Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness and safety of dual agent antiplatelet therapy combining clopidogrel and aspirin to prevent recurrent thrombotic and bleeding events compared with aspirin alone in patients with acute minor ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, placebo controlled trials.

Data sources

Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Library, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO website, PsycINFO, and grey literature up to 4 July 2018.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies and methods

Two reviewers independently screened potentially eligible studies according to predefined selection criteria and assessed the risk of bias using a modified version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool. A third team member reviewed all final decisions, and the team resolved disagreements through discussion. When reports omitted data that were considered important, clarification and additional information was sought from the authors. The analysis was conducted in RevMan 5.3 and MAGICapp based on GRADE methodology.

Results

Three eligible trials involving 10 447 participants were identified. Compared with aspirin alone, dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin that was started within 24 hours of symptom onset reduced the risk of non-fatal recurrent stroke (relative risk 0.70, 95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.80, I2=0%, absolute risk reduction 1.9%, high quality evidence), without apparent impact on all cause mortality (1.27, 0.73 to 2.23, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) but with a likely increase in moderate or severe extracranial bleeding (1.71, 0.92 to 3.20, I2=32%, absolute risk increase 0.2%, moderate quality evidence). Most stroke events, and the separation in incidence curves between dual and single therapy arms, occurred within 10 days of randomisation; any benefit after 21 days is extremely unlikely.

Conclusions

Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin given within 24 hours after high risk TIA or minor ischaemic stroke reduces subsequent stroke by about 20 in 1000 population, with a possible increase in moderate to severe bleeding of 2 per 1000 population. Discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy within 21 days, and possibly as early as 10 days, of initiation is likely to maximise benefit and minimise harms.

Introduction

Minor ischaemic strokes or transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) put patients at risk of subsequent cardiovascular events, including devastating major strokes.1 2 Clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown that patients who experience minor ischaemic strokes or TIAs benefit from antiplatelet therapy.3 Consequently, current guidelines for the management of acute ischaemic stroke and TIA recommend antiplatelet therapy—typically providing strong recommendations for use of a single agent, most commonly aspirin.4 5 6 7 One guideline provides a weak recommendation for clopidogrel and aspirin therapy, initiated within 24 hours of a patient presenting with minor stroke or TIA, and continuing for 21 days.8

Several trials have tested the effectiveness and safety of clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone to prevent recurrent events in patients experiencing non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke or TIA in both the acute phase9 10 and the chronic phase.11 12 13 The Clopidogrel in High-risk patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial reported that adding clopidogrel to aspirin starting within 24 hours of a minor stroke or TIA and continuing for 21 days reduced stroke risk without increasing the risk of moderate or severe haemorrhage at three and 12 months.9 14

Despite findings from the CHANCE trial, many guideline recommendations persisted in recommending single rather than dual agent clopidogrel and aspirin for the initial treatment of minor ischaemic stroke or TIA.4 15 16 Rationales provided by guideline authors for not recommending routine dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with minor stroke or TIA included the possibility that the aetiological case-mix of stroke in Chinese patients could differ from populations in other regions (Europe and North America), particularly in the higher frequency of intracranial atherosclerosis, and that secondary prevention strategies in China might differ in important ways from Western settings.17 18 19 Thus, guideline developers commented on the need to await findings from ongoing randomised controlled trials in more diverse populations.

Recently, the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischaemic Stroke (POINT) study,20 a randomised, blinded, placebo controlled trial, reported on the effectiveness and safety of clopidogrel and aspirin use versus aspirin alone. Although both POINT and CHANCE included patients with minor ischaemic stroke or TIA, the population in POINT was more ethnically and geographically diverse. The 28% reduction in hazard of stroke reported by the POINT authors mandates a new review to inform the optimal management of these patients.

We performed an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, placebo controlled trials that enrolled patients with non-cardioembolic minor ischaemic stroke or high risk TIA within three days of presentation and addressed the effectiveness and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin versus either agent alone. This systematic review is part of the BMJ Rapid Recommendations project, a collaborative effort from the MAGIC research and innovation programme (www.magicproject.org) and The BMJ.21 The aim of the project is to respond to new potentially practice changing evidence and provide trustworthy practice guidelines in a timely manner. This systematic review informs a parallel clinical practice guideline to be published in a multilayered electronic format in The BMJ and MAGICapp.

Methods

Guideline panel and patient involvement

According to the BMJ Rapid Recommendations process, a multiprofessional guideline panel that included three patients who had experienced an ischaemic stroke provided oversight to the systematic review and identified populations and outcomes of interest. All outcomes identified by the panel, and in particular, by the patients, were included in the review.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible the studies had to be randomised, placebo controlled trials and include patients with a diagnosis of an acute minor ischaemic stroke or high risk TIA, treatment onset within three days, and intervention of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin or clopidogrel alone. The trials also had to report on at least one of the following outcomes up to 90 days: all cause and stroke specific mortality, non-fatal ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke, extracranial haemorrhage (mild, moderate, or severe), TIA, myocardial infarction, functional status, and quality of life.

We excluded studies in which more than 20% of patients experienced cardioembolic ischaemic stroke or TIA that failed to report data specific to the subgroup with non-cardioembolic stroke; crossover studies; and studies published only in abstract form.

Search methods

We identified a 2013 meta-analysis addressing early dual versus single antiplatelet therapy for acute ischaemic stroke or TIA22 and judged that the search, up to November 2012, was comprehensive. We evaluated all 14 studies included in that review for eligibility, and then conducted a comprehensive search for other relevant studies from January 2012 to July 2018.

Medline, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane library, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO website, PsycINFO, and grey literature (www.opengrey.eu/) were searched. The search strategy included the keywords “antiplatelet therapy”, “aspirin”, “acetylsalicylic acid”, “ASA”; “clopidogrel”, “Plavix”, “Iscover”, “thienopyridines”, “ADP receptor inhibitors”, “stroke”, “cerebral ischemia”, “cerebral infarction”, “transient ischaemic attack”, “TIA”, and “randomised controlled trial”.

To identify trials that may not have been published in full or were missed through the electronic search, investigators manually searched all references from the included studies and relevant previous systematic reviews. Appendix 1 presents the full search.

Data collection

Two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract and full text levels of potentially eligible studies. A third team member reviewed all final decisions, and the team resolved disagreements through discussion. This process also applied to risk of bias ratings and extraction of key variables (eg, numbers of events). When reports omitted data that we considered important, we contacted authors for clarification and additional information.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers independently extracted several data using a predesigned data extraction form: characteristics of enrolled patient population, description of intervention and control, and description and event rate of patient important outcomes. To determine the timeframe of any apparent benefit, we reviewed incidence curves presented in the primary studies.

Assessment of risk of bias

To address risk of bias we used a modified version of the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials.23 24 25 26 We assessed the generation for random sequence; concealment for allocation sequence; blinding of participants, healthcare providers, data collectors, and outcome assessors or adjudicators, or both; incomplete outcome data (missing or lost to follow-up) (we judged low risk of bias if the rate of missing data was lower than 10%); and other potential sources of bias (ie, early trial discontinuation).

We rated the overall risk of bias for each study as the highest risk of bias for any criterion. We evaluated risk of bias on an outcome-by-outcome basis and noted any differences across outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Our primary analyses were based on the numbers of events in each intervention and control group. We used DerSimonian and Laird random effects models in RevMan 5.3 to conduct the meta-analyses. Study weights were generated using the inverse of the variance.

We present results as relative risks and associated 95% confidence intervals. The χ2 test for heterogeneity and the I2 statistic were used to assess heterogeneity between studies.

As the POINT study enrolled a diverse, multinational population who underwent contemporary stroke management, we applied the relative risks to the baseline risks from this trial to calculate absolute effects (eg, 6.4% risk for recurrent stroke).

As authors used different terms to categorise symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage, symptomatic subdural haemorrhage, and symptomatic subarachnoid haemorrhage, we consider the functional consequences of these events sufficiently similar to include in a composite variable of symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage. Considering that death from intracranial or extracranial bleeding, or from ischaemic stroke, are equally important, and that non-fatal haemorrhagic and ischaemic stroke have a similar distribution of functional outcomes, we considered our key outcomes all cause mortality, non-fatal stroke, and non-fatal serious bleeding.

Studies did not report outcomes exactly as we defined them; for instance, studies reported all cause mortality and all ischaemic stroke (including fatal and non-fatal), so in effect double counting ischaemic stroke mortality that contributes to both all cause mortality and ischaemic stroke. The limitation necessitated contact with authors to obtain the appropriate data for our analytical approach.

To address timing of discontinuation of clopidogrel, the guideline panellists visually inspected the incidence curves of the individual studies and hypothesised that most of the difference between dual antiplatelet therapy and aspirin in stroke occurs up to day 10, then a smaller difference between days 11 and 21, and no difference after day 21. They therefore constructed the intervention and comparator for the second PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) question as clopidogrel for 10 to 21 days versus clopidogrel for 22 to 90 days. They also hypothesised that the relative increase in bleeding risk would be similar between the intervention and comparator groups across the entire timeframe.

Using the stroke and major bleed probabilities plotted within the Kaplan-Meier curves of the two large eligible trials,9 27 we utilised the DigitizeIt software (DigitizeIt, Braunschweig, Germany) to obtain the incidence probabilities for both stroke and bleeding. For the POINT trial we used the entire 90 days of follow-up; for the CHANCE trial, because participants randomised to dual antiplatelet therapy were prescribed the treatment for only 21 days, we used data only up to day 21.

We then calculated the individual time-to-event patient data.28 We visually compared the original Kaplan-Meier curves with the reconstructed Kaplan-Meier curves to ensure accuracy of the simulated individual patient time-to-event data, as well as the calculated hazard ratios and their confidence intervals. We constructed curves both for the entire period and for the randomisation to day 10, 11 to 21, and 22 to 90 periods.

For each period we generated odds ratios by conducting logistic regressions to test the effect of dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin (independent variable) on stroke and bleeding (dependent variables) for days 0 to 10, 11 to 21, and 22 to 90. We also generated pooled Kaplan-Meier curves for each of these periods. Because the hazard changed over time we did not present a hazard ratio for the entire 90 days.

To calculate absolute effects, we utilised the simulated individual patient data to compare the risk difference for dual antiplatelet therapy versus aspirin up to day 10, days 11 to 21, and days 22 to 90.

Missing data

When studies reported missing data (loss to follow-up), we conducted a complete case analysis as our primary analysis. We also investigated the robustness of any outcome in which the confidence interval excluded no effect, by conducting a plausible worst case sensitivity analysis.29 This analysis attributed events in control patients lost to follow-up in the same ratio as those followed (eg, if there was a 5% event rate in control patients followed, we imputed a 5% event rate in control patients lost). For the intervention group, we imputed three times the rate of events in those lost to follow-up as those followed (eg, if there was a 5% event rate in intervention patients followed, we imputed a 15% event rate in intervention patients lost). For each study we then combined patients who were followed and those who were lost and pooled the new results across studies to determine the extent to which results are robust to these assumptions. Because most strokes occurred in the first seven days after randomisation, we used the seven day loss to follow-up reported in POINT rather than the 90 day loss to follow-up.

If at least three studies were available for each subgroup, we planned a subgroup analysis of studies judged at high risk of bias versus low risk of bias.

Quality of evidence

We used the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology to assess quality of evidence and presented the data using MAGICapp.30 We rated quality of evidence as very low, low, moderate, or high by assessing imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, publication bias, and the overall risk of bias, for each outcome. We developed summary of finding tables using MAGICapp and included the reasons for rating down the quality of the evidence.

Results

We requested information on the distribution of fatal and non-fatal outcomes from the principal investigators of two studies,9 20 both of whom provided the information necessary for our analytical approach.

Study identification

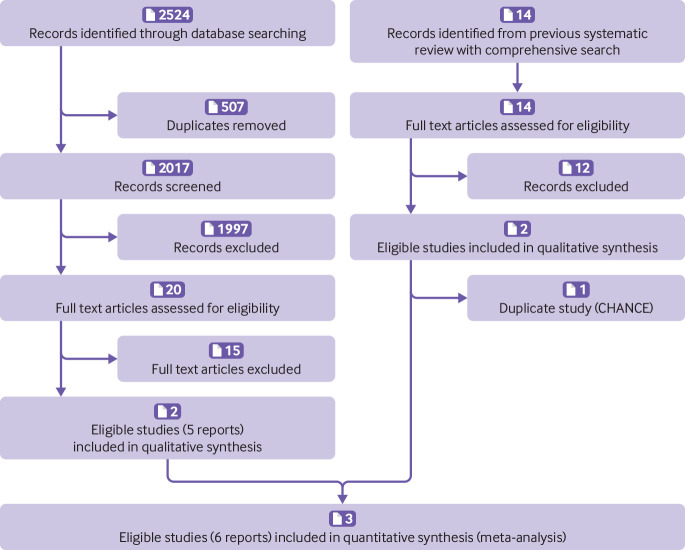

Figure 1 summarises our search for eligible studies. Of the 14 studies in the 2013 systematic review,22 two were eligible for our review.9 10 Our search of electronic databases retrieved 2524 records, of which 507 were duplicates. We excluded 2017 records based on title and abstract and assessed 20 full text articles, of which two were eligible.9 20 After removal of one duplicate study, three studies were eligible for review.9 10 20

Fig 1.

Flowchart for eligibility assessment according to PRISMA guidelines

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the three eligible trials involving 10 447 participants. One study used a factorial design including a comparison between simvastatin and placebo10; the other two studies each included two treatment arms.9 20 All studies enrolled patients with acute minor ischaemic stroke or high risk TIA within 12 or 24 hours after symptom onset, compared dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, and followed patients for 90 days. Sample size varied from 396 to 5170; the two largest trials9 20 contributed 10 051 patients. One trial was conducted in Asia,9 one in North America,10 and one in multiple countries.20 Patients with an indication for oral anticoagulant therapy (eg, atrial fibrillation) were excluded from the POINT and CHANCE trials. The mean or median age ranged from 62 to 69.8 years, and the proportion of men from 52.8% to 66.2%. All eligible studies reported recurrent stroke events (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) and bleeding events.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the three eligible trials

| Reference | Setting | Design | Proportion stroke/TIA | Sex (% men) | Age (years) | No of patients randomised (clopidogrel/no clopidogrel) | Treatment onset | Intervention with dosages | Control with dosages | Duration of treatment/control follow-up (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy (2007), FASTER | North America | Factorial design including a comparison between simvastatin and placebo | Acute minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3)/TIA (WHO definition): Proportion not reported | 52.8 | 68.1 (13.1)* | 396 (201/195) | <24 hours; median: 8.2-9.1 hours | Loading dose 300 mg clopidogrel followed by 75 mg clopidogrel daily+81 mg aspirin daily for study duration. If patient naive to aspirin, loading dose 162 mg aspirin followed by 75 mg clopidogrel+81 mg aspirin daily for study duration | 81 mg aspirin daily, with loading dose of 162 mg aspirin if patient naive to aspirin before study enrolment | 90/90 |

| Wang (2013), CHANCE | China | Two treatment arms | Acute minor stroke (NIHSS score ≤3)/high risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4): 72.1%/27.9% | 66.2 | Intervention: (63, 55-72); control: (62, 54-71)† | 5170 (2584/2586) | <24 hours; mean 13 hours | 75-300 mg aspirin at discretion of physician, and loading dose 300 mg clopidogrel on day 1, followed by 75 mg clopidogrel+75 mg aspirin daily on days 2-21. Day 22-90, 75 mg clopidogrel alone | 75-300 mg aspirin at discretion of physician on day 1. 75 mg aspirin daily on day 2-90 | 21/90 |

| Johnston (2018), POINT | North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand | Two treatment arms | Acute minor ischaemic stroke (NIHSS score ≤3)/high risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4): 56.8%/43.2% | 55.0 | Intervention: (65, 37-96); control: (65, 56-74)† | 4881 (2432/2449) | <12 hours; mean 7 hours | A loading dose of 600 mg clopidogrel on day 1, followed by 75 mg clopidogrel+50 to 325 mg aspirin daily from day 2 through 90. Recommended initial dose of 162 mg aspirin for 5 days, followed by 81 mg aspirin daily | 50-325 mg aspirin daily day 2-90. Recommended initial dose of 162 mg aspirin for 5 days, followed by 81 mg aspirin daily | 90/90 |

Mean (SD).

Median (range).

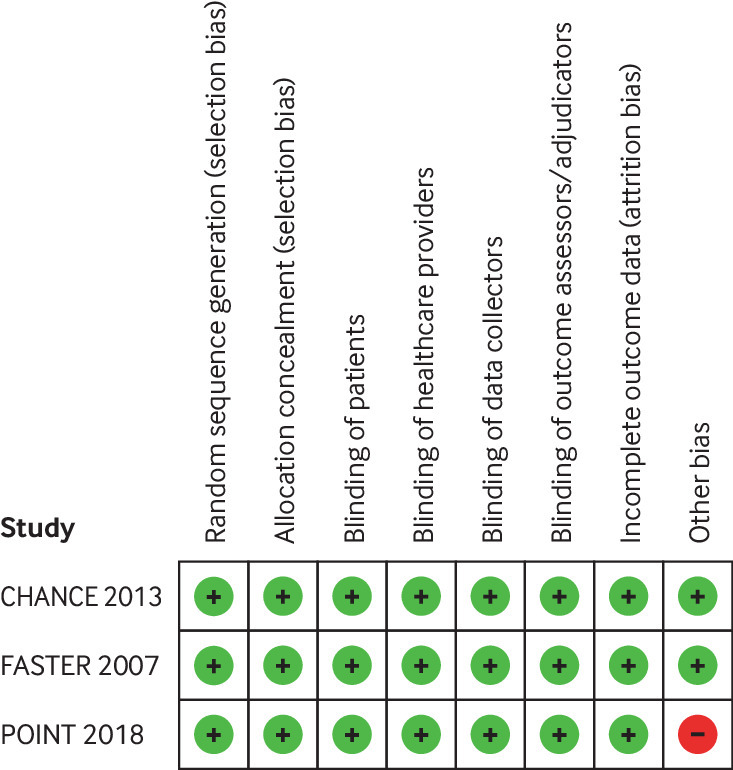

Risk of bias

Figure 2 summarises our risk of bias assessment. All judgments concluded low risk of bias (including incomplete outcome data—loss to follow-up ranged from 0.7%9 to 6.6%20), but one trial20 was discontinued owing to an increase in major haemorrhage, which likely results in an overestimate of the impact of dual antiplatelet therapy on this outcome.

Fig 2.

Risk of bias for each risk of bias item in included studies

Outcomes

Non-fatal recurrent stroke

Three studies including 10 301 patients9 10 20 reported the incidence of any non-fatal recurrent stroke. Pooled analysis showed that dual antiplatelet therapy started within 24 hours of symptom onset reduced the risk of non-fatal recurrent stroke (relative risk 0.70, 95% confidence interval 0.61 to 0.80, I2=0%, absolute risk reduction 1.9%, high quality evidence) (table 2, appendix 2, fig 1). This result was minimally changed in the sensitivity analysis that considered missing data (0.72, 0.63 to 0.82) (appendix 2, fig 2).

Table 2.

GRADE summary of findings for clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for the treatment of acute minor ischaemic stroke or high risk transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

| Outcome | Study results and measurements | Absolute effect estimates | Certainty in effect estimates (quality of evidence) | Plain text summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin alone | Clopidogrel and aspirin | ||||

| All non-fatal recurrent stroke | Relative risk 0.70 (9% CI 0.61 to 0.8). Based on data from 10 301 patients in three studies.* Follow-up 90 days | 63/1000 | 44/1000 | High | Dual antiplatelet therapy has small but important benefit in reducing recurrent strokes |

| Difference: 19 fewer per 1000 (95% CI 25 fewer to 13 fewer) | |||||

| All cause mortality | Relative risk 1.27 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.23). Based on data from 9690 patients in two studies.† Follow-up 90 days | 5/1000 | 6/1000 | Moderate: due to serious imprecision‡ | Dual antiplatelet therapy probably has little or no impact on all-cause mortality |

| Difference: 1 more per 1000 (95% CI 2 fewer to 4 more) | |||||

| Moderate or major extracranial haemorrhage defined by individual study (non-fatal) | Relative risk 1.71 (95% CI 0.92 to 3.20). Based on data from 10 075 patients in three studies.* Follow-up 90 days | 3/1000 | 5/1000 | Moderate: due to serious risk of bias and imprecisionठ| Dual antiplatelet therapy probably results in small, possibly important increase in moderate or major extracranial bleeding |

| Difference: 2 more per 1000 (95% CI 0 fewer to 7 more) | |||||

| Functional disability measure by modified Rankin Scale score 2-5 (non-fatal) | Relative risk 0.90 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.01). Based on data from 9690 patients in two studies.† Follow-up 90 days | 142/1000 | 128/1000 | Moderate: due to serious imprecision‡ | Dual antiplatelet therapy possibly has a small but important benefit on patient function |

| Difference: 14 fewer per 1000 (95% CI 27 fewer to 1 more) | |||||

| Poor quality of life measured by EQ-5D index score of ≤0.5 | Relative risk 0.81 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.01). Based on data from 5131 patients in one study¶ | 68/1000 | 55/1000 | Moderate: due to serious imprecision‡ | Dual antiplatelet therapy probably has a s mall important benefit on quality of life |

| Difference: 13 fewer per 1000 (95% CI 23 fewer to 1 more) | |||||

| Recurrent TIA | Relative risk 0.90 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.14). Based on data from 9916 patients in two studies.† Follow-up 90 days | 40/1000 | 36/1000 | Moderate: due to serious imprecision‡ | Dual antiplatelet therapy probably has little or no impact on recurrent TIA |

| Difference: 4 fewer per 1000 (95% CI 12 fewer to 6 more) | |||||

| Mild or minor extracranial bleeding events | Relative risk 2.22 (95% CI 1.60 to 3.08). Based on data from 10 075 patients in three studies* | 6/1000 | 13/1000 | High | Dual antiplatelet therapy results in a small and possibly important increase in mild extracranial bleeding |

| Difference: 7 more per 1000 (95% CI 4 more to 12 more) | |||||

Systematic review with included studies: POINT 2018, FASTER 2007, CHANCE 2013 Baseline/comparator: POINT 2018.

Systematic review with included studies: POINT 2018, CHANCE 2013 Baseline/comparator: POINT 2018

Imprecision: Serious. Wide confidence intervals;

Risk of bias: Serious. POINT was stopped earlier than scheduled, resulting in potential for overestimating benefits. Imprecision: confidence interval includes a small reduction in risk and a large relative increase.

Systematic review with included studies: CHANCE 2013 Baseline/comparator: Control arm of reference used for intervention.

Non-fatal recurrent stroke combines results from three studies including 10 301 patients9 10 20 that reported the incidence of non-fatal ischaemic stroke (0.69, 0.60 to 0.79, I2=0%, absolute reduction 2.0%, high quality evidence) (appendix 2, figs 3 and 4) and three studies including 10 301 patients that reported symptomatic non-fatal intracranial haemorrhage (1.27, 0.55 to 2.89, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) (appendix 2, fig 5). Ischaemic stroke dominated all stroke events and was more common than haemorrhagic stroke (total of 786 ischaemic strokes, 23 haemorrhagic strokes).

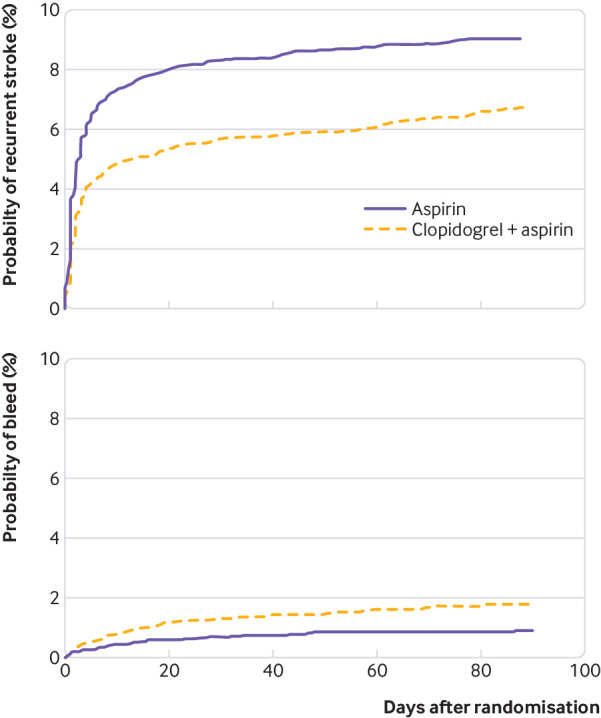

Incidence curves from the CHANCE and POINT studies were consistent in showing that most strokes occurred within 10 days of randomisation. Moreover, visual inspection suggested that the dual and single therapy arms had separated entirely by 10 days; the curves appeared parallel thereafter.

All cause mortality

Two studies including 9690 patients9 20 reported all cause mortality. Pooled analysis showed little apparent effect on all cause mortality, with confidence intervals that included both an appreciable decrease and an appreciable increase (1.27, 0.73 to 2.23, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) (table 2, appendix 2, fig 6).

Major or moderate non-fatal extracranial haemorrhage

Studies differed in their definition of major bleeding (appendix 3). Three studies reported in four articles9 10 20 31 including 10 075 patients reported on major (POINT) or severe or moderate (CHANCE and FASTER) extracranial haemorrhage (we combined severe and moderate bleeding categories into major bleeding for these two trials). Pooled analysis showed that dual antiplatelet therapy is likely to increase the risk of moderate or major extracranial haemorrhage (1.71, 0.92 to 3.20, I2=32%, absolute risk increases 0.2%, moderate quality evidence) (table 2, appendix 2, fig 7).

Other outcomes

Two studies presented in three reports9 20 32 including 9690 patients reported functional outcomes measure by the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), defining disability as an mRS score of 2 or more, and an mRS score of 6 representing death. We derived non-fatal functional disability data by subtracting total mortality from proportion with mRS scores of 2-6. Pooled analysis suggested a small impact of dual antiplatelet therapy on disability (0.90, 0.81 to 1.01, I2=7%, moderate quality evidence (table 2, appendix 2, fig 8).

One study presented in three reports9 32 33 and including 5131 patients, reported quality of life measure by EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), defining poor quality of life as an EQ-5D index score of 0.5 or less and high risk TIA. The study also found that the proportion of poor quality of life was slightly lower in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy than those receiving aspirin alone (0.81, 0.66 to 1.01), and this was moderate quality evidence (table 2).

Two studies including 9916 patients9 20 reported on recurrent TIA. Pooled analysis suggested little impact of dual antiplatelet therapy on TIA, with wide confidence intervals (0.90, 0.71 to 1.14, I2=0%, moderate quality evidence) (table 2, appendix 2, fig 9).

Three studies including 10 075 patients9 10 20 reported mild bleeding. Pooled analysis showed that dual antiplatelet therapy increased the risk of mild or minor extracranial bleeding (2.22, 1.60 to 3.08, I2=18%, absolute risk increases 0.7%, high quality evidence) (table 2, appendix 2, figs 10 and 11).

Myocardial infarction

Two studies including 9690 patients9 20 reported on myocardial infarction. Pooled analysis provided wide, essentially non-informative, confidence intervals (1.45, 0.62 to 3.38, I2=0%, low quality evidence) (appendix 2, fig 12).

Recurrent stroke (fatal and non-fatal)

Three studies including 10 301 patients9 10 20 reported all recurrent stroke (fatal or non-fatal). Pooled analysis showed that dual antiplatelet therapy reduced the risk of all recurrent stroke (0.71, 0.63 to 0.82, I2=0%) (appendix 2, figs 13 and 14).

The sensitivity analysis considering the missing data among these studies did not appreciably change the results in any case.

Effect by stroke subtypes

Although description of subtypes of stroke was not comprehensively detailed in all three studies, the presentation makes clear that each included a mix of small and large vessel disease (appendix 3). Furthermore, only CHANCE conducted a subgroup analysis addressing intracranial large vessel stenosis (versus those without intracranial large vessel stenosis), which failed to suggest any difference in effect between the two (appendix 3). In FASTER, the authors documented the distribution of stroke type as cardioembolic (6.6%), lacunar (28.8%), large artery (24.0%), unknown (36.7%), and other (1.3%) (appendix 3).

Timing of discontinuation of clopidogrel

Figure 3 shows the pooled Kaplan-Meier curves for ischaemic stroke and moderate or major bleeding for patients randomised to dual antiplatelet therapy or aspirin. The stroke rates in the dual antiplatelet therapy and aspirin groups diverge rapidly after day 1. They continue to diverge until day 10. Before day 10, they continue essentially in parallel, with little or no incremental benefit with dual antiplatelet therapy. Appendix 4, figure 1, illustrates this further through separate Kaplan-Meier curves up to days 10, 11 to 21, and 22 to 90, These show that almost all, if not all, of the benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy in reducing the risk of stroke occurs in the first 10 days (2% absolute stroke reduction, odds ratio 0.64, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 0.76).; there is no appreciable additional benefit in days 22 to 90 (1.47, 0.84 to 2.56).

Fig 3.

Pooled Kaplan-Meier time-to-event curves for stroke and bleeding

In contrast, the Kaplan-Meier curve for bleeding (fig 3) shows divergence beginning from randomisation, with the curves continuing to separate to day 90. Thus, while the benefit is restricted to the first 21 days, and possibly the first 10 days, the harm continues to accrue thereafter with continued clopidogrel use.

Discussion

Our review summarises high quality evidence that in patients with minor ischaemic stroke or high risk transient ischaemic attack (TIA), clopidogrel and aspirin used within 24 hours of the event reduces the risk of subsequent stroke over a 30 to 90 day period (relative risk reduction 30%, absolute risk reduction 1.9%, table 2) without an apparent impact on all cause mortality (table 2). Although dual antiplatelet therapy may increase the risk of haemorrhagic stroke, recurrent ischaemic stroke is more common (786 v 23 events), resulting in a clear net benefit on recurrent stroke.

Dual antiplatelet therapy likely increases moderate or serious extracranial bleeding, but these events were much less common than recurrent ischaemic stroke (best estimate of increase in bleeding 0.2%) (table 2). The results provide high quality evidence of an increase in minor bleeding with dual antiplatelet therapy, but the absolute effect is small (increase of 0.7%) and this outcome is far less important than a recurrent stroke. Results suggest that the impact of dual antiplatelet therapy on TIA, myocardial infarction, or functional status is limited or absent.

Most of the benefit in terms of strokes prevented with dual antiplatelet therapy occurs within the first 10 days after stroke; evidence strongly suggests no important reduction—and likely no reduction at all—after 21 days (fig 3, table 3). However, dual antiplatelet therapy consistently increases the risk of bleeding for the duration that patients receive treatment (fig 3, table 3).

Table 3.

GRADE evidence profile: Dual antiplatelet with clopidogrel and aspirin for 10-21 days versus 22-90 days after transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or minor stroke

| Outcome; timeframe | Study results and measurements | Absolute effect estimates | Certainty in effect estimates (quality of evidence) | Plain text summary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop clopidogrel, continue aspirin | Continue clopidogrel and aspirin | ||||

| Ischaemic stroke; 90 days | Odds ratio 1.47 (95% CI 0.84 to 2.56). Based on data from 4406 patients in one study. Follow-up 90 days | 10/1000 | 14/1000 | Moderate: due to indirectness* | Longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy probably does not result in an important reduction in ischaemic stroke |

| Difference: 4 more per 1000 (95% CI 2 fewer to 11 more) | |||||

| Moderate or severe bleeding; 90 days | Odds ratio 2.20 (95% CI 0.83 to 5.78). Based on data from 4599 patients in one study. Follow-up 90 days | 3/1000 | 6/1000 | High: downgraded due to imprecision and upgraded due to a dose-response gradient † | Longer duration of dual antiplatelet therapy increases risk of moderate or major bleeding by small amount |

| Difference: 3 more per 1000 (95% CI 1 fewer to 7 more) | |||||

Indirectness: serious. Patients were randomised 21 days before decision point of whether to stop clopidogrel or not, and patients who had a stroke within the first 21 days were not included in this analysis. More patients randomised to aspirin had a stroke before day 21. Therefore, patients who continued clopidogrel and aspirin were probably at higher risk of a stroke after day 21.

Imprecision: serious. Confidence interval includes no difference.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Strengths of this review include a comprehensive search for randomised, placebo controlled trials; explicit eligibility criteria with a focus on populations most likely to benefit from dual antiplatelet therapy; assessment of risk of bias; provision of important data not included in there published reports provided by the authors of the two large studies; use of the GRADE approach to determine our certainty in the evidence; and an innovative approach to creating a single incidence curve that informs the optimal duration for continuing clopidogrel from the two large studies. The consistent results across studies, and the clear benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy on recurrent stroke without evidence of important adverse effects, is likely to provide clear guidance for patients with high risk TIA and minor ischaemic stroke and for the clinicians responsible for their care.

Our study has some limitations. The loading dose and treatment onset time differed among the three studies: CHANCE and FASTER used a smaller loading dose of clopidogrel compared with POINT (300 mg v 600 mg) (table 1). This could leave clinicians with uncertainty as to which loading dose to choose. Our review does not address other populations of potential interest, including those who have experienced low risk TIA and those with moderate to severe ischaemic stroke.

No trial compared clopidogrel with dual antiplatelet therapy and the addition of aspirin. It is possible that different categories of ischaemic stroke subtypes—small vessel disease, large vessel stenosis, and cryptogenic—will respond differently to the addition of aspirin, and the net benefit of adding clopidogrel will therefore differ. The three trials did not address this issue in detail—to the extent they did, they failed to document convincing evidence of different subgroup effects according to different types of stroke. All three studies, however, enrolled populations heterogeneous for aetiology and excluded major cardioembolic causes with an indication for oral anticoagulant therapy, and the net benefit of adding clopidogrel across these heterogeneous population is clear.

Our review has important strengths compared with previous reviews.22 34 35 36 37 We focused on a specific population, used the GRADE approach to establish quality of evidence, chose an analytical strategy that clearly separated mortal and morbid events, obtained data from authors that allowed implementation of this plan, and conducted an innovative analysis that documented the duration of intervention effects. Most importantly, we included the recent POINT study conducted in heterogeneous Western populations with its striking replication of the previous Chinese CHANCE study.

Meaning of the study

The evidence summarised in our review has important implications for the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. The CHANCE trial continued dual antiplatelet therapy for 21 days; the other trials for 90 days. The incidence curves from both CHANCE and POINT are striking in that they show that most stroke events occurred in the first seven days. Furthermore, separation of the incidence curves in the treatment and control groups happened within the first 10 days, with the curves thereafter essentially parallel (fig 3, table 3).

The failure of dual antiplatelet therapy to provide benefit beyond the first three weeks after treatment initiation is generally consistent with results from other studies examining the commencement of dual antiplatelet therapy substantially later than the first three days.12 13 38 These include the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) study, a randomised multicentre trial involving 3020 patients who failed to find a benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy but did show an increase in adverse events.12

Conclusion

Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin given within 24 hours after high risk TIA or minor ischaemic stroke reduces the risk of subsequent stroke by about 2%, with few serious adverse consequences. Discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy as early as 10 days, and no later than 21 days, after initiation is likely to maximise its net benefit.

These data provide direct evidence on the effect of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin for patients who have experienced high risk TIA or minor ischaemic stroke. The findings of this research paper raise questions about how the dual antiplatelet therapy should be used in clinical practice. In the linked article readers will find recommendations on the use of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin for patients with high risk TIA or minor ischaemic stroke based on data from this paper. To do this a guideline panel has considered how direct this evidence is and using GRADE methodology has integrated this with for example the values and preferences of patients and resource implications. To read more about the guidelines please see the guideline article in this package.

What is already known on this topic

Current guidelines for the management of acute ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack recommend antiplatelet therapy

These guidelines typically provide strong recommendations for use of a single agent, most commonly aspirin

What this study adds

Pooled data from three trials including more than 10 000 patients established a benefit of dual antiplatelet therapy started within 24 hours of presentation in reducing the absolute risk of recurrent stroke by about 2%

Serious extracranial bleeding in this setting is uncommon, and any increase with dual antiplatelet therapy is likely to be small

Stopping clopidogrel within 21 days, and possibly within 10 days, is likely to maintain the full benefits of dual antiplatelet therapy while minimising harms

Linked articles in this BMJ Rapid Recommendations cluster

-

Education article: Prasad K, Siemieniuk R, Hao Q, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for acute high risk transient ischaemic attack and minor ischaemic stroke: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ 2018;363:k5130.

Summary of the results from the Rapid Recommendation process

-

MAGICapp version: MAGICapp (www.magicapp.org/public/guideline/nyq1Yn)

Expanded version of the results with multilayered recommendations, evidence summaries, and decision aids for use on all devices

Acknowledgments

We thank Claiborne Johnston (Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin) and Yongjun Wang and Yuesong Pan (Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Beijing, China) for providing additional data from the POINT and CHANCE trials, respectivel; Rachel Couban, librarian at McMaster university, for designing and executing the search strategy; and members of the Rapid Recommendations panel for critical feedback on the inclusion of relevant outcomes and for their review of this manuscript.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary appendix 1: Search strategies and results

Supplementary appendix 2: Forest plots and sensitivity analysis

Supplementary appendix 3: Definition of bleeding events and stroke subtypes in the three included trials

Supplementary appendix 4: Adequate duration of therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy

Contributors: GHG conceived the study. QH and MT designed the search strategy and screened studies for eligibility. QH, MT, MOD, and GHG assessed study risk of bias and the quality of the body of evidence. QH, FF, and RS wrote the first draft of the manuscript and conducted data analysis. MT, MOD, and GHG interpreted the data analysis and critically revised the manuscript. QH and GHG are the guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The manuscript’s guarantors (GHG and QH) affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the recommendation being reported; that no important aspects of the recommendation have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the recommendation as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1. Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Monteiro Tavares L, et al. TIAregistry.org Investigators Five-Year Risk of Stroke after TIA or Minor Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2182-90. 10.1056/NEJMoa1802712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khare S. Risk factors of transient ischemic attack: An overview. J Midlife Health 2016;7:2-7. 10.4103/0976-7800.179166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71-86. 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160-236. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke. Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. American Academy of Neurology Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Circulation 2006;113:e409-49. 10.1161/circ.113.10.e409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42:227-76. 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181f7d043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lansberg MG, O’Donnell MJ, Khatri P, et al. Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141(Suppl):e601S-36S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2018;49:e46-110. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. CHANCE Investigators Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013;369:11-9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM, FASTER Investigators Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:961-9. 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. CHARISMA Investigators Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1706-17. 10.1056/NEJMoa060989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Benavente OR, Hart RG, McClure LA, Szychowski JM, Coffey CS, Pearce LA, SPS3 Investigators Effects of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with recent lacunar stroke. N Engl J Med 2012;367:817-25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. MATCH investigators Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:331-7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, et al. CHANCE Investigators Clopidogrel With Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) Trial: One-Year Outcomes. Circulation 2015;132:40-6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Koziol K, Van der Merwe V, Yakiwchuk E, Kosar L. Dual antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention: Use of clopidogrel and acetylsalicylic acid after noncardioembolic ischemic stroke. Can Fam Physician 2016;62:640-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bowen AMJ, Gavin Y, eds. National clinical guideline for stroke. 5th ed 2016, www.strokeaudit.org/Guideline/Guideline-Home.aspx2018.07. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bang OY. Considerations When Subtyping Ischemic Stroke in Asian Patients. J Clin Neurol 2016;12:129-36. 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim BJ, Kim JS. Ischemic stroke subtype classification: an asian viewpoint. J Stroke 2014;16:8-17. 10.5853/jos.2014.16.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hankey GJ. Dual antiplatelet therapy in acute transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. N Engl J Med 2013;369:82-3. 10.1056/NEJMe1305127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA. N Engl J Med 2018;379:215-25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siemieniuk RA, Agoritsas T, Macdonald H, Guyatt GH, Brandt L, Vandvik PO. Introduction to BMJ Rapid Recommendations. BMJ 2016;354:i5191. 10.1136/bmj.i5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong KS, Wang Y, Leng X, et al. Early dual versus mono antiplatelet therapy for acute non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2013;128:1656-66. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon H. Guyatt JWB. Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials 2016. http://growthevidence.com/gordon-h-guyatt-md-msc-and-jason-w-busse-dc-phd/ accessed 2018.06.

- 24. Chang Y, Kennedy SA, Bhandari M, et al. Effects of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Patients with Open Fracture of the Extremities: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. JBJS Rev 2015;3:01874474-201503060-00002. 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.N.00088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Spencer FA, Lopes LC, Kennedy SA, Guyatt G. Systematic review of percutaneous closure versus medical therapy in patients with cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004282. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JPT. GSe. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- 27. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA. N Engl J Med 2018;379:215-25. 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, Welton NJ. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:9. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guyatt GH, Ebrahim S, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guidelines 17: assessing the risk of bias associated with missing participant outcome data in a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;87:14-22. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Santesso N, et al. GRADE guidelines: 12. Preparing summary of findings tables-binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:158-72. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang D, Gui L, Dong Y, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy may increase the risk of non-intracranial haemorrhage in patients with minor strokes: a subgroup analysis of the CHANCE trial. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2016;1:29-36. 10.1136/svn-2016-000008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang X, Zhao X, Johnston SC, et al. CHANCE investigators Effect of clopidogrel with aspirin on functional outcome in TIA or minor stroke: CHANCE substudy. Neurology 2015;85:573-9. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang YL, Pan YS, Zhao XQ, et al. CHANCE investigators Recurrent stroke was associated with poor quality of life in patients with transient ischemic attack or minor stroke: finding from the CHANCE trial. CNS Neurosci Ther 2014;20:1029-35. 10.1111/cns.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang Y, Li M, Li JY, et al. The efficacy and adverse reaction of bleeding of clopidogrel plus aspirin as compared to aspirin alone after stroke or TIA: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e65754. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Y, Fei Z, Wang W, Fang J, Zou M, Cheng G. Efficacy and safety of short-term dual- versus mono-antiplatelet therapy in patients with ischemic stroke or TIA: a meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials. J Neurol 2016;263:2247-59. 10.1007/s00415-016-8260-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ding L, Peng B. Efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy in the elderly for stroke prevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2018;25:1276-84. 10.1111/ene.13695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palacio S, Hart RG, Pearce LA, et al. Effect of addition of clopidogrel to aspirin on stroke incidence: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Stroke 2015;10:686-91. 10.1111/ijs.12050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. PRoFESS Study Group Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1238-51. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary appendix 1: Search strategies and results

Supplementary appendix 2: Forest plots and sensitivity analysis

Supplementary appendix 3: Definition of bleeding events and stroke subtypes in the three included trials

Supplementary appendix 4: Adequate duration of therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy