ABSTRACT

Source attribution studies report that the consumption of contaminated poultry is the primary source for acquiring human campylobacteriosis. Oral administration of an engineered Escherichia coli strain expressing the Campylobacter jejuni N-glycan reduces bacterial colonization in specific-pathogen-free leghorn chickens, but only a fraction of birds respond to vaccination. Optimization of the vaccine for commercial broiler chickens has great potential to prevent the entry of the pathogen into the food chain. Here, we tested the same vaccination approach in broiler chickens and observed similar efficacies in pathogen load reduction, stimulation of the host IgY response, the lack of C. jejuni resistance development, uniformity in microbial gut composition, and the bimodal response to treatment. Gut microbiota analysis of leghorn and broiler vaccine responders identified one member of Clostridiales cluster XIVa, Anaerosporobacter mobilis, that was significantly more abundant in responder birds. In broiler chickens, coadministration of the live vaccine with A. mobilis or Lactobacillus reuteri, a commonly used probiotic, resulted in increased vaccine efficacy, antibody responses, and weight gain. To investigate whether the responder-nonresponder effect was due to the selection of a C. jejuni “supercolonizer mutant” with altered phase-variable genes, we analyzed all poly(G)-containing loci of the input strain compared to nonresponder colony isolates and found no evidence of phase state selection. However, untargeted nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics identified a potential biomarker negatively correlated with C. jejuni colonization levels that is possibly linked to increased microbial diversity in this subgroup. The comprehensive methods used to examine the bimodality of the vaccine response provide several opportunities to improve the C. jejuni vaccine and the efficacy of any vaccination strategy.

IMPORTANCE Campylobacter jejuni is a common cause of human diarrheal disease worldwide and is listed by the World Health Organization as a high-priority pathogen. C. jejuni infection typically occurs through the ingestion of contaminated chicken meat, so many efforts are targeted at reducing C. jejuni levels at the source. We previously developed a vaccine that reduces C. jejuni levels in egg-laying chickens. In this study, we improved vaccine performance in meat birds by supplementing the vaccine with probiotics. In addition, we demonstrated that C. jejuni colonization levels in chickens are negatively correlated with the abundance of clostridia, another group of common gut microbes. We describe new methods for vaccine optimization that will assist in improving the C. jejuni vaccine and other vaccines under development.

KEYWORDS: Campylobacter, poultry, probiotics, vaccine, glycoengineering, metabolomics

INTRODUCTION

Campylobacter jejuni is the leading cause of bacterial foodborne illness worldwide (1) and a major public health concern. In humans, C. jejuni infection is usually self-limiting, but postinfectious complications can include development of the peripheral neuropathy known as Guillain-Barré syndrome and bowel diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome (2). Furthermore, in a multisite birth cohort study in 8 low-resource countries, Campylobacter-positive stool samples were collected from 85% of infants by the age of 1 year. The presence of the organism was associated with increased intestinal permeability and inflammation and lower age-for-length scores, often referred to as growth stunting (3).

Poultry meat is the main source for the acquisition of human campylobacteriosis (4). Broiler flocks typically become contaminated with C. jejuni 2 weeks after hatching and can harbor 108 to 109 CFU/g of cecal content at the day of slaughter (5 to 6 weeks of age) (5). Calculations based on mathematical modeling indicate that decreasing the levels of C. jejuni colonization in chickens by 2 log10 units would decrease the number of human campylobacteriosis cases 30-fold, and a reduction by 3 log10 units would diminish the public health risk by at least 90% (6, 7). Various control mechanisms to reduce C. jejuni colonization levels in poultry have been described, including hygiene and biosecurity practices, bacteriophage therapy, prebiotics, probiotics, bacteriocins, and vaccination (8–10). Although biosecurity measures have the potential to reduce the contamination of meat during slaughter, vaccination of poultry is considered the most promising solution to decrease C. jejuni levels at the source and to reduce the rate of human infections. de Zoete et al. (11) described various vaccination approaches to reduce C. jejuni, including the use of killed C. jejuni whole cells (12); live Salmonella-vectored vaccines (13–15); encapsulated-particle vaccines (16); and parenteral, oral, nasal, or intramuscular subunit vaccines comprised of recombinant peptides (17), virulence factors, outer membrane proteins, flagellin, or transport proteins (18). Recent studies have investigated the importance of C. jejuni capsular polysaccharides (CPS) in various models (19–22), including chickens (23), and their potential as a vaccine antigen for human use. However, the facts that 47 different CPS serotypes have been described and that CPS itself is phase variable and nonstoichiometrically decorated with various modifications will make it difficult to achieve broad coverage with a CPS-based vaccine (19–21, 24). In general, the genetic diversity among C. jejuni isolates, coupled with the observations that most phase-variable (PV) genes encode enzymes involved in the synthesis or modification of surface structures such as lipooligosaccharide (LOS), CPS, and flagella (25, 26) and that multiple C. jejuni strains can be present in broiler flocks at the same time (27), adds another level of complexity when it comes to choosing an appropriate antigen for vaccination. The N-glycan is an ideal vaccine candidate since it is an immunogenic, constitutively expressed, non-phase-variable surface structure that is conserved in all C. jejuni isolates (88).

Poultry producers began using antibiotics in the 1940s, but due to the spread of antibiotic resistance, European Union countries phased out the use of antibiotics for the sole purpose of growth promotion in the agricultural livestock industry between 1996 and 2007 (28). In contrast, until recently, most major U.S. poultry companies administered low, subtherapeutic doses of antibiotics to improve feed conversion efficiency and to promote growth. In order to prepare for the future ban on the use of antibiotics in North America, there is a growing need for new nonantibiotic alternatives to improve bird performance and simultaneously prevent the spread of zoonotic pathogens of human health importance, such as C. jejuni. Probiotics are already widely used as an alternative to antibiotics (9, 29, 30) in order to improve feed conversion. Several studies, with various results, also described the use of food additives, including oligofructose or organic acids (31, 32), in addition to single or mixed cultures of bacteria such as Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, and Bifidobacterium species to reduce C. jejuni levels in chickens (9). Probiotics were also shown to improve vaccine efficacy in chickens immunized against coccidiosis (33) or Newcastle and infectious bursal disease viruses (34) and during passive immunization against various Salmonella enterica serotypes (35).

We recently described the first C. jejuni glycoconjugate vaccine for use in livestock (36). The vaccine is comprised of a nonvariable and universally expressed C. jejuni N-glycan structure engineered onto the surface of live Escherichia coli cells. This vaccine significantly reduces C. jejuni colonization in specific-pathogen-free (SPF) leghorn chickens (36). We now demonstrate that the live E. coli vaccine also reduces C. jejuni colonization in broiler chickens. Challenge experiments showed a bimodal response to vaccination in both leghorn and broiler chickens that corresponded to shared differences in the microbes inhabiting chicken ceca, particularly among members of the Clostridiales order. Anaerosporobacter mobilis was one of the organisms identified to be significantly more abundant in both leghorn and broiler responders. Therefore, broiler chickens were vaccinated with the same E. coli vaccine coadministered with A. mobilis or with a Lactobacillus reuteri strain that was previously isolated from chickens (37) and identified as a robust colonizer in our in vivo competition assay. Vaccine supplementation with either probiotic improved weight gain, vaccine persistence, the N-glycan immune response, and C. jejuni clearance. Further characterization of the remaining C. jejuni persisters revealed that there is no selection for altered phase variants that may better colonize poultry. However, metabolomic profiling of the cecal contents of all birds in this study identified a potential biomarker that is associated with C. jejuni clearance.

RESULTS

The N-glycan-based E. coli live vaccine reduces C. jejuni colonization in broiler chickens.

We previously reported that two-dose vaccination on days 7 and 21 with the live E. coli vaccine reduces colonization in leghorn chickens, induces an N-glycan-specific immune response, and has no effect on the diversity of the gut microbiota (36). We then performed similar experiments to test the live vaccine in broiler chickens. In the first experiment, we determined the C. jejuni challenge dose in a 35-day broiler chicken challenge model. Birds were given 1 × 104 or 1 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni 81-176 by oral gavage. On day 35, C. jejuni counts in the cecum were determined. No C. jejuni cells could be found when birds were challenged with 1 × 104 CFU, but 100% colonization, with a mean of 9.2 × 108 CFU/g cecal content, was observed when birds were challenged with 1 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni. No C. jejuni bacteria were detected in nonchallenged birds (results not shown).

Next, we tested the efficacy of the live E. coli vaccine. Broiler birds were given 1 × 108 E. coli CFU by oral gavage on day 7 and day 21 and challenged with 1 × 106 C. jejuni on day 28. The nonvaccinated control group that was challenged with 1 × 106 C. jejuni on day 28 showed colonization levels that ranged from 4.8 × 108 to 2.28 × 109 CFU/g cecal content (Fig. 1A, bottom), comparable to the results of our dose experiment. Administration of the E. coli vaccine resulted in a statistically significant reduction in bacterial colonization (P = 0.0104) after challenge. However, we observed a bimodal response to vaccination. In one subset of birds (2 out of 6), C. jejuni colonization was completely abolished, whereas another subset of birds (4 out of 6) still had low levels of C. jejuni present on day 35, which ranged from 1.6 × 105 to 1.2 × 106 CFU/g cecal content (Fig. 1A). A similar bimodal response to the vaccine was previously observed after vaccination of SPF leghorn chickens (Fig. 1A, top) (36). No C. jejuni bacteria were observed in the negative-control birds above our detection limit of 2 × 102 CFU/g cecal content.

FIG 1.

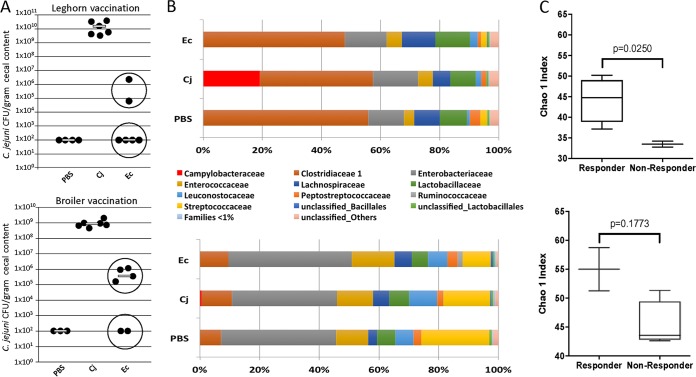

Comparison of responder and nonresponder groups of SPF leghorn and broiler chickens after vaccination. (A) Colonization levels of C. jejuni 81-176. Birds in the negative-control group (PBS) were nonvaccinated and nonchallenged; birds in the positive-control groups (Cj) were nonvaccinated but challenged with either 1 × 102 CFU (in leghorn chickens) or 1 × 106 CFU (in broiler chickens) of C. jejuni 81-176 on day 28. Birds in the treatment groups (n = 6 for leghorn and broiler chickens) were given 1 × 108 cells of the E. coli vaccine (Ec) by oral gavage on days 7 and 21 and challenged with either 1 × 102 CFU (leghorn chickens) or 1 × 106 CFU (broiler chickens) C. jejuni 81-176 on day 28. Lines represent the median levels of colonization. (B) The gut microbiota in cecal samples of leghorn (top) and broiler (bottom) chickens obtained on the day of euthanasia were compared at the family level. Although both strains share taxonomic groups, their abundances differ between the strains. Members of Clostridiaceae family 1 dominate the gut microbiome of leghorn chickens, while Enterobacteriaceae dominate the gut microbiome of broiler chickens. (C) Analysis of alpha diversity indexes between the indicated (circled in panel A) responder groups (n = 4 leghorn chickens and n = 2 broiler chickens) and nonresponder groups (n = 2 leghorn chickens and n = 4 broiler chickens) in each experiment shows that both leghorn (top) and broiler (bottom) responders have higher alpha diversity indexes. Statistics were analyzed by an unpaired t test with Welch's correction. Lines and bars represent means and standard deviations.

Changes in alpha diversity and composition of gut microbial communities associated with the vaccine response.

Since a bimodal response to vaccination was observed in the broiler birds, we analyzed and compared the compositions of the microbiota of responders and nonresponders at the culmination of the experiment. We also reanalyzed the microbial composition from our previously reported experiment with leghorn chickens that showed the same responder-nonresponder effect (36). Although we noted some similarities in the taxonomic groups present in the cecal contents of leghorn and broiler birds, their abundances differed between the breeds. Members of Clostridiaceae family 1 dominate the gut microbiome of leghorn chickens, while Enterobacteriaceae dominate the gut microbiome of broiler chickens (Fig. 1B). When comparing the microbiomes between responders (4 out of 6 leghorn chickens and 2 out of 6 broiler chickens) and nonresponders (2 out 6 leghorn chickens and 4 out of 6 broiler chickens) for each strain, we observed similar trends in the abundances of some taxa in both the leghorn and broiler chicken experiments (Tables 1 and 2). In addition to other differences, one member of cluster XIVa of the low-G+C-content Clostridiales group, Anaerosporobacter mobilis, was present at a significantly higher abundance in both leghorn and broiler responders and was selected for use in the trials with probiotics described below. Interestingly, the level of Lactobacillus reuteri, a species often described as being a beneficial probiotic in multiple human and animal feeding studies, including studies of poultry, was found to be decreased in responders compared to nonresponders (Table 2). Thus, we decided to test if its enrichment in the chicken gut was able to improve vaccine efficacy. Furthermore, in both chicken breeds, alpha diversity was increased in the responder group (Fig. 1C).

TABLE 1.

Increases in relative abundances of operational taxonomic units between responders and nonresponders observed in both SPF leghorn and broiler chickens

| OTU | Organism | Fold increase in relative abundance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leghorn chickens |

Broiler chickens |

||||

| Responders | Nonresponders | Responders | Nonresponders | ||

| 13 | Anaerosporobacter mobilis IMSNU 40011 | 6.5742 | 3.1274 | 2.3123 | 0.0013 |

| 8 | Clostridium tertium DSM 2485 | 7.1988 | 2.4887 | 2.6501 | 1.1177 |

| 10 | Klebsiella pneumoniae DSM 30104 | 5.9975 | 2.7745 | 22.3810 | 18.3039 |

TABLE 2.

Decreases in relative abundances of operational taxonomic units between responders and nonresponders observed in both SPF leghorn and broiler chickens

| OTU | Organism | Fold decrease in relative abundance |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leghorn chickens |

Broiler chickens |

||||

| Responders | Nonresponders | Responders | Nonresponders | ||

| 7 | Anaerostipes caccae L1-92 | 1.2534 | 19.0457 | 1.7858 | 4.4762 |

| 29 | Bifidobacterium pseudolongum JCM 5820 | 0.0783 | 0.2922 | 0.0555 | 0.1021 |

| 2 | Escherichia-Shigella flexneri X96963 | 5.7213 | 9.4335 | 12.7504 | 18.4703 |

| 14 | Lactobacillus fermentum-Lactobacillus mucosae CCUG 43179 | 0.0983 | 0.2154 | 1.1204 | 1.4731 |

| 9 | Lactobacillus reuteri L23507 | 0.1897 | 0.6602 | 3.0625 | 5.5524 |

Selection of probiotic strains.

We selected the only commercially available A. mobilis type strain, DSM 15930, previously isolated from forest soil and deposited in the DSMZ (38). To select a strain of L. reuteri, we performed an experiment to determine the strain with the highest ecological fitness among a list of poultry isolates. Lactobacillus-free SPF leghorn chickens were given an inoculum containing nine L. reuteri strains of poultry origin by gavage, as previously described (39). As shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, growth on L. reuteri isolation medium (LRIM) was increased from undetectable levels (<10 × 102 CFU) at day 0 to approximately 1 × 105 CFU 1 day after gavage. Cell numbers continued to increase, plateauing at approximately 1 × 107 CFU by day 4. These results indicate that L. reuteri was able to colonize Lactobacillus-free chickens and increase its population size. To determine the most competitive strain, a total of 94 colonies from 11 to 12 birds were randomly selected from growth plates obtained 5 days after gavage. Of these colonies, 85 generated a PCR product of the leuS gene and were all identified as L. reuteri strain CSF8 (37). This strain was therefore considered the most competitive strain and was selected for the vaccine experiments.

Coadministration of the N-glycan-based vaccine with probiotics decreases C. jejuni colonization.

We investigated if vaccination with the live E. coli vaccine in combination with A. mobilis DSM 15930 (38) or L. reuteri CSF8 has effects on vaccine efficacy, vaccine strain persistence, the immune response, growth performance, and the microbiome composition in broiler chickens challenged with C. jejuni 81-176.

Using the same 2-dose vaccination regime in a 35-day broiler chicken challenge model, the vaccine groups received 1 × 108 CFU of the live E. coli vaccine alone (Ec group) or 1 × 108 CFU of the live E. coli vaccine in combination with 1 × 108 CFU of either A. mobilis (EcAm group) or L. reuteri (EcLr group) on days 7 and 21. Birds were then challenged with 1 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni on day 28, and C. jejuni bacteria were enumerated on day 35 (Fig. 2A). All birds from the positive-control group (Cj group) (not vaccinated but challenged) were colonized with C. jejuni, with a statistical mean of 2.52 × 109 CFU/g cecal content (Fig. 2A). Administration of the vaccine alone resulted in a significant reduction in C. jejuni colonization after challenge. For groups that received the live vaccine in combination with either A. mobilis or L. reuteri, a further statistically significant reduction was observed compared to the vaccine-alone group. In all cases, a bimodal vaccine response was still observed. When we applied the same protocol but tested only the probiotic strains at doses of 1 × 108 CFU of A. mobilis (Am group) or 1 × 108 CFU of L. reuteri (Lr group) on days 7 and 21 followed by challenge with 1 × 106 CFU C. jejuni on day 28, we observed no effect on the colonization potential of C. jejuni on day 35 (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

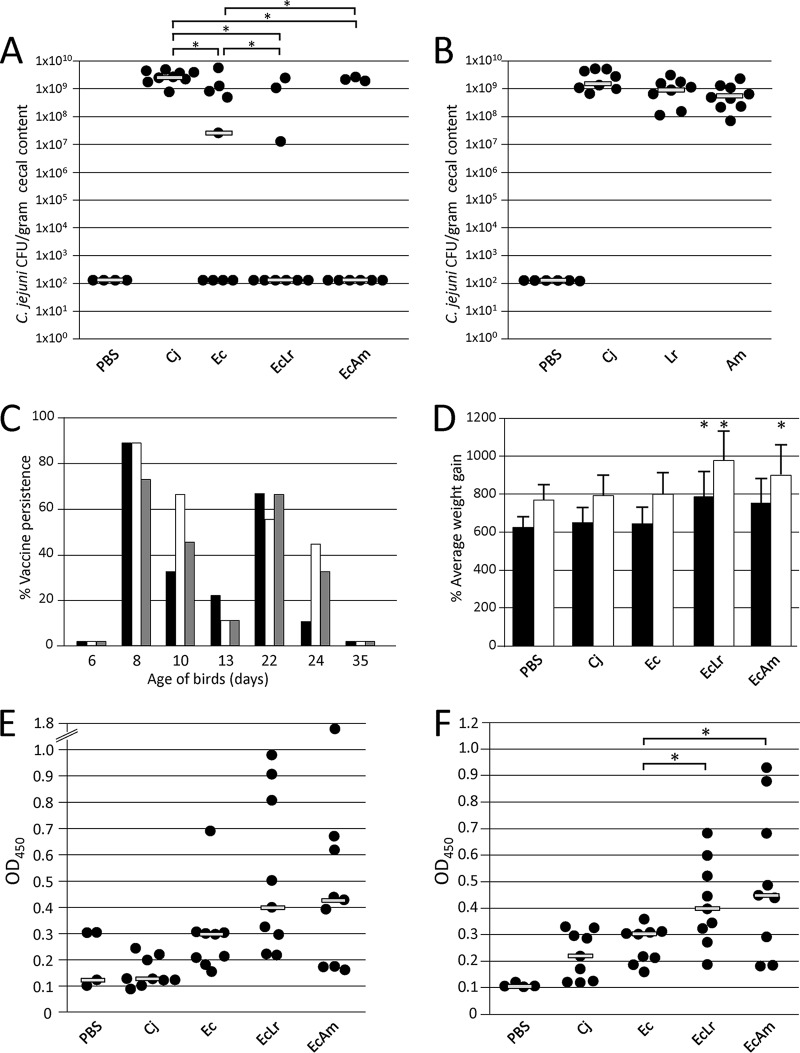

Vaccination and challenge experiments with broiler chickens. (A) Colonization levels of C. jejuni 81-176. Birds in the negative-control group (PBS) (n = 4) were nonvaccinated and nonchallenged; birds in the positive-control groups (Cj) (n = 9) were nonvaccinated but challenged with 1 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni 81-176 on day 28. Treatment groups (n = 9) included birds that were given 1 × 108 cells of the E. coli vaccine (Ec) or 1 × 108 cells of the E. coli vaccine in combination with 1 × 108 CFU of A. mobilis (EcAm) or 1 × 108 CFU L. reuteri CSF8 (EcLr) by oral gavage on days 7 and 21. (B) Additional control experiment demonstrating colonization levels of C. jejuni 81-176 in birds given 1 × 108 CFU of A. mobilis (Am) or 1 × 108 CFU of L. reuteri CSF8 alone (Lr) by oral gavage on days 7 and 21. (C) E. coli vaccine persistence in broiler chickens. E. coli fecal shedding was inspected by using cloacal swabs taken prior to the first and second vaccine feedings (days 6 and 13) as well as on the indicated days after vaccination for the following treatment groups: Ec (black bars), EcAm (white bars), and EcLr (gray bars). The PBS, Cj, Am, and Lr groups were all negative for the E. coli vaccine strain (not shown). Vaccine persistence is expressed as a percentage of positive birds within each group with detectable colonies on selective plates. (D) Weight gain of broilers. The average weight gain of the birds in the indicated groups during the vaccination and challenge experiments is shown. Black bars indicate weight gain (percent) over 23 days (day 8 to day 31); white bars show weight gain (percent) over 27 days (day 8 to day 35). Error bars represent the standard deviations within each group. Actual weights are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. (E and F) N-glycan-specific antibody responses. ELISA results comparing chicken sera from bleeds performed prior to C. jejuni challenge (day 28) (E) and at day 35 (F) are shown. Each point represents the antibody response measured as the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) for each individual chicken from the indicated groups. Gray bars represent the medians for each group. No N-glycan-specific antibodies were detected in sera from blood samples taken on day 1 and in sera of groups that received A. mobilis or L. reuteri alone (not shown). Statistically significant differences (if present) between groups with P values of <0.05 are indicated by an asterisk.

Coadministration of the vaccine with probiotics affects the persistence of the E. coli carrier.

We monitored the persistence of the vaccine strain by cloacal swabbing (Fig. 2C). On day 6, prior to the first vaccination, no E. coli cells were detected on selective plates. One day after vaccination (day 8), 89% of the birds were vaccine positive in the Ec and the EcAm groups, while 78% were positive in the EcLr group. On day 10, 33% of birds in the Ec group, 67% of birds in the EcAm group, and 44% of birds in the EcLr group were vaccine positive. On day 13, vaccine detection dropped to 22% (Ec group) and 11% (EcAm and EcLr groups). Similarly, 1 day after the second vaccination, 78% of birds (Ec and EcLr groups) and 67% of birds (EcAm group) were vaccine strain positive, while on day 24, only one bird in the Ec group was positive, and 44% and 33% of birds from the EcAm and EcLr groups showed vaccine persistence. We did not detect the E. coli carrier strain in any of the birds on day 35 or in the positive- and negative-control groups on any of the sample collection days. Although a faster decline in the persistence of the E. coli carrier was observed for all groups after the second vaccination, the increase in the number of birds that were still vaccine strain positive after the first and second vaccinations together with A. mobilis and after the second vaccination with L. reuteri compared to the Ec group indicates that A. mobilis and also, to some extent, L. reuteri might improve the persistence of the live E. coli vaccine strain in the chicken gut.

Coadministration of the vaccine with A. mobilis and L. reuteri positively affects N-glycan-specific immune responses.

N-glycan-specific immune responses in sera taken on day 27 prior to C. jejuni challenge (Fig. 2E) and again on day 35 (Fig. 2F) were determined. The average IgY levels measured in individual vaccinated birds on day 27 indicate that broiler chickens responded to the vaccination regime. N-glycan-specific IgY levels remained elevated on day 35 compared to the day 27 titers. Interestingly, statistically significantly elevated IgY levels were observed in birds that received A. mobilis and L. reuteri in combination with the live vaccine strain. Challenge with C. jejuni also resulted in low N-glycan-specific IgY levels in day 35 serum samples of the challenge controls (Fig. 2F), whereas no N-glycan-specific IgY antibodies were detected in serum samples taken on day 27 or in serum samples prepared from the negative-control group of birds (Fig. 2E). However, in all vaccinated groups, the highest individual titers did not correlate with birds that were protected against C. jejuni colonization, as observed previously (36).

Weight gain is increased in vaccinated broilers fed probiotics.

We were also interested in determining whether the vaccine strain or probiotics influence the growth performance of the animals. We observed a statistically significant increase in weight gain in birds that received the E. coli vaccine in combination with A. mobilis over 28 days and in combination with L. reuteri CSF8 over 23 days and 28 days (Fig. 2D; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material) compared to the other groups. For the other groups, no statistically significant differences in weight gain were observed.

Vaccine administration with and without probiotics does not significantly alter the gut microbiome of broiler chickens.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) analysis of Bray-Curtis distances, a measure of beta diversity, shows an overlap of challenged and vaccinated broiler chickens and negative controls (nonchallenged, nonvaccinated chickens), while microbial communities of the Cj (challenged) control group shifted (Fig. 3A). This indicates that the administration of the standard vaccine prevents the shift in the overall microbiota composition that is induced by C. jejuni challenge, as previously shown for SPF leghorn birds (36). Similarly, coadministration of the probiotics (Am and Lr groups) with the vaccine, although significantly different from the Cj group as measured by both Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and unweighted UniFrac distances, does not cause significant changes in the overall composition of the chicken gut microbiota compared to that of the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (not vaccinated, not challenged) group (Fig. 3B and C). Pathogen challenge resulted in a significant increase in the abundance of an operational taxonomic unit (OTU) that represents C. jejuni, while vaccination completely prevented this increase, confirming the efficacy of the vaccine (Fig. 3D). Changes in the bacteria of interest (Ec, Lr, and Am groups) caused by the vaccine treatments and between responders and nonresponders are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

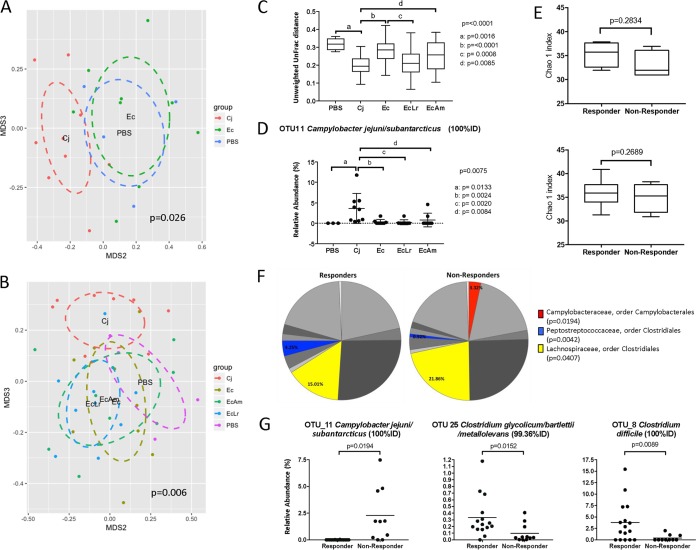

FIG 3.

Effect of the vaccine and the selected probiotics, L reuteri and A. mobilis, on the microbial communities in broiler ceca. (A) NMDS analysis based on the Bray-Curtis distance for the standard vaccine (Ec group) compared to controls for broilers shows that, as previously shown for leghorn birds (36), microbial communities from Ec broilers cluster with those from negative controls (PBS). (B and C) Likewise, analysis of beta diversity measured by both Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and unweighted UniFrac distances confirms that coadministration of the probiotics (A. mobilis and L. reuteri) with the vaccine, although significantly different from the Cj group, does not cause significant changes in the overall composition of the chicken gut microbiota compared to the PBS (not vaccinated, not challenged) group. (D) Administration of the E. coli vaccine with and without the probiotics significantly decreases the abundance of C. jejuni. (E, top) Analysis of alpha diversity indexes for the Ec group shows higher alpha diversity indexes in responders (n = 4) than in nonresponders (n = 5). (Bottom) This trend was also seen in the combined analysis of all responders (n = 16) and nonresponders (n = 11) for all treatments under investigation. (F) Analysis of families in the gut microbiome of responders and nonresponders from all treatment groups shows that members of the order Clostridiales (Peptostreptococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae) are affected by vaccine treatment. (G) Reductions in the abundances of C. jejuni occur in parallel with increases in the abundances of Clostridium species for the responder group; specifically, the abundances of OTU25 (Clostridium glycolicum-C. bartlettii-C. metallolevans) and OTU8 (Clostridium difficile) are higher in responders than in nonresponders. Statistics were analyzed by an Adonis test (A and B), one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons using Benjamini-Hochberg FDR correction (C and D), and Grubbs' test for the removal of outliers followed by an unpaired t test with Welch's correction (E to G). Lines represent means and standard deviations. For panels C and D, the top P value is the P value for overall ANOVA, and letters represent P values for individual comparisons, as specified by the bars.

Clostridiales species may play a role in the vaccine response.

To investigate the bimodal distribution among recipients of the N-glycan vaccine, we determined differences in microbial communities between responders and nonresponders in the vaccinated broilers. As previously observed in the leghorn chicken experiments (36) and our first vaccine study with broilers (Fig. 1C), analysis of the alpha diversity for the Ec group suggests higher alpha diversity in responders than in nonresponders (Fig. 3E, top). This effect was also seen in the combined analysis of all responders and nonresponders for all treatments under investigation (Fig. 3E, bottom). Besides the family Campylobacteraceae, statistically significant changes at this taxonomic level between the responder and nonresponder groups include decreases in the abundances of Peptostreptococcaceae and Eubacteriaceae (not shown in the chart due to an abundance of less than 1%) and increases in the abundances of Lachnospiraceae in the nonresponders (Fig. 3F). Analysis of OTUs showed that reductions in C. jejuni levels occur in parallel with increases in the abundances of Clostridium species for the responder group. Specifically, significant changes were observed for OTU25 (Clostridium glycolicum-C. bartlettii-C. metallolevans) and OTU8 (Clostridium difficile). Further analysis of OTUs for all vaccinated and control groups showed changes in several OTUs belonging to the order Clostridiales (Table 3). Interestingly, in most cases, the abundances of Clostridiales (OTUs 4, 20, 56, and 80) increased in the vaccinated groups independently of coadministration with probiotics.

TABLE 3.

Differences in the relative abundances of significant OTUs between controls and vaccinated broilers

| OTU | Organism(s) | % identity | Fold change in relative abundance for group |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | Cj | Ec | EcLr | EcAm | ||||

| OTU_11 | Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni-Campylobacter subantarcticus | 100 | 0.2144 | 3.6170 | 1.1009 | 0.7357 | 2.2292 | 0.0075 |

| OTU_13 | Proteus mirabilis | 100 | 0.0006 | 0.0943 | 4.0737 | 4.9539 | 0.6917 | <0.0001 |

| OTU_15 | Enterococcus casseliflavus-Enterococcus faecium-Enterococcus gallinarum-Enterococcus dispar-Enterococcus canintestini | 100 | 2.4172 | 0.9982 | 1.3140 | 1.4133 | 1.3226 | 0.0389 |

| OTU_16 | Enterococcus cecorum | 100 | 4.6469 | 2.8268 | 1.7185 | 1.8745 | 1.1014 | 0.0008 |

| OTU_20 | Ruminococcus sp.-Blautia sp. | 98.7 | 0.1562 | 0.5381 | 0.2919 | 0.7508 | 0.5464 | 0.0157 |

| OTU_21 | Clostridium paraputrificum | 100 | 0.5622 | 0.5025 | 0.0524 | 0.3606 | 0.0548 | 0.0410 |

| OTU_24 | Weissella paramesenteroides | 100 | 0.6453 | 0.1761 | 0.3811 | 0.2347 | 0.0584 | 0.0304 |

| OTU_33 | Escherichia coli-Shigella dysenteriae | 99.57 | 2.8263 | 1.8572 | 1.9689 | 2.1361 | 3.8945 | 0.0311 |

| OTU_34 | Corynebacterium variabile | 100 | 0.0409 | 0.0658 | 0.0259 | 0.0124 | 0.0071 | 0.0147 |

| OTU_37 | Corynebacterium sp. | 100 | 0.0138 | 0.0175 | 0.0092 | 0.0125 | 0.0039 | 0.0258 |

| OTU_4 | Blautia hydrogenotrophica-Ruminococcus hydrogenotrophicus | 94.64 | 4.9235 | 11.6432 | 11.5208 | 20.9710 | 16.1344 | 0.0064 |

| OTU_47 | Achromobacter spanius-Achromobacter xylosoxidans-Achromobacter piechaudii-Achromobacter marplatensis-Alcaligenes faecalis-Collimonas sp. | 100 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.0013 | 0.0011 | 0.0003 | 0.0462 |

| OTU_56 | Clostridium clostridioforme | 95.71 | 0.0006 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.0020 | 0.0139 |

| OTU_57 | Sanguibacter inulinus | 100 | 0.0040 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 |

| OTU_59 | Pseudomonas geniculata-Stenotrophomonas maltophilia-Xanthomonas sp.-Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum | 100 | 0.0017 | 0.0042 | 0.0060 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0076 |

| OTU_61 | Brevibacterium stationis-Corynebacterium sp. | 100 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.0022 | 0.0000 | 0.0268 |

| OTU_7 | Weissella cibaria-Weissella confusa | 100 | 8.5346 | 3.5279 | 3.2851 | 2.8729 | 3.2314 | 0.0411 |

| OTU_80 | Clostridium aldenense | 98.07 | 0.7110 | 0.6345 | 3.1051 | 4.0495 | 4.3984 | 0.0040 |

Vaccination of chickens does not select for a C. jejuni “supercolonizer.”

One possibility for the nonresponder effect is selection for a supercolonizer or vaccine-resistant variant due to on/off switches in one or a combination of phase-variable genes. The challenge strain, C. jejuni 81-176, has 19 phase-variable loci containing poly(G) or poly(C) tracts; the average expression states for these genes were investigated by analyzing 30 single colonies of the challenge inoculum and 30 colonies from individual vaccinated/nonresponder birds and nonvaccinated birds. Hierarchical clustering of average expression states indicated that while there was bird-to-bird variation in expression states, there was no obvious selection for a specific expression state in nonresponders versus control birds (Fig. 4). Similarly, there was no difference between these groups for combinatorial phasotypes of the five most variable genes (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

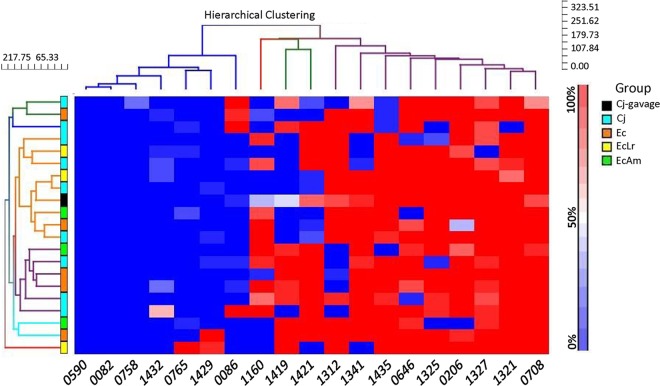

FIG 4.

Hierarchical clustering analysis of phase-variable expression states in C. jejuni 81-176 isolates from control and nonresponder broiler chickens. The expression states of each gene (CJJ81176 [gene numbers as indicated]) were determined by analysis of the poly(G) repeat tracts of 28 to 30 colonies per cecal sample and utilized for calculation of the fraction of colonies in an “on” state (color-coded as indicated by the sliding bar on the right). Hierarchical clustering was performed using the percent “on” states for 19 genes and 21 samples. The phylogenetic trees are shown for the genes (top) and samples (left). There are 7 chicken samples that cluster reasonably closely to the gavage samples (orange lines in the tree). These samples are a mix of control (n = 3) and vaccine (n = 4) samples. The other samples are dispersed, with no obvious clustering of control or vaccine samples. This suggests that no specific pattern of phase-variable gene expression is associated with the persisters in the vaccine group and that variation in the vaccinated birds is not different from that in the controls. The hierarchical clustering analysis for the genes indicates three clusters. On the left are the genes that are off (low percent “on”) in most samples (red), and on the right are the genes that are on (high percent “on”) in most samples. In the middle are genes that show a more variable pattern across the samples. Within the latter set are 5 genes in 81-176 (homologs in C. jejuni NCTC11168 are in parentheses): CJJ81176_0086 (no homolog), CJJ81176_1160 (Cj1143), CJJ81176_1312 (Cj1295), CJJ81176_1419 (Cj1420c), and CJJ81176_1421 (Cj1422c) (GenBank accession number CP000538.1).

A metabolite identified by NMR is a potential biomarker of C. jejuni clearance.

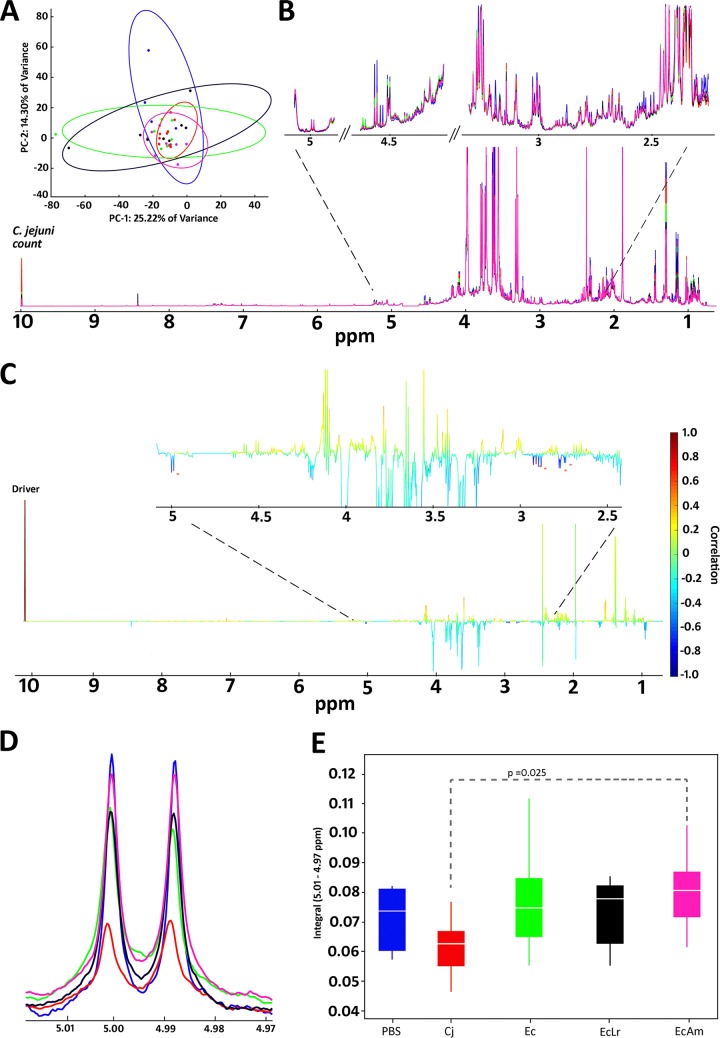

Next, we aimed to identify small-molecule metabolites in the cecal contents that might be associated with the responder-nonresponder effect. Multivariate principal-component analysis (PCA) and partial least-squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) results for 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data were not useful in discriminating individual groups (Fig. 5A and Table S5). Therefore, we used statistical total correlation spectroscopy (STOCSY) to statistically correlate the bacterial load (i.e., C. jejuni colonization counts) in each sample with the 1H NMR data (Fig. 5B). This yielded spectral features at 5.0, 2.9, and 2.7 ppm that were negatively correlated (−0.60, −0.68, and −0.70, respectively) with the collected C. jejuni counts (Fig. 5C and D). STOCSY using the resonance at 5.0 ppm as a driver peak also yielded strong positive correlations (0.91 and 0.82) with resonances at 2.9 and 2.7 ppm and a negative correlation (−0.59) with the bacterial load (Fig. S3A), suggesting that the features at 5.0, 2.9, and 2.7 ppm are in the same molecule (40). Two-dimensional (2D) NMR experiments (heteronuclear single quantum coherence total correlation spectroscopy [HSQC-TOCSY] and TOCSY) confirmed the STOCSY results showing that the three statistically correlated features are in the same molecule (Fig. S3B). TOCSY also confirmed the presence of a previously unobserved peak at 3.5 ppm belonging to the same molecule. The feature at 5.0 ppm was selected for further statistical analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results for the five groups showed significant differences between the nonvaccinated (Cj) group and the vaccinated and A. mobilis-treated (EcAm) group (P = 0.025) (Fig. 5E). In addition to the features described above that were negatively correlated with the bacterial load, we also identified 20 metabolites using the COLMAR (Complex Mixture Analysis by NMR) and Assure NMR databases (Table S6). The confidence scale, which is described in the supplemental material, was used to assign compound identifications (41).

FIG 5.

NMR metabolomics. (A) PCA plot of aligned, normalized, and scaled data showing high overlap, large intragroup variability, and little separation across principal component 1 (PC1) and PC2. (B) Spectral overlay of averaged spectra within each group indicating a metabolite-rich spectrum with an expanded region of interest between 2.5 and 5 ppm. The C. jejuni posttreatment count has been integrated into the spectra at 10 ppm. (C) STOCSY output displaying correlation as color and covariance as peak height. Asterisks denote negative correlations with the C. jejuni count Driver peak (correlations, −0.60, −0.68, −0.68, −0.70, and −0.60, respectively, from left to right). (D) Expansion of 5 ppm denoting the different study groups as labeled in panel E. (E) Integral distribution of the 5-ppm feature and ANOVA indicating a significant difference between the nonvaccinated but challenged Cj group and the vaccinated and challenged EcAm group (P = 0.025). There were no significant differences between the other groups.

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that the C. jejuni N-glycan is an effective antigen in various vaccine formulations, including glycoprotein conjugates, E. coli surface expression carriers, and outer membrane vesicles (36, 42). To date, the live E. coli vaccine comprised of the N-glycan attached to the LOS core demonstrated the greatest success in significantly reducing C. jejuni colonization in leghorn chicken challenge studies (36). Here, we tested the live E. coli vaccine in broiler chickens and demonstrated that even with a C. jejuni challenge dose of 1 × 106 CFU (compared to the dose of 1 × 102 CFU previously used for leghorn chickens), broiler chickens similarly showed up to a 10-log drop in C. jejuni colonization. However, in both experiments, we noticed a bimodal response, with some birds showing very little protection after vaccination.

A consistent trend toward a higher number of taxa was observed in the vaccine responders. We therefore speculated that certain resident microbes might help to reduce C. jejuni persisters through colonization competition and nutrient depletion. The diversity in responders could potentially increase competition in the gut and create a more diverse microbial community that is better able to exploit available resources, limiting any sustenance for an invading population and leading to resistance against new invaders and ultimately microbe elimination (43). From our microbiome analysis of vaccine responders versus nonresponders in the broiler chicken experiment and our previous leghorn chicken experiment (reanalysis of data from reference 36), we observed increased proportions of Clostridiales and particularly A. mobilis. Interestingly, the A. mobilis DSM 15930 strain that we obtained displayed the greatest metabolic capacity compared to its nearest phylogenetic relatives within cluster XIVa of the Clostridium subphylum (38). Therefore, A. mobilis was used as a probiotic and was administered jointly with the vaccine in subsequent broiler chicken challenge experiments.

Previous reports also described an antagonistic relationship between C. jejuni and Lactobacillus species (44, 45), including L. reuteri (46). Thus, L. reuteri probiotic strain CSF8 was also selected by using an experimental design validated for comparison of the ecological competitiveness of L. reuteri strains in chickens in vivo (39). The fact that L. reuteri CSF8 outcompeted all other L. reuteri strains that were also of poultry origin suggests that this strain has evolved specific adaptations to be competitive and metabolically active under the ecological conditions expected in the chicken intestine, and this strain was therefore selected as another probiotic strain for use in the vaccine experiment.

A higher proportion of protected birds was observed after coadministration of the vaccine with either A. mobilis or L. reuteri than with administration of the vaccine alone. Both probiotics increased bird body weights, E. coli vaccine persistence, and the IgY response to the C. jejuni N-glycan antigen compared to the vaccine-alone group. The increased levels of antibody production against the C. jejuni glycoconjugate antigen were unexpected and may be attributed to the fact that the coadministration of the probiotic with the E. coli vaccine resulted in a prolonged persistence of the live vaccine in these birds, helping boost the chicken immune system once it was fully mature (47). This would be consistent with data from previous reports describing the influence of the gut microbiome in modulating the host immune system and its impact on health and disease (48–50). Alternatively, A. mobilis and also, to some extent, L. reuteri CSF8 may have direct immunostimulatory properties, acting as vaccine adjuvants to enhance the antigen-specific immune response, an effect that was described previously for various vaccines in combination with Lactobacillus species in animal and human trials (51). Similar studies demonstrated that C. jejuni infection in combination with the administration of Enterococcus faecium probiotic strain AL41 resulted in the upregulation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MD2, which conferred responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and to C. jejuni (52, 53), enhanced migration inhibition factor (MIF) and beta interferon (IFN-β) production, and prolonged activation of TLR21 compared to C. jejuni alone (53, 54). In future studies, we also plan to examine the expressions levels of immunoglobulin and Toll-like receptors in bird serum samples by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR).

The observation that A. mobilis has no antibiotic resistances would indeed make it a good probiotic. However, A. mobilis could not be detected in cecal swabs or by PCR that was optimized for the specific amplification of the 16S RNA gene (data not shown), indicating that this forest soil isolate may colonize chickens only transiently and is not well adapted to survive in the chicken gastrointestinal tract. We are currently attempting to retrieve native chicken isolates, similar to what we have done for the L. reuteri strains, for comparative studies.

Although we could not confirm that A. mobilis itself differentiates responders and nonresponders, reductions in C. jejuni levels in the responder group occurred in parallel with higher proportions of many closely related taxa (all Clostridiales). Since A. mobilis is a member of the Clostridium cluster XIVa group (38), initial, short-term colonization might pave the way for other members of the community, i.e., Clostridiaceae that have similar functional niches and can replace one another (functional redundancy). Among the Clostridium cluster I bacteria, we found increased levels of OTU8 (Clostridium difficile). Although regarded as an opportunistic pathogen in humans, C. difficile is ubiquitous in nature and commonly found in food animals, including cattle and chickens (55). Given the fact that members of Clostridiaceae cluster I constitute the most abundant family in the gut microbiome of leghorn chickens, together with the finding that the abundances of multiple Clostridium species are significantly increased in responders, the observed increase in the abundance of OTU8 is not surprising. It is important to note, however, that the administration of the vaccine did not alter the levels of C. difficile in the gut, since it is notably absent from the list of OTUs that were different between the control and vaccinated groups (Table 3). However, the overall increase in the abundance of Clostridiales in responders suggests that this order may have an influence on C. jejuni colonization or vaccine efficacy.

Similarly, previous studies demonstrated that feeding of L. reuteri KUB-AC5 in the early posthatching period leads to an enrichment of potentially beneficial lactobacilli, thereby delaying the development of the ileum microbiota and suppressing proteobacteria, including campylobacters (46). For another Lactobacillus species, L. gasseri SBT2055, it was suggested that this strain reduces C. jejuni colonization in chickens by competitive exclusion (44, 45). In the current study, coadministration of the robust colonizing isolate L. reuteri CSF8 with the E. coli vaccine also improved vaccine efficacy. This finding is consistent with data from previous reports describing the antagonistic relationship between C. jejuni and Lactobacillus species but contradictory to our observations that L. reuteri proportions were decreased in both leghorn and broiler chicken vaccine responders (Table 2).

Probiotic bacteria have also been reported to behave equivalently to or better than growth-enhancing antibiotics in chickens (56–58), with weight gains that were significantly higher in experimental birds than in controls (59–61). In addition, the metabolic capabilities of specific probiotics or the induced changes in the microbial communities can alter the composition of the intestinal metabolome. It was recently demonstrated that short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and organic acids such as lactate that are generated by the chicken microbiota influence the ability of C. jejuni to colonize different regions of the avian gastrointestinal tract (62). Specific probiotics with extensive carbohydrate fermentation capabilities, such as A. mobilis (38) and other Clostridium cluster IV and XIVa bacteria known to be important for SCFA metabolism (63, 64), can change the intestinal metabolite composition to prevent campylobacter colonization (65, 66).

Although the multivariate analyses in our metabolomics approach did not identify separating features in the PCA/PLS space, suggesting that the metabolome was relatively uniform between groups (see Table S5 in the supplemental material), the statistical correlation of a phenotypic response with the NMR data enabled the successful identification of a potential biomarker at 5.0 ppm that is negatively correlated with C. jejuni colonization counts. This feature and others that are statistically correlated with it significantly differ between the nonvaccinated group and the vaccinated group treated with A. mobilis, indicating that the clearance of C. jejuni and the increase in the level of the isolated biomarker are connected. The NMR features at 5.0, 2.9, and 2.7 ppm are correlated with the same compound, but due to their low relative abundance and absence in available databases, we have not yet identified this compound. Further analyses are required to identify the chemical structure of the 5.0-ppm feature, which will include an HPLC-SPE (high-performance liquid chromatography–solid-phase extraction) approach that can physically isolate and concentrate these features from the complex biological matrix and additional NMR and mass spectrometry experiments to produce complementary data to elucidate its structure. However, it is tempting to predict that this compound could be a metabolic end product produced by a member of the Clostridiales.

It is known that phase variation of surface structures such as LOS, CPS, and flagella can influence C. jejuni colonization potential and phage predation in chickens (67–70). Passage through chickens can also promote phase variation in certain contingency genes (71, 72), including Cj0170, which is involved in regulating motility, and Cj0045, which is associated with colonization and disease in mice (73). Here, we compared average phase-variable expression states for 19 loci by analysis of 30 colonies isolated from each C. jejuni-positive bird versus 30 colonies obtained from the input culture. Our results indicate that the differences in vaccine protection are not due to phase-variable changes in the C. jejuni genome due to mutations in poly(G)/poly(C) tracts that would select for a robust colonizing strain. These results are consistent with data from previous reports demonstrating that the high rates of C. jejuni mutability in contingency loci are not associated with a preferred population for chicken colonization (74). We have shown previously that the N-glycan is not phase variable and hence cannot be turned off by this mechanism as a strategy for C. jejuni to evade antibodies elicited by immunization or natural infection (36). In addition, our previous studies (36) and current studies (results not shown) examining C. jejuni persisters demonstrated no changes in N-glycan expression.

Many research groups have attempted to reduce the numbers of C. jejuni bacteria in poultry in order to reduce human foodborne diarrheal disease and the subsequent sequelae associated with this ubiquitous microbe, which was recently listed by the World Health Organization as a high-priority pathogen (75). However, it has proven to be a formidable challenge to eliminate this natural commensal from its host during the period prior to slaughter, when the organism is immunologically silent (76). We have demonstrated that the E. coli-based C. jejuni N-glycan vaccine is equally effective in broiler chickens, reducing C. jejuni colonization to undetectable levels in most birds. However, there is a subpopulation of birds that are unresponsive to vaccination. These nonresponders do not possess a supercolonizing mutant but rather show decreased levels of Clostridiales in their gastrointestinal tracts. We demonstrate that the coadministration of probiotic strains with the vaccine improves vaccine efficacy, the antibody response, and weight gain. Increased efforts in selecting robust colonizing strains from broiler birds and/or adding nutritional supplements to the vaccination regime will help to improve vaccine efficacy and bring us one step closer to reducing campylobacteriosis worldwide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

C. jejuni was grown at 37°C for 18 to 24 h under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2) on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar or Karmali agar with Campylobacter selective supplement (Oxoid). The E. coli wzy::kan vaccine strain expressing the C. jejuni protein glycosylation locus from plasmid pACYC184/pgl (36, 77) was grown in super optimal broth (SOB), 2× YT, or Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C with shaking. For the enumeration of vaccine strain bacteria, cloacal swabs were streaked onto membrane fecal coliform (m-FC) agar with 1% rosolic acid. The antibiotics chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml) and kanamycin (25 μg/ml) were added when appropriate. Anaerosporobacter mobilis (DSM 15930 [type strain]) (38) was grown on thioglycolate medium (Sigma) agar or in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with 0.5 g/liter sodium thioglycolate under anaerobic conditions. Lactobacillus reuteri CSF8 (37) was grown on LRIM agar.

The identity of A. mobilis was verified by amplifying the 16S rRNA gene. Primers were selected based on the available partial sequence (GenBank accession number NR_042953.1) of A. mobilis strain IMSNU 40011 by using Primer-BLAST (78). A specific product of 601 nucleotides (nt) was obtained with forward primer 5-ATTCGATTCTCAGGTGCCGA-3 and reverse primer 5-ACTGACTTCGGGCATTACC-3 only with chromosomal DNA of A. mobilis. PCRs were performed with Vent polymerase (NEB) under standard conditions, with an annealing temperature of 52°C.

Chicken immunization and challenge and Campylobacter colonization.

Commercial broiler birds (Ross 308; Avigen) were obtained on the day of hatching from Lilydale and provided by the Poultry Research Facility, University of Alberta. Birds were randomly tagged, grouped, housed in cages, and given water and feed ad libitum. For each experiment, a subset of birds (10%) was tested via cloacal swabbing on Karmali agar to confirm that the flock is Campylobacter negative. All experiments were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alberta. Chickens were vaccinated on days 7 and 21 by oral gavage with 300 μl PBS containing 1 × 108 CFU of the E. coli wzy::kan(pACYC184/pgl) strain. Preparation of the live E. coli vaccine was described previously (36). On day 28, birds were challenged with 300 μl PBS containing 1 × 106 CFU of C. jejuni 81-176 as described previously (36). The negative-control group received PBS only on days 7, 21, and 28, and the positive-control (colonization) group (Cj group) received PBS only on days 7 and 21 and was challenged with C. jejuni on day 28. On day 35, all birds were euthanized, and serial dilutions of the cecal contents (in PBS) were plated onto Karmali agar. Colonization for each bird was calculated based on the CFU observed for selected dilutions, and C. jejuni colonization was plotted as CFU/g of cecal content for each bird. The dilution and plating procedures resulted in a detection limit of 2 × 102 CFU C. jejuni/g of cecal content. The second cecum was collected and stored at −80°C until further analysis (i.e., 16S sequencing and microbiome analysis) was performed, as described below.

Sampling and sample analysis. (i) Blood serum collection.

Blood was collected from 10% of the birds on day 1 and from all birds on day 27 (1 day prior to challenge) and on day 35. Sera were collected after keeping the blood at room temperature (RT) until clotting was observed. Following centrifugation for 5 min at 8,000 rpm, the sera were collected and stored at −20°C.

(ii) Immune response/ELISA.

Preparation of the capture antigen (C. jejuni N-glycan cross-linked to bovine serum albumin [BSA]) was described previously (36). Levels of serum antibodies against the N-glycan were determined as described previously (36). Briefly, 500 ng of the capture antigen in PBS was immobilized on 96-well MaxiSorp plates for 18 h at 4°C. Plates were blocked for 1 h at RT with PBS-Tween (PBS-T) plus 5% skim milk, washed three times with PBS-T, and incubated for 1 h at RT with sera, individually diluted 1:10 in PBS-T plus 1% skim milk. After three washes with PBS-T, IgY-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:200 in PBS-T plus 1% skim milk) was used to detect N-glycan-specific antibodies. After three final washes with PBS-T, the plates were developed with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After the reaction was stopped with 3 M H2SO4, the optical density at 450 nm was determined with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plate reader. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate.

(iii) Weight determination.

The live weight of each individual bird was determined on days 8, 31, and 35. Weight gain was calculated as the average increase in the percent body weight over time spans of 23 and/or 27 days.

(iv) Vaccine persistence.

Cloacal swabs from all birds were collected on days 0, 6, 8, 10, 13, 22, 24, and 35. Swabs were either stored in sterile PBS plus 10% glycerol at −80°C or directly plated on m-FC agar with 1% rosolic acid and supplemented with antibiotics appropriate for vaccine strain selection. Birds were found to be vaccine strain positive when >10 Cmr Kanr (coliform) colonies were present after incubation for 24 h at 37°C and when at least 5 colonies were found to be positive for the expression of the vaccine compound as determined by Western blotting (performed as described previously [36]) (data not shown) of proteinase K-digested whole-cell lysates of cells obtained after inoculation of single colonies from m-FC agar in 2× YT and growth for 3 to 4 h at 37°C.

Chicken microbiome studies: microbiome data analysis.

Illumina 16S rRNA sequence reads were processed and analyzed as previously described (36), with the following modifications. Reads were trimmed to 290 bp by using FASTX-Toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/), and paired-end reads were merged by using the merge-illumina-pairs application (https://github.com/merenlab/illumina-utils) with the following quality parameters: a P value of 0.03, enforce-Q30-check, no ambiguous nucleotides, and perfect matching to primers. An average of 79,465 merged reads per sample was obtained. Files were subsampled to 50,000 reads by using Mothur v.1.32.0 to standardize the depth of analysis across samples. Merged sequences between 440 and 470 bp long were kept for analysis. USEARCH v.7.0.1001 was used to remove potential chimeras and to cluster the reads into OTUs, using a 98% similarity cutoff. Taxonomic classification at the phylum, family, and genus levels was performed by using the Ribosomal Database Project Multiclassifier v.1.1 tool. Taxonomic classification for the OTUs was done by selecting the highest percent identity for the OTUs of representative sequences (selected by the UPARSE-OTU algorithm based on read abundance) when blasted against the Greengenes database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/) and confirmed by using NCBI BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch) and RDP SeqMatch (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/seqmatch/seqmatch_intro.jsp). Percent proportions were calculated based on the total number of reads per sample. Diversity metrics were calculated by using MacQIIME version 1.8.0. An Adonis permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) on the Bray-Curtis distance was performed by using R (https://www.r-project.org/). Grubbs' test for the removal of outliers followed by one-way ANOVA with Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction or an unpaired t test with Welch's correction was performed by using GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) to compare bacterial compositions and differences in alpha diversity values between the treatments or between responders and nonresponders, respectively.

Analysis of the poly(G) tracts of C. jejuni strain 81-176.

Oligonucleotide primers were designed to span the 19 poly(G)/poly(C) tracts of C. jejuni strain 81-176 containing eight or more G or C nucleotides (Table 4). One primer of each pair was labeled with a fluorescent tag (6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM], VIC, or NED). Oligonucleotides were combined into four mixes capable of amplifying 4 to 6 loci (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). The PV genes of individual colonies of strain 81-176 were analyzed by using this 19-locus CJ81176 PV analysis, as described previously (79) for the 28-locus CJ11168 PV analysis. Briefly, lysates of colonies were subjected to multiplex PCR with the four primer mixes, and all products were mixed and subjected to GeneScan analysis using a GS600LIZ DNA ladder on an ABI3100 autosequencer. Output data files were analyzed with PeakScanner and PSAnalyse to determine PCR fragment sizes followed by the conversion of these sizes into tract lengths and expression states in comparison to a control sample with known repeat tract lengths (as determined by dideoxy sequencing of PCR products spanning each repeat tract). Percent expression states were determined from multiple colonies for each gene and analyzed by using Partek.

TABLE 4.

Primers for 81-176 poly(G)-containing genes

| Gene | NCTC11168 homologa | Primer | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| CJJ81176_0082 | Cj0044c | 81176-0082-fwd | GGTTTTACACTAGAACACAGAAG |

| 81176-0082-fwd-FAM | FAM-GGTTTTACACTAGAACACAGAAG | ||

| 81176-0082-rev | CCATACACGAAGAACTTGTTAGCAA | ||

| CJJ81176_0086 | NA | 81176-0086-fwd | GCACAAGCTACAAATTTAGAAGTG |

| 81176-0086-fwd-FAM | FAM-GCACAAGCTACAAATTTAGAAGTG | ||

| 81176-0086-rev | AAGTAGAAGCATTAGGCGTGGAT | ||

| CJJ81176_0206 | Cj0171 | 81176-0206-fwd | TGTTGTGGAAATGGAGTGCATTC |

| 81176-0206-fwd-NED | TGGTTGTGGAAATGGAGTGCATTC | ||

| 81176-0206-rev | AATAGCTCCTTCATTGCATAGTTC | ||

| CJJ81176_0590 | Cj0565 | 81176-0590-fwd | GCTATAGTGTTGATGTGTAGTTTGT |

| 81176-0590-fwd-FAM | FAM-GCTATAGTGTTGATGTGTAGTTTGT | ||

| 81176-0590-rev | CCTTTATCAATTTCTATTCTTAGAC | ||

| CJJ81176_0646 | Cj0617 | 81176-0646-fwd | TGGTATAATGCAAGCTATGG |

| 81176-0646-fwd-VIC | TGGTATAATGCAAGCTATGG | ||

| 81176-0646-rev | AAATCAATACTCCAAGGAGC | ||

| CJJ81176_0708 | Cj0685 | 81176-0708-fwd | GATAGCGAATATAACCTCTAAATTC |

| 81176-0708-fwd-FAM | FAM-GATAGCGAATATAACCTCTAAATTC | ||

| 81176-0708-rev | GAAGAAATCCGCCAATCAAAGGCC | ||

| CJJ81176_0758 | Cj0735 | 81176-0758-fwd | GCAAACCAAGCATAGGGGATTGTGG |

| 81176-0758-fwd-FAM | FAM-GCAAACCAAGCATAGGGGATTGTGG | ||

| 81176-0758-rev | TTCACCATCAAAAGCTACAGATCCTG | ||

| CJJ81176_0765 | NA | 81176-0765-fwd | TGCAAGAGCTGTTCATCGGTTTAAAC |

| 81176-0765-fwd-NED | TGCAAGAGCTGTTCATCGGTTTAAAC | ||

| 81176-0765-rev | CTTAAAAGGGGATTAAATAAAGGAT | ||

| CJJ81176_1160 | Cj1143 | 81176-1160-fwd | CGATGCCAAGAAGCTTTATAAGAGTT |

| 81176-1160-fwd-FAM | FAM-CGATGCCAAGAAGCTTTATAAGAGTT | ||

| 81176-1160-rev | GCTTGTAGTATTTTCACTCCTTGAGAT | ||

| CJJ81176_1312 | Cj1295 | 81176-1312-fwd | TTCCTATCCCTAGGAGTATC |

| 81176-1312-fwd-NED | TTCCTATCCCTAGGAGTATC | ||

| 81176-1312-rev | ATAGGCTTCTTTAGCGTTCC | ||

| CJJ81176_1321 | Cj1305c | 81176-1321-27-fwd | CAACTTTTATCCCACCTAATGGAG |

| 81176-1321-27-fwd-VIC | CAACTTTTATCCCACCTAATGGAG | ||

| 81176-1321-rev | GTGGAAAATCTTCATAATATTCACTG | ||

| CJJ81176_1325 | NA | 81176-1325-fwd | GCTTGATGATAATTTTACCGCCTTAAG |

| 81176-1325-rev | CAATCTAGCCTTAGGCACTCCGATT | ||

| CJJ81176_1327 | NA | 81176-1325-fwd-FAM | FAM-GCTTGATGATAATTTTACCGCCTTAAG |

| 81176-1327-rev | TCTCAATAACGGCAAAACAGTTCCC | ||

| CJJ81176_1341 | Cj1342 | 81176-1341-fwd | GGTAATCGTCCTCAAACAGG |

| 81176-1341-fwd-FAM | FAM-GGTAATCGTCCTCAAACAGG | ||

| 81176-1341-rev | GCCAAATGCGCTAAATATCC | ||

| CJJ81176_1419 | Cj1420c | 81176-1419-fwd | GCTAGTTCTTTCCATTGGAC |

| 81176-1419-fwd-FAM | FAM-GCTAGTTCTTTCCATTGGAC | ||

| 81176-1419-rev | TGCCACTGCTTACACGAGCAAG | ||

| CJJ81176_1421 | Cj1422c | 81176-1421-35-rev | TTGAGCTGAGGAAAGATTTGTATAG |

| 81176-1421-fwd | TATTGGTGTGCCTGAGGATTATTAT | ||

| 81176-1421-fwd-VIC | TATTGGTGTGCCTGAGGATTATTAT | ||

| CJJ81176_1429 | Cj1429c | 81176-1429-fwd | CTCCTATTCTTTCAGAACGTGATAT |

| 81176-1429-fwd-FAM | FAM-CTCCTATTCTTTCAGAACGTGATAT | ||

| 81176-1429-rev | CTATGCTAGCATCATATTCAATTACC | ||

| CJJ81176_1432 | Cj1138 | 81176-1432-fwd | CTAGGACAGGCTTTGATTATAAATTC |

| 81176-1432-fwd-VIC | CTAGGACAGGCTTTGATTATAAATTC | ||

| 81176-1432-rev | CACCATCATCTCTAACAGATATAAAT | ||

| CJJ81176_1435 | NA | 81176-1435-fwd | ATCTTAATACCTGATTTTATCAAAAC |

| 81176-1435-fwd-NED | ATCTTAATACCTGATTTTATCAAAAC |

NA, not applicable (no homolog in NCTC11168).

In vivo L. reuteri selection.

Nine L. reuteri strains were used for the in vivo probiotic selection experiment (Table S1). Strains were originally isolated from either chickens or turkeys and belonged to a phylogenetic lineage specific to poultry (39, 80). Each of the strains carried a distinct leuS allele to allow differentiation via colony typing (Table S1). In vivo competition experiments were conducted according to methods described previously by Duar et al. (39), with some modifications. Briefly, individual strains were grown in MRS medium (Difco) supplemented with 0.5% fructose and 1% maltose at 37°C for 16 h. Prior to gavage, cells from individual cultures were harvested by centrifugation (3,000 × g for 10 min), washed twice with sterile PBS (pH 7.0), and mixed in equal numbers in the same buffer to generate the inocula. Lactobacillus-free SPF leghorn chickens, reared as described previously (39), received a 300-μl PBS suspension containing 1 × 106 cells of each L. reuteri strain by gavage. Cloacal swabs were taken from the chickens before gavage at day 0 and for 5 days after gavage and cultured by dilution plating on LRIM (39). To identify the most competitive strain, 11 to 12 random colonies grown from each cloacal swab collected at day 5 were selected from the LRIM plates and typed by DNA sequencing of the leuS gene. Strain competiveness was determined based the proportions of colonies corresponding to each strain, as previously outlined (39).

NMR metabolomics. (i) Sample preparation.

Each study sample was given a unique identifier and subsequently randomized. We added five Red Cross human plasma samples as external controls and two empty vials as extraction blanks. All samples were thawed at room temperature, and their individual masses were recorded. Samples were prepared by adding 1 ml of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-grade water (Chromasol) per gram of cecal material, obtaining a 1:1 (wt/vol) ratio. The samples were then vortex mixed for 20 min and centrifuged in a cold AccuSpin 3R centrifuge for 30 min at 3,500 × g at 4°C. The supernatants were collected, and 1-ml aliquots were centrifuged for 30 min at 22,000 × g in a high-speed microcentrifuge inside a cold 4°C room.

NMR samples were prepared by mixing 675 μl of the final cecal extract supernatant and 75 μl of sodium phosphate buffer (1 M) in D2O, with DSS (4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid) as an internal standard (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), which provides a final pH of 7.4 and a final DSS concentration of 0.33 mM. A total of 580 μl of each NMR sample was transferred to a 5-mm SampleJet NMR tube. The remaining 170 μl was pooled, and five internal controls were created and randomized with the study samples, the external controls, and the extraction blanks. Three additional NMR tubes containing sodium phosphate buffer were inserted at the beginning, middle, and end of the NMR run as buffer blank quality controls.

(ii) NMR data collection.

NMR experiments were performed at 300K by using a 600-MHz Bruker Advance III HD spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryoprobe and a controlled-temperature automatic SampleJet sample changer. One-dimensional (1D) 1H NMR spectra for each sample were acquired by using an optimized PROJECT (periodic refocusing of J evolution by coherence transfer) pulse sequence (81, 82).

Immediately after each 1H NMR experiment, data from a J-res (homonuclear J-resolved spectroscopy) experiment were also collected. Data from standard 2D 1H-13C HSQC, 1H-13C HSQC-TOCSY, and 1H-1H TOCSY experiments were collected from pooled samples and individual samples of interest.

(iii) Data analysis.

Each spectrum was referenced to the DSS signal at 0.0 ppm. 1D 1H NMR spectra were phased and baseline corrected by using TopSpin 3.5pl7 (BrukerBiospin), and 2D spectra were processed by using NMRPipe software (83). 1H NMR data were imported into Matlab R2016a. The water region from 4.66 to 4.88 ppm and the spectrum extremities (>10.00 and <−0.30 ppm) were removed prior to data analysis. Spectral features were aligned by using peak alignment by Fourier transform (PAFFT) (84) to obtain consistent overlaps across all samples. Data were then normalized by using probabilistic quotient normalization (PQN) (85) to minimize the effect of total sample variation. STOCSY analysis (86) allowed the visualization of correlating features across a whole spectrum. Significant differences of features across the different study groups were tested by ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer post hoc all-means comparison procedure. Furthermore, the data were scaled by using nonthreshold logarithmic transformation in order to carry out multivariate analyses, PCA and PLS-DA, to identify sources of variation that could separate the data across the different study groups. Putative metabolite identification was carried out by using the database-matching platforms COLMAR (87) and Assure NMR (BrukerBiospin).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cory Wenzel for help with chicken studies; Brandi Davis and Yee Ying Lock for preparation of samples for 16S rRNA sequencing; and the Animal Facility Staff at the University of Alberta for technical assistance, advice, and excellent collaboration.

This work has been supported by ALMA grant 2016R037R. L.L.-S. was supported by an REF Impact award from the University of Leicester. A.S.E. and G.J.G. were partially supported by the Georgia Research Alliance. J.W. is a CAIP Chair in Nutrition, Microbes, and Gastrointestinal Health. C.M.S. is an Alberta Innovates Strategic Chair in bacterial glycomics.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01523-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaakoush NO, Castano-Rodriguez N, Mitchell HM, Man SM. 2015. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 28:687–720. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore JE, Corcoran D, Dooley JS, Fanning S, Lucey B, Matsuda M, McDowell DA, Megraud F, Millar BC, O'Mahony R, O'Riordan L, O'Rourke M, Rao JR, Rooney PJ, Sails A, Whyte P. 2005. Campylobacter. Vet Res 36:351–382. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2005012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amour C, Gratz J, Mduma E, Svensen E, Rogawski ET, McGrath M, Seidman JC, McCormick BJ, Shrestha S, Samie A, Mahfuz M, Qureshi S, Hotwani A, Babji S, Trigoso DR, Lima AA, Bodhidatta L, Bessong P, Ahmed T, Shakoor S, Kang G, Kosek M, Guerrant RL, Lang D, Gottlieb M, Houpt ER, Platts-Mills JA, Etiology. Risk Factors, and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development Project Network Investigators. 2016. Epidemiology and impact of Campylobacter infection in children in 8 low-resource settings: results from the MAL-ED study. Clin Infect Dis 63:1171–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2015. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2013. EFSA J 13:3991. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.3991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahin O, Morishita TY, Zhang Q. 2002. Campylobacter colonization in poultry: sources of infection and modes of transmission. Anim Health Res Rev 3:95–105. doi: 10.1079/AHRR200244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Food Safety Authority. 2011. Scientific opinion on Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain. EFSA J 9:2105. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenquist H, Boysen L, Krogh AL, Jensen AN, Nauta M. 2013. Campylobacter contamination and the relative risk of illness from organic broiler meat in comparison with conventional broiler meat. Int J Food Microbiol 162:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin J. 2009. Novel approaches for Campylobacter control in poultry. Foodborne Pathog Dis 6:755–765. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saint-Cyr MJ, Guyard-Nicodeme M, Messaoudi S, Chemaly M, Cappelier JM, Dousset X, Haddad N. 2016. Recent advances in screening of anti-Campylobacter activity in probiotics for use in poultry. Front Microbiol 7:553. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svetoch EA, Eruslanov BV, Levchuk VP, Perelygin VV, Mitsevich EV, Mitsevich IP, Stepanshin J, Dyatlov I, Seal BS, Stern NJ. 2011. Isolation of Lactobacillus salivarius 1077 (NRRL B-50053) and characterization of its bacteriocin, including the antimicrobial activity spectrum. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:2749–2754. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02481-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Zoete MR, van Putten JP, Wagenaar JA. 2007. Vaccination of chickens against Campylobacter. Vaccine 25:5548–5557. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widders PR, Perry R, Muir WI, Husband AJ, Long KA. 1996. Immunisation of chickens to reduce intestinal colonisation with Campylobacter jejuni. Br Poult Sci 37:765–778. doi: 10.1080/00071669608417906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyszynska A, Raczko A, Lis M, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK. 2004. Oral immunization of chickens with avirulent Salmonella vaccine strain carrying C. jejuni 72Dz/92 cjaA gene elicits specific humoral immune response associated with protection against challenge with wild-type Campylobacter. Vaccine 22:1379–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layton SL, Morgan MJ, Cole K, Kwon YM, Donoghue DJ, Hargis BM, Pumford NR. 2011. Evaluation of Salmonella-vectored Campylobacter peptide epitopes for reduction of Campylobacter jejuni in broiler chickens. Clin Vaccine Immunol 18:449–454. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00379-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley AM, Wang J, Hudson DL, Grant AJ, Jones MA, Maskell DJ, Stevens MP. 2010. Evaluation of live-attenuated Salmonella vaccines expressing Campylobacter antigens for control of C. jejuni in poultry. Vaccine 28:1094–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annamalai T, Pina-Mimbela R, Kumar A, Binjawadagi B, Liu Z, Renukaradhya GJ, Rajashekara G. 2013. Evaluation of nanoparticle-encapsulated outer membrane proteins for the control of Campylobacter jejuni colonization in chickens. Poult Sci 92:2201–2211. doi: 10.3382/ps.2012-03004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neal-McKinney JM, Samuelson DR, Eucker TP, Nissen MS, Crespo R, Konkel ME. 2014. Reducing Campylobacter jejuni colonization of poultry via vaccination. PLoS One 9:e114254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobierecka PA, Wyszynska AK, Gubernator J, Kuczkowski M, Wisniewski O, Maruszewska M, Wojtania A, Derlatka KE, Adamska I, Godlewska R, Jagusztyn-Krynicka EK. 2016. Chicken anti-Campylobacter vaccine—comparison of various carriers and routes of immunization. Front Microbiol 7:740. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro MA, Baqar S, Hall ER, Chen YH, Porter CK, Bentzel DE, Applebee L, Guerry P. 2009. Capsule polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against diarrheal disease caused by Campylobacter jejuni. Infect Immun 77:1128–1136. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01056-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerry P, Poly F, Riddle M, Maue AC, Chen YH, Monteiro MA. 2012. Campylobacter polysaccharide capsules: virulence and vaccines. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2:7. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertolo L, Ewing CP, Maue A, Poly F, Guerry P, Monteiro MA. 2013. The design of a capsule polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against Campylobacter jejuni serotype HS15. Carbohydr Res 366:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maue AC, Mohawk KL, Giles DK, Poly F, Ewing CP, Jiao Y, Lee G, Ma Z, Monteiro MA, Hill CL, Ferderber JS, Porter CK, Trent MS, Guerry P. 2013. The polysaccharide capsule of Campylobacter jejuni modulates the host immune response. Infect Immun 81:665–672. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01008-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgins DC, Barjesteh N, St Paul M, Ma Z, Monteiro MA, Sharif S. 2015. Evaluation of a polysaccharide conjugate vaccine to reduce colonization by Campylobacter jejuni in broiler chickens. BMC Res Notes 8:204. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1203-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlyshev AV, Champion OL, Churcher C, Brisson JR, Jarrell HC, Gilbert M, Brochu D, St Michael F, Li J, Wakarchuk WW, Goodhead I, Sanders M, Stevens K, White B, Parkhill J, Wren BW, Szymanski CM. 2005. Analysis of Campylobacter jejuni capsular loci reveals multiple mechanisms for the generation of structural diversity and the ability to form complex heptoses. Mol Microbiol 55:90–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxon R, Bayliss C, Hood D. 2006. Bacterial contingency loci: the role of simple sequence DNA repeats in bacterial adaptation. Annu Rev Genet 40:307–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkhill J, Wren BW, Mungall K, Ketley JM, Churcher C, Basham D, Chillingworth T, Davies RM, Feltwell T, Holroyd S, Jagels K, Karlyshev AV, Moule S, Pallen MJ, Penn CW, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rutherford KM, van Vliet AH, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. 2000. The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403:665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newell DG, Koopmans M, Verhoef L, Duizer E, Aidara-Kane A, Sprong H, Opsteegh M, Langelaar M, Threfall J, Scheutz F, van der Giessen J, Kruse H. 2010. Food-borne diseases—the challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. Int J Food Microbiol 139(Suppl 1):S3–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cogliani C, Goossens H, Greko C. 2011. Restricting antimicrobial use in food animals: lessons from Europe. Microbe (Wash, DC) 6:274–279. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park YH, Hamidon F, Rajangan C, Soh KP, Gan CY, Lim TS, Abdullah WNW, Liong MT. 2016. Application of probiotics for the production of safe and high-quality poultry meat. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 36:567–576. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2016.36.5.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saint-Cyr MJ, Haddad N, Taminiau B, Poezevara T, Quesne S, Amelot M, Daube G, Chemaly M, Dousset X, Guyard-Nicodeme M. 8 July 2016. Use of the potential probiotic strain Lactobacillus salivarius SMXD51 to control Campylobacter jejuni in broilers. Int J Food Microbiol doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]