Abstract

Objective

We sought to classify causes of stillbirth for 6 low-middle income countries using a prospectively defined algorithm.

Design

Prospective, observational study

Setting

Communities in India, Pakistan, Guatemala, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia and Kenya

Population

Pregnant women residing in defined study regions.

Methods

Basic data regarding conditions present during pregnancy and delivery were collected. Using these data, a computer-based hierarchal algorithm assigned cause of stillbirth. Causes included birth trauma, congenital anomaly, infection, asphyxia, and preterm birth, based on existing cause of death classifications and included contributing maternal conditions.

Main Outcome Measures

Primary cause of stillbirth.

Results

Of 109,911 women who were enrolled and delivered (99% of those screened in pregnancy), 2,847 had a stillbirth (a rate of 27.2 per 1000 births). Asphyxia was the cause of 46.6% of the stillbirths, followed by infection (20.8%), congenital anomalies (8.4%) and prematurity (6.6%). Among those caused by asphyxia, 38% had prolonged or obstructed labor, 19% antepartum hemorrhage and 18% preeclampsia/eclampsia. About two-thirds (67.4%) of the stillbirths did not have signs of maceration.

Conclusions

Our algorithm determined cause of stillbirth from basic data obtained from lay-health providers. The major cause of stillbirth was fetal asphyxia associated with prolonged or obstructed labor, preeclampsia and antepartum hemorrhage. In the African sites, infection also was an important contributor to stillbirth. Using this algorithm, we documented cause of stillbirth and its trends to inform public health programs, using consistency, transparency, and comparability across time or regions with minimal burden on the healthcare system.

Keywords: stillbirth, low-income countries, cause of death classification system

Introduction

Globally, stillbirth rates remain high in resource-limited settings with few global estimates of cause of stillbirth published [1-3]. Knowing the medical causes of stillbirth is important for development of strategies to reduce stillbirths [4-6]. To date, over 50 stillbirth classification systems have been developed [7-22], most requiring extensive diagnostics and most relevant in high income countries (HIC). Additionally, systems vary in definitions including primary and secondary causes, associated causes, contributing causes, underlying causes, or preventable causes. Few systems have been developed for low-middle income countries (LMIC) where diagnostic tools such as autopsy or placental histology are usually unavailable. Examples of systems include Frøen et al's Cause of Death and Associated Conditions (CODAC) system, which focuses on perinatal death and includes 10 categories [19,20] and Neonatal and Intrauterine deaths Classification according to Etiology (NICE), including 13 causes for perinatal death [22]. However, to date, these systems have only been used in small studies in LMIC and generally do not distinguish between stillbirth and neonatal deaths to characterize etiology [20-24].

Determining cause of stillbirth has historically been challenging, as the fetus is not directly observed when death occurs and the pathway to death is often unclear [5]. Thus, cause has often been defined by maternal or obstetric conditions that may be directly or indirectly associated with the fetal death [25-27] In LMIC, common clinical conditions associated with stillbirth include prolonged and obstructed labor, preeclampsia/eclampsia, multiple births, and abnormal presentations. Most stillbirths associated with these conditions are caused by diminished placental or fetal blood flow and fetal asphyxia is the final common pathway leading to death [25,28] Stillbirths are also classified as macerated or non-macerated stillbirths, with the former generally occurring more than 24 hours before delivery [29]. Non-maceration suggests that the death likely occurred during labor. Recognizing these limitations, the World Health Organization (WHO) has established an international classification of diseases (ICD) perinatal mortality system, which examines the timing of the perinatal death, associated maternal conditions, and cause of perinatal death [30,31]. However, the factors used to determine cause of death vary.

To improve upon existing systems to determine cause of stillbirth in LMIC, we developed a hierarchal classification system, the Global Network Classification System [32] that relies exclusively on readily available clinical data. Our objective for this analysis was to determine cause of stillbirth across sites in six LMICs and to compare these results with current evidence.

Methods

The study was conducted in 7 sites in 6 LMICs (India [2 sites: Nagpur, Belagavi] Pakistan, Guatemala, Democratic Republic of Congo [DRC], Kenya and Zambia). Data were collected as part of the Global Network's Maternal and Newborn Health Registry (MNHR), a population-based registry of all pregnant women residing in designated regions. The MNHR includes pregnancy related data as well as outcomes from consenting women through 6-weeks postpartum [33,34]. Registry Administrators (RA's), who are trained staff (generally nurses or health workers) identified, consented and obtained basic demographic data from pregnant women, obtained the perinatal and maternal outcomes at delivery, with additional follow-up visits conducted at 6-weeks postpartum. For any women who experienced a stillbirth, a cause of stillbirth form was completed by a trained RA to systematically document additional potential risk factors. Methods for the registry and cause of death study are described in detail elsewhere [33]. This analysis used cause of stillbirth data collected from 2014 (start dates varied by study site) through December 31, 2015.

The Stillbirth Classification Algorithm

Stillbirths were defined as deaths in utero occurring at 20 weeks gestation or greater [1]. The definitions for each cause were defined (Table S1) [32]. The algorithm (Figure S1) first determines whether the stillbirth was associated with maternal or fetal trauma (i.e., assault, suicide, accident, fetal trauma); if so, the cause of death is classified as trauma. If no trauma was identified, and there is a major (visible) congenital anomaly, this is defined as the cause of the stillbirth. If neither of these conditions is identified and signs of maternal or fetal infection such as malaria, syphilis or fetal or vaginal odor are present, the stillbirth is classified as due to infection. If none of these are present and any maternal or fetal condition associated with intrauterine asphyxia is present, asphyxia is determined as the cause. Finally, because very preterm fetuses may die due to trauma or asphyxia associated with labor, preterm birth is listed as the cause of death if none of the prior conditions were present and the stillbirth was less than 32 weeks and non-macerated [35]. If none of these conditions were identified, the stillbirth was classified as unknown cause.

Ethics approval

The institutional review boards and ethics committee at the participating study sites and their affiliated U.S. partner institutions and the data coordinating center (RTI International) approved the study. All women provided informed consent to be part of the study.

Results

From 2014-2015, 112,768 pregnant women were screened and of those 111,883 (99.7%) consented and enrolled in the registry. Of these women, 103,409 delivered at ≥20 weeks gestation and were eligible for the stillbirth cause of death study. Deliveries ranged from 19,685 in Pakistan to 10,366 in Zambia (Table 1). Hospital deliveries occurred for 42.8% of births (ranging from 74.7% in Nagpur to 9.7% in DRC), 34.5% occurred at health centers (ranging from 63.3% in DRC to 1.0% in Guatemala) and 22.7% of the deliveries occurred in home settings (ranging from 35.4% in Pakistan to 0.6% in Nagpur). For women delivering a stillbirth, delivery at a hospital was slightly more common at each of the sites compared to all births.

Table 1. MNH Registry Characteristics and Cause of Stillbirth by Site, 2014-20151.

| Africa | L. America | Asia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | DRC | Zambia | Kenya | Guatemala | Pakistan | Belagavi | Nagpur | |

| Deliveries, N | 103,409 | 12,112 | 10,366 | 11,311 | 16,111 | 19,687 | 19,089 | 14,733 |

| Delivery location, N (%) | ||||||||

| Hospital | 44,239 (42.8) | 1,172 (9.7) | 2,455 (23.7) | 2,511 (22.2) | 8,800 (54.6) | 7,292 (37.0) | 11,006 (57.7) | 11,003 (74.7) |

| Clinic | 35,668 (34.5) | 7,671 (63.3) | 6,035 (58.2) | 5,522 (48.8) | 169 (1.0) | 5,426 (27.6) | 7,199 (37.7) | 3,646 (24.7) |

| Home/Other | 23,499 (22.7) | 3,269 (27.0) | 1,876 (18.1) | 3,278 (29.0) | 7,141 (44.3) | 6,967 (35.4) | 884 (4.6) | 84 (0.6) |

| Delivery location for stillbirths, N (%) | ||||||||

| Hospital | 1,439 (50.5) | 118 (24.8) | 51 (35.9) | 101 (38.7) | 187 (57.2) | 375 (43.3) | 372 (80.2) | 235 (75.8) |

| Clinic | 717 (25.2) | 212 (44.5) | 49 (34.5) | 87 (33.3) | 2 (0.6) | 262 (30.2) | 54 (11.6) | 51 (16.5) |

| Home/Other | 691 (24.3) | 146 (30.7) | 42 (29.6) | 73 (28.0) | 138 (42.2) | 230 (26.5) | 38 (8.2) | 24 (7.7) |

| Stillbirths, N (Rate/1000) | 2,847 (27.2) | 476 (38.6) | 142 (13.6) | 261 (22.8) | 327 (20.1) | 867 (43.5) | 464 (24.1) | 310 (20.9) |

| Stillbirths from multiple birth, N (%) | 180 (6.3) | 54 (11.4) | 6 (4.2) | 15 (4.6) | 24 (5.2) | 37 (4.3) | 24 (7.7) | 20 (7.7) |

| Cause of Stillbirth2, % (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Congenital Anomaly | 8.4 (7.3, 9.4) | 3.2 (1.6, 4.7) | 5.2 (1.5, 9.0) | 2.7 (0.7, 4.7) | 12.8 (9.2, 16.5) | 5.2 (3.7, 6.7) | 19.6 (15.9, 23.2) | 10.0 (6.7, 13.3) |

| Infection | 21.3 (19.8, 22.8) | 55.7 (51.2, 60.1) | 17.9 (11.4, 24.4) | 34.7 (28.9, 40.5) | 7.6 (4.8, 10.5) | 17.1 (14.6, 19.6) | 9.3 (6.7, 12.0) | 2.6 (0.8, 4.3) |

| Asphyxia | 46.6 (44.8, 48.5) | 28.2 (24.1, 32.2) | 56.7 (48.3, 65.1) | 47.1 (41.0, 53.2) | 45.3 (39.9, 50.7) | 52.7 (49.4, 56.0) | 46.5 (42.0, 51.1) | 54.8 (49.3, 60.4) |

| Prematurity | 6.6 (5.7, 7.5) | 6.1 (3.9, 8.2) | 3.7 (0.5, 6.9) | 4.2 (1.8, 6.7) | 6.4 (3.8, 9.1) | 4.8 (3.4, 6.3) | 9.8 (7.1, 12.5) | 11.0 (7.5, 14.4) |

| Unknown | 17.1 (15.7, 18.5) | 6.9 (4.7, 9.2) | 16.4 (10.1, 22.7) | 11.2 (7.4, 15.0) | 27.8 (23.0, 32.7) | 20.2 (17.5, 22.9) | 14.8 (11.5, 18.0) | 21.6 (17.0, 26.2) |

Study start date in 2014 varied by site

14 stillbirths did not have a cause of death recorded.

From 2014 to 2015, the study included 2,847 stillbirths. The stillbirth rate was 27.2 per 1,000 births, ranging from 43.5 per 1,000 in the Pakistan site to 13.6 per 1,000 in the Zambia site. During that period, the overall stillbirth rates declined about 10%, from 28.7 to 26.2 per 1000 births, in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Overall, 6.6% of stillbirths were multiple gestations, ranging from more than 11% in the DRC site to approximately 4% in the Kenya, Zambia and Pakistan sites.

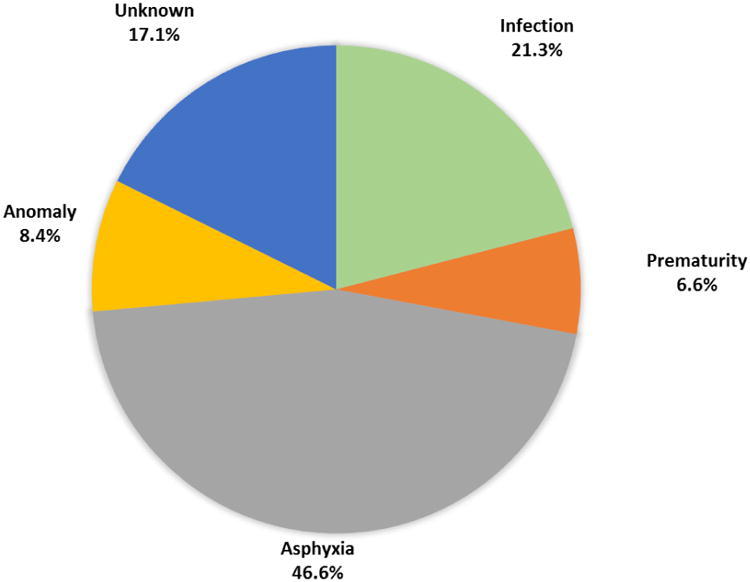

Across all sites, 46.6% of stillbirths were attributed to asphyxia, 21.3% to infection, 8.4% to congenital anomalies and 6.6% to prematurity (Figure 1). No cause was assigned in 17.1% of stillbirths. No stillbirths were attributed to maternal trauma or accident. The cause of stillbirth varied by site, although for the most part, the proportion of stillbirths attributed to each cause was relatively similar with a few notable exceptions (Table 1). Asphyxia was identified as the cause of stillbirth for 56.7% of stillbirths in Zambia compared to 28.2% in DRC. Infection had the greatest variation in the proportion of stillbirths and was estimated as a cause of stillbirth from 55.7% of stillbirths in DRC to 2.6% in Nagpur, India. Congenital anomalies were identified as the primary cause for 19.6% of stillbirths in Belagavi, India to 5% or less in the African sites. Finally, prematurity was considered the cause of stillbirth for about 10% in both India sites but 4% or less in the Zambian and Kenyan sites.

Figure 1. Cause of stillbirth as determined by algorithm among all Global Network sites, 2014-2015.

We next examined the presence of several maternal conditions by cause of stillbirth (Table 2). Of the 2,883 women with a stillbirth, 1,400 (48.8%) had one or more of the maternal antepartum conditions including preeclampsia/eclampsia (10.1%), antepartum hemorrhage (11.6%), prolonged or obstructed labor (21.9%), abnormal lie (10.2%), and maternal infection (9.4%). When preeclampsia/eclampsia, antepartum hemorrhage or prolonged or obstructed labor were present, about 80% of the stillbirths were classified as having asphyxia as the cause of death. Of the stillbirths with breech or abnormal lie, 62.8% were classified as having asphyxia as the cause of death. Of those stillbirths where there was evidence of maternal infection, 83.6% were classified as the death due to infection. Among those stillbirths classified as asphyxia-related deaths, 38.0% had obstructed or prolonged labor, 19.2% had antepartum hemorrhage and 18.4% had preeclampsia/eclampsia (Figure S2). Among those with asphyxia-attributed stillbirth, 23% had no maternal condition identified but did have a fetal condition such as fetal distress or cord prolapse.

Table 2. Cause of Stillbirth by Maternal Conditions.

| Maternal Condition Present | None of the Specified Conditions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia/Eclampsia | Antepartum Hemorrhage | Obstructed or Prolonged Labor | Breech or Transverse Lie | Maternal Infection | ||

| Stillbirths, N | 293 | 337 | 630 | 296 | 268 | 1,433 |

| Cause of Stillbirth by Algorithm, N (%) | ||||||

| Congenital Anomaly | 12 (4.1) | 8 (2.4) | 17 (2.7) | 15 (5.1) | 10 (3.7) | 187 (13.0) |

| Infection | 36 (12.3) | 73 (21.7) | 109 (17.3) | 49 (16.6) | 224 (83.6) | 261 (18.2) |

| Asphyxia | 243 (82.9) | 254 (75.4) | 502 (79.7) | 186 (62.8) | 34 (12.7) | 364 (25.4) |

| Prematurity | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 177 (12.4) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 37 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 444 (31.0) |

Finally, we examined the cause of stillbirth versus the presence or absence of signs of maceration (Table 3). Among all stillbirths, 67.8% did not have signs of maceration, with the death likely to have occurred less than 12 to 24 hours prior to delivery. There were important differences in the cause of death between macerated and non-macerated stillbirths. If the fetus was macerated, the cause of stillbirth was nearly equally divided among infection, asphyxia and unknown, with a smaller proportion due to a congenital anomaly (10.8%). If the fetus was not macerated, the majority of deaths were caused by asphyxia (55.4%) with smaller percentages due to infection (16.1%), unknown (11.8%), prematurity (9.7%) and congenital anomalies (7.2%). Thus, macerated stillbirths were more likely due to infection or having an unknown cause while among those not macerated, asphyxia was the most common cause. Among those classified as asphyxia-related stillbirths, 80.5% were non-macerated, while among those with infection, 31.3% were macerated.

Table 3. Cause of Stillbirth by Signs of Maceration.

| Signs of Maceration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Macerated | Non-Macerated | Unknown | |

| Stillbirths, N (%) | 891 | 1,920 | 22 |

| Cause of Stillbirth by Algorithm, N (%) | |||

| Congenital Anomaly | 96 (10.8) | 138 (7.2) | 3 (1.2) |

| Infection | 288 (32.3) | 310 (16.1) | 5 (22.7) |

| Asphyxia | 250 (28.1) | 1,063 (55.4) | 8 (0.6) |

| Prematurity | 0 (0.0) | 187 (9.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unknown | 266 (30.1) | 227 (11.8) | 6 (1.2) |

Discussion

Main findings

The overall stillbirth rate of 27.2 per 1,000 is similar to those reported for LIC and somewhat higher than the estimated world average of about 20 per 1000 births [1]. The Pakistan site recorded the highest rate (43.5 per 1000) followed by the DRC site (38.6 per 1000) and Kenya (22.8 per 1000), also similar to the regional stillbirth patterns reported [1].

Classifying stillbirths by maceration status and by cause of death provides some interesting observations and potential validation for the system. The fact that most deaths classified as asphyxia-related were non-macerated, suggests that they occurred during labor, consistent with many observations about intrapartum deaths [22]. Our system classified macerated stillbirths more commonly as infection-related or of unknown etiology which also appears consistent with previous reports [3,29]. In this analysis, all stillbirths classified as preterm in origin were non-macerated, suggesting that they mostly occurred in labor and were due to the fetus not being able to tolerate the preterm labor [35].

Using this system, we found the major cause of stillbirth to be asphyxia (46.6%), with infections contributing to 21%. Congenital anomalies represented 8.4% of all causes, with Belagavi, India with nearly 20% having a substantially higher proportion due to congenital anomalies. A prior study conducted at this site in India found 24% of pregnant women were in consanguineous partnerships, which is a high risk for birth defects [36]. Finally, in this study, prematurity was responsible for nearly 7% of all stillbirths.

However, we also observed important regional differences. Infection was the leading cause of stillbirths in the DRC site (55.7%), one-third of the stillbirths in western Kenya and 17.9% in Zambia. Thus, the top 3 sites with the largest percent of infection-related stillbirths were all in sub-Saharan Africa. Congenital anomalies represented a higher proportion of the stillbirths in the Indian sites and Guatemala relative to the sites in Africa.

Asphyxia appeared to cause a substantial proportion of stillbirths across all sites. Among those with asphyxia as a cause of stillbirth, obstructed or prolonged labor was present among 38%, antepartum hemorrhage was present for 19% and preeclampsia or eclampsia were present among 18% of those with stillbirth. About one-fourth of the stillbirths attributed to asphyxia had no specific maternal condition identified but did have a fetal condition such as cord prolapse or fetal distress identified. Seventeen percent of stillbirths had no attributable cause identified using the algorithm.

Strengths and limitations

There are a number of weaknesses and strengths associated with the Global Network Stillbirth Classification System and its use in this study. Most important, the cause of stillbirth attributed in this system has not been validated with fetal autopsy, culture or other more sophisticated techniques, as the gold standard [15,37]. To address this gap, future analyses are planned to validate the Global Network system with other sources, especially where autopsy and other sophisticated testing are available to confirm cause of stillbirths [15]. Also, because in these settings, fetal monitoring is generally not performed, we do not attempt to quantify the number of stillbirths associated with fetal distress, which is a common consideration in many stillbirths. We also recognize that this system is necessarily a simplification and as a result, subtle or rare causes of stillbirth may be missed.

For a few of the categories, among the sites, there are also fairly large differences in the percent of stillbirths attributed to various causes which may be a result of site ascertainment differences due to a number of factors. For example, infection as a cause of death may be especially variable among sites with different access to tests and laboratory capabilities varying by study site. Thus, the extent to which the differences in reported infection reflect local health facility access and capability is also unknown. This system also omits categorizing social or other factors that may contribute to stillbirth in low-resource settings. However, within these limitations, the major causes of stillbirth related to pregnancy appeared to be generally consistent with other external sources of cause of death data.

The strengths of our methodology are consistency, transparency, and comparability across time or regions. The methodology places little additional burden on the healthcare system. This system uses minimal, basic data from the mother, family or lay-health providers without reliance on laboratory tests, placental examinations or autopsies to determine cause of stillbirth using well-established categories. Because we use these data to assign cause of stillbirth by an algorithm, potential sources of inconsistency and bias from clinician or lay coders are reduced. In addition, using this system, we identified the maternal conditions that also were present among women having a stillbirth. Finally, the Global Network system uses principles that are consistent with the WHO's development of the perinatal mortality classification system [30].

Interpretation

To date, only a relatively small number of stillbirth cause of death studies using a variety of classification systems have been completed in LMIC. For example, a study in India using CODAC to classify 87 stillbirths found that prolonged labor, hypertension in pregnancy and congenital anomalies were the main causes of stillbirth. In that study, nearly half of all stillbirths were intrapartum [20]. In Tanzania, a ten-year study of nearly 2,000 perinatal deaths (including 1,219 stillbirths) used the NICE classification and also found that obstructed/prolonged labor and hypertension were the leading maternal conditions associated with perinatal death [22]. About one-fifth of the deaths occurred among women referred to the health facility for an obstetric or medical complication.

Allanson et al completed a recent study of cause of perinatal mortality (n=687) in South Africa [24]. They noted, similar to our study, a high rate of intrapartum deaths (non-macerated stillbirths) and similar to other studies, found that hemorrhage and hypertension were the main maternal conditions identified among stillbirths. However, as we found, a substantial proportion of all stillbirths – nearly half - occurred among women with no apparent obstetric complication.

The concept of ‘preventable stillbirths’ has been highlighted in the recent Lancet stillbirth series [2]. Similar to our study, the group estimated that only 7.4% of stillbirths are associated with congenital anomalies and that the majority of stillbirths, especially in LMIC's are preventable with appropriate care. Our study confirms this opinion as we found that most stillbirths were not macerated, and were associated with obstetric conditions that if treated appropriately would prevent the stillbirth.

Conclusions

In summary, when using this system to classify causes of stillbirth, we found asphyxia as the most common cause. These stillbirths were associated with a number of major obstetric conditions, including obstructed and prolonged labor and preeclampsia/eclampsia. However, nearly half of all stillbirths were not associated with an identifiable maternal condition. In addition, the majority of stillbirths lacked signs of maceration and likely occurred during labor, and thus many of the stillbirths should be preventable with appropriate obstetric labor and delivery care. Our study reinforces the importance of a system to classify cause of stillbirth that is reliable across low-resource settings to inform effective interventions in order to ultimately reduce preventable stillbirths.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The MNH Study Investigators oversaw implementation of the study at participating sites. Alan H. Jobe, Chairman of the Global Network, participated in review of the study.

Funding: The study was funded through grants from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U01U01 HD040477; U01 HD043464; U01 HD040657; U01 HD042372; U01 HD040607; U01 HD058322; U01 HD058326; U01 HD040636)

Footnotes

Disclosures of interests: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. The ICMJE disclosure forms are available as online supporting information.

Contributions to authorship: EMM, ALG, CLB, WAC, and RLG designed the algorithm; SS, FE, SSG, EC, MM, OP, AT, AP, SMD, CT, IM, SS(2) oversaw study implementation and with MB, BSK, WAC, RJF, PLH, EAL, KMH, NFK, MKT, MM(2) and RLG monitored quality of data collection. JLM, DDW performed analyses with EMM. EMM and RLG wrote the first draft of the paper and all authors reviewed subsequent drafts and approved the final version of the paper.

Ethical approvals: The ethics review committee of all participating institutions reviewed and approved the study.

References

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(2):e98–e108. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, Amouzou A, Mathers C, Hogan D, et al. Lancet Ending Preventable Stillbirths Series study group; Lancet Stillbirth Epidemiology investigator group. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):587–603. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClure EM, Saleem S, Goudar SS, Moore JL, Garces A, Esamai F, et al. Stillbirth rates in low-middle income countries 2010 - 2013: a population-based, multi-country study from the Global Network. Reprod Health. 2015;12(2):S7. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S2-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frøen JF, Friberg IK, Lawn JE, Bhutta ZA, Pattinson RC, Allanson ER, et al. Lancet Ending Preventable Stillbirths Series study group. Stillbirths: progress and unfinished business. Lancet. 2016;387(10018):574–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00818-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg RL, Saleem S, Pasha O, Harrison MS, Mcclure EM. Reducing stillbirths in low-income countries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95(2):135–43. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frøen JF, Gordijn SJ, Abdel-Aleem H, Bergsjø P, Betran A, Duke CW, et al. Making stillbirths count, making numbers talk - issues in data collection for stillbirths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flenady V, Frøen JF, Pinar H, Torabi R, Saastad E, Guyon G, et al. An evaluation of classification systems for stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edmond KM, Quigley MA, Zandoh C, Danso S, Hurt C, Owusu Agyei S, Kirkwood BR. Aetiology of stillbirths and neonatal deaths in rural Ghana: implications for health programming in developing countries. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22(5):430–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agampodi S, Wickramage K, Agampodi T, Thennakoon U, Jayathilaka N, Karunarathna D, Alagiyawanna S. Maternal mortality revisited: the application of the new ICD-MM classification system in reference to maternal deaths in Sri Lanka. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ego A, Zeitlin J, Batailler P, Cornec S, Fondeur A, Baran-Marszak M, et al. Stillbirth classification in population-based data and role of fetal growth restriction: the example of RECODE. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korteweg FJ, Gordijn SJ, Timmer A, Holm JP, Ravisé JM, Erwich JJ. A placental cause of intrauterine fetal death depends on the perinatal mortality classification system used. Placenta. 2008;29(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Measey M, Charles A, d'Espaignet E, Harrison C, Douglass C. Aetiology of stillbirth: unexplored is not unexplained. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2007;31:5. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2007.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardosi J, Kady SM, McGeown P, Francis A, Tonks A. Classification of stillbirth by relevant condition at death (ReCoDe): population based cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331(7525):1113–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38629.587639.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CESDI – Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy: 8th Annual Report. London: Maternal and Child Health Research Consortium; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudley DJ, Goldenberg R, Conway D, Silver RM, Saade GR, Varner MW, et al. Stillbirth Research Collaborative Network. A new system for determining the causes of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 Pt 1):254–260. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e7d975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy UM, Goldenberg R, Silver R, Smith GC, Pauli RM, Wapner RJ, et al. Stillbirth classification--developing an international consensus for research: executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(4):901–14. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f6e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan A, King JF, Flenady V, Haslam RH, Tudehope DI. Classification of perinatal deaths: development of the Australian and New Zealand classifications. J Paediatr Child Health. 2004;40(7):340–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Committee on Genetics. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 383: Evaluation of stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):963–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263934.51252.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frøen JF, Pinar H, Flenady V, Bahrin S, Charles A, Chauke L, et al. Causes of death and associated conditions (Codac): a utilitarian approach to the classification of perinatal deaths. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaistha M, Kumar D, Bhardwaj A. Agreement between international classification of disease (ICD) and cause of death and associated conditions (CODAC) for the ascertainment of cause of stillbirth (SB) in the rural areas of north India. Indian J Public Health. 2016;16:73–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.177348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mmbaga BT, Lie RT, Olomi R, Mahande MJ, Olola O, Daltveit AK. Causes of perinatal death at a tertiary care hospital in Northern Tanzania 2000-2010: a registry based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winbo IG, Serenius FH, Dahlquist GG, Källén BA. NICE, a new cause of death classification for stillbirths and neonatal deaths. Neonatal and Intrauterine Death Classification according to Etiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27(3):499–504. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lori JR, Rominski S, Osher BF, Boyd CJ. A case series study of perinatal deaths at one referral center in rural post-conflict Liberia. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1232-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allanson ER, Muller M, Pattinson RC. Causes of perinatal mortality and associated maternal complications in a South African province: challenges in predicting poor outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0472-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldenberg RL, Harrison M, McClure EM. Stillbirth: The Hidden Birth Asphyxia – U.S. and Global Perspectives. Clin Perinatol. 2016;43(3):439–53. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aminu M, Unkels R, Mdegela M, Utz B, Adaji S, van den Broek N. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG. 2014;121(4):141–53. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nausheen S, Soofi SB, Sadiq K, Habib A, Turab A, Memon Z, et al. Validation of verbal autopsy tool for ascertaining the causes of stillbirth. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawn JE, Lee AC, Kinney M, Sibley L, Carlo WA, Paul VK, et al. Two million intrapartum-related stillbirths and neonatal deaths: where, why, and what can be done? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;107(1):S5–18. S19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kc A, Nelin V, Wrammert J, Ewald U, Vitrakoti R, Baral GN, Målqvist M. Risk factors for antepartum stillbirth: a case-control study in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:146. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0567-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allanson ER, Tunçalp O, Gardosi J, Pattinson RC, Erwich JJ, Flenady VJ, et al. Classifying the causes of perinatal death Bulletin WHO. 2016;94:79–79A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.168047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allanson ER, Tunçalp Ö, Gardosi J, Pattinson RC, Francis A, Vogel JP, et al. BJOG. 2016. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during the perinatal period (ICD-PM): results from pilot database testing in South Africa and United Kingdom. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McClure EM, Bose CL, Garces A, Esamai F, Goudar SS, Patel A, et al. Global network for women's and children's health research: a system for low-resource areas to determine probable causes of stillbirth, neonatal, and maternal death. Maternal Health, Neonatology and Perinatology. 2015;1:11. doi: 10.1186/s40748-015-0012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bose CL, Bauserman M, Goldenberg RL, Goudar SS, McClure EM, Pasha O, et al. The Global Network Maternal Newborn Health Registry: a multi-national, community-based registry of pregnancy outcomes. Reprod Health. 2015;12(2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-12-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goudar S, Carlo WA, McClure EM, Pasha O, Patel A, Esamai F, et al. Maternal Newborn Health Registry of the Global Network for Women's and Children's Health Research. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;118(3):190–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawn JE, Gravett MG, Nunes TM, Rubens CE, Stanton C GAPPS Review Group. Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (1 of 7): definitions, description of the burden and opportunities to improve data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellad MB, Goudar SS, Edlavitch SA, Mahantshetti NS, Naik V, Hemingway-Foday J, et al. Consanguinity, prematurity, birth weight and pregnancy loss: a prospective cohort study at four primary health center areas of Karnataka, India. J Perinatology. 2011:1–7. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korteweg FJ, Erwich JJ, Timmer A, van der Meer J, Ravisé JM, Veeger NJ, Holm JP. Evaluation of 1025 fetal deaths: proposed diagnostic workup. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(1):53.e1–53.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.