Abstract

Recurrence is a serious problem in patients with bladder cancer. The hypothesis for recurrence was that the proliferation of drug-resistant cells was reported, and this study focused on drug resistance due to drug efflux. Previous studies have identified FOXM1 as the key gene for recurrence. We found that FOXM1 inhibition decreased drug efflux activity and increased sensitivity to Doxorubicin. Therefore, we examined whether the expression of ABC transporter gene related to drug efflux is regulated by FOXM1. As a result, ABCG2, one of the genes involved in drug efflux, has been identified as a new target for FOXM1. We also demonstrated direct transcriptional regulation of ABCG2 by FOXM1 using ChIP assay. Consequently, in the presence of the drug, FOXM1 is proposed to directly activate ABCG2 to increase the drug efflux activation and drug resistance, thereby involving chemoresistance of bladder cancer cells. Therefore, we suggest that FOXM1 and ABCG2 may be useful targets and important parameters in the treatment of bladder cancer.

Keywords: ABCG2, Bladder cancer, Cancer recurrence, Drug resistance, FOXM1

INTRODUCTION

Bladder cancer (BC) is the sixth common cancer in men worldwide (1), with more than 70% of patients diagnosed with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) (2). Frequent recurrence in NMIBC patients is a serious problem and NMIBC patients are stratified into three risk groups (low, intermediate, high) (3). NMIBC patients considered high risk for recurrence are usually treated with transurethral resection, bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy and chemotherapy [e.g. doxorubicin (DOX) and mitomycin C] (4, 5). However, NMIBC recurs in more than 50% of patients within 2 years and 10–30% of recurrence patients progress to muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) (6). Therefore, new strategies for treatment and diagnosis of recurrence are needed to address frequent recurrence.

The mechanism of recurrence is not yet clear, but the current hypothesis suggests that small populations of cells reside in cancerous tissue, survive chemotherapy and form tumors again through proliferation (7). This hypothesis is partially similar to cancer stem cell theory in terms of drug resistance (8). Anticancer drug resistance mechanisms are reported to be caused by an increase in the DNA repair, anti-apoptosis and efflux (9). We have previously shown that the expression of ABCG2 increased when BC cell lines overexpressing E2F1, EZH2 or SUZ12 were treated with mitomycin C (10). E2F1 is known to regulate the expression of FOXM1 and ABCG2 (11, 12), respectively, but the correlation between FOXM1 and ABCG2 has not been known until now.

Forkhead box M1 (FOXM1) is a key factor in progression of the G2/M cell cycle in normal cells (13). Recent studies have demonstrated FOXM1 as abnormally overexpressed in many types of cancers (14, 15) and is known to associated with proliferation, DNA repair, apoptosis (16), metastasis, recurrence and resistance to various anticancer drugs (11, 15). FOXM1 expression has been reported to have unfavorable clinical response to chemotherapy for patients with breast cancer (17). Interestingly, recent studies have reported that increased expression of FOXM1 provokes cancer cells to transform into cancer stem cells (18).

Drug efflux is one of the causes of drug resistance (19). In the ABC transporter family, ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2 have been reported as major genes related to drug resistance (20). In particular, ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 2 (ABCG2) is a major cancer stem cell marker (21). In general, ABCG2 is expressed in certain tissues such as the placenta, mammary gland and testis (22), but exhibits abnormal expression in various cancer, cancer stem cells and drug-resistant cells (23). Recent studies have shown that ABCG2 can protect cancer stem cells by efflux of anticancer drugs such as DOX, mitoxantrone and topotecan (24). Abnormal expression of ABCG2 has also been reported to be associated with recurrence of a variety of cancers such as colorectal, lung and prostate cancer (25, 26). Despite these findings, the transcriptional regulation of ABCG2 has not yet been fully understood.

In this study, we focused on the mechanism of drug resistance by drug efflux pathways to identify the mechanism of recurrence. Therefore, we investigated the correlation between FOXM1, a recurrent factor identified in previous studies, and the ABCG2 gene associated with drug efflux. We found that FOXM1 binds directly to the ABCG2 promoter and regulates ABCG2 transcription, thereby revealing new regulatory pathways that influence drug efflux. Based on these findings, we propose a treatment strategy for BC recurrence by inhibiting FOXM1, which could reduce the drug resistance.

RESULTS

Inhibition of FOXM1 expression reduces DOX resistance and drug efflux

Acquisition of resistance to anticancer agents has been reported to be related to recurrence (9). In our previous study, we suggested FOXM1 as a major gene for recurrence and investigated whether this gene correlates with drug excretion (14).

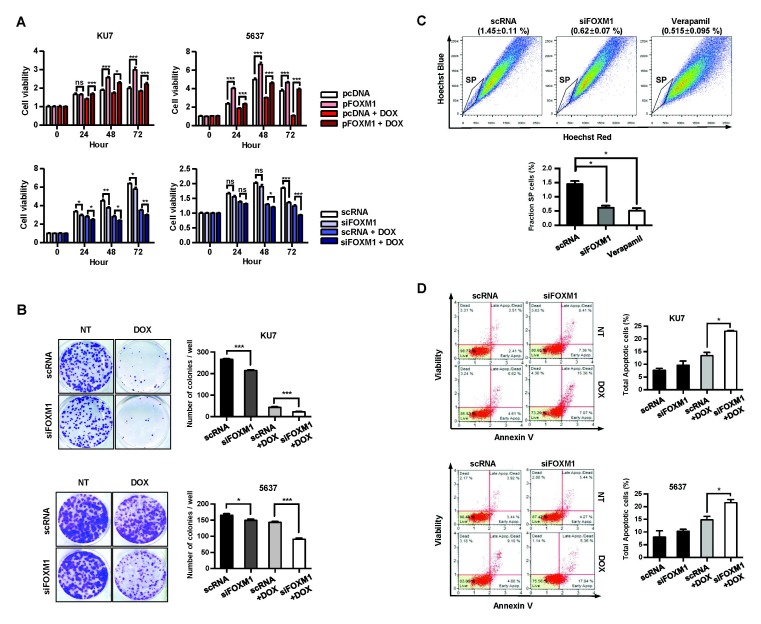

First, we investigated the effects of FOXM1 on drug sensitivity and efflux (Fig. 1A) and clonogenic assays (Fig. 1B) were used to measure cell viability and proliferative activity. Overexpression or knockdown of FOXM1 showed a significant increase and decrease in cell viability in both the untreated and 0.5 μM DOX-treated conditions (Fig. 1A). Similar results were also obtained in clonogenic assays (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that FOXM1 plays an important role in resistance to DOX in BC cells.

Fig. 1.

Decreased FOXM1 reduces drug efflux and cell viability in BC cells. The cell viability was measured by MTT (A) and clonogenic assays (B). Cells were transfected with siRNA (scRNA and siFOXM1) or overexpression vector (pcDNA and pFOXM1) for 24 h and then exposed to 0.5 μM DOX for indicated time (C). Drug efflux activity was measured using a SP assay. KU7 cells were transfected with siRNA for 24 h. Cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 dye (1 mg/ml) in the presence or absence of the drug efflux inhibitor verapamil (100 μg/ml) and analyzed by FACS. (D) Effect of FOXM1 on apoptosis in BC cells. Cells were transfected with scRNA or siFOXM1 and then exposed to 0.5 μM DOX for 24 h. The apoptosis rate was measured using a Muse Annexin V kit.

We then used a side population (SP) assay to measure drug efflux capacity to verify whether FOXM1 can affect drug efflux. KU7 cells were transiently transfected with scRNA and siFOXM1 to investigate efflux activity. The effluent efficiency of the Hoechst 33342 dye is shown in the lower left quadrant of the FACS profile in Fig. 1C, labeled SP. The distribution of SP cells in the control cells was 1.45%, but it was reduced to 0.52% in the drug efflux inhibitor verapamil-treated cells. Similarly, the distribution of SP cells in siFOXM1 treated cells was reduced to 0.62%, half the level of the control, indicating decreased drug efflux activity due to FOXM1 deficiency (Fig. 1C).

We also examined the effect of FOXM1 levels on the rate of apoptosis induced by DOX-treatment. There was no difference in apoptotic rate between scRNA-transfected KU7 cells and siFOXM1-transfected KU7 cells when the drug was not treated. In contrast, treatment with 0.5 μM DOX resulted in an apoptosis rate of 13.4% in cells transfected with scRNA, but increased significantly in siFOXM1-transfected cells by 23% (Fig. 1D). This increase in apotosis by DOX treatment was also observed in 5637 cells (Fig. 1D).

FOXM1 regulates the expression of ABCG2 in BC cells

Drug efflux is known to be regulated by ABC transporter family (20). Previous our studies have shown that the ABCG2 is increased by anticancer drug treatment in BC cells (10). Therefore, we confirmed whether the decrease of drug efflux activity by inhibition of FOXM1 is due to the regulation of ABC transporter expression by FOXM1. To investigate whether FOXM1 regulates the ABC transporter family, KU7 cells were treated with scRNA or siFOXM1 to compare the transcription amount of the ABC transporter family according to the expression of FOXM1 (Fig. S1A). When FOXM1 was depleted, the level of ABCG2 transcription among the ABC transporter family was significantly reduced (Fig. S1A). Thus, we examined the mRNA and protein levels of FOXM1 and ABCG2 in BC cell lines and found that FOXM1 and ABCG2 were highly expressed in KU7 cells and poorly expressed in 5637 cells (Fig. S1B and S1C). We also examined cell viability for DOX in BC cell lines and selected KU7 cell lines with relatively high viability and 5637 with a low survival rate in subsequent experiments (Fig. S1D).

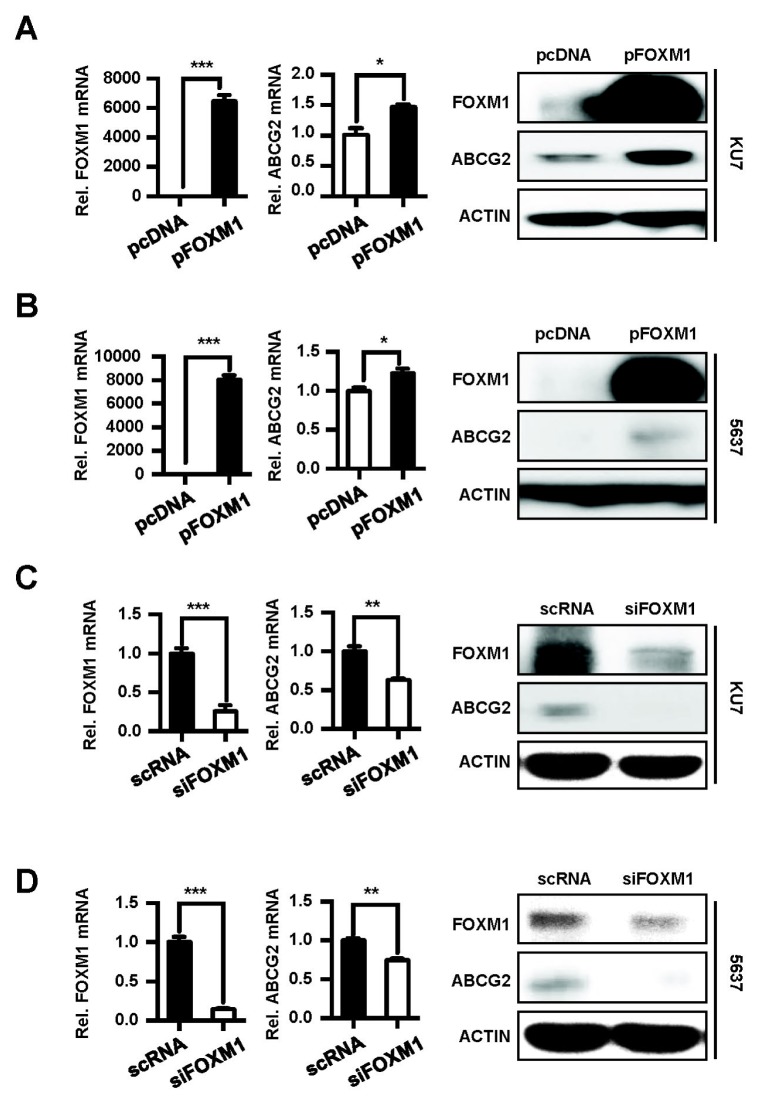

At first, the effect of FOXM1 overexpression on mRNA and protein levels of ABCG2 was examined using KU7 and 5637 cells (Fig. 2A and 2B). We also investigated the effect of depleted FOXM1 on ABCG2 levels (Fig. 2C and 2D). The ABCG2 mRNA and protein were significantly increased by overexpression of FOXM1 (Fig. 2A and 2B), whereas the knockdown of FOXM1 significantly decreased the ABCG2 expression compared to the control (Fig. 2C and 2D). These results indicate that ABCG2 expression in these two cell lines are regulated by FOXM1.

Fig. 2.

FOXM1 regulates ABCG2 expression in BC cells. pcDNA and pFOXM1 were transfected into KU7 (A) and 5637 cells (B). scRNA and siFOXM1 were transfected into KU7 (C) and 5637 cells (D). After 24 h, mRNA and protein levels were analyzed using qRT-PCR (left panel) and Western blotting (right panel).

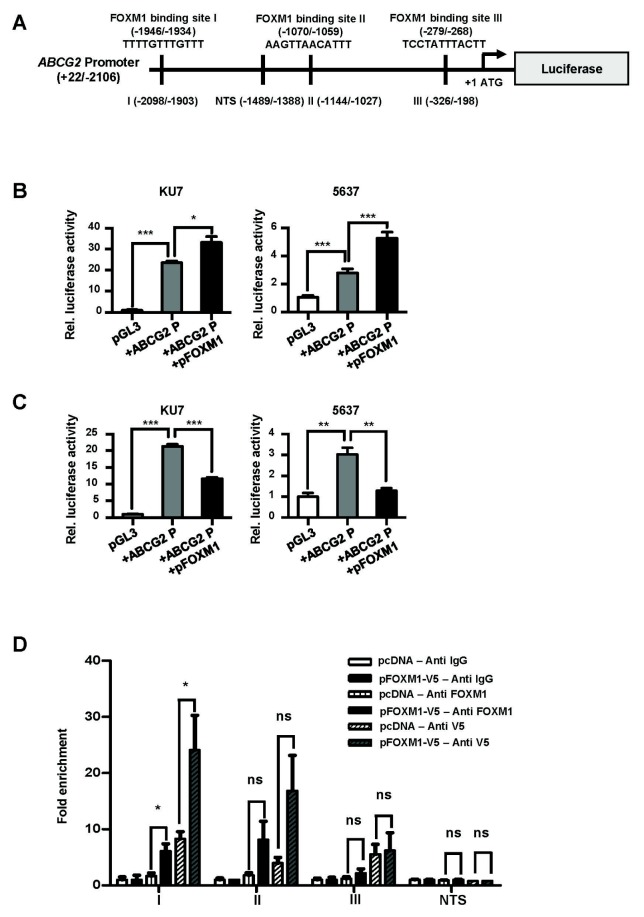

FOXM1 binds directly to the ABCG2 promoter to regulate expression

We investigated whether FOXM1 binds to the ABCG2 promoter and regulates transcription. We found three putative FOXM1 binding sites (I, II and III) in the ABCG2 promoter (Fig. 3A). To examine whether FOXM1 regulates transcription of ABCG2, we used a promoter vector to drive a luciferase reporter gene in transient co-transfections with an expression vector in BC cells (Fig. 3B). The transcriptional activity of the ABCG2 promoter was significantly increased in FOXM1-induced cells (Fig. 3B). Conversely, cells were co-transfected with a promoter vector and siRNA to determine whether reduced FOXM1 affects the transcription of the ABCG2 promoter (Fig. 3C). Similarly, ABCG2 transcriptional activity was significantly decreased in FOXM1-depleted cells, indicating that FOXM1 affects the expression of ABCG2 (Fig. 3C). To determine whether the effect shown above is due to direct binding of the FOXM1 to the ABCG2 promoter, a ChIP assay was performed (Fig. 3D). As a result, when the locus I region was used, the PCR fragment was significantly amplified in pFOXM1-transfected cells (Fig. 3D). When the locus II, III and non-target site (NTS) loci were used, there were no differences between the two different transfected cells (Fig. 3D). These results show that FOXM1 can directly bind to the locus I region of the ABCG2 promoter to regulate ABCG2 transcription.

Fig. 3.

FOXM1 binds directly to the ABCG2 promoter to regulate transcription. (A) Schematic diagram of ABCG2 promoter vector (ABCG2P). The ABCG2 promoter (−2106/+22) was inserted into the pGL3 basic vector and the three putative FOXM1 binding sites (−1946/−1934, −1070/−1059 and −279/−268) are represented. The black bars on the promoter region indicate the positions of the primers (I: −2098/−1903, II: −1144/−1027, III: −326/−198 and non-target site (NTS): −1489/−1388) for qChIP amplification. (B) BC cells were transformed with pGL3-basic, ABCG2P or ABCG2P + pFOXM1, respectively. (C) BC cells were transformed with pGL3-basic, ABCG2P or ABCG2P + siFOXM1, respectively. transcriptional activity was measured by luciferase assay. (D) ChIP assay in the ABCG2 promoter. 5637 cells were transfected with pcDNA or pFOXM1 + V5 tag vector, Immunoprecipitation was performed using the rabbit IgG (control), FOXM1 and V5 antibody. The chromatin fragments were amplified using primers for the three putative FOXM1 binding sites (loci I, II, III) and NTS primers shown in (A).

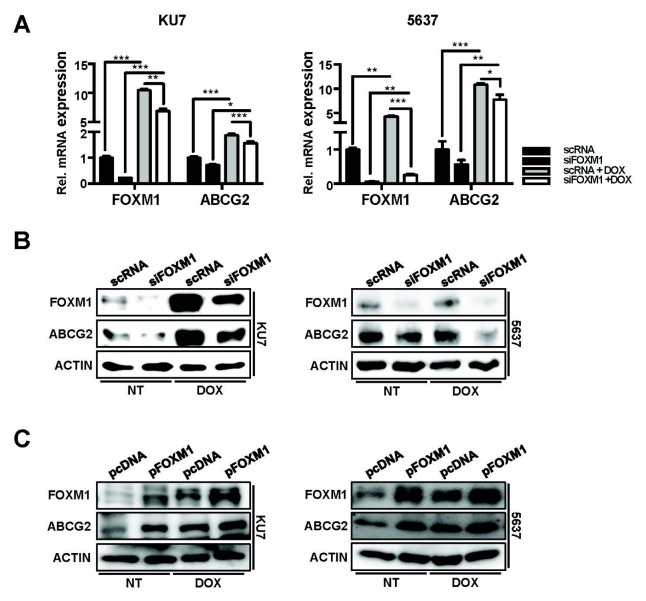

To investigate whether ABCG2 expression in DOX-treated cells is regulated by FOXM1, cells transfected with overexpressed vector (pFOXM1) or siRNA for FOXM1 (siFOXM1) were treated with DOX and the expression of ABCG2 were compared. mRNA (Fig. 4A) and protein levels (Fig. 4B and 4C) of FOXM1 and ABCG2 were significantly accelerated by DOX treatment. These ABCG2 and FOXM1 expressions by DOX treatment were additionally induced in pFOXM1 cells, then significantly reduced in siFOXM1 transfected cells. As a result, expression of FOXM1 and ABCG2 is induced in DOX-treated conditions, indicating that FOXM1 regulates the expression of ABCG2.

Fig. 4.

FOXM1 reduction was shown to decrease ABCG2 expression under DOX exposure. Two bladder cancer cells were transfected with siRNA (scRNA and siFOXM1) or overexpression vector (pcDNA and pFOXM1). After 24 h, transfected cells were exposed to 0.5 μM DOX for 24 h. mRNA (A) and protein (B, C) levels of FOXM1 and ABCG2 were analyzed by qPCR and western blotting methods.

DISCUSSION

About 70% of BC patients diagnosed with BC have NMIBC and the survival rate is better than for MIBC (27). Nonetheless, about 50% of NMIBC patients have frequent recurrences and the treatment is difficult and costly (6). Therefore, if biomarkers are found that can predict the recurrence of BC to prevent these problems, accurate diagnosis and effective treatment will be possible.

Drug resistance mechanisms have been reported to be due to increased efflux activity of anticancer agents associated with the ABC transporter family (14, 15). There have been many studies on the drug efflux process of ABCG2, but studies on transcriptional regulation have yet to be revealed except for factors such as SP1, c-Myc and Hif-1α (28). Therefore, we investigated the relationship between FOXM1 and the drug efflux pathway which inhibits chemotherapy and recurrence. In this study, it was confirmed that FOXM1 directly binds to the ABCG2 promoter to regulate the transcription of ABCG2, and drug resistance is caused by the drug efflux activity of FOXM1–ABCG2. These results suggest that reducing the expression of FOXM1 in NMIBC patients may provide effective results in chemotherapy. Furthermore, since SP analysis is used to measure the population of cancer stem cells, it may be suggested that the abnormal expression of FOXM1 is also linked to the increase of cancer stem cells (29).

Recent studies have reported that ABCG2 is associated with drug release and cancer recurrence in breast cancer (30), but analysis of the gene expression profiles of the patients used in this study showed no correlation between FOXM1 and ABCG2 expression (data not shown). These results suggest that the expression of ABCG2, a marker of cancer stem cells, is not highly induced in cancer tissues before anticancer therapy, but when treated with an anticancer agent, FOXM1 is induced and leads to an increase in ABCG2. In other words, considering that cancer stem cells survive treatment with a chemotherapeutic agent and increase in number, it is thought that the function of cancer stem cells may be related to the drug release of FOXM1–ABCG2.

In summary, in drug-treated cells, FOXM1 directly regulates the transcription of ABCG2 and acts on drug efflux and drug resistance. These results may give important implications for the hypothesis of the relationship between FOXM1 and cancer stem cells (29). In addition, FOXM1 could affect cancer cell proliferation and survival by treatment with anticancer drugs. Based on these results, we propose that FOXM1 modulates drug resistance and can be used as a predictor of BC recurrence and target gene therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and chemotherapeutic agent

BC cell lines KU7, EJ, T24 and 5637 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells from ATCC were certificated by results of short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling, cytochrome C oxidase I and mycoplasma contamination assays.

T24, EJ and KU7 cells were grown in DMEM (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). 5637 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. DOX (Sigma) was dissolved in sterile water.

Plasmids, small interfering RNA and transfection

pcDNA6-V5-His was purchased from Invitrogen. pFOXM1 was provided by Dr. Ju-Seog Lee (MD Anderson Cancer Center). To generate the pFOXM1-V5 tag, the coding sequence (CDS) region was amplified by PCR from pFOXM1 DNA. pGL3 basic plasmid was purchased from Promega. To generate the pGL3 basic-ABCG2 promoter, its region from −2105 to +22 was cloned by PCR from human genomic DNA using the indicated primer sets (Table S1). Scrambled RNA (scRNA) was purchased from Shanghai GenePharma (Shanghai GenePharma). siFOXM1 was synthesized from ST Pharm Oligo center (ST Pharm). Transfection was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Jetprime).

qRT-PCR

cDNA synthesis and qPCR analysis used a PrimeScript RT reagent kit and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II Tli RNaseH Plus (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA of FOXM1, ABCG2 and β-actin was detected using the indicated primer sets (Table S2). The experiment was performed using the CFXTM Optics Module (Bio-Rad), and the data analyzed using CFX ManagerTM (Bio-Rad).

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (10). The following antibodies were used: anti-FOXM1 (Bethyl), anti-ABCG2 (Abcam) and anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling).

Luciferase assay

A luciferase assay was performed as described previously (10). The plasmid DNA used was pGL3-basic, pGL3-basic-ABCG2 promoter, pcDNA6, pFOXM1 and pRL Renilla luciferase control reporter vector (Promega).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

A ChIP assay was performed as described previously (31). The following antibodies were used: anti-V5, anti-FOXM1 and normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (Cats. A190-120A, A301-532A and A120-101P, Bethyl Lab). The indicated qChIP primer sets were used to amplify the precipitated DNA fragments (Table S2).

Flow cytometry apoptosis assay

Cells were incubated with MuseTM Annexin V & Dead Cell Reagent (Millipore) for 20 min at RT in the dark. Apoptotic and necrotic cell analysis was performed using a MuseTM Annexin V & Dead Cell Kit (Millipore) and MuseTM Cell Analyzer (Millipore).

Cell viability assay

A methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (Sigma) assay was performed as described previously (10). Cell reproductive ability was detected by clonogenic assay. siRNA transfected cells were seeded at 5 × 102 cells/well in a six-well plate and incubated for 24 h. The cells cultured were treated with 0.5 μM DOX for 24 h. After 10 days, formed colonies were stained with crystal violet (Sigma) and counted using a Carl Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Side population assay

Cells were treated with 5 μg/ml of Hoechst 33342 (1 mg/ml, Sigma) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C. After staining, cells were incubated again for 45 min for the efflux period. Verapamil (100 μg/ml; Sigma) was treated as a negative control for side population. Cells were resuspended in cold PBS with 2 μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) to exclude non-viable cells. A BD FACSAriaTM II (BD Biosciences) equipped with 360 nm UV and 488 nm argon lasers was used to read the fluorescence of Hoechst 33342 and PI, respectively. 424/44 BP and 675 LP filters, in combination with a 640 nm long pass dichroic mirror, were used for detection of Hoechst blue and red, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test for multiple comparisons as indicated. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. Differences were considered significant at the values of P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**) and P < 0.001 (***). Statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1B 03935385) and a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI16C1866). SIK was partially supported by grants of the National Council of Science & Technology (NST) grant by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. CRC-16-01-KRICT).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Youssef RF, Lotan Y. Predictors of outcome of non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive bladder cancer. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:369–381. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden AP, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol. 2006;49:466–465. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. discussion 475–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall MC, Chang SS, Dalbagni G, et al. Guideline for the management of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 update. J Urol. 2007;178:2314–2330. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woldu SL, Bagrodia A, Lotan Y. Guideline of guidelines: non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2017;119:371–380. doi: 10.1111/bju.13760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rhijn BW, Burger M, Lotan Y, et al. Recurrence and progression of disease in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: from epidemiology to treatment strategy. Eur Urol. 2009;56:430–442. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y, Zhu G, Wu K, et al. FGF2-mediated reciprocal tumor cell-endothelial cell interplay contributes to the growth of chemoresistant cells: a potential mechanism for superficial bladder cancer recurrence. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:4313–4321. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang JC. Cancer stem cells: Role in tumor growth, recurrence, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:S20–25. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salehan MR, Morse HR. DNA damage repair and tolerance: a role in chemotherapeutic drug resistance. Br J Biomed Sci. 2013;70:31–40. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2013.11669927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu J, Yoon NA, Seong H, et al. Resveratrol Induces Glioma Cell Apoptosis through Activation of Tristetraprolin. Mol Cells. 2015;38:991–997. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2015.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Millour J, de Olano N, Horimoto Y, et al. ATM and p53 regulate FOXM1 expression via E2F in breast cancer epirubicin treatment and resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:1046–1058. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenfeldt MT, Bell LA, Long JS, et al. E2F1 drives chemotherapeutic drug resistance via ABCG2. Oncogene. 2014;33:4164–4172. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa RH. FoxM1 dances with mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:108–110. doi: 10.1038/ncb0205-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SK, Roh YG, Park K, et al. Expression signature defined by FOXM1-CCNB1 activation predicts disease recurrence in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3233–3243. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park YY, Jung SY, Jennings NB, et al. FOXM1 mediates Dox resistance in breast cancer by enhancing DNA repair. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1843–1853. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nestal de Moraes G, Bella L, Zona S, Burton MJ, Lam EW. Insights into a Critical Role of the FOXO3a-FOXM1 Axis in DNA Damage Response and Genotoxic Drug Resistance. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:164–177. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666141122211549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khongkow P, Gomes AR, Gong C, et al. Paclitaxel targets FOXM1 to regulate KIF20A in mitotic catastrophe and breast cancer paclitaxel resistance. Oncogene. 2016;35:990–1002. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemenetzidis E, Elena-Costea D, Parkinson EK, Waseem A, Wan H, Teh MT. Induction of human epithelial stem/progenitor expansion by FOXM1. Cancer Res. 2010;70:9515–9526. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zahreddine H, Borden KL. Mechanisms and insights into drug resistance in cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:28. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher JI, Haber M, Henderson MJ, Norris MD. ABC transporters in cancer: more than just drug efflux pumps. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:147–156. doi: 10.1038/nrc2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding XW, Wu JH, Jiang CP. ABCG2: a potential marker of stem cells and novel target in stem cell and cancer therapy. Life Sci. 2010;86:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mo W, Zhang JT. Human ABCG2: structure, function, and its role in multidrug resistance. Int J Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;3:1–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.An Y, Ongkeko WM. ABCG2: the key to chemoresistance in cancer stem cells? Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:1529–1542. doi: 10.1517/17425250903228834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robey RW, To KK, Polgar O, et al. ABCG2: a perspective. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzel E, Karatas OF, Duz MB, Solak M, Ittmann M, Ozen M. Differential expression of stem cell markers and ABCG2 in recurrent prostate cancer. Prostate. 2014;74:1498–1505. doi: 10.1002/pros.22867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu J, Li J, Yue X, et al. Expression of the cancer stem cell markers ABCG2 and OCT-4 in right-sided colon cancer predicts recurrence and poor outcomes. Oncotarget. 2017;8:28463–28470. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa C, Pereira S, Lima L, et al. Abnormal Protein Glycosylation and Activated PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway: Role in Bladder Cancer Prognosis and Targeted Therapeutics. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0141253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Natarajan K, Xie Y, Baer MR, Ross DD. Role of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in cancer drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1084–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teh MT. FOXM1 coming of age: time for translation into clinical benefits? Front Oncol. 2012;2:146. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damiani D, Tiribelli M, Geromin A, et al. ABCG2 overexpression in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Impact on stem cell transplantation outcome. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:784–789. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim DH, Roh YG, Lee HH, et al. The E2F1 oncogene transcriptionally regulates NELL2 in cancer cells. DNA Cell Biol. 2013;32:517–523. doi: 10.1089/dna.2013.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.