What role do antibiotics have in the treatment of uncomplicated skin abscesses after incision and drainage? A recent study suggested that, for small uncomplicated skin abscesses, antibiotics after incision and drainage improve the chance of short term cure compared with placebo. Triggered by this trial, the Rapid Recommendation team produced a new systematic review. Relying on this review and using the GRADE framework according to the BMJ Rapid Recommendation process, an expert panel makes a weak recommendation in favour of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX, co-trimoxazole) or clindamycin in addition to incision and drainage over incision and drainage alone. For patients who have chosen to initiate antibiotics, the panel issues a strong recommendation for TMP-SMX or clindamycin rather than a cephalosporin and a weak recommendation for TMP-SMX rather than clindamycin. Box 1 shows the articles and evidence linked to this Rapid Recommendation. The infographic presents the recommendations together with other pertinent information, including an overview of the absolute benefits and harms of candidate antibiotics in the standard GRADE format. The panel emphasises shared decision making in the choice of whether to initiate antibiotics and in which antibiotic to use, because the desirable and undesirable consequences are closely balanced: clinicians using MAGICapp ( http://magicapp.org/goto/guideline/jlRvQn/section/ER5RAn ) will find decision aids to support the discussion with patients. Table 2 below shows any evidence that has emerged since the publication of this article.

What you need to know.

For uncomplicated skin abscesses, we suggest using trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) or clindamycin in addition to incision and drainage rather than incision and drainage alone, and emphasise the need for shared decision making

TMP-SMX or clindamycin modestly reduces pain and treatment failure and probably reduces abscess recurrence, but increases the risk of adverse effects including nausea and diarrhoea

We suggest TMP-SMX rather than clindamycin because TMP-SMX has a lower risk of diarrhoea

Cephalosporins in addition to incision and drainage are probably not more effective than incision and drainage alone in most settings

From a societal perspective, the modest benefits from adjuvant antibiotics may not outweigh the harms from increased antimicrobial resistance in the community, although this is speculative

Box 1. Linked articles in this BMJ Rapid Recommendation cluster.

-

Vermandere M, Aertgeerts B, Agoritsas T, et al. Antibiotics after incision and drainage for uncomplicated skin abscesses: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2018;360:k243

Summary of the results from the Rapid Recommendation process

-

Wang W, Chen W, Liu Y, et al. Antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020991

Review of all available randomised trials that assessed antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses

-

MAGICapp (http://magicapp.org/goto/guideline/jlRvQn/section/ER5RAn)

Expanded version of the results with multilayered recommendations, evidence summaries, and decision aids for use on all devices

Current understanding

A skin abscess is an isolated collection of pus within the dermis and deeper skin tissues. Uncomplicated skin abscesses are collections of pus within the skin structures and are usually caused by bacterial infections. Careful history and clinical examination are usually sufficient to diagnose a skin abscess.1 2 3 Skin abscesses present as single or multiple tender, erythematous, indurated nodules, often surrounded by an area of erythema or swelling.1 Fluctuance beneath the skin often indicates a fluid filled cavity. There may be a pustule at the area where the abscess is closest to the skin or spontaneous drainage of pus.3 The use of point-of-care ultrasonography can help differentiate an abscess from other soft tissue infections in the emergency department.4

Skin infections are common. More than 4% of people seek treatment for skin infections annually in the United States.5 In European countries, it may be less common: in Belgium and the Netherlands about 0.5-0.6% visit their general practitioner with bacterial skin infections each year.6 7 8

Identifying the infecting pathogen may not be necessary for treating uncomplicated skin abscesses, but cultures can provide helpful information in patients with recurrent abscesses or systemic illness.1 3 The most common pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus, most often methicillin-resistant (MRSA), and several other bacteria, most originating from the skin flora.1 9MRSA accounts for a substantial number of visits by patients with skin and soft tissue infections.10 11 12

Table 1 summarises current management guidelines, which do not recommend antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses.

Table 1.

Current recommendations for antibiotics in patients with skin abscesses*

| Recommendation | Situations where antibiotics are recommended | |

|---|---|---|

| IDSA2 | Against | Systemic illness |

| EBM Guidelines13 | Against | Systemic illness, extensive tissue damage, nasal region, immunocompromising conditions, artificial joint |

| NHG14 | Against | 1 dose in patients with immunocompromising conditions, artificial joint, or at high risk of endocarditis |

| ESCMID | No recommendation available | N/A |

These guidelines have not taken account of the new evidence captured in our Rapid Recommendations.

IDSA=Infectious Diseases Society of America; EBM=Evidence-Based Medicine; NHG=Nederlands Huisartsen Genootschap; ESCMID=European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases.

How the recommendation was created.

The scope of the recommendation and the outcomes important to patients were defined by an international guideline panel consisting of two adults with lived experience of skin abscesses, one adult with lived experience as a carer for a child with skin abscess, five general practitioners, three paediatric or adult infectious disease physicians, four general internists, a general paediatrician, a dermatologist, and several health research methodologists. They requested a systematic review on the benefits and harms of different antibiotics to inform the recommendation.15 The panel then met online to discuss the evidence and to formulate specific recommendations. As with all BMJ Rapid Recommendations, no panel member had financial conflicts of interest; intellectual and professional conflicts were minimised and managed (see appendix 1 on bmj.com).17

The panel followed the BMJ Rapid Recommendations procedures for creating a trustworthy recommendation, including using the GRADE approach to critically appraise the evidence and to move from evidence to recommendations (appendix 2 on bmj.com).17 31 32 33 The panel initially identified patient-important outcomes and subgroup hypotheses needed to inform the recommendation. When creating the recommendation, the panel considered the balance of benefits, harms, costs, burdens of the treatments, the quality of evidence for each outcome, typical patient values and preferences and their expected variations, as well as acceptability.34 Recommendations can be strong or weak, for or against a course of action. The recommendations take a patient-centred perspective which de-emphasises public health, societal, and health payer point of view.

The evidence

To inform the recommendations, the guideline panel requested a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the effects of adjuvant antibiotic therapy compared with no antibiotic therapy in addition to incision and drainage in patients with uncomplicated skin abscesses.15

A large RCT published in March 2016 suggested that TMP-SMX treatment resulted in a higher cure rate than placebo among patients with a drained cutaneous abscess.16 Another RCT published in June 2017 found that, compared with incision and drainage alone, clindamycin or TMP-SMX in addition to incision and drainage improved short term outcomes in patients who had an uncomplicated skin abscess.5 The Rapid Recommendations team believed these two trials, in addition to the existing body of evidence, might change practice.17

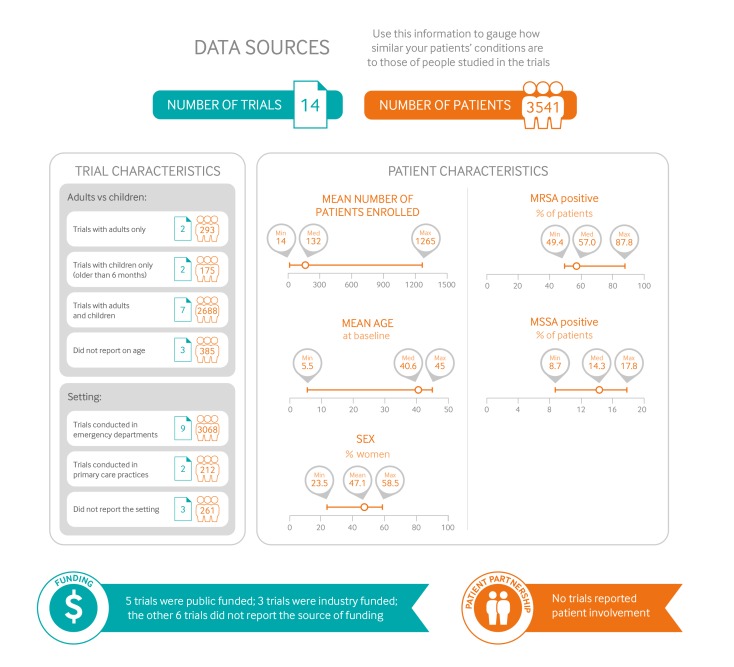

Figure 1 gives an overview of the characteristics of patients and trials included in the systematic review of the effects of antibiotics on uncomplicated skin abscesses. There were 14 RCTs: eight included a comparison of antibiotics versus no antibiotics, and seven included a comparison of two different antibiotics. Explicit descriptions of abscess definitions, for each trial, were summarised in the accompanying systematic review (table C of appendix 2).15 The largest trial specifically focused on small abscesses (all <5 cm diameter and about half ≤2 cm) in patients who had no signs of systemic infection.5 The RCTs included participants with skin abscesses anywhere on the body.

Fig 1.

Characteristics of patients and trials included in systematic review of the effects of antibiotics on uncomplicated skin abscesses. (MRSA = meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA = meticillin susceptible S aureus)

Eleven trials reported study setting, of which nine were conducted in emergency departments,5 16 18 19 20 21 22 23 one in outpatient dermatology clinics,24 and one in an Integrated Soft Tissue Infection Services (ISIS) clinic involving patients with high rates of comorbidity, such as infection with hepatitis C, hepatitis B, or HIV.25 The RCTs included children and adults. Almost all patients underwent incision and drainage for their skin abscess. The most common pathogen was MRSA (49-88%) followed by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA, 9-18%).

Understanding the recommendation

Absolute benefits and harms

The infographic provides an overview of the recommendations and the absolute benefits and harms of different antibiotics. Estimates of the baseline risk for side effects are derived from the control groups of the trials in the systematic review. Detailed information can also be viewed through MAGICapp, including consultation decision aids designed to support shared decision making with patients.26

This clinical practice guideline is applicable to patients with uncomplicated skin abscesses, which means that it is not applicable to patients with evidence of systemic illness (such as sepsis), deep tissue infections, superficial infections (such as pustules and papules), hidradenitis suppurativa, or immunocompromising conditions, and patients who do not undergo incision and drainage.

The first recommendation relates to the usefulness of adjuvant TMP-SMX or clindamycin compared with no antibiotics in addition to incision and drainage. The effects of other antibiotics are speculative, except for cephalosporins, which are probably less effective or not effective (see evidence summary for recommendation No 2). Compared with no antibiotics, TMP-SMX or clindamycin reduces the absolute risk of treatment failure by approximately 5% at one month (high quality evidence). In patients who were cured, these antibiotics reduced the absolute risk of recurrence at three months by approximately 8% (high quality evidence). When considering both treatment failure and abscess recurrence, antibiotic therapy thus provides an approximate 13% reduction (high quality evidence). TMP-SMX or clindamycin probably provides a modest reduction in pain (tenderness) during treatment (7% fewer), and a small reduction in hospitalisation (2% fewer) and in similar infections among household contacts (2% fewer) (all moderate quality evidence). Considering the characteristics of involved patients and medical conditions may differ between emergency departments and general practices, antibiotics may confer an even smaller benefit in patients who present to their GP. Antibiotics probably do not reduce the risk of serious or invasive infections or death (moderate quality evidence).

The occurrence of adverse effects depends on the antibiotic. With clindamycin, the risk of gastrointestinal side effects (predominately diarrhoea) is approximately 10% higher than with no antibiotics (high quality evidence). TMP-SMX probably increases the risk of gastrointestinal side effects by a smaller amount (approximately 2%; moderate quality evidence), and it is predominately nausea rather than diarrhoea. The severity of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea was not described, but is likely to range from mild to severe. Two large trials monitored for Clostridium difficile infection with routine clinical monitoring and no such infection occurred in any treatment arm.15

Overall, there is no important difference in treatment failure between TMP-SMX and clindamycin (high quality evidence). In patients who were initially cured, one study suggested that clindamycin may reduce the risk of early recurrence at one month by approximately 7% (low quality evidence),5 but the confidence interval was wide and this result is inconsistent with indirect evidence from other RCTs, which suggests that the reduction in risk of abscess recurrence compared with placebo is similar for both TMP-SMX and clindamycin. Whether clindamycin reduces abscess recurrence more than TMP-SMX is therefore uncertain (low quality evidence). Local resistance patterns may affect the relative effectiveness of each antibiotic option.27 28 29 30 Clindamycin has a 10% higher risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea than TMP-SMX (high quality evidence).

The panel also considered evidence for cephalosporins compared with TMP-SMX and clindamycin used for uncomplicated skin abscesses. The network meta-analysis suggested that, at least in settings with a substantial prevalence of MRSA, cephalosporins in addition to incision and drainage probably do not reduce treatment failure compared with incision and drainage alone (moderate quality evidence). Both early and later generation cephalosporins probably confer a higher risk of treatment failure compared with either TMP-SMX or clindamycin (moderate quality evidence). The RCTs investigating cephalosporins did not report sufficient information to directly compare other outcomes. However, the panel felt that cephalosporins were unlikely to provide any other benefits if they do not reduce the risk of treatment failure compared with placebo (low quality evidence). This evidence directly applies to almost all settings where the prevalence of MRSA is more than 10%.1 2

The panel is confident that the evidence applies to almost all patients with uncomplicated skin abscesses treated with incision and drainage: adults and children, patients presenting to emergency departments and to primary care practices, smaller and larger abscesses, first abscess occurrences and recurrences, and abscesses with unknown infection pathogens. The systematic review and meta-analyses contained adequate representation from such groups and settings, and results were consistent between pre-specified subgroups.15

Values and preferences

The panel believes that there is a high degree of variability between patients and carers weighing the expected desirable and undesirable consequences of antibiotic therapy compared with no antibiotic therapy. This variation is reflected in the weak recommendation, which warrants shared decision making to ensure that each individual’s decision is in line with what they consider most important. The expected benefit of antibiotic therapy in reducing pain, risk of treatment failure, and recurrence is modest, but large enough that the panel anticipates that most fully informed patients would value these benefits sufficiently to choose antibiotic treatment. This might particularly be the case when, for example, the abscess is very painful, perhaps because of location in sensitive places (such as groin, axillae, etc).

For patients who decide to initiate antibiotic treatment, reasonable choices include either TMP-SMX or clindamycin. In some settings, cephalosporins or other antibiotics are often prescribed for skin abscesses. Given that, in most circumstances, cephalosporins probably do not provide any additional benefit beyond incision and drainage alone, the panel felt that all or almost all patients would choose to use antibiotic options with proven efficacy (TMP-SMX or clindamycin), hence the strong recommendation against cephalosporins.

People who place a higher value on the possibility of avoiding abscess recurrence may choose clindamycin, while those who place a higher value on avoiding diarrhoea and on minimising costs are likely to prefer TMP-SMX.

Person-centred versus societal perspective (impact on antibiotic resistance)

The recommendations explicitly take a person-centred perspective rather than a public health or societal perspective. The use of antibiotics is associated with the emergence of antibiotic resistance within the community and may increase the risk of antibiotic resistant infections in community members. The increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance are a public health priority. From a societal perspective, it is possible that the modest benefits from adjuvant antibiotics in this scenario would not outweigh the risk of increased antimicrobial resistance in the community. However, the impact of an individual course of antibiotics on community resistance rates is unknown. Therefore, whether antibiotics in this situation provide a net benefit or harm to society is highly speculative. Clinicians engaging in shared decision making can also address the issue of antibiotic resistance or the local prevalence of other pathogens (such as Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) positive Staphylococcus aureus) with patients facing this decision.

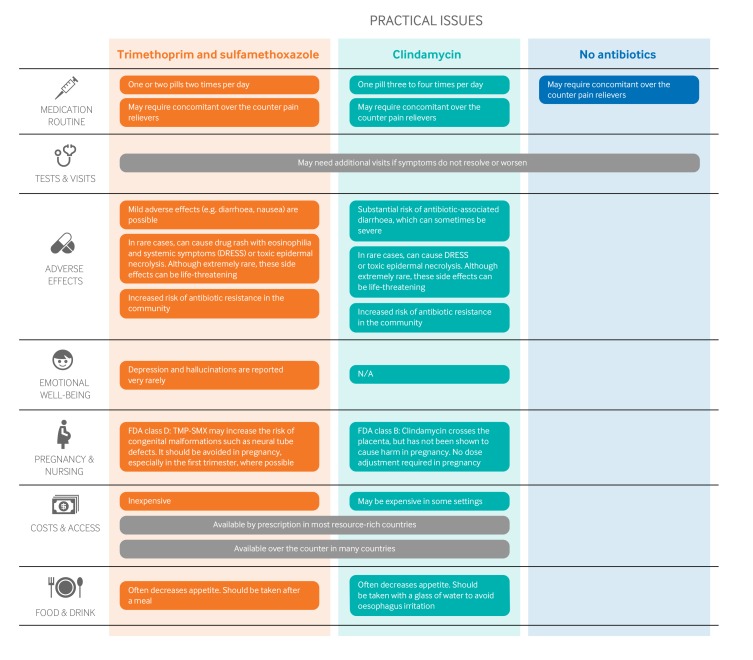

Practical issues and other considerations

Figure 2 outlines the key practical issues for patients and clinicians discussing initiating antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses after incision and drainage, which are also accessible as decision aids along with the evidence in an expanded format to support shared decision making in MAGICapp. The antibiotic course was typically five to 10 days in the RCTs, and dosing varied. TMP-SMX may slightly increase the risk of congenital malformations, including neural tube defects, when prescribed to pregnant women.

Fig 2.

Practical issues about use of antibiotics after incision and drainage of uncomplicated skin abscesses. (FDA = US Food and Drug Administration)

Costs and resources

TMP-SMX is inexpensive; clindamycin is probably more expensive in most places. However, the overall impact on costs to the individual and the healthcare payer are uncertain when the consequences of each option are considered.

Future research

Key research questions to inform decision makers and future guidelines are:

What is the impact of different types of antibiotics in settings where MRSA is rare (prevalence <10%)?

Do antibiotics have different effects in different populations, such as people who are immunocompromised or in people with recurrent skin abscesses?

What are the long term effects (such as >6 months) of antibiotics on abscess recurrence, Clostridium difficile infection, and MRSA resistance to TMP-SMX or clindamycin?

Is a shorter course of antibiotics (such as 5 days) as effective as a longer course (10 days)?

Is topical therapy (such as iodine, honey, silver, other antimicrobials) effective for treating uncomplicated skin abscesses compared with systemic therapy? Do other adjunctive measures, such as nasal decontamination or antisepsis for the body, reduce the risk that skin abscesses will recur?

Updates to this article

Table 2 shows evidence which has emerged since the publication of this article. As new evidence is published, a group will assess the new evidence and make a judgment on to what extent it is expected to alter the recommendation.

Table 2.

New evidence which has emerged after initial publication

| Date | New evidence | Citation | Findings | Implications for recommendation(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are currently no updates to the article. | ||||

Education into practice.

Do you currently consider antibiotics for patients with uncomplicated skin abscesses after surgical treatment?

What information could you share with your patient to help reach a decision together?

Would you consider using online decision aid tools (such as the one available on MAGICapp) to facilitate shared decision making?

How patients were involved in the creation of this article.

Three people with lived experience of skin abscesses were full panel members: two had previously experienced skin abscesses before (one with recurrent abscesses), and one person is a parent of a child who experienced a skin abscess. These panel members identified patient-important outcomes, and led the discussion on values and preferences. These patient partners agreed that, although pain reduction was the most important outcome to them, these values may not be shared by all patients. The close balance between desirable and undesirable consequences made it difficult for them (and the panel) to decide which options most individuals would choose.

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Infographic: Summary of recommendations and evidence

Appendix 1: List of panel members

Appendix 2: Full list of authors’ declarations of interests

Appendix 3: Methodology for development of BMJ Rapid Recommendations with examples specific to this paper

Appendix 4: The full information available on the MAGICapp

Competing interests: All authors have completed the BMJ Rapid Recommendations interests disclosure form and a detailed, contextualised description of all disclosures is reported in appendix 2 on bmj.com. As with all BMJ Rapid Recommendations, the executive team and The BMJ judged that no panel member had any financial conflict of interest. Professional and academic interests are minimised as much as possible, while maintaining necessary expertise on the panel to make fully informed decisions.

Funding: This guideline was not funded. R Siemieniuk is partially funded through a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship.

Transparency: B Aertgeerts affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the recommendation being reported; that no important aspects of the recommendation have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the recommendation as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

This BMJ Rapid Recommendation article is one of a series that provides clinicians with trustworthy recommendations for potentially practice changing evidence. BMJ Rapid Recommendations represent a collaborative effort between the MAGIC group (www.magicproject.org) and The BMJ. A summary is offered here and the full version including decision aids is on the MAGICapp (www.magicapp.org), for all devices in multilayered formats. Those reading and using these recommendations should consider individual patient circumstances, and their values and preferences and may want to use consultation decision aids in MAGICapp to facilitate shared decision making with patients. We encourage adaptation and contextualisation of our recommendations to local or other contexts. Those considering use or adaptation of content may go to MAGICapp to link or extract its content or contact The BMJ for permission to reuse content in this article.

References

- 1. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59:e10-52. 10.1093/cid/ciu296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52:285-92. 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mistry RD. Skin and soft tissue infections. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1063-82. 10.1016/j.pcl.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barbic D, Chenkin J, Cho DD, Jelic T, Scheuermeyer FX. In patients presenting to the emergency department with skin and soft tissue infections what is the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasonography for the diagnosis of abscess compared to the current standard of care? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013688. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daum RS, Miller LG, Immergluck L, et al. DMID 07-0051 Team A placebo-controlled trial of antibiotics for smaller skin abscesses. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2545-55. 10.1056/NEJMoa1607033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NIVEL Primary care database: Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research. 2016. www.nivel.nl/en/dossier/nivel-primary-care-database

- 7. FaMe-net 2014. www.transhis.nl/language/nl/.

- 8. Truyers C, Goderis G, Dewitte H, Akker Mv, Buntinx F. The Intego database: background, methods and basic results of a Flemish general practice-based continuous morbidity registration project. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:48. 10.1186/1472-6947-14-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. EMERGEncy ID Net Study Group Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med 2006;355:666-74. 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Microbiology of skin and soft tissue infections in the age of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2013;76:24-30. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1585-91. 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Karamatsu ML, Thorp AW, Brown L. Changes in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections presenting to the pediatric emergency department: comparing 2003 to 2008. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:131-5. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318243fa36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salava A. Skin abscess and folliculitis. Evidence-Based Med Guideline 2017. www.ebm-guidelines.com/dtk/ebmg/home.

- 14.Bons S, Bouma M, Draijer L, et al. NHG-standaard bacteriële huidinfecties (tweede herziening). 2017. www.nhg.org/standaarden/volledig/nhg-standaard-bacteriele-huidinfecties.

- 15. Wang W. Antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Talan DA, Mower WR, Krishnadasan A, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus placebo for uncomplicated skin abscess. N Engl J Med 2016;374:823-32. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, Macdonald H, Guyatt GH, Brandt L, Vandvik PO. Introduction to BMJ Rapid Recommendations. BMJ 2016;354:i5191. 10.1136/bmj.i5191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duong M, Markwell S, Peter J, Barenkamp S. Randomized, controlled trial of antibiotics in the management of community-acquired skin abscesses in the pediatric patient. Ann Emerg Med 2010;55:401-7. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Llera JL, Levy RC. Treatment of cutaneous abscess: a double-blind clinical study. Ann Emerg Med 1985;14:15-9. 10.1016/S0196-0644(85)80727-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmitz GR, Bruner D, Pitotti R, et al. Randomized controlled trial of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated skin abscesses in patients at risk for community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:283-7. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Macfie J, Harvey J. The treatment of acute superficial abscesses: a prospective clinical trial. Br J Surg 1977;64:264-6. 10.1002/bjs.1800640410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giordano PA, Elston D, Akinlade BK, et al. Cefdinir vs. cephalexin for mild to moderate uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections in adolescents and adults. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:2419-28. 10.1185/030079906X148355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller LG, Daum RS, Creech CB, et al. DMID 07-0051 Team Clindamycin versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated skin infections. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1093-103. 10.1056/NEJMoa1403789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keiichi F, Eiichiro N, Hisashi T. Clinical evaluation of cefadroxil in the treatment of superficial suppurativve skin and soft tissue infections - a double-blind study comparing to L-cephalexin. Clin Eval 1982;10:175-200. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rajendran PM, Young D, Maurer T, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of cephalexin for treatment of uncomplicated skin abscesses in a population at risk for community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007;51:4044-8. 10.1128/AAC.00377-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agoritsas T, Heen AF, Brandt L, et al. Decision aids that really promote shared decision making: the pace quickens. BMJ 2015;350:g7624. 10.1136/bmj.g7624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stein M, Komerska J, Prizade M, Sheinberg B, Tasher D, Somekh E. Clindamycin resistance among Staphylococcus aureus strains in Israel: implications for empirical treatment of skin and soft tissue infections. Int J Infect Dis 2016;46:18-21. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Macmorran E, Harch S, Athan E, et al. The rise of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus: now the dominant cause of skin and soft tissue infection in central Australia. Epidemiol Infect 2017;145:2817-26. 10.1017/S0950268817001716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nurjadi D, Friedrich-Jänicke B, Schäfer J, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections in intercontinental travellers and the import of multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015;21:567.e1-10. 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nurjadi D, Olalekan AO, Layer F, et al. Emergence of trimethoprim resistance gene dfrG in Staphylococcus aureus causing human infection and colonization in sub-Saharan Africa and its import to Europe. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:2361-8. 10.1093/jac/dku174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vandvik PO, Otto CM, Siemieniuk RA, et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with severe, symptomatic, aortic stenosis at low to intermediate surgical risk: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2016;354:i5085. 10.1136/bmj.i5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aertgeerts B, Agoritsas T, Siemieniuk RAC, et al. Corticosteroids for sore throat: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2017;358:j4090. 10.1136/bmj.j4090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE Working Group GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924-6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation-determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:726-35. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Infographic: Summary of recommendations and evidence

Appendix 1: List of panel members

Appendix 2: Full list of authors’ declarations of interests

Appendix 3: Methodology for development of BMJ Rapid Recommendations with examples specific to this paper

Appendix 4: The full information available on the MAGICapp