Abstract

The study’s goals were twofold, (a) to examine the effectiveness of narrating an angry experience, as compared to relying on distraction or mere reexposure to the experience, for anger reduction across childhood and adolescence, and (b) to identify the features of narratives that are associated with more and less anger reduction for younger and older youths and for boys and girls. Participants were 241 youths (117 males) between the ages of 8 and 17. When compared to mere reexposure, narration was effective at reducing youth’s anger both concurrently and in lasting ways; though narration was less effective than distraction at concurrently reducing anger, its effect was longer lasting. Contrary to expectation, there were no overall age differences in the relative effectiveness of narration for anger reduction; however, the analyses of the quality of youth’s narratives and of the relations between various narrative features and reductions in anger, indicated that narration works to reduce distress among youth via processes that are distinct from those postulated for adults. Altogether, this study’s findings lend strong support to the potential of narration for helping youth across a broad age range manage anger experiences in ways that can reduce distress.

Keywords: narration, emotion regulation, narration across childhood and adolescence

Emotion regulation is a central concern in developmental psychology, with broad relevance to adaptive outcomes (e.g., Compas, Jaser, et al., 2017; Gross & Thompson, 2007; Mullin & Hinshaw, 2007; Thompson, 2014; Valiente, Eisenberg, Fabes, Spinrad, & Sulik, 2015; Zeman, Cassano, Perry-Parrish, & Stegall, 2006). Recent available evidence indicates that distinct negative emotions have different associations with regulation strategies (e.g., Cole et al., 2011; Dennis & Kelemen, 2009; Gross, Richards & John, 2006; Roque & Verissimo, 2011; Zimmermann & Iwanski, 2014), strongly suggesting that new investigations should focus not on emotion regulation broadly, but on the regulation of specific emotions.

In the present studies, we focus on the regulation of anger. In interpersonal contexts specifically, anger is a response to a sense of being injured, unjustly treated, or thwarted (e.g., Levine, Prohaska, Burgess, Rice, & Laulhere, 2001). Psychologically and physiologically, anger marshals resources for aggressive responding (Levenson, 1999), and thus it is not surprising that both individuals and societies have concerns with managing anger. Because anger is a recurrent and enduring emotion throughout childhood and adolescence (e.g., Sears, Repetti, Reynolds & Sperling, 2014; Von Salisch & Vogelgesang, 2005; Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, 2002), youth must acquire effective capacities to manage anger; failure to do so is associated with problematic developmental, social, and health outcomes (e.g., Kerr & Schneider, 2008).

When striving to manage anger, people often seek to reduce the intensity of the emotion, which allows for a slower and more deliberate response and diffuses the potential for serious aggression and relational damage. This can sometimes be accomplished via distraction, that is, the shifting away from the upsetting experience towards some other absorbing or positive focus. Research with adults (e.g., Kross & Ayduk, 2008; Pasupathi et al., 2017) suggests that distraction is resoundingly successful at reducing anger, but only while the person is distracted. Once the person is again reminded of the distressing event, anger returns to its initial levels. There are circumstances in everyday life (e.g., a hostile exchange with a cashier while shopping) when temporary relief is adequate. However, when the anger occurs in the context of meaningful relationships, the temporary reduction in anger afforded by distraction may be insufficient as it allows the events to remain ongoing emotional liabilities with interpersonal implications.

By contrast, narration offers unique avenues for reducing anger in a more lasting way. Because narration involves rehearsing and re-encoding memories, along with altered and more positive reappraisals of the event, it can result in lasting changes to memory and meaning, and therefore may effect relatively lasting reductions to emotional distress (Pasupathi et al., 2017). Research has indeed shown that narrating is effective at reducing negative emotions for adults, thus offering an added regulatory benefit over distraction.

However, not all narratives are equally effective at reducing negative emotion. Findings suggest that when adults elaborate the psychological aspects of their experience (Smyth & Pennebaker, 2008), explore the meanings of the experience for the self (e.g., Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011; Thorne, McLean, & Lawrence, 2004), construct positive meanings akin to some types of reappraisal (Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011), and resolve the events by placing them firmly in the past (Pasupathi et al., 2017; Smyth & Pennebaker, 2008), they report higher well-being and, in studies that focus specifically on negative emotions, reduced negative affect. While the precise mechanisms by which these effects emerge await more detailed investigation, psychological elaboration might work to reduce distress because it allows people to express the emotions and thoughts associated with experiences, thus serving as a kind of antithesis of suppression which is known to have problematic outcomes (e.g., Gross, 2001). Exploratory processing might build on psychological elaboration to afford the consideration of how the experience can be integrated with the person’s unfolding life story – again, rendering the event less disruptive. Exploratory processing provides a foundation for positive meaning-making, which constructs the ‘silver lining’ in distressing experiences and may directly promote more positive emotional experience and reduced distress. Finally, resolution places events in the past so that they do not continue to be experienced as intrusive, which would also undermine well-being. Notably, these narrative features – elaboration, exploration, positive meaning-making, and resolution – are consistent with the idea that narrative is an important tool for engaging in reappraisal, although reappraisal has been studied in ways that do not examine narration (e.g., Kross & Ayduk, 2008; Ray et al., 2008; Ochsner & Gross, 2008). Importantly, the findings about the associations between the quality of adults’ narratives and adults’ wellbeing and reduced negative affect span correlational, prospective longitudinal, and even experimental designs, strongly supporting the causal role of narration (McLean, Pasupathi, & Pals, 2007; Pasupathi et al., 2017).

In this study, we ask whether and how these processes work with youth. The developmental literature broadly suggests that both distraction and narration are available to youth as potential approaches to regulating emotions in general and anger in particular. Distraction is widely engaged in by youth of all ages, and is employed for its function of reducing emotional distress (e.g., Davis, Levine, Lench, & Quas, 2010; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, 2011). In fact, distraction, which entails both behavioral (doing something distracting) and cognitive (thinking about something else) components, is among the earliest emerging emotion regulation strategies and continues to be commonly used by adolescents. Furthermore, distraction is also among the most preferred strategies used by children and adolescents alike for managing angry encounters (e.g., Von Salisch & Vogelgesang, 2005). These considerations make distraction an especially useful benchmark against which to compare the relative effectiveness of narration as a regulation strategy in youth.

Narration is also broadly available to youth. Youth as young as 3 engage in narration with parents (e.g., Fivush & Nelson, 2004; Reese, Yan, Jack, & Hayne, 2010), and the frequency with which youth narrate experiences of anger may increase with age across adolescence (e.g., Shipman, Zeman, Nesin, & Fitzgerald, 2003). However, although this literature establishes that children and adolescents engage in narration of their everyday emotional experiences and examines the narratives they generate about those experiences, it does not focus on the extent to which those narratives serve to downregulate distress. Because narration has a wide range of potential functions for people of all ages (e.g., Fivush &Nelson, 2004), the fact that youth narrate their experiences does not necessarily imply that such narration is effective for emotion regulation. Indeed, the effectiveness of narration as an emotion-regulation strategy for youth samples has not been directly examined.

This study thus tackled two sets of questions bearing on the effectiveness of narration across childhood and adolescence. We asked about (a) the concurrent and lasting effectiveness of narration, compared to distraction, as a strategy for reducing anger in youth, and (b) the features of narratives that were associated with more and less anger reduction in youth. As we explain below, we anticipated that the relativeness effectiveness of narration and the features that made narration effective might vary with youth’s age and gender.

The Effectiveness of Narration Across Childhood and Adolescence

Based on the broad availability and use of distraction as a regulation strategy in youth (Gross, 2001), there is little reason to expect age differences in its effectiveness across childhood and adolescence, although research with adults suggests that distraction will likely confer concurrent, but no lasting, anger regulation for youth. Because distraction can take many forms (e.g., Gerin et al., 2006; Strick et al., 2009), we included two types of distraction in our study – one focused on a social activity (narrating a positive event to an interviewer), and one focused on a solitary activity (playing a video game) – to better capture the range of what youth might actually do; we expected no differences in these forms vis-à-vis reduction of anger.

By contrast, there are several reasons to believe that narration may only become effective for emotion regulation in mid-adolescence. First, consider evidence from the broader literature on the development of emotion regulation. Although this literature has not directly examined narration, it has considered strategies that are associated with the act of narrating, especially cognitive reappraisal and social support seeking. These strategies emerge over childhood but only become more prevalent in late childhood and adolescence (e.g., Band & Weisz, 1988; Thompson, 2014). Second, even though 5-year-olds can already narrate basic events, especially with the help of adults (e.g., Fivush & Nelson, 2004; Reese et al., 2010), mature narrative capacities are constructed slowly across childhood and are not fully in place until mid-adolescence (e.g., Habermas & de Silveira, 2008; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010). Specifically, a considerable body of empirical work has shown that the four key features of narrative quality for emotion regulation in adults — psychological elaboration, exploratory processing, positive meaning, and resolution — follow different developmental trajectories. Psychological elaboration increases across early childhood and through adolescence, with a sharp increase happening after about age 11 (Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010). Dimensions related to exploratory processing (e.g., autobiographical reasoning) and meaning-making (e.g., conclusions about oneself) emerge somewhat later, between ages 12 and 16, and continue to develop into mid-life (McLean & Breen, 2009; Reese et al., 2010). Resolution per se has not been as widely studied with youth samples, but findings on the related ability for temporal coherence suggest that the capacity to place multiple events in a well-ordered past emerges in middle childhood and attains adult levels by mid-adolescence (Kober, Schmiedek, & Habermas, 2015).

Based on these considerations, we might expect that whereas distraction will be similarly effective across childhood and adolescents, narration will be a more effective strategy among adolescents than among children. However, as noted earlier, not all narratives work equally well at reducing anger for adults. Therefore, to the extent that narration is effective in youth, it is also important to ask how narrative works to effect distress reduction across childhood and adolescence.

Given the evidence about the age-related changes in the quality of youth’s narratives, and assuming that narrative features work in youth samples like in adult samples, we would expect that narration would be more effective among mid- and later adolescents than younger youth. Further, we would expect that the age differences in the effectiveness of narration would be accounted for by age-related variations in the four key narrative features. Thus, when looking only at the participants who narrated to regulate their anger, we would anticipate that youth who narrate with more psychological elaboration, more exploratory processing, more positive meaning-making, and greater resolution would report stronger reductions in anger. However, there is another possibility to consider.

Some research has shown that even when youth construct a narrative that is psychologically elaborated, explores the implications for the self, constructs positive meanings, and resolves the event, youth may not benefit from this narration in the way that is routinely observed for adults. As examples, more psychological elaboration, especially of emotion, is linked to reduced well-being in samples of pre- and early adolescents (e.g., Fivush et al., 2007); causal coherence, akin to exploratory processing, has positive correlates in older adolescents but negative correlates in younger teens (Reese et al., 2016); pre-adolescents who use more positive emotion terms in narrating negative experiences report less adaptive coping strategies than do older adolescents (e.g., Styers & Baker-Ward, 2013); and, at least in a sample of boys, early adolescents who made more sophisticated meanings in their narratives reported lower well-being (e.g., McLean et al., 2010). By mid- to late-adolescence, narrative features appear to relate to higher well-being in ways similar to adult samples (McLean & Breen, 2009; McLean et al., 2010; Soliday et al., 2004; Styer & Baker-Ward, 2013; see also Habermas & Reese, 2015). These findings raise the possibility that if narration is effective across childhood and adolescence, it may work via processes other than those that have been examined in extant work with adults.

The Effectiveness of Narration for Girls and Boys

The evidence is mixed about whether we should anticipate gender differences in the relative effectiveness of narration versus distraction for reducing anger among youth. Work on the socialization of narration suggests that parents may emphasize narration of emotional events more for girls than for boys (e.g., Bohanek et al., 2008; Root & Denham, 2010), and the emotion regulation literature suggests that girls rely on social support and emotional expression as regulatory strategies more than boys (e.g., Chaplin & Aldao 2013; Hampel & Petermann, 2005; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). At the same time, some narrative socialization research suggests that mothers may encourage the inhibition of anger more in girls than in boys (Fivush et al., 2000; Zeman et al., 2010), and evidence from the emotion regulation literature concerning gender differences in reappraisal is mixed (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011). In relation to distraction, some work suggests that boys prefer distraction-related strategies more than girls (e.g., Hampel & Petermann, 2005), but reviews deem this evidence weak (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Altogether, this literature suggests that narration might be more effective for girls whereas distraction might be equally effective for boys and girls, but the evidence for this prediction is not strong.

In relation to the features of narratives that might be associated with more and less anger reduction in boys and girls, some studies find gender differences in the key narrative features in youth samples. Specifically, girls tell more psychologically elaborated stories than boys of the same age (Fivush et al., 2000; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010), a difference attributed to gendered socialization patterns in which parents promote more elaborative and emotional recall with girls (Bohanek et al, 2008; Fivush et al., 2000; Root & Denham, 2010). Also, girls may more quickly attain mature narrative capacities with respect to exploratory processing and meaning-making (McLean & Mansfield, 2012). In all, then, girls’ “better” narratives might mean that girls benefit earlier and/or more than boys from narrating angry experiences. Nevertheless, there is also reason to examine whether narrative features are differentially associated with reductions in anger for boys and girls. For example, in one study of 14–17 year-olds (McLean & Breen, 2009) narrative qualities were more strongly linked to well-being among adolescent boys than girls, a finding also consistent with some findings from the expressive writing literature on adults (Smyth, 1998).

Present Study

Two sets of questions are examined. The first concerns the effectiveness of narration for reducing anger among boys and girls ranging in age from 8 to 17. We compare narration to two distinct distraction activities. Distraction via playing a single-player video game (“distract-game”) represents an ecologically valid form of solitary distraction for youth (Cummings & Vandewater, 2007; Ferguson & Olson, 2013); distraction via narrating a positive event to the experimenter (“distract-talk”) represents a form of distraction that combines refocused attention with social engagement, while also helping us to rule out the possibility that any observed emotion outcomes are accounted for by any narration to a sensitive adult. The narration and two distraction conditions are compared to a control condition (“reexposure-control”) where youth are instructed to think again about the angry event, to ensure that the observed emotion outcomes of narration and distraction could not be accounted for by mere reexposure. We compare the relative effectiveness of narration, distraction, and reexposure at reducing anger concurrently (while engaged in the assigned emotion regulation strategy), and upon short-term and longer-term reminders of the experience. Based on prior work with adults as well as the developmental and gender considerations discussed above, we anticipate a main effect of regulation condition such that distraction is more concurrently effective than narration or reexposure; an age by condition interaction such that narration is more concurrently effective than reexposure and has more lasting effects than both distraction or reexposure, in mid- and later adolescence but not in childhood and early adolescence; and finally, we anticipate a possible gender by condition interaction in which narration, relative to distraction, is more effective for girls than for boys.

Our second set of questions examines links between reductions in anger and four narrative features: psychological elaboration, exploratory processing, positive meaning-making, and resolution. Based on known age and gender differences in narrative capacities we expect that older participants and girls produce narratives with more of these features, but have competing hypotheses about the association between these age and gender differences and reductions in anger. From the adult literature, we expect that the features operate similarly and that higher ratings of narrative quality are related to steeper reductions in distress for boys and girls of all ages. However, the youth literature suggests that these features might only relate to steeper reductions in distress among older adolescents, and more tentatively, that narrative features might matter more for distress reduction in boys.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and seventy eight youth between the ages of 8 and 17 years, evenly distributed within two-year age categories (8–9, 10–11, 12–13, 14–15, 16–17), were recruited from local schools and community organizations in a Rocky Mountain metropolitan area, for a study on “how young people learn to regulate their emotions”. Data for 37 participants were excluded due to data collection errors or failure to participate in both sessions, leaving a final sample of 241 participants, including 117 males (Mage=12.50, SDage=2.89) and 124 females (Mage=12.73, SDage=2.83); an additional 2–4 participants were excluded from specific analyses based on partial missing data. Sample characteristics closely matched those of the region’s population, with 86% of the sample identifying as European American, 7% as Latino/a, 4% as African American, and 3% as Asian American. Youth were paid $20 for their participation in session 1 and $30 for their participation in session 2, with an additional $5 for timely arrival.

Participants were randomly assigned to a regulation condition, with roughly equal distribution of males and females per condition, but the narration condition was oversampled to allow for testing of differences in narrative features (Ns for narration=114; distract-game=46; distract-talk=40; and reexposure-control=41). A priori power analyses using Gpower (Faul, Erdfelder, & Buchner, 2009) indicated that this sample size was adequate for detecting moderate to large effects – including interactions of within-participant factors with between-participant factors with power of .80 or greater, depending on the particular hypothesis at stake; more precise effect size estimates were not available from the existing literature. The research received IRB approval (IRB_00049034) from the University of Utah; the project’s title was “When and how do memory narratives function to regulate anger and sadness?”.

Measures and Scoring

The primary measures were ratings of anger obtained for all participants as detailed below. For participants in the narration condition, we also assessed four features of their narratives. In addition, participants in all conditions rated the time elapsed since the event, the event’s importance, and the extent of prior narration of that event; these ratings served to characterize the anger-arousing events that participants recalled.

Anger ratings were obtained once prior to elicitation of the anger experience and four more times, after first recalling the anger experience, after engaging in the assigned emotion regulation strategy, and upon recalling the event both immediately and after a delay. Participants were asked to rate (1=not at all, 5=very, very) “how mad you are you feeling right now?” Single-item assessments were chosen to focus participants’ attention on the target emotion of anger, and to reduce participant burden throughout the lengthy procedure. Although multi-item measures are often preferred, previous work on emotion regulation has successfully employed single-item measures (e.g., MacNamara et al., 2011; Pasupathi et al., 2017; Ray et al., 2008).

Narrative features, obtained via coding of the anger narratives, included psychological elaboration (Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010), exploratory processing (Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011), positive meaning-making (Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011), and resolution (Pasupathi et al., 2015). Twenty five percent of the narratives were coded by a reliability coder; all coders were blind to participants’ responses on other measures. Interrater reliability coefficients for each narrative feature are reported below.

Psychological elaboration captures the extent to which narratives express the narrator’s psychological experiences (emotions, goals, beliefs, evaluations) in relation to the narrated event (0=absent/minimal, 1=adequate, 2=moderate, 3=complete; ICC=.86).

Exploratory processing reflects the extent to which the implications and meanings of the past event for the present self are considered, whether or not any particular conclusions are reached. This goes beyond psychological elaboration in focusing on more long-term, self-related implications of the event (0=the event’s impact is dismissed/minimized, 4=the event’s impact is fully explored; ICC=.77).

Positive meaning-making represents whether the narrator reaches a positive meaning from the narrated event, including assertions of growth and self-improvement goals (0=absence of positive meaning or presence of negative meaning; 1=at least some positive meaning; kappa=.78). As noted (Lilgendahl & McAdams, 2011), positive meaning-making can be facilitated by exploratory processing but is distinct, in that this feature focuses on the assertion of meanings rather than on elements that reflect exploring possible meanings.

Resolution reflects the extent to which the angry situation is represented as being resolved in the present (1=narrator continues to be troubled; 2=partial resolution; 3=past event no longer exerts a negative influence on narrator; ICC=.85).

Characterizing the events

Participants reported on the time since the event (“how long ago did the event occur?”, where 1=less than one week ago, 2=one week to one month ago, 3=one month to six months ago, 4=six months to one year ago, or 5=more than one year ago); their perception on the event’s importance (“how important is this event to you now?”, where 1=not at all, and 5=very very), and previous event narration (“have you previously discussed this event with another person?”, where 1=not at all, and 5=very very). In addition, narratives were coded for the cause of the anger (relational/psychological, physical, or material) and the target of the anger (friend/peer, sibling, parent, other). Twenty eight percent of narratives were coded by a reliability coder; Cohen’s κ for cause and target of anger was .94 and .98, respectively.

Data collected but not included in the present study

As part of exploratory work examining psychophysiological aspects of emotion and narration, we also assessed physiological measures, including heart rate, respiration rate, respiratory-sinus arrhythmia, and skin conductance levels. As in related research (e.g., Mauss, 2005; Pasupathi et al., 2017), these measures were uncorrelated with emotion ratings and were not included in the analyses.

Procedure

Session 1

After consent and assent, participants were connected to physiological equipment recording EKG, respiration, and EDA, and completed baseline tasks required for physiological data. As described below, participants were next asked to recall an angry memory (“initial exposure”). After a 1-minute rest period, they were assigned to a regulation condition (“regulation”) which lasted just over two minutes, and after another 1-minute rest period they were reexposed (“immediate reexposure”) to the angry memory. Following each epoch, participants completed anger ratings. Participants in the four conditions spent just over 2 minutes (range 2.2–2.4 minutes) engaged in their assigned task.

Initial exposure

Participants were asked to recall a recent, specific time in their life, “when someone did or said something and you ended up feeling really mad at that person.” Once they indicated they had identified such an event, they were instructed to “spend a few minutes thinking about that time. Imagine that you’re back in that moment again—the moment when you felt the most mad. Stay with that very mad feeling as long as you can. Just hold on to that mad feeling and try to feel it again.”

Regulation

As explained earlier, participants were randomly assigned to one of four regulation conditions and were given instructions specific to their condition.

Participants in the narration condition were told to narrate their memory of the angry event to a trained research assistant, as follows: “Now I would like you to tell me everything you remember about that time. You know that I wasn’t there, so tell me all the details so I can picture it as though I had been there. Tell me everything that happened, how you felt about it, and also what you learned from that time.”

Participants in the distract-talk condition were asked to recall a positive event in their own life, “when someone did or said something and you felt really happy with that person” and narrate this positive event to a trained research assistant, as follows: “Now I would like you to tell me everything that you remember about that time. You know that I wasn’t there, so tell me all the details so I can picture it as though I’d been there. Tell me everything that happened, how you felt about it, and also what you learned from that time.”

Participants in the distract-game condition were given an iPad and, having been instructed prior to the beginning of the session how to play the matching game AniMatch, were given 2 minutes to play the game on their own.

Participants in the reexposure-control condition were told: “Earlier, I asked you to think of a time in your life when someone did or said something and you felt really mad at that person. Now I want you to remember again that same time when you felt really mad. Do this for a little bit and then I will be back.”

Immediate reexposure

Regardless of the regulatory condition they were assigned to, immediate reexposure to memory was prompted as follows: “For the last time today, we’re going to have you remember again that same time when you felt really mad. Do this for a little bit and then I will be back”.

Conclusion of session 1

Following the immediate reexposure epoch, the physiological equipment was disconnected. Participants provided a title for their autobiographical memory (so that the experimenter could prompt it again one week later), were compensated for their participation in Session 1 and dismissed.

Session 2

Approximately one week later, participants returned to the laboratory, were connected to the physiological equipment, and completed the vanilla and paced breathing baseline tasks. Next, they were reexposed to their angry memory.

Delayed reexposure

For all participants, the prompt for delayed reexposure was: “When you were here last week, we had you remember a time in your life when someone did or said something and you felt really mad at that person. You named that time [memory title]. Now, we’re going to have you remember that same time when you felt really mad. Do this for a little bit and then I will be back.”

Conclusion of session 2

Following the delayed reexposure, participants completed the anger rating, and were disconnected from the physiological equipment, debriefed, and compensated.

Results

Analytic Strategy

Two sets of questions about the utility of narration for promoting anger reduction in youth were examined. First, we employed multilevel modeling to examine the effects of regulation condition on changes in anger ratings across the study; age and gender, as well as their interactions with condition, were included in all analyses, and age was modeled as a continuous variable. Our second set of questions concerned variations within the narration condition, which was oversampled to allow planned within-condition analyses. Specifically, we examined whether variations in narrative quality, as assessed by psychological elaboration, exploratory processing, positive meaning-making, and resolution, might account for variations in reductions in anger ratings (using multilevel modeling.) Age, gender, and interactions of narrative features with age and gender were included to test whether particular narrative features were differentially associated with reductions in anger for youth of different ages and for boys and girls.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents all descriptive data and bivariate correlations for study variables. One set of preliminary analyses examined whether anger ratings during the initial exposure varied as a function of condition, age, or gender using a GLM with epoch (vanilla baseline versus initial exposure) as a within subjects factor, and age modeled as a continuous variable. This analysis revealed significant effects for epoch, F(1, 233)=19.65, p<.001, ηp2=.078, condition, F(3, 233)=3.30, p=.021, ηp2=.041, and epoch by condition interaction, F(3, 233)=4.15, p=.007, ηp2=.051. Follow-up tests of the epoch by condition interaction revealed that while all participants reported significantly more anger in the initial exposure epoch than at baseline (p<.001), the magnitude of the response varied somewhat by condition. Descriptively, those in the distract-talk condition reported the smallest increases in anger (an average difference of about 1.0 point increases), with the other conditions reporting on average a 1.3 to 1.7 point increase in anger. These initial differences mean that the most informative comparisons in the main analyses will concern differences in patterns of within-participant change in anger, rather than between-participant comparisons within a particular epoch. Due to this, we chose multilevel modeling as an analytic strategy, as this would allow us to focus more particularly on patterns of within-person change as a function of condition. No effects or interactions involving age or gender were present, indicating that the anger induction operated similarly for all participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | |||||||||

| 2. Gender | −.04 | -- | ||||||||

| 3. Anger - Initial exposure | .05 | .02 | -- | |||||||

| 4. Anger - Regulation | .05 | .01 | .53*** | -- | ||||||

| 5. Anger - Immediate reexposure | .04 | .00 | .64*** | .55*** | -- | |||||

| 6. Anger - Delayed reexposure | −.02 | .07 | .64*** | .40*** | .65*** | -- | ||||

| 7. Psychological elaboration | .36*** | −.27** | .14 | .10 | .00 | .09 | -- | |||

| 8. Exploratory processing | .40*** | −.20* | .09 | .02 | .01 | .10 | .70*** | -- | ||

| 9. Positive meaning | .04 | −.02 | −.06 | −.13 | −.09 | −.07 | .21* | .29** | -- | |

| 10. Resolution | −.02 | .07 | −.26** | −.20* | −.22* | −.20* | .06 | .04 | .38*** | -- |

|

| ||||||||||

| Mean | 12.62 | 1.49 | 2.50 | 1.90 | 2.42 | 2.26 | 1.72 | 1.59 | 0.19 | 1.97 |

| SD | 2.86 | 0.50 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.10 | 0.40 | 0.63 |

Notes. Variables 1–6 are for participants in all conditions, and sample sizes among bivariate correlations for these variables range from 235 to 241. Variables 7–10 are for participants in the narration condition only, and sample sizes for bivariate correlations involving these variables range from 111 to 114. Gender is coded as 1 = female, 2 = male.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Most participants focused on events involving relational incidents (71%); although anger related to physical (13%) and material (16%) harm were infrequent, younger participants were more likely to focus on events involving physical harm, χ2 (18) = 39.6, p = .002, and boys were more likely than girls to focus on physical or material harm, χ2 (2) = 14.6, p = .001. Most participants focused on anger against friends/peers (47%) and siblings (26%); there were no age or gender differences in the target of anger (ps >.30). Most importantly, there were no differences among regulation conditions in the type or target of anger recalled. Additional preliminary analyses were conducted to assess whether participants recalled angry events that varied in the time elapsed since the event, in the perceived event’s importance, or in the extent of the event’s prior narration, in ways that were confounded with condition, age, or gender. A GLM revealed no effects of condition, but did reveal significant multivariate effects of age, F(3, 231)=6.26, p<.001, ηp2=.075, and gender, F(3, 231)=6.44, p<.001, ηp2=.077. Univariate tests revealed that the effect of age was primarily due to prior narration, F(1, 233)=13.93, p<.001, ηp2=.056, and time since event, F(1, 233)=4.97, p=.027, ηp2=.021. Older participants focused on events that occurred longer ago, r=.143, p=.027, and reported more prior narration of the event to others, r=.246, p<.001. Univariate tests indicated that the effect of gender was primarily due to prior narration, F(1, 233)=15.89, p<.001, ηp2=.064. Girls reported significantly more prior narration about the event than did boys (EMM(SEM)girls=3.08(.12); EMM(SEM)boys=2.41(.13). Although these findings indicate that there were some variations in the angry events recalled by boys compared to girls and by youth of different ages, neither time since event nor prior narration was associated with self-reports of anger (rs < .17). Therefore, we did not further consider any of these variables in our analyses.

Does Narration Help Youth Reduce Anger Better than Distraction or Reexposure?

Table 2 shows descriptive data for anger ratings for each epoch, separately by condition. To address whether narration helps youth down-regulate anger, we used multilevel modeling, with the level 1 model predicting anger reports from epoch (initial exposure, regulation, immediate reexposure, and delayed reexposure), and the level 2 model assessing the impact of experimental condition on the effects of epoch. We also examined whether the effects of condition were moderated by age and gender. For epoch, we modeled both linear and quadratic effects, given that we expected participants in the distract conditions to show declines in anger followed by rebounds. At level 2, we employed standard dummy coding of the condition effects, with the reexposure-control condition as the default comparison condition. An alpha level of .05 was employed for all hypotheses tested.

Table 2.

Anger Rating Means (Standard Deviations) by Epoch and Regulation Condition

| Regulation Condition | Anger at Initial Exposure | Anger at Regulation | Anger at Immediate Reexposure | Anger at Delayed Reexposure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reexposure Control | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.2) |

| Narration | 2.5 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Distract-Talk | 2.1 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.3) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Distract-Game | 2.7 (1.0) | 1.4 (0.7) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.5 (0.9) |

The final model with robust standard errors is presented in Table 3. In the reexposure-control condition, represented by the intercepts, there were no overall linear or quadratic effects of epoch on anger ratings. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the significant negative intercept effect for the distract-talk condition indicates that youth assigned to this condition were less angry than those assigned to the reexposure-control condition during initial exposure, and contrasts showed this was also the case when youth in the distract-talk condition were compared to those in the narration and distract-game conditions (ps<.002); these results are consistent with the preliminary analyses reported earlier.

Table 3.

Multilevel Modeling of the Effects of Regulation Condition, Age, and Gender on Changes in Anger; Final Model with Robust Standard Errors

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | t(df), p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept (anger at initial exposure) | ||

| Intercept (reexposure-control) | 2.73 (.16) | t(228) = 16.7, p < .001 |

| Narration vs. control | −.30 (.19) | t(228) = −1.6, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control | −.80 (.20) | t(228) = −4.0, p < .001 |

| Distract-game vs. control | −.23 (.21) | t(228) = −1.1, p = ns |

| Age | −.04 (.06) | t(228) = −.7, p = ns |

| Gender | .38 (.31) | t(228) = 1.2, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Age | .05 (.07) | t(228) = 0.7, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Age | .11 (.08) | t(228) = 1.3, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Age | .08 (.07) | t(228) = 1.1, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Gender | −.57 (.36) | t(228) = −1.6, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Gender | −.45 (.39) | t(228) = −1.2, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Gender | .04 (.40) | t(228) = 0.1 , p = ns |

| Linear Change in Anger | ||

| Intercept (reexposure-control) | .21 (.17) | t(691) = 1.2, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control | −.44 (.20) | t(691) = −2.2, p = .027 |

| Distract-talk vs. control | −.74 (.20) | t(691) = −3.7, p < .001 |

| Distract-game vs. control | −1.21 (.23) | t(691) = −5.3, p < .001 |

| Age | .02 (.06) | t(691) = .3, p = ns |

| Gender | −.05 (.34) | t(691) = .2, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Age | .02 (.07) | t(691) = .0, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Age | .00 (.08) | t(691) = −.5, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Age | −.04 (.08) | t(691) = −.1, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Gender | −.01 (.39) | t(691) = −.3, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Gender | −.13 (.39) | t(691) = −.3, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Gender | −.13 (.44) | t(691) = −.5, p = ns |

| Quadratic change in Anger | ||

| Intercept (reexposure-control) | −.08 (.06) | t(691) = −1.4 p = ns |

| Narration vs. control | .13 (.07) | t(691) = 1.9 p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control | .29 (.07) | t(691) = 4.3, p < .001 |

| Distract-game vs. control | .44 (.07) | t(691) = 6.0, p < .001 |

| Age | −.01 (.02) | t(691) = −.3, p = ns |

| Gender | −.04 (.11) | t(691) = −.4, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Age | −.00 (.02) | t(691) = −.0, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Age | .01 (.03) | t(691) =.3, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Age | −.01 (.03) | t(691) = −.3, p = ns |

| Narration vs. control x Gender | .12 (.13) | t(691) = 1.0, p = ns |

| Distract-talk vs. control x Gender | .07 (.13) | t(691) =.5, p = ns |

| Distract-game vs. control x Gender | .04 (.14) | t(691) =.3, p = ns |

Note. ns = not significantly different from zero at p < .05.

Significant linear declines in anger were evident for all three regulation conditions (see Tables 2 and 3). Contrast tests showed that these linear declines were markedly larger for the two distract conditions than for the narration condition, and the distract-game condition also led to sharper declines than did the distract-talk condition (ps<.034). However, significant quadratic rebounds were also evident for the two distract conditions, and contrast tests showed that the quadratic rebound was larger for distract-game than for distract-talk (p=.012).

Altogether, findings show that narration and distraction serve to reduce anger during the regulation epoch (see Tables 2 and 3). Distraction, however, results in only temporary reductions in anger, as shown by the significant quadratic rebound. Narration produces a smaller quadratic rebound that did not attain statistical significance. Contrary to our hypotheses, there were no age differences in the effects of narration (there were also no age differences in the effects of distraction). Further, there were no gender differences in these effects.

Do Features of the Narrative Matter for Reducing Anger?

For these analyses, we focused on the 114 youth who were assigned to the narration condition, and examined relations between the features of youth’s narratives and their anger ratings across epochs. We also tested whether these links were moderated by age or gender.

Preliminary examination of narrative features, age, and gender

Table 1 shows associations between narrative features, gender, and age. Age was positively linked to indicators of psychological elaboration and exploratory processing (ps<.001). A series of t-tests showed that gender was linked to psychological elaboration (p=.003) and exploratory processing (p=.030), with girls showing more psychological elaboration and exploratory processing than boys. Age and gender were not related to positive meaning-making or resolution. These findings largely replicate previous work (Fivush et al., 2000; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010), and underscore the importance of including age and gender in analyses of effects of narrative quality.

Multilevel modeling of anger ratings as a function of narrative features

To examine the effects of narrative features on anger, we used multilevel modeling of anger ratings with epoch at level 1, and age, gender, and narrative features at level 2. Our model also included all two-way interactions of gender and narrative features, and all two-way interactions of age and narrative features; variables were centered prior to computing interaction terms. Initial analyses showed that when the narration condition is examined on its own, there were no quadratic effects of epoch, so we included only a linear effect of epoch in these analyses.

Results of this model are depicted in Table 4. As shown, resolution was significantly and negatively related to the intercept for anger, indicating that youth whose narratives depicted higher levels of resolution reported lower levels of anger at initial exposure. Overall, there were significant linear declines in anger across epochs, as indicated by the intercept for the epoch effect. Gender significantly moderated this effect; girls benefited more from narrating than did boys, as their linear declines in anger were steeper. There were no significant main effects of any of the narrative features on the extent of linear decline, nor were there any significant interactions involving gender. However, there was a significant interaction of age with positive meaning-making in relation to the intercept, and three significant interactions of age and narrative features with respect to the slope of linear decline in anger across the study (see Table 4). These involved psychological elaboration, exploratory processing, and positive meaning-making, respectively. Note that although psychological elaboration and exploratory processing are highly correlated, they are conceptually distinct and interact with age in opposite directions. Analyses examining possible suppression effects suggest that results involving exploratory processing are attributable to the variation in exploratory processing that is distinct from the shared variation with psychological elaboration.

Table 4.

Multilevel Model Predicting Anger Ratings from Narrative Features; Narrate Participants Only

| Variable | Coefficient (SE) | t(df), p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept (df = 98) | ||

| Intercept (anger at initial exposure) | 2.48 (.11) | t(98) = 23.6, p < .001 |

| Psychological elaboration | .16 (.14) | t(98) = 1.2, p = ns |

| Exploratory processing | .01 (.11) | t(98) = .1, p = ns |

| Positive meaning-making (bivariate) | −.16 (.20) | t(98) = −.8, p = ns |

| Resolution | −.32 (.15) | t(98) = −2.01, p = .039 |

| Gender | −.11 (.20) | t(98) = −.6, p = ns |

| Age | −.03 (.04) | t(98) = −.8, p = ns |

| Psychological elaboration x gender | .09 (.24) | t(98) = .4, p = ns |

| Exploratory processing x gender | .39 (.23) | t(98) = 1.7, p = ns |

| Positive meaning-making x gender | −.18 (.43) | t(98) = −.4, p = ns |

| Resolution x gender | .03 (.30) | t(98) = .1, p = ns |

| Psychological elaboration x age | −.01 (.05) | t(98) = −.2, p = ns |

| Exploratory processing x age | −.01 (.04) | t(98) = −.3, p = ns |

| Positive meaning-making x age | .16 (.08) | t(98) = 2.0, p = .045 |

| Resolution x age | −.04 (.07) | t(98) = −.5, p = ns |

| Linear Change in Anger (df = 321) | ||

| Intercept | −.11 (.04) | t(321) = −3.1, p = .002 |

| Psychological elaboration | −.05 (.04) | t(321) = −1.2, p = ns |

| Exploratory processing | .04 (.03) | t(321) = 1.2, p = ns |

| Positive meaning-making (bivariate) | .02 (.07) | t(321) = 0.2, p = ns |

| Resolution | .01 (.04) | t(321) = 0.2, p = ns |

| Gender | .14 (.06) | t(321) = 2.4, p = .015 |

| Age | .01 (.01) | t(321) = 1.0, p = ns |

| Psychological elaboration x gender | .04 (.06) | t(321) =.6, p = ns |

| Exploratory processing x gender | −.08 (.06) | t(321) = −1.4, p = ns |

| Positive meaning-making x gender | −.01 (.12) | t(321) = −.1, p = ns |

| Resolution x gender | −.02 (.08) | t(321) = −.3, p = ns |

| Psychological elaboration x age | .03 (.01) | t(321) = 2.2, p = .026 |

| Exploratory processing x age | −.02 (.01) | t(321) = −2.0, p = .043 |

| Positive meaning-making x age | −.07 (.03) | t(321) = −2.8, p = .006 |

| Resolution x age | .02 (.02) | t(321) = 1.2, p = ns |

Note. ns = not significantly different from zero at p < .05.

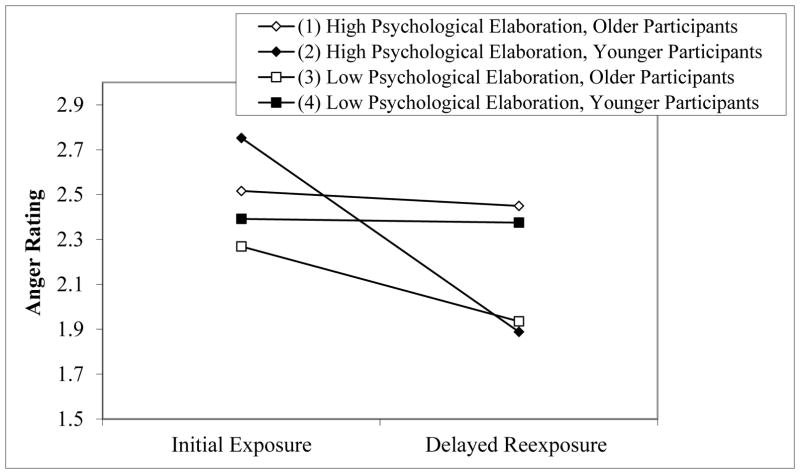

We probed these interactions using online utilities and simple slopes analyses (Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006) for younger (mean − 1 SD) and older (mean + 1 SD) participants, whose narratives were low (mean − 1 SD) or high (mean + 1 SD) in each respective narrative feature. Psychological elaboration, exploratory processing, and positive meaning-making were each associated with the extent of declines in anger, but in distinct ways depending on the age of participants. As shown in Figure 1, for younger participants, those who told narratives with more psychological elaboration showed larger reductions in anger (b=−.289, p=.024), as compared to those who told narratives with less psychological elaboration (b=−.006, p=.933). For older participants, using less psychological elaboration was related to steeper declines in anger (b=−.112, p=.007), and using more psychological elaboration was unrelated to declines in anger (b=−.022, p=.649). As shown in Figure 2, younger participants who told narratives with low exploratory processing showed larger reductions in anger (b=−.249, p=.002), as compared to those who told narratives with more exploratory processing (b=−.041, p=.676). By contrast, older participants whose narratives entailed more exploratory processing reported steeper declines in anger (b=−.094, p=.010) as compared to those who told narratives with less exploratory processing (b=−.042, p=.410). Finally, as shown in Figure 3, older participants whose narratives contained positive meanings showed steeper declines in anger over the course of the study (b=−.260, p<.001), whereas younger participants’ use of positive meaning making was unrelated to declines in anger (b=.077, p=.445). In fact, for younger participants, the absence of positive meanings was associated with declines in anger (b=−.146, p=.034). As Figure 3 also shows, there was a significant interaction of age and positive meaning-making for the intercept, suggesting that anger at initial exposure was associated with the presence of positive meaning-making in ways that varied with age. Simple slopes analyses suggest that positive meaning-making was associated differently with anger at initial exposure for older (b=.299, p=.232), compared to younger participants (b=−.603, p=.081), but in neither case was that association significant.

Figure 1.

Psychological elaboration and declines in anger over the course of the study, for younger versus older participants

Figure 2.

Exploratory processing and declines in anger over the course of the study, for younger versus older participants

Figure 3.

Positive meaning and declines in anger over the course of the study, for younger versus older participants

Discussion

The study’s goals were twofold: First, we examined the effectiveness of narration in reducing anger among children and adolescents. Given that youth commonly engage in distraction to regulate their emotions, and may prefer distraction to narration, we compared narration to two forms of distraction, as well as to a reexposure-control condition. Second, we examined whether features of youth’s narratives were associated with the effectiveness of narration for anger reduction, and whether such associations varied with youth’s age or gender.

Our findings suggest that narration is effective at reducing youth’s anger both concurrently and in more lasting ways, when compared to mere reexposure. Narration is less effective than distraction at concurrently reducing anger but its effect is longer lasting, whereas distraction provides no lasting reductions in anger regardless of whether it involves focusing on a positive experience or playing a video game. There were no age differences in the relative effectiveness of narration for anger reduction across the age range of our sample, despite well-documented age differences in narrative quality in the literature (Habermas & de Silveira, 2008; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010), and in the present study. Likewise, we also did not see any gender differences in the relative effectiveness of narration for anger reduction.

Distraction Works While Youth Do It

As expected, distraction was effective at reducing anger, but only while youth were distracting themselves. Importantly, our examination of distraction focused on activities that may provide some benefits, in contrast to distraction strategies that involve substance use or other harmful tactics (Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011). For example, narrating a positive experience to a responsive listener reminds youth of the good experiences and builds a social connection to another person, which might be especially helpful following a distressing experience (McCullough, 2002). Playing a video game addresses the distressing experience less directly, but offers the possibility for respite, and even “flow” experiences (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Although not the case in our study, many games also offer social connections and engagements; thus, comparisons of different forms of distraction represent an important arena for future work.

Narration Works for All Ages, but Perhaps via Different Processes

The absence of age differences in the relative effectiveness of narration was unexpected. Given well-documented differences in narrative quality across this age range (e.g., Habermas & de Silveira, 2008; Pasupathi & Wainryb, 2010), a lack of age differences in the relative efficacy of narration raises the possibility that the features that are associated with adaptive emotional outcomes in adults do not work similarly for youth. This idea was indeed borne out by our second set of findings.

Analyses within the narration sample yielded the expected age differences in narrative quality. However, these features did not predict reductions in anger on their own, but only in ways moderated by participants’ age. Specifically, among older youth, like among adults, more extensive exploratory processing and the presence of positive meaning-making were associated with steeper declines in anger. While it is not surprising that exploratory processing and positive meanings have beneficial effects on emotion, these findings are important in that they suggests that this route for regulating emotion is evident beginning in mid- to later adolescence—an assumption that had received only mixed support in previous work (McLean & Breen, 2009; McLean et al., 2010; Reese et al., 2010; Soliday et al., 2004; Styer & Baker-Ward, 2013). Notably, however, adolescents in our study were also distinct from adults, in that adult narratives associated with positive outcomes typically also depict the event as resolved (Pasupathi et al., 2015, 2017), but in our sample, even among our older participants, resolution was unrelated to declines in anger. Instead, our findings indicated that resolution was negatively associated to the intercept for anger, which in turn suggests that resolution in the youth narratives may reflect coping processes that took place prior to youth’s participation in the study.

Children and early adolescents in our sample were even more distinct from adults in the ways narration appeared to help with emotion regulation. For these younger youth, more extensive exploratory processing and the presence of positive meaning-making were unrelated to anger reduction. Indeed, for these younger participants, declines in anger required that their narratives include less exploratory processing and positive meanings, and more psychological elaboration. Although clearly different from what is known about adults, this finding is not entirely surprising in two respects.

First, this finding is consistent with narrative work suggesting that, in the narratives of preadolescents, positive meanings are often associated with less wellbeing (Fivush et al., 2007; McLean et al., 2010; Styers & Baker-Ward, 2013). Although this has been puzzling to researchers, we speculate that the inclination to independently draw meaning from negative or distressing events may be less organic or authentic in childhood, perhaps because this type of meaning-making is more relevant for people whose time horizon on events is longer; therefore, the presence of more meaning-making language in young youths’ narratives may reflect unsuccessful efforts after meaning.

Furthermore, psychological elaboration, which indexes the extent to which the narrator’s internal experience is represented in a narrative, captures the degree to which the child narrator considers — rather than avoids or suppresses — her or his thoughts, feelings, and beliefs about a specific experience. Such elaboration is sometimes conceptualized as mentalization, which has been shown to be positively associated with the adaptive regulation of emotions (e.g., Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, 2002). Moreover, the capacity to elaborate psychological aspects of experience lays a foundation for the kind of exploratory processing and positive meaning-making that are effective for regulating emotion later in development.

Narration May Work Differently for Boys and Girls

In our first set of analyses, which compared narration to distraction and reexposure, we did not see gender differences in the effectiveness of narration relative to the other strategies. However, when we looked only within the narration condition, we found that girls, as expected, told more psychologically elaborated narratives with more extensive exploratory processing (e.g., Fivush, Marin, McWilliams & Bohanek, 2009). As with prior work, girls did not do more positive meaning-making and did not resolve their narratives more than boys (McLean & Breen, 2009). Further, we observed a main effect of gender on the steepness of declines in anger across the study, suggesting that within the narration condition, girls did benefit more from narration than boys in terms of anger reduction. The discrepancy in these two sets of gender-related findings may arise from the fact that gender differences in anger reduction within the narration condition were small, relative to the large differences among distraction, narration, and reexposure in the overall sample. Altogether, our findings do suggest that girls are likely benefitting more from narration, in terms of anger reduction, than are boys.

Our data also show the expected gender differences in narrative features, consistent with the idea that girls have more capacity for high-quality narration, perhaps based on differences in the socialization of narration (Fivush et al., 2000; McLean & Mansfield, 2012). However, those gender differences in narrative quality did not account for gender differences in the effectiveness of narrative for anger reduction – given that gender differences in the effectiveness of narration emerged when narrative features were included in the models, and there were no gender by narrative feature interactions with the features we assessed. Thus, gender differences in anger reduction were evident, independent of gender differences in narrative quality, and gender did not moderate effects of narrative quality in the way we observed for age. This means that to the extent that narration works better for girls at reducing anger, the processes by which that gender difference in effectiveness comes about remain unknown.

Limitations

With all work on autobiographical event narration, researchers have limited control over variations in the events recalled by participants. For example, in our data, participants randomly assigned to the distract-talk condition happened to recall less intense anger experiences; fortunately for our experiment, that intensity gap was consistent across all phases of the study. However, this serves as a reminder that every group in the study consisted of individual children recalling varied experiences of anger. In some ways, this makes the experimental findings more remarkable, and more generalizable.

A second limitation is that we employed a series of single-item ratings of anger to capture youths’ anger regulation. While this choice was made in order to limit participant burden and to more tightly focus the participant on anger, single-item measures have some limitations in terms of psychometric properties. That said, work with adults (e.g., MacNamara et al., 2011; Pasupathi et al., 2017; Ray et al., 2008) and youth (Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001; Scott, Morgan, Plotnikoff, & Lubans, 2015) has established the validity of single item ratings and recent work has established that single-item ratings can be viable measurement approaches when burden is a concern (Woods & Hampson, 2005). Further, it bears underscoring that although each anger-rating in the study was made as a single-item, this measurement was employed in a within-subjects manner, examining the linear trajectories in those same ratings over multiple measurements and two experimental sessions. Finally, and as noted earlier, our measures of anger were not correlated with measures of psychophysiological arousal; importantly, this cannot be taken as an indication of the lack of validity of the self-report measures. Measures of psychophysiological arousal tap general arousal that can be associated with distress, but can also be associated with positively perceived cognitive challenges; thus, it is not unusual for self-report measures of emotional states to be unrelated to psychophysiological measures (Mauss, 2005), nor is it valid to assume that the psychophysiological measures have priority over self-reports.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite these limitations, the present findings are uniquely promising inasmuch as they represent a portable and ecologically valid intervention for aiding youth in anger regulation. Further, our findings suggest that narrating may be more effective for lasting anger reductions among youth than it is among adults, where narrating did not necessarily result in lasting reductions in anger (Pasupathi et al., 2017). It is possible that the difference in effectiveness is due to differences in the intensity of anger experiences recalled by adults and youth: our youth participants reported significant increases in anger on recalling their angry memory, but those increases were somewhat lower in magnitude than increases reported by adults in similar studies (Pasupathi et al., 2017; Ray et al., 2008). An alternative explanation is that youth memory may be more malleable than that of adults. Eyewitness and forensic research, focused on the accuracy and completeness of memories, demonstrates that susceptibility to memory suggestion peaks around 5–6 years of age, although even adults remain somewhat suggestible (Crossman, Scullin, & Melnyk, 2004). If youth memory is somewhat more malleable than adult memory, this could account for the longer-lasting effects of one-time narration among youth. Understanding the difference in the lasting effectiveness may be one important issue for future work, inasmuch as explanations invoking anger intensity imply some limits on the effectiveness of narration for youth.

Regardless, narration is clearly effective for reducing anger in relation to everyday experiences among youth. How, then, might we promote youth narration of anger – and particularly, narration that contains the key, age-appropriate effective ingredients for reducing distress? Attentive listeners promote elaboration and meaning-making for people of all ages (e.g., Nils & Rimé, 2012). For children and younger adolescents, it is important that listeners also scaffold psychological elaboration in ways that are developmentally appropriate if the goal is to reduce distress (Fivush & Nelson, 2004; Recchia et al., 2014; Reese et al., 2010). It may be that psychological elaboration is sufficient to benefit emotion in this age group because it functions as a kind of anti-suppression. For mid- and older adolescents, it is important for listeners to help promote more self- and identity-related narration via exploratory processing and positive meaning-making. For adolescents, such scaffolding may require particular sensitivity, given that scaffolding meaning-making may create tensions with youth’s needs for autonomy (Recchia & Wainryb, 2014). While a more nuanced and age-appropriate understanding of the ways that listeners can help youth is needed, researchers in this arena have extensive literatures on which they can draw, both developmental (e.g., Fivush & Nelson, 2004; Recchia et al., 2014; Reese et al., 2010) and social psychological (e.g., Pasupathi, 2001).

But youth do not always narrate their experiences to others, and across the age range of our sample youth’s listener choices slowly expand to include peers and romantic partners (Hartup & Stevens, 1997). These issues raise additional and important developmental questions, to be explored in future research, concerning the factors that influence whether, how, and to whom youth of different ages choose to narrate their distressing experiences, as well as the varied impact of peers, versus adults, as listeners on narrative regulation of distress.

Beyond merely reducing anger and other forms of distress, and doing so in more lasting ways, narration offers other significant opportunities for youth to learn about themselves and their worlds. Inasmuch as narrative construction for all ages requires people to place a set of events in a broader psychological context, in which involved people think, want, act, and feel in psychologically meaningful ways, narration is linked to more than simply reductions of distress. Rather, it is related to making sense of oneself and others. For younger children, this sense-making may be relatively constrained to the particulars of specific events and the psychological states of those involved, while as youth become more capable of thinking over longer time-horizons, sense-making expands to include self and identity related contents. Overall, the present findings lend strong support to the potential for narration to help youth manage anger experiences in ways that can reduce distress, and open new frontiers for exploring how youth can capitalize on the benefits of narration for broader learning about themselves and their relational worlds.

References

- Band E, Weisz J. How to feel better when it feels bad: Children's perspectives on coping with everyday stress. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:247–253. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.2.247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohanek J, Marin K, Fivush R. Family narratives, self, and gender in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin T, Aldao A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2013;139:735–765. doi: 10.1037/a0030737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole P, Tan P, Hall S, Zhang Y, Crnic K, Blair C, Li R. Developmental changes in anger expression and attention focus: Learning to wait. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1078–1089. doi: 10.1037/a0023813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas B, Jaser S, Bettis A, … Thigpen J. Psychological Bulletin. 2017. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossman A, Scullin M, Melnyk L. Individual and developmental differences in suggestibility. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2004;18:941–945. doi: 10.1002/acp.1079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. NY: Harper; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings H, Vandewater E. Relation of adolescent video game play to time spent in other activities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:684–689. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E, Levine L, Lench H, Quas J. Metacognitive emotion regulation: Children's awareness that changing thoughts and goals can alleviate negative emotions. Emotion. 2010;10:498–510. doi: 10.1037/a0018428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis T, Kelemen D. Preschool children’s views on emotion regulation: Functional associations and implications for social-emotional adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:243–252. doi: 10.1177/0165025408098024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavioral Research Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C, Olson C. Friends, fun, frustration and fantasy: Child motivations for video game play. Motivation and Emotion. 2013;37:154–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Brotman M, Buckner J, Goodman S. Gender differences in parent-child emotion narratives. Sex Roles. 2000;42:233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Berlin L, Sales J, Mennuti-Washburn J, Cassidy J. Functions of parent-child reminiscing about emotionally negative events. Memory. 2003;11:179–192. doi: 10.1080/741938209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Marin K, Crawford M, Reynolds M, Brewin C. Children's narratives and well-being. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21:1414–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Marin K, McWilliams K, Bohanek JG. Family reminiscing style: Parent gender and emotional focus in relation to child well-being. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2009;10(3):210–235. doi: 10.1080/15248370903155866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fivush R, Nelson K. Culture and language in the emergence of autobiographical memory. Psychological Science. 2004;15:586–590. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist E, Target M. Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of self. London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gerin W, Davidson K, Christenfeld N, Goyal T, Schwartz J. The role of angry rumination and distraction in blood pressure recovery from emotional arousal. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:64–72. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195747.12404.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Richards J, John O. Emotion regulation in daily life. In: Snyder D, Simpson J, Hughes J, editors. Emotion regulation in families: Pathways to dysfunction and health. Washington DC: APA; 2006. pp. 13–35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Thompson R. Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Reese E. Getting a life takes time: The development of the life story in adolescence, its precursors and consequences. Human Development. 2015;58:172–201. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, de Silveira C. The development of global coherence in life narratives across adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:707–721. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel P, Petermann F. Age and gender effects on coping in children and adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2005;34:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-3207-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup W, Stevens N. Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Schneider B. Anger expression in children and adolescents: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:559–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kober C, Schmiedek F, Habermas T. Characterizing lifespan development of three aspects of coherence in life narratives: A cohort-sequential study. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:260–275. doi: 10.1037/a0038668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Ayduk O. Facilitating adaptive emotional analysis: Distinguishing distanced-analysis of depressive experiences from immersed-analysis and distraction. Personality and Social Psychology Bull. 2008;34:924–938. doi: 10.1177/0146167208315938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson R. The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition & Emotion. 1999;13:481–504. doi: 10.1080/026999399379159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levine L, Prohaska V, Burgess S, Rice J, Laulhere T. Remembering past emotions: The role of current appraisals. Cognition and Emotion. 2001;15:393–417. [Google Scholar]

- Lilgendahl J, McAdams D. Constructing stories of self-growth: How individual differences in patterns of autobiographical reasoning relate to well-being in midlife. Journal of Personality. 2011;79:391–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNamara A, Ochsner K, Hajcak G. Previously reappraised: The lasting effect of description type on picture-elicited electrocortical activity. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2011;6:348–358. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss I, Levenson R, McCarter L, Wilhelm F, Gross J. The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion, experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion. 2005;5:175–190. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough M. Savoring life, past and present: Explaining what hope and gratitude share in common. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:302–304. [Google Scholar]

- McLean K, Breen A. Processes and content of narrative identity development in adolescence: Gender and well-being. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:702–710. doi: 10.1037/a0015207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K, Breen A, Fournier M. Constructing the self in early, middle, and late adolescent boys: Narrative identity, individuation, and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:166–187. [Google Scholar]

- McLean K, Mansfield C. The co-construction of adolescent narrative identity: Narrative processing as a function of adolescent age, gender, and maternal scaffolding. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:436–447. doi: 10.1037/a0025563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean K, Pasupathi M, Pals J. Selves creating stories creating selves: A process model of self-development. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2007;11:262–278. doi: 10.1177/1088868307301034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullin B, Hinshaw S. Emotion regulation and externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. In: Gross J, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. NY: 2007. pp. 523–542. [Google Scholar]

- Nils F, Rimé B. Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine the benefits of emotional disclosure. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;42:672–681. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51:704–708. [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner K, Gross J. Cognitive emotion regulation: Insights from social cognitive and affective neuroscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M. The social construction of the personal past and its implications for adult development. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:651–672. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Billitteri J, Mansfield C, Wainryb C, Hanley G, Taheri K. Regulating emotion and identity by narrating harm. Journal of Research in Personality. 2015;58:127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Wainryb C. On telling the whole story: Facts and interpretations in autobiographical memory narratives from childhood through midadolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:735–746. doi: 10.1037/a0018897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasupathi M, Wainryb C, Mansfield C, Bourne S. The feeling of the story: Narrating to regulate anger and sadness. Cognition and Emotion. 2017;31:444–461. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1127214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Curran P, Bauer D. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Wilhelm F, Gross J. All in the mind's eye? Anger rumination and reappraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;94:133–145. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchia H, Wainryb C. Mother-child converseations about hurting others: Supporting the construction of moral agency through childhood and adolescence. In: Wainryb C, Recchia H, editors. Talking about right and wrong. Cambridge: 2014. pp. 242–269. [Google Scholar]

- Recchia H, Wainryb C, Bourne S, Pasupathi M. The construction of moral agency in mother-child conversations about helping and hurting across childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:34–44. doi: 10.1037/a0033492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Myftari E, McAnally H, Chen Y, Neha T, Wang Q, Jack F, Robertson S. Telling the tale and living well: Adolescent narrative identity, personality traits, and well-being across cultures. Child Development. 2016;88:612–628. doi: 10.1111/sdev.12618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese E, Yan C, Jack F, Hayne H. Emerging identities: Narrative and self from early childhood to early adolescence. In: McLean K, Pasupathi M, editors. Narrative development in adolescence. NY: Springer; 2010. pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Robins R, Hendin H, Trzesniewski K. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:151–161. [Google Scholar]