Abstract

Objective

Sleep disturbance and sexual dysfunction are common in menopause; however, the nature of their association is unclear. The present study aimed to determine whether sleep characteristics were associated with sexual activity and sexual satisfaction.

Methods

Sexual function in the last year and sleep characteristics (past 4 weeks) were assessed by self-report at baseline for 93,668 women age 50 to 79 years enrolled in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study (OS). Insomnia was measured using the validated WHI Insomnia Rating Scale (WHIIRS). Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) risk was assessed using questions adapted from the Berlin Questionnaire. Using multivariate logistic regression, we examined cross-sectional associations between sleep measures and two indicators of sexual function: partnered sexual activity and sexual satisfaction within the last year.

Results

Fifty-six percent overall reported being somewhat or very satisfied with their current sexual activity and 52% reported partnered sexual activity within the last year. Insomnia prevalence was 31%. After multivariable adjustment, higher insomnia scores were associated with lower odds of sexual satisfaction (yes/no) (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.87-0.96). Short sleep duration (< 7-8 hours) was associated with lower odds of partnered sexual activity (yes/no) (≤ 5 hours OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.80-0.96) and less sexual satisfaction (≤ 5 hours OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.81-0.95).

Conclusions

Shorter sleep durations and higher insomnia scores were associated with decreased sexual function, even after adjustment for potential confounders, suggesting the importance of sufficient, high quality sleep for sexual function. Longitudinal investigation of sleep and its impact on sexual function post-menopause will clarify this relationship.

Keywords: Sexual activity, insomnia, sleep disordered breathing, menopause

Introduction

Sleep disturbance is associated with adverse health outcomes, including but not limited to heart disease, hypertension and depression.1-3 During menopause, women may experience symptoms which can negatively impact sleep quality and cause sleep disturbance. Sexual functioning and satisfaction are also commonly affected during the menopausal transition and post menopause. 4 For many women, adequate sleep and sexual functioning are considered important for physical and psychological wellbeing. However, associations between sleep and sexual function in postmenopausal women are understudied.

Prior work on this topic consists of a few studies that have identified a positive association between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and sexual dysfunction in both pre- and postmenopausal women.5,6,7 It is believed that obesity, menopausal symptoms, including vasomotor symptoms, as well as decreasing hormone levels are associated with decreased sexual function and OSA.5-10 Moreover, many factors can impact both sleep and sexual function such as general health, age, emotional and psychological issues, life events/changes contributing to stress, social support or lack thereof, recent abuse, medications and chronic disease.11-19 For example, data from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) demonstrated a co-occurrence of a triad of menopausal symptoms including sleep disturbance, depressed mood and sexual problems.20

Beyond OSA, few studies have evaluated how other sleep characteristics (e.g., insomnia or sleep duration) may impact sexual function after menopause. A cross-sectional study of 341 Australian postmenopausal women not using menopausal hormone therapy found that 64% of participants had a diminished libido, which was associated with poor sleep.21 In a Turkish study, non-depressive postmenopausal women with insomnia were treated with trazodone and sexual function improved over four weeks demonstrating a potential link between sleep and sexual problems.22 A recent prospective study of healthy college-aged women evaluated the influence of sleep duration, sleep quality and sleep onset latency on daily female sexual response and activity by self-report over 14 days and found that longer sleep duration was related to greater next-day sexual desire and increased odds of sexual activity.23 Although these women were not postmenopausal, the results indicate a possible physiologic link between sleep and sexual function not explained by other comorbidities. To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated how validated insomnia scores, or other sleep risk factors, are associated with sexual function in a large population of postmenopausal women.

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study (OS) offers an opportunity to study how sleep and sexual function are associated in a large cohort of women. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to determine whether self-reported sleep duration, sleep-disordered breathing risk and insomnia assessed using a validated, clinically relevant scale are associated with sexual satisfaction and partnered sexual activity.

Methods

The Women's Health Initiative Observational Study (WHI-OS)

Data were analyzed from postmenopausal women aged 50 - 79 years recruited to the WHI OS at 40 clinical centers throughout the United States from 1994 to 1998. The design and recruitment for the WHI OS has been described previously.24 The study protocol received Institutional Review Board approval at all participating sites and informed consent was collected from all participants. Exclusion criteria for the WHI OS included survival of less than 3 years, participation in other clinical trials, dementia, alcohol abuse, serious mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bi-polar-affective disorder), drug dependency and other medical conditions that precluded adherence and participation.24 Our analyses include data from the baseline assessments of the 93,668 women enrolled, as well as basic demographic and biometric data collected.

Assessment of Sleep Characteristics

Self-reported sleep disturbance was examined utilizing four different variables: sleep duration, insomnia, sleep-disordered breathing and comorbid insomnia and sleep-disordered breathing risk.25

Typical sleep duration

Participants were asked to indicate the number of hours they typically slept each night during the past 4 weeks. Item response choices were 5 or less hours, 6 hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, 9 hours or 10 or more hours. We categorized these into four groups: very short (≤5 hours), short (6 hours), average (7-8 hours), and long (≥9 hours).26,27

WHI Insomnia Rating Scale (WHIIRS)

Insomnia was measured using the validated WHIIRS measure. The 5-item scale includes questions on whether participants had trouble falling asleep, woke up several times at night, woke up too early, had trouble getting back to sleep after awakening early, and overall sleep quality (very sound/restful to very restless). Possible scores on the WHIIRS range from 0 – 20, with scores > 9 indicating high risk for insomnia.28

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB)

SDB was assessed using yes/no questionnaire items for sleep apnea adapted from the Berlin Questionnaire.29,30 One point was given for a “yes” response to any of the following questions: self-reported snoring ≥3 times a week, self-reported falling asleep during quiet activities ≥3 times a week, and either self-reported hypertension or measured obesity (body mass index [BMI]>30kg/m2). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 3 points. Scores ≥2 are considered to be high risk for SBD and <2 low risk.

Comorbid insomnia and sleep disordered breathing

Participants with a high score for both insomnia and sleep disordered breathing, as defined above, were designated as having comorbid insomnia and SDB. Participants with no or only one score above the cutoff for either insomnia or SDB where defined as not having comorbid insomnia and SDB.

Assessment of Sexual Satisfaction and Activity

Our primary outcomes included partnered sexual activity (yes vs. no) and sexual satisfaction (yes vs. no) in the past year. Sexual activity was determined by participants' response to the question “Did you have any sexual activity with a partner in the last year?” Sexual satisfaction was determined by participants' response to the question “How satisfied are you with your current sexual activities, either with a partner or alone?” Available answer choices included very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, a little unsatisfied, very unsatisfied or don't want to answer. We collapsed responses to sexually satisfied (very satisfied and somewhat satisfied) and sexually unsatisfied (a little unsatisfied and very unsatisfied) to create a yes/no outcome variable. Additional sexual activity items included satisfaction with frequency of sexual activity (frequency response choices: less often, satisfied with current frequency, more often or don't want to answer) and whether participants were worried that sexual activity would affect their health (response choices: not at all worried, a little worried, somewhat worried, very worried, don't want to answer).

Other Measures

Baseline self-assessment questionnaires were used to collect information on demographic variables, medical history, lifestyle variables, symptoms, medications and co-morbidities. Variables included in the analysis were age, marital status, family income, race/ethnicity, education level, medical history, physical activity (metabolic equivalent hours/week), self-rated health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), cigarette smoking, alcohol use, previous hysterectomy, vaginal dryness (none, mild, moderate or severe), menopausal hormone therapy use (never, past, or current), frequency of hot flashes and night sweats (did not occur, mild, moderate or severe), antidepressant use including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) use, and sedative hypnotic use, and sleep medication use. Participants also self-reported the presence or absence of the following medical diseases: osteoporosis, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, stroke, presence of cancer (breast, ovarian, and cervical), diabetes, and peripheral arterial disease. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated using the weight and height that had been measured at the baseline visit.

Depression screening was done through a self-report questionnaire using 6 items from the 20 item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D) and 2 items from the National Institute of Mental Health's Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS).31 Score ranged from 0 to 1 with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood of depression. Self-reported socio-behavioral covariates included physical and verbal abuse in the last year (no, yes and it did not upset me too much, yes and it moderately upset me, yes and it upset me very much), as well as the life events scale (assessed number of life events experienced by each participants, e.g. partner loss, score scale 0-11 where a higher score indicates that participants experienced a greater number of life upsetting events),32,33 social strain construct (assessed strain on existing support systems based on measurement of negative aspects of social relationship, score scale 9-45 based on responses to 9 questions where a higher score indicates greater support),34 and social support construct (assessed amount of social support the participant had available, score scale 4-20 based on the response to 4 questions where a higher score indicates greater social strain).35

Statistical Analysis

We examined cross-sectional associations between sleep variables (sleep duration, insomnia, SDB score and comorbid insomnia and SDB) and two indicators of sexual function at baseline: sexual activity with a partner (yes/no) and sexual satisfaction (very satisfied/somewhat satisfied vs. very unsatisfied/a little unsatisfied) within the last year. Dichotomous or categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. We analyzed differences in distributions of dichotomous variables using the Chi-square test. If assumptions for the Chi-square test were not met, we used the Fisher exact test. We summarized continuous variables as means (standard deviations) and medians (interquartile ranges). We used t-tests to analyze differences between distributions of continuous variables. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used instead if assumptions for the t-test were not met.

The cross-sectional association between each risk factor and outcome was evaluated by fitting two multivariate logistic models. The first model adjusted for demographic, physical conditions and medications that can impact sexual function or sleep, or both, and include age, marital status, family income, race/ethnicity, education level, physical activity, self-rated health, antidepressant use including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use, sedative hypnotic use, sleep medication use, depression as assessed by the CES-D/DIS screening instrument, hysterectomy status, smoking status, weight, and alcohol use. The second multivariate model included the variables in model 1 with the addition of variables that could be considered factors that dampen the association between sleep and sexual function which include hot flashes, night sweats, osteoporosis, physical and verbal abuse, life events scale, social strain construct, social support construct, vaginal dryness, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, stroke, cancer (breast, ovarian, and cervical), diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, obesity (BMI >30) and menopausal hormone therapy.

Several secondary analyses were performed using the same logistic regression models mentioned above. We excluded data from women with major chronic diseases, to explore whether adjustment for presence of a chronic disease impacted the relationship between sleep and sexual function. Similarly, we excluded data from women taking antidepressant medication (SSRI, SNRI and sedative hypnotics) to identify if treatment for depression impacted this relationship. We conducted another analysis restricted to women who rated their health as good, very good, or excellent (excluding those who rated their health as fair or poor) to evaluate if perception of health altered the association between sleep and sexual function. An additional analysis was done that had been planned prior to analyses that stratified by women living with a partner or not living with a partner to evaluate the associations of partner availability on sexual activity and satisfaction.

Because partner illness, vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) and menopausal hormone therapy can influence sleep and sexual function,10,12,14,20,21,36-38 we used interaction terms to test whether associations between sleep and sexual function differed by these covariates. We stratified results when interaction terms were statistically significant. Similarly, we included an interaction term to test whether associations between sleep and sexual function differed by 10-year age category.

SAS (version 9.3) was used for data analysis. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participants were on average 63.6 years old and the majority (83.5%) of participants were non-Hispanic White. The mean BMI was 27.3 kg/m2. Selected characteristics of the study population stratified by sexual satisfaction at baseline are displayed in Table 1. Fifty-two percent of the participants reported sexual activity with a partner within the last year and 57% reported being somewhat or very satisfied with their current sexual activities, either alone or with a partner.

Table 1. Demographic and Physiologic Characteristics at Baseline Stratified by Sexual Satisfaction.

| Sexual Satisfaction | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 52,250) | No (N=24,136) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| <50-59 | 17,792 (34.0) | 8,774 (36.4) |

| 60-69 | 22,965 (44.0) | 10,643 (44.1) |

| 70-79 | 11,493 (22.0) | 4,719 (19.6) |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks) | ||

| None | 6,046 (11.6) | 2,113 (8.8) |

| 12 or more during lifetime | 45,918 (88.4) | 21,883 (91.2) |

| Cigarette smoking | ||

| Never smoked | 26,785 (51.9) | 10,813 (45.4) |

| Past Smoker | 21,851 (42.3) | 11,282 (47.4) |

| Current Smoker | 3,014 (5.8) | 1,709 (7.18) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.97 (5.7) | 27.54 (6.1) |

| Physical Activity (MET hrs/week) | 14.36 (14.6) | 13.75 (14.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 44,456 (85.3) | 20,666 (85.8) |

| African American | 3,771 (7.24) | 1,962 (8.2) |

| Hispanic | 1,717 (3.3) | 768 (3.2) |

| American Indian | 220 (0.4) | 87 (0.4) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1,452 (2.8) | 348 (1.5) |

| Other | 503 (1.0) | 249 (1.0) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school diploma/GED | 2,085 (4.0) | 942 (4.0) |

| High school diploma/GED | 8,115 (15.7) | 3,444 (14.4) |

| School after high school | 18,716 (36.1) | 8,910 (37.2) |

| College degree or higher | 22,938 (44.2) | 10,644 (44.5) |

| Currently married or in an intimate relationship | ||

| Yes | 40,052 (76.7) | 15,091 (62.6) |

| No | 12,155 (23.3) | 9,022 (37.4) |

| Partner Illness | ||

| Yes | 1,095 (16.4) | 627 (20.0) |

| No | 5,601 (83.7) | 2,507 (80.0) |

| Income (family) | ||

| <$20,000 | 6,133 (12.2) | 3,204 (13.8) |

| $20,000-$74,999 | 31,005 (61.8) | 14,979 (64.4) |

| >$75,000 | 11,716 (23.4) | 4,522 (19.4) |

| MHT use ever | 32,347 (61.7) | 15,293 (63.4) |

| SSRI use | 3,579 (8.1) | 2,345 (11.4) |

| Sleep medications (past 4 weeks) | ||

| Yes | 12,274 (23.6) | 6,743 (28.0) |

| No | 39,835 (76.5) | 17,320 (72.0) |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Excellent | 10,247 (19.7) | 4,292 (17.8) |

| Very good | 22,246 (42.7) | 9,476 (39.4) |

| Good | 15,439 (29.6) | 7,733 (32.1) |

| Fair | 3,782 (7.3) | 2,288 (9.5) |

| Poor | 379 (0.7) | 272 (1.1) |

| Vaginal dryness (past 4 weeks) | 14,818 (28.5) | 6,921 (28.8) |

| Hot flashes | ||

| none | 40,306 (77.4) | 18,199 (75.7) |

| mild | 8,667 (16.6) | 4,119 (17.1) |

| mod/severe | 3,112 (6.0) | 1,728 (7.8) |

| Night sweats | ||

| none | 39,751 (76.5) | 17,652 (74.6) |

| mild | 9,115 (17.5) | 4,887 (18.70) |

| mod/severe | 3,099 (6.0) | 1,858 (7.8) |

| Sexual activity in last year with a partner | 35,719 (68.4) | 10,806 (44.8) |

Data was presented as Mean± SD for continuous variables and count and percentage for categorical variables.

Hot flash/night sweat frequency self-identified as none, mild, moderate or severe during the last 4 weeks. Moderate and severe were combined.

BMI= Body Mass Index

MET = Metabolic equivalent

GED = General Educational Development

MHT = Menopausal hormone therapy

SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Compared with women who were not satisfied with their current partnered sexual activity, a higher proportion of women who reported satisfaction were married or in an intimate relationship, sexually active in the last year, were non-drinkers, more physically active, and of excellent self-rated health (all p-values <0.0001). Similarly, these women reported fewer hot flashes or night sweats and had a lower BMI (all p-values <0.0001). Women taking sleep medications or SSRI's, those who were current or past smokers, and those who had previously taken menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) were less likely to be satisfied with their current partnered sexual activity (all p-values <0.001).

Self-reported sleep characteristics are displayed in Table 2. The prevalence of insomnia was 31%. Only 19% of participants were at risk of SDB and the average baseline score was 0.85. The majority of participants (60%) reported sleep duration of 7-8 hours. Few were identified as having comorbid insomnia and sleep disordered breathing (8%).

Table 2. Self-reported sleep characteristics.

| Variable |

Baseline (%) (N = 93,668) |

|---|---|

| Insomnia* | |

| Yes | 28,546 (31.2) |

| No | 63,082 (68.9) |

| Sleep Duration | |

| 5 h or less | 7,738 (8.3) |

| 6 h | 25,076 (26.9) |

| 7 – 8 h | 56,060 (60.2) |

| 9 h or more | 4,300 (4.6) |

| Sleep Disordered Breathing (SDB) Score** | |

| High risk | 18,117 (19.4) |

| Low risk | 75,499 (80.7) |

| Comorbid insomnia and SDB score | |

| High risk | 7,099 (7.8) |

| Low risk | 84,529 (92.3) |

Insomnia is defined as a score of 9 or greater on the WHI Insomnia Rating Scale (Levine DW et al. Reliability and validity of the Women's Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess 2003; 15(2):137-48)

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) score was calculated utilizing risk factors for sleep apnea adapted from the Berlin Questionnaire. The scores ranged from 0 to 3 points and scores ≥2 were considered high risk for SBD and <2 low risk (Rissling MB, Gray KE, Ulmer C, et al. Sleep Disturbance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Veteran Women. Gerontologist. 2016.56(Suppl 1):S54-66.)

Participants with insomnia were less sexually active, less satisfied with their current sexual activity either with a partner or alone, desired sex more often, and were more worried that their sexual activity would affect their health than those without insomnia (Table 3: all p-values <0.0001).

Table 3. Self-reported Sexual Function Characteristics Stratified by Insomnia Status.

| Variable | Baseline (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Insomnia* | ||

| Yes (N= 28,546) | No (N=63,082) | |

| Sexual activity in the last year with a partner | ||

| No | 13,309 (46.8) | 27,079 (43.0) |

| Yes | 14,144 (49.7) | 35,518 (53.3) |

| Don't want to answer | 1,010 (3.6) | 2,319 (3.7) |

| Satisfaction with current sexual activity either with a partner or alone | ||

| Very satisfied | 8,218 (29.4) | 22,070 (35.7) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 6,636 (23.8) | 14,526 (23.5) |

| A little unsatisfied | 4,265 (15.3) | 8,339 (13.5) |

| Very unsatisfied | 4,045 (14.5) | 7,112 (11.5) |

| Don't want to answer | 4,755 (17.0) | 9,704 (15.7) |

| Satisfaction with the frequency of sexual activity or would like to have sex more or less often | ||

| Less often | 1,430 (5.2) | 2,059 (3.4) |

| Satisfied with current frequency | 12,019 (43.4) | 30,567 (49.8) |

| More often | 8,061 (29.1) | 16,444 (26.8) |

| Don't want to answer | 6,180 (22.3) | 12,328 (20.1) |

| Worried sexual activity will affect your health | ||

| Not at all worried | 23,606 (84.0) | 54,126 (87.1) |

| A little worried | 1,144 (4.1) | 1,991 (3.2) |

| Somewhat worried | 625 (2.2) | 1,013 (1.6) |

| Very worried | 400 (1.4) | 454 (0.7) |

| Don't want to answer | 2,316 (8.2) | 4,581 (7.4) |

Data was presented as count and percentage for categorical variables. All p-values are <0.0001.

Insomnia is defined as a score of 9 or greater on the WHI Insomnia Rating Scale (Levine DW et al. Reliability and validity of the Women's Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess 2003; 15(2):137-48)

Adjusted Associations between Sleep and Sexual Function (Table 4)

Table 4. Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Associations between Sleep and Sexual Function.

| Sexual Activity with a partner (active/inactive) N=62,011 | Model 1 ORa (95% CI) | Model 2 ORb (95% CI) | Sexual Satisfaction with a partner or alone (Yes/No) N=53,774 | Model 1 ORa (95% CI) | Model 2 ORb (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (27,740) N (%) | Yes (34,271) N (%) | No (17,007) N (%) | Yes (36,767) N (%) | |||||

| Insomnia | ||||||||

| Yes | 9,398 (34) | 10,381 (30) | 0.98 (0.92,1.03) | 0.98 (0.92,1.04) | 6072 (36) | 10872 (30) | 0.87 (0.83,0.92) | 0.92 (0.87,0.96) |

| No | 18,342 (66) | 23,890 (70) | Ref | Ref | 10935 (64) | 25895 (70) | Ref | Ref |

| Sleep duration, hours per night | ||||||||

| ≤ 5 | 2,635 (10) | 2,175 (6) | 0.83 (0.76,0.91) | 0.88 (0.80,0.96) | 1524 (9) | 2386 (7) | 0.83 (0.77,0.89) | 0.88 (0.81,0.95) |

| 6 | 7,982 (29) | 8582 (25) | 0.91 (0.86,0.96) | 0.94 (0.89,0.99) | 4775 (28) | 9314 (25) | 0.91 (0.86,0.94) | 0.94 (0.90,0.98) |

| 7-8 | 14,762 (57) | 21,939 (64) | Ref | Ref | 9893 (58) | 23288 (63) | Ref | Ref |

| ≥ 9 | 1,361 (5) | 1,575 (5) | 0.91 (0.82,1.01) | 0.90 (0.81,1.00) | 815 (5) | 1779 (5) | 0.98 (0.90,1.07) | 0.99 (0.90,1.08) |

| Sleep disordered breathing score (SDB)* | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.00 (0.97,1.04) | 1.00 (0.97,1.04) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.99 (0.97,1.02) | 1.00 (0.97,1.03) |

| Comorbid SDB and insomnia score | ||||||||

| High risk | 2602 (9) | 2446 (7) | 0.99 (0.90,1.10) | 1.00 (0.90,1.11) | 1530 (9) | 2742 (8) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 1.06 (0.97,1.15) |

| Low risk | 25138 (91) | 31825 (93) | Ref | Ref | 15477 (91) | 34025 (93) | Ref | Ref |

Adjusted for age, marital status, family income, race/ethnicity, education level, physical activity, self-rated health, antidepressant use including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use, sedative hypnotic use, sleep medication use, CES-D/DIS, hysterectomy, smoking status, weight, and alcohol use

Adjusted for covariates listed in the model 1 as well as hot flashes, night sweats, osteoporosis, physical and verbal abuse, life events scale, social strain construct, social support construct, vaginal dryness, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, stroke, cancer (breast, ovarian and cervical), diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, obesity (BMI >30) and menopausal hormone therapy.

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) score was calculated utilizing risk factors for sleep apnea adapted from the Berlin Questionnaire. The scores ranged from 0 to 3 points and scores ≥2 were considered high risk for SBD and <2 low risk (Rissling MB et al. (2015) Sleep Disturbance, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Veteran Women. Gerontologist.2016;56:S54-66..). They were included as a continuous variable in the models.

Bolded responses indicate statistically significant findings.

Lower sleep duration was associated with lower odds of partnered sexual activity. Specifically, those who slept ≤ 5 hours or 6 hours had lower odds of partnered sexual activity than those who slept 7 – 8 hours (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.76-0.91 and OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86-0.96 respectively). These relationships remained after adjustment for potential confounders (Table 4).

Similarly, lower sleep duration was associated with lower odds of sexual satisfaction in both models. Compared to those who slept 7-8 hours, the odds of sexual satisfaction were lower for those who slept ≤5 hours (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.77-0.89 and OR 0.91) or 6 hours (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86-0.94). The same relationship remained after confounder adjustment. In addition, women with insomnia had lower odds of sexual satisfaction after adjustment for all covariates than those without insomnia. Statistically significant associations between risk of SDB and comorbid SDB and insomnia with sexual satisfaction were not observed.

Secondary Analyses

The association between SDB and sexual satisfaction differed by hot flash frequency. However, when we stratified results by hot flash severity, the confidence interval in women with mild hot flashes was 0.88 – 1.00 (OR 0.94), and there were no statistically significant associations identified for women with no hot flashes, or women with moderate to severe hot flashes. Associations between sexual satisfaction and sleep parameters did not differ by age, partner illness, vasomotor symptoms or use of menopausal hormone therapy.

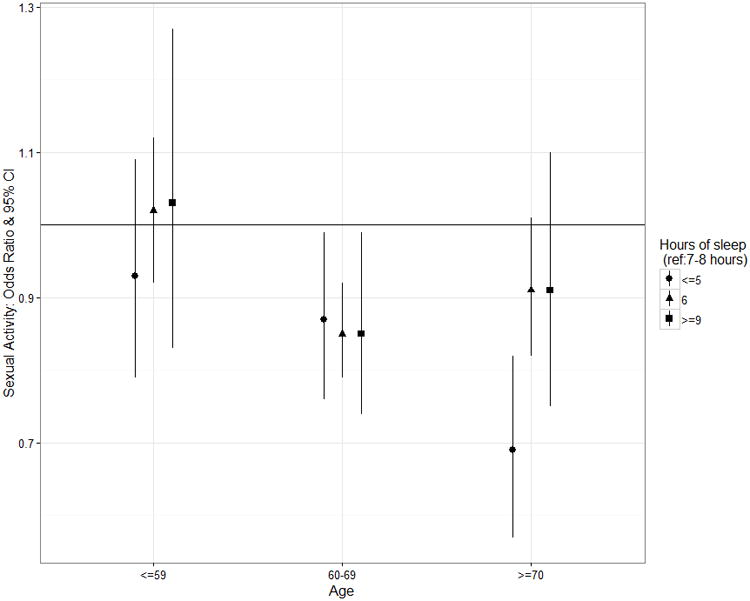

The association between partnered sexual activity and hours of sleep differed by age category and hormone therapy use. Specifically, the odds of sexual activity with less sleep were lower for older women than for younger women (Figure 1). Among women 70 years of age or older, those who slept ≤ 5 hours were less likely to be sexually active than those who slept 7-8 hours (OR = 0.69, CI 95% 0.57-0.82). A similar but less dramatic relationship was seen for younger women (age 60-69 OR = 0.87, CI 95% 0.76-0.99 and 59 years of age or younger OR = 0.93,CI 95% 0.79-1.09). The association between sleep and partnered sexual activity differed by SDB score, but once stratified by age; the relationship was no longer statistically significant for either group. Associations between sleep parameters and partnered sexual activity did not differ significantly by partner illness or vasomotor symptoms.

Figure 1.

Sexual Activity Odds Ratio for Sleep Durations (≤ 5 hours, 6 hours, ≥ 9 hours: ref category 7-8 hours) by Age Category. OR > 1 = higher odds sexual activity, OR < 1 = lower odds of sexual activity.

Stratification by menopausal hormone therapy use (never, past, current) revealed that the never (OR 0.91, CI 95% 0.82-1.00) and past users (OR 0.85, CI 95% 0.74-0.98) with insomnia had lower odds of partnered sexual activity than did those without insomnia. However, this relationship was not significant for current users (OR 1.02, CI 95% 0.94-1.11). Similarly, never users were less likely to be sexually active if they slept ≤ 5 hours (OR 0.74, CI 95% 0.64-0.85) than if they slept 7-8 hours, while the number of hours slept was not significant for past users (OR 0.83, CI 95% 0.67-1.03) or current users (OR 1.04, CI 95% 0.92-1.19).

After excluding data from women with major chronic diseases and antidepressant use (data not shown) findings were similar to the original analysis for both sexual activity and sexual satisfaction. Similarly, when we restricted analysis to women with poor self-rated health, the magnitude and direction of results were similar to those of the primary analysis, while the statistical significance was lost, possibly because of sample size reduction (62,011 to 6,064).

In the subgroup analysis restricted to women living with a partner (data not shown), the results were also similar to the original analyses. However, for women who were living without a partner, results differed from those of the main analysis. Specifically, women living without a partner who slept less than 7-8 hours were more likely to be sexually active (≤ 5 hours OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.87-1.29 and 6 hours OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03-1.31), but less like to be sexually satisfied (6 hours OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84-0.99). Whereas, those who slept nine or more hours were more likely to be sexually satisfied (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.01-1.42) when compared to those sleeping 7-8 hours.

In the main analysis, SDB was not significantly associated with sexual function. However, for women not living with a partner those with a higher SDB score had lower odds of sexual activity (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.77-0.90), but higher odds of sexual satisfaction (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05-1.16) than women with a lower SDB score.

A large proportion of responses were excluded due to missing data on one or more covariates (34 % for sexual activity and 43% for sexual satisfaction). We compared key characteristics (age, BMI, ethnicity, education, partner status, alcohol use, history of cardiovascular disease, hypertension, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer or diabetes, vasomotor symptom presence, sleep medications and SSRI use), between the women who were excluded and those included (results not shown). Overall, the distributions of characteristics were very similar between women included and excluded apart from a few variables. Of those included in the sexual satisfaction analysis, there were higher percentages that were married or in an intimate relationship (73.2 % vs. 57.3%), and more were white (87.8% vs. 77.7%) compared to those excluded. For the sexual activity analysis, more of those that were included had hypertension (36.6 vs. 27.1%), and were white (86.8% vs. 77.0%) than those that were excluded.

Discussion

In the WHI Observational Study, significant associations between sleep duration, insomnia, and sexual activity and sexual satisfaction were identified. Women who slept less than 7-8 hours per night were less likely to be sexually active and sexually satisfied. Those with insomnia were also less likely to be sexually satisfied. These relationships remained after multivariate adjustment accounted for many of the comorbidities that could have explained the relationship between sleep and sexual function, including depression and chronic diseases.

Our findings are consistent with prior literature that has demonstrated an association between less sleep and poor sexual function in other populations. Anderson and colleagues posited that sleep duration was critical to next-day sexual desire in their review of the relationships of sleep, testosterone and sexual function.9 Kalmbach and colleagues found that sleep duration in healthy college-age women was related to next-day sexual desire independent of affect and fatigue. Women reported better genital arousal with longer average sleep durations. For partnered women, an additional hour of total sleep time increased their chance of sexual activity by 14%.23 The National Sleep Foundation's consensus statement on sleep duration recommends optimal ranges of sleep duration as being necessary for overall health and functioning.27 It appears the same is true for sexual functioning.

Although insomnia is the most prevalent clinical sleep disorder in the U.S., 39 its association with sexual function has not been thoroughly examined among women. We were able to use a clinically relevant, validated insomnia scale (WHIIRS) to evaluate the associations between insomnia and sexual function. Our results demonstrated that women with insomnia were less likely to be sexually satisfied, but there was no impact on the likelihood of partnered sexual activity. Just as daytime fatigue and concentration issues can be present for those who suffer from insomnia, decreased sexual satisfaction also may represent a sequelae of the nocturnal symptoms of insomnia. Perhaps the chronic nature of insomnia means women will continue their daily activities, including sexual activity, but their perception of and satisfaction with these activities may be affected by the daytime sequelae of their insomnia.

Unlike prior studies, no significant associations were found between the sleep-disordered breathing score (those at risk of obstructive sleep apnea) and sexual activity or satisfaction. Previously, reduced sexual function has been identified for women with severe sleep apnea in a dose-related fashion as well as for women with nocturnal hypoxia.5,6,13 We speculate that sleep characteristics of women in our study were not sufficiently disturbed to cause a change to their overall sleep latency or duration to affect sexual function. Alternatively, it is possible that sleep duration, which can be affected by obstructive sleep apnea, may be the key component impacting sexual function in the prior studies.

The relationship between sleep characteristics and partnered sexual activity differed across age groups. Older women were less likely to be sexually active if they slept less than 7-8 hours per night compared to younger women, possibly related to more comorbidities. In fact, women over 70 who slept less than five hours were 30% less likely to be sexually active than women sleeping 7-8 hours. It has been shown that older age is associated with less partnered sexual activity.12,14 It is also known that the prevalence of sleep problems rise with age.40 Furthermore, poor sleep is associated with shorter sleep durations.41 An improved understanding of sleep disturbance could positively impact sexual activity in older women.

Menopausal hormone therapy has been shown to attenuate the negative effects of menopausal symptoms on sleep.42 Our results are in line with these findings. No significant relationship was found between partnered sexual activity and insomnia for current menopausal hormone therapy users, whereas never or past users with insomnia had lower odds of engagement in sexual activity. Similarly, the relationship between sexual activity and sleep duration was not significant for current menopausal hormone therapy users, but among women who had never used MHT, shorter sleep duration was associated with decreased odds of partnered sexual activity.

Past studies have demonstrated that relationship factors, including the availability of sexual partners and change in relationship status, impact sexual function.36-38 Presence of a partner may be protective against sexual dissatisfaction. In our cohort, an interesting relationship between sleep and sexual functioning was identified for women who did not live with a partner. For these women, less sleep was associated with increased odds of sexual activity, but decreased odds of sexual satisfaction. Although the cause of this relationship is unclear, it may indicate different lifestyle factors for women not living with a partner that influences sexual function. It is important to note that sexual satisfaction was not exclusive to having a partner.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large sample size, and the design of the WHI that included carefully assessed variables with comprehensive information at baseline. Insomnia was evaluated using a validated, clinically relevant scale (WHIIRS) that can be used in outpatient health care settings. To our knowledge, our sample size is significantly larger than previous studies examining the relationship between sleep and sexual function in postmenopausal women.

Limitations of this research include that a large proportion (34 % for sexual activity and 43% for sexual satisfaction) of women were excluded in the multivariate analysis due to missing data on one or more of the covariates. However, the number of participants remained high (62,011 for sexual activity, 53,774 for sexual satisfaction) allowing us to evaluate these relationships in a large cohort. Comparison of those included vs. excluded showed a higher percentage of white participants included for both sexual health outcomes, and higher percentages of those with hypertension for sexual activity, and higher proportions married or in an intimate relationship for the sexual satisfaction outcome. Additionally, a majority of outcome variables were based upon self-report data, perhaps introducing the potential for misclassification of participants, particularly with regard to sleep characteristics (i.e., snoring) that commonly go undetected in women living without partners. Only a small number of sexual function questions were asked in the WHI, limiting our ability to further explore sexual function characteristics in this population. Furthermore, the sexual satisfaction construct is not validated, although it uses wording similar to other validated instruments. We adjusted for a number of potentially important confounders; however, residual confounding due to unmeasured confounders could have affected our association estimates. Many comorbidities such as general health, medications, chronic disease, emotional and psychological issues, affect both sleep and sexual function, which could lead to reverse causation bias in our results. Lastly, given the cross-sectional design of this study, directionality of the relationships identified cannot be identified. Next steps will include evaluating these relationships over time.

Conclusion

Our results indicate associations between shorter sleep durations, higher insomnia symptoms and decreased sexual function, which remained after adjustment for multiple possible confounders. These findings suggest the potential importance of obtaining high quality and sufficient sleep. Older age and lack of current hormone use were associated with less reported sexual activity when sleep durations were lower than 7-8 hours. Prospective, longitudinal investigation of sleep and its impact on sexual function after menopause would help clarify these relationships.

Acknowledgments

Funding: “The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C.” Funding from the Department of Internal Medicine at Mayo Clinic Arizona contributed to statistical support, but no other funds were utilized for this project.

Footnotes

Financial support statement: The authors have no conflict of interest or financial disclosures.

Short List of Whi Investigators: Program Office: (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Maryland) Jacques Rossouw, Shari Ludlam, Dale Burwen, Joan McGowan, Leslie Ford, and Nancy Geller

Clinical Coordinating Center: Clinical Coordinating Center: (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA) Garnet Anderson, Ross Prentice, Andrea LaCroix, and Charles Kooperberg

Investigators and Academic Centers: (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) JoAnn E. Manson; (MedStar Health Research Institute/Howard University, Washington, DC) Barbara V. Howard; (Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford, CA) Marcia L. Stefanick; (The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH) Rebecca Jackson; (University of Arizona, Tucson/Phoenix, AZ) Cynthia A. Thomson; (University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY) Jean Wactawski-Wende; (University of Florida, Gainesville/Jacksonville, FL) Marian Limacher; (University of Iowa, Iowa City/Davenport, IA) Robert Wallace; (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) Lewis Kuller; (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker

Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC) Sally Shumaker

References

- 1.Wheaton AG, Perry GS, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Sleep disordered breathing and depression among U.S. adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005 – 2008. Sleep. 2012;35(4):461. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogtmann E, Levitan EB, Hale L, Shikany JM, Shah NA, Endeshaw Y, Lewis CE, Manson JE, Chlebowski RT. Association between Sleep and Breast Cancer Incidence among Postmenopausal Women in the Women's Health Initiative. Sleep. 2013;36(10):1437–1444. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dennerstin L, Guthrie JR, Hayes RD, DeRogatis LR, Lehert P. Sexual function, dysfunction, and sexual distress in a prospective, population-based sample of mid-aged, Australian-born women. J Sex Med. 2008;5(10):2291–2299. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stavaras C, Pastaka C, Papala M, et al. Sexual Function in pre and post-menopausal women with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2012;24:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanfulla F, Camera A, Fulgoni P, Chiovato L, Nappi RE. Sexual dysfunction in obese women: Does obstructive sleep apnea play a role? Sleep Medicine. 2013;14:252–256. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian S, Bopparaju S, Desai A, Wiggins T, Rambaud C, Surani S. Sexual dysfunction in women with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2010;14(1):59–62. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Have TT, Rein J, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Prevalence of Sleep-disordered Breathing in Women: Effects of Gender. Am J Repir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:608–613. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.9911064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersen ML, Alvarenga TF, Mazaro-Costa R, Hachul HC, Tufik S. Brain Research. 2011. The association of testosterone, sleep and sexual function in men and women; pp. 80–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Zambotti M, Colrain IM, Javitz HS, Baker FC. Magnitude of the impact of hot flashes on sleep in perimenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(6):1708–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muicheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A Study of Sexuality and Health among Older Adults in the United States. NEJM. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kripke DF, Brunner R, Freeman R, Hendrix SL, Jackson RD, Masaki K, Carter RA. Sleep Complaints of Postmenopausal Women. Clin J Womens Health. 2001;1(5):244–252. doi: 10.1053/cjwh.2001.30491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gass M, Cochrane B, Larson J, et al. Patterns and Predictors of Sexual Activity Among Women in the Women in the Hormone Therapy Trials of the Women's Health Initiative. Menopause. 2011;18(11):1160–1171. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182227ebd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barclay NL, Eley TC, Rijsdijk FV, Gregory AM. Dependent negative life events and sleep quality: An examination of gene-environment interplay. Sleep Medicine. 12(4):403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodenmann G, Ledermann T, Blattner D, Galluzzo C. Associations Among Everyday Stress, Critical Life Events and Sexual Problems. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:494–501. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228504.15569.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shumaker SA, Hill DR. Gender differences in social support and physical health. Health Psychol. 1001;10(2):102–11. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Troxel WM, Buysse DJ, Monk TH, Begley A, Hall M. Does social support differentially affect sleep in older adults with versus without insomnia? J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(5):459–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vegunta S, Kuhle C, Kling JM, et al. The association between recent abuse and menopausal symptom bother: results from the Data Registry on Experiences of Aging, Menopause and Sexuality (DREAMS) Menopause. 2016;23(5):494–8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prairie BA, Wisniewski SR, Luther J, et al. Symptoms of Depressed Mood, Disturbed Sleep, and Sexual Problems in Midlife Women: Cross-Sectional Data from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Journal of Womens Health. 2015;24:119–126. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed SD, Newton K, LaCroix AZ, Grothaus LC, Ehrlich K. Night sweats, sleep disturbance, and depression associated with diminished libido in late menopausal transition and early postmenopause: baseline data from the Herbal Alternatives for Menopause Trial (HALT) American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;593:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eraslan D, Ertekin E, Ertekin BA, Ozturk O. Treatment of Insomnia with Hypnotics Resulting in Improved Sexual Functioning in Post-Menopausal Women. Pychiatria Danubina. 2014;26(4):353–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalmbach DA, Arnedt JT, Pillai V, Ciesla JA. The Impact of Sleep on Female Sexual Response and Behavior: A Pilot Study. J Sex Med. 2015;12:1221–1232. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. The Women's Health Initiative Study Group. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rissling MB, Gray KE, Ulmer C, et al. Sleep Disturbance Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease in Post-Menopausal Veteran Women. Gerontologist. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S54–66. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swinkels CM, Ulmer CS, Beckham JC, Buse N, Calhoun PS. The Association of Sleep Duration, Mental Health, and Health Risk Behaviors among U.S. Afghanistan/Iraq Era Veterans. Sleep. 2013;36(7):1019–1025. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundations' sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Levine DW, Kripke DF, Kaplan RM, et al. Realiability and validity of the Women's Health Initiative Insomnia Rating Scale. Psychol Assess. 2003;15(2):137–48. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(7):485–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustafa M, Erokwu N, Ebose I, Strohl K. Sleep problems and the risk for sleep disorders in an outpatient veteran population. Sleep Breath. 2005;9(2):57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robins L, Helzer J, Croughan J, Ratcliff K. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ruberman W, Weinglatt E, Goldberg JD, Chaudhary BS. Psychosocial influences on mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(9):552–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408303110902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Birditt K, Antonucci TC. Life sustaining irritations? Relationship quality and mortality in the context of chronic illness. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(8):1291–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Jaramillo SA, Legault C, et al. Correlates of Sexual Satisfaction Among Sexually Active Postmenopausal Women in the Women's Health Initiative-Observational Study. JGIM. 2008;23(12):2000–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0820-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: Results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16:442–452. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Burger H. The relative effects of hormones and relationship factors on sexual function of women through the natural menopausal transition. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:174–180. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: Prevalance, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M. Sleep and aging: 1. Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. CMAJ. 2007;176(9) doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohayon MM. Determing the level of sleepiness in the American population and its correlates. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kravitz HM, Joffe H. Sleep during the perimenopause: A SWAN story. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:567–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]