This randomized clinical trial tests the effectiveness of patient and clinician interventions to improve shared decision making and quality of care among an ethnically/racially diverse sample from behavioral health clinics.

Key Points

Question

How effective are the DECIDE (decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution) patient and clinician interventions for improving shared decision making and quality of care for ethnic/racial minorities?

Findings

In a randomized clinical trial of 312 dyads that included 74 behavioral health clinicians and 312 patients, the clinician intervention significantly improved shared decision making. Patients perceived higher quality of care when patients and clinicians received the recommended dosage of each intervention.

Meaning

The clinician intervention could improve shared decision making with minority populations, and the patient intervention could improve patient-reported quality of care by incorporating patient preferences in health care.

Abstract

Importance

Few randomized clinical trials have been conducted with ethnic/racial minorities to improve shared decision making (SDM) and quality of care.

Objective

To test the effectiveness of patient and clinician interventions to improve SDM and quality of care among an ethnically/racially diverse sample.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-level 2 × 2 randomized clinical trial included clinicians at level 2 and patients (nested within clinicians) at level 1 from 13 Massachusetts behavioral health clinics. Clinicians and patients were randomly selected at each site in a 1:1 ratio for each 2-person block. Clinicians were recruited starting September 1, 2013; patients, starting November 3, 2013. Final data were collected on September 30, 2016. Data were analyzed based on intention to treat.

Interventions

The clinician intervention consisted of a workshop and as many as 6 coaching telephone calls to promote communication and therapeutic alliance to improve SDM. The 3-session patient intervention sought to improve SDM and quality of care.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The SDM was assessed by a blinded coder based on clinical recordings, patient perception of SDM and quality of care, and clinician perception of SDM.

Results

Of 312 randomized patients, 212 (67.9%) were female and 100 (32.1%) were male; mean (SD) age was 44.0 (15.0) years. Of 74 randomized clinicians, 56 (75.7%) were female and 18 (4.3%) were male; mean (SD) age was 39.8 (12.5) years. Patient-clinician pairs were assigned to 1 of the following 4 design arms: patient and clinician in the control condition (n = 72), patient in intervention and clinician in the control condition (n = 68), patient in the control condition and clinician in intervention (n = 83), or patient and clinician in intervention (n = 89). All pairs underwent analysis. The clinician intervention significantly increased SDM as rated by blinded coders using the 12-item Observing Patient Involvement in Shared Decision Making instrument (b = 4.52; SE = 2.17; P = .04; Cohen d = 0.29) but not as assessed by clinician or patient. More clinician coaching sessions (dosage) were significantly associated with increased SDM as rated by blinded coders (b = 12.01; SE = 3.72; P = .001; Cohen d = 0.78). The patient intervention significantly increased patient-perceived quality of care (b = 2.27; SE = 1.16; P = .05; Cohen d = 0.19). There was a significant interaction between patient and clinician dosage (b = 7.40; SE = 3.56; P = .04; Cohen d = 0.62), with the greatest benefit when both obtained the recommended dosage.

Conclusions and Relevance

The clinician intervention could improve SDM with minority populations, and the patient intervention could augment patient-reported quality of care.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01947283

Introduction

According to the Institute of Medicine, clinicians could shrink the chasm of health care services quality by improving communication and seeking patients’ perspectives on shared power and responsibility. Shared decision making (SDM) is a form of patient-clinician communication where both parties bring expertise to the process and work in partnership to make a decision, thereby facilitating improved outcomes and quality of health care. However, few clinicians have the skills to encourage patient involvement or adjust to preferences. Randomized clinical trials of SDM have mostly targeted primary care and have included few ethnic/racial minorities. Minority patients are less likely than white patients to state concerns, seek information, or feel trust, thereby missing opportunities to improve outcomes.

Implementing SDM in behavioral health care poses challenges. Clinicians are trained as clinical experts; SDM represents a paradigmatic shift in acknowledging patients as experts of their illness experience and asking them to voice visit agendas. Clinician stereotyping, bias, and lack of skills to address power differentials are additional barriers. A collaborative relationship involves the patient’s problem formulation and joint solution development, which may lengthen visits. Differences exist in the meaning of SDM depending on patients’ race, ethnicity, or educational level. Ethnic/racial minorities may also hesitate to question their clinician.

A previous randomized clinical trial found that the patient-focused DECIDE intervention (decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution) (DECIDE-PA) improved patient activation and self-management in behavioral health care. Nonetheless, minority patients were more likely than white patients to express concern that becoming activated threatened their relationships with their clinicians. Activation is defined as the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and beliefs to enable thoughtful action and active participation in decisions.

Although the intervention was developed to incorporate cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic characteristics central to treatment participation and collaborative client-clinician relationships, the following clinician actions were observed that impeded communication and SDM: (1) lack of perspective taking to understand circumstances and perceptions, (2) erroneous dispositional inferences (ie, attributing negative patient behaviors to character traits), and (3) low receptivity to collaboration in decision making.

We tested the effectiveness of DECIDE-PA and DECIDE clinician (DECIDE-PC) interventions in improving SDM and patient-perceived quality of care among white, black, Latino, and Asian patients. We examined patient-perceived quality of communication and a working alliance as mediators. We also explored whether ethnic/racial or language matching moderated the intervention effect. We hypothesized that SDM would increase after both interventions, as would patient-perceived quality of care.

Methods

Trial Design

This study was a cross-level 2 × 2 randomized clinical trial with clinicians at level 2 and patients nested within clinicians at level 1 to assess the effectiveness of patient and clinician interventions. The study protocol is found in Supplement 1. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the 13 participating clinics, including Cambridge Health Alliance Windsor Street Health Center, Beth Israel Cognitive Neurology Unit, South Cove Community Health Center, Cambridge Health Alliance Central Street Care Center, Cambridge Health Alliance Macht Clinic, Edward M. Kennedy Community Health Center, Cambridge Health Alliance Outpatient Counseling and Treatment Consult-Liaisons, Beth Israel Outpatient Psychiatry, South End Community Health Center, Center for Behavioral Health/Family Services of Greater Boston, Massachusetts General Hospital–Chelsea Community Health Care, Massachusetts General Hospital Outpatient Psychiatry, and Massachusetts General Hospital Depression Clinic. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Eligible clinicians were from participating clinics with at least 4 current patients. Eligible patients were initially those in treatment with a participating clinician; aged 18 to 75 years; English, Spanish or Mandarin speaking; and with no previous exposure to the DECIDE-PA intervention. Patient exclusion criteria included positive screening for mania, psychosis, suicidal ideation, or cognitive impairment (screened in patients 65 years or older). Eligibility criteria were adjusted based on input from institutional review boards and clinics to exclude patients with severe mental health conditions. The age inclusion criterion was expanded to a range of 18 to 80 years, because several clinicians had few patients.

Settings

Participants were linked to 1 of 13 behavioral health clinics in Massachusetts that serve low-income minority patients. Clinics offered individual and group psychotherapy and pharmacologic services.

Procedures and Interventions

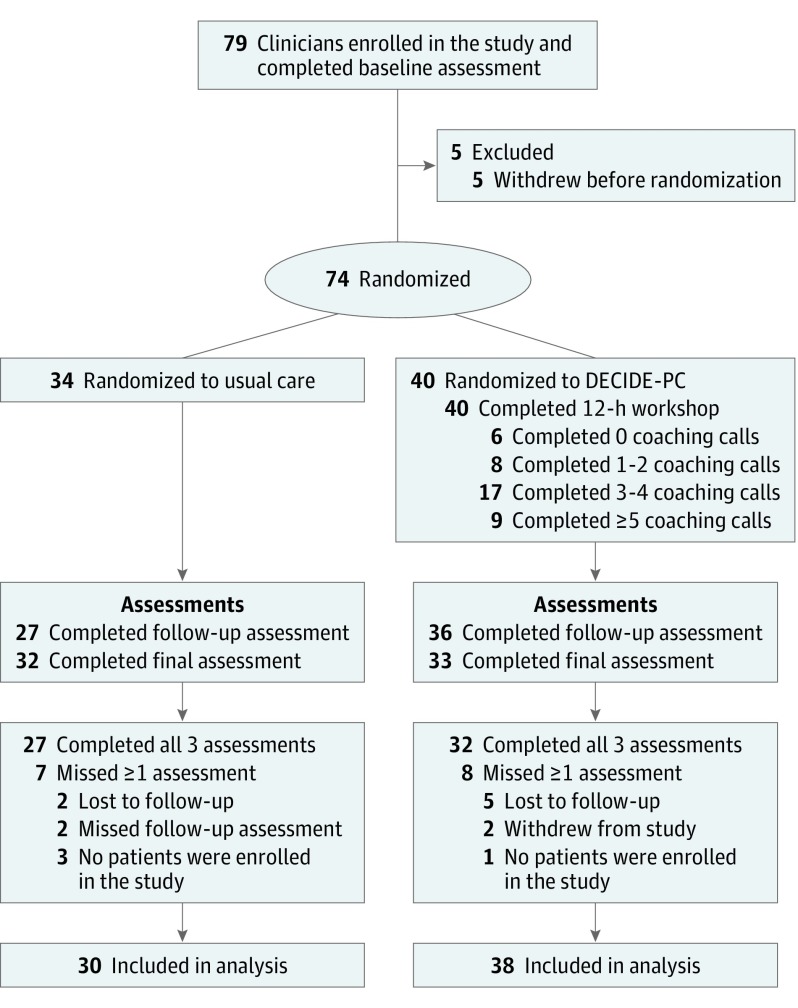

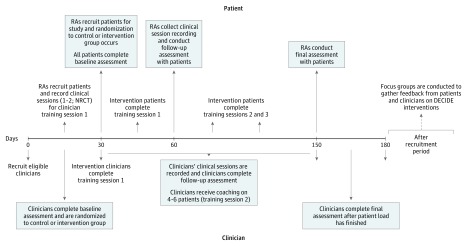

After enrollment, clinicians completed a 30-minute, in-person baseline assessment (with compensation of $50) and were randomized to intervention or control conditions (Figure 1). Clinicians received continuing education credits and $50 per completed assessment. Intervention clinicians participated in a 12-hour DECIDE-PC workshop (with compensation of $300). The training required examples of clinicians’ baseline therapeutic style. Research assistants (RAs) blinded to clinician assignment enrolled 1 to 2 training patients per clinician and audio recorded a clinical session (95 patients who received a $20 gift card).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram of Clinician Intervention.

Six clinicians (4 usual care and 2 intervention) were excluded from analysis owing to not having patients enrolled. Two of these 6 clinicians (1 usual care and 1 intervention) also had incomplete data owing to being lost to follow-up and were categorized as being such. DECIDE-PC indicates decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution (clinician version).

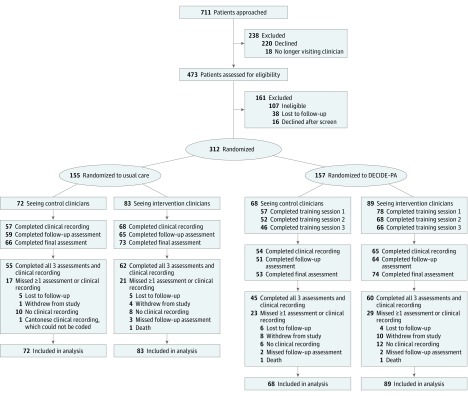

Blinded RAs next enrolled as many as 9 patients per clinician (mean [SD], 4.2 [2.3] patients), who were randomized by one of us (A.A.-B.) to intervention or control conditions (Figure 2). Patients received $25 for the first 2 assessments and $40 for the final one. Intervention patients participated in as many as 3 hours of training during approximately 5 months (with a $10 gift card for transportation).

Figure 2. CONSORT Diagram of Patient Intervention.

DECIDE-PA indicates decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution (patient version).

Clinician Intervention

Based on previous studies, the clinician intervention targeted the following 3 areas of patient-centered communication in promoting SDM: (1) perspective taking, (2) attributional errors, and (3) receptivity to patient participation and collaboration. The clinician intervention (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 2) was delivered by behavioral health professionals and communication experts (coaches) trained by one of us (M.A.). Clinicians first attended a 12-hour workshop (2-3 days) of lectures, videos, role-play, and feedback based on their audio-recorded clinical sessions, highlighting strengths and opportunities for improvement. Coaches coded behaviors (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 2) from 1 to 6 additional patient-clinician recorded sessions and offered individual feedback in 30- to 45-minute telephone calls. A final 45- to 60-minute telephone call summarized concepts and elicited feedback (eAppendix 3 in Supplement 2). Uptake of the optional coaching varied (mean [SD] number of sessions, 3.0 [2.0]), with 6 of the 40 intervention clinicians (15.0%) having 0 coaching sessions, 8 (20.0%) having 1 to 2, 17 (42.5%) having 3 to 4, and 9 (22.5%) having 5 or more. Six coaching sessions constituted the prespecified recommended dosage. Coaches provided telephone feedback (eAppendix 4 in Supplement 2).

The 34 clinicians in the usual care condition had sessions audio recorded and completed the assessments. Patients continued with usual treatment, completed 3 assessments, and had a recorded clinical session.

Patient Intervention

The patient training consisted of three 60-minute sessions balancing didactics with opportunities to engage, role-play, and reflect on activation (eAppendix 5 in Supplement 2). Bachelor’s-level care managers delivered the intervention under supervision from licensed, bilingual clinicians (including two of us [N.C. and A.P.]). The first session (decisions and agency) educated patients about their role, choices, and agency in clinical visits. The second session (role, process, and reason) taught skills to understand treatment decisions. The third session (self-efficacy and consolidation) encouraged patients to ask questions about conditions and treatment options. Overall attendance was 135 of 157 (86.0%) for session 1, 120 of 157 (76.4%) for session 2, and 112 of 157 (71.3%) for session 3.

Supervision, Fidelity, and Adherence to Intervention

Care managers attended supervisor-led training, role-play, and weekly supervision. Supervisors evaluated care managers’ fidelity to the patient intervention using a random sample of recorded trainings and a 58-item checklist of components. Fidelity of care managers for training sessions 1 to 3 was excellent for patients who spoke English (scored by supervisors as 87.2% to 91.4% of the maximum score), Spanish (scored by supervisors as 80.9% to 86.7% of the maximum score), and Mandarin (scored by supervisors as 74.3%to 87.1% of the maximum score). Supervisors provided feedback biweekly to care managers.

Outcomes

Six trained, blinded coders assessed SDM in each session using the 12-item Observing Patient Involvement in Shared Decision-Making (OPTION) instrument. Coders listened to audio-recorded therapy sessions and rated them on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (behavior not observed) to 4 (behavior exhibited to a high standard). Final scores were summed and transformed to a scale ranging from 0 (lowest SDM) to 100 (highest SDM). Good intercoder reliability was observed (intercorrelation coefficient, 0.53) across 10 sessions using 2-way mixed, absolute agreement. Coders rated a mean (SD) of 70.6 (67.3) sessions (eMethods 1 in Supplement 2). The patient and clinician versions of the 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire were used to evaluate patient and clinician SDM. Ratings are summed (range, 0-45) and transformed to a scale ranging from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest). These measures have been frequently used with English and Spanish speakers and show good psychometric properties (α = .88 for patients; α = .89 for clinicians). We administered the patient Perceptions of Care Survey–Global Evaluation of Care Scale (POC) to evaluate the patient’s subjective rating of care and whether they would recommend that clinician. The 3 items of the POC are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always), summed and transformed to a score from 0 (lowest quality) to 100 (highest quality). Patients also completed the Communication subscale of the Kim Alliance Scale (α = .77) and the Working Alliance Inventory (α = .90). Clinician and patient outcomes were assessed at baseline, approximately 2 months after baseline, and 4 to 6 months after baseline (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Study Design.

The DECIDE trial includes the following: decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution. NRCT indicates nonrandomized clinical trial; RA, research assistant.

Sample Size Determination

Clinician sample size (n = 74) was determined by clinician availability. Patient sample size (n = 300) was based on power analysis assuming analysis of covariance. This design provides approximate power of 80% (Cohen d = 0.30) to 90% (Cohen d = 0.35), assuming no clinician cluster effects. Evaluation of assumptions is found in eMethods 2 in Supplement 2.

Randomization

The project coordinator randomized clinicians to intervention or control conditions and randomized patients within clinicians by site in a 1:1 ratio for each 2-person block. When recruitment was uneven per site, the last clinician was assigned to the intervention condition. Patient randomization streams were stratified by site and clinician using Stata-generated random numbers.

Procedure

Research staff enrolled 79 eligible clinicians; 74 agreed to randomization. Research assistants approached patient participants in clinic waiting rooms; 312 eligible patients were randomized (Figure 1). Research assistants were blinded to patient and clinician study condition when administering assessments, and patients and clinicians were blinded to the other’s intervention status.

Statistical Analysis

We first examined descriptive information on clinical and demographic characteristics and determined whether missing value patterns varied by study condition. To account for missing data, we applied multiple imputation using Stata chained equations (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2). Primary outcomes included (1) independent-coder OPTION assessment of SDM based on clinical recording at follow-up, (2) clinician perception of SDM, (3) patient perception of SDM, and (4) patient-reported quality of care (POC score) at final assessment.

We estimated a multilevel, mixed-effects model following intent-to-treat principles, with participants assigned to their randomization condition regardless of treatment receipt (eMethods 3 and eFigures 1-4 in Supplement 2). Differences were minimal between patients or clinicians with and without missing data; 52 (33.1%) of intervention patients did not complete at least 1 follow-up assessment and/or had no final session recorded (Figure 1 and eTables 1-2 in Supplement 2). Missing outcome data ranged from 48 (15.4%) for patient-reported POC to 68 (21.8%) for the OPTION assessment, with no significant differences across the 4 design arms for the OPTION assessment (χ2 = 2.17; P = .54), patient perception (χ2 = 7.11; P = .07), clinician perception (χ2 = 2.96; P = .40), and patient-reported POC (χ2 = 6.65; P = .08). The intervention variables were effect coded (ie, −0.5 assigned to control, +0.5 assigned to intervention), and the coefficients estimated differences between the treatment and control groups. We included the interaction term DECIDE-PA × DECIDE-PC. To correct for multiplicity of tests, we calculated an omnibus test with 3 df. The hierarchical nature of models and robust standard errors accounted for nonindependence of patients seeing the same clinician.

We also examined whether outcomes varied with treatment dosage, a continuous variable calculated as the number of coaching sessions divided by the number of intended treatment sessions (3 for patients and 6 for clinicians). This variable ranged from 0 (no dosage) to 1 (intended dosage or more). Dosage was calculated separately for 2-month and final assessments and was fixed to 0 for the control group. We reduced the dosage by half if clinicians did not have recorded sessions and centered dosage at the mean number of training sessions. Dosage varied in part because RAs were blinded to study assignment and scheduled assessments per set time frames, resulting in 29 intervention patients (18.5%) completing follow-up before the intervention. We adjusted for possible confounders such as the patients’ race, sex, educational level, and age and the clinicians’ race, sex, and age (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Adjusted results did not differ from those of the model with no covariates.

We estimated the role of patient-clinician communication and working alliance as prespecified mediators using Stata and Mplus software following the approach of Baron and Kenny (eMethods 2 in Supplement 2). We also included the main effects of racial/ethnic groups (and separately, language preference), racial/ethnic discordance, and the interaction terms of discordance with interventions. We computed P values for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between intervention and control groups using the Pearson χ2 test for categorical variables and unpaired t tests for continuous variables. In the regression analysis, we computed P values with t tests adjusted for multiple imputation and small sample size.

Results

Recruitment of clinicians began September 1, 2013; recruitment of patients, November 3, 2013. The final follow-up interview was conducted September 30, 2016. Of 312 randomized patients, 212 (67.9%) were female and 100 (32.1%) were male; mean (SD) age was 44.0 (15.0) years. Of 74 randomized clinicians, 56 (75.7%) were female and 18 (4.3%) were male; mean (SD) age was 39.8 (12.5) years. Table 1 presents participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics; there were no significant differences between intervention and control groups.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patient and Clinician Participantsa.

| Characteristics in RCT Participants | Clinician Group | χ2 or t Test | P Value | Patient Group | χ2 or t Test | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 74) | Control (n = 34) | Intervention (n = 40) | All (n = 312) | Control (n = 155) | Intervention (n = 157) | |||||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| Male | 18 (24.3) | 10 (29.4) | 8 (20.0) | 0.88 | .35 | 100 (32.1) | 48 (31.0) | 52 (33.1) | 0.17 | .68 |

| Female | 56 (75.7) | 24 (70.6) | 32 (80.0) | 212 (67.9) | 107 (69.0) | 105 (66.9) | ||||

| Age range, No. (%)b | ||||||||||

| 18-34 y | 36 (48.6) | 17 (50.0) | 19 (47.5) | 1.46 | .83 | 94 (30.1) | 51 (32.9) | 43 (27.4) | 1.98 | .58 |

| 35-49 y | 18 (24.3) | 8 (23.5) | 10 (25.0) | 95 (30.4) | 42 (27.1) | 53 (33.8) | ||||

| 50-64 y | 15 (20.3) | 6 (17.6) | 9 (22.5) | 98 (31.4) | 49 (31.6) | 49 (31.2) | ||||

| ≥65 y | 4 (5.4) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (5.0) | 25 (8.0) | 13 (8.4) | 12 (7.6) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| Non-Latino white | 43 (58.1) | 19 (55.9) | 24 (60.0) | 0.50 | .92 | 112 (35.9) | 55 (35.5) | 57 (36.3) | 1.73 | .63 |

| Latino | 15 (20.3) | 8 (23.5) | 7 (17.5) | 131 (42.0) | 63 (40.6) | 68 (43.3) | ||||

| Non-Latino black | 4 (5.4) | 2 (5.9) | 2 (5.0) | 34 (10.9) | 16 (10.3) | 18 (11.5) | ||||

| Asian | 12 (16.2) | 5 (14.7) | 7 (17.5) | 35 (11.2) | 21 (13.5) | 14 (8.9) | ||||

| Language, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| English | 52 (70.3) | 22 (64.7) | 30 (75.0) | 2.76 | .43 | 174 (55.8) | 90 (58.1) | 84 (53.5) | 1.47 | .69 |

| Spanish | 12 (16.2) | 7 (20.6) | 5 (12.5) | 103 (33.0) | 48 (31.0) | 55 (35.0) | ||||

| Chinese | 4 (5.4) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (2.5) | 20 (6.4) | 11 (7.1) | 9 (5.7) | ||||

| Other | 6 (8.1) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (10.0) | 15 (4.8) | 6 (3.9) | 9 (5.7) | ||||

| Region of origin, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| North America | 45 (60.8) | 19 (55.9) | 26 (65.0) | 4.03 | .40 | 177 (56.7) | 90 (58.1) | 87 (55.4) | 2.79 | .59 |

| Central and South America | 12 (16.2) | 8 (23.5) | 4 (10.0) | 58 (18.6) | 27 (17.4) | 31 (19.7) | ||||

| Africa or Europe | 6 (8.1) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (10.0) | 9 (2.9) | 6 (3.9) | 3 (1.9) | ||||

| Asia or Pacific Islands | 10 (13.5) | 4 (11.8) | 6 (15.0) | 23 (7.4) | 13 (8.4) | 10 (6.4) | ||||

| Caribbean islands | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 45 (14.4) | 19 (12.3) | 26 (16.6) | ||||

| Highest educational level, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| 0-6th grade | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 22 (7.1) | 10 (6.5) | 12 (7.6) | .41 | .94 |

| 7th-11th grade | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 54 (17.3) | 26 (16.8) | 28 (17.8) | ||

| 12th grade | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 54 (17.3) | 26 (16.8) | 28 (17.8) | ||

| >12th grade | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 182 (58.3) | 93 (60.0) | 89 (56.7) | ||

| Employment status, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| Employed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 200 (64.1) | 102 (65.8) | 98 (62.4) | .39 | .53 |

| Not employed | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 112 (35.9) | 53 (34.2) | 59 (37.6) | ||

| Personal income, $c,d | ||||||||||

| <12 000 | 8 (10.8) | 3 (8.8) | 5 (12.5) | 3.74 | .44 | 182 (58.3) | 92 (59.4) | 90 (57.3) | 4.02 | .40 |

| 12 000-29 999 | 8 (10.8) | 3 (8.8) | 5 (12.5) | 64 (20.5) | 28 (18.1) | 36 (22.9) | ||||

| 30 000-74 999 | 36 (48.6) | 15 (44.1) | 21 (52.5) | 39 (12.5) | 24 (15.5) | 15 (9.6) | ||||

| ≥75 000 | 20 (27.0) | 11 (32.4) | 9 (22.5) | 15 (4.8) | 6 (3.9) | 9 (5.7) | ||||

| Specialty, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| Psychiatrist | 20 (27.0) | 12 (35.3) | 8 (20.0) | 3.92 | .42 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Psychologist | 16 (21.6) | 6 (17.6) | 10 (25.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Social worker | 24 (32.4) | 9 (26.5) | 15 (37.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Nurse | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Other (clinician, licensed mental health counselor) | 13 (17.6) | 6 (17.6) | 7 (17.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Mean (SD) No. of coaching sessions clinicians received [No. of participants]e | ||||||||||

| Follow-up assessment | 0.9 (1.0) [66] | 0 (0) [30] | 1.6 (0.8) [36] | −11.70 | <.001 | 0.9 (1.4) [274] | 0.8 (1.2) [140] | 1.1 (1.5) [134] | −1.61 | .11 |

| Final assessment | 1.8 (2.0) [67] | 0 (0) [30] | 3.2 (1.6) [37] | −11.28 | <.001 | 1.9 (2.3) [288] | 1.7 (2.2) [145] | 2.0 (2.4) [143] | −1.05 | .30 |

| Mean (SD) No. of training sessions patients received [No. of participants] | ||||||||||

| Follow-up assessment | 0.6 (0.5) [68] | 0.7 (0.5) [30] | 0.6 (0.5) [38] | 0.61 | .54 | 0.7 (1.0) [274] | 0 (0) [155] | 1.5 (1.1) [119] | −17.10 | <.001 |

| Final assessment | 1.0 (0.6) [68] | 1.0 (0.5) [30] | 1.1 (0.7) [38] | −0.81 | .42 | 1.1 (1.4) [287] | 0 (0) [155] | 2.3 (1.1) [132] | −26.24 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and clinicians are presented before the imputation of missing data. All missing data were imputed using multiple imputation before running analyses. Percentages have been rounded and may not total 100. All statistical analysis used χ2 tests for categorical variables and unpaired t tests for continuous variables.

Clinician age has 1 missing observation.

Clinician income has 2 missing observations.

Patient income has 12 missing observations.

The number of coaching sessions a clinician received can differ by patient. The numbers shown here are the means for clinicians’ dosages across all their patients (for whom dosage is nonmissing). Six clinicians did not have any patients in the trial and therefore were excluded when computing these dosage variables.

Table 2 presents the results of intention-to-treat analysis (312 patient-clinician dyads). The omnibus test of patient and clinician interventions on SDM was not significant (F3,1104.7 = 1.85; P = .14), indicating no overall combined intervention effect on SDM ratings at follow-up. However, the clinician intervention affected SDM (b = 4.52; SE = 2.17; P = .04; Cohen d = 0.29) as rated by blinded coders (eFigure 5 in Supplement 2). Intervention clinicians were rated 4.52 points higher on the OPTION assessment (overall mean [SD] score, 33.00 [15.43]). For quality of care, the omnibus test (F3,10515.7 = 3.15; P = .02) and specific effect of the patient intervention (b = 2.27; SE = 1.16; P = .05; Cohen d = 0.19) were significant, indicating that the intervention increased patient-perceived quality of care by 2.27 points on a 100-point scale (overall mean [SD], 89.9 [12.00]). We found no significant intervention effects for patient-perceived SDM (F3,4171.4 = 0.64; P = .59) or clinician-perceived SDM (F3,1339.8 = 0.66; P = .57) and no individually significant coefficients.

Table 2. Analysis of DECIDE Patient and Clinician Interventions on Primary Outcomesa.

| Analysis | Blinded Coder SDM | P Value | Patient-Reported SDM | P Value | Clinician-Reported SDM | P Value | Global Evaluation of Care | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-Treat Analysis | ||||||||

| Main effect of patient intervention, b (SE) [Cohen d] | 0.36 (1.56) [0.02] | .82 | 1.45 (2.17) [0.07] | .51 | 1.15 (1.20) [0.08] | .34 | 2.27 (1.16) [0.19] | .05 |

| Main effect of clinician intervention, b (SE) [Cohen d] | 4.52 (2.17) [0.29] | .04 | −0.86 (2.16) [−0.04] | .69 | 0.51 (2.45) [0.03] | .83 | 1.74 (1.46) [0.14] | .23 |

| Patient × clinician intervention, b (SE) [Cohen d] | 2.52 (3.05) [0.16] | .41 | 4.78 (4.61) [0.23] | .30 | −2.15 (2.30) [−0.14] | .35 | 2.56 (2.32) [0.21] | .27 |

| Baseline outcome measures, b (SE) | 0.05 (0.04) | .22 | 0.45 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.54 (0.11) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.07) | <.001 |

| Intercept, b (SE) | 28.44 (3.45) | <.001 | 41.06 (4.93) | <.001 | 29.78 (8.23) | <.001 | 44.88 (6.59) | <.001 |

| Random effect at clinician level, b (SE) | 6.21 (1.04) | <.001 | 0.66 (6.98) | .97 | 7.79 (1.05) | <.001 | 3.42 (0.75) | <.001 |

| Intervention joint significance test | F3,1104.7 = 1.85 | .14 | F3,4171.4 = 0.64 | .59 | F3,1339.8 = 0.66 | .57 | F3,10515.7 = 3.15 | .02 |

| Between patient outcome SDb | 15.43 | NA | 20.70 | NA | 14.88 | NA | 12.00 | NA |

| Dosage Analysis | ||||||||

| Patient dosage, b (SE) [Cohen d] | 1.37 (2.12) [0.09] | .52 | 2.46 (2.20) [0.12] | .26 | 2.81 (2.02) [0.19] | .16 | 3.33 (1.17) [0.28] | .004 |

| Clinician dosage, b (SE) [Cohen d] | 12.01 (3.72) [0.78] | .001 | −2.63 (2.72) [−0.13] | .33 | −0.64 (3.57) [−0.04] | .86 | 0.16 (2.64) [0.01] | .95 |

| Patient dosage × clinician dosage, b (SE) [Cohen d] | −0.07 (9.93) [0.00] | >.99 | 10.37 (6.57) [0.50] | .12 | −11.67 (7.41) [−0.78] | .12 | 7.40 (3.56) [0.62] | .04 |

| Baseline outcome measures. b (SE) | 0.05 (0.04) | .24 | 0.45 (0.06) | <.001 | 0.54 (0.11) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.07) | <.001 |

| Intercept, b (SE) | 28.94 (3.44) | <.001 | 40.95 (5.00) | <.001 | 30.29 (8.19) | <.001 | 44.72 (6.54) | <.001 |

| Random effect at clinician level, b (SE) | 6.04 (1.03) | <.001 | 0.51 (5.49) | .95 | 7.67 (1.05) | <.001 | 3.54 (0.78) | <.001 |

| Intervention joint significance test | F3,1696.3 = 3.45 | .02 | F3,3888.7 = 1.40 | .24 | F3,1510.0 = 1.42 | .24 | F3,5153.1 = 8.66 | <.001 |

| Between-patient outcome SDb | 15.43 | 20.70 | 14.88 | 12.00 | ||||

Abbreviations: DECIDE, decide the problem; explore the questions; closed or open-ended questions; identify the who, why, or how of the problem; direct questions to your health care professional; enjoy a shared solution; SDM, shared decision making.

Includes 312 participants. Data include robust empirical standard errors. Dummy variables are effect-coded. P values were computed using t tests adjusted for multiple imputation and small sample size.

Indicates the SD of the outcome variable across all patients in the data. Patient-clinician dyads with missing observations were analyzed using multiple imputation.

To examine whether the intention-to-treat findings were owing to variability in the number of sessions received, we examined the association of the primary outcomes with training dosage (Table 2). For blinded-coder SDM, the omnibus test for training dosage was significant (F3,1696.3 = 3.45; P = .02). Blinded-coder SDM ratings at follow-up increased significantly by 12.01 points when clinicians received the recommended 6 sessions compared with clinicians without coaching (b = 12.01; SE = 3.72; P = .001; Cohen d = 0.78).

We also found an overall association of dosage with global evaluation of care at the final assessment (F3,5153.1 = 8.66; P < .001). Patient dosage was statistically significant (b = 3.33; SE = 1.17; P = .004; Cohen d = 0.28), and although clinician dosage was not (b = 0.16; SE = 2.64; P = .95; Cohen d = 0.01), the combined effect of patient and clinician dosage was significant (b = 7.40; SE = 3.56, P = .04; Cohen d = 0.62). Maximum benefit occurred when clinicians and patients obtained the recommended dosage (eFigure 6 in Supplement 2). We found no association jointly or individually between dosage and patient-reported SDM (F3,3888.7 = 1.40; P = .24) or between dosage and clinician-reported SDM (F3,1510.0 = 1.42; P = .24). Results are similar when the dosage is not right-censored at the recommended dosage (eTable 4 in Supplement 2).

Mediation Analyses

We explored whether patient evaluation of communication (Kim Alliance Scale Communication subscale) or working alliance (Working Alliance Inventory) served as mediators in the association between the patient intervention and global evaluation of care. We found evidence of partial mediation of the patient intervention effect through communication for the intention-to-treat effect (original, 2.87; indirect, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.06-2.27; Cohen d = 0.09) and the patient dosage effect (original, 3.13; indirect, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.12-2.25; Cohen d = 0.10). In addition, we found evidence of partial mediation of the patient intervention effect through working alliance for the intention-to-treat effect (original, 2.73; indirect, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.06-2.76; Cohen d = 0.11) and the patient dosage effect (original, 3.03; indirect, 1.37; 95% CI, 0.11-2.96; Cohen d = 0.13). We found no evidence that communication or working alliance mediated the effect of the clinician intervention on SDM OPTION assessment, suggesting that the observed intervention effect on SDM is not owing to improved perceptions of communication or working alliance within dyads.

Moderation Analyses

In moderation analyses (eTable 5 in Supplement 2), we found that the intervention effects on SDM were robust to patient and clinician racial/ethnic and linguistic discordance because omnibus tests were not significant (F3,982.2 = 0.69 [P = .56] and F3,1373.6 = 1.13 [P = .34], respectively). Similarly, we found no moderation effects for global evaluation of care with respect to racial/ethnic or linguistic discordance, with insignificant omnibus tests (F3,3445.6 = 0.74 [P = .53] and F3,1732.7 = 1.39 [P = .25], respectively). The clinician intervention seemed to affect patient global evaluation of care more strongly when patients and clinicians did not have the same primary language (b = 4.91; SE = 2.38; P = .04; Cohen d = 0.41).

Discussion

Our study was, to our knowledge, the first to investigate the effectiveness of patient and clinician interventions to improve SDM in behavioral health care among an ethnically and racially diverse patient sample. The clinician intervention improved SDM with small to moderate effect sizes and more strongly when the patient and clinician had different primary languages. Training clinicians on SDM can facilitate identification of patient preferences. The intervention may have a stronger effect on patient global evaluation of care in linguistically discordant patient-clinician relationships requiring greater clinician effort and a subjectively different, more apparent SDM experience for the patient. Non–English-speaking patients may also have more cultural distance from English-speaking clinicians and, under distress, are less able to express preferences.

Our assumption that the patient intervention would lead to increased SDM was not supported, maybe owing to conducting some training by telephone. The patient intervention did not teach patients about SDM but rather focused on asking questions, identifying resources, and communicating preferences. Preparing patients for SDM during the clinical session should be made explicit. The finding of no association jointly or individually between dosage and patient- or clinician-reported SDM might be related to the challenge of detecting changed interactions during the clinical visit. Overall, clinicians may fail to recognize SDM advantages and coaching improvements because much of the clinician behavior change across interactions was only observed by the blinded coder. Clinicians may need to hear audiotaped sections before and after coaching to recognize their changes in attributional errors, perspective taking, and receptivity to collaboration and how these affect their patients. Similarly, video training for patients in SDM could facilitate recognizing these behaviors.

The patient intervention increased perception of quality of care by increasing patient opportunities to voice concerns or topics through inquiry. We hypothesized synergistic effects of the combined intervention on quality of care, and maximum benefit was observed when patients and clinicians obtained the recommended training dosage. This observation suggests the importance of preparing for changes in power dynamics that require clinician receptivity to patient activation and patient trust. In these instances, clinicians might be more receptive to patient queries and patients more trusting and confident in testing their skills.

Limitations

One limitation of our study is the low intervention dosage for clinicians, which can lead to a conservative clinician intervention effect. The low to medium clinician participation in coaching before follow-up (mean [SD], 1.6 [0.8] sessions) and final assessment (mean [SD], 3.2 [1.6] sessions) suggests that time constraints can hinder engagement. Intervention effects could be strengthened by incentivizing adequate training dosage.

Another limitation was assessment of multiple measures of SDM and testing both interventions simultaneously. Although we analyzed multivariate significance tests, only replication studies on independent samples can prevent false-positive findings entirely. We used an inclusive definition of decision, which could dilute the observed effect. Training clinicians and patients to explicitly discuss common decisions (eg, next appointment date or use of decision aids) could strengthen SDM. Finally, because the clinician intervention varied by patient needs, we could not standardize adherence.

Conclusions

The study’s heterogeneous sample of participants speaking diverse languages at different clinics with different coaches expands its generalizability. Our findings reveal how professional knowledge and collaborative dialogue can coexist. Results suggest that an adequate threshold of SDM training promotes a gradual philosophical transformation for clinicians, whereby patient preferences, choices, and agency come to the forefront, all of which are important components of achieving better health outcomes.

Trial Protocol

eAppendices 1-5. DECIDE Intervention Materials

eMethods 1. Coder Training

eMethods 2. Analytical Method: Data Preparation

eMethods 3. Analytical Method: Data Analysis

eFigure 1. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for SDM Option (n = 240)

eFigure 2. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Patient-Reported SDM (n = 259)

eFigure 3. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Provider-Reported SDM (n = 237)

eFigure 4. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Perception of Care (n = 263)

eFigure 5. Means of Blind-Coded SDM by the Number of Coaching Sessions Providers Received at Follow-up Assessment (n = 312)

eFigure 6. The Effect of Patient Dosage on Patients’ Perceived Global Evaluation of Care (n = 312)

eTable 1. Comparison of Patient Baseline Characteristics With and Without Missing Data in Outcome Measures (n = 312)

eTable 2. Comparison of Provider Baseline Characteristics With and Without Missing Assessments (n = 74)

eTable 3. Dosage Analysis of DECIDE-PA and PC Intervention on Primary Outcomes With Covariates (n = 312)

eTable 4. Dosage Analysis of DECIDE-PA and PC Intervention on Primary Outcomes Without Using Recommended Dosage Cutoff Threshold (n = 312)

eTable 5. Moderation Analysis of Racial and Linguistic Discordance on Patient and Provider Intervention on Primary Outcomes (n = 312)

References

- 1.Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, Kohn LT, Maguire SK, Pike KC. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan E, Best C, Hagen S. Shared decision making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1(1):CD007297. doi: 10.1002/14651858,CD007297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.New Freedom Commission on Mental Health Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America: Final Report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. DHHS publication SMA-03-3832. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SR, Bakken S, Ruland C. Recent advances in shared decision making for mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(6):606-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson KA, Bastani R, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Ford DE. Effect of mental health care and shared decision making on patient satisfaction in a community sample of patients with depression. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(4):416-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wills CE, Holmes-Rovner M. Integrating decision making and mental health interventions research: research directions. Clin Psychol (New York). 2006;13(1):9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, et al. . Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):542-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Légaré F, Stacey D, Turcotte S, et al. . Interventions for improving the adoption of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5(9):CD006732. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diouf NT, Menear M, Robitaille H, Painchaud Guérard G, Légaré F. Training health professionals in shared decision making: update of an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(11):1753-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durand M-A, Carpenter L, Dolan H, et al. . Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz JN, Lyons N, Wolff LS, et al. . Medical decision-making among Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites with chronic back and knee pain: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12(1):78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Norton WE, Gaertner SL, Shelton JN. Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):478-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnittker J, Pescosolido BA, Croghan TW. Are African Americans really less willing to use health care? Soc Probl. 2005;52(2):255-271. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess D, van Ryn M, Dovidio J, Saha S. Reducing racial bias among health care providers: lessons from social-cognitive psychology. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):882-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40(1)(suppl):I140-I151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Haene L, Rober P, Adriaenssens P, Verschueren K. Voices of dialogue and directivity in family therapy with refugees: evolving ideas about dialogical refugee care. Fam Process. 2012;51(3):391-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mikesell L, Bromley E, Young AS, Vona P, Zima B. Integrating client and clinician perspectives on psychotropic medication decisions: developing a communication-centered epistemic model of shared decision making for mental health contexts. Health Commun. 2016;31(6):707-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herselman S. Some problems in health communication in a multicultural clinical setting: a South African experience. Health Commun. 1996;8(2):153-170. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degni F, Suominen S, Essén B, El Ansari W, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Communication and cultural issues in providing reproductive health care to immigrant women: health care providers’ experiences in meeting the needs of Somali women living in Finland [published correction in J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):344]. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):330-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen GT, Barg FK, Armstrong K, Holmes JH, Hornik RC. Cancer and communication in the health care setting: experiences of older Vietnamese immigrants, a qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(1):45-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alegría M, Polo A, Gao S, et al. . Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Med Care. 2008;46(3):247-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortes DE, Mulvaney-Day N, Fortuna L, Reinfeld S, Alegría M. Patient-provider communication: understanding the role of patient activation for Latinos in mental health treatment. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(1):138-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alegría M, Carson N, Flores M, et al. . Activation, self-management, engagement, and retention in behavioral health care: a randomized clinical trial of the DECIDE intervention. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):557-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ault-Brutus A, Lee C, Singer S, Allen M, Alegría M. Examining implementation of a patient activation and self-management intervention within the context of an effectiveness trial. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41(6):777-787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making–pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alegría M, Nakash O, Lapatin S, et al. . How missing information in diagnosis can lead to disparities in the clinical encounter. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(6)(suppl):S26-S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alegría M, Roter DL, Valentine A, et al. . Patient-clinician ethnic concordance and communication in mental health intake visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):188-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen DC, Miller AB, Nakash O, Halpern L, Alegría M. Interpersonal complementarity in the mental health intake: a mixed-methods study [correction appears in J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(2):196]. J Couns Psychol. 2012;59(2):185-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulvaney-Day NE, Earl TR, Diaz-Linhart Y, Alegría M. Preferences for relational style with mental health clinicians: a qualitative comparison of African American, Latino and non-Latino white patients. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(1):31-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galinsky AD, Magee JC, Inesi ME, Gruenfeld DH. Power and perspectives not taken. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(12):1068-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakash O, Alegría M. Examination of the role of implicit clinical judgments during the mental health intake. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(5):645-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katz AM, Alegría M. The clinical encounter as local moral world: shifts of assumptions and transformation in relational context. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1238-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog: a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021-1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polo AJ, Alegría M, Sirkin JT. Increasing the engagement of Latinos in services through community-derived programs: the Right Question Project–Mental Health. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2012;43(3):208-216. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A, et al. . The OPTION scale: measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expect. 2005;8(1):34-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. . Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kriston L, Scholl I, Hölzel L, Simon D, Loh A, Härter M. The 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9): development and psychometric properties in a primary care sample. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):94-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholl I, Kriston L, Dirmaier J, Buchholz A, Härter M. Development and psychometric properties of the Shared Decision Making Questionnaire–physician version (SDM-Q-Doc). Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):284-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Operskalski BH. Randomized trial of a telephone care management program for outpatients starting antidepressant treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(10):1441-1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De las Cuevas C, Rivero-Santana A, Perestelo-Pérez L, Pérez-Ramos J, Serrano-Aguilar P. Attitudes toward concordance in psychiatry: a comparative, cross-sectional study of psychiatric patients and mental health professionals. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodenburg-Vandenbussche S, Pieterse AH, Kroonenberg PM, et al. . Dutch translation and psychometric testing of the 9-item Shared Decision Making Questionnaire (SDM-Q-9) and Shared Decision Making Questionnaire–Physician Version (SDM-Q-Doc) in primary and secondary care. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eisen SV, Wilcox M, Idiculla T, Speredelozzi A, Dickey B. Assessing consumer perceptions of inpatient psychiatric treatment: the Perceptions of Care Survey. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28(9):510-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim SC, Boren D, Solem SL. The Kim Alliance Scale: development and preliminary testing. Clin Nurs Res. 2001;10(3):314-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim SC, Kim S, Boren D. The quality of therapeutic alliance between patient and provider predicts general satisfaction. Mil Med. 2008;173(1):85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alvarez K, Wang Y, Alegria M, et al. . Psychometrics of shared decision making and communication as patient centered measures for two language groups. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(9):1074-1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Horvath A, Greenberg L. Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1989;36(2):223-233. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakash O, Nagar M, Kanat-Maymon Y. “What should we talk about?” the association between the information exchanged during the mental health intake and the quality of the working alliance. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(3):514-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.StataCorp LP. STATA Statistical Software, Release 14 [computer program]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

- 50.Raghunathan TE, Lepkowski JM, Van Hoewyk J, Solenberger P. A multivariate technique for multiply imputing missing values using a sequence of regression models. Surv Methodol. 2001;27(1):85-96. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muthen LK, Muthen BO Mplus User’s Guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2012.

- 54.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conover WJ. Practical Nonparametric Statistics. 3rd ed New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li KH, Meng XL, Raghunathan TE, Rubin DB. Significance levels from repeated P-values with multiply imputed data. Stat Sin. 1991;1:65-92. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barnard J, Rubin DB. Small-sample degrees of freedom with multiple imputation. Biometrika. 1999;86:948-955. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hawley ST, Morris AM. Cultural challenges to engaging patients in shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):18-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Loh A, Simon D, Wills CE, Kriston L, Niebling W, Härter M. The effects of a shared decision-making intervention in primary care of depression: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):324-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald JL. Beyond the critical period: processing-based explanations for poor grammaticality judgment performance by late second language learners. J Mem Lang. 2006;55(3):381-401. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tai-Seale M, Elwyn G, Wilson CJ, et al. . Enhancing shared decision making through carefully designed interventions that target patient and provider behavior. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):605-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. . The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796-804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Roter DL. Patient participation in the patient-provider interaction: the effects of patient question asking on the quality of interaction, satisfaction and compliance. Health Educ Monogr. 1977;5(4):281-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamann J, Heres S. Adapting shared decision making for individuals with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1483-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendices 1-5. DECIDE Intervention Materials

eMethods 1. Coder Training

eMethods 2. Analytical Method: Data Preparation

eMethods 3. Analytical Method: Data Analysis

eFigure 1. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for SDM Option (n = 240)

eFigure 2. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Patient-Reported SDM (n = 259)

eFigure 3. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Provider-Reported SDM (n = 237)

eFigure 4. Distributions of Level 1 Residuals and Random Intercepts in Unimputed Intention-to-Treat Analysis for Perception of Care (n = 263)

eFigure 5. Means of Blind-Coded SDM by the Number of Coaching Sessions Providers Received at Follow-up Assessment (n = 312)

eFigure 6. The Effect of Patient Dosage on Patients’ Perceived Global Evaluation of Care (n = 312)

eTable 1. Comparison of Patient Baseline Characteristics With and Without Missing Data in Outcome Measures (n = 312)

eTable 2. Comparison of Provider Baseline Characteristics With and Without Missing Assessments (n = 74)

eTable 3. Dosage Analysis of DECIDE-PA and PC Intervention on Primary Outcomes With Covariates (n = 312)

eTable 4. Dosage Analysis of DECIDE-PA and PC Intervention on Primary Outcomes Without Using Recommended Dosage Cutoff Threshold (n = 312)

eTable 5. Moderation Analysis of Racial and Linguistic Discordance on Patient and Provider Intervention on Primary Outcomes (n = 312)