Abstract

Humans inhale mold conidia daily and typically experience lifelong asymptomatic clearance. Conidial germination into tissue-invasive hyphae can occur in individuals with defects in myeloid function, although the mechanism of myeloid cell–mediated immune surveillance remains unclear. By monitoring fungal physiology in vivo, we demonstrate that lung neutrophils trigger programmed cell death with apoptosis-like features in Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, the most prevalent human mold pathogen. An antiapoptotic protein, AfBIR1, opposes this process by inhibiting fungal caspase activation and DNA fragmentation in the murine lung. Genetic and pharmacologic studies indicate that AfBIR1 expression and activity underlie conidial susceptibility to NADPH (reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidase-dependent killing and, in turn, host susceptibility to invasive aspergillosis. Immune surveillance exploits a fungal apoptosis-like programmed cell death pathway to maintain sterilizing immunity in the lung.

Programmed cell death (PCD) pathways in vertebrates shape the immune cell repertoire, eliminate cells infected by microbial pathogens, and are targets of microbial immune evasion strategies (1, 2). In contrast, it remains unknown whether vertebrate hosts can exploit conserved PCD pathways in eukaryotic pathogens to affect infectious outcomes and maintain barrier immunity. Humans inhale ~103 to 1010 mold conidia (i.e., vegetative spores) daily and, among these, Aspergillus fumigatus represents the most common agent of mold pneumonia worldwide (3). Sterilizing immunity depends on rapid conidial clearance by the respiratory immune system, primarily by neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes (4–6), to prevent the formation of multicellular, tissue-invasive hyphae.

To examine A. fumigatus conidial fate in the lung, we generated a histone 2A::monomeric red fluorescent protein reporter strain (H-RFP) that exploits loss of nuclear RFP fluorescence during fungal PCD, a strategy that has been harnessed in plant pathogenic fungi (7, 8) and mammalian cells (9). In vitro, 5 mM H2O2 induced markers of apoptosis-like PCD (A-PCD) in H-RFP conidia; these included nuclear condensation and loss of RFP fluorescence, detection of fungal caspase activity and DNA double-strand breaks, and coincided with loss of fungal cell viability (fig. S1, A to G).

For in vivo studies, we coupled Alexa Fluor 633 (AF633) to H-RFP conidia, because AF633-labeled conidia emit fluorescence after loss of viability (fig. S1G) (10), and examined free and leukocyte-engulfed conidia for A-PCD markers in the murine lung (Fig. 1A). Free conidia were RFP+AF633+ (Fig. 1B, orange gate), did not stain for caspase activity (Fig. 1, C and D) or by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) for DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1, E and F), and yielded >0.9 colony-forming units (CFU) per sorted event (Fig. 1G), indicative of fungal cell viability and no A-PCD induction.

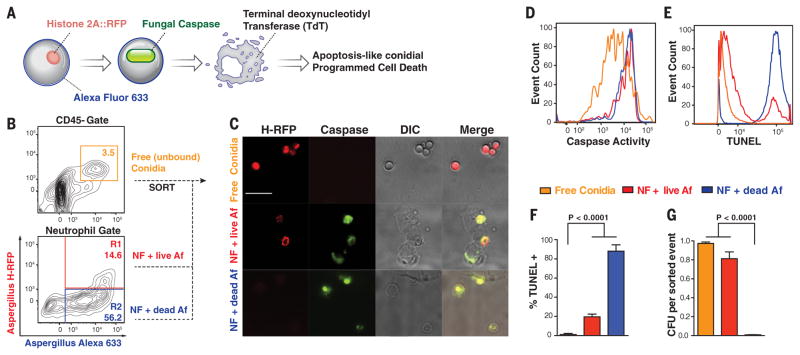

Fig. 1. Lung neutrophils trigger conidial A-PCD.

(A) Schematic for analysis of conidial A-PCD markers. NF, neutrophils; AF, Aspergillus fumigatus. (B) Murine lung CD45− cells and CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils analyzed for RFP and AF633 fluorescence 24 hpi with 3 × 107 AF633+H-RFP conidia. (C to G) Free conidia [orange gate in (B), lines in (D) and (E), and bars in (F) and (G)] and live [red gate in (B), lines in (D) and (E), and bars in (F) and (G)] and nonviable [blue gate in (B), lines in (D) and (E), and bars in (F) and (G)] conidia internalized in neutrophils were analyzed by (C) fluorescence microscopy (scale bar, 20 μm) and [(D) to (F)] flow cytometry for [(C) and (D)] caspase activity and [(E) and (F)] DNA fragmentation by TUNEL and (G) for fungal viability. [(F) and (G)] The data are presented as mean + SD of three independent experiments, each performed with triplicate samples. Statistical analysis: Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, followed by a Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons.

In contrast, RFP+AF633+ conidia engulfed by neutrophils (Fig. 1B, R1 gate) consistently stained for fungal caspase activity (Fig. 1, C and D), and ~20% of these were TUNEL positive. This subset remained largely viable (~80%) by CFU analysis of sorted neutrophils (Fig. 1G), consistent with the model that fungal caspase activation precedes loss of nuclear RFP fluorescence, DNA fragmentation, and fungal death. RFP–AF633+ conidia in neutrophils (Fig. 1B, blue R2 gate) were uniformly positive for caspase activity, >80% TUNEL positive, and yielded <0.008 CFU per sorted event. Thus, neutrophil interactions induce conidial markers of A-PCD in vivo.

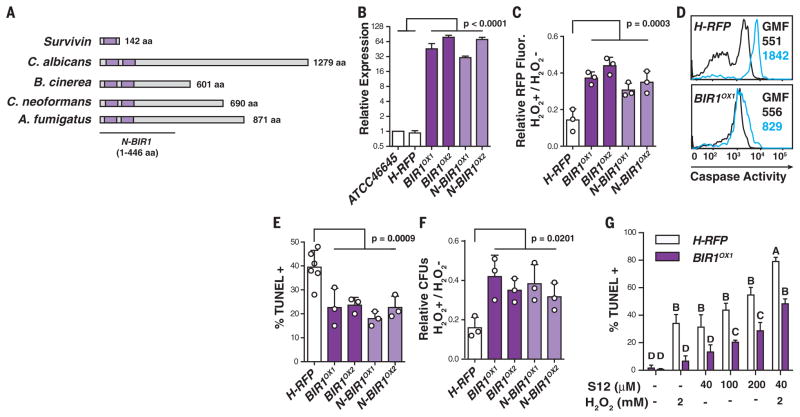

To investigate its relevance for pathogenesis, we engineered A. fumigatus strains that are modified in their response to A-PCD induction. Using a bioinformatics approach, we identified AfBIR1 (hereafter referred to as BIR1), a homolog of human survivin (11) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae BIR1 (12) (Fig. 2A and fig. S2A), both inhibitor-of-apoptosis protein family members (13). Survivin encodes a single BIR domain and suppresses apoptosis by inhibiting caspase-3 and -7 (14). Transgenic strains that overexpress full-length A. fumigatus BIR1 (BIR1OX1,2) (Fig. 2B and fig. S2, B and C) exhibited a similar radial growth, conidiation, and germination rate as the parental H-RFP strain (fig. S2, D to F). In both full-length BIR1 OX isolates, we observed reduced A-PCD compared with the parental strain under oxidative stress in vitro, as judged by reduced RFP signal loss, reduced fungal caspase activity, reduced number of TUNEL-positive nuclei, and enhanced survival (Fig. 2, C to F). Over-expression of the BIR1 N-terminal region (N-BIR1 OX1,2) (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S2, A to C) that includes two BIR domains was sufficient to recapitulate the phenotypes observed in isolates that overexpress the full-length gene (Fig. 2, C to F). In two independent attempts, we did not succeed in generating a bir1 null strain. Placement of the BIR1 gene under control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter (i.e., bir1tetON strain) indicated that the gene is essential for growth under laboratory conditions tested (fig. S3). In the absence of a bir1 null strain, we added S12 (15), a Survivin antagonist that targets the BIR domain, and observed more intense TUNEL staining in H-RFP compared with BIR1OX1 fungal cells (Fig. 2G and fig. S4). Moreover, S12 sensitized fungal cells to subapoptotic H2O2 levels, with more pronounced effects on H-RFP than on BIR1OX and N-BIR1OX fungal cells, as judged by reduced RFP fluorescence, increased fungal caspase activity, increased TUNEL signal, and reduced fungal viability. The analysis of four independent isolates with similar phenotypes and the use of a pharmacologic inhibitor preclude the likelihood of off-target effects of the overexpression strategy. Collectively, these data indicate that BIR1 mediates anti-PCD activity in A. fumigatus; the BIR1 N-terminal region is sufficient for this function.

Fig. 2. BIR1 regulates conidial A-PCD.

(A) Organization of BIR domains (purple) in human Survivin, Candida albicans CaBIR1, Botrytis cinerea BcBIR1, Cryptococcus neoformans CnBIR1, and Aspergillus fumigatus AfBIR1. (B) BIR1 mRNA expression in the indicated strains (white, control strains; dark purple, full-length BIR1OX strains; light purple, N-terminal BIR1OX strains) normalized to β-tubulin and gpdH and expressed as the mean relative change. (C to G) Swollen conidia [(C), (E), and (F)] or germlings (D) were exposed to 0 or 5 mM H2O2 and analyzed for (C) RFP intensity, (D) caspase activity (0 mM H2O2, black lines; 5 mM H2O2, blue lines; GMF, geometric mean fluorescence), (E) TUNEL signal, and (F) CFUs. (G) TUNEL signal in H-RFP and BIR1OX1 swollen conidia after S12 and H2O2 exposure, as indicated. [(C), (E), and (F)] Each circle represents data pooled from three replicates in one experiment. The bar graphs indicate mean + SD of two (B) or three to six [(C) and (E) to (G)] independent experiments, and [(C) and (F)] data are normalized to the control condition (0 mM H202 condition). Statistical analysis: One-way [(C), (E), and (F)] or two-way (G) analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s [(C), (E), and (F)] or Sidak’s (G) test for multiple comparisons. (G) Different letters indicate groups that are statistically different (P < 0.05).

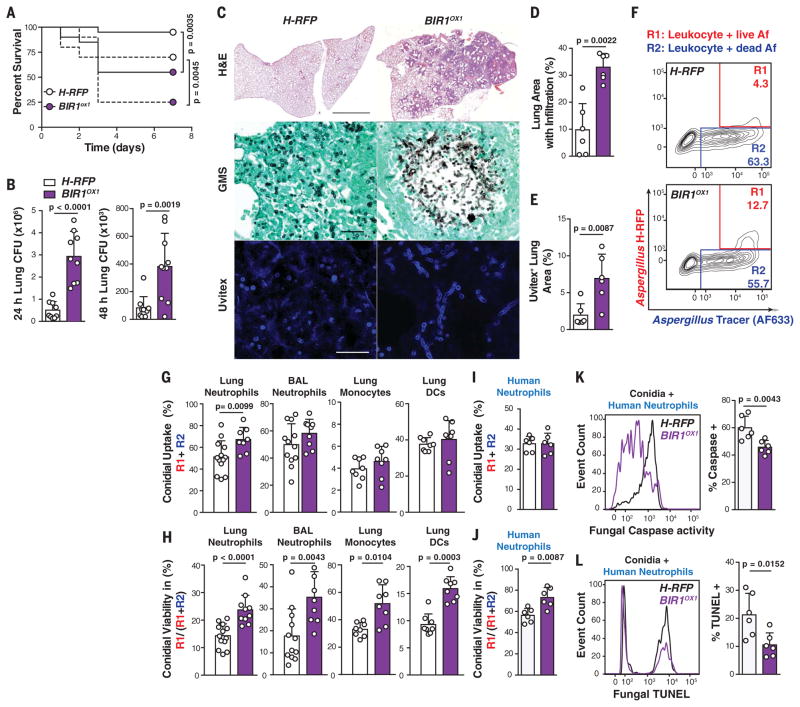

To determine whether BIR1 expression levels influence virulence, we challenged C57BL/6 mice with 6 or 12 × 107 conidia and observed significantly higher mortality with BIR1OX1 compared with H-RFP conidia (Fig. 3A). A similar result was observed when mice were challenged with an independent BIR1OX isolate generated on the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 46645 background that lacks the H-RFP transgene (fig. S5). BIR1OX1-challenged mice exhibited a higher fungal burden than control mice (Fig. 3, B to E). Lung histopathology revealed many germinating conidia and fungal hyphae (Fig. 3C) within multifocal to coalescing areas of necrosis and inflammation (Fig. 3D), indicative of severe tissue destruction associated with invasive aspergillosis that affected >30% of the parenchyma. In mice infected with H-RFP conidia, lung sections contained only rare germinating conidia and few tissue-invasive hyphae (Fig. 3, C to E). Lung sections had moderate multifocal neutrophilic inflammation, and ~10% of the parenchyma was affected by mild necrosis (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3. BIR1 levels regulate A. fumigatus virulence.

(A) Survival of C57BL/6 mice challenged with 6 × 107 (continuous line) or 12 × 107 (broken line) H-RFP (white circles or bars) or BIR1OX1 (purple circles or bars) conidia (n = 20 per group, pooled from two experiments per inoculum). (B) Lung CFUs at 24 and 48 hpi with 3 × 107 conidia. (C) Micrographs of lung sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (scale bar, 2 mm), Gomori’s ammoniacal silver (scale bar, 50 μm), and Uvitex (scale bar, 50 μm). (D and E) Morphometric analysis of (D) lung consolidation and (E) Uvitex staining (n = 6) at 72 hpi with 6 × 107 H-RFP [white bars; (B), (D), and (E)] or BIR1OX1 conidia [purple bars; (B), (D), and (E)]. (F) Representative lung neutrophil conidial uptake and killing, analyzed on the basis of RFP and AF633 fluorescence, 24 hpi with 3 × 107 AF633+ H-RFP conidia. (G and H) The scatter plots indicate (G) conidial uptake by and (H) conidial viability (H-RFP in purple bars, BIROX1 in white bars) in indicated leukocyte subsets. (I) Conidial uptake, (J) conidial viability, and frequency of (K) caspase+ and (L) TUNEL+ conidia (H-RFP, white bars; BIR1OX1, purple bars) in human neutrophils (multiplicity of infection = 3; 8 hours coincubation). The data are presented as mean + SD and are pooled from three independent experiments, with each circle denoting a [(D) and (E)] murine lung section, [(G) and (H)] mouse, or [(I) to (L)] in vitro human sample. Statistical analysis: (A) Log-rank (Mantel-Cox); [(B), (D), (E), and (G) to (L)] Mann-Whitney tests.

Consistent with these findings, there was a transient increase in total lung leukocytes, neutrophils, and inflammatory monocytes in BIR1OX1-challenged mice compared with H-RFP–challenged mice 24 hours postinfection (hpi) (fig. S6A), although differences resolved by 48 hpi. The number of lung monocyte–derived dendritic cells (Mo-DCs) was higher in the BIR1OX1-challenged group at 48 hpi, consistent with the developmental relationship between infiltrating monocytes and Mo-DCs (16). Challenge with BIR1OX1 conidia resulted in higher lung inflammatory cytokine [tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1α (IL-1α), and IL-1β] and chemokine (CXCL1, CXCL2, and CXCL5) levels at 24 hpi than challenge with H-RFP conidia (fig. S6B). Because irradiated H-RFP and BIR1OX1germlings induced equivalent macrophage inflammatory responses in vitro (fig. S2G), the higher level of tissue inflammation in BIR1OX1-challenged mice reflected a higher fungal burden rather than a strain-specific difference in the induction of host inflammation. Collectively, these data indicate that the BIR1OX1 strain is more virulent than the H-RFP strain and leads to invasive aspergillosis in immune-competent mice.

To determine the mechanism by which BIR1 expression levels promote invasive aspergillosis, we compared leukocyte conidial uptake and killing in BIR1OX1- and H-RFP–challenged mice (Fig. 3F). The frequency of lung neutrophil conidial uptake (Fig. 3G) was slightly higher for BIR1OX1 than for H-RFP conidia at 24 hpi, but this finding was not observed for airway neutrophils, lung monocytes, or Mo-DCs, suggesting that differences in conidial uptake are unlikely to account for the difference in fungal virulence. In contrast, the frequency of fungus-engaged lung and airway neutrophils that contain live conidia was higher by a factor of 1.7 (23.7 ± 2.0% versus 14.3 ± 1.7%) and 2 (35.3 ± 4.5% versus 17.7 ± 4.3%) in BIR1OX1-challenged than in H-RFP–challenged mice, respectively, at 24 hpi (Fig. 3H). Similarly, the frequency of fungus-engaged lung monocytes and Mo-DCs that contain live BIR1OX1 conidia was higher by a factor of 1.57 (51.8 ± 3.8% versus 33.0 ± 4.1%) and 1.72 (15.9 ± 1.0% versus 9.3 ± 1.0%) in BIR1OX1-challenged than in H-RFP–challenged mice, respectively. These data indicate that BIR1 overexpression confers protection against myeloid cell–mediated conidial killing in the lung. To exclude the possibility that differences in neutrophil influx contribute to these results, we examined BIR1OX1,2, N-BIR1OX1,2, and H-RFP conidial uptake by and survival in murine (fig. S7, A and B) and human neutrophils ex vivo (Fig. 3, I to L). BIR1OX1,2 and N-BIR1OX1,2 conidial viability in fungus-engaged human and murine neutrophils was higher than that of H-RFP conidia (Fig. 3J and fig. S7C), and the frequency of caspase+ and TUNEL+ fungal cells was much lower for the BIR1OX1,2 or N-BIR1OX1,2 strains compared with the H-RFP strain (Fig. 3, K and L; fig. S7D), even when hyphae were coincubated with human neutrophils (fig. S8).

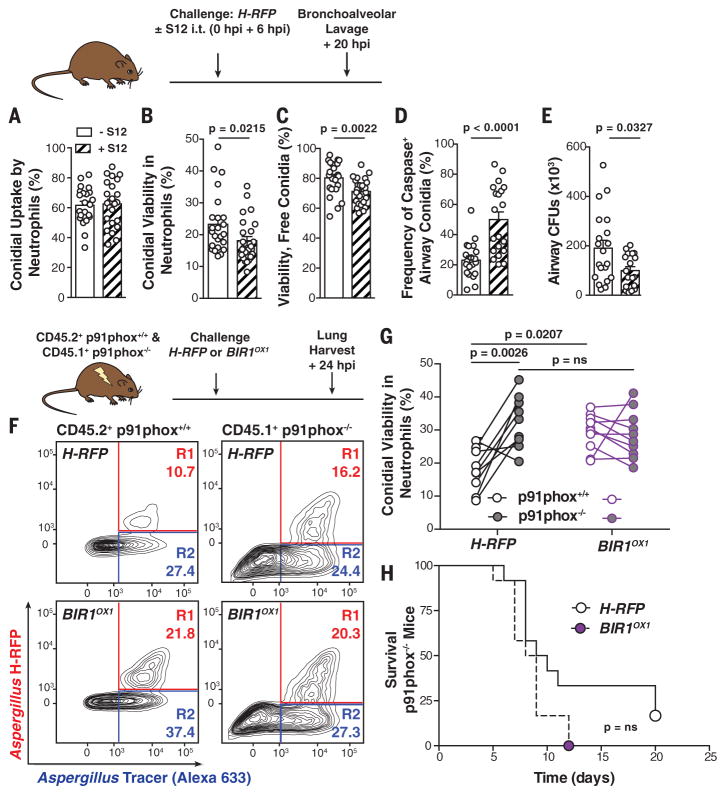

To evaluate the effect of pharmacologic Bir1p inhibition on infectious outcomes, mice were challenged with H-RFP conidia and treated with S12 via the respiratory route. Although S12 did not affect neutrophil conidial uptake (Fig. 4A), the drug reduced the viability of neutrophil-engulfed (Fig. 4B) and free conidia (Fig. 4C), increased the frequency of caspase+ fungal cells in infected airways (Fig. 4D), and accelerated fungal clearance (Fig. 4E). Thus, BIR1 overexpression and Bir1p pharmacologic inhibition mediate A. fumigatus resistance and susceptibility, respectively, to A-PCD induction by murine and human myeloid cells.

Fig. 4. NADPH oxidase induces conidial A-PCD.

(A to E) Mice were challenged with 3 × 107 AF633+ H-RFP conidia with 7.5 mg per kg of weight of S12 or vehicle control, as indicated. The scatter plots show mean + SEM for (A) conidial uptake, (B) viability in airway neutrophils, (C) free airway conidial viability, (D) fungal caspase activity in free and leukocyte-engulfed airway conidia, and (E) fungal airway CFUs at 20 hpi (n = 20 per group). (F) Representative plots of neutrophils isolated from mixed bone marrow chimeric mice, as indicated above, and analyzed for conidial fluorescence. (G) H-RFP (black circle outline) and BIR1OX1 (purple circle) conidial viability in p91phox+/+ (white center) and p91phox−/− (gray center) neutrophils. The lines indicate paired data from a single mouse. (H) Survival of p91phox−/− mice challenged with 5 × 104 H-RFP or BIROX1 conidia (n = 12 per group). All data were pooled from two independent experiments, with each circle denoting one mouse. Statistical analysis: [(A) to (G)] Mann-Whitney; (H) Log-rank (Mantel-Cox).

To determine host mechanisms that induce A. fumigatus A-PCD, we compared BIR1OX1 and H-RFP growth under a variety of stress conditions (fig. S9). Both strains exhibited similar growth under acidic and basic conditions and in the presence of cell wall–perturbing agents and sodium nitrite. However, the BIR1OX1 strain displayed a growth advantage under oxidative stress, including menadione and H2O2. This finding suggested that resistance of BIR1OX1 conidia to myeloid cell killing is likely related to induction of A-PCD by phagocyte NADPH (reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) oxidase (i.e., NOX2). Humans with chronic granulomatous disease have genetic defects in NOX2 and a 40% lifetime risk of invasive aspergillosis (17), highlighting the role of NOX2 in barrier immunity against ubiquitous A. fumigatus exposure. To examine this hypothesis, we measured BIR1OX1 and H-RFP conidial killing in mixed bone marrow chimeric mice that contain both NADPH oxidase-sufficient and -deficient neutrophils in the lung (Fig. 4F). BIR1OX1 conidia survived equally well in p91phox−/− (28.6 ± 3.5%) and in p91phox+/+ neutrophils (29.3 ± 2.6%). In contrast, H-RFP conidia exhibited 32.6 ± 3.5% viability in p91phox−/− neutrophils but only 17.8 ± 2.7% viability in p91phox+/+ neutrophils (Fig. 4, F and G), indicating that BIR1 expression levels can counter the fungicidal activity of neutrophil NADPH oxidase by raising the threshold for A-PCD induction.

To investigate the conjecture that the difference in virulence between BIR1OX1 and H-RFP conidia depends on host NADPH oxidase expression, we challenged p91phox−/− mice with 5 × 104 BIR1OX1 or H-RFP conidia. In contrast to p91phox+/+ mice (Fig. 3A and fig. S5), the survival of p91phox−/−mice was similar whether BIR1OX1 or H-RFP conidia were administered (Fig. 4H). These data show that the virulence of the BIR1OX1 strain is comparable to that of the parental strain in the absence of host NADPH oxidase. Our results advance the concept that sterilizing immunity against mold conidia exploits fungal A-PCD to prevent the formation of multicellular, tissue-invasive hyphae in the lung (fig. S10). In this model, pathogen virulence is a product of microbial (i.e., fungal Bir1p) and host factors (i.e., NADPH oxidase) in determining disease development (18). Although fungi exhibit a conserved set of apoptotic markers (19), the fungal A-PCD apparatus is notably different from the mammalian apoptotic apparatus (20). Targeted pharmacologic blockade of key components in the fungal anti-PCD response, exemplified by Bir1p, may augment prophylactic or therapeutic approaches against invasive aspergillosis and highlight the importance of characterizing differences in protein structure between mammalian and fungal BIR domains involved in PCD. Identification of additional host effectors and compounds (21) that induce A-PCD in conidia and hyphae may inform new strategies for therapeutic intervention in vulnerable patient groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Pamer, M. Li, S. Kasahara, B. Zhai, and L. Heung for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript; the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Cytology Facility, C. Franqui, and I. Leiner for technical assistance; S. Knoblaugh (Ohio State University) for histopathology; and D. Askew (University of Cincinnati) for expertise on fungal strains. This research was supported by NIH grants RO1 AI093808 (T.M.H.), R21 AI105617 (T.M.H.), RO1 AI081838 (R.A.C.), T32 GM008704 (S.R.B.), P30 CA008748 (to MSKCC), and P30GM106394 (B. Stanton, principal investigator; R.A.C., Pilot Project); Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Awards (T.M.H. and R.A.C.); Israel Science Foundation grant 835/13 (A.S.); and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant BR1502/11-2 (G.H.B.). All data and code to understand and address the conclusions of this research are available in the main text and supplementary materials.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Nagata S, Tanaka M. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorgensen I, Rayamajhi M, Miao EA. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:151–164. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown GD, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerson SL, et al. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:345–351. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-3-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal BH. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1870–1884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espinosa V, et al. PLOS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003940. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veneault-Fourrey C, Barooah M, Egan M, Wakley G, Talbot NJ. Science. 2006;312:580–583. doi: 10.1126/science.1124550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shlezinger N, et al. PLOS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002185. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konishi A, et al. Cell. 2003;114:673–688. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jhingran A, et al. Cell Reports. 2012;2:1762–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Flanary PL, Altieri DC, Dohlman HG. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:6707–6711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.6707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin S, et al. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1117–1123. doi: 10.1021/bi001603q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berezov A, et al. Oncogene. 2012;31:1938–1948. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohl TM, et al. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland SM. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2010;38:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casadevall A, Pirofski L. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:337–344. doi: 10.1086/322044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharon A, Finkelstein A, Shlezinger N, Hatam I. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2009;33:833–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shlezinger N, Doron A, Sharon A. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:1493–1498. doi: 10.1042/BST0391493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hein KZ, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:13039–13044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511197112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.