Abstract

Abnormal cortical oscillations are markers of Parkinson's Disease (PD). Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) can modulate brain oscillations and possibly impact on behaviour. Mapping of cortical activity (prevalent oscillatory frequency and topographic scalp distribution) may provide a personalized neurotherapeutic target and guide non-invasive brain stimulation. This is a cross-over, double blinded, randomized trial. Electroencephalogram (EEG) from participants with PD referred to Specialist Clinic, University Hospital, were recorded. TACS frequency and electrode position were individually defined based on statistical comparison of EEG power spectra maps with normative data from our laboratory. Stimulation frequency was set according to the EEG band displaying higher power spectra (with beta excess on EEG map, tACS was set at 4 Hz; with theta excess, tACS was set at 30 Hz). Participants were randomized to tACS or random noise stimulation (RNS), 5 days/week for 2-weeks followed by ad hoc physical therapy. EEG, motor (Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale-motor: UPDRS III), neuropsychological (frontal, executive and memory tests) performance and mood were measured before (T0), after (T1) and 4-weeks after treatment (T2). A linear model with random effects and Wilcoxon test were used to detect differences.

Main results include a reduction of beta rhythm in theta-tACS vs. RNS group at T1 over right sensorimotor area (p = .014) and left parietal area (p = .010) and at T2 over right sensorimotor area (p = .004) and left frontal area (p = .039). Bradykinesia items improved at T1 (p = .002) and T2 (p = .047) compared to T0 in the tACS group. In the tACS group the Montréal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) improved at T2 compared with T1 (p = .049).

Individualized tACS in PD improves motor and cognitive performance. These changes are associated with a reduction of excessive fast EEG oscillations.

Keywords: Neurotherapeutic target, Electroencephalography, Neurophysiology, Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale (UPDRS III), Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS)

Abbreviations: BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II); EEG, electroencephalography; GDI, Gait Dynamic Index; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MCID, minimal clinical important difference; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NIBS, non-invasive brain stimulation; PD, Parkinson's Disease; RNS, random noise stimulation; STAY-Y, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; UPDRS III, Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale-motor; tACS, transcranial alternating current stimulation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; SM, sensorimotor area; L, left; R, right; FFT, fast Fourier Transform; TMT A and B, trail making test, form A and B

Highlights

-

•

Personalized tACS protocols improve motor and cognitive performance in PD.

-

•

Among motor items, bradykinesia improved most.

-

•

Fast cortical oscillations decreased after tACS.

1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is characterized by motor impairment and cognitive decline. Neuronal oscillations play a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of PD. Synchronized neuronal oscillations correlate with distinct behavioral states (Buzsáki and Draguhn, 2011; Engel et al., 2001). A deviation from physiological frequency bands is a hallmark of a wide group of pathologies, namely thalamo-cortical dysrhythmias or oscillopathies (Llinas et al., 1999).

Studies in idiopathic PD and animal models suggests that dopamine depletion induces an excessive synchronization in the beta range (15–30 Hz) in the basal ganglia and associated circuits (Neumann et al., 2017). Beta oscillations in the subthalamic nucleus are coherent with oscillations in ipsilateral sensorimotor (SM), adjacent premotor cortex (Lalo et al., 2008; Marsden et al., 2001), supplementary motor area, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and primary motor cortex in PD (Priori and Lefaucheur, 2007). This pathological synchronization reduces during voluntary movements (Kühn et al., 2005), with L-dopa administration (Brown et al., 2001) and with deep brain stimulation (Kühn et al., 2008). Low frequency theta oscillations (4–7 Hz) have been associated with resting tremor (Hutchison et al., 1997). Cognitive and motor functions have a neurophysiological correlate in beta rhythms (Engel and Fries, 2010; Joundi et al., 2012); the fast pathological neuronal synchronization in PD might be a con-causal factor of motor and cognitive impairments (Eusebio and Brown, 2009; Shimamoto et al., 2013; Stein and Bar-Gad, 2013).

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) is a user-friendly, portable technique, which can modulate cortical activity (Helfrich et al., 2014; Del Felice et al., 2015). TACS provides a low-intensity alternating current with a sinusoidal pattern applied to the scalp. This oscillatory stimulation paradigm is distinct from transcranial direct current stimulation, which is a continuous non-oscillatory current trialed in PD with no clear-cut beneficial motor effects (Elsner et al., 2016). TACS forces the membrane potential to oscillate away from its resting potential towards slightly more depolarized or hyperpolarized states; during the depolarization state, neurons are more likely to fire in response to other neurons – a mechanism called “stochastic resonance” (McDonnell and Abbott, 2009). The eventual effect is that of an increase of neuronal firing time-locked to the frequency of stimulation, defined entrainment. TACS therefore exerts a modulatory but non-dominant influence.

We tested the hypothesis that a non-invasive stimulation, though potentially different from the natural oscillations of the target brain region, could modulate neuronal networks and shift oscillations into a physiological range. We recorded cerebral activity with electroencephalography (EEG) on an individual basis to tailor the stimulation. Theta-tACS was applied if fast frequencies showed a higher spectral frequency power and beta-tACS if slow frequencies showed higher spectral frequency power over the area of major power representation. An active sham [random noise stimulation (RNS)] was used as suggested by a recent consensus statement (Thut et al., 2017). An ad hoc physical rehabilitation program was associated and electroencephalographic and behavioral correlates recorded at baseline, after treatment and at 1-month follow-up to test treatment after-effects.

2. Materials and methods

This is a cross over, double-blinded, randomized trial. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University Hospital (protocol n. 3507/AO/15). Participants provided written informed consent. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.Gov (NCT03221413) and included PD as a model of fast oscillopathy and chronic pain as a model for slow oscillopathy. These are preliminary data from the PD arm. CONSORT guidelines for cross-over trials are still under development (Pandis et al., 2017); we used the standard CONSORT checklist (Supplementary material 1).

2.1. Participants

People with PD were recruited from a Specialist Clinic. Inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of idiopathic PD within the last 5 years (UK Brain Bank criteria, Clarke et al., 2016); stable dose of antiparkinsonian therapy for at least 4 weeks; off-medication motor Hoen and Yahr 1–2. Exclusion criteria were: psychiatric disorder; benzodiazepine treatment; MMSE <23; contraindications to neurostimulation.

A sample size of 15 yields a power >99% to detect a mean of paired differences (Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale-motor [UPDRS] pre- and post-stimulation score difference) of 10 points with significance level of 0.05 using a two-sided paired t-test.

2.2. Motor and neuropsychological evaluations

Motor impairment was measured by the same trained physician experienced with UPDRS, blinded to treatment arm, in an off state. Gait Dynamic Index (GDI) was used to assess gait.

Neuropsychological tests (frontal-executive functions, memory and mood) were administered and scored by a neuropsychologist blinded to the treatment group. Tests are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Neuropsychological assessment.

| Test administered only at T0 | Edinburgh Handedness Inventory |

| Trait Anxiety Inventory | |

| Brief Intelligence Test | |

| Operator administered questionnaires | Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) |

| Trail Making Test (A and B) | |

| Rey-Complex Figure Test (copy and 3′ delayed recall) | |

| Digit-Symbol task | |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised | |

| Phonemic Verbal Fluency task | |

| Self-reported questionnaires | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAY-Y) |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) | |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), short version |

At each time-point parallel versions were used to overcome the risk of learning effects. Presentation order of cognitive tasks was randomized to contrast sequencing biases. For detailed description see Appendix A.

2.3. EEG data acquisition and analysis

Ten minutes of open-eyes resting state EEG signal (32-channels system; BrainAmp 32MRplus, BrainProducts GmbH, Munich, Germany) were acquired using an analogic anti-aliasing band pass-filter at 0.1–1000 Hz and converted from analog to digital using a sampling rate of 5 KHz. The reference was between Fz/Cz and ground anterior to Fz (Formaggio et al., 2017).

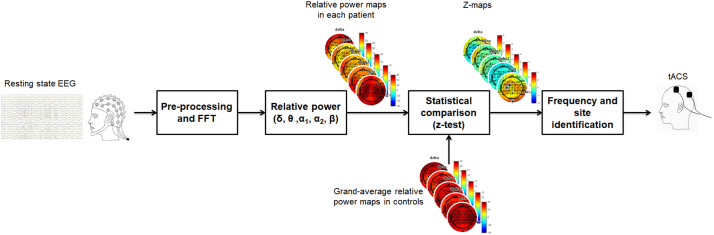

Data were processed in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA) using scripts based on EEGLAB toolbox (Delorme and Makeig, 2004) and dedicated custom-made code (Fig. 1). EEG recordings were down-sampled at 500 Hz and band-pass filtered 1–30 Hz. Visible artifacts (i.e., eyes movements, cardiac activity, scalp muscle contraction) were removed using an independent component analysis; data were processed using an average reference. A fast Fourier transform (FFT) was applied to non-overlapping epochs of 2 s and averaged across epochs. The recordings were Hamming-windowed to control for spectral leakage.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of workflow of EEG analysis at single subject level. After pre-processing, FFT was applied to non-overlapping 2-s epochs and then averaged across epochs. Power spectral density was estimated for all frequencies and the relative power (%) was computed for delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4.5–7.5 Hz), alpha1 (8–10 Hz), alpha2 (10.5–12.5 Hz) and beta (13–30 Hz) frequency ranges, producing different topographical maps. Relative powers of a single subject were statistically compared (z-test) to relative powers of a control group. From this comparison, we derived the frequency band and the site of stimulation, based on statistically significant different electrodes.

Power spectral density (μV2/Hz) was estimated for all frequencies and the relative power (%) was computed by dividing the power of each frequency band with the total power in the range 1–30 Hz according to the equation:

| (1) |

where x is the EEG channel, P is the power spectral density, b1 and b2 are the frequencies (Hz) in the range of interest: b1 = 1, b2 = 4 for delta; b1 = 4.5, b2 = 7.5 for theta; b1 = 8, b2 = 10 for alpha1; b1 = 10.5, b2 = 12.5 for alpha2¸ b1 = 13, b2 = 30 for beta.

Control data from twenty-one healthy volunteers (9 M; mean age 45.14 years, standard deviation [SD] 14 years) were obtained (Formaggio et al., 2017) using the same EEG montage.

Comparison of controls versus each participant was performed using a z-test (p < .05) (Duffy et al., 1981). A statistical map defines the electrodes, in which relative power value differs from those of the control group. From this comparison, we derived frequency (most represented frequency band) and site of stimulation (scalp area in which the prevalent EEG frequency focalized).

2.4. Study design, outcomes, stimulation parameters, and tACS treatment

The design was a cross over, double-blinded, randomized trial. Block randomization was generated by a computer (allocation ratio 1:4). The template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist was used (Supplementary material 2). Recruitment started in May 2016; follow up was completed in September 2017.

Primary outcome was a reduction of 30% of UPDRS III off-medication score. This proportion was derived from the 10.8 reduction in score considered to be a large clinical difference in PD trials, considering a mean UPDRS III score of around 30 for the sample population. Proportion of people with PD displaying an excess of beta band activity was the primary outcome of the assessment phase. Secondary outcomes were modifications of frequencies of oscillatory brain activity, measured as spectral power modifications, and improvement of behavioral tests after tACS.

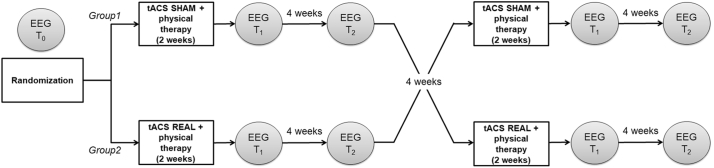

EEG acquisition and clinical assessments were performed before (T0) and immediately after stimulation (T1), and at 4-weeks follow-up (T2) (Fig. 2). The experiment consisted of two-weeks (5 days a week) sessions of tACS (real condition) or transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS) (active sham condition). Stimulation sessions lasted 30 min. TACS and RNS arms were separated by an 8-week period. Each stimulation session was immediately followed by a one-hour physiotherapy session (see Table 2 for protocol).

Fig. 2.

Experimental design.

Table 2.

Physiotherapy exercises for Parkinson's disease.

| Activities | Basic exercises |

|---|---|

| Relaxation exercises (5 min) | Breathing exercises to promote expansion of the chest (diaphragmatic and costal breathing) |

| Intersegmental coordination exercises | |

| Active joint mobilization (10 min) | Exercises for upper and lower limbs in the supine position, on the side, on all fours, sitting, standing |

| Exercises to release shoulder and pelvic girdle | |

| Pelvic anteversion and retroversion movements | |

| Exercises for cervical spine in sitting position (flexion-extension, lateral bending, rotation) | |

| Exercises for the trunk sitting and standing (flexion and rotation) | |

| Stretching exercises (10 min) | Exercises to stretch the ischio-cruralis muscles |

| Exercises to stretch the muscles of the posterior kinematic chain | |

| Exercises to stretch adductor muscle of the hip | |

| Exercises to stretch the hip extrarotator muscle | |

| Exercises to stretch lumbar muscles (in the supine position, each knee, in turn, is brought to the chest) | |

| The “bridge” exercise to stretch the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, glutei, quadriceps and hamstring | |

| Strengthening exercises in a functional context (10 min) | Exercises to strengthen the dorsal muscles (arms extended and hands outstretched as though to take something) |

| Lateral bending (arms lying along the body and hands reaching down as though to pick up something) | |

| Stretching using the wall bars | |

| Balance training (10 min) | Path with obstacles |

| Balance exercises performed in order of difficulty: | |

| - heel-to-toe walking | |

| - lateral walking crossing the legs | |

| - walking along a path on surfaces of different texture (foam mats, mats containing sand etc...) | |

| Ball exercises | |

| Overground gait training (10 min) | Overground gait training (forwards, backwards and lateral) |

| Walking on the spot | |

| Machine exercises (10 min) | Treadmill |

| Cycle ergometer | |

| Cyclette | |

| Leg extension | |

| Leg press | |

| Proprioceptive footboard | |

| Elliptical trainer |

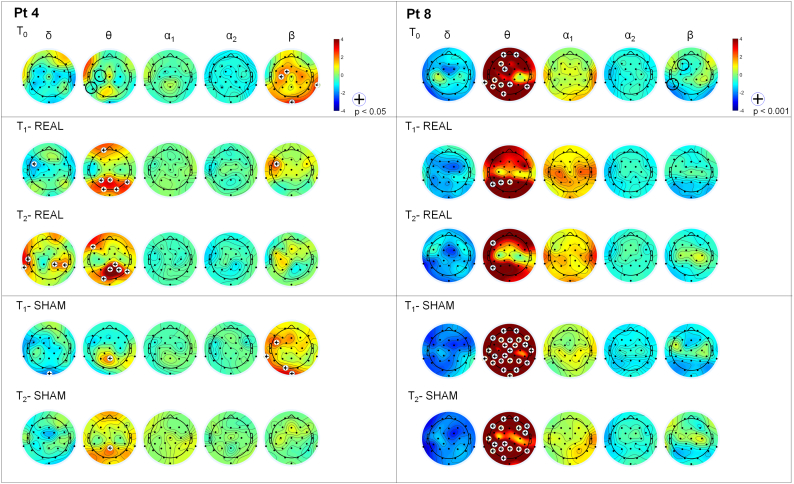

Stimulation was applied by a battery driven external stimulator (BrainStim, E.M.S., Bologna, Italy) via two sponge electrodes (5 × 7 cm). Stimulation frequency was set according to the EEG band displaying higher relative power (with beta excess on EEG map, tACS was set at 4 Hz; with theta excess, tACS was set at 30 Hz). Electrodes were positioned respectively over the scalp area in which the power spectral difference was detected and over the ipsilateral mastoid (see Fig. 3 for explicative cases). Intensity was 1 to 2 mA (sinusoidal current minimum/maximum). RNS was an alternate current with random amplitude and frequency (1–2 mA; 0–100 Hz) with electrodes applied over the same sites as for real stimulation.

Fig. 3.

Example of statistical comparison. Statistical maps derived from two subjects with PD vs. control group: one subject stimulated in theta range (Pt 4) and one in beta range (Pt 8). (Left) Participant 4 shows higher beta activity, compared to controls, over FC1 and C3. He was stimulated in theta range over C3 (black circle at T0). Beta activity reduction was observed after real stimulation but not after sham stimulation. (Right) Participant 8 shows higher theta activity, compared to controls, mainly over left frontal areas. He was stimulated in beta range over F3 (black circle at T0). No significant modifications were observed after both real and sham stimulation.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Region of interests (ROIs) were identified based on electrodes location: right (R) frontal ROI: Fp2, F8, F4; right motor ROI: FC2, FC6, C4, Cp2; right parietal ROI: CP6, P8, P4 and same for left (L) hemisphere.

For each frequency band, a linear model with random effects was employed to investigate the effects of treatment, time and ROI on the frequency. After multivariate analysis, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for paired data were performed to test the difference in relative power average for each ROI at T1 or T2, with respect to T0in each group (tACS and RNS).

Statistical analysis was applied to subgroups (created on the basis of their prevalent EEG rhythm: theta-tACS group stimulated in theta and beta-tACS group stimulated in beta, as described above). The dimension of the subgroup with prevalent slow rhythm (beta-tACS) allowed only the application of the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

The same statistical analysis was performed also for cognitive and motor variables for accounting for treatment and time simultaneously.

3. Results

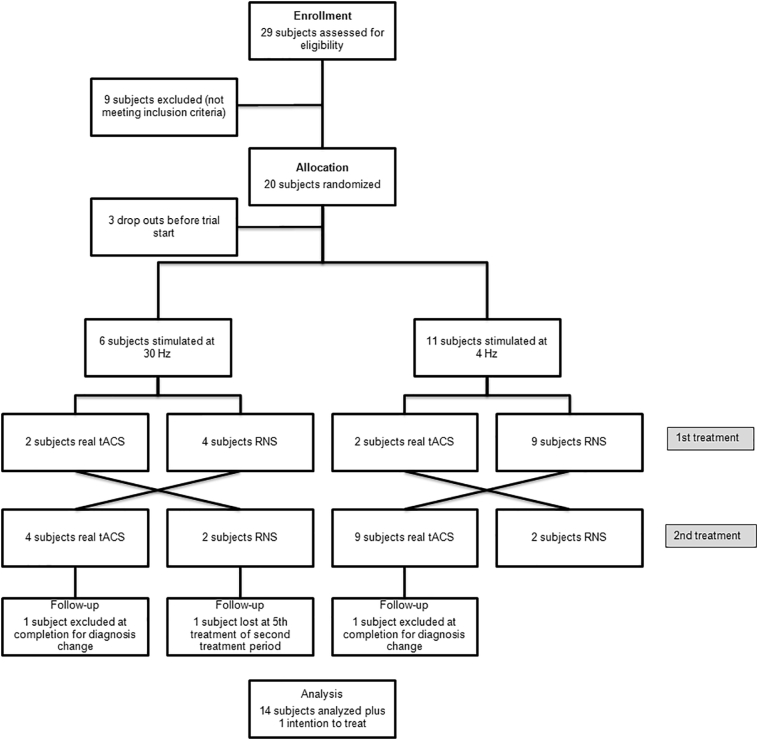

Twenty subjects were enrolled out of 29 potential candidates. See Fig. 4 for flow diagram. Fifteen subjects completed the study (9 M; mean age 69 ± 6.3 years; mean disease duration 6.3 ± 4.8 years; mean L-dopa dose 528.5 ± 290 mg). For demographics, see Table 3. PD participants were slightly older than controls (p < .01) but did not differ for other demographic variables (sex, years of education).

Fig. 4.

Study flow diagram.

Table 3.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of included participants.

| Subject | Age (years) | Sex | Duration of disease (years) | L-Dopa dose (mg) | Education (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 72 | Male | 2 | 800 | 16 |

| 2 | 64 | Female | 2 | 450 | 5 |

| 3 | 73 | Male | 1 | 200 | 13 |

| 4 | 79 | Male | 10 | 300 | 5 |

| 5 | 80 | Female | 3 | 300 | 13 |

| 6 | 69 | Male | 9 | 750 | 8 |

| 7 | 61 | Female | 11 | 600 | 11 |

| 8 | 75 | Male | 18 | 600 | 13 |

| 9 | 71 | Male | 6 | 400 | 17 |

| 10 | 63 | Male | 7 | 450 | 10 |

| 11 | 68 | Male | 2 | 300 | 17 |

| 12 | 60 | Male | 2 | 200 | 17 |

| 13 | 65 | Female | 8 | 400 | 5 |

| 14 | 66 | Female | 6 | 600 | 17 |

| 15 | 83 | Female | 4 | 400 | 5 |

Ten participants showed a prevalence of beta rhythm and were stimulated in theta frequency (theta-tACS group). Five had a prevalent slow rhythm and were stimulated in beta (beta-tACS group) (statistical significance at p < .001) (Table 4). None among participants showed a concomitant beta and theta excess on statistical maps.

Table 4.

Stimulation parameters.

| Subject | Prevailing band | Stimulation site | Stimulation frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beta | FC1 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 2 | Beta | FC5 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 3 | Beta | C3 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 4 | Beta | C3 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 5 | Alpha2 | CP5 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 6 | Theta | CP5 - Left mastoid | 30 Hz |

| 7 | Alpha1 | Pz - Right mastoid | 30 Hz |

| 8 | Theta | F3 - Left mastoid | 30 Hz |

| 9 | Beta | FC5 - Left mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 10 | Beta | C4 - Right mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 11 | Beta | C4 - Right mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 12 | Beta | C4 - Right mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 13 | Beta | C4 - Right mastoid | 4 Hz |

| 14 | Theta | C4 - Right mastoid | 30 Hz |

| 15 | Theta | CP5 - Left mastoid | 30 Hz |

Multivariate analysis in the group stimulated in theta showed main effect for factor “ROI” (p < .0001) in delta; “treatment” (p = .0001), “time” (p = .0006) and “ROI” (p = .002) in theta; “treatment” and “ROI” (p < .0001) in alpha1; “time” (p = .0002) and “ROI” (p < .0001) in alpha2; “treatment” (p < .0001), “ROI” (p < .0001) and “time” (p = .012) in beta.

No significant differences were found in delta and alpha1 bands. A theta power increase at T1 after theta-tACS was detected over L-frontal area (p = .0027) and L-SM (p = .037), compared to RNS. A power increase was observed in alpha2 after theta tACS at T1 vs. T0 over R-SM (p = .004) and over L-parietal area (p = .010); an increase at T2 vs. T0 was detected over the same areas (R-SM: p = .002, left parietal area: p = .027). Main results include a reduction of beta rhythm in theta-tACS vs. RNS group at T1 over R-SM (p = .014) and L-parietal area (p = .010) and at T2 over R-SM (p = .004) and L-frontal area (p = .039) (Fig. 3). In theta-tACS group beta rhythm reduction over R-SM persisted at T2 (p = .049).

Functional tests showed an effect on motor performance for factor “time” (p = .0009). Mean UPDRS III score change for the whole group after tACS was −5.9 point from T0 toT1 (mean reduction of 17% of baseline) and –4.82 from T0 toT2 (mean reduction of 14% of baseline). In the subgroup with beta excess mean reduction was −8.25 points from T0 toT1 (mean reduction of 23.5% of baseline) and −5.6 from T0 toT2 (mean reduction of 15.3% of baseline). Bradykinesia items improved at T1 (p = .002) and T2 (p = .047) compared to T0 in the theta-tACS group.

Cognitive tests showed an effect in factor “time” for MoCA (p = .029) and TMT_B (p = .041). MoCA improved at T2 between theta-tACS and RNS (p = .046). In the theta-tACS group MOCA improved at T2 vs. T1 (p = .049).

Complete motor and neuropsychological results are reported in Table 5, Table 6 respectively.

Table 5.

Motor scores: UPDRS III and Gait Dynamic Index scores.

| Motor items | Real tACS |

RNS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | |

| UPDRS-III | ||||||

| UPDRS-III total score | 33,29 | 27,36 | 28,46 | 33,18 | 30,54 | 25,11 |

| Bradikynesia score | 3 | 2,42 | 2,58 | 2,97 | 2,86 | 2,24 |

| Tremor score | 0,47 | 0,36 | 0,42 | 0,58 | 0,21 | 0,5 |

| Axial symptoms score | 0,83 | 0,84 | 0,72 | 0,82 | 0,79 | 0,59 |

| Dynamic Gait Index | 20,79 | 21 | 20,71 | 20,21 | 21,21 | 21,5 |

Table 6.

Neuropsychological scores.

| Neuropsychological items | Real tACS |

RNS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | |

| Clinical scales | ||||||

| Beck depression inventory-II | 5 | 7 | 7,57 | 9,21 | 6 | 8 |

| Geriatric depression scale | 5,21 | 4,43 | 3,79 | 3,21 | 3,5 | 4,5 |

| State trait anxiety inventory Y1 | 37,57 | 40,86 | 40 | 37,36 | 41,29 | 36,57 |

| Screening for dementia | ||||||

| Montreal cognitive assessment | 24,79 | 22,71 | 26,5 | 23,71 | 24,79 | 23 |

| Attention and working memory | ||||||

| Trail making test | ||||||

| TMT-A | 48,71 | 52,86 | 49,79 | 54,64 | 52,5 | 48,93 |

| TMT-B | 116,07 | 78,83 | 96,43 | 173,5 | 119,79 | 108,29 |

| Delta trail | 67,36 | 37,29 | 50,5 | 118,86 | 67,29 | 59,36 |

| Digit symbol substitution test | 45,86 | 43,71 | 42 | 41,43 | 42,71 | 46,07 |

| Executive function | ||||||

| Phonemic fluency | 31,43 | 30,86 | 31,79 | 30,14 | 30,36 | 31,43 |

| Visuospatial abilities | ||||||

| Rey complex figure | ||||||

| Copy | 26,36 | 25,21 | 24,71 | 24,07 | 26,29 | 26 |

| Copy-time | 136,36 | 123,43 | 124,43 | 175 | 155,57 | 141,93 |

| Memory | 15,61 | 14,96 | 14,82 | 12,71 | 13,79 | 12,93 |

| Memory-time | 147,71 | 152,5 | 119,29 | 130,43 | 114 | 135,43 |

| Verbal learning and memory | ||||||

| Hopkins verbal learnig test-revised | 21,43 | 20,79 | 21,71 | 19,43 | 20,29 | 20,71 |

Beta-tACS did not yield significant results.

4. Discussion

TACS delivered with a personalized paradigm associated with ad hoc rehabilitative treatment in people with PD can correct excessive fast cerebral oscillations and improve bradikynesia and cognitive functions.

Our experiment sets out to provide a personalized approach for neurostimulation. The change of paradigm into which medicine is incurring needs to be translated into neurophysiology and neurostimulation. Current neurostimulation designs have up to now targeted cerebral areas, which were hypothesized to play a role in the pathology, but individual mapping has not been a prerequisite.

Excess of beta band in PD has been related to motor symptoms (Brittain and Brown, 2014); the degree of beta suppression correlates with the change in UPDRS-III scores (Oswal et al., 2016). Our population showed a prevalence of beta rhythm and a subgroup displayed a prevalence of theta power. This is in line with reports in PD of an EEG slowing, possibly related to cognitive impairment in PD (Caviness et al., 2016); although such a straightforward relation did not emerge in our sample due to the exclusion of overt cognitive impaired participants, this finding supports the notion that not every subject with PD will have an excess of beta.

Individual definition of the treatment protocol lies on the assumption of a different prevalent rhythm and lateralization of it. PD starts with a unilateral basal ganglia involvement, which reflects into a lateralization of EEG activity and has been associated with clinical disability (Mostile et al., 2015).

Individual targeting of frequency and site of stimulation appears thus mandatory to optimize treatment effects.

Previous studies reported discordant outcomes of tACS in PD. TACS applied to the forehead with a frequency of 77.5 Hz did not significantly influence off-medication UPDRS scores in subjects in the initial stages (Shill et al., 2011). Lack of efficacy could be due either to positioning of the stimulator (frontal instead of motor cortex) or to inadequate frequency (Pogosyan et al., 2009).

Rhythmic non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques have been shown to effectively modulate frequency bands (Herrmann et al., 2016). By strengthening the up- and down states of neuronal ensambles, which constitute the oscillatory network, tACS facilitates the spiking of neurons during down-phases, which in turn elicits further spiking by adjacent neurons (McDonnell and Abbott, 2009). The state-dependent oscillatory behavior of the brain is supported by perturbational studies, in which the on-going brain activity is disrupted by an external stimulus, i.e. transcranial magnetic stimulation. Overall brain activity subsides in the few milliseconds after the TMS pulse, only to show a rebound in the oscillatory activity which was prevalent immediately before the perturbation (e.g. during slow waves sleep, a rebound in delta band) (Manganotti et al., 2013; Del Felice et al., 2011). Taken together these observations consolidate the view that brain intrinsic dynamic networks are highly non-entropic systems, which tend spontaneously to return to the point of equilibrium – or into the physiological oscillatory range.

Our aim was to interfere with pathological oscillations and shift oscillatory brain activity into its physiological range. Although the neurophysiological and theoretical framework of rhythmic NIBS entrainment supports the view of an oscillatory substrate for modulation to take effect, we tested the hypothesis that brain rhythms could indeed be shifted into their natural oscillatory range.

Interestingly, only theta stimulation applied mainly over the SM area modified both neurophysiological and behavioral parameters. EEG frequencies showed a slowing associated with a reduction of bradykinesia score and an improvement of cognitive functions.

We do not have a clear explanation for this finding. PD is generally known as a beta oscillopathy; slow rhythms are associated with cognitive decline and considered a prognostic marker of it (Olde Dubbelink et al., 2013). One hypothesis is that beta excess could be more easily correct because it oscillates in an encircled circuit – thalamo-cortico-basal network. Slow rhythms, particularly in sub-cortical cognitive impairment, are a diffuse phenomenon. A focal stimulation, such as tACS, is thus likely to interrupt a defined circuit but is unlikely to impact on a pan-cortical phenomenon such as global slowing.

An active sham stimulation was used. A recent consensus statement (Thut et al., 2017) raised the issue of the effects of an electrical stimulation in modulating brain function: RNS, which does not deliver a definite sinusoidal stimulus, has been suggested as an effective control. Indeed, data on RNS are inconclusive regarding its influence on motor and cognitive performances (Ho et al., 2015; Tyler et al., 2018).

The effectiveness of our intervention compared to an active sham further strengthens our findings. No significant effects on brain rhythms and motor scores were recorded during sham, confirming that clinical and neurophysiological outcomes are causally related to tACS – and thus a modulation of on-going brain oscillations.

The coupling of physical therapy with neurostimulation has a rational in physical therapy being a mainstay of current PD treatment; it improves motor and cognitive functions in individuals with mild to moderate impairment (Petzinger et al., 2013) and has been included as adjuvant to pharmacological and neurosurgical approaches (Abbruzzese et al., 2016; Duchesne et al., 2015). Association of physical therapy to tACS has a dual aim: exercise activates cortical sensori-motor areas, priming the neuronal population. TACS may also be useful in amplifying cortical plasticity during neurorehabilitation (Block and Celnik, 2012).

Motor outcome improved immediately after the conclusion of real stimulation. The study protocol set a very conservative cut-off (30% reduction from baseline). This result was not obtained but we are confident in supporting the efficacy of intervention. The MCID for UPDRS III is set at 2.5 points for minimal, 5.2 for moderate, and 10.8 for large differences (Shulman et al., 2010). Our population showed an overall reduction of 5.9 points and a reduction of 8.25 points in the subgroup with beta spectral power excess EEG. These results account for a moderate effect, despite a reduction of 17–23.5% of baseline score instead of the 30% defined by the protocol.

We observed a specific reduction of the bradykinesia UPDRSIII sub-items with almost no effect on gait and posture. This finding supports the causal link of beta band excess and bradikynesia with a mechanism, which mimics deep brain stimulation effects on axial impairment – i.e. scarce efficacy.

We found an improvement of cognitive abilities (prefrontal-executive) at follow-up. This finding may be attributed to increased neuronal plasticity that may make treatment benefits on cognition more evident later in time (Reato et al., 2013). The time interval between end-of-treatment and follow-up represents a precious period for consolidation.

We used parallel versions of tests to overcome any learning effect in repeated test.

The main limitation is the small sample size. To overcome this issue large, multicentre studies are mandatory. In fact, we did not consider age difference between PD participants and controls as main limitation. In light of the known slight slowing of EEG rhythms in the elderly, with a shift of beta to alpha rhythm and a projection of alpha towards more anterior regions, we deemed this finding not relevant for data interpretation. Indeed, PD shows an increase of the relative beta power (i.e. the beta absolute power divided by the power calculated in the whole spectrum) compared to healthy volunteers: considering that we would expect a slight slowing of faster EEG rhythms in the elderly, our finding of a beta excess over sensorimotor areas is all but more significant.

A potential bias could have been concomitant drug therapy, affecting stimulation effects, although dosage of any group was maintained stable to avoid confounders. Intra-subject data comparison reduced this bias.

5. Conclusion

These data provide evidence of the efficacy of personalized tACS coupled with physical therapy on motor and cognitive symptoms in PD. Long term efficacy and different schedules need to be investigated to determine the real feasibility of tACS as an add-on home therapy.

Funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Laura Gallo and Michele Tonellato for their precious and invaluable help in data collection and Laura Masiero for preliminary statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101768.

Contributor Information

Alessandra Del Felice, Email: alessandra.delfelice@unipd.it.

Leonora Castiglia, Email: leonoracastiglia@gmail.com.

Emanuela Formaggio, Email: emanuela.formaggio@unipd.it.

Manuela Cattelan, Email: manuela.cattelan@stat.unipd.it.

Bruno Scarpa, Email: scarpa@stat.unipd.it.

Paolo Manganotti, Email: pmanganotti@units.it.

Elena Tenconi, Email: elena.tenconi@unipd.it.

Stefano Masiero, Email: stef.masiero@unipd.it.

Appendix A. Neuropsychological testing

The Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) is an interview about the preferred use of hands, feet, eyes and ears (32 items). Individuals with Edinburgh scores between −69 and + 69 were considered “mixed-handed” and those with scores higher than +69 were considered “fully right-handed”.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1983) is a 40-item self-report questionnaire assessing state and trait anxiety levels. Scores range from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety severity.

The Brief Intelligence Test (TIB) (Colombo et al., 2002) gives an estimate of the intellectual ability level previous to the onset of the disorder (i.e., premorbid intellectual ability); the test is the Italian version of the National Adult Reading Test. The task consists in reading 34 irregular Italian words which violate typical stress rules. Successful word reading is thought to be linked to prior achievements and not to current cognitive ability.

The Montréal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a 30-point brief cognitive screening scale with short time of administration. The Movement Disorders Society (MDS) rated MoCA scale as “recommended” for screening assessment in PD and proposed the following cut-offs: 20–21/30 for PD-D (PD and dementia) and 23–29/30 for PD-MCI (mild cognitive impairment) (Nasreddine et al., 2005). It measures a broad spectrum of cognitive abilities that are relevant to PD: in particular, it is developed to explore frontal cognitive domains (i.e., attention, executive functions, and conceptual thinking), all domains frequently involved in early stage PD. The MoCA appears to be more specific to the type of cognitive deficit showed by PD patients.

The Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (ROCF – Rey, 1941) is a measure of visuo-spatial constructional abilities and visuo-graphic memory, but also cognitive planning, organisational strategies and executive functions. The task is composed of two parts, direct copying (assessing perception and visuo-spatial construction) and delayed reproduction (assessing implicit visuo-spatial memory). We used the three minutes (short) delay to assess visual memory. Given that repeated administrations of the ROCF resulted in significant improvements of performance, we used alternative forms: the Modified Taylor Complex Figure, and two out of the four complex figures devised for repeated assessments by the Medical College of Georgia Neurology group (Fig. 2, Fig. 3) (Lezak et al., 2004). This task was used in other disorders as a measure of central coherence (the ability to put together different details in order to gain the “big picture”) by means of both the Order of Construction Index (the order in which the different global elements were drawn) and the Style Index (indicative of the degree of continuity in the drawing process). The Central Coherence Index (CCI) ranges from 0 (weak coherence) to 2 (strong coherence).

The Digit Symbol-Coding (from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th edition; Wechsler, 2013), is a measure of grapho-motor working memory and speed of processing. It consists of digit-symbol pairs followed by a list of digits. Participants must write the corresponding symbol under each digit (ranged from one to nine) as fast as possible in a limited time interval (120″). Digit Symbol appears to be relatively unaffected by intelligence, memory, or learning. Motor persistence, sustained attention, response speed, visuomotor coordination, all have some role in digit symbol performance, which is also affected by education, gender and age. No practice effects appeared after repeated administering (Lezak et al., 2004).

The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (Brandt, 1991) is a test that assesses verbal learning and memory. The test consists of three trials of free-recall of a 12-item composed of four words belonging to three different semantic categories. The authors provide six parallel forms leading to equivalent results in the normal population. We used three lists (N 1, 5, and 6) and considered only the free-recall as outcome measure.

The Trail Making Test A and B (Reitan, 1958) measures attentional speed, sequencing, visual search and mental flexibility. Part A (TMT-A) assesses motor speed, part B (TMT-B) assesses complex divided attention and set-shifting, B-A difference (i.e., B/A ratio) gives a measure of cognitive shifting cost and allows us to control for motor impairment. Practice effect is under discussion, especially in the case of short time interval, and we used three parallel forms (LoSasso et al., 1998).

The Phonemic Verbal Fluency task (Newcombe, 1969) requires patients to freely generate as many words as possible that begin with a specific letter (phonemes) in 60 s. The task requires patients to retrieve words of their language and to access their verbal lexicon, focus on the task, select only words following specific rules and avoid repetitions and words that start with phonemes close to the target one. It is therefore considered dependent on executive control, beyond the involvement of verbal abilities. The outcome consists in the total correct words produced through three letters. In the literature different letter combinations are available to longitudinal studies.

The Geriatric Depression Scale-15 item (Sheikh and Yesavage, 1986) is a self-administered instrument widely used to assess mood levels in the elderly population. Suggested cut-off scores range from 7 ± 3 (mild depression) to 12 ± 2 (severe depression).

The Beck's Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996) was used to assess depression. It consists of a 21-item questionnaire yielding a composite score of self-reported symptom severity. Standard cut-off scores are: 0–9 = minimal depression, 10–18 = mild depression, 19–29 = moderate depression, and 30–63 = severe depression.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

Supplementary material 1 Consort checklist.

Supplementary material 2 Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR).

References

- Abbruzzese G., Marchese R., Avanzino L., Pelosin E. Rehabilitation for Parkinson's disease: current outlook and future challenges. Park. Relat. Disord. 2016;22(Suppl. 1):S60–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Brown G.K. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. [Google Scholar]

- Block H.J., Celnik P. Can cerebellar transcranial direct current stimulation become a valuable neurorehabilitation intervention? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012;12(11):1275–1277. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J. The Hopkins verbal learning test: development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1991;5(2):125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain J., Brown P. Oscillations and the basal ganglia: motor control and beyond. Neuroimage. 2014;85(2):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P., Oliviero A., Mazzone P., Insola A., Tonali P., Di Lazzaro V. Dopamine dependency of oscillations between subthalamic nucleus and pallidum in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2001;21(3):1033–1038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-03-01033.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G., Draguhn A. Neuronal oscillations in cortical networks, American Association for the advancement of science stable. Adv. Sci. 2011;304(5679):1926–1929. doi: 10.1126/science.1099745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caviness J.N., Utianski R.L., Hentz J.G., Beach T.G., Dugger B.N., Shill H.A., Driver-Dunckley E.D., Sabbagh M.N., Mehta S., Adler C.H. Differential spectral quantitative electroencephalography patterns between control and Parkinson's disease cohorts. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016;23(2):387–392. doi: 10.1111/ene.12878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C.E., Patel S., Ives N., Rick C.E., Woolley R., Wheatley K., Walker M.F., Zhu S., Kandiyali R., Yao G., Sackley C.M. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy and occupational therapy versus no therapy in mild to moderate Parkinson's disease: a large pragmatic randomised controlled trial (PD REHAB) Health Technol. Assess. 2016;20(63):1–96. doi: 10.3310/hta20630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo L., Sartori G., Brivio C. Stima del quoziente intellettivo tramite l'applicazione del TIB (Test breve di Intelligenza) G. Ital. Psicol. 2002;3:613–637. [Google Scholar]

- Del Felice A., Fiaschi A., Bongiovanni G.L., Savazzi S., Manganotti P. The sleep-deprived brain in normals and patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: a perturbational approach to measuring cortical reactivity. Epilepsy Res. 2011;96(1–2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Felice A., Magalini A., Masiero S. Brain stimulation slow-oscillatory transcranial direct current stimulation modulates memory in temporal lobe epilepsy by altering sleep spindle generators : a possible rehabilitation tool. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorme A., Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2004;134(1):9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne C., Lungu O., Nadeau A., Robillard M.E., Boré A., Bobeuf F., Lafontaine A.L., Gheysen F., Bherer L., Doyon J. Enhancing both motor and cognitive functioning in Parkinson's disease: aerobic exercise as a rehabilitative intervention. Brain Cogn. 2015;99:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy F.H., Bartels P.H., Burchfiel J.L. Significance probability mapping: an aid in the topographic analysis of brain electrical activity. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1981;51(5):455–462. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(81)90221-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner B., Kugler J., Pohl M., Mehrholz J. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for idiopathic Parkinson's disease (review) Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010916.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A.K., Fries P. Beta-band oscillations-signalling the status quo? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel A.K., Fries P., Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top–down processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:704–716. doi: 10.1038/35094565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eusebio A., Brown P. Synchronisation in the beta frequency-band – the bad boy of parkinsonism or an innocent bystander? Exp. Neurol. 2009;217(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formaggio E., Masiero S., Bosco A., Izzi F., Piccione F., Del Felice A. Quantitative EEG evaluation during robot-assisted foot movement. IEEE Trans. Neural. Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2017;25(9):1633–1640. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2016.2627058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich R.F., Schneider T.R., Rach S., Trautmann-Lengsfeld S.A., Engel A.K., Herrmann C.S. Entrainment of brain oscillations by transcranial alternating current stimulation. Curr. Biol. 2014;24(3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann C.S., Murray M.M., Ionta S., Hutt A. Shaping intrinsic neural oscillations with periodic stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(19):5328–5337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0236-16.2016. 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K.A., Taylor J.L., Loo C.K. Comparison of the effects of transcranial random noise stimulation and transcranial direct current stimulation on motor cortical excitability. J. ECT. 2015;31(1):67–72. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison W.D., Lozano A.M., Tasker R.R., Lang A.E., Dostrovsky J.O. Identification and characterization of neurons with tremor-frequency activity in human globus pallidus. Exp. Brain Res. 1997;113(3):557–563. doi: 10.1007/pl00005606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joundi R.A., Jenkinson N., Brittain J.S., Aziz T.Z., Brown P. Driving oscillatory activity in the human cortex enhances motor performance. Curr. Biol. 2012;22(5):403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn A.A., Kempf F., Brucke C., Gaynor Doyle L., Martinez-Torres I., Pogosyan A., Trottenberg T., Kupsch A., Schneider G.H., Hariz M.I., Vandenberghe W., Nuttin B., Brown P. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus suppresses oscillatory activity in patients with Parkinson's disease in parallel with improvement in motor performance. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(24):6165–6173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0282-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn A.A., Trottenberg T., Kivi A., Kupsch A., Schneider G.H., Brown P. The relationship between local field potential and neuronal discharge in the subthalamic nucleus of patients with Parkinson's disease. Exp. Neurol. 2005;194(1):212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalo E., Thobois S., Sharott A., Polo G., Mertens P., Pogosyan A., Brown P. Patterns of bidirectional communication between cortex and basal ganglia during movement in patients with Parkinson disease. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(12):3008–3016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5295-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak M.D., Howieson D.B., Loring D.W., Hannay H.J., Fischer J.S. 4. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, US: 2004. Neuropsychological Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Llinas R.R., Ribary U., Jeanmonod D., Kronberg E., Mitra P.P. Thalamocortical dysrhythmia: a neurological and neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by magnetoencephalography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96(26):15222–15227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoSasso G.L., Rapport L.J., Axelrod B.N., Reeder K.P. Intermanual and alternate-form equivalence on the trail making tests. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998;20(1):107–110. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.1.107.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganotti P., Formaggio E., Del Felice A., Storti S.F., Zamboni A., Bertoldo A., Fiaschi A., Toffolo G.M. Time-frequency analysis of short-lasting modulation of EEG induced by TMS during wake, sleep deprivation and sleep. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013;7:767. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden J.F., Limousin-Dowsey P., Ashby P., Pollak P., Brown P. Subthalamic nucleus, sensorimotor cortex and muscle interrelationships in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 2):378–388. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell M.D., Abbott D. What is stochastic resonance? Definitions, misconceptions, debates, and its relevance to biology. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009;5(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostile G., Nicoletti A., Dibilio V., Luca A., Pappalardo I., Giuliano L., Cicero C.E., Sciacca G., Raciti L., Contrafatto D., Bruno E., Sofia V., Zappia M. Electroencephalographic lateralization, clinical correlates and pharmacological response in untreated Parkinson's disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015;21(8):948–953. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine Z.S., Phillips N.A., Bédirian V., Charbonneau S., Whitehead V., Collin I., Cummings J.L., Chertkow H. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann W.J., Staub-Bartelt F., Horn A., Schanda J., Schneider G.H., Brown P., Kühn A.A. Long term correlation of subthalamic beta band activity with motor impairment in patients with Parkinson's disease. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017;128(11):2286–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcombe F. Oxford University Press; 1969. Missile Wounds of the Brain: A Study of Psychological Deficits. [Google Scholar]

- Olde Dubbelink K.T.E., Stoffers D., Deijen J.B., Twisk J.W.R., Stam C.J., Berendse H.W. Cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease is associated with slowing of resting-state brain activity: a longitudinal study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34(2):408–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield R.C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswal A., Beudel M., Zrinzo L., Limousin P., Hariz M., Foltynie T., Litvak V., Brown P. Deep brain stimulation modulates synchrony within spatially and spectrally distinct resting state networks in Parkinson' s disease. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 5):1482–1496. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandis N., Chung B., Scherer R.W., Elbourne D., Altman D.G. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension checklist for reporting within person randomised trials. BMJ. 2017;357:j2835. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzinger G.M., Fisher B.E., McEwen S., Beeler J.A., Walsh J.P., Jakowec M.W. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(7):716–726. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70123-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogosyan A., Gaynor L.D., Eusebio A., Brown P. Boosting cortical activity at Beta-band frequencies slows movement in humans. Curr. Biol. 2009;19(19) doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.074. (1637–4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priori A., Lefaucheur J. Personal view chronic epidural motor cortical stimulation for movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70056-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reato D., Rahman A., Bikson M., Parra L.C. Effects of weak transcranial alternating current stimulation on brain activity – a review of known mechanisms from animal studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013;23(7):687. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan R.M. Validity of the trail making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept. Mot. Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh J.I., Yesavage J.A. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. J. Aging Mental Health. 1986;5(1–2):165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Shill H.A., Obradov S., Katsnelson Y., Pizinger R. A randomized, double-blind trial of transcranial electrostimulation in early Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 2011;26(8):1477–1480. doi: 10.1002/mds.23591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamoto S.A., Ryapolova-Webb E.S., Ostrem J.L., Galifianakis N.B., Miller K.J., Starr P.A. Subthalamic nucleus neurons are synchronized to primary motor cortex local field potentials in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(17):7220–7233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4676-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman L.M., Gruber-Baldini A.L., Anderson K.E., Fishman P.S., Reich S.G., Weiner W.J. The clinically important difference on the unified Parkinson's disease rating scale. Arch. Neurol. 2010;67(1):64–70. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D., Gorsuch R.L., Lushene R.E., Vagg P.R., Jacobs G.A. Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1 – Y2) [Google Scholar]

- Stein E., Bar-Gad I. Beta oscillations in the cortico-basal ganglia loop during parkinsonism. Exp. Neurol. 2013;245:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thut G., Bergmann T.O., Fröhlich F., Soekadar S.R., Brittain J.S., Valero-Cabré A., Sack A.T., Miniussi C., Antal A., Siebner H.R., Ziemann U., Herrmann C.S. Guiding transcranial brain stimulation by EEG/MEG to interact with ongoing brain activity and associated functions: a position paper. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017;128(5):843–857. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler S.C., Contò F., Battelli L. Rapid improvement on a temporal attention task within a single session of high-frequency transcranial random noise stimulation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018;30(5):656–666. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_01235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 Consort checklist.

Supplementary material 2 Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR).