Bactrian camels from different geographic regions.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Neighbor‐joining tree of wild and domestic Bactrian camel haplotypes based on 809 bp of the mtDNA. Haplotypes are grouped in two main lineages (lineage A and lineage B), each showing subgrouping.

Figure S2 Median‐joining network of 25 mtDNA haplotypes of domestic and wild Bactrian camels. The area of each circle is proportional to haplotype frequency.

Table S1 Details of the Bactrian camels used for mitochondrial (mtDNA) haplotypes.

Table S2 Variable nucleotides from 809‐bp mitochondrial DNA camel fragments of Bactrian haplotypes compared with reference sequences from GenBank accession no. NC_009628.2.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the International S & T Cooperation Program of China (2015DFR30680, ky201401002) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31360397). We would like to thank the native English speaking scientists of Elixigen Company (Huntington Beach, CA, USA) for editing our manuscript.

Contributor Information

Z. Wang, Email: zwang01@sibs.ac.cn

R. Ji, Email: yeluotuo1999@vip.163.com

References

- Bandelt H., Forster P. & Rohl A. (1999) Median joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 16, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.‐Y., Su Y.H., Wu S.‐F. & Zhang Y.P. (2005) Mitochondrial diversity and phylogeographic structure of Chinese domestic goats. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37, 804–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuluunbat B., Charruau P., Silbermayr K., Khorloojav T. & Burger P. (2014) Genetic diversity and population structure of Mongolian domestic Bactrian camels (Camelus Bactrianus). Animal Genetics 45, 550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovchindorj G., Mijiddorj B. & Adiya Y. (2006) Population ecology of the wild camel in Mongolia In: Proceedings of the International Workshop on Conservation and Management of the Wild Bactrian Camel (Ed. by Adiya Y., Lhagvasuren B. & Bayasgalan A.), pp. 24–8. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L., Laval G. & Schneider S. (2007) arlequin (version 3.0): An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online 23, 47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ExcoYer L., Smouse P.E. & Quattiro J.M. (1992) Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics 131, 479–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare J. (1997) The wild Bactrian camel (Camelus Bactrianus ferus) in China: the need for urgent action. Oryx 31, 45–8. [Google Scholar]

- Isani G.B. & Baloch M.N., Arab Centre for the Studies of Arid Zones and Dry Lands, Pakistan Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Livestock & and Camel Applied Research and Development Network . (2000) Camel Breeds of Pakistan (CARDN‐Pakistan/ACSAD/P 94/2000). Arab Centre for the Studies of Arid Zones and Dry Lands, Damascus, Syria. [Google Scholar]

- Ji R., Cui P., Ding F., Geng J., Gao H., Zhang H., Yu J., Hu S. & Meng H. (2009) Monophyletic origin of domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus Bactrianus) and its evolutionary relationship with the extant wild camel (Camelus Bactrianus ferus). Animal Genetics 40, 377–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji R., GangLiang C. & Zhenyu Y. (2009) The Bactrian camel and Bactrian camel milk. Chinese Light Industry Press, China, 9–12 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Tamura K., Jakobsen I.B. & Nei M. (2001) mega2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17, 1244–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S.J., Liu Y.P., Liu Y.X., Li X.W. & Yao Y.G. (2006) Genetic diversity and origin of Chinese cattle revealed by mtDNA D‐loop sequence variation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 38, 146–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P. & Rozas J. (2009) dnasp v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei F. (2012) Production and trade of camel products in some Middle East countries. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development 1, 153–60. [Google Scholar]

- Moqaddam E. & Namaz‐Zadeh K.P. (1998) An introduction to various breeds of camel in Iran. Mazraeh (Farm): Analytical and Educational Magazine 11, 73–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reading R.P., Blumer E.S., Mix H. & Adiya Y. (2005) Wild Bactrian camel conservation. Erforschung Biologischer Resourcen der Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 9, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Saipolda T. (2004) Mongolian camels In: Current Status of Genetic Resources, Recording and Production Systems in African, Asian and American Camelids, Proceedings of the ICAR/FAO Seminar Held in Sousse, Tunisia, 30 May 2004 (ICAR Technical series No. 11) (Ed. by Cardellino R., Rosati A. & Mosconi C.), pp. 73–9. ICAR, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N. & Nei M. (1987) The neighbor‐joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4, 406–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbermayr K., Orozco‐terWengel P., Charruau P., Enkhbileg D., Walzer C., Vogl C., Schwarzenberger F., Kaczensky P. & Burger P.A. (2010) High mitochondrial differentiation levels between wild and domestic Bactrian camels: a basis for rapid detection of maternal hybridization. Animal Genetics 41, 315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te M., San G., San C. & Ji R. (2013) Investigation report on the current situation of Mongolia Bactrian Camel. The Progress of Chinese Camel Industry 3, 11–5. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S., Sharma N., Sheikh F.D, Singh S., Sena D.S. & Bissa U.K. (2015) Reproductive status of Camelus Bactrianus during early breeding season in India. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction 4, 61–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Wang J., Kijas B., Liu B., Han H., Yu M., Yang H., Zhao S. & Li K. (2003) Genetic diversity present within the near‐complete mtDNA genome of 17 breeds of indigenous Chinese pigs. Journal of Heredity 94, 381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Neighbor‐joining tree of wild and domestic Bactrian camel haplotypes based on 809 bp of the mtDNA. Haplotypes are grouped in two main lineages (lineage A and lineage B), each showing subgrouping.

Figure S2 Median‐joining network of 25 mtDNA haplotypes of domestic and wild Bactrian camels. The area of each circle is proportional to haplotype frequency.

Table S1 Details of the Bactrian camels used for mitochondrial (mtDNA) haplotypes.

Table S2 Variable nucleotides from 809‐bp mitochondrial DNA camel fragments of Bactrian haplotypes compared with reference sequences from GenBank accession no. NC_009628.2.