ABSTRACT

Two-component systems (TCSs) of bacteria regulate many different aspects of the bacterial life cycle, including pathogenesis. Most TCSs remain uncharacterized, with no information about the signal(s) or regulatory targets and/or role in bacterial pathogenesis. Here, we characterized a TCS in the plant-pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 composed of the histidine kinase CvsS and the response regulator CvsR. CvsSR is necessary for virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, since ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains produced fewer symptoms than the wild type (WT) and demonstrated reduced growth on multiple hosts. We discovered that expression of cvsSR is induced by Ca2+ concentrations found in leaf apoplastic fluid. Thus, Ca2+ can be added to the list of signals that promote pathogenesis of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 during host colonization. Through chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and global transcriptome analysis (RNA-seq), we discerned the CvsR regulon. CvsR directly activated expression of the type III secretion system regulators, hrpR and hrpS, that regulate P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 virulence in a type III secretion system-dependent manner. CvsR also indirectly repressed transcription of the extracytoplasmic sigma factor algU and production of alginate. Phenotypic analysis determined that CvsSR inversely regulated biofilm formation, swarming motility, and cellulose production in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Overall, our results show that CvsSR is a key regulatory hub critical for interaction with host plants.

IMPORTANCE Pathogenic bacteria must be able to react and respond to the surrounding environment, make use of available resources, and avert or counter host immune responses. Often, these abilities rely on two-component systems (TCSs) composed of interacting proteins that modulate gene expression. We identified a TCS in the plant-pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae that responds to the presence of calcium, which is an important signal during the plant defense response. We showed that when P. syringae is grown in the presence of calcium, this TCS regulates expression of factors contributing to disease. Overall, our results provide a better understanding of how bacterial pathogens respond to plant signals and control systems necessary for eliciting disease.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas syringae, alginate, biofilms, calcium signaling, two-component regulatory systems

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas syringae is a hemibiotrophic plant-pathogenic bacterial species composed of approximately 50 pathovars that differ in their host range (1, 2). This species causes significant economic losses to a number of crops, with certain pathovars being responsible for severe outbreaks of disease worldwide. Recent outbreaks include bleeding canker disease on horse chestnut caused by P. syringae pv. aesculi and bleeding canker disease on kiwi caused P. syringae pv. actinidiae (3, 4). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 causes bacterial speck of tomato and was one of the first bacterial plant pathogens to be sequenced (5). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 is frequently used for deciphering molecular plant-pathogen interactions due to its ability to infect both tomato and Arabidopsis thaliana. Research on P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 has provided insights into the role of the type III secretion system (T3SS) in host-nonhost interactions and the role that type III effectors (T3Es) play in triggering the hypersensitive response (HR) in nonhosts (6). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 has a well-annotated genome, making it an ideal candidate for understanding the physiology of plant-pathogenic bacteria and understanding host-pathogen interactions.

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 requires a T3SS to deliver effectors into host cells and become pathogenic. Hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (hrp) genes and hrp conserved (hrc) genes code for the structural components of the T3SS, while hrp outer protein (hop) genes and avirulence (avr) genes code for the secreted T3Es (7, 8). Both T3SS and T3E genes are in turn regulated by a subset of hrp genes. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factor HrpL directly regulates both hrc and hop genes (9, 10). The enhancer binding proteins (EBPs), HrpR and HrpS, form a heterohexameric complex that binds and activates σ54 and allows for transcription of hrpL (11). In addition to regulating transcription of hrpL, HrpR and HrpS regulate transcription of many genes that are not in the HrpL regulon (12). No direct transcriptional activators have been described for hrpR and hrpS; however, the TCS RhpRS has been shown to be a direct repressor of hrpR and hrpS (13).

In P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, multiple sensory systems regulate the T3SS and hrp genes, including GacA and AlgU (14, 15). The response regulator, GacA, regulates expression of the small RNAs (sRNAs) rsmX, rsmY, rsmZ, and five additional rsmX paralogs in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (16). The rsmZ and rsmY sRNAs in turn bind and sequester the global regulator RsmA, while it is still unclear whether the rsmX sRNAs bind RsmA as well (14, 16). RsmA regulates a variety of genes posttranscriptionally in P. syringae, including genes that code for components of the T3SS, phytoxins, and pyoverdine (17). The ECF sigma factor AlgU has been primarily characterized as the regulator of production of the negatively charged exopolysaccharide (EPS) alginate in Pseudomonas (15, 18). In P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, AlgU also regulates genes involved in osmotolerance, reactive oxygen species (ROS) tolerance, motility, and pathogenicity (15). In the case of pathogenicity, AlgU regulates hrpR, hrpS, and hrpL (15). Regulation of the T3SS through sensory systems highlights the importance of environmental signals during P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 pathogenesis.

Ca2+ is abundant in the apoplast, and little is known about its role as an environmental signal for P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (19). During a compatible interaction between P. syringae and the common bean, Phaseolus vulgaris, the concentration of Ca2+ increases within the apoplast (20). Similar increases in Ca2+ concentration occurs in the xylem of Nicotiana tabacum infected with Xylella fastidiosa (21). Bacteria strictly regulate Ca2+ concentrations in the cytoplasm at a much lower concentration than Ca2+ concentrations found extracellularly (22). This difference in concentration allows bacteria to use Ca2+ as an environmental signal (22–24). Changes in extracellular Ca2+ concentrations modulate several bacterial virulence traits for animal pathogens, including biofilm formation, motility, EPS production, T3SS deployment, and quorum sensing (25–32). Changes in Ca2+ concentration also affect pectinolytic enzyme production in the necrotrophic plant pathogen Pectobacterium carotovorum and affect biofilm formation in the xylem-limited plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa (32, 33). However, in many hemibiotrophic bacterial plant pathogens, such as Pseudomonas syringae, Xanthomonas, and Ralstonia, there is little known about how these pathogens respond to changes in Ca2+ concentration and whether there are regulatory systems induced by Ca2+. Given the abundance of Ca2+ in the plant apoplast, it is possible that Ca2+ represents an important signaling molecule for this group of plant pathogens.

Bacteria have evolved TCSs and ECF sigma factors to react to changes in the extracellular environment. TCSs transform signals perceived by bacteria into a cellular response using a signal relay that is commonly made up of a transmembrane histidine kinase (HK) and an intracellular response regulator (RR). During signal transduction, an HK will typically transfer a phosphate group to an RR. Following phosphorylation, the RR will perform its designated function, such as binding DNA to regulate the expression of genes (34). The genome of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 encodes a large number of HKs and RRs (69 HKs and 95 RRs), many of which remain uncharacterized (35). We have previously reported that expression of a TCS in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 encoded by PSPTO_3380 (HK) and PSPTO_3381 (RR) is induced by Fe3+ (36). The expression pattern is similar to the expression pattern of HrpL-regulated genes (36). However, PSPTO_3380 and PSPTO_3381 are not considered to be part of the HrpL regulon (9, 10). We also found that PSPTO_3380 and PSPTO_3381 are directly regulated by the ferric uptake regulator (37). In the current study, we showed that PSPTO_3380 and PSPTO_3381 represent a Ca2+-induced, virulence-associated TCS in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. We also identified the PSPTO_3381 regulon using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by next-generation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and transcriptome analysis (RNA-seq). In reference to the phenotype of PSPTO_3380 and PSPTO_3381, we suggest naming this TCS the calcium, virulence, and swarming sensor (CvsS) and regulator (CvsR) and refer to it as such throughout this article.

RESULTS

CvsS and CvsR affect virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000.

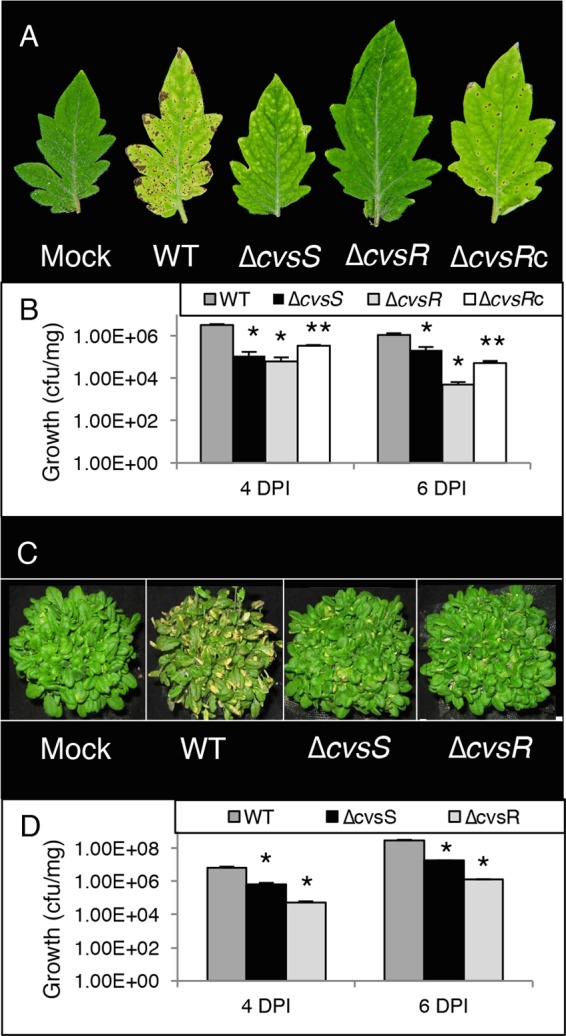

In order to determine if cvsS and cvsR affect the ability of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 to cause disease, tomato plants were dip inoculated with ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains. At 6 days postinoculation (dpi), tomato plants inoculated with either the ΔcvsS or ΔcvsR strain produced fewer symptoms than those inoculated with the wild-type (WT) strain (Fig. 1A). The ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains also showed reduced growth on tomato plants compared to the WT at 4 dpi and 6 dpi (Fig. 1B). Both symptoms and growth of the ΔcvsR strain could be partially restored with a single-copy chromosomal complementation of cvsR (cvsRc) (Fig. 1A and B). In addition, A. thaliana was vacuum infiltrated with either the WT, ΔcvsS, or ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain to determine whether CvsSR was involved in virulence for multiple hosts. Similar to the case for tomato plants, A. thaliana plants inoculated with the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains showed a reduction in symptom development as well as a reduction in growth compared to those inoculated with the WT (Fig. 1C and D). These results demonstrate that CvsSR is associated with growth and virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in multiple hosts. In addition, since reduced virulence was observed upon dip inoculation (a natural mode of entry via stomates) and vacuum infiltration (which bypasses natural entry), we conclude that CvsSR is necessary for full virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 during growth in the apoplast.

FIG 1.

Growth and symptoms of WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains on tomato and A. thaliana. (A) Image of symptoms at 6 dpi of tomato dip inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains. (B) Growth (CFU/mg) at 4 dpi and 6 dpi for the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains infecting tomato. The strains were inoculated at 2 × 107 CFU/ml. Average bacterial growth in three plants is shown, with the error bars representing the standard error between the three replicates. (C) Image of symptoms at 4 dpi on A. thaliana vacuum infiltrated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains. (D) Growth (CFU/mg) at 4 dpi and 6 dpi for the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains infecting A. thaliana that had been inoculated at 3 × 104 CFU/ml. Average bacterial growth in three plants is shown, with the error bars representing the standard error between the three replicates. In panels B and D, * denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.01 between growth of the WT and ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains and ** denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.01 between the ΔcvsR and ΔcvsRc strains, determined using Student's two-tailed t test.

Calcium induces expression of cvsSR.

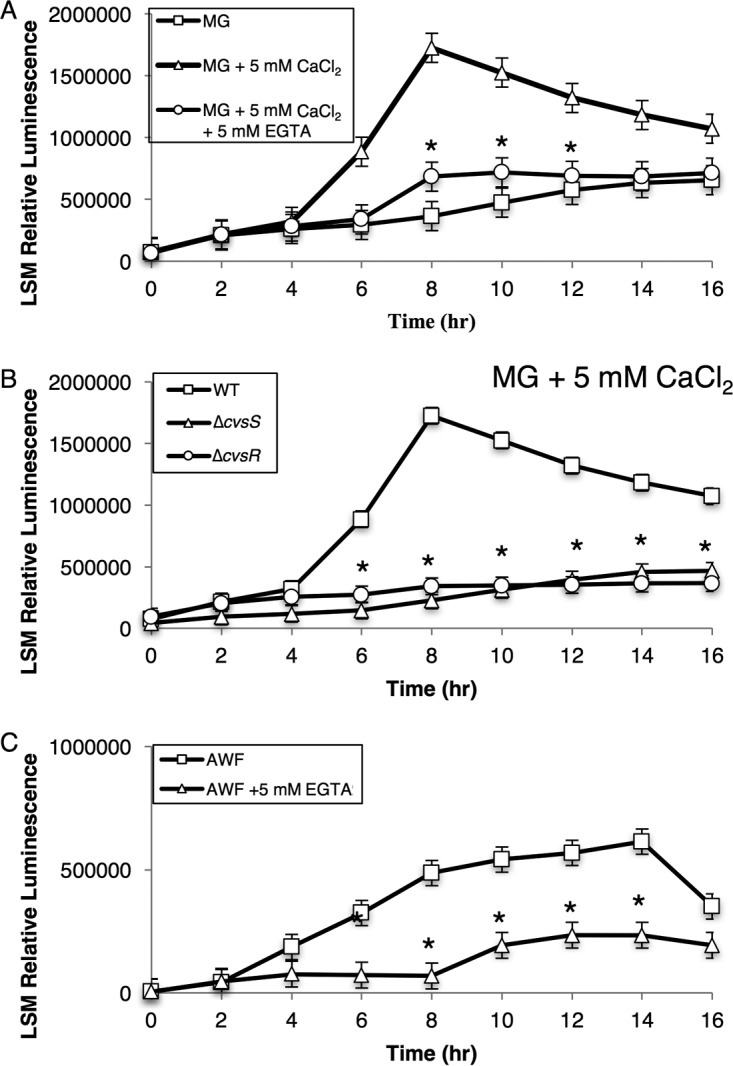

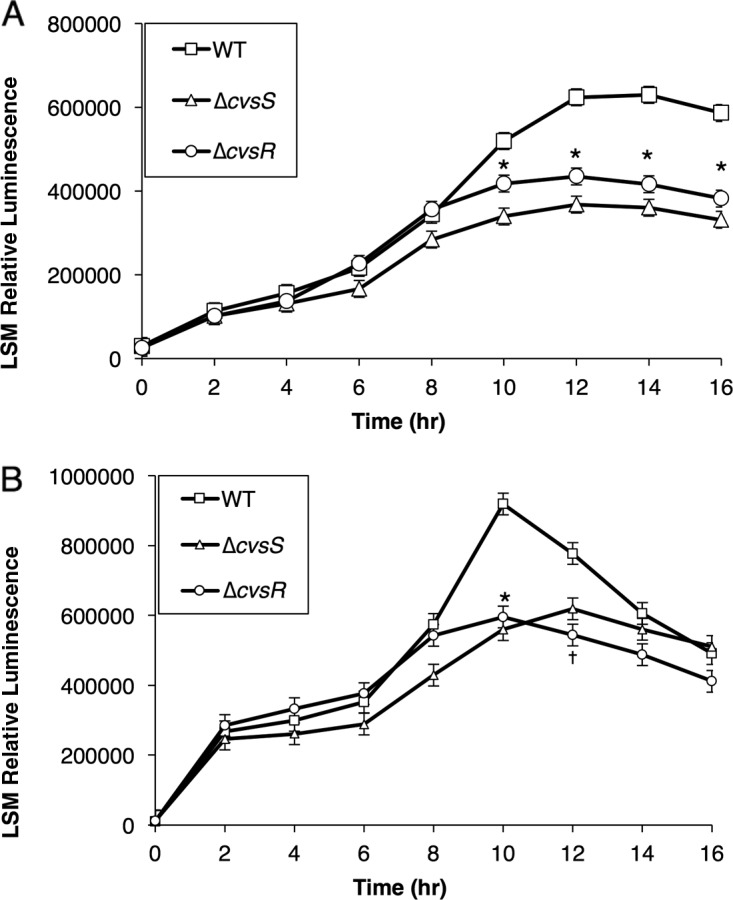

The TCS orthologous to CvsSR in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is induced by Ca2+ (38). To test for induction of cvsS and cvsR by Ca2+, we designed a luciferase promoter gene construct that included 400 bp upstream of PSPTO_3383 (PcvsSR), which included a previously mapped transcriptional start site for PSPTO_3383, and introduced it into WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (39). Expression of this construct should reflect expression of the promoter for cvsS and cvsR, as we found that cvsS, cvsR, PSPTO_3382, and PSPTO_3383 formed an operon by using reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The addition of Ca2+ to mannitol glutamate (MG) medium resulted in a significant increase in PcvsSR after 6 h of growth compared to the basal level of expression in MG medium (Fig. 2A). To test whether the chelation of Ca2+ would inhibit Ca2+-induced expression of PcvsSR, we added the Ca2+ chelator EGTA to MG medium supplemented with Ca2+. No increase in expression of PcvsSR was observed when P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 was grown in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+ and EGTA compared to when P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 was grown in MG medium (Fig. 2A). From these data, we conclude that expression of PcvsSR is induced by Ca2+.

FIG 2.

Luminescence assays to assess activity of PcvsSR in the WT grown in MG, MG with 5 mM CaCl2, and MG with 5 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM EGTA over the course of 16 h (A), in the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains grown in MG with 5 mM CaCl2 (B), and in the WT grown in AWF and AWF with 5 mM EGTA (C). The relative luminescence was calculated by using the total luminescence relative to OD600. Experiments were performed three times. The three experiments were compiled using a least-squares mean regression. The error bars represent standard deviation generated by the differences observed between samples. * denotes statistically significant differences determined using a Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test with a P value of <0.01 between MG with 5 mM CaCl2 and the two other conditions (A), between the WT and ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains (B), and between AWF and AWF with 5 mM EGTA (C).

TCSs, including the TCS orthologous to CvsSR in P. aeruginosa, commonly autoregulate (40). We compared the expression of PcvsSR in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains to that in the WT when grown in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+. Expression of PcvsSR was significantly reduced in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains compared to the WT (Fig. 2B). These data show that CvsSR positively autoregulates.

The leaf apoplast contains anywhere from 10 μM to 10 mM free Ca2+ (19). Based on these data, we hypothesized that Ca2+ could induce expression of cvsSR during growth in planta. Apoplastic washing fluid (AWF) was extracted from tomato leaves, and elemental analysis was then performed using inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS). Based on data from three samples, the concentration of calcium in the tomato leaf apoplast was an average of 9.7 mM with a standard deviation of 0.1 mM (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Therefore, we concluded that the concentration of Ca2+ was likely high enough to induce expression of PcvsSR in AWF. We grew P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 in AWF and found that PcvsSR increased over time (Fig. 2C). Addition of EGTA to AWF reduced expression of PcvsSR, suggesting that Ca2+ likely induced cvsSR in AWF and also in planta (Fig. 2C).

Identification of direct targets for CvsR in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000.

ChIP-seq was employed in order to determine regions of the genome bound by the predicted DNA binding response regulator CvsR. The ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain was complemented with pBS46::cvsR-FLAG (ΔcvsR cvsR-FLAG). To determine if the FLAG-tagged protein was active, expression of pBS59::PcvsSR was evaluated in the ΔcvsR cvsR-FLAG strain. When the ΔcvsR cvsR-FLAG strain was grown in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+, expression of PcvsSR was induced (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), suggesting that CvsR-FLAG was active. The ΔcvsR cvsR-FLAG strain was then grown for 18 h on nutrient broth (NB) agar plates supplemented with Ca2+ and succinate before cells were collected for ChIP. Prior to sequencing, the genomic region upstream of PSPTO_3383 and gyrA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, to determine enrichment of the immunoprecipitation (IP) fraction compared to the input fraction. The genomic region upstream of PSPTO_3383 was chosen as a positive control because CvsSR positively autoregulates and likely binds to an area near the previously mapped transcriptional start site for the operon that includes PSPTO_3383 (39). The gene gyrA had been used as a negative control in a previous ChIP-seq experiment on P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (37). It was determined that the region upstream of PSPTO_3383 was enriched 6.4-fold in the IP fraction compared to the input fraction, while no enrichment was observed for gyrA in the IP fraction compared to the input fraction. Sequencing was performed on libraries made from the IP and input samples. Overall, 5,609,692 reads were sequenced from the IP sample and 1,366,470 reads were sequenced from the input sample. In both cases, 97% of the reads aligned to the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome. Using MACS2, 199 peaks were identified using a false-discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of less than 0.05 (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material). Enriched peaks were found upstream of the gene PSPTO_5255, which codes for a carbonic anhydrase, and within the gene PSPTO_4969, which codes for an RHS repeat protein (Fig. 3A). Of note, two peaks were found upstream of the global virulence regulator hrpR (Fig. 3A). This makes CvsR the second described direct transcriptional regulator or hrpR (13). The first peak was found 749 bp upstream of the translational start site for hrpR (peak 1), and the second peak was found 63 bp upstream of the translational start site for hrpR (peak 2). No peak was called in the area upstream of PSPTO_3383. This was due to the fact that the area was disregarded during the peak calling using MACS because there was a large peak in cvsR due to the overexpression of this gene.

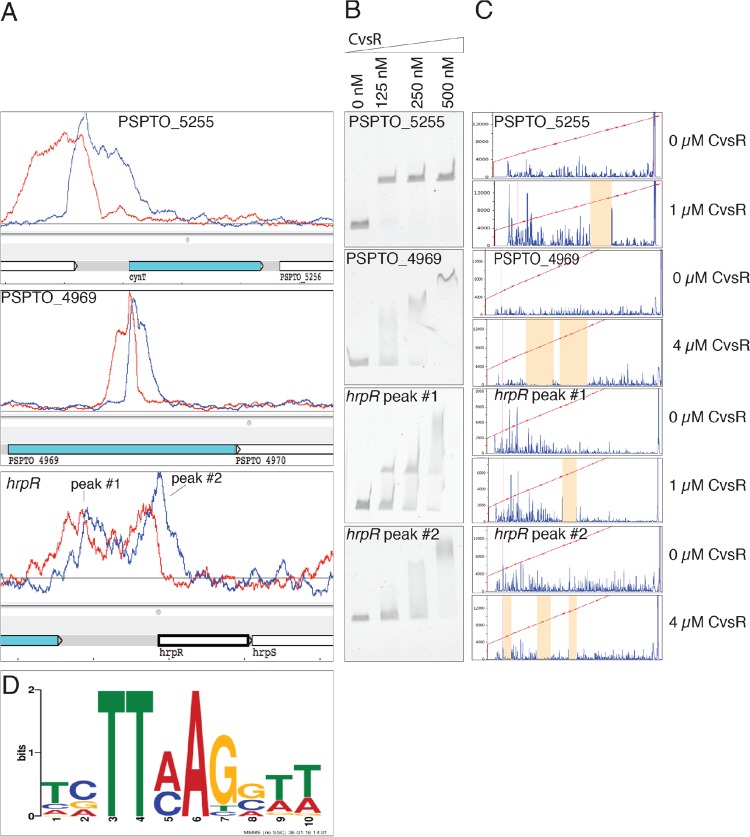

FIG 3.

Visualization of ChIP-seq data, CvsR DNA binding assays, and a putative CvsR binding motif. (A) Screenshot of the Artemis genome browser depicting areas of enrichment (peaks) in the ChIP-seq data upstream of PSPTO_5255, within PSPTO_4969, and upstream of hrpR. The red line represents the forward strand of DNA, while the blue line represents the reverse strand of DNA. ChIP-seq peaks occur where enriched areas for each strand overlap. (B) EMSA with concentrations of CvsR increasing from left to right for probes that code for genomic locations found within the ChIP-seq peaks for PSPTO_5255, PSPTO_4969, and hrpR. A shift in the migration of the probe with increasing concentrations of CvsR signifies binding of CvsR to that probe. (C) Fluorescent, nonradioactive DNase footprinting assays showing binding of CvsSR. The red line is a line of best fit that estimates the size (in base pairs) of each fragment made using a LIZ500 ladder. The blue peaks are fluorescent signal and represent the size of fragmented DNA. The areas that are highlighted in orange are regions with little fluorescence when CvsR is added at 1 μM or 4 μM to the reaction mixture compared to when no CvsR is added. These regions signify areas in the probes that were bound by CvsR. (D) Predicted binding motif for CvsR that was compiled by MEME using the areas 50 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of the center of the ChIP-seq peak.

Ten areas of the genome that showed enrichment in the ChIP-seq data were selected for further evaluation by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and DNase footprinting to confirm binding by CvsR. The 10 areas investigated included the genomic regions upstream of PSPTO_5255, PSPTO_0203, katB, oprF, hrpR, gidA, t-RNA, cys-1, and spf and within the gene PSPTO_4969 (Fig. 3B and C; see Fig. S3, S4, and S5 in the supplemental material). The area upstream of the gene PSPTO_0786 was used as a negative control for CvsR binding (Fig. S3 and S4). All showed a binding site by using DNase footprinting, and all of these areas except for the area upstream of oprF showed a clear shift by EMSA. It is possible that CvsR did not have a high affinity for the area of the genome upstream of oprF and that this was reflected in the undefined gel shift. It should be noted that according to the EMSA, CvsR showed a higher binding affinity for the peak 749 bp upstream of the translational start site for hrpR than for the second peak 63 bp upstream of the translational start site for hrpR.

We also checked for binding of CvsR upstream of PSPTO_3383 since CvsSR autoregulates and the operon includes cvsS and cvsR. The probe we created upstream of PSPTO_3383 included the putative transcriptional start site for the operon (39). We found that CvsR bound upstream of PSPTO_3383 (Fig. S3 and S4). These data provide additional support that CvsR autoregulates.

Using the 199 peaks we identified above, one 10-nucleotide (nt)-long binding motif for CvsR was determined (Fig. 3D). This type of motif is common for RRs in the OmpR family and suggests that only a single motif is required for CvsR to bind DNA (41). DNase footprinting data were consistent with this prediction, since binding sites mapped for hrpR peak 2 and PSPTO_0203 were approximately 11 to 14 bp and covered a single predicted binding motif (Fig. S5). Other areas from the DNase footprinting, like those mapped for PSPTO_5255 and hrpR peak 1, spanned around 26 bp and covered two direct repeats similar to the predicted binding motif (Fig. S5). A predicted binding motif was also produced using all the sites CvsR bound that were identified using the DNase footprinting probes (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The resulting motif was similar to the one determined from the ChIP-seq data.

Mapping the transcriptional landscape of CvsR.

RNA-seq was used to complement the ChIP-seq data and more thoroughly determine the CvsR regulon. The same condition used to grow cells for the ChIP-seq analysis was also used for extracting RNA for RNA-seq analysis. On average, 50,421,230 reads were generated from the ΔcvsR strain cDNA libraries and 35,215,281 reads were generated for the WT cDNA libraries. Of those reads, 97% aligned to the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome. From these data sets, 292 genes were differentially regulated between the WT and the ΔcvsR strain by 2-fold or more using an FDR cutoff less than 0.05. Of these genes, 181 genes were upregulated and 111 genes were downregulated in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). A subset of these genes is listed in Table 1. Changes in expression of a subset of differentially expressed genes were confirmed using qRT-PCR (see Data Set S3 in the supplemental material). Within the RNA-seq data set, ChIP-seq peaks were found within or upstream of 19 genes that were also differentially expressed in the ΔcvsR strain. These genes are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Selected genes differentially expressed between WT and ΔcvsR strains

| Category | Locus noa | Geneb | Descriptionc | Fold changed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motility | PSPTO_0911 | cheW | Chemotaxis protein | −2.24 |

| PSPTO_0915 | cheY | Chemotaxis protein | −2.73 | |

| PSPTO_1933 | flgB | Flagellar basal body rod protein | −2.55 | |

| PSPTO_1936 | flgE | Flagellar hook protein | −2.55 | |

| PSPTO_1949 | fliC | Flagellin | −4.51 | |

| PSPTO_1952 | fliS | Flagellar protein | −2.20 | |

| PSPTO_1953 | flgD | Basal body rod modification protein | −2.35 | |

| PSPTO_4156 | motY | Sodium-type flagellar protein | −2.13 | |

| Alginate biosynthesis and regulation | PSPTO_1232 | algA | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 2.81 |

| PSPTO_1233 | algF | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 3.01 | |

| PSPTO_1234 | algJ | Probable alginate O-acetylase | 3.21 | |

| PSPTO_1235 | algI | Probable alginate O-acetylase | 2.42 | |

| PSPTO_1236 | algL | Alginate lyase | 2.68 | |

| PSPTO_1237 | algX | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 2.86 | |

| PSPTO_1238 | algG | Poly(beta-d-mannuronate) C-5 epimerase | 3.27 | |

| PSPTO_1239 | algE | Alginate production protein | 3.29 | |

| PSPTO_1240 | algK | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 3.60 | |

| PSPTO_1241 | alg44 | Alginate biosynthesis protein | 3.15 | |

| PSPTO_1243 | algD | GDP-mannose 6-dehydrogenase | 2.56 | |

| PSPTO_4222 | algU | RNA polymerase sigma factor | 2.64 | |

| PSPTO_4222 | mucB | Sigma factor algU regulatory protein | 2.46 | |

| PSPTO_4223 | mucA | Sigma factor algU negative regulatory protein | 2.19 | |

| rsm sRNA | PSPTO_5647 | rsmY | sRNA | −3.12 |

| PSPTO_5671 | rsmX | sRNA | −2.23 | |

| PSPTO_5673 | rsmX-3 | sRNA | −8.02 | |

| PSPTO_5674 | rsmX-4 | sRNA | −3.54 | |

| Sulfur uptake and regeneration | PSPTO_0203 | Cysteine synthase | −2.04 | |

| PSPTO_0308 | sbp | Sulfate binding protein | 8.20 | |

| PSPTO_0309 | cysT | Sulfate ABC transporter | 2.73 | |

| PSPTO_0310 | Sulfate ABC transporter | 3.13 | ||

| PSPTO_0311 | cysA | Sulfate/thiosulfate import ATP binding protein | 3.21 | |

| PSPTO_1793 | Uncharacterized protein | 2.83 | ||

| PSPTO_1795 | Alkanesulfonate monooxygenase | 2.41 | ||

| PSPTO_1796 | Sulfonate ABC transporter | 2.43 | ||

| PSPTO_1797 | Aliphatic sulfonates import ATP binding protein | 2.27 | ||

| PSPTO_2614 | Dioxygenase, TauD/TfdA family | 2.31 | ||

| PSPTO_3438 | iscS-3 | Cysteine desulfurase | 3.53 | |

| PSPTO_3451 | ssuE | Flavin mononucleotide reductase, NADH dependent | 34.00 | |

| PSPTO_3466 | ssuD | Alkanesulfonate monooxygenase | 15.76 | |

| PSPTO_4161 | Glutaredoxin | −2.04 | ||

| PSPTO_5187 | metQ-1 | d-Methionine binding lipoprotein | 12.99 | |

| PSPTO_5188 | metN-1 | Methionine import ATP binding protein | 7.68 | |

| PSPTO_5189 | metI-1 | d-Methionine ABC transporter | 5.76 | |

| PSPTO_5198 | Dioxygenase, TauD/TfdA family | 11.10 | ||

| PSPTO_5312 | tauC | Taurine ABC transporter | 3.29 | |

| PSPTO_5314 | Aliphatic sulfonate import ATP binding protein | 17.20 | ||

| PSPTO_5315 | ssuC | Aliphatic sulfonate ABC transporter | 18.16 | |

| PSPTO_5316 | Sulfonate ABC transporter | 16.76 | ||

| PSPTO_5319 | tauA | Taurine ABC transporter | 3.74 | |

| PSPTO_5320 | tauB | Taurine import ATP binding protein | 3.02 | |

| Quorum sensing | PSPTO_2048 | Transcriptional regulator, LuxR family | −4.12 | |

| PSPTO_2590 | Bacterial luciferase family protein | −4.12 | ||

| PSPTO_5548 | DNA binding response regulator, LuxR family | −11.62 |

Locus number of differentially expressed gene.

Gene name of differentially expressed gene (if applicable).

Putative functional description of gene product or sRNA as listed in the InterPro database (96).

Fold change of gene expression between the ΔcvsR strain and the WT according to RNA-seq data.

TABLE 2.

Genes in the CvsR primary regulon

| Nearest gene IDa | Gene nameb | Descriptionc | Fold changed |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSPTO_0203 | Cysteine synthase | −2.04 | |

| PSPTO_0279 | Uncharacterized protein | −2.62 | |

| PSPTO_1062 | Uncharacterized protein | −2.52 | |

| PSPTO_1304 | Uncharacterized protein | −6.23 | |

| PSPTO_1609 | Uncharacterized protein | −3.10 | |

| PSPTO_1626 | Uncharacterized protein | 2.11 | |

| PSPTO_2809 | Uncharacterized protein | 2.10 | |

| PSPTO_3086 | Transcriptional regulator | 11.29 | |

| PSPTO_3288 | Uncharacterized protein | 6.13 | |

| PSPTO_3289 | Uncharacterized protein | 3.83 | |

| PSPTO_3318 | Beta-glucosidase | 2.53 | |

| PSPTO_3582 | katB | Catalase | 2.86 |

| PSPTO_4631 | Sensory box/GGDEF domain/EAL domain protein | −3.07 | |

| PSPTO_5255 | cynT | Carbonic anhydrase | −23.64 |

| PSPTO_5256 | Sulfate transporter family protein | −9.02 | |

| PSPTO_5312 | Conserved domain protein | 3.78 | |

| PSPTO_5316 | Sulfonate ABC transporter | 16.76 | |

| PSPTO_5319 | tauA | Taurine ABC transporter | 3.74 |

| PSPTO_5466 | Uncharacterized protein | −2.71 | |

| PSPTO_t37 | tRNA-Cys-1 gene | tRNA-Cys-1 | −2.21 |

Nearest gene ID downstream of a ChIP-seq peak.

If applicable.

Putative functional description of gene product as listed in the UniProt database (97).

Fold change of gene expression between the ΔcvsR strain and the WT according to RNA-seq data.

CvsSR regulates expression of algU.

RNA-seq results showed a greater-than-2-fold increase in expression of algU, mucA, and mucB in the ΔcvsR strain. In addition, 94 genes previously reported to be part of the AlgU regulon are shared with the CvsR regulon (15). Of these 94 genes, 77 displayed the same expression profile in an algU-overexpressing strain and in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT. Notably, genes involved in alginate production, including algD, showed increased expression in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT. The ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains grown on NB agar supplemented with Ca2+ showed a significant increase in alginate production after 12 h of growth compared to the WT but not when grown on NB agar (Fig. 4A; see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). This provides additional confirmation that CvsSR regulates expression of genes involved in alginate production and that AlgU is active in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains. Since deletion of cvsR resulted in increased algU expression compared to the WT and CvsS and CvsR regulate alginate production, we conclude that CvsSR indirectly regulates expression of algU in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000.

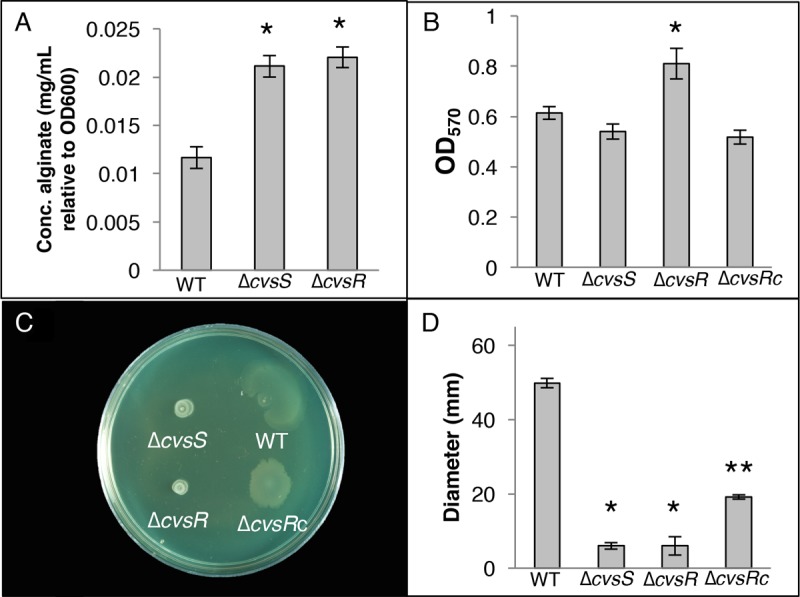

FIG 4.

Assays assessing phenotypic changes in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains compared to the WT. (A) Amount of alginate present in the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 when grown on NB agar supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 for 12 h. This assay was performed three times. * denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.01 between the WT and the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains, was determined using Student's two-tailed t test. (B) Biofilm formation by the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains grown in MG (pH 7.0) with 2 mM CaCl2 visualized using absorbance of crystal violet at 570 nm. The error bars represent the standard deviation between the replicates. This assay was repeated three times. * denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.05 between the WT and the ΔcvsR strain, determining using Student's two-tailed t test. (C) Swarming assays of the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains grown on medium with 5 mM CaCl2. Pictures of swarming assays were taken a day after spotting. (D) Diameter of swarming colonies measured 24 h after spotting on NB with 5 mM CaCl2. The experiment was performed three times with three replicates per experiment. Diameters of colonies were measured across two locations and averaged. Error bars represent standard deviation between replicates. * denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.01 in swarming diameter between the WT and the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains, determined using Student's two-tailed t test. ** denotes a statistically significant difference with a P value of <0.01 in swarming diameter between the ΔcvsR and ΔcvsRc strains.

CvsSR regulates bacterial cell attachment and motility.

Expression of genes involved in flagellar motility decreased in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT, and several genes involved in quorum sensing were also differentially expressed in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT (Table 1). In Pseudomonas, biofilm formation and swarming motility can be impacted by changes in alginate production, flagellar biosynthesis, and quorum-sensing genes (42–44). Biofilm assays were performed in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+. The ΔcvsR strain, but not the ΔcvsS strain, showed a significant increase in attachment compared to the WT (Fig. 4B). Swarming motility of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains was reduced compared to the that of WT when Ca2+ was added to swarming medium but not on standard swarming medium (Fig. 4C and D; see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material). This phenotype was partially complemented in the ΔcvsRc strain (Fig. 4C and D). It should be noted that the ΔcvsRc strain was unable to swarm as well as the WT on swarming medium and on swarming medium supplemented with Ca2+ (Fig. 4D and S8). Swimming assays were performed to determine whether the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains had decreased flagellar motility compared to the WT and whether decreased flagellar motility explained the decreased swarming in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains. No difference in swimming motility was found between the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains and the WT, suggesting that the decreased swarming motility exhibited by the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains was likely not due to decreased flagellar motility (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). To see if decreased swarming was due to overproduction of alginate, we compared swarming from a ΔalgD P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain with that from ΔcvsS ΔalgD and ΔcvsR ΔalgD P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains. Swarming was significantly reduced in the ΔcvsS ΔalgD and ΔcvsR ΔalgD P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains compared to the ΔalgD strain when grown on swarming medium supplemented with Ca2+ (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material). This suggests that CvsSR regulates swarming motility and possibly biofilm formation when Ca2+ is present through a mechanism other than flagellar motility and alginate production.

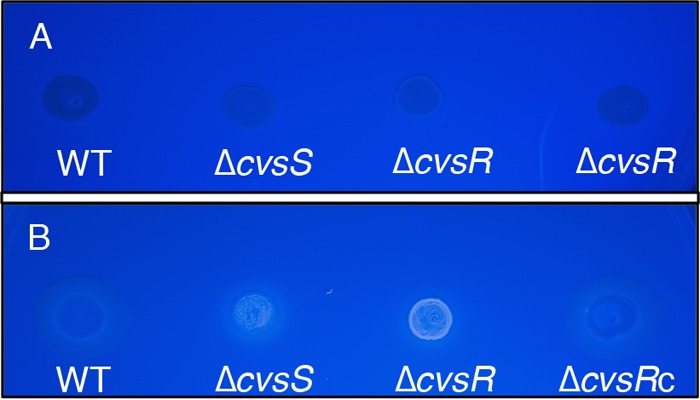

CvsSR regulates cellulose production in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000.

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 has the capability of producing the EPSs Psl, cellulose, and levan along with alginate (5). Psl and cellulose can inhibit swarming in P. syringae (45, 46). The genes PSPTO_3529 to PSPTO_3539, which code for proteins that produce Psl, were not differentially expressed between the WT and the ΔcvsR strain, nor was there a ChIP-seq peak near these genes. In addition, no difference was found in the amount of Psl between the WT and ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains through the use of a Psl-specific antibody (data not shown) (47), suggesting that the ΔcvsR strain and the ΔcvsS strain produce the same amount of Psl as the WT. Like the case for Psl, none of the genes that code for the cellulose biosynthetic gene cluster showed differential expression between the ΔcvsR strain and the WT in the RNA-Seq data. However, changes in cellulose production can occur even if gene expression for cellulose biosynthesis genes do not show differential expression between two strains, since cellulose is posttranscriptionally regulated in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (48). In order to test for changes in cellulose production, the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains were grown on NB medium supplemented with Ca2+ and calcofluor white (CW). CW is a dye that fluoresces when it binds beta-1,4 glycosyl linkages, and it is commonly used to visualize cellulose production in microbes (48). After 3 days of growth on NB medium supplemented with Ca2+ and CW, the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains fluoresced but the WT and the ΔcvsRc strain did not (Fig. 5). In contrast, the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains did not fluoresce on NB medium supplemented only with CW after 3 days of growth (see Fig. S11 in the supplemental material). From this we conclude that CvsSR regulates cellulose production in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 when Ca2+ is present in the medium.

FIG 5.

Growth of the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc strains on NB supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 and CW after 16 h (A) and 3 days (B) of growth. Fluorescence of the bacterial strains under UV light indicates production of cellulose. Bacterial strains were grown to stationary phase in KB medium and resuspended at an OD600 of 0.3 in NB medium, and then 5 μl of each culture was spotted onto the appropriate medium. The plate is representative of assays that were performed three times.

CvsSR regulates expression of several T3SS-related genes.

ChIP-seq data showed that hrpR and the effectors hopAT1, hopAD1, hopAO1, avrPtoB, hopG1, hopD1, and hopAA1 had a CvsR binding site upstream of the gene or within the gene itself, suggesting that CvsSR regulates expression of several T3SS genes. A binding site for CvsR was also found upstream of PSPTO_4966, a recently identified member of the HrpL regulon (9). Two recently discovered HrpL-regulated genes, PSPTO_2129 and PSPTO_2130, were the only HrpL-regulated genes differentially expressed between the ΔcvsR strain and the WT strain at a fold change cutoff of 2-fold (9, 10). If the fold change cutoff for differentially expressed genes was lowered to 1.7-fold or more, hopG1 showed increased expression and the pseudogene hopAT1 showed decreased expression in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT. Both genes are part of the HrpL regulon. We also observed decreased expression of hopAH2-1 in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT. HopAH2-1 is thought to be secreted through the T3SS but is not regulated by HrpL (49). From these data, we conclude that CvsR binds near several T3Es and directly regulates at least two T3Es.

Although differential expression of hrpRS was not observed in the RNA-seq data, we investigated whether we could detect differences in expression of hrpRS between the ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and WT strains using a reporter gene construct that contained 800 bp upstream of hrpR (PhrpRS). This reporter gene construct included both CvsR binding sites and should report expression of both hrpR and hrpS (14). PhrpRS showed a significant decrease in expression in both the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains compared to the WT when grown in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+ but not when grown in MG medium (Fig. 6A; see Fig. S12A in the supplemental material). Since hrpRS regulates expression of hrpL, it was possible that there was also a difference in hrpL expression in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains compared to the WT. Therefore, we transformed the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains with the vector pBS63, which includes a promoter fusion previously used to measure expression of PhrpL (50). A significant difference in expression of PhrpL in the WT compared to the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains was seen when strains were grown in MG medium supplemented with Ca2+ but not when they were grown in MG medium (Fig. 6B and S12B). Since decreased expression of hrpRS and hrpL could reduce production of the T3SS and deployment of T3Es, we then tested the hypersensitive response (HR) in Nicotiana tabacum and Nicotiana benthamiana to see if the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains would elicit the HR at the same level as the WT. We found no difference in the HR for N. tabacum or N. benthamiana when infiltrated with the ΔcvsS or ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT (see Fig. S13 in the supplemental material). Even though CvsSR regulates hrpRS and hrpL, these data suggest that CvsSR does not affect production of the T3SS or overall deployment of the T3Es during growth in planta.

FIG 6.

Luminescence assay to assess activity of PhrpRS (A) and PhrpL (B) in the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains when grown in MG supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2. The relative luminescence was calculated using the total luminescence relative to OD600. For PhrpRS, the experiment was performed three times with three independent replicates per experiment, and for PhrpL, the experiment was performed seven times with three independent replicates per experiment. The experiments for each reporter gene construct were compiled using a least-squares mean regression. The error bars represent standard error generated by the differences observed between samples. * denotes statistically significant differences determined using a Tukey HSD test with a P value of <0.01 between relative luminescence of the WT, ΔcvsS, and ΔcvsR strains. † denotes statistically significant differences determined using a Tukey HSD test with a P value of <0.01 between the relative luminescence of the WT and ΔcvsR strains.

Ca2+ does not influence growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains in planta.

The ΔcvsR strain demonstrated increased expression of catalase and genes related to methionine uptake as well as decreased expression of some thiol biosynthesis-related genes (Table 1). Similar gene expression patterns were seen in Escherichia coli during treatment with toxic levels of homocysteine and in E. coli treated with antimicrobial peptidoglycan recognition proteins (51, 52). This suggests that the bacteria are under distress when grown in a Ca2+-supplemented medium. In fact, growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains was reduced during stationary-phase growth when Ca2+ was added to medium (see Fig. S14 in the supplemental material). This concurs with the RNA-seq data and suggests that the ΔcvsR strain is under duress when Ca2+ is present in media in vitro. Since the leaf apoplast is abundant in Ca2+, we questioned whether the observed decreases in virulence and growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains in planta are a result of the concentration of Ca2+ in the apoplast. Deleting the T3SS in addition to cvsS or cvsR should result in an additive loss of growth in tomato leaves if the concentration of Ca2+ in the apoplast was the primary cause for the reduced growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains when inoculated in plants (53). The ΔhrcQb-U P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain no longer produces a T3SS and has been used to look at P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000-host interactions when it can no longer deliver effectors (54). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 ΔhrcQb-U, ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsS, and ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsR were syringe infiltrated into tomato leaves. Growth of all of the strains at 4 dpi was similar to that at 6 dpi (see Fig. S15 in the supplemental material). This suggests that the concentration of Ca2+ in the apoplast does not adversely affect growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains.

DISCUSSION

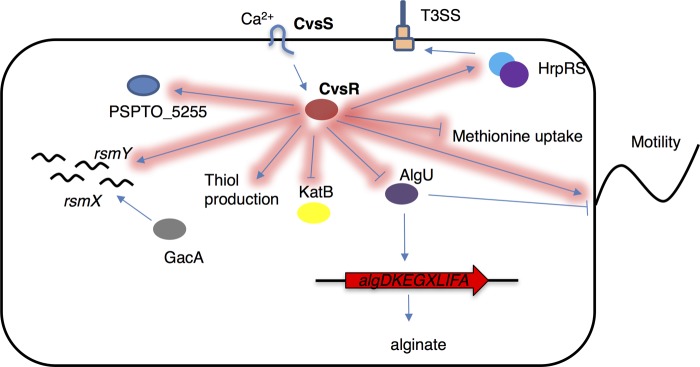

The results here identify and characterize CvsSR as a virulence-associated TCS that is induced by Ca2+ in vitro and in planta. Through the use of ChIP-seq and RNA-seq, we discovered that CvsSR impacts expression of two main regulators of pathogenicity, algU and hrpRS. Our results highlight and emphasize the importance of Ca2+ as a signal used by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 during pathogenesis and show that the TCS CvsSR is a key player in the regulation of genes important for full virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Fig. 7).

FIG 7.

A partial regulon of CvsR in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Arrows highlighted in red are part of the CvsR regulon.

Mechanisms by which P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 senses and responds to Ca2+ were previously unknown. Several TCSs that either sense or are induced by Ca2+ have previously been characterized in other bacteria. The histidine kinase PhoQ in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium binds to Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ and regulates several virulence factors (55). CarSR in Vibrio cholerae is induced by Ca2+ and negatively regulates biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide production (31). In P. aeruginosa PAO1, the TCS orthologous to CvsSR, BqsSR, is also induced by Ca2+ and regulates the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (38). However, to our knowledge, CvsSR is the first Ca2+-induced TCS characterized in a hemibiotrophic plant-pathogenic bacteria. Thus, Ca2+ can now be added to the list of environmental cues that P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 uses during pathogenesis.

According to ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data, CvsR directly promotes expression of several genes, including PSPTO_5255, PSPTO_1304, and PSPTO_1609, and directly represses expression of several genes, including katB and tauA (Table 2). Response regulators within the OmpR family can act as both transcriptional activators and repressors. OmpR in E. coli reciprocally regulates ompF and ompC depending on the osmotic conditions of the environment (56). CpxR in E. coli promotes expression of marR and represses expression of ung (57, 58). CvsR appears to be similar in its ability to promote and repress expression of different genes.

CvsR regulates transcription of algU, and the regulons of CvsR and AlgU have noticeable overlap (15). It is currently unclear how CvsR transcriptionally regulates algU in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Most characterized negative regulation of algU in Pseudomonas occurs posttranscriptionally through RsmA or posttranslationally through MucA and MucB (59, 60). Indirect repression of algU by CvsR would add another layer of regulatory control over algU that was previously unknown. Even with decreased expression of several rsm sRNAs and increased expression of mucA and mucB in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT, AlgU was still active in the ΔcvsR strain (Table 1). One explanation for this phenomenon is that activity of RsmA, MucA, and MucB can be repressed posttranslationally through various mechanisms. Posttranslational repression would not be captured through ChIP-seq or RNA-seq. This could result in reduced activity of these proteins even if there was increased transcription. In the case of MucA, AlgW degrades MucA in P. aeruginosa, and something similar could be occurring in the ΔcvsR strain (60). For RsmA, rsmZ and the rsmX paralogs not regulated by CvsR could sequester RsmA in the ΔcvsR strain even when the other rsm sRNAs are not abundant. Further characterization of CvsR-based algU regulation is necessary to discern the exact mechanism.

AlgU regulates expression of genes involved in osmoadaptation, ROS detoxification, alginate biosynthesis, and pathogenicity in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (15). Interestingly, and somewhat contradictory to reported results showing that overexpression of algU increases virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, the ΔcvsR strain was less virulent than the WT on tomato plants even though it showed an increase in expression of algU compared to the WT. Overexpression of algU in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 resulted in increased expression of cvsS and cvsR (15). Both cvsS and cvsR are directly regulated by CvsR. Even though we observed upregulation of algU in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT, we did not observe an accompanied upregulation of cvsS and cvsR in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT. It is possible that upregulation of cvsS and cvsR is critically involved in AlgU-related virulence. One might speculate that upon deletion of cvsR, algU overexpression may no longer positively regulate virulence because upregulation of cvsSR no longer occurs.

Biofilm formation and swarming motility are typically antagonistic, with only rare examples of these lifestyles being sympathetic (61). In our study, CvsR appears to regulate biofilm formation and swarming motility in the typical antagonistic way. However, this was not the case with CvsS. The orthologous TCS, BqsSR, in P. aeruginosa PAO1 positively regulates biofilm dispersal when P. aeruginosa PAO1 is grown in LB (62). However, when grown on BM2 agar supplemented with 10 mM CaCl2, swarming motility was not reduced upon deletion of bqsSR (38). As such, while each assay was performed under different conditions, it appears that BqsSR regulates biofilm lifestyle and swarming motility in a sympathetic way in P. aeruginosa PAO1. While BqsSR and CvsSR are considered to be orthologous TCSs, they may not function in entirely the same way, and regulation of swarming motility may be an area where these TCSs differ.

Increased EPS production, decreased flagellar motility, and decreased biosurfactant production all result in decreasing swarming motility in P. syringae (45, 63). It should be noted that we did not investigate whether changes in biosurfactant production occur in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 upon deletion of cvsS or cvsR. However, we did investigate whether changes in EPS production or flagellar motility reduced swarming in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains. We ruled out overproduction of alginate as a possible explanation for decreased swarming motility in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains (see Fig. S10 in the supplemental material), and there is no clear evidence that the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains overproduce Psl EPS. It has been reported that increased cellulose production affects swarming motility in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (64). We feel that this cannot fully explain the reduced swarming observed in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains, since it takes a substantial amount of time to observe noticeable differences in cellulose production in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains compared to the WT. Cellulose production commonly correlates with increased c-di-GMP in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (45, 65). Increases in c-di-GMP decrease swarming motility in Pseudomonas (66). Although outside the scope of this work, c-di-GMP concentrations in the ΔcvsR strain and the WT may differ. Current evidence also suggests that decreased swarming motility is not due to decreased flagellar motility, since swimming is not compromised in the ΔcvsR strain. However, the ability to swim is not always reflective of proper flagellar function, as several chemotaxis proteins and flagellar motors are necessary for swarming but not for swimming in P. aeruginosa (67, 68). Genes that code for six putative chemotaxis proteins and the rotary flagellar motor protein MotY are downregulated in the ΔcvsR strain compared to the WT (Table 1). Therefore, it is possible that downregulation of these genes could reduce swarming without reducing swimming. Further investigation into the role CvsSR plays in swarming is currently being pursued.

CvsR is, to our knowledge, the first direct transcriptional activator of hrpRS identified in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. The conservation of TCSs orthologous to CvsSR in other P. syringae pathovars opens the possibility of a conserved hrpRS transcriptional activator across pathovars (35). Disruption in hrpRS expression in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 through either deletion of hrpRS or deletion of an hrpRS indirect regulator, such as GacA, resulted in loss of the HR (14). One curiosity about CvsSR is that deletion of cvsS or cvsR does not disrupt the HR. Baseline expression of hrpR and hrpS still occurs when cvsS or cvsR is deleted. From these data, it is likely that CvsSR tunes expression of hrpRS. It is not uncommon for TCSs to tune expression of genes. For example, in Salmonella enterica, PhoPQ tunes expression of the effector steA during osmotic stress, and PhoBR tunes expression of itself in E. coli according to environmental phosphate concentrations (69, 70). If CvsSR tunes expression of hrpRS, then it is conceivable that deletion of cvsS or cvsR may cause only subtle changes T3SS and T3E deployment that do not affect the HR but could still influence pathogenesis.

The exact mechanism by which CvsSR is involved in virulence remains elusive. The growth assay of the ΔhrcQb-U, ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsS, and ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsR strains in tomato brought us to believe that the concentration of Ca2+ in the apoplast did not adversely affect growth of the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains in planta. Decreased growth accompanied with decreased virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, as seen in the ΔcvsS and ΔcvsR strains when assayed for virulence on tomato plants and A. thaliana, could be indicative of increased susceptibility of these strains to the plant immune response or a defect in phytotoxin or T3E deployment in these strains. Decreased spread of chlorotic symptoms by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 commonly occurs as a result of changes in T3Es or coronatine production (71–73). While we have not investigated whether CvsSR regulates coronatine production in P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000, CvsR does bind upstream of several T3Es within the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome. It is possible that regulation of these T3Es by CvsSR in planta plays a role in the reduced chlorosis and loss of necrotic specks observed in the plants inoculated with the ΔcvsS or the ΔcvsR strain. HopAA1-1 is directly regulated by CvsR and is necessary for chlorosis and production of necrotic specks in tomato plants (71). HopG1 is also directly regulated by CvsR and is another T3E that is necessary for chlorosis (74). CvsR also positively regulates expression of the gene fliC, which codes for flagellin. Flagellin is a major pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that triggers a defense response called PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) in plants (75). This means that deletion of CvsSR could result in less production of a major PAMP by P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Decreased expression of PAMPs can recover growth of certain effector-depleted P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants (76). With the regulon of CvsR, including hrpRS, several T3Es, and fliC, CvsR regulates multiple components involved in virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Characterization of the CvsSR regulon in planta could provide a clearer picture of how CvsSR regulates each of these factors during endophytic growth and how they synergistically affect virulence of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The primers and bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Tables S2 and S3, respectively, in the supplemental material. Escherichia coli DH5α and E. coli TOP10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were used for cloning. E. coli BL21(DE3) was used for expressing proteins. E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or Terrific broth (TB) medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics when necessary. P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 was routinely cultured on King's B (KB) agar (77). For select assays, strains were grown in MG medium (10 g mannitol, 2.5 g l-glutamate, 0.2 g MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.5 g KH2PO4, and 0.2 g NaCl per liter) at the specified pH (36).

Creation of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 mutants.

Unmarked deletion strains were constructed using plasmid pK18mobsacB (78). DNA fragments of approximately 1.1 kb upstream and 1.0 kb downstream of cvsS (PSPTO_3380) and cvsR (PSPTO_3381) were amplified by PCR, gel purified, and then joined by splicing by overlap extension PCR. These products were then gel purified using a gel extraction miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and cloned into pK18mobsacB using EcoRI (New England BioLabs [NEB], Ipswich, MA) and BamHI (NEB). The pK18mobsacB deletion constructs were confirmed by sequencing at the Biotechnology Resource Center of Cornell University before introduction into WT, ΔhrcQb-U, or ΔalgD P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 via electroporation. Integration events were selected on KB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Colonies were transferred to KB medium containing 10% sucrose to select for crossover events that resulted in the loss of the sacB gene. Sucrose-resistant colonies were screened by PCR, and clones containing the appropriate deletion(s) were confirmed by sequencing.

Complementation of the ΔcvsR strain.

The ΔcvsR complement was made using a pUC18miniTn7 vector (79). Briefly a genomic fragment containing cvsR, PSPTO_3382, and PSPTO_3383 was amplified via PCR. The products were gel purified using the Qiagen gel extraction miniprep kit (Qiagen), digested with HindIII (NEB) and PstI (NEB), and cloned into a pUC18miniTn7 plasmid which had been digested with HindIII and PstI. The resulting ligation was transformed into DH5α E. coli cells. The ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain was transformed through electroporation with pUC18miniTn7::cvsR-3383 and the helper plasmid pTNS2. Colonies were selected by plating on KB supplemented with 10 μg/ml gentamicin. Positive clones were confirmed through sequencing.

Creation of a CvsR-FLAG-tagged strain.

The CvsR-FLAG-tagged strain was made using pBS46 (80). Briefly, the sequence for a FLAG tag was added to the 3′ end of cvsR (cvsR-FLAG) using PCR amplification. The PCR product was gel extracted using the Zymoclean gel extraction kit (Zymo, Irvine, CA) and then cloned into a pENTR/SD/TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transformed into Top10 E. coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Positive clones for pENTR/SD/TOPO::cvsR-FLAG were selected by plating on LB supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin agar plates and confirmed through sequencing. cvsR-FLAG was moved to from the pENTR/SD/TOPO entry vector to a vector containing an nptII promoter, pBS46, using the LR reaction (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transformed into TOP10 E. coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Positive clones were selected on LB agar plates supplemented with 10 μg/ml gentamicin and confirmed through sequencing. ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 was then transformed with pBS46::cvsR-FLAG and selected on KB agar plates supplemented with 10 μg/ml gentamicin.

Luciferase reporter assays.

Four hundred base pairs upstream of PSPTO_3383 (PcvsSR) and 850 bp upstream of hrpR (PhrpRS) were PCR amplified. The PCR products were purified using a Qiagen PCR purification kit (Qiagen), cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO vectors (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and transformed into TOP10 E. coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Positive clones and constructs for pENTR/D/TOPO::p3383 and pENTR/D/TOPO::phrpR were generated, selected, and transformed into appropriate strains of P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 as previously described (81).

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown on KB plates and transferred to MG medium (pH 6.0) or apoplastic washing fluid (AWF) at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1; 5 mM CaCl2 or 5 mM EGTA was added to the cultures when appropriate. Strains were grown in 96-well plates (Nunc) at 28°C with shaking in a Biotek Synergy II microplate reader (Winooski, VT). OD600 and luminescence measurements were taken every 2 h. Relative luminescence measurements were normalized to OD600. The assays were repeated three times, and sampling was conducted in triplicate. Averages and standard deviations were generated from each experiment. Statistical significance was determined by performing a least-squares mean regression on the combined biological replicates.

Extraction of AWF.

A procedure used to extract apoplastic washing fluid (AWF) from bean plants was used to extract AWF on 3- to 4-week-old Solanum lycopersicum cv. Moneymaker plants (82). After extracting AWF, samples were analyzed for cellular contamination by testing for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and maltose dehydrogenase activity using a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity assay kit (Sigma) and a maltose dehydrogenase activity assay kit (Sigma). AWF was then lyophilized and resuspended to an equivalent undiluted state.

ICP-MS.

AWF was diluted 4-fold and 80-fold, depending on the element being examined, in double-deionized water (ddH2O) and analyzed on an iCap Q inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Standards for calcium, potassium, zinc, sulfur, iron, cadmium, magnesium, and phosphorus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were included for each sample tested.

Tomato virulence assays.

Three- to 4-week old Solanum lycopersicum cv. Moneymaker plants were inoculated with the WT, ΔcvsS, ΔcvsR, and ΔcvsRc P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains at 2 × 107 CFU/ml through dip inoculation as was previously described (83). To assay the ΔhrcQb-U, ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsS, and ΔhrcQb-U ΔcvsR strains, 3- to 4-week-old Solanum lycopersicum cv. Moneymaker plants were inoculated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains at 1 × 106 CFU/ml using a blunt-tipped syringe. Time points for growth of the bacteria (in CFU/mg) were 4 and 6 days postinoculation (dpi). The experiment was repeated three times, and three technical replicates were performed for each experiment. Averages and standard deviations were generated for growth of bacteria for each experiment. Student's two-tailed t test was used to determine statistical significance between growth of different strains.

A. thaliana virulence assays.

A. thaliana was grown and inoculated as previously described (84). Plants were dipped in a bacterial suspension at 3 × 104 CFU/ml and vacuum infiltrated at 20 mm Hg. Symptoms were observed at 4 and 6 dpi, and growth of the bacteria (CFU/mg) was measured at 4 and 6 dpi. The experiment was repeated three times, and three replicates were used during each experiment. Averages and standard deviations were generated for growth of bacteria for each experiment.

HR assays.

Three- to 4-week-old N. tabacum cv. xanthi or N. benthamiana plants were syringe infiltrated with P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 at 2 × 106, 2 × 107, and 2 × 108 CFU/ml (85). The hypersensitive response (HR) was observed 1 and 2 dpi. Pictures were taken at 2 dpi. This experiment was repeated three times with three technical replicates for each biological replicate.

ChIP and preparation of DNA for ChIP-seq.

The ΔcvsR P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strain complemented with pBS46::cvsR-FLAG was grown overnight in KB medium to stationary phase, and 200 μl of the culture was plated on NB (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lake, NJ) medium supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium succinate hexahydrate (Sigma). After 18 h of growth at 28°C, the cells were scraped from the plates using a sterile slide, resuspended in NB medium with 1% formaldehyde, and then processed as described previously (37).

qPCR.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on DNA from input and IP fractions on a CFX Connect (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using Sso Advanced SYBR green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Primers upstream of PSPTO_3383 were used to determine enrichment for predicted targets of CvsR in the IP fraction. Enrichment of these areas was determined relative to regions in the gene gyrA (37).

Analysis of ChIP-seq data.

Sequenced reads from three separate MiSeq runs were first compiled and then analyzed. Sequencing reads were trimmed using the FASTX toolkit (version 0.0.14) and the UTILS toolkit (release tag 822) (86). Bowtie2 2.2.6 was used to align sequencing reads to the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome (87). Ambiguous reads were removed using a custom script as previously described (88). MACS version 2.1.0.20140616 was used to identify regions of enrichment in the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome from the IP sample using the following parameters: macs2 callpeak −t CHIP_FILE –c CONTROL_FILE, −seed 1 −g 6.1e6 −fix-bimodal\, and −keep-dup all −q 0.0.5. Several peaks were called within cvsR. Since these were likely artifacts due to overexpression of cvsR during the ChIP-seq experiment, they were disregarded.

CvsR binding motif generation.

Regions 50 bp up- and downstream of called peaks were identified. Any regions that overlapped were merged. These regions were then compiled, and motif discovery was performed using MEME version 4.10.0 patchlevel 1 with the following parameters (89): −revcomp −nmotifs 3 −minw 6 −maxw 50\, −minsites 2 −maxsites NUMBER_OF_INPUT_SEQUENCES, and −mod zoops.

RNA extraction and RNA-seq cDNA library preparation.

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown overnight in KB medium to stationary phase, and 200 μl of these cultures was plated and spread on NB medium with 5 mM CaCl2 supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium succinate hexahydrate. The cultures were allowed to grow for 18 h at 28°C, and then RNA was extracted using the Direct-zol kit (Zymo). rRNA was then extracted using Ribo-zero for Gram-negative bacteria (Illumina, Madison, WI) as previously described (88). cDNA libraries were made using Scriptseq V.2 according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 at the Cornell Core Facility.

Analysis of RNA-seq data.

Sequenced reads were first trimmed using fastq-mcf (release tag 1.04.807) and then aligned to the P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genome using Bowtie2 2.2.6 (87). Ambiguous reads were removed as previously described (88). Next, a list of regions to be considered for differential analysis was constructed as previously described (15).

qRT-PCR.

Extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the qScript cDNA Supermix (Quanta, Gaithersburg, MD). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a Bio-Rad CFX Connect using Sso Advanced SYBR green Supermix. The reference gene gyrA was used to normalize expression between samples (90). Experiments were performed three times. Averages and standard deviations from each biological replicate were generated from the experiments.

RT-PCR.

Extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the iScript cDNA Supermix (Bio-Rad). In addition, a control with no reverse transcriptase was made using extracted RNA as well. RT-PCR was performed on P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genomic DNA, cDNA, and an RNA control without reverse transcriptase on a Bio-Rad T100 thermocycler using OneTaq (NEB). PCR products were then run on an agar gel and visualized using a ChemiDoc transilluminator (Bio-Rad). RT-PCR experiments were performed three times on three biological replicates.

Overproduction and purification of CvsR.

The cvsR gene was amplified with Phusion (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using primers oMRF0355 and oMRF0356 and P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genomic DNA as a template. Amplified cvsR was cloned into pET21 using NotI and SpeI (NEB) to make pET21::cvsR (pMRF21). pMRF21 was transformed into BL21(DE3) E. coli cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transformed cells were grown at 37°C in 4 liters of LB medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml ampicillin to an OD600 of 0.8 before 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (Sigma) was added to the culture to induce expression. Cells were allowed to grow for another 4 h at 37°C and then pelleted and frozen at −80°C. Thawed cells were resuspended in wash buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8], 500 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol) and lysed through sonication. Insoluble material was removed through centrifugation, and the supernatant was applied to Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) Superflow agarose (Qiagen) using gravity column chromatography. CvsR was eluted off the agarose using elution buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8], 500 mM KCl, 100 mM imidazole, and 10% glycerol), dialyzed overnight into storage buffer (40.1 mM K2HPO4, 9.9 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.4], 300 mM KCl, 50% glycerol), and stored at −80°C.

EMSA.

6-Carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled probes were generated through PCR with OneTaq (NEB) using P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 genomic DNA as a template. Probes were gel purified using the Zymoclean gel DNA recovery kit (Zymo). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed with increasing concentrations of CvsR (0 nM to 500 nM). Labeled probes were incubated with CvsR in 20 μl of binding buffer [40.1 mM K2HPO4, 9.9 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), 15 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 10% glycerol, and 40 ng/μl poly(dI-dC) DNA (Thermo Fisher)] for 20 min at room temperature. The reaction mixtures were then added to 6% polyacrylamide gels (0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA [TBE], 29:1 acrylamide-bisacrylamide [Bio-Rad], 30% glycerol) and run at 215 V for 3 h on ice. Gels were visualized on a Typhoon 9400 image system (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA).

Nonradioactive DNase footprinting.

6-FAM-labeled probes were generated and purified in the same manner as for EMSA. DNase footprinting assays were performed with 1 to 4 μM CvsR. Labeled probes were incubated with CvsR in 20 μl of DNase footprinting buffer (15 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM KCl, 6 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 10% glycerol, 2.5 ng/μl salmon sperm DNA [Sigma], 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin [NEB]) for 20 min at room temperature, and then 0.001 U of DNase (NEB) was added to reaction mixtures and allowed to incubate for 2 min before a volume of DNase stop solution (20 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1% SDS, 200 mM NaCl) equal to that of the reaction mixture was added. Digested probes were purified using the Oligo Clean and Concentrator (Zymo). Results were analyzed as previously described (37). The locations of regions protected by CvsR were estimated by mapping the position of the binding site back to the genomic location of the probe using a LIZ500 ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The genomic locations of regions protected by CvsR were compiled, and motif discovery was performed on MEME version 4.11.3 (89) with the following parameters (89): −revcomp −nmotifs 3 −minw 4 −maxw 50 −mod zoops\.

Quantification of alginate.

P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown overnight in KB medium to stationary phase, and 200 μl of these cultures was plated and spread on NB agar or NB agar supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 plates. The cultures were grown at 28°C before being scraped off the plate and resuspended in 0.9% NaCl. Resuspended cells were pelleted by centrifugation, supernatant was removed, and alginate production was determined using the carbazole-borate method with sodium alginate (Sigma-Aldrich) as a standard (91).

Motility assays.

Swarming assays were performed using NB plates containing 0.5% (wt/vol) agar supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 when appropriate. P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown overnight in KB medium, and 5 μl of each culture was spotted on a swarming plate (92). Swarming zones were measured after plates were incubated for 24 h at room temperature. Student's two-tailed t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Swimming assays were performed using swimming plates (10 g tryptone, 5 g NaCl per liter) with 0.3% (wt/vol) agar and supplemented with 5 mM CaCl2 when appropriate (93). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown overnight in KB medium. Toothpicks were dipped into the overnight cultures grown to stationary phase in KB medium and inserted into the centers of the swimming plates (94). Diameters of bacterial zones were measured after plates were incubated for 48 h. Pictures of swimming zones were taken after 24 h of growth at room temperature.

Biofilm assays.

Biofilm assays were modified from a previously described protocol (95). P. syringae pv. tomato DC3000 strains were grown overnight at 28°C in KB medium, washed twice with MG medium, and then subinoculated into MG medium (pH 7.0) with 2 mM CaCl2 at an OD600 of 0.02. One hundred microliters of each bacterial suspension was grown in clear flat-bottom 96-well plates in a BioTek Synergy 2 microplate reader for 24 h at 28°C with shaking. Cultures were removed from the wells using a pipette, and then the wells were washed with double-distilled H2O (ddH2O). Following washing, wells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 10 min and washed twice with ddH2O. Stained biofilms were dissolved with 100 μl of 30% acetic acid, and the OD570 was recorded using a Biotek Synergy 2 microplate reader. Experiments were repeated three times. Four technical replicates of each strain were used during each experiment. Student's two-tailed t test was used to determine statistical significance.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 12.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kent Loeffler and Claire Smith for pictures used in this article. We thank Eric Craft and Shree K. Giri for running samples for ICP-MS. We thank Alan Collmer for reviewing the manuscript and providing helpful comments.

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purposes of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA.

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00538-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hirano SS, Upper CD. 1990. Population biology and epidemiology of Pseudomonas syringae. Annu Rev Phytopathol 28:155–177. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.28.090190.001103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltrus DA, Nishimura MT, Romanchuk A, Chang JH, Mukhtar MS, Cherkis K, Roach J, Grant SR, Jones CD, Dangl JL. 2011. Dynamic evolution of pathogenicity revealed by sequencing and comparative genomics of 19 Pseudomonas syringae isolates. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green S, Laue B, Fossdal CG, A'Hara SW, Cottrell JE. 2009. Infection of horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) by Pseudomonas syringae pv. aesculi and its detection by quantitative real-time PCR. Plant Pathol 58:731–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCann HC, Rikkerink EHA, Bertels F, Fiers M, Lu A, Rees-George J, Andersen MT, Gleave AP, Haubold B, Wohlers MW, Guttman DS, Wang PW, Straub C, Vanneste J, Rainey PB, Templeton MD. 2013. Genomic analysis of the kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae provides insight into the origins of an emergent plant disease. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003503. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buell CR, Joardar V, Lindeberg M, Selengut J, Paulsen IT, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Deboy RT, Durkin AS, Kolonay JF, Madupu R, Daugherty S, Brinkac L, Beanan MJ, Haft DH, Nelson WC, Davidsen T, Zafar N, Zhou L, Liu J, Yuan Q, Khouri H, Fedorova N, Tran B, Russell D, Berry K, Utterback T, Van Aken SE, Feldblyum TV, D'Ascenzo M, Deng W-L, Ramos AR, Alfano JR, Cartinhour S, Chatterjee AK, Delaney TP, Lazarowitz SG, Martin GB, Schneider DJ, Tang X, Bender CL, White O, Fraser CM, Collmer A. 2003. The complete genome sequence of the Arabidopsis and tomato pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:10181–10186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1731982100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill US, Lee S, Mysore KS. 2015. Host versus nonhost resistance: distinct wars with similar arsenals. Phytopathology 105:580–587. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-14-0298-RVW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xin XF, He SY. 2013. Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000: a model pathogen for probing disease susceptibility and hormone signaling in plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 51:473–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindeberg M, Stavrinides J, Chang JH, Alfano JR, Collmer A, Dangl JL, Greenberg JT, Mansfield JW, Guttman DS. 2005. Proposed guidelines for a unified nomenclature and phylogenetic analysis of type III Hop effector proteins in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18:275–282. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam HN, Chakravarthy S, Wei H-L, BuiNguyen H, Stodghill PV, Collmer A, Swingle BM, Cartinhour SW. 2014. Global analysis of the HrpL regulon in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 reveals new regulon members with diverse functions. PLoS One 9:e106115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira AO, Myers CR, Gordon JS, Martin GB, Vencato M, Collmer A, Wehling MD, Alfano JR, Moreno-Hagelsieb G, Lamboy WF, DeClerck G, Schneider DJ, Cartinhour SW. 2006. Whole-genome expression profiling defines the HrpL regulon of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000, allows de novo reconstruction of the Hrp cis clement, and identifies novel coregulated genes. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:1167–1179. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jovanovic M, James EH, Burrows PC, Rego FGM, Buck M, Schumacher J. 2011. Regulation of the co-evolved HrpR and HrpS AAA+ proteins required for Pseudomonas syringae pathogenicity. Nat Commun 2:177. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan L, Deng X, Zhou J, Tang X. 2006. Genome-wide gene expression analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 reveals overlapping and distinct pathways regulated by hrpL and hrpRS. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:976–987. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng X, Liang H, Chen K, He C, Lan L, Tang X. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of two-component system RhpRS regulating type III secretion system in Pseudomonas syringae. Nucleic Acids Res 42:11472–11486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee A, Cui Y, Yang H, Collmer A, Alfano JR, Chatterjee AK. 2003. GacA, the response regulator of a two-component system, acts as a master regulator in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 by controlling regulatory RNA, transcriptional activators, and alternate sigma factors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 16:1106–1117. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.12.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markel E, Stodghill P, Bao Z, Myers CR, Swingle B. 2016. AlgU controls expression of virulence genes in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. J Bacteriol 198:2330–2344. doi: 10.1128/JB.00276-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moll S, Schneider DJ, Stodghill P, Myers CR, Cartinhour SW, Filiatrault MJ. 2010. Construction of an rsmX co-variance model and identification of five rsmX non-coding RNAs in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. RNA Biol 7:508–516. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.5.12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong HS, Roberts DP, Patterson CD, Kuehne SA, Heeb S, Lakshman DK, Lydon J. 2012. Effect of overexpressing rsmA from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on virulence of select phytotoxin-producing strains of P. syringae. Phytopathology 102:575–587. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-11-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hershberger CD, Ye RW, Parsek MR, Xie ZD, Chakrabarty AM. 1995. The algT (algU) gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a key regulator involved in alginate biosynthesis, encodes an alternative sigma factor (sigma E). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:7941–7945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stael S, Wurzinger B, Mair A, Mehlmer N, Vothknecht UC, Teige M. 2012. Plant organellar calcium signalling: an emerging field. J Exp Bot 63:1525–1542. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Leary BM, Neale HC, Geilfus C-M, Jackson RW, Arnold DL, Preston GM. 2016. Early changes in apoplast composition associated with defence and disease in interactions between Phaseolus vulgaris and the halo blight pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. phaseolicola. Plant Cell Environ 39:2172–2184. doi: 10.1111/pce.12770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De La Fuente L, Parker JK, Oliver JE, Granger S, Brannen PM, van Santen E, Cobine PA. 2013. The bacterial pathogen Xylella fastidiosa affects the leaf ionome of plant hosts during infection. PLoS One 8:e62945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dominguez DC, Guragain M, Patrauchan M. 2015. Calcium binding proteins and calcium signaling in prokaryotes. Cell Calcium 57:151–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norris V, Chen M, Goldberg M, Voskuil J, McGurk G, Holland B. 1991. Calcium in bacteria: a solution to which problem? Mol Microbiol 5:775–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]