Abstract

We recently reported the medicinal chemistry re-optimization of a series of compounds derived from the human tyrosine kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, for activity against Plasmodium falciparum. From this same library of compounds, we now report potent compounds against Trypanosoma brucei brucei (which causes human African trypanosomiasis), T. cruzi (the pathogen that causes Chagas disease), and Leishmania spp. (which cause leishmaniasis). In addition, sub-micromolar compounds were identified that inhibit proliferation of the parasites that cause African animal trypanosomiasis, T. congolense and T. vivax. We have found that this set of compounds display acceptable physicochemical properties and represent progress towards identification of lead compounds to combat several neglected tropical diseases.

Author summary

As part of our efforts to identify compounds that are active against the parasite that causes malaria (P. falciparum), we employed a “parasite hopping” approach in our drug discovery efforts. This involved screening a library of demonstrated antiparasitic agents against other parasites responsible for a host of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) including Chagas disease (T. cruzi), human African trypanosomiasis (T. brucei) and cutaneous leishmaniasis (L. major). The compounds we identified generally show improved selectivity for the parasite of interest over the mammalian cell lines tested and, from this work, we have made progress towards the identification of lead compounds against multiple NTDs.

Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are a collection of 20 communicable diseases [1]. Though mostly treatable and/or preventable, NTDs remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality affecting over 1 billion people worldwide. Many of the current treatments have significant side effects, poor efficacy and there are increasing reports of resistance in the literature [2, 3] highlighting the need for novel chemotherapeutics. Collectively, 17 of these NTDs account for 26 million disability-adjusted life years (DALY) [4], which is a sum of years of life lost due to premature mortality and those lost due to ill health or disability. In addition, livestock are also susceptible to various parasitic infections, and can lead to the development of diseases such as African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT), which has devastating economic effects on communities. AAT is caused by infection with T. congolense or T. vivax [5], and of the three main chemotherapeutics currently listed for treatment, diminazene aceturate and isometamidium chloride are the most widely used [6], though reports of resistance are increasing to both of these [7–8].

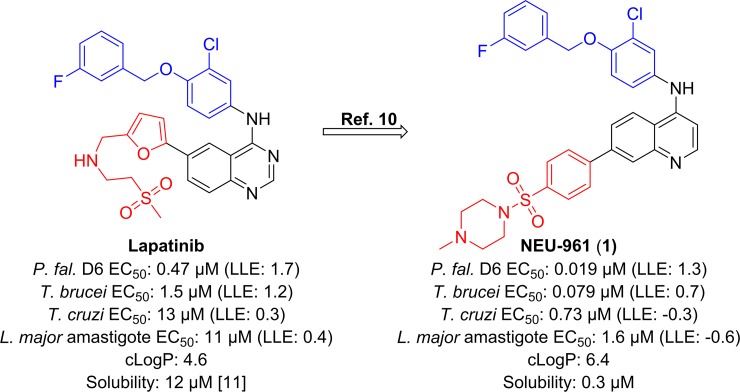

As part of our efforts to identify new drugs for human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), we undertook a target class repurposing project [9], wherein we screened known human tyrosine kinase inhibitors against a number of pathogenic protozoan parasites (Fig 1). Historically, we have cross-screened our compounds against P. falciparum, T.b. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major to fully leverage chemical space covered by our optimization campaign [10]. This cross-screening led to the identification of 1 [10] as a potent inhibitor of proliferation of P. falciparum, T.b. brucei and T. cruzi. Herein, we report the results of a screening campaign using a set of previously reported, structurally related compounds previously optimized for their activity against P. falciparum [11]. We screened these compounds for activity against T.b. brucei, T. cruzi and L. major and we also report activity data for a subset of these compounds against T. congolense and T. vivax. The previously reported P. falciparum data for these compounds, along with additional screening data that is not discussed directly in this study, is provided in the Supplementary Information, S1 Table.

Fig 1. Project progression has led to the identification of potent inhibitors of P. falciparum, T.b. brucei, T. cruzi, and L. major through variations of the head region (shown in blue) and the linker/tail region (shown in red) from lapatinib [12] to compounds typified by 1.

Desired ranges for physicochemical properties: cLogP: ≤3, lipophilic ligand efficiency (LLE = pEC50—cLogP): ≥4 [13], aqueous solubility: > 10 μM.

Established target product profiles for Chagas disease, leishmaniasis and HAT, were used to define hit and lead candidate criteria (summarized in the Supplementary Information, S2 Table) [14–15]. We note that, according to a committee coordinated by the Global Health Innovative Technology Fund (GHIT), a hit compound for Chagas disease or leishmaniasis should have an EC50 < 10 μM [15].

Results and discussion

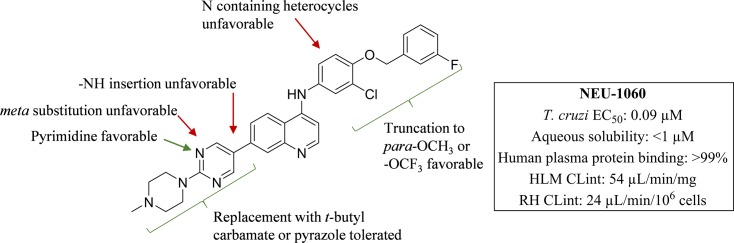

Trypanosoma cruzi

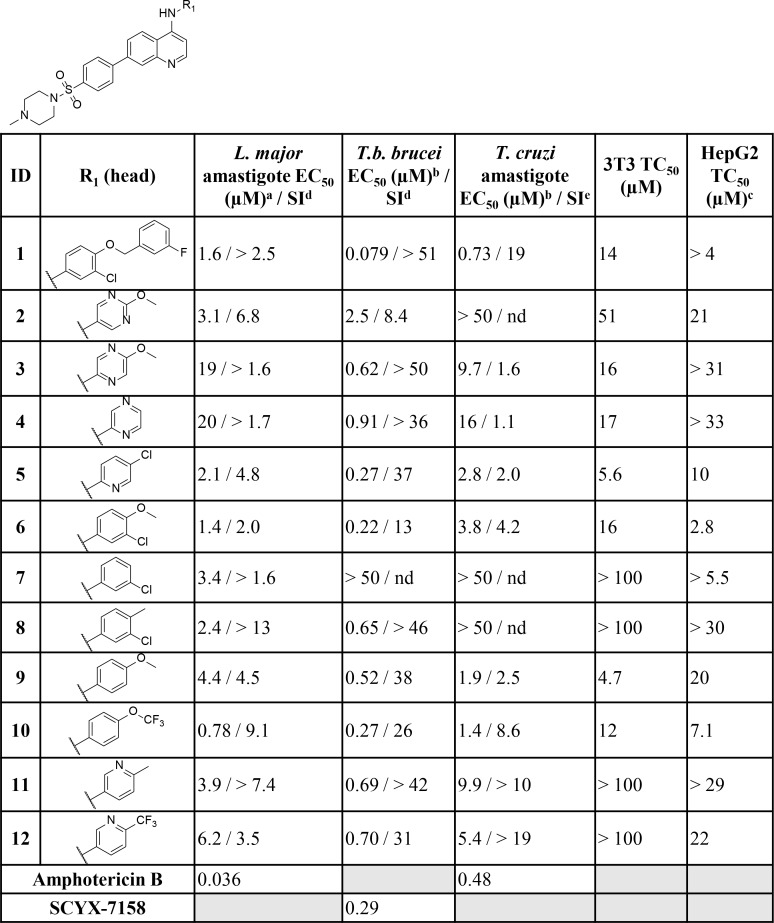

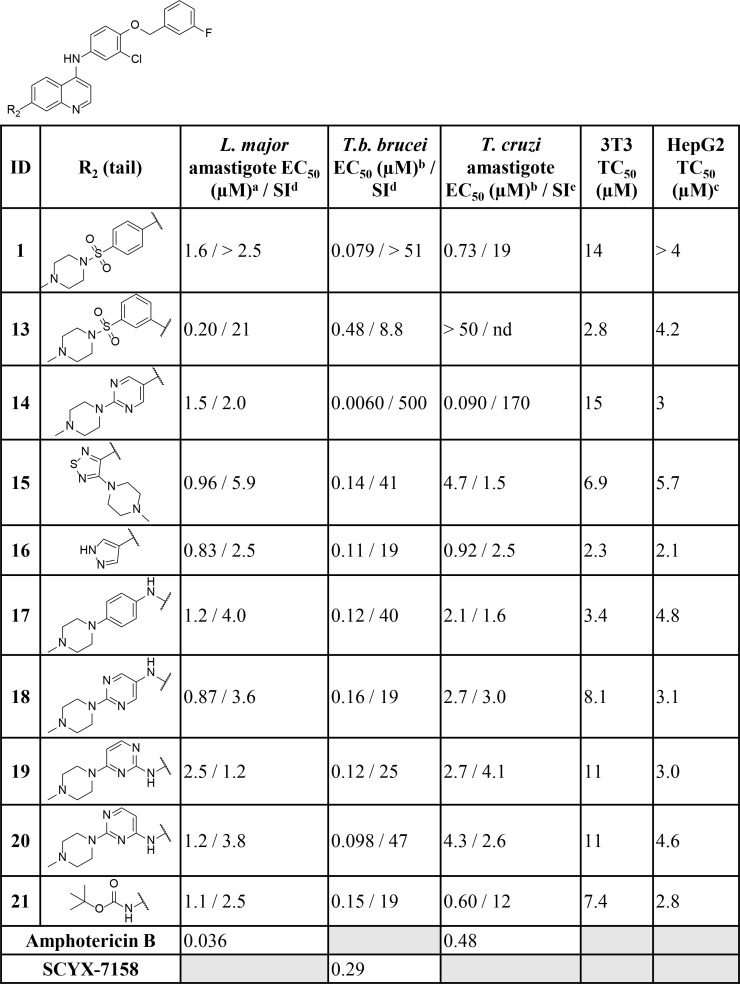

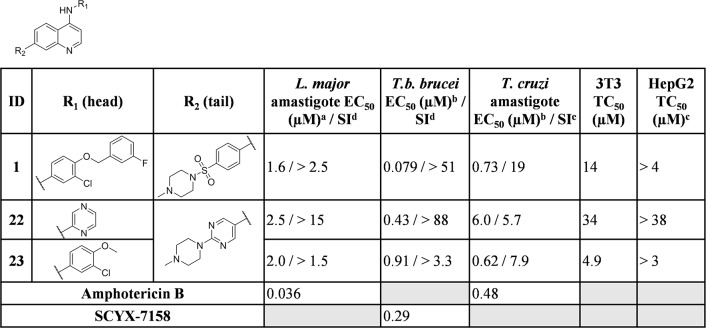

When tested against intracellular T. cruzi parasites, several compounds displayed low micromolar inhibition of T. cruzi, and these included truncated head groups 3-chloro-4-methoxyphenyl (6, EC50: 3.8 μM) and para-methoxyphenyl (9, EC50: 1.9 μM), as well as the para-trifluoromethoxyphenyl (10, EC50: 1.4 μM) analog (Fig 2). Removal of the phenylsulfonamide and replacement with the para-substituted pyrimidine (14, EC50: 0.090 μM) (Fig 3) led to the most potent compound against T. cruzi identified in this series and afforded a significant boost in selectivity index (SI) versus 3T3 cells (SI: 170). Other submicromolar compounds were identified, such as the pyrazole analog (16, EC50: 0.92 μM) and the t-butyl carbamate (21, EC50: 0.60 μM), though selectivity versus 3T3 cells was an issue for 16 in particular (SI: 2.5). An additional compound, 23 (EC50: 0.62 μM) (Fig 4), had an improved lipophilic ligand efficiency [13] (LLE; 1.8 compared to -0.29 for 1, see Supplementary Information, S3 Table for a complete list of values) and maintained potent inhibition of T. cruzi, though the aqueous solubility was poor (<1 μM, see Supplementary Information, S4 Table for complete list of ADME values) and the human liver microsome intrinsic clearance (HLM Clint: 170 μL/min/mg), and rat hepatocyte intrinsic clearance (RH Clint: 45 μL/min/106 cells) were both high. Importantly, host cell toxicity (3T3 cells) was generally low for the series, and the selectivity index (SI) was above the targeted 10×EC50 threshold. The general SAR trends observed for this series against T. cruzi are summarized in Fig 5.

Fig 2. Biological activity of key compounds with varying head groups (denoted by R1) against L. major amastigote, T.b. brucei, T. cruzi cultures and HepG2 human cells.

Data for the full screening set is summarized in the supplementary information. nd = not determined aAll r2 values are >0.9 unless noted otherwise bAll SEM values within 25% except for 1 where EC50 T. cruzi 0.73 (SEM: 0.2; 27%) cTested concentration ranges were determined based on compound solubility dSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to HepG2 cells. eSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to 3T3 cells.

Fig 3. Biological activity of key compounds with varying tail groups (denoted by R2) against L. major amastigote, T.b. brucei, T. cruzi cultures and HepG2 human cells.

Data for the full screening set is summarized in the supplementary information. nd = not determined aAll r2 values are >0.9 unless noted otherwise bAll SEM values within 25% except for 1 where EC50 T. cruzi 0.73 (SEM: 0.2; 27%) cTested concentration ranges were determined based on compound solubility dSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to HepG2 cells. eSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to 3T3 cells.

Fig 4. Biological activity of key compounds that combine head (R1) and tail (R2) groups against L. major amastigote, T.b. brucei, T. cruzi cultures and HepG2 human cells. Data for the full screening set is summarized in the supplementary information.

nd = not determined aAll r2 values are >0.9 unless noted otherwise bAll SEM values within 25% except for 1 where EC50 T. cruzi 0.73 (SEM: 0.2; 27%) cTested concentration ranges were determined based on compound solubility dSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to HepG2 cells. eSelectivity index (SI) calculated relative to 3T3 cells.

Fig 5. SAR summary around this series for potent anti-T. cruzi activity.

Leishmania major

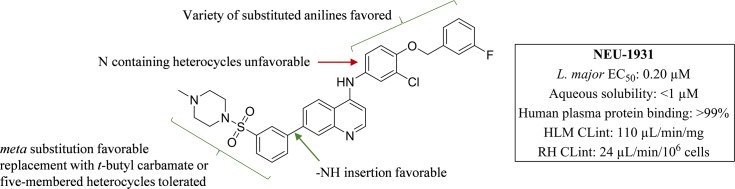

Some of the SAR trends observed with T. cruzi were mirrored in L. major. Truncation of the head group to the 3-chloro-4-methoxyphenyl (6, EC50: 1.4 μM), 3-chlorophenyl (7, EC50: 3.4 μM), para-methoxyphenyl (9, EC50: 4.4 μM), and the para-trifluoromethoxyphenyl (10, EC50: 0.78 μM) all led to potent analogs (Fig 2). In addition, several pyridyl (5, and 11), and pyrimidine (2) derivatives exhibited potent inhibition (EC50 values ranging from 2.1–3.9 μM). The meta- substituted sulfonamide analog (13) was the most potent compound identified (EC50: 0.20 μM) and suggested that the change in vector may be favorable (Fig 3). This idea was supported by the thiadiazole analog 15 (EC50: 0.96 μM) which possesses a more acute vector than 13 yet maintains potency. In addition, compound activity remained upon removal of the tail group (red in Fig 1) and replacement with the t-butyl carbamate (21, EC50: 1.1 μM) or pyrazole (16, EC50: 0.83 μM). Finally, removal of the sulfonamide and replacement with the pyrimidine (14; EC50: 1.5 μM), as well as incorporation of an -NH linker (17–20), led to several compounds with low-micromolar inhibition (EC50 values ranging from 0.87–2.5 μM) of L. major. Importantly, host cell toxicity (HepG2) was found to be low for these analogs and the SI was greater than the 10×EC50 threshold that was targeted. The general SAR trends around this series for activity against L. major are summarized in Fig 6.

Fig 6. Series SAR summary for anti-L. major activity.

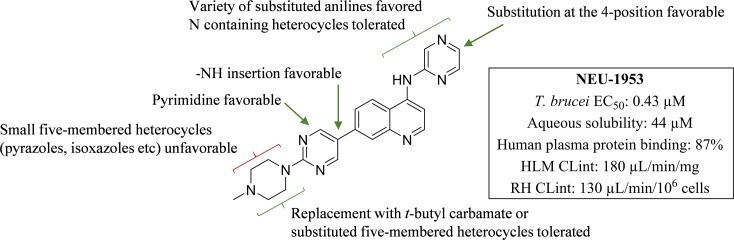

Trypanosoma brucei brucei

With a reduction of the lipophilicity of the head group several sub-micromolar inhibitors of T.b. brucei, including para substituted pyridines (5, 11 and 12; EC50 values ranging from 0.27–0.70 μM), pyrazines (3 and 4; EC50: 0.62 and 0.91 μM respectively) and several substituted anilines (6, 8 and 10; EC50 values ranging from 0.22–0.65 μM) were identified (Fig 2). Replacement of the phenylsulfonamide with the pyrimidine (14; EC50: 0.0060 μM) (Fig 3) led to a 10-fold improvement in potency over 1 (EC50: 0.079 μM). Additionally, incorporation of an -NH linker led to compounds with an improvement in potency (17–20; EC50 values ranging from 0.098–0.16 μM). A combination of the pyrazine head group with the pyrimidine tail (22; EC50: 0.43 μM) (Fig 4) produced a sub-micromolar inhibitor of T.b. brucei proliferation. This compound had a significantly improved LLE above the desired range (4.3), and improved aqueous solubility (44 μM), though HLM (Clint: 180 μL/min/mg) and RH clearance (Clint: 130 μL/min/106 cells) are still of concern and require further optimization. The general SAR trends around this series for activity against T.b. brucei are summarized in Fig 7.

Fig 7. SAR summary around this series for potent anti T.b. brucei activity.

Given the activity observed against T.b. brucei, a selection of compounds that demonstrated sub-micromolar inhibition of T.b. brucei were further profiled against T. congolense and T. vivax, which are the main causative agents for African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT) (Table 1), to determine how well the activity translated to these closely related kinetoplastids [5]. All of the analogs screened were observed to be sub-micromolar against both T. congolense and T. vivax. Compounds 22 and 23 were observed to be more potent than diminazene for T. congolense (EC50: 0.050 μM), and T. vivax (EC50: 0.040 μM), respectively. None of the compounds tested were more potent than isometamidium against either species.

Table 1. Biological activity against T. congolense and T. vivax.

| ID | T. b. brucei EC50 (μM) | T. congolense EC50 (μM) | T. vivax EC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.080 | 0.14 | 0.040 |

| 6 | 0.22 | 0.86 | 0.16 |

| 14 | 0.0060 | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| 15 | 0.14 | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| 16 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.15 |

| 21 | 0.15 | 0.83 | 0.29 |

| 22 | 0.43 | 0.050 | 0.72 |

| 23 | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.040 |

| Diminazene | 0.0090 | 0.13 | 0.10 |

| Isometamidium | nt | 0.0060 | 0.00012 |

nt = not tested

We selected the most promising T. brucei inhibitor (14) for pharmacokinetic (PK) analysis on the basis of its high potency (EC50: 0.0060 μM). PK parameters were measured for both brain and plasma following a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) dose of 10 mg/kg (see Supplementary information, S5 and S6 Tables). To achieve efficacy in the in vivo acute HAT model, we were aiming to exceed 10×EC50 for 6–8 h, though at this dose we were only able to exceed these levels for 4 h in plasma (see Supplementary information, S1 Fig). Further, 14 had an excellent brain to plasma exposure ratio of 7.4, which was encouraging given CNS exposure is required to treat stage 2 HAT infections, when parasites have crossed the blood-brain barrier [16].

Given that the PK results of 14 indicated a higher dose would be required to achieve 10×EC50, we administered a single i.p. dose of 25 mg/kg in a murine model of acute HAT. Control mice received an i.p. dose of drug vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide, 3.4 mL/kg). There was no evidence of toxicity and a 10-fold reduction in parasitemia was observed in 75% of mice dosed with 14 while one had no detectable parasitemia (see Supplementary information, S2 Fig).

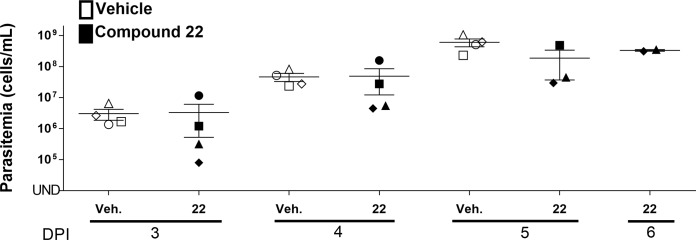

Given the improvements in the overall ADME profile of 22, coupled with its sub-micromolar inhibition of T.b. brucei we sought to progress it into an efficacy study. Mice were administered orally (p.o.) once daily 60 mg/kg for the first three days post-infection. Observing no signs of toxicity, the dose was increased to 70 mg/kg for the remaining three days of treatment. Control mice received a p.o. dose of drug vehicle (10% NMP and 90% PEG, 10 mL/kg). By day 5, there was no statistically significant difference between the control group and the group treated with 22 (Fig 8).

Fig 8. Parasitemia levels of T. b. brucei infected mice treated with 60 mg/kg 22 for the first three days post-infection before the dose was increased to 70 mg/kg for the remainder of the study, compared with the control group (10% NMP and 90% PEG only).

Compound 22 and vehicle were administered once p.o. on Day 1 post-infection. Parasitemia in the blood collected from the tail vein was determined on Days 2–6 post-infection. UND: Undetectable parasitemia (<2×104 cells/mL), the black horizontal line in each group indicates the median parasitemia level. The different shapes are representative of each mouse in the group. NS: Not significant. The error bar indicates the standard error of the mean (SEM). The significance of the difference in the mean parasitemia of treated and untreated groups was analyzed by Student’s T-test.

In summary, by screening a series of anti-P. falciparum proliferation inhibitors against kinetoplastids, we have identified several potent compounds against T. cruzi, L. major, and T.b. brucei. When taken in its entirety, this set of compounds generally shows low host cell toxicity and the analogs had good to excellent selectivity for the parasite of interest. Of note was the identification of 22 which exhibited potent inhibition of T.b. brucei, and an improved ADME profile but, when it was progressed into an in vivo model of acute HAT infection, failed to affect parasitemia. We are working to ascertain the reasons for the lack of translation from in vitro to in vivo and we continue to pursue further optimization of this series as anti-trypanosomal and anti-leishmanial lead compounds, the results of which will be reported in due course.

Materials and methods

Trypanosoma brucei

The assay was performed following a previously reported procedure [17]. Briefly, in a 96-well plate, compounds were added in triplicates at 50 μM and in serial dilutions 1:2 in HMI-9 medium. To each well, 100 μL of 2.5×103 T. b. brucei (strain 427, received as a gift from Dr. C. C. Wang at UCSF) in HMI-9 medium was were added and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 48 h. Following incubation, 20 μL of PrestoBlue were added to each well and incubated for additional 4 h. Fluorescence was read at 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission. Suramin at 100 μM was used as positive control and reference for calculation of IC50.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the USA Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accreditation guidelines. All mice were maintained in the University of Georgia Animal Facility under pathogen-free conditions. The protocol (AUP # A2013 06-011-A10) was approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mouse infection with T. b. brucei

Bloodstream form (BSF) T. brucei brucei CA427 parasites were maintained at densities below 1×106 cells/mL in HMI-9 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 10% SERUM PLUS (Sigma), and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic Solution (Corning cellgro) at 37°C, 5% CO2 [18]. Parasites were centrifuged at 5000 xg for 3 min at room temperature and resuspended in cold 1xPBS containing 1% glucose to yield a solution of 2.5×106 cells/mL. Correct cell density following resuspension was confirmed using a Z2 Coulter Counter (Beckman). Parasite viability was observed by motility with a Neubauer Bright-line hemocytometer. Cells were kept on ice until infection.

Compound 14 –on day 0, female Swiss-Webster mice (8–10 weeks old, 20–25 g, n = 4 per group) (Harlan) were infected i.p. with 2.5×105 trypanosomes by injecting 100 μL of resuspension using 26G needles. Day 1 to 3 post-infection, mice received a single i.p. dose of either drug vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide, 3.4 mL/kg) (Fisher Scientific) or drug (14, 25 mg/kg). Parasitemia was determined on days 2 and 3 post-infection by collecting 3 μL of blood from the tail vein.

Compound 22 –on day 0, female Swiss-Webster mice (8–10 weeks old, 20–25 g, n = 4 per group) were infected i.p. with 1×105 trypanosomes by injecting 100 μL of resuspension using 26G needles. Day 1 to 3 post-infection, mice received a single p.o. dose of either drug vehicle (10% NMP and 90% PEG, 10 mL/kg) (Fisher Scientific) or drug (22, 60 mg/kg). From days 4 to 6, the dose was increased to 70 mg/kg for the mice in the treatment group. Parasitemia was determined on days 3 to 6 post-infection by collecting 3 μL of blood from the tail vein.

Blood samples were mixed with 21 μL of RBC Lysis Solution (Qiagen) and incubated at room temperature for 15–45 min prior to observing for parasites by hemocytometer. Humane euthanasia by CO2 overdose followed by incision to form a bilateral pneumothorax was conducted on mice at study termination. All animal experimental protocols were approved and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Georgia.

Trypanosoma cruzi

In a 96-well plate, 5×104 3T3 cells in DMEM without phenol red supplemented with 2% FBS were added to each well. Cells were incubated for 2 h to allow for attachment. Compounds were added in triplicates at 50 μM and in serial dilutions 1:2. To each well, 5×104 T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Tulahuen strain expressing β-galactosidase) were added and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 96 h. Following incubation, 50 μL of 500 μM chlorophenol Red-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% NP40 was added to each well and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 h. Absorbance was read at 590–595 nm. Amphotericin B at 4 μM was used as positive control and reference for calculation of EC50.

Trypanosoma congolense

In vitro drug sensitivity assay for T. congolense (72 h): Compounds were tested in vitro for efficacy against the IL3000 T. congolense (drug sensitive) strain which was originally derived from the Trans Mara I strain, isolated from a bovine in 1966 in Kenya [19]. In brief, test compounds were prepared as 10 mg/mL DMSO stocks for each assay run, data points were averaged and EC50 values were determined using Softmax Pro 5.2 (Molecular Devices, Inc.). Compounds were assayed in at least three separate, independent experiments and an 11-point dilution curve was used to determine the EC50 values. Bloodstream form trypanosomes were supported in HMI-9 medium containing 20% bovine serum and were incubated with test compounds for 69 h at 34°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Thereafter, 10 μL of Resazurin dye (12.5 mg in 100 mL of phosphate-buffered saline, Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland) was added for an additional 3 h. Plates were read using a fluorescence plate reader (Spectramax, Gemini XS, Bucher Biotec, Basel, Switzerland) using an excitation wavelength of 536 nm and an emission wavelength of 588 nm.

Trypanosoma vivax

Ex vivo drug sensitivity assay for T. vivax (48 h): Compounds were tested ex vivo against the STIB 719 / ILRAD 560 T. vivax (drug sensitive) strain which originated from the Y486 strain, isolated from a naturally infected bovine in 1976 in Zaria, Nigeria [19]. Compounds were assayed in at least three separate, independent experiments and an 11-point dilution curve was used to determine the EC50 values. Bloodstream form trypanosomes were harvested from a highly parasitaemic mouse (via cardiac puncture) and were incubated with test compounds for 45 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2, supported in HMI-9 medium containing 20% bovine serum. Thereafter, Resazurin dye was added to monitor trypanosome viability as described in the preceding section.

Leishmania major

Amastigote assays were performed using pLEXSY-hyg2-luciferase L. major transfected promastigotes and the murine RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line (ATCC TIB-71, Manassas, VA). Briefly, luciferase-expressing promastigotes of each Leishmania species were generated by adding a luciferase encoding region to the pLEXSY-hyg2 vector (Jena Biosciences, Germany) as described [20]. One μg of the linearized pLEXSY-hyg2-luciferase vector were electroporated (480 V, 13 Ω, and 500 μF) into 4×107 Leishmania promastigotes. Selection for stable promastigote transfectants was carried out using hygromycin B (100 μg/mL). RAW 264.7 macrophages were maintained in growth medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with heat-inactivated 10% FBS (Life Technologies)). Cells were harvested and resuspended in growth medium at 2.0×105 cells/mL, and 1×104 cells/well were dispensed (final volume 50 μL) in each well of a 384 well tissue-culture treated white plate using a EVO Freedom liquid handling system (Tecan, Durham, NC). Plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h after which the culture medium was removed from each well using the EVO Freedom liquid handler. Metacyclic phase pLEXSY-hyg2-luciferase-Leishmania promastigotes (MOI = 1:10 L. major) were added to each assay plate well and allowed to infect the RAW 264.7 macrophages. After an overnight incubation, the growth medium was aspirated and each well was washed three times with 40 μL of fresh growth medium to remove non-internalized promastigotes. After the third wash, 69.2 μL of growth medium was added to each well. Compound dilutions (final concentration ranges 0.5–10,000 ng/mL) were generated and dispensed using the liquid handling system. Compound treated plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 96 h. After incubation, 7.5 μL of a luciferin solution (Caliper Life Science, Waltham, MA) diluted to 150 μg/mL was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Data were captured using an Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan). EC50s were generated for each concentration response test using GraphPad Prism software 6.0.

Drug toxicity to 3T3 cells

In a 96-well plate, 5×104 NIH/3T3 (ATCC CRL-1658) cells (purchased from ATCC) in DMEM without phenol red supplemented with 2% FBS were added to each well. Cells were incubated for 2 h to allow for attachment. Compounds were added in triplicates at 200 μM and in serial dilutions 1:2 and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 96 h. Ionomycin at 100 μM was used as positive control and reference for calculation of EC50. Following incubation, 10 μL of Alamar Blue (ThermoFisher) were added to each well and cells incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 4 h. Absorbance was read at 590–595 nm.

Drug toxicity to HepG2 cells [21]

HepG2 cells were cultured in complete Minimal Essential Medium prepared by supplementing MEM with 0.19% sodium bicarbonate, 10% heat inactivated FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino, 0.009 mg/mL insulin, 1.76 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 20 units/mL penicillin–streptomycin, and 0.05 mg/mL gentamycin. HepG2 cells cultured in complete MEM were first washed with 1× Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Invitrogen #14175095), trypsinized using a 0.25% trypsin/EDTA solution, assessed for viability using trypan blue, and resuspended at 250,000 cells/mL. Using a Tecan EVO Freedom robot, 38.3 μL of cell suspension were added to each well of clear, cell culture-treated 384-well microtiter plates for a final concentration of 9570 liver cells per well, and plated cells were incubated overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Drug plates were prepared with the Tecan EVO Freedom using sterile 96 well plates containing twelve duplicate 1.6-fold serial dilutions of each test compound suspended in DMSO. 4.25 μL of diluted test compound was then added to the 38.3 μL of media in each well providing a 10%-fold final dilution of compound. Compounds were tested from a range of 57 ng/mL to 10,000 ng/mL for all assays. Mefloquine was used as a plate control for all assays with a concentration ranging from 113 ng/mL to 20,000 ng/mL. After a 48 h incubation period, 8 μL of a 1.5 mg/mL solution of MTT diluted in complete MEM media was added to each well. All plates were subsequently incubated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the media and drugs in each well was removed by shaking the plate over sink, and the plates were left to dry in a fume hood for 15 mins. Next, 30 μL of isopropanol acidified by addition of HCl at a final concentration of 0.36% was added to dissolve the formazan dye crystals created by reduction of MTT. Plates are put on a 3-D rotator for 15–30 mins. Absorbance was determined in all wells using a Tecan iControl 1.6 Infinite plate reader. The 50% toxic concentrations (TC50) were then generated for each toxicity dose response test using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA) using the nonlinear regression (sigmoidal dose-response/variable slope) equation.

Supporting information

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

Academic licenses to OpenEye Scientific Software and ChemAxon for their suites of programs are gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to AstraZeneca for performing the in vitro ADME experiments tabulated in the Supplementary Information and to GALVmed for granting us access to their platform for T. congolense and T. vivax drug discovery.

Data Availability

All relevant data are included in the manuscript or supporting information files.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI082577 and R21AI127594 (M.P.P.), R56AI099476 and R01AI124046 (to MPP and KM-W). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Neglected Tropical Diseases. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ponte-Sucre A, Gamarro F, Dujardin J-C, Barrett MP, López-Vélez R, et al. (2017) Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 11: e0006052 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fairlamb AH, Gow NAR, Matthews KR, Waters AP (2016) Drug resistance in eukaryotic microorganisms. Nature Microbiology 1: 16092 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, et al. (2012) Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 380: 2197–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auty H, Anderson NE, Picozzi K, Lembo T, Mubanga J, et al. (2012) Trypanosome Diversity in Wildlife Species from the Serengeti and Luangwa Valley Ecosystems. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 6: e1828 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giordani F, Morrison LJ, Rowan TG, De Koning HP, Barrett MP (2016) The animal trypanosomiases and their chemotherapy: a review. Parasitology 143: 1862–1889. 10.1017/S0031182016001268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geerts S, Holmes PH, Eisler MC, Diall O (2001) African bovine trypanosomiasis: the problem of drug resistance. Trends in Parasitology 17: 25–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delespaux V, de Koning HP (2007) Drugs and drug resistance in African trypanosomiasis. Drug Resistance Updates 10: 30–50. 10.1016/j.drup.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klug DM, Gelb MH, Pollastri MP (2016) Repurposing strategies for tropical disease drug discovery. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 26: 2569–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devine W, Woodring JL, Swaminathan U, Amata E, Patel G, et al. (2015) Protozoan Parasite Growth Inhibitors Discovered by Cross-Screening Yield Potent Scaffolds for Lead Discovery. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 58: 5522–5537. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta N, Ferrins L, Leed SE, Sciotti RJ, Pollastri MP (2018) Optimization of Physicochemical Properties for 4-Anilinoquinoline Inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum Proliferation. ACS Infectious Diseases 4: 577–591. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Fan C, Guo Z, Li Y, Zhao S, et al. (2013) Discovery of a potent dual EGFR/HER-2 inhibitor L-2 (selatinib) for the treatment of cancer. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 69: 833–841. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopkins AL, Keserü GM, Leeson PD, Rees DC, Reynolds CH (2014) The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 13: 105 10.1038/nrd4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ (2001) Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings1PII of original article: S0169-409X(96)00423-1. The article was originally published in Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 23 (1997) 3–25.1. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 46: 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katsuno K, Burrows JN, Duncan K, van Huijsduijnen RH, Kaneko T, et al. (2015) Hit and lead criteria in drug discovery for infectious diseases of the developing world. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 14: 751 10.1038/nrd4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrins L, Rahmani R, Baell JB (2013) Drug discovery and human African trypanosomiasis: a disease less neglected? Future Medicinal Chemistry 5: 1801–1841. 10.4155/fmc.13.162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas SM, Purmal A, Pollastri M, Mensa-Wilmot K (2016) Discovery of a Carbazole-Derived Lead Drug for Human African Trypanosomiasis. Scientific Reports 6: 32083 10.1038/srep32083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirumi H, Hirumi K (1994) Axenic culture of African trypanosome bloodstream forms. Parasitology Today 10: 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillingwater K, Kunz C, Braghiroli C, Boykin DW, Tidwell RR, et al. (2017) In vitro, Ex vivo and In vivo Activity of Diamidines against Trypanosoma congolense and Trypanosoma vivax. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lecoeur H, Buffet P, Morizot G, Goyard S, Guigon G, et al. (2007) Optimization of Topical Therapy for Leishmania major Localized Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Using a Reliable C57BL/6 Model. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 1: e34 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrari M, Fornasiero MC, Isetta AM (1990) MTT colorimetric assay for testing macrophage cytotoxic activity in vitro. Journal of Immunological Methods 131: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the manuscript or supporting information files.