ABSTRACT

The amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide is central to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Insights into Aβ-interacting proteins are critical for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying Aβ-mediated toxicity. We recently undertook an in-depth in vitro interrogation of the Aβ1–42 interactome using human frontal lobes as the biological source material and taking advantage of advances in mass spectrometry performance characteristics. These analyses uncovered the small cyclic neuropeptide somatostatin (SST) to be the most selectively enriched binder to oligomeric Aβ1–42. Subsequent validation experiments revealed that SST interferes with Aβ fibrillization and promotes the formation of Aβ assemblies characterized by a 50–60 kDa SDS-resistant core. The distributions of SST and Aβ overlap in the brain and SST has been linked to AD by several additional observations. This perspective summarizes this body of literature and draws attention to the fact that SST is one of several neuropeptide hormones that acquire amyloid properties before their synaptic release. The latter places the interaction between SST and Aβ among an increasing number of observations that attest to the ability of amyloidogenic proteins to influence each other. A model is presented which attempts to reconcile existing data on the involvement of SST in the AD etiology.

KEYWORDS: Alzheimer's disease, Aβ, somatostatin, senile plaques, amyloids

Introduction

The Aβ peptide, an endoproteolytic fragment of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) [1], as well as factors controlling its biogenesis and clearance are understood to play critical roles in the etiology of AD. Whereas fibrillar forms of Aβ present in senile plaques were initially considered the pathogenic species of the peptide, it has become increasingly evident that soluble, oligomeric and pre-fibrillar forms of Aβ are toxic entities in the disease [2,3]. The identification of binders of these soluble Aβ conformers is critical for ongoing efforts to devise rational therapeutic approaches that block Aβ-mediated toxicity.

To date, several Aβ-binding proteins have been identified, spanning extracellular proteins (e.g., clusterin) [4], transmembrane receptors (reviewed in [5]), as well as intracellular binders [6] (e.g., ABAD [7]). Despite these advances, the application of an unbiased discovery approach to generate an inventory of human brain proteins that interact with oligomeric forms of Aβ was lacking. To fill this gap, we recently conducted a deep Aβ interactome analysis using biotinylated monomeric (mAβ) or oligomeric (oAβ) Aβ1–42 peptides as baits and human frontal lobe extract as the biological source [8]. Aside from confirming several previous interactions and uncovering many more novel candidate Aβ binders, this analysis revealed a surprising interaction between oAβ and somatostatin-14 (SST14). Follow-on work revealed that the presence of SST14 perturbs Aβ aggregation and promotes the formation of Aβ assemblies with a 50–60 kDa SDS-resistant core [8]. These findings are intriguing in light of observations by others that revealed SST14 to be able to acquire amyloid properties in vitro [9]. In fact, this neuropeptide hormone has been shown to be stored as amyloid in dense core secretory granules prior to its regulated synaptic release [10]. Although the existence of crosstalk between functional and disease-related amyloidogenic proteins has been suggested before [11,12], to date this scenario has not been adequately considered in the context of AD. This perspective will shine a spotlight on the possibility that SST might influence the pathobiology of AD on account of its selective interaction with Aβ. We will summarize the main findings from our aforementioned study, discuss SST biology as it relates to AD, and present a model of the potential involvement of SST, and other functional amyloids, in AD.

Main

1. SST14 selectively interacts with oligomeric Aβ and Influences Aβ aggregation

SST14 is a cyclic 14-amino acid peptide that is derived from an inactive preprosomatostatin (PPSST) precursor protein by a series of endoproteolytic trimming steps that occur during its passage through the regulated secretory pathway (RSP) (Fig. 1A). Its discovery as a selective binder of C-terminally tethered oAβ1–42 was unexpected and is owed to its unique sequence and the mass accuracy of leading-edge orbitrap mass spectrometers. Whereas confident protein identifications conventionally require the matching of at least two mass spectra to in silico predicted peptides of a given protein, SST only came to the fore as candidate binder of oAβ1–42 when we waived this requirement [8]. At that time, we noticed a high-quality spectrum that was confidently matched to a five-amino acid sequence ‘NFFWK’ which, despite its brevity, could only have originated from human SST14 or its related CST17 paralog (Fig. 1B, C).

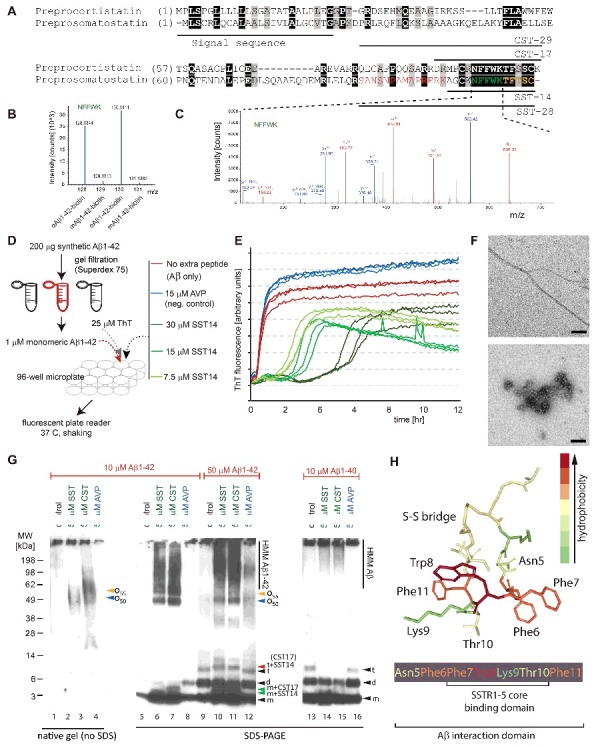

Figure 1.

Discovery and validation of SST-Aβ interaction. (A) Sequence alignment of preprocortistatin and preprosomatostatin. The signal sequence and the boundaries of the bioactive cortistatin and somatostatin peptides are indicated by horizontal bars. Identical residues are highlighted by black background shading, and peptide sequences observed by mass spectrometry are shown in colored fonts. (B) Expanded view of MS3 spectrum derived from ‘NFFWK’ parent spectrum (shown to the right) in interactome study based on oAβ1–42-biotin baits and mAβ1–42-biotin negative controls. In this view, the relative intensities of tandem mass tag signature ions reflect the relative abundances of the ‘NFFWK’ peptide in side-by-side generated affinity purification eluate fractions, indicating preferential binding of SST to pre-aggregated oAβ1–42. (C) Example tandem MS spectrum supporting the identification of the peptide with amino acid sequence ‘NFFWK’. Fragment masses attributed to B- and Y- ion series are shown in red and blue colors, respectively. (D) Workflow of ThT-based aggregation assay. (E) SST14 delays Aβ1–42 aggregation in ThT fluorescence assay in a SST14 concentration dependent manner. (F) Negative stain electron microscopy of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–42–SST14 complexes. Top panel: Aβ1–42 was fibrillized in PBS at a concentration of 50 μM. Individual Aβ1–42 amyloid fibrils and small clusters were visualized. Bottom panel: Incubation of equimolar concentrations (50 μM) of Aβ1–42 and SST14 under identical conditions resulted in oligomeric assemblies only. No amyloid fibrils were observed. Magnification bars = 100 nm. (G) Immunoblot analyses with an antibody directed against an N-terminal Aβ epitope (6E10) reveal that CST17 (or SST14) co-assemble with Aβ1–42 into oligomers of 50–60 kDa that withstand boiling (lanes 2 and 3) but partially disintegrate in the presence of SDS. Note bands of 5–6 kDa, consistent with the existence of SDS-resistant heterodimeric complexes of mAβ1–42 and SST14 (or CST17), and the well-defined oligomeric bands of 50 and 55 kDa (lanes 6 and 7) that were observed in samples derived from the co-incubation of SST14 (or CST17) with Aβ1–42, but not Aβ1–40 (lanes 6, 7, 14, 15). Note also that signals interpreted to represent trimeric Aβ1–42, but not dimeric Aβ1–42, can be seen to migrate slower in the presence of SST14 (or CST17) but not in the presence of the negative control peptide AVP (compare lanes 9 and 12 with lanes 10 and 11). Finally, intensity levels of homodimeric Aβ1–42 bands are reduced in the presence of SST14 (or CST17) (compare lanes 13 and 16 with lanes 14 and 15). Black arrowhead labeled with ‘m’, ‘d’, and ‘t’ designate bands interpreted to consist of monomeric, dimeric and trimeric Aβ1–42. Green and red arrowheads were used to label bands interpreted to represent SDS-stable heteromeric building blocks consisting of SST14 (or CST17) bound to monomeric and trimeric Aβ1–42, respectively. (H) Model of SST14, showing the position of its disulfide bridge between cysteine 3 and 14, and the binding domains required for docking to its SST receptors or Aβ. Elements from this image were adapted from,[8] licensed under CC BY 4.0.

In follow on work, the interaction was validated by several orthogonal approaches. Amongst them, Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence-based analyses of Aβ1–42 aggregation kinetics (Fig. 1D) revealed that the presence of SST14 in the reaction mix consistently extended the lag phase and decreased the signal amplitude of the ThT fluorescence trace (Fig. 1E). Notably, a direct correlation was observed between the duration of the lag phase extension and the concentration of SST14 (or CST17) in the reaction mix. This effect was not observed when these peptides were replaced by one of several other cyclic neuropeptide hormones (e.g., AVP). Whereas preparations of Aβ1–42 gave rise to the expected fibrillar structures in negative stain electron micrographs, the co-incubation of Aβ1–42 and SST14 led exclusively to oligomeric assemblies (Fig. 1F, bottom panel).

When ThT assay fractions, which had been incubated in the presence of SST14 or CST17 for 18 hours, were analyzed by Western blotting without prior boiling in SDS, Aβ-reactive bands (detected with the 6E10 antibody) of 50–60 kDa were apparent (Fig. 1G, lanes 2, 3). Upon boiling in SDS, these 50–60 kDa signals became even more pronounced, as did lower mass bands, consistent with the partial release of building blocks (Fig. 1G, lanes 6, 7). In some instances, these lower mass bands migrated at apparent molecular weights expected for heterodimers of Aβ1–42 and SST14 (or CST17) (Fig. 1G, lanes 6, 7). When the Aβ1–42 concentration was further increased, bands at levels expected for Aβ1–42 trimers plus SST14 (or CST17) were observed (Fig. 1G, lanes 10, 11). None of these SST14- (or CST17-) dependent bands were observed when Aβ1–42 was replaced with Aβ1–40 in the assay mix (Fig. 1G, lanes 15, 16).

Interestingly, all available data suggest that the Aβ-SST interaction does not occur between monomers but requires at least one of the binding partners to be present in a pre-aggregated oligomeric (or pre-fibrillar) form. Results from epitope mapping experiments revealed that the tryptophan in position 8, located in a hydrophobic ‘belt’ within SST14, is required for the interaction. When this SST residue was replaced with alanine, proline, histidine, or tyrosine, the lag phase extension phenotype and reduction in total ThT fluorescence observed in the presence of wild-type SST were abolished. Whereas a synthetic SST14-derived peptide comprising amino acids 6–10 failed to influence Aβ aggregation kinetics, the presence of a peptide consisting of residues 5–11 of SST14 was sufficient to mimic wild-type SST14 in these experiments (Fig. 1H).

2. SST Biology overlaps with AD pathology

Synthetic SST14 spontaneously self-associates into supra-molecular nanofibrils under physiological pH and salt conditions [9]. These in vitro fibrils exhibit green/yellow birefringence upon Congo-red dye binding. Attenuated total reflection-FTIR spectroscopy data of SST fibrils were consistent with them acquiring a β-hairpin backbone conformation and cross-β symmetry [9], features shared with the fibril structure of Aβ1–42.13

The dense nature of amyloids offers the cell an elegant solution to a storage challenge. Not only are these structures efficient from a space-management perspective but the absence of water in such amyloid assemblies [14] protects the peptide from degradation and limits undesirable interactions with other molecules. However, this solution also bears a risk, namely the possibility of functional amyloids encountering other peptides, which harbor a propensity to convert to pathogenic amyloid if permissive conditions are met.

The fact that we observed a need for either SST or Aβ to be pre-aggregated for a direct interaction to occur raises the intriguing possibility that their interaction may emerge as a rare example of in vivo cross-seeding between functional and pathologic amyloidogenic peptides.

Although our current data are restricted to in vitro paradigms, there is reason to anticipate that our data may bear significance for AD. In fact, several reports corroborate the notion that spatial proximity of Aβ and SST14 exist in the human brain, particularly in areas relevant to AD. Because both APP and PPSST undergo endoproteolytic cleavages during their passage through the secretory pathway that give rise to Aβ and SST, respectively, a first opportunity for these peptides to interact may already exist on route to their cellular release [6]. With regard to their tissue distribution within the brain, primary areas where SST14 and Aβ overlap include the frontal and parietal cortices, hippocampus, and potentially the hypothalamus and amygdala [15,16]. Relative to somatostatin gene products, mRNA levels of cortistatin may be lower in several subareas of the brain[17] and its mature CST17 peptide may target a strongly overlapping, yet distinct, set of receptors [18].

Levels of SST have been observed to decline gradually throughout adult life. In fact, somatostatin mRNA was amongst a few dozen gene products whose levels in the frontal cortex correlated inversely with age [19]. Interestingly, the natural decline in SST levels is further accentuated in AD [16], and most likely correlates with an approximately 50% reduction in the number of somatostatinergic neurons observed in various brain areas [20,21]. In fact, one of the earliest biochemical changes documented in the cerebral cortex of AD patients was an accelerated reduction in SST immunoreactivity [22].

The first indication that SST may have a more intimate role in the AD pathogenesis emerged in histochemical studies, which detected processes of somatostatinergic neurons in immediate proximity to neuritic plaques in the cingulate, frontal and temporal cortices [23], as well as in the amygdala and hippocampus [24]. The central conclusion from these reports has withstood the test of time and was corroborated by a recent study, which revealed that morphologically well-conserved somatostatinergic cells colocalized to a high percentage with Aβ in the olfactory (43%) and piriform cortex (65%) [20]. Notably, the same study reported that virtually all cell debris of somatostatinergic neurons co-localized with senile plaques.

With regard to the tau pathobiology of AD, early data suggested that somatostatinergic neurons not only exhibited pronounced morphological changes but also were prone to exhibit neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). However, more recent work exploring the vulnerability of different types of neurons to this second pathological AD hallmark found only weak evidence for an association of neurofibrillary tangles with somatostatinergic neurons [20].

There is robust evidence that SST can regulate the catabolism of Aβ through its interaction with a family of SST receptors. More specifically, it has been shown that binding of the SST ligand triggers an intracellular event cascade that modulates the expression of neprilysin, a membrane metallo-endopeptidase involved in Aβ degradation [25].

Lastly, two independent genome-wide association studies, using Finnish and Chinese patient cohorts, identified the SST gene as a genomic region with the potential to modulate the risk of acquiring AD [26,27].

3. Evidence for interactions between other amyloidogenic peptides

In considering the possible significance of the SST-Aβ interaction in the AD context, it is useful to also take into account prior reports of interactions between amyloidogenic peptides with an influence on amyloid aggregation kinetics. There is no shortage of reports documenting the widespread existence of this phenomenon (reviewed in ref [28]). For example, amyloid formation was promoted in vitro when Aβ was mixed with α-synuclein [29]. A closer look revealed that Aβ and α-synuclein formed hybrid, pore-like oligomers, which could embed in the cell membrane, resulting in abnormal ion conductance [30]. Importantly, this phenomenon can also manifest in vivo, as was elegantly shown when animal models of Aβ amyloidosis were inoculated with PrPSc prions [31]. Several parameters need to be met for a co-incubation of two amyloidogenic peptides to promote amyloid formation. It has been proposed that critical amongst these is a need for conditions that are conducive to increasing the amyloidogenic potential of at least one of the co-incubated peptides, and to work with peptides that exhibit compatible structural and post-translational features, as well as share sequence characteristics [28]. Close examination of SST and Aβ sequences reveals that the ‘NFFWK’ core Aβ binding epitope within SST bears resemblance to the ‘LVFFA’ segment within Aβ (residues 17–21). The latter is considered a critical determinant for Aβ fibrillogenesis and has served as a template for derivatizing effective β-sheet breaker peptides [32]. It is likely that cross-seeding of the kind observed for pathogenic amyloidogenic peptides extends to functional amyloids. Indeed, the first examples for this phenomenon were recently reported: Exposure of aged rats to bacteria expressing the amyloidogenic protein curli resulted in enhanced brain α-synuclein aggregation [12]. Moreover, co-expression of the functional amyloid protein Orb2 (an ortholog to human CPEB) with the pathogenic Huntingtin protein revealed that these two proteins co-aggregate [11]. This example is particularly pertinent, as it provides a precedent for an interaction between a functional and pathogenic amyloid that might modulate memory consolidation.

4. Model of possible involvement of functional amyloids in AD

Based on the various SST-related observations made in the aforementioned studies, a model has been proposed whereby declining levels of SST, observed during aging, may be responsible for reduced clearance of Aβ, leading to its net accumulation and, eventually, Aβ-induced cell death in AD [33]. In this context, monomeric SST is expected to act in a protective manner by inducing the release of Aβ degrading enzymes. Our data indicate that monomeric SST may also be therapeutic due to its ability to interfere with Aβ fibrillization. The model is incomplete, however, because it provides no explanation for why, among all types of neurons, somatostatinergic neurons were repeatedly observed at the ‘epicenter’ of the AD pathobiology, as characterized by their proximity to senile plaques. This spatial overlap would be paradoxical given that the SST-releasing neurons would be particularly well-suited to induce the release of neprilysin. Elevated neprilysin levels, in turn, on the basis of their Aβ cleavage capacity, would be expected to reduce the risk to have an amyloid plaque forming. It is possible that a dichotomy of outcomes exist following exposure to monomeric versus aggregated SST, with monomeric SST being protective and aggregated SST potentially being harmful. Such a scenario would account for the aforementioned paradox.

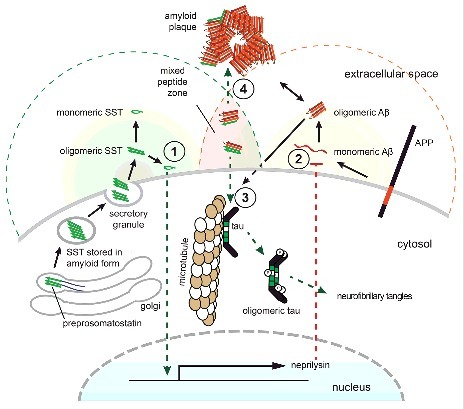

In light of the existence of highly condensed amyloid stores of SST [10] and the new SST-Aβ binding data [8], the following revised model is emerging (Fig. 2): As levels of SST transcripts decline naturally with aging, the Aβ clearance mechanisms in nearby neurons may become less effective, leading to a net increase in Aβ. Near the synaptic SST-release sites of the remaining SST-positive neurons, micro-zones must exist that contain high concentrations of residual SST amyloids. Although the post-release steps are not fully understood [34], there is sufficient evidence that the disassembly of amyloids proceeds in time-scales of minutes to hours [35], which may lead to sustained elevated concentrations of their building blocks nearby. Even higher concentrations of SST amyloid may spill out of neuritic processes of dying somatostatinergic neurons. The co-occurrence of elevated levels of SST aggregates and elevated levels of Aβ may form an environment conducive to the formation of mixed oligomers, with some assemblies being toxic towards the SST-releasing neurons closest to their formation, and others being innocuous or even protective. Under certain conditions, the formation of toxic assemblies is favored and tau hyperphosphorylation is induced in nearby SST-positive cells, a phenomenon observed in primary hippocampal neurons [8]. As these cells, and others in the vicinity, are increasingly compromised, brain levels of SST would be expected to continue to decline and would not be available to interfere with Aβ aggregation [8], or to indirectly reduce Aβ levels by neprilysin induction [25]. Consequently, Aβ levels would increase relative to SST levels, and Aβ aggregation pathways could undergo a shift to fibrillar Aβ aggregation, thereby setting the stage for senile plaque formation. In order to truly determine the validity of this model, SST knockout mice could be crossed with an Aβ amyloidosis mouse model. The analysis of the distribution of Aβ plaques and other Aβ-related pathology in the intercrossed line could then indicate whether SST is protective or harmful in AD.

Figure 2.

Model of SST influencing AD. Concentrations of bioactive SST (indicated with green background shading) in the brain are highest in proximity to SST release sites or in areas where SST amyloid can spill out of damaged neuritic processes of somatostatinergic neurons. Where these sites overlap with regions of relatively high Aβ production (indicated by red background shading), micro-zones can exist that may comprise mixed aggregates of both peptides. (1) Monomeric SST induces a signaling cascade that leads to the transcriptional activation of neprilysin expression. (2) Neprilysin protein contributes to the destruction of Aβ. (3) The presence of mixed Aβ-SST conformers may initially favor the formation of oligomeric species that can induce tau hyperphosphorylation and induce cell death in nearby neurons (4) As the relative amounts of SST decline, these oligomeric species may become dominated by Aβ and may seed the formation of senile plaques. Note that while only one neuron is depicted here for simplicity, it is suggested that SST-dependent effects may not only manifest in an autocrine manner but may also act on nearby neurons in a paracrine mode.

Naturally, given their widespread and overlapping distributions, it is possible that SST (or CST) and Aβ also interact and influence each other in a healthy brain. Because the Aβ binding epitope within these cyclic neuropeptide hormones comprises the ‘FWKT’ motif required for their binding to human SST receptors (SSTRs) [36] (Fig. 1H), levels of extracellular Aβ may modulate the canonical intracellular signaling pathways emanating from SSTRs. This may lead to a range of outcomes, including changes to memory and cognition modulated by somatostatinergic neurons in hippocampal and cortical networks [37].

Conclusions

Despite a wealth of data that connected SST to the etiology of AD for over 30 years, it has only now emerged that direct interactions between SST and the Aβ peptide may exist in the brain. This perspective placed results, which documented that SST influences Aβ aggregation kinetics, in the context of prior pertinent knowledge. Collectively, these considerations paint a scenario whereby SST14 may not just be a passive bystander in AD. Urgently needed are studies that explore whether the presence or absence of SST affects Aβ amyloidosis in animal models. As so often, a first round of experiments may not yet be conclusive. For example, the presence of CST, which appears to interact similarly with Aβ, could compensate for the loss of SST and mask a critical contribution of these peptides to amyloid plaque pathogenesis. In the absence of conclusive data on the physiological significance of the Aβ-SST interaction, a second line of investigation could aim to characterize if the 50–60 kDa SDS-resistant core is merely composed of Aβ or represents a co-assembly product of the two peptides. The latter is suggested by the existence of heteromer bands we sometimes observed when co-incubating the two peptides. The ability to enrich such intermediate aggregation products may, in turn, facilitate the generation of antibodies, which could be used to evaluate if similar aggregation products exist in brain sections or cerebrospinal fluid samples obtained from AD cases and controls. Finally, there is no reason to assume that Aβ is the only pathogenic amyloid that can interact with functional amyloids. A rigorous evaluation of the scenario painted in this perspective is needed to determine its broader significance for neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

Ontario Centres of Excellence [grant number 25530], Government of Canada | Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [grant number 137651], Alberta Prion Research Institute (APRI) [grant number 201600028].

Abbreviations

- Aβ

amyloid beta peptide

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- ADDL

Aβ-derived diffusible ligand

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CST

cortistatin

- mAβ

monomeric Aβ

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangle

- oAβ

oligomeric Aβ

- PPSST

preprosomatostatin

- PrP

prion protein

- RSP

regulated secretory pathway

- α-SN

alpha-synuclein

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SST

somatostatin

- SST14

somatostatin–14

- SSTR

SST receptor

- TGN

trans-Golgi-network

- ThT

thioflavin T

Disclosure statement

HaW and GS hold a provisionary US patent on amyloid-beta binding polypeptides based in part on results of the original paper underlying this perspective article (filing number 62/451,309). The other authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge generous ongoing support by the Borden Rosiak family and the Arnold Irwin family.

References

- [1].Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, et al.. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature 1987;325(6106):733–6. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(2):101–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Abeta oligomer and Alzheimer's disease: an emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(3):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Narayan P, Orte A, Clarke RW, et al.. The extracellular chaperone clusterin sequesters oligomeric forms of the amyloid-beta(1–40) peptide. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(1):79–83. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jarosz-Griffiths HH, Noble E, Rushworth JV, et al.. Amyloid-beta Receptors: The Good, the Bad, and the Prion Protein. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(7):3174–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.702704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].LaFerla FM, Green KN, Oddo S. Intracellular amyloid-beta in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:11. doi: 10.1038/nrn2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lustbader JW, Cirilli M, Lin C, et al.. ABAD directly links Abeta to mitochondrial toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2004;304(5669):448–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1091230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wang H, Muiznieks LD, Ghosh P, et al.. Somatostatin binds to the human amyloid beta peptide and favors the formation of distinct oligomers. Elife. 2017;6:e28401. doi: 10.7554/eLife.28401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].van Grondelle W, Iglesias CL, Coll E, et al.. Spontaneous fibrillation of the native neuropeptide hormone Somatostatin-14. J Struct Biol. 2007;160(2):211–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maji SK, Perrin MH, Sawaya MR, et al.. Functional amyloids as natural storage of peptide hormones in pituitary secretory granules. Science. 2009;325(5938):328–32. doi: 10.1126/science.1173155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hervas R, Li L, Majumdar A, et al.. Molecular Basis of Orb2 Amyloidogenesis and Blockade of Memory Consolidation. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(1):e1002361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen SG, Stribinskis V, Rane MJ, et al.. Exposure to the Functional Bacterial Amyloid Protein Curli Enhances Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Aged Fischer 344 Rats and Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34477. doi: 10.1038/srep34477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gremer L, Scholzel D, Schenk C, et al.. Fibril structure of amyloid-ss(1–42) by cryoelectron microscopy. Science. 2017;358(6359):116–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, et al.. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-beta spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447(7143):453–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schettini G. Brain somatostatin: Receptor-coupled transducing mechanisms and role in cognitive functions. Pharmacol Res 1991;23(3):13. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(05)80080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gahete MD, Rubio A, Duran-Prado M, et al.. Expression of Somatostatin, cortistatin, and their receptors, as well as dopamine receptors, but not of neprilysin, are reduced in the temporal lobe of Alzheimer's disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20(2):465–75. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dalm VA, Van Hagen PM, de Krijger RR, et al.. Distribution pattern of somatostatin and cortistatin mRNA in human central and peripheral tissues. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;60(5):625–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cordoba-Chacon J, Gahete MD, Pozo-Salas AI, et al.. Cortistatin is not a somatostatin analogue but stimulates prolactin release and inhibits GH and ACTH in a gender-dependent fashion: potential role of ghrelin. Endocrinology. 2011;152(12):4800–12. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lu T, Pan Y, Kao SY, et al.. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature. 2004;429(6994):883–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Saiz-Sanchez D, De la Rosa-Prieto C, et al.. Interneurons, tau and amyloid-beta in the piriform cortex in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220(4):2011–25. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Saiz-Sanchez D, Ubeda-Banon I, de la Rosa-Prieto C, et al.. Somatostatin, tau, and beta-amyloid within the anterior olfactory nucleus in Alzheimer disease. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(2):347–50. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davies P, Katzman R, Terry RD. Reduced somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in cerebral cortex from cases of Alzheimer disease and Alzheimer senile dementa. Nature 1980;288(5788):279–80. doi: 10.1038/288279a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Morrison JH, Rogers J, Scherr S, et al.. Somatostatin immunoreactivity in neuritic plaques of Alzheimer's patients. Nature 1985;314(6006):90–2. doi: 10.1038/314090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Armstrong DM, LeRoy S, Shields D, Terry RD. Somatostatin-like immunoreactivity within neuritic plaques. Brain Res 1985;338(1):71–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Saito T, Iwata N, Tsubuki S, et al.. Somatostatin regulates brain amyloid beta peptide Abeta42 through modulation of proteolytic degradation. Nat Med. 2005;11(4):434–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vepsalainen S, Helisalmi S, Koivisto AM, et al.. Somatostatin genetic variants modify the risk for Alzheimer's disease among Finnish patients. J Neurol. 2007;254(11):1504–08. doi: 10.1007/s00415-007-0539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Xue S, Jia L, Jia J. Association between somatostatin gene polymorphisms and sporadic Alzheimer's disease in Chinese population. Neurosci Lett. 2009;465(2):181–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sarell CJ, Stockley PG, Radford SE. Assessing the causes and consequences of co-polymerization in amyloid formation. Prion. 2013;7(5):359–68. doi: 10.4161/pri.26415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ono K, Takahashi R, Ikeda T, et al.. Cross-seeding effects of amyloid beta-protein and alpha-synuclein. J Neurochem. 2012;122(5):883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tsigelny IF, Crews L, Desplats P, et al.. Mechanisms of hybrid oligomer formation in the pathogenesis of combined Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. PLoS One. 2008;3(9):e3135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Morales R, Estrada LD, Diaz-Espinoza R, et al.. Molecular cross talk between misfolded proteins in animal models of Alzheimer's and prion diseases. J Neurosci. 2010;30(13):4528–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Soto C, Kindy MS, Baumann M, et al.. Inhibition of Alzheimer's amyloidosis by peptides that prevent beta-sheet conformation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1996;226(3):672–80. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hama E, Saido TC. Etiology of sporadic Alzheimer's disease: somatostatin, neprilysin, and amyloid beta peptide. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):498–500. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Anoop A, Ranganathan S, Das Dhaked B, et al.. Elucidating the role of disulfide bond on amyloid formation and fibril reversibility of somatostatin-14: relevance to its storage and secretion. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(24):16884–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.548354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Maji SK, Schubert D, Rivier C, et al.. Amyloid as a depot for the formulation of long-acting drugs. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(2):e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Pohl E, Heine A, Sheldrick GM, et al.. Structure of octreotide, a somatostatin analogue. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 1995;51(Pt 1):48–59. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Epelbaum J, Guillou JL, Gastambide F, et al.. Somatostatin, Alzheimer's disease and cognition: an old story coming of age?. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;89(2):153–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.