Abstract

Although age-associated changes in kidney glomerular architecture have been described in mice and man, the mechanisms are unknown. It is unclear if these changes can be prevented or even reversed by systemic therapies administered at advanced age. Using light microscopy and transmission electron microscopy, our results showed glomerulosclerosis with injury to mitochondria in glomerular epithelial cells in mice aged 26 month (equivalent to a 79 year old human). To test the hypothesis that reducing mitochondrial damage in late age would result in lowered glomerulosclerosis, we administered the mitochondrial targeted peptide, SS-31 to aged mice. Baseline (24 month-old) mice were randomized to receive 8 weeks of SS-31, or saline, and sacrificed at 26 months of age. SS-31 treatment improved age-related mitochondrial morphology and glomerulosclerosis. Assessment of glomeruli revealed that SS-31 reduced senescence (p16, senescence-associated-β-Gal) and increased the density of parietal epithelial cells. However, SS-31 treatment reduced markers of parietal epithelial cell activation (Collagen IV, pERK1/2 and α-smooth muscle actin). SS-31 did not impact podocyte density, but reduced markers of podocyte injury (desmin), and improved cytoskeletal integrity (synaptopodin). This was accompanied by higher glomerular endothelial cell density (CD31). Thus, despite initiating therapy in late-age mice, a short course of SS-31 has protective benefits on glomerular mitochondria, accompanied by temporal changes to the glomerular architecture. This systemic pharmacological intervention in old-aged animals limits glomerulosclerosis and senescence, reduces parietal epithelial cell activation, and improves podocyte and endothelial cell integrity.

Keywords: podocyte, glomerulosclerosis, glomerulus, parietal epithelial cell

INTRODUCTION

With a diagnosis rate that has more than doubled in the last 20 years, it is estimated that greater than 25% of Americans over 65 years of age have significant chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1, 2). Even in individuals lacking CKD, advanced age increases sensitivity to acute kidney injury while decreasing the ability to repair damaged renal tissue (3–6). These statistics underscore the urgent need for a better understanding of the impact of aging on kidney structure and function. Age-related kidney changes are typically progressive and even predictable, with significant reduction of kidney mass occurring between ages 50–80 (7). These changes are most marked in the renal cortex, where by age 75, 30% of renal filtration units, nephrons, are lost or severely damaged (8). Histological changes to the aged nephron include damage to glomeruli, proximal tubules and vasculature (7, 9, 10). The hallmark changes in the aged glomerulus include reduced density of podocytes (11) and parietal epithelial cells (PECs) (12), loss of capillaries and glomerulosclerosis (13). These changes are significant in that they underlie the susceptibility to and magnitude of glomerular and tubulo-interstitial diseases in the aged population. However, it remains unclear whether these age-related histological changes can be prevented, and once established, whether they are partially or fully reversible.

Mitochondrial-derived reactive oxygen species (mtROS) have been proposed to underlie age-related kidney pathology. An important role for mitochondria is supported by the causal link between mitochondrial dysfunction and age-related senescence (14, 15). Intentional mitochondrial damage to human cells induces senescence, and mice with accelerated rates of mitochondrial DNA damage also exhibit senescent cell accumulation and increased rates of aging (14).

With age there is a loss of mitochondrial quality associated with disruption of the stoichiometry of the electron transport chain and elevated mitochondrial oxidative stress which leads to loss of mitochondrial, and thus cellular, function (16, 17). Structurally, this is accompanied by increased lipid peroxidation (18), which manifests as a loss of mitochondrial membrane integrity, such that the folding of the inner membrane to form cristae is severely compromised (19). Nearly 20% of the lipid content of the inner mitochondrial membrane is composed of cardiolipin, a unique phospholipid that is required for cristae formation, and which is particularly vulnerable to peroxidation. Mitochondria in aged rat hearts have significantly lower cardiolipin content, increased peroxidized cardiolipin and increased ROS production (20). Thus, protection of cardiolipin may represent a therapeutic target for minimizing age-related mitochondrial dysfunction.

Elamipretide (SS-31) is a mitochondria-targeted tetrapeptide that selectively interacts with cardiolipin on the inner mitochondrial membrane. SS-31 enhances electron transfer through cytochrome c to improve oxidative phosphorylation coupling, increases ATP synthesis and reduces ROS production (21, 22). SS-31 inhibits cytochrome c peroxidase activity and prevents cardiolipin peroxidation(22–24). In young animals with acute renal ischemic injury (25) or renal damage induced by high fat diet (26), SS-31 intervention protects mitochondria structure and reduces the extent of tubular and glomerular injury. In the current studies we set out to determine if we could preserve or restore mitochondrial structure in the kidneys of mice with advanced age by administering a short course of SS-31, and if SS-31 could prevent and/or partially reverse changes in glomerular architecture of aged mice. Accordingly, baseline aged 24m-old mice were given SS-31 or vehicle (saline) for 8 weeks, and progression of glomerular changes was examined by histological analysis.

RESULTS

SS-31 protects aging mitochondria in podocytes and parietal epithelial cells from structural degradation

Age-induced glomerulosclerotic lesions are focal throughout the affected kidney. Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) of glomeruli from 24m old mice (used as the aged baseline in these studies) showed that mitochondrial damage was evident in cells of the glomerulus by disruption of inner mitochondrial membranes, loss of cristae, changes in mitochondrial matrix density, and outer membrane rupture (Figure 1A). To assess the extent of mitochondrial damage, we used a semi-quantitative method to score both podocytes and parietal epithelial cells (PECs). The schematic of the semi-quantitative scoring criteria is shown in Supplemental Figure 1. Both podocytes and parietal epithelial cells (PECs) had measurable evidence of mitochondrial damage (Figure 1D and E)

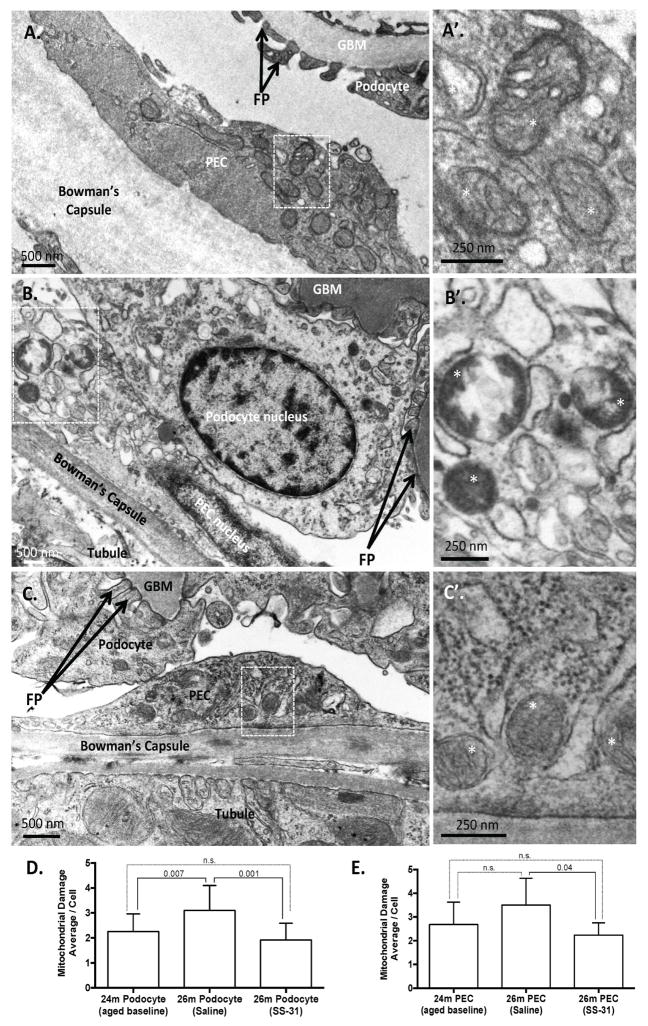

Figure 1. SS-31 protects mitochondria in aged glomerular epithelial cells.

(A)Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in 24m-old aged baseline mice. 24m-old mouse used as aged baseline before SS-31 administration. Image of glomerulus showing podocyte and parietal epithelial cell (PEC) with mitochondrial damage. The Bowman’s capsule is thickened. Here the capillary glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is normal and podocyte foot processes (FP) are evenly spaced along the GBM to form the filtration slits. (A’) An inset from the PEC in (A) viewed at higher power shows loss of cristae and mitochondrial vacuoles, features of mitochondrial damage.

(B) Saline vehicle treated 26m-old mice. TEM from glomerulus of 26m-old mouse treated with saline vehicle for 8w. A podocyte and PEC exhibit considerable accumulation of cellular damage when compared to the 24m-old baseline animal. Podocyte foot processes (FP, black arrows) are effaced and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) is thickened and irregular. (B’) An inset from the PEC in (B) viewed at higher power shows mitochondrial damage characterized by extensive loss of cristae and compromised outer mitochondrial membranes.

(C) SS-31 treated 26m-old mice. TEM from the glomerulus of a mouse treated for 8w with SS-31 shows protection of mitochondria in the podocytes and PECs as compared to saline vehicle treated animals. (C’) Inset in (C) shows intact outer membrane and inner membrane cristae of PEC (asterisk show examples).

(D) Average semi-quantitative mitochondrial damage score from multiple podocytes (24m = 20; 26m Saline = 12; 26m SS-31 = 14) showing that mitochondrial damage increases significantly from 24-26m of age, which is prevented by treatment with SS-31.

(E) Average semi-quantitative mitochondrial damage score from multiple PECs (24m = 16; 26m Saline = 3; 26m SS-31 = 6) shows that treatment with SS-31 significantly reduces mitochondrial damage score relative to age-matched saline treated group. Graphs show mean per cell, from 3–4 animals per group, with error bars as SD.

To determine if aging-associated damage was reversible or preventable, we administered SS-31 or saline to the aged baseline mice, starting at 24m of age (~70 y.o. human). Mice treated with 8w of the vehicle control, saline, had damage to the mitochondria of podocytes that significantly increased from 24m to 26m of age (~79 y.o. human), whereas PEC damage remained the same. (Figure 1B, D and E). In contrast, the mitochondria in podocytes and PECs in aged mice treated with SS-31 had more visibly regular structures of cristae and intact double outer mitochondrial membranes. (Figure 1C, D and E). Semi-quantitative measurement of mitochondrial damage in SS-31 treated mice demonstrated that mitochondria in both podocytes and PECs were improved relative to saline treated animals, with reduced levels of damage similar to those seen in the younger 24m-old animals.

To determine if these structural measures were indeed preceded by changes to enzymes of the mitochondria electron transport chain, a subgroup of 24m aged baseline mice were given SS-31 or saline for 2w. Quantitative real-time PCR showed that gene expression of Ndufa9 and Cox IV, both encoding enzymes required in the mitochondria electron transport chain, were increased significantly in the renal cortex of 24m-old mice treated with SS-31 for 2w as compared to saline treated animals (Supplemental Figure 5). Collectively these results demonstrated that late-age treatment with SS-31 improves mitochondrial health in the glomeruli of aged mice.

SS-31 reduced the expression of the oxidation species-generating enzyme, Nox4, in aged mouse kidneys

Both aging and mitochondrial damage increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation (18, 28). NADPH Oxidase 4 (Nox4) is upregulated by ROS generated from mitochondrial dysfunction, and in turn increased Nox4 also generates ROS, thereby creating a redox signaling loop (29–31). Nox4 increases with age and its expression correlates with ROS accumulation in the kidney (32, 33). For these reasons, we used Nox4 expression as a potential metric for signaling changes in response to SS-31 mitochondrial treatment.

In 24m-old aged baseline mice, Nox4 staining was readily detected in both glomeruli and tubules of the cortex (Figure 2). Within glomeruli, Nox4 staining localized to PECs, podocytes and mesangial cells. Two different antibodies were used to confirm Nox4 staining (Figure 2I & J); immunostaining was not detected upon removing the primary Nox4 antibody, used as a negative control (Figure 2H).

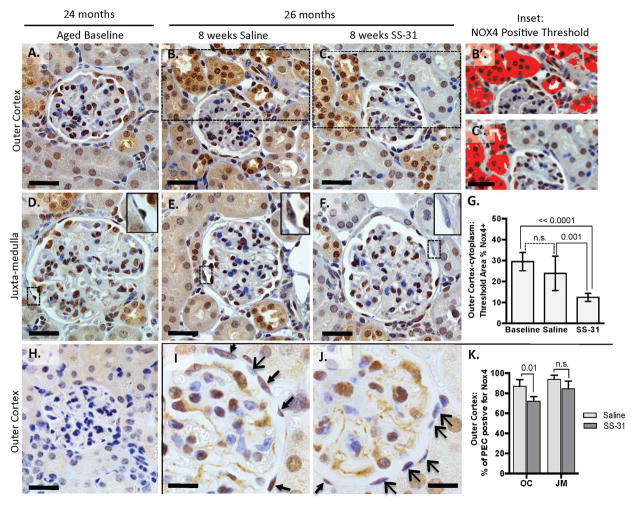

Figure 2. Expression of the reactive oxygen species-generating enzyme, Nox4, is reduced in kidneys of mice with advanced age treated with SS-31.

(A–G) The increase in Nox4 expression in aged kidneys is reduced by SS-31. Nox4 staining is detected in the nucleus and cytoplasm of glomeruli and tubules throughout the kidney but is most readily detectable in the outer cortex. (A–F) Representative immunohistochemistry images of Nox4 staining with a primary antibody (from Abcam, brown) counterstained with hematoxylin (blue, nuclear) in the outer cortex and juxta-medulla in 24m-old aged baseline mice (A, D), 26m-old mice given 8 weeks of saline (B, E), and SS-31-treated 26m-old mouse, which shows reduced cytoplasmic stain relative to other groups. (C, F). Scale bar = 25 μm. (B’, C’) Insets from B and C. Examples of images used to quantify relative levels of cytoplasmic Nox4 expression in the outer cortex by measuring areas of dark brown staining containing color threshold (solid dark red) selection using imageJ software. (G) Quantification of Nox4 staining in the outer cortex shows a significant decrease with SS-31 treatment. 26m-old mice given 8w of SS-31 had less cortical Nox4 staining when compared to aged-matched saline treated mice and baseline 24m-old mice. Error bars show the mean ± standard deviation. (H) Negative control: Omitting the primary Nox4 antibody in 26m-old Saline treated animals showed no dark brown staining.

(I–K) Nox4 expression is reduced in parietal epithelial cells of aged mice treated with SS-31. A second primary antibody (Novus) to Nox4 confirmed the staining pattern in D-I in that Nox4 positive cells (brown) are seen in all treatment groups, including parietal epithelial cells (PECs), podocytes and mesangial cells, based on location within the tuft. (I, J) PECs positive for Nox4 are seen in all mice (brown stain, thin arrows) but this expression is reduced in SS-31 treated animals (blue stain, wide arrow heads). Scale bar = 10μm.

(K) Quantification of Nox4 positive cells shows that SS-31 significantly reduces Nox4 staining of PECs in 26m-old mice in the outer cortex. These results show that Nox4 expression is reduced both in the cytoplasm and nucleus by SS-31 treatment.

Computerized quantitation of total Nox4 positive area by color threshold (Figure 2B’, C’& G) showed that Nox4 staining was significantly lower in the outer cortex of mice given 8w of SS-31 from aged baseline of 24m to 26m (positive Nox4 threshold = 23.8 ± 8% of cortex area in saline treated vs. 12.4 ± 1.9% for SS-31 treated mice). This reduction was most remarkable in the tubules of the outer cortex. SS-31 treatment also significantly reduced Nox4 expression in PECs in outer cortical glomeruli (Figure 2I–K) but podocyte staining appeared unchanged.

Nox4 is a transmembrane spanning protein localizing to membranes of nuclei (34, 35), mitochondria (36), and endoplasmic reticulum (37). In the aged 24m-old mice, co-localization of Nox4 with the mitochondrial protein, NDUFA9 and the nuclear stain, DAPI, confirmed Nox4 expression in both cellular compartments in the tubules and PECs of aged mice (Supplemental Figure 4). Although these results confirm Nox4 staining is increased in the kidneys of C57bl/6J mice with advanced age, (38, 39) they are the first showing that Nox4 is expressed in aged PECs, and the first to establish that pro-oxidant enzyme levels in aged mouse kidneys can be partially lowered by 8w of systemic SS-31 treatment.

Glomerulosclerosis is lower in aged mouse kidneys following SS-31 treatment

To determine whether reduction of mitochondrial damage by SS-31 altered renal aging, we began by quantifying glomerulosclerosis (28). In 24m-old mice, mild glomerulosclerosis was detected (Figure 3). As expected, when 24m-old mice were given saline for 8w and sacrificed at 26m of age, the extent of glomerulosclerosis was progressively higher (mean score 24m = 0.73±0.19 vs. 26m = 0.86±0.11)(Figure 3B). In contrast, an 8w course of SS-31 treatment was accompanied by significantly lower glomerulosclerosis compared to age-matched mice given saline (0.66±0.09 vs. 0.86±0.11 p-value = 0.004 vs. saline at age 26m)(Figure 3B). Because we recently reported that the extent of glomerular scarring in aged kidneys differs between the outer cortex (OC) and juxta-medulla (JM) regions of the kidney (12), we next quantitated glomerulosclerosis in both kidney compartments independently. Consistent with our prior observations, glomerulosclerosis scores were significantly higher in JM than OC glomeruli in all groups (Figure 3C&D).

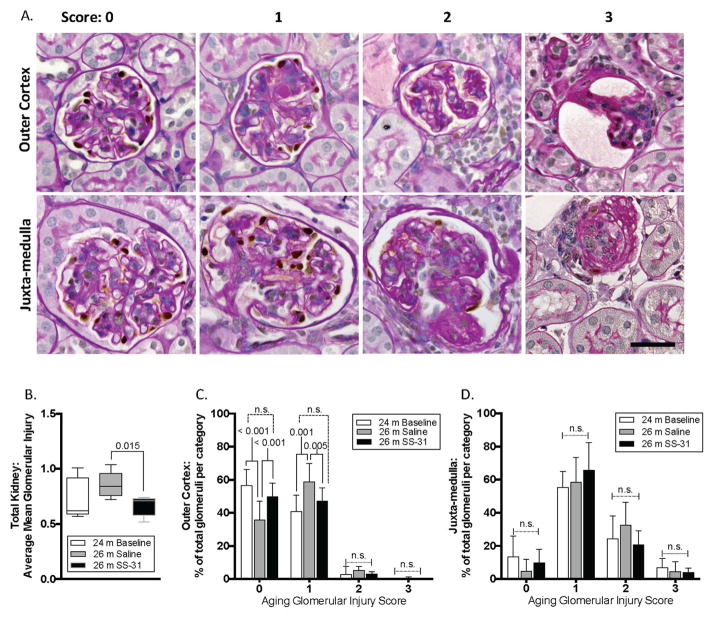

Figure 3. Glomerulosclerosis in aged kidneys is attenuated with SS-31 treatment.

(A) Representative images of periodic acid–Schiff stained (PAS) kidney sections, counter stained with hematoxylin to identify nuclei (blue) used for quantitation shown in graphs in B–D. p57 co-staining (brown, nuclear) was used to identify podocytes. Examples of glomeruli are shown for each scoring category to demonstrate the criteria used to quantitate glomerular injury, ranging from 0 (no injury) to 3 (globally sclerotic glomeruli). Glomeruli were further segregated based on location in either the outer cortex or the juxta-medullary cortex.

(B) Graph showing mean glomerular injury score, determined by individual scoring of every glomerulus within one longitudinal mid-kidney section. 26m-old saline treated mice have a higher injury score than 24m-old mice (aged baseline), but the difference did not reach statistical significance. 26m-old mice treated with SS-31 had an injury score similar to 24m old aged baseline mice, which was also significantly lower than age-matched saline treated mice

(C) In outer cortex, the percentage of glomeruli that were uninjured (score 0) was lowest in 26m-old saline treated mice, indicating more injured glomeruli than in either age matched SS-31 treated animals or baseline 24m-old animals. SS-31 treatment increased the number of uninjured outer cortical glomeruli compared to saline treatment. The percentage of glomeruli with stage 1 injury was higher in saline treated 26m-old mice than aged baseline 24m-old animals. SS-31 in age matched 26m-old mice again reduced the percentage of stage 1 injured glomeruli in the outer cortex. There were no differences in the groups for stage 2 and 3 injured glomeruli.

(D) In the juxta-medulla, there were no significant differences in glomerular injury scores between groups; the majority of glomeruli had an injury score of 1 in all groups of mice demonstrating that mild injury was more prevalent in all mice within the juxta-medullary cortex than in the outer cortex.

These results show that using PAS scoring, SS-31 significantly reduced glomerular injury in aged mice in the outer cortex, but not in the juxta-medulla.

Analyzing the OC and JM regions separately further showed that the reduction in glomerulosclerosis in the OC glomeruli primarily accounted for the differences in the total mean injury score following SS-31 (Figure 3B–D). Assessing these differences by score category revealed that the differences in mean score of OC glomeruli were primarily driven by a shift towards category 0 (uninjured) with less category 1 and 2 (injured) glomeruli in the SS-31 treated animals (Figure 3C). The OC glomeruli in saline treated animals were often collapsed, with fewer visible capillary loops and expanded PAS mesangial staining. In contrast, more of the OC glomeruli from SS-31 treated animals had preserved glomerular architecture by PAS. Although the SS-31 treated animals had healthier glomeruli overall in the JM as compared to the vehicle control, both 26m-old groups exhibited more damaged glomeruli in the JM region when compared to the younger 24m-old animals (Figure 3D), demonstrating that SS-31 was not able to completely prevent injury in this compartment.

Urine albumin to creatinine ratio was used to measure kidney function and ranged from 0.04–1.23. However, no significant differences were found between groups (Supplemental Figure 6). Nevertheless, glomerulosclerosis was clearly progressive in the saline treated group, but not in the SS-31 treated group, which indicates that SS-31 limited the progression of age-related glomerulosclerosis in mice with advanced age. These data provided a rationale to further examine which glomerular cell types were responding to SS-31 treatment.

PEC number is higher in aged mice following SS-31 treatment

PEC density is reduced in aged mouse kidneys (12). Therefore, we quantified PEC number to determine whether SS-31 inhibition of mitochondrial damage (Figure 2) and reduction of Nox4 expression (Figure 3) preserved PEC density. PAX8 staining was used to identify PECs (Figure 4). Compared to 24m-old baseline aged mice, 26m-old mice that received 8w of saline had no change in PEC number. However, after receiving 8w of SS-31, 26m old mice had significantly higher PEC number in JM glomeruli compared to 24m old mice (SS-31 = 6.54 vs. 24m baseline = 5.00, p-value = 0.02)(Figure 4B).

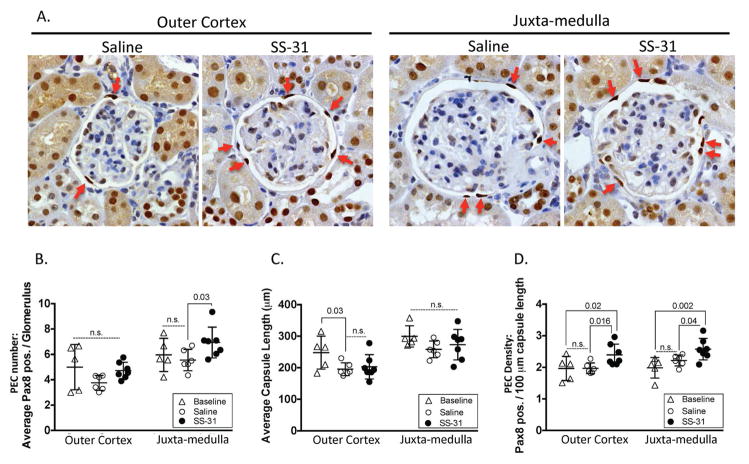

Figure 4. Parietal epithelial cell (PEC) density in aged kidneys is increased by SS-31.

(A) Pax8 and hematoxylin staining to identify PECs. Representative images for Pax8 immunohistochemistry used to identify PECs (darkest brown nuclear staining along Bowman’s capsule, red arrows show examples) in glomeruli from the outer cortex and juxta-medulla in 26m-old mice given either 8w of saline or SS-31. Hematoxylin identifies all nuclei.

(B) Average number of Pax8 stained cells along Bowman’s capsule per glomerulus. The average total number of PECs was not statistically different in outer cortical glomeruli between 24m-old baseline (triangles), 26m-old saline vehicle treated (open circles) and 26m-old SS-31 treated (closed circles) mice. PEC number in juxta-medullary glomeruli was higher in SS-31 treated animals compared to aged baseline mice, and to age matched saline treated mice.

(C) Average Bowman’s capsule length per glomerulus. In outer cortical glomeruli, the average capsule length was lower in 26m-old mice as compared to 24m-old aged baseline mice, regardless of treatment. Average capsule length did not differ in juxta-medullary glomeruli.

(D) PEC density. PEC density was measured as the average PEC number per 100μm of Bowman’s capsule length. PEC density in outer cortex and juxta-medulla glomeruli did not differ between 24m aged baseline and 26m saline treated mice. In contrast, in 26m-old mice given 8w of SS-31, PEC density was significantly higher compared to baseline and saline treated mice, in both glomerular compartments. These results show that when mice aged 24m are given 8w of SS-31, PEC density is increased.

Because of age-related changes in glomerular size, Bowman’s capsule length was used to normalize PEC density, defined as the number of PECs per length of Bowman’s capsule (Figure 4D). PEC density did not change from 24m to 26m with 8w of saline treatment (OC Saline = 1.97 vs. OC 24m baseline = 1.97; JM saline = 2.19 vs. JM 24m baseline = 1.98). However, PEC density was significantly higher in SS-31 treated mice in glomeruli of both OC (OC SS-31 = 2.44 ±0.34, p-value = 0.02 vs. baseline and saline) and JM (JM SS-31 = 2.57 ±0.37, p-value = 0.002 vs. baseline and 0.04 vs. saline)(Figure 4D). These results show that 8w of SS-31 treatment given to 24m-old mice leads to a higher PEC density at 26m of age in glomeruli in both OC and JM compartments.

Senescence is reduced in PECs and glomerular tuft cells in aged mice given SS-31

p16 Staining

Cellular senescence increases with mitochondrial damage (14, 40). Thus, we asked if senescence was increased in this cohort of aged mice, and if so, whether senescence was partially/fully reduced in aged SS-31 treated animals. Young animals were included in these analyses as a negative control for age-related senescent markers. Staining for p16 revealed glomerular expression in both PECs and cells within the tuft (Figure 5A–H). In aged baseline 24m-old animals, the percentage of p16 positive PECs on Bowman’s capsule was increased in both outer cortex and juxta-medulla glomeruli relative to young control animals (24m = 22.7%, 3m average = 5.3%; p-value < 0.05, Figure 5I and J). The percentage of PECs staining for p16 further increased in 26m-old saline treated animals. In contrast, in 26m-old SS-31 treated animals, p16 staining did not significantly differ from 24m-old aged baseline mice (26m SS-31 average = 29.6%, vs, 26m saline = 55%; p-value < 0.003 Figure 5I and J).

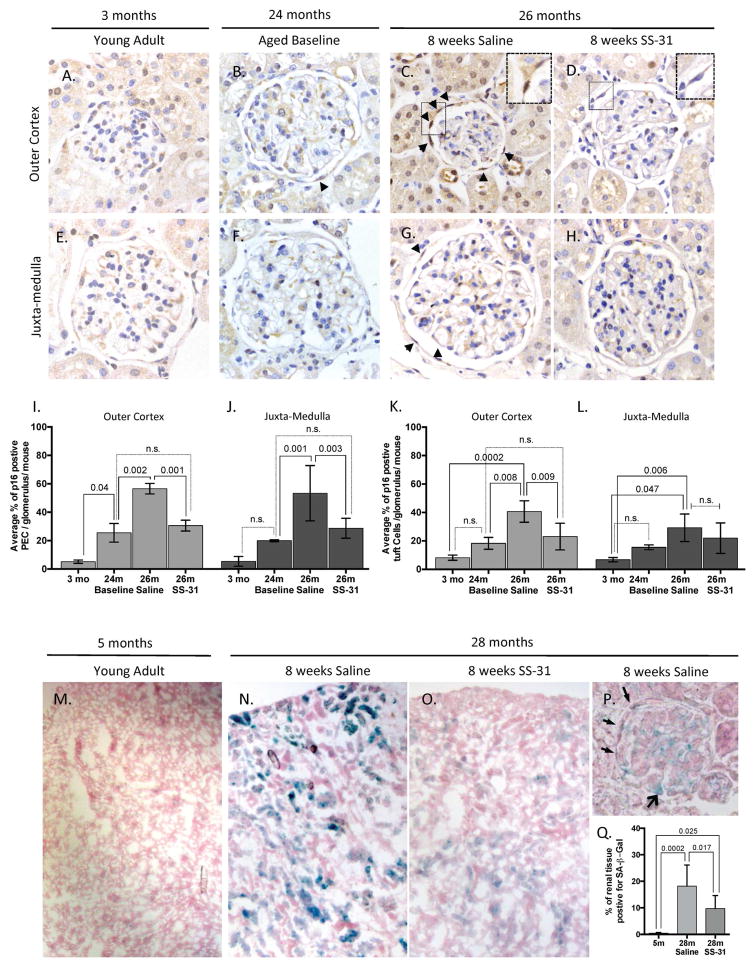

Figure 5. Senescent cells are reduced in the kidney with late-age SS-31 treatment.

(A–H) Representative images of p16 immunohistochemistry used to identify and quantify senescent cells as detected by p16 staining (darkest brown nuclear stain) are shown in glomeruli from the outer cortex (A–D) and juxta-medulla (E–H). (A, E) In 3m-old young control mice, p16 staining was rarely detected in either compartment. (B, F) In 24m-old baseline mice, p16 staining is detected in parietal epithelial cells (PEC, examples represented by arrowheads) on the Bowman’s capsule and in cells of the glomerular tuft. (C, G) In 26m-old mice given 8w of saline, p16 stained PECs are readily detected along Bowman’s capsule (arrow heads show examples). Inset in C shows p16 staining in adjacent PECs. (D, H) SS-31 reduced p16 staining in PECs and in cells of the glomerular tuft in 26m-old mice. Inset in D shows PECs staining for nuclear hematoxylin, but not for p16.

(I, J) Quantification of p16 expression in PECs. The percentage of PECs staining positive for p16 per glomerulus was measured by quantitating the total number of PECs based on size and location along the Bowman’s capsule that were colored either blue hematoxylin (negative p16) or brown (p16 positive). (I) In the outer cortex, the percentage of PECs staining positive for p16 per glomerulus increased by 24m of age compared to 3m-old young mice. The percentage of positive cells was higher in 26m-old saline treated animals. In contrast, the percentage of PECs staining for p16 was significantly lower in SS-31 treated animals, which was also comparable to the aged baseline of 24m.

(J) In juxta-medullary glomeruli, the percentage of PECs staining positive for p16 was significantly increased at 26m in the saline group compared to 24m aged baseline. SS-31 significantly reduced the percentage of PECs staining for p16 at 26m, similar to the level seen in 24m-old animals. These results show that PECs undergo increased senescence with advancing age in both outer cortical and juxta-medullary glomeruli, which is reduced by SS-31. (J, K) Quantification of p16 expression in cells of the glomerular tuft. All nuclei within the glomerular tuft were scored as either staining p16 positive (brown) or negative (blue, hematoxylin). (J) 26m-old saline treated animals had the highest percentage of p16 positive tuft cells in the outer cortex; SS-31 significantly lowered p16 staining in outer cortical glomerular tuft cells. (K) The percentage of juxta-medullary glomerular tuft cells staining for p16 increased in 26m old saline treated mice. Although there was a trend to a decrease by SS-31, this did not reach statistical significance. Taken together, these results show that p16 staining increased in glomerular tuft cells in aged mice, but staining was only reduced in outer cortical glomeruli.

(K–M) Senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining on kidneys of 28m-old mice with and without SS-31 treatment. Representative low power images of fresh-frozen renal sections stained for SA-β-Gal (blue) and counterstained with nuclear fast red (pink) at (M) 5m of age and at 28m of age with either, (N) 8w of saline or, (O) 8w of SS-31 treatment starting at 26m of age (aged baseline for this group). (P) Representative high power image of a glomerulus from a saline treated mouse demonstrates that both PECs (narrow arrow heads) and podocytes (open arrow) exhibit SA-β-Gal senescent staining in 28m-old animals.

(Q) Quantification of SA-β-Gal senescent staining by tissue area. Irrespective of SA-β-Gal staining intensity, blue areas of staining were measured in 5x images and represented as a percentage of total tissue (sum of pink - nuclear fast red, and blue staining areas). Error bars show standard deviation. These results show that senescence based on SA-β-Gal staining was significantly increased from young adult to 28m-old aged animals given saline, which was significantly reduced by treatment with SS-31.

In the glomerular tufts of both the outer cortex and juxta-medulla, the percentage of p16 positive cells increased from young to old, but was not significantly different at 24m-old aged baseline (3m average = 7.46% vs. 24m = 16.9%, Figure 5K and L). However, by 26m of age, this difference reached significance in the saline treated animals. Staining for p16 in the glomerular tuft was significantly reduced by SS-31 treatment only in the outer cortex (26m saline = 34.97% vs. 26m SS-31 = 22.48%, p-value = 0.009, Figure 5K).

SA-β-gal Staining

To validate senescence with a second method, we examined the senescent cell marker known as senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) in a second group of older female mice. These animals were treated from an aged baseline of 26m-old for 8w of either saline or SS-31 treatment and sacrificed at 28m. As a young negative control, sex-matched 5m-old mice were included in these analyses (Figure 5M–Q). At 5m of age, SA-β-gal was nearly undetectable, whereas at 28m all sections had visible staining (Figure 5N–P). In animals treated with SS-31 the reduction of SA-β-gal staining was significant (28m saline = 18.15% vs. 28m SS-31 = 9.67%, p = 0.017) (Figure 5Q). Quantitative real-time PCR of renal cortex demonstrated that p16 mRNA was also increased in this older group of mice from 5m to 28m of age, and although not significant, there was a downward trend in p16 mRNA expression with 8w of SS-31 (Supplemental Figure 5).

Thus, two methods in two different cohorts showed that SS-31 treatment reduces the aging accumulation of senescent renal cells and that PECs are particularly susceptible to senescence, a phenomenon that was previously unconfirmed.

PEC activation and transformation markers, a-SMA, Collagen IV and pERK are reduced by SS-31 treatment

a-SMA

We next assessed the impact of SS-31 on age-related PEC phenotypic changes. Alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression was used as marker of epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Similar to our recent report (12), α-SMA staining of PECs from saline treated 26m-old mice was increased relative to 24m aged baseline (Figure 6). In 26m aged mice given SS-31, despite having a higher PEC density, α-SMA staining was reduced in PECs in both the outer cortex (OC) and juxta-medullary (JM) glomeruli (Figure 6A–D).

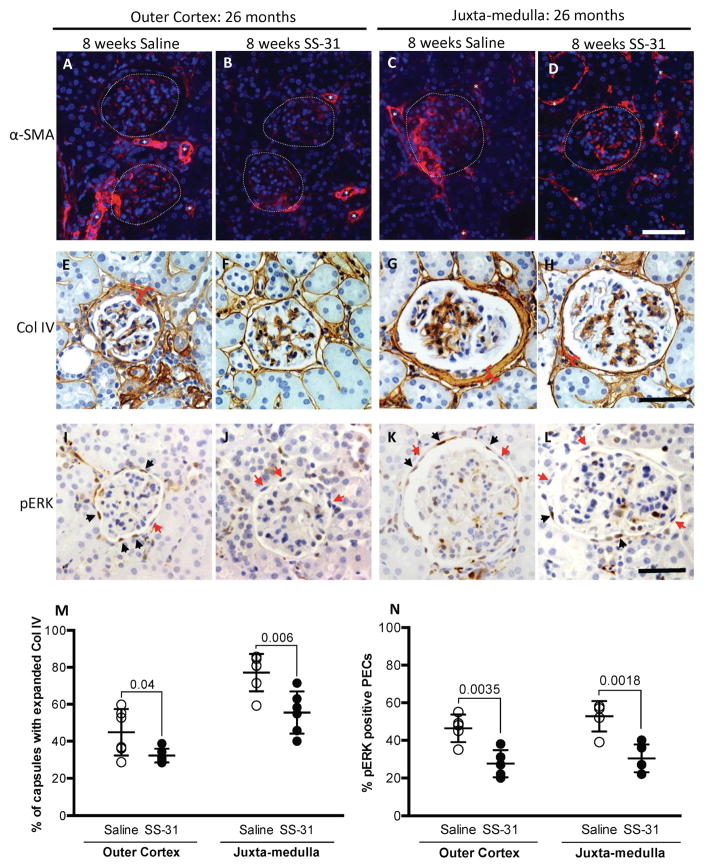

Figure 6. SS-31 lowers expression of α-SMA, collagen IV and pERK in glomerular parietal epithelial cells in aged mice.

(A–D) Alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)(red) and DAPI (blue) staining. (A) α-SMA staining is detected in outer cortical glomeruli in the tuft and along Bowman’s capsule in saline treated mice. Glomeruli are outlined by dotted lines, white asterisks represent staining in vessels. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) SS-31 treatment lowers α-SMA staining in outer cortical glomeruli. (C) α-SMA staining is detected in the tuft and Bowman’s capsule in juxa-medulla glomeruli in aged mice given saline. (D) α-SMA staining is lower in juxta-medullary glomeruli in SS-31 treated mice.

(E–H) Collagen IV (brown, cytoplasmic) and hematoxylin (blue, nuclear) staining. (E) Collagen IV (Col IV) staining is abundant along Bowman’s capsule in outer cortical glomeruli in saline-treated aged mice. Bracket with asterisk shows most expanded capsule region in each panel. (F) SS-31 treatment lowers collagen IV staining along Bowman’s capsule in outer cortical glomeruli. (G) In juxta-medullary glomeruli of saline treated mice, collagen IV staining is abundant along Bowman’s capsule, which is lower in mice given SS-31 (brackets with asterisks) (H). See M for Collagen quantitation.

(I-L) Phospho-ERK 1/2 protein (pERK)(brown nuclei) and hematoxylin (blue nuclei) staining. (I) pERK staining is detected in a PEC distribution (along Bowman’s capsule) in outer cortical glomeruli of saline treated aged mice. Black arrows show brown pERK positive nuclei, red arrows show blue nuclei and are pERK negative. (J) SS-31 lowers PEC pERK staining in outer cortical glomeruli. (K) pERK staining is detected in PECs in juxta-medullary glomeruli in aged mice given saline. (L) pERK staining in juxta-medullary glomeruli was lowered in aged mice given SS-31.

(M) Quantitating Collagen IV staining in PECs. In all glomeruli, 8w of SS-31 treatment lowered collagen IV staining in PECs of mice with advanced age.

(N) Quantitating pERK staining in PECs. The percentage of PECs staining for pERK was lower in SS-31 treated aged mice in both regions of the cortex. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation.

These results indicate that glomeruli in aged animals treated with SS-31 show reduced markers for PEC pro-fibrotic activation.

Collagen IV

In aged mice, collagen IV accumulation is increased along Bowman’s capsule (12). In saline treated 26m animals, 45% of glomeruli in the outer cortex and 77% in the JM had expansion of collagen IV matrix (Figure 6E, G, M). In contrast, in age-matched animals treated with 8w of SS-31, 32% of glomeruli in the OC and 56% in the JM had expanded collagen IV staining along Bowman’s capsule. (Figure 6F, H, M). These results, along with the α-SMA data, show that extracellular matrix accumulation in aged kidneys derived from PECs from 24m to 26m of age, was prevented by SS-31.

pERK

We next asked if changes in Collagen IV expression was accompanied by changes in CD44 and phosphorylated ERK, as both have been implicated in increased matrix accumulation in PECs (12, 41, 42). As previously reported (12), CD44 stained PECs were readily detected in aged baseline 24m-old mice in OC and JM glomeruli but the percentage of CD44 stained PECs in either glomerular compartment was not different between 26m-old mice with either saline or SS-31 for 8w (data not shown). Phosphorylated-ERK (pERK), the active form of ERK, is not detected in PECs in young mice, but is increased in PECs in old mice (12). SS-31 treatment resulted in a significantly lower number of PECs staining for pERK in OC glomeruli (SS-31 = 27.60% vs. Saline = 46.75%, P = 0.0035 vs. saline) and in JM glomeruli (SS-31 = 30.4% vs. Saline = 53.00%, P = 0.0018 vs. saline) (Figure 6I–L & N). These results show a differential effect of SS-31 on pERK and CD44 in aged PECs. SS-31 treatment in aged mouse kidneys is associated with higher PEC density but a lower PEC activation.

SS-31 treatment did not restore podocyte number

We have shown that the age-related decline in podocyte number is significant in middle-aged mice by 12m of age in mice (43). To determine if SS-31 had an effect on podocyte number, cells were identified by nuclear p57 staining. Both glomerular tuft volume and glomerular tuft area were measured to calculate podocyte density (Figure 7). In OC glomeruli, absolute podocyte number was not different between groups (Figure 7B). In the SS-31 treated mice however, glomerular tuft volume was higher, resulting in an overall lower podocyte density in OC glomeruli (Figure 7E). In JM glomeruli, podocyte density was not statistically different between 24m-old mice, and 26m-old mice given saline or SS-31 (Figure 7E).

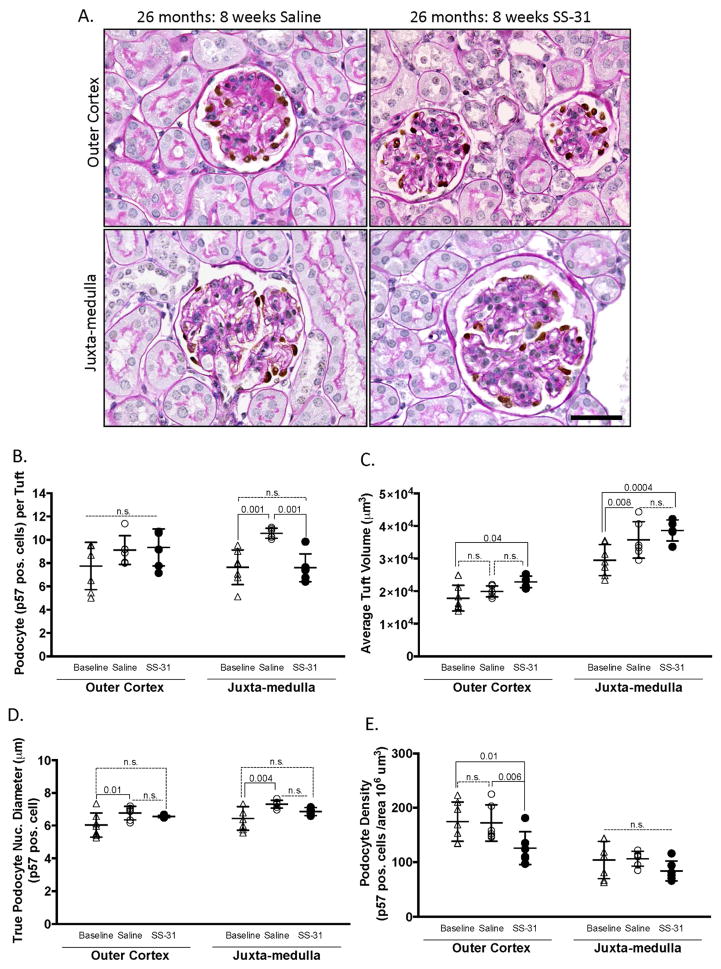

Figure 7. Podocyte number is not altered by SS-31 in aged mice.

(A) PAS/p57 staining. Representative images of periodic acid–Schiff stained (PAS) kidney sections from SS-31 and saline treated 26m-old mice counter stained with hematoxylin for nuclei (blue), and p57 immunohistochemistry (brown) to identify and quantitate podocytes in glomeruli in the outer cortex and juxta-medulla.

(B) Quantitation of podocyte number. The average podocyte number per tuft, identified by p57 stained cells, did not differ between groups in the glomeruli of the outer cortex. In juxta-medullary glomeruli, saline treated animals had significantly higher podocyte number per tuft than either baseline or SS-31 treated animals.

(C) Average tuft volume. In glomeruli of the outer cortex, saline had no impact, whereas SS-31 treated animals had a larger tuft volume compared to baseline. In juxta-medullary glomeruli, tuft volume was larger in both saline and SS-31 treated aged mice compared to baseline.

(D) Podocyte size. The average podocyte nuclear diameter (μm) was used to measure podocyte size. In both glomerular compartments, 26m-old saline treated mice had significantly larger podocytes compared to 24m-old baseline mice. In contrast, podocyte size in aged mice given SS-31 did not increase relative to baseline animals. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. These results show that SS-31 did not alter podocyte density, but reduced podocyte hypertrophy.

(E) Podocyte density. In outer cortical glomeruli, podocyte density was lower in SS-31 treated mice, coinciding with a higher tuft volume in this group of aged mice (panel C). There were no differences in podocyte density in juxta-medullary glomeruli between baseline mice, and aged mice given saline or SS-31.

The diameter of podocyte nuclei was measured to assess hypertrophy as described by Wiggins (44). In OC glomeruli, podocyte diameter increased significantly from 24m to 26m of age in saline treated mice (Figure 7D). Although OC podocyte diameter was lower in SS-31 treated aged mice, this did not achieve statistical significance by ANOVA. Of note, a student’s t-test showed that average podocyte diameter in SS-31 treated kidneys was significantly smaller than that of Saline treated animals (p = 0.0089). Thus, the impact of reducing mitochondrial damage over an 8w period in mice with advanced age was accompanied by partial inhibition of podocyte hypertrophy, but had little effect on podocyte number.

Podocyte integrity is preserved in aged mice given SS-31

The actin-binding protein, synaptopodin, is abundant in healthy podocytes, thereby serving as a marker of cytoskeletal integrity and overall podocyte health (45). To determine whether the slight differences in podocyte nuclear size (Figure 7D) were indicative of podocyte health, all groups were stained for synaptopodin. In both the OC and JM, synaptopodin staining intensity was higher in SS-31 treated animals. Furthermore, synaptopodin staining was more evenly organized across the tuft in SS-31 treated mice (Figure 8A–F). These results are consistent with improved podocyte cytoskeletal integrity in aged mice given SS-31.

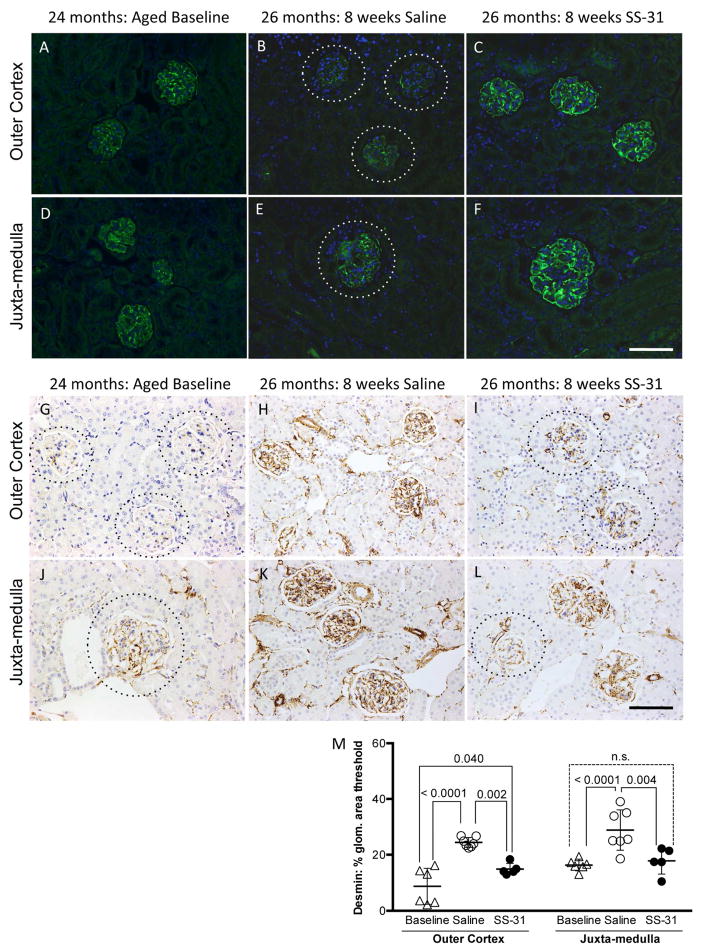

Figure 8. Podocyte integrity is preserved by SS-31 treatment.

(A–F) Synaptopodin staining. Representative images of immunofluorescence for podocyte protein, Synaptopodin (green) and counterstained for nuclei with DAPI (blue). (A) Glomeruli in the outer cortex of 24m-old animals (aged baseline) show even distribution of podocytes across the tuft.

(B) Synaptopodin expression is absent or irregular in tufts (dotted lines encircle tufts to visualize faint staining) of 26m-old aged mice treated with saline whereas in (C) SS-31 treated 26m-old animals have staining of synaptopodin across the entire tuft indicating that podocyte cytoskeleton is preserved by SS-31 treatment. (D–F) Juxta-medulla (JM) staining of synaptopodin to identify podocytes shows a trend similar to that of the outer cortex. (D) JM glomeruli from 24m-old mice have distribution of synaptopodin across the entire tuft indicating even distribution of podocytes.

(E) 26m-old mice treated for 8w with saline have absent or irregular synaptopodin staining across the tuft, indicating loss or injury of podocytes (dotted line encircles tuft to visualize faint staining).

(F) Like baseline animals, 26m-old mice treated with SS-31 have a more extensive pattern of synaptopodin staining across the tuft than that seen in mice treated with saline only, demonstrating preservation of podocyte integrity with age.

(G–L) Desmin Staining. Representative images of immunohistochemistry for podocyte injury marker, Desmin (brown) and counterstained for nuclei with hematoxylin (blue). (G) Outer cortex glomeruli from 24m-old mice show little desmin staining in tufts (dotted lines encircle tuft to visualize glomeruli) whereas (H) 26m-old mice treated for 8w with saline have strong desmin staining across the tuft, indicating extensive podocyte injury. In contrast, (I) 26m-old mice treated with SS-31 have much less prevalent desmin staining in comparison to saline treated animals (dotted lines encircle tufts to visualize faint staining). (J) Desmin staining the juxta-medullar glomeruli of 24m-old baseline animals is higher than in outer cortex of the same animals (dotted lines encircle tufts to visualize faint staining). (K) Desmin staining the juxta-medullar glomeruli of 26m-old saline treated animals is higher than in glomeruli from baseline animals whereas in (L) 26m-old mice treated with SS-31 have less desmin staining in the juxta-medullary tufts than in saline treated mice, indicating that SS-31 treatment prevents podocyte injury.

(M) Quantitation of percentage of Desmin positive area within each glomerulus shows that in the outer cortex 24m-old baseline animals have the least amount of staining and that desmin is significantly higher in 26m-old saline treated animals as compared to baseline and aged SS-31 treated mice. In the juxta-medulla, saline treated mice have significantly more Desmin staining than either 24m baseline or SS-31 treated animals. No difference is seen between 26m-old SS-31 treated and 24m-old baseline animals, demonstrating that SS-31 inhibits age related podocyte damage in the juxta-medulla. Error bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation. These results demonstrate that SS-31 protects podocytes from age-related injury.

Desmin, an intermediate filament protein, is a marker of podocyte injury (46) and increases in podocytes in humans and rodents with advancing age (47, 48). Compared to 24m-old baseline mice, desmin staining was higher in animals aged to 26m with 8w of saline treatment in both OC glomeruli (Baseline = 8.76% vs. Saline = 24.41%, p-value < 0.0001), and in JM glomeruli (Baseline = 16.34% vs. Saline = 28.8%, p-value < 0.0001) (Figure 8M). In OC glomeruli, while desmin staining was higher in both 26m-old treatment groups compared to 24m-old baseline animals (SS-31 = 14.87% area vs. Baseline = 8.76% area, p-value = 0.040), staining was significantly lower in SS-31 treated mice compared to age-matched saline treated animals (p-value = 0.002). Furthermore, in the JM glomeruli SS-31 treatment fully prevented the age-related increase in desmin staining (Baseline = 16.34%, SS-31 = 17.81%).

Transmission electron microscopy showed that saline treated 26m-old mice exhibited podocyte effacement (Supplemental Figure 3). In SS-31 treated mice, podocyte effacement was less marked. These results are consistent with progressive age-associated podocyte injury in the glomeruli in saline treated animals. However, SS-31 lowered podocyte injury as measured by synaptopodin and desmin, which was also evident on TEM.

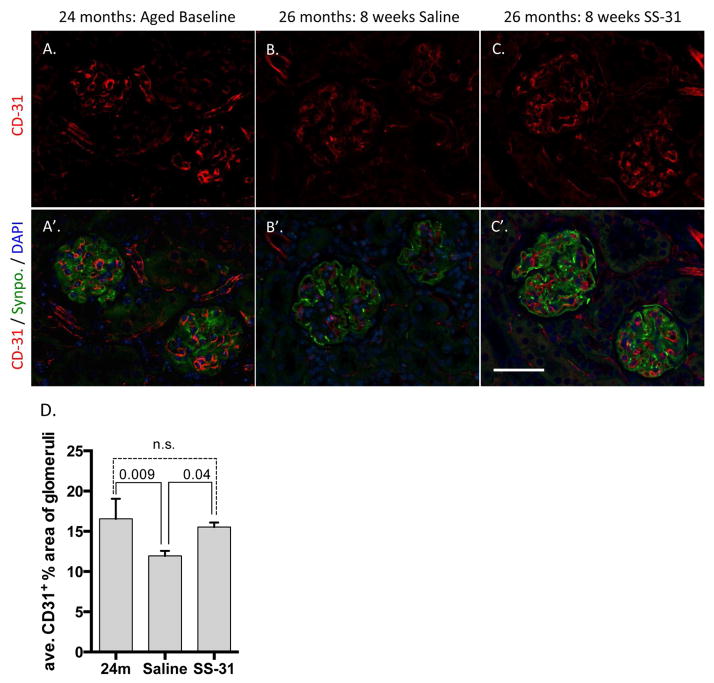

Glomerular capillaries in aged mice are protected by SS-31 treatment

Previous studies of renal ischemia and acute injury models with SS-31 treatment have shown protection of endothelial cells in young adult mice (25). As noted earlier, PAS staining of aged animals showed higher numbers of cortical glomeruli with preserved capillary loop structure following SS-31 treatment (Figure 3). Therefore, to measure capillary integrity we identified capillaries via immunofluorescence of a well-defined endothelial cell surface marker CD-31 (aka, PECAM). Localization of CD-31 staining to the glomerular tuft was confirmed with co-immunostaining for the podocyte marker, synaptopodin. 24m-old aged baseline animals had a higher percentage of CD-31 staining in the tuft compared to 26m-old saline treated animals (Figure 9A and 9B). This indicated that between 24-26 months of age, vascular rarefaction occurred. In 26m-old SS-31 treated animals however, CD-31 staining comprised a larger percentage of the OC glomerular tuft area than saline treated animals. (Baseline = 16.55% +/− 2.49 control =11.95% +/− 0.56% vs. SS-31 = 15.53% +/− 0.45%, p-value = 0.002), indicating endothelial protection with SS-31 peptide treatment (Figure 9A & B).

Figure 9. Glomerular endothelium is protected by SS-31 treatment.

(A–C) Representative images of immunofluorescent CD31 staining for capillaries (red). (A’–C’) Representative images of co-immunoflourescent synaptopodin (Synpo) for podocyte cell bodies (green), CD31 (red) and DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue) in 24m-old untreated mice and 26m-old mice treated with either SS-31 or saline for 8w. Aged baseline (A, A’) and SS-31 (C, C’) treated animals show a more extensive distribution of glomerular capillaries as compared to those treated with Saline (B, B’). (D) Quantification of percentage of CD31 positive area within each glomerulus shows that 24m-old baseline animals and 26m-old SS-31 treated animals have equivalent levels of glomerular endothelial staining in the outer cortex. In contrast, 26m-old saline treated animals have significantly less CD31 staining than either baseline or SS-31 treated animals. These results demonstrate that tuft vasculature is lost between 24m and 26m of age and that SS-31 treatment inhibits the loss of glomerular endothelia. Error bars represent the mean +/- standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Although characteristic glomerular changes have been described in the kidneys of humans and rodents with advanced age, three major questions have remained unanswered: what mechanisms underlie age-related glomerular changes?; can established age-related glomerular changes be attenuated or prevented?; and can degenerative changes at advanced age be partially or fully reversed? In the current study of mice with advanced age (24–28m), equivalent to humans aged 70–90 years, the mitochondrial targeted peptide SS-31 preserved mitochondrial integrity in glomerular epithelial cells, lowered glomerular expression of the ROS generating enzyme Nox4, reduced cellular senescence, increased PEC density while lowering PEC activation, reduced podocyte injury and increased glomerular endothelial capillary integrity. Collectively, these changes across different glomerular cell types were accompanied by a significant reduction in glomerulosclerosis.

Previous studies have shown that in aged mice, SS-31 rapidly restores mitochondrial ATP energetics in skeletal muscle to a more youthful state (49). SS-31 improves outcomes in animal models of age-associated diseases including Parkinson’s disease (50), brain ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease (51, 52). Preservation of cardiolipin by SS-31 protects mitochondria from ischemia-reperfusion injury in a variety of tissue and disease contexts including myocardial and renal ischemia (25, 53–56). Based on the improved mitochondrial structure and function with SS-31 in other tissues, we began by assessing mitochondrial structure in the aged glomerulus using TEM. In 24m-old aged baseline mice in and in 26m-old mice given saline for 8w, a range of mitochondrial changes were detected in podocytes and PECs including loss of cristae, hypertrophy, and membrane rupture. The first major finding of this study was that administering SS-31 to mice of advanced age is accompanied temporally by more densely packed mitochondrial cristae, and more intact outer membranes. These findings are consistent with a decrease in age-associated mitochondrial changes in glomerular epithelial cells, and is therefore the first report to show changes in aged kidneys following treatment with SS-31. In humans, the accumulation rate of age-induced damage is greatest between the ages of 69–80, and potentiates most in highly metabolically active tissues such as the brain, heart and kidney (57). In the kidney, a hallmark of advanced aging damage is glomerulosclerosis (6, 9). Congruent with the human timeline, mice given only saline in the current study had increasing levels of glomerulosclerosis over an 8w period of aging from 24m to 26m. That SS-31 treatment lowered this progression of glomerulosclerosis is a critical finding for two reasons: First, it demonstrates that mitochondria are likely a major contributor to age-accumulated glomerulosclerosis. Second, it shows that even at very advanced age when significant pathological damage has accrued, cellular responses in the glomerulus remain “plastic” enough to allow for interventional protection and improvement.

Because glomerulosclerosis is a pathological change that stems from simultaneous dysfunction in multiple glomerular cell types, and because SS-31 improved the mitochondria of both podocytes and PECs, we parsed out the aging cellular phenotypes within the glomerulus. Several aging studies have focused on a decrease in podocyte density and have shown changes in glomerular volume with age (48, 58). In the current study, glomerular volume and glomerular tuft area were higher in outer cortical glomeruli in mice given SS-31 compared to baseline. However, absolute podocyte numbers were not different at baseline (24m), and in 26m-old mice given saline or SS-31. Therefore, podocyte density was lower in the SS-31 group, because the denominator was larger. We were somewhat surprised that glomerulosclerosis was reduced without an improvement in podocyte density. Several parameters however, demonstrated that SS-31 preserved podocyte integrity. Podocyte nuclear diameter, measured to assess podocyte size (48), was partially preserved by SS-31. Desmin, a marker of podocyte injury that increases with age (46, 47) was reduced in SS-31 treated mice. This was accompanied by preservation of the expression for the actin-binding podocyte protein synaptopodin. Moreover, the TEM results showed less podocyte effacement in aged mice given SS-31 compared to vehicle treated mice. On the whole, the second major finding was that SS-31 treatment did not replace podocytes already depleted at the advanced age of 24m, but rather protected the remaining podocytes from further age-related injury.

The third major finding was that PECs were even more susceptible to SS-31 than podocytes in aged kidneys. We have recently reported that with advancing age PEC density along the Bowman’s capsule decreases, while the remaining PECs show hallmarks of pro-fibrotic activation (12). In the current studies, SS-31 increased PEC density in 26m-old mice to levels significantly above that measured in baseline 24m-old mice. Although we did not inject mice with BrdU, these findings are likely consistent with increased PEC proliferation in SS-31 treated mice. Despite increased density, PEC pro-fibrotic activation measured by pERK, α-SMA and ColIV deposition were markedly reduced by SS-31.

The fourth major finding was that this study established Nox4 expression in aging PECs and that this expression is reduced concurrent with improved mitochondrial structure. In the kidney, NAPDH Oxidases (Nox), and in particular Nox4, are critical for the formation of ROS, which are largely generated by mitochondria. Nox4 is a transmembrane protein that localizes to intracellular membranes, including those of the mitochondria, and constitutively generates superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (36, 59). In diabetic rodent models, increased expression of Nox4 in podocytes and the mesangium has been reported (33, 36) and while PECs staining for Nox4 are detectable in some publications (60, 61), they were not specifically discussed. Nox4 has not yet been extensively studied in the context of kidney aging. Separate work by Hou et al. has shown that Nox4 expression is attenuated in diabetic kidneys treated with SS-31, a finding congruent with our results of SS-31 in aged mice (62).

The fifth major finding was that PECs undergo senescence with age. Recent studies have focused on the role of cellular senescence as a mechanism of renal aging. In the kidney, ablation of p16INK4a positive senescent cells at 12m of age reduced glomerular damage in mice analyzed at 18m (63). In our current study we asked whether the glomerular protection conferred by SS-31 treatment was accompanied by changes in senescent cell accumulation. Although p16 and SA-βgal were both detected at significantly higher levels in aged (24–28m) animals as compared to young (3–5m), SS-31 treatment at late age substantially reduced the expression of both senescent markers in aged animals. Notably, this systemic treatment affected both compartments of the renal cortex and in particular, resulted in reduced p16 expression in PECs. Together these results point to mitochondrial dysfunction as the fulcrum for PEC senescence, an aspect of glomerular biology that warrants further exploration.

We acknowledge some limitations in these studies. First, SS-31 was only administered over an 8w period at late age, when many changes are established. While this has high translational relevance to the aged human population, future studies might be aimed at determining if an earlier course of SS-31 can more completely prevent many kidney age-related changes. Second, mitochondrial changes were measured by semi-quantitiative analysis. However, additional work geared towards quantitative and functional mitochondrial analysis is required to definitively prove that in aged animals SS-31 confers renal protection directly via altered mitochondrial energentics. We suspect that the decrease of Nox4 in tissues treated with SS-31 is an indirect consequence stemming from interruption of redox signaling via reduced mitochondrial ROS, but no other mechanisms of mitochondrial energetics or redox state were studied to directly explain the glomerular changes. That said, the significant decrease in pERK staining in PECs is a candidate pathway to better explain some of the PEC results. In renal fibroblasts, a renal proximal tubule cell line (LLC-PK1) and cardiomyocytes of the heart, Nox4 stimulates autophagy in part by upregulating pERK signaling. This action of Nox4 has been proven by several methods including siRNA (64) (65) and shRNA (37) to inhibit Nox4 expression. We speculate that the partial reduction of Nox4 expression in SS-31 treated PECs is linked to the reduction of pERK expression in these cells.

A third limitation is that the albumin to creatinine ratio was not altered by SS-31. This is likely attributed to the use of C57BL/6J mice (the strain of aged animals provided by the National Institute of Aging) because neither C57BL/6 nor BALB/cBY mouse strains typically exhibit proteinuria with age. Therefore, while we suspect that the extensive histological differences observed in aged mice with SS-31treatment will result in significant functional differences, such studies will require the aging of a different mouse strain. Finally, these studies do not address the potential unintended consequences that come with altering the progression of aging via a systemic treatment. For example, it is known that senescence is one mechanism by which the body attenuates tumorgenic and fibrogenic cellular responses (66). Reducing senescence then, may be accompanied by an increase in tumor formation that is not detected within our timeline.

Beyond the application of SS-31, our current work provides important insight into mitochondrial dysfunction and kidney aging. In our study, even a relatively short course of treatment in extensively aged animals was able to protect multiple cell types of the glomerulus. While this demonstrates the efficacy of SS-31, it also proves that renal aging is informed by mitochondrial function and can be attenuated late in life. Although diabetes and hypertension carry known risks for accelerated renal aging, even in elderly adults with no outward clinical sign of renal dysfunction the risk of sustaining debilitating kidney damage from acute kidney injury increases significantly with age (4, 5). Thus, the findings in this current work have potential implications not only for the attenuation and reversal of glomerular disease, but also of the health span of elderly patients.

METHODS

Animals

Mice were obtained from the National Institute of Aging colony at Charles River. All mice were housed at 20ºC in an AAALAC accredited facility and the University of Washington Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all animal experiments. 24-month-old mice (n = 6) were sacrificed without any intervention to establish an untreated aged baseline in older animals. SS-31 peptide (3 mg/kg/day, n = 7 for 26w male and 28w female sacrifice) or saline (vehicle control n= 6 for 26w male and n= 7 for 28w female sacrifice) were continuously administered for 2–8 weeks using 2 consecutive 4-week subcutaneous osmotic minipumps (Alzet 1004). At the 8-week endpoint, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation by approved personnel, and tissues were collected. The levels of SS-31 in serum were measured by mass spectroscopy and mice with SS-31 containing minipumps had serum SS-31 levels of 0.99 ± 0.40 pmol/μl.

Electron Microscopy

Tissue was immersion fixed in half strength Karnovsky’s solution (1% paraformaldehyde, 1.25% glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.0), post fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, then processed and embedded in Eponate 12 resin using routine protocols. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Jeoul JEM-1230 electron microscope. All visible mitochondria in parietal epithelial cells and podocytes (4-8 cells each) from different animals (n = 3 for 24m, n = 4 for SS-31 and Saline treated mice) were assed for damage semi-quantitatively based on previously published criteria (27) as follows: Score 1 = no major damage, clear inner and outer membranes with dense matrix and densely aligned cristae. Score 2 = Cristae membranes are disrupted with occasional vacuolation, although the matrix largely remains dense. Inner and outer mitochondrial membranes may have separated somewhat. Score 3 = Mitochondrial matrix is largely reduced and few cristae remain. Score 4 = Cristae are mostly absent. Matrix is either absent or very electron dense, outer membrane rupture is seen in some. Score 5 = Triple and quadruple membrane rings indicative of autophagy and/or mitophagy are present. Relative size and density of mitochondria number within each cell was not considered.

Immunohistochemistry

Kidneys were processed as previously described (67, 68). Sections were blocked for endogenous peroxidase (3% hydrogen peroxide) and biotin (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Non-specific antibody binding was blocked with background buster (Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY) except slides prepared for p57 staining were blocked in freshly made 5% nonfat dry milk for 35 minutes. Secondary horseradish peroxidase conjugated antibodies were detected diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich).

Primary Antibodies and Conditions for Immunohistochemistry

Nox4 1:800, antigen retrieval EDTA buffer pH 8, rabbit monoclonal Anti-NADPH oxidase 4 antibody (ab133303, Abcam, Cambridge, MA and Novus Biologicals NB110-58849); p57, rabbit 1:800 antigen retrieval- EDTA buffer pH 6, (anti-p57 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); PAX8, rabbit polyclonal 1:750, antigen retrieval - EDTA buffer pH 6, (anti-paired box gene 8, PAX8; 10336-1-AP, Proteintech Group, Rosemont, IL), and CD44, rat monoclonal 1:50 antigen retrieval - sodium citrate buffer pH 6 (Clone IM7, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Collagen type IV, goat biotinylated 1:200 (1340-08 Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL), pERK, 1:100 rabbit anti-p-p44/42 MAPK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), Desmin, rabbit polyclonal 1:1000, no antigen retrieval (ab15200, Abcam, Cambridge, MA).

Immunofluorescence

All immunofluorescence utilized formalin fixed, paraffin embedded sections. Synaptopodin, pre-diluted mouse monoclonal 1:2, antigen retrieval- sodium citrate buffer pH 6, secondary antibody AlexaFluor 488 Donkey anti-Mouse 1:200 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). CD31, biotinylated rat anti-mouse 1:100, antigen retrieval – sodium citrate buffer pH 6 (PECAM-1/CD31 550274, BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), secondary antibody Alexa594-Streptavidin conjugated 1:200 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Quantitative Real Time PCR

RNA was isolated from renal cortex using the RNeasy®Mini Kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed using the cDNA Archival Kit (Life Technology), and qRT-PCR analysis was performed using SYBRGreen Master Mix, gene-specific primers and ViiA 6 System (Life Technology). The data were normalized to ubiquitin gene (UBC) and levels within each sample and analyzed using the ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences found in Supplemental figure 5.

Quantification of glomerulosclerosis

Blinded sections were stained with periodic-acid Schiff and hematoxylin as well as immunostained for p57. Every glomerulus within one kidney section was ranked on a scale describing the hallmarks of aging-specific glomerulosclerosis of 0-3 with 0 = no injury, 1 = mesangial thickening up to one third of the tuft cross-section and limited or partial Bowman’s capsule thickening; 2 = mesangial thickening greater than 50% of tuft, extensive loss of capillary loop structure and podocytes and more extensive Bowman’s capsule thickening; 3 = entirely sclerotic tufts with little or no podocytes or capillaries visible, mesangium expanded beyond 75% and Bowman’s capsule remnant. The total mean score was calculated as a weighted average individually for kidney cortex compartments (outer cortex and juxta-medulla) quantification was performed on p57/PAS-stained sections as described previously (44). Twenty, 200x fields were obtained for each cortex compartment. An average of 55 ± 9 glomeruli from the outer cortex and 26 ± 6 glomeruli from the juxta-medullary cortex were quantified for each mouse. The diameter of p57 positive cells (podocytes) within each tuft and the area of each tuft was measured by ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) and true diameter calculated using the Venkatareddy-Wiggins method (44).

Quantification of Parietal epithelial cells (PECs)

Twenty, 200x fields, were obtained for each cortical compartment. PECs were identified as cells internally lining the Bowman's capsule and showing strong nuclear staining for Pax8. Capsule length was measured on calibrated images using Image J (National Institute of Health) and excluded tubule cells and vascular poles.

Quantification of Bowman’s capsule expansion

Collagen type IV staining on twenty, 200x fields per cortical compartment was analyzed. Glomeruli were classified in a binary manner with 0 being no capsule thickening and 1 being any visible thickening along the inner surface of the capsule.

Quantification of Phospho-ERK and p16 positive PECs

Twenty, 200x fields per cortical compartment per kidney, by counting the number of cells along the Bowman’s capsule staining darkly. Cells with a brush boarder along the capsule and those within the vascular pole were excluded from all quantification. Negative PECs were those that localized similarly along the Bowman’s capsule but were only stained blue with hematoxylin.

Quantification of Nox4 staining was performed on four low powered (100x) images per kidney. ImageJ (version 1.48, National Institutes of Health) positive binary staining threshold was determined by eye for three sections and then the average threshold applied to all other images automatically to determine the percent of positive area. Image areas lacking tissue were excluded.

Quantification of Desmin

Positive binary staining was determined for five 100x images per cortical compartment per kidney via ImageJ (version 1.48, NIH). Image areas lacking tissue were excluded.

Quantification of CD31 staining

Twenty 200x images per cortical compartment per kidney were quantified with positive binary staining threshold was determined by eye for three sections and then the average threshold applied to all other images automatically to determine the percent of positive area. Image areas lacking tissue were excluded.

Quantification of Senescence-associated-β-galactosidase

Fresh snap-frozen kidneys were cut into thick 8μM sections and stained with SA-β-gal per kit instructions (Cell Signaling Kit #9860) and counter stained with nuclear fast red. Five low power (40x) images per kidney were quantified using ImageJ (version 1.48, National Institutes of Health). Positive binary staining threshold was determined by eye for three sections and then the average threshold applied to all other images automatically to determine the percent of positive area. Image areas lacking tissue were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis used GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). Two-way ANOVA was applied to all analysis with three or more comparison groups. Comparisons between only two treatments were performed with two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test to compare means of groups, and P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: 5 R01 DK 056799-10, 5 R01 DK 056799-12, 1 R01 DK097598-01A1; P01 AG001751, T32 AG000057, and a Breakthrough in Gerontology Award from the American Federation for Aging Research.

Abbreviations

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- PECs

parietal epithelial cells

- pERK

phospho-extracellular signal-related kinase

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- Col IV

collagen type IV

- OC

outer cortex

- JM

juxtamedulla

- PAS

periodic acid-Schiff

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA-β-gal

senescence associated-β-galactosidase

- p16

cylin-dependant kinase inhibitor 2A

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The SS peptide described in this article has been licensed for commercial research and development to Stealth Peptides Inc (now Stealth Biotherapeutics), a clinical stage biopharmaceutical company, in which H.H.S. and the Cornell Research Foundation have financial interests. Dr. Szeto is the inventor of SS-31 and the Scientific Founder of Stealth Biotherapeutics. Dr. Marcinek serves as a scientific consultant to Stealth BioTherapeutics. None of the other authors have any financial or other conflicts of interest. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously, in whole or part.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.System USRD; Diseases NIoDaDaK, editor Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortman JMVV, Hogan H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States. Bureau USC, editor. Current Population Reports 2014;2016 Middle Edition ed. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen G, Bridenbaugh EA, Akintola AD, Catania JM, et al. Increased susceptibility of aging kidney to ischemic injury: identification of candidate genes changed during aging, but corrected by caloric restriction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1272–1281. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00138.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Bonventre JV, Parrish AR. The aging kidney: increased susceptibility to nephrotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 15:15358–15376. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue JL, Daniels F, Star RA, Kimmel PL, et al. Incidence and mortality of acute renal failure in Medicare beneficiaries, 1992 to 2001. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1135–1142. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denic A, Glassock RJ, Rule AD. Structural and Functional Changes With the Aging Kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 23:19–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein JR, Anderson S. The aging kidney: physiological changes. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 17:302–307. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nyengaard JR, Bendtsen TF. Glomerular number and size in relation to age, kidney weight, and body surface in normal man. Anat Rec. 1992;232:194–201. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bitzer M, Wiggins J. Aging Biology in the Kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 23:12–18. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung KY, Dean D, Jiang J, Gaylor S, et al. Loss of N-cadherin and alpha-catenin in the proximal tubules of aging male Fischer 344 rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiggins JE. Aging in the glomerulus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 67:1358–1364. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roeder SS, Stefanska A, Eng DG, Kaverina N, et al. Changes in glomerular parietal epithelial cells in mouse kidneys with advanced age. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 309:F164–178. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00144.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgin JB, Bitzer M, Wickman L, Afshinnia F, et al. Glomerular Aging and Focal Global Glomerulosclerosis: A Podometric Perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol. 26:3162–3178. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiley CD, Velarde MC, Lecot P, Liu S, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Senescence with a Distinct Secretory Phenotype. Cell Metab. 23:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correia-Melo C, Marques FD, Anderson R, Hewitt G, et al. Mitochondria are required for pro-ageing features of the senescent phenotype. EMBO J. 35:724–742. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruse SE, Karunadharma PP, Basisty N, Johnson R, et al. Age modifies respiratory complex I and protein homeostasis in a muscle type-specific manner. Aging Cell. 15:89–99. doi: 10.1111/acel.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, et al. Declining NAD(+) induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell. 155:1624–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuka S, Tatarkova Z, Racay P, Lehotsky J, et al. Effect of aging on formation of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria of rat heart. Gen Physiol Biophys. 32:415–420. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2013049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daum B, Walter A, Horst A, Osiewacz HD, et al. Age-dependent dissociation of ATP synthase dimers and loss of inner-membrane cristae in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110:15301–15306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305462110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrosillo G, Matera M, Moro N, Ruggiero FM, et al. Mitochondrial complex I dysfunction in rat heart with aging: critical role of reactive oxygen species and cardiolipin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szeto HH. First-in-class cardiolipin-protective compound as a therapeutic agent to restore mitochondrial bioenergetics. Br J Pharmacol. 171:2029–2050. doi: 10.1111/bph.12461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birk AV, Liu S, Soong Y, Mills W, et al. The mitochondrial-targeted compound SS-31 re-energizes ischemic mitochondria by interacting with cardiolipin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 24:1250–1261. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012121216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eirin A, Ebrahimi B, Kwon SH, Fiala JA, et al. Restoration of Mitochondrial Cardiolipin Attenuates Cardiac Damage in Swine Renovascular Hypertension. J Am Heart Assoc. 5 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.003118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabbah HN, Gupta RC, Kohli S, Wang M, et al. Chronic Therapy With Elamipretide (MTP-131), a Novel Mitochondria-Targeting Peptide, Improves Left Ventricular and Mitochondrial Function in Dogs With Advanced Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 9:e002206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Wu D, et al. Mitochondria-targeted peptide accelerates ATP recovery and reduces ischemic kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 22:1041–1052. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010080808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szeto HH, Liu S, Soong Y, Alam N, et al. Protection of mitochondria prevents high fat diet-induced glomerulopathy and proximal tubular injury. Kidney Int. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sesso A, Belizario JE, Marques MM, Higuchi ML, et al. Mitochondrial swelling and incipient outer membrane rupture in preapoptotic and apoptotic cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 295:1647–1659. doi: 10.1002/ar.22553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai DF, Chiao YA, Marcinek DJ, Szeto HH, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in aging and healthspan. Longev Healthspan. 3:6. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daiber A. Redox signaling (cross-talk) from and to mitochondria involves mitochondrial pores and reactive oxygen species. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1797:897–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adesina SE, Kang BY, Bijli KM, Ma J, et al. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species to modulate hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med. 87:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bijli KM, Kleinhenz JM, Murphy TC, Kang BY, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma depletion stimulates Nox4 expression and human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation. Free Radic Biol Med. 80:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gomes P, Simao S, Silva E, Pinto V, et al. Aging increases oxidative stress and renal expression of oxidant and antioxidant enzymes that are associated with an increased trend in systolic blood pressure. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2:138–145. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.3.8819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thallas-Bonke V, Jha JC, Gray SP, Barit D, et al. Nox-4 deletion reduces oxidative stress and injury by PKC-alpha-associated mechanisms in diabetic nephropathy. Physiol Rep. 2 doi: 10.14814/phy2.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsushima S, Kuroda J, Ago T, Zhai P, et al. Increased oxidative stress in the nucleus caused by Nox4 mediates oxidation of HDAC4 and cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 112:651–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.279760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuroda J, Nakagawa K, Yamasaki T, Nakamura K, et al. The superoxide-producing NAD(P)H oxidase Nox4 in the nucleus of human vascular endothelial cells. Genes Cells. 2005;10:1139–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Block K, Gorin Y, Abboud HE. Subcellular localization of Nox4 and regulation in diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14385–14390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906805106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sciarretta S, Zhai P, Shao D, Zablocki D, et al. Activation of NADPH oxidase 4 in the endoplasmic reticulum promotes cardiomyocyte autophagy and survival during energy stress through the protein kinase RNA-activated-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase/eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha/activating transcription factor 4 pathway. Circ Res. 113:1253–1264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton ML, Van Remmen H, Drake JA, Yang H, et al. Does oxidative damage to DNA increase with age? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10469–10474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.171202698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kume S, Uzu T, Horiike K, Chin-Kanasaki M, et al. Calorie restriction enhances cell adaptation to hypoxia through Sirt1-dependent mitochondrial autophagy in mouse aged kidney. J Clin Invest. 120:1043–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI41376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Sepassi L, Quiroz Y, Ni Z, et al. Association of mitochondrial SOD deficiency with salt-sensitive hypertension and accelerated renal senescence. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2007;102:255–260. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00513.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eng DG, Sunseri MW, Kaverina NV, Roeder SS, et al. Glomerular parietal epithelial cells contribute to adult podocyte regeneration in experimental focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 88:999–1012. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto T, Sasaki S, Yamazaki T, Sato Y, et al. Prevalence of CD44-positive glomerular parietal epithelial cells reflects podocyte injury in adriamycin nephropathy. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 124:11–18. doi: 10.1159/000357356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pippin JW, Glenn ST, Krofft RD, Rusiniak ME, et al. Cells of renin lineage take on a podocyte phenotype in aging nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 306:F1198–1209. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00699.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkatareddy M, Wang S, Yang Y, Patel S, et al. Estimating podocyte number and density using a single histologic section. J Am Soc Nephrol. 25:1118–1129. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Asanuma K, Kim K, Oh J, Giardino L, et al. Synaptopodin regulates the actin-bundling activity of alpha-actinin in an isoform-specific manner. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1188–1198. doi: 10.1172/JCI23371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Herrmann A, Tozzo E, Funk J. Semi-automated quantitative image analysis of podocyte desmin immunoreactivity as a sensitive marker for acute glomerular damage in the rat puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis (PAN) model. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 64:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maruyama M, Sugiyama H, Sada K, Kobayashi M, et al. Desmin as a marker of proteinuria in early stages of membranous nephropathy in elderly patients. Clin Nephrol. 2007;68:73–80. doi: 10.5414/cnp68073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiggins JE, Goyal M, Sanden SK, Wharram BL, et al. Podocyte hypertrophy, "adaptation," and "decompensation" associated with glomerular enlargement and glomerulosclerosis in the aging rat: prevention by calorie restriction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2953–2966. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegel MP, Kruse SE, Percival JM, Goh J, et al. Mitochondrial-targeted peptide rapidly improves mitochondrial energetics and skeletal muscle performance in aged mice. Aging Cell. 12:763–771. doi: 10.1111/acel.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]