Executive summary

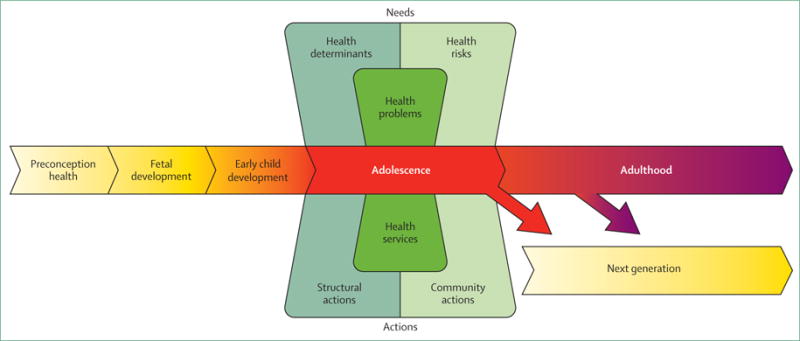

Unprecedented global forces are shaping the health and wellbeing of the largest generation of 10 to 24 year olds in human history. Population mobility, global communications, economic development, and the sustainability of ecosystems are setting the future course for this generation and, in turn, humankind.1,2 At the same time, we have come to new understandings of adolescence as a critical phase in life for achieving human potential. Adolescence is characterised by dynamic brain development in which the interaction with the social environment shapes the capabilities an individual takes forward into adult life.3 During adolescence, an individual acquires the physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and economic resources that are the foundation for later life health and wellbeing. These same resources define trajectories into the next generation. Investments in adolescent health and wellbeing bring benefits today, for decades to come, and for the next generation.

Better childhood health and nutrition, extensions to education, delays in family formation, and new technologies offer the possibility of this being the healthiest generation of adolescents ever. But these are also the ages when new and different health problems related to the onset of sexual activity, emotional control, and behaviour typically emerge. Global trends include those promoting unhealthy lifestyles and commodities, the crisis of youth unemployment, less family stability, environmental degradation, armed conflict, and mass migration, all of which pose major threats to adolescent health and wellbeing.

Adolescents and young adults have until recently been overlooked in global health and social policy, one reason why they have had fewer health gains with economic development than other age groups. The UN Secretary-General’s Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health initiated, in September, 2015, presents an outstanding opportunity for investment in adolescent health and wellbeing.4 However, because of limits to resources and technical capacities at both the national and the global level, effective response has many challenges. The question of where to make the most effective investments is now pressing for the international development community. This Commission outlines the opportunities and challenges for investment at both country and global levels (panel 1).

Panel 1. Messages, opportunities, and challenges.

Key messages

Investments in adolescent health and wellbeing bring a triple dividend of benefits now, into future adult life, and for the next generation of children.

Adolescents are biologically, emotionally, and developmentally primed for engagement beyond their families. We must create the opportunities to meaningfully engage with them in all aspects of their lives.

Inequities, including those linked to poverty and gender, shape all aspects of adolescent health and wellbeing: strong multisectoral actions are needed to grow the resources for health and wellbeing and offer second chances to the most disadvantaged.

Adolescents and young adults face unprecedented social, economic, and cultural change. We must transform our health, education, family support, and legal systems to keep pace with these changes.

Outstanding opportunities

Guaranteeing and supporting access to free, quality secondary education for all adolescents presents the single best investment for health and wellbeing.

Tackling preventable and treatable adolescent health problems including infectious diseases, undernutrition, HIV, sexual and reproductive health, injury, and violence will bring huge social and economic benefits. This is key to bringing a grand global convergence in health in all countries by 2030.

The most powerful actions for adolescent health and wellbeing are intersectoral, multilevel, and multi-component: information and broadband technologies present an exceptional opportunity for building capacity within sectors and coordinating actions between them.

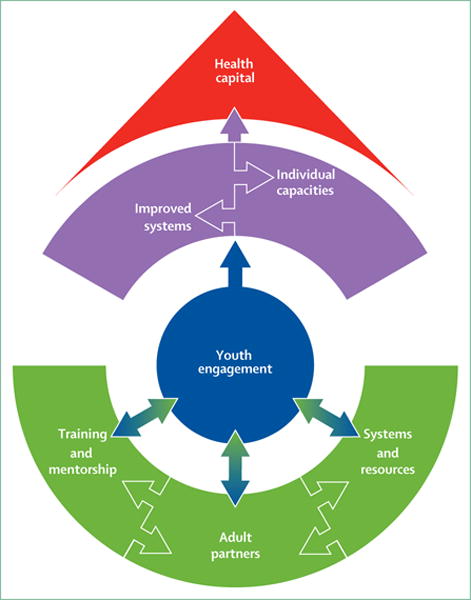

Establishing systems for the training, mentoring, and participation of youth health advocates has the potential to transform traditional models of health-care delivery to create adolescent-responsive health systems.

Challenges ahead

Rapid global rises in adolescent health risks for later-life non-communicable diseases will require an unprecedented extent of coordination across sectors from the global to the local level.

Non-communicable diseases of adolescents including mental and substance use disorders, and chronic physical illnesses are becoming the dominant health problems of this age group. Substantial investment in the health-care system and approaches to prevention are required.

Health information systems to support actions in adolescent health remain weak: greater harmonisation and broadening of data collection systems to neglected problems and younger ages will be needed.

Inequalities in health and wellbeing are evident in socially and economically marginalised adolescents, including ethnic minorities, refugees, young offenders, Indigenous, and LGBT adolescents; engagement of adolescents and reconfiguration of service systems to ensure equity of access regardless of sex, ethnic, or socioeconomic status will be essential.

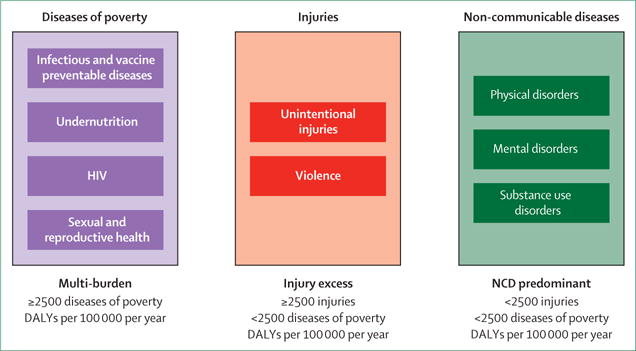

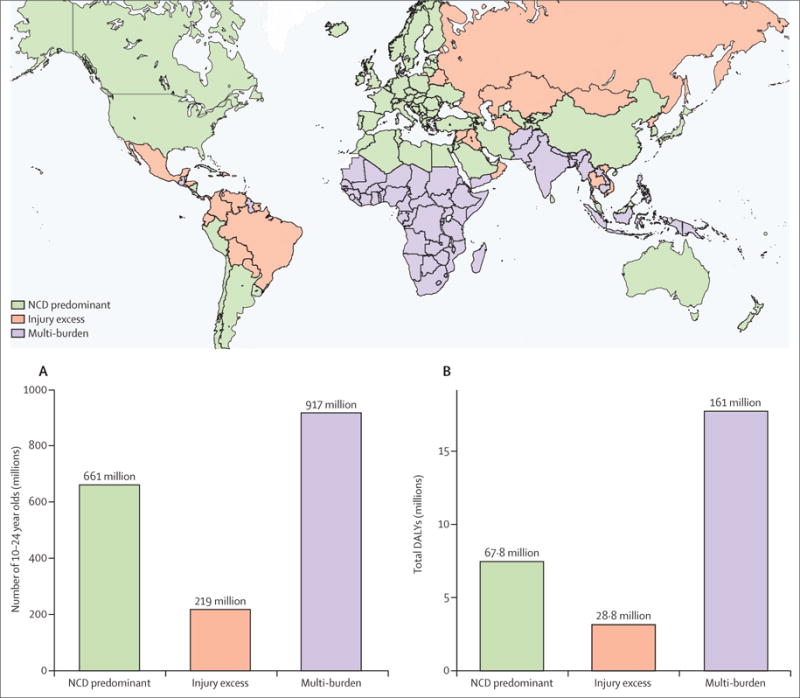

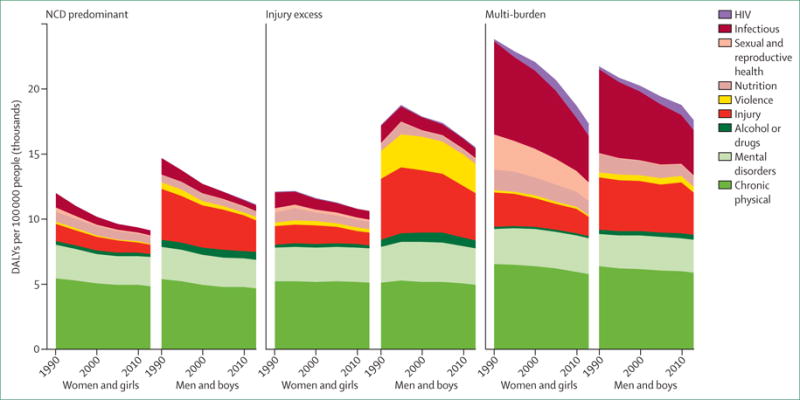

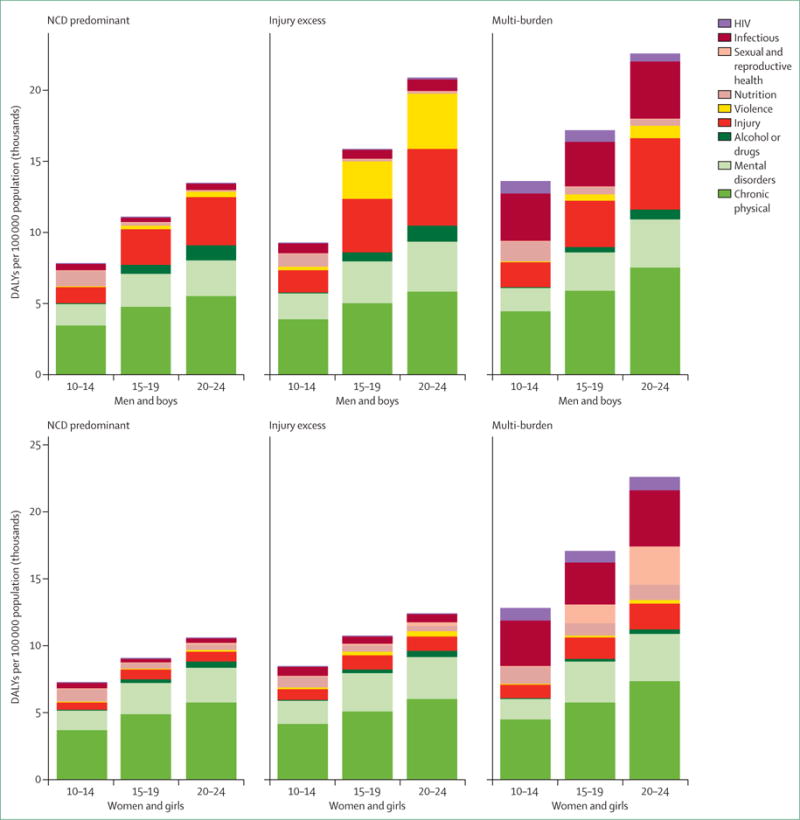

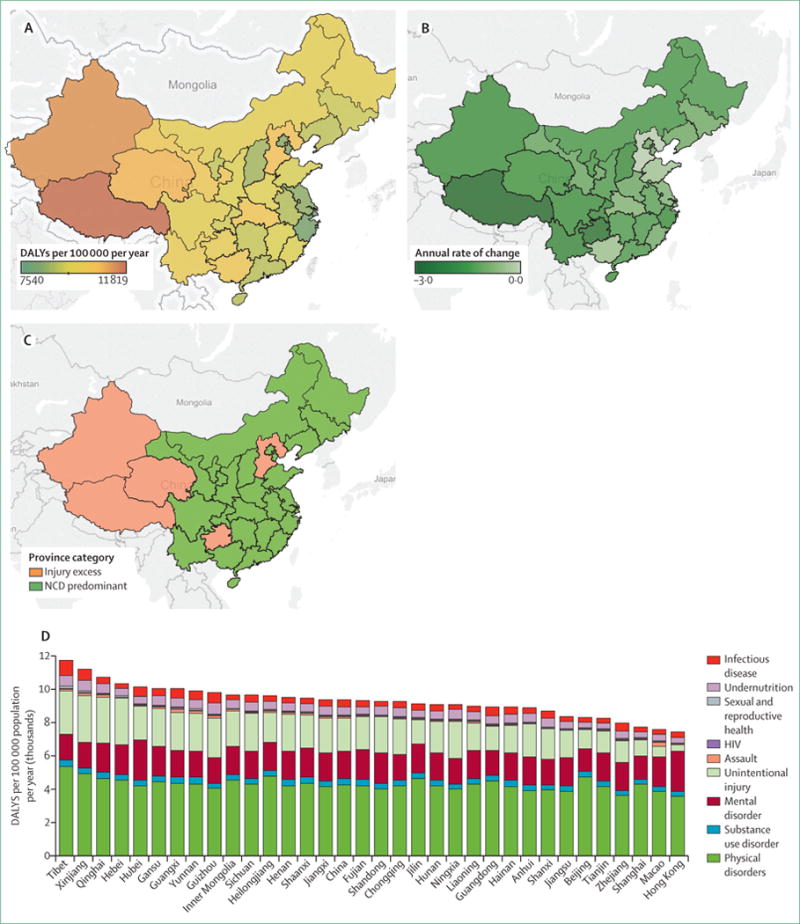

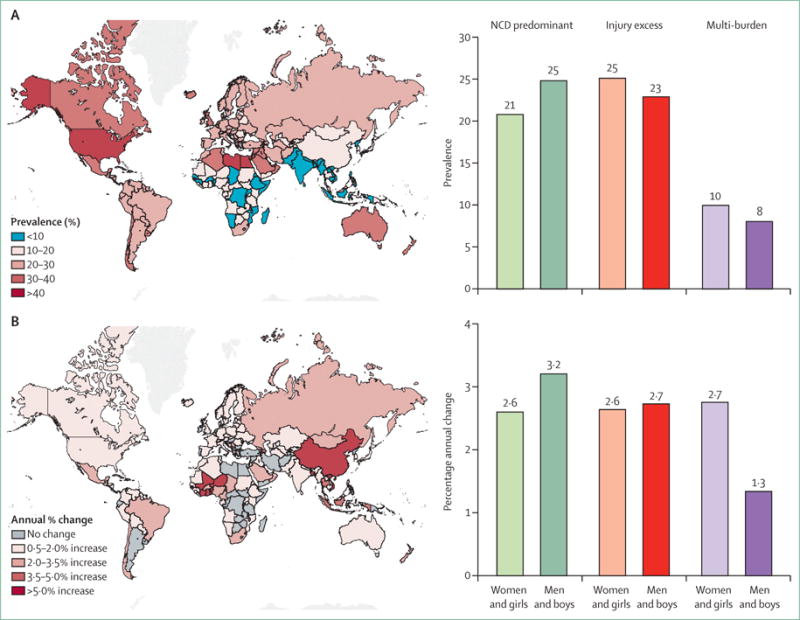

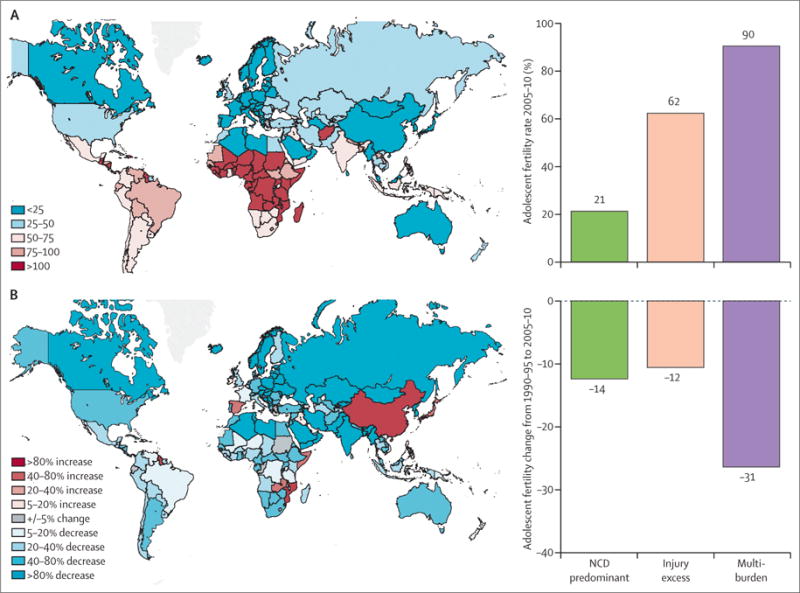

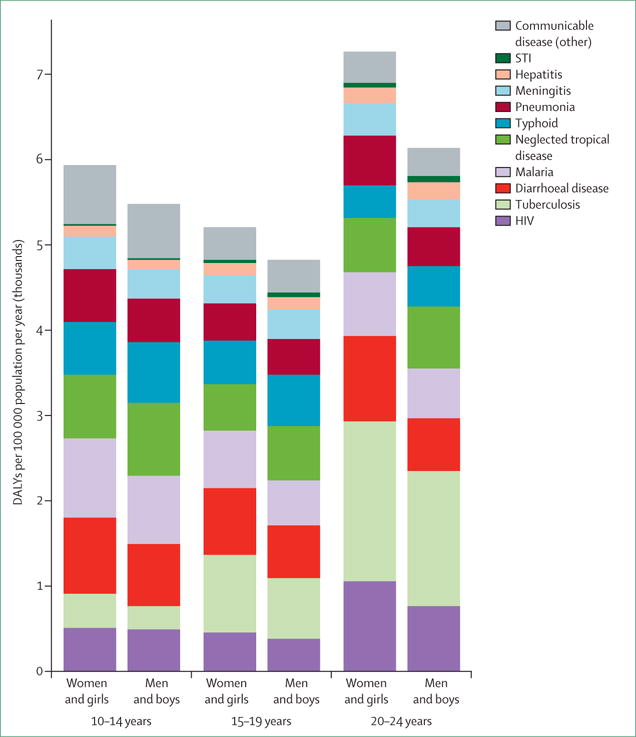

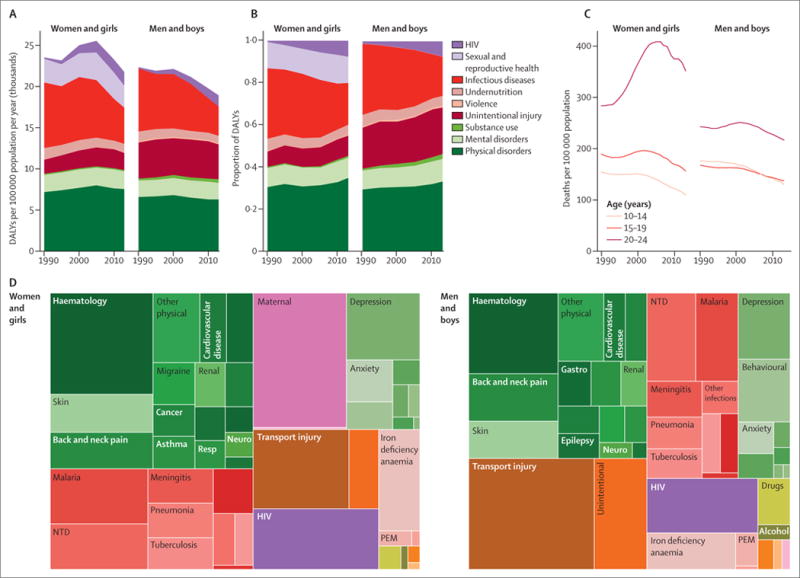

Adolescent health profiles differ greatly between countries and within nation states. These differences usually reflect a country’s progress through an epidemiological transition in which reductions in mortality and fertility shift both population structures and predominating patterns of disease. Just over half of adolescents grow up in multi-burden countries, characterised by high levels of all types of adolescent health problems, including diseases of poverty (HIV and other infectious diseases, undernutrition, and poor sexual and reproductive health), injury and violence, and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). These countries continue to have high adolescent fecundity and high unmet need for contraception, particularly in unmarried, sexually active adolescents. For these countries, addressing the diseases of poverty is a priority, at the same time as putting in place strategies to avoid sharp rises in injury, mental disorders, and NCD risks. One in eight adolescents grow up in injury excess countries, characterised by high persisting levels of unintentional injury or violence and high adolescent birth rates, and have generally made little progress in reducing these problems in recent decades. For this group of countries there is a need to redouble efforts to reduce injury, violence, and adolescent births as well as avoid sharp rises in mental disorders and NCD risks. Just over a third of adolescents grow up in countries that are NCD predominant, where the major adolescent burden lies in mental and substance use disorders, and chronic physical illness. For this group, the priority is now about universal health coverage and finding effective and scalable prevention strategies for these neglected conditions.

Adolescents and young adults have many unmet needs for health care, and experience barriers that include their inexperience and lack of knowledge about accessing health care, and heightened sensitivity to confidentiality breaches. Further barriers arise from restrictive legislative frameworks, out-of-pocket costs, stigma, and community attitudes. Health-care providers need attitudes, knowledge, and skills that foster engagement with adolescents while maintaining a level of engagement with families. Universal health coverage requires accessible packages of care matched to local need and acceptable to adolescents and young adults. The most effective health service systems include high-quality health worker training, adolescent responsive facilities, and broad community engagement.

Laws have profound effects on adolescent health and wellbeing. Some protect adolescents from harms (eg, preventing child marriage); others could be damaging in limiting access to essential services and goods such as contraception. Although nearly all countries have signed and ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, there are profound differences in the legal frameworks underpinning adolescent health across countries. Even where national legal frameworks exist, customary or religious laws often take precedence, leaving the rights of adolescents to health too often neglected and undermined.

The expansion of secondary education in many countries, particularly for girls, offers remarkable opportunities for health and wellbeing. Participation in quality secondary education enhances cognitive abilities, improves mental health and sexual and reproductive health, and lowers risks for later-life NCDs. Schools also provide a platform for health promotion that extends from the provision of essential knowledge for health, including comprehensive sexuality education, to maintaining lifestyles that minimise health risks. Equally, avoiding early pregnancy, infectious diseases, mental disorder, injury-related disability, and under-nutrition are essential for achieving the educational and economic benefits that extensions to secondary school offer.

Digital media and broadband technologies offer outstanding new possibilities for engagement and service delivery. Adolescents are biologically, emotionally, and developmentally primed for engagement beyond their families. That engagement is essential for their social and emotional development. It is also a force for change and accountability within communities. Social networking technologies have the potential to galvanise, connect, and mobilise this generation as never before. We must create opportunities to extend youth engagement into the real world. This requires financial investment, strong partnerships with adults, training and mentorship, and the creation of structures and processes that allow adolescent and young adult involvement in decision making.

The most effective actions for adolescent health and wellbeing are intersectoral and multi-component. They could include structural, media, community, online, and school-based elements as well as the provision of preventive and treatment health services. The neglect of adolescent health and wellbeing has resulted in minimal investments in programming, human resources, and technical capacity compared with other age groups. As a consequence there are major gaps in our understanding of adolescent health needs, in the evidence base for action, in civil society structures for advocacy, and the systems for intersectoral action. Within any country there are marked differences in health between different regions and within different adolescent groups, with poverty, gender, and social marginalisation important determinants. Groups such as ethnic minorities, LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) youth, those with disabilities, or who are homeless or in juvenile detention have the greatest health needs. Sound information underpins any efficient response. Yet because information systems on health and wellbeing are piecemeal, the needs of these groups are invisible and unmet. A capacity to understand local health needs inclusive of all adolescents, regardless of age, sex, marital status, or socioeconomic status, is essential.

In the face of global change, continued inaction jeopardises the health and wellbeing of this generation and the next. But there are grounds for optimism. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health offers a framework to drive and coordinate investment, capacity building, research, and evaluation.4 Global strategies to extend education, to reduce gender inequalities and empower women, to improve food security and nutrition, and to promote vocational skills and opportunities for employment are all likely to benefit adolescents and young adults.5 Digital technologies and global communications offer exceptional opportunities for catch-up in training and education, creation of inclusive health information systems, meaningful youth engagement, and cooperation across sectors. This generation of adolescents and young adults can transform all of our futures; there is no more pressing task in global health than ensuring they have the resources to do so.

Introduction

The second Lancet Series on adolescent health concluded that a “Failure to invest in the health of the largest generation of adolescents in the world’s history jeopardises earlier investments in maternal and child health, erodes future quality and length of life, and escalates suffering, inequality, and social instability”.6 The response of the international development community to this and other calls has been striking. From September, 2015, the Every Woman, Every Child agenda has become the Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health, supported by a Global Financing Facility.4 This Commission on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing outlines where those investments should be in the years to 2030.

This Commission was established as a network of academics, policy makers, practitioners, and young health advocates with broad expertise in adolescent health. We brought together leading academic institutions in global health (Columbia University, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University College London, and the University of Melbourne). The Commission’s 30 members bring experience from Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, the Middle East, North America, and South America. They represent diverse disciplines including public health and medicine, behavioural and neuroscience, education, law, economics, and political and social science.

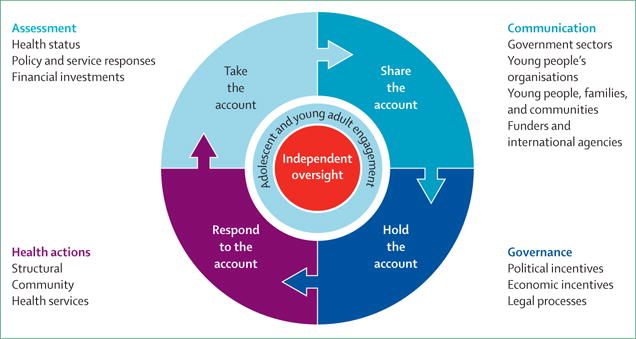

First, we consider the place of adolescent health within the life course, with particular reference to the health capital that accrues or is diminished across these years. We also consider the global forces shaping adolescent and young adult health and our new understanding of healthy development across these years. In the section, Enabling and protective systems, we consider the rapidly changing social and structural determinants of adolescent health and their implications for health promotion and prevention. In the section, The global health profile of adolescents and young adults, we used available data on adolescent and young adult health to provide a global profile that takes into consideration the differing health needs of adolescents as their countries pass through the epidemiological transition. Actions for health summarises a series of reviews of reviews of our current knowledge base for action in adolescent health, concluding with an example of matching country level actions to health needs. We also consider the different roles of health service systems for adolescents. In the section, Adolescent and young adult engagement, we consider models for youth engagement and for accountability in adolescent health and wellbeing. The Commission’s recommendations are detailed in the conclusion.

Adolescence was historically considered to begin with puberty, and to end with transitions into marriage and parenthood.7 In today’s context, the endpoints are often less clear-cut and more commonly around the adoption of other adult roles and responsibilities, including the transition to employment, financial independence, as well as the formation of life partnerships. These events occur at different ages in different parts of the world and local cultural concepts of adolescence vary greatly. Given this variability we have adopted an inclusive age definition of 10 to 24 years for this report. Panel 2 summarises terms that are commonly used to describe this age group.8–10 In general we use the terminology of adolescents and young adults, although in some instances we abbreviate this to adolescents. Given that the field commonly uses the terms youth engagement and youth participation, we have retained these terms.

Panel 2. Definitions of adolescence and young adulthood.

Adolescence is defined by WHO as between 10 and 19 years, while youth refers to 15–24 years. Young people refers to the 10–24-year-old age group, as does the composite term adolescents and young adults. This is the age group and term that is used through the Commission report.

Emerging adulthood has been used to describe the phase of life from the late teens to the late twenties when an individual acquires some of the characteristics of adulthood without having reached the milestones that historically define fully fledged adulthood.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) defines a child as below the age of 18 years, unless majority is attained earlier under the laws applicable to the child.

The legal age of majority, the point at which an individual is considered an adult, in many countries is 18 years. In law there is no single definition of adulthood but rather a collection of laws that bestow the status of adulthood at differing ages for different activities. These include laws related to the age of consent, the minimum age that young people can legally work, leave school, drive, buy alcohol, marry, be held accountable for criminal action, and the age young people are deemed able to make medical decisions.

When reporting age-disaggregated data, the 10–24-year-old age range is increasingly divided into 5-year age categories. Early adolescence refers to 10–14 years, late adolescence to 15–19 years, and young adulthood to 20–24 years.

Definitions of wellbeing are diverse and range from the subjective to more objective. We adopted a broad, capabilities-based approach to wellbeing, emphasising adolescents’ opportunities to achieve developmentally important goals (eg, access to education, opportunities for civic engagement) in the context of their emerging physical, emotional, and cognitive abilities.11,12

Why adolescent health and wellbeing?

Adolescence is often considered the healthiest time of life. In most countries, adolescence is the point of lowest mortality across the life course, sitting between the peaks of early life mortality and of chronic disease in later adulthood. It is a time where many attributes of good health are at their height,13 and from the perspective of health services, adolescents appear to have fewer needs than those in early childhood or in later years. This dominant view of adolescent health has been the reason why adolescents and young adults have attracted so little interest and investment in global health policy.

However, even from a perspective of conspicuous health needs, there has been a shift in attitude towards adolescents and their health.14 Changes in the health of other age groups is one reason. Mortality has fallen sharply in younger children in high-income and middle-income countries compared with older adolescents and young adults.15 By 2013, mortality in 1 to 4 year olds had fallen to around a quarter of 1980 levels (appendix figure 1). By contrast, deaths in 20 to 24 year olds had only fallen to around 60% of 1980 levels. Deaths in many high-income and middle-income countries are now higher in older male adolescents and young male adults than in 1 to 4 year olds.15

From three perspectives, adolescence and young adulthood have an altogether different significance. Firstly, health and wellbeing underpin the crucial developmental tasks of adolescence including the acquisition of the emotional and cognitive abilities for independence, completion of education and transition to employment, civic engagement, and formation of lifelong relationships. Secondly, adolescence and young adulthood can be seen as the years for laying down the foundations for health that determine health trajectories across the life course. Lastly, adolescents are the next generation to parent; these same health reserves do much to determine the healthy start to life they provide for their children.

The adolescent and young adult years are central in the development of capabilities related to health and wellbeing. These emergent capabilities are dependent on available opportunities (eg, availability of a school), having the resources to use those opportunities (eg, family finances that allow school attendance), and for those who have been socially marginalised, access to second chances (eg, access to education for married girls who have left school).16 Adolescents with longer participation in education, fewer health risks, and slower transitions into marriage and parenthood generally accrue greater capabilities and resources for health. Conversely, early marriage and parenthood, little education, and early exposure to economic and social adversity are likely to diminish an individual’s health and capabilities. Premature autonomy with early disengagement from parents and school and high levels of health risk behaviours predict poorer health and wellbeing.17 The extent to which an individual’s health and wellbeing is fostered or compromised during these years has consequences across the life course as well as influencing the healthy start to life of the next generation.18

Health capital is the set of resources that determine trajectories of health across the lifecourse,19 which typically peak during adolescence and young adulthood. Physical fitness peaks around the age of 20 and remains high until the early 30s when it declines steadily through to old age.20 Those with the highest fitness levels in their 20s are more likely to stay physically healthy throughout life, with less health service use as they age.20 Adolescent cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, and body composition are also predictive of lower rates of all-cause mortality and lower rates of cardiovascular disease in later life than in those who are less fit.21 Adolescence is similarly central in skeletal health. Bone mineral density, a primary determinant of later-life osteoporosis and its complications, peaks in the late teens to early 20s.22 In the 2 years of peak skeletal growth, adolescents accumulate over 25% of their adult bone mass, with patterns of physical activity and adolescent nutrition important modifiable influences.23,24

A growing understanding that neurodevelopment extends across the second and into the third decade of life has implications for both adolescent health and the capacities that underpin wellbeing across the life course (panel 3).25–34 Many cognitive abilities increase markedly from late childhood to peak in the early 20s and then undergo slow decline from the early 30s.35 Analogous to physical health, educational attainment between late childhood and the mid-20s is a strong and independent predictor of cognitive capacity in midlife.36 These cognitive reserves predict later-life physical health and longevity37 and are protective against cognitive decline.36 Equally, maturation of the neural systems underpinning emotional processes might be one reason for higher risks for mental and substance use disorders during these years.38 Maturation of these systems similarly has profound implications for emotional development and the capacities that adolescents bring into their future roles as parents, citizens, and workers.39

Panel 3. Psychological and emotional development through adolescence.

Early adolescence (10–14 years) is biologically dominated by puberty and the effects of the rapid rise in pubertal hormones on body morphology, and sexual and brain development. Adolescence is a time of remodelling of the brain’s reward system. Psychologically it is characterised by low resistance to peer influences, low levels of future orientation, and low risk perception, often leading to increases in risk taking behaviour and poor self-regulation. It is a time of identity formation and development of new interests including emerging interest in sexual and romantic relationships. School and family environments are critical social contexts during this period.

Late adolescence (15–19 years) is also characterised by pubertal maturation, especially in boys, but in ways that are less visually obvious. At this time the brain continues to be extremely developmentally active, particularly in terms of the development of the prefrontal cortex and the increased connectivity between brain networks. This later phase in adolescent brain development brings continued development of executive and self-regulatory skills, leading to greater future orientation and an increased ability to weigh up the short-term and long-term implications of decisions. Family influences become distinctly different during this phase of life, as many adolescents enjoy greater autonomy, even if they still live with their families. Likewise, education settings remain important, although not all adolescents are still engaged in school at this age, especially in low-income and middle-income countries.

Young adulthood (typically 20–24 years) is accompanied by maturation of the prefrontal cortex and associated reasoning and self-regulatory functions. It marks the end of a period of high brain plasticity associated with adolescence whereby the final phase of the organisation of the adult brain occurs. This often corresponds to the adoption of adult roles and responsibilities, including entering the workforce or tertiary education, marriage, childbearing, and economic independence. Secular trends in many developed nations point towards an increase in the age that many of these adult roles are attained, if they are attained at all.

Adolescence and young adulthood are also the years in which an individual establishes the social, cultural, emotional, educational, and economic resources to maintain their health and wellbeing across the life course.40 Hormonal changes that lead to sexual maturation commence with adrenarche in mid-childhood, and continue through puberty. This is a time of adaptation to social and cultural complexity and the point at which gender differences in social and emotional styles, including gender roles, typically crystallise. The foundations for success in the transitions to an independent healthy lifestyle, to employment, and to supportive life partnerships, marriage, and parenthood are also laid in these years.16

Conversely, adolescent health problems and health risks diminish peak fitness and lifetime health. Sexual health risks that result in teenage pregnancy have profound effects on the health and wellbeing of young women across the life course. Pregnancy (and early marriage) typically denotes the end of formal education, restricts opportunities for employment, heightens poverty, and might limit growth in undernourished girls.41 In many countries of low and middle income, adolescents and young adults remain at high risk for infectious diseases, such as HIV that now commonly has a chronic course, while others such as meningitis, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases can similarly have major and persisting effects on health, social and economic adjustment, and wellbeing, albeit for different reasons.42 A range of health risks including tobacco and alcohol use, greater sedentary behaviour, diminished physical activity, increasing overweight, and obesity emerge across adolescence and young adulthood, reducing fitness and ultimately posing major risks for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in later life.43 Mental disorders commonly emerge during these years with many persisting into adulthood with consequences for mental health across the life course, social adjustment, and economic productivity.44 Substance use during adolescence diminishes fitness, increases risks for many later-life NCDs, and heightens the risk for later substance use disorders.45 Some forms of substance use can also affect adolescent cognitive development and ultimately reduce peak cognitive abilities.46 Injuries, both intentional and unintentional, disproportionately affect adolescents and young adults. They are not only a common cause of adolescent and young adult death in many countries, but also a major cause of disability, including acquired brain injury, leading to diminished health capacity that persists across the life course.

These same resources that underpin life course health and wellbeing are primary determinants of the health and development of the next generation of children. Maternal preconception nutritional deficiencies, whether micronutrients (eg, folate) or macronutrients (eg, protein energy malnutrition), have profound consequences for fetal and infant development with the effects extending to neonatal and early childhood mortality, and stunting.47 Chronic adolescent infectious diseases such as HIV, and chronic physical conditions such as type 1 diabetes mellitus and congenital heart disease require proactive management from adolescence into pregnancy. Adolescent obesity, tobacco and alcohol use, and mental health problems are similarly risks for poor pregnancy outcomes in infants as well as in mothers.48,49 A possibility of trans-generational epigenetic inheritance, whereby preconception influences alter patterns of gene expression that might pass to the next generation, has further heightened interest in preconception parent health, behaviours, and nutrition.50 From this perspective, investment in adolescent health and wellbeing, including lifestyles, knowledge, social, and financial resources for health, can equally be seen as an investment in the next generation.51

In many countries, the focus of health policy is shifting from infectious diseases in early life to NCDs in older adults.52 The life course trajectories of health capital and wellbeing are largely set by young adulthood. The case for optimising health, fitness, and capabilities as well as minimising risks to health and wellbeing are reasons to bring adolescents into sharper focus,18 as is the knowledge that inequalities established by young adulthood persist and account for many of the disparities in health (including cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and other NCDs) and wellbeing in later life.

Developing adolescent brains

Neuroscience is shedding new light on changing cognitive and emotional capacities across adolescence. Adolescence can now be understood as a dynamic period of brain development, second only to infancy in the extent and significance of the changes occurring within neural systems (panel 3).53 Much of the research that has led to this understanding has only emerged in the last 20 years. Adolescent brain development differs from that in earlier life, both in its form and regions of greatest activity. It follows the childhood increase in dendritic outgrowth and synaptogenesis and is then characterised by synaptic pruning during the second decade that continues into young adulthood. Pubertal processes, including gonadal hormone changes, have been implicated in maturation of subcortical structures with dimorphic patterns that might be relevant to understanding sex differences in the pattern of mental and behavioural disorders that emerge during adolescence.54 Neurodevelopment is also considerably affected by social and nutritional environments, as well as by exposures, such as substance use.6

Adolescent neurodevelopment has far-reaching implications for the influence of social environments on health.6 The capacity for greater social and emotional engagement that emerges around puberty is likely to have had adaptive advantages in the social contexts in which modern humans evolved.55 Plasticity in neurodevelopment underpins the acquisition of culturally adapted interpersonal and emotional skills that are essential for the more complex social, sexual, and parenting roles that until recently occurred soon after pubertal maturation.56 These biological foundations of adaptive learning also underpin the acquisition of health and human capital from late childhood through to young adulthood. However, the social networks and roles of adolescents today differ markedly from those of earlier, historical environments. The quality, security, and stability of social contexts in which younger adolescents are growing up is likely to be particularly important for the acquisition of skills in emotional processing and social cognition (eg, the capacity to infer the thoughts, intentions, and beliefs of others).28 It is perhaps not surprising that late childhood and early adolescence are often when the first symptoms of most mental disorders emerge.

The ways in which adolescents make decisions, including those affecting their health, differ from those of older adults. One notable difference is the effect of peer presence that affects the processing of social information, with a consequent greater sensitivity to reputational enhancement and damage.57 This sensitivity develops in the transition through puberty and is likely to have had adaptive advantages in an evolutionary context. It is in part related to the way in which younger adolescents differ in terms of a heightened response to the emotional displays of others,58 and is one reason why adolescents spend increased time with peers.59

In a contemporary context, there are often marked differences between peer and family values. The great salience of peers means that for adolescents, peer influences on health and wellbeing are greater than at any other time in the life course.6,60 This sensitivity to peers in decision making is often targeted by teen-oriented entertainment and marketing. In this way the media, particularly social media, shapes attitudes, values, and behaviours in this age group more than any other.61 The media’s contribution to adolescent sexual health risks in east Asian cities, for example, is equivalent to the influence of peers, families, or schools.62 In health promotion and prevention, just as in marketing, interventions that affect the attitudes, values, and behaviours of the peer group are likely to be more powerful than at any other point in the life course.

When making decisions, adolescents seek out and are more influenced by exciting, arousing, and stressful situations compared with adults.27 Adolescents differ from adults in their capacity to over-ride so called hot emotions that arise in emotionally charged situations. This is particularly relevant in the context of sexual activity and one of the reasons why cool-headed intentions fail to predict adolescent behaviour. It is an important reason why relying on condoms for contraception is not wholly effective. It is also one reason why interventions that either avoid hot emotions or are effective irrespective of the emotional context are important. One example is long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs), such as IUDs and implantable contraceptives. The effectiveness of LARCs (that have a 0·2% per annum failure rate in the USA, in comparison to 18·0% for condoms) reflects their consistent presence regardless of the sexual and emotional context.

Adolescent predisposition to sensation seeking is relevant in considering the effects of the digital technology revolution. Adolescents are rapid adopters and high-end consumers of exciting digital and social media.63 Girls tend to use social media more than boys, whose focus is more likely to be on gaming.63 There are potentially great benefits from strong social digital connections during this time, but these same media can equally amplify vulnerabilities from intense emotions.64 The potential of the new media to amplify social contagion is already apparent around adolescent violence, mental health, suicide, and self-harm.65 Extremist groups are increasingly using social media to offer prospects of adventure, belonging, and fulfilment that many adolescents find missing in ordinary life.66

Ultimately, actions to support adolescent health, development, and wellbeing should consider decision-making processes. An adolescent’s perception of their power and agency affects the balance between short-term and long-term goal setting.67 Supporting an adolescent’s capacity to make reflective decisions, considering risks and consequences, has been called “autonomy-enhancing paternalism”.68 Progressively empowering adolescents in decision making as they mature also affects their perception of agency around health. These strategies are particularly important for socially marginalised adolescents such as adolescent girls in contexts of gender inequality. Creation of a sense of agency is an important reason that there is value in creating opportunities for adolescents to exercise self-determination through meaningful participation, supported and facilitated by adults, in decision making that affects their lives and their communities.

The demographic transition and changes in adolescence

The demographic transition describes a country’s shift from high birth and death rates to low fertility, low mortality, and longer life expectancy. The process comes about as a result of economic development. The demographic transition began in many of today’s high-income countries after the Industrial Revolution and is now proceeding rapidly in most countries. This transition is typically accompanied by an epidemiological transition with reductions in maternal mortality, falling rates of infectious disease, and greater child survival into adolescence. One consequence of the demographic and epidemiological transitions has been the survival into adolescence of the largest cohort of adolescents and young adults, relative to other ages, that the world has ever seen (figure 1). The around 1·8 billion people aged 10–24 years represent almost a quarter of the world’s population.70

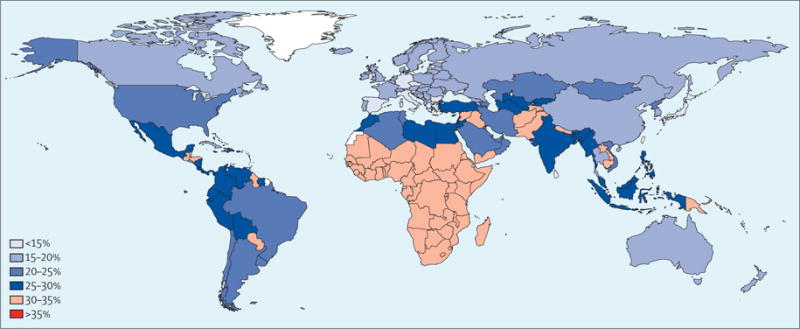

Figure 1. Adolescents and young adults as a proportion of country population in 2013.

Percentage of total country population aged 10–24 years. Data from Global Health Data Exchange.69

The demographic transition is, in turn, linked to a decline in the ratio of dependants (children and the elderly) to those in the active workforce. This lowered dependency ratio presents a potential demographic dividend for countries to expand their economies and reduce poverty. Although the demographic dividend has now passed for many of today’s high-income countries, it still lies ahead for many low-income countries. The health and human capital of today’s adolescents will be a determinant of future economic and social development in these countries.71

The demographic transition has typically been accompanied by changing patterns of adolescent growth and social development. One consequence of changing patterns of childhood infectious disease and nutrition is a fall in the age of onset of puberty in many countries.72 Conversely, transitions to marriage and parenthood are taking place later than in previous generations. As a result, adolescence now takes up a larger proportion of the life course than ever before. This expansion places adolescence more centrally in the creation of health and human capital than ever before. The greater duration of contemporary adolescence, particularly in the context of rapidly changing consumer and youth cultures, increases the possibility of health risks emerging during these years, with detrimental consequences well into later life.

In pre-industrial societies, the gap between physical maturation and parenthood was generally around 2 years for girls and four years for boys.56 Adolescence was not specifically recognised as the distinct phase of life that it is now in most high-income and middle-income countries. In many high-income countries, first marriage and parenthood now commonly occur 10 to 15 years after the onset of puberty. Indeed, a transition to heterosexual marriage in many places is being replaced by other forms of stable union, including cohabitation and same-sex partnerships. Inter-related drivers of this upward extension of adolescence include economic development, industrialisation, length of education, and urbanisation.73 There are often differences in the timing of the transitions into marriage and parenthood between adolescents in wealthier urban settings compared with those in poorer rural settings, especially in countries of low and middle incomes. In a growing number of countries in which marriage and parenthood are very delayed or where it is no longer rare for marriage or parenthood not to occur, these events no longer signal the end of adolescence.74 Traditional linear sequences of social role transitions such as finishing school, getting a job, getting married, and having children are also increasingly less well defined.74

Changes in the timing and duration of adolescence are accompanied by dramatic alterations in patterns of health risk, particularly around sexual and reproductive health. A delayed transition into marriage and parenthood in high-income and middle-income countries has brought great benefits for young women. When accompanied with ready access to modern contraception, good antenatal care, and legal and safe abortion, the shift has brought extraordinary reductions in maternal mortality and morbidity. Opportunities have opened to extend education and take advantage of social contexts well beyond the immediate family and community, which, in turn, brings greater maturity and experience to later parental roles, in addition to the huge contribution to economic development. Conversely, earlier age of first sexual intercourse and later marriage have created new vulnerabilities, particularly in sexual health, where a pattern of premarital serial sexual relationships creates a period of vulnerability to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unplanned pregnancy.75 These changing patterns of risk could be further heightened with the availability of new social media that promote casual sexual intercourse.76

In the past, transitions into marriage and child-rearing were assumed to be a safe haven as they were accompanied by a maturing out of health risks, with benefits including reduced tobacco, alcohol, and illicit substance use, particularly for young men.77 Yet, for many young women, the transition to marriage is accompanied by increasing sexual and reproductive health risks including HIV and sexually transmitted infections, interpersonal violence, and mental disorders.78 With delayed and falling rates of marriage, as well as a growth in other partnerships, the historic benefits of marriage on health risks could diminish. The demographic transition has in many countries been accompanied by changing health risks in adolescents that carry forward into later life. Perhaps the most striking has been a shift from undernutrition and growth stunting to increasing rates of obesity. First in high-income countries and now in countries of low and middle income, there has been a dietary switch toward greater consumption of foods high in addded sugars, salt, and unhealthy fats, and low in important micronutrients. Combined with decreases in physical activity, these patters have fuelled the global rise in obesity.

Adolescents in many countries are also initiating health risk behaviours related to alcohol and other substance use at an earlier age. An additional change is the increasing participation of girls in these same behaviours, continuing into childbearing years. Girls are increasingly coming to marriage and parenthood with more established and heavier patterns of alcohol and other substance use. In the absence of pregnancy planning, these shifting patterns of adolescent health risks create distinct risks for maternal health and fetal development from the preconception through to the postnatal period.79

Enabling and protective systems

Adolescent development takes place within a complex web of family, peer, school, community, media, and broader cultural influences.55 Puberty triggers greater engagement beyond an individual’s family, with a shift to peers, youth cultures, and the social environments created and fostered by new media. This wider social engagement is an important aspect of healthy development in which young people test the values and ideas that have shaped their childhood lives.28 Not only is the range of social influences greater and more complex, but also an extended adolescence increases the duration of their effect into young adulthood and ultimately their significance for health and wellbeing.

Beyond local and national trends, powerful global megatrends increasingly shape the evolution of society, health, and individual development.1 These include growth in educational participation, global patterns of economic development and employment, technological change, changing patterns of migration and conflict, growing urbanisation, political and religious extremism, and environmental degradation. The adolescent and young adult years are increasingly shaped by these global shifts, for better and for worse. For example, growing up in urban settings might lessen family poverty and bring better access to education and health services. Conversely, urban upbringing can heighten risks for mental health problems, substance use, obesity, and physical inactivity. Urban migration might involve whole families, parents, or young people alone, bringing different degrees of separation from the support of family and community. For adolescents living outside of families, urban settings can bring additional risks of sexual exploitation, unsafe employment, and human trafficking.

The digital revolution has the potential to transform the social environment and social networks of today’s adolescents. It has brought mobile phones to the great majority of young people, even in countries of low and middle income.80 The potential benefits in terms of economic development, education, health care, and promotion of democracy are great.1 For adolescents and young adults, new media promote access to an extended social network, without geographic or cultural constraints, bringing the potential for engagement with new ideas and like-minded individuals. Yet the digital revolution also brings new risks for adolescent health. Digital media have extended the marketing of unhealthy commodities and promoted stronger consumer cultures which in turn affect lifestyles, health, and wellbeing.81 Access to global media could accentuate the experience of economic disadvantage as adolescents come to understand the extent of material advantage elsewhere. Online safety has emerged as a further concern, especially for younger adolescents. Experiences of cyber-bullying, grooming for sex, sharing of sexual images, and social contagion around self-harm; mass shootings; radicalisation; and eating disorders have the potential to cause great harm.82 Rising rates of adolescent sleep disturbance and addiction to gaming have also been linked to the new media.83

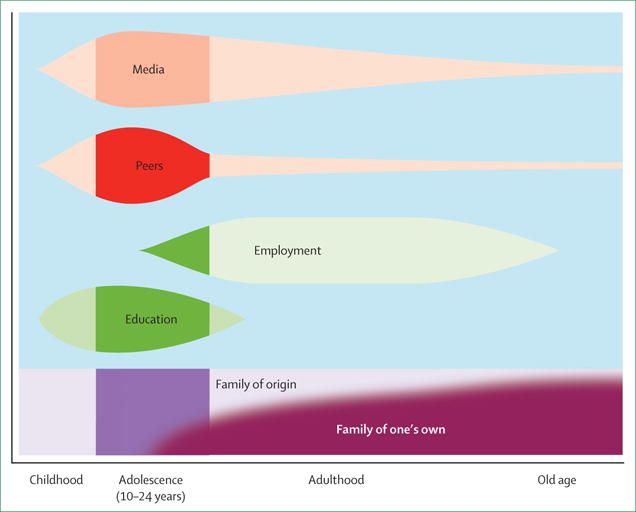

The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, develop, live, work, and age.55 Within the lifecourse, adolescence is the time of greatest change and diversity in exposure to social determinants, particularly those closest to young people (figure 2). The influence of families remains strong, although family relationships change markedly with adolescents’ greater capacity for autonomy. Inequalities in health related to gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation tend to increase following puberty.55

Figure 2. Changing proximal social determinants of health across the life course.

During adolescence, social determinants from outside the family become greater, with major influences of peers, media, education, and the beginning of workplace influences. Community and structural determinants remain consistently influential, as shown by the background shading.

Young people growing up in contemporary societies differ in fundamental ways from those of past generations.84 Key among these differences are changes in the structure and function of families, greater engagement with education, and greater exposure to media influences. Each influence can function as an important enabling and protective system for health.

Family function, structure, and adolescent health

Families provide the primary structure within which children are born, grow, and develop, and from which adolescents transition to adult lives.85 Families are the main protective and enabling setting for children’s health, growth, and wellbeing. Economic development has generally brought changes in family structure, stability, and patterns of transition to the next generation of families. Parents have fewer children, allowing greater investment of family resources for each child.86 Smaller families mean parents can afford to invest more in education.73 This is important in the context where delayed transition into marriage and the formation of the next generation of families necessitates a longer period of parental investment. In the next 10 years, spending on education is projected to grow fastest in countries with the most rapid economic development and declines in fertility.87

Globally, countries outside of sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia have largely moved away from early marriage (appendix figure 2). In the majority of remaining countries with high rates of child marriage there is also a trend to later marriage. In north Africa and the Middle East, scarcity of employment and the financial resources for family formation have created a phase of “waithood”, in which young adults are unable to muster the resources needed for family formation.88 This has in turn been linked to a rise in civil unrest and conflict with potentially devastating effects on health and wellbeing.89

Families take an increasing variety of forms. In most countries, most adolescents still live at home with two parents. Cohabitation of parents rather than marriage is increasingly common, especially in high-income countries where there is also less stigma about single unmarried parents. Parental relationships have become less stable with parental separation now common in many countries. Together with declines in marriage, parental deaths from HIV in some countries, and parental migration for employment in others, there has been a global trend towards more single parent families.85 Living with only one or neither parent is now common in much of sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.90,91 In Asia, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, Central America, and South America, large numbers of adolescents now live with extended family members rather than parents.85

In high-income countries, many adolescents experience parental divorce, parental remarriage, or change in cohabitation during adolescence. In North America and Europe, around one-fifth of adolescents live in single parent households.85 By 2030 single parent families will make up to 40% of families in many countries.92 Increasing numbers of single parent families could increase adolescent exposure to poverty and lower uptake of education.92 Family instability is linked with poorer outcomes for adolescents including teenage parenthood, early marriage, and later life course trajectories that are themselves characterised by family instability.84,93

Puberty brings major shifts in parent–child relationships, with increases in both conflict and distance as adolescents seek greater independence and more autonomy.94 Such changes in parent–child interactional patterns are normal, but parental difficulty in managing these changes predicts adolescent health risks.95 Parenting capacities, such as those around monitoring and supervision of activities, are important for reducing health risks.84 Beyond this function, families are likely to have a central role in how adolescents learn to respond to new emotional experiences that emerge in and around puberty.96 Parents and peers are both important reference points for the adolescent in learning how to respond to more intense experiences of sadness, anxiety, and anger. The extent to which parents are able to express and respond to emotions is likely to have a major effect on this capacity in their adolescent children.96

Families also have the potential to harm. Family norms might promote gender inequity and attitudes towards violence with profound effects on identity development, reproductive health, mental health, and risks for violence.97 Female genital cutting or mutilation is prevalent across Africa and the Arab world, often perpetuated by families from cultural beliefs that it is necessary to prepare girls for marriage.98 Family violence and abuse have profound effects on adolescent mental health. Adolescents exposed to family violence are more likely to have educational failure and early school leaving, develop substance abuse, and engage in abusive relationships themselves.99

In the context of such secular changes in families and the greater complexity of adolescent social and emotional development, there are important questions about what strategies might best support families to nurture adolescents.92 There have been few systematic studies of the effects of family functioning on adolescent health. In response, we undertook a review of reviews to address the question of how family characteristics are associated with adolescent reproductive health, violence, and mental health (appendix table 2). The vast majority of identified studies focused on younger children with scant evidence around families of adolescents. Most of these studies focused on the effects of parent-adolescent communication. Limited but consistent evidence indicates that parent–adolescent communication (particularly mother–daughter communication) about sex led to delayed initiation of sex, and promoted contraception use.100 Better parent–adolescent communication is also linked to adolescent self-esteem and self-worth,101 better social functioning,102 and fewer mental health problems.101 For LGBT youth, supportive parent– adolescent relationships are protective against risky behaviours.103 Limited but consistent evidence indicates that lower family socioeconomic status and parental education are associated with higher rates of teenage pregnancy.104 Adolescents living in non-intact families or families with problems have higher odds of suicide, substance abuse, depression, and eating problems.102

Given that families and parents remain the most important figures in the lives of most adolescents, the paucity of rigorous research into family influences on adolescent health and wellbeing is a striking knowledge gap.

Education and adolescent health

Education is a powerful determinant of adolescent health and human capital and driver of socioeconomic progress.55,105 Those who are more educated live longer lives with less ill health. This is true in both rich and poor countries and is likely to have a causal relationship.105 The benefits are generally greater for women than men in high-income countries, particularly in terms of mortality, self-reported health, mental health, and obesity.106 Amongst adolescents in countries of low and middle income, higher education is associated with reduced teenage births and older age at marriage.107 Education also has intergenerational effects; improved education for women could account for up to half of the global improvement in child mortality since 1970.108

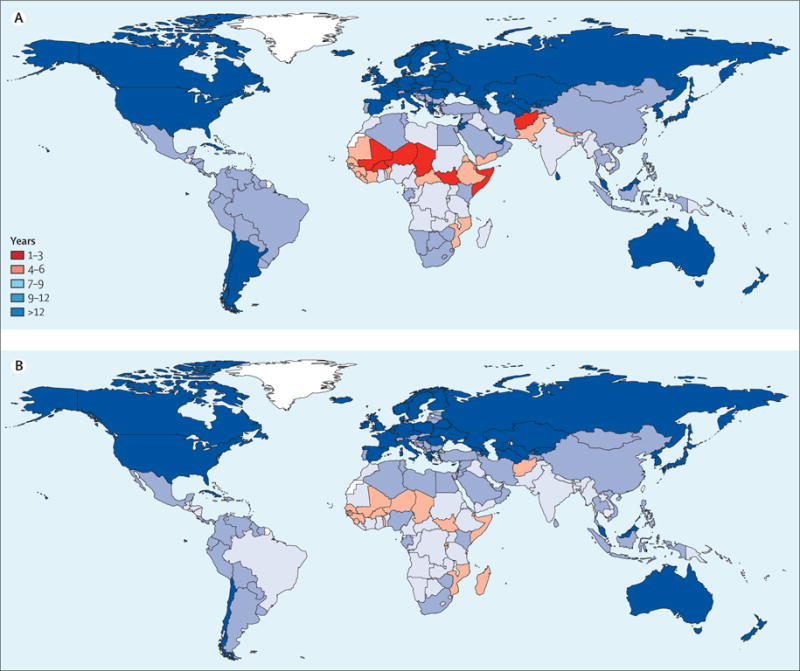

To date, research on the value of education for health in countries of low and middle income has largely focused on early childhood and primary education.109 There has been little study of the benefits of secondary education for adolescents in countries of low and middle income, despite a dramatic global expansion in the length of education in the past 30 years. Figure 3 shows estimates of global educational attainment. Young women aged 15–24 years had a global average of 9·5 years of education in 2015 in comparison to 9·9 years in young men. Primary education only (mean of 7 years of education or less) was the norm for young men in 22% of countries and for young women in 26% of countries. A minimum of lower secondary education (8–10 years of education) was the norm in 34% of countries for young men and in 18% for young women. Upper secondary or beyond (11 or more years of education) was the norm in 44% of countries for young men and 56% for young women.110

Figure 3. Educational participation of 15–24 year olds for 188 countries.

(A) Mean years of education attained in women and girls aged 15–24 years in 2013. (B) Mean years of education attained in men and boys aged 15–24 years in 2013. Data from Global Health Data Exchange.69

The health benefits of secondary education for adolescents have been poorly studied in countries of low and middle income. In high-income countries there might be a threshold effect at the upper secondary level for self-reported health, mental health, and alcohol use, with little additional benefit from tertiary education.106 With primary education now widespread in countries of low and middle income, expansion of participation in secondary education offers an achievable strategy for improving health across the life course and into the next generation.106 In countries that already have high secondary education participation, facilitating schools to more explicitly promote health has the potential for leverage above and beyond the health benefits of educational participation alone.

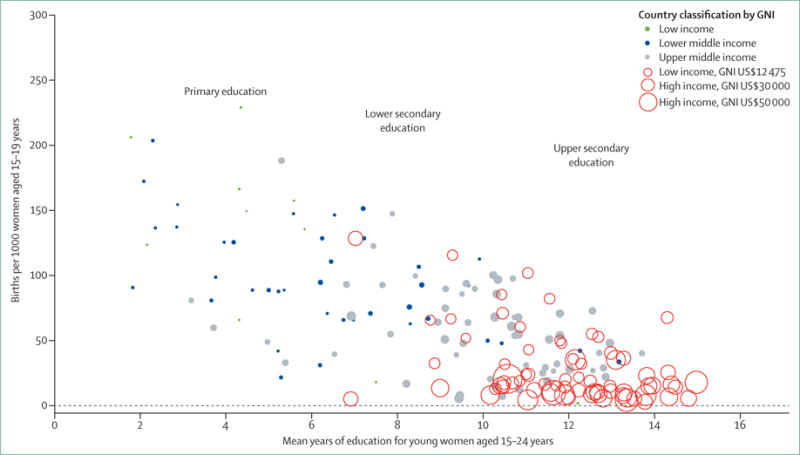

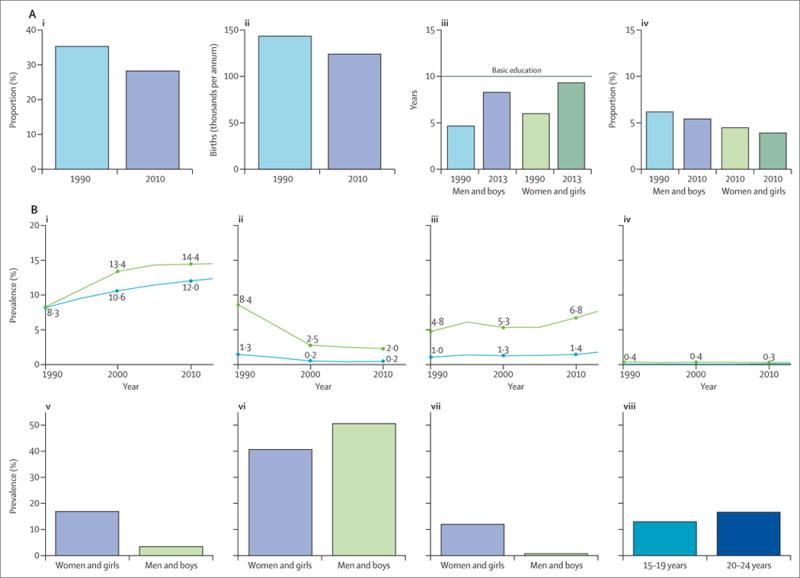

We used recent data on average years of education for young men and young women aged 15–24 years for 187 countries from 1970 to 2015 and data from UN sources on adolescent fertility and mortality to examine the links between participation in secondary education and health (figure 4, appendix figures 3, 4, 5). Strong associations were found between the average years of education for 15–24-year-old women and girls and adolescent birth rates, all-cause and injury mortality among 15–19-year-old boys and girls, and maternal mortality amongst 15–24 year olds. Each additional year of education for girls was associated with 9·2 fewer births per 1000 girls per year. Countries in which young women generally attended lower secondary education (ie, received 8–10 years of education) had approximately 48 fewer births per 1000 girls per year than those with primary education alone. Those where most young women obtained upper secondary education (11 years or more) had an average of 68 fewer births per 1000 girls per year (figure 4). We then modelled the effect of trends in education on adolescent fertility from 1990 to 2012. Both economic development and increases in education were independently associated with total birth rate. Each additional year of education again decreased adolescent birth rates annually by 8·5 births per 1000 girls per year across all countries when adjusted for growth in national wealth. Accelerating investments to 12 years of education for girls would bring very marked reductions in total adolescent birth rates (appendix figure 5).

Figure 4. Country-level association between adolescent birth rates and years of education in 2010–12.

Each additional year of education is associated with an average of nine fewer births per 1000 adolescent girls per country. GNI=gross national income.

Higher average levels of education were associated with lower total adolescent mortality in both sexes, injury mortality (boys only), and maternal mortality, after adjustment for national wealth. Each additional year of education was associated with 13 fewer deaths per 100 000 15–19-year-old boys per year after adjustment for national wealth with a similar but smaller association for girls. For young women 15–24 years, pregnancy-related maternal mortality, while at relatively low levels in most countries providing data, was strongly associated with education. Each additional year of education for young women was associated with 0·4 fewer maternal deaths per 100 000 girls per year in 15–24 year olds after accounting for national wealth. Findings were similar when analyses were rerun using education data for 25–34 year olds instead of 15–24 year olds.

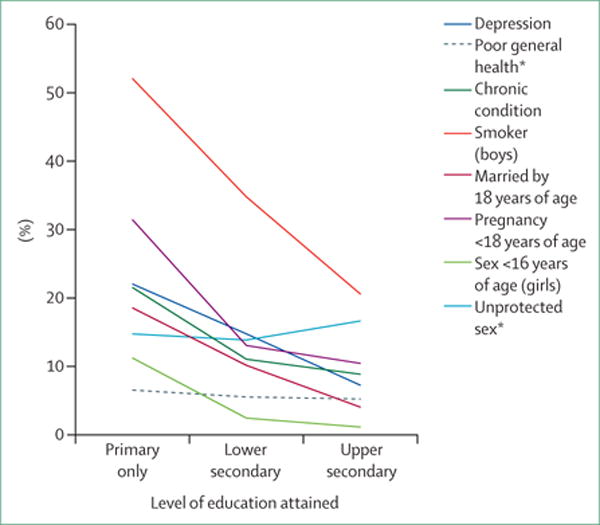

We next identified six cohorts from countries of low and middle income in which it was possible to examine the associations of secondary education participation with health (figure 5, appendix figure 6). In each country, we estimated the association between participation in lower or upper secondary school compared with attending primary school on a range of health outcomes, using structural marginal models and controlling for a range of potential confounders. In each cohort, higher secondary completion was associated with health independent of wealth, age, sex, parental education, and cognitive ability. In one cohort in the Philippines, adolescents with later secondary education had a greater than 50% lower rate of various health problems than those with primary education alone (figure 5). The benefits were most consistent for mental health, alcohol use, and sexual health. Despite being based on observational data, the consistency across cohorts supports secondary education as a major resource for adolescent health and wellbeing extending across the life course.

Figure 5. Association between health at 18 years of age and level of education in the Cebu cohort study, Philippines.

Data from Global Health Data Exchange.69 *These associations were not significant.

Characteristics of health-promoting schools

We reviewed evidence from existing systematic reviews on the school characteristics predictive of health for young people across all country types (appendix text box 1). We addressed the effects of schools’ environments on violence, substance use, and sexual health risks. We focused on these outcomes as each is common, almost entirely initiated during adolescence, and has substantial consequences for health and wellbeing.

The traditional way in which schools address these behaviours is through health education delivered in classrooms, for which there is established evidence of small to moderate effects although implementation is often patchy and effects not sustained.111 The ways that schools operate more widely have great effects on health and wellbeing.112 For this reason actions that address the school environment are more likely to be effective. A school’s ethos extends to the physical and social environment, management and organisation, teaching, discipline, pastoral care, school health services, wholeschool health promotion, and extra-curricular activities.

We found clear evidence that a positive school ethos is associated with health (table 1). One medium quality review113 found that in schools where attainment and attendance are better than predicted based on student sociodemographic factors, rates of adolescent smoking, alcohol use, and drug use and, in one study, violence were lower. Another medium quality review114 found that student connection to school and to teachers was associated with reduced drug use, alcohol use, and smoking. A low quality review115 suggested there were lower rates of violence in schools with positive student–teacher relationships, with students who were aware of rules and accepted these were fair. Another low quality review116 that specifically focused on outcomes for LGBT students found that schools with more supportive policies had lower rates of victimisation. The evidence around school characteristics affecting sexual health were insufficient to draw firm conclusions. Expansion of secondary education in countries with high adolescent fertility and sexual health risks suggests that this is an important question for research and evaluation.

Table 1.

Summary of school effects on adolescent health from a systematic review of reviews of observational studies

| Sexual health | Violence | Tobacco | Alcohol | Drugs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value added education | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | Rigorous evidence for some benefit | Rigorous evidence for some benefit | Rigorous evidence for some benefit |

| Student connection to school or teachers | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit |

| School rules or policies | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | No or inconsistent evidence | No or inconsistent evidence | No or inconsistent evidence |

| Physical environment | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit |

| Student norms | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit | Limited evidence for some benefit | No or inconsistent evidence |

| Student socio-demographics | No or inconsistent evidence | Limited evidence for some benefit | No or inconsistent evidence | No or inconsistent evidence | No or inconsistent evidence |

The health and wellbeing benefits of expansion of secondary education accrue through multiple mechanisms, including healthier behaviours, greater cognitive capacity, and longer productive adult lives for the current generation, better health and lower mortality among their children, and overall greater productivity in the future workforce.73 However, many forces operate to exclude or divert adolescents from secondary education. Prominent among these are the costs of education and the costs to families of the loss of adolescent labour, especially in rural areas. In many countries of low and middle income, poor adolescents are less likely to attend secondary school.117 Early marriage accounts for higher dropout rates in girls in many low-income and middle-income countries. Most interventions to increase access to and retention in education in these settings have been in younger adolescents, largely in primary schools. Scholarships, school fee reductions, cash transfers conditional on remaining in school, decrease in grade repetition, school proximity, and education in the mother tongue are cost-effective actions.118,119 Free school uniforms and abolishing school fees are among the most cost-effective interventions, while school meals and financial support to parent–teacher associations are less cost-effective. Building schools close to students is cost-effective, as one school can serve children for many years.118 Addressing gender disparities in access and targeting more resources to the poorest regions as well as to disadvantaged students (notably children affected by armed conflict, children whose home language is not used at school, and children with disabilities) are critical to closing equity gaps.120 There is also a need for greater non-formal or flexible learning strategies for children without access to mainstream education (eg, child labourers and married adolescents who have left school).121 Health interventions including comprehensive sexuality education and providing access to modern contraception are likely to have major benefits in reducing school dropout in settings where early pregnancy is common.122,123

Academic achievement on standardised tests (eg, the Programme for International Student Assessment)124 has commonly been used as an index of school quality. On these measures schools in low-income and middle-income countries lag far behind Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. Yet in higher income settings, narrowly focused international metrics of student attainment have been criticised as the main driver of school performance and educational focus. There is a risk that schools will de-emphasise their essential role in social development, marginalise health actions and health-related education,125 and potentially undermine mental health. Particularly for low achieving students, a narrow focus on academic achievement diminishes self-esteem126 and increases student disengagement, a predisposing factor for academic failure, poor mental health, substance use, violence, and sexual risks.127 Potentially harmful directions in current educational policy that overly focus on academic performance could be mitigated by including health and wellbeing indices alongside educational attainment metrics in school performance management systems.128 Ultimately, promotion of education and health are synergistic goals, both of which are essential for wellbeing and generating human capital; health and wellbeing interventions boost educational attainment while education boosts health and wellbeing.129

Transition into the workforce

The workplace has historically been a major social influence on health from mid-adolescence. A reduction in the number of 10–24 year olds working has followed increased retention in secondary and tertiary education.73 Yet in countries of low and middle income, many adolescents younger than 15 years of age still work. Of these, a substantial minority work in hazardous occupations with poor lifelong earning prospects.130 Over 47·5 million young people aged 15 to 17 years are estimated to work in jobs that expose them to environmental hazards, excessive hours, or physical, psychological, or sexual abuse.130 Young women are more likely than young men to have difficulty finding safe and stable work in non-hazardous occupations.130

Longer education and reduced exposure to occupational health hazards have positive health effects, but new risks are emerging related to unemployment. Transitioning from education into the workforce has become more diffi cult in many countries.73 Transitions are now slower with a poorer selection of jobs. Many young adults are in unstable, informal employment, or unable to get jobs.131 Global youth unemployment is estimated at 12·5%, with youth almost three times more likely than adults to be unemployed.131 Those who leave school to be unemployed or inactive (not in employment, education, or training [NEET]) make up around 13% of the youth population across the OECD but up to 30% in rapidly developing countries of low and middle income such as South Africa and India, and close to 50% in some OECD countries such as Spain and Greece.132 Those who are NEET at the end of schooling are more likely to have lower earnings, greater unemployment, and employment instability through adult life.133 Poor health and diffi cult transitions into the workplace go hand in hand; those who are NEET have high rates of mental health problems, suicide risk, and substance abuse.134,135

Peers, media, youth culture, and marketing

The emergence of strong peer relationships is a central feature of early adolescence, with significant implications for health and wellbeing.55 Modern adolescence differs markedly from a pre-industrial context in both the number and diversity of peers.136 Later marriage and parenthood and prolongation of education have acted to expand the role of peers within the lives of adolescents. Social media is further expanding the role of peers and youth cultures in the lives of adolescents across all countries.137

Peers can have strong positive or negative influences on adolescent health.138 Peer connection, peer modelling, and awareness of peer norms can be protective against violence, substance use, and sexual risks.139 Peers can also increase risks, with peer participation in risk behaviours likely to increase smoking initiation and persistence, alcohol initiation and use, sexual risks, and violence.140,141 Other peer characteristics, such as sexual partner communication and negotiation skills, influence sexual and HIV risks.139,142

Social media use further extends the influence of peers on health.143 Online spaces have changed adolescent developmental tasks such as relationship and identity building which were previously mainly negotiated in face-to-face communications with peers.136 For many adolescents, identity formation incorporates local influences with new elements derived from global culture, particularly youth cultures.144 There is continued debate over whether exposure to digital media, including a greatly expanded social network, might adversely affect adolescent social, emotional, and cognitive develop ment.145 To date, the development of the new media has been so rapid that research efforts to understand their effects have failed to keep pace with their growing influence.

There is, however, little doubt that rapid changes in the media environment have changed patterns of marketing to adolescents and young adults. Again, the speed of change has been such that research on the consequences has lagged far behind marketing practices. To assess current knowledge of the effects of marketing on adolescent health, we conducted a review of reviews of research around the effects of media on sexual and reproductive health, substance use, and obesity, using diverse strategies (table 2). Although most research is on traditional media, we included reviews on digital media where available (appendix text box 2).

Table 2.

Strength of evidence for effects of media and marketing on adolescent health risks

| Tobacco use | Alcohol use | Obesity | Sexual risks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Distal exposures

| ||||

| Point of sale advertising (POS) | Strong | Moderate | Strong (food choice) | NA |

| Imagery in films/movies | Strong | Strong | Moderate (amount of food) | NA |

| Imagery in television | Moderate | Moderate | Strong (food choice/amount) Strong (food purchase request) |

Moderate |

| Music videos/MTV | No studies | Moderate | No studies | Low |

| Cartoon media characters | No studies | No studies | Moderate (food choice & purchase request) | No studies |

| Magazines | Moderate | Moderate | No studies | No studies |

| Outdoor advertising | NA | Moderate | No studies | No studies |

| Imagery on Internet | Low | NA | No studies | Low |

| Online social networking sites | Low | NA | No studies | NA |

| Concessional stands at events | No studies | Moderate | No studies | No studies |

| Radio advertising | No studies | Low | No studies | No studies |

| Composite (multiple media) | No studies | Moderate | No studies | No studies |

| Advertising (media unspecified) | Moderate | No studies | Strong (food choice/amount) | No studies |

|

Intermediate exposures | ||||

| Ownership of promotional items | Strong | Moderate | No studies | No studies |

| Approval of advertising | Moderate | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Receptivity to marketing | Moderate | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Media use | No studies | NA | Strong | No studies |

| Favourite star smoking | Moderate | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Favourite ad/brand recall | Moderate | No studies | No studies | No studies |

| Attending a promotional event | Low | No studies | No studies | No studies |

Strong=strong evidence level based on consistency, temporality, dose-response in cohort studies or experimental study/meta-analysis. Moderate=moderate evidence level based on consistency and temporality from cohort studies. Low=low evidence level based on cross-sectional surveys. NA=limited/insufficient evidence.

The evidence of the influence of marketing through traditional media on adolescent tobacco use is compelling. Point of sale advertising and smoking imagery in films had the clearest evidence. There is moderate evidence around the importance of smoking imagery in other settings including television and magazines, particularly among girls. A range of factors linked to marketing and media use were also predictors of tobacco initiation with the strongest evidence for ownership of a promotional item.

There was moderately strong evidence for marketing affecting alcohol initiation, consumption, maintenance, and heavy drinking. Depiction of drinking in movies, television, music and rap videos, advertisements in magazines, point of sale displays, and advertising on radio and concessional stands at promotional events all had effects. In general, the effects of multiple media exposures on alcohol consumption were greater than for specific individual media.

Links between marketing and adolescent obesity are less well defined, in part due to the greater time lag between exposure and outcome. Yet links between marketing and intermediate outcomes that are strongly predictive of later obesity are clear. Food imagery in television, imagery in films, and point of sale advertising had moderate evidence for outcomes including food choice and amount. Overall media use (TV, computer, and video games) showed the strongest evidence of association with overweight and obesity although a major mediator is likely to be sedentary behaviour and diminished physical activity.

There have been fewer studies of media effects on sexual health risks. Moderate evidence indicates an association between frequent viewing of sexual content on TV with early sexual intercourse and increasing levels of non-coital sexual activity. There is weaker evidence around associations between exposure to pornography and early sexual debut, higher number of lifetime partners and higher-risk sexual activity such as engaging in unprotected anal intercourse.

Most studies on the effects of marketing have been in high-income countries where there is solid evidence of their effects on adolescent health risks. Few studies have extended either to countries of low and middle income or to new media. Yet industries which have until recently largely used traditional marketing media are now using digital media to promote unsolicited content and advertise their products. This marketing extends beyond national borders and is more tailored to individuals. Given that marketing is likely to become even more powerful and increasingly cross national borders, policy responses at both national and global levels are necessary. The WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, now ratified by 180 countries, provides perhaps the best indication of what might be needed. Even strategies such as these can be ineffective in the face of international trade pacts that protect the interests of global corporations ahead of a country’s capacity to implement regulatory controls.146 There is need to both extend current global health frameworks to other unhealthy commodities and access to essential health goods and ensure that these are included in international trade and investment agreements.147

Legal frameworks

Laws affect adolescents and their future health by governing both access to resources for health and protection from hazards. Some specifically address health (eg, access to health care including effective contraception); others address health risks (eg, consumption of alcohol, access to tobacco); and others address social determinants of health (eg, age of marriage, protection from hazardous work). These laws reflect ever-evolving, complex, and often contradictory perspectives on young people that have been informed by historical, social, economic, religious, and other cultural forces. Inadequate and inconsistent legal frameworks can powerfully affect the health, rights, and potential of adolescents and young adults.

Complex articulation of legal principles of adolescent capacity