Abstract.

The genetic diversity of glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) R2 region in Plasmodium falciparum isolates collected before and 12 years after the introduction of artemisinin combination treatment of malaria in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria, was compared in this study. Blood samples were collected on filter paper in 2004 and 2015 from febrile children from ages 1–12 years. The R2 region of the GLURP gene was genotyped using nested polymerase chain reaction and by nucleotide sequencing. In all, 12 GLURP alleles were observed in a total of 199 samples collected in the two study years. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) marginally increased over the two study years; however, the differences were statistically insignificant (2004 samples MOI = 1.23 versus 2015 samples MOI = 1.47). Some alleles were stable in their prevalence, whereas two GLURP alleles, VIII and XI, showed considerable variability between both years. This variability was replicated when GLURP sequences from other regions were compared with ours. The expected heterozygosity (He) values (He = 0.87) were identical for the two groups. High variability in the rearrangement of the amino acid repeat units in the R2 region were observed, with the amino acid repeat sequence DKNEKGQHEIVEVEEILPE more prevalent in both years, compared with the two other repeat sequences observed in the study. The parasite population characterized in this study displayed extensive genetic diversity. The detailed genetic profile of the GLURP R2 region has the potential to help guide further epidemiological studies aimed toward the rational design of novel chemotherapies that are antagonistic toward malaria.

INTRODUCTION

Plasmodium falciparum malaria is still prevalent in many tropical countries and responsible for approximately 212 million clinical cases per year and about 429,000 deaths, mostly of children younger than 5 years and of pregnant women worldwide. The highest burden of malaria-related morbidity and mortality is observed in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Given the emergence and spread of drug-resistant P. falciparum in sub-Saharan Africa coupled with the development of insecticide-resistant mosquitoes and failure to develop effective malarial vaccines, global eradication of disease remains challenging.

Effective control and elimination requires integrated multilayered strategies, including the effective use of appropriate chemotherapies and vaccine development at the forefront.2

Efforts to develop a malaria vaccine have so far not yielded any commercially available product, with RTS, S-AS01 being the most advanced vaccine candidate.3,4 Another candidate under study is the GMZ2, which consists of conserved fragments of the glutamate-rich protein (GLURP27–500) and the merozoite surface protein 3 (MSP3212–380).5 GLURP is expressed during pre-erythrocytic and erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum’s development as well as on the surface of freshly released merozoites.6 The protein has been identified as an important antigen and it plays a role in the induction of protective immunity against P. falciparum through the stimulation of antibodies that mediates antibody-dependent cellular inhibition.7

The GLURP protein is composed of a rather conserved N-terminal non-repeat region covered by amino acids 27–500 (R0 region), a central repeat region with amino acids 500–705 (R1 fragment), and a C-terminal immunodominant repeat region consisting of amino acids 705–1,178 (R2 fragment).8 Several studies have shown the GLURP R0 region to be highly conserved and is able to stimulate a strong and stable antibody response.9–11 Studies have also shown that the GLURP R2 region possesses at least two B-cell epitopes and is able to stimulate antibodies capable of inhibiting parasites grown in vitro.7 Moreover, anti-GLURP R2 antibodies have also been shown to be associated with a reduced risk of clinical malaria in children from Ghana and Burkina Faso, and it has been suggested that the GLURP R2 domain might be used as a fusion vaccine antigen targeting malaria blood-stage parasites.12,13 A major concern, however, is the fact that the activity of a GLURP-based vaccine will be influenced greatly by the heterogeneity and genetic variability of the highly polymorphic R2 region. The main characteristic is the variable number of repeated nucleotides in the GLURP gene, which modifies the size of the gene and the encoded protein.14 Several studies have associated its allelic variability with geographical location and the intensity of malaria transmission.15–17 Genetic variation has been shown to contribute to reduced acquired immunity in P. falciparum as immunity is essentially strain-specific (Gandhi et al., 2014; Ocholla et al., 2014; Dechavanne et al., 2017).18–20 Information on the allelic heterogeneity of the R2 region of the GLURP gene over a period of time will be valuable for research and development of antimalarial vaccines.

In Nigeria, like in many other malaria-endemic countries, the first-line treatment of P. falciparum infection was changed from chloroquine to artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) in 2005. Changes in malaria intervention measures such as changes in drug and scale-up of insecticide-treated nets have been reported to have significant impact on malaria genetic diversity.21 If the interventions successfully reduce transmission, the malaria parasite will have fewer opportunities to sexually recombine, therefore, lowering population genetic diversity.22,23 In addition, factors such as inbreeding, epidemic population migration, geographic isolation, and gene flow or introgression of foreign parasites also contribute to P. falciparum population structure and diversity.24 The widespread use of ACT for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in the study area over a period of about 12 years is expected to bring about reduction in transmission rates and lower the genetic diversity of circulating P. falciparum. The goal of this study, therefore, was to systematically identify variability of P. falciparum GLURP genotypes occurring in samples collected before and 12 years after the introduction of ACT in southwest Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and sample collection.

This study was conducted in Osogbo, Osun State, in the southwestern part of Nigeria. Blood samples were collected from 270 febrile children (150 in 2004 and 120 in 2015), ages 1–12 years attending the Osun State Hospital, Osogbo. Blood films were stained with 10% Giemsa and examined microscopically for malaria parasites. Two drops of blood were blotted onto sterile Whatman 3MM filter paper (GE Healthcare Ltd., Princeton, NJ), from where genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAamp® DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 2004 samples (Group A) were collected during a chloroquine efficacy study,25 and DNA samples had been stored at −80°C at the Institute for Tropical Medicine in Tübingen, Germany. The 2015 samples (Group B) were retrieved from a study designed to evaluate commercially available rapid diagnostic tests in Nigeria. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Osun State Ministry of Health, Osogbo (OSHREC/PRS/569T/130). Before recruitment, informed signed or thumb-printed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the children.

Molecular genotyping.

The GLURP R2 region was amplified from P. falciparum samples using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methodology, as previously described.26 From P. falciparum–positive samples of Group A (N = 110) and Group B (N = 89), the amplified GLURP R2 region were analyzed following the recommended genotyping protocol.27 Primary and semi-nested PCR amplification reactions were carried out in 25 µL final volumes. The two reactions contained 1× PCR buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.4, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM of MgCl2), 0.125 mM of dNTPs, 0.25 mM of each primer (Table 1), and 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen). In the primary PCR, 2 µL of DNA template were added to the reaction mixture and 1 µL of the resulting PCR product was used subsequently as template in the semi-nested PCR.

Table 1.

Plasmodium falciparum–specific glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) primer pairs and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions used

| Gene | Amplification | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | G-F3 | 5′-ACATGCAAGTGTTGATCCTGAAG-3′ | |

| Glurp | G-F4* | 5′-TGTAGGTACCACGGGTTCTTGTGG-3′ | |

| Secondary | G-NF | 5′-TGTTCACACTGAACAATTAGATTTAGATCA-3′ | |

| Thermoprofile primary PCR | |||

| Initial denaturation | 95°C—5 minutes | 30 cycles | |

| Denaturation | 94°C—30 seconds | ||

| Annealing | 54°C—1 minute | ||

| Extension | 72°C—1 minute | ||

| Final extension | 72°C—5 minutes | ||

| Thermoprofile secondary PCR | |||

| Initial denaturation | 95°C—5 minutes | 30 cycles | |

| Denaturation | 94°C—30 seconds | ||

| Annealing | 59°C—1 minute | ||

| Extension | 72°C—1 minute | ||

| Final extension | 72°C—5 minutes | ||

This primer was also used as reverse primer in the secondary PCR amplification.

Allele detection and molecular weight estimation.

The semi-nested PCR products were separated using 1.5% Sybr Green I-stained agarose gels. Positive fragments were manually grouped into “bins” (bands on the gel image) differing by 50 base pairs (bp). Fragments falling within the limits of the bin were considered to represent the same genotype.28 Allele frequencies were computed as proportion of the total alleles detected among all positive samples analyzed. PCR reactions were performed in independent duplicates to exclude potential errors in scoring the alleles.

Multiplicity of infection (MOI) and allelic diversity.

The MOI, defined as the mean number of different P. falciparum strains infecting one individual, was determined by dividing the number of detected GLURP fragments by the number of PCR-positive samples. Isolates with more than one genotype were considered polyclonal infections, whereas the presence of a single allele was rated as a monoclonal infection. Genetic diversity, assessed by expected heterozygosity (He) and representing the probability of being infected by two parasites with different alleles at a given locus, was calculated using the formula He = [n/(n − 1)] [(1 − ∑Pi2)], where n = sample size and Pi = allele frequency.28 Quantitative data were represented as median and interquartile range (IQR).

Sequence analysis.

Alignment of nucleotide sequences and translation to reverse complementary sequences were carried out using the biological sequence alignment editor BioEdit (Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA). Comparisons of aligned nucleotide sequences were made with those available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI’s) GenBank database using the online Basic Local Alignment Search tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), with program selection optimized for highly similar sequences. Nucleotide sequences were translated using the online software Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy, https://www.expasy.org/). Amino acid sequences were compared with available sequences in the NCBI database (accession numbers: AAG12326, AAA50613, AAN28163, AAF18425–27, AIA99550–51, AIV43653–60) and also with sequences from other geographical locations to explore geographical patterns using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software (MEGA v.7.0.14, University Park, PA).29

Tests of neutrality.

Sequences of the randomly selected samples were aligned using the CLUSTALW program in MEGA and exported as a Fasta alignment for statistical analyses that include the tests of neutrality Tajima’s D, and Fu and Li’s F using DnaSP 6.10.01.30 The Tajima’s D test takes into consideration the difference between average pairwise nucleotide diversity between sequences (π) and Watterson’s population nucleotide diversity parameter theta (θ) expected under neutrality from the total number of segregating sites (S).31 Under neutrality, the two estimates π and θ are expected to be equal with D = 0. However, under balancing selection, the rare alleles have an advantage and the test gives a positive D value, and a negative D value in case of purifying selection. The Fu and Li’s D and F tests identify departures from neutrality as a deviation between estimates of θ, derived from the number of mutations in external branches of the phylogeny and from the total number of mutations (giving the index D), or from the average pairwise diversity (giving the index F). A deficit of mutations in external branches results in positive values of D and F, indicating unusual ancient alleles probably maintained by balancing selection.32

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and allelic diversity.

The proportion of males in the two groups was higher compared with that of females (58.2% [64/110] and 53.9% [48/89] in Groups A and B, respectively). The median age of participants in Group A was 35 months (IQR = 18–62) and in Group B was 84 months (IQR = 60–132). The mean temperature of patients was 37.8°C ± 1.1°C and 38.0°C ± 1.0°C in Group A and Group B, respectively. The geometric mean of parasitemia was 8,702 parasites/µL (confidence interval [CI] = 7,163–10,570) in Group A, whereas in Group B it was 8,955 parasites/µL (CI = 6,973–11,501). The median weight of study participants was 11 kg (IQR = 8–16) and 23 kg (IQR = 16–30) in Group A and B, respectively (Table 2). All differences were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients as enrolled in years 2004 and 2015

| Baseline characteristics | Group A_2004 (N = 110) | Group B_2015 (N = 89) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 0–36 months | 60 (55) | 10 (11) |

| 37–84 months | 31 (28) | 36 (40) |

| > 85 months | 19 (17) | 43 (53) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 46 (42) | 41 (46) |

| Female | 64 (58) | 48 (54) |

| Geometric mean (range), parasite/µL | 8,702 (7,163–10,570) | 8,955 (6,973–11,501) |

| Median weight, (IQR) kg | 11 (8–16) | 23 (16–30) |

| Mean temperature (°C) ± SD | 37.8 ± 1.1 | 38.0 ± 1.0 |

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

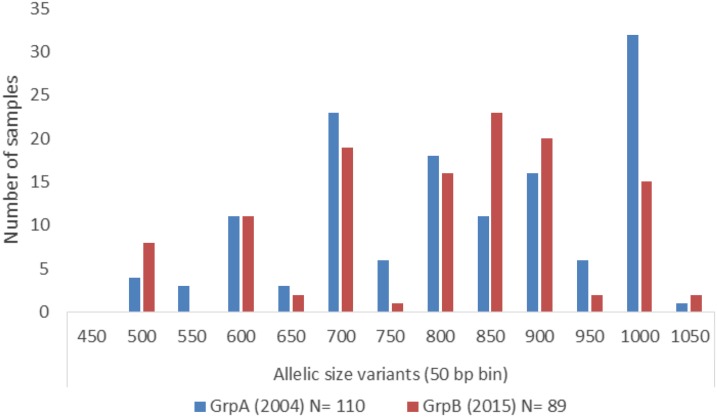

Altogether, 199 samples with P. falciparum infection, 110 of them collected in 2004 and 89 collected in 2015 were successfully used for GLURP genotyping. Twelve GLURP alleles with sizes ranging from 500 to 1,050 bp, grouped in bins of 50 bp, were observed and coded as genotypes I-XII (Table 3). All 12 genotypes were observed in Group A, with 11 occurring singly and 13 in combinations. For the Group B samples, 11 genotypes were observed of which seven occurred as a mono-genotype and 16 were observed in combinations. Genotype II was not identified at all in Group A or B. In Group A, 86 (78.2%), samples were infected with a single P. falciparum genotype, 23 (20.9%) with double, and one (0.9%) with triple P. falciparum genotypes. In Group B, a single P. falciparum genotype was found in 47 (52.8%) samples and double genotypes in 42 (47.2%) samples; no triple genotypes were observed. There was a significant variation in the frequency of genotypes XI between the two study years (P = 0.014) with group A showing the highest frequency (23.7%) of this genotype. Genotype V has a higher frequency in group A, whereas genotype VIII was predominant in Group B (18%); the differences were not significant. The frequencies of other genotypes were stable across the two groups. A considerable increase in the frequency of genotype VIII in Group B over Group A was observed, whereas a reduction of genotype XI in Group A was observed after 12 years (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Distribution of glutamate-rich protein R2 alleles in Plasmodium falciparum field isolates as observed in 2004 and 2015

| Types | Allele variants (50 bp bin) | 2004 (N = 110) n (%) | 2015 (N = 89) n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 500–550 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | NS |

| II | 550–600 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| III | 600–650 | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | NS |

| IV | 650–700 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| V | 700–750 | 11 (10) | 3 (3) | NS |

| VI | 750–800 | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | NS |

| VII | 800–850 | 11 (10) | 7 (8) | NS |

| VIII | 850–900 | 9 (8) | 16 (18) | NS |

| IX | 900–950 | 12 (11) | 9 (10) | NS |

| X | 950–1,000 | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | NS |

| XI | 1,000–1,050 | 26 (24) | 9 (10) | 0.014* |

| XII | 1,050–1,100 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | NS |

| I + III | 500–550 + 600–650 | 2 (2) | 5 (6) | NS |

| I + IV | 500–550 + 650–700 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | NS |

| I + VII | 500–550 + 800–850 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | NS |

| I + VIII | 500–550 + 850–900 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | NS |

| II + IV | 550–600 + 650–700 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| II + V | 550–600 + 700–750 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | NS |

| III + V | 600–650 + 700–750 | 5 (5) | 7 (8) | NS |

| III + VI | 600–650 + 750–800 | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | NS |

| IV + VII | 650–700 + 800–850 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| V + VII | 700–750 + 800–850 | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | NS |

| V + VIII | 700–750 + 850–900 | 2 (2) | 4 (5) | NS |

| V + XI | 700–750 + 1,000–1,050 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | NS |

| VI + VII | 750–800 + 800–850 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| VI + VIII | 750–800 + 850–900 | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | NS |

| VI + IX | 750–800 + 900–950 | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | NS |

| VII + VIII | 800–850 + 850–900 | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | NS |

| VII + XI | 800–850 + 1,000–1,050 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | NS |

| VIII + IX | 850–900 + 900–950 | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | NS |

| IX + X | 900–950 + 950–1,000 | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | NS |

| IX + XI | 900–950 + 1,000–1,050 | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | NS |

| X + XII | 950–1,000 + 1,050–1,100 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | NS |

| V + VII + IX | 700–750 + 800–850 + 900–950 | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | NS |

Significant P < 0.005; NS = not significant.

Figure 1.

Distribution of allelic size variants of Plasmodium falciparum glutamate-rich protein R2 repeat region in Group A isolates (collected in 2004) and Group B isolates (collected in 2015). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

The expected He rate He, used to estimate the fraction of parasites that would be heterozygous, was identical among both groups (He = 0.87). In addition, there was no significant variation in the MOI between Group A (MOI = 1.23) and Group B (MOI = 1.47).

Amino acid sequence diversity in the GLURP R2 region.

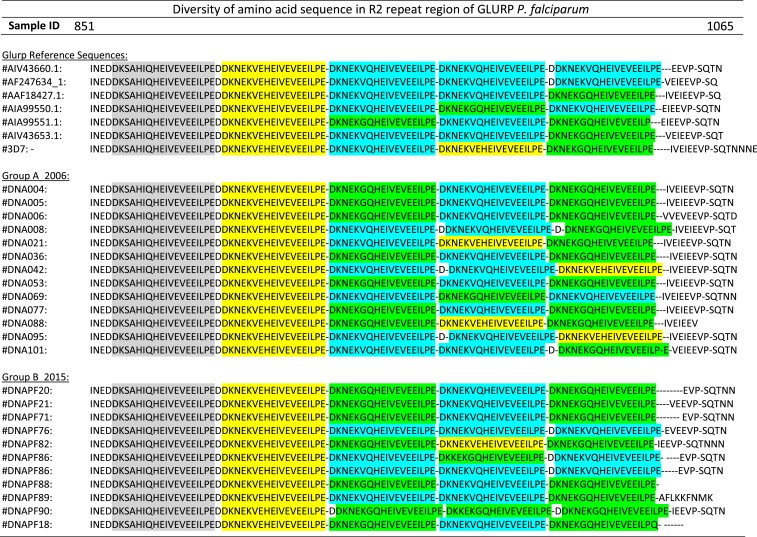

The GLURP R2 region of representative samples from both groups (Group A = 13 and Group B = 11 samples) was subjected to DNA sequencing. The amino acid repeat sequence unit (rsu) DKNEKGQHEIVEVEEILPE (rsu1) was most prevalent in both groups. In addition, two different rsu involving a substitution of the amino acid pairs GQ (glycine/glutamine) to VQ (valine/glutamine) (rsu2) and VE (valine/glutamic acid) (rsu3) at positions six and seven of the repeat were identified (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of amino acid repeat order of glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) R2 region of Plasmodium falciparum in field isolates and National Center for Biotechnology Information sequence database. Repeat sequence unit A (conserved): D K S A H I Q H E I V E V E E I L P E; Repeat sequence unit 1 (rsu1): D K N E K G Q H E I V E V E E I L P E; Repeat sequence unit 2 (rsu2): D K N E K V Q H E I V E V E E I L P E; and Repeat sequence unit 3 (rsu3): D K N E K V E H E I V E V E E I L P E. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

High variability in the rearrangement of the amino acid repeat units in the GLURP R2 region was found among the isolates in the two study years. A total of eight repeat rearrangements were observed (six in 2004 and five in 2015). The amino acid arrangement rsu3-rsu1-rsu2-rsu1 was the predominant arrangement in the two study years (46.2% in 2004 and 45.5% in 2015). The rsu3-rsu2-rsu3-rsu1 (7.7%), rsu3-rsu2-rsu2-rsu3 (15.4%), and rsu3-rsu1-rsu3-rsu1 (7.7%) were observed exclusively in the 2004 samples, whereas rsu3-rsu2-rsu2-rsu2 (27.3%) and rsu3-rsu1-rsu1-rsu1 (9.1%) were only observed in the 2015 samples (Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of glutamate-rich protein repetitive sequences observed in the study

| Sequence repeat order | 2004 N = 13 (%) | 2015 N = 11 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| rsu3 rsu1 rsu2 rsu1 | 6 (46) | 5 (46) |

| rsu3 rsu2 rsu2 rsu1 | 2 (15) | 1 (9) |

| rsu3 rsu2 rsu3 rsu1 | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| rsu3 rsu2 rsu2 rsu3 | 2 (15) | 0 (0) |

| rsu3 rsu2 rsu1 rsu2 | 1 (8) | 1 (9) |

| rsu3 rsu1 rsu3 rsu1 | 1 (8) | 0 (0) |

| rsu3 rsu2 rsu2 rsu2 | 0 (0) | 3 (27) |

| rsu3 rsu1 rsu1 rsu1 | 0 (0) | 1 (9) |

Repeat sequence unit 1 (rsu1): D K N E K G Q H E I V E V E E I L P E; repeat sequence unit 2 (rsu2): D K N E K V Q H E I V E V E E I L P E; and repeat sequence unit 3 (rsu3): D K N E K V E H E I V E V E E I L P E.

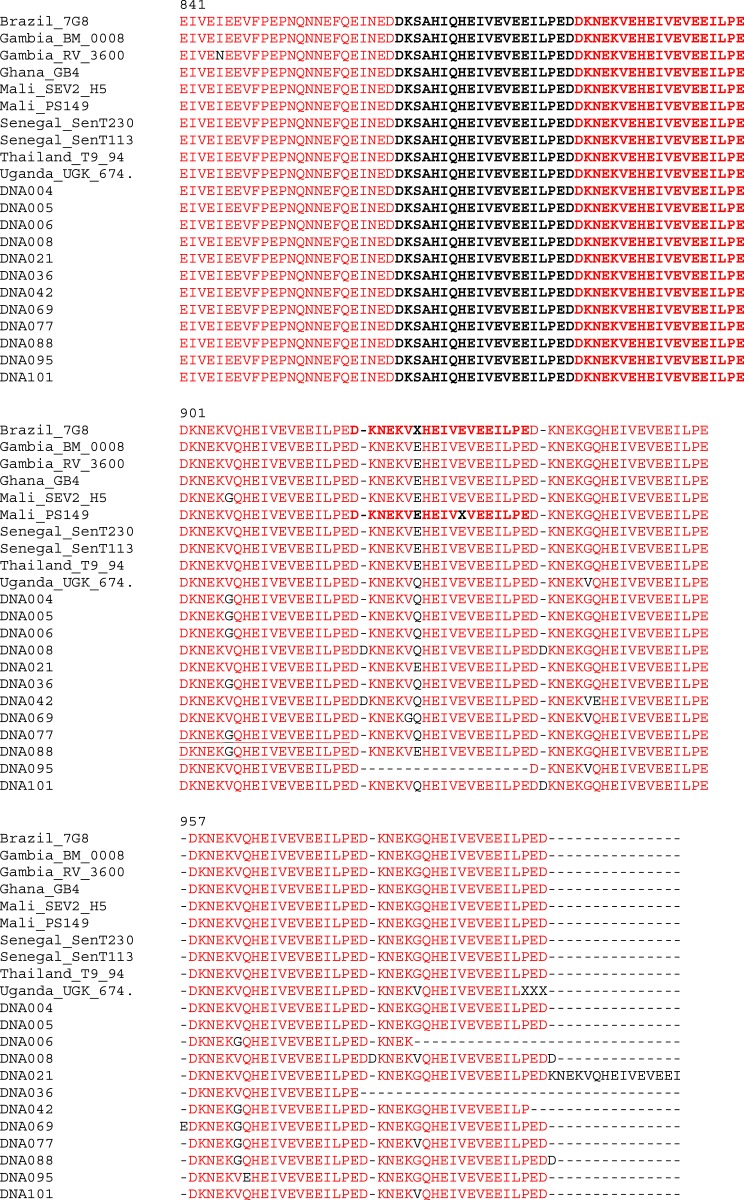

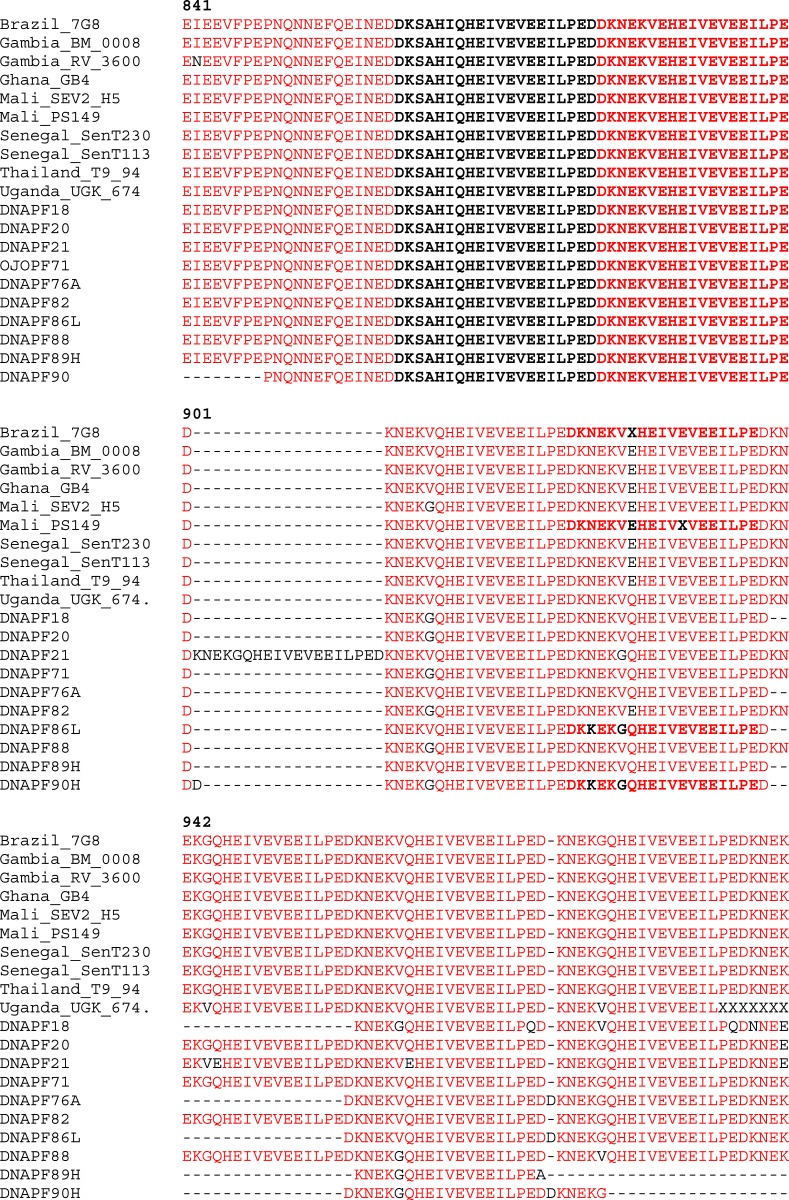

To explore the geographical pattern of our parasite populations, we compared our sequences with those from South America (Brazil), Asia (Thailand), and neighboring African countries (Gambia, Ghana, Mali, and Senegal). The sequences of P. falciparum isolates from these countries were retrieved from GenBank and the alignments with our Group A samples (collected in 2004) and Group B samples (collected in 2015) are shown in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. The rearrangement of the amino acid repeat units were identical in all the geographical areas between the amino acids 841 and 900 bp for both years (2004 and 2015), whereas extensive variability was observed in the amino acid rearrangement between 901 and 956 bp for 2004 isolates when compared with other geographical regions (Figure 3). Similar observation was made between 2015 samples in comparison with other isolates (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of alignment of amino acid repeat of glutamate-rich protein R2 region of 2004 Plasmodium falciparum field isolates and isolates from other parts of the world (retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information database). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Figure 4.

Comparison of alignment of amino acid repeat of glutamate-rich protein R2 region of 2015 Plasmodium falciparum field isolates and isolates from other parts of the world (retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information database). This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Table 5 shows the summary of statistics for the R2 region of GLURP and tests for departure from neutrality. For the execution of both the Tajima’s D test and Fu and Li’s D* and F* tests, the total number of mutations, instead of the number of segregating sites, was used to estimate θ because the latter takes into consideration the fact that there are sites segregating for more than two nucleotides. The analysis of neutrality tests conducted separately on samples collected in 2004 and 2015 yielded a significant negative value for Tajima’s D test, whereas the analysis for the combined samples from the two different years was also insignificant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of statistics for the R2 region of glutamate-rich protein and tests for departure from neutrality

| Year | No. of sequences | No. of sites | No of segregating sites | Nucleotide diversity Pi | Tajima’s D | SigD | FuLiD* | SigD* | FuLiF* | SigF* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 12 | 713 | 452 | 0.14646 | −1.9017 | * | −2.3419 | NS | −2.3288 | NS |

| 2015 | 10 | 644 | 400 | 0.16567 | −1.7509 | * | −1.8324 | NS | −1.8459 | NS |

| Both | 22 | 507 | 318 | 0.13586 | −1.3763 | NS | 1.1389 | NS | 0.4049 | NS |

FuLD* = Fu and Li’s D* test; FuLF* = Fu and Li’s F* test; SigD = significance of D (P value); SigD* = significance of D* (P value); SigF* = significance of F* (P value).

Significant result with P < 0.05, NS = not significant with P > 0.10.

DISCUSSION

The GLURP antigen is considered an important mediator of protective immunity and, consequently, an important vaccine candidate.33 However, the GLURP gene displays some antigenic diversity, with differing allelic variants, depending on geography and transmission intensity.34 A previous report originating from our study area has revealed extensive genetic diversity in the MSP2 gene.35 To expand our understanding of the genetic structure of P. falciparum and delineate potential contribution of ACT to malaria transmission intensity, we analyzed the parasite’s GLURP R2 diversity in field isolates collected 12 years since artemisinin-combination therapy was introduced for the treatment of clinical malaria in Nigeria.

Interventions leading to reduction in parasite transmission intensity are associated with overall reduction in parasite genetic diversity. Reduction in MOI and changes in genetic diversity, as well as reduction in recombination rates of parasite population are two major methods that currently serves to monitor changes in parasite population structure. In this study, we observed high genetic diversity and MOI in the two study years. Although not significant, there was a slight increase in the MOI in 2015 (MOI 2004: 1.23 versus MOI 2015: 1.47), implying that there seems to be no reduction in malaria transmission rates over this period, despite the introduction of new intervention methods. Nevertheless, it has been observed that the relationship between MOI and transmission intensity is not linear as it can be greatly influenced by the level of endemicity.36 To this end, evaluating other P. falciparum genes such as MSP, circumsporozoite proteins (CSP), apical membrane antigen 1, and drug-resistant genes may be necessary to further validate this observation.

The occurrence of these mixed genotypes are probably maintained by the large size of the parasite population.37 The high number of GLURP alleles (12 in Group A, 11 in Group B) is expected in an area of high malaria endemicity, and this is in agreement with previous reports from Asia, and most especially from Africa where 8–20 GLURP alleles have been reported.28,38 On the contrary, in low malaria endemic countries such as Honduras, French Guyana, Brazil, and Colombia, low number of alleles ranging from two to five alleles were reported. The fact that high number of alleles were recorded in both study years in our study further corroborate that malaria transmission remains high.

Although the prevalence of most of the alleles appeared to be stable over the 12-year interval, genotype VIII showed a 2.6-fold increase of its frequency from 2004 (Group A: 8.1%) to 2015 (Group B: 18%). On the other hand, there was a 2-fold reduction in the prevalence of genotype XI from 2004 (Group A: 24%) to 2015 (Group B: 10%). There was a marginal decrease in allele sizes from 2004 to 2015, most likely as a result of anti-vectorial measures which may exert selective pressure on distinct alleles.39 The observation of a considerable number of different GLURP genotypes in our study demonstrates its extensive diversity, with our finding being in agreement with previous studies which correlated genetic diversity with disease transmission intensity.34,40,41 Malaria parasites use their extensive genetic diversity to their advantage as variability confers the ability to evade human immune responses, compromising vaccine efficacy and that of antimalarial drugs.

Although the GLURP R2 region is extensively diverse as revealed by the number of allele sizes, the amino acid rsu DKNEKGQHEIVEVEEILPE was rather well conserved among the field isolates in both years. The observed arrangement was similar to a previous report which showed the amino acids GQ (rsu1) in the sixth and seventh position, replaced by VE (rsu2) and VQ (rsu3).6 However, sequence arrangements largely differed across the 2 years. The observed number of repeat sequences was less than the 12 reported recently from India.38 The order of the amino acids in Group B was almost similar to that observed in the NCBI sequences, suggesting sequence homology to parasites from other parts of the world. The study showed some differences in the arrangements of parasite DNA sequences in the two study years, indicating possible responses of the parasite to changes in antimalarial treatment from chloroquine to ACT. The changes in the genetic makeup of drug-resistant genes of P. falciparum has been attributed to drug pressure following the change of the treatment policy as reported in countries such as Cameroon,42 Grande Comore island,43 and Malawi44 after withdrawal of chloroquine, and this can have significant impact on the allelic diversity of the circulating parasite. The comparison of the amino acid sequences of our study area with other sequences from other geographical areas of the world revealed extensive diversity within the amino acid 901–957. The repeat sequence rsu3 was more frequent in other geographical areas compared with Nigeria suggesting that the sequences are heterogenous. This significant heterogeneity has implication on P. falciparum vaccine efficacy. The previous study provides an insight on the existing polymorphisms in the CSP gene of parasite population from India that could potentially influence the efficacy of RTS,S vaccine within the Indian population in this region.45

The neutrality test analysis further provides information about the genetic variation of the GLURP gene between the 2 years under study. The Tajima’s D test analysis conducted separately on samples collected in 2006 and 2015 yielded a significant negative value suggesting that the parasite populations at these times might have undergone a selective sweep or population growth with the occurrence of an excess of mutations at low frequency. According to Tajima (1989), a negative value is an indication of possible balancing selection, whereas positive value is suggestive of recent directional selection or background selection of slightly deleterious alleles. The study, therefore, shows balancing selection within the two study years, potentially an indication of excess internal mutations of low frequency, maintained over the 12 years.

This study has generated substantial data to understand the frequency and the distribution of naturally evolved genetic polymorphisms affecting amino acid sequences in the GLURP R2 repeat region, comparing two point samples collected 12 years apart in Nigeria. Taken together, the GLURP R2 region remains genetically diverse among field isolates from Osogbo, Nigeria, 12 years post-introduction of ACT. A change in the amino acid arrangement was observed, which most likely resulted from the impact of changes in malaria intervention measures. Genetic drift and decrease in the level of He and MOI has been attributed to the scale up of interventions, such as the insecticide-treated bed nets, indoor residual, spray, and the introduction of new antimalarial drug regimens. Also large gametocyte reservoir leading to ingestion of multiple clone parasites that increases the level of outbreeding have all contributed to genetic changes observed in P. falciparum in high transmission regions of Africa.24 Assessing the variability of immunogenic parasite genes is important in designing field trials of vaccine candidates or drugs. Molecular surveillance of this sort are very important in sub-Saharan Africa, to monitor the current status of circulating parasite populations and the potential impact of new intervention or control measures, based on local epidemiological factors.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to Mr. Adeola Ayileka for his support during field sampling. We acknowledge the health staff of the State Hospital and Primary health care Centre Sabo, Osogbo.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO , 2016. World Malaria Report 2016, 148 Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2016/report/en/. Accessed July 7, 2017.

- 2.Ojurongbe O, Akindele A, Adedokun S, Thomas B, 2016. Malaria: control, elimination, and eradication. Hum Parasit Dis 8: 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kana IH, Adu B, Tiendrebeogo RW, Singh SK, Dodoo D, Theisen M, 2017. Naturally acquired antibodies target the glutamate-rich protein on intact merozoites and predict protection against febrile malaria. J Infect Dis 215: 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agnandji ST, et al. ; RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership , 2012. A phase 3 trial of RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine in African infants. N Engl J Med 367: 2284–2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theisen M, Soe S, Brunstedt K, Follmann F, Bredmose L, Israelsen H, Madsen SM, Druilhe P, 2004. A Plasmodium falciparum GLURP-MSP3 chimeric protein; expression in Lactococcus lactis, immunogenicity and induction of biologically active antibodies. Vaccine 22: 1188–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borre MB, Dziegiel M, Høgh B, Petersen E, Rieneck K, Riley E, Meis JF, Aikawa M, Nakamura K, Harada M, 1991. Primary structure and localization of a conserved immunogenic Plasmodium falciparum glutamate rich protein (GLURP) expressed in both the preerythrocytic and erythrocytic stages of the vertebrate life cycle. Mol Biochem Parasitol 49: 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theisen M, Soe S, Oeuvray C, Thomas AW, Vuust J, Danielsen S, Jepsen S, Druilhe P, 1998. The glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) of Plasmodium falciparum is a target for antibody-dependent monocyte-mediated inhibition of parasite growth in vitro. Infect Immun 66: 11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theisen M, Vuust J, Gottschau A, Jepsen S, Høgh B, 1995. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of recombinant glutamate-rich protein of Plasmodium falciparum expressed in Escherichia coli. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2: 30–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodoo D, Theisen M, Kurtzhals JA, Akanmori BD, Koram KA, Jepsen S, Nkrumah FK, Theander TG, Hviid L, 2000. Naturally acquired antibodies to the glutamate-rich protein are associated with protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis 181: 1202–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mamo H, Esen M, Ajua A, Theisen M, Mordmüller B, Petros B, 2013. Humoral immune response to Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidate GMZ2 and its components in populations naturally exposed to seasonal malaria in Ethiopia. Malar J 12: 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Theisen M, et al. , 2001. Selection of glutamate-rich protein long synthetic peptides for vaccine development: antigenicity and relationship with clinical protection and immunogenicity. Infect Immun 69: 5223–5229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adu B, et al. , 2016. Antibody levels against GLURP R2, MSP1 block 2 hybrid and AS202.11 and the risk of malaria in children living in hyperendemic (Burkina Faso) and hypo-endemic (Ghana) areas. Malar J 15: 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meraldi V, Nebié I, Tiono AB, Diallo D, Sanogo E, Theisen M, Druilhe P, Corradin G, Moret R, Sirima BS, 2004. Natural antibody response to Plasmodium falciparum Exp-1, MSP-3 and GLURP long synthetic peptides and association with protection. Parasite Immunol 26: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt-Riccio LR, Perce-da-Silva Dde S, Lima-Junior JC, Theisen M, Santos F, Daniel-Ribeiro CT, de Oliveira-Ferreira J, Banic DM, 2013. Genetic polymorphisms in the glutamate-rich protein of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from a malaria-endemic area of Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 108: 523–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A-Elbasit IE, A-Elgadir TME, Elghazali G, Elbashir MI, Giha HA, 2007. Genetic fingerprints of parasites causing severe malaria in a setting of low transmission in Sudan. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 13: 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mlambo G, Sullivan D, Mutambu SL, Soko W, Mbedzi J, Chivenga J, Jaenisch T, Gemperli A, Kumar N, 2007. Analysis of genetic polymorphism in select vaccine candidate antigens and microsatellite loci in Plasmodium falciparum from endemic areas at varying altitudes. Acta Trop 102: 201–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montoya L, Maestre A, Carmona J, Lopes D, Do Rosario V, Blair S, 2003. Plasmodium falciparum: diversity studies of isolates from two Colombian regions with different endemicity. Exp Parasitol 104: 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi K, Thera MA, Coulibaly D, Traoré K, Guindo AB, Ouattara A, Takala-Harrison S, Berry AA, Doumbo OK, Plowe CV, 2014. Variation in the circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium falciparum: vaccine development implications. PLoS ONE 9: e101783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ocholla H, et al. , 2014. Whole-genome scans provide evidence of adaptive evolution in Malawian Plasmodium falciparum isolates. J Infect Dis. 210: 1991–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dechavanne C, et al. , 2017. Associations between an IgG3 polymorphism in the binding domain for FcRn, transplacental transfer of malaria-specific IgG3, and protection against Plasmodium falciparum malaria during infancy: a birth cohort study in Benin. PLOS Med 14: e1002403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vardo-Zalik AM, Zhou G, Zhong D, Afrane YA, Githeko AK, Yan G, 2013. Alterations in Plasmodium falciparum genetic structure two years after increased malaria control efforts in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg 88: 29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Escalante AA, et al. , 2015. Malaria molecular epidemiology: lessons from the international centers of excellence for malaria research network. Am J Trop Med Hyg 93 (3 Suppl): 79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laufer MK, Plowe CV, 2004. Withdrawing antimalarial drugs: impact on parasite resistance and implications for malaria treatment policies. Drug Resist Updat 7: 279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohd Abd Razak MR, et al. , 2016. Genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum populations in malaria declining areas of Sabah, east Malaysia. PLoS One 11: e0152415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ojurongbe O, Ogungbamigbe TO, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Fendel R, Kremsner PG, Kun JF, 2007. Rapid detection of Pfcrt and Pfmdr1 mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolates by FRET and in vivo response to chloroquine among children from Osogbo, Nigeria. Malar J 6: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN, 1993. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol 61: 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felger I, Snounou G, 2007. Recommended Genotyping Procedures (RGPs) to Identify Parasite Populations. Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/rgptext_sti.pdf?ua=1. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 28.Mwingira F, Nkwengulila G, Schoepflin S, Sumari D, Beck H-P, Snounou G, Felger I, Olliaro P, Mugittu K, 2011. Plasmodium falciparum msp1, msp2 and glurp allele frequency and diversity in sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J 10: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K, 2016. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33: 1870–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozas J, 2009. DNA sequence polymorphism analysis using DnaSP. Posada D, ed. Bioinformatics for DNA Sequence Analysis; Methods in Molecular Biology Series. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tajima F, 1989. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123: 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu YX, Li WH, 1993. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics 133: 693–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turner L, Wang CW, Lavstsen T, Mwakalinga SB, Sauerwein RW, Hermsen CC, Theander TG, 2011. Antibodies against PfEMP1, RIFIN, MSP3 and GLURP are acquired during controlled Plasmodium falciparum malaria infections in naive volunteers. PLoS One 6: e29025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duru KC, Thomas BN, 2014. Genetic diversity and allelic frequency of glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from sub-Saharan Africa. Microbiol Insights 7: 35–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ojurongbe O, Fagbenro-Beyioku AF, Adeyeba OA, Kun JF, 2011. Allelic diversity of merozoite surface protein 2 gene of P. falciparum among children in Osogbo, Nigeria. West Indian Med J 60: 19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conway DJ, 2007. Molecular epidemiology of malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev 20: 188–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yuan L, et al. , 2013. Plasmodium falciparum populations from northeastern Myanmar display high levels of genetic diversity at multiple antigenic loci. Acta Trop 125: 53–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar D, Dhiman S, Rabha B, Goswami D, Deka M, Singh L, Baruah I, Veer V, 2014. Genetic polymorphism and amino acid sequence variation in Plasmodium falciparum GLURP R2 repeat region in Assam, India, at an interval of five years. Malar J 13: 450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jongwutiwes S, Putaporntip C, Hughes AL, 2010. Bottleneck effects on vaccine-candidate antigen diversity of malaria parasites in Thailand. Vaccine 28: 3112–3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robert F, Ntoumi F, Angel G, Candito D, Rogier C, Fandeur T, Sarthou JL, Mercereau-Puijalon O, 1996. Extensive genetic diversity of Plasmodium falciparum isolates collected from patients with severe malaria in Dakar, Senegal. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 90: 704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Stricker K, Vuust J, Jepsen S, Oeuvray C, Theisen M, 2000. Conservation and heterogeneity of the glutamate-rich protein (GLURP) among field isolates and laboratory lines of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol 111: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ndam NT, Basco LK, Ngane VF, Ayouba A, Ngolle EM, Deloron P, Peeters M, Tahar R, 2017. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive pfcrt K76 Plasmodium falciparum genotype in southeastern Cameroon. Malar J 16: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang B, et al. , 2016. Prevalence of crt and mdr-1 mutations in Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Grande Comore island after withdrawal of chloroquine. Malar J 15: 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kublin JG, Cortese JF, Njunju EM, Mukadam RAG, Wirima JJ, Kazembe PN, Djimdé AA, Kouriba B, Taylor TE, Plowe CV, 2003. Reemergence of chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum malaria after cessation of chloroquine use in Malawi. J Infect Dis 187: 1870–1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeeshan M, et al. , 2012. Genetic variation in the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in India and its relevance to RTS,S malaria vaccine. PLoS One 7: e43430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]