Abstract

Biofilm-associated infections stemming from medical devices are increasingly challenging to treat due to the spread of antibiotic resistance. In this study, we present a simple strategy that significantly enhances the antifouling performance of covalently crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) and physically crosslinked agar hydrogels by incorporation of the fouling-resistant polymer zwitterion, poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) (pMPC). Dopamine polymerization was initiated during swelling of the hydrogels, which provided dopamine and pMPC an osmotic driving force into the hydrogel interior. Both PEG and agar hydrogels were synthesized over a broad range of storage moduli (1.7,1300 kPa), which remained statistically equivalent after being functionalized with pMPC and polydopamine (PDA). When challenged with fibrinogen, a model blood-clotting protein, the pMPC/PDA-functionalized PEG and agar hydrogels displayed a >90% reduction in protein adsorption compared to hydrogel controls. Further, greater than an order-of-magnitude reduction in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus adherence was observed. This study demonstrates a versatile materials platform to enhance the fouling resistance of hydrogels through a pMPC/PDA incorporation strategy that is independent of the chemical composition and network structure of the original hydrogel.

Keywords: Antifouling, Dopamine, Hydrogel, Microorganism, Poly(ethylene glycol), Zwitterion

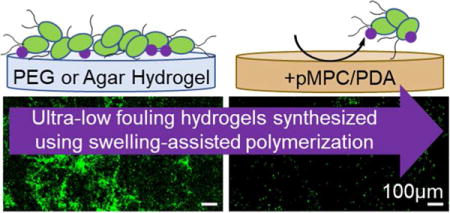

TOC image

INTRODUCTION

Indwelling medical devices are indispensable tools in modern healthcare. However, the insertion of any foreign object into the human body carries an inherent risk of infection.1–3 Over one-quarter of all healthcare-associated infections in the United States are attributed to central line-associated bloodstream infections and catheter-associated urinary tract infections.4–6 Hydrogel coatings are typically applied to catheters to improve patient comfort while also mitigating nonspecific protein adsorption and bacterial adhesion.7–9 The gold standard hydrophilic polymer used for antifouling coatings is poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG),10 since it hydrogen bonds with water to create a hydration layer that prevents non-specific protein adsorption.11,12 Surface hydration limits bacterial adherence to PEG coatings. Although surface chemistry is critical to controlling bacterial adhesion, the morphological and mechanical properties of a material will also influence bacterial surface interactions. Previously, we and others demonstrated that independent of hydrogel chemistry, softer hydrogels experience a slower bacterial colonization by Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).13–16 This work determined that the fouling resistance of PEG hydrogels can be improved further by harnessing fundamental structure-property relationships. However, given sufficient time, bacteria will colonize on low-fouling hydrophilic coatings, including PEG. To combat these microorganisms, commercial antibiotic treatments have been overused, which has accelerated the evolution of resistant genes in bacterial species.17,18 Thus, new materials that delay the initial attachment of proteins and microorganisms, while avoiding the spread of resistant genes, are in demand.

Polymer zwitterions have emerged as a promising class of antifouling polymers due to their enhanced stability and excellent fouling resistance.19,20 Carrying both positive and negative charges on each monomer subunit, polymer zwitterions induce a tight and stable surface hydration layer of “surface-bound” water that effectively resists protein adsorption.21,22 Although previously synthesized zwitterion-containing hydrogels effectively decreased biofouling, many exhibited poor mechanical strength.23–26 Thus, clay-nanocomposites,27 double-networks,28 functional crosslinkers,29 and pH-responsive monomers have been incorporated into zwitterion, containing hydrogels, which enhanced their mechanical strength by 2–3 times.30 However, these strategies require designer syntheses and limit their compatibility with existing hydrogels. The ability to integrate zwitterionic functionality into any hydrogel, irrespective of its chemistry or crosslinking structure, would extend the benefits of polymer zwitterions across the entire class of hydrogels.

Polydopamine offers an attractive universal approach to surface functionalization. Lee, et al. reported that under alkaline conditions, dopamine undergoes oxidative polymerization into an ultrathin surface-adherent polydopamine film on virtually any abiotic or biotic surface.31,32 Utilizing the functionality of polydopamine, the facile immobilization of molecules containing carboxyl, amine, thiol, quaternary ammonium, and/or catechol groups have been immobilized into functional coatings.33–37 Further studies have demonstrated the superior antifouling performance of similar coatings applied to a diverse array of solid materials including glass, silicon, steel, and polymer nanofibers.33,35,38 Although catechol crosslinkers, including dopamine, have been examined in numerous hydrogel formulations,39–41 the versatility of polydopamine containing coatings presents a potentially universal hydrogel modification strategy.

In this work, we demonstrate a simple and robust approach to enhance the antifouling performance of PEG and agar hydrogels that uses the polymerization of dopamine to immobilize the fouling-resistant polymer zwitterion, poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) (pMPC). By initiating dopamine polymerization while swelling the hydrogels, dopamine and pMPC are osmotically driven into the hydrogel interior and become immobilized. The incorporation of pMPC statistically improves the fouling resistance of PEG and transforms agar from a high-fouling to a fouling-resistant hydrogel. This simple technique represents a versatile approach to improve the antifouling performance of hydrogels, irrespective of their chemistry, network structure, and mechanical properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Chemicals

Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate, (PEG, MN = 750 Da), dopamine hydrochloride (dopamine), 3,(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate, ampicillin (BioReagent grade), chloramphenicol (BioReagent grade), M9 minimal salts (M9 media), D-(+)-glucose, calcium chloride (anhydrous), phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10× sterile biograde), tryptic soy broth (TSB), Luria-Bertani broth (LB), fibrinogen, and Bradford reagent were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Irgacure 2959 was obtained from BASF (Ludwigshafen, Germany). Anhydrous magnesium sulfate and molecular grade agar were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ). Deionized (DI) water was obtained from a Barnstead Nanopure Infinity water purification system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Fabrication of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

PEG hydrogels were prepared using previously established protocols.16 Briefly, 8.3 wt%, 28 wt%, and 55 wt% PEG dimethacrylate in 10 mM PBS (pH = 7.4) was filtered through a sterile 0.2 μm membrane, then degassed using nitrogen. For UV-curing, Irgacure 2959 (0.8 wt%) was added to the polymer precursor solution with induction under a longwave UV light (365 nm) for 10 min. The PEG solution (75 μL) was sandwiched between two 22-mm UV-sterilized coverslips (Fisher Scientific) functionalized with 3,(trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacylate.42 Fabricating the hydrogel between coverslips enabled all hydrogels to have a uniform thickness of ~150 μm and limited their oxygen exposure. Agar hydrogels were prepared by dissolving 1.0 wt%, 3.0 wt%, and 9.0 wt% agar in sterile DI water for 30 min before uniformly heating the solution in a liquid autoclave at 250°C for 30 min. The hot solution was cast into glass Petri dishes (Pyrex, Tewksbury, MA) and allowed to gel at a uniform height of 2 mm. After cooling, a flame-sterilized punch (Spearhead 130 Power Punch MAXiset, Cincinnati, Ohio) was used to create circular 25.4 mm diameter agar hydrogels.

pMPC was synthesized as previously described.34,43 The unmodified PEG and agar hydrogels were placed into 6-well polystyrene plates (Fisher Scientific) and immersed in 5 mL of Tris buffer (10 mM, pH 8.5) containing only dopamine (2 mg/mL) or solutions containing both dopamine (2 mg/mL) and pMPC (2 mg/mL) for 6 h. Under these basic conditions, dopamine undergoes oxidative self-polymerization to form polydopamine (PDA) when alone in solution or forms composites through non-covalent interaction when in the presence of pMPC.34 All hydrogels were removed from the reaction solution and washed 3 times with DI water before being placed in a new 6-well plate at 23°C with DI water until further testing. In the Results section, PEG and agar hydrogels are referred to as unmodified, PDA (if functionalized only with dopamine), or pMPC/PDA (if functionalized with dopamine and pMPC).

Characterization of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

The chemical compositions of unmodified, PDA, and pMPC/PDA PEG and agar hydrogels were determined using a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Waltham, MA). All spectra were recorded from 4000–500 cm−1 by accumulation of 32 scans and with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Scans were performed in duplicate on three replicates for each hydrogel. To monitor if the fabrication method had diffusion limitations, hydrogels were fabricated in cylindryical molds (2 mm thick and 22 mm in diameter) from 8.3 wt% and 55 wt% PEG, as well as from 1.0 wt% and 9.0 wt% agar. Following polymerization, hydrogels were swollen in 5 mL of Tris buffer containing 2 mg/mL dopamine. After 1 h, 6 h, and 24 h, the hydrogels were removed from solution and gently rinsed with DI water. The hydrogel’s top surface, bottom surface, and cross-section were photographed (Nikon D5200 camera with an AF-S NIKKOR 18–35mm 1:3.5–5.6G lens) and the red-green-blue (RGB) color values were quantified using Adobe Photoshop CC 2017.

Equilibrium swelling experiments were performed to determine the volumetric swelling ratio, Q, of control, PDA, and pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels. The control, free-standing PEG hydrogels were swollen in PBS for 24 h at 23°C until equilibrium swelling was achieved, then weighed to obtain their equilibrium swelling mass, MS. These hydrogels were lyophilized (Labconco, FreeZone Plus 2.5 Liter Cascade Console Freeze-Dry System, Kansas City, MO) for 72 h then weighed to determine their dry mass, MD. Q was calculated by dividing MS by MD. To quantify Q for PDA and pMPC/PDA hydrogels, the unmodified PEG hydrogels were weighed directly following polymerization to obtain the weight of the unmodified PEG hydrogel. Following the 6 h functionalization, hydrogels were washed 3 times with DI water and immersed in PBS for 48 h before being weighed to determine MS. Hydrogels were then lyophilized and weighed to determine MD. Four replicates were tested for each hydrogel.

Small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) measurements were acquired on the PEG and agar hydrogels using a plate–plate geometry with a diameter of 20 mm and a gap of 1 mm (Kinexus Pro rheometer, Malvern Instruments, UK). Prepared hydrogels (circular 25 mm diameter × 1 mm height) were loaded into the rheometer and trimmed to size using a razor blade. A strain amplitude sweep was performed to ensure that experiments were conducted within the linear viscoelastic region at a strain of 0.1%. Oscillation frequency sweeps were conducted over an angular frequency domain 1.0 and 100 rad/s at 23 °C.

The size of PDA aggregates on the surface of hydrogels was measured using an atomic force microscope (Cypher ES AFM, Asylum Research/Oxford Instruments, Santa Barbara CA) equipped with a PerFusion attachment for complete sample immersion. Topographic imaging was performed in DI water at room temperature (~23°C) using TR800PSA (k = 183.54 pN/nm) cantilevers (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Hydrogels were prepared on 15 mm glass coverslips and remained hydrated throughout the entire AFM preparation and testing process. Micrographs of hydrogels and hydrogel cross-sections were acquired using a Magellan 400 XHR scanning electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR). Cross-sections were obtained by flash-freezing the hydrogels using liquid nitrogen, then cracking the sample. Hydrogels were sputter coated for 60 s with platinum before SEM imaging (Cressington 208 HR, Cressington Scientific Instruments, Watford, U.K.).

Evaluation of Protein Adsorption and Bacterial Resistance of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

Protein adsorption was quantified using a fluorescent protein assay. Circular 15 mm diameter PEG and 12.7 mm diameter agar hydrogels were placed at the bottom of 24-well plates, to which 55 μL of fluorescently tagged fibrinogen (~2 tags per protein)44,45 in PBS (655 μg/mL) was added and agitated at 100 rpm for 48 h at 23°C. The hydrogels were surface rinsed 3 times with PBS, then the adsorption of fibrinogen was assessed using a Zeiss Microscope Axio Imager A2M (20× magnification, Thornwood, NY). Experiments were conducted in triplicate.

Bacterial adhesion was evaluated using the model Gram-negative strain Escherichia coli K12 MG1655 (E. coli, DSMZ, Leibniz-Institut, Germany) containing a GFP plasmid and the model Gram-positive strain Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 (S. aureus) containing the high-efficiency pCM29 sGFP plasmid.46 Circular 22 mm diameter control and pMPC/PDA PEG and agar hydrogels were placed at the base of 6-well polystyrene plates, to which 5 mL of M9 media with 100 μg/mL ampicillin, or 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol, were added for E. coli or S. aureus, respectively. The growth media in each well was inoculated with an overnight culture of 1.00 × 108 cells/mL (E. coli or S. aureus), which were washed and resuspended in M9 media,47 then placed in an incubator at 37°C for 24 h. Hydrogels with attached bacteria were removed from the 6-well polystyrene plates and rinsed lightly using PBS to remove loosely adhered bacteria. E. coli and S. aureus attachment was evaluated using a modified adhesion assay that monitored bacteria colony coverage (Zeiss Axio Imager, 20× magnification). The particle analysis function in ImageJ 1.48 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to calculate the bacteria colony area coverage over the acquired 58716 μm2 area.48,49 Significant differences between samples were determined using an unpaired student t-test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characteristics of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

Chemically and physically crosslinked hydrogels were successfully synthesized from PEG dimethacrylate (8.3 wt%, 28 wt%, and 55 wt%) and from agar (1.0 wt%, 3.0 wt%, and 9.0 wt%), respectively. Chemical functionalization of these hydrogels was achieved through a process we coined “swelling-assisted polymerization”. By immersing the hydrogels in Tris buffer, containing 2 mg/mL of dopamine and poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) (pMPC), the resulting concentration gradient induced an osmotic driving force into the hydrogel that facilitated pMPC/PDA formation throughout the polymer network.

The successful polymerization of dopamine to polydopamine (PDA) throughout the PEG and agar hydrogels was apparent due to their brown color, which is characteristic of the melanin-like structure of PDA, Figure 1. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Figure S1, acquired on the pMPC/PDA-functionalized PEG and agar hydrogels did not show pronounced peaks after functionalization, likely a result of the low concentration of the pMPC/PDA.34 Thus, to evaluate the diffusion of dopamine into the interior of the PEG (150 μm thick) and agar (1 mm thick) hydrogels, their color change was monitored as a function of time, Figure S2. Red-green-blue (RGB) color values at the surface and the center of the hydrogels were determined, where higher RGB values indicate darker colors corresponding to PDA formation. RGB analysis determined that PDA formation occurred rapidly (within 1 h) at the hydrogel surface. After a reaction time of 6 h, a uniform brown color was observed indicating the presence of PDA throughout the entire cross-section of all hydrogels, independent of their composition. Three methods of PDA incorporation into PEG and agar hydrogels are highlighted in the Supporting Information file and Figure S2; they were found to provide similar results after a reaction time of 6 h. Thus, while any of the three methods could be used, for the remainder of this study, dopamine polymerization was initiated following hydrogel formation but before swelling the hydrogels because this method was facile and provided samples with consistent physical appearance.

Figure 1.

Photographs of a PEG hydrogel before and after pMPC/PDA functionalization. Scales bars are 1 mm.

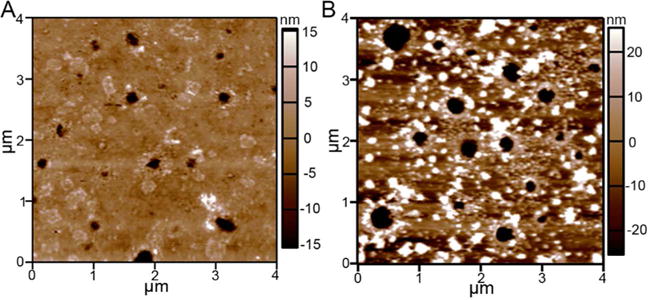

The PEG hydrogels were imaged using atomic force microscopy (AFM) in a hydrated enviroment after 6 h of swelling-assisted pMPC/PDA formation, Figure 2. Following pMPC/PDA formation and thorough rinsing in deionized water, the hydrogel surface was decorated with small PDA aggregates, characteristic of the mechanism of dopamine polymerization.50,51 PDA formation in the presence of pMPC has been reported to reduce the aggregate size.34 On the surface of the pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels, the aggregates ranged in size from 5 nm to 150 nm. The aggregates were also visible on the surface of dry hydrogels that were imaged using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, not shown). SEM micrographs acquired on the cross-section of PEG and agar hydrogels suggest that significantly fewer aggregates were present within the hydrogels than on their surface, Figure S3. In fact, no aggregates were observed within the agar hydrogels.

Figure 2.

AFM surface topography images of a hydrated (A) unmodified and (B) pMPC/PDA-modified PEG hydrogels. Representative micrographs were acquired on 55 wt% PEG hydrogels that were hydrated throughout the entire imaging process in DI water. A z-scale is provided alongside each image.

The equilibrium swelling ratios (Q) were statistically equivalent for the control and pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels synthesized at all polymer concentrations, Table 1. This finding is interesting as PDA has previously been shown to inhibit hydrogel swelling.12 Therefore, the strong interaction of the zwitterionic polymer with water likely overcame any swelling inhibition that would otherwise be induced by PDA. The PEG hydrogels were covalently crosslinked through methacrylate moieties; their approximate mesh size (ξ) was calculated using the Peppas modification of Flory theory.52 The mesh size was determined to be 3.4 ± 0.2 nm, 1.9 ± 0.1 nm, and 1.0 ± 0.1 nm for 8.3 wt%, 28 wt%, and 55 wt% PEG hydrogels, respectively. In contrast, the agar hydrogels are physically crosslinked networks with large pores. Cyro-SEM has been used to approximate the pores of 1.0 wt% agar hydrogels to range from 370 to 800 nm in diameter53 and the equilibrium swelling of other biopolymer hydrogels has been reported to range from 400 – 6600% with large deviations.54 Thus, the effect of pMPC/PDA on the equilibrium swelling of agar hydrogels could not be determined reliably. In general, the smallest pore size of agar hydrogels is much larger than that of the PEG hydrogels and therefore provided no barrier for pMPC/PDA diffusion. Thus, pMPC/PDA was successfully incorporated into both PEG and agar hydrogels despite substantial differences in their crosslinking chemistry, architecture, and network construction.

Table 1.

Storage modulus (G’), loss modulus (G”), volumetric swelling ratio (Q), and mesh size (ξ) of unmodified and pMPC/PDA-modified PEG and agar hydrogels.

| PEG Hydrogels | pMPC/PDA PEG Hydrogels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG (wt%) |

G′ (kPa) |

G″ (kPa) |

Q | G′ (kPa) |

G″ (kPa) |

Q | ξ (nm) |

| 8.3 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 13 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 11 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 0.2 |

| 28 | 77 ± 3 | 3 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 94 ± 18 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.04 |

| 55 | 1300±200 | 190 ± 5 | 2.2 ± 0.05 | 1300±60 | 60 ± 10 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| Agar Hydrogels | pMPC/PDA Agar Hydrogels | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agar (wt%) |

G′9br/)(kPa) | G″ (kPa) |

G′ (kPa) |

G″ (kPa) |

| 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.06 ± 0.01 |

| 3 | 30 ± 4 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 37 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.8 |

| 9.0 | 370 ± 50 | 52 ± 11 | 240 ± 25 | 60 ± 30 |

Mechanical Characteristics of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

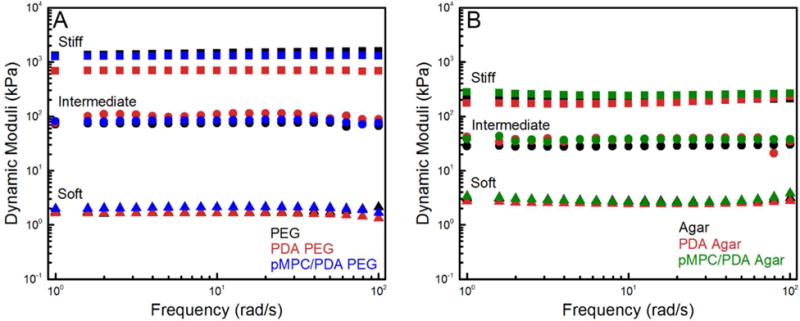

Hydrogel stiffness is intrinsically tied to polymer concentration, with increasing concentration leading to an increased crosslink density and stiffness.55 Small amplitude oscillatory shear (SAOS) measurements indicated that the elastic component dominated the complex modulus and G′ displayed frequency independence for the PEG (8.3, 28, and 55 wt%) and agar (1.0, 3.0, and 9.0 wt%) hydrogels, Figure S4. Based on their dynamic moduli, and to simplify the naming of the hydrogels, we categorized them into three regimes: soft (1.7 ± 0.1 kPa PEG and 2.5 ± 0.4 kPa agar), intermediate (110 ± 40 kPa PEG and 30 ± 4.0 kPa agar), and stiff (1300 kPa ± 200 PEG and 370 ± 50 kPa agar).

Ideally, introducing a second polymer network, such as pMPC/PDA, would not disrupt the original hydrogel network, and would either improve or maintain mechanical strength without sacrificing chemical stability.56 Following PDA or pMPC/PDA polymerization, the mechanical properties of the PEG and agar hydrogels displayed minimal variation from the unmodified hydrogels, Figure 3 and Table 1. For example, the intermediate PEG hydrogels had statistically equivalent G’ values of 110 ± 40 kPa, 100 ± 6.0 kPa, and 94.0 ± 18 kPa for the unmodified, PDA, and pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels, respectively.

Figure 3.

Representative frequency sweeps of unmodified, as well as PDA and pMPC/PDA-modified (A) PEG and (B) agar hydrogels. PEG hydrogels (8.3, 28, and 55 wt% PEG) and agar hydrogels (1.0, 3.0, and 9.0 wt% agar) are labeled as soft, intermediate, and stiff, respectively, to simplify sample labeling.

After PDA incorporation, the stiff PDA PEG hydrogels displayed a significant loss in mechanical strength: G′ decreased from 1300 ± 230 kPa to 710 ± 20 kPa and G″ decreased from 190 ± 5.0 to 20 ± 1.0 kPa. Interestingly, stiff pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels displayed a comparable G′ to the unmodified PEG hydrogels, 1300 ± 6.0 kPa, but a smaller G″ of 63 ± 13 kPa. Agar hydrogels displayed no difference in G′ or G″ following PDA or pMPC/PDA polymerization for soft, intermediate, and stiff hydrogels, Figure 3B. The changes in the mechanical properties of PEG hydrogels following PDA formation are likely linked to the mesh size of the PEG network. The 1.0 – 3.4 nm mesh size of the PEG hydrogels generally excluded PDA aggregate diffusion into the hydrogel interior. SEM imaging of many hydrogel cross-sections showed little evidence of large PDA-aggregates, Figure S2. However, the larger aggregates arising from PDA-only polymerization potentially disrupted the network structure of the stiff PEG hydrogels and contributed to a reduction in G’; whereas the hydrogel network structure was unaffected by the smaller (<150 nm) pMPC/PDA aggregates. The similar mechanical properties of the agar hydrogels, before and after PDA and pMPC/PDA polymerization, is likely due to their large pore structure, reducing the effect of PDA aggregates on the mechanical properties; SEM imaging confirmed that no large aggregates were observed within the agar hydrogels.

Protein Resistance of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

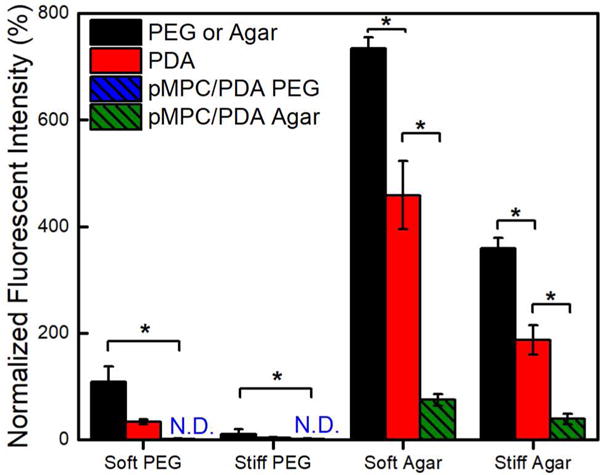

The fouling resistance of PEG and agar hydrogels with and without PDA and pMPC/PDA was evaluated by a fluorescent protein assay using fibrinogen, a model serum protein. After 24 h exposure to a solution of 100 μg/cm2 fibrinogen, a minimal yet quantifiable amount of protein adsorption was detected via fluorescence microscopy on the PEG hydrogels, whereas a significant amount of fibrinogen adsorbed to the agar hydrogels, Figures 4,S5, S6 and Table 2. Compared to unmodified hydrogel controls, a statistically significant improvement was observed for both PEG and agar hydrogels following PDA formation.35 A non-detectible amount of fibrinogen adhered to the pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels; previous literature has benchmarked this achievement as “ultralow-fouling” behavior.23,57 The 99% improvement in antifouling performance following pMPC/PDA incorporation indicates an impressively synergistic relationship between PEG and pMPC, because PEG hydrogels are already quite resistant to protein adsorption. On the other hand, agar hydrogels are high-fouling and well-known to readily adsorb protein when challenged.58 The improvement in fibrinogen resistance on agar hydrogels was incredibly pronounced; pMPC/PDA agar hydrogels adsorbed 10 times less fibrinogen (70 ± 10 units) in comparison to unmodified agar hydrogels (730 ± 20 units). Remarkably, the inclusion of pMPC/PDA enabled the agar hydrogels to resist protein fouling almost as effectively as the PEG hydrogels.

Figure 4.

Protein adsorption to unmodified and pMPC/PDA-modified PEG and agar hydrogels following incubation with fibrinogen. The fluorescence intensity of irreversibly adsorbed fibrinogen was quantified and normalized against protein-free controls. Adsorption below the detection limit is labeled not-detected (N.D.). One asterisk (*) denotes p < 0.001 significance.

Table 2.

Fibrinogen adsorption on PDA and pMPC/PDA-modified hydrogels compared to unmodified controls.

| Hydrogel | Fibrinogen Adsorption (EGFP unit count) |

Fibrinogen Adsorption (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified | +PDA | +pMPC/PDA | +PDA | +pMPC/PDA | |

| Soft PEG | 110 ± 30 | 30 ± 4 | N.D. | 31 | <1 |

| Stiff PEG | 10 ± 10 | 4.0 ± 1 | N.D. | 36 | <1 |

| Soft Agar | 730 ± 20 | 460 ± 60 | 70 ± 10 | 62 | 10 |

| Stiff Agar | 360 ± 20 | 190 ± 30 | 40 ± 10 | 52 | 11 |

Bacterial Resistance of pMPC/PDA-Modified PEG and Agar Hydrogels

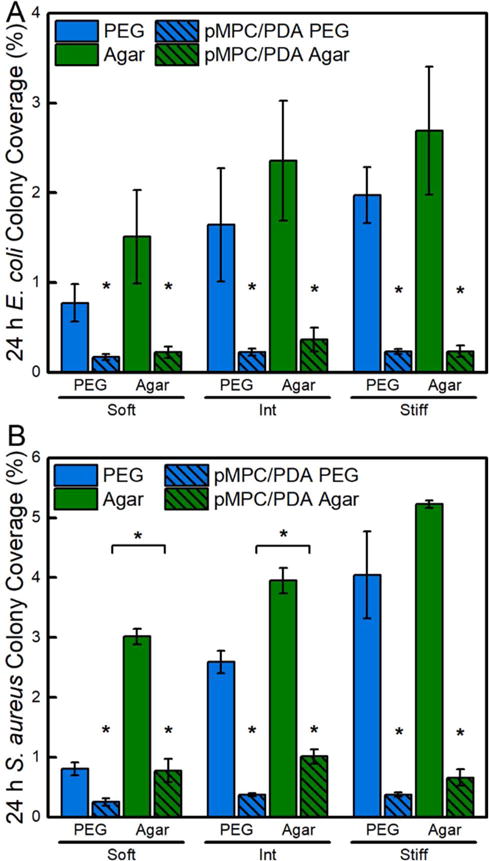

Unmodified and pMPC/PDA-modified PEG and agar hydrogels were challenged for 24 h with two model bacterial species, Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli. Glass coverslips, PDA, and pMPC/PDA thin films (on glass) served as control samples. Despite their resistance to fibrinogen adsorption, S. aureus and E. coli adhesion occurred on PEG hydrogels, Figure 5. As expected from the known prevalence of protein adsorption to agar hydrogels,58 both bacteria adhered more readily to agar than PEG. Qualitative indications of early biofilm development, i.e., the clustering of S. aureus into microcolonies, was observed on the stiffest unmodified PEG and agar hydrogels, Figure S7. Consistent with our previous work,16 bacteria coverage increased with stiffness on the unmodified hydrogels. For both bacterial species there was a positive correlation between bacterial colony surface coverage and hydrogel stiffness on both hydrogels. For example, E. coli adhesion on soft PEG hydrogels (0.77%) was significantly less (p-value <0.01) than on the intermediate PEG hydrogels (1.64%), and the intermediate PEG displayed significantly less E. coli adhesion than the stiff PEG hydrogels (1.97%). The same trend was displayed for E. coli adhesion on soft agar (1.51%), intermediate agar (2.69%), and stiff agar (3.68%), as well as S. aureus on each hydrogel system with increasing stiffness.

Figure 5.

Adhesion of (A) E. coli and (B) S. aureus on unmodified and pMPC/PDA-modified PEG and agar hydrogels. Hydrogels are grouped by their storage moduli: soft, intermediate, and stiff. E. coli and S. aureus adhesion was statistically different (p-value <0.01) on unmodified PEG and unmodified agar hydrogels in different stiffness regimes; for simplicity, these statistical markings are not shown. The difference between unmodified and pMPC/PDA-modified hydrogels is statistically significant (p-value < 0.01) for all samples and displayed on the plots. One asterisk (*) denotes p < 0.001 intra-sample significance and brackets denotes p < 0.001 inter-sample hydrogels significance. Standard error is displayed.

Although PDA surface modification reduced bacterial adhesion, PDA functionalization alone is insufficient to substantially resist long-term adhesion of either bacterial species, Figure S8.59,60 For example, although PDA reduced S. aureus colony coverage from 6.2 ± 1.0% to 3.6 ± 1.0% compared to unmodified glass, pMPC/PDA-functionalized surfaces much more significantly reduced bacterial surface coverage, by an additional 5 times to 0.7 ± 0.1%. All of the pMPC/PDA hydrogels displayed significantly less bacterial adhesion than the unmodified controls and lacked signs of colony formation from either bacterial species. Interestingly, E. coli colony coverage was consistent on all surfaces following pMPC/PDA formation, including thin film controls and normally high-fouling agar hydrogels. Quantitatively, E. coli adhesion was statistically equivalent on soft, intermediate, and stiff pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels with colony area coverages of 0.17 ± 0.03%, 0.23 ± 0.04%, and 0.23 ± 0.03%, respectively. E. coli attachment was reduced by 5, 7, and 9 times on pMPC/PDA-modified PEG hydrogels compared to unmodified PEG hydrogels. Our antifouling results compare favorably to the work by Cheng, et al. who found that surfaces grafted via atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) with a long-chain zwitterionic poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) significantly reduced the colony coverage of Staphylococcus epidermis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by greater than 80% compared to glass controls.61 Further, E. coli colony coverages of 0.22 ± 0.07%, 0.37 ± 0.13%, and 0.23 ± 0.06% were observed on soft, intermediate, and stiff pMPC/PDA agar hydrogels; values that are statistically equivalent to pMPC/PDA thin film controls (0.22 ± 0.07%) and all pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels. The improvement in the fouling resistance of pMPC/PDA agar hydrogels is especially remarkable and demonstrates that the strong antifouling properties provided by the pMPC can be applied successfully to either hydrogel composition.

PMPC/PDA-modified PEG hydrogels exhibited superior resistance to S. aureus adhesion relative to pMPC/PDA modified agar or thin film controls (Figure 5B and S8). S. aureus adhesion was statistically equivalent on soft, intermediate, and stiff pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels with colony area coverages of 0.25 ± 0.06%, 0.37 ± 0.02%, and 0.37 ± 0.04%, respectively. Notably, soft, intermediate, and stiff pMPC/PDA agar hydrogels displayed S. aureus colony area coverages of 0.78 ± 0.20%, 1.0 ± 0.12%, and 0.65 ± 0.14%, respectively. These functionalized agar hydrogels supported 4 times fewer microbes than the unmodified agar hydrogels, but significantly more microbes than the pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels. Further, the pMPC/PDA thin film controls displayed an impressive 9 times reduction in S. aureus adhesion, from 6.2 ± 1.0% to 0.68 ± 0.06% S. aureus compared to unmodified glass controls, Table S1. Therefore, the superior performance of pMPC/PDA PEG hydrogels likely resulted from a combination of the antifouling activity of both PEG and pMPC. The increased adhesion of S. aureus to pMPC/PDA agar compared to pMPC/PDA PEG is likely due to the unique membrane-bound protein-binding adhesins in S. aureus that facilitates attachment to human tissue, enhancing interaction with the bioinspired MPC structure.62,63 This is consistent with literature reports, which demonstrate that the chemical composition and physical architecture of abiotic materials is known to induce a greater variation in S. aureus adhesion than E. coli.64,65

CONCLUSION

We have presented a simple and versatile technique to enhance the fouling resistance of hydrogels with polymer zwitterions, independent of the network structure and mechanical properties of the original hydrogel. Using a simple, solution-based approach, a fouling-resistant polymer zwitterion, pMPC, was integrated into PEG and agar hydrogels during hydrogel swelling to facilitate uniform pMPC/PDA incorporation without sacrificing the integrity of the original hydrogel network. The inclusion of this fouling-resistant polymer network successfully reduced fibrinogen adsorption on agar by over 90%, transforming a culture medium for bacteria into a fouling-resistant material. Relative to unmodified PEG and agar hydrogels, E. coli and S. aureus adhesion was significantly reduced (up to 91%) on all hydrogels following pMPC/PDA formation. PDA-mediated integration of polymer zwitterions offers a simple and versatile platform to enhance the antifouling performance of hydrogels without altering the mechanical properties of the original hydrogel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Nathan P. Birch, Natalie R. Mako, and Xiangxi Meng for assistance with experiments and helpful discussions. K.W.K. was supported by the National Research Service Award T32 GM008515 from the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported in part by a fellowship given by UMass to KMD as part of the Biotechnology Training Program (NIH, National Research Service Award T32 GM108556). J.D.S. acknowledges the support of the National Science Foundation (NSF CBET-1719747).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Figure S1 provides FTIR spectra. Additional methods to functionalize hydrogels are provided. Figure S2 provides hydrogel cross-sections and analysis of PDA diffusion/polymerization. Figure S3 provides cross-sectional SEM micrographs. Figure S4 provides the storage and viscous moduli of hydrogels. Figures S5 and S6 provides micrographs and fluorescence spectra of fibrinogen adsorption on hydrogels. Figure S7 provides micrographs of E. coli and S. aureus adhesion. Table S1 provides total colony area coverage of E. coli and S. aureus. Figure S8 provides colony coverage of E. coli and S. aureus on glass. The Supporting Information is available and free of charge http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Von Eiff C, Jansen B, Kohnen W, Becker K. Infections Associated with Medical Devices: Pathogenesis, Management and Prophylaxis. Drugs. 2005;65:179–214. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meddings J, Rogers MAM, Krein SL, Fakih MG, Olmsted RN, Saint S. Reducing Unnecessary Urinary Catheter Use and Other Strategies to Prevent Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection: An Integrative Review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:277–289. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Raad II, Randolph A, Rupp ME, Saint S. Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011:1–83. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klevens RM, Edwards JR, Richards CL, Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Pollock Da, Cardo DM. Estimating Health Care-Associated Infections and Deaths in U.S. Hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122:160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennedy EH, Greene MT, Saint S. Estimating Hospital Costs of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:519–522. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati G, Kainer MA, Lynfield R, Maloney M, McAllister-Hollod L, Nadle J, Ray SM, Thompson DL, Wilson LE, Fridkin SK. Multistate Point-Prevalence Survey of Health Care–Associated Infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1198–1208. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence EL, Turner IG. Materials for Urinary Catheters: A Review of Their History and Development in the UK. Med Eng Phys. 2005;27:443–453. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagur-Grodzinski J. Nanostructured Polyolefins / Clay Composites?: Role of the Molecular Interaction at the Interface. Polym Adv Technol. 2006;17:395–418. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beiko DT, Knudsen BE, Watterson JD, Cadieux PA, Reid G, Denstedt JD. Urinary Tract Biomaterials. J Urol. 2004;171:2438–2444. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125001.56045.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee I, Pangule RC, Kane RS. Antifouling Coatings: Recent Developments in the Design of Surfaces That Prevent Fouling by Proteins, Bacteria, and Marine Organisms. Adv Mater. 2011;23:690–718. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnan S, Weinman CJ, Ober CK. Advances in Polymers for Anti-Biofouling Surfaces. J Mater Chem. 2008;18:3405–3413. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrwerth S, Eck W, Reinhardt S, Grunze M. Factors That Determine the Protein Resistance of Oligoether Self-Assembled Monolayers - Internal Hydrophilicity, Terminal Hydrophilicity, and Lateral Packing Density. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9359–9366. doi: 10.1021/ja034820y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guégan C, Garderes J, Le Pennec G, Gaillard F, Fay F, Linossier I, Herry JM, Fontaine MNB, Réhel KV. Alteration of Bacterial Adhesion Induced by the Substrate Stiffness. Colloids Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 2014;114:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallardo A, Martínez-Campos E, García C, Cortajarena AL, Rodríguez-Hernández J. Hydrogels with Modulated Ionic Load for Mammalian Cell Harvesting with Reduced Bacterial Adhesion. Biomacromolecules. 2017;18:1521–1531. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolewe KW, Zhu J, Mako NR, Nonnenmann SS, Schiffman JD. Bacterial Adhesion Is Affected by the Thickness and Stiffness of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:2275–2281. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b12145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolewe K, Peyton SR, Schiffman JD. Fewer Bacteria Adhere to Softer Hydrogels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:19562–19569. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b04269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventola CL. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis: Part 1: Causes and Threats. P T A peer-reviewed J Formul Manag. 2015;40:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arias CA, Murray BE. Antibiotic-Resistant Bugs in the 21st Century — A Clinical Super-Challenge. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:439–443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0804651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Li L, Zhao C, Zheng J. Surface Hydration: Principles and Applications toward Low-Fouling/Nonfouling Biomaterials. Polymer. 2010;51:5283–5293. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao B, Tang Q, Cheng G. Recent Advances of Zwitterionic Carboxybetaine Materials and Their Derivatives. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2014;25:1502–1513. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2014.927300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tegoulia Va, Rao W, Kalambur AT, Rabolt JF, Cooper SL. Surface Properties, Fibrinogen Adsorption, and Cellular Interactions of a Novel Phosphorylcholine-Containing Self-Assembled Monolayer on Gold. Langmuir. 2001;17:4396–4404. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuang J, Messersmith PB. Universal Surface-Initiated Polymerization of Antifouling Zwitterionic Brushes Using a Mussel-Mimetic Peptide Initiator. Langmuir. 2012;28:7258–7266. doi: 10.1021/la300738e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang S, Cao Z. Ultralow-Fouling, Functionalizable, and Hydrolyzable Zwitterionic Materials and Their Derivatives for Biological Applications. Adv Mater. 2010;22:920–932. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Z, Chao T, Liu LY, Cheng G, Ratner BD, Jiang S. Zwitterionic Hydrogels: An in Vivo Implantation Study. J Biomater Sci Ed. 2009;20:1845–1859. doi: 10.1163/156856208X386444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, Cao Z, Bai T, Carr L, Ella-Menye J-R, Irvin C, Ratner BD, Jiang S. Zwitterionic Hydrogels Implanted in Mice Resist the Foreign-Body Reaction. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:553–556. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao B, Li L, Tang Q, Cheng G. The Impact of Structure on Elasticity, Switchability, Stability and Functionality of an All-in-One Carboxybetaine Elastomer. Biomaterials. 2013;34:7592–7600. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ning J, Li G, Haraguchi K. Synthesis of Highly Stretchable, Mechanically Tough, Zwitterionic Sulfobetaine Nanocomposite Gels with Controlled Thermosensitivities. Macromolecules. 2013;46:5317–5328. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin H, Akasaki T, Lin Sun T, Nakajima T, Kurokawa T, Nonoyama T, Taira T, Saruwatari Y, Ping Gong J. Double Network Hydrogels from Polyzwitterions: High Mechanical Strength and Excellent Anti-Biofouling Properties. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:3685–3693. doi: 10.1039/c3tb20324g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carr LR, Zhou Y, Krause JE, Xue H, Jiang S. Uniform Zwitterionic Polymer Hydrogels with a Nonfouling and Functionalizable Crosslinker Using Photopolymerization. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6893–6899. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao B, Tang Q, Li L, Humble J, Wu H, Liu L, Cheng G. Switchable Antimicrobial and Antifouling Hydrogels with Enhanced Mechanical Properties. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee H, Dellatore SM, Miller WM, Messersmith PB. Mussel-Inspired Surface Chemistry for Multifunctional Coatings. Science. 2007;318:426–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1147241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Ai K, Lu L. Polydopamine and Its Derivative Materials: Synthesis and Promising Applications in Energy, Environmental, and Biomedical Fields. Chem Rev. 2014;114:5057–5115. doi: 10.1021/cr400407a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou R, Ren PF, Yang HC, Xu ZK. Fabrication of Antifouling Membrane Surface by Poly(Sulfobetaine Methacrylate)/Polydopamine Co-Deposition. J Memb Sci. 2014;466:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang C-C, Kolewe KW, Li Y, Kosif I, Freeman BD, Carter KR, Schiffman JD, Emrick T. Underwater Superoleophobic Surfaces Prepared from Polymer Zwitterion/Dopamine Composite Coatings. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2016;3:521–530. doi: 10.1002/admi.201500521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolewe KW, Dobosz KM, Rieger KA, Chang C-C, Emrick T, Schiffman JD. Antifouling Electrospun Nanofiber Mats Functionalized with Polymer Zwitterions. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:27585–27593. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b09839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sundaram HS, Han X, Nowinski AK, Brault ND, Li Y, Ella-Menye JR, Amoaka KA, Cook KE, Marek P, Senecal K, Jiang S. Achieving One-Step Surface Coating of Highly Hydrophilic Poly(Carboxybetaine Methacrylate) Polymers on Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Surfaces. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2014;1:1–8. doi: 10.1002/admi.201400071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang SM, Hwang NS, Yeom J, Park SY, Messersmith PB, Choi IS, Langer R, Anderson DG, Lee H. One-Step Multipurpose Surface Functionalization by Adhesive Catecholamine. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:2949–2955. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201200177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang C, Li H-N, Du Y, Ma M-Q, Xu Z-K. CuSO4/H2O2-Triggered Polydopamine/Poly(Sulfobetaine Methacrylate) Coatings for Antifouling Membrane Surfaces. Langmuir. 2017;33:1210–1216. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cencer M, Liu Y, Winter A, Murley M, Meng H, Lee BP. Effect of PH on the Rate of Curing and Bioadhesive Properties of Dopamine Functionalized Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:2861–2869. doi: 10.1021/bm500701u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Meng H, Konst S, Sarmiento R, Rajachar R, Lee BP. Injectable Dopamine-Modified Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Nanocomposite Hydrogel with Enhanced Adhesive Property and Bioactivity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:16982–16992. doi: 10.1021/am504566v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun P, Wang J, Yao X, Peng Y, Tu X, Du P, Zheng Z, Wang X. Facile Preparation of Mussel-Inspired Polyurethane Hydrogel and Its Rapid Curing Behavior. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:12495–12504. doi: 10.1021/am502106e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu VA, Bhatia SN. Three-Dimensional Patterning of Hydrogels Containing Living Cells. Biomed Microdevices. 2002;4:257–266. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhuchar N, Deng Z, Ishihara K, Narain R. Detailed Study of the Reversible Addition–fragmentation Chain Transfer Polymerization and Co-Polymerization of 2-Methacryloyloxyethyl Phosphorylcholine. Polym Chem. 2011;2:632–639. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wertz CF, Santore MM. Adsorption and Relaxation Kinetics of Albumin and Fibrinogen on Hydrophobic Surfaces: Single-Species and Competitive Behavior. Langmuir. 1999;15:8884–8894. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robeson JL, Tilton RD. Effect of Concentration Quenching on Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching Measurements. Biophys J. 1995;68:2145–2155. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pang YY, Schwartz J, Thoendel M, Ackermann LW, Horswill AR, Nauseef WM. Agr-Dependent Interactions of Staphylococcus aureusUSA300 with Human Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:546–559. doi: 10.1159/000319855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zodrow KR, Schiffman JD, Elimelech M. Biodegradable Polymer (PLGA) Coatings Featuring Cinnamaldehyde and Carvacrol Mitigate Biofilm Formation. Langmuir. 2012;28:13993–13999. doi: 10.1021/la303286v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fux CA, Wilson S, Stoodley P. Detachment Characteristics and Oxacillin Resistance of Staphoccocus aureusBiofilm Emboli in an In Vitro Catheter Infection Model. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:4486–4491. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4486-4491.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung KK, Schumacher JF, Sampson EM, Burne RA, Antonelli PJ, Brennan AB. Impact of Engineered Surface Microtopography on Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus. Biointerphases. 2007;2:89–94. doi: 10.1116/1.2751405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong S, Na YS, Choi S, Song IT, Kim WY, Lee H. Non-Covalent Self-Assembly and Covalent Polymerization Co-Contribute to Polydopamine Formation. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:4711–4717. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding Y, Weng L-T, Yang M, Yang Z, Lu X, Huang N, Leng Y. Insights into the Aggregation/Deposition and Structure of a Polydopamine Film. Langmuir. 2014;30:12258–12269. doi: 10.1021/la5026608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Canal T, Peppast NA. Correlation between Mesh Size and Equilibrium. J Biomed Mater Res. 1989;23:1183–1193. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820231007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rahbani J, Behzad AR, Khashab NM, Al-Ghoul M. Characterization of Internal Structure of Hydrated Agar and Gelatin Matrices by Cryo-SEM. Electrophoresis. 2013;34:405–408. doi: 10.1002/elps.201200434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birch NP, Barney LE, Pandres E, Peyton SR, Schiffman JD. Thermal-Responsive Behavior of a Cell Compatible Chitosan/Pectin Hydrogel. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:1837–1843. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seliktar D. Designing Cell-Compatible Hydrogels. Science. 2012;336:13–17. doi: 10.1126/science.1214804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haque MA, Kurokawa T, Gong JP. Super Tough Double Network Hydrogels and Their Application as Biomaterials. Polymer. 2012;53:1805–1822. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai WB, Grunkemeier JM, Horbett TA. Human Plasma Fibrinogen Adsorption and Platelet Adhesion to Polystyrene. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;44:130–139. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199902)44:2<130::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen H, Chen Q, Hu R, Wang H, Newby BZ, Chang Y, Zheng J. Mechanically Strong Hybrid Double Network Hydrogels with Antifouling Properties. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3:5426–5435. doi: 10.1039/c5tb00681c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sileika TS, Kim HDo, Maniak P, Messersmith PB. Antibacterial Performance of Polydopamine-Modified Polymer Surfaces Containing Passive and Active Components. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:4602–4610. doi: 10.1021/am200978h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cui J, Ju Y, Liang K, Ejima H, Lörcher S, Gause KT, Richardson JJ, Caruso F. Nanoscale Engineering of Low-Fouling Surfaces through Polydopamine Immobilisation of Zwitterionic Peptides. Soft Matter. 2014;10:2656–2663. doi: 10.1039/c3sm53056f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng G, Zhang Z, Chen S, Bryers JD, Jiang S. Inhibition of Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation on Zwitterionic Surfaces. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4192–4199. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Götz F. Staphylococcus and Biofilms. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;43:1367–1378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beloin C, Houry A, Froment M, Ghigo JM, Henry N. A Short-Time Scale Colloidal System Reveals Early Bacterial Adhesion Dynamics. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:1549–1558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gungor B, Esen Ş, Gök A, Yilmaz H, Malazgirt Z, Leblebicioglu H. Comparison of the Adherence of E.Coli and S. Aureus to Ten Different Prosthetic Mesh Grafts: In Vitro Experimental Study. Indian J Surg. 2010;72:226–231. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0061-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hsieh YL, Merry J. The Adherence of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidisand Escherichia colion Cotton, Polyester and Their Blends. J Appl Bacteriol. 1986;60:535–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1986.tb01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.