Abstract

The genus Cercospora includes many important plant pathogens that are commonly associated with leaf spot diseases on a wide range of cultivated and wild plant species. Due to the lack of useful morphological features and high levels of intraspecific variation, host plant association has long been a decisive criterion for species delimitation in Cercospora. Because several taxa have broader host ranges, reliance on host data in Cercospora taxonomy has proven problematic. Recent studies have revealed multi-gene DNA sequence data to be highly informative for species identification in Cercospora, especially when used in a concatenated alignment. In spite of this approach, however, several species complexes remained unresolved as no single gene proved informative enough to act as DNA barcoding locus for the genus. Therefore, the aims of the present study were firstly to improve species delimitation in the genus Cercospora by testing additional genes and primers on a broad set of species, and secondly to find the best DNA barcoding gene(s) for species delimitation. Novel primers were developed for tub2 and rpb2 to supplement previously published primers for these loci. To this end, 145 Cercospora isolates from the Iranian mycobiota together with 25 additional reference isolates preserved in the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute were subjected to an eight-gene (ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2 and gapdh) analysis. Results from this study provided new insights into DNA barcoding in Cercospora, and revealed gapdh to be a promising gene for species delimitation when supplemented with cmdA, tef1 and tub2. The robust eight-gene phylogeny revealed several novel clades within the existing Cercospora species complexes, such as C. apii, C. armoraciae, C. beticola, C. cf. flagellaris and Cercospora sp. G. The C. apii s. lat. isolates are distributed over three clades, namely C. apii s. str., C. plantaginis and C. uwebrauniana sp. nov. The C. armoraciae s. lat. isolates are distributed over two clades, C. armoraciae s. str. and C. bizzozeriana. The C. beticola s. lat. isolates are distributed over two clades, namely C. beticola s. str. and C. gamsiana, which is newly described.

Keywords: Bar codes, biodiversity, Cercospora apii complex, host specificity, multi-gene phylogeny, new taxa

INTRODUCTION

Fungi belonging to the genus Cercospora (Mycosphaerellaceae, Capnodiales) are common etiological agents of leaf spots, but some also cause necrotic lesions on flowers, fruits, bracts, seeds and pedicels of many woody and herbaceous plants in a range of climates worldwide (Ellis 1976, Crous & Braun 2003, Agrios 2005, Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a).

Cercospora is a species-rich genus of cercosporoid fungi that was established by Fresenius (1863) for passalora-like species with pluriseptate conidia. During the course of the next 100 years, the concept of Cercospora had been continuously widened (Saccardo 1880, Solheim 1930) and all kinds of superficially similar species, with or without conspicuous conidiogenous loci, with hyaline or pigmented conidia, formed singly or in chains, were assigned to this genus (Braun et al. 2013). In 1954, the genus was monographed by Chupp (1954), who treated 1419 Cercospora species while applying this broad generic concept. He also stated that species of Cercospora were generally host-specific and used this argument as the basis of formulating the concept that each plant host genus or family would have its own Cercospora species. The number of Cercospora species increased rapidly to more than 3000, which led Pollack (1987) to publish her annotated list of Cercospora names. Since the introduction of the genus, several attempts to split Cercospora s. lat. into smaller generic units have been made by applying a combination of characters such as conidiomatal structure, mycelium, conidiophores, conidiogenous cells, and conidia (e.g. Deighton 1973, 1979, 1983, Ellis 1971, 1976, Braun 1995, 1998). Crous & Braun (2003) published an annotated list of the names published in Cercospora and Passalora and used the structure of conidiogenous loci and hila as well as the absence or presence of pigmentation in conidiophores and conidia in their revision. They recognised 659 names in Cercospora, with a further 281 species names reduced to synonymy with C. apii s. lat., since they were morphologically not or barely distinguishable from C. apii s. str. Braun et al. (2013, 2014, 2015a, b, 2016) published a series of papers in a stepwise approach at plant family level in order to update the monograph of Cercospora and allied genera.

Scientific advances in DNA sequencing and supplementary software to store, share and compare the emerging molecular data have revolutionised the procedures underpinning the discovery and identification of fungal taxa, including the cercosporoid fungi (Crous & Groenewald 2005, Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a, Nguanhom et al. 2015, Guatimosim et al. 2017). Numerous molecular studies of Cercospora species have been conducted based on ITS nrDNA data as well as multi-gene approaches (Stewart et al. 1999, Crous et al. 2000, 2004b, 2009a, b, Goodwin et al. 2001, Tessmann et al. 2001, Pretorius et al. 2003, Groenewald et al. 2005, 2006, 2013, Montenegro-Calderón et al. 2011, Bakhshi et al. 2012b, 2015a, Nguanhom et al. 2015, Soares et al. 2015, Albu et al. 2016, Guatimosim et al. 2017, Guillin et al. 2017). A comprehensive and detailed molecular examination of Cercospora s. str. based on a multi-locus DNA sequence dataset of five genomic loci including the ITS (ITS1, 5.8S nrRNA gene and ITS2), together with parts of four protein coding genes, viz. translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), actin (actA), calmodulin (cmdA) and histone H3 (his3) was conducted by Groenewald et al. (2013). The main conclusion of this study was that C<i>.</i> apii s. lat. could not be confirmed as a plurivorous monophyletic species, and that several lineages originally referred to C. apii s. lat., or considered close to this complex based on morphology (Crous & Braun 2003), were separated as distinct phylogenetic species. Hence, speciation within Cercospora s. str. is more complicated than formerly assumed, and far from being resolved. To date, multi-locus DNA sequence analyses combined with ecology, morphology and cultural characteristics, referred to as the Consolidated Species Concept (Quaedvlieg et al. 2014), proved the most effective method for the delimitation of Cercospora species (Groenewald et al. 2010, 2013).

At a higher taxonomic level, among the genera of cercosporoid fungi, the monophyly of Cercospora s. str. has until recently been tested based on phylogenetic association of taxa with the type species of Cercospora, C. apii (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a, Braun & Crous 2016). Bakhshi et al. (2015b) recovered some cercospora-like isolates from Ammi majus, and in their subsequent multi-gene phylogenetic study (28S nrDNA, ITS, actA, tef1 and his3), elucidated these isolates to represent a new genus, Neocercospora, clustering in a clade in Mycosphaerellaceae apart from Cercospora s. str., suggesting that cercospora-like morphologies are not necessarily part of a single monophyletic genus. This finding led to the conclusion that identification and descriptions of new cercospora-like taxa should be avoided without support of molecular sequence data, not only at species but also at generic level.

Species of Cercospora are known to be widely distributed, occurring on a broad range of plant hosts in many climate zones of Iran (Bakhshi et al. 2012, Hesami et al. 2012, Pirnia et al. 2012), where the biodiversity of the genus has recently received much attention (Bakhshi et al. 2015a, b). The most inclusive study was that of Bakhshi et al. (2015a), who compared 161 Cercospora isolates, recovered from 74 host species from Iran based on DNA sequence data of five genomic loci (ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA and his3), host, cultural, and morphological data, revealing a rich species diversity. However, the problem concerning species delimitation in Cercospora due to the high level of conservation among DNA sequences of commonly used loci, (i.e. ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, and his3), could not be resolved. Furthermore, cryptic clades in several species complexes remained unresolved in the five-gene phylogenetic tree, for example C. apii, C. armoraciae, C. cf. flagellaris, and Cercospora sp. G (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a). Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess three additional potential candidate gene regions including the partial β-tubulin (tub2) gene, part of the second largest subunit of RNA-polymerase II (rpb2) gene, and part of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) gene, in order to firstly generate an eight-gene DNA dataset to resolve cryptic taxa within these species complexes, and secondly to identify the best barcoding gene(s) for species resolution in Cercospora.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Specimens and isolates

A total of 170 strains, including 145 previously identified as Cercospora species in Bakhshi et al. (2015a), as well as 25 other related strains formerly identified by Groenewald et al. (2013), were studied. Isolates used in this study (Table 1) are maintained in the collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands, the working collection of Pedro Crous (CPC; housed at CBS), the culture collection of the Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection (IRAN C), Tehran, Iran, and the culture collection of Tabriz University (CCTU), Tabriz, Iran. Type material of the new species recognized is preserved in the Fungal Herbarium of the Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection (IRAN F).

Table 1.

Collection details and GenBank accession numbers of isolates included in this study. Ex-type isolates and newly generated sequences are highlighted in bold.

| Species | Culture accession number (s)1 | Host | Host Family | Origion | Collector |

GenBank accession numbers2 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | actA | cmdA | his3 | tub2 | rpb2 | gapdh | ||||||

| Cercospora althaeina | CCTU 1028 | Althaea rosea | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Sowme`eh Sara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886394 | KJ886233 | KJ885911 | KJ885750 | KJ886072 | MH496336 | MH511833 | MH496166 |

| CCTU 1001 | Althaea rosea | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886392 | KJ886231 | KJ885909 | KJ885748 | KJ886070 | MH496337 | MH511834 | MH496167 | |

| CCTU 1026 | Althaea rosea | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886393 | KJ886232 | KJ885910 | KJ885749 | KJ886071 | MH496338 | MH511835 | MH496168 | |

| CCTU 1152 | Althaea rosea | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886396 | KJ886235 | KJ885913 | KJ885752 | KJ886074 | MH496339 | MH511836 | MH496169 | |

| CBS 248.67; CPC 5117 (TYPE) | Althaea rosea | Malvaceae | Romania, Fundulea | O. Constantinescu | JX143530 | JX143284 | JX143038 | JX142792 | JX142546 | MH496340 | _ | MH496170 | |

| CCTU 1194; IRAN 2674C | Malva sylvestris | Malvaceae | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Kaleybar | M. Arzanlou | KJ886397 | KJ886236 | KJ885914 | KJ885753 | KJ886075 | MH496341 | MH511837 | MH496171 | |

| CCTU 1071 | Malva sylvestris | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886395 | KJ886234 | KJ885912 | KJ885751 | KJ886073 | MH496342 | MH511838 | MH496172 | |

| Cercospora apii | CBS 116455; CPC 11556 (TYPE) | Apium graveolens | Apiaceae | Germany, Heilbron | K. Schrameyer | AY840519 | AY840486 | AY840450 | AY840417 | AY840384 | MH496343 | _ | MH496173 |

| CBS 536.71; CPC 5087 | Apium graveolens | Apiaceae | Romania, Bucuresti | O. Constantinescu | AY752133 | AY752166 | AY752194 | AY752225 | AY752256 | MH496344 | MH511839 | MH496174 | |

| CCTU 1069 | Cynanchum acutum | Apocynaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886410 | KJ886249 | KJ885927 | KJ885766 | KJ886088 | MH496345 | MH511840 | MH496175 | |

| CCTU 1086; CBS 136037; IRAN 2655C | Cynanchum acutum | Apocynaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886411 | KJ886250 | KJ885928 | KJ885767 | KJ886089 | MH496346 | MH511841 | MH496176 | |

| CCTU 1215 | Cynanchum acutum | Apocynaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886412 | KJ886251 | KJ885929 | KJ885768 | KJ886090 | MH496347 | MH511842 | MH496177 | |

| CCTU 1219; CBS 136155 | Cynanchum acutum | Apocynaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886413 | KJ886252 | KJ885930 | KJ885769 | KJ886091 | MH496348 | MH511843 | MH496178 | |

| CPC 5112 | Molucella laevis | Lamiaceae | New zealand, Auckland | C.F. Hill | DQ233321 | DQ233347 | DQ233373 | DQ233399 | DQ233425 | MH496349 | MH511844 | MH496179 | |

| CBS 110813; CPC 5110; 01-3 | Molucella laevis | Lamiaceae | U.S.A., California | S.T. Koike | AY156918 | DQ233345 | DQ233371 | DQ233397 | DQ233423 | MH496350 | MH511845 | MH496180 | |

| Cercospora armoraciae | CBS 250.67; CPC 5088 (TYPE) | Armoracia rusticana (= A. lapathifolia) | Brassicaceae | Romania, Fundulea | O. Constantinescu | JX143545 | JX143299 | JX143053 | JX142807 | JX142561 | MH496351 | _ | MH496181 |

| Cercospora beticola | CPC 12028 | Beta vulgaris | Chenopodiaceae | Egypt | M. Hasem | DQ233336 | DQ233362 | DQ233388 | DQ233414 | DQ233437 | MH496352 | MH511846 | MH496182 |

| CPC 12029 | Beta vulgaris | Chenopodiaceae | Egypt | M. Hasem | DQ233337 | DQ233363 | DQ233389 | DQ233415 | DQ233438 | MH496353 | MH511847 | MH496183 | |

| CCTU 1135 | Beta vulgaris | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886432 | KJ886271 | KJ885949 | KJ885788 | KJ886110 | MH496354 | MH511848 | MH496184 | |

| CBS 116456; CPC 11557 (TYPE) | Beta vulgaris | Chenopodiaceae | Italy, Ravenna | V. Rossi | AY840527 | AY840494 | AY840458 | AY840425 | AY840392 | MH496355 | KT216555 | MH496185 | |

| CCTU 1057; IRAN 2651C | Chenopodium sp. | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886424 | KJ886263 | KJ885941 | KJ885780 | KJ886102 | MH496356 | MH511849 | MH496186 | |

| CCTU 1065 | Chenopodium sp. | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886425 | KJ886264 | KJ885942 | KJ885781 | KJ886103 | MH496357 | MH511850 | MH496187 | |

| CCTU 1087 | Chenopodium sp. | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886427 | KJ886266 | KJ885944 | KJ885783 | KJ886105 | MH496358 | MH511851 | MH496188 | |

| CCTU 1089; CPC 24911 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886429 | KJ886268 | KJ885946 | KJ885785 | KJ886107 | MH496359 | MH511852 | MH496189 | |

| CCTU 1108 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886430 | KJ886269 | KJ885947 | KJ885786 | KJ886108 | MH496360 | MH511853 | MH496190 | |

| CCTU 1088; CBS 138582 | Sonchus asper | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886428 | KJ886267 | KJ885945 | KJ885784 | KJ886106 | MH496361 | MH511854 | MH496191 | |

| Cercospora bizzozeriana | CCTU 1013 | ? | ? | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Mianeh | M. Torbati | KJ886414 | KJ886253 | KJ885931 | KJ885770 | KJ886092 | MH496362 | MH511855 | MH496192 |

| CCTU 1022; CBS 136028 | ? | ? | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Mianeh | M. Torbati | KJ886415 | KJ886254 | KJ885932 | KJ885771 | KJ886093 | MH496363 | MH511856 | MH496193 | |

| CCTU 1127; CBS 136133 | Capparis spinosa | Capparidaceae | Iran, Khuzestan, Ahvaz | E. Mohammadian | KJ886420 | KJ886259 | KJ885937 | KJ885776 | KJ886098 | MH496364 | MH511857 | MH496194 | |

| CCTU 1117; CBS 136132 | Cardaria draba | Brassicaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886418 | KJ886257 | KJ885935 | KJ885774 | KJ886096 | MH496365 | MH511858 | MH496195 | |

| CCTU 1234 | Cardaria draba | Brassicaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886419 | KJ886258 | KJ885936 | KJ885775 | KJ886097 | MH496366 | MH511859 | MH496196 | |

| CCTU 1107 | ? | ? | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886417 | KJ886256 | KJ885934 | KJ885773 | KJ886095 | MH496367 | MH511860 | MH496197 | |

| CBS 258.67; CPC 5061 (TYPE) | Cardaria draba | Brassicaceae | Romania, Fundulea | O. Constantinescu | JX143546 | JX143300 | JX143054 | JX142808 | JX142562 | MH496368 | _ | MH496198 | |

| CBS 540.71; IMI 161110; CPC 5060 | Cardaria draba | Brassicaceae | Romania, Hagieni | O. Constantinescu | JX143548 | JX143302 | JX143056 | JX142810 | JX142564 | MH496369 | _ | MH496199 | |

| CCTU 1040; CBS 136131 | Tanacetum balsamita | Asteraceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886416 | KJ886255 | KJ885933 | KJ885772 | KJ886094 | MH496370 | MH511861 | MH496200 | |

| Cercospora chenopodii | CCTU 1060; IRAN 2652C | Chenopodium album | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Guilan, Bandar-e Anzali | M. Bakhshi | KJ886438 | KJ886277 | KJ885955 | KJ885794 | KJ886116 | MH496371 | MH511862 | MH496201 |

| CCTU 1163 | Chenopodium album | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Guilan, Lahijan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886440 | KJ886279 | KJ885957 | KJ885796 | KJ886118 | MH496372 | MH511863 | MH496202 | |

| CCTU 1033 | Chenopodium album | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886437 | KJ886276 | KJ885954 | KJ885793 | KJ886115 | MH496373 | MH511864 | MH496203 | |

| Cercospora convolvulicola | CCTU 1083; CBS 136126 (TYPE) | Convolvulus arvensis | Convolvulaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886441 | KJ886280 | KJ885958 | KJ885797 | KJ886119 | MH496374 | MH511865 | MH496204 |

| CCTU 1083.2 | Convolvulus arvensis | Convolvulaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886442 | KJ886281 | KJ885959 | KJ885798 | KJ886120 | MH496375 | MH511866 | MH496205 | |

| Cercospora conyzae-canadensis | CCTU 1008 | Conyza canadensis | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886443 | KJ886282 | KJ885960 | KJ885799 | KJ886121 | MH496376 | MH511867 | MH496206 |

| CCTU 1119; CBS 135978 (TYPE) | Conyza canadensis | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886445 | KJ886284 | KJ885962 | KJ885801 | KJ886123 | MH496377 | MH511868 | MH496207 | |

| CCTU 1105; IRAN 2657C | Conyza canadensis | Asteraceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886444 | KJ886283 | KJ885961 | KJ885800 | KJ886122 | MH496378 | MH511869 | MH496208 | |

| Cercospora cylindracea | CCTU 1016 | Cichorium intybus | Asteraceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886446 | KJ886285 | KJ885963 | KJ885802 | KJ886124 | MH496379 | MH511870 | MH496209 |

| CCTU 1114 | Cichorium intybus | Asteraceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886450 | KJ886289 | KJ885967 | KJ885806 | KJ886128 | MH496380 | MH511871 | MH496210 | |

| CCTU 1081; CBS 138580; IRAN 2654C (TYPE) | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886449 | KJ886288 | KJ885966 | KJ885805 | KJ886127 | MH496381 | MH511872 | MH496211 | |

| CCTU 1207 | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886453 | KJ886292 | KJ885970 | KJ885809 | KJ886131 | MH496382 | MH511873 | MH496212 | |

| CCTU 1044; CBS 136021 | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886447 | KJ886286 | KJ885964 | KJ885803 | KJ886125 | MH496383 | MH511874 | MH496213 | |

| CCTU 1183 | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886451 | KJ886290 | KJ885968 | KJ885807 | KJ886129 | MH496384 | MH511875 | MH496214 | |

| CCTU 1189 | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886452 | KJ886291 | KJ885969 | KJ885808 | KJ886130 | MH496385 | MH511876 | MH496215 | |

| CCTU 1049 | Lactuca serriola | Asteraceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886448 | KJ886287 | KJ885965 | KJ885804 | KJ886126 | MH496386 | MH511877 | MH496216 | |

| Cercospora cf. flagellaris clade 1 | CPC 5441 | Amaranthus sp. | Amaranthaceae | Fiji | C.F. Hill | JX143611 | JX143370 | JX143124 | JX142878 | JX142632 | MH496387 | MH511878 | MH496217 |

| CCTU 1159; CBS 136148 | Arachis hypogaea | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Lahijan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886493 | KJ886332 | KJ886010 | KJ885849 | KJ886171 | MH496388 | MH511879 | MH496218 | |

| CCTU 1162; IRAN 2670C | Citrullus lanatus | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Guilan, Lahijan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886496 | KJ886335 | KJ886013 | KJ885852 | KJ886174 | MH496389 | MH511880 | MH496219 | |

| CBS 132653; CPC 10884 | Dysphania ambrosioides (≡ Chenopodium ambrosioides) | Chenopodiaceae | South Korea, Jeju | H.D. Shin | JX143603 | JX143361 | JX143115 | JX142869 | JX142623 | MH496390 | MH511881 | MH496220 | |

| CCTU 1007; CBS 136031 | Hydrangea sp. | Hydrangeaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886456 | KJ886295 | KJ885973 | KJ885812 | KJ886134 | MH496391 | MH511882 | MH496221 | |

| CCTU 1027; CBS 136034 | Lepidium sativum | Brassicaceae | Iran, Guilan, Chamkhaleh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886459 | KJ886298 | KJ885976 | KJ885815 | KJ886137 | MH496392 | MH511883 | MH496222 | |

| CCTU 1128; CBS 136141; IRAN 2661C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886476 | KJ886315 | KJ885993 | KJ885832 | KJ886154 | MH496393 | MH511884 | MH496223 | |

| CCTU 1168; IRAN 2715C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Kiashahr | M. Bakhshi | KJ886499 | KJ886338 | KJ886016 | KJ885855 | KJ886177 | MH496394 | MH511885 | MH496224 | |

| CPC 1051 | Populus deltoides | Salicaceae | South Africa | P.W. Crous | AY260069 | JX143367 | JX143121 | JX142875 | JX142629 | MH496395 | MH511886 | MH496225 | |

| CCTU 1171 | Raphanus sativus | Brassicaceae | Iran, Guilan, Kiashahr | M. Bakhshi | KJ886500 | KJ886339 | KJ886017 | KJ885856 | KJ886178 | MH496396 | MH511887 | MH496226 | |

| CCTU 1120 | Raphanus sativus | Brassicaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886475 | KJ886314 | KJ885992 | KJ885831 | KJ886153 | MH496397 | MH511888 | MH496227 | |

| CCTU 1031; CBS 136036; IRAN 2648C | Urtica dioica | Urticaceae | Iran, Guilan, Sowme`eh Sara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886461 | KJ886300 | KJ885978 | KJ885817 | KJ886139 | MH496398 | MH511889 | MH496228 | |

| Cercospora cf. flagellaris clade 2 | CCTU 1204 | Abutilon theophrasti | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886505 | KJ886344 | KJ886022 | KJ885861 | KJ886183 | MH496399 | MH511890 | MH496229 |

| CCTU 1198; CBS 136151 | Acer velutinum | Aceraceae | Iran, Mazandaran, Ramsar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886504 | KJ886343 | KJ886021 | KJ885860 | KJ886182 | MH496400 | MH511891 | MH496230 | |

| CBS 132667; CPC 11643 | Celosia argentea var. cristata (≡ C. cristata) | Amaranthaceae | South Korea, Hoengseong | H.D. Shin | JX143604 | JX143362 | JX143116 | JX142870 | JX142624 | MH496401 | MH511892 | MH496231 | |

| CCTU 1115; CBS 136139; IRAN 2659C | Cercis siliquastrum | Caesalpinaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886473 | KJ886312 | KJ885990 | KJ885829 | KJ886151 | MH496402 | MH511893 | MH496232 | |

| CCTU 1195 | Datura stramonium | Solanaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886503 | KJ886342 | KJ886020 | KJ885859 | KJ886181 | MH496403 | MH511894 | MH496233 | |

| CCTU 1059; CBS 136136 | Ecballium elaterium | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886464 | KJ886303 | KJ885981 | KJ885820 | KJ886142 | MH496404 | MH511895 | MH496234 | |

| CCTU 1216; IRAN 2717C | Ecballium elaterium | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886510 | KJ886349 | KJ886027 | KJ885866 | KJ886188 | MH496405 | MH511896 | MH496235 | |

| CCTU 1223; CBS 136154; IRAN 2683C | Eclipta prostrata | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886512 | KJ886351 | KJ886029 | KJ885868 | KJ886190 | MH496406 | MH511897 | MH496236 | |

| CCTU 1068 | Xanthium spinosum | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886466 | KJ886305 | KJ885983 | KJ885822 | KJ886144 | MH496407 | MH511898 | MH496237 | |

| CCTU 1085 | Xanthium strumarium | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886471 | KJ886310 | KJ885988 | KJ885827 | KJ886149 | MH496408 | MH511899 | MH496238 | |

| Cercospora cf. flagellaris clade 3 | CCTU 1172 | Oenothera biennis | Onagraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886501 | KJ886340 | KJ886018 | KJ885857 | KJ886179 | MH496409 | MH511900 | MH496239 |

| CCTU 1154; CBS 136147 | Abutilon theophrasti | Malvaceae | Iran, Guilan, Rasht | M. Bakhshi | KJ886489 | KJ886328 | KJ886006 | KJ885845 | KJ886167 | MH496410 | MH511901 | MH496240 | |

| CCTU 1072; IRAN 2653C | Amaranthus blitoides | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886468 | KJ886307 | KJ885985 | KJ885824 | KJ886146 | MH496411 | MH511902 | MH496241 | |

| CCTU 1064 | Amaranthus retroflexus | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886465 | KJ886304 | KJ885982 | KJ885821 | KJ886143 | MH496412 | MH511903 | MH496242 | |

| CCTU 1021; CBS 136033 | Amaranthus retroflexus | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Guilan, Fuman | M. Bakhshi | KJ886458 | KJ886297 | KJ885975 | KJ885814 | KJ886136 | MH496413 | MH511904 | MH496243 | |

| CCTU 1084; CBS 136156 | Amaranthus sp. | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886470 | KJ886309 | KJ885987 | KJ885826 | KJ886148 | MH496414 | MH511905 | MH496244 | |

| CCTU 1167; CBS 136150 | Anubias sp. | Araceae | Iran, Guilan, Kiashahr | M. Bakhshi | KJ886498 | KJ886337 | KJ886015 | KJ885854 | KJ886176 | MH496415 | MH511906 | MH496245 | |

| CBS 143.51; CPC 5055 | Bromus sp. | Poaceae | — | M.D. Whitehead | JX143607 | JX143365 | JX143119 | JX142873 | JX142627 | MH496416 | MH511907 | MH496246 | |

| CCTU 1150 | Buxus microphylla | Buxaceae | Iran, Guilan, Fuman | M. Bakhshi | KJ886488 | KJ886327 | KJ886005 | KJ885844 | KJ886166 | MH496417 | MH511908 | MH496247 | |

| CCTU 1140; CBS 136143; IRAN 2666C | Calendula officinalis | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886481 | KJ886320 | KJ885998 | KJ885837 | KJ886159 | MH496418 | MH511909 | MH496248 | |

| CBS 115482; A207 Bs+; CPC 4410 | Citrus sp. | Rutaceae | South Africa, Messina | M.C. Pretorius | AY260070 | DQ835095 | DQ835114 | DQ835141 | DQ835168 | MH496419 | MH511910 | MH496249 | |

| CCTU 1029; CBS 136035; IRAN 2647C | Cucurbita maxima | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Guilan, Rudsar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886460 | KJ886299 | KJ885977 | KJ885816 | KJ886138 | MH496420 | MH511911 | MH496250 | |

| CCTU 1136 | Cucurbita pepo | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886478 | KJ886317 | KJ885995 | KJ885834 | KJ886156 | MH496421 | MH511912 | MH496251 | |

| CCTU 1143; CBS 136145 | Datura stramonium | Solanaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886484 | KJ886323 | KJ886001 | KJ885840 | KJ886162 | MH496422 | MH511913 | MH496252 | |

| CCTU 1209; CBS 136152 | Glycine max | Fabaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886506 | KJ886345 | KJ886023 | KJ885862 | KJ886184 | MH496423 | MH511914 | MH496253 | |

| CCTU 1210; IRAN 2679C | Glycine max | Fabaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886507 | KJ886346 | KJ886024 | KJ885863 | KJ886185 | MH496424 | MH511915 | MH496254 | |

| CCTU 1211 | Glycine max | Fabaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886508 | KJ886347 | KJ886025 | KJ885864 | KJ886186 | MH496425 | MH511916 | MH496255 | |

| CCTU 1218; IRAN 2682C | Hibiscus trionum | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886511 | KJ886350 | KJ886028 | KJ885867 | KJ886189 | MH496426 | MH511917 | MH496256 | |

| CCTU 1006; CBS 136030 | Impatiens balsamina | Balsaminaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886455 | KJ886294 | KJ885972 | KJ885811 | KJ886133 | MH496427 | MH511918 | MH496257 | |

| CCTU 1130; CBS 136142 | Olea europaea | Oleaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Torbati | KJ886477 | KJ886316 | KJ885994 | KJ885833 | KJ886155 | MH496428 | MH511919 | MH496258 | |

| CCTU 1010; CBS 136032 | Pelargonium hortorum | Geraniaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886457 | KJ886296 | KJ885974 | KJ885813 | KJ886135 | MH496429 | MH511920 | MH496259 | |

| CCTU 1138; IRAN 2664C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886479 | KJ886318 | KJ885996 | KJ885835 | KJ886157 | MH496430 | MH511921 | MH496260 | |

| CCTU 1139; IRAN 2665C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886480 | KJ886319 | KJ885997 | KJ885836 | KJ886158 | MH496431 | MH511922 | MH496261 | |

| CCTU 1155.11 | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Fuman | M. Bakhshi | KJ886490 | KJ886329 | KJ886007 | KJ885846 | KJ886168 | MH496432 | MH511923 | MH496262 | |

| CCTU 1161; IRAN 2669C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Lahijan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886495 | KJ886334 | KJ886012 | KJ885851 | KJ886173 | MH496433 | MH511924 | MH496263 | |

| CCTU 1175; IRAN 2673C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Sowme`eh Sara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886502 | KJ886341 | KJ886019 | KJ885858 | KJ886180 | MH496434 | MH511925 | MH496264 | |

| CCTU 1142; IRAN 2667C | Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886483 | KJ886322 | KJ886000 | KJ885839 | KJ886161 | MH496435 | MH511926 | MH496265 | |

| CCTU 1118; CBS 136140; IRAN 2660C | Populus deltoides | Salicaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886474 | KJ886313 | KJ885991 | KJ885830 | KJ886152 | MH496436 | MH511927 | MH496266 | |

| CCTU 1075 | Raphanus sativus | Brassicaceae | Iran, Guilan, Sowme`eh Sara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886469 | KJ886308 | KJ885986 | KJ885825 | KJ886147 | MH496437 | MH511928 | MH496267 | |

| CCTU 1212; CBS 136153; IRAN 2680C | Silybum marianum | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886509 | KJ886348 | KJ886026 | KJ885865 | KJ886187 | MH496438 | MH511929 | MH496268 | |

| CCTU 1141; CBS 136144 | Tagetes patula | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Rudsar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886482 | KJ886321 | KJ885999 | KJ885838 | KJ886160 | MH496439 | MH511930 | MH496269 | |

| CCTU 1147 | Urtica dioica | Urticaceae | Iran, Guilan, Masal | M. Bakhshi | KJ886486 | KJ886325 | KJ886003 | KJ885842 | KJ886164 | MH496440 | MH511931 | MH496270 | |

| CCTU 1160; CBS 136149 | Vicia faba | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886494 | KJ886333 | KJ886011 | KJ885850 | KJ886172 | MH496441 | MH511932 | MH496271 | |

| CCTU 1158; IRAN 2668C | Xanthium strumarium | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Langarud | M. Bakhshi | KJ886492 | KJ886331 | KJ886009 | KJ885848 | KJ886170 | MH496442 | MH511933 | MH496272 | |

| CCTU 1156 | Xanthium strumarium | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Rasht | M. Bakhshi | KJ886491 | KJ886330 | KJ886008 | KJ885847 | KJ886169 | MH496443 | MH511934 | MH496273 | |

| CCTU 1005; IRAN 2644C | Xanthium strumarium | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886454 | KJ886293 | KJ885971 | KJ885810 | KJ886132 | MH496444 | MH511935 | MH496274 | |

| CCTU 1048; CBS 136029 | Xanthium strumarium | Asteraceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886462 | KJ886301 | KJ885979 | KJ885818 | KJ886140 | MH496445 | MH511936 | MH496275 | |

| Cercospora gamsiana | CBS 144962; CCTU 1074; CPC 24909 (TYPE) | Malva neglecta | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886426 | KJ886265 | KJ885943 | KJ885782 | KJ886104 | MH496446 | MH511937 | MH496276 |

| CCTU 1035 | Malva sylvestris | Malvaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886423 | KJ886262 | KJ885940 | KJ885779 | KJ886101 | MH496447 | MH511938 | MH496277 | |

| CCTU 1109 | Malva sylvestris | Malvaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886431 | KJ886270 | KJ885948 | KJ885787 | KJ886109 | MH496448 | MH511939 | MH496278 | |

| CCTU 1199; CBS 136128; IRAN 2675C | Rumex crispus | Polygonaceae | Iran, Mazandaran, Ramsar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886433 | KJ886272 | KJ885950 | KJ885789 | KJ886111 | MH496449 | MH511940 | MH496279 | |

| CCTU 1205; CBS 136127; IRAN 2677C | Sesamum indicum | Pedaliaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886435 | KJ886274 | KJ885952 | KJ885791 | KJ886113 | MH496450 | MH511941 | MH496280 | |

| CCTU 1208; IRAN 2678C | Sonchus sp. | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886436 | KJ886275 | KJ885953 | KJ885792 | KJ886114 | MH496451 | MH511942 | MH496281 | |

| Cercospora cf. gossypii | CCTU 1070; CBS 136137 | Gossypium herbaceum | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886467 | KJ886306 | KJ885984 | KJ885823 | KJ886145 | MH496452 | MH511943 | MH496282 |

| CCTU 1055; IRAN 2650C | Hibiscus trionum | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886463 | KJ886302 | KJ885980 | KJ885819 | KJ886141 | MH496453 | MH511944 | MH496283 | |

| Cercospora iranica | CCTU 1196; CBS 136123 | Hydrangea sp. | Hydrangeaceae | Iran, Mazandaran, Ramsar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886515 | KJ886354 | KJ886032 | KJ885871 | KJ886193 | MH496454 | MH511945 | MH496284 |

| CCTU 1137; CBS 136124 (TYPE) | Vicia faba | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886513 | KJ886352 | KJ886030 | KJ885869 | KJ886191 | MH496455 | MH511946 | MH496285 | |

| Cercospora plantaginis | CCTU 1082; CBS 138728 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886402 | KJ886241 | KJ885919 | KJ885758 | KJ886080 | MH496456 | MH511947 | MH496286 |

| CCTU 1095 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Horand | M. Bakhshi | KJ886403 | KJ886242 | KJ885920 | KJ885759 | KJ886081 | MH496457 | MH511948 | MH496287 | |

| CCTU 1041; CPC 24910 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Guilan, Chaboksar | M. Bakhshi | KJ886400 | KJ886239 | KJ885917 | KJ885756 | KJ886078 | MH496458 | MH511949 | MH496288 | |

| CCTU 1179; IRAN 2716C | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886404 | KJ886243 | KJ885921 | KJ885760 | KJ886082 | MH496459 | MH511950 | MH496289 | |

| CCTU 1047 | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886401 | KJ886240 | KJ885918 | KJ885757 | KJ886079 | MH496460 | MH511951 | MH496290 | |

| CBS 252.67; CPC 5084 (TYPE) | Plantago lanceolata | Plantaginaceae | Romania, Domnesti | O. Constantinescu | DQ233318 | DQ233342 | DQ233368 | DQ233394 | DQ233420 | MH496461 | _ | MH496291 | |

| Cercospora pseudochenopodii | CCTU 1176 | Chenopodium album | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886518 | KJ886357 | KJ886035 | KJ885874 | KJ886196 | MH496462 | MH511952 | MH496292 |

| CCTU 1045 | Chenopodium sp. | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886517 | KJ886356 | KJ886034 | KJ885873 | KJ886195 | MH496463 | MH511953 | MH496293 | |

| CCTU 1038; CBS 136022; IRAN 2649C (TYPE) | Chenopodium sp. | Chenopodiaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886516 | KJ886355 | KJ886033 | KJ885872 | KJ886194 | MH496464 | MH511954 | MH496294 | |

| Cercospora cf. richardiicola | CCTU 1004 | Bidens tripartita | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886519 | KJ886358 | KJ886036 | KJ885875 | KJ886197 | MH496465 | MH511955 | MH496295 |

| Cercospora rumicis | CCTU 1123 | Rumex crispus | Polygonaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886521 | KJ886360 | KJ886038 | KJ885877 | KJ886199 | MH496466 | MH511956 | MH496296 |

| CCTU 1129; IRAN 2662C | Rumex crispus | Polygonaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886522 | KJ886361 | KJ886039 | KJ885878 | KJ886200 | MH496467 | MH511957 | MH496297 | |

| CCTU 1121 | Urtica dioica | Urticaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886520 | KJ886359 | KJ886037 | KJ885876 | KJ886198 | MH496468 | MH511958 | MH496298 | |

| Cercospora solani | CCTU 1043; CBS 136038 | Solanum nigrum | Solanaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886523 | KJ886362 | KJ886040 | KJ885879 | KJ886201 | MH496469 | MH511959 | MH496299 |

| CCTU 1050 | Solanum nigrum | Solanaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886524 | KJ886363 | KJ886041 | KJ885880 | KJ886202 | MH496470 | MH511960 | MH496300 | |

| Cercospora sorghicola | CCTU 1173; CBS 136448; IRAN 2672C (TYPE) | Sorghum halepense | Poaceae | Iran, Guilan, Kiashahr | M. Bakhshi | KJ886525 | KJ886364 | KJ886042 | KJ885881 | KJ886203 | MH496471 | MH511961 | MH496301 |

| Cercospora sp. G clade 1 | CCTU 1197 | Bidens tripartita | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886540 | KJ886379 | KJ886057 | KJ885896 | KJ886218 | MH496472 | MH511962 | MH496302 |

| CCTU 1015; CBS 136024; IRAN 2645C | Plantago major | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886528 | KJ886367 | KJ886045 | KJ885884 | KJ886206 | MH496473 | MH511963 | MH496303 | |

| CPC 5438 | Salvia viscosa | Lamiaceae | New Zealand, Manurewa | C.F. Hill | JX143682 | JX143442 | JX143196 | JX142950 | JX142704 | MH496474 | _ | MH496304 | |

| Cercospora sp. G clade 2 | CCTU 1058 | Helminthotheca echioides | Asteraceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886534 | KJ886373 | KJ886051 | KJ885890 | KJ886212 | MH496475 | MH511964 | MH496305 |

| CCTU 1090 | Abutilon theophrasti | Malvaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886536 | KJ886375 | KJ886053 | KJ885892 | KJ886214 | MH496476 | MH511965 | MH496306 | |

| CCTU 1079; CBS 136025 | Amaranthus retroflexus | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886535 | KJ886374 | KJ886052 | KJ885891 | KJ886213 | MH496477 | MH511966 | MH496307 | |

| CCTU 1054 | Amaranthus sp. | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886533 | KJ886372 | KJ886050 | KJ885889 | KJ886211 | MH496478 | MH511967 | MH496308 | |

| CCTU 1122 | Amaranthus sp. | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886538 | KJ886377 | KJ886055 | KJ885894 | KJ886216 | MH496479 | MH511968 | MH496309 | |

| CBS 115518; CPC 5360 | Bidens frondosa | Asteraceae | New Zealand, Kopuku | C.F. Hill | JX143681 | JX143441 | JX143195 | JX142949 | JX142703 | MH496480 | _ | MH496310 | |

| CCTU 1030; CBS 136026 | Bidens tripartita | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886530 | KJ886369 | KJ886047 | KJ885886 | KJ886208 | MH496481 | MH511969 | MH496311 | |

| CCTU 1002 | Celosia cristata | Amaranthaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886527 | KJ886366 | KJ886044 | KJ885883 | KJ886205 | MH496482 | MH511970 | MH496312 | |

| CCTU 1053; CBS 136027 | Cichorium intybus | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Sowme`eh Sara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886532 | KJ886371 | KJ886049 | KJ885888 | KJ886210 | MH496483 | MH511971 | MH496313 | |

| CCTU 1144; CBS 136130 | Cucurbita maxima | Cucurbitaceae | Iran, Guilan, Masal | M. Bakhshi | KJ886539 | KJ886378 | KJ886056 | KJ885895 | KJ886217 | MH496484 | MH511972 | MH496314 | |

| CCTU 1046 | Plantago major | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886531 | KJ886370 | KJ886048 | KJ885887 | KJ886209 | MH496485 | MH511973 | MH496315 | |

| CCTU 1116 | Plantago major | Plantaginaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886537 | KJ886376 | KJ886054 | KJ885893 | KJ886215 | MH496486 | MH511974 | MH496316 | |

| CCTU 1020; CBS 136023 | Sorghum halepense | Poaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886529 | KJ886368 | KJ886046 | KJ885885 | KJ886207 | MH496487 | MH511975 | MH496317 | |

| Cercospora sp. T | CCTU 1148; CBS 136125 | Coreopsis sp. | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Rasht | M. Bakhshi | KJ886541 | KJ886380 | KJ886058 | KJ885897 | KJ886219 | MH496488 | MH511976 | MH496318 |

| Cercospora uwebrauniana | CCTU 1200; CBS 138581 (TYPE) | Heliotropium europaeum | Boraginaceae | Iran, Ardabil, Moghan | M. Bakhshi | KJ886408 | KJ886247 | KJ885925 | KJ885764 | KJ886086 | MH496489 | MH511977 | MH496319 |

| CCTU 1134 | Heliotropium europaeum | Boraginaceae | Iran, Guilan, Astara | M. Bakhshi | KJ886407 | KJ886246 | KJ885924 | KJ885763 | KJ886085 | MH496490 | MH511978 | MH496320 | |

| Cercospora violae | CCTU 1025; IRAN 2646C | Viola sp. | Violaceae | Iran, Mazandaran, Nowshahr | M. Bakhshi | KJ886543 | KJ886382 | KJ886060 | KJ885899 | KJ886221 | MH496491 | MH511979 | MH496321 |

| CBS 251.67; CPC 5079 (TYPE) | Viola tricolor | Violaceae | Romania, Cazanele Dunarii | O. Constantinescu | JX143737 | JX143496 | JX143250 | JX143004 | JX142758 | MH496492 | _ | MH496322 | |

| Cercospora zebrina | CCTU 1039 | Alhagi camelorum | Fabaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886545 | KJ886384 | KJ886062 | KJ885901 | KJ886223 | MH496493 | MH511980 | MH496323 |

| CBS 108.22; CPC 5091 | Medicago arabica (= M. maculata) | Fabaceae | — | E.F. Hopkins | JX143744 | JX143503 | JX143257 | JX143011 | JX142765 | MH496494 | _ | MH496324 | |

| CCTU 1225 | Medicago sativa | Fabaceae | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Marand | M. Bakhshi | KJ886550 | KJ886389 | KJ886067 | KJ885906 | KJ886228 | MH496495 | MH511981 | MH496325 | |

| CCTU 1180 | Medicago sativa | Fabaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886547 | KJ886386 | KJ886064 | KJ885903 | KJ886225 | MH496496 | MH511982 | MH496326 | |

| CCTU 1110; IRAN 2658C | Medicago sativa | Fabaceae | Iran, Zanjan, Tarom | M. Bakhshi | KJ886546 | KJ886385 | KJ886063 | KJ885902 | KJ886224 | MH496497 | MH511983 | MH496327 | |

| CCTU 1012; CBS 136129 | Medicago sp. | Fabaceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886544 | KJ886383 | KJ886061 | KJ885900 | KJ886222 | MH496498 | MH511984 | MH496328 | |

| CCTU 1181 | Trifolium repens | Fabaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886548 | KJ886387 | KJ886065 | KJ885904 | KJ886226 | MH496499 | MH511985 | MH496329 | |

| CBS 113070; CPC 5367 | Trifolium repens | Fabaceae | New Zealand, Blockhouse Bay | C.F. Hill | JX143745 | JX143507 | JX143261 | JX143015 | JX142769 | MH496500 | _ | MH496330 | |

| CBS 118790; IMI 262766; WA 2030; WAC 7973 | Trifolium subterraneum | Fabaceae | Australia | M.J. Barbetti | JX143748 | JX143510 | JX143264 | JX143018 | JX142772 | MH496501 | _ | MH496331 | |

| CBS 129.39; CPC 5078 | Trifolium subterraneum | Fabaceae | U.S.A., Wisconsin | — | JX143750 | JX143512 | JX143266 | JX143020 | JX142774 | MH496502 | _ | MH496332 | |

| CCTU 1185 | Vicia sp. | Fabaceae | Iran, West Azerbaijan, Khoy | M. Arzanlou | KJ886549 | KJ886388 | KJ886066 | KJ885905 | KJ886227 | MH496503 | MH511986 | MH496333 | |

| CCTU 1239; CBS 135977 | Vitis vinifera | Vitaceae | Iran, East Azerbaijan, Kaleybar | M. Arzanlou | KJ886551 | KJ886390 | KJ886068 | KJ885907 | KJ886229 | MH496504 | MH511987 | MH496334 | |

| Cercospora cf. zinniae | CCTU 1003 | Zinnia elegans | Asteraceae | Iran, Guilan, Talesh | M. Bakhshi | KJ886552 | KJ886391 | KJ886069 | KJ885908 | KJ886230 | MH496505 | MH511988 | MH496335 |

1CBS: Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CCTU: Culture Collection of Tabriz University, Tabriz, Iran; CPC: Culture collection of Pedro Crous, housed at CBS; IMI: International Mycological Institute, CABI-Bioscience, Egham, Bakeham Lane, U.K.; IRAN: Iranian Fungal Culture Collection, Iranian Research Institute of Plant Protection, Tehran, Iran; WAC: Department of Agriculture Western Australia Plant Pathogen Collection, Perth, Australia.

2ITS: internal transcribed spacers and intervening 5.8S nrDNA; tef1: partial translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene, actA: partial actin gene, cmdA: partial calmodulin gene, his3: partial histone H3 gene, tub2: partial beta-tubulin gene, rpb2: partial RNA polymerase II gene, gapdh: partial glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

DNA samples comprised those previously extracted by Bakhshi et al. (2015a) and Groenewald et al. (2013). Three additional partial nuclear genes were targeted for PCR amplification and sequencing, namely, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh), RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2), and β-tubulin (tub2), using corresponding primer sets (Table 2). PCR amplifications were performed in a total volume of 12.5 μL on a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The gapdh PCR mixture consisted of 5–10 ng genomic DNA, 1 × PCR buffer (Bioline, London), 2 mM MgCl2 (Bioline), 50 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 μL BSA (10 mg/ml) (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.28 μM of each primer and 0.5 units GoTaq® Flexi DNA polymerase (Promega). The tub2 PCR mixture contained 5–10 ng genomic DNA, 1 × PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 40 μM of each dNTP, 0 μL / 0.5 μL BSA, 0.25 μM of each primer and 0.5 units GoTaq® Flexi DNA polymerase using respectively the BT-1F/BT-1R (this study) or T1 (O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997)/β-Sandy-R (Stukenbrock et al. 2012) primer sets. The rpb2 gene was amplified in three parts with three primer sets. Part three was only amplified in some selected species in order to design a new reverse primer for amplification of part two. The rpb2 PCR mixtures using the fRPB2-5F (Liu et al. 1999)/fRPB2-414R (Quaedvlieg et al. 2011) primer set consisted of 5–10 ng genomic DNA, 1 × PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 40 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 μL BSA, 0.2 μM of each primer and 0.5 units GoTaq® Flexi DNA polymerase. The PCR mixtures using RPB2-C5F/RPB2-C8R (this study) and fRPB2-7cF/fRPB2-11aR primer sets (Liu et al. 1999) were the same as gapdh.

Table 2.

Primer combinations used during this study for amplification and sequencing.

| Locus | Primer | Primer sequence 5’ to 3’ | Annealing temperature (°C) | Orientation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-tubulin (tub2) | T1 | AAC ATG CGT GAG ATT GTA AGT | 48 | Forward | O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997 |

| β-Sandy-R | GCR CGN GGV ACR TAC TTG TT | 48 | Reverse | Stukenbrock et al. 2012 | |

| BT-1F | GTC CWC ACC GCC CCT GAT | 56 | Forward | This study | |

| BT-1R | CTT GTT RCC RGA AGC CTR TGS | 56 | Reverse | This study | |

| RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (rpb2) | fRPB2-5F | GAY GAY MGW GAT CAY TTY GG | 47 | Forward | Liu et al. 1999 |

| fRPB2-414R | ACM ANN CCC CAR TGN GWR TTR TG | 47 | Reverse | Quaedvlieg et al. 2011 | |

| fRPB2-7cF | ATG GGY AAR CAA GCY ATG GG | 49 | Forward | Liu et al. 1999 | |

| fRPB2-11aR | GCR TGG ATC TTR TCR TCS ACC | 49 | Reverse | Liu et al. 1999 | |

| RPB2-C5F | TGG GGA GAY CAR AAR AAA GC | 60→58→56 | Forward | This study | |

| RPB2-C8R | ACG GAA TCT TCC TGG TTG TA | 60→58→56 | Reverse | This study | |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (gapdh) | Gpd1-LM | ATT GGC CGC ATC GTC TTC CGC AA | 60→58→53 | Forward | Myllys et al. 2002 |

| Gpd2-LM | CCC ACT CGT TGT CGT ACC A | 60→58→53 | Reverse | Myllys et al. 2002 |

To obtain the partial tub2 and rpb2 (using the fRPB2-5F/fRPB2-414R and fRPB2-7cF/fRPB2-11aR primer sets) sequences, PCR amplification conditions were set as follows: an initial denaturation temperature of 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 (tub2) or 45 (rpb2) cycles of denaturation temperature of 94 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at the temperature stipulated in Table 2 for 30 s, primer extension at 72 °C for 45 s and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min.

A touchdown PCR protocol was used to amplify the partial gapdh (using the Gpd1-LM/Gpd2-LM primer set (Myllys et al. 2002)) and rpb2 (using the RPB2-C5F/RPB2-C8R primer set) sequences: initial denaturation (94 °C, 5 min), five amplification cycles (94 °C, 45 s; 60 °C, 45 s; 72 °C, 90 s), five amplification cycles (94 °C, 45 s; 58 °C, 45 s; 72 °C, 90 s), 30 amplification cycles (94 °C, 45 s; 53 °C (gapdh) or 56 °C (rpb2), 45 s; 72 °C, 90 s) and a final extension step (72 °C, 5 min). PCR products were visualised by electrophoresis using a 1.2 % agarose gel, stained with GelRed<sup>TM</sup> (Biotium, Hayward, CA) and viewed under ultra-violet light. Size estimates were made using a HyperLadder<sup>TM</sup> I molecular marker (Bioline).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

The resulting PCR fragments were sequenced in both directions using the same primers used for amplification (Table 2) and the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. DNA sequencing amplicons were purified through Sephadex G-50 Superfine columns (SigmaAldrich, St Louis, MO) in 96-well MultiScreen HV plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA) as outlined by the manufacturer and analysed with an ABI Prism 3730xl Automated DNA analyser (Life Technologies Europe BV, Applied Biosystems<sup>TM</sup>, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands).

The raw DNA sequences of tub2, gapdh and rpb2 were edited using MEGA v. 6 (Tamura et al. 2013) and forward and reverse sequences for each isolate were assembled manually to generate consensus sequences. Two parts of the rpb2 gene (part amplified with the fRPB2-5F/fRPB2-414R primer set + part amplified with the RPB2-C5F/RPB2-C8R primer set) were compiled manually using MEGA v. 6. The assembled consensus sequences were initially aligned with MEGA v. 6 and optimised with the multiple sequence alignment online interface of MAFFT using default settings (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) (Katoh & Standley 2013), and adjusted manually where necessary. In addition, sequences of the same isolates corresponding to the ITS locus (including ITS1, 5.8S, ITS2), together with parts of four protein coding genes, viz. translation elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1), actin (actA), calmodulin (cmdA) and histone H3 (his3), were retrieved from the NCBIs GenBank nucleotide database and included in the analyses, after separate alignment as described above. Sequences of Cercospora sorghicola (CBS 136448 = IRAN 2672C) were used as outgroup. Evolutionary models for phylogenetic analyses were selected independently for each locus using MrModeltest v. 2.3 (Nylander 2004) under the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Table 3). The individual alignments of the different loci were subsequently concatenated with Mesquite v. 2.75 (Maddison & Maddison 2011) prior to being subjected to a combined multi-gene analysis. Given the different sizes of the data partitions, they could not be properly used in statistical tests for (in)congruency. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using Bayesian inference (BI) Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm in MrBayes v. 3.2.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012). Two simultaneous MCMC analyses, each consisting of four Markov chains, were run from random trees until the average standard deviation of split frequencies reached a value of 0.01, with trees saved every 100 generations and the heating parameter was set to 0.15. Burn-in phase was set to 25 % and the posterior probabilities (Rannala & Yang 1996) were calculated from the remaining trees. The resulting phylogenetic tree was generated with Geneious v. 5.6.7 (Drummond et al. 2012).

Table 3.

Phylogenetic data and the substitution models used in the phylogenetic analysis, per locus. Abbreviations of loci follow Table 1.

| Locus | ITS | tef1 | actA | cmdA | his3 | tub2 | rpb2 | gapdh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of characters | 470 | 291 | 187 | 248 | 358 | 415 | 1229 | 869 |

| Unique site patterns | 16 | 75 | 48 | 66 | 63 | 105 | 259 | 231 |

| Substitution model used | SYM-gamma | K80-gamma | K80-gamma | K80-gamma | HKY-gamma | GTR-gamma | GTR-gamma | GTR-I-gamma |

| Number of generations (n) | 2 405 000 | |||||||

| Total number of trees (n) | 4 812 | |||||||

| Sampled trees (n) | 3 610 | |||||||

All new sequences generated in this study were deposited in NCBIs GenBank nucleotide database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; Table 1) and the alignment and phylogenetic trees in TreeBASE S22944 (www.TreeBASE.org).

Morphology

Morphological descriptions are based on structures from dried material. Diseased leaf tissues were viewed under a Nikon® SMZ1500 stereo-microscope and taxonomically informative morphological structures (stromata, conidiophores and conidia) were picked up from lesions with a sterile dissecting needle and mounted on glass slides in clear lactic acid. Structures were examined under a Nikon Eclipse 80i light microscope, and photographed using a mounted Nikon digital sight DS-f1 high definition colour camera.

Thirty measurements were made at ×1000 for each microscopic structure, and 95 % conӿdence intervals were derived for the measurements with extreme values given in parentheses. Colony macro-morphology on MEA was determined after 1 mo at 25 °C in the dark in duplicate and colony colour was described using the mycological colour charts of Rayner (1970). Nomenclatural novelties and descriptions were deposited in MycoBank (www.mycobank.org; Crous et al. 2004). The naming system for tentatively applied names used by Groenewald et al. (2013) and Bakhshi et al. (2015a) is continued in this manuscript to simplify comparison between the studies.

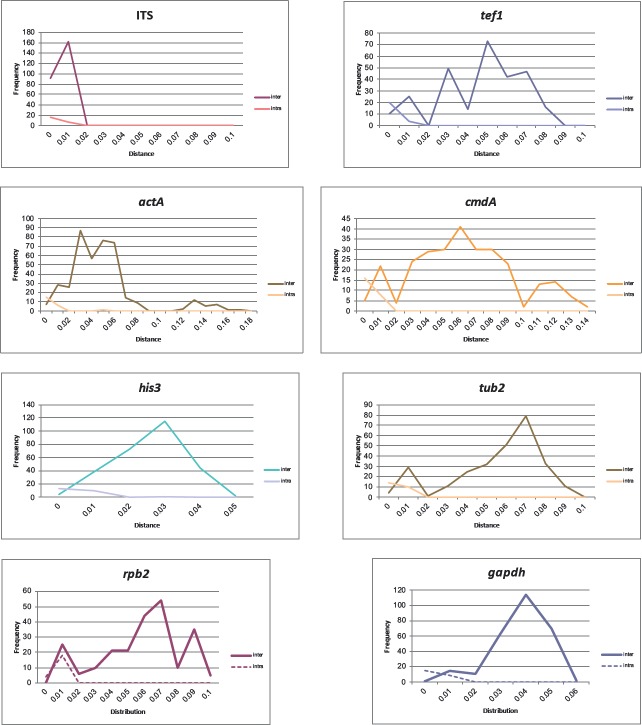

Identification of the best-performing DNA barcode

The dataset of the eight loci, ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2 and gapdh, was individually tested for two factors: Kimura-2-parameter (K2P) values (barcode gap) and molecular phylogenetic resolution (clade recovery). Inter- and intraspecific distances of eight loci were calculated for each single-locus sequence data alignment, using MEGA v. 6.0 with the Kimura-2-parameter distance values using the pairwise deletion model. Microsoft Excel 2010 was subsequently used to sort these distance values into distribution bins (from distance 0–0.1 with intervals of 0.01 between bins) and the frequency of entries for each individual bin was then plotted against the Kimura-2-parameter distance of each bin.

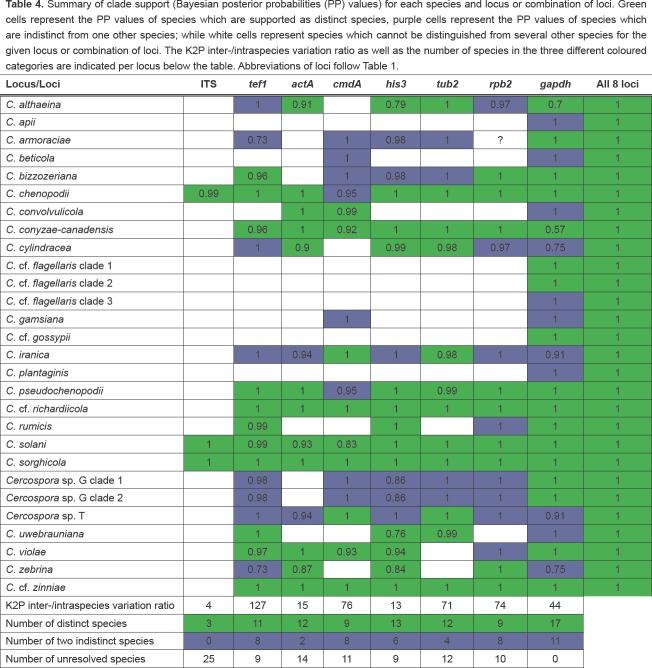

In addition, Bayesian analyses using the corresponding nucleotide substitution models (Table 3) were applied to each data partition to check the stability and robustness of each species clade (clade recovery) under the different loci (data not shown, trees deposited in TreeBASE S22944) (Table 4). The clade recovery and Kimura-2-parameter values for each locus were calculated after applying the consolidated species concept to the results of eight-gene phylogenetic tree.

Table 4.

Summary of clade support (Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) values) for each species and locus or combination of loci. Green cells represent the PP values of species which are supported as distinct species, purple cells represent the PP values of species which are indistinct from one other species; while white cells represent species which cannot be distinguished from several other species for the given locus or combination of loci. The K2P inter-/intraspecies variation ratio as well as the number of species in the three different coloured categories are indicated per locus below the table. Abbreviations of loci follow Table 1.

Allele group designation

The isolates in each of the Cercospora species complexes, including C. apii, C. armoraciae, C. beticola, C. cf. flagellaris, and Cercospora sp. G, were compared using the individual alignments of the eight single loci in MEGA v. 6. Allele groups were established for each locus based on sequence identity, i.e. each sequence with one or more nucleotide difference from the other sequence was regarded as a different allele.

RESULTS

DNA amplification and phylogenetic analysis

New primers were designed for rpb2 and tub2 in this study (Table 2) and proved to be effective for the selected Cercospora species. Approximately 400, 1000, and 1200 bp were obtained for tub2, gapdh and rpb2 loci, respectively. The final concatenated eight-locus alignment contained 169 ingroup taxa and a total of 4 099 characters including alignment gaps were processed. The gene boundaries were 1–470 bp for ITS, 475–765 bp for tef1, 770–956 bp for actA, 961–1 208 bp for cmdA, 1 213–1 570 bp for his3, 1 575–1 989 bp for tub2, 1 994–3 222 bp for rpb2, and 3 227–4 099 bp for gapdh. For the total alignment, 28 characters which were artificially introduced as spacers to separate the loci, were excluded from the phylogenetic analyses. The alignment contained 863 unique site patterns (Table 3).

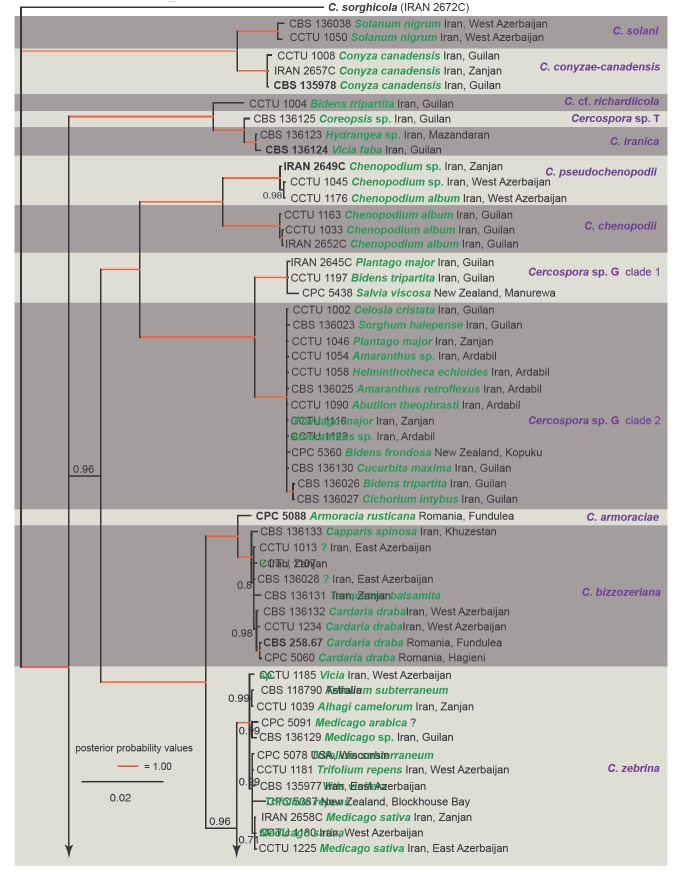

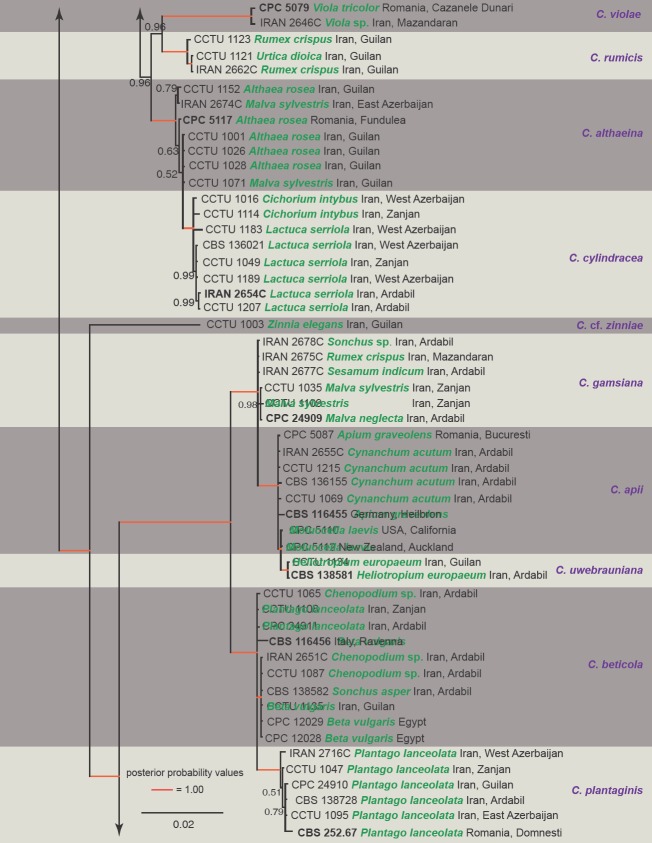

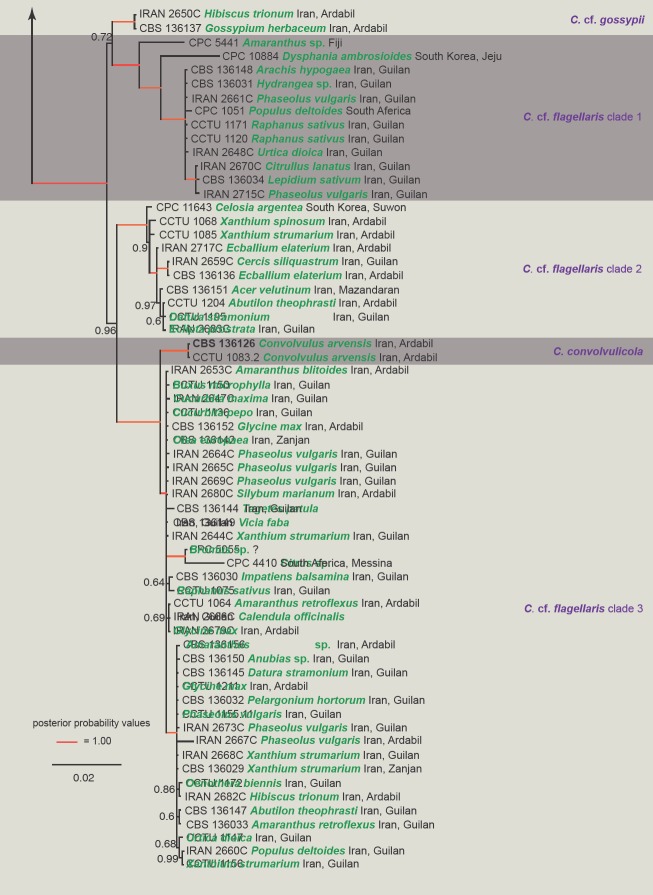

The Bayesian analysis lasted 2 405 000 generations and generated 4 812 trees from which the first 1 202 trees (25 %), representing the burn-in phase of the analyses, were discarded, and the remaining trees (3 610) were used for calculating posterior probabilities (PP) values in the phylogenetic tree (50 % majority rule consensus tree) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consensus phylogram (50 % majority rule) of 3 610 trees resulting from a Bayesian analysis of the combined eight-gene sequence alignment using MrBayes v. 3.2.2. The scale bar indicates 0.02 expected changes per site. Hosts and country of origin are indicated in green and black text, respectively. The tree was rooted to Cercospora sorghicola (isolate CBS 136448 = IRAN 2672C).

TAXONOMY

Species delimitation in the genus Cercospora in this study follows the Consolidated Species Concept accepted in recent revisions of the taxonomy of cercosporoid fungi (e.g. Groenewald et al. 2013, Crous et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a, Videira et al. 2017). Twenty-eight lineages of Cercospora were resolved based on the clustering and support in the Bayesian tree obtained from the combined ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2, and gapdh alignment (Fig. 1, Table 4). Of these, 15 species including C. althaeina, C. chenopodii, C. convolvulicola, C. conyzae-canadensis, C. cylindracea, C. iranica, C. pseudochenopodii, C. cf. richardiicola, C. rumicis, C. solani, C. sorghicola, Cercospora sp. T, C. violae, C. zebrina, and C. cf. zinnia, were the same as those also accepted before in the five-gene phylogenetic tree (ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, and his3) (Bakhshi et al. 2015a). However, the eight-gene phylogenetic tree separated strains previously recognised as C. apii, C. armoraciae, C. beticola, C. cf. flagellaris, and Cercospora sp. G, based on five-gene phylogenetic tree (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a) into at least three, two, two, four and two well-supported clades respectively (Fig. 1). Some of these clades are supported by the host range or morphological characters of the isolates and are therefore described as new below.

Cercospora apii complex

The 16 isolates previously recognised as C. apii based on five-gene phylogenetic tree (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a) are assigned here to three lineages based on the eight-gene phylogenetic tree, host association, and morphology, including C. apii s. str., C. uwebrauniana sp. nov., and C. plantaginis (Fig. 1, part 2). The results of allele group designation for the isolates in this complex detected one, four, two, two, four, three, four and two allele groups for the ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2, and gapdh sequences, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results from allele group designation per locus for Cercospora apii s. lat. isolates in this study. Abbreviations of loci and collection accession numbers follow Table 1.

| Species | Culture accession number | Host |

Allele group per locus |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | actA | cmdA | his3 | tub2 | rpb2 | gapdh | |||

| C. apii s. str. | CCTU 1069 | Cynanchum acutum | I | II | I | I | II | I | IV | I |

| CCTU 1086; CBS 136037; IRAN 2655C | Cynanchum acutum | I | II | I | I | II | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1215 | Cynanchum acutum | I | II | I | I | II | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1219; CBS 136155 | Cynanchum acutum | I | II | I | I | II | I | II | I | |

| CBS 536.71; CPC 5087 | Apium graveolens | I | II | I | I | II | I | I | I | |

| CBS 116455; CPC 11556 (TYPE) | Apium graveolens | I | I | I | I | I | I | _ | I | |

| CBS 110813; CPC 5110 | Molucella laevis | I | II | I | II | II | I | I | I | |

| CPC 5112 | Molucella laevis | I | II | I | II | II | I | I | I | |

| C. plantaginis | CCTU 1041; CPC 24910 | Plantago lanceolata | I | II | I | II | III | I | I | II |

| CCTU 1047 | Plantago lanceolata | I | II | I | II | II | II | I | II | |

| CCTU 1082; CBS 138728 | Plantago lanceolata | I | II | I | II | III | II | I | II | |

| CCTU 1095 | Plantago lanceolata | I | II | I | II | III | II | I | II | |

| CCTU 1179 | Plantago lanceolata | I | II | II | II | II | I | III | II | |

| CBS 252.67; CPC 5084 (TYPE) | Plantago lanceolata | I | III | II | II | III | II | _ | II | |

| C. uwebrauniana | CCTU 1134 | Heliotropium europaeum | I | IV | I | II | IV | III | I | I |

| CCTU 1200; CBS 138581 (TYPE) | Heliotropium europaeum | I | IV | I | II | IV | III | I | I | |

Cercospora apiiFresen., Beitr. Mykol. 3: 91 (1863).

Sensu Groenewald et al., Phytopathology 95: 954 (2005).

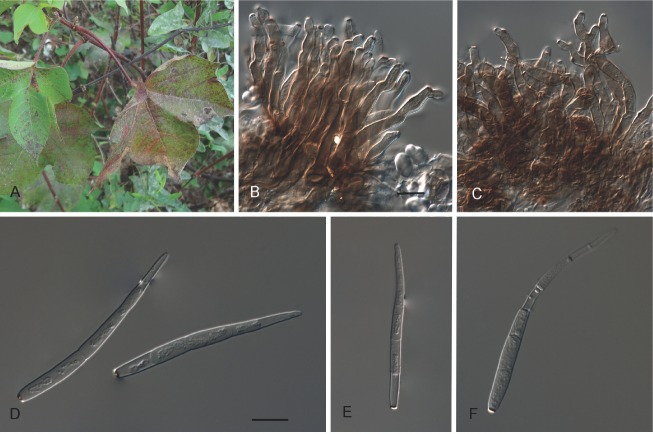

(Fig. 2)

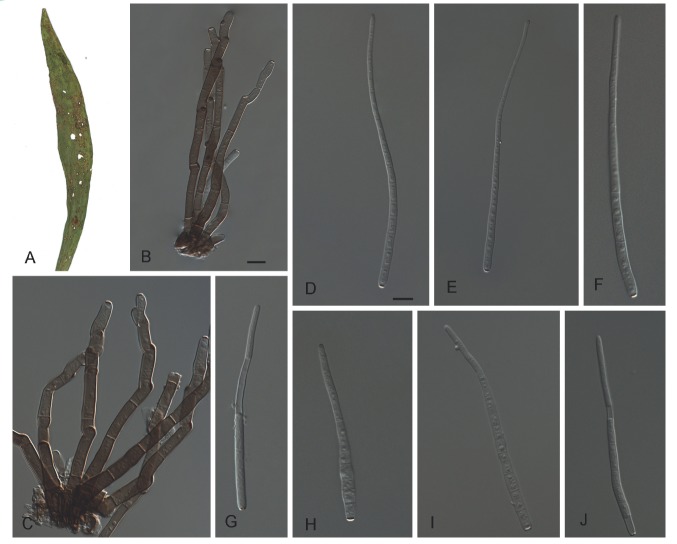

Fig. 2.

Cercospora apii (CBS 136037). A.Leaf spots. B–C. Fasciculate conidiophores. D–H.Conidia. Bars = 10 μm.

Type: Germany: Oestrich, on Apium graveolens (Apiaceae), Fuckel, Fungi rhen. 117, in HAL (lectotype designated by Groenewald et al. 2005); Heilbronn, Landwirtschaftsamt, on A. graveolens, 10 Aug. 2004, K. Schrameyer (CBS 116455 = CPC 11556 – epitype designated by Groenewald et al. 2005).

Description: Leaf spots amphigenous, distinct, circular to subcircular, 1–9 mm diam, white-grey in centre, surrounded by a dark purple-brown border. Mycelium internal. Caespituli amphigenous, brown. Conidiophores aggregated in moderately dense fascicles (4–15), arising from the upper cells of a well-developed brown stroma, to 50 μm wide; conidiophores brown, becoming pale brown towards the apex, 1−6-septate, straight to variously curved, unbranched, uniform in wide, (45−)80–95(−125) × 4–5.5 μm. Conidiogenous cells integrated, lateral or terminal, unbranched, brown, smooth, proliferating sympodially, 20–40 × 3.5–5 μm, multi-local; loci thickened, darkened, refractive, apical or lateral, 2–3.5 μm diam. Conidia solitary, smooth, obclavate-cylindrical to acicular, straight to slightly curved, hyaline, distinctly 3–9(−15)-septate, apex subacute or subobtusely rounded, base subtruncate to obconically truncate, (30–)65–80(−115) × 3–5 μm; hila thickened, darkened, refractive, 2–3.5 μm diam.

Note: This clade includes the ex-epitype strain of C. apii (isolate CBS 116455 = CPC 11556), therefore we fixed the application of C. apii s. str. to this clade.

Specimens examined: Germany: Heilbron, Landwirtschaftsamt, on A. graveolens, K. Schrameyer (CBS 116455 = CPC 11556 −ex-epitype culture). – Iran: Ardabil Province: Moghan, on leaves of Cynanchum acutum (Apocynaceae), Oct. 2011, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17016F, IRAN 17017F, CCTU 1069, CCTU 1086 = IRAN 2655C = CBS 136037); Moghan, on leaves of C. acutum, Oct. 2012, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17018F, IRAN 17019F, CCTU 1215, CCTU 1219 = CBS 136155). – New Zealand: Auckland, on M. laevis, C.F. Hill (CPC 5112). – Romania: Bucuresti, on A. graveolens, 2 Oct. 1969, O. Constantinescu (CBS 536.71 = CPC 5087). – USA: California: on Moluccella laevis (Lamiaceae), S.T. Koike (CBS 110813 = CPC 5110).

Cercospora plantaginisSacc., Michelia 1: 267 (1878).

(Fig. 3)

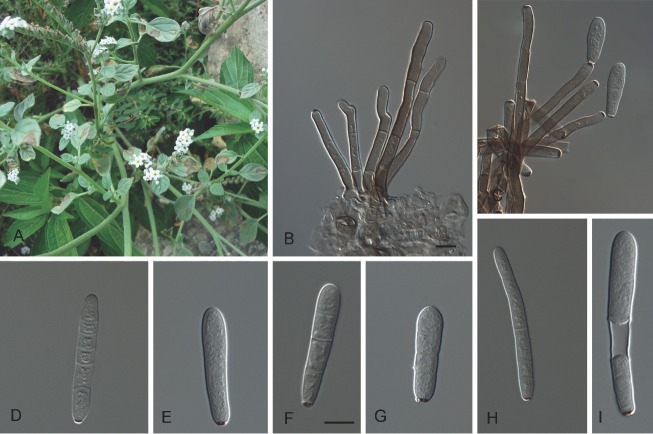

Fig. 3.

Cercospora plantaginis (CPC 24910). A.Leaf spots. B–C.Fasciculate conidiophores. D–J. Conidia. Bars = 10 μm.

Type: Italy: Selva, on Plantago lanceolata (Plantaginaceae), Sep. 1873, P.A. Saccardo (PAD, s.n. – holotype, according to Art. 9.1, Note 1). – Romania: Domnesti, on P. lanceolata, 3 Aug. 1965, O. Constantinescu (CBS 252.67 – epitype designated here, MBT 383093, preserved as a metabolically inactive culture).

Description: Leaf spots amphigenous, circular to subcircular, 1–4 mm diam, white to grey with distinct raised brown borders. Mycelium internal. Caespituli amphigenous, brown. Conidiophores aggregated in loose fascicles, arising from a moderately developed, intraepidermal and substomatal, dark brown stroma, to 30 μm diam; conidiophores brown at the base, becoming paler towards the apex, 2–10-septate, straight to geniculate-sinuous due to sympodial proliferation, simple, uniform in width, somewhat constricted at the proliferating point, (45−)60–85 × 4–5 μm. Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal or lateral, pale brown to brown, proliferating sympodially, 8–25 × 3.5–5 μm, multi-local; loci distinctly thickened, darkened and somewhat refractive, apical or formed on shoulders caused by sympodial proliferation, 2–3 μm diam. Conidia solitary, subcylindrical, filiform to acicular, straight to mildly curved, hyaline, (40−)60–70(−105) × 2–3.5 μm, (4−)8–13(−17)-septate, with subobtuse to subacute apices and truncate bases; hila thickened, darkened, refractive, 1.5–2.5 μm diam.

Notes: Based on the results of the eight-gene phylogenetic tree, all isolates obtained from P. lanceolata from five different provinces in Iran together with a European isolate from this host plant, previously recognised as C. apii based on a five-gene phylogenetic tree (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a), cluster separately from the other isolates in this clade (Fig. 1, part 2). Three species of Cercospora, including C. apii, C. pantoleuca and C. plantaginis, have been reported from Plantago (Crous & Braun 2003, https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/). This species is morphologically close to C. plantaginis described from Italy on P. lanceolata (Chupp 1954). Since one European isolate from P. lanceolata in Romania (CBS 252.67 = CPC 5084) also resides in this clade, we designate an epitype here for this species, and fix the application of the name C. plantaginis to this clade.

Additional specimens examined: Iran: Guilan Province: Chaboksar, on P. lanceolata, Jul. 2012, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17076F, CCTU 1041 = CPC 24910). Zanjan Province: Tarom, Pasar, on P. lanceolata, Sep. 2011, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17078F, CCTU 1047). Ardabil Province: Moghan, on P. lanceolata, Sep. 2011, M. Bakhshi (CCTU 1082 = CBS 138728). East Azerbaijan Province: Arasbaran, Horand, on P. lanceolata, Oct. 2011, M. Bakhshi (CCTU 1095). West Azerbaijan Province: Khoy, Firouragh, on P. lanceolata, Sep. 2012, M. Arzanlou (IRAN 17077F, CCTU 1179 = IRAN 2716C).

Cercospora uwebrauniana M. Bakhshi & Crous, sp. nov.

MycoBank MB827521

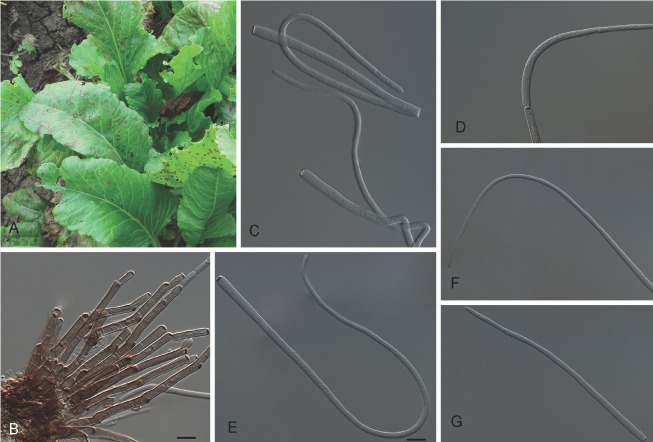

(Fig. 4)

Fig. 4.

Cercospora uwebrauniana (CBS 138581). A. Leaf spots. B–C. Fasciculate conidiophores. D–I. Conidia. Bars = 10 μm.

Etymology: Named in honour of Uwe Braun, who has published extensively on the genus Cercospora, and also provided a modern treatment for allied genera of Mycosphaerellaceae.

Diagnosis: Differs from C. taurica in the cylindrical conidia with truncate or subtruncate bases and somewhat shorter and wider conidia, (23−)38–48(−70) × 4.5–8 μm vs 40–110 × (2.5−)4–6(−7) μm in C. taurica.

Type: Iran: Ardabil Province: Moghan, on Heliotropium europaeum (Boraginaceae), Oct. 2012, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 16864F – holotype; CCTU 1200 = CBS 138581 – ex-type culture).

Description: Leaf spots distinct, circular to irregular, 3–10 mm, grey-brown to dark brown, surrounded by brown margin. Mycelium internal. Caespituli amphigenous, brown. Conidiophores in moderately dense fascicles, arising from the upper cells of a moderately developed, intraepidermal and substomatal, brown stroma, to 40 μm wide; conidiophores straight to slightly geniculate, pale brown to brown, unbranched, regular in width, (60−)115–145(−230) × 3.5–5.5 μm, 2–9-septate. Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal, brown, proliferating sympodially, 15–35 × 3.5–5.5 μm, mostly mono-local, sometimes multi-local; loci distinctly thickened, darkened, refractive, apical or formed on the shoulders caused by geniculation, 2–3.5 μm. Conidia solitary, hyaline, subcylindrical to cylindrical, straight or slightly curved, truncate to subtruncate at the base, obtuse to rounded at the apex, (23−)38–48(−70) × 4.5–8 μm, (0−)3–4(−9)-septate; hila thickened, darkened, refractive, 1.5–3 μm diam.

Notes: Two isolates, obtained from H. europaeum in different provinces in Iran, clustered in a small clade within C. apii s. str. (Fig. 1, part 2). This independent clade is supported by tef1, his3 and tub2 from C. apii s. str. Morphologically, these two strains are completely distinct from their most closely related species in the phylogenetic tree, namely C. apii (conidia acicular, subacute or subobtusely rounded at the apex, (30−)65–80(−115) × 3–5 μm), C. beticola (conidia subacute to acute apex, (40−)90–140(−300) × 2–5 μm), C. gamsiana (conidia subobtuse at the apex, (27−)49–62(−100) × 2–4 μm) and C. plantaginis (conidia subobtuse to subacute apices, (40−)60–70(−105) × 2–3.5 μm), by the obtuse to rounded apex, wider and shorter conidia ((23−)38–48(−70) × 4.5–8 μm), and are regarded as a separate species, appearing to be confined to H. europaeum.

Presently, three species of Cercospora have been described from Heliotropium, C. apii, C. heliotropiicola, and C. taurica (Crous & Braun 2003, https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/). Cercospora uwebrauniana differs from C. taurica in the cylindrical conidia with truncate or subtruncate bases and somewhat shorter and wider conidia, (23−)38–48(−70) × 4.5–8 μm vs 40–110 × (2.5−)4–6(−7) μm in C. taurica (Braun 2002). In addition, C. taurica has obclavate-cylindrical conidia with obconically truncate bases and rather wider conidiophores, 4–9 μm diam (Braun 2002). Cercospora heliotropiicola is morphologically quite distinct from C. uwebrauniana in having acicular or subulate, much thinner (2–3 μm wide) and longer (to 300 μm long) conidia with subobtuse or acute apex (Pons & Sutton 1996).

Additional specimen examined: Iran: Guilan Province: Astara, on H. europaeum, Jun. 2012, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17096F, CCTU 1134).

Cercospora armoraciae complex

The 10 isolates previously recognised as C. armoraciae based on a five-gene phylogenetic tree (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a) are assigned to two lineages here, based on the eight-gene phylogenetic tree, including C. armoraciae s. str. and C. bizzozeriana (Fig. 1, part 1). The results of allele group designation for the isolates in this complex revealed one, three, one, two, seven, three, three and two allele groups for the ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2 and gapdh sequences, respectively (Table 6).

Table 6.

Results from allele group designation per locus for Cercospora armoraciae s. lat. isolates in this study. Abbreviations of loci and collection accession numbers follow Table 1.

| Species | Culture accession number | Host |

Allele group per locus |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | actA | cmdA | his3 | tub2 | rpb2 | gapdh | |||

| C. armoraciae s. str. | CBS 250.67; CPC 5088 (TYPE) | Armoracia rusticana (= A. lapathifolia) | I | I | I | I | I | I | _ | II |

| C. bizzozeriana | CCTU 1013 | ? | I | II | I | I | III | I | I | I |

| CCTU 1022; CBS 136028 | ? | I | II | I | I | III | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1040; CBS 136131 | Tanacetum balsamita | I | III | I | II | VI | I | II | I | |

| CCTU 1107 | ? | I | II | I | I | VII | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1117; CBS 136132 | Cardaria draba | I | II | I | I | V | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1234 | Cardaria draba | I | II | I | I | V | III | I | I | |

| CCTU 1127; CBS 136133 | Capparis spinosa | I | II | I | I | IV | II | III | I | |

| CBS 540.71; CPC 5060 | Cardaria draba | I | II | I | I | II | I | _ | I | |

| CBS 258.67; CPC 5061 (TYPE) | Cardaria draba | I | II | I | I | II | I | _ | I | |

Cercospora armoraciae Sacc., Nuovo Giorn. Bot. Ital. 8: 188 (1876).

Note: This clade includes the ex-type culture of C. armoraciae (CBS 250.67).

Cercospora bizzozeriana Sacc. & Berl., Malpighia 2: 248 (1888).

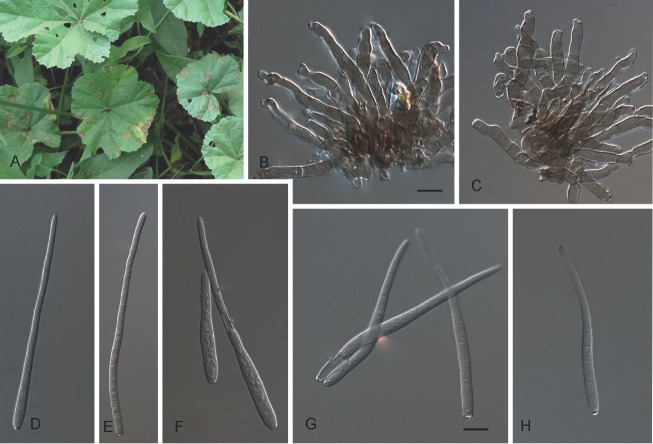

(Fig. 5)

Fig. 5.

Cercospora bizzozeriana (CBS 136132). A–B. Leaf spots. C. Fasciculate conidiophores. D–J. Conidia. Bars = 10 μm.

Type: Italy: Padova, on Lepidium latifolium (Brassicaceae), (Berlese, Malpighia 1: tab. XIV, fig. 23, 1887 – lectotype, designated here, MBT 383343); Romania: Fundulea, on Cardaria draba, isol. by O. Constantinescu [deposited in the CBS culture collection in 1967] (CBS 258.67 – epitype designated here, MBT 383154, preserved as a metabolically inactive culture).

Notes: Type material of C. bizzozeriana is not preserved in Saccardo's herbarium (see Gola 1930). Therefore, the original illustration published by Saccardo & Berlese (in Berlese 1888) is designated as lectotype (according to Art. 9.3 and 9.4). Berlese's article “Fungi veneti novi vel critici” was split into several parts published in Malpighia 1 (1887) and 2 (1888). The description of C. bizzozeriana was published in vol 2, but with reference to tab. XIV, fig. 23 already issued in vol. 1.

Description: Leaf spots amphigenous, circular, 1–5 mm, white to white-grey with grey to black dots (stroma with conidiophores) and definite brown border. Mycelium internal. Caespituli amphigenous, brown. Conidiophores aggregated in dense fascicles, arising from a well-developed, brown stroma, to 75 μm diam; conidiophores brown, 1–5-septate, straight to geniculate-sinuous due to sympodial proliferation, simple, sometimes branched, uniform in width, sometimes constricted at the proliferating point, (30−)50–60(−80) × 4–7 μm. Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal or lateral, pale brown to brown, proliferating sympodially, 10–25 × 3–6 μm, multi-local; loci distinctly thickened, darkened and somewhat refractive, apical, lateral or formed on shoulders caused by geniculation, 1.5–3 μm diam. Conidia solitary, obclavate-cylindrical, straight to slightly curved, hyaline, (20−)60–80(−125) × 3–6 μm, 2–10-septate, with obtuse apices and subtruncate or obconically truncate bases; hila thickened, darkened, refractive, 1.5–3 μm diam.

Notes: Isolates obtained from different host species including Tanacetum balsamita, Capparis spinosa and Cardaria draba clustered in a clade distinct from the ex-type isolate of C. armoraciae, and are regarded as a separate taxon. In addition, five isolates obtained from Car. draba (three from Iran and two from Romania) all cluster in this clade. Until now, three species of Cercospora are known from these host species, including C. bizzozeriana, C. chrysanthemi and C. capparis (Crous & Braun 2003, https://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/). Cercospora chrysanthemi is in the C. apii s. lat. complex (Crous & Braun 2003). Cercospora capparis differs from this species by the narrower (4–5.5 μm diam) conidiophores and 3–5 μm diam conidia (Chupp 1954). The species is morphologically close to C. bizzozeriana which was described from Italy on Car. draba (Chupp 1954). Since two European isolates from Car. draba in Romania also reside in this clade, we designate an epitype here (ex-epitype culture CBS 258.67 = CPC 5061) for this species, and fix the application of C. bizzozeriana to this clade.

Additional specimens examined: Iran: West Azerbaijan Province: Khoy, Firouragh, on leaves of Car. draba, Nov. 2011, M. Arzanlou (CCTU 1117 = CBS 136132); Khoy, Firouragh, on leaves of Car. draba, Oct. 2012, M. Arzanlou (IRAN 17027F, CCTU 1234). Zanjan Province: Tarom, Haroun Abad, on leaves of Tanacetum balsamita (Asteraceae), Sep. 2011, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17029F, CCTU 1040 = CBS 136131); Tarom, Mamalan, Oct. 2011, M. Bakhshi (IRAN 17028F, CCTU 1107); Mianeh, Oct. 2012, M. Torbati (IRAN 17025F, IRAN 17026F, CCTU 1013, CCTU 1022 = CBS 136028). Khuzestan Province: Ahvaz, on leaves of Capparis spinosa (Capparidaceae), Dec. 2011, E. Mohammadian (CCTU 1127 = CBS 136133). – Romania: Hagieni, on Car. draba, O. Constantinescu (CBS 540.71 = IMI 161110 = CPC 5060).

Cercospora beticola complex

The 16 isolates previously recognised as C<i>.</i> beticola based on a five-gene phylogenetic analysis (Groenewald et al. 2013, Bakhshi et al. 2015a), are assigned to two lineages based on the eight-gene phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 1, part 2). One, one, one, one, one, two, three and four allele groups were distinguished for the ITS, tef1, actA, cmdA, his3, tub2, rpb2 and gapdh sequences, respectively (Table 7).

Table 7.

Results from allele group designation per locus for Cercospora beticola s. lat. isolates in this study. Abbreviations of loci and collection accession numbers follow Table 1.

| Species | Culture accession number | Host |

Allele group per locus |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | actA | cmdA | his3 | tub2 | rpb2 | gapdh | |||

| C. beticola | CCTU 1057; IRAN 2651C | Chenopodium sp. | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III |

| CCTU 1065 | Chenopodium sp. | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | II | |

| CCTU 1087 | Chenopodium sp. | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III | |

| CCTU 1088; CBS 138582 | Sonchus asper | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III | |

| CCTU 1089; CPC 24911 | Plantago lanceolata | I | I | I | I | I | II | II | II | |

| CCTU 1108 | Plantago lanceolata | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | II | |

| CBS 116456; CPC 11557 (TYPE) | Beta vulgaris | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | |

| CCTU 1135 | Beta vulgaris | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III | |

| CPC 12028 | Beta vulgaris | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III | |

| CPC 12029 | Beta vulgaris | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | III | |

| C. gamsiana | CCTU 1035 | Malva sylvestris | I | I | I | I | I | I | III | IV |

| CBS 144962; CCTU 1074; CPC 24909 (TYPE) | Malva neglecta | I | I | I | I | I | I | III | IV | |

| CCTU 1109 | Malva sylvestris | I | I | I | I | I | I | III | IV | |

| CCTU 1199; CBS 136128; IRAN 2675C | Rumex crispus | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | IV | |

| CCTU 1205; CBS 136127; IRAN 2677C | Sesamum indicum | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | IV | |

| CCTU 1208; IRAN 2678C | Sonchus sp. | I | I | I | I | I | I | II | IV | |

Cercospora beticolaSacc., Nuovo Giorn. Bot. Ital. 8: 189 (1876).

Sensu Groenewald et al., Phytopathology 95: 954 (2005).

(Fig. 6)

Fig. 6.

Cercospora beticola (CCTU 1135). A. Leaf spots. B. Fasciculate conidiophores. C–G. Conidia. Bars = 10 μm.

Type: Italy: Vittorio (Treviso), on Beta vulgaris (Chenopodiaceae), Sep. 1897, P.A. Saccardo, Fungi ital. no. 197 (PAD – neotype designated by Groenewald et al. 2005); Ravenna, on B. vulgaris, 10 Jul. 2003, V. Rossi (CBS 116456 = CPC 11557 – epitype designated by Groenewald et al. 2005).

Description: Leaf spots amphigenous, distinct, circular to subcircular, 1–7 mm diam, white-grey, with grey dots (stroma with conidiophores), surrounded by distinct brown border. Mycelium internal. Caespituli amphigenous, brown. Conidiophores aggregated in loose to dense fascicles, emerging through stomatal openings or erumpent through the cuticle, arising from the upper cells of a moderately to well-developed brown stroma, to 110 μm diam; conidiophores brown, becoming paler towards apex, 2–8-septate, thick-walled, straight to geniculate-sinuous, unbranched, uniform in width, (30−)80–110(−185) × 4–5(−6) μm. Conidiogenous cells integrated, terminal or lateral, unbranched, brown, smooth, proliferating sympodially, 10–30 × 3.5–5.5 μm, mostly multi-local, sometimes mono-local; loci apical or formed on shoulders caused by geniculation, thickened, darkened, refractive, 1.5–2 μm diam. Conidia solitary, subcylindrical, filiform to acicular, straight to variously curved, hyaline, 3–15(−29)-septate, apex subacute to acute, base truncate to subtruncate, (40−)90–140(−300) × 2–5 μm; hila thickened, darkened, refractive, 1.5–2.5 μm diam.