Abstract

The dynamical organization of membrane-bound organelles along intracellular transport pathways relies on vesicular exchange between organelles and on the maturation of the organelle’s composition by enzymatic reactions or exchange with the cytoplasm. The relative importance of each mechanism in controlling organelle dynamics remains controversial, in particular for transport through the Golgi apparatus. Using a stochastic model, we identify two classes of dynamical behavior that can lead to full maturation of membrane-bound compartments. In the first class, maturation corresponds to the stochastic escape from a steady state in which export is dominated by vesicular exchange, and is very unlikely for large compartments. In the second class, it occurs in a quasi-deterministic fashion and is almost size independent. Whether a system belongs to the first or second class is largely controlled by homotypic fusion.

Introduction

The hallmark of eukaryotic cells is their compartmentalization into specialized organelles defining different biochemical environments within the cell. These compartments are bounded by a fluid lipid membrane and are highly dynamical, constantly exchanging components with one another through the budding and fusion of small transport vesicles (1). The presence of different combinations of lipids and proteins in the membrane of different organelles defines different membrane identities and direct vesicular exchange by controlling the activity of membrane-associated proteins, such as coat proteins that drive vesicle budding, and tethers and SNAREs that control vesicle fusion (2, 3). This is required for the existence of well-defined intracellular transport pathways, such as the endocytic pathways, from the cell plasma membrane to early endosomes and late endosomes (4), and the secretory pathway, from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the Golgi apparatus and the trans-Golgi network (5).

Members of the Rab GTPase family play an important role in defining the membrane identity and regulate all steps of membrane traffic (6, 7, 8, 9). In particular, Rabs are involved in homotypic fusion—the propensity of a vesicle to fuse with a compartment of similar identity, a process relevant for the spatio-temporal organization of both the endosomal network (10) and the Golgi apparatus (11). Remarkably, the membrane identity of an organelle can change over time in a process called maturation. Maturation has been observed in the endosomal network, where Rab5 positive early endosomes mature into Rab7 positive late endosomes over a timescale on the order of 10 min (10). It has also been observed in the Golgi apparatus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In this organism, the Golgi subcompartments, called cisternae, are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm and can be seen to mature from a cis (i.e., early) to a trans (i.e., late) identity in ∼1–2 min (12, 13).

Vesicular export from early to late compartments and the biochemical maturation of early compartments into late compartments constitute two distinct mechanisms allowing progression along secretory and endocytic pathways, raising a fundamental question as to their relative importance for intracellular trafficking. In other words, are organelles steady-state structures receiving, processing, and exporting transiting cargoes, or are they transient structures that are nucleated by an incoming flux and undergo full maturation (see Fig. 1 for a sketch)? This question is particularly debated for the Golgi apparatus. In most animal and plant cells, it is made of individual compartment (cisternae), stacked together in a polarized way with an entry (cis) face and an exit (trans) face. Whether Golgi transport occurs by intercisternal vesicular exchange or by full cisternal maturation is still highly controversial (14). This question is of high physiological relevance considering the involvement of Golgi dysfunction in many pathologies, including Alzheimer and cancers (15, 16, 17, 18, 19).

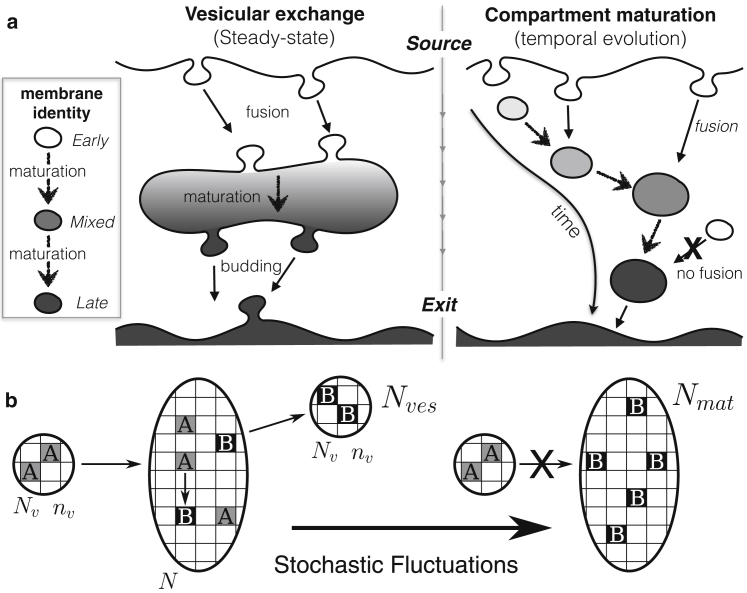

Figure 1.

(a) Sketch of the possible dynamics of an organelle receiving a vesicular influx of early (white) membrane identity undergoing maturation into late (dark) identity inside the organelle and being exported by vesicular budding. The organelle could represent an early endosome, for which the source is the plasma membrane and the exit the pool of late endosomes, or the Golgi apparatus, for which the source is the ER and the exit the trans Golgi network. The organelle can be at steady state (vesicular exchange, left) where the influx of immature vesicles is balanced by an outflux of mature vesicles, or show a progressive evolution from an early to a late identity (compartment maturation, right), where the influx is balanced by an outflux of mature compartments. (b) Sketches of the theoretical model: incoming and outgoing vesicles contain Nv sites including nv immature (A, gray) or mature (B, black) components, respectively. The fusion of incoming vesicles requires the presence of A sites in the compartment. Stochastic fluctuations lead to full maturation and the isolation of the compartment from the influx, after which a new compartment is created de novo.

Beyond the case of the Golgi apparatus, the interplay between biochemical maturation and vesicular exchange in cellular transport pathways is an issue relevant for many aspects of intracellular organization, and we currently lack a quantitative framework to address it. Several physical models of intracellular transport have been developed in recent years (20, 21, 22, 23). These studies generally focus on steady-state properties, and the inherently stochastic nature of intracellular transport has been much less explored (24, 25). Stochasticity should, however, play an important role, as the fusion/budding of a few tens of vesicles (of diameter ∼50–100 nm) is enough to completely renew the membrane composition of an endosome or a Golgi cisterna (of area ∼0.2–0.5 μm2). This explains the strong fluctuation of the size and composition of early endosomes (10).

We investigate theoretically a stochastic, one-compartment model (sketched in Fig. 1) that includes both aspects of organelle dynamics. Immature membrane components are injected by the fusion of incoming vesicles, undergo biochemical maturation, and are exported by vesicular budding. We precisely quantify whether the outflux of mature components predominantly occurs by vesicular export from a steady-state compartment of fixed biochemical identities or by the full maturation of the entire compartment. Our model, which is investigated both analytically and with numerical simulations, is an application of the theory of birth-and-death stochastic processes, which are used to a great extent in many areas of biology (26) and population dynamics (27). It establishes the importance of stochasticity in controlling the balance between vesicular exchange and compartment maturation and identifies the key control parameters as being the ratio of vesicle injection to budding rate, and the ratio of biochemical maturation to budding rates.

Methods

We consider a membrane-bound compartment receiving a vesicular influx of components of a given (early) identity called A which, after being converted into a late identity B by a maturation process, exits the compartment by selective vesicle budding (Fig. 1 b). At steady state, the vesicular influx of immature components is entirely converted into vesicular outflux of mature components, which corresponds to the vesicular exchange mechanism. In practice, however, one expects that stochastic fluctuations around the steady state, which will be comparatively more important for small compartments, eventually lead to the full maturation of all A sites into the B identity. Homotypic fusion makes it unlikely that a vesicle of immature identity A will fuse with a fully mature compartment of B components. To account for this, the vesicular influx (of immature A components) is assumed to decrease with the compartment’s content in A components and to vanish for a fully matured compartment. Therefore, a fully mature compartment becomes isolated from the influx and exits the system as part of the outflux while a new compartment is created de novo. This corresponds to the cisternal maturation mechanism of Golgi transport (14). Our model thus includes both vesicular transport and cisternal maturation. The balance between these two mechanisms strongly relies on stochastic effects and is controlled by the ratio of maturation to vesicle budding rates and the steady-state organelle size.

The model is inspired by the regulatory role played by Rab GTPases on organelles dynamics (6, 7, 8, 9), but is designed to be general and molecule-independent. The membrane of vesicles and organelles is discretized into patches of different membrane compositions, to which different biochemical identities can be assigned. The molecular identity of a membrane patch is defined by the presence of components that recruit proteins involved in membrane transport, but also by lipids that influence the membrane properties by changing biophysical parameters such as the membrane-bending rigidity. The maturation of membrane identity can involve the so-called Rab cascade, by which the activation of one Rab inactivates the preceding Rab along the pathway (28), which is thought to operate both in endosomes (10) and in the Golgi (11, 29), but also the direct conversion of molecular components by enzymes, such as the glycosylation of proteins and lipids in the Golgi (30).

Model description

We assume that the vesicles responsible for the influx and the outflux are of similar size, and we divide the membranes into patches of equal area so that a transport vesicle contains Nv sites. A number nv of these sites are markers of the early (A) identity or the late (B) identity for incoming or outgoing vesicles, respectively, whereas the rest contains neutral species. The compartment state is then entirely defined by the total number of sites N and the numbers NA and NB of sites containing A and B components. We define the relative fraction of B components ϕ = NB/(NA + NB). To study the dynamics of the compartment, one must specify how the different kinetic processes depend on the compartment size and composition. We adopt the following notations for the influx of A components, the maturation flux from A to B, and the exiting flux of B components:

| (1) |

In case the number of mature sites in the compartment satisfies NB < nv, the budding vesicle is assumed to remove all NB sites, and to contain a remaining number Nv – NB neutral sites, so that JB,out = K(ϕ)NB2 (see the Supporting Material). The different parameters involved in Eq. 1 are defined below. The dynamics of the compartment is governed by the following set of stochastic transitions:

| (2) |

At the mean-field level, the temporal evolution of the different components is given by

| (3) |

This expression is valid, assuming that NB ≥ nv and that the ratio of active species (NA + NB)/N in the compartment at t = 0 matches the ratio nv/Nv in the transport vesicles. It is derived in the Supporting Material, where the case NB < nv is also discussed in more detail. This leads to the self-consistent equations for the mean-field steady state:

| (4) |

We show below that the dynamics of the system can be separated into two main classes, regardless of the details of the functional form for the different rates. The choices of functional form for the different fluxes discussed below are motivated by phenomenology rather than actual microscopic models or quantitative measurements. Other choices are possible, and will make quantitative differences. Our claim is that our general conclusions regarding the existence of these two classes are model-independent.

The flux of incoming vesicles J(N,ϕ) may depend on the size and composition of the receiving compartment. One can expect that J is independent of the compartment size if it is limited by unidimensional diffusion (e.g., along a fixed number of cytoskeleton tracks) and (linear with the compartment size, and assuming a spherical compartment) if it is limited by 3D diffusion. We require that J increases sublinearly with the compartment size, as J ∼ N would not lead to a steady state in our model. With regard to the membrane composition, homotypic fusion suggests that J decreases with increasing fraction ϕ of mature components. We assume here that no immature vesicles fuse with a fully mature compartment (J(ϕ = 1) = 0), and study two different models: a constant influx that abruptly vanishes when ϕ = 1, and a linear dependence: J ∝ (1 − ϕ), as simple choices.

Maturation (JA→B) is assumed to be a one-step process with a rate km that may involve some cooperativity and depend on the local concentration of B, hence of ϕ. As an example, in a Rab cascade, a Rab A recruits the effectors (GEF) that attract another Rab B. Subsequently, the Rab B can recruit other effectors (GAP) that favor the unbinding of Rab A (28). These complex interactions can lead to a certain amount of cooperativity. This is taken into account here by writing km(ϕ) = km(1 + αϕ), where km is the basal maturation rate and α represents the catalyzing effect of neighboring B components for the maturation of A components. A high value of α is a simple way to implement a switchlike behavior between early and late identities, which could result from the feedback loops in the Rab cascade (31, 32).

Vesicle budding (JB,out) is assumed to extract specifically the B components, and the budding rate K(ϕ) could be sensitive to the local composition of B components, e.g., if several B sites are needed to create a vesicle. After each budding event, nv sites of type B are removed in a vesicle of size Nv. If the compartment contains a smaller number of mature sites NB < nv, all these sites are removed by the budding of one vesicle and both NB and ϕ vanish.

We have assumed that maturation and budding depend on local properties (the concentration), but not on the compartment size. This assumption could break down for small compartments, where maturation could be influenced by the total number of B components in the compartment, and budding could be reduced due to mechanical effects. We disregard these complexities here to reduce the number of parameters. This model, of course, does not capture the full complexity of real cellular organelles. In addition to coated vesicles, transport between cisternae within the Golgi apparatus might also proceed via membrane tubules connecting different cisternae (33). If such connections are transient, they can be described at a coarse-grained level within our framework of composition-dependent fluxes. Another important issue in Golgi dynamics is the recycling of Golgi resident enzymes. Recycling is essential in the cisternal maturation model to ensure that the enzymes remain at a particular location within the Golgi, and is expected to proceed via retrograde (trans-to-cis) vesicular transport (34). Such complexity is not included in our model, which aims at answering well-defined questions: what are the conditions under which a steady-state mixed compartment undergoes full maturation, and how relevant is this process to the net outflux? Our analysis shows that the answer to these questions requires a stochastic analysis of compartment concentration fluctuations, which possess universal features that we identify. Including additional dynamical fields, such as the concentration of enzymes responsible for maturation, will be interesting, but is left for future work.

Output parameter

The initial state is a compartment equivalent to one immature vesicle (N = Nv, NA = nv, NB = 0). The compartment evolves toward and fluctuates around a steady state in which the vesicular outflux compensates the vesicular influx. However, this steady state has a finite lifetime, if it is reached at all. The compartment will necessarily reach full maturation (ϕ = 1) at some point due to stochastic fluctuations, and become isolated from the influx. To quantify the fraction of vesicular transport contributing to the total outflux, we propose to compute the output parameter η defined as follows:

| (5) |

where 〈Nves〉 is the average number of matured (type B) vesicles emitted by the compartment before full maturation (ϕ = 1), and 〈Nmat〉 is the average size (measured in vesicle-equivalents) N/Nv of the fully matured compartment. The outflux is dominated by vesicular transport if η 1 and by full compartment maturation if η ≪ 1.

Results

In this section, we first present analytical results for a simplified model where fusion, maturation, and budding occur at constant rates and nv = 1. We then explore the case of composition-dependent rates numerically and explain the main differences that arise based on the mean-field dynamics of the system. The effect of size-dependent fusion, which we found to be minor, is discussed in the Supporting Material.

Analytical solution for constant rates

We start by analyzing the simplest version of the model with nv = 1 and where the influx J, the maturation rate km, and the fusion rate K are all constant, independent of the compartment size and composition. In this case, one may obtain an analytical solution for the isolation time of a compartment, and an approximate analytic expression for the output parameter η. The mean first passage time to isolation, namely the time needed to reach NA = 0 starting at NA = 1, can be calculated exactly, as the dynamics of A components in the compartment is independent from the dynamics of the B components. The transition rates governing the evolution of NA(t) are

| (6) |

The average time τn needed to reach NA = 0 starting from a state NA = n following this simple stochastic process satisfies the classical recursion law for mean first passage times (35), which is derived in the Supporting Material. For the rates defined in Eq. 6, the recursion relation reads:

| (7) |

An expression for the average time to full maturation starting from a newly created compartment, τ1, can be obtained by solving Eq. 7 recursively to obtain the expression:

| (8) |

For n ≫ J/km, the mean field analysis, Eq. 3, suggests that the system first evolves toward the (quasi) stationary state given by Eq. 4, in a typical time of the order of 1/km independent of n, and remains there for a (potentially long) time before full maturation. Therefore, we expect that , which leads to an explicit formula for τ1:

| (9) |

where N and ϕ are the steady-state average size and composition of the compartment (Eq. 4).

To estimate the value of the output parameter η (Eq. 5), we must compute the average number of vesicles emitted before compartment isolation 〈Nves〉, and the average size of the fully matured compartment 〈Nmat〉. Calculating these quantities analytically is difficult, because it requires solving the 2D isolation problem for NA and NB. An estimate of the size of the matured compartment is 〈Nmat〉 Nϕ. This amounts to saying that isolation occurs due to a temporary lack of incoming vesicles, whereas the number of B components retains its steady-state value due to a balance between maturation and vesicle secretion. An estimate of the amount of emitted vesicles before maturation can be obtained by supposing that the system spends most of its time undergoing small fluctuations around the steady state, so that Nves ≈ KNϕτ1 = eN(1−ϕ) −1. The fact that newly formed compartments are initially small and may reach full maturation without ever reaching the steady state modifies this estimate. This can be crudely taken into account by considering that the initial compartment made of one vesicle can mature directly and become isolated in only one step. This one-step maturation event corresponds to Nves = 0 and Nmat = 1 and happens with the probability:

| (10) |

Taking this into account, we obtain the following estimates:

| (11) |

from which we get the approximate results:

| (12) |

Numerical simulation under constant maturation and budding rates

We performed numerical simulations of the stochastic dynamics of Eq. 2, following the Gillespie scheme described in the Supporting Material. We first restrict ourselves to the case where the maturation and fusion rates are constant and where the content of transport vesicles corresponds to a single membrane patch: (Nv = nv = 1). We focus our analysis on two experimentally observable quantities: the dynamical features of individual time traces of size and concentration fluctuations of compartments, and the size distribution of fully mature compartments. Averaging over many simulations, we construct a phase diagram for the output parameter as a function of the different exchange rates that illustrates the regions where maturation and vesicular exchange dominate the compartment dynamics.

Constant influx

We first report the results of simulations when all the exchange rates (Influx J, maturation rate km, and budding rate K) are constant, as in the analytical calculation of the previous section. A typical evolution of the number of A components and the total number of components in the compartment is shown in Fig. 2 a. Depending on the ratio of maturation to budding rate, the system either displays strong fluctuations around the steady state (Eq. 4), which eventually lead to the complete maturation of all A components, or exhibits full maturation before reaching the steady state.

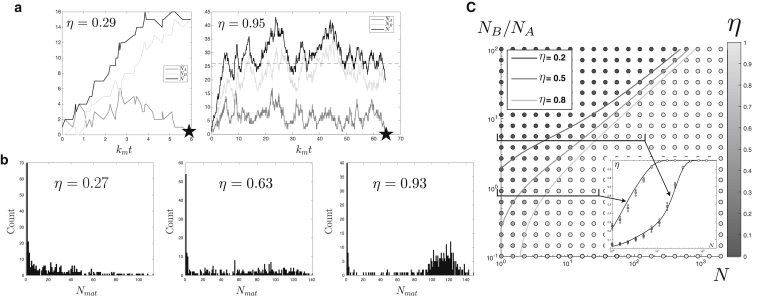

Figure 2.

Simulation results for constant rates. (a) Typical time traces are given, showing the fluctuations of the compartment’s content in A and B sites (NA and NB) and total size N/Nv = NA + NB as a function of the dimensionless time kmt, in the maturation (η = 0.29, J/km = 4.16, and K/km = 0.1905) and vesicular (η = 0.95, J/km = 6, and K/km = 0.3) regimes. The steady-state value of N is shown as a dashed line and full maturation is indicated by a solid star. (b) Size distribution of fully matured compartments (Nmat) was obtained from 320 independent simulations (for three different values of η). The steady-state parameters are N = 121, NB/NA = 33.6, 23.4, and 16.2 from left to right. (c) Given here is a phase diagram for the value of the output parameter η as a function of the pseudo steady-state compartment size N and ratio NB/NA, showing the transition between the vesicular exchange (η 1) and compartment maturation (η 0) regimes. The three shaded lines represent constant values of η as given by the approximate analytical computation of Eq. 12. (Inset) Shown here are cuts through the phase diagram varying the compartment size for two fixed pseudo steady-state compositions. The solid lines are obtained using Eq. 12 and the dots are the simulation results and the associated error bars.

After many independent realizations of the maturation process, one obtains a distribution of values for the size of the fully mature compartment Nmat and the number of vesicles exported before the full maturation Nves, from which the output parameter η (Eq. 5) can be calculated. Fig. 2 b shows that the distribution of Nmat is rather broad in the maturation-dominated regime (small values of η) and shows a peak at the steady-state compartment size in the regime dominated by vesicular exchange (η 1). The values of Nmat and Nves for different parameters are represented as scatter plots in the Supporting Material. They are well fitted by assuming that the compartment follows the mean field dynamics given by Eq. 3 and assuming that full maturation occurs after a time tmat:

| (13) |

This shows that, for the parameters of Fig. 2, the main source of fluctuation comes from the distribution of the isolation time tmat.

The phase diagram for the output parameter is shown in Fig. 2 c as a function of the steady-state compartment size and distribution. The same diagram is shown as a function of the model parameters J/K and km/K in the Supporting Material. The two extreme mechanisms of vesicular exchange (η ≈ 1) and compartment maturation (η ≈ 0) are observed for extreme values of the parameters, namely large steady-state compartment size N for the former and high value of the steady-state fraction ϕ for the latter. However, the phase diagram shows a richer picture, with a gradual transition between the two mechanisms upon variation of the ratio of maturation to budding rates for intermediate compartment size. The analytical calculation of the output parameter (Eq. 12) faithfully reproduces the numerical results, except for very small compartments.

The size distribution of mature compartments (Fig. 2 b) shows a large peak at very small size (Nmat 1). This corresponds to cases where a young compartment undergoes direct maturation before any, or after a few, fusion and budding events. Such a fully mature compartment is structurally indistinguishable from a budded vesicle, and it may seem arbitrary to include the former in the maturation flux and the latter in the vesicular flux, as is done in the definition of the output parameter (Eq. 5). This is nevertheless reasonable within our model, where the difference between the two fluxes is a matter of kinetic processes rather than a difference of structure. For completeness, we show in the Supporting Material an equivalent of Fig. 2 c for two alternative definitions of the output parameter, either removing all direct maturation events, or removing all events where the fully mature compartment is of unit size (e.g., following the same number of fusion and budding events). The difference is only quantitative, and only appreciable for very small steady-state size.

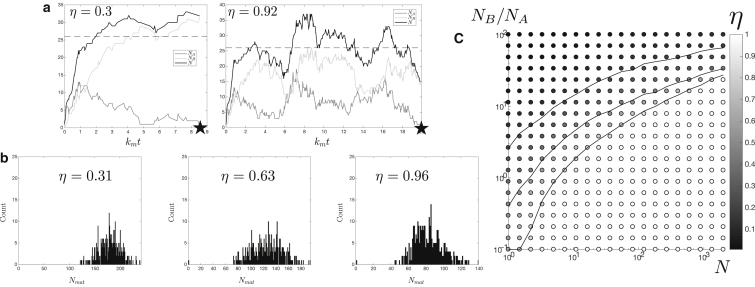

Composition-dependent influx

The previous model with a composition-independent influx possesses the rather arbitrary feature that the influx abruptly drops to zero when the compartment reaches full maturation. Although it is possible that homotypic fusion could permit a steady influx of immature vesicles with only one, or a few, immature site in the compartment, one may also expect a more gradual dependence of the influx with the compartment concentration. We present in Fig. 3 the same results as in Fig. 2, but with an influx that linearly decreases with the composition of the compartment: J = J0(1 − ϕ) (henceforth called the “homotypic fusion model”). The general features of the phase diagram are conserved, namely the dominance of maturation for small compartments and large steady-state fraction of B components. A composition-dependent influx, however, brings three important qualitative differences: 1) the vesicular exchange-to-maturation transition shows a much weaker dependence upon the steady-state compartment size (for large sizes); 2) the size distribution of a fully mature compartment is always peaked around a large size and direct maturation of incoming vesicles (Nmat = 1) is very rare; and 3) the time trace of the compartment composition in A and B species seems anticorrelated, and displays oscillations for large η. We show below that these features can be understood by analyzing the mean-field dynamics of the system.

Figure 3.

Simulation results with homotypic fusion. Identical to Fig. 2, but for a concentration-dependent influx J = J0(1 − ϕ). (a) Typical time traces of the compartment composition are given for two values of the output parameter (η = 0.3 corresponds to J/km = 26 and K/km = 0.06, and η = 0.92 corresponds to J/km = 26 and K/km = 0.5). (b) Shown here is the size distribution of fully matured compartments (the steady-state parameters are N = 121 and NB/NA = 23.4, 11.3, 5.46 from left to right). (c) Phase diagram is shown for the value of the output parameter η as a function of the pseudo steady-state compartment size N and ratio NB/NA of the two components. The three gray lines represent constant values of η = 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, as in Fig. 2.

Effect of the other parameters

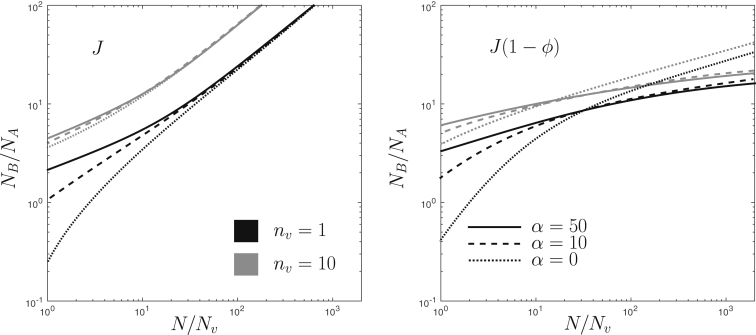

We now relax the assumption that the entire content of incoming vesicles matures as one entity and assume that the incoming and outgoing vesicles contain Nv independent membrane sites, of which nv are active sites as in Fig. 1 b. We also include the possibility for cooperative maturation (km(ϕ) = km(1 + αϕ) in Eq. 1). The impact of these parameters on the transition between compartment maturation and vesicular exchange is shown in Fig. 4, which displays the boundary corresponding to η = 0.5 for constant and composition-dependent influx, varying the maturation cooperativity parameter α and using two values of the number of active molecules in the incoming vesicles: nv = 1 and nv = 10. The latter value is the typical number of Rab molecules in a transport vesicle (36). The global trends are as follows: cooperativity in the maturation process disfavors maturation for very small compartments but favors it for large compartments (N 10 Nv). The number of maturing components per vesicle nv has a strong impact on the position of the boundary—is favoring full compartment maturation—for constant influx, but only has a weaker effect with composition-dependent influx. Combining homotypic fusion with high maturation cooperativity renders the transition almost independent of the compartment size. The full phase diagrams, displayed in the Supporting Material, show that the width of the transition does not depend on nv or α, but only on whether the influx is composition-dependent.

Figure 4.

Level curves (η = 0.5) extracted from phase diagrams similar to the one in Fig. 3 for composition-dependent rates of the different kinetic processes in Eq. 1. The vesicular influx J(N,ϕ) is either constant (left panel) or controlled by linear homotypic fusion (J = J0(1 – ϕ), right panel). The effect of cooperativity in the maturation process is seen by varying the coefficient α (with a maturation rate km(ϕ) = km(1 + αϕ)). The number of components per vesicle is nv = 1 (solid curves) and nv = 10 (shaded curves). The curves corresponding to the phase diagram of Figs. 2 and 3 are shown as a dotted line in the left and right panels, respectively.

As a final refinement of the model, we also consider the possibility that the maturation of A into B components might involve several steps. This is, for instance, the case of the Rab cascade, which includes the recruitment of GEF and GAP molecules. At our level of description, the principal consequence of having several reaction steps is that the maturation waiting time might not be exponentially distributed. In the Supporting Material, we study the extreme case where the maturation of a single A component involves a very large number of independent steps and becomes an almost deterministic process with a fixed waiting time. Remarkably, we show that the average maturation time τ1 is still given by Eq. 9. This suggests that our results do not depend much on the distribution of maturation times.

Role of homotypic fusion

The peculiar dynamics of compartments experiencing composition-dependent influx, namely the anticorrelated nature of composition variations of A and B components before maturation, the peaked size distribution of a fully matured compartment, and the weak dependence of the full maturation probability on the compartment steady-state size, can all be understood from the mean-field dynamics given by Eq. 3. The steady state (Eq. 4) is always stable in our model, but the relaxation toward the fixed point is either overdamped if J is constant, or underdamped (oscillatory) with homotypic fusion (J ∼ (1 − ϕ)), beyond a critical ratio of . This is analyzed in the Supporting Material. In the absence of cooperativity in the maturation process (α = 0), the critical ratio obeys

| (14) |

This threshold decreases with increasing α (see the Supporting Material).

Far above threshold (km/K ≫ 1), the compartment first grows through a burst of vesicle injection (NA ≫ 1, NB ≈ 0), followed by a slower maturation process (NA ≈ 0, NB ≫ 1). During the latter, only a few stochastic maturation steps are needed to reach full maturation. The likelihood of this to happen becomes weakly dependent on the compartment size, and on the level of coarse-graining nv. The size distribution of fully mature compartments reflects these dynamics. If J is constant, it is peaked at the mean-field steady-state size (Eq. 4) when vesicular exchange dominates the outflux (η 1), but is rather broad in the maturation dominated regime; see Fig. 2 b. With composition-dependent influx, full maturation occurs predominantly during phases of the spiraling trajectories where NA is small, leading to a large matured compartment with a well-defined range of sizes Fig. 3 b. Finally, the absence of direct maturation of incoming vesicles (Nmat = 1) with homotypic fusion can be understood as follows: a given steady state (N, ϕ) corresponds to a smaller value of the ratio of influx over maturation rate for a constant influx (J0/km = N(1 – ϕ)) than for a composition-dependent influx (J0/km = N). The likelihood of direct maturation of incoming vesicles (the probability p1 in Eq. 10) before a fusion event is thus strongly reduced by homotypic fusion.

The linear stability analysis of the mean-field equations can easily be extended to any functional form one wishes to explore, but what really matters is whether the system is in the overdamped or underdamped regime. As we show above, this is mostly controlled by homotypic fusion. Using a linear stability analysis method, one can easily convince oneself that if the budding rate increases with the concentration of B component, as could be expected if budding is a cooperative process, the range of parameter for which the dynamics is overdamped is increased (the fixed point is stabilized) and full maturation is disfavored. If the budding rate is assumed to follow a Michaelis-Menten kinetics with saturation at high concentration, the effect is reversed, and full maturation is favored.

Discussion

Are membrane-bound organelles along the cellular secretory and endocytic pathways steady-state structures receiving, processing, and exporting transiting cargoes, or are they transient structures that grow by fusion of smaller structures until they reach full maturation? To address this question from a theoretical viewpoint, we have developed a minimal stochastic model combining compartment maturation and vesicular exchange. The model is based on two fundamental assumptions: that there exists a steady state where the outflux balances the influx, and that there exists a particular composition of the system for which it becomes committed to full maturation. The former assumption is a widespread concept for cellular organelles in general (37), and the endomembrane system in particular (38). The latter is supported by observations of early endosomes (10) and S. cerevisiae Golgi cisternae (12, 13). We show that the organelle’s dynamics is essentially controlled by two parameters: the ratio of vesicle injection to budding rate, which controls the steady-state size of the organelle; and the ratio of biochemical maturation to budding rate, which controls the organelle’s steady-state composition.

Our main results are summarized Figs. 2 and 3. For low maturation rates (compared to the budding rate), the flux of mature material leaving the system is predominantly composed of budded vesicles of mature components. The organelle remains at steady state for a long time while exporting vesicles of mature component. When full maturation occurs, the mature compartment has a size distribution peaked around the steady-state size. For high maturation rates on the other hand, full maturation typically occurs before the steady state is reached and the outflux is mostly composed of fully mature compartment. Importantly, full maturation can follow one of two types of dynamics: the trajectory in the phase space (size and composition) is either a quasi-random walk eventually hitting the full maturation threshold, or is a spiraling trajectory around the fixed point that reaches full maturation in a quasi-deterministic fashion. The difference is important, as the fully mature organelles produced by the former mechanism are unlikely to be very large and have a broad size distribution, whereas those produced by the latter can be large and have a peaked size distribution. A necessary condition for the occurrence of deterministic maturation is that the influx decreases as the organelle becomes more mature, which is an expected consequence of homotypic fusion. Positive feedback in the maturation process renders full compartment maturation more deterministic.

Figs. 2 and 3 suggest that the dominant export mechanism of an organelle could be inferred by analyzing individual time series of the organelle’s size and composition. Maturation of S. cerevisiae Golgi cisternae from a cis to a trans identity appears fairly deterministic, with a gradual evolution from one identity to the other (12, 13). This suggests that this organelle is in the maturation-dominated regime helped by homotypic fusion, a conclusion reinforced by the observation that different time traces of compartment composition display reproductible dynamics (13). Maturation of early endosomes into late endosomes appear much more stochastic, with large composition fluctuations (10). In this case, our results suggest that vesicular export of the late membrane identity (which has not been investigated in (10)) might dominate the dynamics. Note that the individual fluorescence tracks shown in (10) seem to display large amplitude oscillations before full maturation, similar to the theoretical tracks shown in Fig. 3. In our model, these oscillations are a consequence of the spiraling (overdamped) trajectories in the phase space, a signature of homotypic fusion. This suggests that, although in the vesicular exchange regime, these endosomes are fairly close to the maturation transition, and that endosomal dynamics could be converted to a maturation-dominated regime by a small change of parameters, such as an increase in the ratio of maturation rate to budding rate. These considerations are clearly very preliminary, and a more systematic analysis is needed to reach a more definite conclusion, but these examples illustrate the intimate link between the temporal fluctuations of individual components and the time-average export dynamics of organelles.

Vesicular exchange and maturation in the Golgi apparatus

Are Golgi cisternae stable structures that receive and export material while retaining their identity, or are they transient structures that progressively mature from the cis to the trans identities? Although evidence for the latter dynamics exists in endosomes and the Golgi cisternae of the yeast S. cerevisiae, this issue is not resolved for the stacked Golgi of most higher eukaryotes including mammalian cells, for which a long-lasting controversy exist between the cisternal maturation and vesicular exchange transport models. The reality might lie between these two extreme scenarios, and our model can in principle give a quantitative answer as to the fraction contributed by each mechanism to the total outflux, provided that the rates of vesicular influx, maturation, and budding are known. The challenge in comparing our theory to experiments lies in obtaining accurate values for these rates. In the following, we concentrate on the dynamics of the Golgi apparatus, and we adopt the estimate 10−3 ≤ K ≤ 10−2 s−1 for the budding rate for COPI vesicles (39). Values for the influx depend on whether one considers the Golgi ribbon of vertebrate cells that receives influx from the entire ER (40), for which we estimate J ∼ 10 – 102 s−1, or individual Golgi mini-stacks formed at ER exit sites, for which we estimate J ∼ 10−2 – 10−1 s−1 (41, 42). We also take the latter value for the influx toward individual cisternae of the dispersed Golgi of yeast S. cerevisiae. Maturation of Golgi cisternae of the yeast S. cerevisiae has been monitored by live imaging, yielding an isolation time of order τ ≈ 102 s (12, 13, 43). For a stacked Golgi, and assuming the isolation time is of the order of the typical transit time of cargoes across the stack (a lower bound corresponding to the cisternal maturation model), it is of order τ ≈ 103 s (44, 45). With these parameters and assuming a constant influx, the maturation rate can be obtained from Eq. 9 and the steady-state size and composition of cisternae from Eq. 4. We find km ∼ 10−2 – 10−1 s−1 for S. cerevisiae, and km ∼ 10−3 – 10−2 s−1 for Golgi ministacks. The output parameter (Eq. 5) is of order η = 0.1–0.5 for S. cerevisiae and η = 0.5–0.9 for ministacks, placing the former in the maturation-dominated regime (in agreement with previous studies (13, 46)) and the latter in the vesicular exchange-dominated regime (as studies based on cargo transport dynamics also concluded (45, 47)). The predicted steady-state size N ∼ 10–100 for both is reasonable. These conclusions remain qualitatively valid with the homotypic fusion model and a composition-dependent influx. It is unclear whether the rather simple model developed here is adequate to describe the Golgi ribbon, itself a compact assembly of somewhat interconnected Golgi mini-stacks (40). With the corresponding parameters, we find a maturation rate km ∼ 1 – 10 s−1, corresponding to η ∼ 0.5–0.9, also in the vesicular exchange-dominated regime, and a steady-state size N = 104 − 105.

It is interesting to notice that the Golgi in the two different cell types are predicted to be on opposite sides of the boundary between vesicular exchange and cisternal maturation, and also have very distinct morphologies (dispersed versus stacked), suggesting a possible correlation between dynamics and morphology. When S. cerevisiae is starved in a glucose-free environment, the isolation time of Golgi cisternae increases to τ = 3 × 102 s (48). Within our model, an increase of τ can result from an increase of J or a decrease of km (Eq. 9). The latter seems much more likely than the former in a starved situation. The slowing down of Golgi kinetics leads to a shift toward the vesicular exchange-dominated regime (η ∼ 0.2–0.7). Remarkably, the Golgi structure is also modified, and resembles the stacked Golgi structure in Pichia pastoris (48). This observation strengthens the proposal that correlations exist between Golgi structure and transport kinetics. The Golgi of P. pastoris could be intermediate, both in terms of transport dynamics and structure, between the Golgi of S. cerevisiae and the stacked Golgi of most eukaryotes, as it is at the same time stacked and shows continuous cisternae turnover akin to cisternal maturation at its trans face (49). Unfortunately, we could not evaluate the output parameter for P. pastoris, as there is to our knowledge no available quantitative data of Golgi transport kinetics in this organism.

Quantitatively testable predictions of the model

Statistics of individual time traces

Our model makes a number of experimentally testable predictions, regarding the relationship between the dynamics of individual compartments, and in particular the concentration fluctuations over time, the size distribution of mature compartment, and the dominant export mechanism. The time average dynamics of the system can in principle be obtained from a statistically significant set of individual time series of compartment size and composition. The crude rule of thumb is that if an organelle spends a significant fraction of time at a quasi-steady state, possibly undergoing large fluctuations around it, its dynamics is likely to be in the vesicular exchange regime. The distribution of maturation time, experimentally more accessible than the size distribution of mature compartments as those might undergo further homotypic fusion, is less discriminatory as it is model-dependent. Although a broad distribution is a signature of a maturation-dominated regime with a constant (or weakly composition-dependent) influx, a peaked distribution could correspond to a regime dominated by vesicular exchange, but also to a maturation-dominated regime with a composition-dependent influx (related to homotypic fusion), which renders full maturation almost deterministic. Thus, the combined analysis of individual time trace and the distribution of isolation time can inform us both on the dominant export mechanism, and on the specificity of the fusion, maturation, and budding processes.

Rate of cargo transport

Our model produces an interesting prediction with regard to cargo transport. At steady state, a cargo exported in vesicles should leave organelles such as the Golgi at a rate J, whereas a cargo unable to enter a transport vesicle and relying solely on cisternal maturation should be exported at a (potentially much) slower rate according to the constant flux model, Eq. 9. This could apply to large protein complexes such as procollagen, whose progression through the Golgi stack, which is about twice as slow as that of smaller membrane proteins such as VSVG (47), has been taken as evidence for cisternal maturation (44, 50). Regulation of the export mechanism could be very important for the transport of such large cargoes that do not fit inside export vesicles. Our results suggest a possible mechanism for this regulation. The presence of such large cargo as procollagen in Golgi cisternae could reduce the rate of vesicle secretion K, e.g., by mechanical means through an increase of membrane tension imposed by the distension of the cisternal membrane. This would favor full cisternal maturation and permits the progression of the large cargo through the Golgi stack. Interestingly, VSVG has been observed to move synchronously with procollagen when both are present in the Golgi (44), lending support to this regulatory mechanism. Note, however, that quantitative analysis of intra-Golgi transport suggests that procollagen transport does not solely rely on cisternal maturation (47).

Conclusions

The highly dynamical nature of intracellular organization requires the exchange processes between organelles to be tightly regulated to yield robust directional flow of material through the cell. Whereas the cell may to some extent be viewed as the steady state of a complex dynamical system, the specific budding, fusion, and maturation events that shape its organization are inherently stochastic processes. Owing to the relatively small size of many cellular organelles, stochastic fluctuations must be accounted for in models of their dynamics. We have developed a stochastic dynamical model to study the interplay between maturation and exchange in intracellular trafficking. Our model can reproduce both the strong fluctuations of size and composition seen in early endosomes (10) (Fig. 2) and the more deterministic maturation of individual Golgi cisternae in S. cerevisiae. It includes as asymptotic limits the two extreme exchange mechanisms at the heart of the Golgi transport controversy (14): vesicular exchange and compartment maturation. We identify full compartment maturation as a first-passage process, whose likelihood decreases with increasing organelle size. We also found that the interplay of homotypic fusion and cooperative maturation increases the probability of full maturation and reduces its size dependence. These mechanisms therefore act as regulators to provide robustness to full compartment maturation against stochastic fluctuations.

Author Contributions

Q.V. and P.S. designed the research. Q.V. performed the research. Q.V. and P.S. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work has received support under the program “Investissements d’Avenir” launched by the French Government and implemented by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under grant No. ANR-10-LABX-0038.

Editor: Anatoly Kolomeisky.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods and four figures are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)35098-1.

Supporting Citations

Reference (51) appears in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Bonifacino J.S., Glick B.S. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 2004;116:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munro S. Organelle identity and the organization of membrane traffic. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:469–472. doi: 10.1038/ncb0604-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro S. The Golgi apparatus: defining the identity of Golgi membranes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Goot F.G., Gruenberg J. Intra-endosomal membrane traffic. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly R.B. Pathways of protein secretion in eukaryotes. Science. 1985;230:25–32. doi: 10.1126/science.2994224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schimmöller F., Simon I., Pfeffer S.R. Rab GTPases, directors of vesicle docking. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:22161–22164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerial M., McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenmark H., Olkkonen V. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-5-reviews3007. reviews3007.1–reviews3007.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rink J., Ghigo E., Zerial M. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell. 2005;122:735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfeffer S.R. How the Golgi works: a cisternal progenitor model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:19614–19618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011016107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuura-Tokita K., Takeuchi M., Nakano A. Live imaging of yeast Golgi cisternal maturation. Nature. 2006;441:1007–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature04737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Losev E., Reinke C.A., Glick B.S. Golgi maturation visualized in living yeast. Nature. 2006;441:1002–1006. doi: 10.1038/nature04717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emr S., Glick B.S., Wieland F.T. Journeys through the Golgi—taking stock in a new era. J. Cell Biol. 2009;187:449–453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu X., Steet R.A., Freeze H.H. Mutation of the COG complex subunit gene COG7 causes a lethal congenital disorder. Nat. Med. 2004;10:518–523. doi: 10.1038/nm1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellokumpu S., Sormunen R., Kellokumpu I. Abnormal glycosylation and altered Golgi structure in colorectal cancer: dependence on intra-Golgi pH. FEBS Lett. 2002;516:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonatas N.K., Stieber A., Gonatas J.O. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus in neurodegenerative diseases and cell death. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006;246:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Z., Zeng L., Li T. The study of Golgi apparatus in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Res. 2007;32:1265–1277. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bexiga M.G., Simpson J.C. Human diseases associated with form and function of the Golgi complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:18670–18681. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinrich R., Rapoport T.A. Generation of nonidentical compartments in vesicular transport systems. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:271–280. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binder B., Goede A., Holzhütter H.G. A conceptual mathematical model of the dynamic self-organisation of distinct cellular organelles. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dmitrieff S., Sens P. Cooperative protein transport in cellular organelles. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2011;83:041923. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.041923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foret L., Dawson J.E., Jülicher F. A general theoretical framework to infer endosomal network dynamics from quantitative image analysis. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:1381–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gong H., Guo Y., Schwartz R. Discrete, continuous, and stochastic models of protein sorting in the Golgi apparatus. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2010;81:011914. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.011914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bressloff P., Newby J. Stochastic models of intracellular transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2013;85:135–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novozhilov A.S., Karev G.P., Koonin E.V. Biological applications of the theory of birth-and-death processes. Brief. Bioinform. 2006;7:70–85. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbk006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Assaf M., Meerson B. Extinction of metastable stochastic populations. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2010;81:021116. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.81.021116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grosshans B.L., Ortiz D., Novick P. Rabs and their effectors: achieving specificity in membrane traffic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:11821–11827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601617103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera-Molina F.E., Novick P.J. A Rab GAP cascade defines the boundary between two Rab GTPases on the secretory pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14408–14413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906536106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley P. Golgi glycosylation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conte-Zerial P.D., Brusch L., Deutsch A. Membrane identity and GTPase cascades regulated by toggle and cut-out switches. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:206. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Binder B., Holzhütter H.-G. A hypothetical model of cargo-selective Rab recruitment during organelle maturation. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2012;63:59–71. doi: 10.1007/s12013-012-9341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh B.J., Volkmann N., Howell K.E. Direct continuities between cisternae at different levels of the Golgi complex in glucose-stimulated mouse islet β-cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5565–5570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401242101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malhotra V., Mayor S. Cell biology: the Golgi grows up. Nature. 2006;441:939–940. doi: 10.1038/441939a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kampen N.G.V. Elsevier; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2007. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takamori S., Holt M., Jahn R. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan Y.-H.M., Marshall W.F. How cells know the size of their organelles. Science. 2012;337:1186–1189. doi: 10.1126/science.1223539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y., Wei J.-H., Seemann J. Golgi cisternal unstacking stimulates COPI vesicle budding and protein transport. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei J.-H., Seemann J. Unraveling the Golgi ribbon. Traffic. 2010;11:1391–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thor F., Gautschi M., Helenius A. Bulk flow revisited: transport of a soluble protein in the secretory pathway. Traffic. 2009;10:1819–1830. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warren G. Transport through the Golgi in Trypanosoma brucei. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2013;140:235–238. doi: 10.1007/s00418-013-1112-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhave M., Papanikou E., Bhattacharyya D. Golgi enlargement in Arf-depleted yeast cells is due to altered dynamics of cisternal maturation. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:250–257. doi: 10.1242/jcs.140996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mironov A.A., Beznoussenko G.V., Luini A. Small cargo proteins and large aggregates can traverse the Golgi by a common mechanism without leaving the lumen of cisternae. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:1225–1238. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patterson G.H., Hirschberg K., Lippincott-Schwartz J. Transport through the Golgi apparatus by rapid partitioning within a two-phase membrane system. Cell. 2008;133:1055–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papanikou E., Glick B.S. The yeast Golgi apparatus: insights and mysteries. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3746–3751. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dmitrieff S., Rao M., Sens P. Quantitative analysis of intra-Golgi transport shows intercisternal exchange for all cargo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15692–15697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303358110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levi S.K., Bhattacharyya D., Glick B.S. The yeast GRASP Grh1 colocalizes with COPII and is dispensable for organizing the secretory pathway. Traffic. 2010;11:1168–1179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mogelsvang S., Gomez-Ospina N., Staehelin L.A. Tomographic evidence for continuous turnover of Golgi cisternae in Pichia pastoris. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:2277–2291. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bonfanti L., Mironov A.A., Jr., Luini A. Procollagen traverses the Golgi stack without leaving the lumen of cisternae: evidence for cisternal maturation. Cell. 1998;95:993–1003. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillespie D.T. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1977;81:2340–2361. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.