Abstract

Rationale & Objective:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is complicated by abnormalities that reflect disruption in filtration, tubular, and endocrine functions of the kidney. Our aim was to explore the relationship of specific laboratory abnormalities and hypertension with the eGFR and albuminuria CKD staging framework.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional individual participant-level analyses in a global consortium

Setting & Study Populations:

17 CKD and 38 general population and high-risk cohorts

Selection Criteria for Studies:

Cohorts in the CKD Prognosis Consortium with data on eGFR and albuminuria as well as a measure of hemoglobin, bicarbonate, phosphorous, parathyroid hormone, potassium, or calcium, or hypertension.

Data Extraction:

Data were obtained and analyzed between July 2015 and January 2018.

Analytic Approach:

We modeled the association of eGFR and albuminuria with hemoglobin, bicarbonate, phosphorous, parathyroid hormone, potassium, and calcium using linear regression; and with hypertension and categorical definitions of each abnormality using logistic regression. Results were pooled using random-effects metaanalyses.

Results:

The CKD cohorts (n=254,666 participants) were 27% female and 10% black, with mean age 69 (SD, 12) years. The general population/high-risk cohorts (n=1,758,334) were 50% female and 2% black, with mean age 50 (16) years. There was a strong, graded association between lower eGFR and all laboratory abnormalities (odds ratios ranging from 3.27 (95% CI, 2.68-3.97) to 8.91 (95% CI, 7.22-10.99) comparing eGFR 15-29 to eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73m2); whereas albuminuria had equivocal or weak associations with abnormalities (odds ratios ranging from 0.77 (95% CI, 0.60-0.99) to 1.92 (95% CI, 1.65-2.24) comparing urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) >300 vs <30 mg/g).

Limitations:

Variation in study era, health care delivery system, typical diet, and laboratory assays.

Conclusions:

Lower eGFR was strongly associated with higher odds of multiple laboratory abnormalities. Knowledge of risk associations might help guide management in the heterogeneous group of patients with CKD.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease (CKD), glomerular filtration rate (GFR); albuminuria; staging system; laboratory tests; diabetes; meta-analysis; CKD Prognosis Consortium; laboratory abnormality; CKD stage; kidney function; individual-level meta-analysis; hemoglobin; hematocrit; serum potassium; serum bicarbonate; serum intact parathyroid hormone; serum phosphorus; serum calcium; hypertension; anemia; hyperparathyroidism

INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health problem with high risk of kidney failure, cardiovascular disease, and death. CKD is defined by both decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and presence of kidney damage (most commonly detected by albuminuria) and is staged by cause, level of GFR, and albuminuria. Across countries, the prevalence of CKD is estimated to be approximately 10-15% among adults, and multiple studies have demonstrated the relationship of both GFR and albuminuria to an increased risk for mortality, cardiovascular disease, and kidney failure.1-5

In addition to the long-term risk of adverse events, CKD is complicated by the presence of abnormalities that reflect disruption in the excretory, metabolic, and endocrine functions of the kidney. These abnormalities include anemia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia as well as hypertension, and often drive further investigations or treatment decisions. In patients with kidney failure, these are often referred to as uremic manifestations, or complications, of kidney disease and are quite common. Interestingly, these abnormalities do not occur in all patients with earlier stages of CKD. Prior studies in general population and CKD cohorts have documented the risk of abnormalities with the level of eGFR or albuminuria,6-9 but few have looked comprehensively and concomitantly across the new CKD staging system, which classifies the severity of CKD by eGFR (G) and albuminuria (A) stage.10, 11 In addition, the consistency of risk associations across diverse global cohorts along a wide range of eGFR, albuminuria, age, and diabetes has not been determined.

We utilized the large number of participants in the global Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium (CKD-PC), covering general, high cardiovascular risk, and CKD cohorts, to explore the prevalence and risk of specific laboratory abnormalities and hypertension across the 2-dimensional eGFR and albuminuria staging framework. We evaluated whether risk associations were consistent across participant characteristics, such as age, sex, race, and diabetes status, as well as individual cohorts. An appreciation of the expected levels of these laboratory values within eGFR and albuminuria stages gives important clinical information to clinicians, and may provide better guidance to assist in the delivery of individualized and precise care to patients.

Methods

Study design and data sources

In this collaborative, individual-level meta-analysis, we used data from CKD-PC member cohorts, details of which have been previously described (Item S1 provides an overview of the data analysis).12 Cohorts with at least 1,000 adult participants (500 in CKD cohorts) and eGFR, albuminuria, and long-term follow-up for mortality or kidney outcomes were invited to participate. For the present study, cohorts were additionally required to have a concurrent measurement of at least one of the following: hemoglobin or hematocrit, serum potassium, serum bicarbonate, serum intact parathyroid hormone, serum phosphorus, serum calcium, or hypertension status information. The CKD and the general population or high cardiovascular risk cohorts (herein referred to as general population/high-risk) were analyzed separately. Three large administrative cohorts (Geisinger, Mt. Sinai BioMe, SCREAM [see Item S2 for expansions of study acryonyms]) contributed their entire populations to the general population/high risk analysis and their sub-population with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 to the CKD analysis. This study was approved for use of de-identified data by the Institutional Review Board at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health (IRB Number: 3324) and the need for informed consent was waived.

Kidney Measures

As previously described, serum creatinine measurements provided by the cohorts were standardized to isotope dilution mass spectrometry traceable values.13 eGFR was estimated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation.14 Measures of albuminuria included the urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR), urine albumin excretion rate, urinary protein-creatinine ratio, or semi-quantitative dipstick protein. These measures were converted to albuminuria stages A1-A3, defined as ACR <30 mg/g, 30-299 mg/g, and ≥300 mg/g, as previously described.15, 16 In categorical analyses, for comparison purposes, we used a reference of eGFR 50 ml/min/1.73m2 and albuminuria stage A1 for both general population/high risk and CKD cohorts.

Other Covariates

Age, sex, and race were provided by the individual cohorts. Age was categorized as ≥55 and <55 years so as to approximately classify menopausal status in women. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L (126 mg/dL), non-fasting glucose ≥11.1 mmol/L (200 mg/dL), hemoglobin A1c ≥6.5%, use of glucose lowering drugs, or self-reported diabetes (Item S1). A history of CVD included myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, heart failure, and stroke. Smoking was classified as a binary variable (ever vs. never).

Outcomes

Outcomes included values of hemoglobin, potassium, serum bicarbonate, serum intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), serum phosphorus, and serum calcium, all of which were also categorized as binary variables to define anemia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, hyperparathyroidism, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin <13 g/L for men and <12 g/L for women (for cohorts with only hematocrit available, <39% for men and <36% for women, per WHO guidelines).17 Hyperkalemia was defined as potassium >5 mmol/L. Acidosis was defined as a serum bicarbonate level <22 mmol/L. Hyperparathyroidism was defined as serum intact PTH level >65 pg/mL. Hyperphosphatemia was defined as a serum phosphorus >4.5 mg/L. Hypocalcemia was defined as an albumin-corrected serum calcium level <8.5 mg/dL. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, use of antihypertensive medications, or a medical diagnosis of hypertension.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using a two-stage meta-analysis approach within general/high-risk population and CKD cohorts separately. First, each cohort was analyzed individually. Next, associations were combined using a random effects meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was quantified with the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test.

To assess the association between eGFR and continuous laboratory values, linear regression was performed, regressing the laboratory value on the eGFR splines, categorical albuminuria stage, the interaction of the two parameters, and adjusting for demographics, diabetes mellitus status, history of CVD, smoking status, BMI, and systolic blood pressure, centered at the reference point. To assess the association between eGFR and categorical laboratory abnormality, a similar procedure was followed using logistic regression. For analyses of hypertension, the approach was identical except analyses were not adjusted for systolic blood pressure. Random effects meta-analysis was performed on the difference from the reference value to report summary results across the cohorts. Interactions between eGFR and albuminuria stage were quantified using the meta-analyzed interaction term for each eGFR spline piece. Interactions that met a Bonferroni threshold for statistical significance (p<0.05/14 for general population/high risk cohorts, reflecting comparisons of A3 vs. A1 and A2 vs. A1 for 7 spline pieces and p<0.05/6 for CKD cohorts, reflecting comparisons of A3 vs. A1 and A2 vs. A1 for three spline pieces) were reported in the text. For the purposes of reporting the association between albuminuria and each laboratory abnormality, effect sizes were given at the reference point (80 and 50 ml/min/1.73m2 for general population/high-risk and CKD cohorts, respectively) since most interactions with eGFR were small and not statistically significant.

The adjusted prevalence of each abnormality at each eGFR and albuminuria stage was computed for general population/high-risk and CKD cohorts separately. We first converted the random-effects weighted, adjusted mean odds at the reference point (eGFR 50 ml/min/1.73 m2) into a prevalence estimate. We then applied the meta-analyzed odds ratios to obtain prevalence estimates at eGFR 95, 80, 65, 35, and 20 ml/min/1.73 m2 (in CKD cohorts, 65, 35, and 20 ml/min/1.73m2) for each stage of albuminuria with and without diabetes, adjusted to 60 years old, half male, non-black, 20% history of CVD, 40% ever smoker, and body-mass index 30 kg/m2. To demonstrate the variation in prevalence estimates across the cohorts, we show the 25th and 75th percentiles for prevalence estimates.

We performed the following sensitivity analyses. For analysis of hemoglobin and anemia, among CKD cohorts with data on medication use, we excluded users of erythropoietin stimulating agents and iron supplements. Similarly, for analyses of potassium and hyperkalemia, we excluded users of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, renin inhibitors, potassium-sparing diuretics, loop diuretics, thiazide diuretics, other diuretics, kayexalate, and other anti-hypertensive medications. Next, continuous associations were repeated for pre-defined populations of interest by including the relevant interaction terms with eGFR or albuminuria: age (<55 years or ≥55 years), sex, age and sex (women <55 years or ≥55 years; men <55 years or ≥55 years), race (black or non-black), and diabetes status (presence or absence).

All analyses were performed using Stata/MP 14 software (www.stata.com).

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

There were 254,666 participants in the 17 CKD cohorts (including the CKD subpopulation from three administrative high risk cohorts) and 1,758,334 participants in 38 general population/high-risk cohorts (Table 1). Tables S1-S6 show the proportion with each abnormality and mean value for each laboratory test within individual cohorts. The CKD cohorts were 27% female and 10% black, with mean age 69 (SD, 12) years, mean eGFR 50 (17) ml/min/1.73 m2; 109,143 (44%) had UACR >30 mg/g and 156,421 (62%) had diabetes. The general population/high risk cohorts were 50% female and 2% black, with mean age 50 (16) years and mean eGFR 88 (20) ml/min/1.73m2; 174,914 (10%) had UACR >30 mg/g and 286,561 (16%) had diabetes.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and number of participants with available data on each of the laboratory abnormalities.

| Study | Region | Clinical Characteristics | No. with available laboratory data | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age*** | Female sex |

Black Race |

DM | eGFR*** | albuminuria /proteinuria‡ |

Hb | K | Bicarb | PTH | Phos | Ca | HTN | ||

| CKD Cohorts | |||||||||||||||

| AASK | US | 1094 | 55 (11) | 39% | 100% | 0% | 46 (15) | 55% | 1066 | 984 | 1093 | 984 | 1094 | ||

| BC CKD | CA | 11880 | 71 (13) | 46% | 0% | 50% | 33 (16) | 72% | 11655 | 11785 | 11162 | 10075 | 11237 | 10966 | 11880 |

| CanPREDDICT | CA | 2061 | 68 (13) | 38% | 2% | 50% | 27 (9) | 74% | 2045 | 2052 | 1822 | 1900 | 1978 | 1956 | 2061 |

| CARE FOR HOMe | DE | 369 | 66 (13) | 43% | 0% | 89% | 49 (17) | 46% | 371 | 371 | 371 | 370 | 369 | ||

| CCF | US | 19249 | 72 (12) | 55% | 14% | 34% | 47 (14) | 29% | 12696 | 17498 | 16218 | 1758 | 3030 | 12923 | 19249 |

| CKD-JAC | JP | 2679 | 61 (12) | 38% | 0% | 32% | 37 (17) | 88% | 2639 | 2640 | 2670 | 2379 | 2413 | 2679 | |

| CRIB | UK | 375 | 62 (14) | 35% | 5% | 17% | 22 (11) | 84% | 364 | 373 | 324 | 316 | 360 | 374 | 375 |

| GCKD | DE | 5159 | 61 (12) | 40% | 0% | 36% | 49 (18) | 57% | 5127 | 5030 | 5160 | 5159 | 5159 | ||

| Geisinger CKD† | US | 24611 | 71 (12) | 56% | 1% | 64% | 46 (12) | 43% | 19008 | 24417 | 24358 | 7803 | 12879 | 1778 | 24611 |

| Gonryo | JP | 3009 | 63 (15) | 47% | 0% | 46% | 71 (32) | 52% | 3044 | 2278 | 2042 | 3009 | |||

| MASTERPLAN | NL | 670 | 60 (13) | 31% | 0% | 24% | 36 (15) | 72% | 670 | 670 | 668 | 638 | 670 | 669 | 670 |

| MDRD | US | 1736 | 51 (13) | 40% | 12% | 6% | 41 (21) | 74% | 1719 | 830 | 1725 | 1735 | 1725 | 1736 | |

| MMKD | Multi§ | 202 | 47 (12) | 34% | 0% | 0% | 47 (30) | 92% | 202 | 201 | 202 | 202 | 202 | ||

| Mt Sinai BioMe CKD† | US | 3521 | 63 (13) | 56% | 31% | 58% | 43 (13) | 50% | 1931 | 3518 | 3520 | 1538 | 1904 | 3112 | 3521 |

| PSP-CKD | UK | 9434 | 76 (11) | 59% | 2% | 36% | 50 (14) | 27% | 2223 | 9405 | 228 | 895 | 1462 | 9434 | |

| RCAV | US | 127812 | 69 (10) | 3% | 16% | 82% | 55 (15) | 44% | 108044 | 124843 | 119959 | 25507 | 98308 | 127812 | |

| RENAAL | Multi¶ | 1512 | 60 (7) | 37% | 15% | 100% | 39 (13) | 100% | 1510 | 1513 | 1510 | 1509 | 1512 | ||

| SCREAM CKD† | SE | 33232 | 65 (12) | 55% | 0% | 26% | 47 (12) | 31% | 30209 | 29383 | 7011 | 6850 | 9517 | 15330 | 33232 |

| SRR-CKD | SE | 3051 | 68 (15) | 33% | 0% | 38% | 25 (12) | 79% | 3032 | 2591 | 1613 | 2420 | 2975 | 2833 | 3051 |

| Sunnybrook | CA | 3010 | 61 (18) | 47% | 0% | 47% | 56 (31) | 59% | 2822 | 2965 | 2748 | 1415 | 2389 | 2426 | 3010 |

| Subtotal | 254666 | 69 (12) | 27% | 10% | 62% | 50 (17) | 44% | 209311 | 235549 | 192340 | 42985 | 88069 | 184328 | 254666 | |

| Gen Pop Cohorts | |||||||||||||||

| Aichi | JP | 4987 | 49 (7) | 20% | 0% | 9% | 100 (13) | 3% | 4987 | 4987 | |||||

| ARIC* | US | 11889 | 64 (6) | 56% | 23% | 18% | 86 (17) | 9% | 11889 | ||||||

| AusDiab* | AU | 11198 | 52 (14) | 55% | 0% | 8% | 86 (17) | 7% | 11198 | ||||||

| Beijing | CN | 1533 | 60 (10) | 50% | 0% | 29% | 83 (14) | 6% | 1530 | 1533 | |||||

| BIS | DE | 2055 | 80 (7) | 53% | 0% | 26% | 65 (17) | 26% | 1995 | 2048 | 2052 | 2055 | |||

| ChinaNS* | CN | 46810 | 47 (15) | 57% | 0% | 8% | 101 (18) | 12% | 46810 | ||||||

| CHS* | US | 2984 | 78 (5) | 59% | 17% | 18% | 66 (16) | 20% | 2984 | ||||||

| CIRCS | JP | 11916 | 54 (9) | 61% | 0% | 3% | 89 (15) | 3% | 11475 | 8034 | 11916 | ||||

| ESTHER* | DE | 9744 | 62 (7) | 55% | 0% | 19% | 87 (20) | 12% | 9744 | ||||||

| Framingham* | US | 2956 | 59 (10) | 53% | 0% | 8% | 88 (19) | 12% | 2956 | ||||||

| Gubbio | IT | 1684 | 54 (6) | 55% | 0% | 5% | 84 (12) | 4% | 1684 | 1684 | 1684 | 1684 | |||

| IPHS | JP | 97769 | 59 (10) | 66% | 0% | 3% | 86 (14) | 2% | 97740 | 97769 | |||||

| JMS | JP | 5124 | 54 (11) | 64% | 0% | 55% | 98 (15) | 2% | 5091 | 5124 | |||||

| KHS | KR | 243779 | 44 (10) | 33% | 0% | 5% | 88 (14) | 14% | 243716 | 108185 | 152742 | 224193 | 243779 | ||

| MESA* | US | 6796 | 62 (10) | 53% | 28% | 13% | 83 (16) | 10% | 6796 | ||||||

| MRC | UK | 12367 | 81 (5) | 61% | 0% | 8% | 57 (15) | 7% | 12101 | 11840 | 11334 | 12026 | 12367 | ||

| NHANES | US | 56017 | 47 (19) | 52% | 22% | 12% | 97 (25) | 12% | 51434 | 57208 | 41359 | 9774 | 57208 | 41405 | 56017 |

| NIPPON | JP | 10382 | 50 (13) | 56% | 0% | 3% | 84 (17) | 3% | 10382 | ||||||

| DATA80* | |||||||||||||||

| NIPPON DATA90 | JP | 7612 | 53 (14) | 58% | 0% | 5% | 94 (17) | 3% | 7612 | 7612 | |||||

| NIPPON | JP | 2749 | 59 (16) | 57% | 0% | 13% | 97 (17) | 3% | 2730 | 2749 | |||||

| DATA2010 | |||||||||||||||

| Ohasama | JP | 3300 | 60 (11) | 59% | 0% | 9% | 97 (13) | 6% | 1926 | 3300 | |||||

| PREVEND | NL | 8060 | 50 (13) | 50% | 1% | 4% | 96 (16) | 11% | 7319 | 7314 | 7319 | 7313 | 8060 | ||

| Rancho Bernardo | US | 1484 | 71 (12) | 60% | 0% | 14% | 66 (16) | 15% | 1484 | 1484 | 1484 | 1484 | |||

| REGARDS | US | 27727 | 65 (9) | 54% | 40% | 21% | 85 (20) | 15% | 19070 | 2700 | 1960 | 1347 | 27727 | ||

| RSIII | NL | 3519 | 57 (7) | 57% | 1% | 13% | 86 (14) | 6% | 3525 | 3375 | 3519 | ||||

| SEED* | SG | 7028 | 58 (10) | 49% | 0% | 29% | 86 (19) | 24% | 7028 | ||||||

| Taiwan MJ | TW | 501704 | 41 (14) | 51% | 0% | 5% | 89 (18) | 2% | 501646 | 159268 | 369932 | 369833 | 501704 | ||

| Takahata | JP | 3524 | 63 (10) | 55% | 0% | 8% | 98 (13) | 15% | 3523 | 1923 | 1923 | 1923 | 3524 | ||

| ULSAM | SE | 1123 | 71 (1) | 0% | 0% | 13% | 76 (11) | 16% | 894 | 1104 | 1089 | 1123 | |||

| Subtotal | 1107820 | 47 (15) | 49% | 3% | 7% | 89 (18) | 7% | 970255 | 358475 | 41359 | 20682 | 612113 | 662665 | 1107820 | |

| High Risk Cohorts | |||||||||||||||

| ADVANCE | Multi** | 11033 | 66 (6) | 43% | 0% | 100% | 78 (17) | 31% | 11033 | 11033 | |||||

| Geisinger | US | 65051 | 61 (15) | 52% | 2% | 62% | 80 (27) | 30% | 46072 | 64503 | 64341 | 51372 | 65051 | ||

| Maccabi | IL | 264255 | 57 (14) | 49% | 0% | 34% | 86 (21) | 16% | 253333 | 246712 | 19967 | 71310 | 153794 | 264255 | |

| Mt Sinai BioMe | US | 8109 | 56 (14) | 57% | 33% | 51% | 73 (28) | 35% | 4346 | 8044 | 8047 | 7240 | 8109 | ||

| NZDCS* | NZ | 31622 | 61 (14) | 50% | 0% | 100% | 76 (23) | 9% | 31622 | ||||||

| Pima | US | 5074 | 33 (14) | 56% | 0% | 27% | 120 (19) | 20% | 5058 | 5074 | |||||

| SCREAM | SE | 260047 | 48 (18) | 54% | 0% | 12% | 93 (24) | 11% | 232861 | 208611 | 12001 | 83703 | 260047 | ||

| SMART | NL | 3691 | 58 (13) | 29% | 0% | 25% | 77 (21) | 33% | 3684 | 3691 | |||||

| ZODIAC | NL | 1632 | 67 (12) | 56% | 0% | 100% | 68 (17) | 8% | 1153 | 1203 | 1154 | 1153 | 1632 | ||

| Subtotal | 650514 | 54 (17) | 51% | 1% | 33% | 88 (24) | 15% | 545354 | 540056 | 84389 | 21170 | 72464 | 297262 | 650514 | |

| Subtotal Gen Pop/High Risk | 1758334 | 50 (16) | 50% | 2% | 16% | 88 (20) | 10% | 1515609 | 898531 | 125748 | 41852 | 684577 | 959927 | 1758334 | |

| Total† | 1951875 | 1673772 | 1076762 | 283199 | 84837 | 772646 | 1122573 | 1951875 | |||||||

Expansions of study acronyms are provied in Item S2. DM: diabetes mellitus; HTN: hypertension; Hb: hemoglobin; K: potassium; PTH: parathyroid hormone; Phos: phosphorous; Ca: corrected calcium; DE, Germany; JP, Japan; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America; CA, Canada; SE, Sweden, CN, China; AU, Australia; NL, Netherlands; KR, South Korea; IT, Italy; SG, Singapore; TW, Taiwan; IL, Israel; NZ, New Zealand; gen pop, general population

Studies with only HTN

CKD population from three administrative high risk cohorts, not included in the total N

Defined as urinary albumin-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g OR protein-creatinine ratio ≥50 mg/g or dipstick protein ≥1+.

Participants are from Austria, DE, and IT

Participants are from Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Chile, CN, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, DE, Hungary, IL, IT, JP, Malaysia, Mexico, NL, NZ, Peru, Portugal, Russia, SG, Slovakia, Spain, UK, US, Venezuela

Participants are from AU, CA, CN, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, DE, Hungary, India, Ireland, IT, Lithuania, Malaysia, NL, NZ, Philippines, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, UK

mean (standard deviation)

Associations between eGFR, albuminuria and laboratory tests

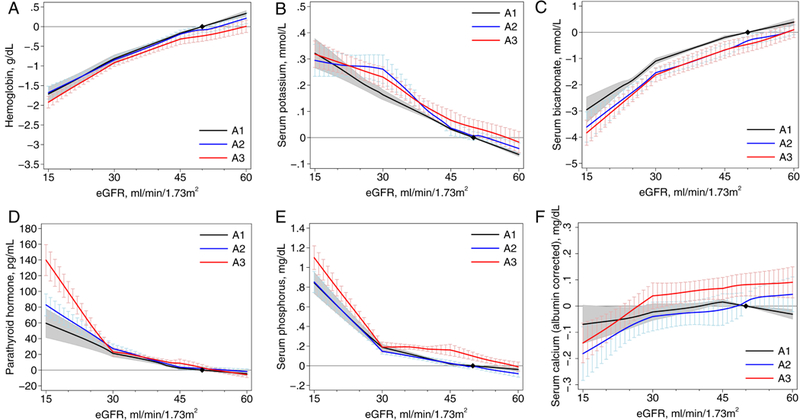

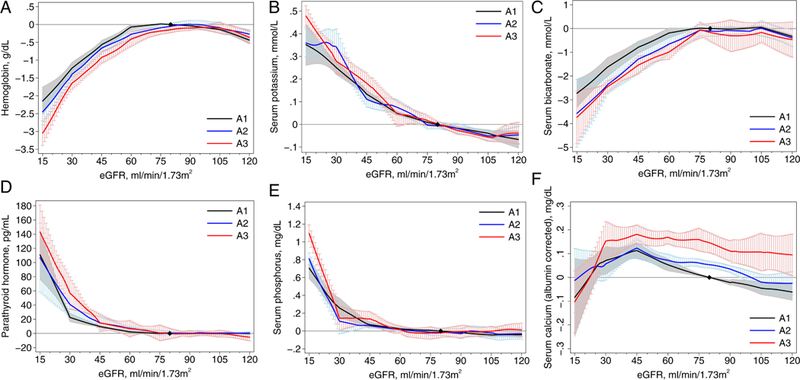

Lower eGFR was associated with lower levels of hemoglobin and bicarbonate, and higher levels of potassium, PTH, and phosphorus in the CKD cohorts, with similar associations in the general population/high risk cohorts (Figures 1 and 2). For phosphorus, PTH, and calcium there appeared to be a sharper increase in risk below eGFR 30 ml/min/1.73m2. For the general population/high risk cohorts, where the associations were evaluated across the range of eGFR, most of the associations became significant at <60 ml/min/1.73m2 (95% confidence intervals do not overlap the x-axis), with the exception of PTH where the threshold was 71 ml/min/1.73m2 and of potassium where the association was continuous across the range. For all abnormalities, there was quantitative but not qualitative differences across the individual cohorts (Figures S1-S6).

Figure 1.

Associations between estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and continuous laboratory measures by albuminuria stages in chronic kidney disease cohorts: (A) hemoglobin, (B) potassium, (C) bicarbonate, (D) parathyroid hormone, (E) phosphorus, and (F) calcium. The y-axis depicts the meta-analyzed difference from the mean adjusted value at eGFR of 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria wih albumin excretion < 30 mg/g. eGFR was modeled as a 3-piece linear spline with knots at 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2; the reference point in continuous analysis was set at 50 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Figure 2.

Association between estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and continuous laboratory measures by albuminuria stages in general population and high-risk cohorts: (A) hemoglobin, (B) potassium, (C) bicarbonate, (D) parathyroid hormone, (E) phosphorus, and (F) calcium. The y- axis depicts the meta-analyzed difference from the mean adjusted value at eGFR of 80 mL/min/1.73 m2 and albuminuria with albumin excretion < 30 mg/g. eGFR was modeled as a 7-piece linear spline with knots at 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, and 105 mL/min/1.73 m2; the reference point in continuous analysis was set at 80 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Overall, the association of albuminuria stages with laboratory abnormalities was absent or minimal in both CKD and general population/high risk cohorts (Figures 1 and 2). In the CKD cohorts, higher albuminuria was associated with slightly lower values of hemoglobin (−0.24 [95% CI, −0.37 to −0.10] g/dL for A3 vs. A1) and bicarbonate (−0.46 [95% CI, −0.74 to −0.17] mmol/L for A3 vs. A1) and slightly higher values of potassium (0.04 [95% CI, 0.01 to 0.07] mmol/L, A3 vs. A1) and phosphorus (0.10 [95% CI, 0.06 to 0 14] mg/dL). For PTH, the magnitude of the association with albuminuria differed substantially at eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73m2, with larger effect sizes in this range in the CKD cohorts. For calcium, higher levels of albuminuria were associated with higher levels of (albumin-corrected) calcium at higher but not lower levels of eGFR.

In sensitivity analyses in CKD cohorts with available medications, the results for hemoglobin were consistent when participants using iron supplementation and erythropoietin stimulating agents were excluded (Figure S7). After excluding medications known to affect potassium, the small difference by level of albuminuria was no longer statistically significant (A3 vs. A1: 0.02 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.07] mmol/L) (Figure S8).

After adjusting for albuminuria, people with diabetes had similar relationships between laboratory abnormalities and eGFR (Figures S9-S10), although for the same level of eGFR, participants with diabetes consistently had lower levels of hemoglobin and bicarbonate, and higher levels of potassium and phosphorus. For example, in CKD cohorts, the difference in hemoglobin level by diabetes status was −0.43 (95% CI, −0.57 to −0.28) g/dL, which was slightly smaller than the difference in hemoglobin level between eGFR 30 and 50 ml/min/1.73m2 (−0.81 [95% CI, −0.91 to −0.72] g/dL). There were also consistent relationships between eGFR and laboratory abnormalities in participants <55 years old and ≥55 years old (Figures S11-S12). Similar relationships were seen by sex (Figures S13-S14) and when grouped by age as a proxy for menopausal status (women <55 years old and ≥55 years old; Figures S15-S16). However, for the same level of eGFR and other covariates, women had lower levels of hemoglobin and potassium and higher levels of bicarbonate, phosphate, and calcium compared to men. Although there were few cohorts with both black and non-black participants, associations between eGFR and laboratory abnormalities were also consistent by race (Figures S17-S18).

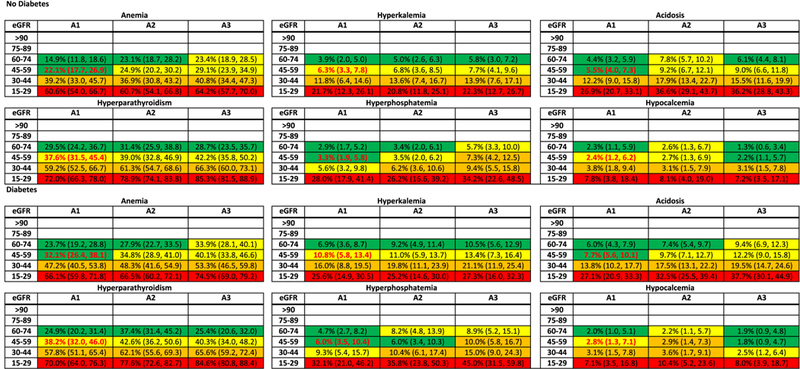

Associations of eGFR and albuminuria with categorical laboratory abnormalities

Overall, there was an increase in the risk for each laboratory abnormality by category of lower eGFR (Figure S19). For example, odds ratios ranged from 3.27 (95% CI, 2.68-3.97) to 8.91 (95% CI, 7.22-10.99) across abnormalities, comparing eGFR 15-29 to eGFR 45-59 ml/min/1.73m2. There was a lesser gradient observed for higher albuminuria [odds ratios ranging from 0.91 (95% CI, 0.73-1.13) to 1.80 (95% CI, 1.26-2.58) across abnormalities, comparing A3 to A1]. In both general population/high-risk and CKD cohorts, anemia and hyperparathyroidism were the most common laboratory abnormalities for a given eGFR and albuminuria stage, and hypocalcemia was the least common (Figure 3 and S20). In the CKD cohorts, the estimated prevalence of anemia, hyperkalemia, and hyperphosphatemia was higher in persons with diabetes vs. those without diabetes, but lesser or no differences were observed for the other abnormalities. In the general population/high-risk cohorts, differences by diabetes status were generally smaller.

Figure 3.

Meta-analyzed adjusted prevalence (25th and 75th percentile cohort) of abnormalities (categorical laboratory measures) in chronic kidney disease by diabetes status. The adjusted prevalence of each abnormality at each estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and albuminuria stage was computed as follows: first, we converted the random-effects weighted adjusted mean odds at the reference point (eGFR, 50 mL/min/1.73 m2) into a prevalence estimate. To the reference estimate, we applied the meta-analyzed odds ratios to obtain prevalence estimates at eGFRs of 95, 80, 65, 35, and 20 mL/min/1.73 m2 for each stage of albuminuria with and without diabetes. The prevalence estimates were adjusted to 60 years old, half men, nonblack, 20% history of cardiovascular disease, 40% ever smoker, and body mass index of 30 kg/m2. The 25th and 75th percentiles for predicted prevalence were the estimates from individual cohorts in the corresponding percentiles of the random-effects weighted distribution of adjusted odds. This was done separately for each abnormality. Note that the cohorts included in the analyses of each abnormality may differ based on data availability. For example, the cohort in the 25th percentile of anemia may not be the same as the cohort in the 25th percentile of hyperparathyroidism. Color coding is based on odds ratio quartile within each abnormality. Bold red font indicates the reference cell. Definitions of each abnormality are as follows: anemia: Hgb, male < 13 g/dL, female < 12 g/dL; Hct, male < 39%, female < 36%; hyperkalemia: potassium > 5 mmol/L; acidosis, bicarbonate < 22 mmol/L; hyperparathyroidism, intact parathyroid hormone > 65 pg/mL; hyperphosphatemia, phosphorus > 4.5 mg/dL; and hypocalcemia, corrected calcium < 8.5 mg/dL.

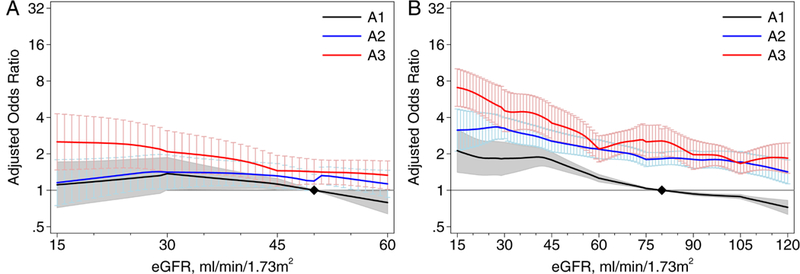

Associations of eGFR and albuminuria with hypertension

For the CKD cohorts, there was no association between eGFR and hypertension, but albuminuria was an independent risk factor (adjusted OR for stage A3 vs. A1: 1.42 [95% CI, 1.12-1.80]). At higher levels of eGFR observed in the general population/high risk cohorts, the association between eGFR and hypertension was slightly stronger, as was the association with albuminuria (adjusted OR for stage A3 vs. A1: 2.77 [95% CI, 2.26-3.39]) (Figure 4). There were quantitative but not qualitative differences across the individual cohorts (Figure S21). Results were also similar by predefined populations of interest (Figures S22-S23).

Figure 4.

Association between estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and hypertension by albuminuria stages in (A) chronic kidney disease (CKD) cohorts and (B) general population and high-risk cohorts. Abbreviations: A1, A2, A3 refer to albuminuria stages: A1, <30 mg/g; A2, 30-299 mg/g; and A3, 300+ mg/g. The y-axis refers to the meta-analyzed adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval compared to a reference of eGFR of 50 (80 in the right graph) mL/min/1.73 m2 in A1 (black diamond). In analyses of the general population/high-risk cohorts, eGFR was modeled as a 7-piece linear spline with knots at 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, and 105 mL/min/1.73 m2; the reference point in continuous analysis was set at 80 mL/min/1.73 m2. In analyses of CKD pop-ulations, eGFR was modeled as a 3-piece linear spline with knots at 30 and 45 mL/min/1.73 m2; the reference point in continuous analysis was set at 50 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Discussion

In this large, individual-level meta-analysis of participants from more than 50 cohorts including more than two million participants, we describe the association of laboratory abnormalities and hypertension with level of eGFR and albuminuria across CKD and general population/high-risk cohorts, geographic regions, and individual characteristics including diabetes, age, sex, race, and a proxy for menopausal status. We found a consistent and graded association of hemoglobin, potassium, bicarbonate, PTH, phosphorus as well as calcium in the lower range of eGFR, which was only modestly affected by level of albuminuria, with the exception of PTH in CKD cohorts. For a given level of eGFR and albuminuria, we observed that the most common laboratory abnormalities were anemia and hyperparathyroidism, particularly among the CKD cohorts. The relationship between eGFR and hypertension was present only in the general population/high risk cohorts, perhaps reflecting the fact that the majority of patients with CKD have a diagnosis of hypertension.

Multiple studies have documented the association of risk of laboratory abnormalities with eGFR,1, 6-9 but few studies examined associations with albuminuria. In the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study, lower levels of eGFR, but not higher levels of urine protein, were strongly associated with anemia, hypoalbuminemia, acidosis, and hyperphosphatemia and hypertension.11 Similarly, in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), a representative population cohort in the United States, lower eGFR was strongly associated with anemia, hypoalbuminemia, acidosis, hypertension, and hyperparathyroidism, but there was minimal association between higher levels of albuminuria and all of these abnormalities.10 In our study, we expanded upon these studies by using both continuous values of the laboratory tests and categorical assessments of the abnormalities, and demonstration of the consistency of the risk associations across CKD and general population/high risk cohort, geographic regions, and participant characteristics including diabetes, age, sex, race, and a proxy for menopausal status. Although we found the relative risks to be fairly consistent within subgroups and across cohorts, the large number of cohorts allowed us to investigate heterogeneity in adjusted absolute risk. We report that the adjusted prevalence varies by type of cohort (CKD vs. general population/high-risk) as well as between individual cohorts, with as much as 5-fold variation between individual cohorts at the 25th and 75th percentile of adjusted risk.

There are potential public health, clinical, and research implications from this study. First, in the general population/high-risk cohorts, where the associations between laboratory abnormality and eGFR were observed throughout the eGFR range, many abnormalities appeared or worsened at a threshold near 60 ml/min/1.73m2. In both the general population/high risk cohorts and the CKD cohorts, there was a graded association with abnormalities at lower levels of eGFR, and the results were consistent by key subgroups including diabetes status, sex, age, and race. These data provide further support for the current definition and staging system based on eGFR, with eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73m2 as the threshold for disease classification and severity of CKD, regardless of subgroups.1, 6 The absence of strong associations with albuminuria reinforce the KDIGO guideline recommendations for frequency of these laboratory tests based on eGFR stage, but not albuminuria stage.18 Second, these data may assist clinicians to better characterize the severity of kidney disease and direct intensity of investigation and care, such as range and frequency of testing for abnormalities. For example, for some abnormalities, higher prevalence was observed in persons with diabetes. Third, these data may guide interpretation of the potential etiology of the observed abnormality. For example, even in those with eGFR 15-29 ml/min/1.73m2, only approximately 25% and 40% of the general population/high risk and CKD populations, respectively, had anemia. Thus, a finding of anemia in patients with severe reduction of eGFR should not preclude investigations for other causes; similarly, finding of anemia at higher levels of eGFR is less likely to be attributable to kidney disease alone. Finally, the data might improve identification of individuals for entry into studies examining progression of CKD, if the prevalence of laboratory abnormalities provides prognostic information in addition to eGFR and albuminuria values.19

Strengths of this study include the large number of cohorts and sample size that allow for description of the association of kidney measures, hypertension, and laboratory abnormalities across a variety of clinical settings. Risk associations were fairly consistent across individual cohorts, and between the general population/high risk and CKD cohorts. Where data were available, we described similar associations between users and nonusers of medications that could affect laboratory abnormalities, such as erythropoietin stimulating agents for hemoglobin and medications that affect potassium. Limitations include variation between individual cohorts in study era, health care delivery systems, diet, and laboratory assays, which may explain some of the observed varation in prevalence estimates. Differences in study era and health systems might have led to different patterns of testing, whereas assay differences could affect categorical definitions of the laboratory abnormalities and their association with eGFR or albuminuria stage. In particular, assays for PTH, calcium, and albumin (required for adjustment of the calcium) are known to vary widely. Improvements in assay standardization and precision could reveal stronger associations. Regional variation in diet could have led to between-cohort differences in several of the abnormalities including anemia, hyperkalemia, and acidosis. Information on medications was limited and only included erythropoietin stimulating agents, iron supplementation, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, and diuretics. Thus, our estimates reflect as-treated eGFR, albuminuria, and abnormalities. Covariates used in adjustment were occasionally missing, requiring imputation, which underestimates their variability. We were able to examine differences in associations by diabetes status, but not by cause of kidney disease. Various primary causes of kidney diseases might affect excretory, metabolic, and endocrine kidney functions differently. Prevalence estimates for each abnormality varied by individual cohort even after taking into account eGFR, albuminuria, and measured participant characteristics, likely reflecting differences in selection into individual cohorts or unmeasured determinants of that abnormality (e.g., variation in anemia might be explained by a higher prevalence of beta thalassemia in certain populations).

This study provides a comprehensive description of level of abnormalities by eGFR and albuminuria level. The results supports the current definition and staging system for all populations and set the stage for further refinements of individualized clinical action plans for patients with CKD. Future studies should address how these abnormalities vary by cause of disease, how they appear in combination with other abnormalities in individual patients, and importantly, how the risk for kidney failure, death, and other adverse events differs based on presence or absence of specific abnormalities and their combination. Finally, previous clinical trials aimed at treating these abnormalities have generally targeted specific solitary thresholds for abnormalities. A better understanding of expected values within specific eGFR categories may allow targeting of different thresholds depending on eGFR. Improved understanding of the complexity of kidney diseases by a more thorough characterization of the different laboratory abnormalities reflecting multiple functions of the kidney may help optimize investigation and care for the heterogeneous group of patients with CKD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the CKD-PC investigators/collaborators for sharing data or output for this meta-analysis and for their comments on the manuscript, as well as Yingying Sang and the Data Coordinating Center members listed above for contributing to data analysis. Item S3 lists acknowledgements for collaborating cohorts.

Support: The CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center is funded in part by a program grant from the US National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK100446-01). A variety of sources have supported enrollment and data collection including laboratory measurements, and follow-up in the collaborating cohorts of the CKD-PC. These funding sources include government agencies such as National Institutes of Health (NIH) and medical research councils as well as foundations and industry sponsors listed in Item 3 in the supplement. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Gutierrez received consulting fees from Keryx and Amgen and grant support from NIH, AHA, and Keryx Biopharmaceuticals. Dr. Miura received grant support from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan. Dr. Peralta received consulting fees and stock options from Cricket Health, Inc and grant support from NKF and AHA. Dr. Rothenbacher received consulting fees from Basilea Pharma, Novartis Pharma, and Basel (Switzerland). Dr. Shlipak received consulting fees from the University of Washington, stock options from TAI Diagnostics and Cricket Health, Inc., and grant support from Cricket Health, Inc. Dr. Kovesdy received consulting fees from Amgen, Abbvie, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Fresenius Medical Care, and Relypsa, lecture fees from Abbott, Keryx, and Sanofi-Genzyme, travel support from Amgen, Abbvie, Bayer, Fresenius Medical Care, Abbott, Keryx, and Sanofi-Genzyme, grant support from the NIH, and royalties from UpToDate for chapters on inflammation and metabolic acidosis. Dr. Woodward received consulting fees from Amgen and grant support from the European Union, NHMRC, and NIH.

Article Information

CKD-Prognosis Consortium Investigators/Collaborators: AASK: Brad Astor, Larry Appel, Tom Greene, Teresa Chen; ADVANCE: John Chalmers, Mark Woodward, Hisatomi Arima, Vlado Perkovic; Aichi: Hiroshi Yatsuya, Koji Tamakoshi, Yuanying Li, Yoshihisa Hirakawa; ARIC: Josef Coresh, Kunihiro Matsushita, Morgan Grams, Yingying Sang; AusDiab: Kevan Polkinghorne, Steven Chadban, Robert Atkins; BC CKD: Adeera Levin, Ognjenka Djurdjev; Beijing: Luxia Zhang, Lisheng Liu, Minghui Zhao, Fang Wang, Jinwei Wang; BIS: Elke Schaeffner, Natalie Ebert, Peter Martus; CanPREDDICT: Adeera Levin, Ognjenka Djurdjev, Mila Tang; CARE FOR HOMe: Gunnar Heine, Insa Emrich, Sarah Seiler, Adam Zawada; CCF: Joseph Nally, Sankar Navaneethan, Jesse Schold; China NS: Luxia Zhang, Minghui Zhao, Fang Wang, Jinwei Wang; CHS: Michael Shlipak, Mark Sarnak, Ronit Katz, Jade Hiramoto; CIRCS: Hiroyasu Iso, Kazumasa Yamagishi, Mitsumasa Umesawa, Isao Muraki; CKD-JAC: Masafumi Fukagawa, Shoichi Maruyama, Takayuki Hamano, Takeshi Hasegawa, Naohiko Fujii; CRIB: David Wheeler, John Emberson, John Townend, Martin Landray; ESTHER: Hermann Brenner, Ben Schöttker, Kai-Uwe Saum, Dietrich Rothenbacher; Framingham: Caroline Fox, Shih-Jen Hwang; GCKD: Anna Köttgen, Florian Kronenberg, Markus P. Schneider; Kai-Uwe Eckardt; Geisinger: Jamie Green, H Lester Kirchner, Alex R Chang, Kevin Ho; Gonryo: Sadayoshi Ito, Mariko Miyazaki, Masaaki Nakayama, Gen Yamada; Gubbio: Massimo Cirillo; IPHS: Fujiko Irie, Toshimi Sairenchi; JMS: Shizukiyo Ishikawa, Yuichiro Yano, Kazuhiko Kotani, Takeshi Nakamura; KHS: Sun Ha Jee, Heejin Kimm, Yejin Mok; Maccabi: Gabriel Chodick, Varda Shalev; MASTERPLAN: Jack F. M. Wetzels, Peter J Blankestijn, Arjan D van Zuilen, Jan van den Brand; MDRD: Mark Sarnak, Lesley Inker; MESA: Carmen Peralta, Jade Hiramoto, Ronit Katz, Mark Sarnak; MMKD: Florian Kronenberg, Barbara Kollerits, Eberhard Ritz; MRC: Dorothea Nitsch, Paul Roderick, Astrid Fletcher; Mt Sinai BioMe: Erwin Bottinger, Girish N Nadkarni, Stephen B Ellis, Rajiv Nadukuru; NHANES: Yingying Sang; NIPPON DATA80: Hirotsugu Ueshima, Akira Okayama, Katsuyuki Miura, Sachiko Tanaka; NIPPON DATA90: Hirotsugu Ueshima, Tomonori Okamura, Katsuyuki Miura, Sachiko Tanaka; NIPPON DATA2010: Katsuyuki Miura, Akira Okayama, Aya Kadota, Sachiko Tanaka; NZDCS: Timothy Kenealy, C Raina Elley, John F Collins, Paul L Drury; Ohasama: Takayoshi Ohkubo, Kei Asayama, Hirohito Metoki, Masahiro Kikuya, Masaaki Nakayama; Pima: Robert G Nelson, William C Knowler; PREVEND: Ron T Gansevoort, Stephan JL Bakker, Eelco Hak, Hiddo J L Heerspink; PSP-CKD: Nigel Brunskill, Rupert Major, David Shepherd, James Medcalf; Rancho Bernardo: Simerjot K Jassal, Jaclyn Bergstrom, Joachim H Ix, Elizabeth Barrett-Connor; RCAV: Csaba Kovesdy, Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Keiichi Sumida; REGARDS: Orlando M Gutierrez, Paul Muntner, David Warnock, William McClellan; RENAAL: Hiddo J L Heerspink, Dick de Zeeuw, Barry Brenner; RSIII: Sanaz Sedaghat, M Arfan Ikram, Ewout J Hoorn, Abbas Dehghan; SCREAM: Juan J Carrero, Alessandro Gasparini, Björn Wettermark, Carl-Gustaf Elinder; SEED: Tien Yin Wong, Charumathi Sabanayagam, Ching-Yu Cheng, Riswana Banu Binte Mohamed Abdul Sokor; SMART: Frank L.J. Visseren; SRR-CKD: Marie Evans, Mårten Segelmark, Maria Stendahl, Staffan Schön; Sunnybrook: Navdeep Tangri, Maneesh Sud, David Naimark; Taiwan MJ: Chi-Pang Wen, Chwen-Keng Tsao, Min-Kugng Tsai, Chien-Hua Chen; Takahata: Tsuneo Konta, Atsushi Hirayama, Kazunobu Ichikawa; ULSAM: Lars Lannfelt, Anders Larsson, Johan Ärnlöv; ZODIAC: Henk J.G. Bilo, Gijs W.D. Landman, Kornelis J.J. van Hateren, Nanne Kleefstra; CKD-PC Steering Committee: Josef Coresh (Chair), Ron T Gansevoort, Morgan E. Grams, Stein Hallan, Csaba P Kovesdy, Andrew S Levey, Kunihiro Matsushita, Varda Shalev, Mark Woodward; CKD-PC Data Coordinating Center: Shoshana H Ballew (Assistant Project Director), Jingsha Chen (Programmer), Josef Coresh (Principal Investigator), Morgan E Grams (Director of Nephrology Initiatives), Lucia Kwak (Programmer), Kunihiro Matsushita (Director), Yingying Sang (Lead Programmer), Aditya Surapaneni (Programmer), Mark Woodward (Senior Statistician).

Footnotes

The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Peer Review: Received ______. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with editorial input from an Acting Editor-in-Chief (Editorial Board Member Gregory E. Tasian, MD, MSc, MSCE). Accepted in revised form August 15, 2018. The involvement of an Acting Editor-in-Chief to handle the peer-review and decision-making processes was to comply with AJKD’s procedures for potential conflicts of interest for editors,

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lesley A. Inker, Division of Nephrology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Morgan E. Grams, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD.

Andrew S. Levey, Division of Nephrology at Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Josef Coresh, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD.

Massimo Cirillo, Department “Scuola Medica Salernitana”, University of Salerno, Italy.

John F Collins, Department of Renal Medicine, Auckland City Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand.

Ron T. Gansevoort, Department of Nephrology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

Orlando M. Gutierrez, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL; Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Takayuki Hamano, Department of Comprehensive Kidney Disease Research, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan.

Gunnar H. Heine, Department for Internal Medicine IV, Nephrology and Hypertension, Saarland University Medical Center, Homburg, Germany.

Shizukiyo Ishikawa, Division of Community and Family Medicine, Center for Community Medicine, Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan.

Sun Ha Jee, Department of Epidemiology and Health Promotion, Graduate School of Public Health, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea.

Florian Kronenberg, Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Department of Medical Genetics, Molecular and Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria and German Chronic Kidney Disease study.

Martin J. Landray, Medical Research Council-Population Health Research Unit, Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit, and Big Data Institute, Nuffield Department of Population Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Katsuyuki Miura, Department of Public Health and Center for Epidemiologic Research in Asia, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, Japan.

Girish N. Nadkarni, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York.

Carmen A. Peralta, Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco.

Dietrich Rothenbacher, Division of Clinical Epidemiology and Ageing Research, German Cancer Centre (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany and Institute of Epidemiology and Medical Biometry, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Elke Schaeffner, Charité University Medicine, Institute of Public Health, Berlin, Germany.

Sanaz Sedaghat, Department of Epidemiology, Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Michael Shlipak, San Francisco VA Medical Center, San Francisco, USA and University of California, San Francisco, USA.

Luxia Zhang, Peking University Institute of Nephrology, Division of Nephrology, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing, China.

Arjan D. van Zuilen, Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands.

Stein I. Hallan, Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science Technology, Trondheim and Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, St Olav University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway.

Csaba P. Kovesdy, Memphis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Memphis, TN and University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN.

Mark Woodward, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, The George Institute for Global Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia and The George Institute for Global Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom.

Adeera Levin, BC Provincial Renal Agency and University of British Columbia, Canada.

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney International Supplements. 2013;3(1): 1–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):260–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bello AK, Levin A, Tonelli M, et al. Assessment of Global Kidney Health Care Status. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1864–1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;382(9887):158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin A, Tonelli M, Bonventre J, et al. Global kidney health 2017 and beyond: a roadmap for closing gaps in care, research, and policy. Lancet. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astor B, Muntner P, Levin A, Eustace J, Coresh J. Association of kidney function with anemia: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994). Arch. Intern. Med. 2002;162(12):1401–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eustace JA, Astor B, Muntner PM, Ikizler TA, Coresh J. Prevalence of acidosis and inflammation and their association with low serum albumin in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2004;65(3):1031–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muntner P, Jones TM, Hyre AD, et al. Association of serum intact parathyroid hormone with lower estimated glomerular filtration rate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(1):186–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inker LA, Coresh J, Levey AS, Tonelli M, Muntner P. Estimated GFR, albuminuria, and complications of chronic kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011;22(12):2322–2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viswanathan G, Sarnak MJ, Tighiouart H, Muntner P, Inker LA. The association of chronic kidney disease complications by albuminuria and glomerular filtration rate: a cross-sectional analysis. Clin Nephrol. 2013;80(1):29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita K, Ballew SH, Astor BC, et al. Cohort Profile: The Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:1660–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsushita K, Mahmoodi BK, Woodward M, et al. Comparison of risk prediction using the CKD-EPI equation and the MDRD study equation for estimated glomerular filtration rate. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1941–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WG, Bruns DE, Hortin GL, et al. Current issues in measurement and reporting of urinary albumin excretion. Clin Chem. 2009;55(1):24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inker LA, Levey AS, Pandya K, Stoycheff N, Okparavero A, Greene T. Early change in proteinuria as a surrogate end point for kidney disease progression: an individual patient meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(1):74–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 1968;405:5–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Blood Pressure Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Blood Pressure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2012;2(5):337–414. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.