Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Many changes in the economy, policies related to nutrition, and food processing have occurred within the United States since 2000, and the net effect on dietary quality is not clear. These changes may have affected various socioeconomic groups differentially.

OBJECTIVE

To investigate trends in dietary quality from 1999 to 2010 in the US adult population and within socioeconomic subgroups.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

Nationally representative sample of 29 124 adults aged 20 to 85 years from the US 1999 to 2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

The Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010), an 11-dimension score (range, 0–10 for each component score and 0–110 for the total score), was used to measure dietary quality. A higher AHEI-2010 score indicated a more healthful diet.

RESULTS

The energy-adjusted mean of the AHEI-2010 increased from 39.9 in 1999 to 2000 to 46.8 in 2009 to 2010 (linear trend P < .001). Reduction in trans fat intake accounted for more than half of this improvement. The AHEI-2010 component score increased by 0.9 points for sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice (reflecting decreased consumption), 0.7 points for whole fruit, 0.5 points for whole grains, 0.5 points for polyunsaturated fatty acids, and 0.4 points for nuts and legumes over the 12-year period (all linear trend P < .001). Family income and education level were positively associated with total AHEI-2010, and the gap between low and high socioeconomic status widened over time, from 3.9 points in 1999 to 2000 to 7.8 points in 2009 to 2010 (interaction P = .01).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Although a steady improvement in AHEI-2010 was observed across the 12-year period, the overall dietary quality remains poor. Better dietary quality was associated with higher socioeconomic status, and the gap widened with time. Future efforts to improve nutrition should address these disparities.

Unhealthful diet is an important cause of many major noncommunicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and certain types of cancer, and ranks among the top contributors to the burden of disease and death in the United States.1 Therefore, adopting a healthful diet is an important strategy to prevent adverse health outcomes and optimize long-term health.2 Evaluation of population trends in dietary quality is essential because this provides feedback and guidance for public health policy. One approach to assess overall dietary quality is to calculate a score or index on the basis of aspects of diet related to health outcomes.3 For example, in 1996, Popkin et al4 used the Diet Quality Index to evaluate trends in a nationally representative US population and found significant improvements from 1965 to 1991. Since the late 1990s, many changes have occurred in the food supply, national economy, and policy environment, and scientific evidence and dietary recommendations have been continuously evolving. We therefore applied the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010), an 11-dimension dietary quality index, to investigate recent trends in dietary quality in the US adult population. The AHEI-2010 is based on a combination of food and nutrient variables that have established relationships with important health outcomes and has strongly predicted major chronic disease.5 We also performed a sensitivity analysis by applying the recently updated Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010), a measure of conformity to the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans,6 in the same study population.

Differences in dietary quality among socioeconomic subgroups contribute to disparities in the burden of noncommunicable diseases.7 Although striking diet-related disparities have been documented across different socioeconomic and racial subpopulations,8,9 data on time trends in dietary quality among these groups are minimal and have been limited by the use of individual food groups or nutrient intakes rather than overall diets.10,11

In this analysis, we used a nationally representative population to investigate trends in dietary quality from 1999 to 2010, as well as trends within socioeconomic subgroups.

Methods

Study Design and Population

We used the data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2000 through 2009 to 2010. The analytic population was nationally representative and consisted of 29 124 adults aged 20 to 85 years. The NHANES was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics research ethics review board. Details of study design and operation may be found elsewhere.12 Documented signed consent was obtained from participants.

Dietary Assessment

Dietary data were collected in the form of an interviewer-administered, computer-assisted 24-hour dietary recall. From 1999 to 2002, 1 24-hour dietary recall was collected in person from study participants; from 2003, a second recall was administered by telephone.13 Nutrient intake calculation was based on the nutrient databases of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA).14 Because the NHANES did not calculate data on trans fat, we used published estimates from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).15 The values for 1999 to 2000 (4.6 g/d) and 2009 to 2010 (1.3 g/d) were the mean consumption of industrially produced trans fat in the US population in the late 1990s and 2010. To impute data for each cycle of NHANES, we assumed a linear temporal change of trans fat consumption over time.

Socioeconomic Information

We categorized poverty income ratio (PIR) as less than 1.30, 1.30 to 3.49, and 3.50 or higher to reflect income level. Years of formal education were categorized as less than 12 years, completed 12 years, some college, and completed college. Age was categorized as 20 to 39, 40 to 59, and at least 60 years. Categorization of socioeconomic status (SES) was based on education and income level. Participants with more than 12 completed years of educational attainment and a PIR of at least 3.5 were categorized into high SES; participants with less than 12 years of educational attainment and a PIR less than 1.30 were categorized into low SES; and others were classified as medium SES. Race/ethnicity was classified as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanic, and other race/ethnicity categories. In this analysis, we collapsed other Hispanic and other race/ethnicity to create an other race/ethnicity group. Body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was categorized as less than 25.0, 25.0 to 29.9, 30.0 to 34.9, and at least 35.0.

AHEI-2010

The Alternate Healthy Eating Index was based on a review of the relevant literature and discussions among nutrition researchers to identify foods and nutrients that have been consistently associated with risk of chronic disease in clinical and epidemiologic investigations.5 Because the earlier Healthy Eating Index was not an adequate predictor of disease risk, the Alternate Healthy Eating Index was first developed in 2002 as an alternative. In 2010, it was updated (AHEI-2010) by incorporating the latest emerging evidence on diet and health. The Alternate Healthy Eating Index has been validated against major chronic disease risk,5,16 mortality,17 and biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial function.18

For this analysis, we modified food group assignments in the USDA’s MyPyramid Equivalents Database (MPED)19 to create the AHEI-2010 food groups, which include vegetables (excluding potatoes and juices), fruits (excluding juices), whole grains (including brown rice, popcorn, and any grain food with a carbohydrate-to-fiber ratio ≤10:1), sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juices, nuts and legumes, red and/or processed meat, and alcohol (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Foods directly corresponding to the MPED food group were given full weight; mixtures (eg, mixed dishes, soups) were given half weight to account for other constituents (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Additional details on food groupings can be found in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Nutrients included trans fat, long-chain (ω-3) fats (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and sodium. Nutrient contributions from dietary supplements were excluded. All AHEI-2010 components were scored from 0 to 10. For fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long-chain (ω-3) fats, and PUFAs, a higher score corresponded to higher intake. For trans fat, sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juices, red and/or processed meat, and sodium, a higher score corresponded to lower intake. For alcohol, we assigned the highest score to moderate, and the lowest score to heavy, alcohol consumers. Nondrinkers received a score of 2.5. The total AHEI-2010 ranged from 0 (nonadherence) to 110 (perfect adherence). The scoring method of the AHEI-2010 is described in Table 1 and our previous article.20

Table 1.

Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010) and Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010) Components and Criteria for Scoring

| AHEI-2010 | HEI-2010 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Maximum Score | Criteria | Maximum Score | Criteria | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| Score of 0 | Maximum Score | Score of 0 | Maximum Score | |||

| Total fruit | … | … | … | 5 | 0 | ≥0.8 cups/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Whole fruita | 10 | 0 | ≥4 servings/d | 5 | 0 | ≥0.4 cups/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Total vegetablesb | 10 | 0 | ≥2.5 cups/d | 5 | 0 | ≥1.1 cups/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Greens and beans | … | … | … | 5 | 0 | ≥0.2 cups/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Whole grainsc | 10 | 0 | Women: 75 g/d; Men: 90 g/d | 10 | 0 | ≥1.5 oz/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Dairy | 10 | 0 | ≥1.3 cups/1000 kcal | |||

|

| ||||||

| Sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice | 10 | ≥8 oz/d | 0 | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Nuts and legumes | 10 | 0 | ≥1 oz/d | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Red and/or processed meatsd | 10 | ≥1.5 servings/d | 0 | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Fatty acids | … | … | … | 10 | (PUFAs + MUFAs)/SFAs ≤1.2 | (PUFAs + MUFAs)/SFAs ≥2.5 |

|

| ||||||

| trans Fat | 10 | ≥4% of energy | ≤0.5% of energy | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Long-chain (ω-3) fats (EPA + DHA) | 10 | 0 | 250 mg/d | |||

|

| ||||||

| PUFAs | 10 | ≤2% of energy | ≥10% of energy | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol | 10 | Women: ≥2.5 drinks/d; Men: ≥3.5 drinks/d | Women: 0.5–1.5 drinks/d; Men: 0.5–2.0 drinks/d | … | … | … |

|

| ||||||

| Total protein foods | … | … | … | 5 | 0 | ≥2.5 oz/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Seafood and plant proteins | … | … | … | 5 | 0 | ≥0.8 oz/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Refined grains | … | … | … | 10 | ≥4.3 oz/1000 kcal | ≤1.8 oz/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Sodium | 10 | Highest decile | Lowest decile | 10 | ≥2.0 g/1000 kcal | ≤1.1 g/1000 kcal |

|

| ||||||

| Empty caloriese | … | … | … | 20 | ≥50% of energy | ≤19% of energy |

|

| ||||||

| Total | 110 | 100 | ||||

Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; ellipses, not applicable; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid.

Whole fruit excludes juice. For AHEI-2010, 1 serving is 1 medium piece of fruit or 0.5 cups of berries.

For AHEI-2010, total vegetables excludes potatoes and juices.

For AHEI-2010, whole grains include brown rice, popcorn, and any grain food with a carbohydrate to fiber ratio no more than 10:1.

For AHEI-2010, 1 serving is 4 oz of unprocessed meat or 1.5 oz of processed meat.

Calories from solid fats, alcohol, and added sugars; threshold for counting alcohol is more than 13 g/1000 kcal.

HEI-2010

In the sensitivity analysis, another dietary quality index, HEI-2010, was applied. The HEI-2010 consists of 12 components, including 9 adequacy components (total fruit; whole fruit; total vegetables; greens and beans; whole grains; dairy; total protein foods; seafood and plant protein; and fatty acids, which reflects the ratio of PUFAs and monounsaturated fatty acids to saturated fatty acids) and 3 moderation components (refined grains; sodium; and empty calories, which reflects a lower proportion of calories from solid fats, alcohol, and added sugars). Trans fat intake is not included in the HEI-2010. For the adequacy component, a higher score corresponded to higher intake. For the moderation component, a higher score corresponded to lower intake. The total HEI-2010 score ranged from 0 (nonadherence) to 100 (perfect adherence). The MPED 2.0 with the addendum from the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion was used for food grouping.21 The scoring method of the HEI-2010 is described in Table 1 and a previous publication.22

Statistical Analysis

All analyses incorporated the weights from the complex survey sample design to permit inference applicable to the non-institutionalized US population. Multivariate linear regression analysis was used to examine associations between independent and dependent variables and estimate adjusted mean AHEI-2010. Covariates for the models included total energy intake, sex, age group, PIR, education, race/ethnicity, and household size. The adjusted Wald F test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was used to test homogeneity of the AHEI-2010 across subgroups in each survey cycle. To examine the linear time trend in the AHEI-2010, the models included the midpoint of each survey time interval as a scored trend variable. We also examined nonlinearity of time trend by additionally including a quadratic term. To test the interactions between socioeconomic variables and time trend, we treated age group, PIR, education, and BMI as ordinal variables by using the median of each category and performed significance tests for the interaction terms. We treated race/ethnicity and SES as nominal variables and performed the adjusted Wald F test for the interaction terms with the time trend variable.23 In the sensitivity analysis, the same analyses were repeated for the HEI-2010 but without total energy adjustment because the HEI-2010 was generated using a density-based approach, ie, each component was calculated as per 1000 kcal or as a percentage of calories. All the analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute), or Stata, version 11.0 (StataCorp). All P values were 2-tailed (α = .05).

Results

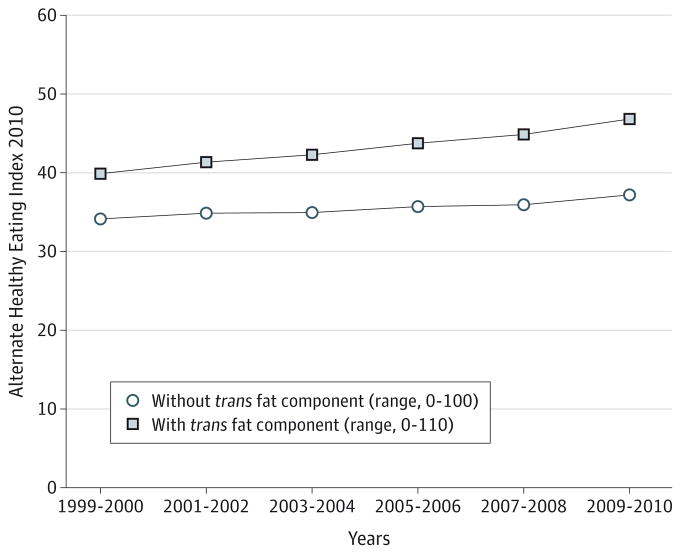

The energy-adjusted mean of the AHEI-2010 increased from 39.9 in 1999 to 2000 to 46.8 in 2009 to 2010. The energy-adjusted mean (95% CI) of the AHEI-2010 without the trans fat component increased from 34.2 (33.1–35.2) in 1999 to 2000 to 37.1 (36.6–37.7) in 2009 to 2010 with a significant time trend (linear trend P < .001) (Figure 1). The median (interquartile range) value of the AHEI-2010 without trans fat component increased from 33.2 (18.0) in 1999 to 2000 to 36.3 (19.1) in 2009 to 2010.

Figure 1. Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 Score Among Adults Aged 20 to 85 Years by National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Cycle.

Data are presented as energy-adjusted means.

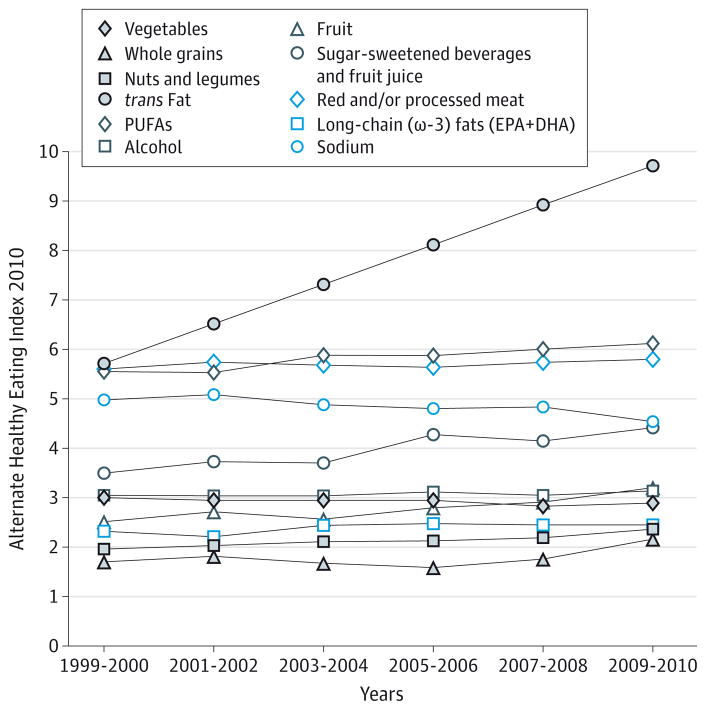

The AHEI-2010 component score increased by 0.9 points for sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice (reflecting decreased consumption), 0.7 points for whole fruit, 0.5 points for whole grains, 0.5 points for PUFAs, and 0.4 points for nuts and legumes over the 12-year period (all linear trend P < .001) (Figure 2). However, for sodium intake, a significant decrease of 0.5 points was seen (linear trend P < .001, reflecting greater intake). The reduction in trans fat consumption contributed more than half of the improvement in the overall AHEI-2010. Despite the increase in score, the AHEI-2010 scores for the vegetables, fruit, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long-chain (ω-3) fats, and alcohol components were relatively low (<4.0) across all survey periods.

Figure 2. Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 Component Score Among Adults Aged 20 to 85 Years by National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Cycle.

Data are presented as energy-adjusted means. For fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes, long-chain (ω-3) fats, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), a higher score corresponded to higher intake. For trans fat, sugar-sweetened beverages, red and/or processed meat, and sodium, a higher score corresponded to lower intake. For alcohol, we assigned the highest score to moderate, and the lowest score to heavy, alcohol consumers. Nondrinkers received a score of 2.5. DHA indicates docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; and PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid.

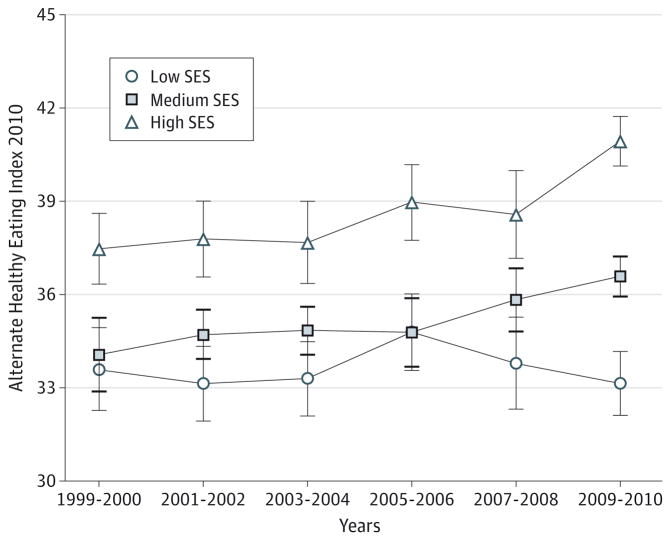

Table 2 shows significant improvements in AHEI-2010 in most socioeconomic subgroups. The increasing AHEI-2010 within the highest education and income levels indicated an accelerating improvement in recent years (quadratic term P = .03 for both groups) (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Table 2 also shows significant interactions between time trends and education (interaction P = .004), as well as time trend with income level (interaction P = .02). Dietary quality scores in the high-SES group, defined by both income and education, were consistently higher than in the lower-SES groups, and the improvement accelerated over time (Figure 3). In contrast, in the low-SES group, no significant temporal trend was observed (linear trend P = .99). The difference in AHEI-2010 between high-SES and low-SES groups significantly increased from 3.9 in 1999 to 2000 to 7.8 in 2009 to 2010 (interaction P = .01) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Covariate-Adjusted Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 Scores, Without the trans Fat Component, From National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999 to 2010

| Characteristic | No. | Score, Adjusted Mean (95% CI) | P Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| 1999–2000 | 2001–2002 | 2003–2004 | 2005–2006 | 2007–2008 | 2009–2010 | Linear Trenda | Interactionb | ||

| Sexc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Male | 13 969 | 34.0 (32.8–35.2) |

33.5 (32.7–34.4) |

34.3 (33.5–35.1) |

34.0 (33.0–35.1) |

34.5 (33.5–35.6) |

35.7 (34.9–36.6) |

.003 | .38 |

|

| |||||||||

| Female | 15 140 | 36.5 (35.5–37.5) |

37.3 (36.4–38.2) |

37.2 (36.4–38.0) |

38.1 (37.0–39.2) |

38.1 (37.1–39.0) |

39.0 (38.3–39.8) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for sex effectd | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Age, yc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| 20–39 | 10 171 | 31.0 (30.0–31.9) |

31.1 (30.1–32.1) |

32.1 (31.2–32.9) |

31.9 (30.3–33.4) |

31.9 (31.1–32.8) |

33.7 (32.8–34.6) |

<.001 | .09 |

|

| |||||||||

| 40–59 | 8983 | 35.2 (33.8–36.6) |

35.3 (34.4–36.1) |

34.7 (33.7–35.8) |

36.1 (34.8–37.4) |

36.1 (34.9–37.3) |

37.1 (36.3–37.8) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| 60–85 | 9955 | 39.4 (38.6–40.1) |

39.6 (38.7–40.5) |

40.2 (39.4–41.1) |

39.9 (38.9–40.9) |

40.7 (39.7–41.6) |

40.9 (40.0–41.8) |

.004 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for age effectd | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Educationc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| <12 y | 8864 | 34.2 (33.1–35.3) |

34.4 (33.4–35.4) |

34.5 (33.5–35.6) |

34.8 (33.8–35.8) |

35.2 (34.4–36.0) |

35.4 (34.4–36.5) |

.03 | .004 |

|

| |||||||||

| Completed 12 y | 6920 | 33.5 (32.0–35.1) |

34.1 (32.8–35.3) |

33.4 (32.4–34.5) |

34.2 (32.9–35.6) |

34.0 (32.9–35.1) |

34.4 (33.5–35.4) |

.26 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Some college | 7721 | 34.3 (33.3–35.3) |

34.7 (33.7–35.8) |

35.4 (34.4–36.4) |

36.0 (34.5–37.4) |

35.7 (34.4–37.1) |

36.6 (35.6–37.6) |

.003 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Completed college | 5559 | 37.7 (36.0–39.4) |

37.4 (35.8–38.9) |

38.3 (37.1–39.6) |

38.0 (36.7–39.4) |

39.2 (37.6–40.9) |

41.5 (40.4–42.5) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for education effecta | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Family PIRc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| <1.30 | 7613 | 35.2 (33.6–36.8) |

34.8 (33.0–36.7) |

35.5 (34.4–36.6) |

36.1 (34.8–37.3) |

35.7 (34.6–36.9) |

35.8 (35.0–36.7) |

.27 | .02 |

|

| |||||||||

| 1.30–3.49 | 10 386 | 34.6 (33.7–35.5) |

35.1 (34.3–35.9) |

35.8 (34.9–36.7) |

35.4 (34.3–36.6) |

36.8 (35.8–37.8) |

36.9 (36.0–37.8) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| ≥3.50 | 8508 | 35.7 (34.7–36.6) |

35.9 (34.9–37.0) |

35.7 (34.7–36.7) |

36.6 (35.4–37.8) |

36.2 (35.0–37.4) |

38.4 (37.4–39.4) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for PIR effectd | <.001 | <.001 | .02 | <.001 | .005 | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Race/ethnicityc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 14 374 | 34.1 (33.2–35.0) |

34.2 (33.4–35.0) |

34.5 (33.7–35.2) |

35.0 (33.9–36.1) |

35.0 (33.7–36.3) |

36.3 (35.6–37.0) |

<.001 | .22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 5717 | 33.5 (32.1–34.8) |

33.6 (32.5–34.8) |

32.8 (31.6–33.9) |

33.1 (32.1–34.0) |

33.9 (32.8–34.9) |

34.6 (33.5–35.6) |

.06 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Mexican American | 5922 | 35.7 (34.3–37.0) |

36.5 (36.3–36.6) |

36.2 (36.1–36.4) |

36.8 (36.6–37.0) |

37.3 (37.1–37.5) |

37.0 (36.8–37.2) |

.10 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Other | 3096 | 34.5 (32.6–36.5) |

35.0 (33.1–36.9) |

37.1 (35.6–38.5) |

36.4 (33.5–39.4) |

37.4 (35.7–39.2) |

38.0 (36.6–39.4) |

.002 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for race effectd | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| BMIc | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| <25.0 | 8616 | 35.2 (33.8–36.7) |

36.1 (35.1–37.1) |

36.2 (35.2–37.2) |

36.6 (35.3–37.8) |

36.9 (35.5–38.2) |

38.0 (36.8–39.2) |

.004 | .37 |

|

| |||||||||

| 25.0–29.9 | 10 001 | 35.7 (34.7–36.8) |

35.3 (34.4–36.3) |

36.2 (35.1–37.3) |

36.4 (35.2–37.7) |

36.2 (34.8–37.6) |

38.4 (37.5–39.2) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| 30.0–34.9 | 5773 | 34.0 (32.9–35.2) |

34.7 (33.4–36.0) |

34.3 (33.3–35.3) |

35.2 (34.1–36.3) |

35.7 (34.7–36.8) |

36.2 (35.5–36.9) |

<.001 | |

|

| |||||||||

| ≥35.0 | 4163 | 34.8 (33.4–36.1) |

33.5 (32.1–35.0) |

34.7 (33.1–36.2) |

34.5 (33.2–35.8) |

35.3 (34.3–36.4) |

35.2 (33.9–36.5) |

.16 | |

|

| |||||||||

| P value for BMI effectd | <.001 | .002 | .007 | .002 | .08 | <.001 | |||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); PIR, poverty income ratio.

Multivariate linear regression models include time trend as a single continuous term; the midpoint of each survey time interval was used as a scored trend variable; models are adjusted for total energy intake (continuous), sex (male, female), age group (20–39, 40–64, ≥65 y), PIR (<1.30, 1.30–3.49, ≥3.50), education (<12 y, completed 12 y, some college, completed college), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other), and household size, except for the variable of stratification.

P values for interaction between socioeconomic variables and scored trend variable in multivariate linear regression analyses adjusted for all covariates. Age group, education, and family PIR were treated as ordinal variables by using medium value of each category; interaction P was calculated from the Wald t test. Race/ethnicity was treated as a nominal variable; interaction P was calculated from the adjusted Wald F test.

Values are adjusted means (95% confidence interval) estimated by multivariate linear regression analysis, adjusted for the aforementioned covariates, except for the variable of stratification.

P values for homogeneity estimated by the adjusted Wald F test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons in multivariate linear regression analyses adjusted for the aforementioned covariates.

Figure 3. Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 Score Without the trans Fat Component According to Socioeconomic Status (SES) by National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Cycle.

Symbols indicate covariate-adjusted means, and error bars, 95% confidence intervals. Participants with more than 12 completed years of education attainment and a poverty income ratio of at least 3.5 were categorized as high SES; participants with less than 12 years educational attainment and a poverty income ratio of less than 1.30 were categorized as low SES; and others were classified as medium SES. Values were estimated from multivariate linear regression analysis by adjusting for total energy intake (continuous), sex (male, female), age group (20–39, 40–64, ≥65 y), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other), and household size.

Women had significantly higher mean AHEI-2010 than men, and a significant positive association between age and dietary quality was observed (Table 2). In each survey cycle, Mexican Americans had a significantly higher mean AHEI-2010 than non-Hispanic white and black groups, whereas non-Hispanic blacks had the lowest mean AHEI-2010. However, after adjustment for other socioeconomic covariates, the significant differences between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks disappeared in most of the survey cycles, whereas the differences between Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites remained significant across all survey cycles. Lower BMI category was associated with more dietary quality improvement. Among those with BMI less than 25, the AHEI-2010 increased by 2.8 points (P = .004), but among those with BMI of at least 35, the increase was only 0.4 points (P = .16) (Table 2).

In the sensitivity analysis, the mean (95% CI) HEI-2010 significantly increased from 46.6 (45.0–48.2) in 1999 to 2000 to 49.6 (48.9–50.4) in 2009 to 2010 (linear trend P < .001) (eTable 4 in the Supplement). The HEI-2010 component score increased by 1.5 points for empty calories, 0.7 points for whole grains, 0.4 points for whole fruit, 0.3 points for total fruit, 0.3 points for total protein foods, and 0.2 points for seafood and plant protein over time (all linear trend P < .001) (eTable 5 in the Supplement). A significant decrease of 0.9 points in the HEI-2010 score for sodium (reflecting greater intake) was also observed (linear trend P < .001) (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). eTable 6 in the Supplement shows significant improvements in HEI-2010 in most of the subgroups over time. Higher HEI-2010 scores were observed for female sex, older age, higher education and income levels, and lower BMI. Mexican Americans also had a higher HEI-2010 compared with non-Hispanic blacks and whites, whereas non-Hispanic blacks had the lowest HEI-2010. The difference of HEI-2010 between high-SES and low-SES groups increased from 5.7 in 1999 to 2000 to 7.3 in 2009 to 2010 (interaction P= .43) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

From 1999 to 2010, the quality of the US diet improved modestly overall. However, this improvement was greater among persons with higher SES and healthier BMI level; thus, disparities that existed in 1999 increased over the next decade. More than half of the gain in diet quality assessed by the AHEI-2010 was due to a large reduction in consumption of trans fat; the smaller increase in quality seen using the HEI-2010 was largely due to the fact that it did not incorporate this component. The dietary quality of the US population remains far from optimal, and there is huge room for further improvement, although only a small incremental gain can be made by further reducing intake of trans fats.

Our findings are consistent with an earlier report that nearly the entire US population fell short of meeting federal dietary recommendations.24 Previously, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study reported a decreasing secular trend in dietary quality from 1985 to 2006 after accounting for the aging effect, as well as closing gaps in dietary quality across different socioeconomic and racial subpopulations.25 However, this finding cannot be interpreted as a nationwide estimate because the study only included 5115 participants aged 18 to 30 years at baseline from 4 metropolitan areas.

Public policy change has played a central role in the large reduction in trans fat intake. Since 2006, the FDA has required trans fat to be included in nutrition labels because of strong evidence of adverse effects. Also, many states and cities have taken legislative and/or regulatory actions to limit trans fat use in restaurants and other locations.26 Most manufacturers have reformulated products to reduce trans fat content.27,28 Most recently, the FDA proposed taking final action to eliminate trans fat from the US food supply.29 The prominent reduction of trans fat content in processed and restaurant foods indicates that collective actions, such as legislation and taxation, that aim toward creating an environment that fosters and supports individuals’ healthful choices are more effective and efficient at reducing dietary risk factors than actions that solely depend on personal responsibility, such as consumers’ individual voluntary behavior change.30 Beyond the reductions in trans fat consumption, significant improvements in the AHEI-2010 for whole fruit, whole grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, nuts and legumes, and PUFAs also contributed to the overall improvement. These components have been addressed in many studies31–34 and dietary guidelines and by promotional campaigns by both governments and nongovernmental organizations.35–38 For example, the AHEI-2010 score for sugar-sweetened beverages increased from 3.5 to 4.4, which corresponds to a reduction from a mean of 36.4 to 31.4 oz/wk. Strong scientific evidence has associated sugar-sweetened beverage consumption with various adverse health outcomes, evoking public attention and policy initiatives.39 Recently, regulatory changes have occurred, including elimination of sales in schools and other public properties,40 and increases in taxes on these beverages are under consideration.39 However, we did not observe improvement on every AHEI-2010 component; intakes of vegetables (excluding potatoes), long-chain n-3 fatty acids, red and/or processed meat, and alcohol remained consistent over the 12-year period. The gradually increasing sodium intake is disconcerting, despite efforts to reduce this by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,6 as well as initiatives by the American Heart Association and other public health organizations.41

Time trends in dietary quality varied among population subgroups. Socioeconomic status was associated strongly with dietary quality, and the gaps in dietary quality between higher and lower SES widened over time. There are several potential explanations for the disparities across income levels. Price is a major determinant of food choice, and healthful foods generally cost more than unhealthful foods in the United States.42 Access to healthful foods also contributes to income-related disparities43,44; low-income households are less likely to own a car and thus may have limited access to supermarkets that sell healthful foods.43 Despite massive funding, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly the Food Stamp Program, for families with PIR of 1.30 or less has done little to address the income-related disparity in dietary quality.45,46(pp22–51) Large disparities in dietary quality also existed across education levels. Dietary quality was lowest and improved slowly in participants who had completed no more than 12 years of education, whereas dietary quality in participants who had completed college was consistently high and improved exponentially. Similar results were also found by Popkin et al47 from 1965 to 1996. Nutrition knowledge, which is strongly related to education level, is likely to play a role in adoption of healthful dietary habits, and better nutrition may be a lower priority for economically disadvantaged groups, who have many other pressing needs.48

Among race/ethnicity groups, Mexican Americans had the best dietary quality, whereas non-Hispanic blacks had the poorest dietary quality. Socioeconomic disparities and cultural differences are 2 potential mediators for the association between race/ethnicity and dietary quality.7,9,11 In our analysis, adjustment for income and education largely eliminated the differences between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks; however, the dietary quality among Mexican Americans remained significantly higher. These findings suggested that the differences between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks were more likely to be explained by socioeconomic inequity, whereas differences between non-Hispanic whites and Mexican Americans may be due to dietary traditions and culture. The minimal improvement in dietary quality in non-Hispanic blacks over time may be due in part to constrained access to healthful foods.7

Lower BMI was associated with more improvement in dietary quality over time, whereas the improvement in the highest-BMI group was negligible. Despite slightly lower energy intake49 and prevalence of physical inactivity50 in recent years, obesity prevalence still increased over the study period.51 Differences in improvement in dietary quality across BMI groups may offer some insights to explain this discrepancy, as the association between poor dietary quality and obesity has been reported previously.52,53

Limitations of our study should be considered. First, the methodology of the 24-hour dietary recall changed over the study period. A new 5-step recall with the USDA’s Automated Multiple-Pass Method was introduced in 2002; a second 24-hour recall was obtained via telephone starting in 2003; and the method of coding food items also changed as the nutrient databases were updated. Although these methodological differences may influence the accuracy of dietary information, the change in dietary quality that we observed was quite linear over time, suggesting that differences in methodology were not responsible for our findings. Second, recall bias has been associated with body weight status in dietary recall54 and may thus differ across different survey cycles. Since the NHANES 1999 to 2000, the prevalence of obesity and mean BMI among US adults have continued to increase,51 and the increase has been much greater in men than in women. However, the trends in dietary quality were similar for men and women, suggesting that obesity-related biases do not account for our findings. Third, because of the cross-sectional nature of the NHANES study design, we were unable to investigate a longitudinal effect of socioeconomic factors on dietary quality. Fourth, the lack of data on trans fat intake in the NHANES did not allow us to disaggregate intakes by population subgroups. However, reductions in trans fat intake have likely benefited low-SES groups at least as much as higher-SES groups because the major source was inexpensive processed and fast foods that are more commonly consumed by members of low-income groups. Last, improvement in the AHEI-2010 component score for trans fat could have been, in theory, achieved by increasing the total energy intake because of its energy-density–based scoring method. However, the total energy intake of the US population estimated from the NHANES data was quite stable over the study period and has even decreased slightly since 2003 to 2004.49

Conclusions

Our study suggests that the overall dietary quality of the US population steadily improved from 1999 through 2010. This improvement reflected favorable changes in both consumers’ food choices and food processing, especially the reduction of trans fat intake, that were likely motivated by both public policy and nutrition education. However, overall dietary quality remains poor, indicating room for improvement and presenting challenges for both public health researchers and policy makers. Furthermore, substantial differences in dietary quality were seen across levels of SES, and the gap between those with the highest and lowest levels increased over time. These findings suggest the need for additional actions to improve dietary quality, especially for those with low SES. Considering the elevated disease risk associated with poor dietary quality, dietary assessment and counseling in clinical settings deserves greater attention. Our previous study found that a 7.2-point increase in AHEI-2010 was associated with a 15% lower risk of major chronic disease in women5; this 7.2-point improvement could be readily translated into clinicians’ advice, eg, increasing whole fruit consumption by 3 servings per day or cutting back consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages from 1 or more per day to two 8-oz glasses per week, which could result in substantial reduction in disease burden. In addition to creating evidence to inform dietary recommendations and consumers’ practice, studies that focus on changing the food environment through collective actions, such as structural interventions and regulations, are imperative for sustainable dietary quality improvement; populations with low SES are likely to benefit most from the collective actions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Author Contributions: Drs Wang and Willett had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Ding, Hu, Willett.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Wang, Leung, Li, Chiuve, Hu, Willett.

Drafting of the manuscript: Wang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Wang, Leung, Li, Ding, Willett.

Obtained funding: Willett.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Chiuve, Hu.

Study supervision: Hu.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Abraham J, Ali MK, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–606. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Current evidence on healthy eating. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:77–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kant AK. Indexes of overall diet quality: a review. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96(8):785–791. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popkin BM, Siega-Riz AM, Haines PS. A comparison of dietary trends among racial and socioeconomic groups in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(10):716–720. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609053351006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rimm EB, et al. Alternative dietary indices both strongly predict risk of chronic disease. J Nutr. 2012;142(6):1009–1018. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.157222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. [Accessed August 16, 2013];US Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion website. 2010 http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DGAs2010-DGACReport.htm.

- 7.Satia JA. Diet-related disparities: understanding the problem and accelerating solutions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(4):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Income and race/ethnicity are associated with adherence to food-based dietary guidance among US adults and children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):624–635e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Chen X. How much of racial/ethnic disparities in dietary intakes, exercise, and weight status can be explained by nutrition- and health-related psychosocial factors and socioeconomic status among US adults? J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(12):1904–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Secular trends in the association of socio-economic position with self-reported dietary attributes and biomarkers in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1971–1975 to NHANES 1999–2002. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(2):158–167. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kant AK, Graubard BI, Kumanyika SK. Trends in black-white differentials in dietary intakes of U.S. adults, 1971–2002. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4):264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zipf G, Chiappa M, Porter KS, et al. Vital Health Stat. 56. Vol. 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [Accessed June 18, 2014]. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and Operations, 1999–2010. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_056.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):324–332. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Food Surveys Research Group. Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies. [Accessed June 18, 2014];US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service website. 2013 http://www.ars.usda.gov/Services/docs.htm?docid=12089.

- 15.Doell D, Folmer D, Lee H, Honigfort M, Carberry S. Updated estimate of trans fat intake by the US population. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2012;29(6):861–874. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2012.664570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belin RJ, Greenland P, Allison M, et al. Diet quality and the risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):49–57. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.011221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akbaraly TN, Ferrie JE, Berr C, et al. Alternative Healthy Eating Index and mortality over 18 y of follow-up: results from the Whitehall II cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(1):247–253. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fung TT, McCullough ML, Newby PK, et al. Diet-quality scores and plasma concentrations of markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):163–173. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowman SA, Friday JE, Moshfegh A Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center. MyPyramid Equivalents Database, 2.0 for USDA Survey Foods, 2003–2004. Beltsville, MD: US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung CW, Ding EL, Catalano PJ, Villamor E, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Dietary intake and dietary quality of low-income adults in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(5):977–988. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. [Accessed June 18, 2014];Healthy Eating Index 2010 Support Files—2007–2008. 2013 http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/HealthyEatingIndexSupportFiles0708.htm.

- 22.Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(4):569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korn EL, Graubard BI. Simultaneous testing of regression coefficients with complex survey data: use of Bonferroni t statistics. Am Stat. 1990;44(4):270–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW. Americans do not meet federal dietary recommendations. J Nutr. 2010;140(10):1832–1838. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sijtsma FP, Meyer KA, Steffen LM, et al. Longitudinal trends in diet and effects of sex, race, and education on dietary quality score change: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(3):580–586. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.020719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Conference of State Legislatures. [Accessed August 16, 2013];Trans Fat and Menu Labeling Legislation. 2013 http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/trans-fat-and-menu-labeling-legislation.aspx.

- 27.Dietz WH, Scanlon KS. Eliminating the use of partially hydrogenated oil in food production and preparation. JAMA. 2012;308(2):143–144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.7379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mozaffarian D, Jacobson MF, Greenstein JS. Food reformulations to reduce trans fatty acids. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(21):2037–2039. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1001841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed November 9, 2013];FDA Targets Trans Fat in Processed Foods. 2013 http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm372915.htm.

- 30.Brownell KD, Kersh R, Ludwig DS, et al. Personal responsibility and obesity: a constructive approach to a controversial issue. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(3):379–387. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hung HC, Joshipura KJ, Jiang R, et al. Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of major chronic disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(21):1577–1584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356–1364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonnalagadda SS, Harnack L, Liu RH, et al. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: health benefits associated with whole grains—summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 Satellite Symposium. J Nutr. 2011;141(5):1011S–1022S. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.132944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marquart L, Wiemer KL, Jones JM, Jacob B. Whole grains health claims in the USA and other efforts to increase whole-grain consumption. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(1):151–160. doi: 10.1079/pns2003242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foerster SB, Gregson J, Beall DL, et al. The California children’s 5 a day—power play! campaign: evaluation of a large-scale social marketing initiative. Fam Community Health. 1998;21(1):46–64. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Della LJ, Dejoy DM, Lance CE. Explaining fruit and vegetable intake using a consumer marketing tool. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(5):895–914. doi: 10.1177/1090198108322820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slavin J. Beverages and body weight: challenges in the evidence-based review process of the Carbohydrate Subcommittee from the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(suppl 2):S111–S120. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1599–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.An Order Relative to Healthy Beverage Options. [Accessed August 16, 2013];City of Boston website. 2011 http://www.cityofboston.gov/news/uploads/5742_40_7_25.pdf.

- 41.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Sacco RL, et al. Sodium, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease: further evidence supporting the American Heart Association sodium reduction recommendations. Circulation. 2012;126(24):2880–2889. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318279acbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernstein AM, Bloom DE, Rosner BA, Franz M, Willett WC. Relation of food cost to healthfulness of diet among US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1197–1203. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose D, Richards R. Food store access and household fruit and vegetable use among participants in the US Food Stamp Program. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(8):1081–1088. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morland K, Wing S, Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1761–1767. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leung CW, Hoffnagle EE, Lindsay AC, et al. A qualitative study of diverse experts’ views about barriers and strategies to improve the diets and health of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blumenthal SJHE, Willett W, Leung C, et al. SNAP to Health: A Fresh Approach to Strengthening the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Popkin BM, Zizza C, Siega-Riz AM. Who is leading the change? US dietary quality comparison between 1965 and 1996. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wardle J, Parmenter K, Waller J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite. 2000;34(3):269–275. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ford ES, Dietz WH. Trends in energy intake among adults in the United States: findings from NHANES. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):848–853. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.052662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson SA, Densmore D, Fulton JE, Yore MM, Kohl HW., III Differences in physical activity prevalence and trends from 3 US surveillance systems: NHIS, NHANES, and BRFSS. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(suppl 1):S18–S27. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.s1.s18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolongevicz DM, Zhu L, Pencina MJ, et al. Diet quality and obesity in women: the Framingham Nutrition Studies. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(8):1223–1229. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boggs DA, Rosenberg L, Rodríguez-Bernal CL, Palmer JR. Long-term diet quality is associated with lower obesity risk in young African American women with normal BMI at baseline. J Nutr. 2013;143(10):1636–1641. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.179002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johansson G, Wikman A, Ahrén A-M, Hallmans G, Johansson I. Underreporting of energy intake in repeated 24-hour recalls related to gender, age, weight status, day of interview, educational level, reported food intake, smoking habits and area of living. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4(4):919–927. doi: 10.1079/phn2001124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.