Abstract

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is an inherited form of gastric cancer that carries a poor prognosis. Most HDGCs are caused by an autosomal dominant genetic mutation in the CDH1 gene, which carries a 70%-80% lifetime risk of gastric cancer. Given its submucosal origin, endoscopic surveillance is an unreliable means of early detection, and prophylactic gastrectomy is recommended for CDH1 positive individuals older than age 20 years. We describe the case of a male with recurrent gastric cancer who was diagnosed with HDGC secondary to the CDH1 mutation, and we also describe the patient’s pedigree and outcomes of recommended genetic testing.

Keywords: Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, Genetic testing, Genetic diseases, Gastric cancer, Lobular breast cancer, Inheritable diseases

Core tip: Individuals who carry the CDH1 gene mutation are at very high risk of acquiring hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, a cancer with a high mortality if not detected early. The clinical findings we describe in this case may aid medical practitioners in the assessment and testing of patients with a family history of gastric cancer and raise awareness about the importance of genetic testing for this condition.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer related death worldwide[1]. While most gastric cancers occur from sporadic mutations, inherited gastric cancers make up 1%-3% of cases and are referred to as Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancers (HDGC)[2]. The majority of HDGCs are caused by an autosomal dominant inheritance of an abnormal copy of the tumor suppressor gene CDH1. As the CDH1 gene has a high penetrance, mutations produce a multi-generational cancer syndrome that affects multiple organs[2]. The CDH1 gene mutation causes a 70%-80% life time risk of gastric cancer in both men and women and a 40%-60% life time risk of lobular breast cancer[2,3]. Unfortunately, detection based on gastrointestinal symptoms and endoscopic surveillance has a poor prognosis. Therefore, the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium (IGCLC) recommends prophylactic gastrectomy in individuals with the CDH1 gene mutation between ages 20 to 30[2]. It is therefore imperative that patients with a family history of gastric cancer have a comprehensive family pedigree reviewed and undergo genetic testing for the presence of HDGC if they fit the criteria proposed by the IGCLC.

In this report, we describe the case of a Caucasian male who was found to have the CDH1 gene mutation and diagnosed with HDGC. We also describe the results of his family members’ genetic testing.

CASE REPORT

At age 49, the patient presented with abdominal fullness and was found to have gastric signet ring adenocarcinoma, and was treated with a partial gastrectomy (Billroth II). The patient had no evidence of metastatic disease at this time as evidenced by normal CT scans. The patient subsequently underwent triennial esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) for surveillance of cancer recurrence. In 2012, at the age of 58, a surveillance EGD was performed with random biopsies taken from normal appearing mucosa in the gastric cardia, fundus, distal body, and anastomosis site. Only the biopsy from the distal gastric body revealed adenocarcinoma with signet cells; all other biopsy specimens were negative for cancer related pathology. Endoscopic ultrasound was performed and did not reveal any submucosal or mucosal aberrations. PET/CT showed no areas of increased activity suggestive of metastatic disease.

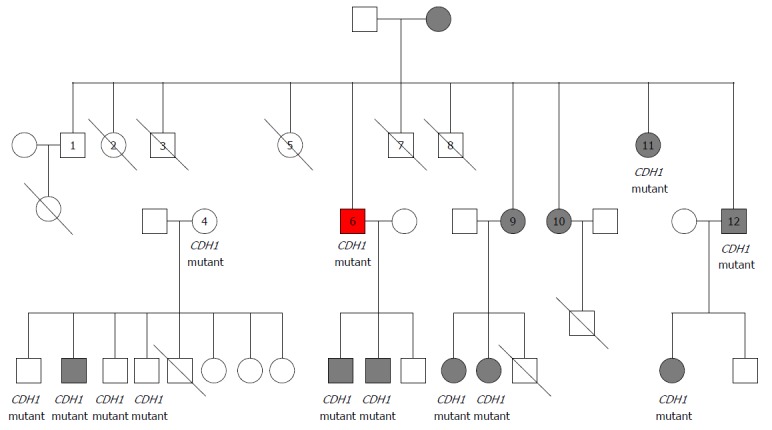

Family history revealed that the patient’s mother was diagnosed with gastric cancer at age 59, when the patient was 17, and subsequently died from metastatic disease (Figure 1). The patient’s identical twin sisters were both diagnosed with gastric cancer at age 38, and died shortly thereafter.

Figure 1.

Family pedigree. Shading indicates presence of diagnosed HDGC. Strike through represents negative testing for the CDH1 gene mutation. Red square represents our patient.

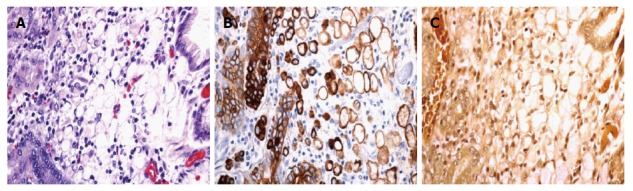

The patient underwent total gastrectomy, with lymph node sampling. The pathologic specimen showed a 0.6-cm tumor in the lesser curvature of the stomach with invasion into the lamina propria. Histologic analysis showed a poorly differentiated signet ring cell carcinoma (Figure 2), grade 3. Immunohistochemical stains for mucicarmine and keratin AE1/AE3 highlighted the signet ring cell carcinoma. No additional staining was performed. All 16 sampled lymph nodes were negative for pathology, and staging was deemed T1a.

Figure 2.

Histology of the gastric lamina propria showing signet ring cells. A: HE stain (× 200); B: Cytokeratin AE1.3 antibody staining showing the presence of keratin (× 200); C: Mucicarmine stain showing the presence of mucin (× 200).

The patient underwent a gene panel for known mutations linked to gastrointestinal cancers. The DNA sampled was from the patient’s lymphocytes and next-generation sequencing was used. The patient tested positive for the CDH1 gene with aberration in the c.521 dvpA and the STKII gene had a mutation of unknown significance with aberration in p.5354L. Testing for lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome were negative. Given the defined mutation, and with the patient’s encouragement, many of the patient’s family members underwent genetic testing.

The patient’s pedigree is shown in Figure 1. In total, 21 of the patient’s relatives underwent genetic testing, of which 12 were found to have the CDH1 gene mutation, including two of the patient’s sons. Of these 12 relatives, 8 underwent prophylactic gastrectomy, despite having no concerning gastrointestinal symptoms. At the time of gastrectomy all 8 family members had evidence of gastric cancer when pathological specimens were histologically analyzed.

DISCUSSION

HDGC, unlike the sporadic forms of gastric cancer, is composed of signet ring cells and originates diffusely throughout the gastric submucosa[4-6]. The sporadic form of gastric cancer is usually associated with Helicobacter pylori infection, which can lead to gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia[4,5,7,8]. Often with Helicobacter pylori associated gastric cancer, cells are arranged in a gland-like formation and begin in the mucosa[4,5,7,8]. As occurred in this case, the cancer found in HDGC related cases is usually poorly differentiated, which is a direct result of the CDH1 gene mutation. The CDH1 gene, located on chromosome 16, codes for E-cadherin, a calcium dependent cellular adhesion protein that is instrumental in maintaining epithelial cell structural integrity[2,5,6]. When this gene is mutated, the decreased E-cadherin expression promotes atypical cellular architecture and irregular cell growth, ultimately leading to cancer development[2,5,6].

The mutation in the CDH1 gene can occur sporadically or can be inherited through an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. The CDH1 gene is a tumor suppressor gene and thereby requires a second hit, a somatic mutation in the second E-cadherin allele, in order to cause cancer progression. In individuals with germline mutations of CDH1, the second hit has been shown to occur mostly through CDH1 promoter hypermethylation, with fewer instances of loss of heterozygosity[9,10]. One study found that no additional somatic mutations beyond promoter hypermethylation in those with germline CDH1 mutations were required for cancer formation[9].

Because HDGC originates as discrete foci in the gastric submucosa, it produces no grossly visible architectural changes[2,6]. The presence of cancer as a result is hidden in its early stages on endoscopy and nearly impossible to detect with sampling by random biopsies[2,6]. Currently there is a lack of evidence regarding the timing of metastatic signet ring gastric carcinoma, though evidence suggests that there may be a dormant period before metastasis[11,12]. The progression of diffuse gastric cancer seems to be particularly aggressive in young individuals, as only 10% of those under age 40 who develop symptomatic and invasive diffuse gastric cancer have curable disease[12,13]. Thus the IGCLC recommends that individuals with the CDH1 gene mutation, even without evidence of gastric cancer, undergo prophylactic total gastrectomy between ages 20 to 30 years, rather than surveillance endoscopy[2] (Table 1). If a person is unwilling to undergo prophylactic gastrectomy, the IGCLC recommends intensive endoscopic surveillance at an expert center[2]. Other means of early cancer detection have also been met with limited success; PET imaging has a high rate of false negatives in mucinous cancers, such as occurs in HDGC[14].

Table 1.

CDH1 related cancer risks and International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium 8th workshop management recommendations

| Gastric cancer | Lobular breast cancer | Colon cancer | |

| Lifetime cancer risk | 80% | 60% | Unknown |

| Surveillance | EGD surveillance in persons not willing to undergo prophylactic gastrectomy | Annual clinical breast exams | Colon cancer screening in HDGC families with colon cancer from age 40 or 10 yr younger than the youngest diagnosis of colon cancer |

| If CDH1 + with no evidence of cancer, EGD surveillance, usually starting at age 16 until time of prophylactic gastrectomy per IGCLC 7 guideline[11] | Bilateral breast MRI starting at age 30 | Repeat colonoscopy at 3-5 yr intervals per IGCLC 7 guidelines[11] | |

| Therapy | Suggest prophylactic gastrectomy between age 20-30 if CDH1 + without evidence of cancer Suggests gastrectomy if evidence of cancer regardless of age | Prophylactic mastectomy not recommended, but may be considered on case by case basis | Not available |

EGD: Esophagogastroduodenoscopies; HDGC: Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer; IGCLC: International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium.

Given the low yield of random biopies and the negative PET scan, our patient was highly fortunate that the random biopsy taken in the distal gastric body revealed the presence of cancer. This is especially lucky given the patient’s intact gastric mucosal appearance on endoscopy and the normal biopsies taken in the other gastric locations. At the time of gastrectomy, our patient’s cancer was staged a T1. Thus, our patient’s cancer was effectively caught early, before it metastasized. Furthermore, the 70%-80% penetrance[2] of the CDH1 mutation coupled with the patient’s diagnosis of gastric cancer 10 years prior and the death of 3 family members due to metastatic gastric carcinoma, suggest that the patient’s cancer would have ultimately progressed if it had been left undetected.

Due to the difficulty in early detection, the high penetrance of the CDH1 gene, and the early onset of incurable disease, genetic testing is the only beneficial means of detecting and preventing HDGC in individuals with a family history. The IGCLC therefore recommends CDH1 genetic testing in all individuals who meet one of the following criteria: 2 or more cases of gastric cancer in a family with 1 confirmed diffuse type in 1st or 2nd degree relatives independent of age, presence of diffuse gastric cancer in an individual less than age 50, and personal or family history of diffuse gastric cancer and lobular breast cancer with one of the diagnoses before age 50[2]. Genetic testing may also be considered in individuals with bilateral lobular breast cancer under the age of 50 or in families with multiple members with lobular breast cancer (with two of these relatives younger than 50 years)[2]. As the CDH1 gene mutation has also been linked to cleft lip and palate, the IGCLC suggests that genetic testing may be considered in families with a history of cleft lip/palate and diffuse gastric cancer[2].

Given the risk of lobular breast cancer, the IGCLC recommends breast screening from age 30 (composed of annual clinical breast exams and bilateral MRIs)[2]. The IGCLC does not recommend prophylactic mastectomy in individuals with the CDH1 mutation, though suggests that mastectomy can be considered on a case by case basis[2]. Colon cancer screening is recommended only in families with HDGC related colon cancer starting at age 40 or 10 years younger than the affected individual[2].

At the time of initial diagnosis of gastric cancer, our patient had 3 first-degree relatives who had already succumbed to metastatic disease. However, these 3 relatives died prior to the discovery of the CDH1 gene mutation in 1998[15] and were thus unable to undergo genetic testing. While our patient was initially diagnosed with gastric cancer in 2003, the expense of genetic testing and the lack of availability of genetic testing in office based medical practices precluded our patient from undergoing gene analysis. By the time of our patient’s cancer recurrence in 2012, the widespread availability of genetic testing allowed our patient to undergo screening and also encourage screening in his family members. By doing so, the patient prompted life saving measures in his family: the CDH1 gene mutation was detected in 12 relatives and evidence of histological gastric cancer was detected in 8 relatives who underwent prophylactic gastrectomy. This case highlights the importance of gathering a thorough family history, especially as it relates to gastric cancer, and encouraging genetic testing in patients who meet the IGCLC criteria. This case also emphasizes the benefit of affordable and available genetic testing and the need to make genetic testing available for office based practices.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Case characteristics

A 58-year-old male with a past medical history of gastric signet ring adenocarcinoma, treated with partial gastrectomy, presenting to our practice for triennial esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGD) for surveillance of cancer recurrence. Patient’s family history was significant for 3 first degree relatives with gastric cancer. EGD performed showed normal appearing mucosa, though biopsy from the distal gastric body revealed adenocarcinoma with signet cells.

Clinical diagnosis

Patient was asymptomatic at diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis included spontaneous gastric cancer reoccurrence or a hereditary gastric cancer syndrome.

Laboratory diagnosis

The patient underwent a gene panel for known mutations linked to gastrointestinal cancers. The patient tested positive for a mutation in the CDH1 gene which confirmed the presence of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.

Imaging diagnosis

Endoscopic ultrasound revealed no submucosal or mucosal aberrations. PET/CT imaging revealed no abnormalities suggestive of metastatic disease.

Pathological diagnosis

Examination of the pathologic specimen after total gastrectomy, confirmed a 0.6-cm poorly differentiated signet ring cell carcinoma in the lesser curvature of the stomach with invasion into the lamina propria.

Treatment

The patient underwent total gastrectomy. The patient encouraged genetic testing in his 21 family members, of which 12 were found to have the CDH1 gene mutation.

Related reports

There are currently other case reports of families with the CDH1 gene mutation, though none with as extensive a family pedigree.

Term explanation

HDGC is an inherited form of gastric cancer, with majority caused by an autosomal dominant genetic mutation in the CDH1 gene.

Experiences and lessons

This case highlights the importance of gathering a thorough family history, especially as it relates to gastric cancer, and encouraging genetic testing in patients who meet the International Gastric Cancer Linkage Consortium criteria.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient by the article guarantor.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and nothing to declare.

Peer-review started: November 9, 2017

First decision: November 30, 2017

Article in press: December 13, 2017

P- Reviewer: Economescu MCC, Tanabe S S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

Contributor Information

Haley M Zylberberg, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY 11549, United States.

Keith Sultan, Division of Gastroenterology, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Manhasset, NY 11030, United States.

Steven Rubin, Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY 11549, United States; Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Merrick, NY 11566, United States.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan 2012. Accessed October 13. 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx.

- 2.van der Post RS, Vogelaar IP, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Huntsman D, Hoogerbrugge N, Caldas C, Schreiber KE, Hardwick RH, Ausems MG, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated clinical guidelines with an emphasis on germline CDH1 mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 2015;52:361–374. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch HT, Kaurah P, Wirtzfeld D, Rubinstein WS, Weissman S, Lynch JF, Grady W, Wiyrick S, Senz J, Huntsman DG. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: diagnosis, genetic counseling, and prophylactic total gastrectomy. Cancer. 2008;112:2655–2663. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah MA, Khanin R, Tang L, Janjigian YY, Klimstra DS, Gerdes H, Kelsen DP. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: a new paradigm. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2693–2701. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Woude CJ, Kleibeuker JH, Tiebosch AT, Homan M, Beuving A, Jansen PL, Moshage H. Diffuse and intestinal type gastric carcinomas differ in their expression of apoptosis related proteins. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:699–702. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.9.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onitilo AA, Aryal G, Engel JM. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: a family diagnosis and treatment. Clin Med Res. 2013;11:36–41. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2012.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418–1424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Cutsem E, Sagaert X, Topal B, Haustermans K, Prenen H. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:2654–2664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30354-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grady WM, Willis J, Guilford PJ, Dunbier AK, Toro TT, Lynch H, Wiesner G, Ferguson K, Eng C, Park JG, et al. Methylation of the CDH1 promoter as the second genetic hit in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2000;26:16–17. doi: 10.1038/79120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Machado JC, Oliveira C, Carvalho R, Soares P, Berx G, Caldas C, Seruca R, Carneiro F, Sobrinho-Simöes M. E-cadherin gene (CDH1) promoter methylation as the second hit in sporadic diffuse gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 2001;20:1525–1528. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald RC, Hardwick R, Huntsman D, Carneiro F, Guilford P, Blair V, Chung DC, Norton J, Ragunath K, Van Krieken JH, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet. 2010;47:436–444. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.074237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber M, Murrell A, Ito Y, Maia AT, Hyland S, Oliveira C, Save V, Carneiro F, Paterson AL, Grehan N, et al. Mechanisms and sequelae of E-cadherin silencing in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. J Pathol. 2008;216:295–306. doi: 10.1002/path.2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koea JB, Karpeh MS, Brennan MF. Gastric cancer in young patients: demographic, clinicopathological, and prognostic factors in 92 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:346–351. doi: 10.1007/s10434-000-0346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger KL, Nicholson SA, Dehdashti F, Siegel BA. FDG PET evaluation of mucinous neoplasms: correlation of FDG uptake with histopathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1005–1008. doi: 10.2214/ajr.174.4.1741005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, Taite H, Scoular R, Miller A, Reeve AE. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–405. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]