Abstract

Mucin-type O-glycosylation is the most abundant type of O-glycosylation. It is initiated by the members of the polypeptide N-acetyl-α-galactosaminyltransferase (ppGalNAc-T) family and closely associated with both physiological and pathological conditions, such as coronary artery disease or Alzheimer's disease. The lack of direct and selective inhibitors of ppGalNAc-Ts has largely impeded research progress in understanding the molecular events in mucin-type O-glycosylation. Here, we report that a small molecule, the plant flavonoid luteolin, selectively inhibits ppGalNAc-Ts in vitro and in cells. We found that luteolin inhibits ppGalNAc-T2 in a peptide/protein-competitive manner but not promiscuously (e.g. via aggregation-based activity). X-ray structural analysis revealed that luteolin binds to the PXP motif–binding site found in most protein substrates, which was further validated by comparing the interactions of luteolin with wild-type enzyme and with mutants using 1H NMR–based binding experiments. Functional studies disclosed that luteolin at least partially reduced production of β-amyloid protein by selectively inhibiting the activity of ppGalNAc-T isoforms. In conclusion, our study provides key structural and functional details on luteolin inhibiting ppGalNAc-T activity, opening up the way for further optimization of more potent and specific ppGalNAc-T inhibitors. Moreover, our findings may inform future investigations into site-specific O-GalNAc glycosylation and into the molecular mechanism of luteolin-mediated ppGalNAc-T inhibition.

Keywords: amyloid precursor protein (APP), crystal structure, glycoprotein, glycosylation inhibitor, glycosyltransferase, O-glycosylation, luteolin, ppGalNAc-T

Introduction

Mucin-type O-glycosylation (hereafter also referred to as O-GalNAc5 glycosylation) is the most abundant type of O-glycosylation and is closely relevant in physiological and pathological conditions, such as coronary artery disease (1), familial tumoral calcinosis (2), and Alzheimer's disease (3, 4). It has been clearly demonstrated that O-GalNAc glycosylation of amyloid precursor protein (APP) is important for its cell surface localization, endocytosis, and the production of amyloid β (Aβ) (5–7), which is the primary component of the parenchymal amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease (8). In mammals, O-GalNAc glycosylation is initiated by a family of 20 polypeptide N-acetyl-α-galactosaminyltransferases (ppGalNAc-Ts) (9, 10). These enzymes transfer GalNAc from the donor substrate, uridine diphosphate N-acetyl-α-galactosamine (UDP-GalNAc), to an acceptor substrate protein, forming GalNAc-Ser/Thr (also known as the Tn antigen), and release the free UDP (9) (Fig. 1A). The acceptor substrate specificities of these isoforms are distinct but partly overlapping (11–13). This is reflected by increasing evidence that different ppGalNAc-Ts could also elicit distinct biological outcomes (14). The site-specific O-GalNAc glycans on proteins catalyzed by different ppGalNAc-T isoforms are closely related with protein processing, stability, and secretion (14). Change of O-GalNAc glycans on specific sites of protein substrates, such as angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) or APP, is deeply involved in coronary artery disease or Alzheimer's disease (1, 4, 7, 15). Therefore, development of ppGalNAc-T inhibitor could provide a useful tool for research on the molecular mechanism of O-GalNAc glycosylation in human development and disease.

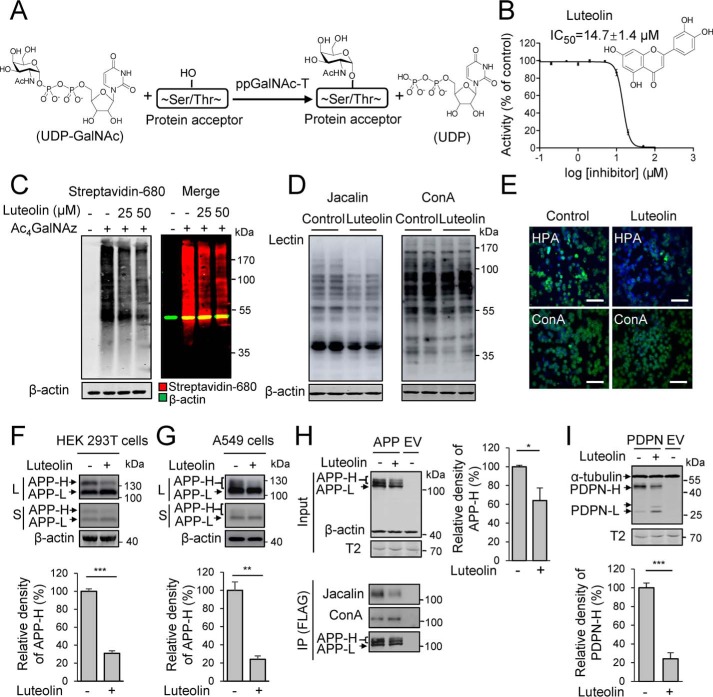

Figure 1.

Luteolin functions as a potent inhibitor in vitro and in cells. A, schematic representation of the initiation of O-GalNAc glycosylation by ppGalNAc-Ts. B, chemical structure and IC50 of luteolin against ppGalNAc-T2 detected by HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay. The data are expressed as percentages of the control (DMSO, 100%) and are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). C, effects of luteolin on the O-GalNAc glycosylation in CHO-ldlD cells detected by the metabolic labeling and click chemistry. CHO-ldlD cells were preincubated with 100 μm Ac4GalNAz for 12 h and then treated with the indicated concentrations of luteolin for an additional 36 h. Total cell lysates were collected to react with biotin alkyne for 3 h before being analyzed by streptavidin blotting. D, effects of luteolin on glycans of proteins in HEK 293T cells. Cells were incubated with luteolin at 25 μm for 36 h, and total lysates were analyzed by lectin blot. Control, DMSO-treated cells. E, effects of luteolin on glycans in Jurkat cells detected by immunofluorescence. Cells were treated with 25 μm luteolin for 24 h and stained with different lectins. Green, HPA and ConA; blue, nuclei stained with DAPI. Scale bars, 50 μm. Control, DMSO-treated cells. F and G, effects of luteolin on the glycosylation of endogenous APP in HEK 293T cells (F) and A549 cells (G). Cell were incubated with 25 μm luteolin for 36 h and collected and analyzed by Western blotting. L, long-term exposure; S, short-term exposure. H and I, effects of luteolin on the glycosylation of transfected APP (H) and PDPN (I) in HEK 293T cells. FLAG-tagged APP and PDPN were transfected for 24 h and then incubated with 25 μm luteolin for another 24 h. APP was then immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates (Input) using an anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin. The mean density of APP-H or PDPN-H was quantified and normalized with APP-L or PDPN-L. Cells expressing APP or PDPN without luteolin treatment were considered 100%. IP, immunoprecipitation. 50 μg of total protein was used to analyze endogenous APP, and 10 μg was used for transfected APP and PDPN. The data shown represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. F–I, two-tailed Student's t test. β-Actin and α-tubulin were used as loading control. EV, empty vector.

Whereas several small molecules are reported to perturb O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells (16–18), such as the uridine derivative 1-68A and GalNAc analogue Ac5GalNTGc, most of these compounds are donor substrate derivatives (16, 18). We have described UDP-GalNAc derivatives that acted as poor binders of ppGalNAc-T2 (19). Recently, a mixed-mode selective inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T3 has been reported (17). Natural products and approved drugs are structurally diverse and have well-characterized bioactivity, safety, and pharmacological function. Luteolin is an effective ingredient and natural product found in African and Chinese traditional herbal medicines with safe profiles (20, 21). As a flavonoid, several co-crystal studies revealed that luteolin interacts with protein kinase, tankyrases, receptors, etc. (22–27). However, it is unknown whether luteolin could affect protein O-glycosylation.

In this context, we identified luteolin as a direct protein substrate-competitive inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T2. The competitive nature of this flavonoid versus peptide substrates was also supported by the crystal structure of ppGalNAc-T2 in complex with UDP and luteolin, which allowed us to pinpoint the flavonoid in the peptide-binding groove and in particular where the PXP motif (where X is usually a small hydrophobic residue) of protein substrates is recognized. The location of luteolin was also supported by 1H NMR binding experiments. Moreover, we found that luteolin reduced the production of Aβ through selectively inhibiting ppGalNAc-Ts, which provided a putative molecular mechanism of luteolin in reducing the Alzheimer's disease pathologies.

Results

Identification of luteolin as an inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T2 that reduces O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells

Luteolin was initially identified to be an inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T2 from 4757 agents, including 1659 Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs and 3098 natural products and synthetic compounds, by a newly developed high-throughput screening assay for ppGalNAc-T2 (data not shown). Following validation with the HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay (28–30), we found that luteolin could inhibit ppGalNAc-T2 catalytic activity with an IC50 of ∼15 μm using EA2 peptide (PTTDSTTPAPTTK) as acceptor substrate (Fig. 1B). ppGalNAc-T2 is ubiquitously expressed in a variety of cells, and several structural studies revealed that EA2 is an effective substrate of ppGalNAc-T2 (31–33).

To evaluate whether luteolin had specific inhibition against O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells, first, we detected the metabolic labeling of GalNAz (N-azido-acetylgalactosamine) in CHO-ldlD cells with or without luteolin treatment by using click chemistry. CHO-ldlD is an O-GalNAc glycosylation–deficient cell line due to the lack of the epimerase that converts UDP-Glc/GlcNAc to UDP-Gal/GalNAc (34), and then the extra addition of peracetylated N-azidoacetylgalactosamine (Ac4GalNAz) in the cell culture will lead to specific formation of GalNAz modification (35). We incubated CHO-ldlD cells with Ac4GalNAz and treated with or without the indicated concentrations of luteolin. The cells were collected for click-chemistry reaction and analyzed by streptavidin blotting. We found that luteolin showed a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on the GalNAz signal, indicating a potent inhibitory effect of luteolin on O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells (Fig. 1C).

Next, we investigated the inhibitory selectivity of luteolin in several cell lines. Three lectins, namely Jacalin (which binds to Gal β1–3GalNAc, GalNAc; O-GalNAc glycans), Helix pomatia agglutinin (HPA; binds to α-linked terminal GalNAc), and concanavalin A (ConA; binds to high mannose), were used. Lectin blots of total lysates of HEK 293T cells showed a substantial reduction in the Jacalin signal but not ConA signal (Fig. 1D). In Jurkat cells, immunofluorescence detection indicated that luteolin could also suppress the HPA but not ConA signal on the cell surface (Fig. 1E). These results demonstrated that luteolin selectively reduced the global levels of O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells. In agreement with the results above, we detected the inhibitory effects of luteolin on the endogenous APP, a typical O-GalNAc glycosylated protein (5, 7), in HEK 293T cells and A549 cells. We found that luteolin could significantly reduce the ratio of the high-molecular weight band of APP (APP-H; O-GalNAc-glycosylated APP (7)) with a 75 and 80% reduction in HEK 293T cells and A549 cells, respectively (Fig. 1, F and G). Meanwhile, we transfected APP and another typical O-GalNAc glycosylated protein podoplanin (PDPN) (36) in HEK 293T cells to test the inhibitory effects of luteolin. After luteolin treatment, the APP-H and its Jacalin signal were significantly decreased (Fig. 1H). In contrast, there was little change in APP-L (non-O-GalNAc glycosylated APP) or ConA signal (Fig. 1H). Besides APP, luteolin treatment also led to a shift of PDPN to a lower molecule weight, which is consistent with the effect of O-GalNAc glycan depletion (37) (Fig. 1I). Meanwhile, a similar expression level of ppGalNAc-T2 was observed in HEK 293T treated with or without luteolin, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of luteolin should not be attributed to the alteration in the ppGalNAc-T2 expression (Fig. 1, H and I). Those experiments suggested that luteolin exhibited selective inhibition toward O-GalNAc glycosylation on proteins in cells.

Luteolin is a selective and protein substrate-competitive inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T2

Flavonoids have been reported as a family of molecules with multiple targets through promiscuous mechanism, in particular due to colloidal aggregation (38). To rule out this possibility on the inhibitory effects of luteolin against ppGalNAc-T2 in our enzyme system, dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis and spin-down experiments were performed. The DLS analysis showed that the particles in the 50–1000-nm size of luteolin were gradually reduced with the increased addition of Triton X-100 and almost undetectable when Triton X-100 reached 0.2% (Fig. 2A and Fig. S1). Then the spin-down experiments using our ppGalNAc-T assay containing 0.2% Triton X-100 also showed that the inhibition of luteolin against ppGalNAc-T2 had no significant difference after centrifugation (Fig. 2B). These results strongly suggested that the inhibition of luteolin on ppGalNAc-T2 with 0.2% Triton X-100 was not due to the aggregation-based mechanism.

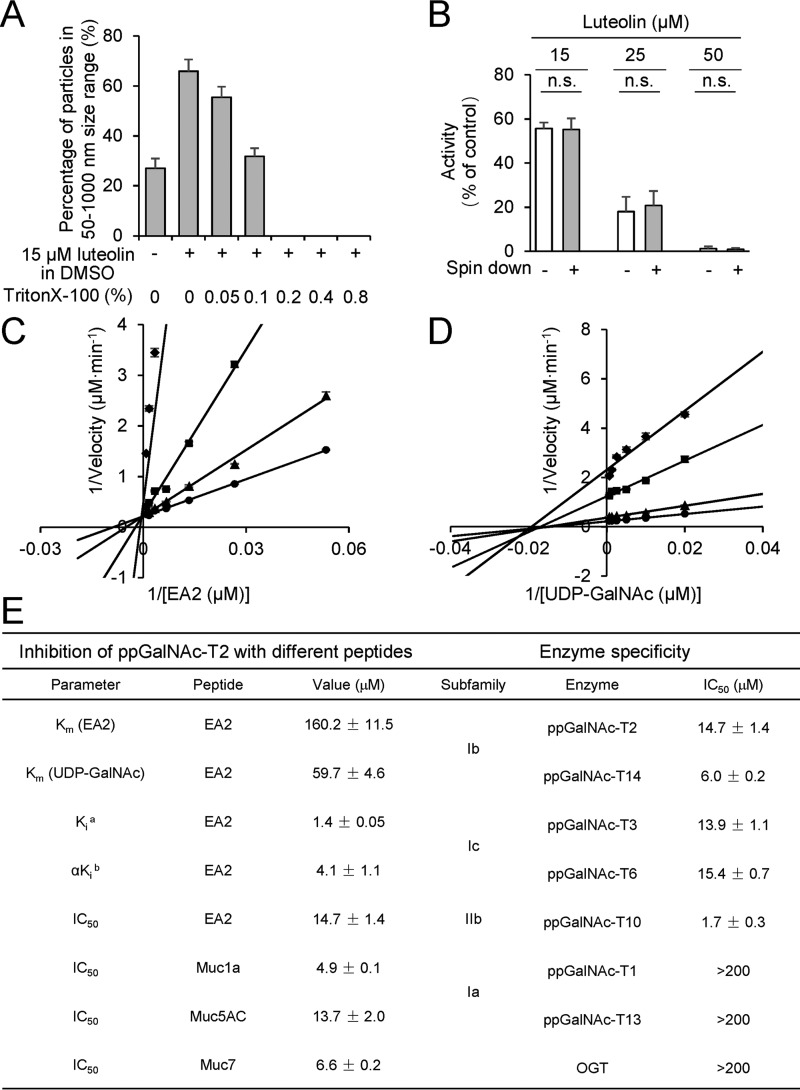

Figure 2.

Kinetics and selectivity analyses of luteolin inhibition mechanism on ppGalNAc-T2. A, the change of percentage of particles in the 50–1000-nm size range with luteolin and different concentrations of Triton X-100 (v/v). The size of particles was measured by DLS. B, spin down experiments for luteolin in our HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay with 0.2% Triton X-100 (v/v). Enzyme reactions were performed before or after centrifugation (16,000 × g, 1 h). The data are expressed as percentages of the control (DMSO, 100%). Data above are shown as the mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3). Two-tailed Student's t test was used; n.s., no significant difference. C, luteolin shows competitive inhibition (Ki = 1.4 ± 0.05 μm) with respect to EA2 substrate in the presence of 1200 μm UDP-GalNAc. D, UDP-GalNAc showed non-competitive inhibition (αKi = 4.1 ± 1.1 μm) in the presence of 1200 μm EA2. The concentration of luteolin was 0 μm (●), 5 μm (▴), 10 μm (■), and 20 μm (♦). E, kinetics parameter of luteolin inhibition on ppGalNAc-T2 with various peptide substrates and the selectivity of luteolin within the ppGalNAc-T family with EA2 peptide. a, competitive inhibition constant; b, non-competitive inhibition constant. The data shown in E are represented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

To address the inhibitory mechanism of luteolin on ppGalNAc-T2, we performed enzyme kinetics assays (Fig. 2, C and D). The enzyme kinetics experiments showed that luteolin exhibited competitive inhibition with respect to EA2 substrate (Ki ∼1.4 μm; Fig. 2C) and non-competitive inhibition with respect to the UDP-GalNAc (αKi ∼4.1 μm; Fig. 2D). Luteolin bound ∼100-fold more to ppGalNAc-T2 than the EA2 peptide did to ppGalNAc-T2 (Km ∼160 μm; Fig. 2E).

Prompted by the potent inhibition of luteolin on ppGalNAc-T2, we also measured the IC50 values of luteolin in the presence of various peptide substrates and ppGalNAc-T isoforms. We found out that luteolin displayed poor substrate selectivity (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2). In addition to ppGalNAc-T2, we also evaluated the effect of luteolin on other members of ppGalNAc-T family and human O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) (39–41). Luteolin inhibited with similar IC50 values (low micromolar values) members of both subfamilies Ib and Ic (42), such as ppGalNAc-T14 (note that ppGalNAc-T2 also belongs to the Ib subfamily) and ppGalNAc-T3/T6, respectively, whereas it showed a more potent inhibition on ppGalNAc-T10 (subfamily IIb) with an IC50 of 1.7 μm (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2). In contrast to the effects on these ppGalNAc-Ts, luteolin displayed a poor inhibition on ppGalNAc-T1 and T13, two ppGalNAc-Ts from subfamily Ia with high homology between their amino acid sequences (Fig. 2E and Fig. S2). Likewise, luteolin had little effect on OGT either. These results suggested that luteolin displayed selective inhibition on ppGalNAc-Ts from subfamilies Ib, Ic, and IIb and was a poor inhibitor of subfamily Ia and other distant glycosyltransferases, such as OGT (Fig. 2E).

X-ray structure and 1H NMR binding experiments of ppGalNAc-T2/mutants with luteolin

To further elucidate the luteolin-binding mode, we obtained crystals of ppGalNAc-T2 in complex with UDP/Mn2+ that were subsequently soaked with the flavonoid. Crystals of the complex diffracted to a resolution of 2.3 Å, which allowed us to build a final model with good refinement statistics (Table S1). Consistent with the above kinetics data, the crystal structure revealed that this flavonoid bound to the peptide-binding groove (Fig. 3A). The presence of UDP in the active site at a distance of ∼8 Å from luteolin also supported the non-competitive character of this flavonoid versus UDP-GalNAc inferred from kinetics data (Fig. 2D).

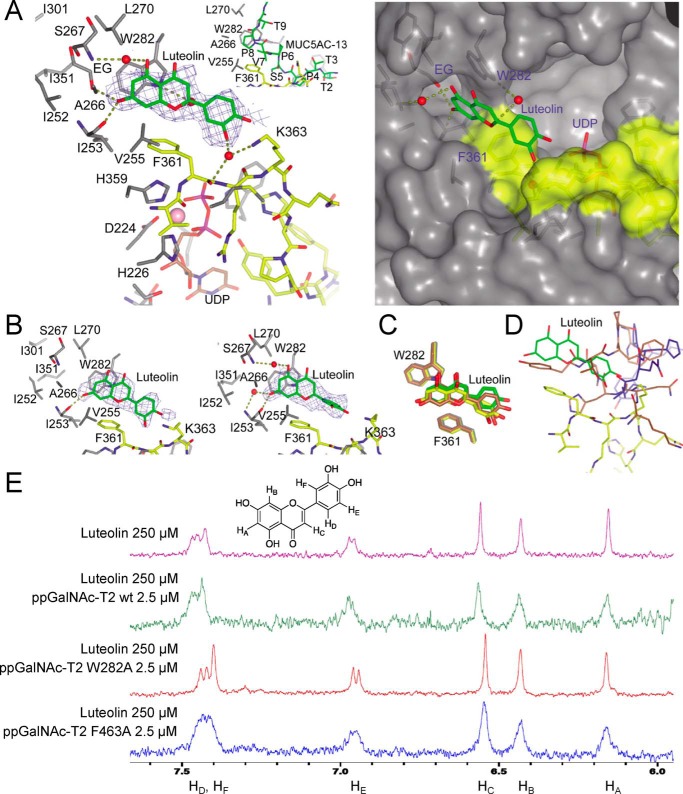

Figure 3.

X-ray structure and 1H NMR binding experiments of ppGalNAc-T2/mutants with luteolin. A, view (left) of the luteolin-binding site of the ppGalNAc-T2·UDP-luteolin complex. The crystal structure of ppGalNAc-T2 in complex with UDP and MUC5AC-13 (32) is shown for comparison purposes (inset). A surface representation (right) of the ppGalNAc-T2·UDP-luteolin complex depicts the pocket present in these enzymes. Part of the residues forming the luteolin-binding site and the pocket are shown in gray, whereas residues of the flexible loop are depicted in yellow. Luteolin/MUC5AC-13 and UDP are shown as green and brown carbon atoms, respectively. Ethylene glycol is shown as gray carbon atoms, whereas water molecules are depicted as red spheres. Hydrogen bond interactions are shown as dotted deep olive lines. Electron density maps are Fo − Fc syntheses (blue) contoured at 2.2 σ for luteolin. B, view of the two additional luteolin molecules present in the AU. C, overlay of the ppGalNAc-T2 molecules in complex with luteolin showing the flexibility mainly in the dihydroxyphenyl moiety. Luteolin and Trp282/Phe361 are depicted as green, yellow, and brown carbon atoms. D, overlay of one of the monomers containing luteolin with ppGalNAc-T2 inactive form in complex with UDP (Protein Data Bank entry 2FFV (31)) and ppGalNAc-T2 inactive form in complex with MUC5AC-Cys13 (Protein Data Bank entry 5AJN (32)). This figure shows that luteolin has steric hindrance with both inactive forms of ppGalNAc-T2. The flexible loop for the active and inactive forms is shown in yellow and blue/brown, respectively. E, 1H NMR spectra were recorded to compare the effect of binding on the luteolin signal broadening. Shown are 1H NMR spectra of free luteolin and luteolin with ppGalNAc-T2 wild type and the mutants W282A and F463A.

A closer inspection of the luteolin-binding site revealed that the flavonoid is sandwiched between β6, the loop between β6 and β7, β8, and the flexible loop between β10 and α11 (Fig. S3). The compound is also close to the lectin domain from the neighboring monomer present in the asymmetric unit (AU). Note that in these orthorhombic crystals, six molecules of ppGalNAc-T2 are arranged in three independent dimers in the AU (33). However, luteolin only accomplishes direct interactions with residues located in the peptide-binding groove of one of the monomers, ruling out the potential contribution of the lectin domain of the neighboring ppGalNAc-T2 to the binding of the flavonoid (Fig. S4). Although dimers have been described by small-angle X-ray scattering experiments (32), it is not clear whether this particular crystallographic dimer is present in solution because part of the peptide-binding groove is partly occluded by residues of the neighboring monomer, impeding the binding of long peptides to the enzyme (33). A more detailed evaluation of the binding site reveals that the flavonoid competes specifically with the PXP motif found on most protein substrates (Fig. 3A). The PXP motif–binding site is formed by Phe361, Phe280, and Trp282, which are conserved residues among the ppGalNAc-T isoenzymes. These are key residues in the recognition of common peptide motifs, such as Pro-X-Pro (where X is usually a small hydrophobic residue) found in acceptor substrates (31, 32). The 5,7-dihydroxy-4-chromenone ring is engaged in parallel and edge-to-face π-π interactions with Trp282 and Phe361, respectively, and π-CH interactions with Val255 (Fig. 3A). Phe361 also establishes CH-π interactions with the dihydroxyphenyl moiety. In addition, there are direct hydrogen bonds between the 7-hydroxyl group and Ile253 backbone and water molecule–mediated hydrogen bonds between the 5-hydroxyl group and Ser267 backbone, the 3′-hydroxyl group and Phe361/Lys363, and the oxygen ring and Trp282 (Fig. 3A). The 7-hydroxyl group also interacts with an ethylenglycol molecule, which is located in a hydrophobic pocket formed by Ala266, Ile252, Ile253, Leu270, Ile301, and Ile351 (Fig. 3A).

The AU also depicted the presence of two additional luteolin molecules (Fig. 3B) with less defined density compared with the one displayed in Fig. 3A. The 5,7-dihydroxy-4-chromenone adopted almost identical positions (atomic shift average of 0.62 Å; Fig. 3C), whereas the dihydroxyphenyl moiety was more flexible (atomic shift average of 1.50 Å; Fig. 3C). Overall, the major interactions with the enzyme are conserved, whereas the water molecule-mediated hydrogen bonds between Trp282 and residues of the flexible loop are lost (Fig. 3A), supporting again the flexibility and the potential weaker binding affinity of the dihydroxyphenyl moiety in opposition to the chromenone ring. Strikingly, luteolin can only access the active form of ppGalNAc-T2 (Fig. 3D), which suggests that the flexible loop must adopt its closed conformation, leading to the unblocking of the PXP motif binding site and consequently allowing the entrance of luteolin (Fig. 3D).

To further validate the location of luteolin inferred from the crystal structure, 1H NMR experiments were conducted. 1H NMR spectra were recorded to compare the effect of binding on the luteolin signal broadening (43–45). Due to its low solubility, luteolin concentration was set to 250 μm (final concentration of DMSO was 8%). Samples with different protein concentrations were assayed. However, the best results were obtained at 2.5 μm in the presence of 50 μm UDP and MnCl2.

Fig. 3E and Fig. S5 shows the 1H spectra of free luteolin and luteolin with ppGalNAc-T2 wild type and the mutants W282A and F463A. When ppGalNAc-T2 wild type is incubated with a solution containing luteolin, all signals become broad and less intense due to tight binding to the protein. However, no signal broadening was observed when luteolin was in the presence of the W282A mutant, implying that a significant decrease of the affinity is achieved. This supports the crystal structure where the benzopyronic moiety interacts with Trp282. In the sample containing luteolin and the mutant F463A (located in the lectin domain from the neighboring ppGalNAc-T2), the broad signals indicate strong binding with the protein, suggesting that the lectin domain from the neighboring monomer forming the dimer in the asymmetric unit does not interact with this flavonoid. Note that Phe463 is the closest residue to luteolin coming from the lectin domain of the neighboring ppGalNAc-T2.

Structure–function analysis of luteolin analogue inhibition on ppGalNAc-T2

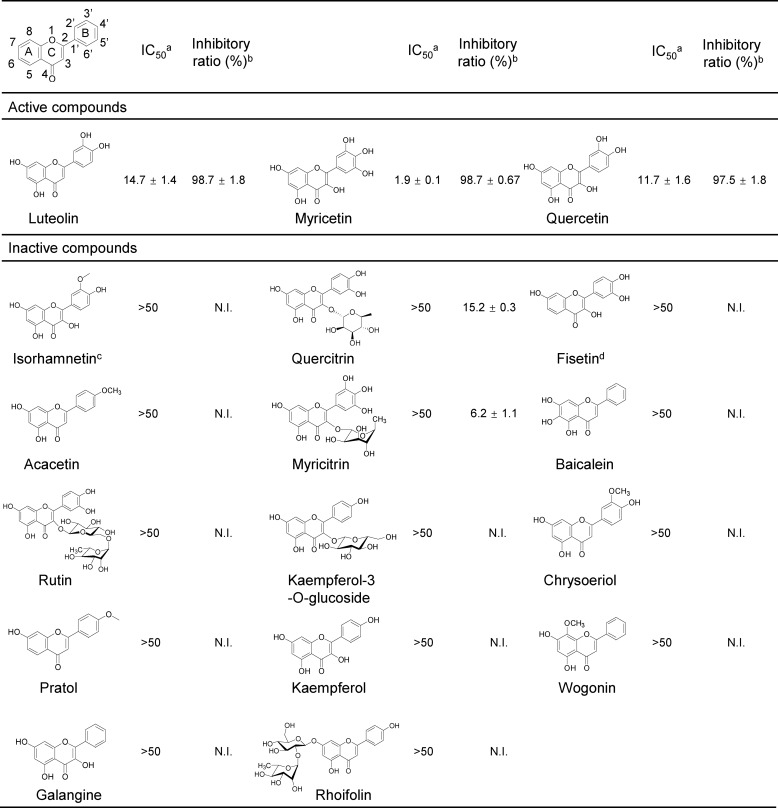

Considering that flavonoid has drawn great attention for its beneficial effect (46), we further examined the inhibitory effects of another 16 flavonoid analogues (Fig. 4). Most of them showed <10% inhibition on the activity of ppGalNAc-T2 at 50 μm in our HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay, suggesting that the inhibition on ppGalNAc-T2 is only achieved by specific flavonoids. To explore the structure and activity relationship of luteolin, we also compared the inhibitory effects of flavonoid analogues with or without these hydroxyl groups. For example, isorhamnetin and chrysoeriol, which contained bulkier substituents at position 3′ in the B ring, exhibited poor inhibitory effect; fisetin, which had no OH-5 in the A ring, exhibited no inhibitory effect at 50 μm and only ∼20% effects when we raised its amount to 200 μm. Both OH-3′ and OH-5 do not make direct interactions with the enzyme but are engaged in water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the enzyme, explaining their importance in the inhibitory effects on ppGalNAc-T2. In addition, bulkier substituents at position 3′ might cause the destabilization of the flexible loop (Figs. 3A and 4), explaining the lack of potency of these compounds. Other flavonoids, such as rhoifolin, which contains a polar dissacharide coupled to the 7-hydroxyl group in the A ring, is a poor inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T2. In this case, the sugar moiety might cause steric hindrance with residues within the pocket or lead to the destabilization of the hydrophobic pocket (Figs. 3A and 4).

Figure 4.

Structure–function analysis of luteolin analogues using an HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay with EA2 peptide. a, the IC50 are calculated as percentages of the control (DMSO, 100%) and shown as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). b, the inhibitory ratio (%) was calculated with the positive control (DMSO, 0%) (50 μm compounds). c, isorhamnetin did not show any inhibitory activity at 200 μm. d, the inhibitory ratio of fisetin at 200 μm is 23.87 ± 0.4%. N.I., no inhibition.

Although rutin, quercitrin, and myricitrin have both hydroxyl groups, they also bear large substituents in position 3 of the C ring as sugar moieties that greatly reduced their inhibitory potency (Fig. 4). In these compounds, the breaking of the planarity between the chromenone and phenyl rings (47), imposed by the sugar moieties, might lead to constraints in the structural disposition of the rings. This might disfavor an optimal interaction with Trp282 and Phe361 or cause steric hindrance with the mobile flexible loop, which might explain why these compounds are poor inhibitors of ppGalNAc-T2. On the contrary, quercetin or myricetin, luteolin-like compounds containing small substituents in position 3 of the C ring, rendered similar inhibitory potencies to luteolin, suggesting not only that these flavonoids adopted a similar structure as luteolin but also that the 3-hydroxyl group or small substituents in this position did not contribute to the binding of the enzyme (Figs. 3A and 4).

Luteolin selectively inhibits the catalytic activity of ppGalNAc-Ts on APP in cells

Luteolin exhibited enzyme selectivity on EA2 peptide in the in vitro enzyme assay, which led us to investigate whether it also has same selectivity in cells. Luteolin has been reported to reduce Aβ production in an Alzheimer's disease (AD) model mouse (48, 49). APP is the precursor of Aβ and also is a well-known O-GalNAc–glycosylated protein in AD (5–7, 50). Therefore, we chose APP as a protein substrate to test the specificity and selectivity of luteolin in cells.

We transiently co-expressed APP and different ppGalNAc-Ts into HEK 293T cells and treated the cells with luteolin (Fig. 5A). We found that all of the tested ppGalNAc-Ts could glycosylate APP, but the bands of O-GalNAc glycosylated APP (APP-H bands) for each ppGalNAc-Ts were different. Luteolin decreased the APP-H bands catalyzed by ppGalNAc-T2 or T3 but not by T1 or T13 (Fig. 5A), suggesting that luteolin selectively inhibited ppGalNAc-T isoforms in cells. To further confirm this observation, we synthesized three peptides from APP as the acceptor substrates for ppGalNAc-T activity assay (Fig. 5, B and C). These peptides contained the dominant glycosylation sites (Thr291, Thr292, Thr576, and Thr577 for APP695; Thr353 for APP770), which have been reported to be crucial for APP processing (7, 50). An HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay showed that both peptide 1 and peptide 3 could be efficiently glycosylated by ppGalNAc-T2 and ppGalNAc-T3, whereas ppGalNAc-T1 showed very weak catalytic activity toward them (Fig. 5C). Peptide 2 could be only catalyzed by ppGalNAc-T3. ppGalNAc-T13 could not glycosylate all of the three peptides (Fig. 5C). This result is consistent with the report of Kong et al. (12) and clearly indicated that ppGalNAc-T isoforms have different preference for glycosylation sites on APP. Here, ppGalNAc-T13 may glycosylate other sites in cells that are not covered in our peptides, such as sequential triple T (28, 29) on APP. Furthermore, upon treatment with luteolin, the product peaks on these peptides resulting from the ppGalNAc-T2 and ppGalNAc-T3 were largely blocked (Fig. 5C). However, there was no big difference in the peak produced by ppGalNAc-T1 after luteolin treatment (Fig. 5C). Moreover, we also co-expressed ppGalNAc-T1, ppGalNAc-T2, and APP in HEK 293T cells and treated them with luteolin. The inhibitory effects of luteolin on the ppGalNAc-T2–catalyzed O-GalNAc glycans on APP could be masked by co-expressing ppGalNAc-T1 (Fig. 5D). These results are consistent with our observations in Figs. 2E and 5A and indicate that luteolin blocked the glycosylation on APP by inhibiting specific ppGalNAc-T isoforms not only in the in vitro enzyme assay but also in cells.

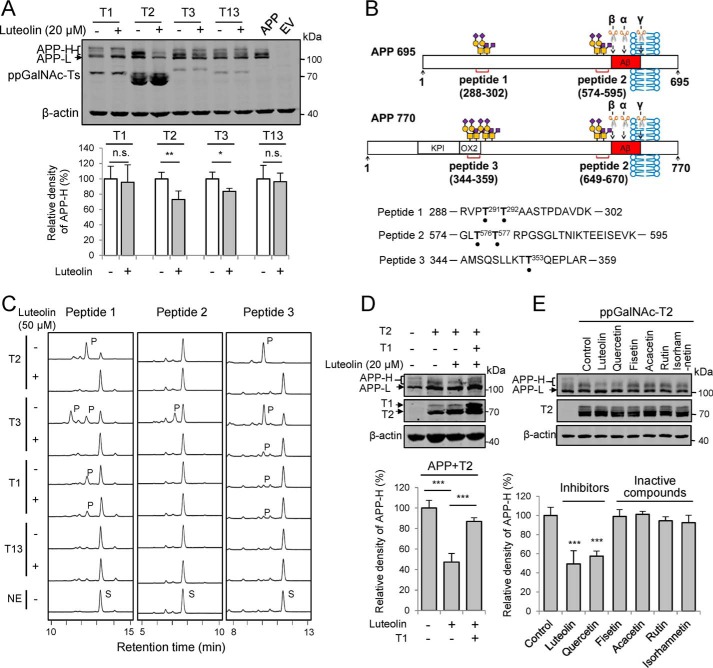

Figure 5.

Luteolin could inhibit the catalytic activity of ppGalNAc-Ts on APP in cells. A, effects of luteolin on the glycosylation on APP in HEK 293T cells overexpressing ppGalNAc-T1, T2, T3, or T13. FLAG-tagged APP alone or together with T1, T2, T3, or T13 were transfected into cells for 24 h before treating with 20 μm luteolin for an additional 24 h. The cell lysates were collected and analyzed for APP. B, schematic diagrams of synthesized APP-derived peptides. O-GalNAc glycosylation sites are marked with black dots (7). KPI, Kunitz-type protease inhibitor domain; OX2, OX2 domain (7); α, β, and γ, cleavage sites of α-, β-, and γ-secretases. C, luteolin (50 μm) can inhibit the glycosylation on APP-derived peptides catalyzed by ppGalNAc-T2 or T3. S, substrate peak; P, product peak. D, ppGalNAc-T1 attenuates the inhibitory effect of luteolin on O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP catalyzed by T2. E, effects of luteolin analogues on the O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP catalyzed by ppGalNAc-T2. For D and E, different combinations of APP, ppGalNAc-T2, or ppGalNAc-T1 plasmids were transfected into HEK 293T cells and then treated with the indicated compounds (20 μm) and analyzed as in A. For A, D, and E, the mean density of APP-H was quantified and normalized with APP-L and compared with the control (DMSO-treated cells co-transfected with APP and ppGalNAc-Ts without luteolin treatment, 100%). The data shown in A, D, and E represent mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; two-tailed Student's t test for A and one-way ANOVA for D and E. EV, empty vector.

In addition to luteolin, we also compared the inhibitory effects of its analogues on the ppGalNAc-T2, using APP as the protein substrate in the cell. Luteolin and quercetin showed pronounced inhibition (Fig. 5E). However, fisetin, acacetin, rutin, and isorhamnetin had no effect on the O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP (Fig. 5E), which is consistent with our crystal structure and structure–function analysis (Figs. 3A and 4). The results above suggest that luteolin could selectively inhibit the activity of certain ppGalNAc-Ts on APP in cells.

Decrease in O-GalNAc glycosylation by luteolin substantially reduces the generation of Aβ

O-GalNAc glycosylation has been reported to influence APP processing (4, 6, 7), so we wondered whether the inhibition of ppGalNAc-T by luteolin could affect Aβ production. We treated the Swedish-mutation APP stable cell line (HEK 293T-APP Swe cell) with luteolin and found that the production of APP-H and the amounts of total Aβ, Aβ40, and Aβ42 were decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and B). Meanwhile, the sAPPα and sAPPβ were also decreased as Aβ (Fig. 6B). Then we tested whether the reduction of Aβ was due to the decreased level of its O-GalNAc glycosylation. We analyzed the levels of Aβ in the CHO-K1 cells and its O-GalNAc glycan–deficient derivative CHO-ldlD cells. The O-GalNAc glycosylation of proteins was different in various cell lines (51). Notably, only one band of APP was observed in CHO-K1 and CHO-ldlD cells, suggesting that the amount of O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP in CHO-K1 and CHO-ldlD cells may be lower than that in HEK 293T cells. The immunoprecipitation analysis with Jacalin clearly demonstrated that the APP was glycosylated in the CHO-K1 cells but not in CHO-ldlD cells (Fig. 6C). Consistent with the effects in HEK 293T cells, we found that luteolin led to a significant decrease in the O-GalNAc glycans on APP and Aβ production in CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 6, C and D). However, the Aβ generation in transfected CHO-ldlD cells was at least 60% lower than that in CHO-K1 cells (Fig. 6D). After the restoration of O-GalNAc glycosylation by adding exogenous Gal and GalNAc into CHO-ldlD cell culture medium, the production of Aβ was partly enhanced (Fig. 6, E and F). However, luteolin largely decelerated the restoration process in both O-GalNAc glycosylation and Aβ production (Fig. 6, E and F). The total Aβ, Aβ40, and Aβ42 were reduced ∼30% by luteolin treatment with 800 μm Gal and GalNAc (Fig. 6, E and F). Additionally, we also treated APP/PS1 transgenic mice with luteolin at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day for 2 months and checked the O-GalNAc glycosylation level on APP and Aβ production in their brain homogenates. We found that the O-GalNAc glycosylation signal on APP was significantly reduced, as indicated by the immunoprecipitation analysis (Fig. 7A). The amounts of soluble Aβ40 and Aβ42 in the brains of APP/PS1 mice were reduced by nearly 30% (Fig. 7B). This preliminarily suggested that luteolin could affect O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP in mice. Taken together, these results suggested that decreased O-GalNAc glycosylation is a pivotal mechanism for the reduction of Aβ production after luteolin treatment.

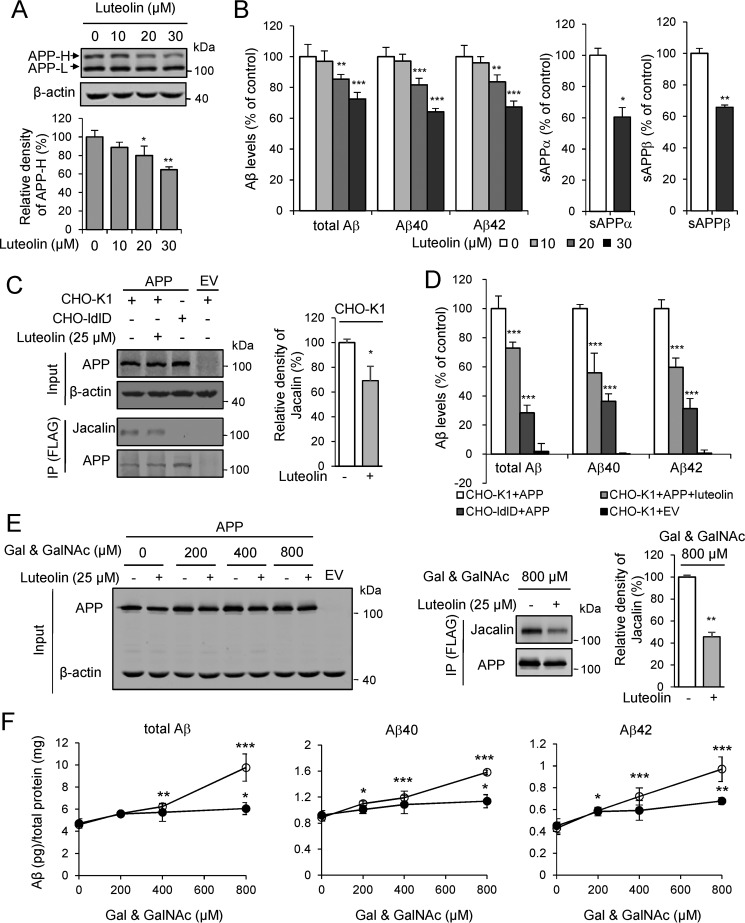

Figure 6.

Luteolin reduces the O-GalNAc glycosylation on APP and leads to a decrease of Aβ production in cells. A and B, dose-dependent effect of luteolin on the O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP and Aβ production in HEK 293T-APP Swe cells. Cells were incubated with luteolin for 24 h and then lysed and blotted for APP. The mean density of APP-H was quantified and normalized with APP-L and presented as percentages of control (DMSO, 100%). Aβ, sAPPα, and sAPPβ in the cell medium above were quantified by ELISA and normalized to the amount of total protein and presented as percentages of control (cells without luteolin treatment, 100%). C, effects of luteolin on O-GalNAc glycans of APP in CHO-K1 and CHO-ldlD cells. Cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged APP for 24 h followed by incubation with 25 μm luteolin for an additional 24 h. APP was then immunoprecipitated and detected by Jacalin staining. D, Aβs in the cell medium above were analyzed by ELISA. Control, CHO-K1 cells expressing APP without luteolin treatment, 100%. E, adding exogenous Gal and GalNAc restores the O-GalNAc glycosylation on APP in CHO-ldlD cells, but these effects could be attenuated by luteolin treatment (25 μm). F, Aβs in the cell medium above were quantified by ELISA and represented as Aβ (pg) per total protein (mg). ○, DMSO treatment; ●, 25 μm luteolin treatment. The mean density of Jacalin in C and E was quantified and normalized with APP and presented as a percentage of control (cells without luteolin treatment, 100%). Data represent mean ± S.D. (error bars), n = 3. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; for A, one-way ANOVA; for Aβ in B, D, and F, two-way ANOVA; for sAPPα and sAPPβ in B, C, and E, two-tailed Student's t test. IP, immunoprecipitation; EV, empty vector.

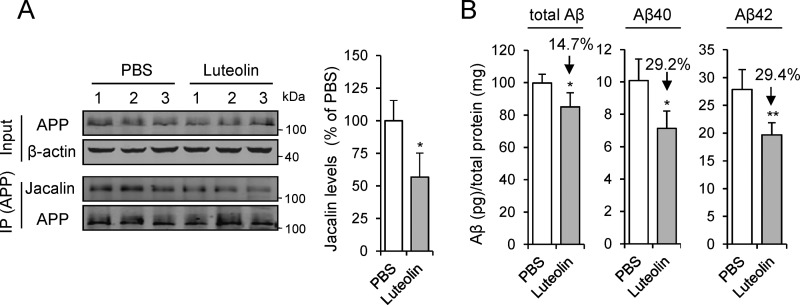

Figure 7.

The change of O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP and Aβ production in APP/PS1 transgenic mice with luteolin treatment. A, the O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP in extracts from brain homogenates was analyzed by immunoprecipitation (IP) of anti-APP antibody (C-T15). The mean density of Jacalin was quantified. B, soluble Aβs from brain homogenates of mice were detected by ELISA. Data are presented as a percentage of control (PBS-treated mice, 100%) and shown as mean ± S.D. (error bars) (n = 3 for Jacalin staining and n = 5 for Aβ detection). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; two-tailed Student's t test.

Discussion

Considering the increasing evidence for the involvement of ppGalNAc-Ts in the regulation of normal physiological functions as well as pathogenesis of various diseases (9, 14, 52), direct and bioactive ppGalNAc-T inhibitors could serve as useful tools for research and may have beneficial therapeutic effects for the treatment of some diseases. In this study, we reported for the first time that luteolin could directly inhibit ppGalNAc-Ts in a protein/peptide substrate–competitive manner and show selectivity in the ppGalNAc-T family. Additionally, we put forward that luteolin reduced the Aβ production at least partially by decreasing the O-GalNAc glycosylation via selectively inhibiting the activity of ppGalNAc-T isoforms, providing a putative mechanism for luteolin in modulating Alzheimer's disease pathologies.

ppGalNAc-T2 is a membrane-bound protein that needs detergent to make itself into an active state (53). Luteolin could aggregate in solution, leading to promiscuous inhibition in the absence of detergent. Our experiments proved that in our reaction system with 0.2% Triton X-100, luteolin did not function as an aggregate-based mechanism. In addition, based on our kinetic and crystal structure analysis, we clearly demonstrated that luteolin exhibited a classical competitive inhibitory mechanism against ppGalNAc-T2.

Our inhibition kinetics and X-ray structural demonstrated that luteolin acted as a protein substrate–competitive inhibitor of the ppGalNAc-T2 active form and competed specifically with the PXP motif present in most protein substrates (Fig. 3). The structure together with 1H NMR experiments also revealed that two major residues, Trp282 and Phe361, contribute mainly to the binding and are responsible for the likely better affinity of the chromenone ring in opposition to the more flexible dihydroxyphenyl ring. The structure also provided the discovery of a druggable pocket that might lead to the design and synthesis of more potent luteolin derivatives containing hydrophobic moieties in the 7-hydroxyl group or in position 6 of the chromenone ring. A combination of the crystal structure analysis together with the structure–inhibition relationship studies of the flavonoids on ppGalNAc-T2 provided more insights into the structural features responsible for an optimal inhibition and offered other exploitable positions in luteolin for the design of more potent compounds (e.g. the OH-3′ might be modified with polar groups to replace the water molecule visualized in the crystal structure, maximizing the interaction with the flexible loop).

Although several co-crystal studies showed that luteolin could also interact with other enzymes/proteins (22–27), there exists some difference between the interaction of luteolin with ppGalNAc-T2 and with other targets. The characteristics of the surrounding amino acids are also quite different. Utilizing the differential interaction of luteolin with ppGalNAc-T2 and other targets could greatly contribute to the development of a specific inhibitor.

The enzymatic activity assay in vitro and in cells showed that luteolin behaved as a pan-inhibitor of different ppGalNAc-Ts isoforms, including subfamilies Ib, Ic, and IIb (Fig. 2E). The key Trp (Trp282 in ppGalNAc-T2) establishing π-π interactions with the 5,7-dihydroxy-4-chromenone ring is conserved in all above ppGalNAc-Ts except for ppGalNAc-T10, which contains an Arg instead (Arg296). This residue might be engaged in a stronger cation-π interaction with the larger ring of luteolin, which can explain why ppGalNAc-T10 is the most sensitive to luteolin. However, it was not expected that luteolin showed a poor inhibition of subfamily Ia (Fig. 2E), because a closer evaluation of multiple sequence alignments and structural conservation analysis between ppGalNAc-T2 and the above isoforms revealed that the luteolin-binding site was more conserved between subfamilies Ia and Ib as compared with the members of Ic and IIb subfamilies (42). This suggested that other more complex features, such as the differences in the mobility of the flexible loop between different ppGalNAc-Ts, which in turn will probably depend on the surrounding residues, might account for the different selectivity of luteolin versus different isoforms.

The inhibitory effect of luteolin on the total level of O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells was modest. This is very likely to be due to the selective inhibition of luteolin in ppGalNAc-Ts. Each ppGalNAc-T isoform has overlapping and unique substrate specificity. Despite the modest inhibition on O-GalNAc glycosylation in cells, our work paved the way for further optimization based on the scaffold of luteolin to develop selective ppGalNAc-T inhibitor. Recently, increasing evidence indicates the importance of some specific glycosylation sites on certain glycoprotein during disease progression (13, 51). O-GalNAc glycosylation is universal and important even for the normal cells. Complete abolishment of O-GalNAc glycosylation may lead to side effects on cells. Therefore, the clear selectivity of luteolin in ppGalNAc-Ts may serve as a potential candidate for further studies of the site-specific inhibition of O-GalNAc glycosylation on disease-associated glycoproteins. In that context, a modest inhibitory effect at the total level in cells will not be an obstacle for its further application.

The excess generation of Aβ is regarded as a contributor to the dysfunction and degeneration of neurons that occurs in AD (8). APP is the precursor of Aβ, and O-GalNAc glycosylation of APP is needed for its cell localization and endocytosis and plays critical roles in the Aβ production (4, 6, 7). In this study, we proved that ppGalNAc-T isoforms have different preference for glycosylation sites on APP, and luteolin selectively inhibited a set of ppGalNAc-T isoforms including ppGalNAc-T2 and T3, but not ppGalNAc-T1 and ppGalNAc-T13, both in vitro and in cells (Fig. 5). Moreover, our restoration experiments with exogenous Gal and GalNAc in CHO-ldlD cells indicated that luteolin treatment significantly inhibited O-GalNAc glycosylation on APP and then led to the reduction of Aβ in cells (Fig. 6). These findings are in line with previous reports (48, 49). Therefore, we inferred that luteolin may reduce the Aβ production at least partially by selectively inhibiting the activity of ppGalNAc-T isoforms. Because luteolin might also reduce the O-GalNAc glycosylation levels on other glycoproteins apart from APP, we cannot rule out other potential mechanisms of action for the reduction of Aβ. Actually, the sAPPα and sAPPβ were also reduced as Aβ (Fig. 6B) of HEK 293T-APP Swe cells with luteolin treatment, so we inferred that luteolin acted on APP and affected APP secretion before the activity of α-, β-, and γ-secretase. It is possible that luteolin may regulate APP transporting out of the Golgi. Further experiments were needed to settle this issue. Nevertheless, we have proved that the O-GalNAc glycosylation inhibition is an important mechanism for luteolin in modulating AD pathologies, which may also applicable for other diseases such as cancer or inflammation.

In summary, although luteolin has been reported as interacting with several targets (22–27), we for the first time show luteolin could directly inhibit ppGalNAc-Ts and reduce Aβ production by decreasing the O-GalNAc glycosylation. Our study represents a candidate scaffold structure for further optimization to develop specific ppGalNAc-T inhibitor. Considering that luteolin exhibited selectivity in ppGalNAc-T isoforms, further optimization based on this specific flavonoid may provide potent inhibitors to explore site-specific O-GalNAc glycosylation and a new avenue for developing drugs for AD and other diseases.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals and reagents

UDP-GalNAc, GalNAc, and Gal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany). EDTA and manganese chloride were from Sinopharm (Shanghai, China). EA2 and other peptides were synthesized by Scilight-Peptide (Beijing, China). Luteolin was from PI & PI Technology (Guangdong, China) in the highest purity available as powder.

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant enzymes

The putative catalytic region and lectin domain of ppGalNAc-T2 (amino acids 52–571) were amplified by high-fidelity PCR and cloned into the pFLAG-CMV-3 expression vector (Sigma) as described previously (10, 28–30). FLAG-tagged ppGalNAc-T2 was expressed in HEK 293T cells, and the recombinant enzyme was purified from the cell medium using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma). Similarly, recombinant human ppGalNAc-T1 (amino acids 34–559), T3 (amino acids 50–633), T6 (amino acids 53–622), T10 (amino acids 34–604), T13 (amino acids 40–556), and T14 (amino acids 39–552) were cloned and purified in the same way. The purity of recombinant ppGalNAc-Ts was tested by silver staining.

For the ppGalNAc-Ts used in the cellular experiments, full-length ppGalNAc-Ts were cloned into vector-pcDNA3.1 and detected with Myc antibody in the lysates (Abmart, Shanghai, China).

HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T activity assay

This assay used a FAM-labeled EA2 peptide as the substrate and was performed as described previously (30). The reaction mixture contained the following components in a final volume of 20 μl: 10 ng of ppGalNAc-T2, 100 μm EA2, 100 μm UDP-GalNAc, 0.2% Triton X-100 (v/v), 5 mm MnCl2, and 0.5 μl of DMSO or the tested compound in 25 mm HEPES buffer (the concentrations of both substrates approximate to the Km). Under these conditions, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, during which the reaction rates were linear. The reaction mixture was boiled at 95 °C for 5 min to terminate the reaction and then separated by reverse-phase HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) using the C18 analytical column (COSMOSIL 5C18-AR-II, 4.6 × 250 mm). The experiments were independently performed in triplicate, and the activity of the positive control (DMSO) was defined as 100%. In the dose dependence experiments, selected compounds were tested at the indicated concentrations, and IC50 values were obtained using GraphPad Prism version 5 software.

Similarly, the inhibitory activity of luteolin on ppGalNAc-T1, T3, T6, T10, T13, or T14 in the presence of the substrate EA2 peptide (mono-GalNAc EA2 peptide for T10 (30)) and on ppGalNAc-T2 in the presence of the peptide substrate Muc1a (FAM-AHGVTSAPDTR), Muc5AC (SAPTTSTTSAPTK-FAM), or Muc7 (PTPSATTPAPPSSSAPPETTAAK-FAM) was accordingly measured under the same conditions.

Kinetic analysis

To explore the mode of action of luteolin on ppGalNAc-T2, kinetic analysis was performed using the HPLC-based ppGalNAc-T assay described above. The reaction rate was determined with ppGalNAc-T2 at the indicated concentrations of luteolin in the presence of increasing concentrations of EA2 (0–1200 μm) with 1200 μm UDP-GalNAc or in the presence of increasing concentrations of UDP-GalNAc (0–1200 μm) with 1200 μm EA2. The data were fitted using the Michaelis–Menten equation to determine the values of Ki or αKi using GraphPad Prism version 5. To illustrate the type of inhibition (competitive, non-competitive, or mixed-type inhibition), the data were analyzed via replots of the slopes of Lineweaver–Burk plots against varying inhibitor concentrations (Fig. 2, C and D).

Purification of ppGalNAc-T2, crystallization, structure determination, and refinement

ppGalNAc-T2 was expressed in the SMD1168 Pichia pastoris strain and purified using the purification protocol described previously (33). Crystals of the ppGalNAc-T2 were grown by hanging-drop experiments at 18 °C through mixing 1 μl of protein solution (a mix formed by 7 mg/ml ppGalNAc-T2, 5 mm UDP, and 5 mm MnCl2 in 25 mm Tris, pH 8, 0.5 mm EDTA, and 1 mm tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine with an equal volume of a reservoir solution (10% PEG 8000, 6% ethylene glycol, 100 mm Hepes, pH 7). Under these conditions, crystals appeared within 2 days, and they were soaked overnight in a solution containing 7.5 mm luteolin (the final DMSO concentration was 5%), 10% PEG 8000, 6% ethylene glycol, 100 mm HEPES, pH 7. Then the crystals were cryo-protected with 25% ethylene glycol, 10% PEG 8000, 100 mm HEPES, pH 7, and frozen in a nitrogen gas stream cooled to 100 K. Processing and scaling were performed as before (33). The crystal structure was solved and refined as explained previously for identical crystals (33).

NMR experiments

NMR samples were prepared in perdeuterated 25 mm TRIS-d11 in deuterated water, 7.5 mm NaCl, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, uncorrected, pH 7.4, 50 μm UDP, 50 μm MnCl2, and 8% deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide. Luteolin was solved at 250 μm. The final concentration of the wild-type protein and mutants was 2.5 μm. Experiments were performed on a Bruker AVANCE 500-MHz spectrometer, provided with a TBO probe head, and temperature was set at 303 K. Proton spectra were recorded with solvent suppression (Bruker sequence zgesgp), the residual signal of HDO (hydrogen deuterium oxide) (4.70 ppm) was used for referencing chemical shifts (see Fig. S5), and only the aromatic region is shown. Luteolin 1H NMR (D2O, 500 MHz): δ (ppm) 6.16 (s, 1H, HA), 6.43 (s, 1H, HB), 6.56 (s, 1H, HC), 6.94–7.00 (m, 1H, HE), 7.41–7.49 (m, 2H, HD, HF). The mutants W282A and F463A were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis by GenScript and using the template pPICZαAgalnact2 (Lys75–Gln571). Both proteins were expressed and purified as the wild-type enzyme (33).

Cell culture and transfection

HEK 293T-APP Swedish mutant cells (HEK 293T-APP Swe; a generous gift from Dr. Yaer Hu) were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA), 10% FBS (Life Technologies), 1% (w/v) penicillin and streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 200 μg/ml G418 (Life Technologies) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C as described previously (54). Wild-type HEK 293T and Jurkat cells were cultured in DMEM and RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies), respectively, supplemented with 10% FBS or 1% penicillin and streptomycin. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO-K1) cells and CHO-ldlD cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 (Life Technologies).

Plasmids containing human ppGalNAc-T1, T2, T3, or T13 or FLAG-tagged wild-type APP695 (FLAG-tagged APP) were transfected into HEK 293T cells using X-treme GENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Evaluation of the activity of ppGalNAc-T in cells by using click chemistry to capture GalNAz-labeled proteins

CHO-ldlD cells were incubated with 100 μm Ac4GalNAz (Thermo) for 12 h before treatment with the indicated concentrations of luteolin for another 36 h. After the incubation, cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton X-100, and the extracted proteins were quantified by a BCA protein assay (Pierce). 1 mg of cell lysate was mixed with 20 μm biotin alkyne (Invitrogen) and a mixture of catalysts in PBS (pH 7.5) and rotated for 3 h at 25 °C. The ingredients of catalyst were 0.5 mm tert-butyl-2,2,2-trichloroacetimidate (Sigma), 2 mm l-ascorbic acid sodium salt (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Inc.), and 1 mm CuSO4·5H2O (Sigma). Biotin-labeled proteins were then subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and blotted with strepavidin (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Western blot and immunoprecipitation (IP)

Cells were collected and lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton X-100 or 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, and 1× protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The extracted proteins were quantified by a BCA protein assay (Pierce). Equal amounts of protein were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to membranes (GE Healthcare), and blotted with the indicated antibodies: anti-APP C terminus antibody (C-T15, Sigma), anti-FLAG antibody against FLAG-tagged APP or PDPN (Sigma), anti-Myc antibody against Myc-tagged ppGalNAc-Ts (Abmart), anti-ppGalNAc-T2 antibody (Sigma), and anti-β-actin antibody or α-tubulin antibody (Sigma).

The immunoprecipitation of FLAG-tagged and endogenous APP was performed by incubating 1 mg of total protein with anti-FLAG affinity resin (Sigma) or C-T15 (Sigma), respectively, at 4 °C overnight. The C-T15–bound proteins were immunoprecipitated for 3 h at 4 °C using Protein A–agarose beads (Roche Applied Science). The agarose beads were then washed three times with TBS, and the bound proteins were eluted with 2× Laemmli buffer. The resuspended proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis.

Lectin blot

The cell lysates were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to cellulose acetate membranes (GE Healthcare). The membranes were washed with PBS containing 1% Tween 20 at room temperature before incubation with the Jacalin (primarily recognizing O-GalNAc glycans) and concanavalin A (ConA; primarily recognizing N-glycans) lectin conjugated with HRP (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in 0.1% Tween 20–PBS buffer at 4 °C overnight. The blots were visualized by ECL (Pierce).

Fluorescence imaging

After incubation with DMSO or luteolin at the indicated concentrations, Jurkat cells were collected and fixed on coverslips using Cytospin (Thermo, San Jose, CA). The fixed cells were treated with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China) for 30 min at room temperature, washed with PBS, blocked with 5% BSA (Sangon Biotech) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and incubated with HPA (primarily recognizing O-GalNAc glycans) and ConA lectin conjugated with FITC (Vector Laboratories) at 4 °C overnight. The cells were then incubated with 0.5 ml of DAPI (1.25 μg/ml) for 3 min and washed three times in PBS before acquiring images using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

OGT activity assay with HPLC

OGT was expressed in E. coli and purified by nickel affinity chromatography and gel filtration as in previous methods (40, 41). The reaction mixtures containing 200 μm CKII peptide (KKKYPGGSTPVSSANMM), 100 nm ncOGT, 12.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm UDP-GlcNAc, buffer (150 mm NaCl, 20 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm tris(hydroxypropyl)phosphine, pH 7.4) and the indicated concentrations of luteolin were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. After quenching by the addition of an equal volume of methanol, the reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatants (40 μl) were loaded onto an Agilent 1260 Infinity HPLC system to quantify the yield based on the integrated areas of glycopeptide product and peptide substrate. The reverse-phase chromatographic column was a Zorbax SB-C18 stable bond analytical column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm; Agilent), preceded by a Zorbax SB-C18 analytical guard column (4.6 mm × 12.5 mm, 5 μm; Agilent). Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% TFA in H2O, and mobile phase B consisted of 0.1% TFA in MeCN. The components were eluted using a gradient (flow rate at 1 ml/min; at 0 min elution solvent mixture A/B = 90/10; at 20 min elution solvent mixture A/B = 70/30; wavelength = 214 nm). Each reaction was repeated three times.

Dynamic light scattering

Particle formation was measured using a particle size analyzer (Z90s, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK). Aggregator (50–1000 nm) sizes were measured in 25 mm HEPES buffer with different concentrations of Triton X-100 (v/v). Experiments were repeated three times, and each histogram shows a single representative sample.

Aβ, sAPPα, and sAPPβ ELISA

For HEK 293T, HEK 293T-APP Swe, CHO-K1, CHO-ldlD, and other cells expressing exogenous APP or not, the corresponding cell medium or lysates were then harvested, and Aβ was quantified using human amyloid assay kits for Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ 1-x (IBL, Gumma, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocols. sAPPα and sAPPβ were tested using a human sAPPα and sAPPβ kit (ExCell Bio, Shanghai, China) according to the protocols.

Mice

APP/PS1 transgenic mice (a total of 10, male) were obtained from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University (B6C3-Tg (APPswe, PSEN1dE9)85Dbo/MmJNju). All of the experiments were performed according to the guidelines established by the ethics committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The mice were housed two or three per cage with free access to water and food in a temperature-controlled room and under natural lighting conditions with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00). Mice were intraperitoneally injected with luteolin (50 mg/kg/day) or PBS from 4 to 6 months of age, a period in which Aβ has substantially emerged. The mice were then sacrificed, and the obtained brain homogenates of each mouse was extracted with 1% Triton X-100 and analyzed for APP by immunoprecipitation (anti-C-T15 antibody) and for total Aβ, Aβ40, and Aβ42 by ELISA.

Statistical analysis and Western blot quantification

All experiments were performed at least twice in duplicate or triplicate with comparable results; the data are presented as the mean ± S.D. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple-comparison tests or two-tailed Student's t test; statistical significance is indicated as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. The density of the bands was obtained in the linear range by choosing the suitable exposure time and followed by quantification by using ImageJ (Rawak Software, Inc.).

Author contributions

Y. Z., F. W., and R. H.-G. conceived the idea and supervised the study; F. L., K. X., Z. X., M. R., C. W., X. L., I. D., and Y. Y. Z. performed the experiments; F. L., K. X., P. M., F. W., R. H.-G., and Y. Z. analyzed the experimental data; F. L., J. L., F. W., R. H.-G., and Y. Z. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Sullivan, Jun Liu, and Curtis Chong (Johns Hopkins University) for providing the Johns Hopkins Clinical Compound Library and Dr. Yaer Hu (School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University) for providing HEK 293-APP Swe cells. We thank Dr. Xuedong Liu (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO) for helpful discussion.

Note added in proof

Congrong Wang, Yueyang Zhou, and Fang Wu were inadvertently omitted as authors in the version of this paper that was published as a Paper in Press on October 23, 2017. This error has now been corrected.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China Grants 2012CB822103 and 2011CB910603 (to Y. Z.); National High Technology Research and Development Program of China Grant 2012AA020203 (to Y. Z.); National Natural Science Foundation Grants 31170771 (to Y. Z.), 31370806 (to Y. Z.), and 31570796 (to Y. Z.); National Basic Research Program of China Grant 2012CB822103 (to F. W.); National Natural Science Foundation Grants 31270853 and 81102377 (to F. W.); Agencia Aragonesa para la Investigación y Desarrollo (ARAID), Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, Grants CTQ2013-44367-C2-2-P and BFU2016-75633-P (to R. H.-G.); Diputación General de Aragón (DGA) Grant B89 (to R. H.-G.); and the EU Seventh Framework Programme (2007–2013) under BioStruct-X (Grant Agreement 283570 and BIOSTRUCTX 5186) (to R. H.-G.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Table S1 and Figs. S1–S5.

- GalNAc

- α-N-acetylgalactosamine

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- Aβ

- amyloid β

- Gal

- galactose

- ppGalNAc-T

- polypeptide N-acetyl-α-galactosaminyltransferase

- PDPN

- podoplanin

- HPA

- H. pomatia agglutinin

- ConA

- concanavalin A

- APP-H

- high-molecular weight band of APP

- DLS

- dynamic light scattering

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- AU

- asymmetric unit

- FAM

- fluorescein amidite

- GalNAz

- N-azido-acetylgalactosamine.

References

- 1. Kathiresan S., Melander O., Guiducci C., Surti A., Burtt N. P., Rieder M. J., Cooper G. M., Roos C., Voight B. F., Havulinna A. S., Wahlstrand B., Hedner T., Corella D., Tai E. S., Ordovas J. M., et al. (2008) Six new loci associated with blood low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol or triglycerides in humans. Nat. Genet. 40, 189–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kato K., Jeanneau C., Tarp M. A., Benet-Pagès A., Lorenz-Depiereux B., Bennett E. P., Mandel U., Strom T. M., and Clausen H. (2006) Polypeptide GalNAc-transferase T3 and familial tumoral calcinosis: secretion of fibroblast growth factor 23 requires O-glycosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18370–18377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Halim A., Brinkmalm G., Rüetschi U., Westman-Brinkmalm A., Portelius E., Zetterberg H., Blennow K., Larson G., and Nilsson J. (2011) Site-specific characterization of threonine, serine, and tyrosine glycosylations of amyloid precursor protein/amyloid beta-peptides in human cerebrospinal fluid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11848–11853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schedin-Weiss S., Winblad B., and Tjernberg L. O. (2014) The role of protein glycosylation in Alzheimer disease. FEBS J. 281, 46–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weidemann A., König G., Bunke D., Fischer P., Salbaum J. M., Masters C. L., and Beyreuther K. (1989) Identification, biogenesis, and localization of precursors of Alzheimer's disease A4 amyloid protein. Cell 57, 115–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tomita S., Kirino Y., and Suzuki T. (1998) Cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein (APP) by secretases occurs after O-glycosylation of APP in the protein secretory pathway: identification of intracellular compartments in which APP cleavage occurs without using toxic agents that interfere with protein metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6277–6284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kitazume S., Tachida Y., Kato M., Yamaguchi Y., Honda T., Hashimoto Y., Wada Y., Saito T., Iwata N., Saido T., and Taniguchi N. (2010) Brain endothelial cells produce amyloid β from amyloid precursor protein 770 and preferentially secrete the O-glycosylated form. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40097–40103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Glenner G. G., Wong C. W., Quaranta V., and Eanes E. D. (1984) The amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease: their nature and pathogenesis. Appl. Pathol. 2, 357–369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennett E. P., Mandel U., Clausen H., Gerken T. A., Fritz T. A., and Tabak L. A. (2012) Control of mucin-type O-glycosylation: a classification of the polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Glycobiology 22, 736–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peng C., Togayachi A., Kwon Y. D., Xie C., Wu G., Zou X., Sato T., Ito H., Tachibana K., Kubota T., Noce T., Narimatsu H., and Zhang Y. (2010) Identification of a novel human UDP-GalNAc transferase with unique catalytic activity and expression profile. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 402, 680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerken T. A., Jamison O., Perrine C. L., Collette J. C., Moinova H., Ravi L., Markowitz S. D., Shen W., Patel H., and Tabak L. A. (2011) Emerging paradigms for the initiation of mucin-type protein O-glycosylation by the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family of glycosyltransferases. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 14493–14507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kong Y., Joshi H. J., Schjoldager K. T., Madsen T. D., Gerken T. A., Vester-Christensen M. B., Wandall H. H., Bennett E. P., Levery S. B., Vakhrushev S. Y., and Clausen H. (2015) Probing polypeptide GalNAc-transferase isoform substrate specificities by in vitro analysis. Glycobiology 25, 55–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schjoldager K. T., Joshi H. J., Kong Y., Goth C. K., King S. L., Wandall H. H., Bennett E. P., Vakhrushev S. Y., and Clausen H. (2015) Deconstruction of O-glycosylation–GalNAc-T isoforms direct distinct subsets of the O-glycoproteome. EMBO Rep. 16, 1713–1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schjoldager K. T., and Clausen H. (2012) Site-specific protein O-glycosylation modulates proprotein processing: deciphering specific functions of the large polypeptide GalNAc-transferase gene family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 2079–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schjoldager K. T., Vester-Christensen M. B., Bennett E. P., Levery S. B., Schwientek T., Yin W., Blixt O., and Clausen H. (2010) O-Glycosylation modulates proprotein convertase activation of angiopoietin-like protein 3: possible role of polypeptide GalNAc-transferase-2 in regulation of concentrations of plasma lipids. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36293–36303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Agarwal K., Kaul R., Garg M., Shajahan A., Jha S. K., and Sampathkumar S. G. (2013) Inhibition of mucin-type O-glycosylation through metabolic processing and incorporation of N-thioglycolyl-d-galactosamine peracetate (Ac5GalNTGc). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14189–14197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Song L., and Linstedt A. (2017) Inhibitor of ppGalNAc-T3-mediated O-glycosylation blocks cancer cell invasiveness and lowers FGF23 levels. Elife 6, e24051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hang H. C., Yu C., Ten Hagen K. G., Tian E., Winans K. A., Tabak L. A., and Bertozzi C. R. (2004) Small molecule inhibitors of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation from a uridine-based library. Chem. Biol. 11, 337–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghirardello M., de Las Rivas M., Lacetera A., Delso I., Lira-Navarrete E., Tejero T., Martín-Santamaría S., Hurtado-Guerrero R., and Merino P. (2016) Glycomimetics targeting glycosyltransferases: synthetic, computational and structural studies of less-polar conjugates. Chemistry 22, 7215–7224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Joel Mjiqiza S., Abraham Syce J., and Chibuzo Obikeze K. (2013) Pulmonary effects and disposition of luteolin and Artemisia afra extracts in isolated perfused lungs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 149, 648–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang S., Ruan J., Zhuang J., and Jiang Q. (2000) The effect of Xiaofu Oral liquid on anti-inflammation, sedation and acute toxicity test. Strait Pharmaceutical J. 12, 23–25 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Puhl A. C., Bernardes A., Silveira R. L., Yuan J., Campos J. L., Saidemberg D. M., Palma M. S., Cvoro A., Ayers S. D., Webb P., Reinach P. S., Skaf M. S., and Polikarpov I. (2012) Mode of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation by luteolin. Mol. Pharmacol. 81, 788–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trivella D. B., dos Reis C. V., Lima L. M., Foguel D., and Polikarpov I. (2012) Flavonoid interactions with human transthyretin: combined structural and thermodynamic analysis. J. Struct. Biol. 180, 143–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yokoyama T., Kosaka Y., and Mizuguchi M. (2015) Structural insight into the interactions between death-associated protein kinase 1 and natural flavonoids. J. Med. Chem. 58, 7400–7408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Narwal M., Haikarainen T., Fallarero A., Vuorela P. M., and Lehtiö L. (2013) Screening and structural analysis of flavones inhibiting tankyrases. J. Med. Chem. 56, 3507–3517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lolli G., Cozza G., Mazzorana M., Tibaldi E., Cesaro L., Donella-Deana A., Meggio F., Venerando A., Franchin C., Sarno S., Battistutta R., and Pinna L. A. (2012) Inhibition of protein kinase CK2 by flavonoids and tyrphostins: a structural insight. Biochemistry 51, 6097–6107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iakovleva I., Begum A., Pokrzywa M., Walfridsson M., Sauer-Eriksson A. E., and Olofsson A. (2015) The flavonoid luteolin, but not luteolin-7-O-glucoside, prevents a transthyretin mediated toxic response. PLoS One 10, e0128222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang Y., Iwasaki H., Wang H., Kudo T., Kalka T. B., Hennet T., Kubota T., Cheng L., Inaba N., Gotoh M., Togayachi A., Guo J., Hisatomi H., Nakajima K., Nishihara S., et al. (2003) Cloning and characterization of a new human UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase, designated pp-GalNAc-T13, that is specifically expressed in neurons and synthesizes GalNAc α-serine/threonine antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 573–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu Y., Pang W., Lu J., Shan A., and Zhang Y. (2016) Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 13 contributes to neurogenesis via stabilizing the mucin-type O-glycoprotein podoplanin. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 23477–23488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li X., Wang J., Li W., Xu Y., Shao D., Xie Y., Xie W., Kubota T., Narimatsu H., and Zhang Y. (2012) Characterization of ppGalNAc-T18, a member of the vertebrate-specific Y subfamily of UDP-N-acetyl-α-d-galactosamine:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferases. Glycobiology 22, 602–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fritz T. A., Raman J., and Tabak L. A. (2006) Dynamic association between the catalytic and lectin domains of human UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide α-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8613–8619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lira-Navarrete E., de Las Rivas M., Compañón I., Pallarés M. C., Kong Y., Iglesias-Fernández J., Bernardes G. J., Peregrina J. M., Rovira C., Bernadó P., Bruscolini P., Clausen H., Lostao A., Corzana F., and Hurtado-Guerrero R. (2015) Dynamic interplay between catalytic and lectin domains of GalNAc-transferases modulates protein O-glycosylation. Nat. Commun. 6, 6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lira-Navarrete E., Iglesias-Fernández J., Zandberg W. F., Compañón I., Kong Y., Corzana F., Pinto B. M., Clausen H., Peregrina J. M., Vocadlo D. J., Rovira C., and Hurtado-Guerrero R. (2014) Substrate-guided front-face reaction revealed by combined structural snapshots and metadynamics for the polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 53, 8206–8210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kingsley D. M., Kozarsky K. F., Hobbie L., and Krieger M. (1986) Reversible defects in O-linked glycosylation and LDL receptor expression in a UDP-Gal/UDP-GalNAc 4-epimerase deficient mutant. Cell 44, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Slade P. G., Hajivandi M., Bartel C. M., and Gorfien S. F. (2012) Identifying the CHO secretome using mucin-type O-linked glycosylation and click-chemistry. J. Proteome Res. 11, 6175–6186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaneko M. K., Kato Y., Kameyama A., Ito H., Kuno A., Hirabayashi J., Kubota T., Amano K., Chiba Y., Hasegawa Y., Sasagawa I., Mishima K., and Narimatsu H. (2007) Functional glycosylation of human podoplanin: glycan structure of platelet aggregation-inducing factor. FEBS Lett. 581, 331–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pan Y., Yago T., Fu J., Herzog B., McDaniel J. M., Mehta-D'Souza P., Cai X., Ruan C., McEver R. P., West C., Dai K., Chen H., and Xia L. (2014) Podoplanin requires sialylated O-glycans for stable expression on lymphatic endothelial cells and for interaction with platelets. Blood 124, 3656–3665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pohjala L., and Tammela P. (2012) Aggregating behavior of phenolic compounds–a source of false bioassay results? Molecules 17, 10774–10790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y., Zhu J., and Zhang L. (2017) Discovery of cell-permeable O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors via tethering in situ click chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 60, 263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lazarus M. B., Nam Y., Jiang J., Sliz P., and Walker S. (2011) Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature 469, 564–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kreppel L. K., Blomberg M. A., and Hart G. W. (1997) Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins: cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9308–9315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Revoredo L., Wang S., Bennett E. P., Clausen H., Moremen K. W., Jarvis D. L., Ten Hagen K. G., Tabak L. A., and Gerken T. A. (2016) Mucin-type O-glycosylation is controlled by short- and long-range glycopeptide substrate recognition that varies among members of the polypeptide GalNAc transferase family. Glycobiology 26, 360–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sarrazin M., Sari J. C., Bourdeaux-Pontier M., and Briand C. (1979) NMR study of the interactions between flurazepam and human serum albumin. The nature of the complexation site on the benzodiazepin molecule. Mol. Pharmacol. 15, 71–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fischer J. J., and Jardetzky O. (1965) Nuclear magnetic relaxation study of intermolecular complexes: the mechanism of penicillin binding to serum albumin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87, 3237–3244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fielding L. (2003) NMR methods for the determination of protein-ligand dissociation constants. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3, 39–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Singh M., Kaur M., and Silakari O. (2014) Flavones: an important scaffold for medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 84, 206–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cai W., Chen Y., Xie L., Zhang H., and Hou C. (2014) Characterization and density functional theory study of the antioxidant activity of quercetin and its sugar-containing analogues. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 238, 121–128 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rezai-Zadeh K., Douglas Shytle R., Bai Y., Tian J., Hou H., Mori T., Zeng J., Obregon D., Town T., and Tan J. (2009) Flavonoid-mediated presenilin-1 phosphorylation reduces Alzheimer's disease β-amyloid production. J. Cell Mol. Med. 13, 574–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Theoharides T. C., Stewart J. M., Hatziagelaki E., and Kolaitis G. (2015) Brain “fog,” inflammation and obesity: key aspects of neuropsychiatric disorders improved by luteolin. Front. Neurosci. 9, 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Perdivara I., Petrovich R., Allinquant B., Deterding L. J., Tomer K. B., and Przybylski M. (2009) Elucidation of O-glycosylation structures of the beta-amyloid precursor protein by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry using electron transfer dissociation and collision induced dissociation. J. Proteome Res. 8, 631–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Steentoft C., Vakhrushev S. Y., Joshi H. J., Kong Y., Vester-Christensen M. B., Schjoldager K. T., Lavrsen K., Dabelsteen S., Pedersen N. B., Marcos-Silva L., Gupta R., Bennett E. P., Mandel U., Brunak S., Wandall H. H., et al. (2013) Precision mapping of the human O-GalNAc glycoproteome through SimpleCell technology. EMBO J. 32, 1478–1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schjoldager K. T., Vakhrushev S. Y., Kong Y., Steentoft C., Nudelman A. S., Pedersen N. B., Wandall H. H., Mandel U., Bennett E. P., Levery S. B., and Clausen H. (2012) Probing isoform-specific functions of polypeptide GalNAc-transferases using zinc finger nuclease glycoengineered SimpleCells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 9893–9898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sugiura M., Kawasaki T., and Yamashina I. (1982) Purification and characterization of UDP-GalNAc:polypeptide N-acetylgalactosamine transferase from an ascites hepatoma, AH 66. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 9501–9507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haass C., Capell A., Citron M., Teplow D. B., and Selkoe D. J. (1995) The vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 differentially affects proteolytic processing of mutant and wild-type β-amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6186–6192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.