Abstract

Introduction

From its initial report on two female patients in 1979 by J.O. Susac, Susac syndrome (SuS) or SICRET (small infarctions of cochlear, retinal and encephalic tissue) has persisted as an elusive entity. To date the available evidence for its treatment is based on case reports and case series. The largest systematic review described only 304 reported cases since the 1970s. Here we presented the first reported case to our knowledge in Mexican population and the unusual presentation in a pregnant patient.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old Hispanic woman was brought to the ER in our hospital for apathy and behavioral changes. Upon arrival at the ER, her husband described a one-month history of behavioral changes with apathy, progressive abulia, visuospatial disorientation, and gait deterioration. The initial lab test shows no significance except by a positive qualitative hCG. An MRI was obtained and showed hyperintense periventricular white matter lesions in T2 and FLAIR sequences also involving bilateral basal ganglia and with predominant affection of the corpus callosum, in addition to infratentorial cerebellar lesions. After treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins a marked and prompt clinical and radiological improvement was observed.

Conclusion

SuS is still an elusive disease. To date, no definitive score or clinical feature can predict the outcome of the disease. The presentation during pregnancy is also rare and therefore the optimal treatment and the prognosis is unknown. We hope that this article will serve as a foundation for future research.

Keywords: Susac syndrome, Neuroinflammation, Corpus callosum, Demyelinating disease, Vasculitis

1. Introduction

From its initial report on two female patients in 1979 by J.O. Susac, Susac syndrome (SuS) or SICRET (small infarctions of cochlear, retinal and encephalic tissue) has persisted as an elusive entity. To date the available evidence for its treatment is based on case reports and case series. The largest systematic review described only 304 reported cases since the 1970s [1]. Here we presented the first reported case to our knowledge in Mexican population and the unusual presentation in a pregnant patient.

2. Clinical case

A 34-year-old Hispanic woman was brought to the ER in our hospital for apathy and behavioral changes. She had no prior neurological or systemic disease, no exposure to toxic or vascular risk factors, and had suffered a self-limiting (3-days duration) episode of incapacitating vertigo 6 months prior and an episode of right ear tinnitus (2 days of duration) 2 months before hospitalization without receiving any medical care.

Upon arrival at the ER, her husband described a one-month history of behavioral changes with apathy, progressive abulia, visuospatial disorientation, and gait deterioration. Initial exploration revealed a patient with auto-activation apathy, monotonous and dysprosodic speech and bilateral corticospinal involvement with hyperreflexia and Babinski's sign but no weakness.

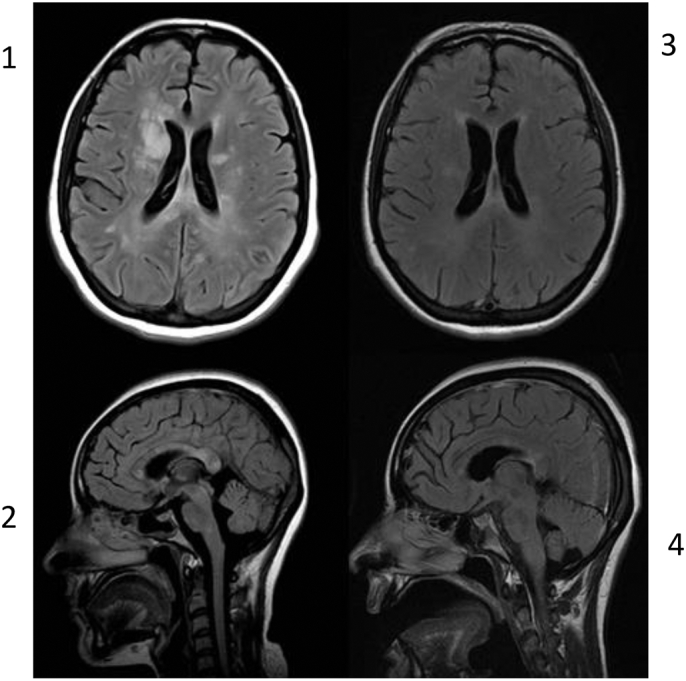

The initial lab test shows no significance except by a positive qualitative hCG. The patient was unable to answer for any G/O history and her husband was also oblivious about it. An MRI was obtained and showed hyperintense periventricular white matter lesions in T2 and FLAIR sequences also involving bilateral basal ganglia and with predominant affection of the corpus callosum, in addition to infratentorial cerebellar lesions. Lesional restriction of diffusion but no contrast enhancement was observed. T1 weighted images showed hypointense lesions in the same topography (Fig. 1). Due to prominent pericallosal lesions with clinical findings of medial frontal syndrome and bilateral corticospinal involvement of monophasic subacute evolution, primary vs secondary demyelinating disease was suspected. A lumbar puncture was performed resulting and CSF values showed proteins of 77 mg/dl, glucose of 52 mg/dl (serum glucose of 89 mg/dl), and no cells. Anti-AQP4 antibodies and oligoclonal bands were absent in CSF. A comprehensive workup for viral encephalitis and atypical infectious-disease result negative and cultures for fungi and bacteria. Also given the impossibility to further image studies as a complete CT and PET, a workup for paraneoplastic neurologic antibodies was obtained that was also negative Complete rheumatologic workup was negative except for 1: 2560 antinuclear antibodies in a speckled staining fine pattern without any systemic clinical correlate. Obstetric evaluation showed a normal development 15 weeks GA fetus.

Fig. 1.

MRI FLAIR sequence. Part 1 and 2 Pretreatment images shows hyperintense lesions with predominantly pericallosal involvement in the subependymal striatons and the snowball lesions. Part 3 and 4 shows IgIV post treatment changes with almost complete disappearance of the previous lesions.

Upon admission, 5 pulses of methylprednisolone were administered without obvious clinical improvement. Immunomodulatory treatment was escalated to intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) at 0.4 g/kg/day for 5 days. After treatment with IVIg, neuropsychiatric symptoms of medial frontal syndrome remitted, and the patient could cooperate for further study. Ophthalmologic assessment revealed retinal vasculitis corroborated by fluorangiography (FA) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Audiometric testing showed bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. A new MRI showed prior lesions to be smaller or absent, and the patient showed clinical improvement confirmed by neuropsychological testing. Once the diagnosis of SuS was established. The husband decided not to continue further with the pregnancy and a therapeutic abortion was performed, the patient was discharged for further treatment with oral steroids and CCF.

3. Discussion and conclusion

Here we discuss an atypical patient with the unusual diagnosis of Susac syndrome in a Mexican woman who was also in the first trimester of pregnancy. The anatomical basis of the clinical diagnosis as a subacute and evolving frontal syndrome in a young woman guide or workup to focus in autoimmune disorders, demyelinating disorders and structural lesions. The MRI allows to focus on the overview of predominantly callosal disease.

Differential diagnosis of corpus callosum lesions includes demyelinating, non-demyelinating inflammatory lesions, and transient splenial lesions. Demyelinating lesions include MS, neuromyelitis optica and ADEM, all of which were discarded in this patient based on the respective criteria for each one. Non-demyelinating inflammatory lesions include SuS and CNS vasculitis [2]. It is particularly important to differentiate SuS from MS. In SuS, lesions of the corpus callosum are typically centrally located, while the lesions in MS and ADEM involve the undersurface at the septal interface, in MS, these lesions are often extended around the venules of the brain, resulting in a finger-like appearance (“Dawson fingers”), while lesions appear circular in SuS. Typically, these callosal lesions involve the central fibers and spare the periphery [3] MRI reveals widespread abnormalities of the corpus callosum, manifested as small central holes, particularly in the splenium. Linear defects of the corpus callosum can also be detected, the so-called “spokes”, representing microinfarctions of obliquely radiating axons [4]. The localization of the lesions is probably explained by the angioarchitecture of the corpus callosum. The inflammation and occlusion of the small precapillary arterioles with a diameter under 100 μm result in infarction of the central portion, but not the undersurface of the corpus callosum [4]. Subsequent documented involvement of retinal vasculitis and vestibulocochlear damage established the diagnosis in our patient.

SuS is currently considered a vasculitis with predominantly endothelial affection of autoimmune origin probably mediated by endothelial cell antibodies (AECA), with subsequent response by complement with C4d deposits, “mummification” phenomena, and endothelial necrosis [5]. Nevertheless, a study showed that in fact only 30% of patients with definite SuS have AECA, suggesting that AECA represent a secondary phenomenon in an etiologically heterogeneous syndrome, with a pathogenesis still far from fully understood [6]. Respecting the other autoantibodies and considering the high titers of ANA in our patients we found that antinuclear autoantibodies have been described in patients with SuS, but do not occur more often than in healthy controls [6].

Diagnosis of SuS is predominantly clinical and based on the evidence of the originally described triad with encephalic, retinal and vestibulocochlear affection. The clinical features include encephalopathy that is characterized by headache that may be migrainous or oppressive. Headache often occurs up to six months before the onset of the other symptoms. It is probably due to an affection of the leptomeningeal vessels. The other symptoms of encephalopathy have a stroke-like or subacute onset, with neuropsychological deficits, bladder disturbance, long tract signs, focal neurological signs, seizures, and often disturbance of consciousness [1]. The hearing loss can be a dramatic and severely disabilitating feature of Susac syndrome. It often occurs overnight and may affect both ears. A loss of the low or middle frequencies is typical, but loss of high frequencies can also occur. The severe hearing loss is often accompanied by vertigo and a roaring tinnitus. The hearing loss is caused by occlusion of the cochlear precapillary arterioles and those of the semicircular canal. Hearing loss is often irreversible and may require cochlear implants or hearing devices for a whole life [7]. Typical findings in patients with SuS include branch retinal artery occlusions (BRAO) detectable on retinal fluorescein angiography, the occlusions may affect the periphery and may not lead to clinical symptoms, but they can also affect the larger branches resulting in visual field deficits. Many patients complain about blurred vision or photopsia [7]. MRI, retinal fluorescein angiography, and audiometry are considered crucial tests to enable diagnosis.

In 2016, specific diagnostic criteria based on a cohort of 32 patients was proposed: Definitive SuS requires involvement of these 3 systems [8]. Being a rare disease, the clinical course and prognosis is largely unknown. Based on empirical stratification [9] the course can be monocyclic, polycyclic and chronic–continuous with a cutoff parameter of 2 years separating the monocyclic course from the other forms.

Many treatment approaches for SuS have been described in case reports and series, but rigorous analysis of these therapies is limited by inconsistent and often incomplete reports. In the acute period, treatment with steroids, IVIg, plasma exchange, and even rituximab has been reported with predominantly successful response [10]. Antithrombotic agents and nimodipine have also been used, aiming to maintain blood flow and prevent vasospasm [7]. Optimal chronic management and duration of treatment is unknown, yet the decision to withdraw treatment must incorporate surveillance brain MRI and FA findings in addition to clinical symptoms and signs.

We have managed to find 7 cases previously reported in the literature in English and in Spanish of cases that have started with Susac syndrome during pregnancy [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17] (Table 1). Unfortunately, the behavior of the disease is heterogeneous. Dr. Aubert-Cohen et al. have also managed to report the behavior of the disease before and after pregnancy in 4 patients. Obviously, the low frequency of the disease does not allow obtaining any statistically significant result. But we hope that this article will serve as a foundation for future research.

Table 1.

Comparison of data of the different reported cases of Susac syndrome with onset in pregnancy.

| Cases | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Published by | Gordon19918 | McFayden19879 | Hua201410 | Ionnides201311 | Engelholm201312 | Antulov201413 | Feresiadou201414 | Our case |

| Origin | US | Canada | US | Australia | Germany | Croatia | Sweden | Mexico |

| Age | 28 | 31 | 25 | 28 | 32 | 21 | 35 | 34 |

| Gestational age at onset (weeks) | 28 | No specified | 14 | 13 | 32 | 35 | 37 | 15 |

| Previous medical history | None | None | None | Epilepsy from a perinatal ischaemic event | None | None | Apparent similar clinical picture at 12 yo, treated with steroids | None |

| System of onset | Eye | Eye | Auditory | Neurologic | Neurologic | Neurologic | Auditory | Auditory |

| Neurologic symptoms | Unilateral weakness, dysarthria and apathy | Ataxia and dysarthria | Amnestic syndrome, Gait disorder, Bilateral severe weakness | Bilateral severe weakness and dysarthria | Encephalopathic syndrome and Unilateral weakness | Bilateral severe weakness and progressive cognitive affection | None | Cognitive affection (frontal medial syndrome) and bilateral weakness |

| Ophthalmologic symptoms | Visual field deficit | Visual field deficit | Loss of visual acuity | Loss of visual acuity | Visual field deficit | None | Loss of visual acuity and visual field deficit | Loss of visual acuity |

| Auditory symptoms | Bilateral neurosensorial hearing loss | Bilateral tinnitus and neurosensorial hearing loss | Tinnutus | Right neurosensorial hearing loss | Neurosensorial hearing loss | Left neurosensorial hearing loss | Tinnitus and left neurosensorial hearing loss | Tinnitus and bilateral neurosensorial hearing loss |

| Additional or atypical affection | None | None | Cervical cord involvement | None | Livedo racemosa | None | None | None |

| Time until fully triad (months) | 1 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1.5 | Not completed | Not completed | 6 |

| MRI findings | ||||||||

| Deep grey matter | No | Not done | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| White matter | Callosal and periventricular | Not done | Callosal and periventricular lesions | Callosal | Callosal and periventricular lesions | Callosal and periventricular lesions | No | Callosal |

| Posterior fossa involvement | No | Not done | Yes | No, but also reported meningeal enhancement | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Gadolinium enhancement | No reported | Not done | Yes | No reported | Yes | No reported | No | Yes |

| CSF findings | ||||||||

| Proteins mg/dl | No reported | 252 | 95 | 2000 | 1800 | 1009 | No performed | 77 |

| Cells (Mono) | No reported | 0 | 6 | 9 | No reported | No reported | No performed | 0 |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| Initial treatment | Heparin | None | IVMP × 5 | IVMP × 3 | IVMP × 5 | IGIV × 5 | IVMP × 5 | IVMP × 5 |

| Response | Partial | Partial | No response | Partial | Complete response | Partial | No response | |

| 2nd line treatment | None | None | Oral prednisone | PLEX and IVIg | Oral prednisone | None | None | IgIV |

| Chronic treatment | Warfarin | Oral prednisone | MMF | MMF | MMF + MTX | AZA | Oral prednisone | CCF |

| Response | Almost complete recovery | Partial remission | Partial remission | No response | Almost complete recovery | Almost complete recovery | Almost complete recovery | Partial remission |

| Prognosis | ||||||||

| Follow up (years) | 0.2 | 4 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.5 |

| Sequels | Visual deficit | Mild hearing loss | Cognitive deficit with visuospatial and word recall | No specified | Mild cognitive deficit | Subtle weakness | Mild left hearing loss | Cognitive deficit |

| Course of disease | Monocyclic | Monocyclic | Chronic continuous | Probably Monocyclic | Probably Monocyclic | Monocyclic | Probably Monocyclic | |

| Final pregnancy state | Healthy product | Healthy product | Healthy product | Therapeutic abortion at 15 weeks GA | Healthy product | Healthy product | Healthy product | Therapeutic abortion at 17 weeks GA |

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Retinal Fluorangiography reveals predominantly acute and branch arterial occlusions with secondary retinal infarctions.

Contributions

Dr. Calleja-Castillo was in charge of the diagnosis, treatment care and follow up of the patient and supervised the elaboration of the manuscript. Dr. Gomez-Figueroa prepared the draft. All authors were part of the patient care team and approved the final submitted version.

Written consent to publish was obtained from the patient.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no competing interests or external funding.

References

- 1.Dörr J., Krautwald S., Wildemann B. Characteristics of Susac syndrome: a review of all reported cases. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013;9:307–316. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaig N., Reddel S.W., Miller D.H. The corpus callosum in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis and other CNS demyelinating and inflammatory diseases. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2015;0:1–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleffner I., Deppe M., Mohammadi S. Neuroimaging in Susac's syndrome: focus on DTI. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010;299:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleffner I. A brief review of Susac syndrome. J. Neurol. Sci. 2012;322:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susac J.O. Susac's syndrome: 1975–2005 microangiopathy/autoimmune endotheliopathy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007;257(1):270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarius et al. Clinical, paraclinical and serological finding in Susac syndrome: an international multicenter study. J. Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vishnevskia-dai V., Chapman J., Sheinfeld R. Susac syndrome: clinical characteristics, clinical classification, and long-term prognosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5223. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleffner I., Dörr J., Ringelstein M. Diagnostic criteria for susac syndrome. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2016;87:1287–1295. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rennebohm R.M., Egan R.A., Susac J.O. Treatment of Susac's syndrome. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2008;10:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s11940-008-0008-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vodovipec I., Prasad S. Treatment of Susac syndrome. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2016;18:3–8. doi: 10.1007/s11940-015-0386-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon D.L., Hayreh S.S., Adams H.P., Jr. Microangiopathy of the brain, retina, and ear: improvement without immunosuppressive therapy. Stroke. 1991;22:933–937. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacFadyen D.J., Schneider R.J., Chisholm I.A. A syndrome of brain, inner ear and retinal microangiopathy. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987;14:315–318. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100026706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua, L.H. et al. A case of Susac syndrome with cervical spinal cord involvement on MRI. J. Neurol. Sci., 337, 1, 228–231. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ioannides Z.A., Airey C., Fagermo N. Susac syndrome and multifocal motor neuropathy first manifesting in pregnancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013;53:314–317. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maik Engeholm M., Leo-Kottler B., Rempp H. Encephalopathic Susac's syndrome associated with livedo racemosa in a young woman before the completion of family planning. BMC Neurol. 2013;13(185) doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antulov R., Holjar-Erlic I., Perkovic O. Susac's syndrome during pregnancy—the first Croatian case. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014;341(1–2):162–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feresiadou A., Eriksson U., Larsen H.-C. Recurrence of Susac syndrome following 23 years of remission. Case Rep. Neurol. 2014;6:171–175. doi: 10.1159/000362868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Retinal Fluorangiography reveals predominantly acute and branch arterial occlusions with secondary retinal infarctions.