Abstract

A recently reported Pd-catalyzed method for oxidative imidoylation of C–H bonds exhibits unique features that have important implications for Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation catalysis: (1) The reaction tolerates heterocycles that commonly poison Pd catalysts. (2) The site selectivity of C–H activation is controlled by an N-methoxyamide group rather than a suitably positioned heterocycle. (3) A Pd0 source, Pd2(dba)3 (dba = dibenzylideneacetone), is superior to Pd(OAc)2 as a precatalyst, and other PdII sources are ineffective. (4) The reaction performs better with air, rather than pure O2. The present study elucidates the origin of these features. Kinetic, mechanistic, and in situ spectroscopic studies establish that PdII-mediated C–H activation is the turnover-limiting step. The tBuNC substrate is shown to coordinate more strongly to PdII than pyridine, thereby contributing to the lack of heterocycle catalyst poisoning. A well-defined PdII–peroxo complex is a competent intermediate that promotes substrate coordination via proton-coupled ligand exchange. The effectiveness of this substrate coordination step correlates with the basicity of the anionic ligands coordinated to PdII, and Pd0 catalyst precursors are most effective because they selectively afford the PdII–peroxo in situ. Finally, elevated O2 pressures are shown to contribute to background oxidation of the isonitrile, thereby explaining the improved performance of reactions conducted with air rather than 1 atm O2. These collective results explain the unique features of the aerobic C–H imidoylation of N-methoxybenzamides and have important implications for other Pd-catalyzed aerobic C–H oxidation reactions.

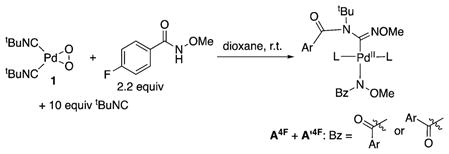

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

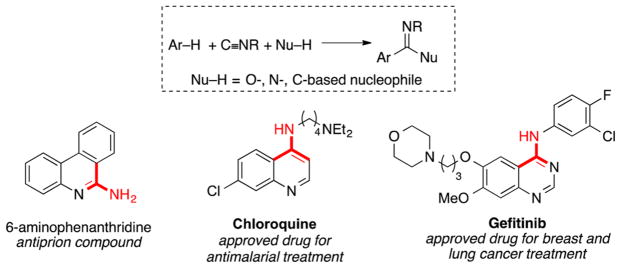

Catalytic carbonylation and imidoylation reactions provide an appealing strategy to introduce carbonyl and imine groups into organic compounds, and they are widely used in the preparation of pharmaceuticals and other industrial chemicals.1 The importance of nitrogen-based functional groups in bioactive compounds contributes to the appeal of catalytic imidoylation reactions. Methods for C–H imidoylation could provide streamlined synthetic routes to versatile pharmacophores (e.g., Scheme 1),2,3 and recent advances in Pd-catalyzed C–H imidoylation methods have led to methods for the following: preparation of 4-amino-substituted quinolines and quinazolines;3a,g,i regioselective functionalization of indoles, including C2- and C3-cyanation3d,e (via in situ loss of a tert-butyl group derived from tBuNC) and C3 amidation;3f syntheses of 6-aminophenanthridines (following removal of a tBu group);3h and preparation of iminoisoindolinones.4–6

Scheme 1.

Arene C–H Imidoylation Reactions and Relevant Bioactive Molecules Containing Prospective Fragments Derived from Isonitriles

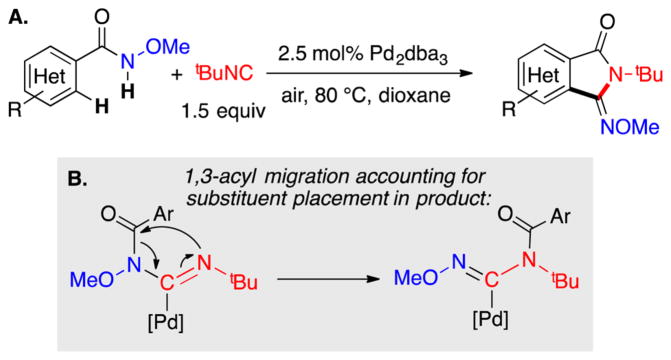

In 2014, Yu and co-workers reported Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative C–H imidoylation reactions for the conversion of N-methoxybenzamides to iminoisoindolinones (Scheme 2),4 which generate the N-substitution pattern in the product via in situ acyl migration, as depicted in Scheme 2B. The appealing synthetic utility of these reactions is complemented by a series of noteworthy mechanistic features that are not readily rationalized by earlier studies of Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions (Scheme 3).7 First, the reactions exhibit unique tolerance to heterocycles that commonly poison PdII oxidation catalysts, and when the substrate contains a heterocycle that could chelate to the Pd center (e.g., a 2-pyridyl fragment in Scheme 3A), the site selectivity is controlled by the N-methoxyamide group rather than the heterocycle.8 Second, a Pd0 source, Pd2(dba)3 (dba = dibenzylideneacetone), is superior to Pd(OAc)2 as a precatalyst, while other PdII sources [PdCl2, Pd(TFA)2, Pd(OTf)2] are completely ineffective (Scheme 3B). Finally, the reactions proceed with higher yields when air, rather than pure O2, is used as the source of oxidant (e.g., 94% versus 37%, respectively, in Scheme 3C). These observations have broad implications for the field of Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions, if they could be generalized and applied to other reaction classes.

Scheme 2.

(A) Pd-Catalyzed Aerobic C–H Imidoylation of N-Methoxybenzamides and (B) 1,3-Acyl Migration Step That Leads to Product Formation

Scheme 3.

Key Observations from the Aerobic Oxidative C–H Imidoylation of N-Methoxybenzamides

In an effort to elucidate the mechanistic basis for the observations summarized in Scheme 3, we have undertaken an experimental study of this Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative imidoylation reaction.9 Our efforts focused on determining the catalytic rate law, the turnover-limiting step(s), and the catalyst resting state through a series of kinetic and mechanistic studies and through the use of various spectroscopic methods, including NMR spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy, and operando X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Stoichiometric and catalytic studies with well-defined Pd complexes probed the reactivity of possible catalytic intermediates. Collectively, the results described herein draw attention to beneficial as well as deleterious effects of using O2 (or air) as the oxidant: the combination of O2 and Pd0 promotes substrate coordination to the catalyst center; however, higher O2 pressures contribute to background decomposition of the isonitrile substrate. The isonitrile plays an important role, not only as the substrate, but also as an ancillary ligand to prevent catalyst poisoning by heterocyclic substrates. These and other mechanistic data are presented and discussed within the broader context of Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

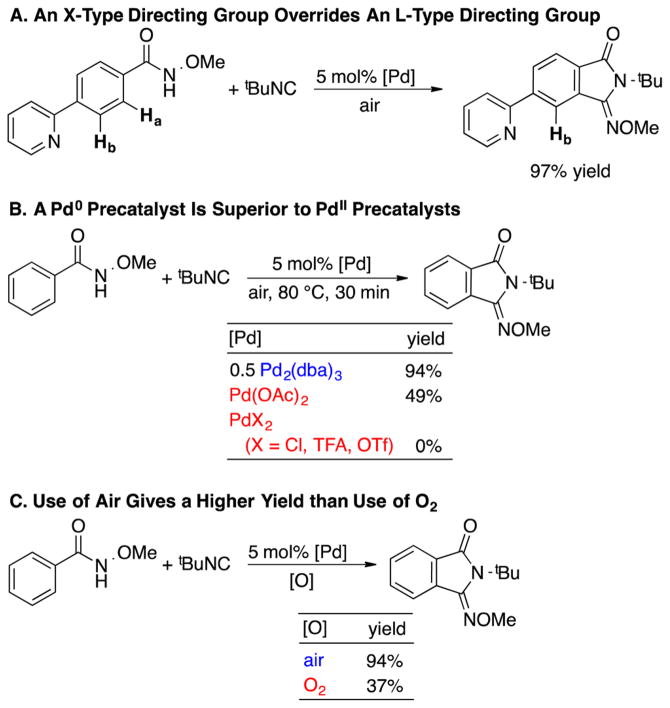

Kinetic Studies of the Catalytic Reaction

Initial-rate kinetic studies of the catalytic reactions were conducted as a first step in probing the mechanism of the reaction (Figure 1). The data show that the rate of product formation exhibits a first-order dependence on [Pd] (Figure 1A), a negligible kinetic dependence on [N-methoxybenzamide] from 13 to 100 mM (with 2.2 mM [Pd]), beyond which an inhibitory effect was observed (Figure 1B),10 and an inverse first-order dependence on [tBuNC] (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Kinetic data of the Pd-catalyzed aerobic C–H imidoylation of N-methoxybenzamide, assessing the dependence on (A) [Pd] (B) [N-methoxybenzamide] (C) [1/tBuNC]. Standard conditions: 1.1 mM Pd2(dba)3 ·CHCl3 (2.2 mol% [Pd]), 50 mM N-methoxybenzamide, 150 mM tBuNC, 1 atm air, dioxane, 60 °C. Standard conditions were employed, except for the concentration of the component being varied. Error bars reflect typical standard deviations observed when multiple data points were obtained at an individual concentration.

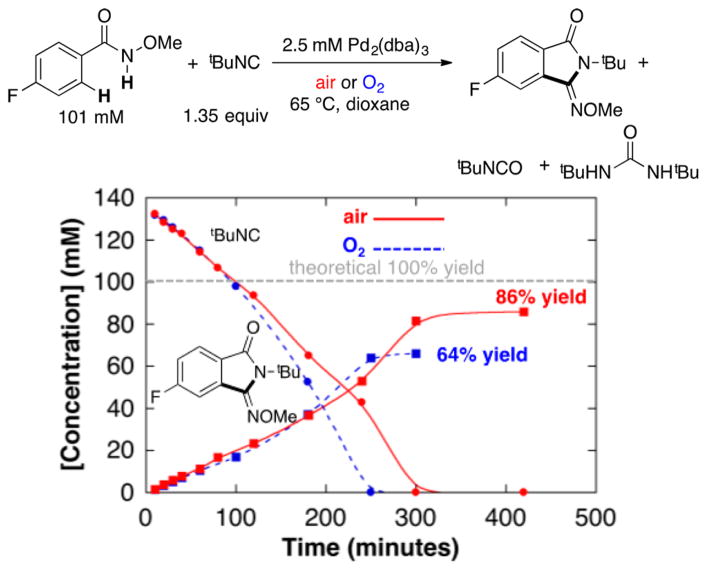

Identical initial rates were observed under 1 atm O2 and under air, reflecting a zero-order dependence of the reaction on pO2 (see first 200 min in Figure 2 and complementary data in Figure S2). Gas uptake data, together with product quantitation, show that all four oxidizing equivalents of O2 are used in the formation of organic products.11 Full time-course data from the reactions in Figure 2 reveal, however, that tBuNC is consumed more rapidly under O2 than under air at longer time periods.12 The latter feature limits the product yield due to complete consumption of the tBuNC substrate and accounts for the lower yield observed with O2 than with air. Isonitrile oxidation products include isocyanate tBuNCO and urea (tBuNH)2CO (see Figures S3–S5 in Supporting Information for further details). The urea byproduct derives from in situ hydrolysis of tBuNCO to afford tBuNH2 and CO2, followed by addition of tBuNH2 to another 1 equiv of tBuNCO (Scheme 4).

Figure 2.

Time courses of the oxidative imidoylation reaction under O2 (blue dashed lines) and under air (red solid lines). Reaction conditions: [N-methoxy-4-fluorobenzamide] = 101 mM, [tBuNC] = 153 mM, [Pd] = 5.0 mM (2.5 mol% Pd2(dba)3 · CHCl3), air or O2 balloon, Vtotal = 8.0 mL, dioxane, 65 °C. The dashed gray line represents the concentration of starting material.

Scheme 4.

Isonitrile Oxidation under Catalytic Conditions

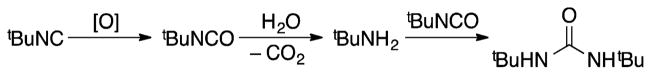

Measurement of the initial rates of reaction of N-methoxybenzamide and N-methoxybenzamide-d5 revealed a significant deuterium kinetic isotope effect: kH/kD = 6.7 (±0.2) (Figure 3). This result supports C–H cleavage as the turnover-limiting step of the catalytic reaction.

Figure 3.

Independent initial-rate measurements of the reactions of N-methoxybenzamide (red circles) or N-methoxybenzamide-d5 (blue squares). Conditions: 1.1 mM Pd2(dba)3 · CHCl3 (2.2 mol% [Pd]), 50 mM N-methoxybenzamide, 150 mM tBuNC, 1 atm air, dioxane, 60 °C.

Reactivity Studies of a Well-Defined PdII–Peroxo Complex

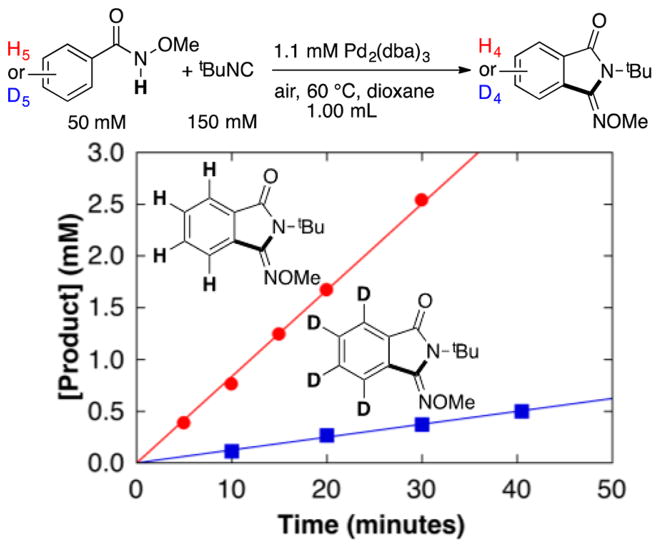

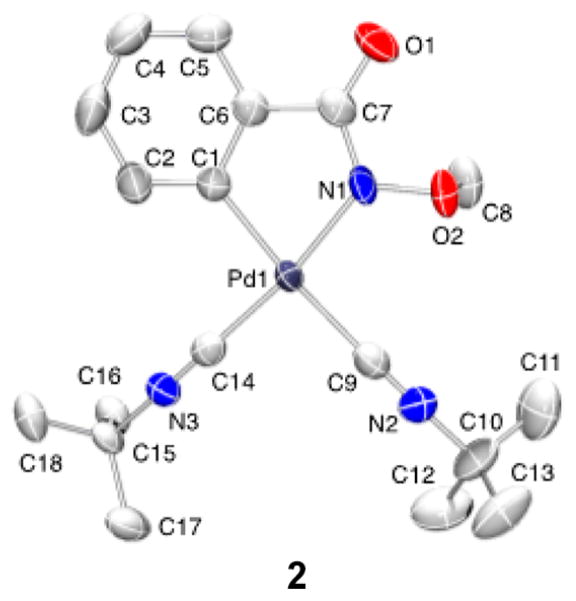

Palladium(II)–peroxo complexes have been invoked as key intermediates in Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions,13,14 and such species were proposed in a recent computational study of the present reaction by Wang and coworkers.9 In 1969, Otsuka and co-workers reported the bis(isonitrile)-ligated complex (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) (1),15 and this species is a plausible intermediate in the reaction. The peroxo compound 1 was prepared via addition of O2 to (tBuNC)2Pd0, as originally described by Otsuka.15 Subsequent treatment of 1 with 2 equiv of N-methoxybenzamide and tBuNC (2 equiv) in dioxane resulted in formation of the iminoisoindolinone product in 47% yield together with the cyclopalladation products 2–4 (46% total yield) and trace (tBuNH)2CO (Scheme 5).16 Complex 2 was isolated and characterized by X-ray crystallography (Figure 4). Testing of 2 as a precatalyst for the reaction revealed a 3 h induction period followed by slow formation of the iminoisoindolinone product (Figures S11 and S12). These observations demonstrate that 2 is not a kinetically competent intermediate in the catalytic reaction. Inclusion of more tBuNC (10 equiv), in an effort to more closely mimic catalytic conditions, resulted in a similar yield of the iminoisoindolinone (48%); however, much less cyclopalladation was observed (2 was the only cyclopalladation species detected and was formed in only 7% yield). This observation suggests that tBuNC inhibits cyclopalladation, presumably by occupying requisite coordinate site(s) and provides additional evidence that product formation does not proceed via such intermediates (see further discussion below).

Scheme 5.

Reaction of (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) 1 with N-Methoxybenzamide To Provide the Iminoisoindolinone Product and Several Cyclopalladated PdII Species

Figure 4.

Molecular drawing of (tBuNC)2Pd(C~N) 2. All atoms are shown as 90% thermal probability ellipsoids. All H atoms are omitted.

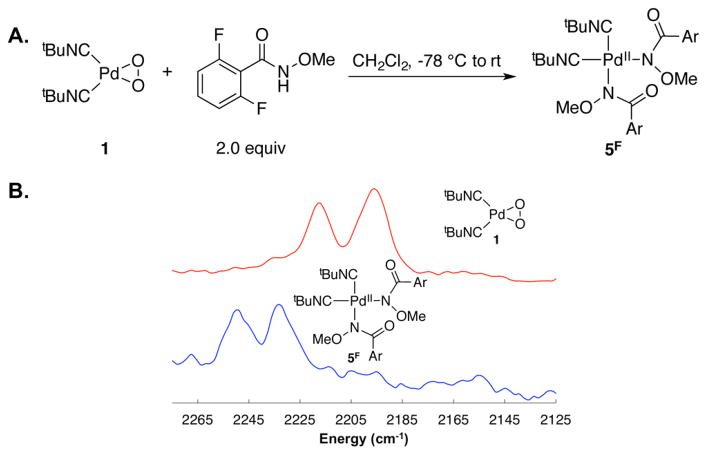

The PdII–peroxo compound 1 was then combined at low temperature with 2 equiv of N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide (HSubF2), an amide substrate that cannot undergo cyclo-palladation (Figure 5A), and the reaction was probed by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) FTIR spectroscopy. The IR spectrum of 1 exhibits two N≡C bands at 2217 and 2195 cm–1, corresponding to the symmetrical and unsymmetrical stretching modes (Figure 5A). The product also exhibits two bands, at 2249 and 2232 cm–1 (Figure 5A), consistent with formation of the bisamidate product cis-(tBuNC)2Pd(SubF2)2. Only one N≡C band would be expected for the corresponding trans product because the symmetrical stretch is IR-inactive in this species.17

Figure 5.

Stoichiometric reaction between (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) 1 and N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide to afford the cis-bisamidate-PdII product 5F (A) and in situ IR spectra of (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) 1 and the product of the stoichiometric reaction between (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) and N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide: cis-(tBuNC)2Pd(SubF2)2 5F (B). The scaling of the absorbance of the spectrum of 5F has been magnified by a factor of 3 to account for dilution relative to the sample used for the spectrum of 1.

Analysis of the Catalyst Resting State by X-ray Absorption and NMR Spectroscopy

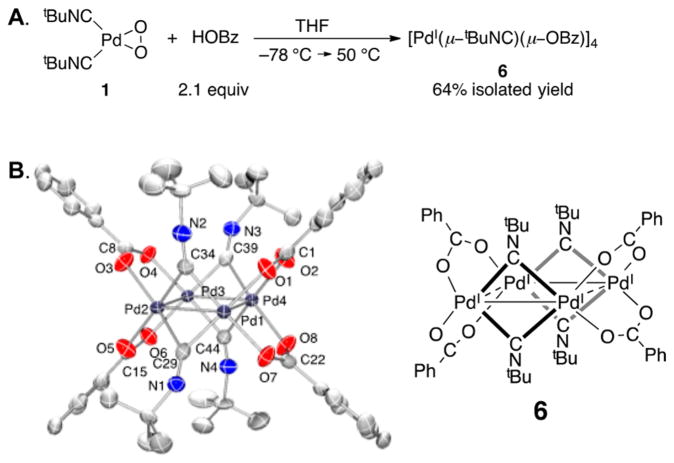

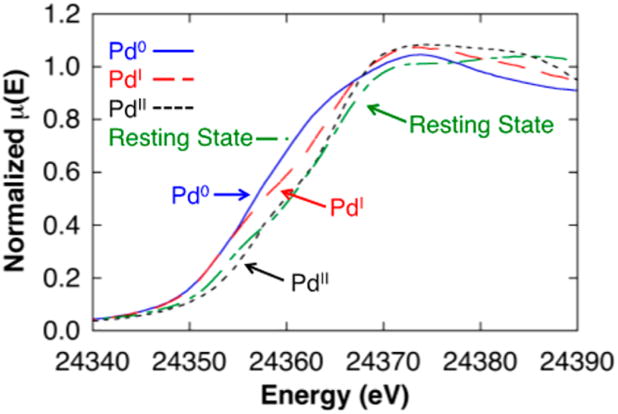

Both Pd0 and PdII compounds have been used as precatalysts for the present catalytic reactions (cf. Scheme 3B),4 and PdI complexes are commonly observed in reactions with isonitriles.18–20 For example, in the course of probing the reactivity of the PdII–peroxo compound 1 with carboxylic acids (in this case, benzoic acid), we observed formation of the tetrameric PdI compound [PdI(μ-tBuNC)( μ-OBz)]4 6 (Figure 6).21 These considerations raised questions about the oxidation state of the catalyst resting state during catalytic turnover. Attempts to address this issue by using in situ NMR methods were complicated by the complexity of the spectral data (see further discussion below). However, palladium K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy, which involves excitation of Pd 1s electrons, has been shown to be an effective qualitative means of probing the oxidation state for a systematic series of Pd complexes.22 The Pd K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra were obtained for a series of Pd0, PdI, and PdII reference compounds, Pd2(dba)3 · CHCl3, [PdI(μ-tBuNC)( μ-OBz)]4 (6), and Pd(TFA)2, and the data in Figure 7 show a progressive increase in the edge energy with increasing oxidation state. A temperature-controlled XAS cell, constructed from PEEK, was used to obtain XAS data during operation of the catalytic reaction (see Supporting Information for details). The resulting operando Pd K-edge spectrum closely aligns with the spectrum observed with the PdII reference and supports a PdII catalyst resting state during the reaction.

Figure 6.

(A) Tetrameric PdI compound 6 obtained from the reaction of PdII–peroxo 1 with benzoic acid. (B) Molecular drawing (left) and ChemDraw (right) of 6. All atoms are shown as 90% thermal probability ellipsoids. All H atoms are omitted.

Figure 7.

Palladium K-edge XANES spectra of Pd0 (Pd2(dba)3 CHCl3) (blue, solid), PdI ([PdI(μ-tBuNC)( μ-OBz)]4 6) (red, long dash), PdII (Pd(TFA)2) (black, short dash), and the catalyst resting state (green, long/short dash).

With these XANES data in hand, efforts were made to gain additional insights into the catalyst resting state by probing an active catalytic reaction by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopy using the 4-fluoro analogue of the substrate (HSub4F). Two sets of prominent peaks were evident in the spectra. Definitive assignment of the structures of these species was not possible; however, the spectral data closely resemble the spectra obtained from a stoichiometric reaction of the amide substrate HSub4F and tBuNC with the PdII–peroxo complex 1. The two species are tentatively assigned to bis-isonitrile Pd(amidinyl)(amidate) species on the basis of the spectroscopic data (eq 1; see Figures S20 and S21 and associated content in Supporting Information for further information).

|

(1) |

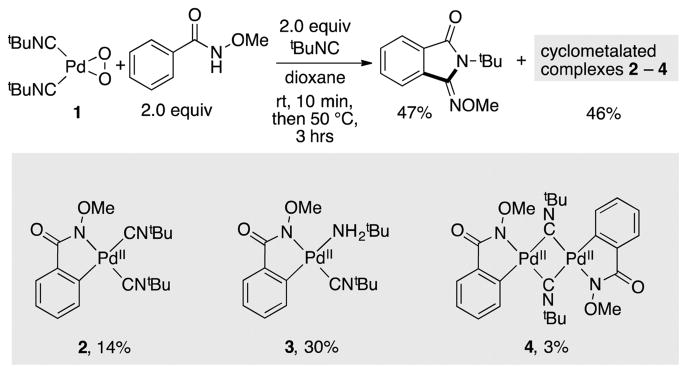

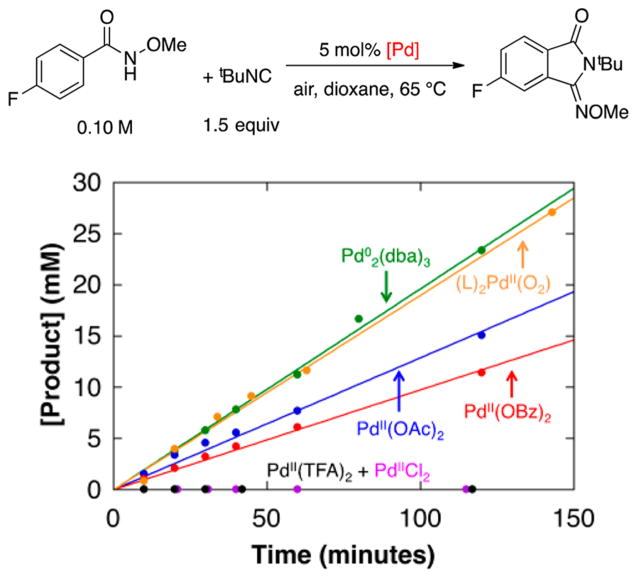

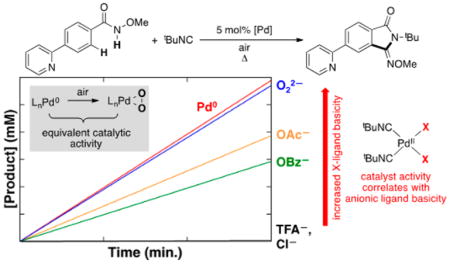

Comparison of Pd0 and PdII Precatalysts

The superiority of a Pd0 source [Pd2(dba)3] over Pd(OAc)2 as a precatalyst and the negligible reactivity with other PdII sources [e.g., PdCl2, Pd(TFA)2, Pd(OTf)2] are distinctive features of these reactions (cf. Scheme 3B). To probe the origin of these observations, we compared the initial rates of catalytic reactions with Pd2(dba)3 and several different PdII precatalysts (Figure 8). In addition to aforementioned PdII salts, we tested the PdII–peroxo complex 1. The data in Figure 8 show that 1 exhibits excellent reactivity, nearly identical to that of Pd2(dba)3, while the other PdII precatalysts react with a trend that matches the relative basicity of the anionic ligand: Pd(OAc)2 > Pd(OBz)2 > Pd(TFA)2 = PdCl2 = 0.

Figure 8.

Initial rates of the oxidative imidoylation of N-methoxy-4-fluorobenzamide under air using different Pd precatalysts. Reaction conditions: [N-methoxy-4-fluorobenzamide] = 101 mM, [tBuNC]tot = 153 mM, [Pd] = 5.0 mM, dioxane (8.0 mL), 65 °C. Specific conditions: (a) 2.5 mM Pd2(dba)3 · CHCl3; (b) 5.0 mM Pd(OAc)2; (c) 5.0 mM Pd(OBz)2; (d) 5.0 mM PdCl2; (e) 5.0 mM Pd(TFA)2; (f) 5.0 mM 1, 7.5 mM dba.

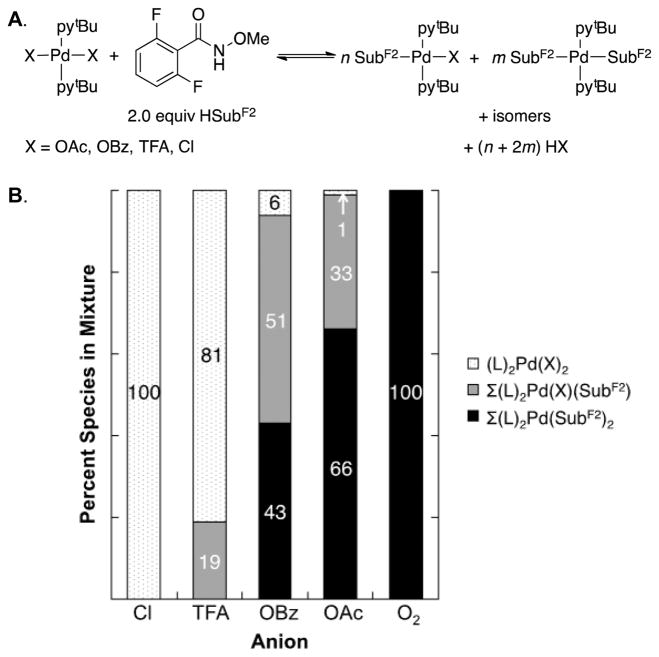

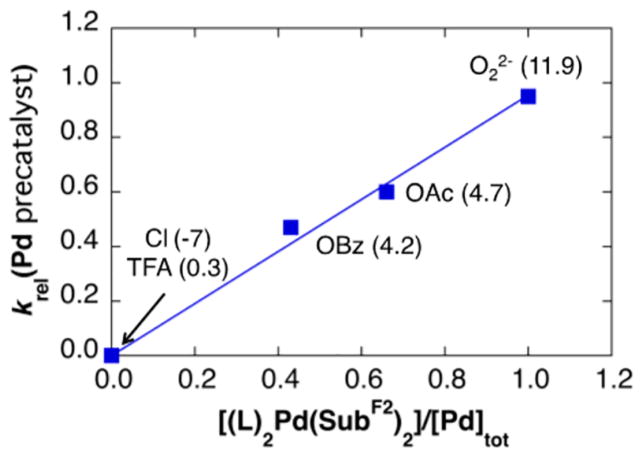

The data in Figure 8 are rationalized by substrate activation initiated by proton-coupled ligand exchange23 between the anionic ligand on the Pd catalyst and amide substrate. As shown in Figure 5, PdII–peroxo 1 reacts with N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide to generate the PdII–bisamidate species 5F. This ligand exchange reaction and the ensuing catalytic reaction is more favorable with more-basic anionic ligands. Direct observation of ligand effects on substrate activation was obtained by mixing trans-(tBupy)2PdIIX2 complexes (tBupy = 4-(tert-butyl)pyridine; X = OAc, OBz, TFA, or Cl) (Figure 9A) and 2 equiv of N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide in CDCl3 and analyzing the equilibrium mixture of products by 1H, 19F, 1H–15N HMBC, and 1D NOESY NMR spectroscopic methods.21 The product mixtures obtained from these studies, together with the reactivity of PdII–peroxo complex 1 with the same substrate, are presented in Figure 9B. No amidate complexes were observed in the mixture containing nonbasic chloride ligands, while monoamidate and bisamidate complexes are formed in increasing quantities as the basicity of the carboxylate increases from TFA to OBz to OAc. As noted in Figure 5, reaction of PdII–peroxo complex 1 with the amide substrate exclusively forms the bisamidate complex. As shown in Figure 10, the ability of anionic ligands to promote formation of the bisamidate PdII in Figure 9 directly correlates with the observed catalytic rates with different PdX2 precatalysts in Figure 8.

Figure 9.

(A) Reaction of (tBupy)2PdIIX2 species with N-methoxy-2,6- difluorobenzamide to afford (a mixture of) tBupy-ligated PdII–amidate species. (B) Distribution of PdII species observed in mixtures of (tBupy)2PdIIX2 and 2 equiv of N-methoxy-2,6-difluorobenzamide; the “O2” complex corresponds to PdII–peroxo complex 1.

Figure 10.

Initial rate of product formation with different PdII precatalysts PdIIX2 (cf. Figure 8) relative to that observed with Pd2(dba)3 plotted as a function of the equilibrium ratio of bisamidate species observed from the reaction of different PdX2 sources with HSubF2 in Figure 9. The number in parentheses corresponds to the aqueous pKa of the corresponding conjugate acid of the anionic ligand, with the exception of O22–, for which the pKa corresponds to that of H2O2. For reference, the aqueous pKa of the parent N- methoxybenzamide substrate is 8.9;24 the 2,6-difluoro analogue will be more acidic owing to the inductive effect of the fluoro substituents.

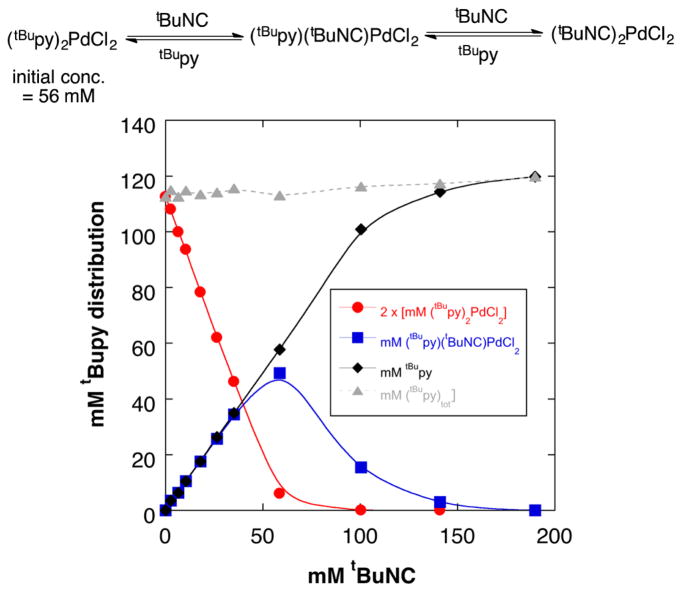

Comparison of the Relative Binding Affinities of Isonitrile and Pyridine

The binding affinity of tBuNC relative to tBupy (as a representative substrate heterocycle) was qualitatively evaluated via titration of tBuNC into a solution of trans-(tBupy)2PdCl2 in CDCl3 (Figure 11). Analysis of the different mixtures by 1H NMR spectroscopy shows sequential formation of trans-(tBupy)(tBuNC)PdCl2 and a mixture of cis-and trans-(tBuNC)2PdCl2. A clear preference for formation of the 1:1 Pd:tBuNC adduct is evident when <1 equiv of tBuNC is present, and the data further show that very little tBupy ligand is bound to Pd when ≥2 equiv of tBuNC is present. Collectively, these results show that isonitrile coordination is strongly favored over tBupy.25

Figure 11.

Plot of the tBupy speciation upon addition of tBuNC into a solution of trans-(tBupy)2PdCl2 in CDCl3 [initial concentration of (tBupy)2PdCl2 = 56 mM].

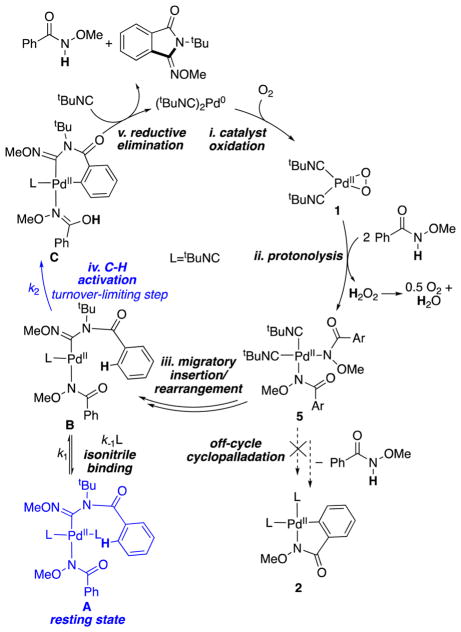

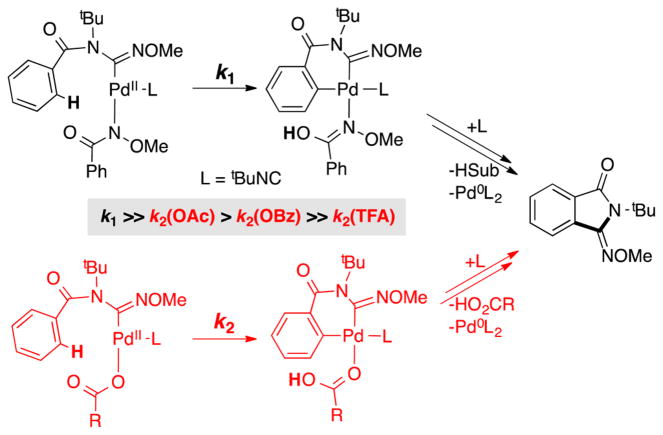

Proposed Catalytic Mechanism

The data presented above provide valuable insights into the mechanism of Pd-catalyzed C–H imidoylation (Scheme 6). Oxidation of a Pd0 precatalyst or intermediate by O2 in the presence of the isonitrile substrate is expected to afford (tBuNC)2Pd(O2) 1 (step i).15 Protonolysis of the Pd–O bonds in 1 by the N-methoxybenzamide substrate will afford cis -(tBuNC)2PdII(amidate)2 5 (step ii), according to the reactivity shown above (cf. Figure 5). tBuNC insertion into a Pd–N bond and 1,3-acyl migration (cf. Scheme 2) accounts for formation of the three-coordinate monoisonitrile PdII(amidinyl)(amidate) species B (step iii). B is believed to be an on-cycle intermediate, but it will react rapidly with tBuNC to form the four-coordinate bisisonitrile complex A, proposed to be the catalyst resting state.26 Dissociation of tBuNC from A to re-form B precedes turnover-limiting C–H activation of the substrate. The resulting cyclopalladated intermediate C (step iv) undergoes C–C reductive elimination (step v) to form the iminoisoindolinone product, together with release of 1 equiv of the substrate and regeneration of the (tBuNC)2Pd0 catalyst.

Scheme 6.

Proposed Mechanism for the Oxidative Imidoylation of N-Methoxybenzamide

Cyclopalladation of the substrate from the PdII(amidate)2 intermediate 5 to afford the off-cycle species 2 does not lead to productive catalytic turnover and is inhibited by tBuNC in the same manner that tBuNC inhibits productive catalytic turnover via formation of A from B. The off-cycle equilibrium between A and B/tBuNC and turnover-limiting C–H activation accounts for the kinetic data in Figures 1 and 2, which show that the catalytic rate law is first-order in [Pd], zero-order in [substrate], inverse first-order in [tBuNC] (cf. Figure 1C) and exhibits a large deuterium KIE (kH/kD = 6.7). C–H activation is expected to proceed via a concerted metalation–deprotonation (CMD) mechanism,27 in which case the N-methoxyamidate ligand in B will serve as the internal Brønsted base. The enhanced basicity of the amidate relative to typical carboxylates should promote this reaction.

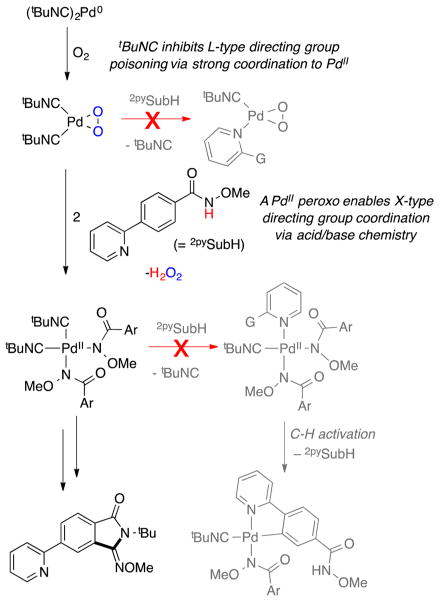

Heterocycle Tolerance, Directing Groups, and Anionic Ligand Effects

tBuNC is a better ligand for PdII than heterocycles such as tBupy (cf. Figure 11), and therefore L-type directing groups will be less effective in reactions of the type described here, which employ isonitriles as substrates.8a This inhibition of L-type ligand directing-group effects is complemented by factors that favor X-type ligand directing groups. The use of a Pd0 catalyst precursor results in the generation of a basic peroxide ligand that undergoes facile exchange with the amide substrate to generate the active PdII–bisamidate species. Carboxylate ligands are also able to promote this exchange, but their utility correlates with their basicity. None of the carboxylates is as effective as peroxide, owing to their lower basicity and inability to promote complete formation of the PdII–bisamidate species (cf. Figure 9). The lack of effectiveness of Pd(TFA)2 and PdCl2 as catalyst precursors reflects the (nearly) complete inability of TFA and chloride to engage the N-methoxybenzamide substrate in proton-coupled ligand exchange. The enhanced acidity of the N-methoxyamide substrate N–H group relative to traditional amides contributes to the effectiveness of this ligand exchange. These collective effects are illustrated in Scheme 7.

Scheme 7.

Effects That Contribute to Site Selectivity in N-Methoxybenzamide C–H Functionalization

The imidoylation reaction rates are directly proportional to the quantity of PdII–bisamidate species formed in the ligand exchange experiments (cf. Figures 8–10). This correlation appears to arise from a thermodynamic effect, in which a higher concentration of amidate-ligated PdII species will favor the reaction, but also a kinetic effect, in which the availability of a second basic amidate ligand will favor the CMD C–H activation step relative to a Pd species with a less basic carboxylate ligand (Scheme 8). The importance of anionic ligand basicity in promoting CMD-type C–H activation has been directly addressed in a number of recent studies,28 and amidate-mediated C–H activation has been the focus of considerable attention in recent Pd-catalyzed C–H oxidation reactions that feature monoprotected amino acid ligands.29,30

Scheme 8.

C–H Activation with (top) an Amidate Ligand or (bottom) a Carboxylate Ligand

CONCLUSIONS

This study of Pd-catalyzed oxidative imidoylation of N-methoxybenzamides to iminoisoindolinones established a clear mechanistic framework for these reactions. Kinetic and mechanistic studies showed that PdII-mediated C–H activation is the turnover-limiting step of the reaction. The reaction does not show a kinetic dependence of the O2 pressure, but elevated O2 pressure contributes to background decomposition of the isonitrile substrate, resulting in the reaction performing better under ambient air, rather than under 1 atm O2. Operando X-ray absorption spectroscopic data confirmed that the catalyst resting state is a PdII species, despite the presence of “soft” isonitrile ligands that commonly stabilize low-valent metal centers. Studies of stoichiometric reactions between the benzamide substrate and a well-defined PdII–peroxo complex and various PdII–carboxylate species provided valuable insights into the anionic ligand effects on the reaction.

The results highlight a number of factors that promote selectivity and activity in Pd-catalyzed aerobic C–H functionalization reactions. Anionic ligand effects, in particular, play a prominent role in these reactions. The PdII–peroxo species, generated as an intermediate during aerobic oxidation of the catalyst, can initiate substrate activation via proton-coupled ligand exchange between the peroxo group and the acidic N–H group of the N-methoxybenzamide. This step, in combination with strong ligand binding provided by isonitriles, accounts for the regioselectivity of C–H functionalization by promoting reactivity adjacent to the X-type directing group rather than L-type heterocycle directing groups and helps to prevent the formation of intermediates that lead to catalyst poisoning. The formation and kinetically beneficial role of a PdII–peroxo intermediate has important implications for other C–H functionalization reactions because the proton-coupled ligand exchange with other acidic functional groups could provide the basis for favorable reactions with diverse anionic nucleophiles and/or directing groups, while simultaneously helping to avoid poisoning by neutral heterocycles. PdII–carboxylate precatalysts are similarly capable of promoting proton-coupled ligand exchange, but the reduced basicity of carboxylates relative to the peroxo ligand results in competitive binding between the substrate-derived amidate and the carboxylate ligand. Although more-basic carboxylates are more effective, none is as effective as the PdII–peroxo. Use of a Pd0 precatalyst, such as Pd2(dba)3, provides a convenient means to generate the PdII–peroxo in situ. These insights provide a valuable foundation for efforts to discover new heterocycle-tolerant aerobic C–H oxidation reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for financial support from the NIH through an NRSA fellowship for S.J.T. (F32 GM119214). In addition, this project was initiated with financial support from the NIH (R01 GM67173) and completed with support from the NSF through the CCI Center for Selective C–H Functionalization (CHE-1205646). We thank Dr. Ilia A. Guzei and Kelsey Miles for X-ray crystallography work. Tracy Drier is thanked for designing and creating the two-well, two-necked flask used for the ReactIR studies. Dr. James Gerken and Dr. Guanghui Zhang are thanked for technical assistance with the synchrotron XAS experiments. Steve Myers and Dr. Jon Jaworski are thanked for designing and building the PEEK reactor cell and aluminum heating block for the operando XAS experiment. Prof. Joshua Wright (Argonne National Laboratory/Illinois Institute of Technology) is thanked for synchrotron beamline support at 10-ID-B. Prof. Jeffrey Miller (Purdue) is thanked for discussions regarding the setup of the synchrotron XAS experiments. Dr. Alastair Lennox is thanked for insightful discussions. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/jacs.7b07359.

Experimental details for syntheses of (new) compounds, data acquisition, additional kinetic and spectroscopic data, and crystallographic reports, including Figures S1–S86 and Tables S1–S12 (PDF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 2 (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 2A (CIF)

X-ray crystallographic data of 6 (CIF)

References

- 1.For selected reviews, see: Uchiumi S-i, Ataka K, Matsuzaki T. J Organomet Chem. 1999;576:279.Zapf A, Beller M. Top Catal. 2002;19:101.El Ali B, Alper H. In: In Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis. 2. Beller M, Bolm C, editors. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany: 2004. pp. 113–132.Torborg C, Beller M. Adv Synth Catal. 2009;351:3027.

- 2.For reviews of catalytic imidoylation, including C–H imidoylation, see: Vlaar T, Ruijter E, Maes BUW, Orru RVA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:7084. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300942.Lang S. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:4867. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60022j.Song B, Xu B. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:1103. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00384b.

- 3.For leading primary references, see the following: Wang Y, Wang H, Peng J, Zhu Q. Org Lett. 2011;13:4604. doi: 10.1021/ol201807n.Vlaar T, Cioc RC, Mampuys P, Maes BUW, Orru RVA, Ruijter E. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:13058. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207410.Wang Y, Zhu Q. Adv Synth Catal. 2012;354:1902. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201100831.Xu S, Huang X, Hong X, Xu B. Org Lett. 2012;14:4614. doi: 10.1021/ol302070t.Peng J, Zhao J, Hu Z, Liang D, Huang J, Zhu Q. Org Lett. 2012;14:4966. doi: 10.1021/ol302372p.Peng J, Liu L, Hu Z, Huang J, Zhu Q. Chem Commun. 2012;48:3772. doi: 10.1039/c2cc30351e.Vlaar T, Maes BUW, Ruijter E, Orru RVA. Chem Heterocycl Compd. 2013;49:902.Jiang H, Gao H, Liu B, Wu W. RSC Adv. 2014;4:17222.Zheng Q, Luo P, Lin Y, Chen W, Liu X, Zhang Y, Ding Q. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:4657. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00329f.Vidyacharan S, Murugan A, Sharada DS. J Org Chem. 2016;81:2837. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00048.

- 4.Liu YJ, Xu H, Kong WJ, Shang M, Dai HX, Yu JQ. Nature. 2014;515:389. doi: 10.1038/nature13885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang D, Cai S, Ben R, Zhou Y, Li X, Zhao J, Wei W, Qian Y. Synthesis. 2014;46:2045. [Google Scholar]

- 6.For a related oxidative carbonylation method for the preparation of phthalimide derivatives, see: Wrigglesworth JW, Cox B, Lloyd-Jones GC, Booker-Milburn KI. Org Lett. 2011;13:5326. doi: 10.1021/ol202187h.

- 7.For reviews of Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions, see: Stahl SS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3400. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630.Gligorich KM, Sigman MS. Chem Commun. 2009:3854. doi: 10.1039/b902868d.Campbell AN, Stahl SS. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:851. doi: 10.1021/ar2002045.Wang D, Weinstein AB, White PB, Stahl SS. Chem Rev. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00334.

- 8.For reviews about directed C–H functionalization, see: Ryabov AD. Chem Rev. 1990;90:403.Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e.For a review specifically focused on the N-methoxyamide directing group, see: Zhu RY, Farmer ME, Chen YQ, Yu JQ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:10578. doi: 10.1002/anie.201600791.

- 9.For a complementary DFT computational study of the same reactions, see: Dang Y, Deng X, Guo J, Song C, Hu W, Wang ZX. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:2712. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12112.

- 10.The substrate concentration regime in which inhibition was observed was not investigated in detail because this inhibitory behavior occurs beyond the substrate concentrations used in the originally reported synthetic method.

- 11.Hydrogen peroxide is believed to be formed as a byproduct of each catalytic turnover. Control experiments show that H2O2 undergoes rapid disproportionation under the catalytic reaction conditions, in addition to competitive oxidation of isonitrile. See section III.F. in Supporting Information and ref 12 for further details.

- 12.Numerous control experiments have been carried out to probe the basis for isonitrile oxidation (see section III.G. of Supporting Information). To summarize, neither O2 nor H2O2 promotes significant oxidation of isonitrile in the absence of Pd catalyst, but both oxidants promote rapid isonitrile oxidation in the presence of Pd. The latter oxidation reactions are considerably faster than the catalytic oxidative imidoylation reaction, implying that the presence of the amide substrate inhibits unwanted isonitrile oxidation during the catalytic reaction. The mechanistic basis for the pO2 dependence on isonitrile oxidation is not known, at present, but this observation implies that it does not involve the same Pd/O2 intermediate(s) involved in the productive catalytic imidoylation reaction.

- 13.For relevant reviews, see ref 7 and the following: Muzart J. Chem - Asian J. 2006;1:508. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600202.Scheuermann ML, Goldberg KI. Chem - Eur J. 2014;20:14556. doi: 10.1002/chem.201402599.

- 14.For fundamental studies and representative leading references, see: Stahl SS, Thorman JL, Nelson RC, Kozee MA. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7188. doi: 10.1021/ja015683c.ten Brink G-J, Arends IWCE, Sheldon RA. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:355.Konnick MM, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10212. doi: 10.1021/ja046884u.Adamo C, Amatore C, Ciofini I, Jutand A, Lakmini H. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6829. doi: 10.1021/ja0569959.Konnick MM, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5753. doi: 10.1021/ja7112504.Popp BV, Stahl SS. Chem - Eur J. 2009;15:2915. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802311.Ingram AJ, Walker KL, Zare RN, Waymouth RM. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13632. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08719.

- 15.Otsuka S, Nakamura A, Tatsuno Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1969;91:6994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.The complexes 2–4 were independently synthesized and characterized by NMR spectroscopy, and 2 was characterized by X-ray crystallography (see Supporting Information for details).

- 17.Otsuka S, Tatsuno Y, Ataka K. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:6705. [Google Scholar]

- 18.For representative examples of PdI/isonitrile crystal structures, see: Rettig MF, Kirk EA, Maitlis PM. J Organomet Chem. 1976;111:113.Rutherford NM, Olmstead MM, Balch AL. Inorg Chem. 1984;23:2833.Tanase T, Nomura T, Fukushima T, Yamamoto Y, Kobayashi K. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:4578.Burrows AD, Hill CM, Mingos DMP. J Organomet Chem. 1993;456:155.Vicente J, Abad J-A, Frankland AD, López-Serrano J, Ramírez de Arellano MC, Jones PG. Organometallics. 2002;21:272.

- 19.For catalytic applications of PdI precatalysts in carbonylation and imidoylation reactions, see: Tsukada N, Wada M, Takahashi N, Inoue Y. J Organomet Chem. 2009;694:1333.Ishii H, Ueda M, Takeuchi K, Asai M. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 1999;144:477.Ishii H, Goyal M, Ueda M, Takeuchi K, Asai M. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 1999;148:289.

- 20.For additional context, see refs 18c and 18d. For related reactivity, see the following: Moiseev II, Stromnova TA, Vargaftig MN, Mazo GJ, Kuz’mina LG, Struchkov YT. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1978;0:27.Stromnova TA, Vargaftik MN, Moiseev II. J Organomet Chem. 1983;252:113.Temkin ON, Bruk LG. Kinet Catal. 2003;44:601.Willcox D, Chappell BGN, Hogg KF, Calleja J, Smalley AP, Gaunt MJ. Science. 2016;354:851. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf9621.Hazari N, Hruszkewycz DP. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:2871. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00537j.Jaworski JN, McCann SD, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2017;56:3605. doi: 10.1002/anie.201700345.

- 21.See Supporting Information for details.

- 22.(a) Nelson RC, Miller JT. Catal Sci Technol. 2012;2:461. [Google Scholar]; (b) Duan H, Li M, Zhang G, Gallagher JR, Huang Z, Sun Y, Luo Z, Chen H, Miller JT, Zou R, Lei A, Zhao Y. ACS Catal. 2015;5:3752. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinhoff BA, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11268. doi: 10.1021/ja049962m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Exner O, Simon W. Collect Czech Chem Commun. 1965;30:4078. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The mixture of cis- and trans-(tBuNC)2PdCl2 species, together with the presence of broad NMR resonances, complicates more-precise determination of equilibrium constants.

- 26.It would seem plausible for intermediate A to undergo a second insertion of isonitrile into the remaining Pd–amidate bond to form a PdII bis(amidinyl) species, however, this reactivity was not apparent in our stoichiometric reactivity studies (cf. eq 1). As this process also would probably interfere with the subsequent C–H activation step, we conclude that this process either does not occur or that it is reversible.

- 27.For leading references, see: Davies DL, Donald SMA, Macgregor SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13754. doi: 10.1021/ja052047w.García-Cuadrado D, Braga AAC, Maseras F, Echavarren AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1066. doi: 10.1021/ja056165v.Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10848. doi: 10.1021/ja802533u.

- 28.(a) Izawa Y, Stahl SS. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352:3223. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201000771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Behn A, Zakzeski J, Head-Gordon M, Bell AT. J Mol Catal A: Chem. 2012;361–362:91. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang D, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5704. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.For a review including a discussion of different C–H activation transition states that have been proposed in MPAA/Pd catalysis, see: Engle KM. Pure Appl Chem. 2016;88:119.

- 30.For specific studies, see Cheng GJ, Yang YF, Liu P, Chen P, Sun TY, Li G, Zhang X, Houk KN, Yu JQ, Wu YD. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:894. doi: 10.1021/ja411683n.Musaev DG, Figg TM, Kaledin AL. Chem Soc Rev. 2014;43:5009. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60447k.Cheng GJ, Chen P, Sun TY, Zhang X, Yu JQ, Wu YD. Chem - Eur J. 2015;21:11180. doi: 10.1002/chem.201501123.Haines BE, Musaev DG. ACS Catal. 2015;5:830.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.