Abstract

Although loss of control while eating (LOC) is a core construct of bulimia nervosa (BN), questions remain regarding its validity and prognostic significance independent of overeating. We examined trajectories of objective and subjective binge eating (OBE and SBE, respectively; i.e., LOC eating episodes involving an objectively or subjectively large amount of food) among adults participating in psychological treatments for BN-spectrum disorders (n=80). We also explored whether changes in the frequency of these eating episodes differentially predicted changes in eating-related and general psychopathology and, conversely, whether changes in eating-related and general psychopathology predicted differential changes in the frequency of these eating episodes. Linear mixed models with repeated measures revealed that OBE decreased twice as rapidly as SBE throughout treatment and 4-month follow-up. Generalized linear models revealed that baseline to end-of-treatment reductions in SBE frequency predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up changes in eating-related psychopathology, depression, and anxiety, while changes in OBE frequency were not predictive of psychopathology at 4-month follow-up. Zero-inflation models indicated that baseline to end-of-treatment changes in eating-related psychopathology and depression symptoms predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up changes in OBE frequency, while changes in anxiety and self-esteem did not. Baseline to end-of-treatment changes in eating-related psychopathology, self-esteem, and anxiety predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up changes in SBE frequency, while baseline to end-of-treatment changes in depression did not. Based on these findings, LOC accompanied by objective overeating may reflect distress at having consumed an objectively large amount of food, whereas LOC accompanied by subjective overeating may reflect more generalized distress related to one’s eating- and mood-related psychopathology. BN treatments should comprehensively target LOC eating and related psychopathology, particularly in the context of subjectively large episodes, to improve global outcomes.

Keywords: bulimia nervosa, loss of control eating, binge eating, validity, psychopathology

Bulimia nervosa (BN), characterized by recurrent binge eating and compensatory behaviors, is associated with significant physical and psychosocial health impairments (Fairburn & Harrison, 2003). Binge eating is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) as the consumption of an objectively large amount of food accompanied by a subjective sense of loss of control over what or how much one is eating (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, in line with significant variability in the size of binge eating episodes among individuals with BN (Mitchell, Crow, Peterson, Wonderlich, & Crosby, 1998), researchers and diagnosticians have distinguished between objective binge eating episodes (i.e., those that are deemed unusually large by a clinical rater, given the context) and subjective binge eating episodes (i.e., those that are deemed excessive by the respondent, but are not unusually large according to clinical rating standards; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). It has been argued that loss of control is the core feature accounting for distress and impairment in BN and other disorders involving recurrent binge eating (e.g., binge eating disorder; BED), whereas binge size is better characterized as a marker of excess weight status or as a risk factor for weight gain (Wolfe, Baker, Smith, & Kelly-Weeder, 2009). Yet, it has been difficult to parse out the role of loss of control in objective binge eating because perceptions of loss of control may be confounded by episode size (i.e., loss of control may reflect momentary emotional distress at having consumed an objectively large amount of food; Pollert et al., 2013). Moreover, loss of control has been difficult to operationalize due to inter- and intra-individual differences in the quantity and quality of loss of control eating episodes, as well as unreliable measurement (e.g., poor inter-rater and temporal reliability, particularly for subjective binge eating; Mond, 2013). Given these issues, a number of questions remain regarding the validity and specificity of the loss of control construct (Latner & Clyne, 2008).

Despite the apparent link between loss of control and eating-related and general psychopathology in BN independent of the quantity of food consumed (Keel, Mayer, & Harnden-Fischer, 2001; Pratt, Niego, & Agras, 1998), subjective binge eating episodes are rarely reported as a measure of treatment outcome in clinical trials for BN (Castellini et al., 2012; Steele & Wade, 2008). Importantly, it is unknown how objectively versus subjectively large loss of control eating episodes are uniquely associated with treatment outcome as approximated by measures of eating-related and general psychopathology. Clarifying this issue could have significant implications for the nosology of eating disorders as well as the development of novel treatments for these disorders. Studies that have examined the prognostic value of subjective binge eating episodes have found that these types of eating episodes predict lower rates of remission from BN and BED (Castellini et al., 2012), and that they are less responsive to treatments for BN (Walsh, Fairburn, Mickley, Sysko, & Parides, 2004), as compared to objective binge episodes. Moreover, several studies of BN and BED have shown that decreases in objective binge eating are often accompanied by slower decreases, or even increases, in subjective binge eating (Hildebrandt & Latner, 2006; Niego, Pratt, & Agras, 1997; Peterson et al., 2000). Relatedly, although eating-related and general psychopathology generally decrease during treatment for BN (Hay, Bacaltchuk, Stefano, & Kashyap, 2009), it is unknown whether reductions in binge size (i.e., from objectively to subjectively large) or in loss of control differentially account for these improvements.

The relatively more rapid reduction in objective compared to subjective binge eating may result from the introduction of strategies to normalize eating behavior early in treatment, while persistent or worsening subjective binge eating may reflect continued distress and dysfunctional beliefs about eating that are not sufficiently addressed until later in treatment (Niego et al., 1997). Alternatively, continued loss of control while eating subjectively large amounts of food may reflect a persistent temperamental disposition to label otherwise normative eating episodes as pathological. For example, underlying personality traits such as neuroticism/negative emotionality, which represents one’s proclivity towards negative affect (Watson & Naragon-Gainey, 2014), may manifest in over-endorsement of psychological symptoms (Watson & Pennebaker, 1989). This may include a tendency to perceive a loss of control during episodes involving a not-large amount of food in which one ate a greater quantity than planned or broke another type of dietary rule. Despite a strong literature supporting the association between state/trait negative affect and loss of control eating (Wolfe et al., 2009), previous studies have not accounted for constructs like neuroticism/negative emotionality in their analyses. Research investigating differential associations between changes in objective and subjective binge eating, and changes in measures of distress and impairment, adjusting for the effects of concomitant neuroticism/negative emotionality, is needed to clarify these questions.

This study aimed to address important yet unanswered questions about the prognostic significance and specificity of loss of control relative to episode size in understanding the psychopathology of eating disorders, with potential implications for nosology and treatment. Specifically, the goals of the study were to 1) replicate existing research on trajectories of loss of control eating episodes by examining patterns of change in objective and subjective binge eating over the course of a psychological treatment trial for partial- and full-syndrome BN; and 2) extend the previous literature by examining the extent to which changes in the frequency of these distinct yet related eating episodes during treatment differentially predict changes in eating-related and general psychopathology at 4-month follow-up. We expected subjective binge eating episodes to decrease more slowly than objective binge eating episodes over the course of treatment and 4-month follow-up (Hypothesis #1). We further expected that changes in both objective and subjective binge eating episode frequency from baseline to end-of-treatment would predict changes in psychopathology at 4-month follow-up, but that subjective binge eating episode frequency would be the stronger predictor of the two (Hypothesis #2). These expectations convey our overarching hypothesis that loss of control in the absence of objective overeating reflects stable, generalized distress and impairments in appraisals of eating behavior. Conversely, the combination of loss of control and objective overeating purportedly reflects specific distress about particular eating episodes in which an excessive amount of food is consumed.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 80 adults participating in a multi-site (Fargo, ND, and Minneapolis, MN) randomized controlled trial of integrative cognitive affective therapy for bulimic symptoms (ICAT-BN) compared to enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for BN (Wonderlich et al., 2014). Participants met criteria for DSM-IV or DSM-5 BN (i.e., objective binge eating and compensatory behaviors at least once a week for the past three months, accompanied by overvaluation of shape and weight; n=58; American Psychiatric Association, 2000; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) or partial BN (i.e., combined frequency of objective and/or subjective binge eating and compensatory behaviors occurring at least once a week for the past three months; n=22). Most participants (n=41) reported a combination of objective and subjective binge eating, with the remainder reporting objective binge eating only (n=29) or subjective binge eating only (n=10). Participants reported an average of 22.8 (S.D.=20.2) objective binge eating episodes and 12.7 (S.D.=16.3) subjective binge eating episodes over the 28 days preceding their initial evaluation. Very few participants reported objective overeating without loss of control in the 28 days preceding their evaluation (n=2), or any of the post-treatment time-points (n=4 at end-of-treatment, and n=2 at 4-month follow-up). All participants reported recurrent compensatory behaviors, irrespective of objective and/or subjective binge eating. The sample was predominantly female (90%; n=72) and White (87.5%; n=70), with a mean age of 27.3 (S.D.=9.6) and a mean baseline body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) of 23.9 (S.D.=5.5), which was fairly stable during treatment and thereafter (M BMI at end-of-treatment=24.6; S.D.=5.8; M BMI at 4-month follow-up=24.3; S.D.=5.4). Exclusion criteria included current pregnancy or lactation, BMI<18, lifetime bipolar or psychotic disorder, current substance use disorder, medical or psychiatric instability requiring inpatient treatment (e.g., hypokalemia or acute risk of suicide), current psychotherapy (e.g., individual psychotherapy, or couples/family therapy focused on the participant’s eating-related or psychiatric symptoms), and initiation of or change in psychotropic medication within the six weeks prior to enrollment. Detailed information on the sample, including participant flow and treatment attendance, is described by Wonderlich et al. (2014).Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The institutional review boards at each site approved this study.

Treatments

ICAT is an innovative new treatment based on the premise that BN behaviors function to regulate momentary affective states (Wonderlich, Peterson, & Smith, 2015). Interventions focus on identifying and managing momentary antecedents of negative affect associated with bulimic symptoms, and normalizing eating patterns with meal planning (Wonderlich et al., 2014). CBT-E is a well-established but recently updated treatment that utilizes psychoeducation, self-monitoring, and behavioral exposure to normalize eating patterns and modify negative self-evaluation related to shape, weight, and control over eating (Fairburn, 2008a). Both treatments targeted self-reported binge eating (i.e., eating episodes that participants perceived as binge eating episodes, irrespective of DSM-5 definitions of overeating and loss of control) as well as compensatory behaviors including self-induced vomiting. Four psychologists (two per site) delivered both treatments in 21 50-min sessions over 17 weeks.

Measures

Participants were assessed at baseline (week 0), end-of-treatment (week 17), and 4-month follow-up (week 29). The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; Fairburn, 2008a) was conducted by experienced, trained, master’s and doctoral-level assessors to assess BN criteria (including objective and subjective binge episode frequency, which for the current analyses covered the 28 days prior to assessment) and generate an index of overall eating-related psychopathology (EDE global score) via its four subscales (dietary restraint, eating concerns, shape concerns, and weight concerns; range=0–6). The EDE has excellent psychometric properties (Berg, Peterson, Frazier, & Crow, 2012) and showed good inter-rater reliability in the current study, based on a random selection of 20% of baseline EDE interviews (intra-class correlation range for EDE subscales=0.91–0.99). Objective overeating (“eating what most people would consider an unusually large amount of food”) and loss of control (“feeling like you just could not stop eating, even if you wanted to”) were determined using the EDE guidelines, and ambiguous eating episodes were coded conservatively according to clinical consensus among interviewers.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961), State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, 1973), and Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (RSE; Rosenberg, 1986) were used as self-report measures of general psychopathology. The BDI is a 21-item measure of psychological and somatic symptoms of depression over the past 2 weeks. The BDI has good reliability and validity (Beck, Steer, & Carbin, 1988; current study α=.93). Scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating greater depression symptoms. The STAI is 2-part questionnaire comprised of 40 total items measuring anxious tendencies at both the state and trait level; only trait-level anxiety was examined in the current study. Scores range from 20 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater anxious tendencies. The STAI has excellent psychometric properties (Spielberger, 1989; current study α=.96). The RSE is a 10-item scale assessing positive and negative attitudes towards the self. Scores range from 0–30, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. The RSE has established reliability and validity (Sinclair et al., 2010; current study α=.93).

The anxiousness subscale of the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire (DAPP-BQ; Livesley & Jackson, 2009) was used as a proxy for neuroticism/negative emotionality, given that it is the most highly correlated with other measures of neuroticism/negative temperament (published r range=.63–.77) of all the DAPP-BQ subscales. The anxiousness subscale includes 16 items (e.g., frequent feelings of worry/tension, tendencies towards rumination, pervasive sense of guilt) rated on a 5-point scale (score range=16–80), with higher scores indicating greater anxiousness. The DAPP-BQ has good reliability and validity (Bagge & Trull, 2003; Maruta, Yamate, Iimori, Kato, & Livesley, 2006; Pukrop et al., 2009; current study α=.94).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in SPSS version 22.0, and included treatment assignment (ICAT vs. CBT-E), baseline neuroticism/negative emotionality, and baseline compensatory behavior frequency as covariates. Analyses additionally adjusted for baseline loss of control eating status [i.e., participants who reported subjective binge eating only versus objective binge eating only or any other combination of objective/subjective binge eating on the EDE] in order to account for the fact that greater changes in subjective binge eating would be expected among those reporting only subjective binge episodes, and to account for potential individual differences related to eating episode type. We were unable to compare individuals with subjective binge eating only, objective binge eating only, and both objective/subjective binge eating on baseline characteristics due to small cell sizes. Treatment groups were not analyzed separately due to insufficient power, and data from both groups were instead pooled since the treatments did not significantly differ from one another in terms of subjective and objective binge eating outcomes at end-of-treatment and 4-month follow-up (Wonderlich et al., 2014). Analyses included all available data, including data from participants who terminated treatment prematurely but completed some or all of the assessments, and from participants who completed only some of the assessments. Missing data were not imputed.

Hypothesis #1

The first set of analyses, designed to test the hypothesis that subjective binge eating episodes would decrease more slowly than objective binge eating episodes over the course of treatment and 4-month follow-up, utilized linear mixed models with repeated measures to characterize the trajectories of eating episodes from baseline through 4-month follow-up.

Hypothesis #2

Next, to test the hypothesis that changes in both objective and subjective binge eating episode frequency would predict changes in psychopathology at 4-month follow-up, but that subjective binge eating episode frequency would be the stronger predictor of the two, four sets of generalized linear models assessed the impact of baseline to end-of-treatment changes in objective and subjective binge frequency (entered simultaneously) on the dependent variables of eating-related psychopathology, depression symptoms, anxiety, and self-esteem at 4-month follow-up. These analyses adjusted for the baseline value of the respective dependent variable, which allowed us to predict changes in psychopathology from baseline to 4-month follow-up. The baseline to 4-month follow-up timeframe was chosen to allow for exploration of long-term treatment effects; while investigating the end-of-treatment to 4-month follow-up timeframe would have allowed for the establishment of temporal precedence in the associations between the independent and dependent variables, this latter timeframe instead would have addressed questions about treatment maintenance effects.

To further test our second hypothesis by establishing whether changes in eating episodes from baseline to end-of-treatment predicted changes in psychopathology, and not the inverse, two additional analyses were conducted to examine the associations between baseline to end-of-treatment changes in eating-related and general psychopathology (entered simultaneously) and the dependent variables of objective and subjective binge frequency at 4-month follow-up, controlling for the baseline value of the respective dependent eating episode variable. These latter analyses utilized zero-inflation poisson count (reflecting the prediction of number of eating episodes) and logit models (reflecting the prediction of occurrence or non-occurrence of eating episodes) to account for the high rates of remission of objective (50% remission) and subjective binge eating (62% remission) at 4-month follow-up. Pearson correlations among the independent variables in the model ranged from −.58 to .28, thus falling under the cutoff of r=.60 among predictor variables that has been recommended to indicate the presence of strong multi-collinearity (Yoo et al., 2014).

Of note, EDE global, rather than individual EDE subscales, was utilized as a measure of eating-related psychopathology in all analyses in order to avoid inflation of Type I error and because we did not have a priori hypotheses about specific subscales. All generalized linear models assumed a negative binomial distribution because the frequency of objective and subjective binge eating was a count variable which was highly positively skewed at 4-month follow-up.

Results

Trajectories of objective and subjective binge eating

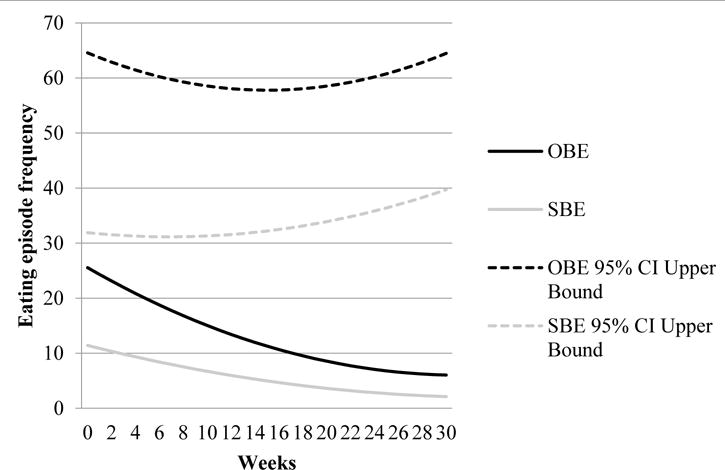

The frequency of both objective and subjective binge eating episodes significantly decreased from baseline to 4-month follow-up (Hypothesis #1; see Figure 1). Subjective binge episode frequency decreased linearly across time, B=−.055; S.E.=0.17; p=.001, with a non-significant quadratic component, B=0.01; S.E.=0.00; p=.050. Objective binge episodes, B=−1.25; S.E.=0.17; p<.001, decreased more quickly than subjective binge episodes, and these decreases were attenuated during the latter phase of the study, B=0.02; S.E.=0.00; p<.001.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of objective and subjective binge eating episodes

Note: OBE=objective binge eating; SBE=subjective binge eating; CI=confidence interval. Objective and subjective binge eating episodes were assessed at baseline (week 0), end-of-treatment (week 17), and 4-month follow-up (week 29); biweekly anchors are provided for ease of interpretation only.

Do Changes in Objective and Subjective Binge Eating Frequency Predict Changes in Psychopathology?

Models examining associations between baseline to end-of-treatment changes in objective and subjective binge eating frequency and baseline to 4-month follow-up changes in psychopathology variables (Hypothesis #2) were significant for eating-related psychopathology, depression symptoms, and anxiety, all ps<.05 (see Table 1), but not for self-esteem, p=.263. More specifically, baseline to end-of-treatment decreases in subjective binge eating frequency significantly predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up improvements in eating-related psychopathology, depression symptoms, and anxiety, all ps<.01. Changes in objective binge eating frequency did not significantly predict changes on any measure of psychopathology, all ps ≥.143. Of note, neuroticism/negative emotionality contributed significantly only to the model predicting improvements in depression symptoms, p=.034, and the association was negative.

Table 1.

Prediction of eating-related and general psychopathology at 4-month follow-up based on changes in objective and subjective binge eating frequency from baseline to end-of-treatment

| Parameter | χ2 value | B (S.E.) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: EDE eating-related psychopathology | 16.24 | — | — | .023 | .24 |

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | 0.41 | 0.17 (0.27) | −0.35 to 0.70 | .524 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | 0.12 | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.04 to 0.03 | .730 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 1.10 | −0.46 (0.44) | −1.32 to 0.40 | .295 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00) | −0.01 to 0.01 | .966 | |

| Baseline EDE eating-related psychopathology | 9.22 | 0.42 (0.14) | 0.15 to 0.70 | .002 | |

| Change in objective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.16 | 0.00 (0.01) | −0.01 to 0.02 | .690 | |

| Change in subjective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 9.36 | 0.03 (0.01) | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.002 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 2: BDI depression symptoms | 27.50 | — | — | <.001 | .18 |

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | 2.64 | −4.27 (2.63) | −9.43 to 0.89 | .105 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | 4.48 | −0.41 (0.19) | −0.79 to −0.03 | .034 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 0.11 | −1.51 (4.63) | −10.58 to 7.57 | .745 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | 0.10 | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.10 to 0.07 | .753 | |

| Baseline BDI depression symptoms | 18.12 | 0.69 (0.16) | 0.37 to 1.00 | <.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Change in objective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.12 | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.12 to 0.17 | 0.725 | |

| Change in subjective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 9.05 | 0.24 (0.08) | 0.08 to 0.39 | 0.003 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 3: STAI anxiety symptoms | 27.64 | — | — | <.001 | .19 |

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | 0.77 | −2.80 (3.18) | −9.03 to 3.44 | .379 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | 3.34 | −0.59 (0.32) | −1.22 to 0.04 | .068 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 0.55 | −3.91 (5.28) | −14.27 to 6.45 | .459 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | 0.48 | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.06 to 0.13 | .490 | |

| Baseline STAI anxiety | 11.81 | 0.79 (0.23) | 0.34 to 1.24 | .001 | |

| Change in objective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 2.14 | 0.12 (0.08) | −0.04 to 0.28 | .143 | |

| Change in subjective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 15.04 | 0.37 (0.09) | 0.18 to 0.55 | <.001 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 4: RSE self-esteem | 13.56 | — | — | .060 | .17 |

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | 1.67 | 0.62 (0.48) | −0.32 to 1.57 | .196 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | 0.38 | 0.02 (0.03) | −0.04 to 0.08 | .536 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 0.06 | 0.20 (0.85) | −1.47 to 1.87 | .814 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | 0.01 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.02 to 0.01 | 0.926 | |

| Baseline RSE self-esteem | 8.58 | 0.49 (0.17) | 0.16 to 0.82 | .003 | |

| Change in objective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.02 | −0.00 (0.01) | −0.03 to 0.02 | .885 | |

| Change in subjective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment | 1.25 | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.05 to 0.01 | .263 | |

Note: EDE=Eating Disorder Examination; DAPP-BQ=Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; STAI=State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; RSE=Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. Pseudo R2 is a measure of effect size for mixed models that reflects the proportion of variance accounted for by the model. Significant parameter estimates are highlighted in bold font.

Do Changes in Psychopathology Predict Changes in Objective and Subjective Binge Eating Frequency?

Models examining associations between baseline to end-of-treatment changes in psychopathology and baseline to 4-month follow-up changes in objective and subjective binge eating frequency (confirmation of Hypothesis #2) are described in Table 2. In short, baseline to end-of-treatment improvements in eating-related psychopathology, count model coefficient estimate=0.47; p<.001, and depression symptoms, estimate=0.02; p=.039, significantly predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up decreases in objective binge eating episode frequency. Changes in anxiety and self-esteem did not significantly predict changes in objective binge eating frequency, ps≥.235. Baseline to end-of-treatment improvements in eating-related psychopathology, estimate=0.58; p<.001, self-esteem, estimate=0.14; p=.023, and anxiety, estimate=0.05; p<.001, significantly predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up decreases in subjective binge eating frequency, while baseline to end-of-treatment changes in depression symptoms did not, p=.126.

Table 2.

Prediction of objective and subjective binge eating frequency at 4-month follow-up based on changes in eating-related and general psychopathology from baseline to end-of-treatment

| Parameter | Count model coefficient (S.E.) | p-value | Zero-inflation model coefficient (S.E.) | p-value | Pseudo R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Objective binge eating | .62 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | −1.09 (0.15) | <.001 | −0.26 (0.70) | .705 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | −0.04 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.06 (0.04) | .206 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 1.78 (0.59) | .002 | 1.23 (1.36) | .364 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | 0.02 (0.00) | <.001 | 0.00 (0.02) | .856 | |

| Baseline objective binge eating | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.005 | −0.04 (0.03) | .092 | |

| Change in EDE eating-related psychopathology from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.47 (0.09) | <.001 | −0.32 (0.38) | .390 | |

| Change in BDI depression symptoms from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.02 (0.01) | .039 | −0.08 (0.05) | .092 | |

| Change in STAI anxiety from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.01 (0.01) | .235 | −0.02 (0.04) | .691 | |

| Change in RSE self-esteem from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.06 (0.07) | .444 | −0.31 (0.26) | .247 | |

|

| |||||

| Model 2: Subjective binge eating | .36 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Treatment assignment | −1.08 (0.24) | <.001 | 1.32 (0.83) | .112 | |

| Baseline DAPP-BQ anxiousness | 0.05 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.03 (0.05) | .499 | |

| Baseline loss of control eating status | 0.71 (0.48) | .141 | 1.33 (1.39) | .340 | |

| Baseline compensatory behavior frequency | −0.01 (0.00) | .038 | 0.02 (0.02) | .253 | |

| Baseline subjective binge eating | −0.03 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.05 (0.03) | .152 | |

| Change in EDE eating-related psychopathology from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.58 (0.11) | <.001 | −0.60 (0.43) | .158 | |

| Change in BDI depression symptoms from baseline to end-of-treatment | −0.01 (0.01) | .126 | −0.04 (0.05) | .436 | |

| Change in STAI anxiety from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.05 (0.01) | <.001 | −0.05 (0.04) | .205 | |

| Change in RSE self-esteem from baseline to end-of-treatment | 0.14 (0.06) | .023 | −0.11 (0.26) | .680 | |

Note: DAPP-BQ=Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire; EDE=Eating Disorder Examination; BDI=Beck Depression Inventory; STAI=State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; RSE=Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. Count model coefficients reflect the prediction of number of eating episodes, and zero-inflation model coefficients reflect the prediction of occurrence or non-occurrence of eating episodes. Pseudo R2 is a measure of effect size for mixed models that reflects the proportion of variance accounted for by the model. Significant parameter estimates are highlighted in bold font.

Discussion

The current study aimed to characterize objective and subjective binge eating episode trajectories during a psychological treatment trial for BN, and the impact of changes in these distinct but related eating episodes on changes in eating-related and general psychopathology. Objective binge eating decreased twice as rapidly as subjective binge eating (although, of note, objective binge episodes also occurred more frequently at baseline than subjective binge episodes). Our findings further revealed that reductions in subjective binge eating from baseline to end-of-treatment predicted reductions in eating-related and general psychopathology from baseline to 4-month follow-up. However, changes in objective binge eating had no impact on changes in psychopathology. Finally, baseline to end-of-treatment reductions in eating-related and depressive psychopathology (but not anxiety and self-esteem) predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up reductions in objective binge eating frequency; baseline to end-of-treatment reductions in eating-related psychopathology, self-esteem, and anxiety (but not depression) predicted baseline to 4-month follow-up reductions in subjective binge eating frequency.

Both treatments were associated with relatively rapid reductions in objective binge eating, as might be expected given their focus on normalizing eating patterns. However, consistent with previous studies (Hildebrandt & Latner, 2006; Niego et al., 1997; Peterson et al., 2000), relatively slower reductions in subjective binge eating suggest that subjective binge eating may be less responsive to treatment than objective binge eating, perhaps because current treatment targets do not sufficiently address loss of control in the absence of objectively large amounts of food. Taken together, comprehensively targeting all loss of control eating regardless of episode size (along with related psychopathology) may help improve global outcomes for individuals with BN-spectrum disorders. This may include a concomitant focus on identifying antecedents of subjective binge eating episodes early in treatment, and correcting misperceptions about what constitutes an excessive amount of food (which may be related to subjective feelings of loss of control; Pollert et al., 2013), although further research is needed to understand if there are distinct triggers to objective and subjective binge eating episodes that could be addressed in treatment to achieve these ends.

Findings indicating that changes in subjective binge eating frequency predicted changes in psychopathology, while changes in objective binge eating frequency did not, may suggest that loss of control accompanied by objectively large amounts of food may reflect circumscribed distress at having consumed an objectively large amount of food rather than generalized psychopathology (Pollert et al., 2013), whereas loss of control accompanied by subjectively large amounts of food reflects more generalized distress related to one’s eating- and mood-related psychopathology. Importantly, these results were not accounted for by a trait-like proxy for neuroticism/negative emotionality or other individual differences related to the presence or absence of subjective binge eating, indicating that subjective binge eating is not merely a manifestation of one’s tendency to pathologize one’s experiences and behaviors, and that results are not better accounted for by baseline differences between those who report subjective binge episodes versus those who do not.

In addition to the implications for treatment, our findings suggest that future iterations of the DSM and International Classification of Diseases should consider modifying the criteria for BN to include recurrent subjective binge eating (with or without objective binge eating). There is mounting evidence that subjective binge eating is uniquely tied to distress and psychological functioning in individuals with eating disorders (Wolfe et al., 2009), and the current data provide additional support in the form of prospective findings within a BN treatment trial. Indeed, repeated assessments of objective and subjective binge eating and psychological functioning allowed us to approximate directionality in the associations between some forms of psychopathology, although the overlap in time periods during which binge eating episodes and psychopathology were assessed precluded formal tests of temporal precedence. Previous research suggests that the relationship between binge eating and negative affect is bidirectional (Presnell, Stice, Seidel, & Madeley, 2009; Stice, 1998), but we found that changes in depression symptoms and eating-related psychopathology predicted objectively large loss of control eating episodes, rather than the reverse (although, as noted above, temporal precedence could not be established). Thus, improvements in depression symptoms and/or more general eating-related psychopathology are likely associated with a concomitant reduction in objective binge eating, suggesting that changes in these comorbid symptoms early in treatment may be responsible for the early, rapid changes in objective binge eating observed by our group and other groups (Hildebrandt & Latner, 2006; Niego et al., 1997; Peterson et al., 2000). However, for subjectively large loss of control eating episodes, there was a bidirectional relation between changes in anxiety and eating-related psychopathology and eating episode frequency, and thus it is not clear whether subjective binge eating drives changes in those domains, or the inverse.

The current study was marked by several important strengths, including a prospective design, the use of well-validated measures, and the use of broad criteria for BN, which reflects the heterogeneity of eating disorder psychopathology seen in clinical settings (Fairburn, 2008b). Nevertheless, there were several notable limitations, most of which are accounted for by the fact that this study represented a secondary analysis of data from a trial that was originally designed to assess the impact of psychological treatments on BN symptoms (Wonderlich et al., 2014). First, the sample was composed almost exclusively of Caucasian females, and excluded individuals with current substance use disorders, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Although treatment condition was used as a covariate, the limited sample size prevented an examination of differences between the two treatments. Thus, results require replication in a larger, more diverse sample. Second, EDE measures of binge eating were available only at baseline, end-of-treatment, and 4-month follow-up, precluding examination of changes in these constructs during different phases of treatment. Relatedly, we cannot definitively conclude that changes in subjective binge eating caused changes in eating-related and general psychopathology, although we were able to approximate a unidirectional association for one construct (i.e., depression symptoms). It is also unclear whether the relationship between subjective binge eating and psychopathology, and the lack of concomitant findings pertaining to the relationship between objective binge eating and psychopathology, could be explained by differences in illness severity between participants with and without objective binge eating. Specifically, it is possible that illness severity is greater in individuals who engage in objective binge eating than those who do not—these individuals may be more resistant to global change and this could result in the absence of a relationship between objective binge eating and psychosocial functioning (although adjusting for endorsement of subjective binge eating only at baseline somewhat addresses this concern). Third, the EDE does not offer continuous measures of loss of control and episode size; therefore distinctions between types of loss of control eating episodes may be somewhat arbitrary. Nevertheless, our measurement reflects the way in which pathological eating episodes have been operationalized in the literature (Wolfe et al., 2009), thus enhancing cross-study comparisons. Finally, because data were collected within the context of a treatment study, it is unknown whether similar relationships between loss of control eating and psychopathology would emerge in a naturalistic longitudinal study.

Overall, these results further support the unique relationships between subjective and objective binge eating and eating-related and general psychopathology in individuals with eating disorders. Results have important implications for the nosology and treatment of binge eating and purging syndromes, namely that the experience of loss of control while eating, even in the absence of objectively large amounts of food, is related to distress and impairment in individuals with BN-spectrum disorders. Therefore, the classification scheme for BN may better encompass the experience of individuals with the disorder by including those who report subjective and/or objective binge eating. Future research should continue to explore the validity and prognostic significance of subjective binge eating in order to improve the classification of eating disorders, and develop novel approaches for their treatment that effectively target all types of loss of control eating episodes.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources for this study included grants R01DK061912, R01DK061973, K23DK105234, and P30DK060456 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and grants R34MH077571, R01MH059674, T32MH082761 and K02MH065919 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The research was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. T. L. Smith is the Associate Director for Improving Clinical Care, VA South Central Mental Illness Research, Education & Clinical Center at the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness & Safety (IQuEST; CIN 13-413), Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston Texas. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Abbreviations

- LOC

loss of control

- OBE

objective binge eating

- SBE

subjective binge eating

- BN

bulimia nervosa

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- BED

binge eating disorder

- ICAT

integrative cognitive affective therapy

- CBT-E

enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy

- BMI

body mass index

- EDE

Eating Disorder Examination

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory

- STAI

State Trait Anxiety Inventory

- RSE

Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale

- DAPP-BQ

Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire

- CI

confidence interval

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, text revision. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bagge CL, Trull TJ. DAPP-BQ: Factor structure and relations to personality disorder symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;17(1):19–32. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.1.19.24055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KC, Peterson CB, Frazier P, Crow SJ. Psychometric evaluation of the eating disorder examination and eating disorder examination-questionnaire: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2012;45(3):428–438. doi: 10.1002/eat.20931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini G, Mannucci E, Lo Sauro C, Benni L, Lazzeretti L, Ravaldi C, Ricca V. Different moderators of cognitive-behavioral therapy on subjective and objective binge eating in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: A three-year follow-up study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2012;81(1):11–20. doi: 10.1159/000329358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG. Eating disorders: The transdiagnostic view and the cognitive behavioral theory. In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008b. pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ. Eating disorders. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):407–416. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)12378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay PP, Bacaltchuk J, Stefano S, Kashyap P. Psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa and binging. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2009;7(4):CD000562. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000562.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt T, Latner J. Effect of self-monitoring on binge eating: Treatment response or ‘binge drift’? European Eating Disorders Review. 2006;14(1):17–22. doi: 10.1002/erv.667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Mayer SA, Harnden-Fischer JH. Importance of size in defining binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2001;29(3):294–301. doi: 10.1002/eat.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latner JD, Clyne C. The diagnostic validity of the criteria for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/eat.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jackson DN. Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire: Technical Manual. Port Huron, MI: Sigma Assessment Systems, Inc; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maruta T, Yamate T, Iimori M, Kato M, Livesley WJ. Factor structure of the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Basic Questionnaire and its relationship with the revised NEO personality inventory in a Japanese sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47(6):528–533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, Wonderlich S, Crosby RD. Feeding laboratory studies in patients with eating disorders: A review. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24(2):115–124. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199809)24:2<115::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-h. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199809)24:2<115::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mond JM. Classification of bulimic-type eating disorders: from DSM-IV to DSM-5. Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;1:33. doi: 10.1186/2050-2974-1-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niego SH, Pratt EM, Agras WS. Subjective or objective binge: Is the distinction valid? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22(3):291–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<291::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-i. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199711)22:3<291::AID-EAT8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Nugent S, Mitchell JE, Engbloom S, Mussell MP. Predictors of treatment outcome for binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;28(2):131–138. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(200009)28:2<131::AID-EAT1>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollert GA, Engel SG, Schreiber-Gregory DN, Crosby RD, Cao L, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE. The role of eating and emotion in binge eating disorder and loss of control eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2013;46(3):233–238. doi: 10.1002/eat.22061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EM, Niego SH, Agras WS. Does the size of a binge matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199811)24:3<307::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-q. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199811)24:3<307::AID-EAT8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presnell K, Stice E, Seidel A, Madeley MC. Depression and eating pathology: prospective reciprocal relations in adolescents. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2009;16(4):357–365. doi: 10.1002/cpp.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukrop R, Steinbring I, Gentil I, Schulte C, Larstone R, Livesley JW. Clinical validity of the “Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology (DAPP)” for psychiatric patients with and without a personality disorder diagnosis. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23(6):572–586. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.6.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair SJ, Blais MA, Gansler DA, Sandberg E, Bistis K, LoCicero A. Psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Overall and across demographic groups living within the United States. Evaluation and the Health Professions. 2010;33(1):56–80. doi: 10.1177/0163278709356187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for children. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A comprehensive bibliography. Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Steele AL, Wade TD. A randomised trial investigating guided self-help to reduce perfectionism and its impact on bulimia nervosa: A pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(12):1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Relations of restraint and negative affect to bulimic pathology: A longitudinal test of three competing models. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;23(3):243–260. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199804)23:3<243::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT, Fairburn CG, Mickley D, Sysko R, Parides MK. Treatment of bulimia nervosa in a primary care setting. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):556–561. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Naragon-Gainey K. Personality, emotions, and the emotional disorders. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(4):422–442. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Pennebaker JW. Health complaints, stress, and distress: exploring the central role of negative affectivity. Psychological Review. 1989;96(2):234–254. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.96.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe BE, Baker CW, Smith AT, Kelly-Weeder S. Validity and utility of the current definition of binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42(8):674–686. doi: 10.1002/eat.20728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ. A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 2014;44(3):543–553. doi: 10.1017/s0033291713001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Smith TL. Integrative Cognitive-Affective Therapy for Bulimia Nervosa: A Treatment Manual. New York: Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo W, Mayberry R, Bae S, Singh K, Peter He Q, Lillard JW., Jr A study of effects of multicollinearity in the multivariable analysis. Int J Appl Sci Technol. 2014;4(5):9–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]