Abstract

Comparative analysis of the expanding genomic resources for scleractinian corals may provide insights into the evolution of these organisms, with implications for their continued persistence under global climate change. Here, we sequenced and annotated the genome of Pocillopora damicornis, one of the most abundant and widespread corals in the world. We compared this genome, based on protein-coding gene orthology, with other publicly available coral genomes (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Scleractinia), as well as genomes from other anthozoan groups (Actiniaria, Corallimorpharia), and two basal metazoan outgroup phlya (Porifera, Ctenophora). We found that 46.6% of P. damicornis genes had orthologs in all other scleractinians, defining a coral ‘core’ genome enriched in basic housekeeping functions. Of these core genes, 3.7% were unique to scleractinians and were enriched in immune functionality, suggesting an important role of the immune system in coral evolution. Genes occurring only in P. damicornis were enriched in cellular signaling and stress response pathways, and we found similar immune-related gene family expansions in each coral species, indicating that immune system diversification may be a prominent feature of scleractinian coral evolution at multiple taxonomic levels. Diversification of the immune gene repertoire may underlie scleractinian adaptations to symbiosis, pathogen interactions, and environmental stress.

Introduction

Scleractinian corals serve the critical ecological role of building reefs that provide billions of dollars annually in goods and services1 and sustain high levels of biodiversity2. However, corals are declining rapidly as ocean acidification impairs coral calcification and interferes with metabolism3, ocean warming disrupts their symbiosis with photosynthetic dinoflagellates (family Symbiodiniaceae)4, and outbreaks of coral disease lead to mortality5. As basal metazoans, corals provide a model for studying the evolution of biomineralization6, symbiosis7, and immunity8,9 - key traits which mediate ecological responses to these stressors. Understanding the genomic architecture of these traits is therefore critical to understanding corals’ success over evolutionary time10 and under future environmental scenarios. In particular, there is great interest in whether corals possess the genes and genetic variation required to acclimatize and/or adapt to rapid climate change11–13. Addressing these questions relies on the growing genomic resources available for corals, and establishes a fundamental role for comparative genomic analysis in these organisms.

Genomic resources for corals have expanded rapidly in recent years, with genomic or transcriptomic information now available for at least 20 coral species10. Comparative genomics in corals has identified genes important in biomineralization, symbiosis, and environmental stress response10, and highlighted the evolution of specific immune gene repertoires in corals14,15 However, complete genome sequences have only been analyzed and compared for two coral species, Acropora digitifera16 and Stylophora pistillata17, revealing extensive differences in genomic architecture and content. Therefore, additional complete coral genomes and more comprehensive comparative analysis may be transformative in our understanding of the genomic content and evolutionary history of reef-building corals, as well as the importance of specific gene repertoires and diversification within coral lineages.

Here, we present the genome of Pocillopora damicornis, one of the most abundant and widespread reef-building corals in the world18. This ecologically important coral is a model species and is commonly used in experimental biology and physiology. It is also the subject of a large body of research on speciation19–21, population genetics22–25, symbiosis ecology26–28, and reproduction29–31. Consequently, the P. damicornis genome sequence advances a number of fields in biology, ecology, and evolution, and provides a direct foundation for future studies in transcriptomics, population genomics, and functional genomics of corals.

Using the P. damicornis genome and other publicly available genomes of cnidarians and basal metazoans, we performed a comparative genomic analysis within the Scleractinia. Using this analysis, we address the following critical questions: (1) which genes are specific to or diversified within the scleractinian lineage, (2) which genes are specific to or diversified within individual scleractinian coral species, and (3) which features distinguish the P. damicornis genome from those of other corals. We address these questions based on orthology of protein-coding genes, which generalizes the approaches taken by Bhattacharya et al.10 and Voolstra et al.17 to a larger set of complete genomes to describe both shared and unique adaptations in the Scleractinia. In comparing these genomes, we reveal prominent diversification and expansion of immune-related genes, demonstrating that immune pathways are the subject of diverse evolutionary adaptations in corals.

Results and Discussion

P. damicornis genome assembly and annotation

The estimated genome size of P. damicornis is 349 Mb, smaller than other scleractinian genomes analyzed to date (Table 1). The size of the final assembly produced here was 234 Mb, and likely lacks high-identity repetitive content (estimated ~25% of the genome based on 31-mers) that could not be assembled. Total non-repetitive 31mer content was estimated at 262 Mb and the sum of contigs was 226 Mb, indicating that up to 14% of non-repetitive content may also be missing from the assembly, likely due to high heterozygosity (Dovetail Genomics, personal communication). However, the assembly comprises 96.3% contiguous sequence, and has the highest contig N50 (28.5 kb) of any cnidarian genome assembly (Table 1). We identified 26,077 gene models, which is consistent with the gene content of other scleractinian and cnidarian genomes (Table 1). Among these genes, 59.7% had identifiable homologs (E-value 10−5) in the SwissProt database, 73% contained identifiable homologs in at least one of the other 10 genomes, and 83.7% contained protein domains annotated by InterProScan. Genome completeness was evaluated using BUSCO, which found that 88.4% of metazoan single-copy orthologs were present and complete (0.5% were duplicated), 2.9% were present but fragmented, and 8.7% were missing. Together, these statistics indicate the P. damicornis genome assembly is of high quality and mostly complete (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assembly and annotation statistics for the P. damicornis genome (Pdam) and others used for comparative analysis. (Spis = Stylophora pistillata17; Adig = Acropora digitifera16; Ofav = Orbicella faveolata100; Disc = Discosoma spp.101; Afen = Amplexidiscus fenestrafer101; Aipt = Aiptasia85; Nema = Nematostella vectensis102; Hydr = Hydra vulgaris103; Mlei = Mnemiopsis leidyi104; Aque = Amphimedon queenslandica105). *Re-annotated using present pipeline (github.com/jrcunning/ofav-genome).

| Pdam | Spis | Adig | Ofav* | Disc | Afen | Aipt | Nema | Hydr | Mlei | Aque | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (Mb) | 349† | 434 | 420 | 428 | 350 | 260 | 329 | 1300 | 190 | ||

| Assembly size (Mb) | 234 | 400 | 419 | 486 | 445 | 370 | 258 | 356 | 852 | 156 | 167 |

| Total contig size (Mb) | 226 | 358 | 365 | 356 | 364 | 306 | 213 | 297 | 785 | 150 | 145 |

| Contig/Assembly (%) | 96.3 | 89.5 | 87 | 73.3 | 81.9 | 82.6 | 82.5 | 83.4 | 92.2 | 96.5 | 86.8 |

| Contig N50 (kb) | 25.9 | 14.9 | 10.9 | 7.4 | 18.7 | 20.1 | 14.9 | 19.8 | 9.7 | 11.9 | 11.2 |

| Scaffold N50 (kb) | 326 | 457 | 191 | 1162 | 770 | 510 | 440 | 472 | 92.5 | 187 | 120 |

| No. gene models | 26077 | 25769‡ | 23668 | 37660 | 23199 | 21372 | 29269 | 27273 | 31452 | 16554 | 29867 |

| No. complete gene models | 21389 | 25563‡ | 16434 | 29679 | 16082‡ | 15552‡ | 26658 | 13343 | |||

| BUSCO completeness (%) | 88.4 | 72.2 | 34.3 | 71 | |||||||

| Mean exon length (bp) | 245 | 262‡ | 230 | 240 | 226 | 218 | 354 | 208 | 314 | ||

| Mean intron length (bp) | 667 | 917‡ | 952 | 1146 | 1119 | 1047 | 638 | 800 | 898 | 80 | |

| Protein length (mean aa) | 455 | 615‡ | 424 | 413 | 450‡ | 475‡ | 517 | 331 | 154 | 280 |

†Computed as total occurrences for non-error 31-mers divided by homozygous-peak depth (Dovetail Genomics).

‡Calculated in this study using GAG based on publicly available data.

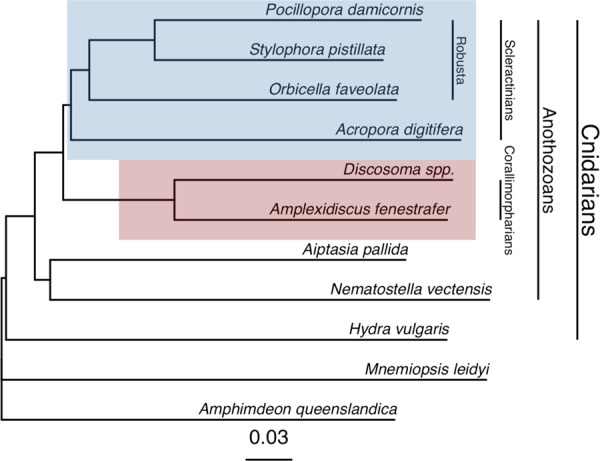

Genomic feature frequency phylogeny

Feature frequency profiling shows the phylogenetic relationships among the genomes analyzed here (Fig. 1). This genome-scale analysis resolves the Complexa (A. digitifera) and Robusta branches (P. damicornis, S. pistillata, O. faveolata) of the scleractinians as a monophyletic sister clade to the corallimorpharians, lending further support to the conclusions of Lin et al.32 that corallimorpharians are not ‘naked corals’.

Figure 1.

Genome phylogeny. Feature frequency profiling of protein-coding gene models produces a genome scale phylogeny that supports a monophyletic scleractinian clade (blue) with corallimorpharians as a sister clade (red). Bootstrap support from 100 pseudoreplicates was 100% at every node.

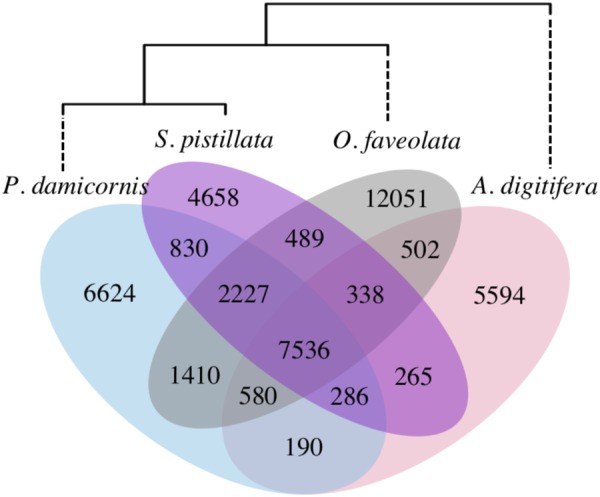

Scleractinian gene content and core function

Gene families were identified by ortholog clustering across the 11 genomes in Table 1 (Supplementary Data S1). Across all four scleractinian genomes, we identified 43,580 ortholog groups ranging in size from 1 to 566 genes, with 14,653 of these gene families present in more than one coral species. That only a third of ortholog groups occurred in multiple genomes suggests high divergence among scleractinians, consistent with the findings of Voolstra et al.17. The highest number of shared ortholog groups occurred between P. damicornis and S. pistillata, the two most closely related species, and a dendrogram based on shared gene content33 reproduces the evolutionary relationships among the four corals34 (Fig. 2). Although gene content in O. faveolata is more similar overall to the other robust corals than the complex A. digitifera, O. faveolata also has the highest number of species-specific gene families, which may reflect its large genome size and/or adaptations to the Atlantic Ocean.

Figure 2.

Species-specific and shared gene families across four scleractinian genomes. Numbers indicate gene families, including both single-copy genes and multi-copy gene families. Dendrogram is based on shared gene content, following33.

A total of 7,536 ortholog groups were found in all four scleractinian genomes, constituting putative coral ‘core’ genes. Members of these core gene families comprised 46.6% of all P. damicornis genes, and functional profiling of the core genome revealed significant enrichment of 44 GO terms associated with basic cellular and metabolic functions, including nucleic acid synthesis and processing, cellular signaling and transport, and lipid, carbohydrate, and protein metabolism (Supplementary Data S2). This basic functionality explains why >30% of these gene families were also found in all other cnidarians, and 96.3% had orthologs in at least one non-coral. This is consistent with the identification of basic housekeeping functions in the core (shared) protein sets in other comparative studies10,17.

Genes specific to and diversified in scleractinians are enriched for immune functionality

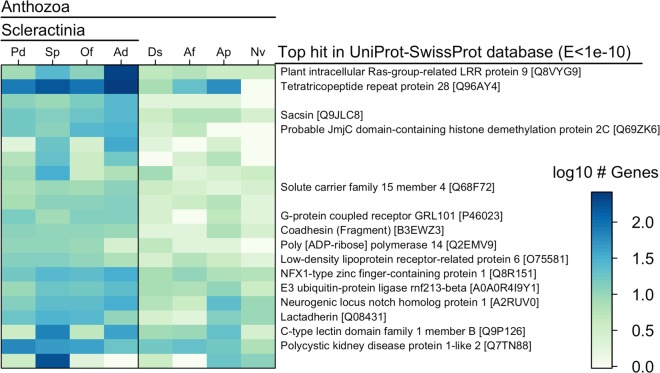

A subset of the coral core gene families (n = 278; 3.7%) had no orthologs outside the Scleractinia, suggesting they may reflect important evolutionary innovations within this group35. (We refer to these genes as ‘coral-specific’ since they did not have orthologs in the non-scleractinian genomes analyzed here, yet these may still show sequence or domain similarity with genes in other organisms and in reference databases.) Other gene families (n = 21) were significantly larger in scleractinians than other anthozoans (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.01; Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1), indicating gene family expansion that may underlie adaptation to the scleractinian condition36,37. Genes belonging to both coral-specific and coral-diversified families in P. damicornis were enriched for GO terms involved in cellular signaling and immunity (Table 2), and showed significant similarity to proteins with known immune function (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Heatmap showing gene ortholog groups that were larger in scleractinians compared to other cnidarians (Pd = P. damicornis, Sp = S. pistillata, Of = O. faveolata, Ad = A. digitifera, Nv = N. vectensis, Ap = A. pallida, Ds = Discosoma sp., Af = A. fenestrafer). For each ortholog group, the longest protein sequence from P. damicornis was compared to the UniProt-SwissProt database using blastp, and the top hit was selected based on the lowest E-value (if < 1e-10). Uniprot accession numbers are shown in brackets. Sequences with no annotation had no hits to the SwissProt database with E < 1e-10. Gene family sizes and E-values for SwissProt hits can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2.

Enrichment of GO terms in the coral-specific and coral-diversified genes in P. damicornis. Of the coral-specific genes (n = 349), 184 (53%) had GO annotations. Of the coral-diversified genes (n = 339), 229 (68%) had GO annotations.

| Gene set | GO Accession | GO Term Name | Observed | Expected | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coral-specific | GO:0035434 | copper ion transmembrane transport | 2 | 0.10 | 0.004000 |

| GO:0007165 | signal transduction | 32 | 23.78 | 0.004200 | |

| GO:0046654 | tetrahydrofolate biosynthetic process | 1 | 0.01 | 0.012300 | |

| GO:0051092 | NF-kappaB activation | 1 | 0.02 | 0.024500 | |

| GO:0070836 | caveola assembly | 1 | 0.04 | 0.036500 | |

| GO:0051607 | defense response to virus | 2 | 0.32 | 0.040300 | |

| GO:0006355 | regulation of gene-specific transcription | 12 | 6.06 | 0.045600 | |

| GO:0000183 | chromatin silencing at rDNA | 1 | 0.05 | 0.048400 | |

| GO:0045132 | meiotic chromosome segregation | 1 | 0.05 | 0.048400 | |

| Coral-diversified | GO:0006857 | oligopeptide transport | 3 | 0.05 | 0.000015 |

| GO:0007264 | small GTPase mediated signal transduction | 6 | 1.05 | 0.000600 | |

| GO:0001822 | kidney development | 2 | 0.05 | 0.000850 | |

| GO:0006468 | protein phosphorylation | 11 | 3.82 | 0.001960 | |

| GO:0007219 | Notch signaling pathway | 2 | 0.11 | 0.004980 | |

| GO:0033151 | V(D)J recombination | 1 | 0.01 | 0.007680 | |

| GO:0045737 | positive regulation of CDK activity | 1 | 0.01 | 0.007680 | |

| GO:0008152 | metabolic process | 31 | 30.87 | 0.012710 | |

| GO:0016255 | attachment of GPI anchor to protein | 1 | 0.04 | 0.037840 |

Immune-related GO terms that were significantly enriched in the coral-specific gene set included viral defense, signal transduction, and NF-κB pathway regulation (Table 2). NF-κB signaling plays a central role in innate immunity38,39, and was recently demonstrated to be conserved and responsive to immune challenge in the coral O. faveolata40. Signal transduction was associated with 32 coral-specific genes that showed significant similarity to dopamine receptors, neuropeptide receptors, G-protein coupled receptors, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) (Supplementary Data S3), potentially representing other coral-specific immune pathways. Indeed, the TNF receptor superfamily is more diverse in corals than any organism described thus far other than choanoflagellates9,41, with 40 proteins in A. digitifera. The P. damicornis genome contained 39 proteins with TNFR cysteine-rich domains, suggesting that diversification of this repertoire may be a common feature of corals. Another enriched GO term in the coral-specific gene set was caveola assembly–the formation of structures in cell membranes that anchor transmembrane proteins–which may also play a role in signal transduction and immunity42.

The coral-diversified gene families (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S1) showed high similarity to receptors for pathogen recognition, such as a C-type lectin, G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and both Notch and Wnt-signaling receptors (lipoprotein receptor-related protein). Notch and Wnt signaling are critical developmental gene pathways with potentially diverse roles in coral biology, but which also have a role in coral innate immunity43, particularly in wound-healing processes39,44. Other coral-diversified genes were similar to Ras-related proteins with leucine-rich repeats, and a tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein, which may play roles in signal transduction45. Many of these tetratricopeptide repeat proteins also contained a CHAT domain characteristic of caspases46, indicating a potential role in apoptotic signaling and/or coral bleaching. Other coral-diversified genes were similar to Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, which may act as an anti-apoptotic signal transducer47, and lactadherin, which may be involved in phagocytosis and clearance of apoptotic cells48. Genes previously found to be differentially expressed in corals under stress or immune challenge were also found in the coral-diversified gene set, including the HSP70 co-chaperone sacsin49, the oligopeptide transporter solute carrier family 1550, and NFX1-type zinc finger protein51. Together, these results suggest that corals as a group have evolved a diverse set of immune signaling genes for interacting with and responding to pathogens and the environment. Importantly, the immune repertoire in corals also contains many other important gene families that are not discussed here (e.g., Toll-like receptors)39,40, since we focus only on those that are specific to or diversified in corals.

In addition to defending against pathogens, many of the immune pathways highlighted here may mediate the establishment and maintenance of symbiosis, including with beneficial bacteria and the Symbiodiniaceae15. Indeed, lectins and other pattern recognition receptors have previously been shown to regulate symbiont uptake and specificity7,52,53, while caspases have previously been shown to mediate bleaching and symbiont removal through apoptosis54. We also found that copper ion transmembrane transport was highly enriched in the coral-specific gene set (Table 2), which may reflect an important role for delivery of copper to endosymbionts, where it is a critical component of photosynthetic proteins (plastocyanin) and antioxidants (superoxide dismutase)55. For example, in mycorrhizal symbioses, fungi are known to deliver copper to their photosynthetic plant partners56, and shortage of trace metals such as copper has recently been linked to coral bleaching57.

In addition to immunity and symbiosis, the genes specific to and diversified within corals may underlie other unique scleractinian traits. Calcium carbonate skeleton formation, for example, may be linked to the diversification of calcium ion channels (e.g., polycystins) and cell adhesion proteins (e.g., coadhesin, Fig. 3), which have previously been identified as components of the skeletal organic matrix6,58. Corals may also have diversified mechanisms for controlling gene expression, evidenced by the enrichment of transcriptional regulation and chromatin silencing functions in the coral-specific gene set (Table 2), and the diversification of a histone demethylation protein family (Fig. 3). Finally, we note that some enriched GO annotations do not translate directly to corals (e.g., kidney development), and/or are only represented by a single gene (Table 2), and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

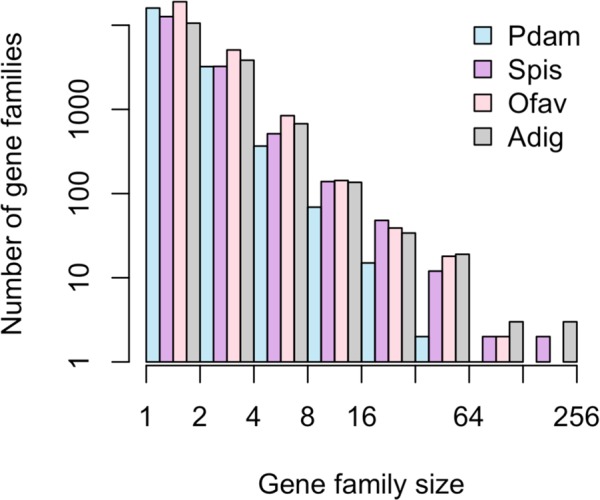

Within-species gene diversification also highlights immune function in scleractinians

The expansion of gene families within individual lineages may represent an important mechanism of molecular evolution driving adaptation and speciation36. Consistent with patterns of gene family size in other organisms59, the number of coral gene families decreased exponentially as gene family size increased (Fig. 4). P. damicornis had smaller gene families overall, and the fewest large gene families (n = 3 with size > 32, max size = 75), while A. digitifera had the most large gene families (n = 25 with size > 32, max size = 255), consistent with pervasive gene duplication in this species suggested by Voolstra et al.17. However, statistical comparison of shared gene family sizes across the four coral species, accounting for differences in total gene content, indicated that S. pistillata had the most significantly expanded gene families (n = 16), followed by A. digitifera (n = 11). Even though O. faveolata had the highest number of non-shared gene families (Fig. 2), only one shared gene family was significantly expanded, suggesting that its large genome size is the result of species-specific genes and/or even expansion of shared gene content. Finally, P. damicornis had no significantly expanded gene families relative to the other scleractinians, confirming that uneven gene family size17 and lineage-specific gene family expansion is common in the Scleractinia.

Figure 4.

Gene family size distribution in four coral genomes. Pdam = P. damicornis, Spis = S. pistillata, Ofav = O. faveolata, Adig = A. digitifera. Bars represent the total number of gene families in a given size class using exponential binning, with each interval open on the left (i.e., the first interval contains gene families of size 1, the second interval contains gene families of size 2 and 3, etc.).

Among the gene families showing lineage-specific expansions in corals, several were similar to reverse transcriptases and transposable elements (Supplementary Table S2); these may represent ‘genetic parasites’ that propagate across the genome60, but they may also play crucial roles in genome evolution and the regulation of gene expression61. Annotations of other expanded gene families (Supplementary Table S2) suggest important roles in interacting with the environment, cellular signaling, and immunity. While uneven gene family size could also reflect variation in assembly completeness and quality of genome assemblies62, these annotations are consistent with categories of genes known to undergo lineage-specific expansion across eukaryotes45.

One expanded gene family in A. digitifera was similar to NOD-like receptors (NLRs), which are cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors that play a key role in pathogen detection and immune activation63. Characterized by the presence of NACHT domains, NLR genes are highly diversified and variable in number in the genomes of cnidarians64 and other species60. The expansion of this gene family in A. digitifera is consistent with these observations, and may represent adaptation to a new pathogen environment65, or to species-specific symbiotic interactions with microbial eukaryotes and prokaryotes39. Another expanded gene family in A. digitifera was similar to ephrin-like receptors, which may mediate signaling cascades and cell to cell communication66. In S. pistillata, one expanded gene family was similar to tachylectin-2, a pattern recognition receptor that has been identified in many cnidarians39. Previously, a tachylectin-2 homolog was found to be under selection in the coral Oculina67, providing more evidence that such genes are involved in adaptive evolution in corals. The one significantly expanded gene family in O. faveolata did not have a strong hit in the SwissProt database, but did contain a caspase-like domain suggesting a role in apoptosis, which was recently linked to disease susceptibility in this species68. Overall, differential expansion of genes related to the immune system is consistent with the findings of Voolstra et al.17, and suggests that this phenomenon is a general attribute of corals. Lineage-specific immune diversification in corals and other taxa may reflect interactions with specific consortia of eukaryotic and prokaryotic microbial symbionts69.

In addition to putative immune-related function, genes that have undergone lineage-specific expansions in corals may also play roles in biomineralization, which could contribute to variation in growth and morphology among coral species. For example, one significantly expanded gene family in A. digitifera was similar to a CUB and peptidase domain-containing protein that was found to be secreted in the skeletal organic matrix58, and another in S. pistillata was similar to fibrillar collagen with roles in biomineralization70.

Although the P. damicornis genome did not contain any gene families that were significantly expanded relative to the other corals, it did contain many genes (n = 6,966, 26.7%) with no orthologs in other genomes. While most of these P. damicornis-specific genes were unannotatable, protein domain homology revealed significant enrichment for 11 GO terms, including G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling pathway, bioluminescence, activation of NF-κB-inducing kinase, and positive regulation of JNK cascade (Table 3). The mitogen-activated protein kinase JNK plays a role in responses to stress stimuli, inflammation, and apoptosis71. JNK prevents the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in corals in response to thermal and UV stress, and inhibition of JNK leads to coral bleaching and cell death72. The NF-κB transcription factor may also link oxidative stress and apoptosis involved in coral bleaching73, in addition to its central role in innate immunity39. The occurrence of lineage-specific genes that may function in these pathways indicates that P. damicornis may have evolved unique immune strategies for coping with environmental stress.

Table 3.

Enrichment of GO terms in the P. damicornis-specific gene set. This gene set included 6,966 genes, of which 1,498 (22%) had GO annotations.

| GO Accession | GO Term Name | Observed | Expected | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0007186 | G-protein coupled receptor signaling pathway | 407 | 149.36 | <1e-30 |

| GO:0008218 | bioluminescence | 15 | 3.24 | 6.00E-08 |

| GO:0007250 | activation of NF-kappaB-inducing kinase activity | 10 | 3.48 | 0.0014 |

| GO:0046330 | positive regulation of JNK cascade | 10 | 3.48 | 0.0014 |

| GO:0007165 | signal transduction | 478 | 231.92 | 0.0018 |

| GO:0035278 | miRNA mediated inhibition of translation | 5 | 1.68 | 0.0196 |

| GO:0007411 | axon guidance | 3 | 0.72 | 0.0261 |

| GO:0035385 | Roundabout signaling pathway | 3 | 0.72 | 0.0261 |

| GO:0006814 | sodium ion transport | 11 | 6.25 | 0.0419 |

| GO:0050482 | arachidonic acid secretion | 5 | 2.04 | 0.0446 |

| GO:0015074 | DNA integration | 11 | 6.37 | 0.0474 |

An expanded role of immunity in P. damicornis may explain how Pocillopora has achieved such a widespread distribution18,19. Indeed, Pocillopora corals function as fast-growing and weedy pioneer species in Hawaii74, on the Great Barrier Reef75, and in the eastern tropical Pacific (ETP)76. In fact, in the ETP, where the coral used in this study was collected from, Pocillopora thrives in marginal habitats, often dealing with elevated turbidity and reduced salinity after heavy rainfall events, subaerial exposure during extreme low tides, and both warm- and cold-water stress due to ENSO events and periodic upwelling77. A diversified immune system may also allow for flexibility in symbiosis, which may further contribute to the success of Pocillopora26,78. While the wide distribution of P. damicornis suggests there may be considerable variation in its genome that is not captured by our sample from the ETP, this work provides a foundation for future genomic analysis in this important coral species.

Conclusions

This comparative analysis revealed significant expansion of immune-related pathways within the Scleractinia, and further lineage-specific diversification within each scleractinian species. Different immune genes were diversified in each species (e.g., Nod-like and tachylectin-like receptors in A. digitifera and S. pistillata, and caspase-like and JNK signaling genes in O. faveolata and P. damicornis), suggesting diverse adaptive roles for innate immune pathways. Indeed, immune pathways govern the interactions between corals and their algal endosymbionts15,79, the susceptibility of corals to disease80, and their responses to environmental stress72. Therefore, prominent diversification of immune-related functionality across the Scleractinia is not surprising, and may underlie responses to selection involving symbiosis, self-defense, and stress-susceptibility.

The function and diversity of both the Scleractinia-specific and the species-specific immune repertoires deserve further study as they could prove to be critical for coral survival in the face of climate change. Indeed, factors placing high selection pressure on corals, such as bleaching and disease, both involve challenges to the immune system. Lineage-specific adaptations indicate corals continue to evolve novel immune-related functionality in response to niche-specific selection pressures. These results suggest that evolution of the innate immune system has been a defining feature of the success of scleractinian corals, and likewise may mediate their continued success under climate change scenarios.

Methods

P. damicornis genome sequencing and assembly

The P. damicornis genotype used for sequencing was collected from Saboga Is., Panama in March 2005, and cultured indoors at the University of Miami Coral Resource Facility until the time of sampling. Genomic DNA was extracted from two healthy fragments and two bleached fragments of this genotype in September 2016 using a Qiagen DNAeasy Midi kit and shipped overnight on dry ice to Dovetail Genomics (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The bleached sample (low symbiont load) was used for DNA extraction for shotgun libraries (sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqX) for de novo assembly, since this step is more sensitive to contamination. The unbleached sample was used for DNA extraction for Chicago libraries (sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500), since this step is more sensitive to DNA size and quality but less sensitive to contamination. Genome scaffolds were assembled de novo using the HiRise software pipeline81. The Dovetail HiRise scaffolds were then filtered to remove those of potential non-coral origin using BLAST82 searches against three databases: (1) Symbiodiniaceae, containing the genomes of Breviolum minutum83 and Symbiodinium microadriaticum84, (2) Bacteria, containing 6,954 complete bacterial genomes from NCBI, and (3) viruses, containing 2,996 viral genomes from the phantome database (phantome.org; accessed 2017-03-01). Scaffolds with a BLAST hit to any of these databases with an e-value < 10−20 and a bitscore > 1000 were considered to be non-coral in origin and removed from the assembly85.

P. damicornis genome annotation

The filtered assembly was analyzed for completeness using BUSCO86 to search for 978 universal metazoan single-copy orthologs. The–long option was passed to BUSCO in order to train the ab initio gene prediction software Augustus87. Augustus gene prediction parameters were then used in the MAKER pipeline88 to annotate gene models, using as supporting evidence two RNA-seq datasets from P. damicornis89,90, one from closely-related S. pistillata17, and protein sequences from 20 coral species10. Results from this initial MAKER run were used to train a second gene predictor (SNAP)91 prior to an iterative MAKER run to refine gene models. Predicted protein sequences were then extracted from the assembly and putative functional annotations were added by searching for homologous proteins in the UniProt Swiss-Prot database92 using BLAST (E < 10−5), and protein domains using InterProScan93. Genome annotation summary statistics were generated using the Genome Annotation Generator software94. All data and code to reproduce these annotations as well as subsequent comparative genomic and statistical analyses is available at github.com/jrcunning/pdam-genome.

Comparative genomic analyses

We compared the predicted protein sequences of four scleractinians, two corallimorpharians, two actiniarians, one hydrozoan, one sponge, and one ctenophore (Table 1), by feature frequency profiling (FFP v3.19)95 using features of length 8 to create a whole genome phylogeny for these organisms (Fig. 1). We then identified ortholog groups (gene families) among the predicted proteins from these genomes using the software fastOrtho (http://enews.patricbrc.org/fastortho/) based on the MCL algorithm with a blastp E-value cutoff of 10−5. Based on these orthologous gene families, we defined and extracted several gene sets of interest: (1) gene families that were shared by all four scleractinians (i.e., coral ‘core’ genes), (2) gene families that were present in all four scleractinians but absent from other organisms (i.e., coral-specific genes), (3) gene families that were significantly larger in scleractinians relative to other anthozoans (Binomial generalized linear model, FDR-adjusted p < 0.01; i.e., coral-diversified genes), (4) gene families that were significantly larger in each scleractinian species relative to other scleractinians (pairwise comparisons using Fisher’s exact test, FDR-adjusted p < 0.01; i.e., coral species-specific gene family expansions), and (5) genes present in P. damicornis with no orthologs in any other genome (i.e., P. damicornis-specific genes).

Functional characterization

Putative gene functionality was characterized using Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. GO terms were assigned to predicted P. damicornis protein sequences using InterProScan96. Significantly enriched GO terms in gene sets of interest relative to the whole genome were identified using the R package topGO97,98. These analyses were implemented using custom scripts available in the accompanying data repository (github.com/jrcunning/pdam-genome).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

RC was supported by NSF OCE-1358699 to AB. We thank PW Glynn for the original field collection of the P. damicornis genotype used for genome sequencing.

Author Contributions

N.T.K. conceived and directed sequencing of the genome of P. damicornis, which was cultured by P.G. R.C., R.A.B., and N.T.K. designed the comparative genomic study. R.C. and R.A.B. analyzed the data, and R.C. prepared figures, tables, and the first draft of this manuscript. All authors reviewed, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data and code to reproduce the analyses and figures described herein can be found at github.com/jrcunning/pdam-genome. The full genome assembly and annotation is archived and publicly available at NCBI (BioProject PRJNA454489; BioSample SAMN09007954; Genome RCHS00000000), and in the reefgenomics database99 (http://pdam.reefgenomics.org/).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

R. Cunning, Email: ross.cunning@gmail.com

N. Traylor-Knowles, Email: ntraylorknowles@rsmas.miami.edu

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-34459-8.

References

- 1.Costanza R, et al. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Glob. Environ. Change. 2014;26:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowlton, N. et al. Coral reef biodiversity. Life in the World’s Oceans: Diversity Distribution and Abundance 65–74 (2010).

- 3.Kleypas JA, et al. Geochemical consequences of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science. 1999;284:118–120. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jokiel PL, Coles SL. Effects of temperature on the mortality and growth of Hawaiian reef corals. Mar. Biol. 1977;43:201–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00402312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard J, et al. Projections of climate conditions that increase coral disease susceptibility and pathogen abundance and virulence. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015;5:688. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeuchi T, Yamada L, Shinzato C, Sawada H, Satoh N. Stepwise Evolution of Coral Biomineralization Revealed with Genome-Wide Proteomics and Transcriptomics. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0156424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neubauer EF, Poole AZ, Weis VM, Davy SK. The scavenger receptor repertoire in six cnidarian species and its putative role in cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2692. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer CV, Traylor-Knowles N. Towards an integrated network of coral immune mechanisms. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2012;279:4106–4114. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quistad SD, et al. Evolution of TNF-induced apoptosis reveals 550 My of functional conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:9567–9572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405912111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharya, D. et al. Comparative genomics explains the evolutionary success of reef-forming corals. Elife5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.van Oppen MJH, Oliver JK, Putnam HM, Gates RD. Building coral reef resilience through assisted evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:2307–2313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422301112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixon GB, et al. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science. 2015;348:1460–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1261224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bay RA, Rose NH, Logan CA, Palumbi SR. Genomic models predict successful coral adaptation if future ocean warming rates are reduced. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1701413. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole AZ, Weis VM. TIR-domain-containing protein repertoire of nine anthozoan species reveals coral–specific expansions and uncharacterized proteins. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014;46:480–488. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poole AZ, Kitchen SA, Weis VM. The Role of Complement in Cnidarian-Dinoflagellate Symbiosis and Immune Challenge in the Sea Anemone Aiptasia pallida. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:519. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinzato C, et al. Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature. 2011;476:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voolstra CR, et al. Comparative analysis of the genomes of Stylophora pistillata and Acropora digitifera provides evidence for extensive differences between species of corals. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:17583. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17484-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veron, J. E. N. Corals of the World (2000).

- 19.Pinzón JH, et al. Blind to morphology: genetics identifies several widespread ecologically common species and few endemics among Indo-Pacific cauliflower corals (Pocillopora, Scleractinia) J. Biogeogr. 2013;40:1595–1608. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt-Roach, S., Miller, K. J. & Lundgren, P. With eyes wide open: a revision of species within and closely related to the Pocillopora damicornis species complex (Scleractinia; Pocilloporidae) using morphology …. Zool. J. Linn. Soc (2014).

- 21.Johnston EC, et al. A genomic glance through the fog of plasticity and diversification in. Pocillopora. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5991. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoddart JA. Genetical structure within populations of the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Mar. Biol. 1984;81:19–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00397621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinzón JH, LaJeunesse TC. Species delimitation of common reef corals in the genus Pocillopora using nucleotide sequence phylogenies, population genetics and symbiosis ecology. Mol. Ecol. 2011;20:311–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Combosch DJ, Vollmer SV. Population genetics of an ecosystem-defining reef coral Pocillopora damicornis in the Tropical Eastern Pacific. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas L, Kennington WJ, Evans RD, Kendrick GA, Stat M. Restricted gene flow and local adaptation highlight the vulnerability of high-latitude reefs to rapid environmental change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017;23:2197–2205. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glynn PW, Maté JL, Baker AC, Calderón MO. Coral bleaching and mortality in panama and ecuador during the 1997–1998 El Niño–Southern Oscillation Event: spatial/temporal patterns and comparisons with the 1982–1983 event. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001;69:79–109. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGinley MP, et al. Symbiodinium spp. in colonies of eastern Pacific Pocillopora spp. are highly stable despite the prevalence of low-abundance background populations. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012;462:1–7. doi: 10.3354/meps09914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunning R, Baker AC. Excess algal symbionts increase the susceptibility of reef corals to bleaching. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012;3:259. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoddart JA. Asexual production of planulae in the coral Pocillopora damicornis. Mar. Biol. 1983;76:279–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00393029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward S. Evidence for broadcast spawning as well as brooding in the scleractinian coral Pocillopora damicornis. Mar. Biol. 1992;112:641–646. doi: 10.1007/BF00346182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt-Roach S, Miller KJ, Woolsey E, Gerlach G, Baird AH. Broadcast spawning by Pocillopora species on the Great Barrier Reef. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50847. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin MF, et al. Corallimorpharians are not ‘naked corals’: insights into relationships between Scleractinia and Corallimorpharia from phylogenomic analyses. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2463. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snel B, Bork P, Huynen MA. Genome phylogeny based on gene content. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:108–110. doi: 10.1038/5052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukami H, et al. Mitochondrial and nuclear genes suggest that stony corals are monophyletic but most families of stony corals are not (Order Scleractinia, Class Anthozoa, Phylum Cnidaria) PLoS One. 2008;3:e3222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khalturin K, Hemmrich G, Fraune S, Augustin R, Bosch TCG. More than just orphans: are taxonomically-restricted genes important in evolution? Trends Genet. 2009;25:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharpton TJ, et al. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 2009;19:1722–1731. doi: 10.1101/gr.087551.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kondrashov FA. Gene duplication as a mechanism of genomic adaptation to a changing environment. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2012;279:5048–5057. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatada EN, Krappmann D, Scheidereit C. NF-κB and the innate immune response. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:52–58. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mydlarz, L. D., Fuess, L., Mann, W., Pinzón, J. H. & Gochfeld, D. J. Cnidarian Immunity: From Genomes to Phenomes. in The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future: The world of Medusa and her sisters (eds. Goffredo, S. & Dubinsky, Z.) 441–466 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

- 40.Williams LM, et al. A conserved Toll-like receptor-to-NF-κB signaling pathway in the endangered coral Orbicella faveolata. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018;79:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quistad SD, Traylor-Knowles N. Precambrian origins of the TNFR superfamily. Cell Death Discov. 2016;2:16058. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel HH, Insel PA. Lipid rafts and caveolae and their role in compartmentation of redox signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009;11:1357–1372. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson DA, Walz ME, Weil E, Tonellato P, Smith MC. RNA-Seq of the Caribbean reef-building coral Orbicella faveolata (Scleractinia-Merulinidae) under bleaching and disease stress expands models of coral innate immunity. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1616. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DuBuc TQ, Traylor-Knowles N, Martindale MQ. Initiating a regenerative response; cellular and molecular features of wound healing in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. BMC Biol. 2014;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schapire AL, Valpuesta V, Botella MA. TPR Proteins in Plant Hormone Signaling. Plant Signal. Behav. 2006;1:229–230. doi: 10.4161/psb.1.5.3491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aravind, L. & Koonin, E. V. Classification of the caspase–hemoglobinase fold: detection of new families and implications for the origin of the eukaryotic separins. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Iwata H, et al. PARP9 and PARP14 cross-regulate macrophage activation via STAT1 ADP-ribosylation. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12849. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ait-Oufella H, et al. Lactadherin deficiency leads to apoptotic cell accumulation and accelerated atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2168–2177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss Y, et al. The acute transcriptional response of the coral Acropora millepora to immune challenge: expression of GiMAP/IAN genes links the innate immune responses of corals with those of mammals and plants. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:400. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moya A, et al. Near-future pH conditions severely impact calcification, metabolism and the nervous system in the pteropod Heliconoides inflatus. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016;22:3888–3900. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeSalvo MK, et al. Differential gene expression during thermal stress and bleaching in the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata. Mol. Ecol. 2008;17:3952–3971. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood-Charlson EM, Hollingsworth LL, Krupp DA, Weis VM. Lectin/glycan interactions play a role in recognition in a coral/dinoflagellate symbiosis. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1985–1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kvennefors ECE, Leggat W, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Degnan BM, Barnes AC. An ancient and variable mannose-binding lectin from the coral Acropora millepora binds both pathogens and symbionts. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2008;32:1582–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paxton CW, Davy SK, Weis VM. Stress and death of cnidarian host cells play a role in cnidarian bleaching. J. Exp. Biol. 2013;216:2813–2820. doi: 10.1242/jeb.087858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Festa RA, Thiele DJ. Copper: an essential metal in biology. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:R877–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.González-Guerrero M, Escudero V, Saéz Á, Tejada-Jiménez M. Transition Metal Transport in Plants and Associated Endosymbionts: Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Rhizobia. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1088. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferrier-Pagès Christine, Sauzéat Lucie, Balter Vincent. Coral bleaching is linked to the capacity of the animal host to supply essential metals to the symbionts. Global Change Biology. 2018;24(7):3145–3157. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramos-Silva P, et al. The skeletal proteome of the coral Acropora millepora: the evolution of calcification by co-option and domain shuffling. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2099–2112. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huynen MA, van Nimwegen E. The frequency distribution of gene family sizes in complete genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:583–589. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schiffer Philipp, Gravemeyer Jan, Rauscher Martina, Wiehe Thomas. Ultra Large Gene Families: A Matter of Adaptation or Genomic Parasites? Life. 2016;6(3):32. doi: 10.3390/life6030032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brawand D, et al. The genomic substrate for adaptive radiation in African cichlid fish. Nature. 2014;513:375–381. doi: 10.1038/nature13726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hahn MW, Han MV, Han S-G. Gene family evolution across 12 Drosophila genomes. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanneganti T-D, Lamkanfi M, Núñez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007;27:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamada M, et al. The complex NOD-like receptor repertoire of the coral Acropora digitifera includes novel domain combinations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:167–176. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stein C, Caccamo M, Laird G, Leptin M. Conservation and divergence of gene families encoding components of innate immune response systems in zebrafish. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R251. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-11-r251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kullander K, Klein R. Mechanisms and functions of Eph and ephrin signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:475–486. doi: 10.1038/nrm856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hayes ML, Eytan RI, Hellberg ME. High amino acid diversity and positive selection at a putative coral immunity gene (tachylectin-2) BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fuess Lauren E., Pinzón C Jorge H., Weil Ernesto, Grinshpon Robert D., Mydlarz Laura D. Life or death: disease-tolerant coral species activate autophagy following immune challenge. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;284(1856):20170771. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nyholm SV, Graf J. Knowing your friends: invertebrate innate immunity fosters beneficial bacterial symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:815–827. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Christiansen HE, Lang MR, Pace JM, Parichy DM. Critical early roles for col27a1a and col27a1b in zebrafish notochord morphogenesis, vertebral mineralization and post-embryonic axial growth. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Newton K., Dixit V. M. Signaling in Innate Immunity and Inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2012;4(3):a006049–a006049. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Courtial L, et al. The c-Jun N-terminal kinase prevents oxidative stress induced by UV and thermal stresses in corals and human cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:45713. doi: 10.1038/srep45713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weis VM. Cellular mechanisms of Cnidarian bleaching: stress causes the collapse of symbiosis. J. Exp. Biol. 2008;211:3059–3066. doi: 10.1242/jeb.009597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grigg RW, Maragos JE. Recolonization of Hermatypic Corals on Submerged Lava Flows in Hawaii. Ecology. 1974;55:387–395. doi: 10.2307/1935226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Connell JH. Population ecology of reef-building corals. Biology and geology of coral reefs. 1973;2:205–245. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-395526-5.50015-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glynn PW, Stewart RH, McCosker JE. Pacific coral reefs of Panama: structure, distribution and predators. Geol. Rundsch. 1972;61:483–519. doi: 10.1007/BF01896330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glynn, P. W. et al. Eastern Pacific Coral Reef Provinces, Coral Community Structure and Composition: An Overview. In Coral Reefs of the Eastern Tropical Pacific: Persistence and Loss in a Dynamic Environment (eds Glynn, P. W., Manzello, D. P. & Enochs, I. C.) 107–176 (Springer Netherlands, 2017).

- 78.Rowan R. Coral bleaching: thermal adaptation in reef coral symbionts. Nature. 2004;430:742. doi: 10.1038/430742a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davy SK, Allemand D, Weis VM. Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:229–261. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Libro S, Kaluziak ST, Vollmer SV. RNA-seq profiles of immune related genes in the staghorn coral Acropora cervicornis infected with white band disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Putnam NH, et al. Chromosome-scale shotgun assembly using an in vitro method for long-range linkage. Genome Res. 2016;26:342–350. doi: 10.1101/gr.193474.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shoguchi E, et al. Draft assembly of the Symbiodinium minutum nuclear genome reveals dinoflagellate gene structure. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:1399–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aranda M, et al. Genomes of coral dinoflagellate symbionts highlight evolutionary adaptations conducive to a symbiotic lifestyle. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:39734. doi: 10.1038/srep39734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Baumgarten S, et al. The genome of Aiptasia, a sea anemone model for coral symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:11893–11898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513318112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stanke M, Steinkamp R, Waack S, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene finding in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W309–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campbell MS, Holt C, Moore B, Yandell M. Genome Annotation and Curation Using MAKER and MAKER-P. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2014;48(4):11.1–39. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0411s48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Traylor-Knowles N, et al. Production of a reference transcriptome and transcriptomic database (PocilloporaBase) for the cauliflower coral, Pocillopora damicornis. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:585. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mayfield AB, Wang Y-B, Chen C-S, Lin C-Y, Chen S-H. Compartment-specific transcriptomics in a reef-building coral exposed to elevated temperatures. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:5816–5830. doi: 10.1111/mec.12982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.The UniProt Consortium UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Finn RD, et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D190–D199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Geib, S. M. et al. Genome Annotation Generator: A simple tool for generating and correcting WGS annotation tables for NCBI submission. Gigascience, 10.1093/gigascience/giy018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Sims GE, Kim S-H. Whole-genome phylogeny of Escherichia coli/Shigella group by feature frequency profiles (FFPs) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:8329–8334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105168108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alexa, A. & Rahnenfuhrer, J. topGO: enrichment analysis for gene ontology. R package version2 (2010).

- 98.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liew, Y. J., Aranda, M. & Voolstra, C. R. Reefgenomics.Org - a repository for marine genomics data. Database2016 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Prada C, et al. Empty Niches after Extinctions Increase Population Sizes of Modern Corals. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:3190–3194. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang X, et al. Draft genomes of the corallimorpharians Amplexidiscus fenestrafer and Discosoma sp. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017;17:e187–e195. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Putnam NH, et al. Sea anemone genome reveals ancestral eumetazoan gene repertoire and genomic organization. Science. 2007;317:86–94. doi: 10.1126/science.1139158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chapman JA, et al. The dynamic genome of Hydra. Nature. 2010;464:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nature08830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ryan JF, et al. The genome of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi and its implications for cell type evolution. Science. 2013;342:1242592. doi: 10.1126/science.1242592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Srivastava M, et al. The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature. 2010;466:720–726. doi: 10.1038/nature09201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and code to reproduce the analyses and figures described herein can be found at github.com/jrcunning/pdam-genome. The full genome assembly and annotation is archived and publicly available at NCBI (BioProject PRJNA454489; BioSample SAMN09007954; Genome RCHS00000000), and in the reefgenomics database99 (http://pdam.reefgenomics.org/).