Abstract

The origin of cellular compartmentalization has long been viewed as paralleling the origin of life. Historically, membrane-bound organelles have been presented as the canonical examples of compartmentalization. However, recent interest in cellular compartments that lack encompassing membranes has forced biologists to reexamine the form and function of cellular organization. The intracellular environment is now known to be full of transient macromolecular structures that are essential to cellular function, especially in relation to RNA regulation. Here we discuss key findings regarding the physicochemical principles governing the formation and function of non-membrane bound organelles. Particularly, we focus how the physiological function of non-membrane-bound organelles depends on their molecular structure. We also present a potential mechanism for the formation of non-membrane-bound organelles. We conclude with suggestions for future inquiry into the diversity of roles played by non-membrane bound organelles.

Keywords: non-membrane-bound organelles, liquid-liquid phase separation, endosymbiosis, macromolecular crowding, cellular biophysics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In her seminal 1967 paper, Lynn Sagan (1967) – Lynn Margulis – presented a theory of the endosymbiotic origin of eukaryotes. The central tenant of Margulis’s theory was that membrane-bound organelles within eukaryotic cells, specifically mitochondria and chloroplasts, were actually the result of one prokaryotic cell enveloping another, as opposed to the linear evolution of a single prokaryote. Although the proposition of an endosymbiotic origin of eukaryotes initially met stiff resistance, and several details of the theory presented by Margulis turned out to be incorrect,1 it has come to be generally accepted. The endosymbiotic theory explains the origin of double-membrane-bound organelles in eukaryotes, and has spurred continued debate about the evolution of other membrane-bound organelles including the nucleus (Embley and Martin, 2006; Devos et al., 2014; Shellman et al., 2014). Interestingly, the third organelles mentioned by Sagan (1967) were the (9+2) basal bodies – assemblies of microtubules found at the base of flagellum and cilium that are essential for mitosis. Unlike the membrane-bound mitochondria and chloroplasts, basal bodies are self-organized protein structures that lack an encompassing membrane. Since Margulis’s publication, many non-membrane-bound organelles have been identified, and, in many cases, their roles and origins remain to be discovered.

The proper functioning of a cell requires the organization of macromolecules into compartments, which contain and enhance biochemical reactions. Prominent examples of compartments lacking surrounding membranes are P-granules (Brangwynne et al., 2009), Cajal bodies (Strzelecka et al., 2010; Handwerger et al., 2005), nucleoli (Brangwynne et al., 2011; Weber and Brangwynne, 2015), and paraspeckles in the nucleus (Hennig et al., 2015), stress granules (Wippich et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2015) and centrosomes in the cytoplasm (Woodruff et al., 2015), and signaling complexes on the cytosolic face of membranes (Li et al., 2012; Banjade and Rosen, 2014).

In the last 10 years cell, biologists have come to understand that the formation of non-membrane-bound compartments is driven by liquid-liquid demixing (Hyman et al., 2014; Brangwynne et al., 2015). The compartments are thought to phase separate from the cytoplasm, leading to the formation of liquid droplets, which stably coexist with their surrounding environment. Experimental studies have confirmed the liquid-like behavior of P-granules in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos (Brangwynne et al., 2009), nucleoli (Brangwynne et al., 2011), and stress granules (Patel et al., 2015; Aggarwal et al., 2013). As these macromolecular assemblies offer a mechanism for concentrating biochemical reactants without the need of phospholipid membranes, it has been suggested that they may have played a role in the early evolution of life (Brangwynne et al., 2009; Hyman et al., 2014), and may even be capable of a mitosis-like process under a sustained energy flux (Zwicker et al., 2016). In this article, we review the physicochemical properties leading to liquid-liquid phase separation within the cell. Specifically, we emphasize that classical models of polymer solutions, such as Florry-Huggins (Flory, 1953) theory and the Overbeek-Voorn (Overbeek and Voorn, 1957) theory of charged solutions, are insufficient for treating the diverse and crowded solutions of polyelectrolytes found in cells. We then discuss the physiological role of these self-assembled bodies, focusing in particular on the manner in which they alter biochemical kinetics.

2. What is a cellular organelle?

Cellular organelles are subcellular compartments containing characteristic sets of specialized molecules that are structurally organized as to carry out one or more specific functions. Additionally, organelles possess systems to transport or exchange molecules from one compartment to another.

The stable intracellular compartments of an eukaryotic cell are composed of membrane-enclosed organelles. The main types of stable organelles present in all eukaryotic cells are the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, nucleus, mitochondria, lysosomes, endosomes, and peroxisomes. Most of the membrane-enclosed organelles cannot be constructed de novo; they require information in the organelle itself. During cell division, organelles (such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria) are distributed intact to each daughter cell. Some organelles such as the mitochodria and plastids are encompassed by a lipid bilayer and contain DNA encoding their construction. These observations motivated the endosymbiotic hypothesis formalized by Sagan (1967). Other membrane-enclosed organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, are bound by single-layer membranes. In the case of both single- and double-layer membrane-bound organelles, phospholipids provide a clear separation between the organelle interior and the cytoplasm.

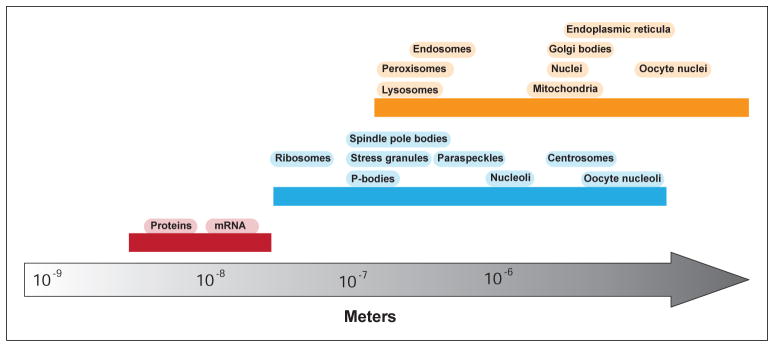

In contrast, non-membrane-bound organelles are structures that create distinct biochemical environments by organizing and immobilizing a selected set of macromolecules. Due to the absence of lipid barriers, molecules entering non-membrane-bound organelles are processed through complex reaction pathways with great efficiency. Non-membrane-bound organelles can impart many of the advantages of compartmentalization to reactions that take place in the cell. However, since they lack the phospholipid barrier of their membrane-bound counterparts, many of these non-membrane-bound compartments can neither concentrate nor exclude specific small molecules, and more rapidly exchange their components with their surroundings. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments indicate that the time for molecules within the non-membrane-bound compartments to exchange with the surrounding fluid is on the order of minutes (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015; Banani et al., 2016). Moreover, a model system displaying many of the core features of non-membrane-bound organelles suggests compartment compositions may realign in as little as a few seconds in response to physicochemical shifts to their environment (Banani et al., 2016). This is in marked contrast with membrane-bound organelles such as mitochondria, whose half-lives are estimated to be several days (Lipsky and Pedersen, 1981). Additionally, as shown in Fig. 1, non-membrane-bound organelles are typically smaller than membrane-bound organelles, although there is considerable diversity in their sizes. In this sense, non-membrane-bound organelles fill a gap in cellular organization, in terms of length and timescales, between soluble macromolecules and membrane-bound organelles. In the following section, we discuss the physicochemical principles involved in the formation and organization of non-membrane-bound organelles.

Figure 1. Length scales of non-membrane-bound organelles.

The sizes of non-membrane-bound organelles span a large range, from tens of nanometers in the case of ribosomes, to microns in the cases of oocyte nucleoli (Brangwynne et al., 2011). The majority of non-membrane-bound organelles are hundreds of nanometers in size, placing them at an intermediate length scale between macromolecules and most membrane-bound organelles.

3. Physicochemical properties of non-membrane-bound organelles

Due to their lack of encompassing lipid membranes, non-membrane-bound organelles depend on different physicochemical mechanisms for their formation and stability. Most notably, proteins and nucleic acids organize to form an interface directly with the cytoplasm. At this interface, proteins and RNA readily exchange with surrounding soluble molecules, making the size and composition of non-membrane-bound organelles more dynamic than organelles with membranes. Additionally, the high density of weakly interacting macromolecules causes the physical environment within non-membrane bound organelles to be far more viscous that typical membrane-bound organelle interiors. The different types of electrostatic interactions within non-membrane-bound organelles, including ion-ion, ion-dipole, dipole-dipole, cation-π, and π-π interactions, along with entropic crowding forces (Brangwynne et al., 2015), greatly complicate the physicochemical picture, making a predictive theory of their formation, morphology, and stability a continued challenge to the biophysics community. Below, we review recent progress in understanding the complex processes governing non-membrane-bound organelle structure.

The dynamic structure of non-membrane-bound organelles is controlled by the physics of liquid-liquid phase separation

The physicochemical aspects of liquid-liquid phase separations within cells has been reviewed recently (Weber and Brangwynne, 2012; Hyman et al., 2014; Brangwynne et al., 2015; Mitrea and Kriwacki, 2016; Courchaine et al., 2016; Bergeron-Sandoval et al., 2016), so we provide only a brief synopsis, highlighting key findings. Liquid-liquid phase separation is a well-studied phenomenon in soft matter physics in which an initially mixed solution of molecules separates into two (or more) phases after, for example, lowering the temperature. The canonical Flory-Huggins model for liquid-liquid phase separation consists of a polymer of a single monomer type immersed in a simple solvent. The interactions between monomers, monomers and solvent, and solvent molecules differ. In the case of unfavorable monomer-solvent interactions, a condensed phase is favorable, in which the polymer maximizes self-contacts. However, the entropic cost of separating the polymer from the solvent favors the well-mixed state in which the polymer is partially extended. Since this entropic cost grows with temperature, the system exhibits a phase transition from the condensed polymer phase to the well-mixed phase at a critical temperature determined by the interaction energies and polymer concentration (Flory, 1953).

Typically, droplets of molecules form with an inside concentration that is much larger than the concentration outside of the droplet, in the surrounding milieu. In general, phase separation is very sensitive to changes in certain parameters, such as temperature, ionic strength, pH, or molecular concentration (Hyman et al., 2014). Droplets form suddenly with a small shift of temperature or salt concentration, and upon reverting the temperature change or weakly perturbing the ionic strength of the solution, droplets can dissolve again. The discrete jumps in concentration and compositions that result from liquid-liquid phase transitions mean mesoscopic liquid structures, such as macromolecular droplets, are extremely sensitive to changes in physicochemical conditions.

The view of non-membrane-bound organelles as phase-separated materials was supported by early studies into nuclear bodies called P-granules. Biophysical experiments showed that they resulted from nuclear proteins and RNA losing solubility and condensing into spherical droplets (Brangwynne et al., 2009). The droplets possess the properties of liquids including ability to flow under shear stress, droplet fusion, and surface wetting. It was hypothesized that the permiscuity and weak binding between RNA and RNA-binding proteins (Lunde et al., 2007) provides the right conditions for liquidity of the condensed phase. Further study of amphibian oocyte nucleoli reinforced the view that liquid-liquid phase separation could be a general phenomenon among non-membrane-bound organelles (Brangwynne et al., 2011). The oocyte nucleoli showed a distribution of sizes that could be well-described by a droplet aggregation process and fusion of nucleoli was directly observed. Analysis of relaxation dynamics indicate the non-membrane-bound bodies are three to six orders of magnitude more viscous that water (Brangwynne et al., 2009, 2011).

The physicochemical properties of the phase-separated droplets are also highly responsive to environmental conditions such as salt and RNA content, both of which decrease droplet viscosity (Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015). Interestingly, ATP depletion also resulted in decreased viscosity, suggesting the liquidity of nucleoli may be metabolically-controlled (Brangwynne et al., 2011; Hubstenberger et al., 2013), and the droplets themselves may have active components (Brangwynne et al., 2015). Recent progress has been made in our understanding of the mechanisms both driving organelle assembly and dictating their physicochemical properties. The Flory–Huggins model, though simple, provides a foundation for the understanding of the more complex liquid-liquid phase separation which occurs in the crowded, species-diverse, and charged intracellular environment. Extensions to Flory-Huggins theory that treat electrostatic interaction using a mean field approach (Overbeek and Voorn, 1957; Veis, 2011) can address some of the added complexity found in the cell, but fall short in describing many of the key interactions.

First, describing the interactions between polyelectrolytes, ions, and other proteins, which heavily depend on the ionic strength and pH of the medium, remains theoretically challenging. Modeling efforts are hindered by the long-range nature of electrostatic interactions, the large ensemble of possible configurations of the polyelectolytes and surrounding ions, and the variable solvation of the individual ions close to the polyelectrolyte (Lipfert et al., 2014). While mean-field theories may be applicable to ionic interactions with planar charged surfaces, these theories break down for polyelectrolytes due to the short-range nature of the interactions between neighboring charged residues (Borkovec et al., 1997). Hence, the ionization state of a polyelectrolyte, which is important for the formation of dense polyelectrolyte-protein phases, depends on both the long-range effects due to the ionic strength of the medium, and the short-range interactions between neighboring charges on the polyelectrolyte (Garcés et al., 2017).

While theories for the interactions between ions and polyelectrolytes provide a framework for analyzing liquid-liquid phase separation of charged polymers, non-membrane-bound organelle formation is further complicated by the important role played by the amino acid sequence (Brangwynne et al., 2015). The amino acid sequence is of particular interest because many proteins involved in the formation of intracellular liquid droplets have intrinsically disordered regions (Toretsky and Wright, 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015; Uversky et al., 2015). Recently, it was shown that the non-membrane bound organelles formed from the disordered N-terminus of Ddx4 were largely driven by electrostatic interactions resulting from patterning of the amino acid sequence, and the stability of the bodies could be tuned through environmental perturbations (Nott et al., 2015). The promiscuity of binding by proteins with disordered regions likely facilitates the transient formation and liquidity of non-membrane-bound organelles.

Lastly, the tremendous diversity of species making up the cellular milieu provides a uniquely biological challenge. Whereas most soft-matter theory has been developed for polymer mixtures of one or a few molecular species, the intracellular environment consists of thousands of different molecule types, each at relatively low copy number. A recent study has attempted to address this issue though Monte Carlo simulation of mixtures with high species diversity (Jacobs and Frenkel, 2017). The simulations show that random mixtures with large numbers of species display two classes of behavior: one with spatially-heterogeneous demixed phases that are enriched in a small number of species, and another with two similar phases with high heterogeneity. The former are favored in cases with a large variance in the strength of intermolecular interactions between species, and the multiple phases that arise are shown to be readily tunable by adjustment of the chemical potentials of the constitutive molecules. The simulations support the idea that liquid-liquid phase separation in the cell is a general property of multi-component mixtures, and suggests the diversity of interactions are crucial to multiphase coexistence. However, it remains to be seen how more detailed descriptions of the intermolecular interactions related to ions, poly-electrolytes, and disordered amino acid sequences fit into this framework.

It has become clear that cells operate near the liquid-liquid phase boundary and use these transitions for functional control (Weber and Brangwynne, 2015; Zwicker et al., 2014; Berry et al., 2015). For example, the growth of nucleoli and “extranucleolar droplets” in the nucleoplasm display the characteristics of first-order phase transitions in which local thermodynamic parameters governing the state of the system are altered by active processes taking place at the sites of ribosomal RNA transcription (Berry et al., 2015). In a similarly active control process, centrosome formation appears to depend on an autocatalytic growth process that is nucleated by the centriole (Zwicker et al., 2014). Additionally, engineered model multivalent proteins that act as scaffolding for liquid-phase aggregates have shed light on the relationship between liquid-liquid phase separation and valency of interacting molecules (Li et al., 2012). Recent evidence indicates that these multivalent scaffolding proteins concentrate client proteins of lower valency (Banjade et al., 2015; Woodruff et al., 2015; Banani et al., 2016). By altering the concentration of scaffolding proteins, the amount of client protein partitioning into the condensed phase could be modulated in a similar manner as observed in natural processing bodies (P-bodies) and promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies.

Over the last several years, a picture has emerged of non-membrane-bound organelles as highly responsive, liquid structures of weakly interacting proteins and RNA. Their responsiveness results from their proximity (in phase space) to liquid-liquid phase transitions, with phase compositions and transition points readily modified by environmental queues. The ubiquity of non-membrane-bound structures in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm indicates that organization through liquid-liquid phase separation likely plays an important physiological role. In the following section, we seek to address this role.

4. Physiology of non-membrane-bound organelles: bioreactors or storage depots?

Understanding the function of non-membrane-bound organelles remains a challenge to cell biologists and cellular physiologists. In general, membrane-bound compartments serve two seemingly-opposing purposes: to localize certain molecules and processes, thereby improving efficiency of biochemical reactions, and to sequester molecules for later use, decreasing the rate of biochemistry involving those molecules. Evidence suggests non-membrane-bound organelles play similar roles. For example, the nucleolus serves as the location of ribosomal RNA transcription, pre-ribosomal RNA processing and post-transcriptional modification, and ribosomal subunit assembly (Olson et al., 2002). Although its primary role appears to be ribosome biogenesis, the nucleolus also modulates the tumor suppressor protein p53, which causes apoptosis as part of the cellular stress response (Rubbi and Milner, 2003), and sequesters the γ-isoform of protein phosphatase 1 during interphase (Gunawardena et al., 2008) and reverse transcriptase until the latter stages of mitosis (Khurts et al., 2004). Similarly, one possible function of paraspeckles, small subnuclear compartments located in the interchromatin space, may be to regulate proteins related to cell differentiation by sequestering key mRNA molecules (Fox and Lamond, 2010).

Non-membrane-bound organelles act as bioreactors

In confined or crowded environments, the rates of biochemical reactions can differ markedly from their dilute, well-mixed counterparts (Schnell and Turner, 2004; Zhou et al., 2008; Mourão et al., 2014). Crowding reduces the diffusion coefficient of reactants, slowing diffusion-limited reactions and giving rise to fractal-like reaction kinetics (Kopelman, 1988; Schnell and Turner, 2004; Pitulice et al., 2014). If the concentration of reactants grows, the likelihood of a reaction occurring increases. In contrast to concentrated environments, the volume fraction of diffusing macromolecules is large while the concentration of specific species can remain relatively small in crowded environments. Under conditions of high molecular diversity and crowding, inhibited diffusion can suppress otherwise favorable reactions. Thus, heterogeneous concentrations that corral interacting species have a catalytic effect in overcoming the diffusional barrier. This is certainly the case for ribosome biogenesis, which requires the spatio-temporal coordination of approximately 170 different proteins, many of which reside in the nucleolus (Fromont-Racine et al., 2003). The nucleolus is home to over 60 different small nucleolar ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs) that modify pre-ribosomal RNA after transcription (Thomson et al., 2013). The series of reactions required for ribosomal subunit production rely on the directed machinery and the spatial organization found in the nucleolus. Recently, nucleoli have been hypothesized to accelerate rRNA splicing due to their formation at the location of transcription (Berry et al., 2015). It has long been proposed that enhanced reactivity is one of the major functions of other phase-separated nuclear organelles as well (Hancock, 2004; Staněk et al., 2008; Matera et al., 2009; Mao et al., 2011; Sawyer and Dundr, 2016). Cajal bodies, for example, are known to concentrate the RNA and protein components of several RNPs. Although they are not required for the cell survival (Tucker et al., 2001), evidence indicates Cajal bodies accelerate RNP formation (Staněk and Neugebauer, 2004; Klingauf et al., 2006). Recently, the histone locus body was found to be essential to histone mRNA biogenesis by concentrating FLICE-associated huge protein and U7 small nuclear RNP (Tatomer et al., 2016), providing more credence to the view of nuclear subcompartments as reaction localizers.

In the cytosol, mRNP granules, including P-bodies and stress granules, are important for the localization, processing, and degradation of mRNA (see, Adjibade and Mazroui, 2014; Buchan, 2014; Protter and Parker, 2016, for recent reviews). P-bodies contain a high concentration of mRNA decapping factors and experiments in which the decay of mRNA is stalled show that decay intermediates are also localized to P-bodies, suggesting P-bodies are a site of mRNA degradation (Sheth and Parker, 2003; Cougot et al., 2004). This is further supported by the observation that P-bodies shrink in size when mRNAs are trapped in polysomes, and grow in size in response to inhibition of decapping catalysis or 5′ to 3′ degradation (Sheth and Parker, 2003; Cougot et al., 2004). Similar to P-bodies, stress granules are foci of mRNPs implicated in mRNA post-transcriptional regulation (Protter and Parker, 2016). Stress granules form in response to environmental stresses that impede transcription. Through the concentration of mRNA-binding proteins and mRNA, stress granules increase mRNP association rates. One example of this is the recruitment of anti-viral proteins to stress granules, and their subsequent activation, following viral infection (Onomoto et al., 2012; Reineke et al., 2015; Reineke and Lloyd, 2015). Additionally, some viruses have developed mechanisms to suppress stress granule formation, further bolstering the role of stress granules in increasing the activity of anti-viral proteins during immune response (Valiente-Echeverría et al., 2012; Reineke and Lloyd, 2013). FRAP studies of stress granule constituent dynamics suggests mRNA molecules readily exit stress granules with residence times of only a few seconds (Kedersha et al., 2000), and evidence suggests that certain mRNA molecules may be selectively chosen for degradation through association with destabilizing proteins (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006, 2008). In summary, both P-bodies and stress granules serve as transient structures that form and disassemble when transcription rate control is required.

Non-membrane-bound organelles serve as storage depots

Although in many cases non-membrane-bound organelles accelerate biochemical processes by concentrating reactants, there is also evidence for a seemingly contradictory role in the retardation of processes through sequestration. P-bodies, for example, sequester a small subset of mRNA during glucose and protein starvation that are reactivated following refeeding (Brengues, 2005; Arribere et al., 2011; Aizer et al., 2014). Storage of these transcripts could be an efficient way for cells to cope with rapidly changing environments, as opposed to degradation and translation in response to fluctuating stress levels. Stress granules are also intimately related to P-bodies through complex, and still poorly understood, interactions (Hooper and Hilliker, 2013; Buchan, 2014). P-bodies and stress granules dock with one another, and Dhh1/RCK levels appear to shift from P-bodies to stress granules as the duration of stress increases (Wilczynska et al., 2005; Buchan et al., 2008; Mollet et al., 2008). Hence, it seems plausible that mRNA and protein factors move between polysomes, P-bodies, and stress granules in response to stress. The purpose of cytoplasmic granules then could be to both increase mRNP assembly to enhance the rate of mRNA decay, and sequester certain mRNA and proteins that may be harmful to the cell (Hooper and Hilliker, 2013).

Inside the nucleous, small bodies centered around aggregates of PML nuclear bodies contain a diverse array of proteins that are required for functions not directly associated with PML bodies themselves. This has lead to the view of PML bodies as localized storage depots for nuclear proteins (Negorev and Maul, 2001). Yet another example of non-membrane bound organelles acting as repositories are nuclear speckles, which are observed to store splicing factors when splicing is disrupted (O’Keefe et al., 1994).

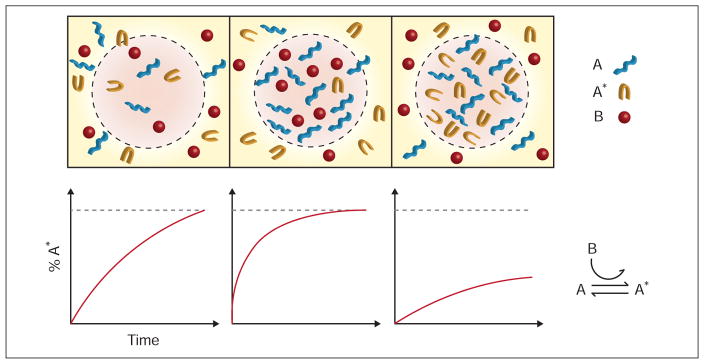

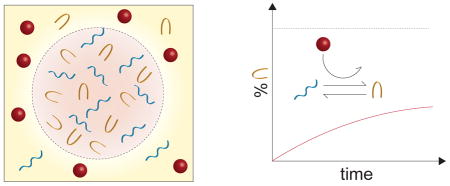

The chemical heterogeneity induced by liquid-liquid phase transitions within the cell both accelerates and decelerates biochemistry. Fig. 2 shows how this might occur in a ternary mixture. In more complex systems, both effects may be present for different molecules within the same non-membrane-bound organelle. For instance, under glucose starvation, P-bodies will assist in the decay of the majority of mRNA, while preserving a subset of ribosomal protein gene RNA (Arribere et al., 2011). While there are clear benefits of slowing undesirable processes while accelerating others at times of rapid environment change, there are still several outstanding questions regarding the biophysical and biochemical mechanisms through which this multifunctionality is achieved. Recent studies indicate that the composition of non-membrane-bound organelles may depend on the abundance of certain multivalent scaffolding proteins (Banani et al., 2016). How compositional control relates to biochemical processing remains unclear. Additionally, the physicochemical features that lead to a certain client macromolecule being sequestered by a scaffold aggregate, while others become increasingly active must be determined. The answer to these questions requires understanding of both the energetics driving phase separation and the kinetics of specific interactions within the condensed phase. Theoretical models based on reaction-diffusion equations (Zwicker et al., 2014, 2015) and mass-action models (Banani et al., 2016) have focused primarily on the formation and stability of non-membrane-bound organelles. Tying these models to organelle function provides an exciting future challenge for experimental and theoretical biophysicists.

Figure 2. Phase-separated regulation of chaperone-assisted folding.

The top panel shows three possible mixtures of a protein, which can be in an unfolded conformation A, or folded conformation A*, and chaperone B that catalyzes the transition from A to A*. The bottom panel displays schematic progress curves for the folding of A, corresponding to the mixtures directly above. The left column shows a well-mixed case, in which the reaction proceeds at a moderate pace. In the middle column, the mixture separates into a phase rich in proteins in the unfolded conformation and chaperones, catalyzing the transition of A to A*. In the right column, the mixture forms a phase devoid of chaperones, effectively sequestering proteins in conformation A.

Discussion

The increased interest in non-membrane-bound organelles over the past decade has lead to a paradigm shift in our understanding of cellular organization. The prevalence of non-membrane-bound organelles indicates that organization extends across all cellular scales and is a far more dynamic than previously thought. Indeed, it has become clear that cells utilize liquid-liquid phase transitions to transiently organize both the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm in order to up-regulate some processes while down-regulating others. Although classical theory for polymer phase transitions provides a useful conceptual framework, recent studies highlighting the importance of protein multivalency (Li et al., 2012; Banani et al., 2016) and intrinsic disorder (Uversky et al., 2015; Nott et al., 2015), and non-equilibrium energy flux in the form of ATP (Brangwynne et al., 2011; Elbaum-Garfinkle et al., 2015), show that more nuanced theory is needed to describe intracellular phase transitions. This is further motivated by the observations that abundance of certain proteins that provide scaffolding for less aggregation-prone client proteins can regulate the composition of non-membrane-bound organelles.

The formation of non-membrane-bound organelles is a multi-step process

One possibility is that the formation of non-membrane-bound organelles is a multi-step process, where the first step involves the formation of an initial scaffolding, which then recruits client proteins and RNAs. The initial formations may occur through several different mechanisms. One pathway has been observed in several model systems involving charged proteins with intrinsic disorder (Li et al., 2012; Nott et al., 2015; Pak et al., 2016), called complex coacervation, in which a polymer solution phase separates into a dense phase and a disperse phase with polycations and polyanions present in both phases to limit like-charge repulsions (Veis, 2011). Another pathway may be the formation of cross-β-sheet structures, similar to amyloid fibril formation. This has been implicated in the early formation of the Balbani body in oocytes (Boke et al., 2016). Prion-like domains and low-complexity domains, which promote β-strand formation, are important to the formation of paraspeckles, P-bodies, and stress granules (Hennig et al., 2015; Hanazawa et al., 2011; Molliex et al., 2015; Protter and Parker, 2016). Recently, cross-β-sheet structures were observed to form after liquid-liquid phase separation, stabilizing the condensed phase, suggesting that both complex coacervation and hydrogen-bonding β-strands may work together to support non-membrane-bound organelle formation (Lin et al., 2015). Once these initial proteins have separated, they act as a scaffold of tethered, charged proteins that provide a network of binding sites for client RNA and proteins. The proteinaceous web assembled by the initial phase separation may then serve to both capture client molecules and direct their interactions, in a manner similar to profilin and formins during actin filament assembly.

The compartmentalization of non-membrane and membrane bound organelles serve distinct physiological purposes

The emerging view of non-membrane-bound organelle structure and functions, in which a network of scaffolding proteins localizes and facilitates client molecule interactions, differs from the compartmentalization of membrane-bound organelles in a fundamental way: membranes concentrate client molecules by placing a barrier at the periphery, whereas non-membrane-bound organelles concentrate by means of a system of tethers holding molecules from the middle. A useful analogy might be that of keeping a herd of horses from running away. Either a fence can be constructed around a pasture, or the horses themselves can be tethered to a hitching post. In actuality, weak interactions between scaffolding proteins make the scaffold highly dynamic and imbue non-membrane-bound organelles with their liquid-like properties. The cell readily makes use of both modes of compartmentalization, albeit at different scales and for different purposes.

In this way, the function of non-membrane-bound organelles is tightly linked to the physicochemical processes leading to their partitioning from the nucleoplasm and cytoplasm. Whereas some molecules are recruited to non-membrane-bound organelles to enhance their reaction rate, other macromolecules may be sequestered in order to slow a process, such as mRNA translation during glucose starvation (Brengues, 2005). A better understanding of non-membrane-bound organelles will provide much needed insight into how cells efficiently and simultaneously control a diverse sets of chemical reactions in the crowded cell interior. One possibility is that non-membrane-bound organelle formation acts as an on-off switch while the rates of specific reactions are fine-tuned by the macromolecular composition of the formed organelles.

How does the biophysical chemistry of non-membrane-bound organelles dictate organelle physiology?

Significant attention has been paid to the structural, functional, and dynamic bases for the formation of non-membrane-bound organelles. However, we are just beginning to understand the biophysical chemistry and kinetics of reactions inside non-membrane-bound organelles. The size distribution of non-membrane-bound organelles also presents some interesting questions. First, the size of non-membrane-bound organelles sits in between the length scales of macromolecules (~1 nm) and membrane-bound organelles (~1μm). What physical principles can explain this? Is there an advantage to tethering molecules together at scales of 10–100 nm that decreases as the size of the aggregate grows, or is the advantage related to increased functionality as a reaction catalyst? Related to this, how do reaction rates depend on the size distributions of membrane-free organelles? Since densely crowded environments slow diffusion, and hence may limit reaction rates, one possibility is that smaller organelles facilitate reactions, whereas larger organelles behave more like storage depots. Clearly, the details of the relation between size scaling, structure, and function will be far more nuanced, but answering these questions should provide a useful start. Further knowledge of non-membrane-bound organelle functioning will rely on careful dissection of the organelle formation, composition, and activity. Particularly interesting would be measurements of reaction rates as a function of condensed-phase volume fraction and composition. Lastly, continued research in this area will enhance our understanding of normal non-membrane-bound function, as well as their increasingly-important role in disease (see, Li et al., 2013; Anderson et al., 2015; Aguzzi and Altmeyer, 2016, for recent reviews).

Do we need to revise theories of origin of life and cells?

Non-membrane-bound organelles also present some intriguing questions with regard to the origin of life. Macromolecular organization has long been associated with the earliest stages of life, and the notion that this organization was the result of phase separation in a complex fluid was first proposed nearly 90 years ago (Oparin and Morgulis, 1938). Although the original idea that this first stage of organization occurred in a “primordial soup” now seems unlikely, in part because the concentration of such a mixture would require huge quantities of organic molecules, current origin-of-life theories suggest the pores of alkaline hydrothermal vents provide excellent environments for macromolecular synthesis and interaction (Martin et al., 2008). The narrow pores of these vents also may have crowded early macromolecules to provide the necessary conditions for phase separation in much the same way as the crowded cytoplasm in cells (Spitzer and Poolman, 2009). In this sense, non-membrane-bound organelles may have been precursors to membrane-bound life. Interestingly, a theoretical study of active emulsions showed that spherical droplets can spontaneously divide into two daughter droplets in a process resembling mitosis (Zwicker et al., 2016). The role of active droplets in the emergence of cells is an exciting and underexplored avenue of research.

The basic need for organization across all forms of life suggests non-membrane-bound organelles were likely essential components of the endosymbiants discussed by Sagan (1967). The “9+2” basal bodies are one such example. The endosymbiotic incorporation of mitochondria into archaea, which allowed energy production to scale freely with cell volume, catalyzed the emergence of far more complex eukaryotic cells. The increased production capacity afforded by mitochondria also created a need for greater organization of the increasingly-diverse intracellular environment, enhancing the importance of non-membrane-bound organelles. In this way, the origin of eukaryotes is inextricably linked to both membrane-bound mitochondria, which allowed for the productions of vast numbers of new molecules, and the numerous non-membrane-bound organelles that organized them into functional components.

Highlights.

Recent research on the formation and function of non-membrane-bound organelles is reviewed.

The function of non-membrane-bound organelles is closely tied to their formation.

Future research questions on the function of non-membrane-bound organelles are presented.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by the University of Michigan Protein Folding Diseases Initiative. Dr. Stroberg is a fellow of the Michigan IRACDA program (NIH grant: K12 GM111725). We are grateful to Suzanne K. Shoffner (University of Michigan) for her suggestions and comments.

Footnotes

For example, the endosymbiotic hosts of the earliest eukaryotes are now believed to be Archaea, though it is difficult to fault Margulis, as Archaea were not discovered until a decade after the publishing of her manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adjibade P, Mazroui R. Control of mRNA turnover: Implication of cytoplasmic RNA granules. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2014;34:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S, Snaidero N, Pähler G, Frey S, Sánchez P, Zweckstetter M, Janshoff A, Schneider A, Weil MT, Schaap IAT, Görlich D, Simons M. Myelin Membrane Assembly Is Driven by a Phase Transition of Myelin Basic Proteins Into a Cohesive Protein Meshwork. PLoS Biology. 2013;11(6):e1001577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguzzi A, Altmeyer M. Phase Separation: Linking Cellular Compartmentalization to Disease. Trends in Cell Biology. 2016;26(7):547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizer A, Kalo A, Kafri P, Shraga A, Ben-Yishay R, Jacob A, Kinor N, Shav-Tal Y. Quantifying mRNA targeting to P-bodies in living human cells reveals their dual role in mRNA decay and storage. Journal of Cell Science. 2014;127(20):4443–4456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.152975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;172(6):803–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2008;33(3):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N, Ivanov P. Stress granules, P-bodies and cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2015;1849(7):861–870. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribere JA, Doudna JA, Gilbert WV. Reconsidering movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and P bodies. Molecular Cell. 2011;44(5):745–758. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banani SF, Rice AM, Peeples WB, Lin Y, Jain S, Parker R, Rosen MK. Compositional Control of Phase-Separated Cellular Bodies. Cell. 2016;166(3):651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjade S, Rosen MK. Phase transitions of multivalent proteins can promote clustering of membrane receptors. eLife. 2014;3:e04123. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banjade S, Wu Q, Mittal A, Peeples WB, Pappu RV, Rosen MK. Conserved interdomain linker promotes phase separation of the multivalent adaptor protein Nck. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(47):E6426–6435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508778112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron-Sandoval LP, Safaee N, Michnick SW. Mechanisms and Consequences of Macromolecular Phase Separation. Cell. 2016;165(5):1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry J, Weber SC, Vaidya N, Haataja M, Brangwynne CP. RNA transcription modulates phase transition-driven nuclear body assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(38):E5237–5245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509317112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boke E, Ruer M, Wühr M, Coughlin M, Lemaitre R, Gygi SP, Alberti S, Drechsel D, Hyman AA, Mitchison TJ. Amyloid-like Self-Assembly of a Cellular Compartment. Cell. 2016;166(3):637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec M, Daicic J, Koper GJ. On the difference in ionization properties between planar interfaces and linear polyelectrolytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(8):3499–3503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne CP, Eckmann CR, Courson DS, Rybarska A, Hoege C, Gharakhani J, Jülicher F, Hyman AA. Germline P Granules Are Liquid Droplets That Localize by Controlled Dissolution/Condensation. Science. 2009;324(5935):1729–1732. doi: 10.1126/science.1172046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne CP, Mitchison TJ, Hyman AA. Active liquid-like behavior of nucleoli determines their size and shape in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(11):4334–4339. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017150108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brangwynne CP, Tompa P, Pappu RV. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nature Physics. 2015;11(11):899–904. [Google Scholar]

- Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of Eukaryotic mRNAs Between Polysomes and Cytoplasmic Processing Bodies. Science. 2005;310(5747):486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan JR. mRNP granules. RNA biology. 2014;11(8):1019–1030. doi: 10.4161/15476286.2014.972208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan JR, Muhlrad D, Parker R. P bodies promote stress granule assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of Cell Biology. 2008;183(3):441–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougot N, Babajko S, Séraphin B. Cytoplasmic foci are sites of mRNA decay in human cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;165(1):31–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courchaine EM, Lu A, Neugebauer KM. Droplet organelles? The EMBO Journal. 2016;35(15):1603–1612. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos DP, Gräf R, Field MC. Evolution of the nucleus. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2014;28(1):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Kim Y, Szczepaniak K, Chen CCH, Eckmann CR, Myong S, Brangwynne CP. The disordered P granule protein LAF-1 drives phase separation into droplets with tunable viscosity and dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(23):7189–7194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embley TM, Martin W. Eukaryotic evolution, changes and challenges. Nature. 2006;440(7084):623–630. doi: 10.1038/nature04546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory PJ. Principles of polymer chemistry. Cornell University Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Fox AH, Lamond AI. Paraspeckles. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2010;2(7):a000687. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine M, Senger B, Saveanu C, Fasiolo F. Ribosome assembly in eukaryotes. Gene. 2003;313(1–2):17–42. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00629-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés J, Madurga S, Rey-Castro C, Mas F. Dealing with long-range interactions in the determination of polyelectrolyte ionization properties. Extension of the transfer matrix formalism to the full range of ionic strengths. Journal of Polymer Science, Part B: Polymer Physics. 2017;55(3):275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena SR, Ruis BL, Meyer JA, Kapoor M, Conklin KF. NOM1 targets protein phosphatase I to the nucleolus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(1):398–404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanazawa M, Yonetani M, Sugimoto A. PGL proteins self associate and bind RNPs to mediate germ granule assembly in C. elegans. Journal of Cell Biology. 2011;192(6):929–937. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock R. A role for macromolecular crowding effects in the assembly and function of compartments in the nucleus. Journal of Structural Biology. 2004;146(3):281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerger KE, Cordero JA, Gall JG. Cajal Bodies, Nucleoli, and Speckles in the Xenopus Oocyte Nucleus Have a Low-Density, Sponge-like Structure. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2005;16(8):1–13. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennig S, Kong G, Mannen T, Sadowska A, Kobelke S, Blythe A, Knott GJ, Iyer SS, Ho D, Newcombe EA, Hosoki K, Goshima N, Kawaguchi T, Hatters D, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Hirose T, Bond CS, Fox AH. Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles. Journal of Cell Biology. 2015;210(4):529–539. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper C, Hilliker A. Packing them up and dusting them off: RNA helicases and mRNA storage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2013;1829(8):824–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubstenberger A, Noble SL, Cameron C, Evans TC. Translation repressors, an RNA helicase, and developmental cues control RNP phase transitions during early development. Developmental Cell. 2013;27(2):161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman AA, Weber CA, Jülicher F. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in Biology. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2014;30:39–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs WM, Frenkel D. Phase Transitions in Biological Systems with Many Components. Biophysical Journal. 2017;112(4):683–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Cho MR, Li W, Yacono PW, Chen S, Gilks N, Golan DE, Anderson P. Dynamic shuttling of TIA-1 accompanies the recruitment of mRNA to mammalian stress granules. Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;151(6):1257–1268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurts S, Masutomi K, Delgermaa L, Arai K, Oishi N, Mizuno H, Hayashi N, Hahn WC, Murakami S. Nucleolin interacts with telomerase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(49):51508–51515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingauf M, Stanĕk D, Neugebauer KM. Enhancement of U4/U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle association in Cajal bodies predicted by mathematical modeling. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(12):4972–4981. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman R. Fractal Reaction Kinetics. Science. 1988;241(4873):1620–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Banjade S, Cheng HC, Kim S, Chen B, Guo L, Llaguno M, Hollingsworth JV, King DS, Banani SF, Russo PS, Jiang QX, Nixon BT, Rosen MK. Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature. 2012;483(7389):336–340. doi: 10.1038/nature10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YR, King OD, Shorter J, Gitler AD. Stress granules as crucibles of ALS pathogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;201(3):361–372. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201302044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Protter DSW, Rosen MK, Parker R. Formation and Maturation of Phase-Separated Liquid Droplets by RNA-Binding Proteins. Molecular Cell. 2015;60(2):208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipfert J, Doniach S, Das R, Herschlag D. Understanding nucleic acid-ion interactions. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2014;83:813–841. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky NG, Pedersen PL. Mitochondrial turnover in animal cells. Half-lives of mitochondria and mitochondrial subfractions of rat liver based on [14C]bicarbonate incorporation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1981;256(16):8652–8657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde BM, Moore C, Varani G. RNA-binding proteins: modular design for efficient function. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(6):479–490. doi: 10.1038/nrm2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao YS, Zhang B, Spector DL. Biogenesis and function of nuclear bodies. Trends in Genetics. 2011;27(8):295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, Baross J, Kelley D, Russell M. Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:805–814. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera AG, Izaguire-Sierra M, Praveen K, Rajendra TK. Nuclear Bodies: Random Aggregates of Sticky Proteins or Crucibles of Macromolecular Assembly? Developmental Cell. 2009;17(5):639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrea DM, Kriwacki RW. Phase separation in biology; functional organization of a higher order. Cell Communication and Signaling. 2016;14(1) doi: 10.1186/s12964-015-0125-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollet S, Cougot N, Wilczynska A, Dautry F, Kress M, Bertrand E, Weil D. Translationally repressed mRNA transiently cycles through stress granules during stress. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19(10):4469–4479. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliex A, Temirov J, Lee J, Coughlin M, Kanagaraj AP, Kim HJ, Mittag T, Taylor JP. Phase Separation by Low Complexity Domains Promotes Stress Granule Assembly and Drives Pathological Fibrillization. Cell. 2015;163(1):123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourão MA, Hakim JB, Schnell S. Connecting the Dots: The Effects of Macromolecular Crowding on Cell Physiology. Biophysical Journal. 2014;107(12):2761–2766. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negorev D, Maul GG. Cellular proteins localized at and interacting within ND10/PML nuclear bodies/PODs suggest functions of a nuclear depot. Oncogene. 2001;20(49):7234–7242. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nott TJ, Petsalaki E, Farber P, Jervis D, Fussner E, Plochowietz A, Craggs TD, Bazett-Jones DP, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Baldwin AJ. Phase Transition of a Disordered Nuage Protein Generates Environmentally Responsive Membraneless Organelles. Molecular Cell. 2015;57(5):936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe RT, Mayeda A, Sadowski CL, Krainer AR, Spector DL. Disruption of pre-mRNA splicing in vivo results in reorganization of splicing factors. Journal of Cell Biology. 1994;124(3):249–260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.3.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MOJ, Hingorani K, Szebeni A. Conventional and non-conventional roles of the nucleolus. International Review of Cytology. 2002;219:199–266. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(02)19014-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onomoto K, Jogi M, Yoo JS, Narita R, Morimoto S, Takemura A, Sambhara S, Kawaguchi A, Osari S, Nagata K, Matsumiya T, Namiki H, Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Critical role of an antiviral stress granule containing RIG-I and PKR in viral detection and innate immunity. PLoS ONE. 2012 Aug;7(8):e43031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oparin AI, Morgulis S. The Origin of Life. Macmillan; New York: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek JTG, Voorn MJ. Phase separation in polyelectrolyte solutions; theory of complex coacervation. Journal of Cellular Physiology Supplement. 1957;49(S1):7–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak CW, Kosno M, Holehouse AS, Padrick SB, Mittal A, Ali R, Yunus AA, Liu DR, Pappu RV, Rosen MK. Sequence Determinants of Intracellular Phase Separation by Complex Coacervation of a Disordered Protein. Molecular Cell. 2016;63(1):72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel A, Lee HO, Jawerth L, Maharana S, Jahnel M, Hein MY, Stoynov S, Mahamid J, Saha S, Franzmann TM, Pozniakovski A, Poser I, Maghelli N, Royer LA, Weigert M, Myers EW, Grill S, Drechsel D, Hyman AA, Alberti S. A Liquid-to-Solid Phase Transition of the ALS Protein FUS Accelerated by Disease Mutation. Cell. 2015;162(5):1066–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulice L, Vilaseca E, Pastor I, Madurga S, Garcés JL, Isvoran A, Mas F. Monte Carlo simulations of enzymatic reactions in crowded media. Effect of the enzyme-obstacle relative size. Mathematical Biosciences. 2014;251(1):72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protter DSW, Parker R. Principles and Properties of Stress Granules. Trends in Cell Biology. 2016;26(9):668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke LC, Kedersha N, Langereis MA, van Kuppeveld FJM, Lloyd RE. Stress granules regulate double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase activation through a complex containing G3BP1 and Caprin1. mBio. 2015;6(2):e02486–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02486-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke LC, Lloyd RE. Diversion of stress granules and P-bodies during viral infection. Virology. 2013;436(2):255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reineke LC, Lloyd RE. The stress granule protein G3BP1 recruits protein kinase R to promote multiple innate immune antiviral responses. Journal of Virology. 2015;89(5):2575–2589. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02791-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubbi CP, Milner J. Disruption of the nucleolus mediates stabilization of p53 in response to DNA damage and other stresses. The EMBO Journal. 2003;22(22):6068–6077. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagan L. On the origin of mitosing cells. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1967;14(3):225–274. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(67)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer IA, Dundr M. Nuclear bodies: Built to boost. Journal of Cell Biology. 2016;213(5):509–511. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201605049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell S, Turner TE. Reaction kinetics in intracellular environments with macromolecular crowding: Simulations and rate laws. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2004;85(2–3):235–260. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shellman ER, Chen Y, Lin X, Burant CF, Schnell S. Metabolic network motifs can provide novel insights into evolution: The evolutionary origin of Eukaryotic organelles as a case study. Computational Biology and Chemistry. 2014;53(PB):242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth U, Parker R. Decapping and decay of messenger RNA occur in cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2003;300(5620):805–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1082320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer J, Poolman B. The Role of Biomacromolecular Crowding, Ionic Strength, and Physicochemical Gradients in the Complexities of Life’s Emergence. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2009;73(2):371–388. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00010-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staněk D, Neugebauer KM. Detection of snRNP assembly intermediates in Cajal bodies by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Journal of Cell Biology. 2004;166(7):1015–1025. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staněk D, Pidalová-Hnilicová J, Novotný I, Huranová M, Blažíková M, Wen X, Sapra AK, Neugebauer KM. Spliceosomal Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Particles Repeatedly Cycle through Cajal Bodies. Molecular biology of the cell. 2008;19(6):2534–2543. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecka M, Trowitzsch S, Weber G, Lührmann R, Oates AC, Neugebauer KM. Coilin-dependent snRNP assembly is essential for zebrafish embryogenesis. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2010;17(4):403–409. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatomer DC, Terzo E, Curry KP, Salzler H, Sabath I, Zapotoczny G, McKay DJ, Dominski Z, Marzluff WF, Duronio RJ. Concentrating pre-mRNA processing factors in the histone locus body facilitates efficient histone mRNA biogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology. 2016;213(5):557–570. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E, Ferreira-Cerca S, Hurt E. Eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 2013;126(21):4815–4821. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toretsky JA, Wright PE. Assemblages: Functional units formed by cellular phase separation. Journal of Cell Biology. 2014;206(5):579–588. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker KE, Berciano MT, Jacobs EY, LePage DF, Shpargel KB, Rossire JJ, Chan EKL, Lafarga M, Conlon RA, Matera AG. Residual Cajal bodies in coilin knockout mice fail to recruit Sm snRNPs and SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy gene product. Journal of Cell Biology. 2001;154(2):293–307. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uversky VN, Kuznetsova IM, Turoverov KK, Zaslavsky B. Intrinsically disordered proteins as crucial constituents of cellular aqueous two phase systems and coacervates. FEBS Letters. 2015;589(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Echeverría F, Melnychuk L, Mouland AJ. Viral modulation of stress granules. Virus Research. 2012;169(2):430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veis A. A review of the early development of the thermodynamics of the complex coacervation phase separation. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 2011;167(1–2):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JT, Smith J, Chen BC, Schmidt H, Rasoloson D, Paix A, Lambrus BG, Calidas D, Betzig E, Seydoux G. Regulation of RNA granule dynamics by phosphorylation of serine-rich, intrinsically disordered proteins in C. elegans. eLife. 2014;3:e04591. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber SC, Brangwynne CP. Getting RNA and protein in phase. Cell. 2012;149(6):1188–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber SC, Brangwynne CP. Inverse size scaling of the nucleolus by a concentration-dependent phase transition. Current Biology. 2015;25(5):641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynska A, Aigueperse C, Kress M, Dautry F, Weil D. The translational regulator CPEB1 provides a link between dcp1 bodies and stress granules. Journal of Cell Science. 2005;118(5):981–992. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wippich F, Bodenmiller B, Trajkovska MG, Wanka S, Aebersold R, Pelkmans L. Dual specificity kinase DYRK3 couples stress granule condensation/dissolution to mTORC1 signaling. Cell. 2013;152(4):791–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff JB, Wueseke O, Viscardi V, Mahamid J, Ochoa SD, Bunkenborg J, Widlund PO, Pozniakovsky A, Zanin E, Bahmanyar S, Zinke A, Hong SH, Decker M, Baumeister W, Andersen JS, Oegema K, Hyman AA. Regulated assembly of a supramolecular centrosome scaffold in vitro. Science. 2015;348(6236):808–812. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou HX, Rivas G, Minton AP. Macromolecular crowding and confinement: biochemical, biophysical, and potential physiological consequences. Annual Review of Biophysics. 2008;37(1):375–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker D, Decker M, Jaensch S, Hyman AA, Jülicher F. Centrosomes are autocatalytic droplets of pericentriolar material organized by centrioles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(26):E2636–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404855111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker D, Hyman AA, Jülicher F. Suppression of Ostwald ripening in active emulsions. Physical Review E - Statistical, Nonlinear, and Soft Matter Physics. 2015;92:012317. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.012317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker D, Seyboldt R, Weber CA, Hyman AA, Jülicher F. Growth and division of active droplets provides a model for protocells. Nature Physics. 2017;13(4):408–413. [Google Scholar]