Abstract

Facets of positive psychological well-being, such as optimism, have been identified as positive health assets because they are prospectively associated with the seven metrics of cardiovascular health (CVH) and improved outcomes related to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Connections between psychological well-being and cardiovascular conditions may be mediated through biological, behavioral, and psychosocial pathways. Individual-level interventions, such as mindfulness-based programs and positive psychological interventions, have shown promise for modifying psychological well-being. Further, workplaces are utilizing well-being-focused interventions to promote employee CVH, which represents a potential model for expanding psychological well-being programs to communities and societies. Given psychological wellbeing’s relevance for promoting CVH, we outline clinical recommendations to assess and promote well-being in patient encounters. Finally, a research agenda is proposed. Additional prospective observational studies are needed to understand mechanisms underlying the connection between psychological well-being and cardiovascular outcomes. Moreover, rigorous intervention trials are needed to assess whether psychological well-being-promoting programs can improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular health, health behaviors, optimism, positive psychological well-being

Condensed abstract:

Positive psychological well-being and its specific components, such as optimism, predict superior levels of cardiovascular health (CVH) metrics and fewer cardiac events, likely through behavioral, biological, and psychosocial pathways. Individual-, group-, and organization-level approaches to promote psychological well-being have shown promise and could be applied more broadly to communities and society. A guide to assessing psychological well-being and implementing well-being-promoting activities is provided to support application of this knowledge in clinical practice. Next-step research should include continued observational studies to understand the mechanisms linking psychological well-being with CVH, along with rigorous, well-powered psychological well-being intervention trials in diverse settings and populations.

Introduction

Associations between adverse psychological factors, such as depression, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are well-established. However, accumulating evidence suggests that positive psychological well-being (hereafter, psychological well-being)—which includes positive thoughts and feelings such as purpose in life, optimism, and happiness—has its own independent associations with lower risk of CVD and may promote cardiovascular health (CVH; 1). As part of the present JACC Cardiovascular Health Promotion Series (1,2), we focus on psychological well-being and its role in CVH promotion and CVD prevention.

In recent years, the fields of preventive cardiology and positive psychology have both set ambitious goals that go beyond simply reducing risk of disease to include increasing healthy longevity, improving quality of life, preserving good mental health and cognitive function, and achieving health care savings (3). Relevant metrics have been developed alongside those goals. For example, the American Heart Association (AHA) recently proposed a definition of CVH that has become widely accepted (4) and comprises seven components: four health behaviors (healthy diet, physical activity, abstinence from tobacco, and normal body mass index [BMI]) and three health factors (favorable blood pressure, total cholesterol, and glucose). CVH has been prospectively linked with reduced risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, as well as lower incidence and burden of many chronic diseases of aging (5).

For its part, psychological well-being has been defined in various ways and encompasses the positive thoughts and feelings that individuals use to evaluate their lives favorably (1). Two distinct theoretical perspectives have informed characterizations of psychological well-being: the eudaimonic approach defines well-being according to one’s ability to identify meaningful life pursuits and striving to achieve one’s best (6); the hedonic approach defines well-being according to pursuing and attaining pleasure and happiness (7). Other, less easily classified, facets of psychological well-being (e.g., optimism, emotional vitality) have also been identified, several of which consistently predict cardiovascular outcomes (1). Moreover, it is increasingly clear that effects of psychological well-being and distress are not simply two sides of the same coin. Indeed, research has shown that the absence of psychological distress does not necessarily denote the presence of psychological well-being (8). Thus, psychological well-being should be investigated as an independent predictor of CVH.

Pathophysiological and Beneficial Effects

Psychological Health and Cardiovascular Health

Investigations of psychological factors in relation to CVH have variously considered the 7 CVH components individually or in various combinations as a composite score of “favorable” or “ideal” CVH. In these studies, psychological distress was associated with poor CVH (e.g., 9), but none were prospective in design, making the directionality of the associations unclear. In contrast, while still limited in number, some initial studies in the U.S. and Europe using both cross-sectional and prospective designs have suggested that psychological well-being promotes CVH (10,11).

Psychological Health and Cardiovascular Disease

Numerous reviews and meta-analyses have evaluated the role of depression (12,13), anxiety (14), anger (15), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; 16), and chronic stress in relation to the development of CVD (17). For example, a 2014 meta-analysis of 30 prospective studies (including 40 independent reports) based on 893,850 participants with follow-up periods ranging from 2–37 years, found depression consistently predicted excess risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD; 13). This finding is consistent with other meta-analyses regarding the magnitude of risk and the presence of a dose-response relationship. Findings for anxiety, PTSD, anger, and hostility are similar. Anxiety and PTSD appear to be at least as potent risk factors for CHD as depression (18,19), and it appears that a combination of these negative factors confers cumulative risk (20).

A growing body of research has examined whether psychological well-being might lead to reduced risk of CVD. In 2012, a comprehensive review focusing on the most rigorous evidence available (i.e., prospective designs, adjustment for psychological distress, objective measures of CVD), found that several facets of psychological well-being were consistently associated with reduced risk of incident CVD (1). Generally, evidence was strongest for optimism, (e.g., 2,21) although that may be in part because more long-running cohort studies have measured optimism whereas fewer epidemiologic cohorts measure other facets of psychological well-being. Prospective evidence available since 2012 is highly congruent with these findings. Five prospective studies evaluating the relation between optimism and CVD have generally found results in the expected direction. For example, in a prospective study of 70,021 older women followed over 8 years, women in the highest versus lowest quartile of optimism had a 38% reduced risk (95% CI: 0.50–0.76) of heart disease mortality and a 39% reduced risk (95% CI: 0.43–0.85) of stroke mortality after adjustment for sociodemographic factors (22). Several other cohorts have reported similar findings when considering CVD mortality as well as incident heart failure (2,21,23).

Since 2012, additional studies have evaluated purpose in life (24–26), with 5 of these included in a recent meta-analysis (10 studies, pooled n = 124,948; mean age 57–72 years; mean follow-up duration 7.3 years). Across studies, the relative risk for cardiovascular events was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.75–0.92) in models that adjusted for a broad range of potential confounders (25). In another study conducted since then, 453 elderly adults (mean age 84 years) were followed over 6 years and upon death, autopsied, and diagnosed by neurologists. Higher life purpose was associated with lower odds of macroscopic infarcts (OR: 0.54, 95%CI: 0.35–0.83), but not microinfarcts (27). Findings have been evident albeit not fully consistent when considering other facets of psychological well-being (e.g., positive affect; 24). Earlier studies identified a protective effect of positive affect on CVD risk, but recent large studies have showed null results (26). However, as noted elsewhere, a somewhat weak measure of the exposure and possible statistical over-adjustment may render these studies somewhat less convincing (28). That said, it is also plausible that not all facets of psychological well-being predict CVD-related outcomes equally strongly.

Key Questions

Although this brief review suggests that psychological well-being is associated with CVH and CVD, outstanding questions remain. In the rest of this paper, we address key questions regarding the mechanisms underlying these associations, the social environmental influences on psychological well-being, and the effectiveness of interventions to strengthen psychological well-being. In addition, we provide guidance for healthcare providers in application of psychological well-being interventions in CVH promotion and, finally, discuss directions for future research.

Mechanisms and Social Environmental Influences

Effects of Psychological Well-Being: Biological, Behavioral and Psychosocial Pathways

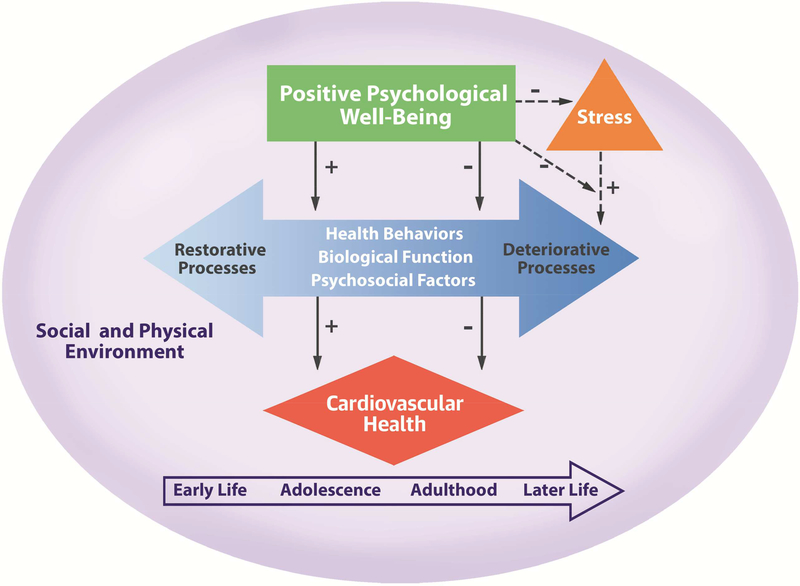

Psychological well-being may influence CVH across the lifespan via three plausible pathways: 1) direct effects on neurobiological processes, 2) indirect effects through health behaviors, and 3) promotion of other psychosocial resources known to protect health or buffer cardiotoxic effects of stressful experiences. For each pathway, effects of psychological well-being may reduce the likelihood of deteriorative processes (e.g., cigarette smoking, inflammation) and/or increase the likelihood of restorative processes (e.g., optimal sleep). The Central Illustration presents a model illustrating these links between psychological well-being and CVH, adapted from previous work (1).

Central Illustration. Model of the Relation Between Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Health.

This model illustrates the complex direct and indirect relationships linking positive psychological well-being with better CVH via health behaviors, biological function, and psychosocial factors. psychological well-being may also reduce likelihood of experiencing stress or buffer the health-related impact of stress. These relationships are conditional on the social and physical environment and may vary in their nature and implications across the life course. (+ represents direct, positive relationships; - represents indirect, negative relationships.)

Here, we briefly summarize findings on psychological well-being’s relationship with each of these pathways, emphasizing health and behavior factors relevant to CVH with a focus on studies conducted in healthy populations. While most studies published to date are crosssectional, some studies using more rigorous methods (i.e., experimental or longitudinal study designs, adjustment for relevant covariates including psychological distress, use of validated measures of exposure and outcomes) have been conducted, and we emphasize findings from these studies.

Biological Pathways

Research has linked various components of psychological well-being with biological processes posited to underlie the observed associations with CVH metrics (blood pressure, lipids, and glucose) and other cardiovascular conditions (e.g., atherosclerosis). The primary hypothesis is whether psychological well-being may lead to specific biological alterations that mediate effects on CVH. While many studies are cross-sectional, one advantage of these studies is that biological parameters are generally objectively measured, reducing concerns about self-report bias.

Previous reviews of the literature examining associations between psychological wellbeing and blood pressure have reported mixed findings, although longitudinal studies generally suggest that psychological well-being is prospectively associated with lower blood pressure across sex, race/ethnicity, and age (29). For example, in a large prospective study of 6,384 healthy British adults, greater emotional vitality was associated with 11% lower risk of developing hypertension over an average 11.8 years of follow-up, after adjusting for numerous potential confounders, including psychological distress (30). Heart rate variability has also been posited as a potential mechanism. Several studies have found higher psychological distress to be associated with reduced heart rate variability, generally indicating greater sympathetic activation and lower parasympathetic tone (31). In contrast, studies considering psychological well-being in relation to heart rate variability have found less consistent associations (32,33). Given the suggestive findings with distress, however, additional research considering whether psychological well-being might induce healthier parasympathetic tone and higher heart rate variability is warranted.

A review of findings with lipids reported mixed results (1), but rigorous studies have found higher psychological well-being is associated with more favorable lipid levels (34). It appears that these associations may vary depending on sex and race, as well as cultural differences (35,36). While cross-sectional studies have reported largely null associations of psychological well-being with blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c; 1,35), at least one longitudinal study found positive affect was associated with lower HbA1c over 2 years of follow-up (37). Investigators have also found consistent inverse associations between higher psychological well-being and metabolic syndrome prevalence (e.g., 38). Overall, this research suggests higher psychological well-being is associated with lower risk of metabolic dysfunction. Immune and inflammatory processes have received limited attention, with inconsistent but sometimes suggestive findings (34–38).

Behavioral Pathways

Psychological well-being has been studied in relation to each of the 4 CVH behaviorrelated factors defined by AHA: smoking, physical activity, diet, and BMI. Most studies are cross-sectional and rely on self-report of both psychological well-being and behaviors (aside from BMI), raising the possibility of self-report bias in estimates of association.

Numerous studies document a cross-sectional association between greater psychological well-being and lower likelihood of smoking (39,40). Some but not all longitudinal studies have documented associations in the expected directions (41). For example, young adolescents with lower levels of optimism and hope at baseline were more likely to be current smokers 7–10 months later, adjusting for sociodemographics and baseline smoking status (42); among patients who experienced acute coronary syndrome (ACS), the most versus least optimistic patients were less likely to be smoking cigarettes 12 months later (43).

Numerous studies have also found that high levels of psychological well-being are associated with greater likelihood of regular exercise (39). Although the association is likely bidirectional, accumulating prospective longitudinal evidence indicates that psychological wellbeing predicts greater likelihood of engaging in recommended levels of activity (e.g., 44). For example, in a sample of nearly 10,000 older adults from England, those with the highest wellbeing levels at baseline showed the most physical activity across 11 years of follow-up, adjusting for baseline health status and depression (45). Some null findings have also been reported (41).

Cross-sectional and prospective studies indicate that people with higher psychological well-being levels tend to consume more fruits and vegetables and fewer sweets and processed meats (39,40). For example, in analyses adjusting for age, sex, and baseline health, Finnish adults who were initially more versus less optimistic ate healthier diets at a 6-year follow-up (41). As with physical activity, there may be a bi-directional relationship such that healthier dietary patterns also promote psychological well-being. Findings are more equivocal for a healthy BMI, with protective associations suggested by cross-sectional studies but inconsistent results from prospective studies (e.g., 40,41).

Psychosocial Pathways and Stress Buffering

Various psychosocial mechanisms are posited to mediate the association between psychological well-being and CVH. For example, social support may link optimism with CVH because optimistic individuals are more likely to seek social support when facing difficult situations, be more well-liked, have larger networks of friends, and have friends who provide greater support during stressful times (46,47). Further, optimism provides confidence about the future, fostering other psychological and cognitive mechanisms that enhance CVH such as acting on medical advice more readily, engaging in effective problem solving, and taking action to prevent bad events (48). Some investigators have posited that “unrealistic optimism” may be detrimental, but most research suggests that those with high but not extreme optimism can distinguish between controllable versus uncontrollable stressors. Optimists tend to persevere and cope by using problem-solving and planning strategies to manage controllable stressors, but when faced with uncontrollable stressors, they shift to other goals and use other coping mechanisms (49). Similar mechanisms likely exist for other facets of psychological well-being.

Capacity to self-regulate may also be a mechanism by which psychological well-being influences health outcomes (50). Self-regulation involves appropriate cognitive, affective, and/or behavioral responses during daily life and in the context of one’s larger goals; these capacities provide the means to confront and adapt effectively to life’s challenges (51). Using more adaptive strategies for emotion regulation (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) versus maladaptive strategies (e.g., suppressing emotion expression) are associated with lower inflammation and more favorable CVH (50).

Having high levels of psychological well-being may also help buffer against harmful effects of stress. For example, optimism can alter processing and interpretation of daily stressors so they are experienced as less threatening (48). Evidence from both experimental and observational studies supports this hypothesis. For example, greater psychological well-being appears to mitigate such forms of stress as recalling experiences of sadness and anger (52) and stressors stemming from lower socioeconomic status (53).

Social Environmental Influences

Significant opportunities for improving cardiovascular outcomes in the U.S. may come from addressing social determinants (54), defined by the World Health Organization as the circumstances in which people live across the lifespan and the systems available to deal with illness (55). A recent AHA scientific statement described social factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, social relationships, childhood adversity) known to influence CVD, as well as possible psychological mechanisms such as emotional distress and psychiatric disorders (54,56). The statement did not, however, discuss the potential benefits of psychological well-being related to social factors and cardiovascular outcomes. While many facets of psychological well-being are considered partly heritable—with dispositional optimism, life satisfaction, and purpose in life showing 25% to 47% heritability (familial as well as genetic; 57)—the social environment can substantially influence the development and distribution of psychological well-being (58). A systematic social epidemiologic approach to psychological well-being—identifying its distributions in the population and its key determinants—is needed. Both developmental and social structural factors merit consideration.

Early life environment is important to the development of psychological functioning. Early life adversity, including exposure to adverse parental attributes (e.g., poor mental health), low socioeconomic position, and adverse family structure (e.g., single parenthood, parental alcoholism) predicts poor psychological health in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (e.g., 59,60). Lack of safe or nurturing relationships in childhood can affect structural and functional development of the brain in ways that increase likelihood of developing maladaptive habits and less supportive relationships (61). Fewer studies have considered how early social environments can establish trajectories of psychological well-being, though some important factors have been identified including parenting practices (warmth, being nurturing), ease of communication with parents, as well as liking school and having other supportive relationships (62–64). Other external factors that promote psychological well-being in youth include positive and high quality peer relationships and strong social networks (65), perceiving school as a supportive environment, and living in neighborhoods with high social capital (66–68).

With regard to structural factors, the World Happiness Report documents ecological findings linking greater psychological well-being with numerous macro-level factors, including higher country-specific GDP per capita, freedom to make life choices, absence of corruption, and lower income inequality (69). Studies have further demonstrated that life satisfaction is associated with higher income, education, and occupational status (70,71) although few studies have examined associations of social structural factors with psychological well-being facets beyond life satisfaction and positive affect. In the U.S., race and ethnicity may also play a role, given greater life satisfaction reported by Whites than by Blacks and Hispanics. However, some studies have also noted that associations of structural factors with psychological well-being are not always independent, and may be synergistic (70). Evidence points to other social indicators that may influence psychological well-being, including greater social support, increased network size (72–74), financial crises (75), community social capital (76), social mobility (77), and neighborhood disorder (78).

Preventive Action at Personal, Community, and Societal Levels

Given the data linking psychological well-being with CVH metrics and clinical endpoints, a key next step is to assess whether specific interventions at individual, community, and societal levels can successfully modify psychological well-being, and whether cultivating well-being leads, in turn, to better CVH. While it may be the case that some aspects of psychological well-being are heritable and/or relatively fixed, other facets of l well-being have been identified as life skills, part of a set of malleable personal characteristics and capabilities that increase chances of success and well-being in life (79). Psychological well-being-based interventions to build skills and promote health could be applied at four phases throughout the life course: promoting healthy gestation/development/aging; achieving favorable change in CVH components; enhancing effective acute and long-term management following clinical cardiovascular events; and supporting palliative/end-of-life care (3).

Individual and Small-Group Interventions

First, psychological well-being may be strengthened via interventions designed for individuals or small groups. Such programs include mindfulness-based programs and positive psychological interventions that directly target optimism, positive affect, and related constructs. Thus far, the majority of studies have examined mindfulness-based interventions. Mindfulness is an approach that involves attending to present-moment experiences with openness, nonjudgment, and curiosity. Here mindfulness is conceptualized as a tool to increase psychological well-being, rather than as a component of psychological well-being itself. A variety of mindfulness-based interventions have been developed, including mindfulness-based stress reduction (80) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (81). Related mind-body techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation, deep-breathing exercises, guided imagery, yoga, and tai chi, have also been used to promote psychological well-being.

Among generally healthy persons without existing heart disease, mindfulness-based interventions are associated with improvements across a range of physical and mental health outcomes including improved depressive symptoms, anxiety, stress, quality of life, physical functioning, smoking cessation, healthy eating, and physical activity (82–84). Among persons with cardiac risk factors, mindfulness training has been associated with weight loss (85), disease self-management and glucose control (86,87), and improved problem-focused coping and blood pressure (88).

Mindfulness-related interventions in patients with existing heart disease have led to benefits in physical and mental health-related quality of life, depression, anxiety, physical activity, and blood pressure (89,90). Overall, a meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in 578 patients with vascular disease (including heart disease) from 8 randomized controlled trials found that, compared to control conditions, the interventions were associated with small to medium effects on stress (standardized mean difference [SMD] −0.36 [95% CI −0.67, −0.09]; p=0.01), depressive symptoms (SMD −0.35 [−0.53, −0.16]; p=0.003) and anxiety (SMD −0.50 [−0.70, −0.29]; p<.001; 91), mostly at 8-week follow-up. Tai chi and yoga have led to improved outcomes in heart failure patients (92–94) and blood pressure and exercise capacity improvements in other CVDrelated populations (95). Meditation is a component of many mindfulness-based interventions, and has been associated with mortality reduction in individuals with hypertension (96). A recent AHA scientific statement (97) recommended meditation as an adjunct to other cardiovascular risk reduction methods given promising evidence of benefit and low cost and risk. Overall, mindfulness-based interventions appear to promote psychological well-being and support CVH, though not all studies have found benefit and study quality remains inconsistent (82,91).

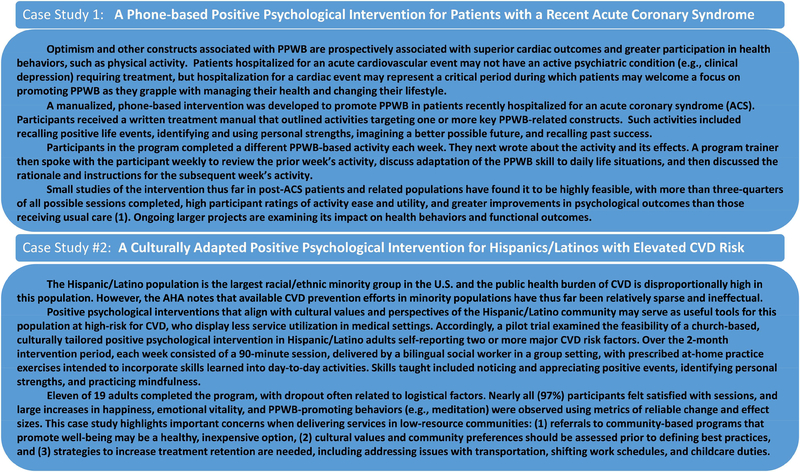

In contrast to mindfulness interventions, positive psychology interventions aim to promote optimism, gratitude, and positive affect directly through activities such as imagining and writing about a better future, recalling positive life events, identifying and using personal strengths, and planning and performing acts of kindness (98,99). Positive psychological interventions can be straightforward to deliver, are often feasible and well-accepted by patients, and may not require extensive provider training. Many programs have participants complete well-being activities on their own, followed by feedback and support from a program clinician/trainer (Figure 1). In healthy individuals, such activities have been found to improve indicators of psychological well-being such as optimism (100,101) in the short term, with some suggestion of sustained effect. Overall, a meta-analysis of 6139 participants in 39 randomized trials found that positive psychological interventions were associated with significant, small effects on well-being (SMD .34; p <0.001) and depression (SMD 0.23; p <0.001), with effects sustained at 3- or 6-month follow-up (101).

Figure 1: Case Studies of Positive Psychological Well-Being Interventions.

These two case studies illustrate application of psychological well-being interventions in clinical and community/organizational settings, respectively. While these are small in scale, they typify intervention approaches being explored in this arena. (ACS, acute coronary syndrome; AHA, American Heart Association; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CVH, cardiovascular health.)

Less research exists for positive psychology interventions in patients with CVD or cardiac risk factors. Positive psychological interventions in at-risk populations (e.g., patients with hypertension or diabetes) have led to improvement in psychological well-being (102–104) and often, but not always, improvements in medication adherence (102–105) or other self-care behaviors (106). For example, in a randomized trial among patients with type 2 diabetes, a positive affect intervention led to greater improvements in depression (β = −0.21; p =0.05) compared to the control conditon (103). Among patients with existing CVD, positive psychology interventions, including programs specifically targeting optimism (107), have consistently led to greater improvements in psychological well-being and functional performance than comparison conditions (107–109), with one large trial also finding improvements in physical activity (109). For example, a positive psychological intervention was associated with medium effect size differences in depression, anxiety, and positive affect improvement (SMD = 0.47–0.71) compared to treatment as usual among patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome (108). Additional large studies are required to examine effects on behavioral and health outcomes. Beneficial effects of positive psychological interventions in CVD populations have also been reported for biological markers, including inflammation and heart rate variability (110,111), though these biological effects have been less consistently observed than effects on health behaviors.

Finally, programs specifically focused on increasing meaning and purpose have also been developed and tested. Large randomized trials among those with advanced cancer or in palliative care have found that meaning- and purpose-related interventions have led to improvements in well-being, quality of life, depression, and physical symptom distress, with increased sense of meaning in life found to mediate these effects (112,113). A meaning-focused intervention study in palliative care found strong effects on purpose (r = 0.56; p <0.001) and depressive symptoms (p <0.05; 113). To our knowledge such interventions have not been tested in individuals with, or at risk for, CVD.

Along with their utility as stand-alone interventions, programs that cultivate psychological well-being could be combined with existing programs that target health behavior change (114). Mindfulness-based interventions have been integrated successfully into cardiac rehabilitation programs (115). In addition, positive psychological activities have led to increases in self-efficacy, confidence, and interpersonal connectedness (114), which in turn are linked with greater engagement in traditional health behavior interventions (116,117). This suggests that a combined psychological well-being-health behavior intervention could provide cardiac benefit both directly via improving psychological factors linked to cardiac outcomes (e.g., depression) and by boosting engagement with a linked behavioral intervention such as motivational interviewing (114). Indeed, a recent factorial design trial found that adding motivational interviewing to a positive psychological intervention led to greater health behavior adherence compared to those receiving the positive psychology intervention alone (118).

Community- and Population-Level Interventions

Promoting psychological well-being in community-based contexts—whether through workplaces, churches, neighborhoods, or population-wide—could provide even greater benefits. Prior trials have tested programs to enhance psychological well-being for adolescents in school settings (119,120) and older adults through community agencies (121). These interventions have resulted in fewer depressive symptoms and physical complaints, improvements in quality of life and emotional well-being, and personal growth (120,121). A church-based positive psychological group intervention (Figure 1) in U.S. Hispanics/Latinos at risk for CVD found the program to be feasible and associated with pre-post increases in emotional well-being and greater engagement in happiness-inducing behaviors (e.g., meditation; 122).

Perhaps the richest development of such institutional programs has been in the workplace. Such programs are of particular interest given that the overwhelming majority of U.S. adults are employed in a workplace setting, and many experience work as a significant source of stress (122). Moreover, routine job-related stress, including job strain and long working hours, may contribute to elevated risk for CVD (123). Recent AHA publications have focused on the workplace, including a Workplace Health Playbook on resilience-training programs (124). These resilience programs have been performed by individuals or groups of employees and use a mix of traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), mindfulness, promotion of ‘psychological capital,’ and programs rooted in positive psychology (125,126). They have demonstrated small but significant effects on work performance, psychological outcomes, and physical health. Other psychological well-being-focused programs related to ‘positive organizational health,’ have been less well-studied empirically (127) than traditional CBT-based stress management programs, and thus more research is needed to understand the impact of such workplace programs.

Though psychological well-being programs have not yet been applied to whole communities, there is an increasing focus on CVH promotion interventions tailored to specific communities (128). Examples include the city-wide Healthy Chicago/Healthy Hearts Action Plan and Be There San Diego, a project to make San Diego County CVD- and stroke-free. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Culture of Health initiative (129) supports roughly 30 U.S. communities nationwide by “making health a shared value, fostering cross-sector collaboration to improve well-being, creating healthier, more equitable communities, and strengthening integration of health services and systems.” The potential contribution of psychological wellbeing interventions to these and similar initiatives should be investigated with high priority.

Caregivers in Health Promotion: Implications for Clinical Practice

Clinical Practice

Clinical cardiology encounters can provide an excellent opportunity to assess and promote psychological well-being, especially as it relates to health. A first step during the visit may be a brief assessment for symptoms of psychological distress, such as depression and anxiety. Prior state-of the-art reviews on psychological distress and CVD (130,131) have outlined an approach to such screening and potential next steps in clinical management of mental health conditions.

Next, assessment of psychological well-being is warranted. While long-term survivors of acute CVD events often do not present clinically with a current psychiatric condition nor are they typically actively distressed, the majority of patients in the short-term aftermath of the event are likely to find that promotion of psychological well-being is relevant to their quality of life and function. When reviewing results of depression/anxiety screening with patients, clinicians can briefly introduce the idea that psychological well-being, not just the absence of acute distress, is important to health. Several specific questions (Table 1) about psychological well-being may be informative and can stimulate conversation about promotion of psychological well-being. These questions can focus on a patient’s optimism, life satisfaction, social support, life purpose, and positive affect, both in relation to their overall life circumstances and their health.

Table 1.

Brief clinician questions and statements to address and promote positive psychological well-being in clinical encounters.

| Optimism |

|

Questions: • “Do you expect that good things will happen for you in the future?” • “How do you think things will go with your health in the future?” Sample statements to support positive psychological well-being: |

| I have managed many patients with this health problem before and I have seen many of them do very well. I think you can too. |

| Positive affect/life satisfaction |

|

Questions: • “How often do you experience pleasure or happiness in your life?” • “Are you satisfied with how your life has gone and how you have lived it?” |

| Sample statements to support positive psychological well-being: |

| There is a lot of research finding connections between feeling happy and satisfied with your life, and your heart health. So I want to really support you in taking time for yourself and engaging in [healthy hobbies or meaningful activities]. |

| Gratitude |

|

Questions: • “What, if anything, do you have to feel grateful for in your life?” • “Do you ever feel grateful about your health? Tell me about that.” |

| Sample statements to support positive psychological well-being: |

| We were lucky to catch this problem when we did, and I think that means that there is a good chance that your health can remain strong if we work together. |

| Leveraging Personal Strengths |

|

Questions: • “What are your greatest strengths and skills?” • “When have you applied your best skills to improving your health?” |

| Sample statements to support positive psychological well-being: |

| I have been so impressed with how you have succeeded in your life when [life situation]. You can use those same skills to be successful in taking care of your heart health. |

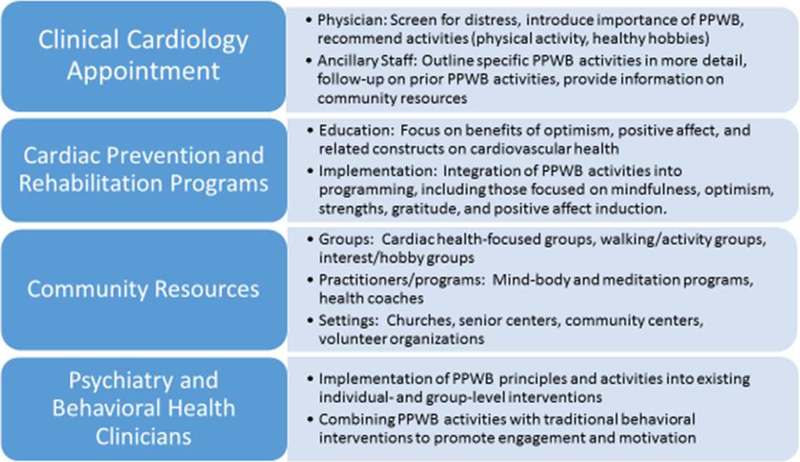

Psychological well-being can then be promoted and supported in a variety of ways by clinicians and co-providers (Figure 2). Such an approach focuses on bolstering a person’s strengths to promote their psychological well-being and health, an approach that patients may find engaging and rewarding. Specific statements from clinicians can support psychological well-being, especially when statements relate to patients’ personal circumstances (Table 1). Next, clinicians can make tailored recommendations (Tables 1 and 2). For example, a clinician may “give permission” for patients to engage in valued hobbies or other enjoyable activities, especially those that involve physical activity, social support, or deeper life satisfaction and purpose. Such clinician “prescriptions” to tend to one’s well-being can be powerful and highly valued by patients, and such prescriptions may hold further weight when clinicians share that psychological well-being is associated with better health-related quality of life and superior cardiovascular outcomes.

Figure 2: Principles and Methods of Positive Psychological Interventions.

These principles are illustrated in two types of settings. Together they may aid the clinician and co-providers to identify previously unrecognized opportunities for improving CVH through approaches unique to each setting. (CVH, cardiovascular health)

Table 2.

Activities to promote positive psychological well-being in clinical encounters and beyond.

| Characteristic/Asset | Introductory activity in clinical encounter | Structured activities | Skill to be developed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimism | Considering and discussing a better possible health-related future | Writing in detail about a best possible health-related future one year from now and how this could be realized | Developing optimistic health expectations and goal-focused accomplishment of these expectations |

| Gratitude | Discussing reasons to be grateful related to one’s current health status | Initiating a practice of recalling or journaling positive life events Writing a letter of gratitude to another person |

Cultivating a grateful world-view, including gratitude for health. |

|

Self- fficacy/confidence and use of personal strengths |

Considering one’s prior successes, the characteristics that led to such successes, and how this might apply to health goals | Writing about a major past life success, and writing about how the skills that led to this success will apply to self-care Identifying a personal signature strength (e.g., perseverance, social intelligence, creativity) and using this strength in a new way |

Developing a strengths-focused identity, and cultivating use of personal strength(s) for health-related activities |

| Positive affect | Discussing past positive life events and valued current activities that bring pleasure | Scheduling pleasurable activities Capitalizing on positive life events by savoring or sharing them |

Creating a practice of experiencing and savoring positive life events |

| Meaning/purpose | Discussing the things in one’s life that provide a sense of purpose | Writing about one’s legacy, steps to reach those life goals, and how health related activities can facilitate such goals | Identifying specific, meaningful life goals and utilizing health-related self-care to facilitate reaching such goals |

For patients with adequate insight and interest, clinicians can additionally recommend specific structured psychological well-being-related activities. Sample activities, summarized in Table 2, may include optimism-focused or health-related activities linked to better well-being (132). Clinicians or co-providers can also provide information about community programs and resources that promote psychological well-being and/or increase social support, including social networks and home care. This approach may be particularly important in low-income areas or underserved communities given potential barriers to traditional psychological and behavioral strategies related to cost, stigma, and environmental resources. While it may seem challenging to help patients modify psychological well-being in the context of a new medical diagnosis, these events can represent a “teachable moment”.

It is well understood that most physicians have had minimal training in this area and have highly limited time with patients. However, a structured and brief approach to psychological well-being that involves a small number of targeted - questions, a patient-centered discussion of sources of psychological well-being and specific activities to promote well-being, information about the benefits of psychological well-being, and provision of specific resources, may be a brief and meaningful component of a patient’s appointment and overall care. More in-depth discussions, follow-up on positive activities, and additional resources may be provided by other members of the clinical team (e.g., nurses, office staff, or behavioral health colleagues). Furthermore, settings focused on cardiovascular wellness, such as cardiac prevention and rehabilitation programs, may provide ideal opportunities for conducting these assessments, conversations, and interventions. Finally, psychiatrists, psychologists, and other clinicians with behavioral cardiology expertise may be able to utilize well-being approaches, and can combine or integrate them with other psychological or behavioral interventions (Figure 2).

Future Research Directions

Further research is needed at three distinct but complementary levels. First, better definition and measurement of psychological well-being will enhance the field. A small number of well-validated measures are established for specific aspects of well-being (133). However, for most facets of well-being (e.g., purpose, positive affect) strong instruments are lacking or there is no consensus choice of measure. Additional work is needed to gain consensus around optimal existing measures and to develop psychometrically sound instruments when they are lacking.

Second, because insight into mechanisms is fundamental to establishing causality and can guide intervention development (see 134), the field requires more rigorous investigation of causal pathways linking psychological well-being with cardiovascular outcomes. Studies of mechanistic pathways linking psychological well-being with CVH behaviors, factors, and outcomes have often been cross-sectional, examined only a single psychological factor, and had several other key shortcomings. Future studies evaluating mechanistic pathways require robust observational epidemiologic studies that incorporate: (1) multiple measures of well-being to distinguish if distinct facets of psychological well-being differentially impact outcomes; (2) longitudinal study designs to assess prospective relationships; (3) concurrent examination of biological, behavioral, and psychosocial pathways; (4) adequate control for psychological distress (e.g., depression) and other confounders; (5) large, diverse samples; and (6) the use of optimal causal inference methods.

Regarding studies of biological pathways and psychological well-being, findings have often been only suggestive, due in part to methodological issues noted above. While prospective findings provide more compelling evidence, standard techniques for reducing concerns about reverse causality, like adjusting for baseline levels of the outcome of interest, may not always address this concern. Bidirectional associations are also likely, as with depression and CVD (135). Alternative methods for assessing causal inference—such as epidemiologic studies utilizing repeated measures, statistical methods specifically targeted at these issues (e.g., marginal structural models), or experimental designs—can help resolve these concerns. Further, because reliance on a single biological measure may not reflect biological status across multiple systems, newer “omics” approaches (e.g., metabolomics the microbiome) may add insight.

Studies of psychological well-being and health behaviors have more often been longitudinal, and associations found more consistently, especially for physical activity and smoking, although a diversity of study populations has contributed to some mixed findings. Obtaining repeated measures of objectively measured health behaviors over time will result in a more comprehensive and rigorous body of evidence to indicate which health behaviors link psychological well-being with CVH. Psychosocial pathways also represent an important mechanism, as they can promote effective problem solving, capacity to regulate, and stress buffering; however, few studies have specifically tested these pathways as potential mediators. Direct evidence will require well-designed studies that assess psychological well-being, a range of psychosocial factors, and CVH.

Regarding social environmental antecedents, macro-level factors like socioeconomic position and social relationships correlate with psychological well-being, though most studies have been ecological and correlational. Individual-level prospective studies of socioeconomic position or changes in social networks have shown predictive relationships with psychological well-being; however, such relationships are not uniform across well-being constructs (77).

Further studies evaluating social environmental influences on psychological well-being, especially those measuring multiple psychological well-being constructs, are needed.

Third, study of interventions that promote psychological well-being must be a key focus of the clinical and research agenda. Though mindfulness-based and positive psychological interventions appear effective in improving psychological well-being among healthy persons, their impact on promoting CVH and improving outcomes for CVD patients remain seriously understudied. Contemporary individual-, group-, and community-level well-being interventions should be based in theoretical models, target modifiable attributes linked with CVH, and be studied via rigorous, well-powered pragmatic trials in patient samples and healthy populations. Intervention studies should also consider mobile health interventions to improve reach and impact of a combined psychological well-being-health behavior intervention, which may be more powerful than either intervention alone. Interventions based in churches, workplaces, and other community settings, could promote greater community-wide well-being and social support, and strengthen individual-level psychological assets. Investigators have noted that some countries more actively promote resources that enhance psychological well-being, including social support and generosity and universal provision of physical and mental healthcare, and speculate these resources may explain the superior life expectancies and overall health seen in these countries. However, no studies have assessed population-level well-being interventions to promote CVH.

Conclusions

A substantial body of research addresses psychological well-being’s relationship with CVH. Psychological well-being may affect CVH through three broadly defined pathways— biological, behavioral, and psychosocial. Psychological well-being can be strengthened by interventions such as mindfulness-based programs and positive psychological interventions. Such interventions, applied in clinical practice for both individuals and small groups, have generally been found to improve mental health outcomes and quality of life—worthy outcomes in their own right; however, whether such interventions durably and powerfully change CVH behaviors, biological factors, or cardiac outcomes remains an open question. Community-level interventions in workplaces, schools, churches, and other organizations have received limited evaluation to date. Moreover, no studies have specifically tested whether psychological wellbeing interventions lead to improvements in CVH per se (110). However, the field is increasingly headed in this direction, with studies aiming to identify optimal components of psychological well-being that can be subsequently tested in rigorous controlled trials examining effects on health-related outcomes (118). With wider experience and further evidence, clinical practice recommendations and health policy guidelines for psychological well-being interventions could substantially impact population-level CVH. Investment in the proposed research is urgently needed to realize this potential contribution of improved psychological health to better population CVH—an issue that can no longer wait.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Rosalba Hernandez is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) through award number 1K01HL130712–01. Jeff Huffman is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant R21DK109313) and the American Diabetes Association (grant 1–17-ICTS-099). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the American Diabetes Association.

Abbreviations:

- AHA

American Heart Association

- BMI

body mass index

- CBT

cognitive behavioral therapy

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- CVH

cardiovascular health

- HbA1c

Hemoglobin A1c

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

Footnotes

Disclosures: No relationships with industry

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD. The Heart’s Content: The Association Between Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Health. Psychol Bull 2012;138:655–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anthony EG, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett-Connor E. Optimism and Mortality in Older Men and Women: The Rancho Bernardo Study. J Aging Res 2016;2016:5185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Labarthe DR, Kubzansky LD, Boehm JK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Berry JD, Seligman ME. Positive Cardiovascular Health: A Timely Convergence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;68:860–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Younus A, Aneni EC, Spatz ES et al. A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Outcomes of Ideal Cardiovascular Health in US and Non-US Populations. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91:649–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waterman AS. O n the importance of distinguishing hedonia and eudaimonia when contemplating the hedonic treadmill. Am Psychol 2007;62:612–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002;82:1007–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryff CD, Love GD, Urry HL et al. Psychological well-being and ill-being: do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychother Psychosom 2006;75:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronish IM, Carson A, Davidson K, Muntner P, Stafford M. Depressive symptoms and cardiovascular health by the American Heart Association’s definition in the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differencesin Stroke (REGARDS) Study. PLoS One 2012;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehm JK, Soo J, Chen Y et al. Psychological Well-being’s Link with Cardiovascular Health in Older Adults. Am J Prev Med 2017;53:791–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernandez R, Kershaw KN, Siddique J et al. Optimism and Cardiovascular Health: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Health Behav Policy Rev 2015;2:62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression and coronary heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2017;14:145–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gan Y, Gong Y, Tong X et al. Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMC Psychiatry 2014;14:371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batelaan NM, Seldenrijk A, Bot M, van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW. Anxiety and new onset of cardiovascular disease: critical review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2016;208:223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:936–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edmondson D, Kronish IM, Shaffer JA, Falzon L, Burg MM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk for coronary heart disease: a meta-analytic review. Am Heart J 2013;166:80614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kivimaki M Psychosocial factors in etiology and prognosis of specific diseases and disorders: cardiovascular diseases In: Kivimaki M, Batty DG, Kawachi I, Steptoe A, editors. Handbook of Psychosocial Epidemiology. New York: Routledge, 2018:247–262. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kubzansky LD, Cole SR, Kawachi I, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Shared and unique contributions of anger, anxiety, and depression to coronary heart disease: A prospective study in the Normative Aging Study. Ann Behav Med 2006;31:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A 3rd, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steptoe A, Brydon L. Emotional triggering of cardiac events. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2009;33:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim ES, Smith J, Kubzansky LD. Prospective study of the association between dispositional optimism and incident heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2014;7:394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim ES, Hagan KA, Grodstein F, DeMeo DL, De Vivo I, Kubzansky LD. Optimism and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol 2017;185:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim ES, Park N, Peterson C. Dispositional optimism protects older adults from stroke: the Health and Retirement Study. Stroke 2011;42:2855–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambiase MJ, Kubzansky LD, Thurston RC. Positive psychological health and stroke risk: The benefits of emotional vitality. Health Psychol 2015;34:1043–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen R, Bavishi C, Rozanski A. Purpose in Life and Its Relationship to All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis. Psychosom Med 2016;78:122–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu B, Floud S, Pirie K et al. Does happiness itself directly affect mortality? The prospective UK Million Women Study. Lancet 2016;387:874–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu L, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Levine SR, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Purpose in life and cerebral infarcts in community-dwelling older people. Stroke 2015;46:1071–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kubzansky LD, Kim ES, Salinas J, Huffman JC, Kawachi I. Happiness, health, and mortality. Lancet 2016;388:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Gilsanz P, Mittleman MA, Kubzansky LD. Dysregulated Blood Pressure: Can Regulating Emotions Help? Curr Hypertens Rep 2015;17:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Boehm JK, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky LD. Taking the tension out of hypertension: a prospective study of psychological well-being and hypertension. J Hypertens 2014;32:1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK et al. Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001;104:2024–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oveis C, Cohen AB, Gruber J, Shiota MN, Haidt J, Keltner D. Resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia is associated with tonic positive emotionality. Emotion 2009;9:265–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sloan RP, Schwarz E, McKinley PS et al. Vagally-mediated heart rate variability and indices of well-being: Results of a nationally representative study. Health Psychol 2017;36:73–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richman LS, Kubzansky LD, Maselko J, Ackerson LK, Bauer M. The relationship between mental vitality and cardiovascular health. Psychol Health 2009;24:919–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oreskovic NM, Goodman E. Association of optimism with cardiometabolic risk in adolescents. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:407–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo J, Miyamoto Y, Rigotti A, Ryff CD. Linking Positive Affect to Blood Lipids: A Cultural Perspective. Psychol Sci 2017;28:1468–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsenkova VK, Dienberg Love G, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Coping and positive affect predict longitudinal change in glycosylated hemoglobin. Health Psychol 2008;27:S163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Midei AJ, Matthews KA. Positive attributes protect adolescents from risk for the metabolic syndrome. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:678–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grant N, Wardle J, Steptoe A. The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: a cross-cultural analysis of young adults. Int J Behav Med 2009;16:259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelloniemi H, Ek E, Laitinen J. Optimism, dietary habits, body mass index and smoking among young Finnish adults. Appetite 2005;45:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serlachius A, Pulkki-Raback L, Elovainio M et al. Is dispositional optimism or dispositional pessimism predictive of ideal cardiovascular health? The Young Finns Study. Psychol Health 2015:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carvajal SC, Wiatrek DE, Evans RI, Knee CR, Nash SG. Psychosocial determinants of the onset and escalation of smoking: cross-sectional and prospective findings in multiethnic middle school samples. J Adolesc Health 2000;27:255–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ronaldson A, Molloy GJ, Wikman A, Poole L, Kaski JC, Steptoe A. Optimism and recovery after acute coronary syndrome: a clinical cohort study. Psychosom Med 2015;77:311–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carvajal SC. Global positive expectancies in adolescence and health-related behaviours: longitudinal models of latent growth and cross-lagged effects. Psychol Health 2012;27:916–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim ES, Kubzansky LD, Soo J, Boehm JK. Maintaining Healthy Behavior: a Prospective Study of Psychological Well-Being and Physical Activity. Ann Behav Med 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brissette I, Scheier MF, Carver CS. The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002;82:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersson MA. Dispositional Optimism and the Emergence of Social Network Diversity. Sociol Q 2012;53:92–115. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rasmussen HN, Wrosch C, Scheier MF, Carver CS. Self-regulation processes and health: the importance of optimism and goal adjustment. J Pers 2006;74:1721–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Segerstrom SC. Optimism. Clin Psych Rev 2010;30:879–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Appleton A, Kubzansky LD. Emotion regulation and cardiovascular disease risk In: Gross JJ, editor Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: The Guildford Press, 2014:596–612. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Optimism, pessimism, and self-regulation In: Chang EC, editor Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2001:31–52. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brummett BH, Boyle SH, Kuhn CM, Siegler IC, Williams RB. Positive affect is associated with cardiovascular reactivity, norepinephrine level, and morning rise in salivary cortisol. Psychophysiology 2009;46:862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull 2003;129:10–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA et al. Social Determinants of Risk and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;132:873–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, Commission on Social Determinants of H. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet 2008;372:1661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Suglia SF, Koenen KC, Boynton-Jarrett R et al. Childhood and Adolescent Adversity and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diener E, Oishi S, Lucas RE. Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu Rev Psychol 2003;54:403–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kubzansky LD, Segerstrom SC, Boehm JK. Positive psychological functioning and the biology of health. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2015;9:645–660. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McLaughlin KA, Greif Green J, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Collins WA, Maccoby EE, Steinberg L, Hetherington EM, Bornstein MH. Contemporary research on parenting. The case for nature and nurture. Am Psychol 2000;55:218–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012;129:e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molcho M, Gabhainn SN, Kelleher CC. Interpersonal relationships as predictors of positive health among Irish youth: the more the merrier? Ir Med J 2007;100:suppl 33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levine K, Currie C. Family structure, mother–child communication, father–child communication, and adolescent life satisfaction : a cross-sectional multilevel analysis. Health Educ Res 2010;110:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A et al. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreno C, Sanchez-Queija I, Munoz-Tinoco V et al. Cross-national associations between parent and peer communication and psychological complaints. Int J Public Health 2009;54 Suppl 2:235–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Danielsen A, Samdal O, Hetland J, Wold B. School-Related Social Support and Students’ Perceived Life Satisfaction. J Educ Res 2009;102:303–318. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vieno A, Santinello M, Pastore M, Perkins DD. Social support, sense of community in school, and self-efficacy as resources during early adolescence: an integrative model. Am J Community Psychol 2007;39:177–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theokas C, Almerigi JB, Lerner RM et al. Conceptualizing and Modeling Individual and Ecological Asset Components of Thriving in Early Adolescence. J Early Adolesc 2005;25:113–143. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Helliwell J, Layard R, Sachs J. World Happiness Report. New York, 2017.

- 70.Barger SD, Donoho CJ, Wayment HA. The relative contributions of race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health, and social relationships to life satisfaction in the United States. Qual Life Res 2009;18:179–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fernández-Ballesteros R, Zamarrón MD, Ruíz MA. The contribution of sociodemographic and psychosocial factors to life satisfaction. Ageing Soc 2001;21:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greenfield EA, Reyes L. Continuity and Change in Relationships with Neighbors: Implications for Psychological Well-being in Middle and Later Life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2015;70:607–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tomini F, Tomini SM, Groot W. Understanding the value of social networks in life satisfaction of elderly people: a comparative study of 16 European countries using SHARE data. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging 2000;15:187224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clench-Aas J, Holte A. The financial crisis in Europe: Impact on satisfaction with life. Scand J Public Health 2017;45:30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Inaba Y, Wada Y, Ichida Y, Nishikawa M. Which part of community social capital is related to life satisfaction and self-rated health? A multilevel analysis based on a nationwide mail survey in Japan. Soc Sci Med 2015;142:169–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boehm JK, Chen Y, Williams DR, Ryff C, Kubzansky LD. Unequally distributed psychological assets: are there social disparities in optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect? PloS one 2015;10:e0118066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Toma A, Hamer M, Shankar A. Associations between neighborhood perceptions and mental well-being among older adults. Health Place 2015;34:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Life skills, wealth, health, and wellbeing in later life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017:201616011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kabat-Zinn J Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind in everyday life. New York: Delacorte; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Teasdale JD, Segal ZV, Williams JM, Ridgeway VA, Soulsby JM, Lau MA. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 2000;68:615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ruffault A, Czernichow S, Hagger MS et al. The effects of mindfulness training on weight-loss and health-related behaviours in adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract 2017;11:90–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gotink RA, Chu P, Busschbach JJ, Benson H, Fricchione GL, Hunink MG. Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. PLoS One 2015;10:e0124344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 84.Oikonomou MT, Arvanitis M, Sokolove RL. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: A meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. J Health Psychol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Olson KL, Emery CF. Mindfulness and weight loss: a systematic review. Psychosom Med 2015;77:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes selfmanagement through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Youngwanichsetha S, Phumdoung S, Ingkathawornwong T. The effects of mindfulness eating and yoga exercise on blood sugar levels of pregnant women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Appl Nurs Res 2014;27:227–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nejati S, Zahiroddin A, Afrookhteh G, Rahmani S, Hoveida S. Effect of Group Mindfulness-Based Stress-Reduction Program and Conscious Yoga on Lifestyle, Coping Strategies, and Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressures in Patients with Hypertension. J Tehran Heart Cent 2015;10:140–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Younge JO, Gotink RA, Baena CP, Roos-Hesselink JW, Hunink MM. Mind–body practices for patients with cardiac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:1385–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goodwin CL, Forman EM, Herbert JD, Butryn ML, Ledley GS. A pilot study examining the initial effectiveness of a brief acceptance-based behavior therapy for modifying diet and physical activity among cardiac patients. Behav Modif 2012;36:199–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Abbott RA, Whear R, Rodgers LR et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Psychosom Res 2014;76:341–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Howie-Esquivel J, Lee J, Collier G, Mehling W, Fleischmann K. Yoga in heart failure patients: a pilot study. J Card Fail 2010;16:742–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yeh GY, Chan CW, Wayne PM, Conboy L. The impact of tai chi exercise on self-efficacy, social support, and empowerment in heart failure: insights from a qualitative substudy from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2016;11:e0154678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yeh GY, McCarthy EP, Wayne PM et al. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:750–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yeh GY, Wang C, Wayne PM, Phillips R. Tai chi exercise for patients with cardiovascular conditions and risk factors: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2009;29:152–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barnes VA, Schneider RH, Alexander CN, Rainforth M, Staggers F, Salerno J. Impact of Transcendental Meditation on mortality in older African Americans with hypertension—eight-year follow-up. J Soc Behav Pers 2005;17:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Levine GN, Lange RA, Bairey-Merz CN et al. Meditation and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seligman M, Steen T, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol 2005;60:410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moskowitz JT, Carrico AW, Duncan LG et al. Randomized controlled trial of a positive affect intervention for people newly diagnosed with HIV. J Consult Clin Psychol 2017;85:409–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Malouff JM, Schutte NS. Can psychological interventions increase optimism? A meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol 2016:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, Bohlmeijer E. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC public health 2013;13:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DuBois CM, Millstein RA, Celano CM, Wexler DJ, Huffman JC. Feasibility and acceptability of a positive psychological intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2016; 18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cohn MA, Pietrucha ME, Saslow LR, Hult JR, Moskowitz JT. An online positive affect skills intervention reduces depression in adults with type 2 diabetes. J Posit Psychol 2014;9:523–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Boutin-Foster C, Offidani E, Kanna B et al. Results from the Trial Using Motivational Interviewing, Positive Affect, and Self-Affirmation in African Americans with Hypertension (TRIUMPH). Ethn Dis 2016;26:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kahler CW, Spillane NS, Day AM et al. Positive psychotherapy for smoking cessation: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:1385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Burrows B, Wilund K, Cohn MA, Xu S, Moskowitz JT, Hernandez R. Internetbased positive psychological intervention for hemodialysis patients with comorbid depression: design and feasibility. American Society of Nephrology. New Orleans, LA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mohammadi N, Aghayousefi A, Nikrahan GR et al. A randomized trial of an optimism training intervention in patients with heart disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2017;51:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Huffman JC, Millstein RA, Mastromauro CA et al. A positive psychology intervention for patients with an acute coronary syndrome: treatment development and proof-ofconcept trial. J Happiness Stud 2016;17:1985–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Peterson JC, Charlson ME, Hoffman Z et al. A randomized controlled trial of positive-affect induction to promote physical activity after percutaneous coronary intervention. Arch Int Med 2012;172:329–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Redwine LS, Henry BL, Pung MA et al. Pilot randomized study of a gratitude journaling intervention on heart rate variability and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with stage B heart failure. Psychosom Med 2016;78:667–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nikrahan GR, Laferton JA, Asgari K et al. Effects of positive psychology interventions on risk biomarkers in coronary patients: a randomized, wait-list controlled pilot trial. Psychosomatics 2016;57:359–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rosenfeld B, Cham H, Pessin H, Breitbart W. Why is Meaning-Centered Group Psychotherapy (MCGP) effective? Enhanced sense of meaning as the mechanism of change for advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology 2018;27:654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, Harlos M. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Millstein RA, Celano CM, Wexler D. Positive psychological interventions for patients with type 2 diabetes: rationale, theoretical model, and intervention development. J Diabetes Res 2015;2015:428349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Griffiths K, Camic PM, Hutton JM. Participant experiences of a mindfulnessbased cognitive therapy group for cardiac rehabilitation. J Health Psychol 2009;14:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Joseph CL, Havstad SL, Johnson D et al. Factors associated with nonresponse to a computer-tailored asthma management program for urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma 2010;47:667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Scheier MF, Helgeson VS, Schulz R et al. Moderators of interventions designed to enhance physical and psychological functioning among younger women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5710–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Celano CM, Albanese AM, Millstein RA et al. Optimizing a positive psychology intervention to promote health behaviors following an acute coronary syndrome: The Positive Emotions after Acute Coronary Events-III (PEACE-III) randomized factorial trial. Psychosom Med 2018;80(6):526–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Seligman ME, Ernst RM, Gillham J, Reivich K, Linkins M. Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Rev Educ. 2009;35:293–311. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ruini C, Ottolini F, Tomba E et al. School intervention for promoting psychological well-being in adolescence. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2009;40:522–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]