Conspectus

Nucleic acids are a distinct form of sequence-defined biopolymer. What sets them apart from other biopolymers such as polypeptides or polysaccharides is their unique capacity to encode, store, and propagate genetic information (molecular heredity). In nature, just two closely related nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, function as repositories and carriers of genetic information. They therefore are the molecular embodiment of biological information. This naturally leads to questions regarding the degree of variation from this seemingly ideal “Goldilocks” chemistry that would still be compatible with the fundamental property of molecular heredity.

To address this question, chemists have created a panoply of synthetic nucleic acids comprising unnatural sugar ring congeners, backbone linkages, and nucleobases in order to establish the molecular parameters for encoding genetic information and its emergence at the origin of life. A deeper analysis of the potential of these synthetic genetic polymers for molecular heredity requires a means of replication and a determination of the fidelity of information transfer. While non-enzymatic synthesis is an increasingly powerful method, it currently remains restricted to short polymers. Here we discuss efforts toward establishing enzymatic synthesis, replication, and evolution of synthetic genetic polymers through the engineering of polymerase enzymes found in nature.

To endow natural polymerases with the ability to efficiently utilize non-cognate nucleotide substrates, novel strategies for the screening and directed evolution of polymerase function have been realized. High throughput plate-based screens, phage display, and water-in-oil emulsion technology based methods have yielded a number of engineered polymerases, some of which can synthesize and reverse transcribe synthetic genetic polymers with good efficiency and fidelity.

The inception of such polymerases demonstrates that, at a basic level at least, molecular heredity is not restricted to the natural nucleic acids DNA and RNA, but may be found in a large (if finite) number of synthetic genetic polymers. And it has opened up these novel sequence spaces for investigation. Although largely unexplored, first tentative forays have yielded ligands (aptamers) against a range of targets and several catalysts elaborated in a range of different chemistries. Finally, taking the lead from established DNA designs, simple polyhedron nanostructures have been described.

We anticipate that further progress in this area will expand the range of synthetic genetic polymers that can be synthesized, replicated, and evolved providing access to a rich sequence, structure, and phenotypic space. “Synthetic genetics”, that is, the exploration of these spaces, will illuminate the chemical parameter range for en- and decoding information, 3D folding, and catalysis and yield novel ligands, catalysts, and nanostructures and devices for applications in biotechnology and medicine.

Introduction

The natural nucleic acids DNA and RNA serve as the repositories and carriers of genetic information for all life on earth. They may be viewed as a specialized form of aperiodic polymer composed of repeating scaffolds of ribofuranose and phosphodiester units on which the four bases are arranged in a linear sequence, the embodiment of information content (Figure 1). Arguments can be made that this structure is uniquely suited to the task of information storage and readout. These include the unusual kinetic stability of phosphodiester bonds to hydrolysis (compared to other esters including the closely related arsenate diesters),1 the decoupling of physicochemical properties from information content (i.e., nucleotide sequence) due to the dominant influence of the polyanionic phosphodiester backbone, and the extended backbone conformation (facilitating complementary strand pairing and information readout) owing to charge repulsion along the backbone.2 Nevertheless, nucleic acids are not simple linear information strings but can fold into intricate three-dimensional shapes to form specific ligands (aptamers), sensors (riboswitches), and catalysts (ribo- and deoxyribozymes). Thus, within the same molecule, nucleic acids encode genetic information, the genotype (i.e., the sequence of nucleobases), as well as the phenotype (the three-dimensional fold or function) and thus can be evolved directly at the molecular level.3,4

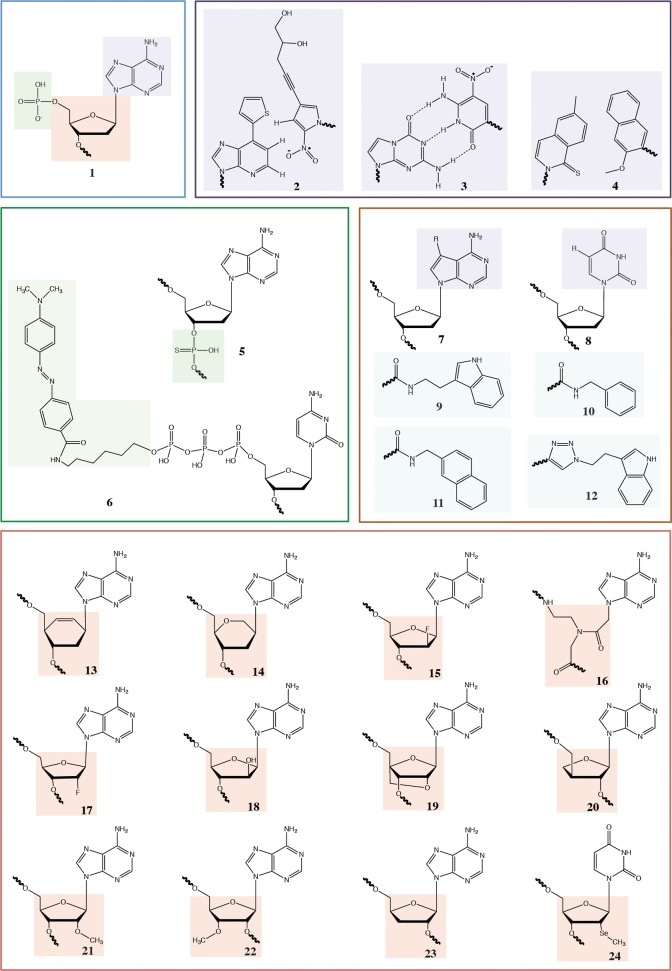

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of functionalized nucleotides, unnatural base pairs and sugars. 1, DNA; 2, Ds:Px; 3, dZ:dP; 4, dNaM:d5SICS; 5, αS-DNA; 6, γ-phosphate-O-linker-dabcyl; 7, N7 position purine; 8, C5 position pyrimidines; 9, tryptamino; 10, benzyl; 11, naphthyl; 12, ethylindole; 13, CeNA; 14, HNA; 15, FANA; 16, PNA; 17, 2′F; 18, ANA; 19, LNA; 20, TNA; 21, 2′OMe; 22, 3′OMe; 23, 2′deoxy; 24, 2′SeMe.

Despite this “Goldilocks” chemistry, variations to all three components (nucleobase, sugar ring, and backbone linkage) are possible and have been systematically explored by synthetic chemists, with a view to finding the critical chemical parameters for molecular information encoding, as well as the chemical etiology of life’s genetic system.5 These fundamental studies have uncovered the profound influence of even minor chemical variations on nucleic acid structure, conformation, and the capacity for helix formation and information transfer. These variations can in turn engender a wide range of non-canonical double helical structures,6 as well as novel useful properties such as increased biostability.7 However, deeper examination of the potential of these candidate genetic polymers for molecular heredity and evolution necessitates a replication system.

Non-enzymatic replication of nucleic acid monomers and oligomers has been explored with a view to understanding the emergence of replication at the origin of life,8,9 as well as enabling the evolution of non-canonical nucleic acid backbones. For example, non-enzymatic replication of peptide nucleic acids (PNA) (16), a potential alternative prebiotic genetic polymer,10 has been explored using tetra-and pentanucleobase PNA units.11 However, although non-enzymatic strategies potentially offer a wide range of chemistries (even beyond the chemical neighborhood of nucleic acids), their limited efficiency and challenges in decoding polymer sequences have so far restricted their application in selection experiments.

We reasoned that enzymatic replication could be immensely powerful, provided the stringent substrate selectivity of natural polymerases could be overcome. If polymerases could be engineered to accept non-cognate nucleotide-triphosphates as substrates at full substitution, they would provide customizable precision nanomachines for the encoded synthesis, replication, and evolution of novel synthetic genetic polymers. Furthermore, enzymatic synthesis and replication of non-canonical nucleic acid substrates by engineered polymerases might illuminate the mechanisms of substrate recognition, discrimination, and fidelity of replication in natural enzymes.

Replication of Modified Nucleotides by Natural Polymerases

Indeed, there are precedents for the efficient incorporation of unnatural substrates whereby chemical modifications on the nucleotide exploit a natural promiscuity of the polymerase active site. For example, modifications to the C5 position of pyrimidines (8) (or C7 (7) of N7-deazapurines) project into the major groove and cause relatively minor clashes with the polymerase or DNA structure even for large and bulky substituents.12,13 Recent examples include incorporation of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated to dTTP by a linker at the C5 position14 and nucleotides conjugated to side chains of the amino acids His, Ser, and Asp.15 SomaLogic has systematically exploited this principle to create Slow-Off-Rate Modified Aptamers (SOMAmers), in which the C5 of dU has been modified to bear a range of hydrophobic substituents (9–11).16 Recent crystal structures of SOMAmers bound to their targets show a remarkable expansion in aptamer functionality, including folding motifs not previously seen in DNA.17 Another route utilizes C5-ethynyl substituted pyrimidines, which are readily incorporated by polymerases (see above) and quantitatively functionalized with an azide-containing substituent using copper dependent azide–alkyne Huisgen cycloaddition (CuAAC) “click-chemistry”. This approach has been validated by the isolation of a DNA aptamer specific for green fluorescent protein, with binding dependent on “clicked” indole substituents (12).18

Another approach is the design of nucleotides that fit the natural polymerase active site either through close geometric and electronic analogy with the canonical system or by an iterative medicinal chemistry approach. Both of these strategies have been successfully applied to the expansion of the genetic alphabet by the creation of novel base pairs; for example, Benner and colleagues devised four novel base pairs by permutation of the H-bond donor and acceptor groups on purine- and pyrimidine-like heterocycles.19 Romesberg and colleagues screened a large number of hydrophobic compounds to eventually arrive at a highly efficient heteropair (4), that adopts native-like planar geometries in the polymerase active site20 and could even persist in vivo when incorporated into a plasmid.21 Using a similar shape complementarity approach, Hirao and colleagues designed artificial base pairs, including Ds and Px (2), which are retained in PCR over 100 cycles22 and have enabled the selection of higher affinity aptamers to a number of targets.23,24

Overcoming Polymerase Substrate Specificity

However, for many non-cognate substrates and indeed to access polymerase phenotypes not found in nature, engineering of novel polymerase variants is preferable. Early polymerase engineering efforts include the rational design of mutants with improved incorporation of dideoxynucleotides25 for Sanger sequencing or improved incorporation of ribonucleotides (NTPs) by removal of the steric gate residue in the polymerase active site that precludes incorporation of nucleotides with a 2′ OH group (or other bulky 2′ substituents) by steric exclusion.26,27 A key mutation for expanding the substrate spectrum of polymerases, A485L, was discovered by scientists at New England Biolabs in the 9°N exo-polymerase28 (commercially sold as Therminator) and is transferable to a range of polB family polymerases. Although its mechanistic basis remains obscure, the Therminator mutation appears to improve the incorporation of a wide range of non-cognate substrates29−31 and, together with adjacent residues, provides the key to enabling Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) on the Illumina platform.32

Polymerase variants with desirable properties can be discovered by selection (see below) or screening approaches (Figure 2), including in vivo complementation,33 high-throughput liquid-handling,34 or polymerase arrays.35 These approaches have yielded polymerases with useful properties including increased NTP incorporation,36,37 RNA reverse transcriptase (RT) activity,38 or 2′SeMeUTP (24) incorporation,39 improved discrimination against mismatches40 or epigenetic methylation marks,41 or, as a result of screening variants of T7 RNA polymerase, a mutant efficient at transcribing all four 2′OMethyl (21) (2′OMe) nucleotides.42

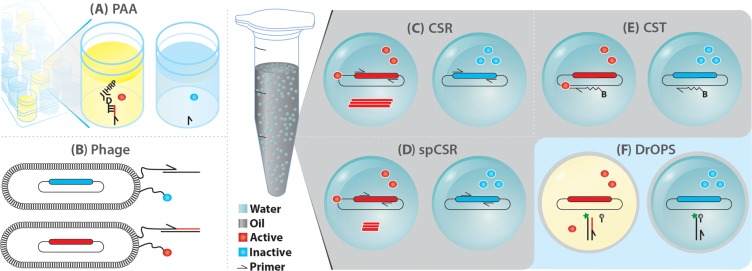

Figure 2.

Methods for screening unnatural polymerase activities: (A) PAA; (B) Phage. Yellow solution indicates soluble product is formed. Emulsion techniques for polymerase selection: (C) CSR, (D) spCSR, (E) CST, and (F) DrOPS. Fluorescent droplets indicated in yellow. B = biotin; D = digoxigenin.

We developed an ELISA-like screening assay for polymerase function (polymerase activity assay, PAA) based on the capture of an extended biotinylated primer on a streptavidin surface followed by readout using a complementary digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled oligonucleotide and an anti-DIG HRP-conjugated antibody (Figure 2A).43 PAA proved useful in identifying hits postselection30,43−45 or for screening saturation mutagenesis libraries at positions identified by rational design or bioinformatic analysis (see below).

In Vitro Selection Technologies for Polymerase Evolution

Larger polymerase repertoires can be examined using selection technologies such as phage display, whereby the polymerase and primer/template substrate are tethered proximally on the phage tip (Figure 2B).4,46 These approaches have identified polymerases with novel properties including RT activity,47 improved NTP or 2′OMe-dNTP incorporation, and improved extension of a PICS–PICS unnatural base pair.48 Recent improvements to the phage display method include expressing an unnatural amino acid, p-azidophenylalanine, on the pIII protein allowing a cycloalkyne-primer/template duplex to be attached by CuAAC click chemistry.49 This improved display method yielded a Stoffel fragment mutant with the ability to transcribe fully modified 2′-OMe templates (60mer) and also reverse transcribe into DNA. Remarkably, another selected polymerase enabled PCR amplification with partial substitution of dNTPs with 2′OMe-dATP or 2′F-purines (17).

We sought to develop methodologies for the directed evolution of polymerases, where polymerase function could be interrogated in solution. The first selection strategy we developed, compartmentalized self-replication (CSR),3 is based on a feedback loop, whereby the polymerase replicates its own encoding gene within the aqueous compartments of a water-in-oil (w/o) emulsion (Figure 2C). In such a system, each polymerase replicates only its own encoding gene (to the exclusion of those in other compartments) and adaptive gains by the polymerase translate into an increase in the postselection copy number of the encoding gene. We developed thermostable emulsion mixtures that allowed selection of self-replicating polymerases during PCR thermocycling3 as well as emulsion PCR approaches used in several NGS and digitial PCR platforms.50

CSR has proven a versatile method at evolving enzymes for different activities including polymerases with increased thermostability3 and resistance to potent polymerase inhibitors such as the anticoagulant heparin3 or a range of environmental inhibitors such as humic acid.51 CSR also proved useful for the identification of polymerases with an expanded substrate spectrum including variants capable of PCR amplification from damaged DNA52 or of amplifying DNA with complete substitution of dNTPs with phosphorothioate (αS)-dNTPs (5) thus creating all αS-DNA53 or with a generic ability to extend or replicate large hydrophobic base analogues.45 This polymerase also displayed a significantly enhanced ability to copy and PCR amplify bisulfite treated DNA, possibly due to an enhanced capacity to utilize dU as well as the bisulfite adduct 5,6-dihydrouridine-6-sulfonate (dhU6S) as template base and decode them correctly as dT.54 This may enhance sensitivity and efficiency in the bisulfite sequencing workflow, a key methodology in epigenomics.

CSR has also been used successfully by a number of other groups and biotechnology companies for the discovery of novel polymerases, for example, in the isolation of Pfu mutants capable of incorporating nucleotides bearing a bulky γ-phosphate-O-linker-dabcyl substituent (6).55 CSR also proved useful in evolving polymerases for the expansion of the genetic alphabet by improved incorporation of the unnatural base dZTP opposite its cognate dP template (3).56 In a similar approach CSR was used to evolve RT activity using chimeric RNA–DNA primers requiring reverse transcription through the RNA portion for self-replication.57 The most proficient RT demonstrated 3-fold improved fidelity compared to natural RTs. The selected polymerase was also able to reverse transcribe a 2′OMe template albeit with greatly reduced activity compared to its RNA reverse transcriptase activity.

CSR has been adapted to improve the thermostability of a mesophilic polymerase from the Bacillus subtilis phage Φ29 (Phi29).58 Phi29 is a replicative polymerase with high fidelity, exceptional processivity and strong strand displacement activity with important applications in whole genome amplification and single molecule sequencing.32,59 By freeze–thawing bacterial cells for lysis within a w/o compartment, the typical heat lysis step could be circumvented. Multiple displacement amplification of plasmids encoding Phi29 variants in emulsion allowed enrichment of library members with greater activity at higher temperatures. An evolved Phi29 mutant maintained activity at 40 °C and generated up to five times more product than wild type (wt) Phi29.58 Furthermore, deep sequencing of whole genome amplification products generated by the mutant polymerase displayed sequence coverage with reduced bias compared to wt Phi29.

CSR requires full replication of the >2kb polymerase genes, thereby imposing a rigorous adaptive burden restricting recovery to only the most active polymerases. To increase the sensitivity of the method, we devised short-patch CSR (spCSR), in which both diversification and self-replication is limited to a short, defined segment of the polymerase gene (Figure 2D). spCSR has allowed the isolation of variants of Taq with an expanded substrate spectrum allowing enhanced incorporation and replication of 2′-substituted nucleotides43 as well as a variant of Pyrococcus furiosus DNA polymerase (Pfu), capable of complete replacement of dCTP with the fluorescent dye labeled nucleotides Cy3- and Cy5-dCTP in PCR.44 The resulting CyDNA is brightly colored and highly fluorescent due to the dense display of cyanine heterocycles on the DNA helix. It also exhibits significantly altered physicochemical properties, including organic phase partitioning during phenol extraction and a 40% increased diameter as determined by atomic force microscopy.44 CyDNA probes allowed significant signal gains in microarray applications and show promise for applications in super-resolution microscopy.60

We have continued technology development in the areas of polymerase evolution and design specifically for the detection and evolution of very weak and nonprocessive polymerase activities with challenging substrates. To this end, we have developed compartmentalized self-tagging (CST).30 CST is based on a positive feedback loop, whereby a polymerase tags its own encoding gene (or rather the plasmid containing said gene) by extension of a metastable biotinylated oligonucleotide primer (Figure 2E). Extension stabilizes the oligonucleotide–plasmid complex and enables the selective capture of plasmids encoding active polymerases. In contrast to CSR and spCSR, CST decouples selection from self-replication; thus recovery of a synthetic polymerase is not dependent on simultaneous RT activity within the same polymerase. We have systematically optimized CST working parameters for selection efficiency and sensitivity.61 For even higher sensitivity, we developed compartmentalized bead tagging (CBT) with sensitivities below single turnover events per polymerase molecule, which was validated during the selection for improved RNA polymerase ribozymes.62

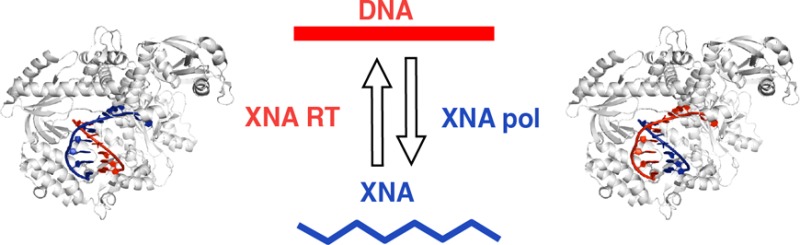

CST proved a key enabling technology for the discovery of polymerases for synthetic genetic polymers with entirely unnatural backbones.30 In these xeno-nucleic acids (XNAs), the canonical ribofuranose ring structure found in DNA or RNA is replaced with synthetic congeners. Specifically, we examined HNA (14, 1,5 anhydrohexitol nucleic acid), CeNA (13, cyclohexenyl nucleic acids), LNA (19, 2′-O,4′-C-methylene-β-d-ribonucleic acids; locked nucleic acids), ANA (18, arabinonucleic acids), FANA (15, 2′-fluoro-arabinonucleic acid), and TNA (20, α-l-threofuranosyl nucleic acids), which has been proposed as a predecessor to the RNA world.63

To expedite the discovery of XNA polymerase activities, we created 22 separate repertoires of Tgo, a polB family DNA polymerase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus gorgonarius. Diversity comprising phylogenetic variability as well as targeted random mutations at conserved positions was focused on short sequence motifs located within 10 Å of the nascent DNA strand and its hydration shell as modeled in the tertiary complex of the related polB family DNA polymerase from phage RB69. Together with the CST and PAA methods, this enabled the discovery of efficient XNA synthetases for all six XNAs.30

To pinpoint potential key residues involved in XNA RT function, we used statistical coupling analysis (SCA)64 of polB phylogeny to identify functionally important residues. Rooting SCA analysis to the vicinity (5 Å) of L408, a residue implicated in RNA RT activity in the related Pfu DNA polymerase,65 we identified a single point mutation (I521L) in Tgo that displayed RT activity for several XNAs. The same mutation also provided proficient TNA synthesis and RT activity in the same polymerase framework.30

Prior to us, TNA synthesis and reverse transcription had been investigated by Szostak and Chaput.66,67 Initially Therminator polymerase was shown to be adept at transcribing a defined DNA template into TNA68 but failed to synthesize unbiased random TNA repertoires comprising all four nucleotides. However, using a three letter TNA alphabet (tA, tG, tT) and a TNA-display approach69 Chaput and colleagues were able to isolate TNA aptamers against thrombin. To improve TNA synthesis and generality, they recently developed a microfluidic double emulsion droplet-based optical polymerase sorting method (DrOPS) to evolve polymerases.70 DrOPS involves encapsulation of an Escherichia coli cell expressing polymerase in a w/o droplet with TNA triphosphates and a DNA primer–template duplex (Figure 2F). After TNA synthesis, a second encapsulation step is employed to generate double emulsions. TNA products are detected using a fluorescent read-out allowing double emulsions to be sorted by flow cytometry. Focused libraries of 9°N DNA polymerase at positions that had previously been shown to expand the substrate specificity of Tgo30 and 9°N28 yielded TNA polymerases with improved activity and ∼40-fold higher fidelity.

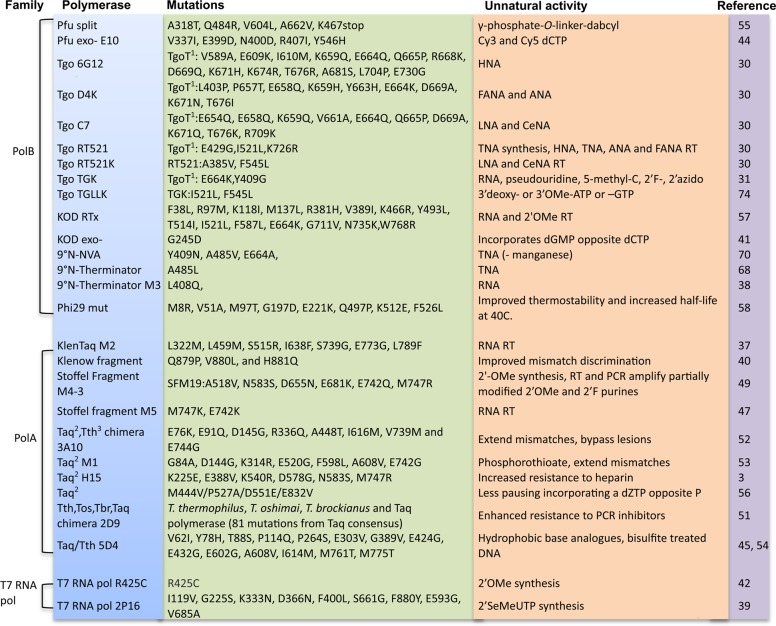

Polymerase engineering experiments have also revealed key aspects of polymerase function (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Positions in engineered polymerases found to expand their substrate spectrum. (1) TgoT, Tgo with additional mutations to V93Q, D141A, E143A, and A485L. (2) T. aquaticus (Taq), (3) T. thermophilus (Tth), (4) T. brockianus (Tbr), (5) T. oshimai (Tos).

Specifically, CST and SCA approaches have begun to map out the broad structural features critical for processive XNA synthesis and XNA reverse transcription. Key mutations enabling XNA synthesis were found to cluster predominantly in the polymerase thumb subdomain in proximity to the nascent strand but unexpectedly distant (>20 Å) from the polymerase active site. We hypothesized that these mutations likely reshape a postsynthetic checkpoint region in the thumb domain. Indeed, careful dissection of selected mutations enabled the optimization of XNA as well as RNA polymerase activity.31 Key to the engineering of the RNA polymerase activity was the identification of a critical gatekeeper mutation (E664K) in the thumb domain, which together with the steric gate mutation (Y409G) yielded a processive primer-dependent RNA polymerase from a DNA polymerase scaffold in just two mutational steps (TGK).31 Primer dependent RNA synthesis is useful for example for the generation of mRNAs with defined cap structures and post-transcriptional modifications such as m6Am.71 Combination of the E664K gatekeeper mutation with the previously identified I521L mutation in Tgo (RT521K) also yielded reverse transcriptase activity on LNA and CeNA.30

While nucleic acids generally exhibit exclusively 3′–5′ phosphodiester backbone linkages, regioisomeric 2′–5′ linkages have been identified in nature and are involved in innate immune signaling.72 The 2′–5′ linkages destabilize the DNA or RNA duplexes and have been postulated to facilitate primordial RNA replication and evolution.73 Starting from the processive RNA polymerase TGK (see above), we discovered a polymerase that was capable of synthesizing DNA and RNA with site-specific regioisomeric 2′–5′ linkages by full replacement of dATP or dGTP with the corresponding 3′deoxy- (23) or 3′OMe-ATP or -GTP (22) nucleotides.74 Taq, avian myleoblastosis virus RT, and RT521K were adept at reverse transcribing partial 2′–5′-DNA and -RNA to canonical 3′–5′-DNA demonstrating genetic interconversion of 2′–5′ linkages to canonical 3′–5′ linkages in DNA and RNA.

Applications of Synthetic Genetic Polymers

The ability to synthesize and reverse transcribe XNAs demonstrated a capacity for genetic information storage and propagation—molecular heredity—beyond the natural nucleic acids DNA and RNA. This also enabled an XNA replication cycle progressing through a DNA intermediate (conceptually similar to retroviral replication) and opened up the novel XNA sequence spaces for exploration and Darwinian evolution. As a stringent test for evolution and the acquisition of higher order functions such as folding and specific ligand binding, we initiated selection of XNA aptamers directly from diverse repertoires of XNA sequences. We obtained multiple HNA aptamers directed against the HIV-TAR RNA motif or hen egg lysozyme (HEL), which bind their targets with high affinity and specificity.30 DeStefano and colleagues exploited XNA polymerases for aptamer isolation, including a FANA aptamer that binds to HIV RT with picomolar affinity.75

The demonstration that XNAs can fold into defined three-dimensional structures and bind to diverse ligands with high affinity encouraged us to investigate whether XNAs could also support the evolution of catalysts. Indeed, we were able to discover a range of XNA catalysts (XNAzymes). These included RNA endonucleases elaborated in four different chemistries (ANA, FANA, HNA, and CeNA), an RNA ligase in the FANA system, and an XNA–XNA (FANA–FANA) ligase metalloenzyme (dependent on Zn2+ and Mg2+).76 These results demonstrated catalysis in synthetic genetic polymers not found in nature and established technologies for the discovery of catalysts in a wide range of polymer scaffolds. XNA aptamers and catalysts exhibit increased resistance to nuclease degradation, which increases their potential for in vivo applications in comparison to DNA or RNA equivalents. XNA also provides the potential to open up more structural space with expanded motifs in aptamer or catalyst libraries.

Finally, we have recently been able to exploit the synthetic power of the engineered polymerases to synthesize and assemble the building blocks for nanostructures composed entirely of XNAs, such as the classic “Turberfield” tetrahedron elaborated in a range of chemistries including 2′F-RNA, FANA, HNA, and CeNA, as well as a FANA octahedron requiring synthesis of a 1.7kb FANA “origami” strand for assembly.77

Future advances in methodologies for the synthesis, replication, and evolution of chemically ever more divergent genetic polymers should help to resolve questions such as the comparative phenotypic richness of the respective XNA versus DNA/RNA sequence spaces. We anticipate that such advances will also yield an increasing range of XNA catalysts and ligands that fully exploit their expanded range of physicochemical properties and biostability with potential applications ranging from medicine to nanotechnology.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support by the Medical Research Council (G.H. and P.H., program no. MC_U105178804) and an MRC-AstraZeneca/MedImmune Blue Sky Grant supporting the salary of S.A.-F.

Biographies

Gillian Houlihan graduated from University College Dublin (Ireland) and obtained her Ph.D. with Florian Hollfelder at the University of Cambridge (U.K.). She joined Philipp Holliger’s research group at the LMB as a postdoctoral researcher. Currently, her research focuses on polymerase engineering for synthetic genetics.

Sebastian Arangundy-Franklin graduated from Rutgers University (USA) before joining the laboratory of Philipp Holliger at the LMB for his Ph.D. and postdoctoral studies. His current research is centered on applications relating to synthetic genetics.

Philipp Holliger graduated from ETH Zürich (Switzerland) before moving to Cambridge (U.K.) for his Ph.D. and postdoctoral studies with Sir Greg Winter. Currently he is a Program Leader at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge (U.K.). His research spans the fields of chemical biology, synthetic biology, and in vitro evolution.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published ASAP on April 6, 2017, with an error in Figure 2. The corrected version reposted with the issue on April 18, 2017.

References

- Westheimer F. H. Why nature chose phosphates. Science 1987, 235, 1173–1178. 10.1126/science.2434996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner S. A. Understanding nucleic acids using synthetic chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 784–797. 10.1021/ar040004z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadessy F. J.; Ong J. L.; Holliger P. Directed evolution of polymerase function by compartmentalized self-replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 4552–4557. 10.1073/pnas.071052198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fa M.; Radeghieri A.; Henry A. A.; Romesberg F. E. Expanding the substrate repertoire of a DNA polymerase by directed evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 1748–1754. 10.1021/ja038525p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenmoser A. Chemical etiology of nucleic acid structure. Science 1999, 284, 2118–2124. 10.1126/science.284.5423.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anosova I.; Kowal E. A.; Dunn M. R.; Chaput J. C.; Van Horn W. D.; Egli M. The structural diversity of artificial genetic polymers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 1007–1021. 10.1093/nar/gkv1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein F.; Gish G. Phosphorothioates in molecular biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1989, 14, 97–100. 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce G. F.; Inoue T.; Orgel L. E. Non-enzymatic template-directed synthesis on RNA random copolymers. Poly(C, U) templates. J. Mol. Biol. 1984, 176, 279–306. 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90425-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamala K.; Szostak J. W. Nonenzymatic template-directed RNA synthesis inside model protocells. Science 2013, 342, 1098–1100. 10.1126/science.1241888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson K. E.; Levy M.; Miller S. L. Peptide nucleic acids rather than RNA may have been the first genetic molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 3868–3871. 10.1073/pnas.97.8.3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brudno Y.; Birnbaum M. E.; Kleiner R. E.; Liu D. R. An in vitro translation, selection and amplification system for peptide nucleic acids. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010, 6, 148–155. 10.1038/nchembio.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeid S.; Baccaro A.; Welte W.; Diederichs K.; Marx A. Structural basis for the synthesis of nucleobase modified DNA by Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 21327–21331. 10.1073/pnas.1013804107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen K.; Steck A. L.; Strutt S.; Baccaro A.; Welte W.; Diederichs K.; Marx A. Structures of KlenTaq DNA polymerase caught while incorporating C5-modified pyrimidine and C7-modified 7-deazapurine nucleoside triphosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 11840–11843. 10.1021/ja3017889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welter M.; Verga D.; Marx A. Sequence-Specific Incorporation of Enzyme-Nucleotide Chimera by DNA Polymerases. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 10131–10135. 10.1002/anie.201604641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein M. Generation of long, fully modified, and serum-resistant oligonucleotides by rolling circle amplification. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 9820–9824. 10.1039/C5OB01540E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. R.; Gelinas A. D.; Zhang C.; Rohloff J. C.; Carter J. D.; O’Connell D.; Waugh S. M.; Wolk S. K.; Mayfield W. S.; Burgin A. B.; Edwards T. E.; Stewart L. J.; Gold L.; Janjic N.; Jarvis T. C. Unique motifs and hydrophobic interactions shape the binding of modified DNA ligands to protein targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 19971–19976. 10.1073/pnas.1213933109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelinas A. D.; Davies D. R.; Edwards T. E.; Rohloff J. C.; Carter J. D.; Zhang C.; Gupta S.; Ishikawa Y.; Hirota M.; Nakaishi Y.; Jarvis T. C.; Janjic N. Crystal structure of interleukin-6 in complex with a modified nucleic acid ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 8720–8734. 10.1074/jbc.M113.532697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolle F.; Brandle G. M.; Matzner D.; Mayer G. A Versatile Approach Towards Nucleobase-Modified Aptamers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10971–10974. 10.1002/anie.201503652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner S. A.; Karalkar N. B.; Hoshika S.; Laos R.; Shaw R. W.; Matsuura M.; Fajardo D.; Moussatche P. Alternative Watson-Crick Synthetic Genetic Systems. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a023770. 10.1101/cshperspect.a023770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz K.; Malyshev D. A.; Lavergne T.; Welte W.; Diederichs K.; Dwyer T. J.; Ordoukhanian P.; Romesberg F. E.; Marx A. KlenTaq polymerase replicates unnatural base pairs by inducing a Watson-Crick geometry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012, 8, 612–614. 10.1038/nchembio.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyshev D. A.; Dhami K.; Lavergne T.; Chen T.; Dai N.; Foster J. M.; Correa I. R. Jr.; Romesberg F. E. A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet. Nature 2014, 509, 385–388. 10.1038/nature13314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashige R.; Kimoto M.; Takezawa Y.; Sato A.; Mitsui T.; Yokoyama S.; Hirao I. Highly specific unnatural base pair systems as a third base pair for PCR amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 2793–2806. 10.1093/nar/gkr1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto M.; Yamashige R.; Matsunaga K.; Yokoyama S.; Hirao I. Generation of high-affinity DNA aptamers using an expanded genetic alphabet. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 453–457. 10.1038/nbt.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto M.; Matsunaga K.; Hirao I. DNA Aptamer Generation by Genetic Alphabet Expansion SELEX (ExSELEX) Using an Unnatural Base Pair System. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1380, 47–60. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3197-2_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Mitaxov V.; Waksman G. Structure-based design of Taq DNA polymerases with improved properties of dideoxynucleotide incorporation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 9491–9496. 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P. H.; Loeb L. A. Multiple amino acid substitutions allow DNA polymerases to synthesize RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 40266–40272. 10.1074/jbc.M005757200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astatke M.; Ng K.; Grindley N. D.; Joyce C. M. A single side chain prevents Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) from incorporating ribonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 3402–3407. 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A. F.; Jack W. E. Acyclic and dideoxy terminator preferences denote divergent sugar recognition by archaeon and Taq DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 605–613. 10.1093/nar/30.2.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida J. K.; Horhota A.; Zou K.; McLaughlin L. W.; Szostak J. W. High fidelity TNA synthesis by Therminator polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 5219–5225. 10.1093/nar/gki840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro V. B.; Taylor A. I.; Cozens C.; Abramov M.; Renders M.; Zhang S.; Chaput J. C.; Wengel J.; Peak-Chew S. Y.; McLaughlin S. H.; Herdewijn P.; Holliger P. Synthetic genetic polymers capable of heredity and evolution. Science 2012, 336, 341–344. 10.1126/science.1217622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozens C.; Pinheiro V. B.; Vaisman A.; Woodgate R.; Holliger P. A short adaptive path from DNA to RNA polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 8067–8072. 10.1073/pnas.1120964109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro V. B.; Ong J. L.; Holliger P.. Polymerase Engineering: From PCR and Sequencing to Synthetic Biology; Wiley & Sons: Weinheim, 2013; Vol. III, p 12. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M.; Baskin D.; Hood L.; Loeb L. A. Random mutagenesis of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I: concordance of immutable sites in vivo with the crystal structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996, 93, 9670–9675. 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerer D.; Marx A. A molecular beacon for quantitative monitoring of the DNA polymerase reaction in real-time. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3620–3622. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranaster R.; Marx A. Taking fingerprints of DNA polymerases: multiplex enzyme profiling on DNA arrays. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4625–4628. 10.1002/anie.200900953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P. H.; Loeb L. A. DNA polymerase active site is highly mutable: evolutionary consequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000, 97, 5095–5100. 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger N.; Marx A. A DNA polymerase with increased reactivity for ribonucleotides and C5-modified deoxyribonucleotides. ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 1963–1966. 10.1002/cbic.201000384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter K. B.; Marx A. Evolving thermostable reverse transcriptase activity in a DNA polymerase scaffold. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7633–7635. 10.1002/anie.200602772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund V.; Santner T.; Micura R.; Marx A. Screening mutant libraries of T7 RNA polymerase for candidates with increased acceptance of 2′-modified nucleotides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9870–9872. 10.1039/c2cc35028a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerer D.; Rudinger N. Z.; Detmer I.; Marx A. Enhanced fidelity in mismatch extension by DNA polymerase through directed combinatorial enzyme design. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4712–4715. 10.1002/anie.200500047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber C.; von Watzdorf J.; Marx A. 5-methylcytosine-sensitive variants of Thermococcus kodakaraensis DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 9881–9890. 10.1093/nar/gkw812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibach J.; Dietrich L.; Koopmans K. R.; Nobel N.; Skoupi M.; Brakmann S. Identification of a T7 RNA polymerase variant that permits the enzymatic synthesis of fully 2′-O-methyl-modified RNA. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 167, 287–295. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong J. L.; Loakes D.; Jaroslawski S.; Too K.; Holliger P. Directed evolution of DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase activity in a single polypeptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 361, 537–550. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay N.; Jemth A. S.; Brown A.; Crampton N.; Dear P.; Holliger P. CyDNA: synthesis and replication of highly Cy-dye substituted DNA by an evolved polymerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5096–5104. 10.1021/ja909180c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loakes D.; Gallego J.; Pinheiro V. B.; Kool E. T.; Holliger P. Evolving a polymerase for hydrophobic base analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14827–14837. 10.1021/ja9039696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jestin J. L.; Kristensen P.; Winter G. A method for the selection of catalytic activity using phage display and proximity coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1124–1127. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichier-Guerre S.; Ferris S.; Auberger N.; Mahiddine K.; Jestin J. L. A population of thermostable reverse transcriptases evolved from Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I by phage display. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6133–6137. 10.1002/anie.200601217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leconte A. M.; Chen L.; Romesberg F. E. Polymerase evolution: efforts toward expansion of the genetic code. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12470–12471. 10.1021/ja053322h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.; Hongdilokkul N.; Liu Z.; Adhikary R.; Tsuen S. S.; Romesberg F. E. Evolution of thermophilic DNA polymerases for the recognition and amplification of C2′-modified DNA. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 556–562. 10.1038/nchem.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressman D.; Yan H.; Traverso G.; Kinzler K. W.; Vogelstein B. Transforming single DNA molecules into fluorescent magnetic particles for detection and enumeration of genetic variations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003, 100, 8817–8822. 10.1073/pnas.1133470100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baar C.; d’Abbadie M.; Vaisman A.; Arana M. E.; Hofreiter M.; Woodgate R.; Kunkel T. A.; Holliger P. Molecular breeding of polymerases for resistance to environmental inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e51. 10.1093/nar/gkq1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Abbadie M.; Hofreiter M.; Vaisman A.; Loakes D.; Gasparutto D.; Cadet J.; Woodgate R.; Paabo S.; Holliger P. Molecular breeding of polymerases for amplification of ancient DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 939–943. 10.1038/nbt1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadessy F. J.; Ramsay N.; Boudsocq F.; Loakes D.; Brown A.; Iwai S.; Vaisman A.; Woodgate R.; Holliger P. Generic expansion of the substrate spectrum of a DNA polymerase by directed evolution. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 755–759. 10.1038/nbt974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar D.; Christova Y.; Holliger P. A polymerase engineered for bisulfite sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e155. 10.1093/nar/gkv798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C. J.; Wu L.; Fox J. D.; Arezi B.; Hogrefe H. H. Engineered split in Pfu DNA polymerase fingers domain improves incorporation of nucleotide gamma-phosphate derivative. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 1801–1810. 10.1093/nar/gkq1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laos R.; Shaw R.; Leal N. A.; Gaucher E.; Benner S. Directed evolution of polymerases to accept nucleotides with nonstandard hydrogen bond patterns. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 5288–5294. 10.1021/bi400558c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellefson J. W.; Gollihar J.; Shroff R.; Shivram H.; Iyer V. R.; Ellington A. D. Synthetic evolutionary origin of a proofreading reverse transcriptase. Science 2016, 352, 1590–1593. 10.1126/science.aaf5409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Povilaitis T.; Alzbutas G.; Sukackaite R.; Siurkus J.; Skirgaila R. In vitro evolution of phi29 DNA polymerase using isothermal compartmentalized self replication technique. Protein Eng., Des. Sel. 2016, 29, 617–628. 10.1093/protein/gzw052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou D. I.; Hussmann J. A.; McBee R. M.; Acevedo A.; Andino R.; Press W. H.; Sawyer S. L. High-throughput DNA sequencing errors are reduced by orders of magnitude using circle sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 19872–19877. 10.1073/pnas.1319590110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. A.; Holliger P.; Flors C. Reversible fluorescence photoswitching in DNA. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 116, 10290–10293. 10.1021/jp3056834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro V. B.; Arangundy-Franklin S.; Holliger P. Compartmentalized Self-Tagging for In Vitro-Directed Evolution of XNA Polymerases. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2014, 57, 9.9.1–18. 10.1002/0471142700.nc0909s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wochner A.; Attwater J.; Coulson A.; Holliger P. Ribozyme-catalyzed transcription of an active ribozyme. Science 2011, 332, 209–612. 10.1126/science.1200752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoning K.; Scholz P.; Guntha S.; Wu X.; Krishnamurthy R.; Eschenmoser A. Chemical etiology of nucleic acid structure: the alpha-threofuranosyl-(3′-->2′) oligonucleotide system. Science 2000, 290, 1347–1351. 10.1126/science.290.5495.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockless S. W.; Ranganathan R. Evolutionarily conserved pathways of energetic connectivity in protein families. Science 1999, 286, 295–299. 10.1126/science.286.5438.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arezi B. H., Sorge H.; Hansen J. A.; DNA C. J.. Polymerase Mutants With Reverse Transcriptase Activity. US Patent 2003/0228616 A1, December 11, 2003.

- Chaput J. C.; Szostak J. W. TNA synthesis by DNA polymerases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9274–9275. 10.1021/ja035917n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Zhang S.; Chaput J. C. Darwinian evolution of an alternative genetic system provides support for TNA as an RNA progenitor. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 183–187. 10.1038/nchem.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horhota A.; Zou K.; Ichida J. K.; Yu B.; McLaughlin L. W.; Szostak J. W.; Chaput J. C. Kinetic analysis of an efficient DNA-dependent TNA polymerase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 7427–7434. 10.1021/ja0428255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida J. K.; Zou K.; Horhota A.; Yu B.; McLaughlin L. W.; Szostak J. W. An in vitro selection system for TNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 2802–2803. 10.1021/ja045364w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen A. C.; Dunn M. R.; Hatch A.; Sau S. P.; Youngbull C.; Chaput J. C. A general strategy for expanding polymerase function by droplet microfluidics. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11235. 10.1038/ncomms11235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer J.; Luo X.; Blanjoie A.; Jiao X.; Grozhik A. V.; Patil D. P.; Linder B.; Pickering B. F.; Vasseur J. J.; Chen Q.; Gross S. S.; Elemento O.; Debart F.; Kiledjian M.; Jaffrey S. R. Reversible methylation of m6Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature 2017, 541, 371–375. 10.1038/nature21022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ablasser A.; Goldeck M.; Cavlar T.; Deimling T.; Witte G.; Rohl I.; Hopfner K. P.; Ludwig J.; Hornung V. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 2013, 498, 380–384. 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak J. The eightfold path to non-enzymatic RNA replication. J. Syst. Chem. 2012, 3, 2. 10.1186/1759-2208-3-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cozens C.; Mutschler H.; Nelson G. M.; Houlihan G.; Taylor A. I.; Holliger P. Enzymatic Synthesis of Nucleic Acids with Defined Regioisomeric 2′-5′ Linkages. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15570–15573. 10.1002/anie.201508678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves Ferreira-Bravo I.; Cozens C.; Holliger P.; DeStefano J. J. Selection of 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoroarabinonucleotide (FANA) aptamers that bind HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with picomolar affinity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 9587–9599. 10.1093/nar/gkv1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. I.; Pinheiro V. B.; Smola M. J.; Morgunov A. S.; Peak-Chew S.; Cozens C.; Weeks K. M.; Herdewijn P.; Holliger P. Catalysts from synthetic genetic polymers. Nature 2015, 518, 427–430. 10.1038/nature13982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. I.; Beuron F.; Peak-Chew S. Y.; Morris E. P.; Herdewijn P.; Holliger P. Nanostructures from Synthetic Genetic Polymers. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 1107–1110. 10.1002/cbic.201600136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]