Abstract

Evidence is accumulating that the main chronic diseases of aging Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) share common pathophysiological mechanisms. This study aimed at applying systems biology approaches to increase the knowledge of the shared molecular pathways underpinnings of AD and T2DM. We analysed transcriptomic data of post-mortem AD and T2DM human brains to obtain disease signatures of AD and T2DM and combined them with protein-protein interaction information to construct two disease-specific networks. The overlapping AD/T2DM network proteins were then used to extract the most representative Gene Ontology biological process terms. The expression of genes identified as relevant was studied in two AD models, 3xTg-AD and ApoE3/ApoE4 targeted replacement mice. The present transcriptomic data analysis revealed a principal role for autophagy in the molecular basis of both AD and T2DM. Our experimental validation in mouse AD models confirmed the role of autophagy-related genes. Among modulated genes, Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1B, Autophagy Related 16-Like 2, and insulin were highlighted. In conclusion, the present investigation revealed autophagy as the central dys-regulated pathway in highly co-morbid diseases such as AD and T2DM allowing the identification of specific genes potentially involved in disease pathophysiology which could become novel targets for therapeutic intervention.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia and it is characterized by histopathological, molecular, and biochemical abnormalities, including cell loss; abundant neurofibrillary tangles; dystrophic neurites; amyloid-β (APP-Aβ) deposits; impaired energy metabolism; mitochondrial dysfunction; chronic oxidative stress; and DNA damage1.

While the cause of AD remains unknown, several risk factors have been identified that may provide insight into the fundamentals of AD pathogenesis. Among them, aging is by far the most important risk factor, but type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is also a known risk factor for AD. Compelling evidence supports the notion that insulin deficiency and insulin resistance are involved in AD-type neurodegeneration; (1) increased risk of developing mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, or AD in individuals with T2DM2,3 (2) progressive brain insulin resistance, insulin deficiency in AD4–7; (3) cognitive impairment in experimental animal models of T2DM8 (4) improved cognitive performance in experimental models and humans with AD or MCI after treatment with insulin sensitizer agents or intranasal insulin9–16 (5) shared molecular, biochemical, and mechanistic abnormalities in T2DM and AD2,17,18. Based on the concept that AD may represent a brain-specific form of diabetes mellitus, the term “type-3 diabetes” indicating AD was coined4,19.

Cross-disease therapeutic potential of these major chronic diseases of aging is already showing promise as intranasal insulin improves cognitive performances in patients with mild cognitive impairment and AD20. Moreover, new generation anti-diabetic incretin drugs show efficacy in AD animal models21,22, and are presently being evaluated in clinical trials in patients, as well as thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agents23.

Systems biology has been paving the way to the exploration of complex associations of diseases and, thus, to the inference of the pathogenic mechanism of a particular disease by considering disease-related components in a large-scale network. Thus, in the present study we set to determine the similarities and differences in the molecular mechanistic networks underlying brain T2DM pathophysiology in AD and in neurologically normal subjects. A novel approach to the analysis of existing transcriptional data-sets of T2DM and AD patient cerebral cortex material was used, with a major application to human brain networks (Fig. 1). This integration of knowledge highlighted a central role for the autophagy pathway in the mechanisms underlying the commonalities in AD and T2DM, which was further analyzed in animal models of disease. We focus our investigation initially on human diseased subjects considering the limitation of animal models of CNS-related diseases in representing all aspects of a complex multifactorial disease, but we were also able to confirm and investigate further the molecular mechanism found to be altered in two models that represent different aspects of the genetic of AD.

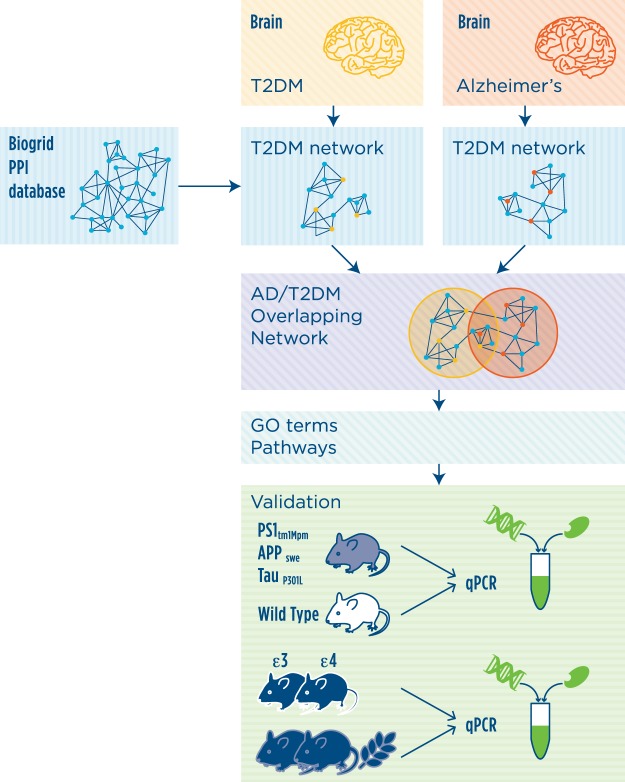

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of experimental design. The transcriptional signature associated to AD or T2DM was extracted from transcriptomic data of post-mortem cerebral cortices of AD or T2DM affected individuals as compared to controls. Network analysis was then performed with the reference protein-protein interaction (PPI) network derived from Biogrid data. The functionality analysis of the networks was then performed by testing over-represented Gene Ontology biological process terms and pathways. The relevance of autophagy, the most significant pathway identified by network analysis, was further validated in two animal models of AD.

These findings contribute to opening new ways to tackle some of the more important challenges to combat these disorders.

Results

Network analysis of human transcriptomic data

We extracted the following transcriptomic profiles from the GSE36980 dataset: T2DM controls (n = 20), non-T2DM controls (n = 12), T2DM AD (n = 6), and non-T2DM AD subjects (n = 19). Having obtained four well defined groups representing all combinations of our two phenotypes of interest (T2DM and AD), we sought to characterize them transcriptionally in a highly specific way, in the sense of identifying genes whose expression changes were most related to a single phenotype. We derived the set of fold changes profiles by dividing each original profile by a reference one obtained as the genewise average across the whole dataset.

We then applied a rank-based signature extraction algorithm that characterizes each sample by the list of genes with the most extremes fold changes in the corresponding profile. As part of the algorithm, we measured the degree of similarity between each pair of signatures, and we used the resulting similarity matrix to plot a map of the samples and their relative similarity (Supplementary Figure 1). We found that it was necessary to perform a preliminary feature selection step in order to preferentially steer the algorithm toward brain transcriptional alterations that have some association to T2DM and AD, reducing the influence of other factors such age, sex, tissue of origin. We empirically determined that the best results in terms of separation of the groups were obtained by filtering genes whose fold changes showed a sufficiently large difference between average T2DM and non-T2DM values in either the AD or the non-AD cohort (t-test, p-value < 0.01). Despite having based the selection on T2DM status, we noticed that the selected features (N = 483) included a sufficient number of genes differentially expressed between AD and non-AD profiles (N = 103 out of 483).

Having identified list of signature genes capable of separating each of the four group from the others to a satisfactory degree (Supplementary Figure 1), we proceeded to select two of the groups (T2DM controls and non-T2DM AD subjects) for a more detailed analysis. The consensus transcriptional signature for each of these two groups was extracted using an algorithm that summarizes the level of popularity of signature genes across the signatures of that group.

The resulting T2DM transcriptional signature consisted of 126 genes, while the AD signature was composed of 108 genes (Supplementary Table S1).

The transcriptional signatures were computed to be the shortest possible while maintaining high classification accuracy. Therefore, to expand the comprehension of the pathophysiological processes underlying the investigated diseases, we enriched the lists of signature genes by means of a network analysis technique leveraging available knowledge on human protein-protein interactions. Following enrichment, the AD network included 620 genes and 889 interactions, while the T2DM network included 641 genes and 869 interactions. Hence, we obtained an overlapping AD/T2DM network formed by 158 genes in common between the AD and T2DM networks (Supplementary Table S1). The overlapping AD/T2DM network is highly enriched in genes supporting the common neurobiological dysregulations of the two diseases.

Functional annotation analysis

The functionality analysis of the networks was then performed by testing over-represented Gene Ontology biological process terms and pathways of the signature, the overlapping genes between signatures, AD and T2DM networks separately and overlapping genes between these two networks.

The analysis of the AD network GO biological processes terms revealed a predominant role of Neurotrophin and Notch signalling, apoptosis, autophagy and inflammatory pathways (Supplementary Table 1). Similar findings were confirmed by the pathway analysis, with the addition of Wnt, estrogen, prolactin and FoxO signalling pathways (Table 1).

Table 1.

Results of the pathway analysis of the AD network. In bold the pathways in common between the AD and T2DM networks.

| p value | q value | Pathway | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6.75E-13 | 1.40E-11 | Ubiquitin mediated proteolysis - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 5.04E-10 | 8.57E-09 | NOTCH1 Intracellular Domain Regulates Transcription | Reactome |

| 2.06E-09 | 3.24E-08 | Adaptive Immune System | Reactome |

| 7.35E-08 | 7.91E-07 | Signaling by NOTCH | Reactome |

| 2.91E-07 | 2.95E-06 | HDACs deacetylate histones | Reactome |

| 3.16E-06 | 2.58E-05 | FoxO signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 3.20E-05 | 0.00022031 | Macroautophagy | Reactome |

| 4.16E-05 | 0.00027593 | Regulation of autophagy - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 4.57E-05 | 0.00028679 | Oxidative Stress Induced Senescence | Reactome |

| 0.0005419 | 0.00254964 | Activation of NF-kappaB in B cells | Reactome |

| 0.0006026 | 0.0027859 | Wnt signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0007463 | 0.00336957 | Notch signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0009247 | 0.004095 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0018044 | 0.00728684 | Amyloids | Reactome |

| 0.0018537 | 0.00745715 | Cytokine Signaling in Immune system | Reactome |

| 0.0022241 | 0.00861836 | Rap1 signalling | Reactome |

| 0.002268 | 0.00872443 | Estrogen signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0029791 | 0.01113449 | Chemokine signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0032317 | 0.01194569 | Prolactin signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.0050714 | 0.01686197 | Regulation of lipid metabolism by Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) | Reactome |

| 0.0055406 | 0.01830646 | Signaling by Interleukins | Reactome |

| 0.0079904 | 0.02504608 | Intrinsic Pathway for Apoptosis | Reactome |

| 0.0088872 | 0.02728608 | Interferon Signaling | Reactome |

The T2DM network was characterized by apoptosis and several metabolic-associated processes including lipid, carbohydrate and ketone metabolism, cholesterol homeostasis, and autophagy. Moreover, in the T2DM network, signalling pathways such as neurotrophin, Notch and Wnt were enriched and, as for the AD network, inflammatory pathways were highlighted (Supplementary Table 1). Pathway analysis was in line with the GO terms investigation, with the addition of pathways related to insulin, leptin, prolactin, mTOR, ephrin signalling, and circadian rhythmicity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the pathway analysis of the T2DM network. In blue the pathways in common between the AD and T2DM networks.

| p value | q value | Pathway | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.74E-15 | 6.64E-13 | Thyroid hormone signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 1.17E-13 | 1.38E-11 | mechanism of gene regulation by peroxisome proliferators via ppara | BioCarta |

| 2.79E-11 | 2.29E-09 | FoxO signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 1.28E-10 | 8.49E-09 | Macroautophagy | Reactome |

| 1.44E-10 | 9.05E-09 | NOTCH1 Intracellular Domain Regulates Transcription | Reactome |

| 3.31E-09 | 1.14E-07 | Beta-catenin phosphorylation cascade | Reactome |

| 4.50E-09 | 1.41E-07 | Regulation of lipid metabolism by Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) | Reactome |

| 6.66E-09 | 1.97E-07 | Circadian Clock | Reactome |

| 1.15E-08 | 2.98E-07 | Signaling by Interleukins | Reactome |

| 1.71E-08 | 4.05E-07 | Circadian rhythm - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 2.04E-08 | 4.17E-07 | Signaling by Type 1 Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF1R) | Reactome |

| 2.47E-08 | 4.77E-07 | AMPK signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 3.91E-08 | 7.06E-07 | IRS-mediated signalling | Reactome |

| 5.72E-08 | 9.46E-07 | Insulin receptor signalling cascade | Reactome |

| 2.19E-07 | 2.72E-06 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 3.70E-07 | 4.19E-06 | Signaling by Wnt | Reactome |

| 9.83E-07 | 9.35E-06 | Signaling by NOTCH | Reactome |

| 2.77E-06 | 2.46E-05 | Signaling by Leptin | Reactome |

| 4.19E-06 | 3.46E-05 | Adipocytokine signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 4.89E-06 | 3.88E-05 | Fatty acid, triacylglycerol, and ketone body metabolism | Reactome |

| 2.94E-05 | 0.000165458 | Sphingolipid signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000475166 | 0.001648377 | Wnt signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000531621 | 0.001820503 | mTOR signalling | Reactome |

| 0.001563324 | 0.004637717 | Cellular Senescence | Reactome |

| 0.001694211 | 0.004998158 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.003142557 | 0.008559651 | EPH-Ephrin signaling | Reactome |

| 0.004303806 | 0.011317415 | Interleukin-6 signaling | Reactome |

| 0.006542263 | 0.015980527 | Insulin signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.008386082 | 0.019505104 | Prolactin receptor signaling | Reactome |

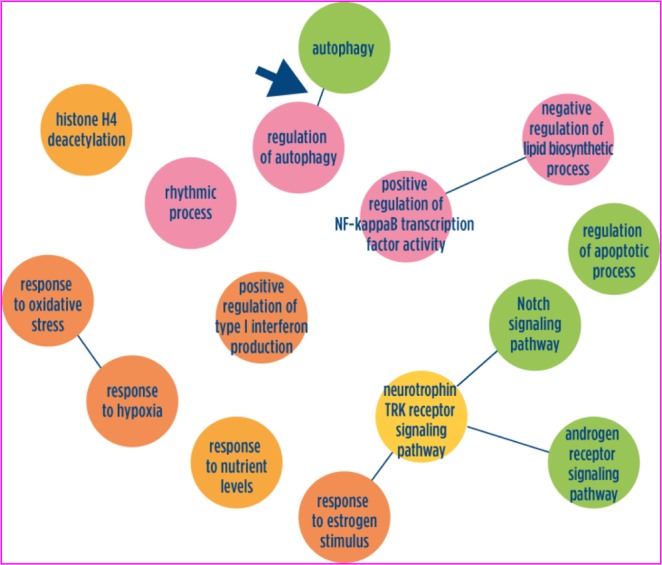

In the overlapping AD/T2DM network, a strong involvement of autophagy was further confirmed (Figs 2 and 3). In addition, apoptosis and Notch signalling were strongly involved together with oxidative stress and inflammation functions (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1). Functional Pathway enrichment analysis confirmed the GO terms findings and indicated a role also for FoxO, Wnt, estrogen, and leptin signalling pathways (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Schematic graphs of over-represented Gene Ontology biological process terms in AD/T2DM overlapping network. Over-represented GO terms in the AD/T2DM overlapping network. GO terms are represented as nodes, and the strongest GO term pair-wise similarities are designated as edges in the graph. GO terms are grouped to illustrate the main biological processes characterizing the overlapping AD/T2DM networks. Complete lists of GO terms can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

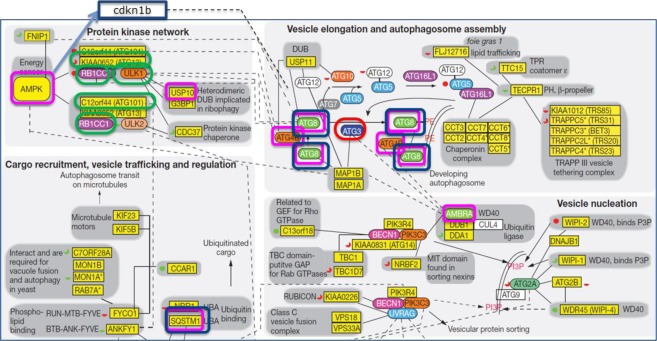

Figure 3.

Integration of AD/T2DM overlapping network with human autophagy network (modified from Behrends, C., Sowa, M. E., Gygi, S. P. & Harper, J. W. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature 466, 68–76 (2010)). AD, T2DM and AD/T2DM genes are charted in the functional integration of the autophagy interaction network. In blue are shown the genes validated in the two animal models of AD, in red the genes found in the AD network, in green the genes located in the T2Dm network and in pink the AD/T2DM genes.

Table 3.

Results of the pathway analysis of the AD/T2DM overlapping network.

| 2.93E-09 | 5.29E-08 | Signaling by NOTCH | Reactome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.90E-09 | 6.69E-08 | FoxO signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 7.18E-09 | 1.17E-07 | Thyroid hormone signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 1.14E-07 | 1.53E-06 | Macroautophagy | Reactome |

| 1.59E-07 | 2.05E-06 | Cellular Senescence | Reactome |

| 1.15E-06 | 1.27E-05 | Signaling by Wnt | Reactome |

| 7.82E-06 | 6.79E-05 | Regulation of autophagy - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 4.92E-05 | 0.000301243 | Wnt signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 6.25E-05 | 0.000360329 | Notch signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000211397 | 0.0010285 | Estrogen signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000262185 | 0.001207105 | Regulation of lipid metabolism by Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) | Reactome |

| 0.000293703 | 0.001343203 | Signaling by Interleukins | Reactome |

| 0.000610253 | 0.002568306 | Oxidative Stress Induced Senescence | Reactome |

| 0.000693496 | 0.002848733 | Central carbon metabolism in cancer - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000864821 | 0.00342929 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway - Homo sapiens (human) | KEGG |

| 0.000990053 | 0.003773201 | Signalling by NGF | Reactome |

| 0.003406249 | 0.009736195 | Innate Immune System | Reactome |

| 0.009010442 | 0.018960624 | Signaling by Leptin | Reactome |

The main functional annotation analysis results of the two networks separately and of the overlapping AD/T2DM network are summarized in Figs 2 and 3, which highlights the central role discovered for the autophagic pathway.

Validation in animal models of disease

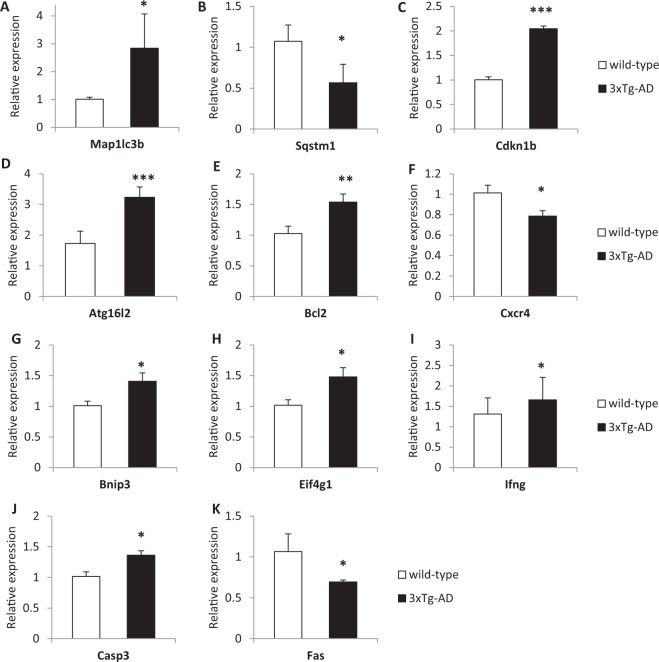

Network analyses indicated that autophagy could be among the biological mechanisms underpinning both AD and T2DM, thus we performed a focused gene expression investigation in two animal models of Alzheimer’s disease with the aim of expanding the knowledge of the roles played by specific genes belonging to this pathway in the pathophysiology of this neurodegenerative disease. In the pre-frontal cortex of 3xTg-AD mice, a differential expression was detected for 11 genes involved in the autophagic pathway (Fig. 4, Table 4). The evidence of dysregulation was particularly strong for Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b) and for Autophagy Related 16-Like 2 (Atg16l2), which both showed much higher expression levels in 3xTg-AD mice with respect to wild-type controls (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Altered mRNA expression levels autophagy-related genes in the pre-frontal cortex of 3xTg-AD (PS1tm1Mpm, human APPswe and TauP301L) homozygus mice with respect to wild-type mice. (A) Map1lc3b; (B) Sqstm1; (C) Cdkn1b; (D) Atg16l2; (E) Bcl2; (F) Cxcr4; (G) Bnip3; (H) Eif4g1; (I) Ifng; (J) Casp3; (K) Fas. ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Summary table of the gene expression results in the prefrontal cortex of two AD animal models in comparison with AD and T2DM networks. + = p-value ≤ 0.05; + + corrected p-value ≤ 0.05.

| Gene symbol | In AD or T2DM network | 3xTG vs. wild type | ApoE3 vs. ApoE4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATG3 | AD | + | |

| GABARAPL2 | AD/T2DM | + | |

| MAP1LC3B | AD/T2DM | + | + |

| SQSTM1 | AD/T2DM | + | |

| Cdkn1b | ++ | ||

| Atg16l2 | ++ | ||

| Bcl2 | + | ||

| Cxcr4 | + | ||

| Bnip3 | + | ||

| Eif4g1 | + | ||

| Ifng | + | + | |

| Casp3 | + | ||

| Fas | + | ||

| Tnf | + | ||

| Ins2 | ++ | ||

| Gaa | + | ||

| Ctss | + | ||

| Dram1 | + | ||

| Atg7 | + | ||

| B2m | + | ||

| Rps6kb1 | + | ||

| Ctsb | + | ||

| Ctsd | + |

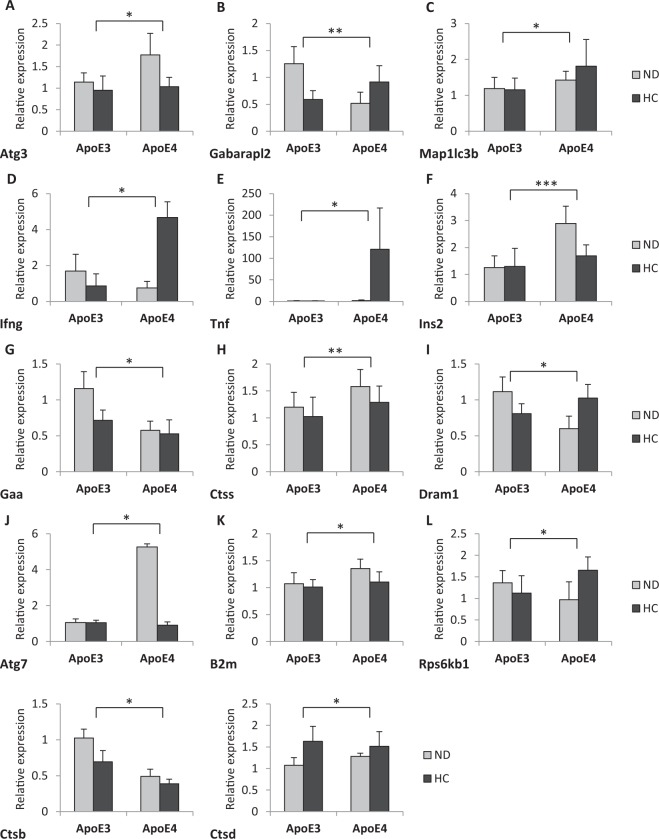

In the ApoE4 targeted replacement (TR) mice, 14 genes involved in the autophagic process showed altered expression as compared to the ApoE3 mice (Fig. 5, Table 4). Among those, higher insulin gene expression in the ApoE4 genotype is highlighted (Fig. 5). In addition, mice belonging to each genotype were fed for six months with a high carbohydrate diet to stress the metabolism or with a normal diet and the alteration in gene expression was assessed. The results showed an overall modest impact of the high carbohydrate diet. In particular, Fas gene expression was up-regulated in the high carbohydrate diet vs. normal diet in the ApoE3 genotype, whereas Dram1 was strongly expressed in the high carbohydrate diet vs. normal diet in the ApoE4 genotype.

Figure 5.

Altered mRNA expression levels autophagy-related genes in the pre-frontal cortex of hApoE TR mice expressing human ApoE3 or ApoE4 fed with either normal diet (ND) or high carbohydrate diet (HC). (A) Atg3; (B) Gabarapl2; (C) Map1lc3b (D) Ifng; (E) Tnf; (F) Ins2; (G) Gaa; (H) Ctss; (I) Dram1; (J) Atg7; (K) B2m; (L) Rps6kb1; (M) Ctsb; (N) Ctsd. ***p < 0.001;**p < 0.05; *p < 0.05.

Discussion

There is an ongoing debate about the role of T2DM in contributing to AD pathogenesis. Epidemiological and biological evidence strongly suggests the importance of T2DM components in AD pathology4,6, thus in the present study we investigated the molecular basis of this comorbidity applying a systems biology approach to transcriptomic data of human post mortem brains of AD or T2DM affected individuals.

AD and T2DM specific networks were built using a two-step workflow consisting in the identification of transcriptomic signatures followed by functional analysis based on network analysis. This approach allowed the identification of the molecular mechanisms underlying T2DM and AD and the commonalities and differences between the two.

AD network pathway enrichment confirmed previous findings supporting a role for inflammation in the pathophysiology of the disease. In the onset of inflammatory process the overexpression of specific interleukins such as (IL)-1 plays a relevant role producing many reactions in a loop that cause dysfunction and neuronal death24. In our AD network, but also in the T2DM network, we found the interleukin 7 receptor (IL7R). This interleukin receptor has been mostly known as a key regulator of T lymphocyte development and homeostasis, but recently it has been associated also to obesity and insulin resistance25, suggesting that this could possibly represent the molecular link between inflammatory pathways and metabolic alterations. Immune response and regulation of metabolism are highly integrated processes, dysfunction of which can lead to a cluster of chronic metabolic disorders including insulin resistance.

The analysis of the AD/T2DM overlapping network showed that the autophagic pathway is a crucial component in the pathophysiology of both diseases. Autophagy is a major catabolic pathway that allows recycling of cellular constituents into bioenergetic and biosynthetic materials for maintenance of homeostasis. In particular, neuronal autophagy is essential for synaptic plasticity, anti-inflammatory function in glial cells, oligodendrocyte development, and myelination process26,27. Indeed, a wealth of recent data indicated that autophagy plays a major role in the pathogenesis of AD28,29. These findings are particularly relevant since our open approach was not based on a pre-defined hypothesis. Dys-regulations in autophagy-related genes and proteins has been demonstrated in animal models of disease and in patients30; moreover, genetic studies reported associations between several autophagy genes and AD31. It has been proposed that the molecular mechanism underlying the association is based on the function of autophagy as a major pathway for the clearance and degradation of aggregated and toxic proteins29,32. Moreover, impaired mitophagy has also been associated to AD; mitophagy is the process by which cells detect and remove damaged mitochondria by an authophagic mechanism. Thus, impaired mitophagy leads to reduced cellular energy levels, increased reactive oxygen species, and impaired neuroplasticity33,34. It is likely that both autophagic removal of abnormal proteins and mitophagy-dependent elimination of damaged mitochondria are needed to prevent the development of AD. Consequently, although many components still need to be elucidated, the identification of the autophagic pathway as a fundamental component of AD aetiology is indicating a new direction for the discovery of potential targets for therapeutic intervention which could generate disease modifying medicines32,35,36, also addressing the transcriptional control of the process32,37. A number of links also exist between T2DM and autophagy, since the latter is the main physiological mechanism activated by energy restriction and it could have relevance in pancreatic β-cell homeostasis. Available evidence suggests that autophagy deficiency in pancreatic β cells could influence the progression from obesity to T2DM and it could contribute to insulin resistance in target organs38–40. The principal players include the central function exerted by AMPK, which is both a main regulator of energy metabolism and autophagy and a target of antidiabetic agents41; the autophagy-regulator mTOR pathway, which is involved in both glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance42; mitochondria dysfunction43,44; and the modulation of inflammation and immune cell function45. Among the genes highlighted in the network analysis, four were also confirmed in the Alzheimer’s disease animal models: ATG3, GABARAPL2 (ATG8), MAP1LC3B, and SQSTM1. As shown in Fig. 5, two of them GABARPL2 (ATG8) and MAP1LC3 are strongly involved in vesicle elongation and autophagosome assembly. ATG8 participates in cargo recruitment to the autophagosome46. Also SQSTM1 (p62) a multifunctional scaffolding protein commonly found in ubiquitinated inclusion bodies47 is a crucial protein in vesicle trafficking and regulation. The scaffolding protein p62 recruits autophagic protein substrates to LC3-bound autophagosomal membranes and it is associated with neuropathological inclusions in several neurodegenerative disorders, including AD.

SQSTM1 (p62) immunoreactivity is associated with neurofibrillary tangles and is involved in tau degradation and it has been shown that it regulates Aβ turnover. In addition SQSTM1 (p62) overexpression decreases Aβ by an autophagy-mediated mechanism and it rescues cognitive function and reduces Aβ pathology in APP/PS1 mice, a widely used animal model of AD48. Thus, it may play an essential role in eliminating senescent or damaged proteins and organelles in neurons and in β-cells, thereby protecting these cells from death. Alteration at this stage of sequestration of autophagic cargo, which has been shown to be selective49, could predispose the onset of both diseases. In support of this hypothesis SQSTM1 (p62) and MAP1LC3B are lower in Alzheimer patients carrying the ɛ4/ɛ4 genotype, which is one of the strongest predisposing factors in AD50.

The validation of the role of autophagy-related genes in animal AD models confirmed the importance of this pathway and suggested that specific genes are especially dysregulated in the disease model groups. Among them, Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b) and Autophagy Related 16-Like 2 (Atg16l2) showed higher expression levels in 3xTg-AD mice.

Cdkn1b is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor able to block cell cycle progression into the proliferative stage. In addition to this first-discovered function, subsequent data showed that Cdkn1b is involved in other cellular processes, including autophagy. In particular, Cdkn1b is required to induce autophagy in nutrient-depleted cells through its stabilization mediated by AMPK-mediated phosphorylation51. Cdkn1b ability to promote autophagy by directly increasing autophagy flux with or without nutrient withdrawal was demonstrated by Sun et al.52 in differentiated cardiomyocytes, suggesting that the same could happen in other cell types lacking proliferative capacity such as neurons. However, previous studies have reported increased expression of cell cycle proteins in neurons of AD patients and it has been put forward that neuronal cell cycle re-entry may be involved in AD pathology53. The significance of this process in AD pathology is not clear; it has been proposed that cell cycle proteins in post-mitotic neurons may contribute to DNA repair and neuroplasticity53. Cdkn1b involvement in AD pathology is supported by data showing altered levels in patient-derived lymphoblasts54 and in post-mortem studies55, although in opposite directions. Therefore, our results provide further support to the significance of Cdkn1b, although our data do not allow drawing definite conclusions about the mechanism of its action.

Atg16l2 is a poorly characterised gene and its function in the autophagic pathway is incompletely understood. Atg16-like proteins interact with Atg5 and Atg12 to form a complex, the E3 ligase, which produces LC3 II, a required step in the formation of the autophagosome. While it is established that this function can be accomplished by Atg16l1, its homologue Atg16l2 is reported to be able to form the complex, but it does not seem to participate in autophagosome formation, at least in starvation-induced autophagy56. On the other hand, ATG16L2 altered expression or genetic polymorphisms have been associated to multiple sclerosis57,58, Crohn disease59,60, and systemic lupus erythematosus61, suggesting that this isoform performs a distinctive, critical function in autophagy. Since Atg16l2 can form hetero-oligomers with Atg16l1, it is possible that the presence of Atg16l2 in the complex may modulate the efficiency of autophagy or that Atg16l2 may be involved in a specialised type of autophagy58. In agreement with this notion, Li et al.62 discovered that Atg16l2 interacts with IKKα in pancreatic cells, acting as an adaptor protein and exerting an essential role in autophagy in these cells. The reported associations with autoimmune diseases suggest the possibility that Atg16l2 may also perform a specific function in the regulation of immune responses. In agreement with our data showing increased levels in a model of a neurodegenerative disorder, Sittler et al. detected increased ATG16L2 immunoreactivity in brain regions of Machado‐Joseph disease patients63.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that a systems biology approach can be a powerful tool to identify common pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning AD and T2DM. The analysis of human brain transcriptomic data by identification of transcriptional signatures followed by network expansion and functional annotation analysis revealed that a central role is played by autophagy. The relevance of the autophagic pathways was validated in diseases models, allowing the identification of specific genes bearing a significant contribution to the pathway dysregulation.

Methods

Experimental design

A schematic representation of the study workflow is shown in Fig. 1. A systems biology workflow was applied to the transcriptomic data of AD and T2DM affected subjects. Gene expression data were analysed with a recently developed algorithm for signature-based clustering of expression profiles to devise a transcriptional signature able to discriminate individuals belonging to the disease groups from controls. We identified a transcriptional signature for each of the two diseases, and performed network analysis in order to expand the list of signature genes with the help of protein-protein interactions from the literature. The resulting enlarged list was characterized through functional annotation in the form of gene ontologies and canonical pathways. The AD and T2DM networks and functional annotation results were then compared. The significant role for the autophagic pathway discovered by the system biology approach was then validated by transcriptional analysis of selected genes in two relevant animal models of AD coupled with a metabolic challenge.

Transcriptomic data

The microarray data set was downloaded from the GEO (GSE36980). The original dataset contains gene expression profiles of grey matter from post-mortem brains of AD (n = 16) and non-AD controls (n = 23) donated for the Hisayama study64. For our study we used the profiles for which information on diabetes mellitus status could be derived from the Hokama et al. paper64. The assessment of AD pathology was conducted according to the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) guidelines65 and the Braak stage66. Clinical data related to T2DM or pre-diabetes were collected as described elsewhere67.

Transcriptomic signature identification

The transcriptional signatures have been identified by means of a rank-based classification method previously implemented in the web-tool SCUDO68,69. Briefly, an average expression profile was computed and then each of the 57 profiles considered in this study was divided by it. A preliminary feature selection step was performed, consisting in a pairwise t test (threshold: p-value < 0.01, genes selected were all those appearing in at least one of the two lists resulting from the following two comparisons: i) T2DM vs controls subjects, and ii) AD vs controls subjects). Then our classification method was applied; the method ranks the filtered genes by expressions level separately for each sample, and then it produces a set of subject-specific signatures, where each signature is the list of the first n1 and the last n2 genes in the ranking (n1 and n2 have the same value for all subjects and are parameters of the method). An all-to-all signature comparison was then carried out using a distance metric based on an enrichment score, resulting in a distance matrix that systematically quantifies the degree of similarity between each pair of subjects. The kth percentile of values from the distance matrix was then used to build a map of individuals. The map is in the form of a graph where the nodes correspond to signatures/subjects and the length of a connecting edge encodes the level of similarity between the connected nodes (short edge = high similarity; no edge = negligible similarity). Finally, a consensus gene signature was extracted for each group of subjects, which collected all the genes included in at least one subject-specific signature for that group. The SCUDO method was used to perform a 4-way classification (four groups: T2DM controls, non-T2DM controls, T2DM AD, and non-T2DM AD subjects) with the following parameter values: n1 = 100, n2 = 100, k = 10 i.e. bottom 10% of distances was used to generate the graph. Only two groups were further studied (T2DM controls and non-T2DM AD subjects), and their consensus signatures extracted for further analysis. The consensus signatures for the T2DM and the AD groups included 200 probe names each, which produced two lists of 126 and 108 genes (T2DM and AD, respectively) after the probe name to gene symbol translation. The translation was performed manually using the annotation table for the Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array platform downloaded from GEO.

Network enrichment

The networks of AD and T2DM were extracted from the Biogrid Database70 using the AD or T2DM disease signatures as seed genes and protein-protein interactions for Homo Sapiens. BioGRID is one of the most comprehensive protein interaction databases, containing more than 1,400,000 interactions curated from both high-throughput datasets and individual focused studies. From the raw data from BioGrid, we considered only non-redundant human interactions. Each unique combination of interactors, protein A and protein B, are counted as a single interaction, regardless of directionality, experimental system and publication. The genetic inferred interactions were filtered out to remain only physical interactions. We extracted direct 1-step interactions of the AD and T2DM genes to construct two corresponding networks, AD network and T2DM network. The network of AD consists of 620 genes and 889 interactions and the network of T2DM contains 599 genes and 869 interactions. Both of two networks are not so dense, but rather centralized with some big hub of proteins.

Functional annotation analysis

The gene lists obtained from network enrichment analysis were used to extract the most representative GO biological process terms. For identifying and visualizing enriched GO terms, we used GOrilla and REVIGO tools71,72. Hypergeometric distribution was applied to test GO term enrichment, and an adjusted p-value (FDR) threshold of 0.05 was selected. Pathway analysis was performed using ConsensusPathDB73.

Animals

3xTg-AD (PS1tm1Mpm, human APPswe and TauP301L) homozygous mice74 and the respective C57-derived wild type animals were kindly provided by prof A. Genazzani, University of Eastern Piedmont “Amedeo Avogadro”, Italy. Forty-eight weeks old mice of mixed gender were investigated (n = 6/group). The mice were housed in groups of 4–6 in ventilated cages (Tecniplast, Italia) with lights on from 7.00 am to 7.00 pm, 22 ± 2◦C temperature and 65% humidity with water and food ad libitum.

hApoE TR mice expressing human apoE3 and apoE4 under the control of the murine apoE regulatory sequences and on a C57BL/6 J background, were purchased from Taconic Farms (USA). Colonies of hApoE3 (B6.129P2-Apoetm2(APOE*3)Mae N8) and hApoE4 (B6.129P2-Apoetm3(APOE*4)Mae N8) TR mice were maintained by homozygous breeding75. The pups were weaned at 3 weeks of age and fed for 6 months with either normal diet (ND) (Mucedola s.r.l., Milano, Italy) or high carbohydrate diet (HCD) containing 70% carbohydrates (Mucedola s.r.l.). Adult male mice were selected for the study (n = 6/group).

All experiments were carried out in accordance with Directive 86/609/EEC and approved by the Animal Welfare Committee at the University of Bologna (PROT. n. 15-IX/9). Care was taken to minimize the number of experimental animals and to take measures to limit their suffering.

RNA extraction and retrotranscription

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation under gaseous anesthesia (5% isoflurane in 1 L/min oxygen/nitrous oxide), pre-frontal cortices were dissected and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted by using the Aurum Total RNA Fatty and Fibrous Tissue Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified by UV spectrophotometry in a NanoDrop 2000c UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific); RNA purity was confirmed by a ratio value OD260/OD280 ≥ 2. RNA integrity was verified by 1% agarose electrophoresis. cDNA was synthesized by using the iScript Advanced cDNA synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR reactions by Sybr Green technology were performed in a CFX Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad) with 50 ng cDNA and Sso Advanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix in Autophagy (SAB Target List) H96 plates (Bio-Rad, cat # 10034108) containing primers for the following genes: Actin, Atg3, Atg9b, Bid1, Ctsd, Esr1, Hdac1, Ins2, Nfkb1, Rb1, Tnf, GAPDH, Atg4a, B2m, Bnip3, Ctss, Fadd, Hdac6, Irgm1, Npc1, Rgs19, Tnfsf10, Hprt, Ambra1, Atg4b, Bad, casp3, Cxcr4, fas, Hgs, Lamp1, Pik3c3, Rps6kb1, Trp53, App, Atg4c, Bak1, Casp8, Dapk1, Gaa, Hsp90aa1, Map1lc3a, Pik3cg, Snca, Ulk1, Atg1, Atg4d, Bax, Cdkn1b, Dram1, Gabarap, Hsp90ab1, Map1lc3b, Pik3r4, Sqstm1, Ulk2, Atg12, Atg5, Bcl2, Cdkn2a, Dram2, Gabarapl1, Htt, Mapk14, Prkaa1, Tgfb1, Uvrag, Atg16l1, Atg7, Bcl2l1, Cln3, Eif2ak3, Gabarapl2, Ifng, Mapk8, Pten, Tgm2, Wipi1, Atg16l2, Atg9a, Becn1, Ctsb, Eif4g1, Gusb, Igf1, Mtor, Rab24, Tmem74, Tbp. To provide quantification, a threshold cycle (Ct) number was defined in the early logarithmic phase of the amplification plot and the relative expression of gene transcripts was calculated by the Delta-Delta Ct (DDCt) method and converted to relative expression ratio (2-DDCt) for statistical analysis76. All data were normalized to the geometric average of the endogenous reference genes glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), Actin (Act), and TATA box binding protein (Tbp) expression77. A dissociation curve was built in the 60–95 °C range to evaluate amplification product specificity.

Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data

The quantitative real-time PCR data was processed in R using the RankProd package78. The RP function from the package was used with its default values with n = 10000 permutations for computing the empirical distributions. RankProduct is a rank-based method capable of identifying differentially expressed genes with high sensitivity even in the case of a modest number of profiles. Moreover, being based on ranks the method makes no assumptions on the distribution of expression values, and it is robust to real-time PCR normalization errors.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a University of Bologna grant to L Carboni (RFO2014) and by the National Research Foundation of Luxembourg (AFR 9139104) to T.P. Nguyen. We thank prof. F. Licastro and dr. E. Porcellini for helpful discussion about gene expression experiments.

Author Contributions

L. Caberlotto conceived and designed the study; L. Caberlotto, M.L., T.-P.N. and C.P. performed bioinformatics analyses; R.R., S.M. and A.C.M. performed in-vivo experiments in the ApoE3/4 model; G.S. and F.M. carried out in-vivo experiments in the 3xTg-AD model; L. Carboni performed gene expression studies; M.L. carried out statistical analyses. M.C. contributed to data analysis. L. Caberlotto and L. Carboni wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to writing the paper, read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-39828-5.

References

- 1.Masters CL, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015;1:15056. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquier F, Boulogne A, Leys D, Fontaine P. Diabetes mellitus and dementia. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:403–14. doi: 10.1016/S1262-3636(07)70298-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verdelho A, et al. Differential impact of cerebral white matter changes, diabetes, hypertension and stroke on cognitive performance among non-disabled elderly. The LADIS study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2007;78:1325–30. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.110361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steen E, et al. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease–is this type 3 diabetes? J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2005;7:63–80. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-7107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivera EJ, et al. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and function deteriorate with progression of Alzheimer’s disease: link to brain reductions in acetylcholine. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2005;8:247–68. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2005-8304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craft S. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: potential mechanisms and implications for treatment. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:147–52. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez-Rodriguez P, et al. Tau hyperphosphorylation induces oligomeric insulin accumulation and insulin resistance in neurons. Brain. 2017;140:3269–3285. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biessels GJ, Reagan LP. Hippocampal insulin resistance and cognitive dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:660–671. doi: 10.1038/nrn4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de la Monte SM, Tong M, Lester-Coll N, Plater M, Wands JR. Therapeutic rescue of neurodegeneration in experimental type 3 diabetes: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2006;10:89–109. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2006-10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haan MN. Therapy Insight: type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006;2:159–66. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landreth G. PPARgamma agonists as new therapeutic agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2006;199:245–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landreth G. Therapeutic use of agonists of the nuclear receptor PPARgamma in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:159–64. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen WA, et al. Rosiglitazone attenuates learning and memory deficits in Tg2576 Alzheimer mice. Exp. Neurol. 2006;199:265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reger MA, et al. Effects of intranasal insulin on cognition in memory-impaired older adults: modulation by APOE genotype. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:451–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reger MA, et al. Intranasal insulin improves cognition and modulates beta-amyloid in early AD. Neurology. 2008;70:440–8. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000265401.62434.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson GS, et al. Insulin effects on CSF norepinephrine and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2006;27:38–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchesini, G. & Marzocchi, R. Metabolic syndrome and NASH. Clin. Liver Dis. 11, 105–17, ix (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Nicolls MR. The clinical and biological relationship between Type II diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2004;1:47–54. doi: 10.2174/1567205043480555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De la Monte SM. Type 3 diabetes is sporadic Alzheimer-s disease: Mini-review. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:1954–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman, C. D., Schiöth, H. B., Grillo, C. A. & Benedict, C. Intranasal insulin in Alzheimer’s disease: Food for thought. Neuropharmacology 1–6, 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.11.037 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Duarte AI, et al. Crosstalk between diabetes and brain: glucagon-like peptide-1 mimetics as a promising therapy against neurodegeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1832:527–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Candeias EM. Gut-brain connection: The neuroprotective effects of the anti-diabetic drug liraglutide. World J. Diabetes. 2015;6:807. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v6.i6.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng H, Shang Y, Jiang L, Shi TL, Wang L. The peroxisome proliferators activated receptor-gamma agonists as therapeutics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Neurosci. 2016;126:299–307. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2015.1015722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubio-Perez JM, Morillas-Ruiz JM, Rubio-Perez JM, Morillas-Ruiz JM. A Review: Inflammatory Process in Alzheimer’s Disease, Role of Cytokines. Sci. World J. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.1100/2012/756357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee M, Song SJ, Choi M-S, Yu R, Park T. IL-7 receptor deletion ameliorates diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance in mice. Diabetologia. 2015;58:2361–70. doi: 10.1007/s00125-015-3684-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kesidou E, Lagoudaki R, Touloumi O, Poulatsidou K-N, Simeonidou C. Autophagy and neurodegenerative disorders. Neural Regen. Res. 2013;8:2275–83. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.24.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J-A. Neuronal autophagy: a housekeeper or a fighter in neuronal cell survival? Exp. Neurobiol. 2012;21:1–8. doi: 10.5607/en.2012.21.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frake RA, Ricketts T, Menzies FM, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagy and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:65–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI73944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Liu Y, Sun M. Autophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017;37:377–388. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0386-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whyte LS, Lau AA, Hemsley KM, Hopwood JJ, Sargeant TJ. Endo-lysosomal and autophagic dysfunction: a driving factor in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Neurochem. 2017;140:703–717. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Menzies FM, Fleming A, Rubinsztein DC. Compromised autophagy and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015;16:345–357. doi: 10.1038/nrn3961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Menzies FM, et al. Autophagy and Neurodegeneration: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Neuron. 2017;93:1015–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr JS, et al. Mitophagy and Alzheimer’s Disease: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Correia SC, Perry G, Moreira PI. Mitochondrial traffic jams in Alzheimer’s disease - pinpointing the roadblocks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis. 2016;1862:1909–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maiese, K. Targeting molecules to medicine with mTOR, autophagy and neurodegenerative disorders. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1245–1266, 10.1111/bcp.12804 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Harris H, Rubinsztein DC. Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012;8:108–117. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martini-Stoica H, Xu Y, Ballabio A, Zheng H. The Autophagy-Lysosomal Pathway in Neurodegeneration: A TFEB Perspective. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:221–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim KH, Lee MS. Autophagy - A key player in cellular and body metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014;10:322–337. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gonzalez CD, et al. The emerging role of autophagy in the pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus. Autophagy. 2011;7:2–11. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.1.13044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen ZF, et al. The double-edged effect of autophagy in pancreatic beta cells and diabetes. Autophagy. 2011;7:12–16. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.1.13607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herzig S, Shaw RJ. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017;19:121–135. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell. 2017;168:960–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarparanta J, García-Macia M, Singh R. Autophagy and Mitochondria in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 2017;13:352–369. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666160217122530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Correia SC, et al. Insulin signaling, glucose metabolism and mitochondria: Major players in Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes interrelation. Brain Res. 2012;1441:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stienstra R, et al. Autophagy in adipose tissue and the beta cell: Implications for obesity and diabetes. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1505–1516. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3255-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weidberg H, Shvets E, Elazar Z. Biogenesis and cargo selectivity of autophagosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011;80:125–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052709-094552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Komatsu, M., Kominami, E. & Tanaka, K. Autophagy and neurodegeneration. Autophagy2, 315–7 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Caccamo A, Ferreira E, Branca C, Oddo S. p62 improves AD-like pathology by increasing autophagy. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:865–873. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 49.Kirkin V, McEwan DG, Novak I, Dikic I. A Role for Ubiquitin in Selective Autophagy. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parcon PA, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 inhibits autophagy gene products through direct, specific binding to CLEAR motifs. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang J, et al. The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27kip1phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007;9:218–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun X, et al. P27 protein protects metabolically stressed cardiomyocytes from apoptosis by promoting autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:16924–16935. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.542795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Leeuwen LAG, Hoozemans JJM. Physiological and pathophysiological functions of cell cycle proteins in post-mitotic neurons: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;129:511–525. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1382-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muñoz Ú, Bartolomé F, Bermejo F, Martín-Requero Á. Enhanced proteasome-dependent degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27kip1 in immortalized lymphocytes from Alzheimer’s dementia patients. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;29:1474–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogawa O, et al. Increased p27, an essential component of cell cycle control, in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2003;2:105–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ishibashi K, et al. Atg16L2, a novel isoform of mammalian Atg16L that is not essential for canonical autophagy despite forming an Atg12-5-16L2 complex. Autophagy. 2011;7:1500–1513. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.12.18025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Igci M, et al. Gene expression profiles of autophagy-related genes in multiple sclerosis. Gene. 2016;588:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yin L, et al. Autophagy-related gene16L2, a potential serum biomarker of multiple sclerosis evaluated by bead-based proteomic technology. Neurosci. Lett. 2014;562:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma, T., Wu, S., Yan, W., Xie, R. & Zhou, C. A functional variant of ATG16L2 is associated with Crohn’s disease in the Chinese population. Colorectal Dis. 420–426, 10.1111/codi.13507 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Yang SK, et al. Genome-wide association study of Crohn’s disease in Koreans revealed three new susceptibility loci and common attributes of genetic susceptibility across ethnic populations. Gut. 2014;63:80–87. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lessard CJ, et al. Identification of a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Risk Locus Spanning ATG16L2, FCHSD2, and P2RY2 in Koreans. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1197–1209. doi: 10.1002/art.39548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li N, et al. Loss of acinar cell IKKα triggers spontaneous pancreatitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:2231–2243. doi: 10.1172/JCI64498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sittler A, et al. Deregulation of autophagy in postmortem brains of Machado-Joseph disease patients. Neuropathology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/neup.12433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hokama M, et al. Altered expression of diabetes-related genes in Alzheimer’s disease brains: The Hisayama study. Cereb. Cortex. 2014;24:2476–2488. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mirra SS, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86. doi: 10.1212/WNL.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ohara T, et al. Apolipoprotein genotype for prediction of Alzheimer’s disease in older Japanese: the Hisayama Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2011;59:1074–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lauria M, Moyseos P, Priami C. SCUDO: a tool for signature-based clustering of expression profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W188–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lauria M. Rank-based transcriptional signatures. Syst. Biomed. 2013;1:228–239. doi: 10.4161/sysb.25982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chatr-Aryamontri A, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D369–D379. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, Šmuc T. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: a tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kamburov A, Stelzl U, Lehrach H, Herwig R. The ConsensusPathDB interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D793–800. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Oddo, S. et al. Triple-Transgenic Model of Alzheimer’s Disease with Plaques and Tangles: Intracellular ANL and Synaptic Dysfunction. 39, 409–421 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Maioli S, et al. Combination of apolipoprotein E4 and high carbohydrate diet reduces hippocampal BDNF and arc levels and impairs memory in young mice. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2012;32:341–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vandesompele J, et al. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hong F, et al. RankProd: A bioconductor package for detecting differentially expressed genes in meta-analysis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2825–2827. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.