The World Health Organization defines mental health as a “state of well-being whereby individuals recognize their abilities, are able to cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully, and make a contribution to their communities.” Applying such adult based definitions to adolescents and identifying mental health problems in young people can be difficult, given the substantial changes in behaviour, thinking capacities, and identity that occur during the teenage years. The impact of changing youth subcultures on behaviour and priorities can also make it difficult to define mental health and mental health problems in adolescents. Although mental disorders reflect psychiatric disturbance, adolescents may be affected more broadly by mental health problems. These include various difficulties and burdens that interfere with adolescent development and adversely affect quality of life emotionally, socially, and vocationally.

Table 2.

Definition of a mental disorder*

| A mental disorder: |

| • Is behavioural or psychological |

| • Is of clinical significance |

| • Is accompanied by a concomitant distress and/or a raised risk of death, or an important loss of freedom |

| • Involves an unexpected cultural response to any situation |

World Health Organization, 2003 (see “Further Reading” box)

Figure 1.

Mental health problems can affect adolescents' quality of life

Mental disorders and mental health problems seem to have increased considerably among adolescents in the past 20-30 years. The rise has been driven by social change, including disruption of family structure, growing youth unemployment, and increasing educational and vocational pressures. The prevalence of mental health disorders among 11 to 15 year olds in Great Britain is estimated to be 11%, with conduct problems more common among boys and depression and anxiety more common among girls.

Table 3.

Mental health problems and disorders in adolescents*

| Problem or disorder | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

|

Common |

|

| Depression |

3-5 |

| Anxiety |

4-6 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

2-4 |

| Eating disorders |

1-2 |

| Conduct disorder |

4-6 |

| Substance misuse disorder |

2-3 |

|

Less common |

|

| Panic disorder |

1-2 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder |

1-2 |

| Borderline personality disorder |

1-3 |

| Schizophrenia |

0.5 |

| Autistic spectrum disorders (such as autism, Asperger's syndrome) | 0.6 |

Costello et al (Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60: 837-44); Ford et al (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42: 1203-11); Fombonne (J Autism Dev Disord 2003;33: 365-82).

The identification, treatment, and follow up of mental health problems in young people can be complicated. Parents and teachers may dismiss problems as merely reflecting adolescent turmoil. Young people are often very reluctant to seek help, owing to developmental needs about being “normal” at the time when they are exploring identity issues and trying to engage with a peer group.

Table 4.

Criteria for distinguishing normal variations in behaviour from more serious problems

| Duration—Consider as potentially harmful any problems that last more than a few weeks; reassess mental state on several occasions |

| Persistence and severity of fixed symptoms—Loss of normal fluctuations in mood and behaviour |

| Impact of symptoms—School work, interpersonal relations, home and leisure activities |

Normal behaviour versus mental problems

Variations of mood and temporary deviant behaviours are part of the normal adolescent process. It is normal for young people to feel depressed from time to time and for this mood to last several days. Similarly, many young people will experiment with drugs or “delinquent” behaviours as part of normal exploration of their own identity. Such normal behaviours can be distinguished from more serious problems by the duration, persistence, and impact of the symptoms.

Table 1.

Symptoms needing assessment

| • Signs of overt mood depression (low mood, tearfulness, lack of interest in usual activities) |

| • Somatic complaints such as headache, stomach ache, backache, and sleep problems |

| • Self harming behaviours |

| • Aggression |

| • Isolation and loneliness |

| • Deviant behaviour such as theft and robbery |

| • Change in school performance or behaviour |

| • Use of psychoactive substances, including over the counter medications |

| • Weight loss or failure to gain weight with growth |

Assessing young people's risk in non-mental health settings in primary or secondary care can be difficult. Basic requisites include a non-judgmental approach that recognises the young person's rights to confidentiality, where appropriate for the level of risk involved. Several validated screening questionnaires can be used to assess the risk of serious mental health problems in adolescents (Hack et al, “Further reading” box).

Table 6.

Useful instruments for screening for mental health problems in adolescents

| Name of tool (inventor) | Scope of screening | No of items (time needed, minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| Beck depression inventory (Beck) |

Depressive state |

21 (5) |

| SCL-90-R (Derogatis) |

Mental health problems |

90 (12-15) |

| Brief symptom inventory (Derogatis) |

Mental health problems |

53 (8-10) |

| Children's depression inventory (Kovacs) |

Depression |

27 (5-10) |

| Strengths and difficulties questionnaire (Goodman) |

General psychopathology and associated impairment |

25 or 30 (5-10) |

| Child behaviour checklist; youth self report (Achenbach) |

General psychopathology |

120 (25) |

| Giessen test | Psychopathology | 30 (5-10) |

The brief symptom inventory is a shortened version of the SCL-90-R.

Depression

The recognition, evaluation, and treatment of depression and related suicidal or self harming behaviour are the highest priorities in adolescent mental health. Epidemiological studies suggest that at any one time 8% to 10% of adolescents have severe depression. This means that the major burden of assessing and managing adolescent depression falls on primary care practitioners.

Table 5.

Signs and symptoms of severe depression*

| • Persistent sad or irritable mood |

| • Loss of interest in activities once enjoyed |

| • Substantial change in appetite or body weight |

| • Oversleeping or difficulty sleeping |

| • Psychomotor agitation or retardation |

| • Loss of energy |

| • Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt |

| • Difficulty concentrating |

| • Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide |

| Five or more of these symptoms (including at least one of the first two) must persist for two or more weeks before major depression can be diagnosed |

World Health Organization (see “Further Reading” box)

Adolescence sees the transition from childhood depressive illnesses (depression rare, male predominance, symptoms masked) to more adult forms, with a much increased incidence, a female predominance, and a greater likelihood of presenting with depressed mood. However, masked presentations (for example, behavioural problems, substance misuse, school phobia or failure at school, fatigue, and other somatic symptoms) remain common in early adolescence, particularly in boys.

Table 7.

Potential risk factors for adolescent depression

| • Family history of depression |

| • Recent bereavement or family conflict |

| • Break up of a romantic relationship |

| • Having a chronic medical condition |

| • Physical and sexual abuse |

| • Trauma and severe stress |

| • Anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or behavioural problems |

| • Learning difficulties |

| • Substance misuse |

To evaluate risk of depression properly, young people must be interviewed confidentially and additional information gathered from parents as well as other sources (such as teachers, social workers, or youth workers). As well as eliciting symptoms and risk factors for depression, it is essential to assess potential suicide risk in depressed young people. They must be asked about past and present suicidal ideation and self harming behaviour, past attempts, and whether they plan to harm themselves. Asking about suicide reduces rather than increases the risk of suicide.

Table 8.

Treatment strategies for adolescent depression

| Brief psychological therapies |

| • Cognitive behaviour therapy |

| • Interpersonal psychotherapy |

| Longer term psychotherapy |

| • Longer term psychodynamic therapies may be useful in more severe or persistent cases |

| Antidepressants |

| • Antidepressants are less effective in adolescents than in adults |

| • US and UK doctors have recently been warned that some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may increase the risk of suicidal behaviour in adolescents. The only SSRI approved in the United Kingdom for adolescent depression is fluoxetine |

Treatment usually involves psychotherapy, drug treatment, and a mixture of measures directed at improving the home and school environment.

School phobia

School phobia, also called school refusal, is defined as a persistent and irrational fear of going to school. It must be distinguished from a mere dislike of school that is related to issues such as a new teacher, a difficult examination, the class bully, lack of confidence, or having to undress for a gym class. The phobic adolescent shows an irrational fear of school and may show marked anxiety symptoms when in or near the school.

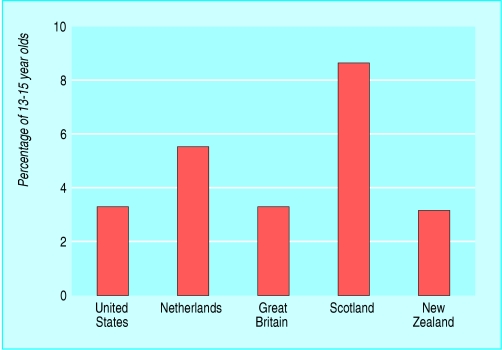

Figure 2.

Cognitive behaviour therapy, usually for 12-16 weeks, is the treatment of choice for most adolescent depression; however, although cognitive behaviour therapy by general practitioners is effective in adults, its effectiveness is yet to be confirmed in adolescents

School phobia often occurs alongside social and other phobias and may be quite disabling, leading to failure in school and later vocational failure. Management usually requires involvement of the young person's whole “system”—including parents, siblings, and the school. Short term cognitive behaviour therapy, as well as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, has also been shown to be effective.

Table 9.

Behaviour disorders

| Behaviour disorders present difficulties for families, social services, and education |

| They rarely present as a clinical problem in primary or secondary care |

| Clinicians may become involved when there are other comorbid conditions (such as depression or substance misuse) and when other family members are affected by the young person's behaviour |

| Behaviour disorders rarely manifest for the first time in adolescence; the sudden development of new behaviour problems in adolescence may reflect underlying family problems, depression, or substance misuse |

Learning disabilities

Learning disability encompasses disorders that affect the way individuals with normal or above normal intelligence receive, store, organise, retrieve, and use information. Problems include dyslexia and other specific learning problems involving reading, spelling, writing, reasoning, and mathematics.

Undiagnosed learning disabilities are a common but manageable cause of young people deciding to leave school at the earliest opportunity. The clinicians' role in these situations is to screen for health conditions that may affect performance (such as hearing or vision problems or neurological disorders) and to identify psychosocial and environmental factors that may affect learning abilities (such as family disruption, poor peer relationships, or cultural and economic difficulties).

Conduct disorders

Conduct disorder can be defined as persistently disruptive behaviour in which the young person repeatedly violates the rights of others or age appropriate social norms. It is often preceded by oppositionality and defiance in early years and can become more disruptive during adolescence. Symptoms include damage to property, lying or theft, truancy, violations of rules, and aggression towards people or animals. Teenagers with a conduct disorder often have concomitant disorders such as depression, suicidal behaviour, and poor relationships with peers and adults. Consequences include school problems, school expulsions, academic and vocational failure, and problems with the law. Parents and families need support to help them make sure that the young person does not stay away from school, and severely affected adolescents should be referred to mental health professionals for evaluation and care.

Figure 3.

Conduct disorder (defined in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition) in 13-15 year olds in selected countries. Data from West et al (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42: 941-9); Ford et al (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2003;42: 1203-11); Verhulst et al (Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54: 329-36); Costello et al (Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60: 837-44)

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Definitions of the symptom complex known as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) differ, but severe problems with concentration or attention and/or hyperactivity are estimated to affect about 5% of adolescents (Kondo et al, see “Further reading” box). Six times as many boys as girls are affected. The main consequences of ADHD are poor academic performance and behavioural problems, although adolescents with ADHD are at substantially higher risk of serious accidents, depression, and other psychological problems. About 80% of children with ADHD continue to have the disorder during adolescence, and as many as 50% of adolescents still do throughout adulthood. The main differential diagnoses are with behavioural problems secondary to poor parenting or poor school supervision.

Table 10.

Symptoms suggestive of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)*

| Inattention |

| • Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in school work |

| • Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities |

| • Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly |

| • Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish school work, chores, duties in the workplace |

| • Often has difficulty organising tasks and activities |

| • Often is distracted by extranaeous stimuli and is forgetful in daily activities |

| Hyperactivity |

| • Often fidgets with hands or feet or squirms in seat |

| • Often leaves seat in classroom or other situation where it is inappropriate (or, more usually in adolescents, just feelings of restlessness) |

| • Often runs about or climbs excessively in situations where this is inappropriate (or, more usually in adolescents, just feelings of restlessness) |

Kondo et al (see “Further Reading” box)

Milder forms of ADHD can be amenable to simple management strategies. More severe problems may require treatment, including educational changes, behavioural programmes, family therapy, individual counselling, and the use of stimulant medications such as methylphenidate and dexamphetamine. Although the use of such stimulants remains controversial, there is strong evidence that they improve educational and behavioural outcomes. However, they should be prescribed only in secondary care and only after a full psychiatric and medical investigation.

Although severe learning problems present in early primary school, more subtle difficulties may be missed until made obvious by the greater academic demands of adolescence when they begin to affect educational performance

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety disorders are relatively common in adolescents and often persist into adulthood. Whereas separation anxiety disorder and mutism are more prevalent among younger children, generalised anxiety disorder and panic attacks emerge during adolescence. Generalised anxiety disorder is marked by uncontrolled excessive worrying, accompanied by difficulty in concentrating, irritability, sleep problems, and often fatigue. Panic disorder is characterised by recurrent spontaneous panic attacks, often associated with physiological and psychological signs and symptoms. As with other mental health problems in adolescence, anxiety disorders are often accompanied by other conditions, particularly depression.

Table 11.

Behavioural strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)*

| At home (parents)—Use simple commands; set defined limits and expectations; praise and reinforce desired behaviours (rewards); establish a formal structure for time schedules; use lists and calendars to help prevent forgetfulness; break long tasks into shorter ones |

| At school (teachers)—Ensure that the young person sits close to the teacher's desk (away from distractions); give only one task at a time (with assignments as short as possible); use written not just oral instructions for homework (in notebook to be taken home); do a daily or weekly report; allow more time for examinations (including untimed tests); ensure than young person can rely on a neighbouring student; ask for the help of a trained specialist tutor |

Kondo et al (see “Further Reading” box)

As many anxiety disorders during adolescence are accompanied by physical symptoms, careful evaluation is needed—at least a complete medical history and a comprehensive physical examination—to exclude conditions such as hypoglycaemic episodes, migraine, seizure, and other neurological problems. Treatment may include simple educational strategies, behavioural interventions, cognitive behaviour therapy, family therapy, and rarely, the use of anxiolytics.

General practitioners must take a substantial role in detecting and treating such problems in order to reduce the overall burden of adolescent mental health problems on individuals and society

The photograph is reproduced with permission from Robin M White/Photonica.

Pierre-André Michaud is medical director of the multidisciplinary adolescent unit, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland, and Eric Fombonne is professor of psychiatry at McGill University, Montreal.

The ABC of adolescence is edited by Russell Viner, consultant in adolescent medicine at University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Great Ormond Street Hospital NHS Trust (rviner@ich.ucl.ac.uk). The series will be published as a book in summer 2005.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- • World Health Organization. Invest in mental health. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

- • Rutter M, Smith D. Psychosocial disorders in young people. Time trends and their causes. New York: Wiley, 1995.

- • Meltzer H, Gatward R, Goodam R, Ford T. The mental health of children and adolescents in Great Britain. 2nd ed. London: Office for National Statistics, 2000.

- • Bower P, Garralda E, Kramer T, Harrington R, Sibbald B. The treatment of child and adolescent mental health problems in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2001;18: 373-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Hack S, Jellinek M. Early identification of emotional and behavioral problems in a primary care setting. In: Juszczak LFM, ed. Adolescent medicine: state of the art reviews. Philadelphia: Belfus Ha, 1996: 335-50. [PubMed]

- • Michael KD, Crowley SL. How effective are treatments for child and adolescent depression? A meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2002;22: 247-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Kondo DG, Chrisman AK, March JS. An evidence-based medicine approach to combined treatment for ADHD in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37(3): 7-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]