Abstract

The modification of DNA bases is a classic hallmark of epigenetics. Four forms of modified cytosine—5-methylcytosine, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxylcytosine—have been discovered in eukaryotic DNA. In addition to cytosine carbon-5 modifications, cytosine and adenine methylated in the exocyclic amine—N4-methylcytosine and N6-methyladenine—are other modified DNA bases discovered even earlier. Each modified base can be considered a distinct epigenetic signal with broader biological implications beyond simple chemical changes. Since 1994, crystal structures of proteins and enzymes involved in writing, reading, and erasing modified bases have become available. Here, we present a structural synopsis of writers, readers, and erasers of the modified bases from prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Despite significant differences in structures and functions, they are remarkably similar regarding their engagement in flipping a target base/nucleotide within DNA for specific recognitions and/or reactions. We thus highlight base flipping as a common structural framework broadly applied by distinct classes of proteins and enzymes across phyla for epigenetic regulations of DNA.

1 Introduction

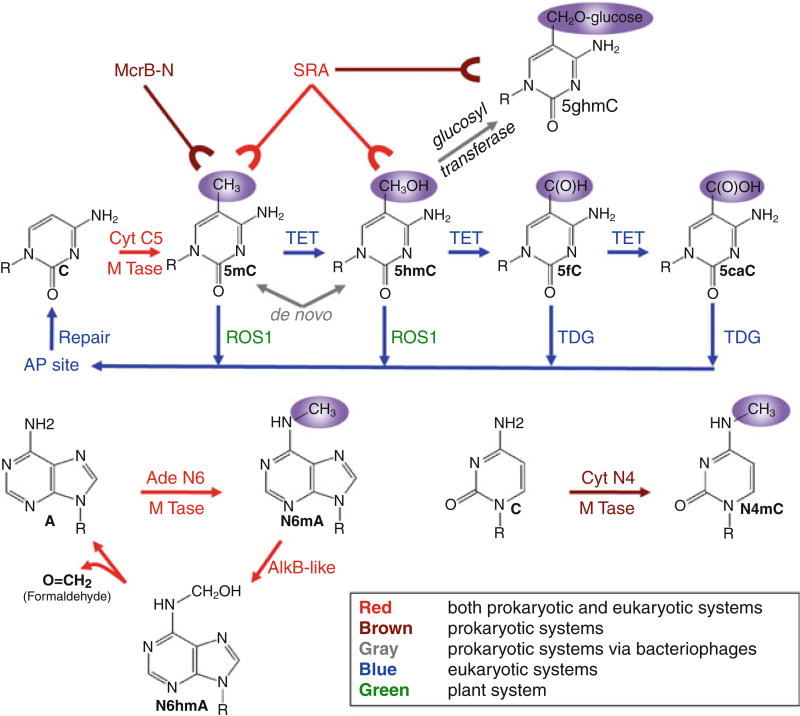

Chemical modifications of DNA bases (Fig. 1) have fundamental biological roles in virtually every living organism. In both prokaryotes and many eukaryotes, cytosine can be methylated at the carbon-5 (C5) position by cytosine-C5 methyltransferases (MTases) to generate 5-methylcytosine (5mC) (Goll and Bestor 2005; Kumar et al. 1994). In higher eukaryotes, 5mC dioxygenases ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes utilize α-ketoglutarate (αKG) and Fe(II) to oxidize the methyl group of 5mC to generate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC) via discrete reactions (Ito et al. 2011; Kriaucionis and Heintz 2009; Tahiliani et al. 2009). In prokaryotes, 5mC and 5hmC can be introduced de novo into the genome during phage invasions, as both modified bases can be synthesized prior to incorporation into the phage genome during DNA synthesis (Warren 1980). After DNA synthesis, phage glucosyltransferases can modify 5hmC within the genome to generate glucosylated 5hmC (Kornberg et al. 1961; Lehman and Pratt 1960). Beyond cytosine-C5 modifications, exocyclic amine groups of cytosine and adenine can be methylated in prokaryotes to generate N4-methylcytosine (N4mC) and N6-methyladenine (N6mA) (Cheng 1995; Jeltsch 2002). Crystal structures of DNA modification enzymes to date have consistently shown that the target nucleotide is flipped out of the double helix for reactions in a process called base flipping.

Fig. 1.

Chemical modifications of DNA. (a) Cytosine-C5 modifications: enzymes and proteins involved in writing, reading, and erasing the modifications via base-flipping mechanisms. (b) Adenine-N6 methylation: enzymes involved in writing and erasing DNA adenine N6 methylation. (c) Cytosine-N4 methylation

In addition to the modification writers, modified base readers have also been shown to flip the target base for recognitions. Mammalian and plant SET- and RING-associated (SRA) domains recognize 5mC within the genome by base flipping (Arita et al. 2008; Avvakumov et al. 2008; Hashimoto et al. 2008; Rajakumara et al. 2011) and have been characterized as nonenzymatic base flippers. Since the first discovery in eukaryotes, SRA domains have been rediscovered in prokaryotes, recognizing 5mC, 5hmC, and/or 5ghmC to coordinate restriction activity in a modification-dependent manner (Horton et al. 2012, 2014a, b, c). In addition to SRA, the bacterial modified cytosine restriction B enzyme also flips 5mC for recognitions but is structurally distinct from other known base flippers (Sukackaite et al. 2012). Structural homologs of McrB across different phyla may recognize modified bases in a similar way.

A brief survey of DNA base modifications in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes reveals that two major families of enzymes, methyltransferases and dioxygenases, are involved in writing DNA modifications in the four forms of modified cytosine: 5mC, 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC. In plants, the 5mC DNA glycosylase repressor of silencing 1 (ROS1) can excise 5mC and 5hmC (in vitro) (Gong et al. 2002; Jang et al. 2014; Hong et al. 2014), and in mammals, thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) can excise 5fC and 5caC (He et al. 2011; Maiti and Drohat 2011; Zhang et al. 2012; Hashimoto et al. 2012a). These discoveries effectively link the base excision repair pathway to DNA demethylation/demodification, by which epigenetic signals encoded in the modified cytosines can be reversed. DNA glycosylases represent the most structurally diverse family of enzymes that are involved in base flipping (also known as nucleotide flipping) (Brooks et al. 2013). Thus, base flipping is not restricted to writers and readers, but has been adopted by DNA glycosylases for erasing DNA modifications as well. Together, structural characterizations of writers, readers, and erasers of DNA base modifications in prokaryotes and eukaryotes effectively showcase base flipping as a general mechanism for regulating and translating fundamental epigenetic signals.

2 Base Flipping for Methylation of DNA Bases

2.1 Bacterial DNMTs (HhaI, TaqI, PvuII)

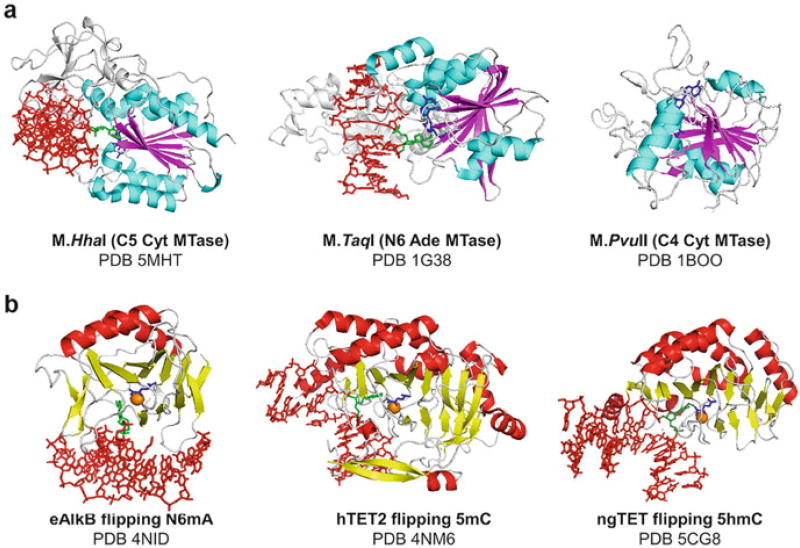

Biological methylation is widely engaged in various regulations, and it uses S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) as the primary methyl group donor. The methyl group of AdoMet is bound to a positively charged sulfur atom predisposed to a nucleophilic attack. During the methylation reaction, AdoMet loses the methyl group and becomes S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy). A number of different families of methyltransferases use AdoMet as cofactor, targeting diverse substrates ranging from small molecules to large macromolecules such as DNA, RNA, proteins, lipid, and polysaccharides. The atoms subjected to methylation also vary, including carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), sulfur (S), and several metals. AdoMet-dependent DNA methyltransferases were first discovered in bacterial restriction-modification systems (Roberts et al. 2015). The known structures of AdoMet-dependent DNA methyltransferases share a common “MTase fold” characterized by mixed seven-stranded β sheets (6↓ 7↑ 5↓ 4↓ 1↓ 2↓ 3↓) in which strand 7 is inserted between strands 5 and 6 antiparallel to the others (Cheng and Roberts 2001) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Writers of DNA modifications. (a) Prokaryotic DNA methyltransferases involved in three different types of DNA methylation have similar structures. DNA is colored in red, and AdoMet/AdoHcy is colored in blue. Flipped bases are shown in green. (b) E. coli AlkB and eukaryotic TET are dioxygenases with common structural folds. αKG is colored in blue, and metal in the active sites is colored in orange

M.HhaI was the first DNA methyltransferase to be structurally characterized (Cheng et al. 1993). It contains an N-terminal MTase domain and a C-terminal target recognition domain (TRD) (Cheng 1995). M.HhaI is a cytosine-C5 methyltransferase that methylates the first cytosine within 5′-GCGC-3′ recognition sequences and prevents R.HhaI restriction activity at the site (Roberts et al. 1976, 2015). Before the structure was available, the proposed mechanism predicted that the catalytic Cys81 would make a nucleophilic attack on the C6 of cytosine to form a covalent complex, followed by transferring the methyl group from AdoMet to cytosine-C5 and releasing the covalent intermediate (Wu and Santi 1985, 1987). In 1994, the crystal structure of M.HhaI-DNA complex with AdoMet was solved as a trapped covalent enzyme-DNA intermediate using 5-fluorocytosine and directly supported the proposed mechanism, presenting the catalytic cysteine covalently linked to C6 and showing methylated C5 adjacent to AdoHcy (Klimasauskas et al. 1994). Yet the most striking aspect of the structure was that both the MTase and the TRD of the enzyme work simultaneously to bind DNA and flip the target base into the active site pocket. The mechanism of DNA base access by base flipping has since been described as the framework for other DNA methyltransferases (Cheng and Roberts 2001).

After the first structure of M.HhaI-DNA complex was solved, many crystal structures of DNA methyltransferase-DNA complexes have been solved. Besides cytosine-C5 methylation, adenine exocyclic N6 methylation is also a critical modification in prokaryotic DNA (Fig. 1b) and in eukaryotic RNA (Low et al. 2001; Hattman 2005; Jia et al. 2013; Niu et al. 2013). Recent studies have also shown that Drosophila genome also harbors N6mA in DNA (Zhang et al. 2015). The structure of the adenine-N6 methyltransferase M.TaqI in complex with DNA and a nonreactive AdoMet analog was solved in 2001 (Goedecke et al. 2001). The enzyme methylates adenine within 5′-TCGA-3′ sequence and harbors a similar two-domain organization as M.HhaI, with the conserved N-terminal MTase domain, but a quite distinct C-terminal TRD (Cheng 1995; Goedecke et al. 2001). The ternary structure is remarkably reminiscent of M.HhaI, involving a flipped adenine in the active site, where the methyl group from the AdoMet analog is positioned near the N6 of the flipped adenine. Instead of the catalytic cysteine residue as in M.HhaI, the asparagine 105 side chain and the following proline backbone oxygen make hydrogen bonds with the adenine-N6 amine group, potentially modulating the direct transfer of the methyl group from AdoMet. A similar mode of interaction is also seen in the active site of the T4 phage DNA adenine methyltransferase (T4 Dam) that flips adenine in 5′-GATC-3′ sequence, and an aspartate residue (Asp171) contacts the adenine-N6 (Horton et al. 2005). Besides adenine-N6 methylation, cytosine-N4 methylation is another type of DNA methylation (Fig. 1c). For example, M.PvuII methylates the central cytosine within 5′-CAGCTG-3′ in the exocyclic amine (Blumenthal et al. 1985; Bheemanaik et al. 2006). The structure of M.PvuII is available only in an AdoMet-bound form without DNA, yet it contains many shared features of other methyltransferases in terms of domain organization and AdoMet interactions (Gong et al. 1997; Bheemanaik et al. 2006).

2.2 Mammalian DNMTs (DNMT1, DNMT3A/3L)

Structural features of classic prokaryotic methyltransferases are extensively shared by the mammalian DNA methyltransferases DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B. They are all cytosine-C5 methyltransferases containing an MTase domain with a catalytic cysteine and a TRD. DNMT1 is primarily implicated in methylation of the daughter strand during DNA replication to maintain the methylation pattern encoded in the mother strand by preferentially recognizing hemi-methylated DNA in CpG dinucleotide context (Li et al. 1992; Yoder et al. 1997). On the other hand, DNMT3A and DNMT3B are considered de novo methyltransferases that can methylate CpG sites as well as non-CpG sites (Ramsahoye et al. 2000; Gowher and Jeltsch 2001; Suetake et al. 2003). Such differences in substrate specificities are partly due to the involvement of other domains outside the catalytic fragment. For example, a CXXC domain and a BAH1 domain within DNMT1 hinder methylation of unmethylated CpG sites (Song et al. 2011), whereas DNMT3A and DNMT3B do not contain such domains and can readily methylate them.

2.3 Implications of DNA Methyltransferase Dimers (DNMT3A/3L and EcoP15I)

Besides being a catalytic domain, the MTase domain can participate in protein-protein interactions as exemplified by the DNMT3A MTase domain interacting with a naturally inactive MTase-like domain of DNMT3L, a scaffold protein that binds histone tail H3 to guide DNMT3A activities by forming a tetramer of 3L-3A-3A-3L (Jia et al. 2007; Ooi et al. 2007). Interestingly, a multi-subunit prokaryotic DNA N6mA methyltransferase, EcoP15I, contains a DNA MTase dimer in which one monomer is involved in target base flipping and the other in the recognition of DNA base context (Gupta et al. 2015). Thus, dimerization of two structurally comparable proteins for divergent functionalities may be a mechanism for fine-controlling genomic DNA modifications.

2.4 Plant DNMTs

Plant DNA MTases show similar functionalities as the mammalian counterparts. Met1 is homologous to mammalian DNMT1 and is responsible for the maintenance of CpG methylation, whereas domain rearranged methyltransferase 2 (DRM2) is involved in de novo DNA methylation (Goll and Bestor 2005; Law and Jacobsen 2010). DRM2 contains a rearranged MTase domain, such that its N-terminal half is equivalent to the C-terminal half of the conventional MTase fold and vice versa. A structural study of DRM2 family MTase domain has revealed that the rearranged domain still forms a classic MTase structure and functions as a homodimer (Zhong et al. 2014) analogous to DNMT3A-3L heterodimer. In addition to Met1 and DRM2, plants also have plant-specific DNA methyltransferases, such as CMT2 and CMT3 that are specifically involved in non-CpG methylation (Stroud et al. 2014; Lindroth et al. 2001; Zemach et al. 2013). The higher diversity of the MTase family within plants compared to the mammalian family suggests that DNA methylation may be more dynamically regulated in plants than in mammals.

3 Base Flipping in Oxidative Modifications of Methylated Bases

3.1 Eukaryotic TET Enzymes

The 5mC is by far the most widely studied modified base. Yet, if 5mC has been considered “the fifth” base, 5hmC is increasingly being labeled as “the sixth” base and has garnered much attention recently. The existence of 5hmC in bacteriophage, modified from 2′-deoxycytidine before the integration into the viral genome (Warren 1980), was first reported in 1953 (Wyatt and Cohen 1953). In 1993, a novel J base (β-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil) was discovered in trypanosomes, in which J-binding proteins (JBP1 and JBP2) are involved in oxidizing the C5-methyl group of thymine during J-base synthesis by using αKG and Fe(II) as cofactors to generate 5-hydroxymethyluracil (Gommers-Ampt et al. 1993; Borst and Sabatini 2008). In 2009, mammalian JBP homolog TET enzymes were discovered to oxidize the methyl group of 5mC to generate 5hmC (Tahiliani et al. 2009; Kriaucionis and Heintz 2009). Further analysis revealed that TET enzymes could further oxidize 5hmC to 5fC and then to 5caC (Ito et al. 2011). Also, TET enzymes have been shown to convert thymine (5-methyluracil) to 5-hydroxymethyluracil by oxidizing the C5-methyl group of thymine (Pfaffeneder et al. 2014; Pais et al. 2015).

Eukaryotic JBP/TET homologs are present across many eukaryotic organisms including amoeboflagellate Naegleria gruberi (Iyer et al. 2013; Hashimoto et al. 2014b). Crystal structures of Naegleria gruberi TET-like (NgTET) and human TET2 (hTET2) in complex with 5mC-, 5hmC-, and 5fC-containing DNA have been characterized (Hashimoto et al. 2014b, 2015a; Hu et al. 2013a, 2015). All TET structures show a flipped base positioned in the active site pocket close to N-oxalylglycine (NOG)—an inactive αKG analog—and a divalent metal such as Fe(II) or Mn(II) used for stalling the enzyme in the pre-reaction state. Some of the features of flipped base recognitions observed in DNMT-DNA complex structures (Cheng and Roberts 2001; Horton et al. 2005) can also be seen in the structures of TET-DNA complexes. The flipped base in the active site of a TET enzyme in complex with DNA is stabilized by π stacking interactions involving an aromatic residue such as Phe295 in NgTET (Hashimoto et al. 2014b) and Tyr1902 in hTET2 (Hu et al. 2013a). Also, polar residues such as Asn147, His297, and Asp234 in NgTET contact O2, N3, and N4, respectively, to guide substrate specificities (Hashimoto et al. 2014b), and the methyl or the hydroxymethyl group is oriented toward NOG and Fe(II)/Mn(II) (Hashimoto et al. 2015a; Hu et al. 2015). Often, active site pockets for flipped bases not only contain residues for base recognition but also specifically orient the base for distinct reactions depending on the type of enzymes. Base flipping is therefore a common mechanism applied by different classes of enzymes, such as AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases and αKG- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases to recognize and stabilize the target base for specific reactions.

3.2 AlkB and Homologs

Similar to TET enzymes, eukaryotic homologs of E. coli AlkB such as FTO and ALKBH5 are also αKG- and Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases that can oxidize the methyl group of N6mA within mRNA to yield demethylated adenine (Jia et al. 2011; Zheng et al. 2013; Zhu and Yi 2014). Indeed, TET-DNA complex structures are remarkably comparable to that of the AlkB-DNA complex, and both TET enzymes and AlkB homologs perform base flipping as part of their reaction mechanism (Hu et al. 2013a; Iyer et al. 2013; Hashimoto et al. 2014b; Zhu and Yi 2014; McDonough et al. 2010). Common structural folds include two twisted β-sheets in the core where the active site is formed (Fig. 2b). However, the two enzyme families differ in an important way. TET enzymes oxidize CH3 attached to an inert carbon atom (cytosine or thymine C5). The resulting product 5hmC (or 5hmU) is very stable and can undergo further oxidations in subsequent rounds of reactions to generate further oxidized products. On the other hand, FTO and ALKBH5 likely generate N6-hydroxymethyladenine intermediate in which the oxidized carbon is attached to a reactive nitrogen atom (adenine-N6). This intermediate spontaneously releases the hydroxymethyl group as formaldehyde and decomposes to adenine—the final “demethylated” product (Hashimoto et al. 2015b) (Fig. 1b). Therefore, AlkB and its homologs are demethylases, while TET enzymes should not be designated as a demethylase but would rather be appropriately understood as a “writer” that generates additional marks on 5mC within genomes to alter epigenetic signals.

Several biochemical observations suggest that modified cytosines beyond 5mC may form distinct epigenetic signals. Many 5mCpG readers such as methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD) proteins have shown significantly reduced binding affinity toward 5hmC when compared to 5mC within CpG context (Hashimoto et al. 2012b), whereas some proteins may preferentially bind 5hmC (Spruijt et al. 2013). DNMT1 has a significantly reduced affinity toward hemi-hydroxymethylated DNA substrate compared to hemi-methylated DNA (Hashimoto et al. 2012b), suggesting that methylation marks altered by TET enzymes can be lost in subsequent DNA replications. In addition, the RNA polymerase II transcription rate can be specifically reduced by 5fC and 5caC (Kellinger et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2015). These findings strongly point to the possibility that modifications beyond 5mC are distinct signals, and much future work is needed to elucidate how the modified bases are differently implicated in larger biological contexts.

4 Base Flipping in the Recognition of Modified Bases

4.1 Eukaryotic SRA Domains

The function of 5mC and N6mA in prokaryotes was classically understood in the context of restriction-modification systems, in which methylated bacterial DNA is protected from restriction digestion (Wilson and Murray 1991). Effects of DNA methylation are fundamentally determined by the way the methyl groups alter various protein-DNA interactions. In eukaryotes, genomic 5mC bases are widely involved in various regulatory processes to control gene expression, chromatin states, and genomic stability that are highly relevant in the human disease context (Robertson 2005). Such penetrating biological implications can be partly attributed to a large number of protein-DNA interactions that are potentially affected by DNA methylation in a direct manner. Evidence shows that several transcription factors are prevented from DNA binding when the binding site is methylated (Tate and Bird 1993), whereas several MBD family proteins are specific 5mCpG readers, as previously mentioned (Klose and Bird 2006). The interface between methylated DNA and its biological effects can be further complicated by the involvement of the nucleosome context which is closely interwoven with DNA methylation (Hashimoto et al. 2010; Cedar and Bergman 2009).

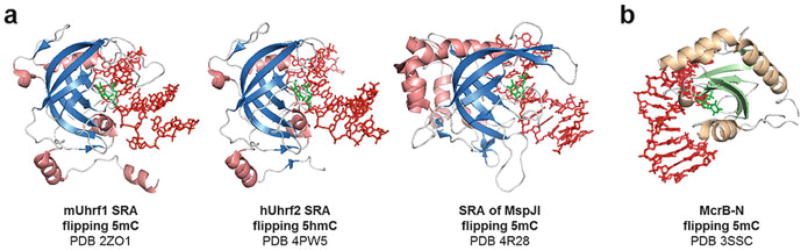

The initial discovery of 5mC-binding proteins has raised the possibility of other readers involved in modified base recognitions. In 2007, another family of 5mC readers was discovered in plants and was termed SET and RING associated (SRA) domain as a part of VIM1 (Woo et al. 2007). A mammalian homolog to VIM1 is Uhrf1, which can associate with DNMT1 during post-replicative maintenance of DNA methylation (Bostick et al. 2007). In the following year, three crystal structures of the mammalian Uhrf1 SRA domain in complex with 5mC-containing DNA were reported (Hashimoto et al. 2008; Avvakumov et al. 2008; Arita et al. 2008). The structures have revealed that SRA recognizes 5mC by base flipping, although it is not a DNA-modifying enzyme such as methyltransferases or dioxygenases. SRA is also structurally distinct from other base flippers and is characterized by a twisted β-sheet fold resembling a half-moon shape (Fig. 3a). Remarkably, the 5mC-binding pocket of SRA features familiar modes of base recognitions exemplified by π stacking interactions, recognitions of the N3 and N4 by Asp474 side chain, and a van der Waals contact of the C5-methyl group of flipped 5mC by Ser486 Cβ.

Fig. 3.

Readers of DNA modifications. (a) Prokaryotic and eukaryotic SRA domains recognize C5-modified cytosine via base flipping and are similar in structures. (b) Crystal structure of prokaryotic McrB-N monomer flipping 5mC

Interestingly, the SRA of Uhrf2 binds 5hmC with a slightly higher preference compared to 5mC, and the crystal structure of Uhrf2 SRA in complex with 5hmC-containing DNA is available (Zhou et al. 2014). In the structure, 5hmC is flipped and stabilized, and the OH moiety of the hydroxymethyl group is contacted by the back-bone carbonyl groups of Thr508 and Gly509 in the active site pocket which is slightly larger in size compared to that of Uhrf1 SRA. Therefore, the eukaryotic SRA domain has been characterized as a base-flipping domain that recognizes both 5mC and 5hmC.

4.2 Prokaryotic SRA Domains

Recently, SRA domains have been rediscovered in prokaryotes in families of modification-dependent restriction enzymes that recognize modified bases and introduce a double-stranded break in some distances away. MspJI was among the first such enzymes to be reported, which recognizes hemi-modified 5mC or 5hmC by the N-terminal SRA-like domain and restricts the DNA by the C-terminal endonuclease domain (Cohen-Karni et al. 2011). The crystal structure of MspJI has been solved with substrate DNA, revealing an SRA-like structure in the N-terminal modification recognition domain that flips the target 5mC (Cohen-Karni et al. 2011; Horton et al. 2014c). Despite the lack of amino acid sequence conservation between eukaryotic UHRF1/2 SRA and MspJI SRA, all SRA domains feature a twisted β-sheet fold with a half-moon shape (Fig. 3a).

As more modification-dependent restriction enzymes have been identified, some of them are found with different specificities toward 5mC, 5hmC, and 5ghmC. AbaSI, unlike MspJI, has an N-terminal Vsr-like endonuclease domain and a C-terminal SRA-like domain (Borgaro and Zhu 2013; Horton et al. 2014a). Its SRA domain seems to preferentially recognize 5ghmC and 5hmC compared to 5mC, as the relative rate of cleavage of DNA containing the corresponding modification is 5ghmC:5hmC:5mC = 8000:500:1 (Wang et al. 2011). Structural features within SRA domains that fine-tune such specificities await future characterizations.

4.3 McrB-N as Distinct 5mC Reader

Modification-dependent restriction enzymes also utilize yet another 5mC recognition domain (Fig. 3b). The N-terminus of McrB (McrB-N) recognizes 5mC next to adenine within 5′-ACCGGT-3′ sequences, and McrC associates with McrB to provide endonuclease activity (Sutherland et al. 1992; Gast et al. 1997). The crystal structure of McrB-N in complex with 5mC-containing DNA shows flipped 5mC in the active site, revealing a novel fold distinct from any other known base flippers (Sukackaite et al. 2012). The active site displays familiar π stacking of the flipped 5mC via aromatic residues and van der Waals contact of the C5-methyl group via the side chain of Leu68. So far, SRA is the only known modified base reader in eukaryotes that flips the target base, and no eukaryotic homolog of McrB-N has been identified. However, the history of the discovery of base flippers suggests a strong possibility of its structural homologs present in a wide spectrum of phyla.

4.4 DpnI as N6mA Reader

While base flipping seems to be a major mechanism by which a modified DNA base can be recognized, it should be noted that modified bases can be recognized by some transcription factors in a sequence-dependent context as well (Spruijt et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2013b), none of which involves base flipping. Along with the previously mentioned MBD family proteins that recognize 5mC within the simple dinucleotide CpG sequence, certain mammalian zinc-finger family proteins such as Kaiso (Buck-Koehntop et al. 2012), Zfp57 (Liu et al. 2012), Klf4 (Liu et al. 2014), and Egr1 (Hashimoto et al. 2014a) bind 5mC within specific sequences via a common structural motif (Liu et al. 2013; Hashimoto et al. 2015b). In addition, another zinc-finger transcription factor WT1 (Hashimoto et al. 2014a) and the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family Tcf3-Ascl1 heterodimer (Golla et al. 2014) can specifically bind 5caC within their consensus sequences. In prokaryotes, DpnI harbors a C-terminal winged-helix (WH) domain that recognizes the methyl group of N6mA within 5′-GATC-3′ sequence via Trp138 involving van der Waals interactions (Mierzejewska et al. 2014). Therefore, DNA modifications may regulate transcription-binding sites in much more dynamic and selective manners than they were previously understood.

5 Base Flipping in Removing Modified and Unmodified Bases

5.1 Mammalian Thymine DNA Glycosylase (TDG)

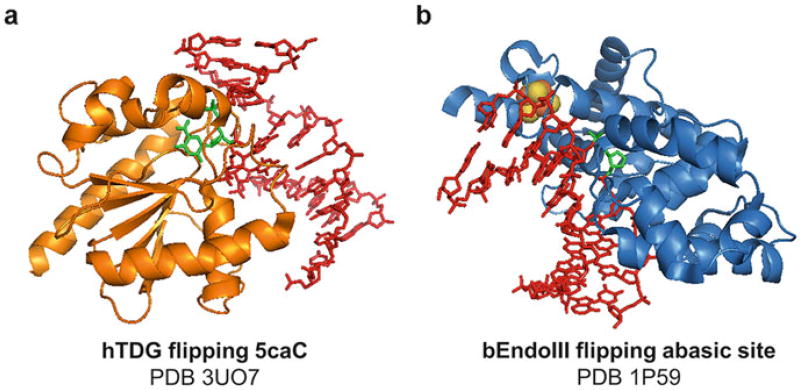

The discovery of TET-mediated modified cytosine bases has provided a fresh insight into a long sought-after pathway of 5mC demethylation/demodification within mammalian genomes (see review (Zhu 2009)). In the base excision repair pathway, DNA glycosylases cleave the glycosidic bond between the ribose and the target base and represent the most structurally diverse family of base-flipping enzymes (Brooks et al. 2013). Initially, it was hypothesized that 5mC is removed by 5mC DNA glycosylase(s), as mammalian 5mC DNA glycosylase activity had been reported (Vairapandi and Duker 1993, 1996; Vairapandi et al. 2000). However, the glycosylase involved was never identified. After the discovery of TET enzymes, mammalian TDG that generally removes uracil or thymine mismatched to guanine was surprisingly revealed to excise 5fC and 5caC to establish genome-wide DNA demethylation (He et al. 2011; Maiti and Drohat 2011; Hashimoto et al. 2012a; Zhang et al. 2012). The crystal structure of the human TDG catalytic domain in complex with 5caC-containing DNA was also solved (Fig. 4a), presenting the flipped base in the active site where the C5-carboxyl moiety of 5caC is specifically recognized by the side chain of Asn157 and the Tyr152 amide backbone (Zhang et al. 2012). The discovery of TDG excising 5fC and 5caC has effectively linked the base excision repair pathway to DNA demethylation in mammalian system.

Fig. 4.

Erasers of DNA modifications. (a) Crystal structure of human TDG flipping 5caC opposite guanine. (b) Crystal structure of Geobacillus stearothermophilus endonuclease III in complex with DNA. Iron-sulfur cluster is colored in orange and yellow

5.2 Plant ROS1

In plants, paradoxically, bona fide 5mC DNA glycosylases were clearly demonstrated and identified in 2002 (Gong et al. 2002), approximately a decade before TET and TDG were implicated in DNA demethylation. In Arabidopsis, four closely related 5mC DNA glycosylases exist: ROS1, DME, DML2, and DML3 (Gong et al. 2002; Morales-Ruiz et al. 2006; Gehring et al. 2006; Ortega-Galisteo et al. 2008). They have a catalytic glycosylase domain homologous to E. coli endonuclease III (Fig. 4b), a helix-hairpin-helix (HhH) fold DNA glycosylase that harbors an iron-sulfur cluster-binding site and excises damaged pyrimidines (Ponferrada-Marin et al. 2009, 2011; Mok et al. 2010). Both ROS1 and DME have been shown to excise 5mC in vivo and in vitro (Gong et al. 2002; Ponferrada-Marin et al. 2009; Gehring et al. 2006; Mok et al. 2010), and they are shown to excise 5hmC, but not 5fC and 5caC in vitro (Hong et al. 2014; Jang et al. 2014; Brooks et al. 2014). Thus, plant ROS1 and mammalian TDG have mutually exclusive substrate specificities for 5mC, 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC; the first two are substrates for ROS1 and the latter two for TDG (Hashimoto et al. 2012a; Hong et al. 2014). One of the most surprising aspects of plant 5mC DNA glycosylases is that they excise the target base only when both the catalytic glycosylase domain and the C-terminal domain are present (Hong et al. 2014; Mok et al. 2010). The C-terminal domain of ROS1 is conserved only among plant 5mC DNA glycosylases and has been shown to strongly associate with the catalytic domain, suggesting that domain-domain interactions are important for target base recognition and excision (Hong et al. 2014).

While TDG and ROS1 have been clearly implicated in DNA demethylation pathways, jury is still out on the possibility of the contribution of other pathways to DNA demethylation. In addition to the previously mentioned mammalian 5mC DNA glycosylase activities, 5hmC DNA glycosylase activity was observed in a calf thymus extract (Cannon et al. 1988). A recent proteomic study has revealed that several mammalian DNA glycosylases such as NTH1, OGG1, NEIL1, and NEIL2 bind 5mC- and 5hmC-containing DNA in a modification-specific manner (Spruijt et al. 2013), though they by themselves do not have the glycosylase activity against 5mC or 5hmC (Hong et al. 2014).

The 5mC DNA glycosylase activity by ROS1 is interesting from a standpoint of historical characterization of DNA glycosylases as DNA damage repair enzymes. In a given genome, there can be many types of damaged bases, and their diversity is on par with many classes of DNA glycosylases that are structurally distinct (Brooks et al. 2013). On the other hand, 5mC in plants is not considered a damaged base and exists in substantial amounts in the Arabidopsis genome (Zhang et al. 2006). Thus, ROS1 must be regulated and specifically targeted to a certain genomic location to initiate DNA demethylation (Zheng et al. 2008; Qian et al. 2012). In addition to 5mC, ROS1 is comparably active on thymine mismatched to guanine and on some damaged pyrimidines, suggesting that ROS1 can be involved in both DNA demethylation and DNA damage repair (Ponferrada-Marin et al. 2009, 2010). Such dual functionality can be applied to TDG as well, which not only excises thymine or uracil mismatched to G during the process of DNA mismatch repair but also excises 5fC and 5caC base paired with guanine for DNA demodification in mammals (He et al. 2011; Maiti and Drohat 2011; Hashimoto et al. 2012a; Zhang et al. 2012).

5.3 Achaeon PabI Activity as Adenine DNA Glycosylase

Interestingly, the archaeal Pyrococcus abyssi PabI enzyme was initially thought to be a restriction endonuclease but has recently been re-characterized as a sequence-specific adenine DNA glycosylase (Miyazono et al. 2014). PabI is comparable to MutY family mismatch repair DNA glycosylases that excise target adenine mismatched to 8-oxoguanine (Fromme et al. 2004). However PabI is remarkably distinct from MutY, because PabI excises adenine correctly base paired to thymine in a targeted manner. It is therefore possible that DNA glycosylases have adapted to function in more processes than DNA damage repair by removing benign bases for various biological regulations.

Conclusions

First observed in 1994 in the crystal structure of M.HhaI with DNA, base flipping is now understood as a common mode of protein-DNA/RNA interactions adopted by structurally and functionally distinct classes of proteins across various phyla. Base flipping is the only known mechanism for establishing DNA modifications in a targeted manner via DNA methyltransferases and TET dioxygenases. What used to be considered a eukaryote-specific base-flipping 5mC reader, SRA, has later been shown to be widely prevalent in prokaryotic systems for recognizing several modified bases including 5mC, 5hmC, and 5ghmC. In addition to SRA, more structurally diverse classes of modified base readers have been discovered in prokaryotes, such as the base-flipping 5mC reader McrB-N and the N6mA-recognizing WH domain of DpnI (using non-base-flipping mechanism). Also, DNA glycosylases are base flippers primarily characterized as DNA repair enzymes, though not all DNA glycosylases flip a base/nucleotide for base excision, as presented in the very recent example of bacterial AlkD (Mullins et al. 2015). Today, DNA demodification is considered a bona fide output of the base excision repair pathway through DNA glycosylases, such as mammalian TDG and plant ROS1 whose mechanism of action again involves base flipping. In an era in which DNA modifications are considered critical and increasingly complex epigenetic signals, this simple, but elegant, structural mechanism for protein-DNA interaction is preserved as a truly ubiquitous framework.

Acknowledgments

The work in the authors’ laboratory is supported by grant from National Institutes of Health (GM049245-22). X.C. is a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar.

Abbreviations

- 5caC

5-Carboxylcytosine

- 5fC

5-Formylcytosine

- 5ghmC

Glucosylated 5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5hmC

5-Hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5mC

5-Methylcytosine

- AdoHcy

S-Adenosyl-l-homocysteine

- AdoMet

S-Adenosyl-l-methionine

- AlkB

E. coli alkylated DNA repair protein

- ALKBH5

Alkylated DNA repair protein AlkB homolog 5 in human

- CMT2

Chromomethylase 2 (plant specific)

- CMT3

Chromomethylase 3 (plant specific)

- DME

Demeter (plant)

- DML3

Demeter-like protein 3 (plant)

- DNMT1

Mammalian DNA methyltransferase 1

- DNMT3A

Mammalian DNA methyltransferase 3A

- DNMT3L

Mammalian DNA methyltransferase 3-like

- DRM2

Domain rearranged methyltransferase 2 (plant)

- FTO

Fat mass and obesity-associated protein

- HhH

Helix-hairpin-helix

- JBP

J-binding protein

- MBD

Methyl-CpG-binding domain

- McrB

Modified cytosine restriction B

- Met1

DNA methyltransferase 1 (plant)

- MTase

Methyltransferase

- N4mC

N4-methylcytosine

- N6mA

N6-methyladenine

- NOG

N-oxalylglycine

- ROS1

Repressor of silencing 1 (plant specific)

- SRA

SET and RING associated

- TDG

Thymine DNA glycosylase

- TET

Ten-eleven translocation

- TRD

Target recognition domain

- Uhrf1

Ubiquitin-like-containing PHD and RING finger domains protein 1

- WH

Winged helix

- αKG

α-Ketoglutarate

Contributor Information

Samuel Hong, Department of Biochemistry, Emory University School of Medicine, 1510 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA; Molecular and Systems Pharmacology Graduate Program, Emory University School of Medicine, 1510 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

Xiaodong Cheng, Department of Biochemistry, Emory University School of Medicine, 1510 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, USA.

References

- Arita K, Ariyoshi M, Tochio H, Nakamura Y, Shirakawa M. Recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA protein UHRF1 by a base-flipping mechanism. Nature. 2008;455(7214):818–21. doi: 10.1038/nature07249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvakumov GV, Walker JR, Xue S, Li Y, Duan S, Bronner C, et al. Structural basis for recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA domain of human UHRF1. Nature. 2008;455(7214):822–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bheemanaik S, Reddy YV, Rao DN. Structure, function and mechanism of exocyclic DNA methyltransferases. Biochem J. 2006;399(2):177–90. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal RM, Gregory SA, Cooperider JS. Cloning of a restriction-modification system from Proteus vulgaris and its use in analyzing a methylase-sensitive phenotype in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;164(2):501–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.2.501-509.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgaro JG, Zhu Z. Characterization of the 5-hydroxymethylcytosine-specific DNA restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(7):4198–206. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst P, Sabatini R, Base J. discovery, biosynthesis, and possible functions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:235–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick M, Kim JK, Esteve PO, Clark A, Pradhan S, Jacobsen SE. UHRF1 plays a role in maintaining DNA methylation in mammalian cells. Science. 2007;317(5845):1760–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1147939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SC, Adhikary S, Rubinson EH, Eichman BF. Recent advances in the structural mechanisms of DNA glycosylases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834(1):247–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SC, Fischer RL, Huh JH, Eichman BF. 5-methylcytosine recognition by Arabidopsis thaliana DNA glycosylases DEMETER and DML3. Biochemistry. 2014;53(15):2525–32. doi: 10.1021/bi5002294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck-Koehntop BA, Stanfield RL, Ekiert DC, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wilson IA, et al. Molecular basis for recognition of methylated and specific DNA sequences by the zinc finger protein Kaiso. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(38):15229–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213726109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SV, Cummings A, Teebor GW. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine DNA glycosylase activity in mammalian tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;151(3):1173–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80489-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(5):295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X. Structure and function of DNA methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:293–318. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.001453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Roberts RJ. AdoMet-dependent methylation, DNA methyltransferases and base flipping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(18):3784–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.18.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X, Kumar S, Posfai J, Pflugrath JW, Roberts RJ. Crystal structure of the HhaI DNA methyltransferase complexed with S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Cell. 1993;74(2):299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90421-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Karni D, Xu D, Apone L, Fomenkov A, Sun Z, Davis PJ, et al. The MspJI family of modification-dependent restriction endonucleases for epigenetic studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(27):11040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018448108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme JC, Banerjee A, Huang SJ, Verdine GL. Structural basis for removal of adenine mispaired with 8-oxoguanine by MutY adenine DNA glycosylase. Nature. 2004;427(6975):652–6. doi: 10.1038/nature02306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gast FU, Brinkmann T, Pieper U, Kruger T, Noyer-Weidner M, Pingoud A. The recognition of methylated DNA by the GTP-dependent restriction endonuclease McrBC resides in the N-terminal domain of McrB. Biol Chem. 1997;378(9):975–82. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring M, Huh JH, Hsieh TF, Penterman J, Choi Y, Harada JJ, et al. DEMETER DNA glycosylase establishes MEDEA polycomb gene self-imprinting by allele-specific demethylation. Cell. 2006;124(3):495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedecke K, Pignot M, Goody RS, Scheidig AJ, Weinhold E. Structure of the N6-adenine DNA methyltransferase M.TaqI in complex with DNA and a cofactor analog. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8(2):121–5. doi: 10.1038/84104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golla JP, Zhao J, Mann IK, Sayeed SK, Mandal A, Rose RB, et al. Carboxylation of cytosine (5caC) in the CG dinucleotide in the E-box motif (CGCAG|GTG) increases binding of the Tcf3|Ascl1 helix-loop-helix heterodimer 10-fold. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;449(2):248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gommers-Ampt JH, Van Leeuwen F, de Beer AL, Vliegenthart JF, Dizdaroglu M, Kowalak JA, et al. beta-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil: a novel modified base present in the DNA of the parasitic protozoan T. brucei. Cell. 1993;75(6):1129–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90322-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong W, O’Gara M, Blumenthal RM, Cheng X. Structure of pvu II DNA-(cytosine N4) methyltransferase, an example of domain permutation and protein fold assignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(14):2702–15. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Morales-Ruiz T, Ariza RR, Roldan-Arjona T, David L, Zhu JK. ROS1, a repressor of transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis, encodes a DNA glycosylase/lyase. Cell. 2002;111(6):803–14. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowher H, Jeltsch A. Enzymatic properties of recombinant Dnmt3a DNA methyltransferase from mouse: the enzyme modifies DNA in a non-processive manner and also methylates non-CpG [correction of non-CpA] sites. J Mol Biol. 2001;309(5):1201–8. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta YK, Chan SH, Xu SY, Aggarwal AK. Structural basis of asymmetric DNA methylation and ATP-triggered long-range diffusion by EcoP15I. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7363. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Horton JR, Zhang X, Bostick M, Jacobsen SE, Cheng X. The SRA domain of UHRF1 flips 5-methylcytosine out of the DNA helix. Nature. 2008;455(7214):826–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Vertino PM, Cheng X. Molecular coupling of DNA methylation and histone methylation. Epigenomics. 2010;2(5):657–69. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Hong S, Bhagwat AS, Zhang X, Cheng X. Excision of 5-hydroxymethyluracil and 5-carboxylcytosine by the thymine DNA glycosylase domain: its structural basis and implications for active DNA demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012a;40(20):10203–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Liu Y, Upadhyay AK, Chang Y, Howerton SB, Vertino PM, et al. Recognition and potential mechanisms for replication and erasure of cytosine hydroxymethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012b;40(11):4841–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Olanrewaju YO, Zheng Y, Wilson GG, Zhang X, Cheng X. Wilms tumor protein recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine within a specific DNA sequence. Genes Dev. 2014a;28(20):2304–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.250746.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Pais JE, Zhang X, Saleh L, Fu ZQ, Dai N, et al. Structure of a Naegleria Tet-like dioxygenase in complex with 5-methylcytosine DNA. Nature. 2014b;506(7488):391–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Pais JE, Dai N, Correa IR, Jr, Zhang X, Zheng Y, et al. Structure of Naegleria Tet-like dioxygenase (NgTet1) in complexes with a reaction intermediate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015a;43(22):10713–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Zhang X, Vertino PM, Cheng X. The mechanisms of generation, recognition, and erasure of DNA 5-methylcytosine and thymine oxidations. J Biol Chem. 2015b;290(34):20723–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.656884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattman S. DNA-[adenine] methylation in lower eukaryotes. Biochem Biokhimiia. 2005;70(5):550–8. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YF, Li BZ, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science. 2011;333(6047):1303–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Hashimoto H, Kow YW, Zhang X, Cheng X. The carboxy-terminal domain of ROS1 is essential for 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylase activity. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(22):3703–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Liebert K, Hattman S, Jeltsch A, Cheng X. Transition from nonspecific to specific DNA interactions along the substrate-recognition pathway of dam methyltransferase. Cell. 2005;121(3):349–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Mabuchi MY, Cohen-Karni D, Zhang X, Griggs RM, Samaranayake M, et al. Structure and cleavage activity of the tetrameric MspJI DNA modification-dependent restriction endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(19):9763–73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Borgaro JG, Griggs RM, Quimby A, Guan S, Zhang X, et al. Structure of 5-hydroxy methylcytosine-specific restriction enzyme, AbaSI, in complex with DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014a;42(12):7947–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Nugent RL, Li A, Mabuchi MY, Fomenkov A, Cohen-Karni D, et al. Structure and mutagenesis of the DNA modification-dependent restriction endonuclease AspBHI. Sci Rep. 2014b;4:4246. doi: 10.1038/srep04246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton JR, Wang H, Mabuchi MY, Zhang X, Roberts RJ, Zheng Y, et al. Modification-dependent restriction endonuclease, MspJI, flips 5-methylcytosine out of the DNA helix. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014c;42(19):12092–101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Li Z, Cheng J, Rao Q, Gong W, Liu M, et al. Crystal structure of TET2-DNA complex: insight into TET-mediated 5mC oxidation. Cell. 2013a;155(7):1545–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Wan J, Su Y, Song Q, Zeng Y, Nguyen HN, et al. DNA methylation presents distinct binding sites for human transcription factors. Elife. 2013b;2:e00726. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Lu J, Cheng J, Rao Q, Li Z, Hou H, et al. Structural insight into substrate preference for TET-mediated oxidation. Nature. 2015;527(7576):118–22. doi: 10.1038/nature15713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, et al. Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science. 2011;333(6047):1300–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer LM, Zhang D, Burroughs AM, Aravind L. Computational identification of novel biochemical systems involved in oxidation, glycosylation and other complex modifications of bases in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(16):7635–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang H, Shin H, Eichman BF, Huh JH. Excision of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine by DEMETER family DNA glycosylases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446(4):1067–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A. Beyond Watson and Crick: DNA methylation and molecular enzymology of DNA methyltransferases. Chembiochem Eur J chem biol. 2002;3(4):274–93. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020402)3:4<274::AID-CBIC274>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature. 2007;449(7159):248–51. doi: 10.1038/nature06146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia G, Fu Y, He C. Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet. 2013;29(2):108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellinger MW, Song CX, Chong J, Lu XY, He C, Wang D. 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine reduce the rate and substrate specificity of RNA polymerase II transcription. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(8):831–3. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimasauskas S, Kumar S, Roberts RJ, Cheng X. HhaI methyltransferase flips its target base out of the DNA helix. Cell. 1994;76(2):357–69. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klose RJ, Bird AP. Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31(2):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg SR, Zimmerman SB, Kornberg A. Glucosylation of deoxyribonucleic acid by enzymes from bacteriophage-infected Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1961;236:1487–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324(5929):929–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Cheng X, Klimasauskas S, Mi S, Posfai J, Roberts RJ, et al. The DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(1):1–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(3):204–20. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman IR, Pratt EA. On the structure of the glucosylated hydroxymethylcytosine nucleotides of coliphages T2, T4, and T6. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:3254–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, Bestor TH, Jaenisch R. Targeted mutation of the DNA methyltransferase gene results in embryonic lethality. Cell. 1992;69(6):915–26. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth AM, Cao X, Jackson JP, Zilberman D, McCallum CM, Henikoff S, et al. Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for maintenance of CpXpG methylation. Science. 2001;292(5524):2077–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1059745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Toh H, Sasaki H, Zhang X, Cheng X. An atomic model of Zfp57 recognition of CpG methylation within a specific DNA sequence. Genes Dev. 2012;26(21):2374–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.202200.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang X, Blumenthal RM, Cheng X. A common mode of recognition for methylated CpG. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38(4):177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Olanrewaju YO, Zheng Y, Hashimoto H, Blumenthal RM, Zhang X, et al. Structural basis for Klf4 recognition of methylated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(8):4859–67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low DA, Weyand NJ, Mahan MJ. Roles of DNA adenine methylation in regulating bacterial gene expression and virulence. Infect Immun. 2001;69(12):7197–204. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7197-7204.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti A, Drohat AC. Thymine DNA glycosylase can rapidly excise 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine: potential implications for active demethylation of CpG sites. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(41):35334–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.284620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough MA, Loenarz C, Chowdhury R, Clifton IJ, Schofield CJ. Structural studies on human 2-oxoglutarate dependent oxygenases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(6):659–72. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierzejewska K, Siwek W, Czapinska H, Kaus-Drobek M, Radlinska M, Skowronek K, et al. Structural basis of the methylation specificity of R.DpnI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(13):8745–54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Furuta Y, Watanabe-Matsui M, Miyakawa T, Ito T, Kobayashi I, et al. A sequence-specific DNA glycosylase mediates restriction-modification in Pyrococcus abyssi. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3178. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok YG, Uzawa R, Lee J, Weiner GM, Eichman BF, Fischer RL, et al. Domain structure of the DEMETER 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(45):19225–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014348107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Ruiz T, Ortega-Galisteo AP, Ponferrada-Marin MI, Martinez-Macias MI, Ariza RR, Roldan-Arjona T. DEMETER and REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 1 encode 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(18):6853–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601109103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins EA, Shi R, Parsons ZD, Yuen PK, David SS, Igarashi Y, et al. The DNA glycosylase AlkD uses a non-base-flipping mechanism to excise bulky lesions. Nature. 2015;527(7577):254–8. doi: 10.1038/nature15728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Y, Zhao X, Wu YS, Li MM, Wang XJ, Yang YG. N6-methyl-adenosine (m6A) in RNA: an old modification with a novel epigenetic function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2013;11(1):8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi SK, Qiu C, Bernstein E, Li K, Jia D, Yang Z, et al. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature. 2007;448(7154):714–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Galisteo AP, Morales-Ruiz T, Ariza RR, Roldan-Arjona T. Arabidopsis DEMETER-LIKE proteins DML2 and DML3 are required for appropriate distribution of DNA methylation marks. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;67(6):671–81. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pais JE, Dai N, Tamanaha E, Vaisvila R, Fomenkov AI, Bitinaite J, et al. Biochemical characterization of a Naegleria TET-like oxygenase and its application in single molecule sequencing of 5-methylcytosine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(14):4316–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417939112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffeneder T, Spada F, Wagner M, Brandmayr C, Laube SK, Eisen D, et al. Tet oxidizes thymine to 5-hydroxymethyluracil in mouse embryonic stem cell DNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(7):574–81. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponferrada-Marin MI, Roldan-Arjona T, Ariza RR. ROS1 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylase is a slow-turnover catalyst that initiates DNA demethylation in a distributive fashion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(13):4264–74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponferrada-Marin MI, Martinez-Macias MI, Morales-Ruiz T, Roldan-Arjona T, Ariza RR. Methylation-independent DNA binding modulates specificity of Repressor of Silencing 1 (ROS1) and facilitates demethylation in long substrates. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(30):23032–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponferrada-Marin MI, Parrilla-Doblas JT, Roldan-Arjona T, Ariza RR. A discontinuous DNA glycosylase domain in a family of enzymes that excise 5-methylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(4):1473–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian W, Miki D, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhang X, Tang K, et al. A histone acetyltransferase regulates active DNA demethylation in Arabidopsis. Science. 2012;336(6087):1445–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1219416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumara E, Law JA, Simanshu DK, Voigt P, Johnson LM, Reinberg D, et al. A dual flip-out mechanism for 5mC recognition by the Arabidopsis SUVH5 SRA domain and its impact on DNA methylation and H3K9 dimethylation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2011;25(2):137–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1980311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsahoye BH, Biniszkiewicz D, Lyko F, Clark V, Bird AP, Jaenisch R. Non-CpG methylation is prevalent in embryonic stem cells and may be mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(10):5237–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ, Myers PA, Morrison A, Murray K. A specific endonuclease from Haemophilus haemolyticus. J Mol Biol. 1976;103(1):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RJ, Vincze T, Posfai J, Macelis D. REBASE–a database for DNA restriction and modification: enzymes, genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D298–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(8):597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Rechkoblit O, Bestor TH, Patel DJ. Structure of DNMT1-DNA complex reveals a role for autoinhibition in maintenance DNA methylation. Science. 2011;331(6020):1036–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1195380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt CG, Gnerlich F, Smits AH, Pfaffeneder T, Jansen PW, Bauer C, et al. Dynamic readers for 5-(hydroxy)methylcytosine and its oxidized derivatives. Cell. 2013;152(5):1146–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud H, Do T, Du J, Zhong X, Feng S, Johnson L, et al. Non-CG methylation patterns shape the epigenetic landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(1):64–72. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suetake I, Miyazaki J, Murakami C, Takeshima H, Tajima S. Distinct enzymatic properties of recombinant mouse DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. J Biochem. 2003;133(6):737–44. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukackaite R, Grazulis S, Tamulaitis G, Siksnys V. The recognition domain of the methyl-specific endonuclease McrBC flips out 5-methylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(15):7552–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland E, Coe L, Raleigh EA. McrBC: a multisubunit GTP-dependent restriction endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 1992;225(2):327–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90925-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324(5929):930–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate PH, Bird AP. Effects of DNA methylation on DNA-binding proteins and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1993;3(2):226–31. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(93)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M, Duker NJ. Enzymic removal of 5-methylcytosine from DNA by a human DNA-glycosylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(23):5323–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.23.5323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M, Duker NJ. Partial purification and characterization of human 5-methylcytosine-DNA glycosylase. Oncogene. 1996;13(5):933–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vairapandi M, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B, Duker NJ. Human DNA-demethylating activity: a glycosylase associated with RNA and PCNA. J Cell Biochem. 2000;79(2):249–60. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20001101)79:2<249::aid-jcb80>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Guan S, Quimby A, Cohen-Karni D, Pradhan S, Wilson G, et al. Comparative characterization of the PvuRts1I family of restriction enzymes and their application in mapping genomic 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(21):9294–305. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhou Y, Xu L, Xiao R, Lu X, Chen L, et al. Molecular basis for 5-carboxycytosine recognition by RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Nature. 2015;523(7562):621–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren RA. Modified bases in bacteriophage DNAs. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:137–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GG, Murray NE. Restriction and modification systems. Annu Rev Genet. 1991;25:585–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.25.120191.003101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo HR, Pontes O, Pikaard CS, Richards EJ. VIM1, a methylcytosine-binding protein required for centromeric heterochromatinization. Genes Dev. 2007;21(3):267–77. doi: 10.1101/gad.1512007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Santi DV. On the mechanism and inhibition of DNA cytosine methyltransferases. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1985;198:119–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JC, Santi DV. Kinetic and catalytic mechanism of HhaI methyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262(10):4778–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt GR, Cohen SS. The bases of the nucleic acids of some bacterial and animal viruses: the occurrence of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Biochem J. 1953;55(5):774–82. doi: 10.1042/bj0550774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder JA, Soman NS, Verdine GL, Bestor TH. DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases in mouse cells and tissues. Studies with a mechanism-based probe. J Mol Biol. 1997;270(3):385–95. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemach A, Kim MY, Hsieh PH, Coleman-Derr D, Eshed-Williams L, Thao K, et al. The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell. 2013;153(1):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Yazaki J, Sundaresan A, Cokus S, Chan SW, Chen H, et al. Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2006;126(6):1189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lu X, Lu J, Liang H, Dai Q, Xu GL, et al. Thymine DNA glycosylase specifically recognizes 5-carboxylcytosine-modified DNA. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(4):328–30. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Huang H, Liu D, Cheng Y, Liu X, Zhang W, et al. N6-methyladenine DNA modification in Drosophila. Cell. 2015;161(4):893–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Pontes O, Zhu J, Miki D, Zhang F, Li WX, et al. ROS3 is an RNA-binding protein required for DNA demethylation in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2008;455(7217):1259–62. doi: 10.1038/nature07305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Du J, Hale CJ, Gallego-Bartolome J, Feng S, Vashisht AA, et al. Molecular mechanism of action of plant DRM de novo DNA methyltransferases. Cell. 2014;157(5):1050–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Xiong J, Wang M, Yang N, Wong J, Zhu B, et al. Structural basis for hydroxymethylcytosine recognition by the SRA domain of UHRF2. Mol Cell. 2014;54(5):879–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK. Active DNA, demethylation mediated by DNA glycosylases. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:143–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Yi C. Switching demethylation activities between AlkB family RNA/DNA demethylases through exchange of active-site residues. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(14):3659–62. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]