Peptidoglycan (PG), the major component of the bacterial wall, protects cells from mechanical stress resulting from high intracellular turgor. PG biosynthesis (Fig. 1a) is very similar in all bacteria. Therefore, different bacterial shapes are mainly determined by the spatial and temporal regulation of PG synthesis, not by its chemical composition. Rod-shaped bacteria, such as Bacillus subtilis or Escherichia coli, achieve their shape through the action of two PG synthesis machines that act at the septum and at the lateral wall, in processes coordinated by cytoskeletal proteins FtsZ and MreB, respectively 1,2. The tubulin homologue FtsZ is the first protein recruited to the division site where it assembles in filaments (Z-ring) that undergo treadmilling and recruit later divisome proteins3,4. Importantly, the rate of treadmilling in B. subtilis controls both the rate of PG synthesis and of cell division3. The actin homologue MreB forms discrete patches that move circumferentially around the cell, in tracks perpendicular to the cell long axis, and organise insertion of new cell wall during elongation5,6. Cocci like Staphylococcus aureus possess only one PG synthesis machinery7,8, which is diverted from the cell periphery to the septum in preparation for division9. The molecular cue that coordinates this transition has remained elusive. Here, we investigated the localisation of S. aureus PG biosynthesis proteins and showed that the putative lipid II flippase MurJ is recruited to the septum by the DivIB/DivIC/FtsL complex, driving PG incorporation to midcell. MurJ recruitment corresponds to a turning point in cytokinesis, which is slow and dependent on FtsZ treadmilling before MurJ arrival, but becomes faster and independent of FtsZ treadmilling after PG synthesis activity is directed to the septum, providing additional force for cell envelope constriction.

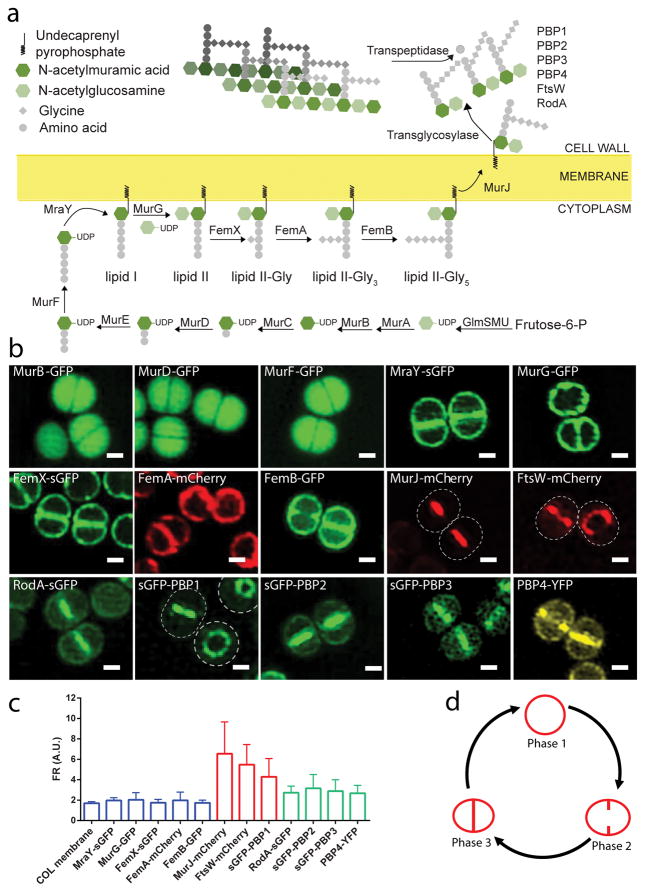

Figure 1. Localisation of PG synthesis proteins during division of Staphylococcus aureus.

a, Scheme of the peptidoglycan synthesis pathway in S. aureus. b, Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) images of S. aureus cells expressing fluorescent derivatives of PG synthesis proteins. Scale bars, 0.5 μm. Images are representative of three biological replicates. c, Fluorescence ratios (FR) between fluorescence signal at the septum versus the peripheral membrane measured in cells with a complete septum (Phase 3). Blue bars: membrane proteins with FR~2, similar to Nile Red staining of COL membrane, expected as the septum contains two membranes versus one in the cell periphery. Green bars: septal enriched proteins with 2.5<FR<3.5. Red bars: septal proteins with FR>4. Data are represented as column graphs where the height of the column is the mean and whiskers are standard deviation. N, from left to right: 439, 533, 516, 513, 512, 622, 503, 517, 503, 689, 1321, 488, 516 cells. d, Scheme of the S. aureus cell cycle. Phase 1 cells have not initiated septum synthesis; Phase 2 cells are undergoing septum synthesis; Phase 3 cells have a complete septum undergoing maturation in preparation for splitting.

The molecular cue that determines the shift of PG synthesis from the cell periphery to the septum in cocci could be the recruitment to midcell of a key PG biosynthesis protein, concomitantly with assembly of the divisome. Therefore, we examined the localisation of most S. aureus PG synthesis proteins in the background of Methicillin Resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain COL (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). All fluorescent fusions were functional (Supplementary Table 1) and expressed from their native locus under the control of their native promoter, as the sole copy of the gene in the cell, with the exception of MraY-sGFP. As expected MurB, MurD and MurF fusions, which act on cytoplasmic PG precursors, showed cytoplasmic localisation (Fig. 1b). Also consistent with their substrate localisation, the remaining fusions localised to the membrane, including the FemXAB proteins, which do not have canonical membrane-targeting domains10. Since most PG synthesis activity occurs at the septum9, we were expecting membrane-associated PG synthesis enzymes to be highly enriched in the septal region of dividing cells. However, MraY, MurG, and the FemXAB proteins were evenly distributed throughout the membrane (including the septum) suggesting that the key step for spatial regulation of PG synthesis was not the synthesis of lipid I or lipid II (Fig. 1b,c). MurJ, FtsW and PBP1 were the only septal proteins for which virtually no signal could be observed in the peripheral membrane during septum synthesis (Fig. 1b,c) and therefore were good candidates to catalyse the first specifically septal PG synthesis step. MurJ is a member of the MOP (multidrug/oligosaccharidyl-lipid/polysaccharide) exporter superfamily and has been suggested to be the lipid II flippase in E. coli11. In S. aureus the essential gene SAV1754 (aka SACOL1804) has been reported as a functional MurJ ortholog12. FtsW is a member of the SEDS (sporulation, elongation, division and synthesis) protein family, also suggested to be a lipid II flippase13. However, more recently, SEDS proteins were shown to be PG transglycosylases that probably function together with a cognate Penicillin-Binding Protein (PBP) during PG polymerisation14,15. S. aureus encodes two SEDS proteins, SACOL1122 and SACOL2075, similar to B. subtilis FtsW and RodA, respectively. PBP1 is a transpeptidase that crosslinks PG glycan strands16.

In order to clarify which protein(s) was responsible for directing PG synthesis to the septum, newly synthesised PG was labelled with the fluorescent D-amino acid HADA, which is specifically incorporated into PG17, in a strain expressing both FtsW-mCherry (which colocalises with PBP1, see below) and MurJ-sGFP. HADA incorporation appeared to colocalise with both proteins in cells in Phase 1 of the cell cycle and in most Phase 2 cells (Fig. 2a; see Fig. 1d for cell cycle phases). However, MurJ/HADA septal colocalisation was more frequent than FtsW/HADA colocalisation (88% vs. 70% of cells, N=200), as cells with septal FtsW but peripheral MurJ had peripheral HADA incorporation (see asterisks in Fig. 2a). This suggested that septal PG synthesis was dependent on the presence of MurJ. If this was the case, preventing MurJ recruitment to midcell should abolish septal PG synthesis. We therefore investigated the mechanism of MurJ localisation so that we could selectively prevent its septal recruitment, while maintaining correct FtsW/PBP1 septal localisation. For that purpose, we determined the timing of MurJ arrival to the septum, as localisation of divisome proteins is often dependent on the presence of earlier localising proteins18,19.

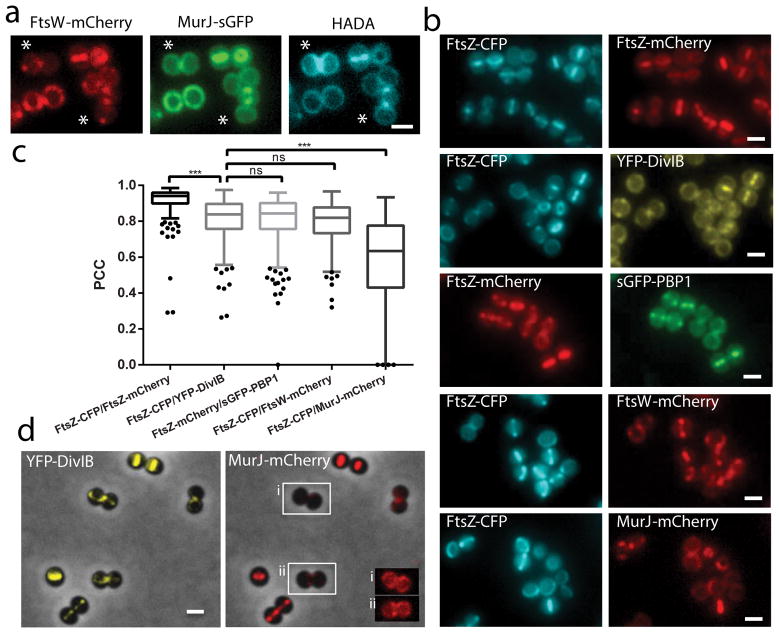

Figure 2. Hierarchy of arrival of key PG synthesis proteins to the divisome.

a, PG synthesis in strain ColWJ was labelled with HADA. Asterisks show cell with septal FtsW and peripheral MurJ and HADA labelling. b, Fluorescence microscopy images of strains (from top) ColZZ (positive control), ColZIB, ColP1Z, ColWZ and ColJZ. c, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) for pairs of fluorescent proteins expressed in the same strain. PCC=1 would indicate perfect colocalisation. Negative PCC values are represented as 0. From left to right, N=312, 391, 337, 330, 334 cells. Data are represented as box-and-whisker plots where boxes correspond to the first to third quartiles, lines inside the boxes indicate the median, ends of whiskers and outliers follow a Tukey representation. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test (***P<0.001 (1st vs 2nd sample P = 3.65E-45; 2nd vs 5th sample P = 1.13E-45) ; ns, not significant). d, Fluorescence microscopy images of strain ColJIB. Cells with septal YFP-DivIB localisation but MurJ-mCherry still not at the septum (peripheral) are highlighted in insets i and ii, where the brightness of fluorescence signal was increased to allow visualisation of MurJ localisation. Scale bars, 1 μm. Images in (a, b, d) are representative of three biological replicates.

In B. subtilis, divisome assembly is a two-step process, with proteins such as FtsA, ZapA and EzrA arriving very early, concomitantly with FtsZ, followed after a time delay by a second group of proteins including the DivIB/DivIC/FtsL sub-complex 20. We therefore compared S. aureus PBP1, FtsW and MurJ localisation with that of early divisome protein FtsZ and later divisome protein DivIB (Fig. 2b). Colocalisation between each protein and FtsZ was determined by measuring Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (PCC) for the fluorescence signals in the two channels, in cells showing FtsZ midcell localisation, as we reasoned that proteins arriving to the septum simultaneously with FtsZ should have a PCC close to 1 and this value should decrease for later divisome proteins. As a positive control we constructed a strain co-expressing FtsZ-CFP and FtsZ-mCherry. Colocalisation results indicated that DivIB arrives to the divisome later than FtsZ, as expected, and approximately at the same time as PBP1 and FtsW, while MurJ arrives later than DivIB/PBP1/FtsW (Fig. 2c), a result that is unlikely to be affected by nature of the fluorescent tags (Extended Data Fig. 1). In agreement, in 20% of the cells (N = 200) of a strain expressing both YFP-DivIB and MurJ-mCherry, YFP-DivIB was already localised at the septum, while MurJ-mCherry had not arrived yet (insets in Fig. 2d). This raised the possibility that MurJ septal recruitment could be dependent on the presence of the DivIB/FtsL/DivIC sub-complex. We therefore depleted expression of each of these three proteins using antisense RNA fragments21 (Supplementary Table 2), whose efficiency was assessed by western blot analysis and by the increase in cell volume resulting from divisome inhibition (Extended Data Fig. 2). Depletion of DivIB, FtsL or DivIC reduced septal colocalisation of FtsZ-CFP and MurJ-mCherry (Fig. 3a,b), but not of FtsZ and either FtsW or PBP1 (Extended Data Fig. 3), in agreement with their earlier recruitment to the divisome.

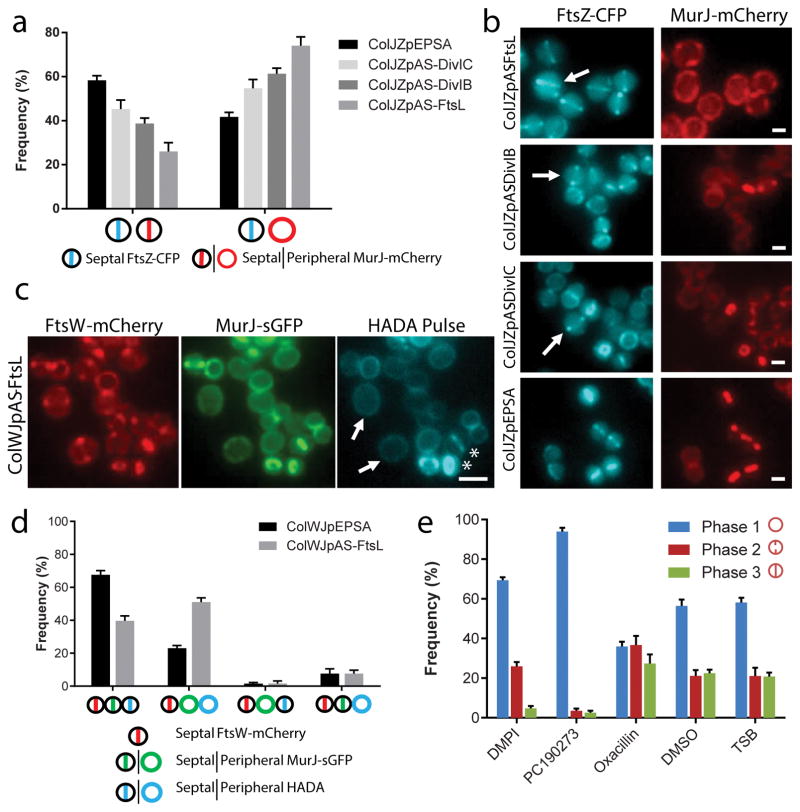

Figure 3. MurJ recruitment to the divisome is required for PG incorporation at the septum.

FtsZ-CFP/MurJ-mCherry colocalisation (a) and microscopy images (b) of cells expressing antisense RNA against ftsL, divIB or divIC, or carrying vector pEPSA (N=100 cells for each strain, in each of three biological replicates). Arrows show large cells with septal FtsZ-CFP but delocalised MurJ-mCherry. Scale bars, 1 μm. c, HADA septal incorporation in FtsL-depleted cells was only observed in cells with septal MurJ-sGFP (asterisks). Septal FtsW-mCherry was not sufficient to ensure HADA septal incorporation (arrows). Scale bar, 2 μm. d, Colocalisation between FtsW-mCherry, MurJ-sGFP and HADA labelling in FtsL-depleted (ColWJpAS-FtsL) or control (ColWJpEPSA) cells with septal FtsW-mCherry (N=100 cells for each strain, in each of three biological repeats). e, COL cells treated with DMPI (MurJ inhibitor), PC190723 (FtsZ inhibitor), oxacillin (Oxa, cell wall synthesis inhibitor), DMSO or TSB (mock-treated controls) for the duration of a cell cycle (see images in Extended Data Figure 5) were classified into each cell cycle phase (349<N<870 cells for each condition, in each of the three biological repeats). Data in (a, d, e) are column graphs where the height of the column represents the mean and the whiskers are the standard deviation. Images in (b, c) are representative of three biological replicates.

Having a tool to specifically delocalise MurJ, by depleting FtsL, while maintaining correct PBP1 and FtsW localization, allowed us to determine that new PG (labelled by a short pulse of HADA), was only incorporated at midcell if MurJ-sGFP was also present at the septum (Fig. 3c, asterisks and 3d). Finally, we showed that inhibiting MurJ activity using DMPI, a MurJ inhibitor12 that does not prevent its recruitment to the divisome (Extended Data Fig. 4a), drastically reduced HADA incorporation (i.e. PG synthesis) at the septum (Extended Data Fig. 4b–e).

Taken together, these data indicate that recruitment of MurJ to the divisome by the FtsL/DivIB/DivIC complex is likely the molecular cue directing PG synthesis specifically to the septum during division. Therefore, we would expect MurJ to be essential for the transition from Phase 1 to Phase 2 during the cell cycle, i.e., for initiation of septum synthesis. We treated COL wild type cells with DMPI for one cell cycle and characterised the distribution of cells in the three cell cycle phases. For comparison we tested other inhibitors, namely PC19072322, which targets FtsZ and oxacillin, which inhibits PG transpeptidation catalysed by PBPs (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5). Consistent with previous data9, in the absence of inhibitors approximately half of the cells were in Phase 1, with the other half split evenly between Phase 2 and Phase 3 (Fig. 3e). Inhibition of MurJ by DMPI resulted in accumulation of Phase 1 cells (70%, N > 300), indicating that MurJ is indeed crucial for entry in Phase 2. Phase 2 cells, which are synthesising the septum, were also halted, as flipping the PG precursor is essential for PG synthesis to occur.

The most surprising result was the almost complete absence of Phase 2 cells in the presence of PC190723, since this compound inhibits FtsZ treadmilling3, which was shown to control the rate of PG synthesis during septum formation in B. subtilis and therefore the rate of cell division3. One would therefore expect that addition of PC190723 would prevent Phase 2 cells, that were halfway through the process of septum synthesis, from completing this process. As this was not the case, we wondered if redirecting PG synthesis to the septum, driven by septal recruitment of MurJ, would provide the constrictive driving force for cytokinesis, as previously suggested for E. coli23,24, and result in septum closure independent of FtsZ treadmilling.

To visualise the process of septum closure and determine if FtsZ treadmilling occurs in S. aureus, we introduced an FtsZ sandwich fusion to sGFP (see methods) in the background of a strain expressing native FtsZ and followed the dynamics of Z-ring formation and constriction. We were able to observe FtsZ55-56sGFP movement, which was inhibited by PC190723 as expected (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Video 1). However, Z-ring constriction continued in many cells treated with PC190723, in accordance with the fact that PC190723-treated cells could complete Phase 2 of the cell cycle (Fig. 3e). Interestingly, when we followed Z-ring constriction in untreated cells, we observed biphasic cytokinesis, with a first step, immediately after Z-ring assembly, during which the divisome barely constricts, followed by a second step with a higher rate of Z-ring constriction (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 6a and Supplementary Video 2). Addition of PC190723 blocked constriction of large Z-rings, presumably in the first step of cytokinesis, but not of smaller Z-rings (Fig. 5a, b, Extended Data Fig. 6a and Supplementary Video 3). This indicates that only Z-rings in the first step of cytokinesis required treadmilling activity for constriction. To confirm these results, we used a functional fluorescent derivative of the divisome protein EzrA as a proxy for FtsZ localisation, given that EzrA interacts directly with FtsZ25,26. Similarly to what we observed for FtsZ, EzrA treadmilling was inhibited by PC190723 and EzrA rings underwent biphasic constriction where the second, faster, step was insensitive to PC190723 (Extended Data Fig. 7).

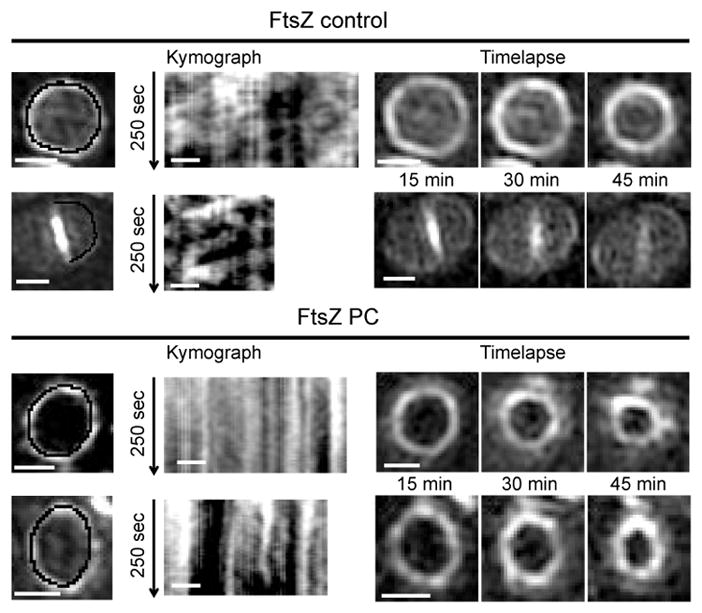

Figure 4. PC190723 impairs FtsZ55-56sGFP treadmilling in S. aureus.

ColFtsZ55-56sGFP cells were imaged by SIM every 5 sec for 250 sec, followed by three images taken 15 minutes apart, in the absence (FtsZ control) or presence (FtsZ PC) of PC190723. Kymographs were obtained by extracting fluorescence intensity values along the black line indicated in cells in the left panels, with each horizontal line of the kymograph corresponding to one time point. In the absence of PC190723 (upper panels) FtsZ movement is observed, leading to diagonal lines in the kymograph. Addition of PC190723 (lower panels) abolished FtsZ movement, resulting in vertical lines in the kymograph that correspond to maintenance of signal at fixed locations, but did not impair Z-ring constriction (timelapse on the right). Data are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 0.5 μm.

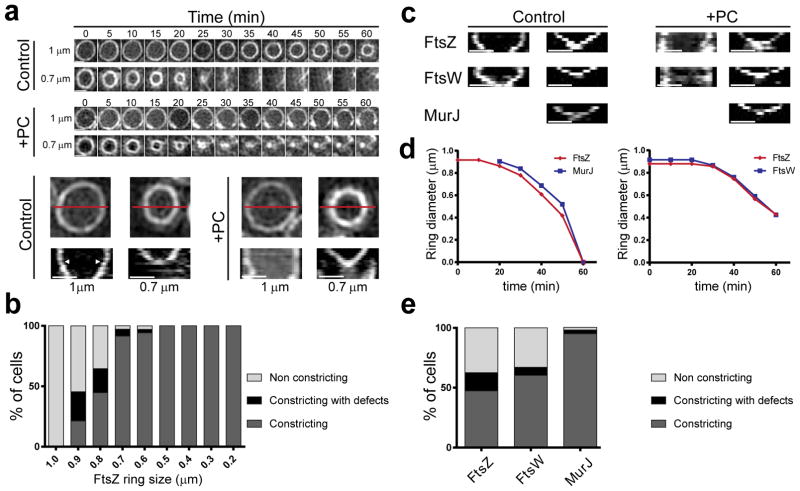

Figure 5. PG synthesis provides force for septum constriction.

a, Timelapse images and corresponding kymographs of FtsZ55-56sGFP rings in the absence (control) or presence (+PC) of FtsZ inhibitor PC190723. Kymographs were obtained by drawing a line (exemplified in red) across the cell for each time point. Arrowheads point to transition from first (no/slow constriction) to second (fast constriction) step of cytokinesis. b, Percentage of FtsZ55-56sGFP rings of different diameters that constricted in the presence of PC190723 (N=248). c, Kymographs of FtsZ55-56sGFP, FtsW-sGFP and MurJ-sGFP larger (left) and smaller (right) rings. PC190723 only abolished constriction of larger rings. d, Graphs showing diameter of FtsZ-mCherry and MurJ-sGFP rings (left) or FtsZ-mCherry and FtsW-sGFP rings (right) in single cells during cytokinesis. e, Percentage of FtsZ55-56sGFP, FtsW-sGFP and MurJ-sGFP rings that constricted in the presence of PC190723 (FtsZ N=254; FtsW N=176; MurJ=188). Data in (a, c) are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 0.5 μm.

It is possible that the transition between the first and the second step of Z-ring constriction corresponds to the start of substantial PG synthesis activity that results from MurJ recruitment. In agreement with this hypothesis, the divisome rings that contained MurJ did not display the first step of constriction and were insensitive to PC190723 (Fig. 5c, e and Extended Data Figs. 6b, 8). Furthermore, arrival of MurJ to the septum coincided with initiation of fast constriction (Fig. 5d and Extended Data Fig. 9a). In contrast, rings containing the earlier divisome protein FtsW paralleled the biphasic behaviour of the Z-ring (Fig. 5c, d, Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9b) and were susceptible to inhibition by PC190723, presumably during the initial stages of cytokinesis (Fig. 5e). Furthermore, while the FtsZ inhibitor PC190723 only blocked constriction of Z-rings at initial stages, addition of the MurJ inhibitor DMPI blocked ring constriction at all stages (Extended Data Fig. 6a).

We propose a model (Extended Data Fig. 10) where the S. aureus PG synthesis machinery continuously incorporates PG at the periphery of the cell during initial stages of the cell cycle. In preparation for division and following Z-ring assembly, the FtsL/DivIB/DivIC complex recruits MurJ to the divisome, which ensures that translocation of lipid II occurs exclusively at midcell. Substrate affinity27 then diverts the major PG synthase, PBP2, from the periphery to midcell where, together with other PG synthesis enzymes, it incorporates lipid II into the growing PG network. This mechanism forgoes the need for an additional dedicated multi-protein machinery and represents a new mode of controlling PG synthesis in two different locations, in the absence of an MreB-like cytoskeleton.

Importantly, after the initiation of massive PG synthesis activity at the leading edge of the constricting septum that follows MurJ recruitment, the FtsZ inhibitor PC190723, which inhibits FtsZ treadmilling, no longer prevents cytokinesis. Nevertheless, FtsZ treadmilling is likely to have a role in the organisation of septum synthesis, since ~15% of the Z-rings that were able to constrict in the presence of PC190723, did so defectively, similarly to E. coli FtsZ mutants impaired in GTPase activity 4.

Our data may reconcile two models proposed in the literature for the origin of the force required for cytokinesis to occur. In one model, this force has been proposed to be derived from FtsZ, either from the chemical energy of GTP hydrolysis which could promote bending of the FtsZ polymers or from the affinity of FtsZ filaments to bundle, which could result in condensation of the Z-ring 24,28. Alternatively, PG synthesis has been suggested to be the force for cytokinesis23,24. We propose that cytokinesis occurs in two steps: an initial, slow one, dependent on FtsZ treadmilling, for which FtsZ may be the driving force and that may be responsible for the initial invagination of the cell membrane, followed by a second, faster step, for which PG synthesis provides the driving force.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

METHODS

Bacterial growth conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. S. aureus strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB, Difco) at 200 r.p.m with aeration at 37 °C or on tryptic soy agar (TSA, Difco) at 30 or 37°C. E. coli strains were grown in Luria–Bertani broth (Difco) with aeration, or Luria–Bertani agar (Difco) at 37 or 30°C. When necessary, antibiotics ampicillin (100 μg ml−1), erythromycin (10 μg ml−1), kanamycin (50 μg ml−1), neomycin (50 μg ml−1) or chloramphenicol (30 μg ml−1) were added to the media. 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside (X-gal, Apollo Scientific) was used at 100 μg ml−1. Unless stated otherwise, isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Apollo Scientific) was used at 0.1 mM to induce expression of constructs under the control of the Pspac promoter. Cadmium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at 0.1 μM when required to induce expression of constructs under the control of the Pcad promoter.

Construction of S. aureus fluorescent strains

Cloning of fluorescent fusions in S. aureus was done using the following general strategy: plasmids were propagated in E.coli strains DC10B or DH5α and purified from overnight cultures supplemented with the relevant antibiotics. Plasmids were then introduced into electrocompetent S. aureus RN4220 cells as described before29 and transduced to COL using phage 80α30. Constructs were confirmed by PCR and sequencing of the amplified fragment.

The ColMurB-GFP, ColMurD-GFP, ColMurF-GFP, ColFemB-GFP and ColpSGEzrA-GFP strains were constructed using the pSG5082 vector31. Briefly, DNA fragments with approximately 500 bp spanning the 3′ ends (minus stop codons) of the murB, murD, murF, femB and ezrA genes from COL were amplified using primer pairs murBg_P1/murBg_P2; murDg_P1/murDg_P2; murFg_P1/murFg_P2; femBg_P1/femBg_P2 and ezrAP8Kpn/ezrAP9Xho, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). Fragments were digested with KpnI and XhoI restriction enzymes and cloned into pSG5082 upstream and in frame with gfpmutP2, originating plasmids pSG-murB, pSG-murD, pSG-murF, pSG-femB and pSG-ezrA. These plasmids were then electroporated to RN4220, where they integrated in the genome by a single homologous recombination event and subsequently transduced to COL. Resulting strains contain the corresponding fluorescent fusions in each gene’s native locus under the control of its native promoter, followed by the pSG5082 backbone and a truncated copy of the gene. The strategy to construct ColFemX-sGFP was essentially the same, except that the pFAST332 vector was used instead of pSG5082. A femX fragment was amplified from COL DNA with primers femXg_P1 and femXg_P2, digested with KpnI/XhoI and cloned into pFAST3 upstream and in frame with sgfp, giving pFAST-femX, which was electroporated into RN4220 and transduced into COL. Strain ColMurG-GFP was obtained by transducing the murG-gfp construct from BCBMS00133 into COL.

Strains ColFemA-mCherry, ColFtsW-mCherry, ColMurJ-mCherry, ColRodA-sGFP, ColsGFP-PBP1 and ColsGFP-PBP3 were constructed by allelic replacement strategies using the pMAD vector. In each case three DNA fragments (F1, F2 and F3 – see Supplementary Table 5) containing overhangs complementary with adjacent fragments were amplified from COL DNA and joined by overlap PCR, giving F1-F2-F3 fusion constructs. The full constructs were then amplified by PCR using up- and downstream primers (P1 and P6 in each case), digested with the corresponding restriction enzymes and cloned into pMAD. Integration and excision of the pMAD derivatives in COL by a double recombination event, leading to allelic exchange, was performed as described before34. The relevant information for the cloning steps for each strain is described in Supplementary Table 5.

In order to obtain strains ColFtsW-sGFP and ColMurJ-sGFP, plasmids pMAD-ftsWsgfp and pMAD-murJsgfp were first constructed. For pMAD-ftsWsgfp, three fragments (F1, F2 and F3), each flanked by restriction sites, were introduced into pMAD. F1, containing the 3′ end of ftsW minus the stop codon, was amplified from NCTC8325-4 DNA with primers ftsWg_P1/ftsWg_P2 and digested with SmaI/SalI; F2, containing sgfp, was amplified from pTRC99a-P7 with primers ftsWg_P3/ftsWg_P4 and digested with SalI; F3, containing the downstream region of ftsW, was amplified from NCTC8325-4 DNA and digested with SalI/BamHI. Fragments were then sequentially cloned into pMAD (F1, followed by F3 and finally by F2) using the adjacent restriction sites, giving pMAD-ftsWsgfp. For pMAD-murJsgfp the same strategy was used. F1, containing the 3′ end of murJ minus the stop codon, was amplified from COL DNA using primers murJg_P1/murJg_P2 and digested with SmaI/SalI; F2, containing sgfp, was amplified from pTRC99a-P7 using primers murJg_P3/murJg_P4 and digested with SalI; F3, containing the last 26bp of murJ and its downstream region, was amplified from COL DNA using primers murJg_P5/murJg_P6 and digested with SalI/BamHI. Fragments were cloned into pMAD resulting in plasmid pMAD-murJsgfp. Plasmids pMAD-ftsWsgfp and pMAD-murJsgfp were then electroporated to RN4220, transduced to COL and following allelic replacement strains ColFtsW-sGFP and ColMurJ-sGFP were obtained.

Strain ColFtsZ-mCherryi was constructed using the pBCB13 plasmid35, a derivative of pMAD that allows allelic exchanges in the spa locus. Briefly, a DNA fragment containing the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS), the ftsZ gene without its stop codon and a 5 amino acid linker was amplified by PCR from COL with primers iftsZm_P1/iftsZm_P2. A second fragment containing mCherry was amplified from pBCB4che using primers iftsZm_P3/iFtsZm_P4. The two fragments were joined by overlap PCR using primers iftsZm_P1/iftsZm_P4 and the resulting construct was digested with SmaI/XhoI and cloned into pBCB13, downstream of the Pspac promoter, giving pBCB13-ftsZmch. Similarly, to construct strain ColDltC-sGFPi a DNA fragment containing an RBS, the dltC gene without stop codon and a two amino acid linker was amplified by PCR from COL with primers idltCg_P1 and idltCg_P2. A second fragment containing sgfp was amplified from pTRC99a-P7 using primers idltCg_P3/idltCg_P4. The two fragments were joined by overlap PCR using primers idltCg_P1/idltCg_P4 and the resulting construct was digested with SmaI/XhoI and cloned into pBCB13 downstream of the Pspac promoter, giving pBCB13-dltCsgfp. Following transduction to COL, plasmids integration/excision at the spa locus was performed as described before34.

Strain ColFtsZ55-56sGFP was constructed using the pCNX replicative plasmid9 to express an FtsZ-sGFP sandwich fusion. In brief, three DNA fragments (F1, F2 and F3) with overhangs were amplified in order to construct a sgfp fusion inserted within the ftsZ coding sequence between codons 55 and 5636, flanked by 10 amino acid linkers (GGGGSx2). F1, containing an RBS and the first 165 bp of ftsZ was amplified from COL DNA using primers ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P1 and ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P2; F2, containing sgfp flanked by linker sequences was amplified from pTRC99a-P7 using primers ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P3 and ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P4; F3, containing the remaining 1008 bp of ftsZ (from nucleotide 166 onwards) was amplified from COL DNA using primers ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P5 and ftsZswgfp_pCNX_P6. The three fragments were joined by overlap PCR, digested with BamHI/EcoRI and cloned into pCNX giving pCN-ftsZ55-56sGFP, which was then transduced into COL and the resulting strain was named ColFtsZ55-56sGFP.

Strain ColMraY-sGFP was constructed using the pCN51 replicative plasmid to express an MraY-sGFP sandwich fusion. Briefly, three DNA fragments (F1, F2 and F3) with overhangs were amplified in order to construct a fusion with sgfp inserted within the mraY coding sequence, between codons 220 and 221. F1, containing an RBS and the first 660 bp of mraY, was amplified from COL DNA using primers mraYg_P1/mraYg_P2; F2, containing sgfp minus the stop codon, was amplified from pTRC99a-P7 with primers mraYg_P3/mraYg_P4; F3, containing the last 306 bp of mraY, was amplified from COL using primers mraYg_P5 and mraYg_P6. The three fragments were joined by overlap PCR and digested with SmaI and cloned into pCN51, resulting in pCN-mraYsgfp.

Strains ColWZ and ColJZ were constructed by transducing plasmids pMAD-ftsWmch and pMAD-murJmch, respectively, into BCBAJ020. ColP1Z was constructed by transducing pMAD-sgfpPbp1 into ColFtsZ-mCherryi. Strains ColWgZm and ColJgZm were constructed by transducing plasmids pMAD-ftsWsgfp and pMAD-murJsgfp, respectively, into ColFtsZ-mCherryi. Strain ColWJ was obtained by transducing pMAD-murJsgfp to ColFtsW-mCherry. In each case, allelic replacement was performed as described above.

In order to construct ColZZ, an ftsZ-mCherry fusion was amplified from genomic DNA of ColFtsZ-mCherryi with primers ftsZm_pCNX_P1 and ftsZm_pCNX_P2, digested with BamHI/EcoRI and cloned in pCNX downstream of the Pcad promoter, giving plasmid pCN-ftsZmch. This plasmid was then electroporated into RN4220 and transduced to BCBAJ020, giving strain ColZZ.

To study colocalisation between DivIB with FtsZ or MurJ, an yfp-divIB fusion was constructed and cloned into pCNX. Briefly, a fragment containing yfp minus the stop codon and a 3′ terminal overhang was amplified from pMUTINYFPKan37 with primers ydivIB_pCNX_P1/ydivIB_pCNX_P2. A second fragment containing the full divIB gene with a 5′ overhang was amplified from COL DNA with primers ydivIB_pCNX_P3/ydivIB_pCNX_P4. The two fragments were then joined by overlap PCR, digested with SmaI/KpnI and cloned into pCNX downstream of Pcad, giving plasmid pCN-yfpDivIB. This plasmid was transduced to BCBAJ020 and ColMurJ-mCherry, giving strains ColZIB and ColJIB, respectively.

Construction of S. aureus strains containing antisense RNA vectors

To construct strains carrying antisense RNA vectors, 250 bp fragments of divIB or divIC genes were amplified from COL DNA with primer pairs ASdivIB_P1/ASdivIB_P2 and ASdivIC_P1/AS_DivIC_P2, respectively, digested with EcoRI/BamHI and cloned in antisense direction into pEPSA5, relative to the xylose inducible T5X promoter, giving pAS-DivIB and pAS-DivIC. These plasmids were then transduced into ColJZ, giving ColJZpAS-DivIB and ColJZpAS-DivIC respectively. Additionally, phage lysates were obtained from AS-022 and AS-185 strains21 carrying antisense RNA pEPSA vectors pAS-022 and pAS-185 targeting ftsA and ftsL, respectively. pAS-022 was transduced to ColWZ and ColP1Z, giving strains ColWZpAS-FtsA and ColP1ZpAS-FtsA. pAS-185 was transduced to ColJZ, ColWZ, ColP1Z and ColWJ, giving strains ColJZpAS-FtsL, ColWZpAS-FtsL, ColP1ZpAS-FtsL and ColWJpAS-FtsL, respectively. Control strains for these experiments were obtained by transducing the empty vector pEPSA5 into ColJZ, ColWZ, ColP1Z and ColWJ, giving strains ColJZpEPSA, ColWZpEPSA, ColP1ZpEPSA and ColWJpEPSA, respectively.

Growth curves of S. aureus strains

Overnight cultures of COL strains encoding fluorescent derivatives of PG synthesis enzymes were back-diluted to OD600nm 0.02 in TSB and grown at 37°C for 11 hours with OD600nm measurements taken every hour. Doubling times were calculated for each strain during exponential growth phase.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assays

MICs of relevant antimicrobial compounds were determined by broth microdilution in sterile 96-well plates. The medium used was TSB, containing a series of two-fold dilutions of each compound. Cultures of S. aureus strains and mutants were added at a final density of 5×105 CFU ml−1 to each well. Wells were reserved in each plate for sterility control (no cells added) and cell viability (no compound added). Plates were aerobically incubated at 37°C. Endpoints were assessed visually after 24 and 48 h. All assays were done in triplicate.

Western Blotting

S. aureus strains ColJZpEPSA, ColJZpAS-DivIB and ColJZpAS-DivIC were grown overnight, back-diluted 1:200 in fresh TSB and incubated at 37°C until an OD600nm of approximately 0.2. At this point, xylose was added to the medium at 4% to allow the expression of the antisense RNA fragments. After 1 hour of antisense expression, cells were harvested and broken with glass beads in a FastPrep FP120 cell disrupter (Thermo Electro Corporation). Samples were centrifuged to remove unbroken cells and debris and total protein content of the clarified lysates was determined using the Bradford method and bovine serum albumin as a standard (BCA Protein Assay Kit, Pierce). Equal amounts of total protein from each sample were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE at 80V and then transferred to Hybond-P PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare) using a Semi-dry transfer cell (Biorad), according to standard western blotting techniques. Membranes were cut to separate PBP2A region from DivIB or DivIC region. DivIB and DivIC proteins were detected using specific polyclonal antibodies at 1:5000 and 1:10000 dilutions, respectively. PBP2A was detected using the antibody from a Slidex MRSA detection kit (Biomerieux) at 1:500 dilution. Protein bands were visualised using the ECL Prime Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare), following manufacturer’s instructions.

S. aureus imaging by fluorescence microscopy

Super-resolution Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM) imaging was performed using an Elyra PS.1 microscope (Zeiss) with a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 oil DIC M27 objective. SIM images were acquired using five grid rotations, unless stated otherwise, with 34 μm grating period for the 561 nm laser (100 mW), 28 μm period for 488 nm laser (100 mW) and 23 μm period for 405 nm laser (50 mW). Images were captured using a Pco.edge 5.5 camera and reconstructed using ZEN software (black edition, 2012, version 8.1.0.484) based on a structured illumination algorithm, using synthetic, channel specific optical transfer functions and noise filter settings ranging from −6 to −8.

Wide-field fluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope with a Plan-Apochromat 100x/1.4 oil Ph3 objective. Images were acquired with a Retiga R1 CCD camera (QImaging) using Metamorph 7.5 software (Molecular Devices).

For fluorescence microscopy experiments, unless stated otherwise, overnight cultures of S. aureus strains were back-diluted 1:200 in fresh media with appropriate inducers and allowed to grow until OD600nm ~ 0.6 before being harvested and washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Cells were then placed on microscope slides covered with a thin layer of agarose (1% in PBS) and imaged by SIM or wide-field microscopy.

To assess if MurJ localisation was dependent on interaction with its substrate, strain ColMurJ-mCherry was grown until OD600nm of 0.4 and incubated with 3-{1-[(2,3-Dimethylphenyl)methyl]piperidin-4-yl}-1-methyl-2-pyridin-4-yl-1H-indole (DMPI, gift from Merck) at 3 μg ml−1 for 30 minutes and then imaged by wide-field fluorescence microscopy as described above.

For antisense RNA experiments, strains were grown until OD600nm of 0.1–0.2 at which point expression of the antisense RNA fragments was induced with xylose (Apollo Scientific) at a final concentration of 4% for 1 hour. Cells were then harvested and washed with PBS to remove xylose, mounted on microscope slides as described above and imaged by wide-field fluorescence microscopy. Assays were done in triplicate.

To evaluate localisation of peptidoglycan synthesis activity, S. aureus cells were given a pulse of fluorescent D-amino-acid HADA17 (250 μM) for 1 min and then washed two times with PBS. Cells were then placed on an agarose pad and visualised by wide-field microscopy. Assays were done in triplicate.

To label S. aureus membranes, cells were incubated with Nile Red (Invitrogen) at a final concentration of 10 μg ml−1 for 5 minutes at room temperature, washed with PBS and then mounted on microscope slides.

For timelapse experiments, all cultures were grown overnight in TSB. For ColFtsZ55-56sGFP and ColpSGEzrA-GFP the media was supplemented with kanamycin 150 μg ml−1 and erythromycin 10 μg ml−1 respectively. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:200 in fresh TSB media without antibiotic but supplemented with appropriate inducers (CdCl2 0.1 μM for ColFtsZ55-56sGFP; IPTG 0.5mM for ColWgZm and ColJgZm). After being harvested, cells were re-suspended in M9 microscopy media (KH2PO4 3.4 g l−1, VWR; K2HPO4 2.9 g l−1, VWR; di-ammonium citrate 0.7 g l−1, Sigma-Aldrich; sodium acetate 0.26 g l−1, Merck; Glucose 1 %, Merck; MgSO4 0.7 mg l−1, Sigma-Aldrich; CaCl2 7 mg l−1, Sigma-Aldrich; casaminoacids 1 %, Difco; MEM aminoacids 1x,Thermo Scientific; MEM vitamins 1x, Thermo Scientific). The media was supplemented when required with IPTG 0.5 mM, CdCl2 0.1 μM, DMPI 8 μg ml−1 or PC190723 5 μg ml−1. Cultures were then spotted on a pad of 1.5 % agarose in the same supplemented media and mounted in a geneframe on a microscope slide. The time it took between the cells contacting the pad and the start of acquisition was 5 min in all conditions.

HADA incorporation microscopy assay

To assess if MurJ activity was required for HADA incorporation, strains COL and ColDltC-sGFPi (which expresses a cytoplasmic DltC-sGFP fusion and therefore can be easily distinguished from COL under the microscope) were grown to an OD600nm of 0.4 at which point each culture was separated into two flasks and either DMPI (3 μg ml−1 in DMSO) or DMSO (0.2 % final concentration) were added to the cultures. Following 25 minutes of incubation, HADA (500 μM) was added to each culture for 5 minutes. Cells were then harvested, washed twice with PBS (supplemented with DMPI when applicable) and DMSO-treated COL cells were mixed with DMPI-treated ColDltC-sGFPi cells. To exclude the possibility that the expression of DltC-sGFP affected the results, a reverse experiment was performed where cells of DMSO-treated ColDltC-sGFPi were mixed with DMPI-treated COL. These mixtures of two strains were then imaged by fluorescence microscopy as described above.

Functionality test for EzrA-GFP construct

Strains COL and COLΔEzrA were grown overnight in TSB and strain ColpSGEzrA-GFP was grown in TSB plus erythromycin 10 μg ml−1 at 37°C with aeration. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:200 in fresh TSB and incubated at 37°C with aeration. Once the OD600nm reached ~0.6, cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS and spotted on a thin layer of 1.2% agarose in PBS. Cultures were imaged by phase-contrast, single cells were identified and cell area measured using eHooke (see below), as lack of EzrA results in the appearance of larger cells38.

Imaging of FtsZ55-56sGFP treadmilling by SIM

To visualise FtsZ55-56sGFP movement in strain ColFtsZ55-56sGFP, and EzrA-GFP movement in strain ColpSGEzrA-GFP, 50 frames of SIM images were acquired with 5 second intervals (total time of acquisition of 250 seconds) using the 488 nm laser at 50% and a 50 msec exposure time. Following this acquisition, for FtsZ, a short timelapse of 3 images taken 15 minutes apart was performed to check if the corresponding rings were constricting. These experiments were performed with and without PC190723 at 5 μg ml−1. To analyse FtsZ/EzrA movement, the 50 frames were aligned and 1 pixel lines were drawn over the rings and then plotted in a kymograph.

Visualisation of divisome ring constriction by SIM

In order to follow FtsZ55-56sGFP or EzrA-GFP ring constriction over time, ColFtsZ55-56sGFP or ColpSGEzrA-GFP dividing cells were imaged by SIM every 5 minutes for 1 hour using the 488 nm laser at 50% power and a 50 msec exposure time. These experiments were performed with and without PC190723 (5 μg ml−1; laser power 50%) and with DMPI for FtsZ only (8 μg ml−1; laser power 100%). Following SIM image reconstruction, cropped stacks containing individual cells were used to plot Z-ring constriction kymographs over the 1 hour period by drawing a 3 pixel line across the diameter of the cell, crossing the fluorescent signal, using Fiji software39. The percentage of cells for which the FtsZ ring did not constrict, constricted with defects or constricted in relation to their initial ring size, in the presence of PC190723, was plotted using GraphPad Prism 6.

In order to follow constriction of FtsW-sGFP and MurJ-sGFP rings in strains ColFtsW-sGFP and ColMurJ-sGFP respectively, cultures were spotted on an M9 pad, with and without PC190723, and imaged by SIM. The 488 nm laser was used at 100% intensity, with an exposure time of 50 msec. To decrease photodamage due to high laser power, images were acquired every 10 min (instead of 5 min) during 1 hour. These settings were also applied for ColFtsZ55-56sGFP for comparison. For MurJ-sGFP timelapses were also performed with a 5 min interval to confirm the absence of biphasic behaviour of the constricting ring. Only cells with MurJ-sGFP signal absent in the first frame but present in the second frame were analysed to ensure that the entire constriction process was observed. Following SIM image reconstruction, cropped stacks containing individual cells were used to plot constriction kymographs as described above.

Timelapse stacks of ColFtsZ55-56sGFP, ColFtsW-sGFP and ColMurJ-sGFP in the presence of PC190723 were used to count the number of cells that had the fusion at midcell in the first frame and determine the percentage of those cells that constricted, constricted with defects or did not constrict in the presence of PC190723 for 60 min. Data was plotted using GraphPad Prism 6.

To observe constriction of FtsW-sGFP and MurJ-sGFP rings in cells expressing FtsZ-mCherry, strains ColWgZm and ColJgZm were imaged by SIM in M9 media supplemented with IPTG, every 10 min for 1 h, using the 488 nm laser and the 561 nm laser (100% laser power, 50 msec and 50% laser power, 50 msec respectively). Cells of ColWgZm where FtsZ-mCherry showed biphasic constriction behaviour, and cells of ColJgZm where MurJ-sGFP signal appeared on the third frame, were used to measure the ring diameter for each protein in all frames.

Inhibition of the cell cycle assays

An overnight culture of strain COL was back-diluted 1:200 and grown until OD600nm ~ 0.4 at which point either DMPI12 (3 μg ml−1), PC190723 (2.5 μg ml−1), oxacillin (1000 μg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich) or DMSO (0.2 %) were added to the medium. Cells were then grown for 30 minutes with each inhibitor, harvested and labelled with Nile Red, as described above, before being imaged by SIM. Cells were sorted into each phase of the cell cycle (Phase1, Phase2 or Phase3), as previously described 9. Assays were done in triplicate.

Automatic cell imaging analysis

Analysis of phase-contrast and fluorescence images was performed using eHooke, an in-house developed software. For cell segmentation, eHooke uses phase-contrast images and applies the isodata algorithm40 for automatic thresholding to find a pixel intensity value that separates the pixels corresponding to the background from those corresponding to cells. Using this threshold, the software then creates a binary mask which is used to compute the Euclidean Distances41 of each pixel in order to find the centres of individual regions inside the mask. The software then expands those centres to define individual cell regions using the watershed algorithm42.

In order to measure cell areas and volumes, eHooke first defines each individual cell region, computes the area by counting the number of pixels inside the region and the volume by measuring the long and short axes of the cell. Cell volume is then derived assuming a prolate spheroid shape as described before9.

To calculate fluorescent ratios (FR) between septal and membrane signal, eHooke was used to define the different regions of the cell, namely membrane, cytoplasm and septum in images obtained by wide-field fluorescence microscopy. The membrane is defined by dilating the outline of the cell towards its inside. To separate the septum from the cytoplasm the software uses the isodata algorithm40 to find the brightest region inside the cell. This region is then defined as the septum. To measure the median fluorescence, only the 25% brightest pixels of the septum were considered, in order to remove possible misidentified pixels from the measurement. Only cells with a closed septum were selected for measurements. FR values were then calculated according to the equation FR =[Median(Septum)-Background]/[Median(Membrane)-Background].

In order to measure the Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (PCC) between two fluorescent proteins in a strain, images of each fluorescence channel were aligned and loaded side-by-side in eHooke. Following automatic cell segmentation, cells showing an FtsZ signal at the septum were selected for PCC measurements. The pixels corresponding to each cell were isolated and PCC values between channels were then calculated using the following equation, adapted from 43: , where Xi and Yi correspond to each pixel intensity for two fluorescence channels and X̄ and Ȳ correspond to the mean intensities of those channels.

Code availability

Code is available in https://github.com/BacterialCellBiologyLab/Bruno-Saraiva-2017

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). Unpaired student’s t-tests were used to evaluate the differences of cellular volumes as well as to compare fluorescence ratios between peripheral and septal wall signal intensity. Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare differences between PCC non-normal distributions obtained in colocalisation experiments. P values ≤0.05 were considered as significant for all analysis performed and were indicated with asterisks: *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01 and ***P≤0.001.

Data availability

Source data for figures 1–3 and 5 and Extended Data figures 1–4, 7 and 9 are provided with the paper.

Extended Data

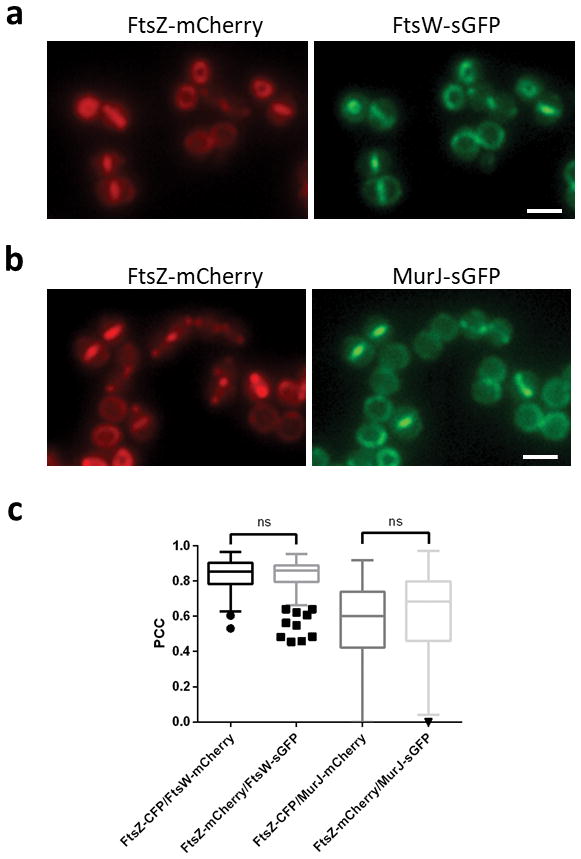

Extended Data Figure 1. Switching fluorescent tags has no effect on protein colocalisation data.

COL strains expressing FtsZ-mCherry/FtsW-sGFP (a) or FtsZ-mCherry/MurJ-sGFP (b) were compared to strains expressing FtsZ-CFP/FtsW-mCherry or FtsZ-CFP/MurJ-mCherry, respectively (described in Fig. 2b and c). Scale bars, 2 μm. c, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) values between fluorescence channels for each protein fusion pair were calculated for cells showing septal FtsZ localisation. From left to right, N=138, 136, 133, 139 cells. Negative PCC values are represented as 0. Data are represented as box-and-whisker plots where boxes correspond to the first to third quartiles, lines inside the boxes indicate the median and ends of whiskers and outliers follow a Tukey representation. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test (ns, not significant). Images in (a,b) are representative of three biological replicates.

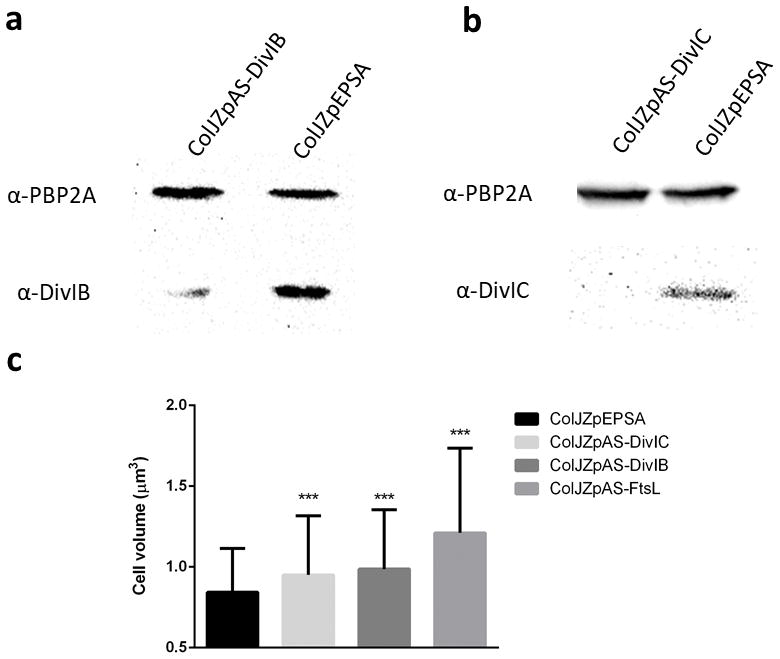

Extended Data Figure 2. Antisense RNA fragments targeting the DivIB/DivIC/FtsL complex increased cell volume and decreased protein expression.

a, Western blot showing total protein extracts of ColJZpAS-DivIB following 1 hour of antisense induction and control ColJZpEPSA probed with antibodies against either PBP2A (loading control - upper bands) or DivIB (lower bands). b, Western blot showing total protein extracts of ColJZpAS-DivIC following 1 hour of antisense induction and control ColJZpEPSA probed with antibodies against either PBP2A (loading control – upper bands) or DivIC (lower bands). Images in (a,b) are representative of three biological replicates. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. c, Cell volume of cells expressing antisense RNA against ftsL, divIB or divIC, or carrying vector pEPSA (Left to right, N=421, 379, 279, 361 cells). Data represented in column graphs where the height of the column represents the mean and the whiskers are the standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-sided unpaired t-test (***P<0.001, 1st vs 2nd column, P = 3.50E-06; 1st vs 3rd column, P = 3.80E-08; 1st vs 4th column, P = 1.27E-29).

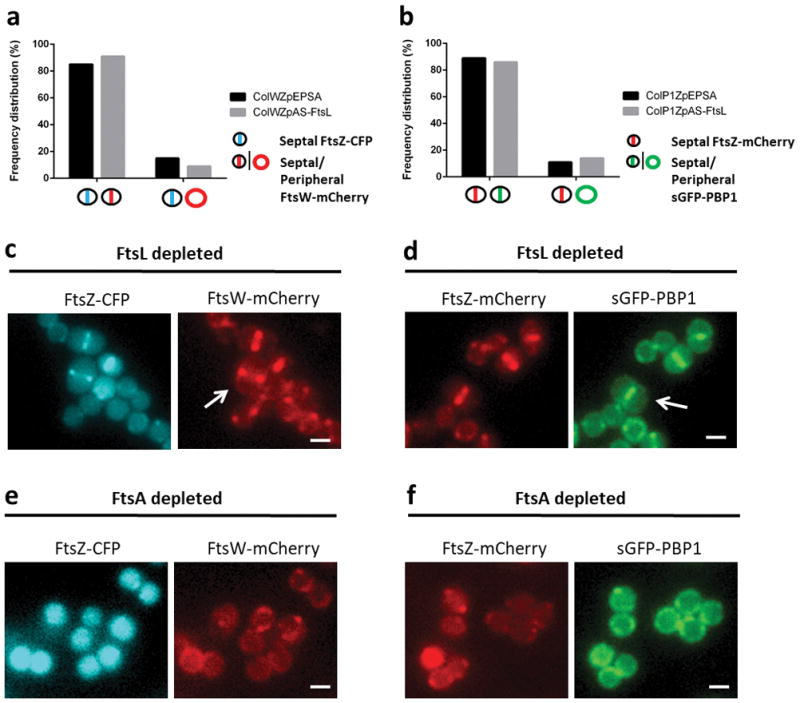

Extended Data Figure 3. FtsW and PBP1 recruitment to the divisome is independent of FtsL/DivIB/DivIC complexes.

Strains ColWZpAS-FtsL and ColP1ZpAS-FtsL, harbouring FtsZ-CFP/FtsW-mCherry and FtsZ-mCherry/sGFP-PBP1 fluorescent fusion pairs, respectively, were depleted of FtsL expression using antisense RNA and imaged by wide field fluorescence microscopy. a, Frequency of FtsZ-CFP and FtsW-mCherry co-occurrence in ColWZpAS-FtsL when compared to control ColWZpEPSA (N=200 for each). b, Frequency of FtsZ-mCherry and sGFP-PBP1 co-occurrence in ColP1ZpAS-FtsL and in control ColP1ZpEPSA (N=200 for each). Very large FtsL-depleted cells were observed where either FtsW-mCherry (c) or sGFP-PBP1 (d) co-localised with the FtsZ fusion at the septum (arrows). e,f, Inhibition of divisome assembly at an early stage by depletion of FtsA expression in either ColWZpAS-FtsA or ColP1ZpAS-FtsA prevented the recruitment of FtsW-mCherry (e) or sGFP-PBP1 (f) to the septum, concomitant with FtsZ destabilisation. Images in (c–f) are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 1 μm.

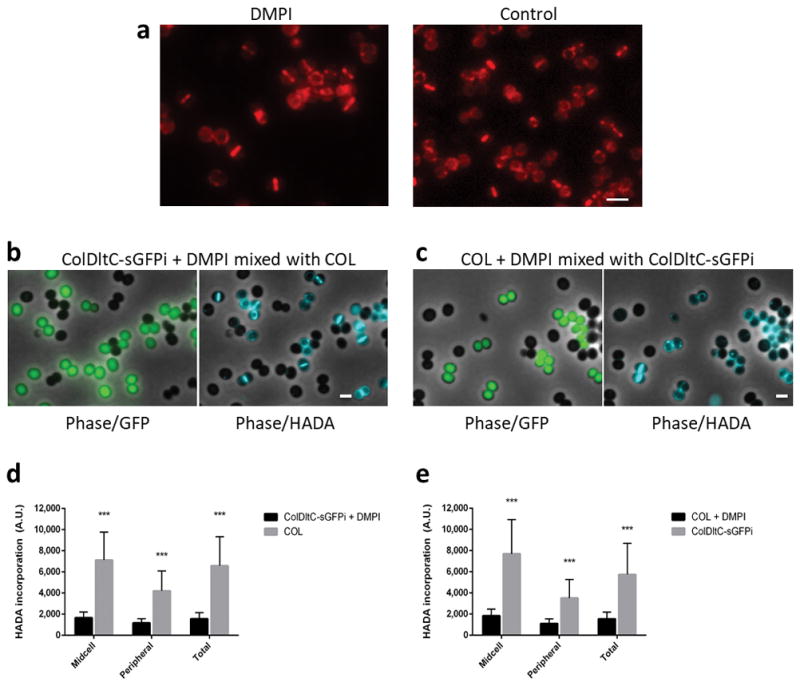

Extended Data Figure 4. Inhibition of MurJ activity does not prevent its recruitment to midcell but impairs PG synthesis.

a, Fluorescence microscopy images of ColMurJ-mCherry cells grown in the presence (left) or absence (right) of MurJ inhibitor DMPI for 30 minutes at 2X MIC. Scale bar, 2 μm. b,c Fluorescence microscopy images showing mixed cultures of either (b) DMPI-treated ColDltC-sGFPi cells mixed with COL cells or (c) DMPI-treated COL cells mixed with ColDltC-sGFPi cells, following incubation with HADA. The two cultures, which can be easily distinguished due to GFP expression in ColDltC-sGFPi, were mixed on the same slide to decrease fluorescence variation of HADA signal due to imaging conditions. Data shows that HADA incorporation (i.e. PG synthesis) is greatly reduced in the presence of DMPI. Phase contrast/GFP channel overlays are shown on the left and phase contrast/HADA channel overlays are shown on the right. Scale bars, 1 μm. d, e HADA fluorescence signal measured at the midcell (Midcell), the periphery (Peripheral) or over the entire cell (Total) of DMPI-treated ColDltC-sGFPi cells mixed with COL cells (d) or DMPI-treated COL cells mixed with ColDltC-sGFPi cells (e). Images in (a–c) are representative of three biological replicates. Data in (d,e) are represented as column plots (N=100 cells for each column) where the height of the column is the mean and the whiskers indicate standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using two-sided unpaired t-tests (***, P<0.001; panel d: P = 2.34E-38 for midcell; P = 1.81E-29 for peripheral; P = 9.22E-34 for total; panel e: P = 1.74E-33 for midcell; P = 8.77E-25 for peripheral; P = 7.60E-26 for total).

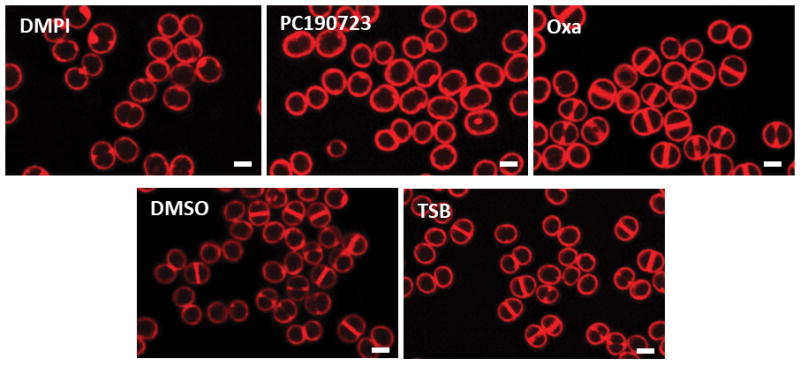

Extended Data Figure 5. Effect of antibiotics on cell cycle progression of S. aureus.

SIM images of Nile Red stained COL cells treated with DMPI (MurJ inhibitor), PC190723 (FtsZ inhibitor), oxacillin (Oxa, cell wall synthesis inhibitor), DMSO or TSB (mock-treated controls) for the duration of one cell cycle (30 min). Images are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 1 μm.

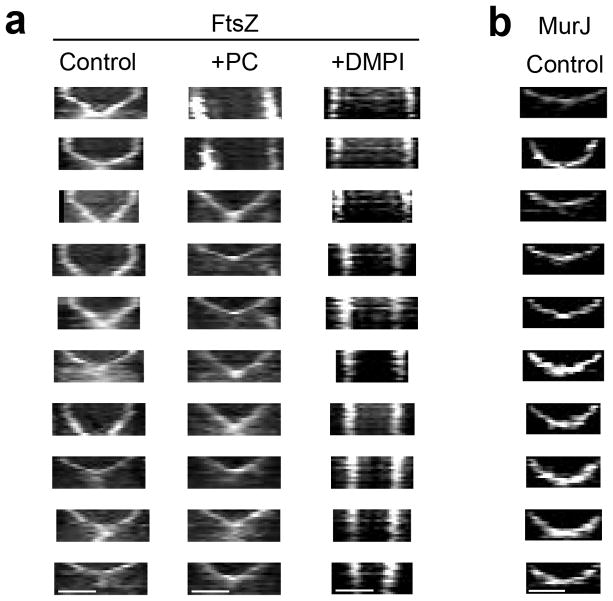

Extended Data Figure 6. Additional kymographs showing constriction of FtsZ55-56sGFP and MurJ-sGFP rings.

a, Kymographs of 10 cells per column showing constriction of FtsZ55-56sGFP rings obtained by imaging ColFtsZ55-56sGFP cells every 5 min for a total of 60 min (laser power 50%), in the absence (Control) or presence of either PC190723 (+PC) or DMPI (+DMPI). Since S. aureus cells are not synchronised, cells at all stages of cytokinesis can be observed. Larger FtsZ55-56sGFP rings had a biphasic behaviour (no/slow constriction followed by fast constriction) while smaller rings, further ahead in the cell cycle, were only observed undergoing the fast constriction step. Addition of PC190723 inhibited constriction of larger rings (see top two kymographs), but not of smaller rings, which were able to complete cytokinesis. Addition of DMPI completely blocked constriction of FtsZ55-56sGFP rings of all sizes. b, Kymographs showing constriction of MurJ-sGFP rings in ColMurJ-sGFP cells imaged every 5 min for a total of 60 min (laser power 100%). Cells where MurJ-sGFP signal appears on the second frame were chosen for analysis to ensure that the entire constriction process was imaged. Fast constriction started immediately upon MurJ-sGFP arrival to the division septum and therefore rings did not show biphasic behaviour. Data are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 0.5 μm.

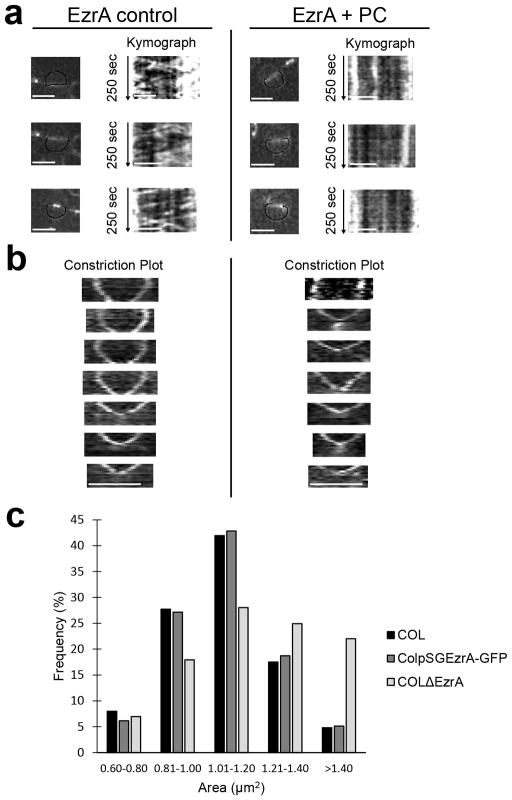

Extended Data Figure 7. Z-ring protein EzrA shows impaired treadmilling in the presence of PC190723 and biphasic ring constriction.

a, ColpSGEzrA-GFP cells, expressing a functional EzrA fusion to GFP, were imaged by SIM every 5 sec in the absence (EzrA control) or presence (EzrA + PC) of PC190723. Kymographs were obtained by extracting fluorescence intensity values along the black line indicated in cells in the left panels. Similarly to what was observed for FtsZ55-56sGFP, addition of PC190723 abolished EzrA movement (vertical lines in the kymographs). b, ColpSGEzrA-GFP cells were imaged by SIM every 5 min in the absence (left) or presence (right) of PC190723 and kymographs showing constriction of EzrA-GFP rings were plotted. In control conditions the larger EzrA rings showed biphasic constriction behaviour while in the presence of PC190723 only the rings in the second stage of cytokinesis were able to constrict. Data in (a, b) are representative of two biological replicates. Scale bars, 1 μm. c, To test the functionality of the EzrA-GFP construct, strains COL, ColpSGEzrA-GFP and COLΔEzrA (lacking ezrA) were imaged by phase contrast and cell area was measured. The lack of EzrA in COLΔEzrA (N=959) resulted in cell enlargement, while the size distribution of ColpSGEzrA-GFP (N=957) cells mimicked that of parental strain COL (N=851), indicating that the EzrA fluorescent fusion is functional.

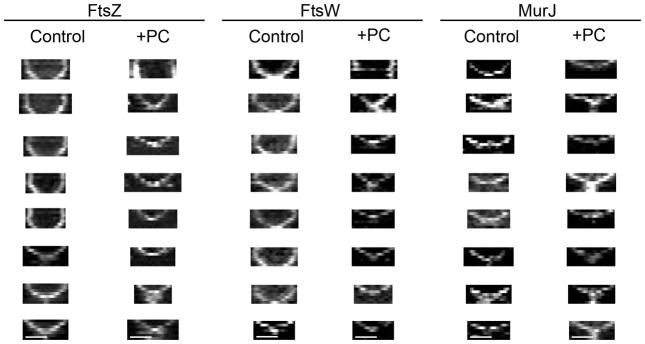

Extended Data Figure 8. Kymographs showing constriction of FtsZ55-56sGFP, FtsW-sGFP and MurJ-sGFP rings during cell division.

Strains ColFtsZ55-56sfGFP, ColFtsW-sGFP and ColMurJ-sGFP were imaged every 10 min in the absence (control) or presence (+PC) of PC190723 for a total of 60 min. MurJ-sGFP control kymographs were performed on cells where MurJ-sGFP signal appears on the second frame, to ensure that the entire constriction process was observed (i.e. that the absence of a biphasic behaviour did not result from only imaging cells in later stages of cell division). FtsZ55-56sGFP and FtsW-sGFP rings showed a biphasic constriction behaviour (no/slow constriction followed by fast constriction). Addition of PC190723 inhibited constriction of larger FtsZ55-56sfGFP and FtsW-sGFP rings (see top kymographs), but not of smaller rings which were undergoing fast constriction. MurJ-sGFP rings only displayed fast constriction and therefore were always able to constrict in the presence of PC190723. Data are representative of three biological replicates. Scale bars, 0.5 μm.

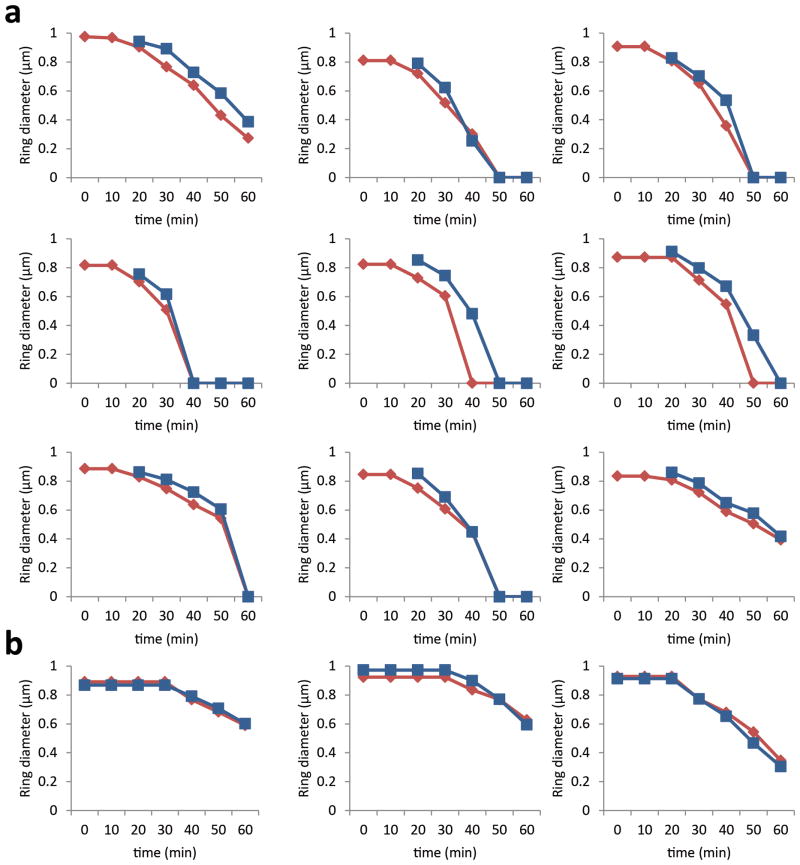

Extended Data Figure 9. Additional graphs of FtsZ, MurJ and FtsW ring diameter during constriction.

a, Graphs of ring diameters of FtsZ-mCherry (red lines) and MurJ-sGFP (blue lines) in strain ColJgZm. SIM images were taken every 10 min and measurements of ring diameter of FtsZ-mCherry and MurJ-sGFP were performed in cells where MurJ-sGFP signal first appeared after 20 minutes. b, Graphs of ring diameters of FtsZ-mCherry (red lines) and FtsW-sGFP (blue lines) in strain ColWgZm. SIM images were taken every 10 min and measurements of ring diameter of FtsZ-mCherry and FtsW-sGFP were performed in cells where FtsZ-mCherry ring diameter was constant for at least the first 20 minutes.

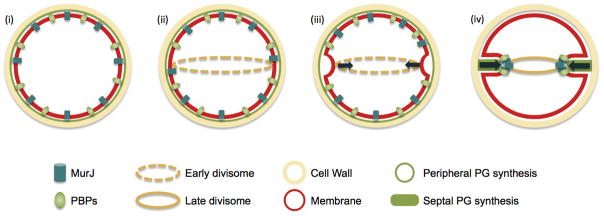

Extended Data Figure 10. Model for cytokinesis in S. aureus.

(i) Cells in Phase 1 of the cell cycle (before septum synthesis is initiated) synthesise peptidoglycan at the cell periphery. (ii) In preparation for division, FtsZ and early components of the divisome assemble at midcell. (iii) At this stage, cells initiate the first, slow step of cytokinesis, which is dependent on FtsZ treadmilling. FtsZ may be the driving force for the initial invagination of the membrane. (iv) MurJ then arrives to the divisome, in a process dependent on the presence of the sub-complex DivIB/DivIC/FtsL, bringing the PG precursor (lipid II) flippase activity to midcell. The major S. aureus PG synthase, PBP2, is recruited to midcell through substrate (translocated lipid II) recognition, and massive PG synthesis is initiated to synthesise the septum. From this point onwards, cytokinesis no longer depends on FtsZ treadmilling and is most likely driven by PG synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rita Sobral (FCT-NOVA) for the construction of pSG-murF plasmid; Ana Jorge (ITQB-NOVA) for the construction of the ColpSGEzrA-GFP strain; Terry Roemer (Merck) for kindly providing DMPI and strains AS-022 and AS-185; Matthew DeLisa (Cornell) for pTRC99a-P7, Richard Novick (NYU) for pCN51, Simon Foster (The University of Sheffield) for antibodies against DivIB and DivIC, Adriano Henriques (ITQB-NOVA) for critical reading of the manuscript and Ludwig Krippahl (FCT-NOVA) for help with image analysis tools. This study was funded by the European Research Council through grant ERC-2012-StG-310987 (to MGP), by Project LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-007660 Microbiologia Molecular, Estrutural e Celular (to ITQB-NOVA), by the National Institutes of Health through grant NIHGM113172 (to MVN) and FCT fellowships SFRH/BD/71993/2010 (JMM), SFRH/BD/86416/2012 (ARP), SFRH/BPD/95031/2013 (NTR), SFRH/BPD/87374/2012 (HV), SFRH/BD/52204/2013 (ACT) and SFRH/BD/77849/2011 (MTF).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

J.M.M., A.R.P., N.T.R. and M.G.P. designed the research. J.M.M., A.R.P. performed all experiments with the exception of the effect of antibiotics on the cell cycle which was performed by P.B.F.. B.M.S. developed software for image analysis. J.M.M., A.R.P, N.T.R., P.B.F., H.V., A.C.T, M.S., M.T.F., V.M. constructed strains. M.V.N. contributed with new reagents (HADA). J.M.M., A.R.P., N.T.R., S.F. and M.G.P. analysed the overall data. B.M.S. analysed microscopy data quantified by eHooke software. P.B.F. analysed cell cycle data. J.M.M., A.R.P, N.T.R. and M.G.P. wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Bibliography

- 1.Chastanet A, Carballido-Lopez R. The actin-like MreB proteins in Bacillus subtilis: a new turn. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:1582–1606. doi: 10.2741/s354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young KD. Bacterial shape: two-dimensional questions and possibilities. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:223–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bisson-Filho AW, et al. Treadmilling by FtsZ filaments drives peptidoglycan synthesis and bacterial cell division. Science. 2017;355:739–743. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang X, et al. GTPase activity-coupled treadmilling of the bacterial tubulin FtsZ organizes septal cell wall synthesis. Science. 2017;355:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Domínguez-Escobar J, et al. Processive movement of MreB-associated cell wall biosynthetic complexes in bacteria. Science. 2011;333:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1203466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garner EC, et al. Coupled, circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science. 2011;333:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1203285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinho M, Errington J. Dispersed mode of Staphylococcus aureus cell wall synthesis in the absence of the division machinery. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:871–881. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinho MG, Kjos M, Veening JW. How to get (a)round: mechanisms controlling growth and division of coccoid bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:601–614. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monteiro JM, et al. Cell shape dynamics during the staphylococcal cell cycle. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8055. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benson T, et al. X-ray crystal structure of Staphylococcus aureus FemA. Structure. 2002;10:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sham LT, et al. MurJ is the flippase of lipid-linked precursors for peptidoglycan biogenesis. Science. 2014;345:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.1254522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber J, et al. Chemical genetic identification of peptidoglycan inhibitors potentiating carbapenem activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Chem Biol. 2009;16:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi T, et al. Identification of FtsW as a transporter of lipid-linked cell wall precursors across the membrane. Embo J. 2011;30:1425–1432. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeske AJ, et al. SEDS proteins are a widespread family of bacterial cell wall polymerases. Nature. 2016;537:634–638. doi: 10.1038/nature19331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emami K, et al. RodA as the missing glycosyltransferase in Bacillus subtilis and antibiotic discovery for the peptidoglycan polymerase pathway. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:16253. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada A, Watanabe H. Penicillin-binding protein 1 of Staphylococcus aureus is essential for growth. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2759–2765. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2759-2765.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuru E, et al. In situ Probing of Newly Synthesized Peptidoglycan in Live Bacteria with Fluorescent D-Amino Acids. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12519–12523. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goehring NW, Gonzalez MD, Beckwith J. Premature targeting of cell division proteins to midcell reveals hierarchies of protein interactions involved in divisome assembly. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61:33–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Errington J, Daniel RA, Scheffers DJ. Cytokinesis in Bacteria. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2003;67:52–65. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.67.1.52-65.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gamba P, Veening JW, Saunders NJ, Hamoen LW, Daniel RA. Two-step assembly dynamics of the Bacillus subtilis divisome. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:4186–4194. doi: 10.1128/JB.01758-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donald RG, et al. A Staphylococcus aureus fitness test platform for mechanism-based profiling of antibacterial compounds. Chem Biol. 2009;16:826–836. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haydon DJ, et al. An inhibitor of FtsZ with potent and selective anti-staphylococcal activity. Science. 2008;321:1673–1675. doi: 10.1126/science.1159961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coltharp C, Buss J, Plumer TM, Xiao J. Defining the rate-limiting processes of bacterial cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E1044–1053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514296113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coltharp C, Xiao J. Beyond force generation: Why is a dynamic ring of FtsZ polymers essential for bacterial cytokinesis? Bioessays. 2017;39:1–11. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Son SH, Lee HH. The N-terminal domain of EzrA binds to the C terminus of FtsZ to inhibit Staphylococcus aureus FtsZ polymerization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;433:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levin PA, Kurtser IG, Grossman AD. Identification and characterization of a negative regulator of FtsZ ring formation in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9642–9647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinho MG, Errington J. Recruitment of penicillin-binding protein PBP2 to the division site of Staphylococcus aureus is dependent on its transpeptidation substrates. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:799–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Trimble MJ, Brun YV, Jensen GJ. The structure of FtsZ filaments in vivo suggests a force-generating role in cell division. EMBO J. 2007;26:4694–4708. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kraemer GR, Iandolo JJ. High-frequency transformation of Staphylococcus aureus by electroporation. Current Microbiology. 1990;21:373–376. doi: 10.1007/bf02199440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oshida T, Tomasz A. Isolation and characterization of a Tn551-autolysis mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4952–4959. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.4952-4959.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinho MG, Errington J. A divIVA null mutant of Staphylococcus aureus undergoes normal cell division. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2004;240:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nair DR, et al. Characterization of a novel small molecule that potentiates β-lactam activity against gram-positive and gram-negative pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1876–1885. doi: 10.1128/aac.04164-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mann PA, et al. Murgocil is a highly bioactive staphylococcal-specific inhibitor of the peptidoglycan glycosyltransferase enzyme MurG. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2442–2451. doi: 10.1021/cb400487f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnaud M, Chastanet A, Debarbouille M. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereira P, Veiga H, Jorge A, Pinho M. Fluorescent Reporters for Studies of Cellular Localization of Proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:4346–4353. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00359-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore DA, Whatley ZN, Joshi CP, Osawa M, Erickson HP. Probing for binding regions of the FtsZ protein surface through site-directed insertions: discovery of fully functional FtsZ-fluorescent proteins. J Bacteriol. 2017;199:e00553–00516. doi: 10.1128/jb.00553-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atilano M, et al. Teichoic acids are temporal and spatial regulators of peptidoglycan cross-linking in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18991–18996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004304107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jorge AM, Hoiczyk E, Gomes JP, Pinho MG. EzrA Contributes to the Regulation of Cell Size in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velasco F. Thresholding using the ISODATA clustering algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. 1980;10:771–774. doi: 10.1109/tsmc.1980.4308400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Falcão AX, Stolfi J, de Alencar Lotufo R. The image foresting transform: theory, algorithms, and applications. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2004;26:19–29. doi: 10.1109/tpami.2004.10012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roerdink J, Meijster A. The Watershed Transform: Definitions, Algorithms and Parallelization Strategies. Fundamenta Informaticae. 2000;41:187–228. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH. A practical guide to evaluating colocalization in biological microscopy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;300:C723–742. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Source data for figures 1–3 and 5 and Extended Data figures 1–4, 7 and 9 are provided with the paper.