Abstract

The tumor suppressor p53 is one of the most important proteins for protection of genomic stability and cancer prevention. Cancers often inactivate it by either mutating its gene or disabling its function. Thus, activating p53 becomes an attractive approach for the development of molecule-based anti-cancer therapy. The past decade and half have witnessed tremendous progress in this area. This essay offers readers with a grand review on this progress with updated information about small molecule activators of p53 either still at bench work or in clinical trials.

Keywords: p53, small molecules, MDM2, MDMX, drug discovery, Inauhzin

Introduction

For many decades, cancer therapy had relied entirely on chemotherapeutic agents in the forms of antimetabolites, alkylating agents, various alkaloids, cytotoxic antibiotics, and other chemicals that target rapidly proliferating cells through different mechanisms such as topoisomerase inhibition, DNA intercalation, and microtubule polymerization (Chabner & Roberts, 2005). With no other options available, chemotherapy, as a consequence of its inherent cytotoxic nature, went hand in hand with a myriad of side effects, ranging from hair loss and fatigue, to gastrointestinal distress and anemia, and to myelosuppression, immunosuppression, neuropathy, secondary leukemia, and organ failure. The advent of innovative molecular and genetic techniques revolutionized our understanding of the mechanisms that govern cancer and provided the tools to target newfound signaling pathways (Grever, Schepartz, & Chabner, 1992; Sawyers, 2004). Rational drug design and targeted therapy prompted a new era of scientific and clinical inquiry and brought with them the possibility of cancer “magic bullets” that could explicitly engage tumor cells and elicit clinical response without the adverse effects that plague conventional chemotherapy (Amato, 1993; Schnipper & Strom, 2001).

Technological advances such as combinatorial chemistry, high-throughput screening, and chemical genetics made possible the development of small molecules that target specific oncogenic pathways (Nero, Morton, Holien, Wielens, & Parker, 2014). Whereas targeted monoclonal antibodies, which are large globular structures, are generally limited to attaching to antigens expressed on cell surfaces or on secreted factors, small molecules are capable of passing through the lipid bilayers of the cell and nuclear membranes, essentially conceding all receptor, cellular, and nuclear proteins as potential targets (Carter, 2006; Dancey & Sausville, 2003; Huang, Armstrong, Benavente, Chinnaiyan, & Harari, 2004). Perhaps the greatest success story of targeted therapy to date is that of the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, which has proven to be exceptionally effective against chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), a white blood cell cancer that previously carried a 4-6 year mediansurvival rate (Druker, 2008). Imatinib targets BCR-ABL1, the fusion gene byproduct of the pathophysiologic chromosomal translocation characteristic of CML and has been largely responsible for the improvement of CML's prognosis to a 90% 5-year survival rate (Druker et al., 2006). Imatinib has also been shown to have activity against two other tyrosine kinases (c-KIT and PDGF-R) and has accordingly been approved for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) that are driven by these aberrant kinases, highlighting the value of a small molecule with multiple targets that can be germane to different cancer profiles as well as less susceptible to resistance (Baselga, 2006; Huang et al., 2004; Zitvogel, Rusakiewicz, Routy, Ayyoub, & Kroemer, 2016). Eager to replicate this success, other small molecules were designed against various cancer-associated targets, but the clinical outcomes of many of these drugs were less than desired. Scientists and clinicians alike learned that designing “magic bullet” therapies could not be achieved by simply uncovering and targeting driver mutations, as cancers possess a remarkable ability to develop resistance through a variety of mechanisms (Gottesman, Fojo, & Bates, 2002; Longley & Johnston, 2005). A mutation in the targeted gene affecting drug binding affinity or the upregulation of an alternative signaling pathway can quickly curtail a drug's effectiveness (Glickman & Sawyers, 2012; Redmond, Papafili, Lawler, & Van Schaeybroeck, 2015). These difficulties have led researchers to explore different approaches towards targeted therapy. Rather than focusing on oncogenes upregulated in specific cancers and instead placing more emphasis on genes found to be more frequently and globally mutated in cancers, perhaps therapies can be developed that have a more universal reach and can therefore affect a larger patient population. One such target and the focus of this review is the tumor suppressor p53.

p53: The Guardian of the Genome

The tumor suppressor p53 is the most recognized and researched protein in the study of human cancers. Since its discovery in 1979 (Lane & Crawford, 1979; Linzer & Levine, 1979), more than 80,000 articles have been published about p53 in nearly all disciplines of biomedical research, encompassing cellular and molecular biology, biochemistry, genetics, biophysics, pharmacology, immunology, clinical research, and more. p53's exceptional ability to protect the cell against a wide range of stressful stimuli, such as oxidative stress, nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, DNA damage, telomere attrition, oncogene expression, and ribosomal dysfunction through both transcription-dependent and independent mechanisms (Meek, 2015; Y. Zhang & Lu, 2009; Zhou, Liao, Liao, & Lu, 2012) is matched by its equally impressive array of protective capabilities, including induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, cellular senescence, DNA repair, and inhibition of angiogenesis and metastasis (Bieging & Attardi, 2012; Levine & Oren, 2009; Sengupta & Harris, 2005). Regulation of the cell cycle by p53 transpires at both the G1 and G2 checkpoints through upregulation of CDK-Rb-E2F modulator p21, and cyclin B-CDC2 modulators 14-3-3σ and GADD45, respectively (Laptenko & Prives, 2006; Taylor & Stark, 2001). Apoptosis is achieved through transcriptional activation of subsets of apoptotic genes, of which is dependent on the source and duration of offending stressors (Vousden & Prives, 2009). Mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis ensues following upregulation of mitochondrial proteins, such as PUMA, BAX, and NOXA, while death-receptor-dependent apoptosis is initiated by membrane proteins KILLER/DR5 and Fas/CD95 (Riley, Sontag, Chen, & Levine, 2008; Roos, Baumgartner, & Kaina, 2004; G. S. Wu et al., 1997). In addition, activation of autophagy regulator DRAM1 may also play a role in apoptosis (Crighton et al., 2006). p53 can also function outside of the nucleus to directly inhibit antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, an example of p53 transcription-independent activity (Green & Kroemer, 2009; Murphy, Leu, & George, 2004). p53's indispensable role in maintaining genome-wide stability has led biologists to christen it the “guardian of the genome”. The gravity of p53's importance in preventing tumor formation and progression is perhaps best highlighted by the frequency with which its functionality is abrogated in cancers, as over 50% of tumors either harbor mutations in its gene, TP53, or cultivate posttranslational modifications that abolish its activity (Leroy et al., 2013; Toledo & Wahl, 2006).

The p53 protein spans 393 amino acids and possesses structural domains characteristic of transcription factors, such as a transactivating domain and a DNA-binding domain, as well as an oligomerization domain, a proline-rich domain, and a basic regulatory region (Bell, Klein, Muller, Hansen, & Buchner, 2002; Y. Wang et al., 1993). The N-terminal transactivating domain (residues 1-62) interacts with basal transcription factors and regulatory proteins, including its primary negative regulatory MDM2 (discussed below) and co-activators acetyltransferases p300 and CBP (Kaustov et al., 2006; Meng, Franklin, Dong, & Zhang, 2014; Teufel, Freund, Bycroft, & Fersht, 2007; X. Wu, Bayle, Olson, & Levine, 1993). Also in the N-terminal region lies the proline-rich domain (residues 63-94), which contains five SH3-domain binding motifs of PxxP sequence and plays a role in p53-induced apoptosis in response to DNA damage (Baptiste, Friedlander, Chen, & Prives, 2002). The oligomerization domain is located in the C-terminal region (residues 325-356) and allows four monomers of p53 to form a homotetramer, a conformation necessary for p53 transcriptional activity (Kitayner et al., 2006; Nagaich et al., 1999). At the end of the C-terminal region is the basic regulatory region (residues 357-393), thought to regulate p53 sequence-specific binding (Friedler, Veprintsev, Freund, von Glos, & Fersht, 2005; Luo et al., 2004). Finally, the core or central DNA-binding domain (residues 94-292) facilitates binding to sequence-specific double-stranded DNA and contains a DNA binding surface comprised of a central β-sheet and two large loops (L2 and L3), stabilized by a zinc ion (Cho, Gorina, Jeffrey, & Pavletich, 1994; Meplan, Richard, & Hainaut, 2000). Stability of the p53 protein is governed by the central domain, and evidence suggests that p53 has evolved to be only marginally stable at physiologic temperatures, as p53 has a melting temperature of 44°C and a half-life of only 9 minutes, shorter than its paralogs p63 and p73 (Bullock et al., 1997; Canadillas et al., 2006). p53 is also kinetically unstable, as the central domain cycles between folded, unfolded, and aggregate states at 37°C (Friedler, Veprintsev, Hansson, & Fersht, 2003). The presence of a zinc ion coordinated by three key cysteine residues and one histidine residue (C-176, C-238, C242, H178) is vital for both stability and accurate binding to DNA-consensus sequences (Butler & Loh, 2003).

Although p53 has indispensible cellular functions, its unintended activation has deleterious effects on normal and developing tissues. Therefore, under physiologic conditions, p53 has a relatively short half-life and its expression is maintained at low levels. The principle regulator of p53 is the oncoprotein and E3 ubiquitin ligase MDM2, also known as HMD2 for its human analog (Y. Haupt, Maya, Kazaz, & Oren, 1997; Honda, Tanaka, & Yasuda, 1997). MDM2 negatively regulates both p53 stability and activity. The N-terminal domain of MDM2 can directly bind to the N-terminal transactivating domain of p53, promoting p53's translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, suppressing its capacity to interact with transcriptional machinery and blocking p53 transcription of target promoters, while the C-terminal RING-finger domain of MDM2, containing E3 ligase activity, ubiquitinates specific lysine residues on p53's C-terminal end, thereby targeting p53 for proteasomal-mediated degradation (Y. Haupt et al., 1997; Kubbutat, Jones, & Vousden, 1997; Marine & Lozano, 2010). MDMX, also known as MDM4 (HDMX/HDM4 for its human analog), is structurally homologous to MDM2 and can both directly bind to and inhibit p53 as well as stabilize MDM2 to potentiate MDM2's ubiquitination capabilities (J. Gu et al., 2002; Marine et al., 2006; Shvarts et al., 1996). Classically, activation of p53 occurs when interaction between p53 and MDM2/MDMX is perturbed, with different stressors having different mechanisms of disruption (Kruse & Gu, 2009). For example, DNA damage triggers the activation of kinases such as Chk1/Chk2 (Shieh, Ahn, Tamai, Taya, &Prives, 2000) and ATM/ATR (Shiloh, 2003), which phosphorylate sites on p53's N-terminus, lowering its affinity for MDM2/MDMX. Alternatively, activation of certain mitogenic signals, such as c-MYC and k-RAS, results in an accumulation of the tumor suppressor p14ARF in the nucleolus, which has the capability to bind to MDM2 and free p53 from MDM2-mediated inhibition (Weber, Taylor, Roussel, Sherr, & Bar-Sagi, 1999; Y. Zhang & Xiong, 1999). Further still, under conditions of nucleolar or ribosomal stress, ribosomal biogenesis is curtailed, promoting an accretion of ribosome-free forms of ribosomal proteins (Pestov, Strezoska, & Lau, 2001; Rubbi & Milner, 2003). Some of these proteins, such as RPL5 and RPL11, have high affinity for MDM2 and their binding, in a similar fashion to p14ARF, protects p53 from MDM2-mediated degradation (Bhat, Itahana, Jin, & Zhang, 2004; Dai & Lu, 2004; Dai et al., 2004; Jin, Itahana, O'Keefe, & Zhang, 2004; Lindstrom, Deisenroth, & Zhang, 2007; Lohrum, Ludwig, Kubbutat, Hanlon, & Vousden, 2003; Y. Zhang & Lu, 2009).

Clearly, interrupting the MDM2-MDMX-p53 interaction is indispensible for p53 activation, and yet, remarkably, one of p53's direct transcriptional targets is MDM2 itself, indicating that regulation of p53 by MDM2 occurs through a negative-feedback loop (Kruse & Gu, 2009). Preserving the integrity of this regulatory loop is essential for both physiologic growth and maintenance of homeostasis. Genetic studies have demonstrated that MDM2 and MDMX knockout mice are embryonically nonviable as a direct result of unrestricted p53 activation, as evidenced by rescue of this lethal phenotype when these mice are introduced to an additional p53 knockout (Jones, Roe, Donehower, & Bradley, 1995; Montes de Oca Luna, Wagner, & Lozano, 1995; Parant et al., 2001). Conversely, gene amplification or overexpression of MDM2 or MDMX and subsequent suppression of p53 activity is found in a variety of human cancers, including breast cancer, lung cancer, soft tissue sarcoma, osteosarcoma, bladder cancer, esophageal cancer, and retinoblastoma (Burgess et al., 2016; Danovi et al., 2004; Gembarska et al., 2012; Laurie et al., 2006; Leach et al., 1993; Ramos et al., 2001). Cancers also develop when TP53 is mutated, with the majority occurring as missense mutations in p53's DNA binding domain (Petitjean, Achatz, Borresen-Dale, Hainaut, & Olivier, 2007). These mutations not only accelerate cancer progression through impinging on p53's ability to transcriptionally regulate tumor suppressive genes, but recent evidence also demonstrates that certain missense mutations give rise to mutant forms of p53 with neomorphic, oncogenic functions (so-called gain-of-function, or GOF, mutants), which directly contribute to tumorigenesis through mechanisms such as increased signaling through epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), and c-MET, repression of tumor suppressor p53 family members p63 and p73, deregulation of metabolic pathways, augmented metastasis and angiogenesis, resistance to chemotherapy, altered epigenetic modifications, and proteasome machinery subversion (S. Haupt, Raghu, & Haupt, 2016; Muller & Vousden, 2014; Walerych et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2015).

Cancers find many ways to block p53 activity. The majority (over 90%) of mutations in the TP53 gene occur in its central DNA-binding domain, with approximately 80% transpiring as missense mutations (Petitjean, Mathe, et al., 2007; Soussi & Lozano, 2005). The resulting mutants can either fail to precisely bind canonical p53 response elements or fail to properly fold into its correct 3D structure, the latter of which often conferring a dominant-negative effect over the wild-type allele (Joerger & Fersht, 2008). These two types of mutants are typically termed contact mutants and structural mutants, respectively, although such categorization may be an oversimplification, as different mutations can prompt distinct modifications to p53 local structure, thermostability, and zinc-binding capabilities, which in turn can have disparate effects on wild-type function (Joerger & Fersht, 2007). Alternatively, cancers may retain wild-type p53 and instead disrupt p53 regulation, such as epigenetic inactivation of p14ARF or, as previously stated, upregulation of MDM2 or MDMX (Nicholson et al., 2001; Saporita, Maggi, Apicelli, & Weber, 2007). With several well established genetic studies having demonstrated that restoration of p53 function reverses tumor growth, a paramount challenge has been to develop molecules that can reactivate the p53 pathway in human cancers and harness its ability to induce cell cycle arrest, senescence, and apoptosis (Martins, Brown-Swigart, & Evan, 2006; Ventura et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2007). p53 activators can generally be grouped into two broad categories depending on the mechanism of action: molecules that activate wild-type p53 and molecules that restore wild-type function of mutant p53s [Table 1]. Many of these molecules have progressed to clinical trials [Table 2].

Table 1. Small molecule activators of p53 and their mechanisms.

| Molecule | Class | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutlin-3a RG7112 (RO5045337) | imidazolines | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Vassilev et al., 2004) (Andreeff et al., 2016; Ray-Coquard et al., 2012; Tovar et al., 2013; Vu et al., 2013) |

| RG7388 (RO5503781/idasanutlin) | pyrrolidine | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (L. Chen et al., 2015; Q. Ding et al., 2013; Lakoma et al., 2015; Phelps et al., 2015; Reis et al., 2016; Zanjirband et al., 2016) |

| RO5353 RO2468 RO8994 | spiroindolinone | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Z. Zhang, X. J. Chu, et al., 2014; Z. Zhang, Q. Ding, et al., 2014) |

| JNJ-26854165 | tryptamine | Inhibits MDM2:p53 proteasome interaction | (Chargari et al., 2011; Kojima et al., 2010; Patel & Player, 2008; Tabernero et al., 2011) |

| HLI98 | 5-deazaflavin | Inhibits MDM2 ubiquitin ligase activity | (Dickens et al., 2013; Roxburgh et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2005) |

| SP-141 | pyirdo[b]indole | MDM2 degradation | (W. Wang et al., 2014) |

| SJ-172550 | imidazoline | MDMX:p53 antagonist | (Bista et al., 2012; Reed et al., 2010) |

| XI-006 (NSC207895) | benzofuroxan | MDMX:p53 antagonist | (Pishas et al., 2015; H. Wang et al., 2011) |

| XI-011 (NSC146109) | pseudourea | MDMX:p53 antagonist | (Roh et al., 2014; H. Wang & Yan, 2011) |

| CTX1 | MDMX:p53 antagonist | (Karan et al., 2016) | |

| RO-2443 RO-5963 | indolyl hydantoin | Dual MDM2/MDMX antagonist | (Graves et al., 2012) (Graves et al., 2012) |

| MI-219 MI-888 MI-773 (SAR405838) | spiro-oxindole | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (K. Ding et al., 2006; Shangary et al., 2008) (Y. Zhao, Yu, et al., 2013) (J. Jung et al., 2016; S. Wang et al., 2014) |

| methylbenzo-amines | methylbenzo-amine | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Dudgeon et al., 2010) |

| imidazole-indoles | imidazole-indole | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Czarna et al., 2010) |

| isoindolinones | isoindolinone | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Hardcastle et al., 2006; Hardcastle et al., 2011; Riedinger et al., 2011) |

| pyrrolo-pyrimidines | pyrrolo-pyrimidine | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Lee et al., 2011) |

| sulphonamides | sulphonamide | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Galatin & Abraham, 2004) |

| benzodiazepines | benzodiazepine | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Z. Yu et al., 2014; Zhuang et al., 2011) |

| pyrrolidinone | pyrrolidinone | Dual MDM2/MDMX antagonist | (Zhuang et al., 2012) |

| pyrrolopyrazole | pyrrolopyrazole | Dual MDM2/NF-κB antagonist | (Zhuang et al., 2014) |

| AM-8553 AM-7209 AMG 232 | piperidonone | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Gonzalez-Lopez de Turiso et al., 2013; Rew et al., 2012; Rew et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014) |

| AM-8735 | morpholinones | (Gonzalez, Eksterowicz, et al., 2014) | |

| NVP-CGM097 | dihydro-isoquinolinone | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Holzer et al., 2015; Jeay et al., 2015; Weisberg et al., 2015) |

| HDM201 | pyrazolo-pyrrolidinone | MDM2:p53 antagonist | (Furet et al., 2016) |

| MK-8242 | Undisclosed | MDM2 inhibitor | (Kang et al., 2016; Ravandi et al., 2016) |

| RO6839921 | methoxybenzoate | MDM2 inhibitor | |

| DS-3032 | hexonamide | MDM2 inhibitor | |

| Tenovin-1/Tenovin-6 | tenovin | SirT1/SirT2 inhibitor | (Lain et al., 2008) |

| Leptomycin B (elactocin) | antibiotic | CRM1 inhibitor | (Kudo et al., 1999; Lecane et al., 2003; Newlands et al., 1996; Smart et al., 1999) |

| Nuclear Export Inhibitors (NEIs) | LMB derivatives | CRM1 inhibitor | (Mutka et al., 2009) |

| Inauhzin | Dual SirT1/IMPDH2 inhibitor | (J. H. Jung et al., 2015; Liao et al., 2012; Q. Zhang, D. Ding, et al., 2012; Q. Zhang et al., 2015; Q. Zhang, S. X. Zeng, et al., 2012; Q. Zhang et al., 2014; Y. Zhang et al., 2013; Y. Zhang et al., 2012) | |

| RITA | p53 activation/DNA damage | (Burmakin et al., 2013; Grinkevich et al., 2009; Issaeva et al., 2004; Krajewski et al., 2005; Weilbacher et al., 2014; C. Y. Zhao et al., 2010) | |

| PK083 | carbazole | Mutant Y220C wild-type reactivation | (Boeckler et al., 2008) |

| PK7088 | pyrrol-pyrazole | Mutant Y220C wild-type reactivation | (X. Liu et al., 2013) |

| ZMC1 | thio-semicarbazone | Mutant R175H wild-type reactivation | (Blanden, Yu, Loh, et al., 2015; Blanden, Yu, Wolfe, et al., 2015; X. Yu et al., 2014; X. Yu et al., 2012) |

| RETRA | Ethanone hydrobromide | Mutant p53, p73-dependent reactivation | (Kravchenko et al., 2008) |

| NSC59984 | Mutant p53, p73-dependent reactivation | (S. Zhang et al., 2015) | |

| Prodigiosin | prodiginine | Mutant p53, p73-dependent reactivation | (Hong et al., 2014; Prabhu et al., 2016) |

| P53R3 | quinazoline | Mutant p53 wild-type reactivation | (Weinmann et al., 2008) |

| SCH529074 | quinazoline | Mutant p53 wild-type reactivation | (Demma et al., 2010) |

| CP-31398 | styrylquinazoline | Mutant p53 wild-type reactivation | (Rippin et al., 2002; W. ang et al., 2003) |

| chetomin | dithiodiketo- piperazine | Mutant R175H wild- type reactivation | (Hiraki et al., 2015) |

| APR-246 (PRIMA-1MET) | quinuclidinone | Mutant p53 wild- type reactivation/TrxR1 inhibitor | (Bykov et al., 2002; Bykov et al., 2005; Fransson et al., 2016; Grellety et al., 2015; Lambert et al., 2009; Mohell et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2013; Rokaeus et al., 2010; Saha et al., 2013; Shalom-Feuerstein et al., 2013; J. Shen et al., 2013; Sobhani et al., 2015; Teoh et al., 2016; Tessoulin et al., 2014) |

Table 2. Small molecule p53 activators in clinical trials.

| Molecule | Clinical Trial | Standalone/Combination | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier | Status | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG7112 (RO5045337) |

|

|

|

Hoffmann-La Roche | |

| RG7338 (RO5503781, Idasanutlin) |

|

|

|

Hoffmann-La Roch | |

| JNJ-26854165 (Serdemetan) |

|

|

|

Johnson & Johnson | |

| MI-773 (SAR405838) |

|

|

|

Sanofi | |

| AMG 232 |

|

|

|

Amgen | |

| NVP-CGM097 |

|

|

|

Novartis | |

| HDM201 |

|

|

|

Novartis | |

| MK-8242 |

|

|

|

Merck Sharp & Dohme | |

| RO6839921 |

|

|

|

Hoffmann- La Roche | |

| DS-3032 |

|

|

|

Daiichi Sankyo | |

| APR-246 (PRIMA-1MET) |

|

|

|

Aprea AB |

Small Molecule Wild-type p53 Activators

The first wild-type p53 activators were devised using a target based approach directed against MDM2-p53 interaction, as several lines of studies have validated MDM2 as an oncotarget (Chene, 2003). For example, a mouse model engineered by Mendrysa et al. to express hypomorphic levels of MDM2 displayed a significant reduction in tumor formation when MDM2 expression was reduced by only 20% (Mendrysa et al., 2006). X-ray crystallography demonstrated precise binding of a peptide region in p53's N-terminal transactivating domain, specifically residues Phe19, Trp23, and Leu26, to ahydrophobic cleft within MDM2's own N-terminal domain, suggesting that this site may be suitable for targeting (Kussie et al., 1996). Indeed, designed peptides have been shown capable of binding this hydrophobic region with higher affinity than p53 and induce an accumulation of p53 protein and activity, further implicating that this interaction may be druggable (Bottger et al., 1997; Chene et al., 2000). In 2004, Vassilev et al. employed high-throughput screening of a library of synthetic compounds and, through surface plasmon resonance, discovered the first class of small molecules, the Nutlin cis-imidazolines, which targeted this region and demonstrated that these Nutlins were able to bind to the MDM2-p53 pocket at nanomolar concentrations and inhibit their interaction (Vassilev et al., 2004). Treatment with Nutlin-3a, a racemic mixture of Nutlin and its specific b enantiomer, on cancer cells expressing wild-type p53 induced non-genotoxic stabilization of p53 protein and subsequent activation of the p53 pathway, which translated in vivo to a reduction in xenograft tumor burden in mice. Optimization of these novel imidazolines by the same group through chemical modifications that improved metabolic stability have led to the development of RG7112 (also known as RO5045337), a more potent MDM2 inhibitor with good pharmacologic characteristics (Tovar et al., 2013; Vu et al., 2013). RG7112 has completed phase I trials as a standalone drug for advanced solid tumors (NCT00559533), liposarcomas (Ray-Coquard et al., 2012) (NCT01143740), and hematological neoplasms (NCT00623870), as well as phase I trials in combination with doxorubicin in soft tissue sarcomas (NCT01605526) and with cytarabine in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) (Andreeff et al., 2016) (NCT01635296). Continued efforts and support from Hoffmann-La Roche led to the discovery of an even more potent and selective MDM2:p53 inhibitor, the pyrrolidine-based molecule RG7388 (also known as RO5503781), which would later be named idasanutlin (Q. Ding et al., 2013). RG7338 has completed phase I clinical trials for AML as a single agent or in combination with cytarabine (NCT01773408) and advanced malignancies (NCT01462175), with one report correlating patient response to MDM2 protein expression (Reis et al., 2016). In addition to preclinical assessment of RG7338 as therapy for neuroblastoma (L. Chen et al., 2015; Lakoma et al., 2015), childhood sarcoma (Phelps et al., 2015), and ovarian carcinoma(Zanjirband, Edmondson, & Lunec, 2016), RG7338 is involved in five other phase I/II studies currently recruiting participants: in combination with obinutuzumab, a novel anti-CD20 mAB, for relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Illidge et al., 2015) (NCT02624986), in combination with Venetoclax, a novel BH3-mimetic/Bcl-2 inhibitor, for patients over 60 with relapsed or refractory AML who are ineligible for cytotoxic therapy (Woyach & Johnson, 2015) (NCT02670044), in combination with dexamethasone and ixazomib citrate, a novel proteasome inhibitor, for refractory multiple myeloma (P. G. Richardson et al., 2015) (NCT02633059), as a standalone drug for polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia (NCT02407080), and in a study designed to compare oral vs intravenous administration of RG7388 in terms of excretion balance, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and bioavailability in patients with solid tumors (NCT02828930). RG7388/Idasanutlin has also been approved for a phase III study comparing its combination with cytarabine or cytarabine alone in patients with relapsed or refractory AML (NCT02545283), making it the small molecule p53 activator that has progressed the furthest in a clinical trial setting. The fact that even more novel MDM2:p53 inhibitors have been discovered based on RG7112 and RG7388, a series of spiroindolinones with RO5353, RO2468, and RO8994 as lead compounds, provides testimony that the field of developing small molecule p53 activators continues to burgeon (Z. Zhang, X. J. Chu, et al., 2014; Z. Zhang, Q. Ding, et al., 2014).

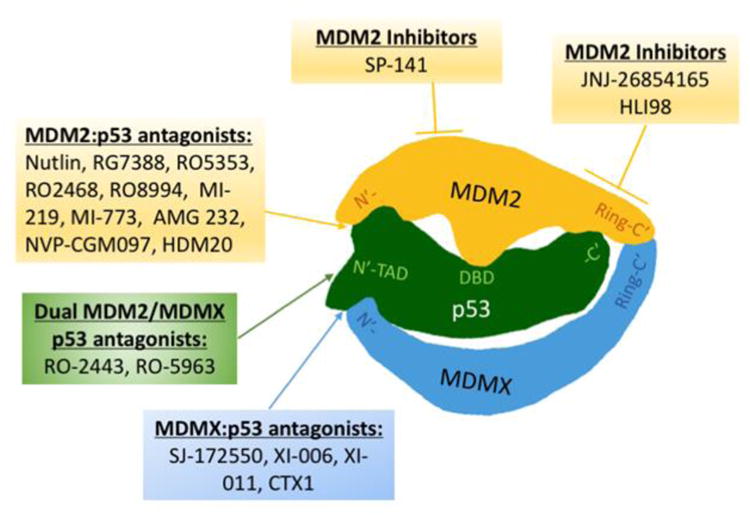

The relative success of Nutlin-3a and its successors served as a proof of principle that rational design of MDM2 inhibitors is an attractive and viable option against cancers that harbor wild-type p53, which encompasses roughly 50% of all cancers. Several other small molecules have since been developed, targeting various aspects of the p53-MDM2-MDMX pathway [Figure 1]. For example, some molecules discovered via high-throughput screening of MDM2's C-terminal RING finger domain target MDM2-mediated ubiquitination of p53, as JNJ-26854165 (also known as serdemetan) blocks the MDM2-p53 complex from interacting with the proteasome and has progressed to phase I clinical trials for advanced stage or refractory tumors (Chargari et al., 2011; Kojima, Burks, Arts, & Andreeff, 2010;Patel & Player, 2008; Tabernero et al., 2011) (NCT00676910), while HLI98s and related 5-deazaflavin compounds directly inhibit MDM2 ubiquitin ligase activity (Dickens et al., 2013; Roxburgh et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2005). p53-independent cytotoxicity is associated with both molecules, a finding perhaps not unexpected, as MDM2 has been reported to have substrates other than p53 and functions other than ubiquitination (Bohlman & Manfredi, 2014; Z. Zhang & Zhang, 2005). However, targeting MDM2 itself may be an attractive option in cancers that overexpress MDM2, as MDM2 has been shown to have oncogenic functions independent of p53, such as inhibition of apoptosis (L. Gu et al., 2009) and regulation DNA replication (Vlatkovic et al., 2000) and global genome stability (Bouska & Eischen, 2009). With this concept in mind, the Zhang laboratory have recently developed SP-141, a pyirdo[b]indole, that directly binds to MDM2 and destabilizes it by promoting its ubiquitination and have demonstrated its efficacy in breast cancer cells and xenografts models with both wild-type p53 and mutant p53 (W. Wang et al., 2014). Other molecules were designed to target MDMX, as inhibition of MDM2 may be insufficient to overcome tumor progression in cancers such as melanomas (Gembarska et al., 2012), retinoblastomas (Laurie et al., 2006), and breast carcinomas (Danovi et al., 2004) that highly express MDMX. SJ-172550, an imidazoline derivative identified by a fluorescence polarization assay, was the first small molecule reported to inhibit MDMX and was shown to block MDMX from interacting with p53 and synergize with Nutlin against retinoblastoma cells expressing MDMX and MDM2 (Bista et al., 2012; Reed et al., 2010). Reporter-based screening identified two other MDMX inhibitors, XI-006 (also called NSC207895), a benzofuroxan derivative (H. Wang, Ma, Ren, Buolamwini, & Yan, 2011), and XI-011 (also called NSC146109), a pseudourea derivative (H. Wang & Yan, 2011). Both XI-006 and XI-011 induced apoptosis in breast cancer cells and, similar to SJ-172550, synergized with Nutlin in an MDMX and MDM2 dependent manner. Additional studies demonstrated XI-006's and XI-011's efficacy in Ewing sarcoma (Pishas et al., 2015) and head and neck cancer cells (Roh, Park, & Kim, 2014), respectively. Subsequent efforts in constructing molecules against MDMX have yielded CTX1, identified by a cell-based screen, which demonstrated efficacy in and synergy with Nutlin against a panel of cancer cells containing wild-type p53 and in a mouse xenograft model using primary human AML cells (Karan et al., 2016). Vassilev et al. have also discovered RO-2443 and RO-5963, an indolyl hydantoin series capable of imposing dimerization of MDM2 and MDMX, preventing either of their interactions with p53 (Graves et al., 2012). RO-5963, the analog with superior pharmacokinetic properties, serves as the lead compound of this series of dual MDM2-MDMX inhibitors and has been shown capable of overcoming apoptotic resistance to Nutlin in cells overexpressing MDMX (Graves et al., 2012).

Figure 1. MDM2/MDMX Inhibitors.

MDM2:p53, MDMX:p53, and dual MDM2/MDMX:p53 antagonists primarily function as protein:protein inhibitors, disrupting the interaction between the N-terminal transactivating domain of p53 and the N-terminal p53-binding domains of its principle regulators MDM2 and MDMX. MDM2 inhibitors function by directly inhibiting MDM2 activity. Both JNJ-26854165 and HLI98 bind to MDM2's RING finger domain; JNJ-26854165 blocks proteasome interaction with MDM2:p53 complex and HLI98 inhibits MDM2 ubiquitin ligase activity. SP-141 binds to the N-terminal p53-binding domain through an undetermined mechanism destabilizes MDM2.

Structure-based design and improved computational modeling allowed the Wang laboratory to design a series of p53 activators based on Nutlin's binding to MDM2 (K. Ding et al., 2006). They discovered that the spiro-oxindole MI-219 binds to MDM2 by mirroring its interaction with p53 at residues Phe19, Trp23, and Leu26 within its hydrophobic cleft in a manner similar to the Nutlin compounds, except with substantially higher affinity (Shangary et al., 2008; Y. Zhao, Liu, et al., 2013). Optimization of MI-219's pharmacologic properties to make the molecule more clinically applicable led to the development of MI-888 (Y. Zhao, Yu, et al., 2013) and MI-773 (also called SAR405838) (S. Wang et al., 2014), the latter of which is currently in Phase I clinical trials in patients with dedifferentiated liposarcomas (NCT01636479). Interestingly, a recent report involving patient tumors from the ongoing clinical trial with MI-773 linked resistance to treatment to an increase in TP53 mutations, a correlation regarding MDM2 inhibitors previously only made in vitro and certainly an observation that requires careful study in regards to utilizing wild-type p53 activators (Aziz, Shen, & Maki, 2011; J. Jung et al., 2016). Structure-based design has also led to the development of several other molecules that target MDM2's hydrophobic cleft using various chemical scaffolds, such as methylbenzo-amines (Dudgeon et al., 2010), imidazole-indoles (Czarna et al., 2010), isoindolinones (Hardcastle et al., 2006; Hardcastle et al., 2011; Riedinger et al., 2011), pyrrolopyrimidines (Lee et al., 2011), sulphonamides (Galatin & Abraham, 2004), and benzodiazepines (Z. Yu et al., 2014; Zhuang et al., 2011), which all demonstrate nanomolar binding affinities to MDM2 and with one pyrrolidinone exhibiting dual MDM2/MDMX activity (Zhuang et al., 2012) and one pyrrolopyrazole seemingly active against both MDM2 and the NF-κB complex (Zhuang et al., 2014), a different cancer-related pathway (DiDonato, Mercurio, & Karin, 2012). Perhaps most promising are a series of piperidonones (AM-8553, AM-7209, AMG 232) and morpholinones (AM-8735) developed from Amgen laboratories that exhibit exceptional pharmacokinetic properties, such as low clearance rate, long half-life, and high oral bioavailability (Gonzalez-Lopez de Turiso et al., 2013; Gonzalez, Eksterowicz, et al., 2014; Rew et al., 2012; Rew et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014). One piperidonone, AMG 232, is currently recruiting for Phase I/II clinical trials for advanced solid tumors or multiple myeloma as a standalone drug (NCT01723020), AML in combination with trametinib, a MEK1/2 inhibitor, (Mandal, Becker, & Strebhardt, 2016) (NCT02016729), and metastatic melanoma in combination with trametinib and dabrafenib (NCT02110355). Researchers from Amgen laboratories continue to make chemical modifications to further optimize lead compounds and improve both potency and pharmacokinetic properties (Gonzalez, Li, et al., 2014; M. Yu et al., 2014). Novartis laboratories have also developed a novel MDM2:p53 protein inhibitor, a dihydroisoquinolinone derivative called NVP-CGM097, which, in addition to in vitro efficacy studies for AML and uveal melanoma, is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials in patients with selected advanced solid tumors (Carita et al., 2016; Holzer et al., 2015; Weisberg et al., 2015) (NCT01760525). Analysis of patient tumors by intersecting high-throughput cell line sensitivity data with genomic data from the ongoing trial has identified distinct p53 target genes that predict sensitivity to NVP-CGM097, a genetic signature that can be used for selection of patients that would be most sensitive to treatment with NVP-CGM097 or other MDM2 antagonists (Jeay et al., 2015). The Novartis laboratories have also designed a new MDM2 inhibitor with a pyrazolopyrrolidinone core based on MDM2's structure when bound to dihydroisoquinolinones and have discovered HDM201 (Furet et al., 2016), which has likewise entered phase I clinical trials for tumors with wild-type p53 (NCT02143635), for liposarcomas in combination with LEE011 (also known as Ribociclib), a novel CDK4/6 inhibitor (Infante et al., 2016) (NCT02343172), and as part of a personalized neuroblastoma clinical trial that will apply next generation sequencing on biopsies of patient tumors, followed by treatment with either trametinib, certinib (an ALK inhibitor) (Shaw et al., 2014), or HDM201, depending on the deep sequencing results (NCT02780128). Another lead small molecule developed with support from Merck and whose structure has not been disclosed is MK-8242 (Kang et al., 2016), which has demonstrated efficacy in the Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) (Houghton et al., 2007), an established panel of childhood cancer xenografts and cell lines used to test novel therapeutic agents, and has entered phase I clinical trials for AML (Ravandi et al., 2016) (NCT01451437) and advanced solid tumors (NCT01463696). Other molecules currently in clinical trials are RO6839921 for advanced cancers (Roche; NCT02098967) and DS-3032 (Daiichi Sankyo) for several hematological malignancies (NCT02319369), relapsed and refractory myeloma (NCT02579824), and advanced solid tumors and lymphomas (NCT01877382).

Whereas many of the aforementioned molecules were developed using high-throughput screening and structure-based design, an alternative strategy employs cell-based screening, utilizing reporter cell lines to phenotypically identify small molecules that, through interacting with p53 regulators or p53 itself, can transcriptionally activate p53 (Berkson et al., 2005; Zheng, Chan, & Zhou, 2004). This approach offers advantages in that the reporter cells are adaptable to high-throughput screening and molecules selected are typically cell permeable and active at concentrations reasonable for further in vivo testing (Brown, Lain, Verma, Fersht, & Lane, 2009). The challenge, however, is in uncovering the mechanisms of action by which hit compounds activate p53, as optimization of lead compounds would require elucidation of molecular targets, which, incidentally, may also uncover novel p53 regulatory factors (Schenone, Dancik, Wagner, & Clemons, 2013). Unfortunately, many compounds identified have unknown targets or have mechanisms of action that may be associated with general toxicity, such as DNA intercalation (Gottifredi, Shieh, Taya, & Prives, 2001), inhibition of ribosomal RNA synthesis (Choong, Yang, Lee, & Lane, 2009; Gottifredi et al., 2001), and disruption of mitosis (Staples et al., 2008).

A small molecule series discovered through cell-based screening and whose mechanism of action has been determined are tenovin-1 and tenovin-6 (Lain et al., 2008). Lain et al., once confirming that these tenovins were cytotoxic against a panel of cell lines and reduced melanoma xenograft tumor burden, utilized a yeast-based genetic assay and identified SirT1 and SirT2, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent protein deacetylases of the sirtuin family (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog), as molecular targets. Not surprisingly, p53 is a known substrate of SirT1 (Langley et al., 2002; Luo et al., 2001). Acetylation of p53 is indispensible for its activation and is correlated with augmented site-specific DNA binding (Luo et al., 2004), particularly for genes associated with induction of apoptosis (Sykes et al., 2006). Interesting, although SirT2 primarily resides in the cytoplasm (North, Marshall, Borra, Denu, & Verdin, 2003) and its status as either a tumor suppressor (H. S. Kim et al., 2011) or oncoprotein (P. Y. Liu et al., 2013) is controversial, many studies have observed anti-tumorigenic effects through SirT2 inhibition (Cheon, Kim, Choi, & Kim, 2015; Jing et al., 2016; Peck et al., 2010; Y. Zhang et al., 2009). Germane to these reports, AEM1, a SirT2 specific inhibitor, was identified as a novel p53 acetylating agent that upregulated p53 target genes and sensitized non-small cell lung cancer cell lines to etoposide (Hoffmann, Breitenbucher, Schuler, & Ehrenhofer-Murray, 2014). Validation of SirT1 and SirT2 as targets of tenovin-1/6 and AEM1 highlights the relevance these small molecules hold both for broadening our understanding of sirtuin regulation of p53 and as potential therapeutic agents. An example of how target validation can facilitate drug improvement involves the polyketide natural product leptomycin B (LMB, also known as elactocin), which was found to bind and inhibit CRM1 (chromosome maintenance 1, also known as exportin 1 or Xpo1), a nuclear export protein responsible for exporting several cancer-related transcription factors including p53 (Kudo et al., 1999; Lecane, Kiviharju, Sellers, & Peehl, 2003; Smart et al., 1999). Despite promising in vitro data, LMB was ultimately determined to have too narrow of a therapeutic window to be clinically viable (Newlands, Rustin, & Brampton, 1996). However, a new series of nuclear export inhibitors (NEIs) based off LMB's structure are reported to have both increased potency and dramatically reduced toxicity in preclinical xenograft models (Mutka et al., 2009).

Another search of small molecule p53 activators performed by the Lu lab by employing computational structure-based screening (Morris, Huey, & Olson, 2008) to initially screen for small molecules that could distinguish between MDM2 and MDMX binding sites on p53 followed by cell-based screening of top candidates for both cytotoxicity against cancer cells and p53 activation led to the identification of Inauhzin (10-[2-(5H-[1,2,4]triazino[5,6-b]indol-3-ylthio)butanoyl]-10H-phenothiazine), abbreviated as INZ) as a potent p53 activator (Q. Zhang, S. X. Zeng, et al., 2012). Whole genome microarray analysis and RT-qPCR validation of INZ-treated cells with or without p53 indicates that INZ has a global effect on the human p53-responsive transcriptome (Liao, Zeng, Zhou, & Lu, 2012). INZ suppresses the growth of human xenograft tumors harboring wild-type p53, synergizes with Nutlin-3a to activate p53 and suppress tumor growth, as well as sensitizes the tumor suppressive effects of chemotherapeutic agents cisplatin and doxorubicin (Y. Zhang, Zhang, Zeng, Hao, & Lu, 2013; Y. Zhang, Zhang, Zeng, Mayo, & Lu, 2012). INZ showed no cytotoxicity to normal human fibroblasts and no induction of general genotoxicity based on DNA binding, cellular p53 phosphorylation, and γH2AX assays. Preclinical toxicity studies in animals have established that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of INZ well exceeds doses effective for tumor reduction, and do not reveal any significant changes in biochemical or pathologic parameters (Q. Zhang, Zeng, & Lu, 2015). Examination of INZ and compounds with similar structures reveal two functional moieties essential for activity: triazino[5,6-b]indol (arbitrarily named G1) and phenothiazine (G2). Continued structure-activity relationship (SAR) analyses of these two moieties by observing the effects on cytotoxicity of chemical modifications at various positions have led to the identification of a second generation analog, 1-acridin-INZ-alcohol, later christened INZ-c, which demonstrated up to 10-fold more potency in vitro (Q. Zhang, Ding, Zeng, Ye, & Lu, 2012).

INZ extends the half-life of p53 from 30 minutes to more than three hours and protects p53 from MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation without directly interfering with MDM2 ubiquitylation activity (Q. Zhang, S. X. Zeng, et al., 2012). Functional studies to elucidate the mechanisms by which INZ stabilizes p53 have led to the identification and validation of two independent cellular targets: SirT1, the NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase, and IMP dehydrogenase 2 (IMPDH2), an enzyme that catalyzes the rate limiting step in de novo guanine nucleotide biosynthesis (Q. Zhang et al., 2014; Zimmermann, Spychala, &Mitchell, 1995). On the one hand, INZ directly binds to and inhibits SirT1, inducing acetylation of p53 at lysine residue 382 (Vaziri et al., 2001), thereby enhancing sequence specific binding and protecting p53 from MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation (Li, Luo, Brooks, & Gu, 2002) [Figure 3]. By a different mechanism, INZ also binds to and inhibits IMPDH2, prompting a depletion in cellular GTP levels and triggering the translocation and destabilization of nucleostemin (NS), a nucleolar GTP-binding protein important for rRNA processing, from the nucleolus to the nucleoplasm (Tsai & McKay, 2005). The subsequent ribosomal stress as a consequence of NS depletion enhances the binding of ribosomal proteins RPL11 and RPL5 with MDM2 while inhibiting MDM2's interaction with p53 (Dai, Sun, & Lu, 2008; Lo, Dai, Sun, Zeng, & Lu, 2012), again resulting in the protection of p53 from MDM2-mediated ubiquitylation. Interestingly, both of INZ's targets are highly associated with cancer. SirT1 has been found to be overexpressed in several human cancers such as lung, colon, and prostate carcinomas, as its repressor hypermethylated-in-cancer 1 (HIC-1) is frequently inactivated (W. Y. Chen et al., 2005; Fleuriel et al., 2009; Fukasawa et al., 2006; Tseng, Lee, Hsu, Tzao, & Wang, 2009). IMPDH2 is similarly highly expressed in proliferating and neoplastic tissues and has been targeted for various forms of therapy (L. Chen & Pankiewicz, 2007; J. J. Gu et al., 2003; Ishitsuka et al., 2005; Malek, Boosalis, Waraska, Mitchell, & Wright, 2004). An additional report reveals that the second generation analog INZ-C reduces c-MYC levels in lymphoma cells independently of p53 (J. H. Jung et al., 2015), an encouraging finding as dual targeting of both p53 and c-MYC was very recently shown to be an effective strategy against leukemic stem cells (Abraham et al., 2016). As mentioned above, SirT1 is also the inhibited by the tenovin series. However, studies indicate that INZ specifically targets SirT1 and not SirT2, unlike tenovin-1/tenovin-6, with a higher degree of potency, while remaining less toxic to normal cells. Furthermore, INZ independently targets a second cancer-related pathway in IMPDH2. These studies identify INZ as a candidate for a new paradigm of anti-cancer reagents that can target multiple pathways which may more efficiently eradicate tumor cells and overcome any drug resistance possibly developed against a singular molecule-target drug, although more intensive preclinical studies, including its optimization and bioavailability in different cancer model systems, are still in progress to further pursue this small molecule candidate.

Figure 3. Indirect p53 activators.

Tenovin-6 inhibits both sirtuin 1 (SirT1) and sirtuin 2 (SirT2) deacetylases, but with higher affinity for SirT1, while AEM1 selectively inhibits SirT2. Inhibition of SirT1/SirT2 promotes the acetylation of p53, simultaneously enhancing site-specific DNA binding while protecting it from MDM2-mediated ubiquitination. Inauhzin targets both SirT1 and IMP dehydrogenase 2 (IMPDH2). Inhibition of IMPDH2 causes a decrease in cellular GTP levels and subsequent destabilization of nucleostemin (NS) protein. The resultant induction of ribosomal stress frees ribosomal protein L5 (RPL5) and ribosomal protein L11 (RPL11) from ribosomes, allowing them to bind MDM2, protecting p53 from MDM2

The emergence of CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing technology has improved our ability to identify and validate drug targets, as well as understand the genetic and epigenetic mechanisms that govern drug resistance (Hsu, Lander, & Zhang, 2014; Kasap, Elemento, & Kapoor, 2014). CRISPR's impact on research regarding p53 activators can be illustrated by a recent study concerning RITA (reactivation of p53 and induction of tumor cell apoptosis), a small molecule discovered by the Selivanova laboratory via cell-based screening that was initially thought to activate wild-type p53 by binding to p53's N-terminal domain and disrupting interaction with MDM2 (Issaeva et al., 2004). Grinkevich et al. showed that RITA's propensity to induce apoptosis relied on a dose-dependent and a seemingly p53-dependent transcriptional repression of key oncogenic pathways, followed by transactivation of pro-apoptotic genes (Grinkevich et al., 2009). However, NMR studies found that RITA did not interfere with p53-MDM2 association (Krajewski, Ozdowy, D'Silva, Rothweiler, & Holak, 2005) and subsequent studies demonstrating its activity in p53 mutant cells suggested that RITA can induce a wild-type conformation to mutant p53 (Burmakin, Shi, Hedstrom, Kogner, & Selivanova, 2013; Weilbacher, Gutekunst, Oren, Aulitzky, & van der Kuip, 2014; C. Y. Zhao, Grinkevich, Nikulenkov, Bao, & Selivanova, 2010). Wanzel et al. applied CRISPR-Cas9-based target validation and observed that RITA's activity was not actually dependent on p53 protein, but rather on DNA damage; i.e. RITA functions not as a p53 activator, but as a genotoxic, DNA cross-linking drug (Wanzel et al., 2016). The group further determined that sensitivity to RITA is contingent on the mTOR-regulated Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway, and that cells resistant to RITA share cross-resistance to other DNA cross-linking agents, such as cisplatin (H. Kim & D'Andrea, 2012; C. Shen et al., 2013).

Small Molecules Targeting Mutant p53

Although the small molecules discussed above represent potential therapeutic options for cancers that express wild-type p53 (RITA being the potential exception), they offer little benefit for cancers that harbor mutations in the TP53 gene, a particularly vexing problem for certain tumor profiles, such as pancreatic adenocarcinoma and high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC), which sport a harrowing 70% and 97% TP53 mutation rate, respectively (Ahmed et al., 2010; Ryan, Hong, & Bardeesy, 2014). As such, considerable effort has been placed into developing molecules that may reactivate or reinstate wild-type function in tumors with mutated p53, an endeavor complicated by the variety of mutations in TP53 that have been documented, for although the majority of mutations occur in the so called “hot-spots” (R175, G245, R248, R249, R273, and R282), TP53 missense mutations can be found distributed throughout the protein, with each residue from codon 50 to 360 having at least one reported mutation (Leroy et al., 2013). Even hot-spot mutants result in different conformational profiles (Bullock & Fersht, 2001; Bullock, Henckel, & Fersht, 2000). Strict DNA-contact mutants (e.g. R273H) significantly reduce wild-type DNA binding, while only having a slight effect on p53 thermostability (Joerger & Fersht, 2007). In contrast, certain structural mutants like G245S, R249S, and R282W exhibit varying degrees of loss in wild-type binding and increased thermoinstability (Joerger & Fersht, 2007). Further still, mutants that affect zinc binding (e.g. R175H) dramatically reduce both canonical DNA binding and thermostability (Joerger & Fersht, 2007).

Consequently, the mechanisms of action and specificity of proposed small molecules against mutant p53 are varied [Figure 2]. X-ray crystallography reveals that the Y220C mutant results in the formation of a solvent-accessible cleft that destabilizes p53's central domain by 4kcal/mol, but leaves the general structure of the DNA-binding domain unchanged, delineating this cleft as an attractive druggable site (Joerger, Ang, & Fersht, 2006). Using virtual screening and rational drug design, Fersht et al. discovered two small molecules, the carbazole derivative PK083 and the pyrrol-pyrazole derivative PK7088, that bind to this cleft and stabilize the Y220C mutant by raising the melting temperature and retarding the rate of thermal denaturation (Boeckler et al., 2008; X. Liu et al., 2013). PK7088 restores wild-type folding of p53 in cells expressing the Y220C mutation and activates downstream p53-signalling, indicating that these compounds may have mutant-specific clinical relevance. PK7088 also synergizes with Nutlin in inducing p53 downstream target p21 in cells that were otherwise insensitive to Nutlin treatment, a finding congruous with PK7088's mechanism of refolding Y220C p53 mutants into wild-type conformation, thereby allowing Nutlin to be effective (X. Liu et al., 2013).

Figure 2. Mutant-to-wild type p53 converting activators.

ZMC1 is a zinc ionophore and chelator that provides the R175H mutant enough zinc in its local environment to overcome its reduced affinity for Zn2+ and induce wild-type folding. PK7088 binds to a cleft present in the Y220C mutant, increasing its thermal stability and promoting wild-type folding. Chemotin (CTM) first binds to heat shock protein 40kD (Hsp40), which forms a complex with p53-R175H and through an undefined mechanism promotes wild-type conformational change. P53R3 and SCH529074 bind to p53's DNA binding domain (DBD) and through an undefined mechanism function in a chaperone-like manner to induce wild-type folding of multiple forms of p53 mutants. APR-246 is metabolized to methylene quinuclidinone (MQ), which forms adducts with cysteine residues in p53's DBD, promoting and stabilizing wild-type conformation.

Another mutant-specific molecule, the thiosemicarbazone ZMC1 (also known as NSC319726), selectively targets the R175H mutant and was discovered by the Carpizo laboratory (X. Yu, Vazquez, Levine, & Carpizo, 2012). In an attempt to deviate from traditional screening methods, they developed a methodology that screened the NCI panel of 60 tumor derived cell lines (NCI60), with the goal of identifying compounds that target mutant p53 in cell lines independent of genetic background and tissue origin, an approach that takes into account the heterogeneous nature of cancers (Shoemaker, 2006). The R175H mutant, one of the most common p53 mutations found in cancer, dramatically reduces the central domain's affinity for Zn2+, resulting in a loss of activity even at subphysiologic temperatures (Joerger & Fersht, 2007). ZMC1 functions as both a zinc ionophore, binding extracellular zinc and diffusing it across the plasma membrane, and a metallochaperone, a zinc chelator that serves as a reservoir of available Zn2+, providing the R175H mutant enough zinc to overcome its lowered affinity while not subjecting cells to toxic levels (Blanden, Yu, Wolfe, et al., 2015; X. Yu et al., 2014). Indeed, thiosemicarbazones have been investigated as potential anti-cancer agents and have been shown to generate reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress by inhibiting the iron-dependent enzyme ribonucleotide reductase, but require doses highly toxic to normal cells (D. R. Richardson et al., 2006; Y. Yu, Wong, Lovejoy, Kalinowski, & Richardson, 2006). In contrast, ZMC1 reinstates p53 wild-type conformation of R175H mutants and canonical p53 signaling in cells and reduces mouse tumor xenograft burden at doses that present no systemic toxicity to mice or normal cells. Interestingly, ZMC1 requires generation of reactive oxygen species to be fully effective, as treatment with a reducing agent attenuates its apoptotic ability, suggesting that ZMC functions by a dual mechanism: facilitation of wild-type p53 conformation, followed by oxidative stress that can signal through the now active p53 pathway (Blanden, Yu, Loh, Levine, & Carpizo, 2015). Notably, ZMC1 functions differently than most p53 reactivators that attempt to bind to mutant p53 and induce conformational changes. ZMC1 has no specific binding to p53's central domain and instead promotes changes in the local environment that enables p53 to properly fold.

Additional small molecules have also been developed targeting different aspects of mutant p53. RETRA (Kravchenko et al., 2008), NSC59984 (S. Zhang et al., 2015), and prodigiosin (Hong et al., 2014) disrupt GOF-mediated inhibition of p73, driving p73-dependent tumor suppression, and have both exhibited activity against a panel of mutant p53 cell lines and mouse xenografts [Figure 3]. A recent report provides evidence that prodigiosin can target colorectal cancer stem cells (CRCSCs) (Prabhu et al., 2016), a subpopulation of cells that have been implicated in colorectal cancer initiation and maintenance, metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy (O'Brien, Pollett, Gallinger, & Dick, 2007; Pang et al., 2010; Todaro et al., 2007). Prodigiosin downregulates ΔNp73, the oncogenic N-terminally truncated isoform of p73 (Wilhelm et al., 2010), while upregulating full length p73, providing a mechanistic rationale for targeting the p53-p73 axis in CRCSCs. Other small molecules with less defined mechanisms of action have also been developed. The quinazolines P53R3 (Weinmann et al., 2008) and SCH529074 (Demma et al., 2010) bind p53's DNA binding domain and while the styrylquinazoline CP-31398 displays no such interaction (Rippin et al., 2002; W. Wang, Takimoto, Rastinejad, & El-Deiry, 2003), all three compounds appear capable of functioning with a chaperone-like capacity to refold different p53 mutants, stabilize wild-type conformation, and promote canonical DNA promoter binding [Figure 2]. Uncovering the mechanisms behind these mutant p53 “chaperones” may lead to lead to more novel approaches to mutant p53 wild-type reactivation. Interestingly, another small molecule chetomin (CTM) is a fungal dithiodiketopiperazine metabolite that has already displayed anti-tumor effects via inhibition of HIF-1α (Kessler et al., 2010; Viziteu et al., 2016) was recently shown to reactivate the R175H mutant by binding to the chaperone protein Hsp40 (heat shock protein 40kD), raising its binding affinity for p53-R175H, which induces a wild-type like conformational change (Hiraki et al., 2015). Whether other molecules can be designed to harness heat shock proteins to bind and convert mutant p53 to wild-type remains to be seen.

The most promising small molecule mutant reactivator to date and the only one of this kind to advance to clinical trials is APR-246 (also known as PRIMA-1MET), as APR-246 has completed a phase I trial for refractory hematologic prostate cancer (NCT00900614) and is currently recruiting for a study examining its efficacy in combination with carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride in high grade serous ovarian cancer (NCT02098343). The original compound PRIMA-1 (for p53 reactivation and induction of massive apoptosis) was identified by Bykov et al. via a cell-based screen and was shown to preferentially induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cells expressing different mutant forms of p53, including hot-spot mutants R273, R175, R282, R248, and G245, and promote refolding into wild-type conformation with restoration of canonical DNA-binding and transcriptional activation (Bykov et al., 2002). Optimization of potency and pharmacologic properties led to the development of a methylated form of PRIMA-1 (PRIMA-1MET), subsequently christened APR-246 (Bykov et al., 2005). Remarkably, APR-246 can also reactivate mutant forms of p53 paralogs p63 and p73 (Rokaeus et al., 2010). While mutations in p63 are rarely found in cancers, p63 missense mutations in its own DNA-binding domain appear to play a prominent role in ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft syndrome (EEC syndrome), an autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized split-hand or split-foot malformations (ectrodactyly), facial clefting, and a myriad of deficits related to ectodermal dysplasia, such as absence of sweat glands and subsequent hypohydrotic symptoms, conductive hearing loss, and speech impairment (van Bokhoven et al., 2001). Indeed, APR-246 rescues impaired keratinocyte and induced pluripotent stem cell differentiation driven by p63 mutations in cells derived from EEC patients (Shalom-Feuerstein et al., 2013; J. Shen et al., 2013). Furthermore, as mutant p53 GOF can inhibit both p63 and p73, APR-246 restoration of p73 activity has been shown to be a potential treatment avenue for multiple myeloma (Saha, Jiang, Yang, Reece, & Chang, 2013; Teoh et al., 2016). APR-246's ability to reactivate multiple distinct mutants in p53 and even p63/p73 signifies it operates by a mechanism of action common to each of these mutants. Lambert et al. demonstrated that APR-246 is actually a prodrug that is converted to methylene quinuclidinone (MQ), a Michael acceptor that forms adducts with thiol groups in proteins (Lambert et al., 2009). p53's core domain contains 10 cysteine residues, of which four (Cys182, Cys229, Cys242, and Cys277) are exposed on the surface in wild-type conformation (Cho et al., 1994). More cysteines are presumably exposed in unfolded or mutant p53, which can explain why APR-246 has higher affinity for and can more extensively modify mutant p53 compared to wild-type p53 (Lambert et al., 2009). APR-246 therefore promotes mutant p53 folding into wild-type conformation by covalently modifying cysteine residues in the core domain, again emphasizing the fact that there appears to be several viable mechanisms to reactivate mutant p53 [Figure 2]. Interestingly, APR-246, in line with its thiol-modifying properties, targets thiol-containing components of the cellular redox system. APR-246 inhibits thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1), an enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of thioredoxin using NAPDH, via its selenocysteine residue and effectively converts TrxR1 from a reducing enzyme to a dedicated NAPDH oxidase (Arner, 2009; Peng et al., 2013). APR-246 also reduces the overall cellular availability of the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) by binding its cysteine residues (Tessoulin et al., 2014). Both of these mechanisms contribute to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and may explain APR-246's observed apoptotic activity independent of p53 (Grellety et al., 2015; Sobhani, Abdi, Manujendra, Chen, & Chang, 2015). Because glutathione has been implicated in resistance to platinum-containing chemotherapeutic reagents (Amable, 2016), APR-246 can mitigate this resistance and indeed shows synergy not only with cisplatin, but also 5-fluorouracil and doxorubicin (Fransson et al., 2016; Mohell et al., 2015). APR-246 thereforehas a dual mechanism of action – mutant p53 reactivation and ROS generation – and, in a similar vein to other dual-targeting molecules, is a candidate for a new paradigm of anti-cancer reagents that can target multiple pathways [Figure 4].

Figure 4. Inhibitors of Mutant p53's Gain of Function.

RETRA, NSC59984, and prodigiosin reverse mutant p53 gain-of-function (GOF) inhibition of tumor suppressor and family member p73. APR-246 metabolite methylene quinuclidinone (MQ) also forms adducts with thioredoxin reductase 1 (TrxR1) and glutathione (GSH), generating reactive oxygen spieces (ROS) and serves as a second mechanism of action.

Conclusion

Decades of research have been dedicated to unraveling the function and regulation of p53, the tumor suppressor so integral to preventing tumorigenesis that it has become known as the guardian of our genome, and leave little doubt that reviving p53 would have prodigious implications for the treatment of human cancers. p53 represents a rather unique translational target and is reflected in the diversity of the mechanisms of action of the many proposed small molecules. Protein-protein interaction inhibitors in the form of MDM2:p53, MDMX:p53, and dual MDM2/MDMX:p53 antagonists, molecular chaperones that refold mutant p53 to reinstate and stabilize wild-type activity, and molecules that target other regulators of p53, such as SirT1, have all been developed with the singular goal of activating p53. Tremendous progress has been made since the inaugural discovery of Nutlin, the first small molecule targeted activator of p53 in 2004, as several candidates have completed initial testing in clinical trials with many more on the way. In particular, RG7388/Idasanutlin has progressed the furthest and has entered a phase III trial. Our persistent efforts to elucidate and enrich our understanding of the molecular mechanisms that govern p53 continue to provide us with the tools necessary to reinvent and innovate new forms of therapy that will one day offer real benefit for patients.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by NIH-NCI grants R01CA095441, R01CA172468, R01CA127724, R21CA190775, and R21CA201889 as well as Lady Leukemia League foundation to Hua Lu and Shelya X Zeng.

Abbreviations

- AML

acute myelogenous leukemia

- CML

chronic myelogenous leukemia

- INZ

inauhzin

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham SA, Hopcroft LE, Carrick E, Drotar ME, Dunn K, Williamson AJ, et al. Holyoake TL. Dual targeting of p53 and c-MYC selectively eliminates leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2016;534(7607):341–346. doi: 10.1038/nature18288. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed AA, Etemadmoghadam D, Temple J, Lynch AG, Riad M, Sharma R, et al. Brenton JD. Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. J Pathol. 2010;221(1):49–56. doi: 10.1002/path.2696. Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amable L. Cisplatin resistance and opportunities for precision medicine. Pharmacol Res. 2016;106:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.01.001. Research Support, N.I.H., Intramural Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato I. Cancer therapy. Hope for a magic bullet that moves at the speed of light. Science. 1993;262(5130):32–33. doi: 10.1126/science.8211126. News. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreeff M, Kelly KR, Yee K, Assouline S, Strair R, Popplewell L, et al. Kojima K. Results of the Phase I Trial of RG7112, a Small-Molecule MDM2 Antagonist in Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):868–876. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0481. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arner ES. Focus on mammalian thioredoxin reductases--important selenoproteins with versatile functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(6):495–526. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.01.014. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz MH, Shen H, Maki CG. Acquisition of p53 mutations in response to the non-genotoxic p53 activator Nutlin-3. Oncogene. 2011;30(46):4678–4686. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.185. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste N, Friedlander P, Chen X, Prives C. The proline-rich domain of p53 is required for cooperation with anti-neoplastic agents to promote apoptosis of tumor cells. Oncogene. 2002;21(1):9–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205015. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baselga J. Targeting tyrosine kinases in cancer: the second wave. Science. 2006;312(5777):1175–1178. doi: 10.1126/science.1125951. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S, Klein C, Muller L, Hansen S, Buchner J. p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state. J Mol Biol. 2002;322(5):917–927. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkson RG, Hollick JJ, Westwood NJ, Woods JA, Lane DP, Lain S. Pilot screening programme for small molecule activators of p53. Int J Cancer. 2005;115(5):701–710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20968. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat KP, Itahana K, Jin A, Zhang Y. Essential role of ribosomal protein L11 in mediating growth inhibition-induced p53 activation. EMBO J. 2004;23(12):2402–2412. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600247. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieging KT, Attardi LD. Deconstructing p53 transcriptional networks in tumor suppression. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22(2):97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.10.006. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bista M, Smithson D, Pecak A, Salinas G, Pustelny K, Min J, et al. Guy RK. On the mechanism of action of SJ-172550 in inhibiting the interaction of MDM4 and p53. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037518. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanden AR, Yu X, Loh SN, Levine AJ, Carpizo DR. Reactivating mutant p53 using small molecules as zinc metallochaperones: awakening a sleeping giant in cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20(11):1391–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.07.006. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanden AR, Yu X, Wolfe AJ, Gilleran JA, Augeri DJ, O'Dell RS, et al. Loh SN. Synthetic metallochaperone ZMC1 rescues mutant p53 conformation by transporting zinc into cells as an ionophore. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87(5):825–831. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.097550. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckler FM, Joerger AC, Jaggi G, Rutherford TJ, Veprintsev DB, Fersht AR. Targeted rescue of a destabilized mutant of p53 by an in silico screened drug. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(30):10360–10365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805326105. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlman S, Manfredi JJ. p53-independent effects of Mdm2. Subcell Biochem. 2014;85:235–246. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9211-0_13. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottger A, Bottger V, Sparks A, Liu WL, Howard SF, Lane DP. Design of a synthetic Mdm2-binding mini protein that activates the p53 response in vivo. Curr Biol. 1997;7(11):860–869. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00374-5. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouska A, Eischen CM. Mdm2 affects genome stability independent of p53. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1697–1701. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3732. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CJ, Lain S, Verma CS, Fersht AR, Lane DP. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(12):862–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Fersht AR. Rescuing the function of mutant p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1(1):68–76. doi: 10.1038/35094077. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Henckel J, DeDecker BS, Johnson CM, Nikolova PV, Proctor MR, et al. Fersht AR. Thermodynamic stability of wild-type and mutant p53 core domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(26):14338–14342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14338. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock AN, Henckel J, Fersht AR. Quantitative analysis of residual folding and DNA binding in mutant p53 core domain: definition of mutant states for rescue in cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19(10):1245–1256. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203434. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess A, Chia KM, Haupt S, Thomas D, Haupt Y, Lim E. Clinical Overview of MDM2/X-Targeted Therapies. Front Oncol. 2016;6:7. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00007. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmakin M, Shi Y, Hedstrom E, Kogner P, Selivanova G. Dual targeting of wild-type and mutant p53 by small molecule RITA results in the inhibition of N-Myc and key survival oncogenes and kills neuroblastoma cells in vivo and in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(18):5092–5103. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2211. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JS, Loh SN. Structure, function, and aggregation of the zinc-free form of the p53 DNA binding domain. Biochemistry. 2003;42(8):2396–2403. doi: 10.1021/bi026635n. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykov VJ, Issaeva N, Shilov A, Hultcrantz M, Pugacheva E, Chumakov P, et al. Selivanova G. Restoration of the tumor suppressor function to mutant p53 by a low-molecular-weight compound. Nat Med. 2002;8(3):282–288. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-282. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bykov VJ, Zache N, Stridh H, Westman J, Bergman J, Selivanova G, Wiman KG. PRIMA-1(MET) synergizes with cisplatin to induce tumor cell apoptosis. Oncogene. 2005;24(21):3484–3491. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208419. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadillas JM, Tidow H, Freund SM, Rutherford TJ, Ang HC, Fersht AR. Solution structure of p53 core domain: structural basis for its instability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2109–2114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510941103. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carita G, Frisch-Dit-Leitz E, Dahmani A, Raymondie C, Cassoux N, Piperno-Neumann S, et al. Decaudin D. Dual inhibition of protein kinase C and p53-MDM2 or PKC and mTORC1 are novel efficient therapeutic approaches for uveal melanoma. Oncotarget. 2016:33542–33556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter PJ. Potent antibody therapeutics by design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(5):343–357. doi: 10.1038/nri1837. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabner BA, Roberts TG., Jr Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. Historical Article Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chargari C, Leteur C, Angevin E, Bashir T, Schoentjes B, Arts J, et al. Deutsch E. Preclinical assessment of JNJ-26854165 (Serdemetan), a novel tryptamine compound with radiosensitizing activity in vitro and in tumor xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2011;312(2):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.08.011. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Pankiewicz KW. Recent development of IMP dehydrogenase inhibitors for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2007;10(4):403–412. Review. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Rousseau RF, Middleton SA, Nichols GL, Newell DR, Lunec J, Tweddle DA. Pre-clinical evaluation of the MDM2-p53 antagonist RG7388 alone and in combination with chemotherapy in neuroblastoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(12):10207–10221. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3504. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY, Wang DH, Yen RC, Luo J, Gu W, Baylin SB. Tumor suppressor HIC1 directly regulates SIRT1 to modulate p53-dependent DNA-damage responses. Cell. 2005;123(3):437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.011. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chene P. Inhibiting the p53-MDM2 interaction: an important target for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(2):102–109. doi: 10.1038/nrc991. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chene P, Fuchs J, Bohn J, Garcia-Echeverria C, Furet P, Fabbro D. A small synthetic peptide, which inhibits the p53-hdm2 interaction, stimulates the p53 pathway in tumour cell lines. J Mol Biol. 2000;299(1):245–253. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheon MG, Kim W, Choi M, Kim JE. AK-1, a specific SIRT2 inhibitor, induces cell cycle arrest by downregulating Snail in HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2015;356(2 Pt B):637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.10.012. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265(5170):346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choong ML, Yang H, Lee MA, Lane DP. Specific activation of the p53 pathway by low dose actinomycin D: a new route to p53 based cyclotherapy. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(17):2810–2818. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.17.9503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, et al. Ryan KM. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell. 2006;126(1):121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarna A, Beck B, Srivastava S, Popowicz GM, Wolf S, Huang Y, et al. Domling A. Robust generation of lead compounds for protein-protein interactions by computational and MCR chemistry: p53/Hdm2 antagonists. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(31):5352–5356. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001343. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai MS, Lu H. Inhibition of MDM2-mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation by ribosomal protein L5. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(43):44475–44482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403722200. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai MS, Sun XX, Lu H. Aberrant expression of nucleostemin activates p53 and induces cell cycle arrest via inhibition of MDM2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(13):4365–4376. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01662-07. Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai MS, Zeng SX, Jin Y, Sun XX, David L, Lu H. Ribosomal protein L23 activates p53 by inhibiting MDM2 function in response to ribosomal perturbation but not to translation inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(17):7654–7668. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7654-7668.2004. Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dancey J, Sausville EA. Issues and progress with protein kinase inhibitors for cancer treatment. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(4):296–313. doi: 10.1038/nrd1066. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danovi D, Meulmeester E, Pasini D, Migliorini D, Capra M, Frenk R, et al. Marine JC. Amplification of Mdmx (or Mdm4) directly contributes to tumor formation by inhibiting p53 tumor suppressor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(13):5835–5843. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5835-5843.2004. Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demma M, Maxwell E, Ramos R, Liang L, Li C, Hesk D, et al. Dasmahapatra B. SCH529074, a small molecule activator of mutant p53, which binds p53 DNA binding domain (DBD), restores growth-suppressive function to mutant p53 and interrupts HDM2-mediated ubiquitination of wild type p53. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(14):10198–10212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]