Abstract

Acne is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that involves the pathogenesis of four major factors, such as androgen-induced increased sebum secretion, altered keratinization, colonization of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation. Several acne mono-treatment and combination treatment regimens are available and prescribed in the Indian market, ranging from retinoids, benzoyl peroxide (BPO), anti-infectives, and other miscellaneous agents. Although standard guidelines and recommendations overview the management of mild, moderate, and severe acne, relevance and positioning of each category of pharmacotherapy available in Indian market are still unexplained. The present article discusses the available topical and oral acne therapies and the challenges associated with the overall management of acne in India and suggestions and recommendations by the Indian dermatologists. The experts opined that among topical therapies, the combination therapies are preferred over monotherapy due to associated lower efficacy, poor tolerability, safety issues, adverse effects, and emerging bacterial resistance. Retinoids are preferred in comedonal acne and as maintenance therapy. In case of poor response, combination therapies BPO-retinoid or retinoid-antibacterials in papulopustular acne and retinoid-BPO or BPO-antibacterials in pustular-nodular acne are recommended. Oral agents are generally recommended for severe acne. Low-dose retinoids are economical and have better patient acceptance. Antibiotics should be prescribed till the inflammation is clinically visible. Antiandrogen therapy should be given to women with high androgen levels and are added to regimen to regularize the menstrual cycle. In late-onset hyperandrogenism, oral corticosteroids should be used. The experts recommended that an early initiation of therapy is directly proportional to effective therapeutic outcomes and prevent complications.

KEY WORDS: Acne, antibacterials, benzoyl peroxide, combination therapy, oral, retinoids, topical

What was known?

Current Indian and Global Acne guidelines give only an overview in acne management based on acne severity.

Introduction

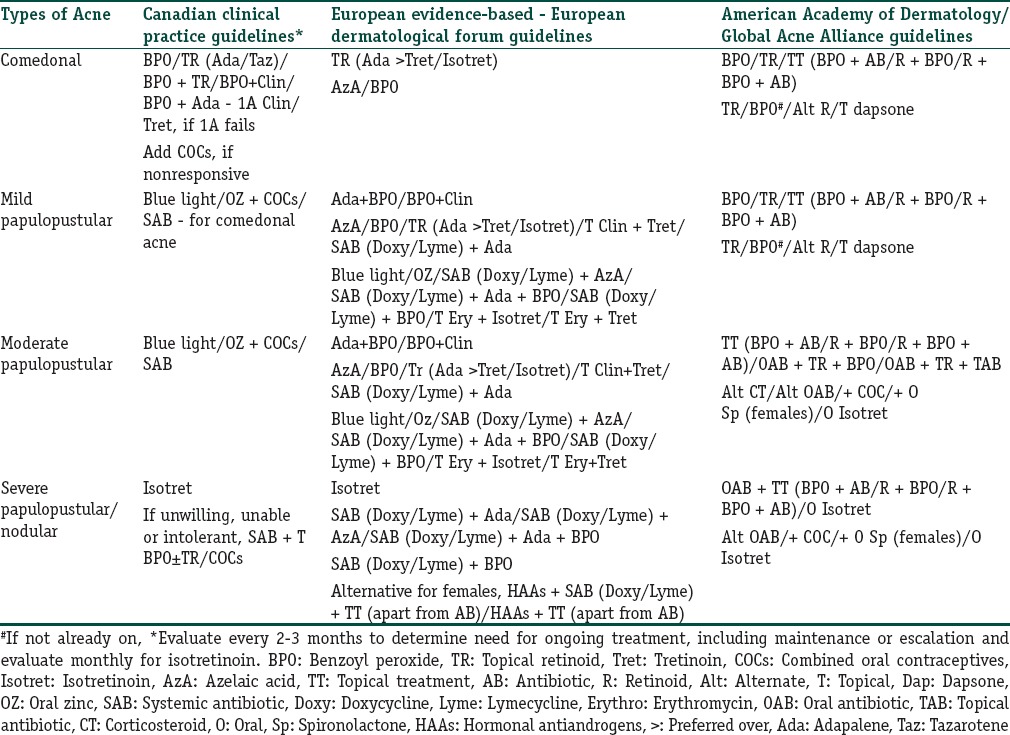

Acne vulgaris is a chronic condition that affects quality of life adversely in about 85% of adolescents and 66.7% of adults.[1,2,3] It starts with the obstruction of pilosebaceous unit, resulting in the formation of comedones (noninflammatory), followed by progression to inflammatory acne that includes papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.[4] The major causal factors involve altered sebum levels (androgen-driven), changes in keratinization, and bacterial colonization of the pilosebaceous units on the face, neck, chest, and back.[5] It is essential to assess severity of acne as well as the individual patient factors for acne management.[6,7,8] Although standard guidelines and recommendations [Table 1] give an overview on the management of mild, moderate, and severe acne, they do not give the relevance and positioning of each of the categories of pharmacotherapy available in the Indian market. This article discusses the available topical and oral acne therapies and presents the suggestions and recommendations by the dermatologists’ panel across India who held discussions in an order to practically define positioning of different market formulations in acne management, address when to prefer monotherapy or combination therapy with rationality of available combinations, review within class and comparison of strength of different available molecules, and consider formulation innovations along with the role of the adjunctive treatments.

Table 1.

Various guidelines and recommendations for management of acne

Management of Acne using Topical Agents

Monotherapy

Retinoids

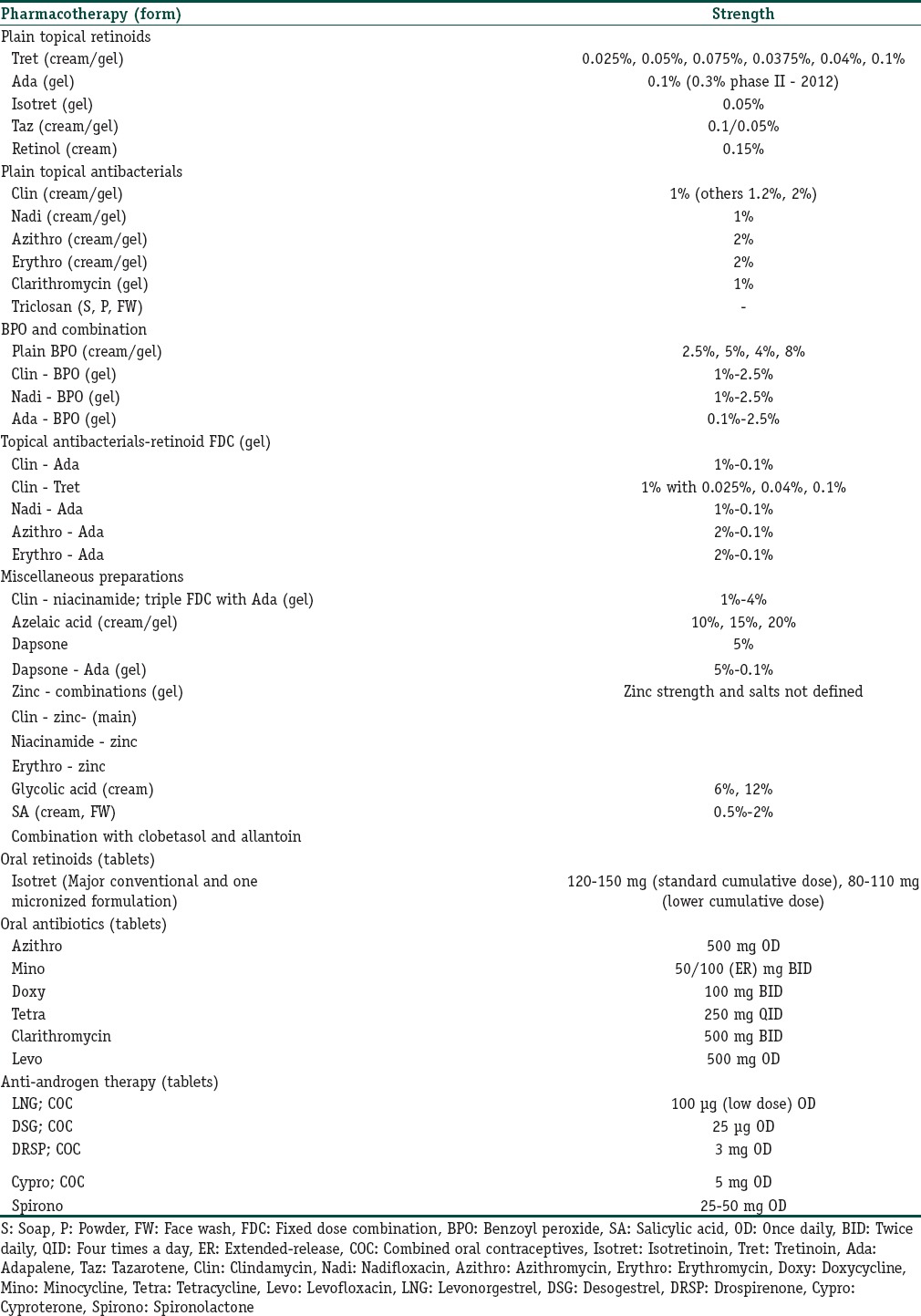

Retinoids have a potential role in decreasing sebum production along with in-regulation of desquamation and adhesion of keratinocyte, thus resulting in comedolysis and suppression of new microcomedonal development.[9,10,11,12] They are a preferred choice for scars and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) of the skin.[9,13,14] Tretinoin, isotretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene are considered as the first choice of treatment and maintenance therapy. Topical retinoids are used as monotherapy in noninflammatory acne and in combination with other topical agents in inflammatory and more severe forms of acne.[15,16,17,18,19] However, flaring up of acne during initial weeks of treatment limits its use or warrants combination with other agents [Tables 2 and 3].[20,21]

Table 2.

Various topical and oral pharmaceutical acne preparations available in India

Table 3.

Studies focussing on topical monotherapy for management of acne

Expert opinion

Place of therapy

Micronized topical retinoids are a preferred choice, where adapalene (0.1%) is considered as the first-line therapy. Adapalene gel (0.3%) may have future relevance as maintenance therapy in patients with acne scars. Tretinoin is preferred in the trunk, back, and arm acne for priming before peels and lasers during maintenance phase. However, it should be stopped 2–3 days and 5–6 days before these procedures, respectively. The relevant strengths of tretinoin that are used in India are 0.025% and 0.05% and as micronized formulation (0.1%). Tazarotene, due to poor tolerance, is usually not used in Indian acne management. Isotretinoin is not preferred topically, whereas retinol and retinaldehyde may be used as maintenance therapy due to better tolerance. They can also contribute to antiaging effects and combined with antioxidant Vitamins C and E.

Application

All retinoids are prescribed once a day in the evening or at night. They should be applied after washing face with a mild cleanser (cetyl/stearyl alcohol based) and drying completely. After 10 min, retinoids formulation should be applied on the whole face without rubbing/massaging. If moisturizer is being used, they should be applied immediately after the moisturizer application. Short contact therapy with initial ½ h application, then 1 h, and then overnight application is recommended to decrease irritation and retinoid dermatitis (dryness).

Maintenance therapy

Maintenance therapy is recommended after resolution of all visible lesions to treat microcomedones and to prevent acne flare-up or recurrence. Treatment duration should last until a 6-month acne-free period on maintenance therapy is achieved. Retinoid maintenance treatment may be tapered down to twice/thrice a week, the frequency depending on the tell-tale remnant signs of the primary lesions such as comedones and pigmentation.

Antibacterials

Antibacterials act potentially against Propionibacterium acnes, the most common causal organism in acne, and possess surface-acting capability; hence, they can prevent the formation of inflammatory lesions on the skin surface.[22] Topical antibiotics are recommended for the treatment of mild to moderate acne (inflammatory lesions) [Tables 2 and 3].

Expert opinion

Clindamycin and nadifloxacin are currently preferred in combinations with retinoids or benzoyl peroxide (BPO). Nadifloxacin has potential advantages and comparable efficacy with clindamycin, effect on biofilms, absence of documented resistance, and relative protection from Gram-negative folliculitis (GNF) due to broad-spectrum coverage.[23,24] Erythromycin and clarithromycin are not preferred currently in Indian acne practice. Lincomycin (2%) gel is also available though market is low and not seeming under active promotion. Triclosan is not preferred due to carcinogenic potential, and it may have some role in scabies. In acne pathogens, i.e., P. acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and Malassezia furfur, M. furfur back acne is treated using itraconazole (twice daily; BID 100 mg for 14 days) after doing hematological and liver function test.

Benzoyl peroxide

BPO is a nonantibiotic antimicrobial agent that allows generation of reactive oxygen species within the follicle and thus elicits bactericidal properties. It is effective for the treatment of inflammatory lesions and provides protection from antibiotic resistance [Tables 2 and 3].[16,23,24,25] Some guidelines suggest systematic approach along with the utilization of BPO mainly in case of inflammatory lesions.[5,9,26]

Expert opinion

BPO (2.5%) is preferred over 5% strength due to comparable efficacy and better tolerance. Plain BPO may be used in newly diagnosed adolescent mild acne and as topical application in patients on systemic isotretinoin. In other cases, combination of BPO with adapalene or antibacterials is used. BPO (5%) with sulfur is reserved for resistant back, arm, and trunk acne. It has been suggested to use it ½ h before bath due to its odor. Coacrylate polymer gels or microencapsulated gels should be preferred for better stability and tolerance.

Combination therapy

Combination therapies are preferred to avoid skin sensitization, antibiotic resistance as well as to enhance the treatment outcomes.[9,24,26,27,28,29,30,31] Multimodal therapy targeting different pathological processes, simultaneously, leads to a better outcome due to synergistic effects.[32] Studies also report that combination therapy plays a role in improving patient adherence due to incorporation of simplified and personalized daily regimen.[32,33] Table 2 enlists various combination therapies available in the market.

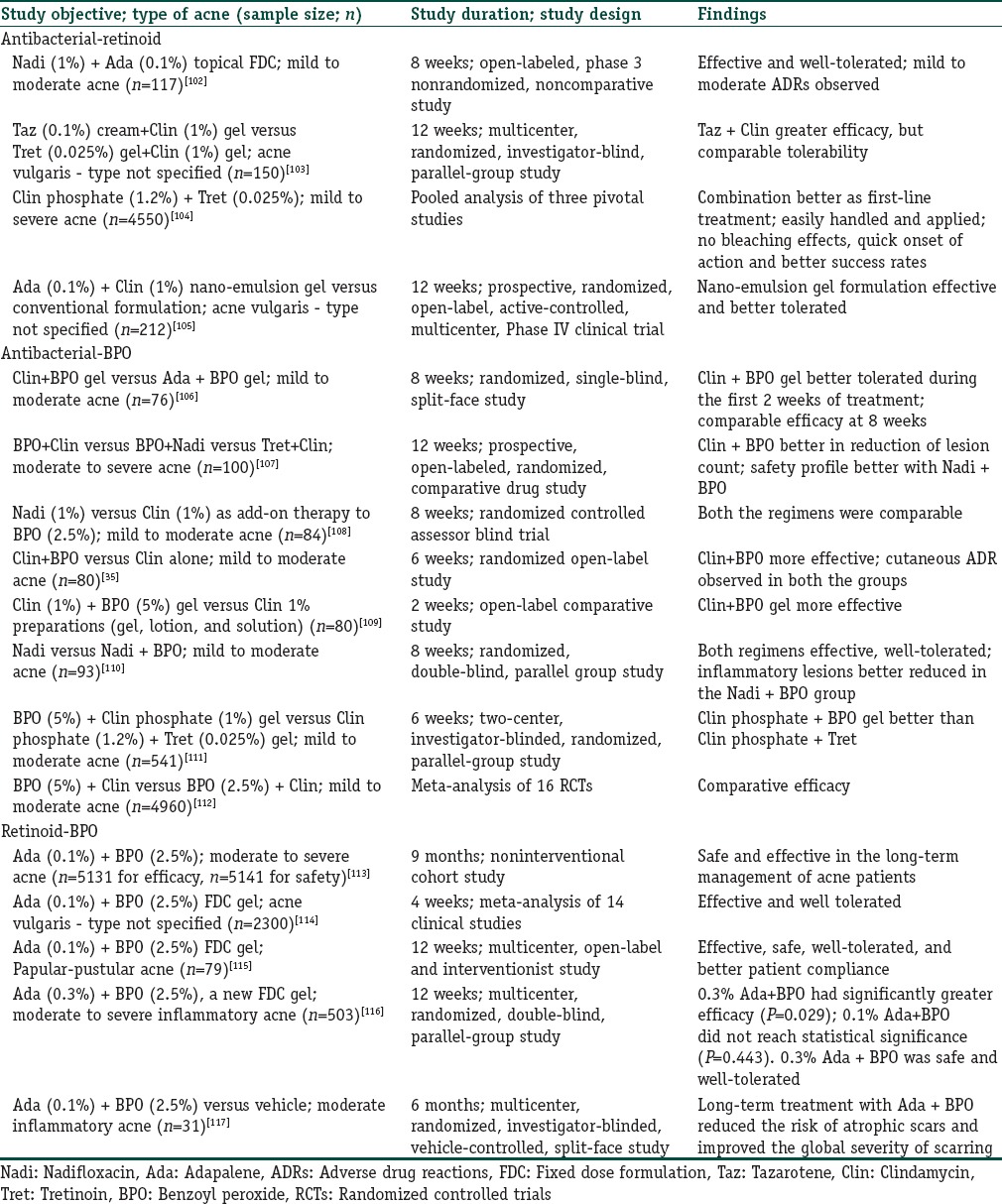

Antibacterial-retinoid

The combination therapy of topical retinoid and antibiotic is an essential treatment measure and is contemplated as the first-line therapy for the treatment of moderate to severe acne. Retinoids assist penetration of antibacterials into the pilosebaceous unit (colonization site for P. acnes), hence allowing better efficacy [Table 4].[31,34]

Table 4.

Studies focussing on topical combination therapy for management of acne

Expert opinion

BPO-antibacterials are recommended for pustule-nodular acne, whereas BPO-retinoid/antibacterial-retinoids are prescribed in comedonal papulopustular acne. Antibacterial-retinoids may be prescribed, especially if perceived tolerance with BPO-retinoid combinations is poor, formulation technology (microencapsulation) can determine the choice.

Antibacterial-benzoyl peroxide

The keratolytic action of BPO enhances the antibacterial activity of antibacterials. Further, the bactericidal properties of BPO help in reduction of microbial resistance to the topical antibiotics [Table 4].[24,25,35,36]

Expert opinion

BPO-antibacterial combination may be prescribed in acute inflammatory acne (with large number of pustules) or moderate acne tending to severe acne for early lesion control. It can potentiate action on biofilms and can be given in morning with adapalene at night. It may also be prescribed as topical therapy in patients on systemic isotretinoin and when topical retinoids are not tolerated.

Adapalene (retinoid)-benzoyl peroxide

In mild to moderate acne, adapalene-BPO is the most preferred combination and used as the first-line therapy.[30] The relapses in severe and moderate to severe acne patients can be prevented with the use of adapalene-BPO combination as maintenance therapy (for 6–12 months) subsequent to treatment with oral isotretinoin.[37,38] Combination of BPO with other retinoids is found to be unstable and hence avoided [Table 4].[29]

Expert opinion

Adapalene-BPO is the most preferred combination and used as the initial and first-line therapy in mild-moderate inflammatory acne (mainly comedones with few papules/pustules). This is also preferred in maintenance phase over retinoid monotherapy to tackle intermittent activity and flare-ups.

Miscellaneous Agents

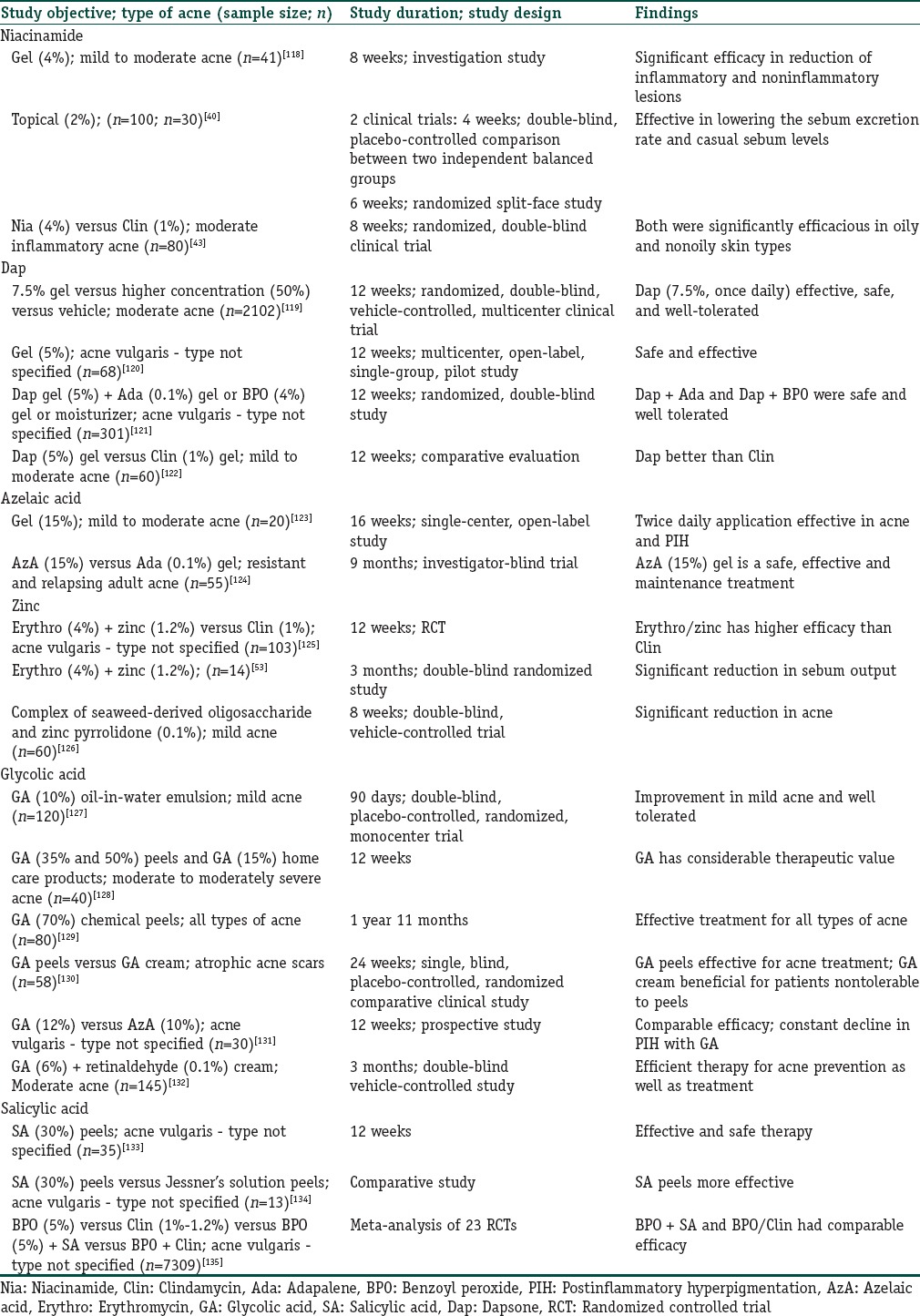

Niacinamide

The inhibitory action of niacinamide on sebocyte secretions results in less sebum production and reduced oiliness of the skin.[39,40] It is beneficial in pustular as well as papular acne due to its anti-inflammatory properties[41] and is also a choice of treatment in cases with antimicrobial resistance [Tables 2 and 5].[42,43]

Table 5.

Studies focussing on the role of miscellaneous agents in management of acne

Expert opinion

For active treatment, niacinamide (4%) in dermato-cosmetic mattifying creams are used for daytime use and retinoids/BPO/anti-infective combinations are used at night time. During maintenance therapy, combination with adapalene is preferred for daytime use. It is also used in the cases of PIH for skin lightening and for patients with oily skin.

Dapsone

Dapsone is used in acne due to its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity. Its low cost makes it affordable and available to acne patients in developing countries.[44,45,46] Topical gel of dapsone (5%) is usually used to treat inflammatory and noninflammatory acne lesions.[47]

Expert opinion

Dapsone is used more of an elimination molecule due to intolerance or inadequate response to BPO/retinoids in inflammatory acne (effect seen only after 6 weeks). However, it has efficient action in scalp folliculitis and acne inversa (given twice a day with adapalene-BPO at night time).

Azelaic acid

Azelaic acid inhibits protein synthesis of the P. acnes species without bacterial resistance.[48,49] Its bacteriostatic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antikeratinizing properties enhance its antiacne potential.[50] Its combination with clindamycin 1% gel, BPO 4% gel, and tretinoin 0.025% cream is an effective acne treatment regimen.[30,51]

Expert opinion

It is effective but its use is limited due to unpredictable irritation and it has been suggested to consider liposomal preparation. Initially, 10% strength is given which is then scaled up to approximately 20%. However, it is not recommended in fixed-dose combinations. It is preferred as a morning application in acne with pigmentation along with retinoid combination in the evening.

Zinc

Zinc in combination with or without nicotinamide has been recommended as a budding alternate acne treatment with reduced adverse effects (AEs) of antibiotics. It has anti-inflammatory activity and inhibits the P. acnes lipases and free fatty acids, thereby reducing the P. acnes counts.[52] Furthermore, it is found to possess antiandrogenic activity which enables in suppression of sebum levels.[53] Its combination with antibiotics facilitates antibiotic absorption as well.[52,54]

Expert opinion

Role of zinc is not established. Its salts with pyrrolidone carboxylic acid and gluconate may be used in the combination dermato-cosmetic products with niacinamide and soothing agents.

Hydroxy acids

Glycolic acid (alpha hydroxy acid) and salicylic acid (beta hydroxy acid) are used as chemical peels for facial resurfacing. They mainly act by stimulating reepithelialization and skin rejuvenation.[3,44] However, they are not recommended as the first-line treatment for acne due to safety issues.[44,55]

Expert opinion

Glycolic acid is used as a cream with 6% and 12% concentration. It may also be used in highly comedonal acne and in the presence of pigmentation. Salicylic acid (2%) may have a role as supportive therapy in acne maintenance. Keratolytic action below 3% is uncertain, and it may actually be keratoplastic. It is mostly used as face wash.

Herbal Agents

Since ancient times, the herbal therapies such as Yarrow (Achillea millefolium), Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis), Burdock (Arctium lappa), Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), Neem (Azadirachta indica), Barberry (Berberis vulgaris), False unicorn (Chamaelirium luteum), and Goldthread (Coptis chinensis) are being used for the treatment of acne.[56,57] These agents are found to have anti-inflammatory, moisturizing, and soothing properties.[22]

Expert opinion

For herbal preparations, substantiating data are poor; A. vera as a soothing agent may have some acceptance. Sulfur is used for back acne ½ h before bath, but it is not prescribed for facial acne.

Other Suggestions/Recommendations by Experts

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

PIH, also known as acne hyperpigmented macule, is an acquired hypermelanosis that occurs due to inflammation or injury to the cutaneous and can affect all types of skin. It mainly affects the skin color of patients and is widespread in people with darker skin. Basically, PIH is observed in the areas of acne papules, pustules, and nodules. Moreover, the intensity of PIH is based on the severity of inflammation and the type of skin.[59,60]

Expert opinion on postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Sunscreen and removal of triggering factors should be implemented in all patients. Hydroquinone (2/4%) or triple-agent therapy (hydroquinone/tretinoin/fluocinolone), kojic acid and Vitamin C, azelaic acid, topical retinoids (adapalene/tretinoin/tazarotene) are used as the first-line therapy. Chemical peels (glycolic acid, salicylic acid) are recommended as the second-line therapy while laser therapy can be considered as the third-line therapy. These therapies are used along with regular antiacne treatment. The duration of treatment is variable; most patients respond 6–8 weeks after the therapy. Although skin lighting is an additional advantage with azelaic acid and topical retinoids, tolerability (irritation and dryness) limits their use; concerns more with Indian skin.

Face wash

Face washes used with retinoids should be a mild cleanser. Cetyl, stearyl alcohol should be used for mild cleansing property without exfoliative/acidic component. BPO cleansers and foams may be used in truncal acne. For acne maintenance, salicylic acid (2%) is the most preferred, whereas glycolic acid (1%) can be used as an exfoliator, but it may increase irritation. A 2-min contact time for face wash is advised.

Application do's and don’ts

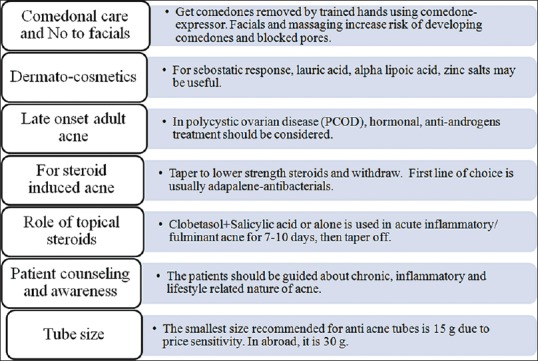

Azelaic acid, glycolic acid, retinoids, plain BPO, and BPO-retinoid combination should be applied on full face, whereas antibacterials and their combination with BPO should be applied on lesions. Massaging and rubbing are not recommended. Gels are preferred over creams. Creams may be used in very dry weather (winter) or in case of skin dryness in response to retinoids. Moisturizer (noncomedogenic, nongreasy, nonsticky, and nonfragrant) should be applied after face wash on dry face, twice daily, whereas antidandruff shampoo has been recommended to be used twice weekly. Some miscellaneous points discussed by experts are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Miscellaneous recommendation(s) by experts

Management of Acne using Oral Agents

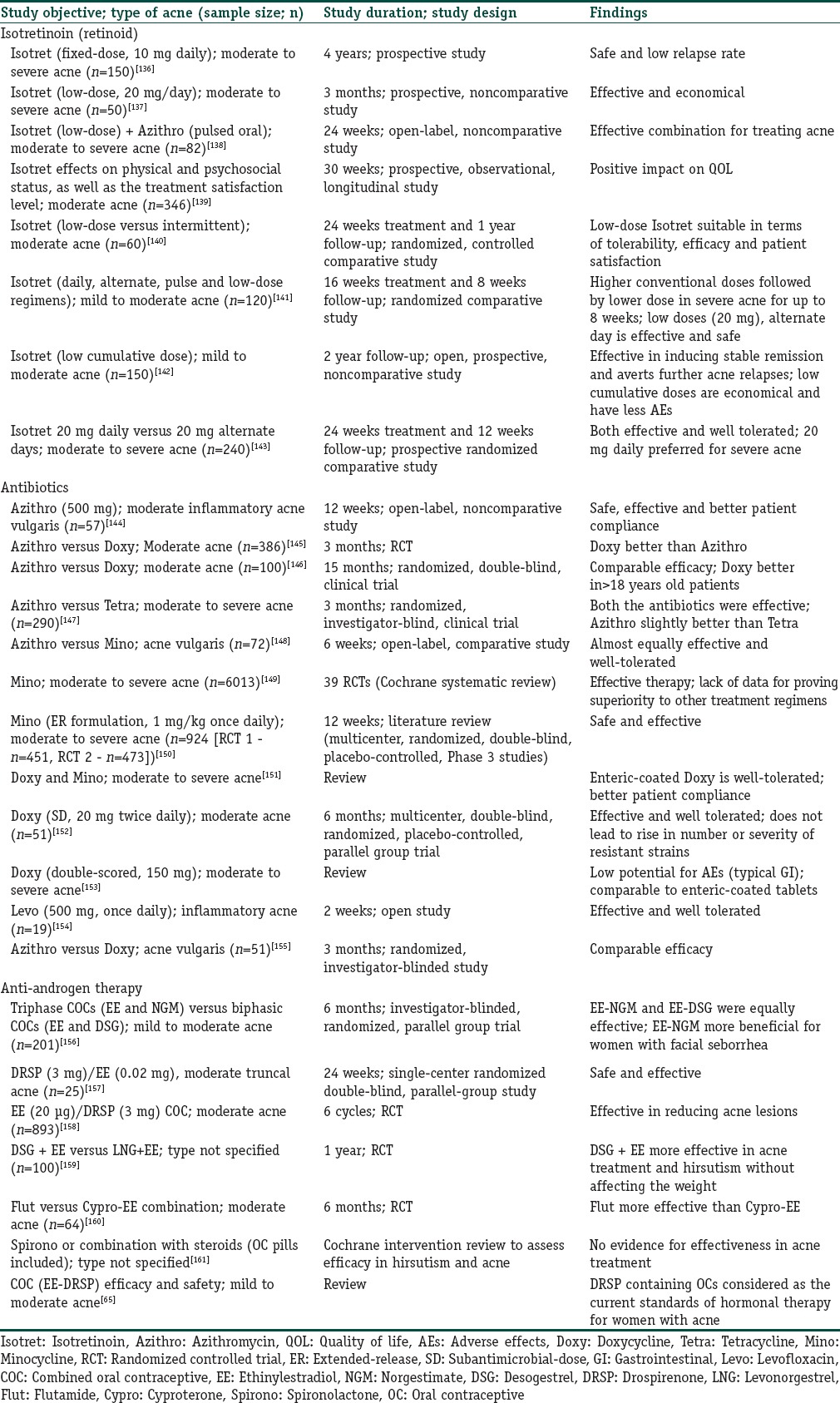

Isotretinoin (retinoid)

Currently, isotretinoin is the only oral retinoid available in India for the treatment of acne. Isotretinoin targets the four major factors involved in the mechanism of acne owing to the following effects, viz., stabilizing the follicular desquamation, suppressing the sebum production, preventing the P. acnes growth, and allowing anti-inflammatory action [Tables 2 and 6].[7,19,60]

Table 6.

Studies focussing on oral therapy for management of acne

Expert opinion

Although the literature recommendation is for severe nodular acne, in real-life practice, isotretinoin is used earlier in the treatment of acne (moderate-severe). A cumulative dose of 120–150 mg/kg isotretinoin is the best treatment regimen for moderate to severe acne. If patients relapse (0.5–1 mg/kg) after achieving target cumulative dose (120–150 mg/kg), repeat cycle should be given at a double dose (1–2 mg/kg). Overall, low-dose regimens (0.3–0.4 mg/kg) are economical and have better patient acceptance. Due to early response or improvement after starting isotretinoin, patients may not come back for follow-up and stop therapy on their own leading to relapses as cumulative required dose is not reached.

Macrocomedonal flare-up is observed in 20%–30% cases during isotretinoin treatment and should be handled with patient counseling and using a low-dose isotretinoin or addition of pulse dose of azithromycin. It lasts for almost 4–5 weeks and usually does not require tapering or stopping the drug (continuing the same dose). Flare-ups may also be managed with an initial short course of oral corticosteroids. Association of isotretinoin with depression and suicidal tendency is controversial and not proved; however, cautious use is advised in vulnerable population. Concomitant use of laser therapy and isotretinoin in Indian patients may be acceptable.

Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics are generally preferred in moderate to severe inflammatory acne.[9] They are found to possess antimicrobial as well anti-inflammatory properties.[7,24,61] Likewise topical antibiotics, oral antibiotics should also be given in combination with other agents to minimalize the bacterial resistance and enhance treatment outcomes. Generally, they are prescribed in combination with topical retinoids or BPO [Tables 2 and 6].[60,61]

Expert opinion

The management of acne should focus on the treatment of inflammation which supports the use of oral antibiotics in acne. Antibiotics should be used till the inflammation is visible. Afterward, the patients should be managed with isotretinoin.

Mild acne/Grade I should be treated with topical agents such as BPO and retinoids. A 3-month low-dose oral antibiotic treatment (to reduce microbial resistance) can be given to patients if they do not respond to topical agents. Combination of isotretinoin at a higher dose (20–30 mg) and doxycycline is contraindicated (due to risk of pseudotumor cerebri, hair fall, and benign intracranial hypertension). Combination of isotretinoin and azithromycin is preferred in case of Grade III or IV or severe papulopustular acne.

Minocycline seems to far best in terms of least resistance and efficacy; however, reliable evidence does not support its superiority or benefits in acne-resistant to other therapies. Moreover, dose ambiguity, unpredictable safety (risk of phototoxic vestibulotoxic, autoimmune, and hypersensitive reactions), and inconsistent safety benefits of minocycline modified-release (MR) formulations do not substantiate the minocycline use as the first-line drug in acne treatment.

Minocycline and doxycycline are seen to have comparable efficacy. Although gastric intolerance is higher for doxycycline, this can be reduced with enteric-coated or double-scored tablets or using staggered dosing. Low dose doxycycline (subantimicrobial dose 40 mg MR) has been used in treatment of acne and found to prevent development of resistant strains.

Lymecycline is a new drug with low antimicrobial resistance and can show significant benefits in acne treatment. However, it is not used as the first line of therapy due to price and availability issues. Levofloxacin can be used as an anti-acne oral antibacterial due to lowest resistance; however, its anti-inflammatory action is not established.

In case of pregnant women, azithromycin alone is prescribed with or without topical agents. A 3-day course (Friday, Saturday, and Sunday) per week for 6–8 weeks is the best azithromycin regimen (due to 96 h half-life of azithromycin).

Pulse clarithromycin therapy (250 mg twice daily) for 7 days (repeated after a gap of 10 days) has been used in isolated case reports in patients with moderate to severe acne that are ineffective to doxycycline, minocycline, and erythromycin treatment regimen.[62]

BPO in combination with oral antibiotics is a beneficial therapy as it reduces the dependence on systemic agents and further prevents the development of P. acnes resistance.[61,63]

Antiandrogen therapy

Androgens play a key role in the development of acne vulgaris through the induction of sebum production.[5] Therefore, antiandrogenic therapies can be useful for the management of female patients with moderate to severe acne. The contraceptive hormones have a role in reducing the androgen-induced sebum production. It enhances the production of sex hormone-binding globulin, thereby decreasing the free testosterone (biologically active) levels in women. Contraceptives are preferred in the treatment of hormone-related acne; progestins are particularly recommended despite their no androgen activity [Tables 2 and 6].[64,65,66]

Expert opinion

Females <14 years or >35 years should be treated with antiandrogens after an opinion of endocrinologist/gynecologist. Oral contraceptives (OCs) are must in women with high androgens and are added to regimen to regularize the menstrual cycle. Women with polycystic ovary syndrome, premenstrual flares, and other clinical signs should be prescribed with antiandrogen therapy (mainly cyproterone) in combination with OCs. Spironolactone is not used in acne because of less role/low evidence of sebocytes in acne. However, in patients with high androgens or with late-onset acne (above 40 years of age), spironolactone can be prescribed as monotherapy in low dose. OC and spironolactone should be tapered down in terms of dose to avoid hair fall. Flutamide is not used because of the associated AEs.

Miscellaneous agents

Oral corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids are used in cases with late-onset hyperandrogenism (up to 6 months).[67,68] In case of severe acne, low-dose oral corticosteroids along with low-dose isotretinoin are used.[69,70] Oral corticosteroids are generally used as a 2–3-week course (0.5–1.0 mg/kg/day methylprednisolone) without tapering down. Low dose of isotretinoin (0.25 mg/kg/day) in combination with oral corticosteroids should be used for 2–3 weeks after which oral corticosteroids should be stopped (over the next 6 weeks), followed by continued isotretinoin at a dose of 0.25 mg/kg/day depending on the condition of the patient.[71]

Expert opinion

Oral corticosteroids should be used in late-onset hyperandrogenism (up to 6 months). They should be used as a 2–3-week course (20 mg prednisolone or 16 mg methylprednisolone) without tapering down. Low dose of isotretinoin (10–20 mg) in combination with oral corticosteroids should be used for 2–3 weeks after which oral corticosteroids should be stopped followed by continued isotretinoin at a dose of 20 mg. Prednisolone is recommended for premenstrual flares and dexamethasone in cases with congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Diet

The diet with high glycemic content (milk/dairy product) plays a crucial role in the development of acne and relates to longer duration/persistence of acne.[72] The underlying reasons may be due to the presence of hormone/bioactive molecule in the skimmed milk or insulinotropic effect of milk protein which elevates the serum level of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1.[73] Further, hyperglycemic diet causes reduction in the levels of adiponectin, which results in upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and downregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines.[74,75,76,77] It is also responsible for the rise in oxidative stress and decline in serum level of antimicrobial peptide, both of which results in triggering the comedogenesis and eliciting the inflammation.[78,79,80] Zinc can be used as an add-on therapy due to its sebosuppressive activity.[81] Omega fatty acids are used as individualized treatment option due to anti-inflammatory or antioxidant effects.[82]

Specific Acne Allied Disorders

Acne inversa

Acne inversa (also called hidradenitis suppurativa) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the regions of apocrine gland (axillary and anogenital).[83] Antibiotics, antiandrogen, and retinoids are useful only in exacerbations of the disease or as the perioperative treatment.[84]

Acne exocriee

Some acne patients develop the habit of picking their skin (neurotic or psychogenic problem) known as acne excoriee.[85] It can be managed with serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant, a cognitive behavioral method that may provide benefits to such patients.[86]

Gram-negative folliculitis

GNF is caused due to intercession and substitution of Gram-positive flora of acne affected skin by Gram-negative bacteria. The patients with acne or rosacea who are on prolonged treatment with systemic antibiotics may develop GNF. It is generally noticeable in patients after 3–6 months of ineffective prolonged therapy with oral antiacne antibiotics. Oral isotretinoin (0.5–1 mg/kg daily for 4–5 months) is the most effective cure for GNF in acne or rosacea.[87]

Conclusion

The four well-known pathogenic factors responsible for acne are generally managed by topical as well as oral therapies. Although topical therapy is the mainstay as well as the first-line treatment prescribed for patients suffering from noninflammatory comedones to moderate inflammatory acne, oral therapies are preferred in cases with severe nodular acne. An early initiation of therapy is directly proportional to effective therapeutic outcomes. However, the complexity of the disease as well as interpatient differences warrants combination of various agents to be followed. There is a need to develop a daytime applicable dermato-cosmetic product for both, active acne and maintenance therapy, with mattifying effects. Incorporation of cosmetic daily regimen would result in affluent application of product and improved patient adherence which would further make the clinicians and patients overlook the cost involved in combined therapies.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

First Indian Expert Opinion based on clinical evidence and clinical expertise which provides a practical module for in clinic use addressing;

Place and positioning along with the rationality of all available topical and oral acne therapies in India.

Provides insights on combination vs monotherapy their class, strength comparison along with formulation innovations.

Particularized role of adjunctive therapies (face wash, moisturizer and miscellaneous topical therapy) along with their do's and don’ts in acne management.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contribution of Mr. Prince Uppal and his team for facilitation of SPARC scientific meetings and discussions. We also acknowledge Knowledge Isotopes Pvt. Ltd., (www.knowledgeisotopes.com) for the medical writing support.

References

- 1.Dressler C, Rosumeck S, Nast A. How much do we know about maintaining treatment response after successful acne therapy? Systematic review on the efficacy and safety of acne maintenance therapy. Dermatology. 2016;232:371–80. doi: 10.1159/000446069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durai PC, Nair DG. Acne vulgaris and quality of life among young adults in South India. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:33–40. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.147784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowe WP, Shalita AR. Effective over-the-counter acne treatments. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:170–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toyoda M, Morohashi M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc. 2001;34:29–40. doi: 10.1007/s007950100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:361–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedlander SF, Baldwin HE, Mancini AJ, Yan AC, Eichenfield LF. The acne continuum: An age-based approach to therapy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2011;30(3 Suppl):S6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haider A, Shaw JC. Treatment of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2004;292:726–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Archer CB, Cohen SN, Baron SE. British Association of Dermatologists and Royal College of General Practitioners. Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37(Suppl 1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gollnick H, Cunliffe W, Berson D, Dreno B, Finlay A, Leyden JJ, et al. Management of acne: A report from a Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(1 Suppl):S1–37. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyden JJ. A review of the use of combination therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(3 Suppl):S200–10. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)01154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millikan LE. The rationale for using a topical retinoid for inflammatory acne. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:75–80. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt N, Gans EH. Tretinoin: A review of its anti-inflammatory properties in the treatment of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:22–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thielitz A, Gollnick H. Topical retinoids in acne vulgaris: Update on efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:369–81. doi: 10.2165/0128071-200809060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gans L, Kligman E. Re-emergence of topical retinol in dermatology. J Dermatolog Treat. 2000;11:47–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strauss JS, Krowchuk DP, Leyden JJ, Lucky AW, Shalita AR, Siegfried EC, et al. Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:651–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James WD. Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1463–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp033487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramanathan S, Hebert AA. Management of acne vulgaris. J Pediatr Health Care. 2011;25:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan HH. Topical antibacterial treatments for acne vulgaris: Comparative review and guide to selection. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:79–84. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200405020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chivot M. Retinoid therapy for acne. A comparative review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:13–9. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200506010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zaenglein AL. Topical retinoids in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhavan A, Bershad S. Topical acne drugs: Review of clinical properties, systemic exposure, and safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:473–92. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox L, Csongradi C, Aucamp M, du Plessis J, Gerber M. Treatment modalities for acne. Molecules. 2016;21 doi: 10.3390/molecules21081063. pii: E1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gamble R, Dunn J, Dawson A, Petersen B, McLaughlin L, Small A, et al. Topical antimicrobial treatment of acne vulgaris: An evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:141–52. doi: 10.2165/11597880-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyden JJ, Del Rosso JQ, Webster GF. Clinical considerations in the treatment of acne vulgaris and other inflammatory skin disorders: A status report. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elston DM. Topical antibiotics in dermatology: Emerging patterns of resistance. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nast A, Dréno B, Bettoli V, Degitz K, Erdmann R, Finlay AY, et al. European evidence-based (S3) guidelines for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl 1):1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, Katz HI, Kempers SE, Huerter CJ, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: Combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leyden JJ, Krochmal L, Yaroshinsky A. Two randomized, double-blind, controlled trials of 2219 subjects to compare the combination clindamycin/tretinoin hydrogel with each agent alone and vehicle for the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavers I. Diagnosis and management of acne vulgaris. Nurse Prescr. 2014;12:330–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gollnick HP, Krautheim A. Topical treatment in acne: Current status and future aspects. Dermatology. 2003;206:29–36. doi: 10.1159/000067820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, Dréno B, Kang S, Leyden JJ, et al. New insights into the management of acne: An update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 Suppl):S1–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu LW, Vender RB. Newer approaches in topical combination therapy for acne. Skin Therapy Lett. 2011;16:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, Clark AR, Taylor SL, Fleischer AB, Jr, et al. Simplifying regimens promotes greater adherence and outcomes with topical acne medications: A randomized controlled trial. Cutis. 2010;86:103–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jain GK, Ahmed FJ. Adapalene pretreatment increases follicular penetration of clindamycin: In vitro and in vivo studies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:326–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.34010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apoorva DM, Sharath Kumar BC, Vanaja K. Comparative study of effectiveness of clindamycin monotherapy and clindamycin-benzoyl peroxide combination therapy in grade II acne patients. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2014;7:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Degitz K, Ochsendorf F. Pharmacotherapy of acne. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:955–71. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poulin Y, Sanchez NP, Bucko A, Fowler J, Jarratt M, Kempers S, et al. A 6-month maintenance therapy with adapalene-benzoyl peroxide gel prevents relapse and continuously improves efficacy among patients with severe acne vulgaris: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1376–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bettoli V, Borghi A, Zauli S, Toni G, Ricci M, Giari S, et al. Maintenance therapy for acne vulgaris: Efficacy of a 12-month treatment with adapalene-benzoyl peroxide after oral isotretinoin and a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2013;227:97–102. doi: 10.1159/000350820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Namazi MR. Nicotinamide in dermatology: A capsule summary. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:1229–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Draelos ZD, Matsubara A, Smiles K. The effect of 2% niacinamide on facial sebum production. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2006;8:96–101. doi: 10.1080/14764170600717704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gehring W. Nicotinic acid/niacinamide and the skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2004;3:88–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shalita AR, Smith JG, Parish LC, Sofman MS, Chalker DK. Topical nicotinamide compared with clindamycin gel in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:434–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khodaeiani E, Fouladi RF, Amirnia M, Saeidi M, Karimi ER. Topical 4% nicotinamide vs. 1% clindamycin in moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:999–1004. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaminsky A. Less common methods to treat acne. Dermatology. 2003;206:68–73. doi: 10.1159/000067824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coutinho B. Dapsone (Aczone) 5% gel for the treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:451. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wozel G, Blasum C. Dapsone in dermatology and beyond. Arch Dermatol Res. 2014;306:103–24. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1409-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simonart T. Newer approaches to the treatment of acne vulgaris. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:357–64. doi: 10.2165/11632500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shemer A, Weiss G, Amichai B, Kaplan B, Trau H. Azelaic acid (20%) cream in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:178–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00392_6.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thiboutot D, Thieroff-Ekerdt R, Graupe K. Efficacy and safety of azelaic acid (15%) gel as a new treatment for papulopustular rosacea: Results from two vehicle-controlled, randomized phase III studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:836–45. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Draelos Z, Kayne A. Implications of azelaic acid's multiple mechanisms of action: Therapeutic versatility. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2 Suppl 2):AB40. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Webster G. Combination azelaic acid therapy for acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2 Pt 3):S47–50. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2000.108318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bae YS, Hill ND, Bibi Y, Dreiher J, Cohen AD. Innovative uses for zinc in dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piérard-Franchimont C, Goffin V, Visser JN, Jacoby H, Piérard GE. A double-blind controlled evaluation of the sebosuppressive activity of topical erythromycin-zinc complex. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;49:57–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00192359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.James KA, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Emerging drugs for acne. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:649–59. doi: 10.1517/14728210903251690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhate K, Williams HC. What's new in acne? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2011-2012. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:273–7. doi: 10.1111/ced.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azimi H, Fallah-Tafti M, Khakshur AA, Abdollahi M. A review of phytotherapy of acne vulgaris: Perspective of new pharmacological treatments. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patel SD, Shah S, Shah N. A review on herbal drugs acting against acne vulgaris. J Pharm Sci Biosci Res. 2015;5:165–71. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis EC, Callender VD. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: A review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:20–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kubba R, Bajaj A, Thappa D, Sharma R, Vedamurthy M, Dhar S, et al. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dawson AL, Dellavalle RP. Acne vulgaris. BMJ. 2013;346:f2634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Del Rosso JQ, Kim G. Optimizing use of oral antibiotics in acne vulgaris. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rathi SK. Pulse clarithromycin therapy in severe acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2002;47:234–5. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanghetti E. The evolution of benzoyl peroxide therapy. Cutis. 2008;82(5 Suppl):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ebede TL, Arch EL, Berson D. Hormonal treatment of acne in women. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan JK, Ediriweera C. Efficacy and safety of combined ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone oral contraceptives in the treatment of acne. Int J Womens Health. 2010;1:213–21. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rizzo L, Dobrovsky V, Danilowicz K, Kral M, Cross G, Serra HA, et al. Low-dose glucocorticoids in hyperandrogenism. Medicina (B Aires) 2007;67:247–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nader S, Rodriguez-Rigau LJ, Smith KD, Steinberger E. Acne and hyperandrogenism: Impact of lowering androgen levels with glucocorticoid treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(2 Pt 1):256–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)70161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mehra T, Borelli C, Burgdorf W, Röcken M, Schaller M. Treatment of severe acne with low-dose isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:247–8. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karvonen SL, Vaalasti A, Kautiainen H, Reunala T. Systemic corticosteroid and isotretinoin treatment in cystic acne. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:452–5. doi: 10.2340/000155557352455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162–9. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.3.9364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pappas A. The relationship of diet and acne: A review. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:262–7. doi: 10.4161/derm.1.5.10192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kumari R, Thappa DM. Role of insulin resistance and diet in acne. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:291–9. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.110753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.de Oliveira C, de Mattos AB, Biz C, Oyama LM, Ribeiro EB, do Nascimento CM. High-fat diet and glucocorticoid treatment cause hyperglycemia associated with adiponectin receptor alterations. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chatterjee TK, Stoll LL, Denning GM, Harrelson A, Blomkalns AL, Idelman G, et al. Proinflammatory phenotype of perivascular adipocytes: Influence of high-fat feeding. Circ Res. 2009;104:541–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Folco EJ, Rocha VZ, López-Ilasaca M, Libby P. Adiponectin inhibits pro-inflammatory signaling in human macrophages independent of interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:25569–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ohashi K, Parker JL, Ouchi N, Higuchi A, Vita JA, Gokce N, et al. Adiponectin promotes macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6153–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ceriello A. Oxidative stress and diabetes-associated complications. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(Suppl 1):60–2. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.S1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Melnik BC. Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: An update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:371–88. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S69135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Al-Shobaili HA. Oxidants and anti-oxidants status in acne vulgaris patients with varying severity. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2014;44:202–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gupta M, Mahajan VK, Mehta KS, Chauhan PS. Zinc therapy in dermatology: A review. Dermatol Res Pract 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/709152. 709152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rubin MG, Kim K, Logan AC. Acne vulgaris, mental health and omega-3 fatty acids: A report of cases. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:36. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wollina U, Koch A, Heinig B, Kittner T, Nowak A. Acne inversa (Hidradenitis suppurativa): A review with a focus on pathogenesis and treatment. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:2–11. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.105454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bergler-Czop B, Hadasik K, Brzezinska-Wcislo L. Acne inversa: Difficulties in diagnostics and therapy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:296–301. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.44012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shenefelt PD. Using hypnosis to facilitate resolution of psychogenic excoriations in acne excoriée. Am J Clin Hypn. 2004;46:239–45. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2004.10403603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shenefelt PD. Psychological interventions in the management of common skin conditions. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2010;3:51–63. doi: 10.2147/prbm.s7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Böni R, Nehrhoff B. Treatment of gram-negative folliculitis in patients with acne. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:273–6. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Inayat S, Khurshid K, Inayat M, Pal SS. Comparison of efficacy and tolerability of topical 0.1% adapalene gel with 0.05% isotretinoin gel in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Pak Assoc Dermatologists. 2012;22:240–7. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kircik LH. Tretinoin microsphere gel pump 0.04% versus tazarotene cream 0.05% in the treatment of mild-to-moderate facial acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:650–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pariser D, Colón LE, Johnson LA, Gottschalk RW. Adapalene 0.1% gel compared to tazarotene 0.1% cream in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(6 Suppl):s18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thiboutot DM, Shalita AR, Yamauchi PS, Dawson C, Kerrouche N, Arsonnaud S, et al. Adapalene gel, 0.1%, as maintenance therapy for acne vulgaris: A randomized, controlled, investigator-blind follow-up of a recent combination study. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:597–602. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.5.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Babaeinejad SH, Fouladi RF. The efficacy, safety and tolerability of adapalene versus benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of mild acne vulgaris; a randomized trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:1033–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iftikhar U, Aman S, Nadeem M, Kazmi AH. A comparison of efficacy and safety of topical 0.1% adapalene and 4% benzoyl peroxide in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris. J Pak Assoc Dermatologists. 2009;19:141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tu P, Li GQ, Zhu XJ, Zheng J, Wong WZ. A comparison of adapalene gel 0.1% vs. tretinoin gel 0.025% in the treatment of acne vulgaris in China. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(Suppl 3):31–6. doi: 10.1046/j.0926-9959.2001.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mokhtari F, Faghihi G, Basiri A, Farhadi S, Nilforoushzadeh M, Behfar S. Comparison effect of azithromycin gel 2% with clindamycin gel 1% in patients with acne. Adv Biomed Res. 2016;5:72. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.180641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tunca M, Akar A, Ozmen I, Erbil H. Topical nadifloxacin 1% cream vs. topical erythromycin 4% gel in the treatment of mild to moderate acne. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1440–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bhavsar B, Choksi B, Sanmukhani J, Dogra A, Haq R, Mehta S, et al. Clindamycin 1% Nano-emulsion Gel formulation for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Results of a randomized, active controlled, multicentre, phase IV clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:YC05–9. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9111.4769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jung JY, Kwon HH, Yeom KB, Yoon MY, Suh DH. Clinical and histological evaluation of 1% nadifloxacin cream in the treatment of acne vulgaris in Korean patients. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hajheydari Z, Mahmoudi M, Vahidshahi K, Nozari A. Comparison of efficacy of azithromycin vs. clindamaycin and erythromycin in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Pak J Med Sci. 2011;27:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lamel SA, Sivamani RK, Rahvar M, Maibach HI. Evaluating clinical trial design: Systematic review of randomized vehicle-controlled trials for determining efficacy of benzoyl peroxide topical therapy for acne. Arch Dermatol Res. 2015;307:757–66. doi: 10.1007/s00403-015-1568-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kawashima M, Hashimoto H, Alio Sáenz AB, Ono M, Yamada M. Is benzoyl peroxide 3% topical gel effective and safe in the treatment of acne vulgaris in Japanese patients? A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. J Dermatol. 2014;41:795–801. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shah BJ, Sumathy TK, Dhurat RS, Torsekar RG, Viswanath V, Mukhi JI, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of topical fixed combination of nadifloxacin 1% and adapalene 0.1% in the treatment of mild to moderate acne vulgaris in Indian patients: A multicenter, open-labelled, prospective study. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:385–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Tanghetti E, Dhawan S, Torok H, Kircik L. Tazarotene 0.1 percent cream plus clindamycin 1 percent gel versus tretinoin 0.025 percent gel plus clindamycin 1 percent gel in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ochsendorf F. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025%: A novel fixed-dose combination treatment for acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(Suppl 5):8–13. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Prasad S, Mukhopadhyay A, Kubavat A, Kelkar A, Modi A, Swarnkar B, et al. Efficacy and safety of a nano-emulsion gel formulation of adapalene 0.1% and clindamycin 1% combination in acne vulgaris: A randomized, open label, active-controlled, multicentric, phase IV clinical trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:459–67. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.98077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Green L, Cirigliano M, Gwazdauskas JA, Gonzalez P. The tolerability profile of clindamycin 1%/Benzoyl peroxide 5% gel vs. adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel for facial acne: Results of two randomized, single-blind, split-face studies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:16–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kaur J, Sehgal VK, Gupta AK, Singh SP. A comparative study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of combination topical preparations in acne vulgaris. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;May;5:106–10. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.157155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Choudhury S, Chatterjee S, Sarkar DK, Dutta RN. Efficacy and safety of topical nadifloxacin and benzoyl peroxide versus clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide in acne vulgaris: A randomized controlled trial. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:628–31. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.89815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. An in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263–6. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Özgen ZY, Gürbüz O. A randomized, double-blind comparison of nadifloxacin 1% cream alone and with benzoyl peroxide 5% lotion in the treatment of mild to moderate facial acne vulgaris. Marmara Med J. 2013;26:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jackson JM, Fu JJ, Almekinder JL. A randomized, investigator-blinded trial to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of a benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin phosphate 1% gel compared with a clindamycin phosphate 1.2%/tretinoin 0.025% gel in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:131–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seidler EM, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials using 5% benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin versus 2.5% benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin topical treatments in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e117–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gollnick HP, Friedrich M, Peschen M, Pettker R, Pier A, Streit V, et al. Safety and efficacy of adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% in the long-term treatment of predominantly moderate acne with or without concomitant medication – Results from the non-interventional cohort study ELANG. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(Suppl 4):15–22. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Friedman A, Waite K, Brandt S, Meckfessel MH. Accelerated onset of action and increased tolerability in treating acne with a fixed-dose combination gel. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:231–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sittart JA, Costa Ad, Mulinari-Brenner F, Follador I, Azulay-Abulafia L, Castro LC. Multicenter study for efficacy and safety evaluation of a fixeddose combination gel with adapalen 0.1% and benzoyl peroxide 2.5% (Epiduo® for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Brazilian population. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(6 Suppl 1):1–16. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Stein Gold L, Weiss J, Rueda MJ, Liu H, Tanghetti E. Moderate and severe inflammatory acne vulgaris effectively treated with single-agent therapy by a new fixed-dose combination adapalene 0.3 %/benzoyl peroxide 2.5 % gel: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group, Controlled Study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:293–303. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dreno B, Tan J, Rivier M, Martel P, Bissonnette R. Adapalene 0.1%/benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel reduces the risk of atrophic scar formation in moderate inflammatory acne: A split-face randomized controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:737–742. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kaymak Y, Önder M. An investigation of efficacy of topical niacinamide for the treatment of mild and moderate acne vulgaris. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2008;2:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stein Gold LF, Jarratt MT, Bucko AD, Grekin SK, Berlin JM, Bukhalo M, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily dapsone gel, 7.5% for treatment of adolescents and adults with acne vulgaris:First of two identically designed, large, multicenter, randomized, vehicle-controlled trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:553–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Alexis AF, Burgess C, Callender VD, Herzog JL, Roberts WE, Schweiger ES, et al. The efficacy and safety of topical dapsone gel, 5% for the treatment of acne vulgaris in adult females with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fleischer AB, Jr, Shalita A, Eichenfield LF, Abramovits W, Lucky A, Garrett S Dapsone Gel in Combination Treatment Study Group. Dapsone gel 5% in combination with adapalene gel 0.1%, benzoyl peroxide gel 4% or moisturizer for the treatment of acne vulgaris: A 12-week, randomized, double-blind study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Brar BK, Kumar S, Sethi N. Comparative evaluation of dapsone 5% gel vs. clindamycin 1% gel in mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2016;23:34–9. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Kircik LH. Efficacy and safety of azelaic acid (AzA) gel 15% in the treatment of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and acne: A 16-week, baseline-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:586–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Thielitz A, Lux A, Wiede A, Kropf S, Papakonstantinou E, Gollnick H. A randomized investigator-blind parallel-group study to assess efficacy and safety of azelaic acid 15% gel vs. adapalene 0.1% gel in the treatment and maintenance treatment of female adult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:789–96. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Schachner L, Pestana A, Kittles C. A clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of a topical erythromycin-zinc formulation with a topical clindamycin formulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:489–95. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70069-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Capitanio B, Sinagra JL, Weller RB, Brown C, Berardesca E. Randomized controlled study of a cosmetic treatment for mild acne. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:346–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Abels C, Kaszuba A, Michalak I, Werdier D, Knie U, Kaszuba A. A 10% glycolic acid containing oil-in-water emulsion improves mild acne: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:202–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2011.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wang CM, Huang CL, Hu CT, Chan HL. The effect of glycolic acid on the treatment of acne in Asian skin. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:23–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Atzori L, Brundu MA, Orru A, Biggio P. Glycolic acid peeling in the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;12:119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Erbagci Z, Akçali C. Biweekly serial glycolic acid peels vs. long-term daily use of topical low-strength glycolic acid in the treatment of atrophic acne scars. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:789–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rosario AM, Monteiro R. A comparative study to assess the safety and efficacy of 12% glycolic acid v/s 10% azelaic acid in the treatment of post acne hyperpigmentation. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2015;5:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Dreno B, Katsambas A, Pelfini C, Plantier D, Jancovici E, Ribet V, et al. Combined 0.1% retinaldehyde/6% glycolic acid cream in prophylaxis and treatment of acne scarring. Dermatology. 2007;214:260–7. doi: 10.1159/000099593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:1196–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2003.29384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bae BG, Park CO, Shin H, Lee SH, Lee YS, Lee SJ, et al. Salicylic acid peels versus Jessner's solution for acne vulgaris: A comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:248–53. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Seidler EM, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, benzoyl peroxide with salicylic acid, and combination benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yap FB. Safety and efficacy of fixed-dose 10 mg daily isotretinoin treatment for acne vulgaris in Malaysia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016:1–5. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Rao PK, Bhat RM, Nandakishore B, Dandakeri S, Martis J, Kamath GH. Safety and efficacy of low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of moderate to severe acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:316. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.131455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Hasibur MR, Meraj Z. Combination of low-dose isotretinoin and pulsed oral azithromycin for maximizing efficacy of acne treatment. Mymensingh Med J. 2013;22:42–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Marron SE, Tomas-Aragones L, Boira S. Anxiety, depression, quality of life and patient satisfaction in acne patients treated with oral isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:701–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Lee JW, Yoo KH, Park KY, Han TY, Li K, Seo SJ, et al. Effectiveness of conventional, low-dose and intermittent oral isotretinoin in the treatment of acne: A randomized, controlled comparative study. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1369–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Bhola K. Oral isotretinoin in different dose regimens for acne vulgaris: A randomized comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:688–94. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.86482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Borghi A, Mantovani L, Minghetti S, Giari S, Virgili A, Bettoli V. Low-cumulative dose isotretinoin treatment in mild-to-moderate acne: Efficacy in achieving stable remission. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:1094–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Dhaked DR, Meena RS, Maheshwari A, Agarwal US, Purohit S. A randomized comparative trial of two low-dose oral isotretinoin regimens in moderate to severe acne vulgaris. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:378–385. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.190505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Innocenzi D, Skroza N, Ruggiero A, Concetta Potenza M, Proietti I. Moderate acne vulgaris: Efficacy, tolerance and compliance of oral azithromycin thrice weekly for. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2008;16:13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ullah G, Noor SM, Bhatti Z, Ahmad M, Bangash AR. Comparison of oral azithromycin with oral doxycycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2014;26:64–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Babaeinejad S, Khodaeiani E, Fouladi RF. Comparison of therapeutic effects of oral doxycycline and azithromycin in patients with moderate acne vulgaris: What is the role of age? J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:206–10. doi: 10.3109/09546631003762639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rafiei R, Yaghoobi R. Azithromycin versus tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat. 2006;17:217–21. doi: 10.1080/09546630600866459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Gruber F, Grubisic-Greblo H, Kastelan M, Brajac I, Lenkovic M, Zamolo G. Azithromycin compared with minocycline in the treatment of acne comedonica and papulo-pustulosa. J Chemother. 1998;10:469–73. doi: 10.1179/joc.1998.10.6.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Garner SE, Eady A, Bennett C, Newton JN, Thomas K, Popescu CM. Minocycline for acne vulgaris: Efficacy and safety. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD002086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002086.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Torok HM. Extended-release formulation of minocycline in the treatment of moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris in patients over the age of 12 years. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:19–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Kircik LH. Doxycycline and minocycline for the management of acne: A review of efficacy and safety with emphasis on clinical implications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1407–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Skidmore R, Kovach R, Walker C, Thomas J, Bradshaw M, Leyden J, et al. Effects of subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline in the treatment of moderate acne. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:459–64. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Del Rosso JQ. Oral doxycycline in the management of acne vulgaris: Current perspectives on clinical use and recent findings with a new double-scored small tablet formulation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:19–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Uchida S. Once-daily levofloxacin is effective for inflammatory acne and achieves high levels in the lesions: An open study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:AB17. doi: 10.1159/000063365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kus S, Yucelten D, Aytug A. Comparison of efficacy of azithromycin vs. doxycycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Jaisamrarn U, Chaovisitsaree S, Angsuwathana S, Nerapusee O. A comparison of multiphasic oral contraceptives containing norgestimate or desogestrel in acne treatment: A randomized trial. Contraception. 2014;90:535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Palli MB, Reyes-Habito CM, Lima XT, Kimball AB. A single-center, randomized double-blind, parallel-group study to examine the safety and efficacy of 3mg drospirenone/0.02 mg ethinyl estradiol compared with placebo in the treatment of moderate truncal acne vulgaris. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:633–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Koltun W, Maloney JM, Marr J, Kunz M. Treatment of moderate acne vulgaris using a combined oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol 20 μg plus drospirenone 3mg administered in a 24/4 regimen: A pooled analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Sanam M, Ziba O. Desogestrel ethinylestradiol versus levonorgestrel ethinylestradiol. Which one has better affect on acne, hirsutism, and weight change. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:23–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Adalatkhah H, Pourfarzi F, Sadeghi-Bazargani H. Flutamide versus a cyproterone acetate-ethinyl estradiol combination in moderate acne: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2011;4:117–21. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S20543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Brown J, Farquhar C, Lee O, Toomath R, Jepson RG. Spironolactone versus placebo or in combination with steroids for hirsutism and/or acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD000194. [Google Scholar]