Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is a small free radical with critical signaling roles in physiology and pathophysiology. The generation of sufficient NO levels to regulate the resistance of the blood vessels and hence the maintenance of adequate blood flow is critical to the healthy performance of the vasculature. A novel paradigm indicates that classical NO synthesis by dedicated NO synthases is supplemented by nitrite reduction pathways under hypoxia. At the same time, reactive oxygen species (ROS), which include superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, are produced in the vascular system for signaling purposes, as effectors of the immune response, or as byproducts of cellular metabolism. NO and ROS can be generated by distinct enzymes or by the same enzyme through alternate reduction and oxidation processes. The latter oxidoreductase systems include NO synthases, molybdopterin enzymes, and hemoglobins, which can form superoxide by reduction of molecular oxygen or NO by reduction of inorganic nitrite. Enzymatic uncoupling, changes in oxygen tension, and the concentration of coenzymes and reductants can modulate the NO/ROS production from these oxidoreductases and determine the redox balance in health and disease. The dysregulation of the mechanisms involved in the generation of NO and ROS is an important cause of cardiovascular disease and target for therapy. In this review we will present the biology of NO and ROS in the cardiovascular system, with special emphasis on their routes of formation and regulation, as well as the therapeutic challenges and opportunities for the management of NO and ROS in cardiovascular disease.

I. INTRODUCTION

Nitric oxide (NO) is a small free radical molecule with critical signaling roles. The discovery of the function of NO in the vascular endothelium as endothelium-derived relaxing factor led to the awarding of the 1998 Nobel Prize to Drs. Furchgott, Ignarro and Murad (36, 324, 449, 491, 716). The functions of NO in mammalian systems extend beyond vascular signaling and are relevant in all organ systems, including but not limited to neuronal signaling, and host defense (448, 659, 738).

A number of oxygen-related species of high chemical reactivity are referred to as reactive oxygen species (ROS). These include oxygen radicals and peroxides, such as superoxide (O2·−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitrogen radical species, such as NO and nitrogen dioxide (NO2·), and other species, such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and hypochlorite (ClO−). The species containing nitrogen are often treated separately as reactive nitrogen species (RNS). It is worth indicating that despite being long considered toxic species, most of these molecules have been shown to exert important signaling functions (249, 778, 937, 960). Therefore, the role of many of these molecules in health and disease is related to their production rates, steady-state concentrations, and the ability of the cellular antioxidant systems to modulate their activity.

In general, dysregulated production of ROS/RNS, as is the case for NO, leads to oxidative stress and deleterious consequences for living systems. However, as pointed out above, these molecules often have important signaling roles at low concentrations. For instance, the differences in response to NO at varying concentrations have attracted considerable attention. It has been shown that low levels (pM/nM) are physiological and related to the activation of high affinity primary binding targets such as soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) and cytochrome c oxidase (433, 863). An emerging paradigm proposes that intermediate levels (50–300 nM) can activate a range of positive and negative responses from wound healing to oncogenic pathways (938). Higher concentrations of NO (>1 μM) can lead not only to oxidative stress but also nitrative and nitrosative stress via the generation of peroxynitrite and nitrosating species (411, 412, 938, 939), and in combination with oxygen, can trigger posttranslational modification of proteins, lipids, and DNA (277, 433, 938).

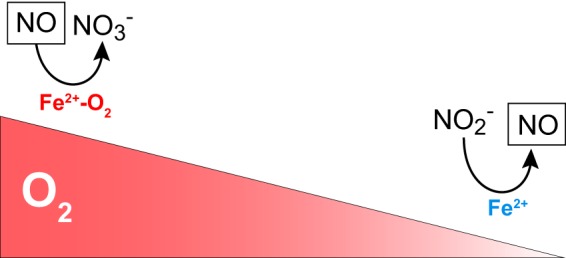

The production of adequate levels of NO in the vascular endothelium is critical for the regulation of blood flow and vasodilation, as will be discussed at length in this review (299, 565, 573, 600, 786). In this context, it has become increasingly appreciated that oxygen levels can impact the oxidation/reduction properties of different proteins and regulate NO levels (FIGURE 1) (367, 578, 595, 931). For example, nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) produce NO using l-arginine and molecular oxygen (O2) as substrates. Thus, under hypoxic or anoxic conditions, the generation of NO via NOS is compromised. However, a number of proteins that are involved in oxidative processes at basal oxygen levels can become de facto reductases as oxygen is depleted. The biological role of this transition is particularly prominent in the case of heme- and molybdopterin-containing proteins such as hemoglobin (Hb), myoglobin (Mb), and xanthine oxidase (XO) (185, 575, 578, 862, 880, 945, 990). Clinical intervention through these pathways continues attracting intense research.

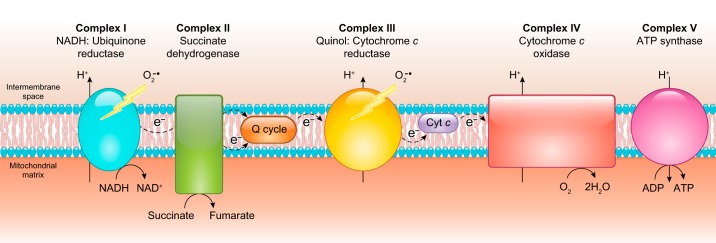

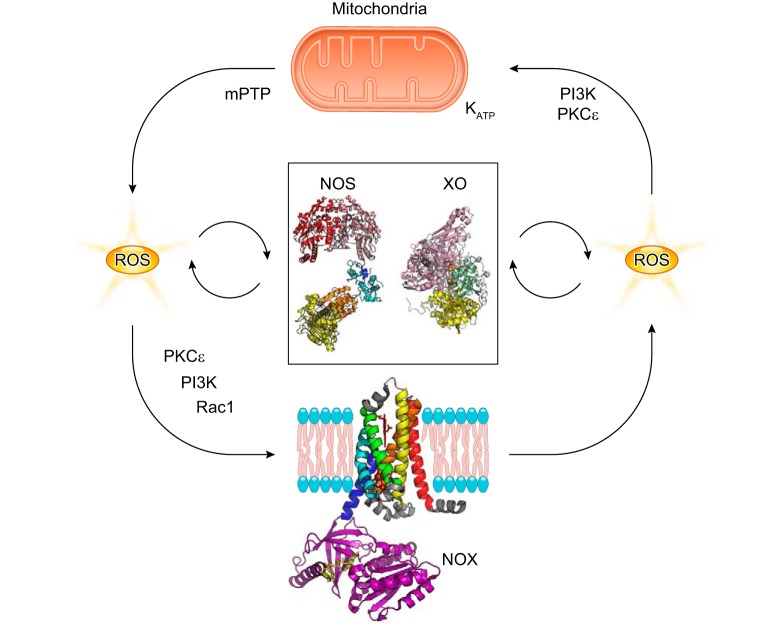

FIGURE 1.

Oxygen and oxidoreductase enzymes regulate nitric oxide (NO) homeostasis. The gradient in the concentration of oxygen shifts the function of globins from oxidizing, NO-scavenging proteins to nitrite-reducing, NO-generating proteins.

The concept of oxygen-regulated oxidation and reduction processes in the metabolism of NO is not only relevant to NO generation but also to the scavenging of NO in the vasculature (FIGURE 1). In this regard, the role of globins like α-Hb and cytoglobin (Cygb) as catalytic NO dioxygenases that scavenge NO is a topic of current research (25, 593, 594, 898).

The translation of our knowledge about the biology of NO and ROS has encountered significant challenges. For instance, initial attempts to enhance NO levels using NO donors or supplementing with NOS substrates to reverse endothelial dysfunction have had limited success. The use of general antioxidants for the treatment of oxidative stress has also failed in most cases. Recent advances in the field have provided many clues on why these approaches have been unsuccessful. We will discuss these and other relevant physiological and pathophysiological issues and indicate how advances in basic biochemistry of the generation of NO/ROS have evolved our understanding and set new directions in the field.

In this review, we will present the biology of NO and ROS in the cardiovascular system with special emphasis on their routes of formation, chemistry, mode of action, and dysregulation in vascular disease. The formation pathways of NO and the mechanisms of NO signaling will be discussed in sect. II. The proteins and biological systems generating hydrogen peroxide and superoxide are treated in sect. III. Other ROS of particular relevance in the vascular system are discussed in sect. IV. Section V will study the cross-talk between NO- and ROS-generating systems. Finally, in sect. VI, we will discuss the current challenges and opportunities for the treatment of cardiovascular disease through the regulation of NO and ROS levels in pathological conditions.

II. NITRIC OXIDE GENERATION AND VASCULAR FUNCTION

The generation of sufficient NO levels to regulate the resistance of the blood vessels and hence the maintenance of an adequate blood flow is critical to the healthy performance of the vasculature (277, 299, 573, 600, 786). A number of mechanisms are involved in both the generation of NO and the response to NO signaling in the vasculature. In this section, we will overview the mammalian proteins involved in the generation and sensing of NO in the cardiovascular system. The production of NO in basal conditions is largely regulated by the activity of endothelial NOS (eNOS) in the vascular endothelium (324, 449, 716). Nevertheless, the contribution of other agents cannot be ignored. For instance, nitrite reduction by heme proteins can mediate hypoxic vasodilation and other physiological responses (367, 591, 968); neuronal NOS (nNOS) and inducible NOS (iNOS) can provide compensatory NO generation or exacerbated RNS synthesis (386, 444, 547, 704, 727). In this study, we will review NO synthases and other NO-generating biological systems.

A. Oxygen-Dependent Nitric Oxide Synthesis

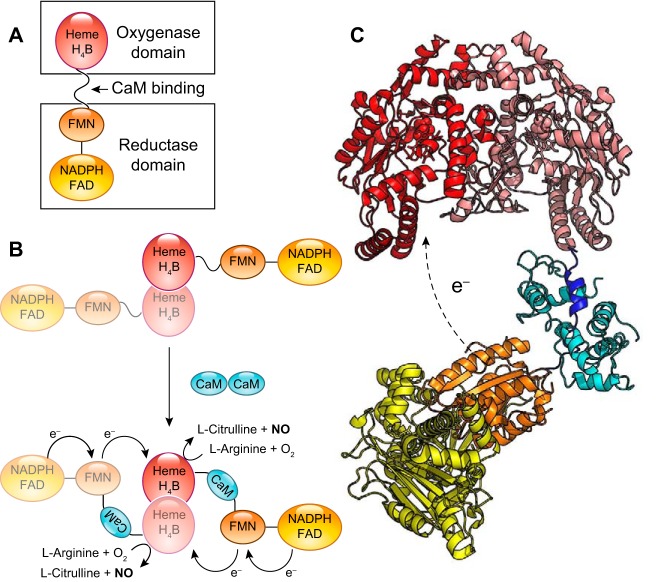

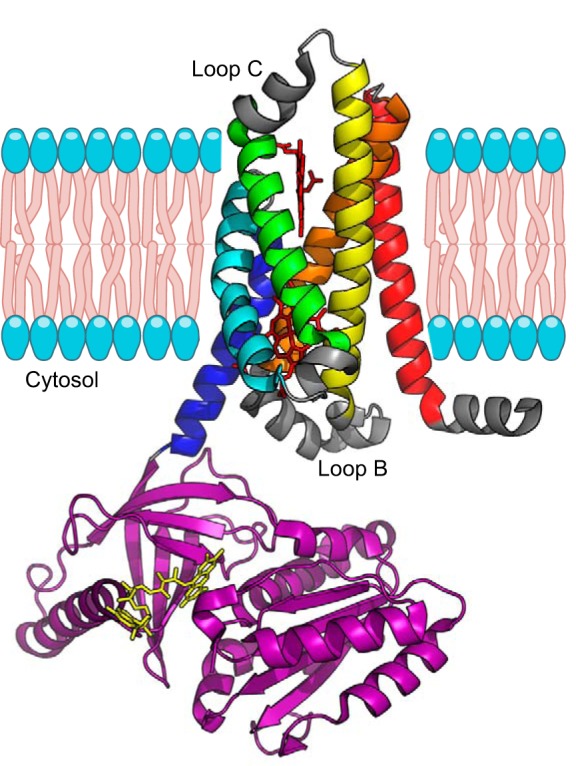

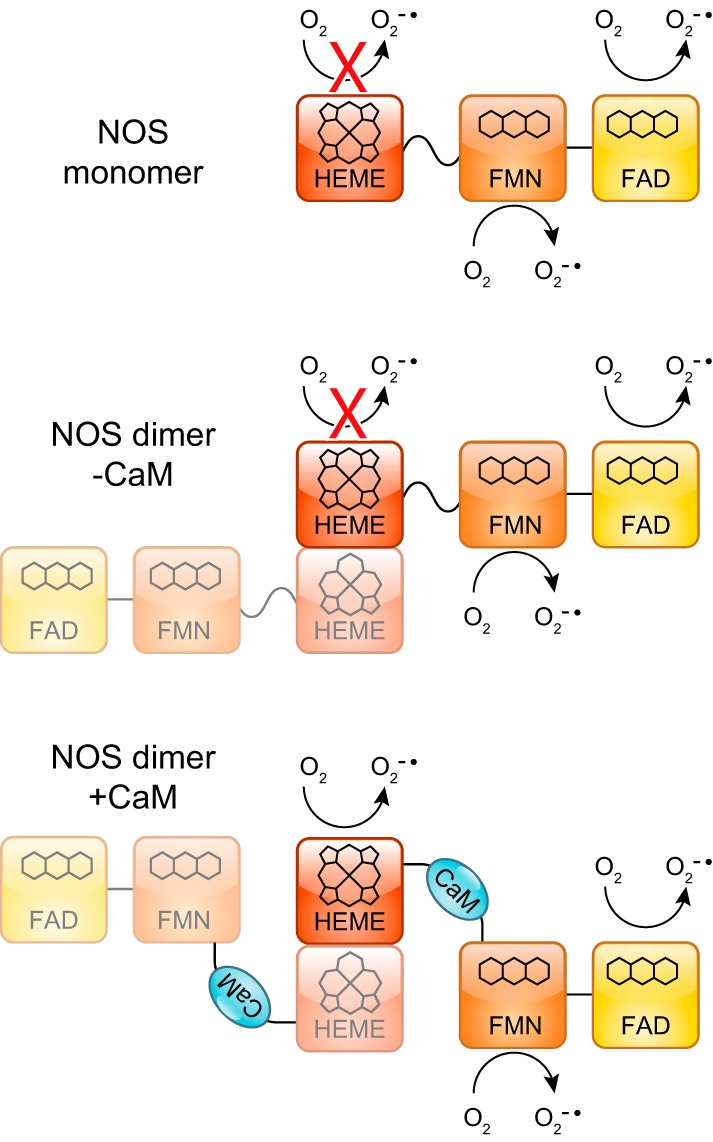

The canonical pathways of NO formation rely on the specialized NOS enzymes. NOS are dimeric, multidomain enzymes that synthesize NO from molecular oxygen and l-arginine and use iron protoporphyrin-IX (heme), tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), FAD, flavin mononucleotide (FMN), and NADPH as cofactors (204, 904). The architecture of these proteins is complex, with a oxygenase/heme domain that binds BH4 and heme, in which the oxidation of arginine to NO using molecular oxygen takes place, and a reductase domain evolutionarily related to cytochrome P450 reductase (CYPOR) that binds the cofactors FAD and FMN (204, 377). The reductase domain uses NADPH as electron source to reduce the FAD and FMN and finally transfer the electrons to the oxygenase/heme domain (FIGURE 2). Between both domains, there is a calmodulin (CaM) binding domain that regulates the electron shuttling between the reductase and oxygenase domains. To add to this complexity, the electron transfer between domains occurs between the reductase domain of one monomer and the oxygenase domain of the other monomer; thus, only the dimer is able to generate NO catalytically.

FIGURE 2.

Architecture of nitric oxide synthases (NOS). A: the arrangement of the domains in the NOS monomer. The oxygenase/heme domain (red) is connected to the reductase domain by a flexible linker, containing a calmodulin (CaM) binding sequence. The reductase domain includes a flavin mononucleotide (FMN)-binding domain (orange) that shuttles electrons from NADPH/FAD to the heme group and a FAD-containing domain (yellow) that uses NADPH as an electron source. B: the binding of CaM (blue) to NOS promotes electron transfer from the FMN domain of one monomer to the heme domain of the other monomer. C: three-dimensional structure model of NOS. The figure is assembled from the separated structures of the human endothelial NOS oxygenase domain (PDB:4D1O) (574), the CaM binding peptide bound to CaM (PDB:2N8J) (740), and the structure of the neuronal NOS reductase (PDB:1TLL) (338).

The role of NOS enzymes in vascular function and pathobiology has been extensively studied (277, 299, 569, 790). In this study, we will summarize the most relevant concepts about the function and regulation of the NOS isoforms in health and disease states.

NOS enzymes comprise three main isoforms: nNOS (NOS I), iNOS (NOS II), and eNOS (NOS III). Among these isoforms, eNOS is the enzyme more abundant in vascular endothelial cells and has the most significant impact on vascular function, with a variety of pathologies related with eNOS dysfunction. However, the specific roles of iNOS and nNOS in vascular disease are not to be ignored and will be also discussed below.

1. eNOS

eNOS is the constitutive NOS form in endothelial cells (ECs), and as such, it is the main contributor to vascular NO levels in physiological conditions (446). For example, the infusion of a competitive inhibitor of eNOS into the human systemic or coronary circulation decreases basal blood flow by ~25% (146, 722). Basal levels of NO produced by eNOS not only regulate blood flow but tonically inhibit platelet activation and the expression of inflammatory adhesion molecules on endothelium. The role of eNOS in the maintenance of optimal cardiovascular function is also highlighted by the experiments with eNOS-deficient mice. eNOS deletion has some limited effects on mouse blood pressure and vasodilation, as adaptive processes increase the production of nNOS and prostaglandins (444, 913). However, eNOS−/− mice show impairments in angiogenesis and wound healing (563). In the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout (KO) atherosclerosis model, addition of the eNOS deletion accelerates the atherosclerotic process (533). Notably, overexpression of eNOS is also detrimental (708), highlighting the delicate balance of eNOS function.

Although eNOS is predominantly expressed in the endothelium (Table 1), and the ECs are proposed to regulate NO signaling in the vasculature, a number of recent studies using chimeric cross bone marrow transplant mouse models have shown that the red blood cell also expresses a functional eNOS that contributes in part to systemic blood pressure responses (181, 536, 1025). This erythrocyte eNOS can contribute to endocrine NO signaling to modulate both blood pressure and myocardial injury and appears to be tonically regulated by arginase through the availability of the eNOS substrate l-arginine (1044).

Table 1.

Tissue distribution of NOS isoforms in the cardiovascular system

| Tissue | Cell Types | Cellular Location | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nNOS (NOS1) | Heart | ECs | Plasma membrane | 114, 126, 599, 841, 977, 1037 |

| Lung | VSMCs | Caveolae | ||

| Blood vessels | Adventitial fibroblasts | Sarcoplasmic reticulum | ||

| Cardiomyocytes | ||||

| iNOS (NOS2) | Heart | ECs | Plasma membrane | 126–128, 521, 525, 604, 688, 698, 867, 903, 984, 1064 |

| Lung | VSMCs | Phagosomes | ||

| Blood vessels | Adventitial fibroblasts | Golgi | ||

| Cardiomyocytes | Mitochondria | |||

| Macrophages and other leukocytes | ||||

| eNOS (NOS3) | Heart | ECs | Plasma membrane | 126, 181, 283, 358, 518, 819, 878, 1025 |

| Lung | VSMCs | Lipid rafts | ||

| Blood vessels | Cardiomyocytes | Caveolae | ||

| Erythrocytes | ||||

| Platelets |

EC, endothelial cell; eNOS, endothelial NOS; iNOS, inducible NOS; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; nNOS, neuronal NOS; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

eNOS is constitutively expressed; a number of posttranslational modifications impact the ability of eNOS to produce NO, from changes in the NO production rates to, in some cases, the complete blockade of NO synthesis (296). The relative presence of these modifications is critical to enzyme activity. General measurements of eNOS protein such as the determination of monomer/dimer ratio by Western blot or a single phosphorylation site status show a necessarily simplistic view of the activity of eNOS in cells. A deeper analysis of the main regulatory factors of eNOS activity, including individual phosphorylation sites, other posttranslational modifications, and the levels of the cofactors and substrates, with special interest on tetrahydropterin/dihydropterin (BH4/BH2) ratios and l-arginine/asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) concentrations are necessary for a better assessment of the eNOS function in vivo and the assessment of endothelial dysfunction conditions. In this section, we will describe the regulation of eNOS activity by posttranslational modifications; the role of the cofactors BH4 and l-arginine and their counterparts BH2 and ADMA, and the role of arginases and l-arginine transport metabolons will be treated in sect. IIIB. A detailed study on other regulatory mechanisms, including protein/protein interactions, shear stress, and other mechanisms, has been provided by other reviews (59, 296, 299, 870).

a) phosphorylation.

A number of amino acids have been shown to be phosphorylated in human eNOS (296, 669). Because of their impact in eNOS activity, the more relevant phosphorylation sites are Thr495, Ser1177 (Ser1179 in bovine eNOS) and Tyr657. Other phosphorylation sites include Tyr81, Ser114, Ser615, and Ser633 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Posttranslational modification sites in human eNOS

| Site | Kinase | Effect of Modification | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | |||

| Thr495 | PKC | Impairs CaM binding | 297, 407, 646 |

| AMP kinase | Decreases NO synthesis rates | ||

| Constitutive | Can cause uncoupling through the reductase domain | ||

| Ser1177 | Akt | Activates electron transfer through the reductase domain | 74, 236, 321 |

| PKA | Increases NO synthesis rates | ||

| AMP kinase | |||

| CaMKII | |||

| Tyr81 | Src | Slight increase in activity | 320, 322 |

| May be involved in Ca2+/CaM sensitivity | |||

| Ser114 | Constitutive | 74, 327 | |

| Ser615 | PKA | No change in NO synthesis | 74, 647 |

| Akt | May modulate protein/protein binding interactions | ||

| Ser633 | PKA | No change in NO synthesis | 74, 647 |

| PKG | |||

| Tyr657 | PYK2 | Decrease in NO synthesis | 292 |

| Glutathionylation | |||

| Cys382 | Not determined | 160 | |

| Cys689 | Decrease flow through the reductase domain | 162 | |

| Decreased NO synthesis | |||

| Can cause uncoupling through the reductase domain | |||

| Cys908 | Decrease flow through the reductase domain | 162 | |

| Decreased NO synthesis | |||

| Can cause uncoupling through the reductase domain | |||

CaM, calmodulin; NO, nitric oxide

The activation of eNOS requires Ca2+ and CaM; however, changes in resting Ca2+ concentrations are not strictly necessary to regulate NO synthesis by eNOS. In turn, CaM affinity to eNOS is regulated via phosphorylation of Thr495. Thr495 is located in the CaM-binding site of eNOS, and the phosphorylation of Thr495 impairs CaM binding, thus blocking Ca2+/CaM-dependent activation of the enzyme (741). In resting endothelial cells, Thr495 is generally phosphorylated (297). The phosphorylation has been attributed to protein kinase C (PKC) (297, 646), and the residue is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (646). The equilibrium between phosphorylated and dephosphorylated Thr495 is mainly modulated by the changes in intracellular Ca2+ levels. Thus, bradykinin and Ca2+ ionophores promote Thr495 dephosphorylation and eNOS activation. Ser1177 phosphorylation activates electron flow through the reductase domain and, hence, increases NO synthesis in functional eNOS. Ser1177 is located in the C-terminal portion of eNOS in a helical C-terminal tail element that blocks flavin reduction and regulates the conformational equilibrium of the reductase domain (404, 631). The mechanism is similar to that described for nNOS Ser1412 (7, 947). In resting cells, Ser1177 is usually not phosphorylated. Phosphorylation is induced by a variety of signals, and the kinases involved are dependent on the inducing factor (Table 2). Some agonists like bradykinin and Ca2+ ionophores can induce Thr495 dephosphorylation via PP1 and Ser1177 phosphorylation via activation of CaMKII at the same time. Shear stress activates Ser1177 via PKA-dependent phosphorylation. VEGF, insulin, and estrogens promote Ser1177 phosphorylation via Akt kinase.

Tyr657 is located in the FMN domain of eNOS in close proximity to the FMN cofactor. The mutation of Tyr657 (292) causes complete loss of NO synthesis and l-citrulline formation, suggesting a blockade of the intramolecular electron transfer. Thus, Tyr657 phosphorylation effectively inactivates eNOS. The phosphorylation of Tyr657 is catalyzed by proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PYK2). This kinase is activated in endothelial cells by several stimuli including angiotensin II, oxidative stress, and insulin (296). The detrimental role of this phosphorylation on NO synthesis has spurred interest in the pharmacological inhibition of PYK2 for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (94, 628, 869, 983).

b) glutathionylation.

Recent reports indicate that eNOS can also be modified posttranslationally by S-glutathionylation (162). At least three residues have been shown to be susceptible: Cys689, Cys908 (162), and Cys382 (160) (Table 2). The process can be reversed by glutaredoxin-1 and thioredoxin (160, 907). The reaction increases eNOS uncoupling and the formation of superoxide with diminished NO synthesis activity. Glutathionylation appears to be a detrimental modification caused by oxidative stress conditions (162, 522) and is very sensitive to the ratio of oxidized and reduced glutathione (160).

c) s-nitrosation.

S-nitrosation of eNOS has also been reported (777). This reaction is also dependent on eNOS myristoylation and Ser1177 phosphorylation and involves the nitrosation of the Zn-binding cysteines (Cys96 and Cys101 in the bovine eNOS) (271, 272). As a consequence of S-nitrosation, the formation of the eNOS dimer is blocked, resulting in the loss of NO synthesis. Denitrosation of Cys96-NO and Cys101-NO restores eNOS activity. Additional studies using mutant eNOS Cys96Ser and Cys101Ser, which cannot be S-nitrosated, indicate that the enzymatic activity is not altered by treatment with NO donors, confirming a role for the modification of these thiols in the regulation of eNOS activity (271).

d) other posttranslational modifications.

eNOS can be acylated at different residues. The myristoylation of the N-terminal glycine targets eNOS to the membrane (284), whereas the palmitoylation of Cys15 and Cys26 targets eNOS specifically to caveolae (82, 336). These modifications are not expected to change the intrinsic NOS activity but are important to modulate eNOS localization and function.

Hyperglycemia can result in N-acetyl glycosylation of Ser1177. This modification results in a nonphosphorylable Ser1177 and limits eNOS response to agonists and vasorelaxation (257, 280, 1035).

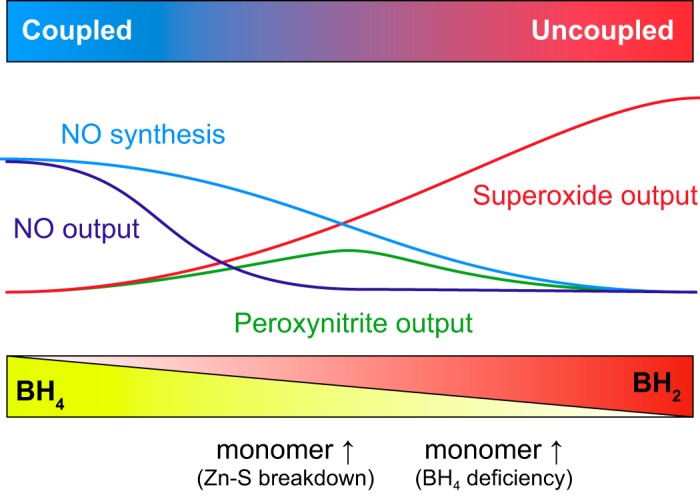

In summary, we want to remark that the generation of NO by eNOS in optimal conditions, at least as studied in vitro with saturating concentrations of coenzymes and substrates and absence of deleterious modifications, is a well-balanced process with a very limited production of superoxide as a side reaction. However, a number of circumstances can lead to changes in the NO generation cycle and trigger the production of superoxide instead of NO. These processes are generally termed “eNOS uncoupling” as the consumption of reducing equivalents by eNOS is no longer coupled to the formation of NO and is instead driven to the generation of superoxide from molecular oxygen. This process is largely deleterious and has been linked to endothelial dysfunction and other vascular pathologies. eNOS uncoupling will be discussed in sect. IIIB along with other mechanisms of superoxide generation.

2. iNOS

Unlike eNOS and nNOS, which are constitutively expressed enzymes regulated via CaM binding and posttranslational modifications, iNOS has a much higher CaM affinity, so it binds CaM at very low Ca2+ concentrations, and thus, its activity is not regulated by Ca2+/CaM but mainly at the level of gene transcription (169). The kinetic parameters of iNOS lead to a catalytic activity that generates higher NO levels than eNOS and nNOS, is less sensitive to NO-dependent autoinhibition, and generates higher levels of other nitrogen species, such as nitrate (816, 904).

The expression of iNOS is usually limited to airway epithelium and neuronal cells (Table 1), where it is highly expressed and active under basal conditions (604, 984, 1064), and activated macrophages and hepatocytes, where it is expressed in the setting of inflammatory stimuli (688).

Although healthy cells in the vasculature do not present significant levels of iNOS, several pathologic processes show increased iNOS activity in blood vessels (386, 704, 727). As iNOS can generate higher NO levels than eNOS, this iNOS activation leads to excess NO and severe impairment of vascular function. This effect is mediated by several pathways including continuous activation of sGC and competition for BH4 with eNOS (386). Overall, the excess NO limits the response of blood vessels to vasodilators and decreases NO sensitivity (263).

As pointed out, iNOS expression is prevalent in macrophages. In these cells, iNOS induction is necessary for the generation of high levels of NO in the phagosome and bacterial lysis and, therefore, is a basic tool for the innate immune response (519, 688). However, in pathological situations, increased NO synthesis can be deleterious (e.g., in macrophages recruited to the atherosclerotic plaque). The high rate of NO production by iNOS, together with superoxide formation from iNOS or other sources, can lead to the production of peroxynitrite (see sect. IVA) (222, 624, 981, 1034), a very toxic oxidant and nitrating agent (78, 709). Studies in which iNOS deletion was added to the ApoE−/− atherosclerosis model indicate improved cardiovascular function in the ApoE−/−iNOS−/− mice compared with ApoE−/− controls, indicating a detrimental role of iNOS in atherosclerosis progression (532).

Finally, it should be noted that iNOS-derived NO can also have positive effects in certain conditions. iNOS activation has been identified as a mechanism of protection against ischemia/reperfusion damage. This observation appears to be related to a preconditioning effect caused by increased levels of NO (109, 483, 579, 1009).

3. nNOS

Similar to eNOS, nNOS is a constitutively expressed form of NOS activated by CaM binding. NO synthesis rates for nNOS are generally higher than eNOS, but also tightly regulated by Ca2+/CaM (unlike iNOS), and nNOS is also very susceptible to feedback inhibition by NO (4, 902). This enables nNOS to produce NO in a pulsatile manner instead of generating sustained low levels. These features appear to be more related to its role in synaptic transmission (811, 812). Although nNOS is commonly found in neurons (120), it is also found in other tissues including vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), adventitial fibroblasts, ECs, and cardiomyocytes (114, 126, 599, 841, 1037) (Table 1). Expression levels of nNOS in the vasculature are lower than for eNOS; however, there is increasing evidence of important functions for nNOS-derived NO in vascular physiology (188).

Early experiments in rodents indicated an important role of nNOS in the regulation of cerebral blood flow (731). Selective inhibition of nNOS causes increases in blood pressure and decreased response to acetylcholine in normotensive rats (139). In eNOS−/− mice, nNOS can be activated by shear stress, partially compensating the loss of eNOS in the vasculature (444, 547). Experiments with nNOS KO mice indicate increased neointima formation in carotid artery ligation and balloon injury models (666), indicating that nNOS appears to limit vascular injury independently of eNOS. To investigate the role of nNOS in atherosclerosis, the nNOS−/− deletion was incorporated in mice carrying the ApoE−/− deletion. The double deletion indicates a protective role for nNOS in the development of atherosclerosis, as the mice carrying both deletions showed accelerated progression of the disease (534).

The effects of nNOS in the human vascular system have been demonstrated by studies with nNOS-specific inhibitors. These works indicate that NO synthesis from nNOS has definite roles in the vasodilatory response, including, but not limited to, microvascular tone and coronary flow (498, 843, 844).

Another relevant pathway for nNOS-dependent NO signaling not mediated by sGC is the formation of S-nitrosothiols (462). This function has special relevance in brain function in health and neurodegenerative diseases (686). A more specific description of S-nitrosation and its signaling potential is presented in sect. IID.

4. Pharmacological regulation of NOS enzymes

There have been significant efforts to develop specific NOS inhibitors for research and pharmacological purposes (17, 752).

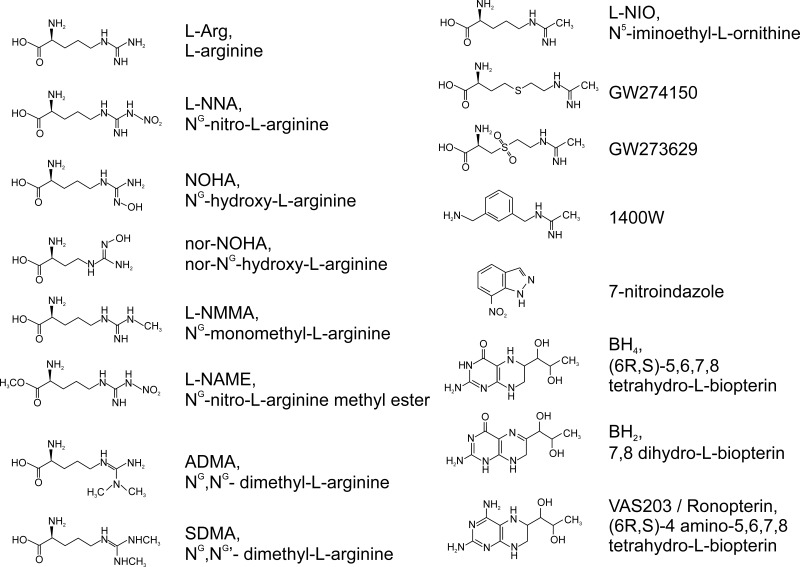

a) nonisozyme-specific nos inhibitors.

Early research indicated that analogs of the substrate l-arginine had inhibitory properties on the three NOS isoforms. Among these, NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) and NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA) and its precursor NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) were characterized as general NOS inhibitors and continue to be broadly used in research, especially l-NAME (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 3.

Chemical structure of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) substrate l-arginine, tetrahydrobiopterin, and selected NOS inhibitors.

b) 7-nitroindazole.

7-Nitroindazole (7-NI) (FIGURE 3) is one of the earliest inhibitors showing isoform specificity. Although it was shown that all three isoforms can bind 7-NI with very similar affinity (17), in vivo studies showed inhibition of nNOS without significant effects in blood pressure, a surrogate of eNOS inhibition (664). It appears that 7-NI may have differential properties in cell permeability, with limited uptake in endothelial cells (402). Thus, although 7-NI cannot be accurately described as a specific nNOS inhibitor, it can behave as such in vivo.

c) 1400w.

N-[3-(aminomethyl)benzyl] acetamidine (FIGURE 3) is a specific inhibitor of iNOS (344). It remains one of the most widely used NOS inhibitors in research because of its cell and tissue permeability. Its selectivity seems related to the irreversible effect on the faster reacting iNOS, whereas the inhibition on nNOS and eNOS is reversible. A similar effect is observed in N(5)-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (l-NIO) (FIGURE 3) (279).

d) GW273629 and GW274150.

These sulfur-substituted acetamidine amino acids (FIGURE 3) are specific inhibitors for iNOS (16). With safer toxicity profiles than 1400W, GW273629 and GW274150 have been used in clinical trials for migraine (437, 965) (NCT00242866; NCT00319137). Although both compounds were ineffective, it is not clear if this is due to pharmacokinetic issues (965).

e) vaS203.

The pterin 4-amino-tetrahydrobiopterin (VAS203) (FIGURE 3) is a BH4 analog that can inhibit all NOS proteins by replacing the BH4 cofactor (1008). VAS203 has shown efficacy in the treatment of traumatic brain injury and has been used in phase II clinical trials (897) (NCT02012582).

The structural similarities between isoforms (and particularly between eNOS and nNOS) have made the development of specific eNOS and nNOS inhibitors particularly challenging. Structure-based inhibitors have allowed the development of new inhibitors with improved isoform specificity (337, 752). Cell permeability and other pharmacokinetic considerations have precluded the clinical use of novel inhibitors; however, newer compounds have been developed; for instance, novel-specific nNOS inhibitors have been tested in animal studies (29, 254, 255, 1051). The further development of new clinically available specific inhibitors for NOS, in particular for the iNOS and nNOS isoforms, is to be expected.

B. Nitrite-Dependent Nitric Oxide Synthesis

Despite early indications to the contrary (124, 329), nitrate and nitrite have been often overlooked as inert NO oxidation metabolites circulating in plasma and in cells. However, during the last two decades, a novel paradigm of nitrite as a source of NO, especially in hypoxia, has emerged (184, 185, 216, 364, 366, 369, 600, 603, 861, 968). Indeed, it has become increasingly accepted that the routes for the production of NO in vivo are not only oxidative (as in NOS) but also reductive (particularly by nitrite-reducing proteins such as globins and molybdopterin enzymes). These pathways can work synergistically to maintain NO levels in response to changes in oxygen tension. We foresee this theme of synergistic oxidative and reductive pathways to be potentially relevant to the generation of other reactive species in health and disease.

A few years after the discovery of the role of NO as the endothelial-derived relaxing factor, increasing evidence supported the presence of nonenzymatic NO generation (89, 605, 1075). These studies and observations of arterial-to-venous gradients of nitrite in the human circulation indicated a potential role for nitrite as a NO source in vivo (369). Subsequent studies have extended this notion to a more global paradigm that encompasses the role of nitrate and nitrite as part of a cycle of NO generation that includes both enzymatic and nonenzymatic processes.

Nitrate and nitrite can enter the circulation through the dietary intake of nitrate-rich foods, particularly leafy green vegetables (1002). In addition, NO generated from NOS enzymes is eventually oxidized to nitrate and nitrite as well. Mammals do not possess efficient systems for nitrate reduction, but oral commensal bacteria have enzymatic nitrate reduction pathways able to generate significant amounts of nitrite from nitrate reduction in the saliva (467, 602). Nitrate is not only acquired from dietary sources but is also concentrated from the blood into the saliva via the salivary glands, pumped through the sialin transporter (761). After consumption of nitrate-rich foods (beet root, spinach, kale, etc.), the concentration of nitrate and nitrite in saliva can reach levels as high as 10 mM and 2 mM, respectively (601). A portion of this nitrite is eventually absorbed into the circulation. Studies using antiseptic killing of the mouth microbiome, or systemic NOS inhibition, suggest that about half of basal plasma nitrite comes from the salivary reduction of dietary nitrate and the other half from the oxidation of NO produced mainly by eNOS (485, 557, 763, 865). NO oxidation to nitrite is proposed to occur via the oxidase activity of plasma ceruloplasmin (865).

Once nitrite accumulates in the plasma, the reduction of nitrite to NO in the vasculature is mediated by several proteins, including deoxygenated Hb (deoxyHb) (185). Increased physiological levels of nitrite in plasma from a nitrate-rich diet can lower blood pressure (554). The effect is dependent on the generation of nitrite from oral bacteria, as antiseptic mouthwash can eliminate both the increase in circulating nitrite and the blood pressure decrease (485). Subsequent studies have further validated the link between nitrite levels and improved cardiovascular function (486, 502).

Numerous metal-containing proteins have been shown to catalyze the reduction of nitrite to NO. These proteins generally contain a heme or molybdopterin cofactor. The presence of many of these proteins in diverse components of the vasculature, including blood cells, blood vessels, and heart tissue, makes them relevant for the generation of NO in vascular biology. In the subsequent sections, we will discuss the known mechanisms for nitrite reduction that are relevant for cardiovascular function. We also note that, to date, existing evidence indicates a role for Hb, Mb, and XO on biological NO generation, whereas the role of the other possible mechanisms in vivo are still a matter of discussion.

1. Inorganic nitrite reduction

Along with the role of different proteins in the reduction of nitrite, a number of nonenzymatic processes can reduce nitrite to NO in vivo. In general, these systems require concerted electron and proton donation, which is optimal at lower pH and hypoxic conditions, thus making them particularly relevant in ischemic events (1074, 1075). The simplest mechanism involves the disproportionation of nitrite, a process accelerated at acidic pH as it requires the protonation of nitrite to nitrous acid (HNO2). Two molecules of nitrous acid, then disproportionate, to form N2O3 and water (Eqs. 1–4)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

This process is prevalent in very low pH conditions, as in the stomach (89, 605). In fact, this mechanism has been shown to be responsible for nitrite-dependent increases in gastric mucosal blood flow (98) and may relate to the role of nitrite in host defense as acidified nitrite is a potent antimicrobial agent (99, 261).

Several molecules present in cells have been shown to reduce nitrite to NO. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is a widely present cellular antioxidant that can catalyze the reduction of nitrite to NO in vitro (205). This effect is also observed with in vivo infusions of ascorbic acid and nitrite (217). Polyphenols can be assimilated through the diet and, like vitamin C, can reduce nitrite to NO (325, 733, 834).

Dietary interventions have indicated improved vascular function linked to the consumption of polyphenols from different sources, including cocoa and dealcoholized red wine (60, 168, 225, 417, 834). Combined use of polyphenols and nitrite appears to have additive effects in vascular protection (791). The effects of these dietary components can be, in part, due to the interaction with different enzymatic systems (30, 558, 824), but the link between these compounds and NO formation deserves further investigation (600, 789).

2. Heme proteins

Heme proteins have emerged as critical parts in the generation of NO under hypoxia. The specific role of globins in nitrite reduction and NO homeostasis has been studied in recent reviews (39, 770, 931). It should be noted that competing reactions, namely the scavenging of NO by the ferrous heme [rate constants in the order of 1.7 × 107 to 1.5 × 108 M−1s−1 (180, 967), Eq. 6] and the rate of NO dioxygenation [rate constants in the order of 3.4 × 107 to 8.9 × 107 M−1s−1 for mammalian Hb/Mb (264, 341), Eq. 8] greatly decrease the amount of bioavailable NO generated by the reactions of nitrite with heme proteins (931). However, nitrite-dependent NO generation in vivo catalyzed by Hb and Mb is well documented (183, 185, 365, 862, 975); it is very likely that the measurement of this NO generation is due to the fact that the high concentrations of Hb and Mb (in the mM range) can overcome the low efficiency of the nitrite reduction reaction.

a) hb.

The ability of deoxyHb to reduce nitrite has been extensively documented (124, 248, 366, 447). Initial reports by Brooks demonstrated that deoxyHb reacts with nitrite, generating nitrosyl Hb and methemoglobin, consistent with electron transfer from a ferrous Hb to nitrite (124). The studies by Huang et al. (445) confirmed the overall stoichiometry of two molecules of deoxyHb generating one molecule of nitrosyl Hb and one molecule of methemoglobin (Eq. 7), consistent with electron transfer from a ferrous Hb to nitrite and indicated the critical influence of pH in the process. By studying the same reaction using alkyl nitrites, which do not show a pH dependence in their reaction rates with deoxyHb, it was established that the reaction of nitrite requires a proton and thus formally requires nitrous acid (247, 248). This property also makes the reaction faster in low pH conditions. The overall process can be written as (Eqs. 5–7)

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

This scheme has been found to apply to virtually all the heme protein–mediated nitrite reduction reactions studied to date, including Hb (248, 447), Mb (247, 862), neuroglobin (Ngb) (932, 945), Cygb (182, 571, 780), cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) (149, 350), globin X (184), plant and cyanobacterial Hb (phytohemoglobins) (905, 946), flavohemoglobin (340), heme-albumin (43), cytochrome c (41), protoglobin (40), and microperoxidase-11 (42).

The reaction of deoxyHb with nitrite shows an increase in the instantaneous reaction rate as the reaction progresses (447). Studies with T-state and R-state Hb–stabilizing compounds have unambiguously identified the reason for this change is the shift from T-state to R-state during the course of the reaction, as the NO formed in the reaction binds to the unreacted deoxyHb to stabilize the R-state. This process is referred to as R-state autocatalysis. The rate constants for the reaction of Hb with nitrite change from 0.12 M−1s−1 for T-state Hb to 6.0 M−1s−1 for R-state Hb (Table 3) (447). As the distribution of R-state and T-state Hb in vivo are regulated by oxygen concentration, this phenomenon has important relevance for the reaction in vivo. In fact, the reaction of Hb with nitrite has been modeled mathematically at different oxygen tensions. The combination of a faster rate at higher oxygen, but increased availability of deoxyHb at low oxygen, leads to bell-shaped dependence of the observed rates versus the oxygen concentration with the maximal rates of NO generation around 50% Hb oxygen saturation, consistent with experimental data (367, 368, 794).

Table 3.

Rate constants for the reaction of nitrite with selected deoxygenated heme proteins

| Protein | K, M−1s−1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | ||

| Human (T-state)a | 0.12 | 447 |

| Human (R-state)a | 6 | 447 |

| Myoglobin | ||

| Horse hearta | 2.9 | 945 |

| Sperm whalea | 5.6 | 945 |

| Neuroglobin | ||

| Human (S-S)a | 0.12 | 945 |

| Human (SH)a | 0.062 | 945 |

| Cytoglobin | ||

| Humanb | 0.14 | 571 |

| Humanc | 1.14 | 182 |

| Cystathionine-β-synthase | ||

| Humand | 0.6 | 350 |

100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 25°C; b100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 25°C; c100 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 37°C; d100 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 37°C.

b) physiological implications of hb-dependent nitrite reduction.

The functional implications of the Hb-dependent nitrite reductase reaction remains a subject of intense research, particularly in the context of viable physiological models of erythrocytic NO transport (366, 424, 591). There is consensus in the field that NO-erythrocytic interactions regulate vascular function, particularly that oxygen desaturation of red blood cell Hb stimulates increased vascular NO bioavailability, leading to NO-dependent hypoxic vasodilation (266). However, the molecular mechanism of this regulation is more contentious. Three models by which this erythrocytic regulation of NO production occurs have been proposed: 1) hypoxic release of ATP from the red blood cell (882) that stimulates endothelial NO production by binding to endothelial purinergic receptors, 2) the S-nitrosation of cysteine 93 of the β-chain of Hb (SNO-Hb) (866), and 3) the reduction of nitrite by deoxyHb (as described above) (425).

Understanding the role of each of these potential mechanisms is an ongoing area of interest. The SNO-Hb hypothesis proposes that SNO-Hb is formed when Hb is oxygenated (R-state) in the lungs and remains stable. Once Hb becomes deoxygenated (T-state), the SNO-Hb reacts with existing thiols to release a vasodilatory signal (471, 728, 886). In the last 25 years since this proposal, numerous groups have debated key elements of the hypothesis including the mechanism of SNO-Hb formation and release and physiological levels of SNO-Hb. Additionally, a genetic murine model in which the cysteine 93 of β-Hb was replaced with alanine (and in which SNO-Hb formation was abolished) demonstrated no impairment in hypoxic vasodilation, questioning the role of SNO-Hb in physiologic hypoxic vasodilation (454). Importantly, more recent studies have shown that the β-93 cysteine KO mouse shows more cardiac injury in ischemic conditions, suggesting that SNO-Hb may play a more prominent role in cardiac rather than vascular function (1060).

With regards to the nitrite reduction hypothesis, human studies show a significant gradient of nitrite from the arterial to venous circulation, concomitant with the production of NO (detected as iron-nitrosyl Hb) in the venous circulation (185, 369). In vitro experiments in isolated aortic rings demonstrate that nitrite mediates vasodilation in conditions of Hb deoxygenation (185, 196). Consistent with these experiments, infusions of physiological nitrite concentrations mediate vasodilation in humans, which is enhanced during exercise and not affected by NOS inhibition. This effect is accompanied by iron-nitrosyl Hb formation, consistent with nitrite reductase chemistry (185).

A central controversy relevant to all theories of erythrocytic NO transport is the question of how NO generated can escape the red cell without reacting with Hb. Although theoretical calculations suggest that this type of NO escape should be limited, accumulating studies by many research groups now demonstrate the production of bioavailable NO generated from the incubation of erythrocytes with nitrite (185, 196, 883, 975). The production of NO gas has been measured by chemiluminescence in vitro from the reaction of deoxygenated Hb, Mb, or erythrocytes with nitrite. More physiological biosensor experiments demonstrate that incubation of nitrite with erythrocytes can induce cGMP production and inhibit activation in platelets coincubated with this reaction (591, 883, 975). The mechanism for NO release remains unclear but has been postulated to involve the formation of NO+ (684) or N2O3 as intermediates (69). Additionally, NO escape may relate to the localization of its formation, particularly at the surface of the erythrocyte (813) or via concerted reactions of NO and autoxidation of oxygen to form NO and NO2 (N2O3) at partial oxygen saturations (i.e., the reactions of nitrite with both oxygenated Hb and deoxyHb at around 50% Hb oxygen saturation) (384). More work is needed to understand the biophysics of NO signaling from the erythrocyte during nitrite reactions with deoxygenated red blood cells and Hb.

c) mb.

The physiological relevance of the reaction of Hb with nitrite suggested that similar processes could involve the closely related globin, Mb. The ability of Mb to catalyze nitrite reduction to NO was first confirmed in vitro. Consistent with the monomeric structure of Mb and its lack of allosteric regulation, the reaction rate is constant through the reaction, with a bimolecular rate constant similar to that of R-state Hb (Table 3) (447). In vitro studies of isolated mitochondria in the presence of Mb and nitrite have shown that Mb-dependent NO is bioavailable and can inhibit mitochondrial respiration in a similar manner to a conventional NO donor (862). In the cardiovascular system, the heart is the most relevant organ for the function of Mb as a nitrite reductase. In a murine myocardial infarction (MI) model, nitrite has been shown to decrease infarct size, and this effect was lost in Mb KO mice, which cannot reduce nitrite to NO (774). Through this mechanism, cardiac Mb is thought to be critical for the reduction of circulating nitrite accumulated through diet or through the therapeutic process of remote ischemic preconditioning, which mediates cardioprotection (267, 775).

d) ngb.

Ngb is a recently discovered six-coordinate globin that is evolutionarily related to Hb and Mb (134). The physiological function of Ngb is unknown, although because of its generally low concentration in cells (with the exception of the retina in the eye), it is probably not related to oxygen transport and storage as Hb and Mb are (38, 39, 133). It was recently demonstrated that, as observed with other globins, deoxygenated Ngb can also reduce nitrite to NO (932, 945). Furthermore, this process is redox regulated by the redox state of two surface thiols. Thus, oxidation of two cysteine residues to form an intramolecular disulfide bond doubles the rate of nitrite reduction (Table 3). This redox transition occurs in a physiologically relevant range and can be controlled by the cellular GSSG/GSH ratios (945). It appears that Ngb is not present in vascular cells, except for sympathetic nerves (898). The reaction of Ngb with nitrite may have implications for microcirculation in the brain, where several studies have found a vasoprotective effect of Ngb (140, 503, 917).

e) cygb.

Like Ngb, Cygb is a six-coordinate globin discovered in the early 2000s (132, 493, 951). Cygb is ubiquitous in human tissues, mainly found in fibroblasts and cells of related lineage such as osteoblasts and chondroblasts, but also in other cell types, including neurons (403, 687). Interestingly, it has been identified in VSMCs (398, 571, 594). Cygb can reduce nitrite to NO at rate constants similar or slightly higher than Ngb (182, 571) (Table 3). In addition, the oxygenated form of Cygb reacts with NO to form nitrate in a NO dioxygenation reaction that scavenges NO (339) (Eq. 8)

| (8) |

This reaction is common to most heme proteins (264, 341, 342, 931). In practice, this indicates that Cygb expression can regulate the diffusion of NO and possibly prevent excessive vasodilation at high levels of NO, not unlike the proposed role of α-Hb in vascular endothelial cells (898). This role has been proposed for Cygb in the vascular endothelium (398, 593, 594). It should be noted that the scavenging of NO is more efficient at high O2 tensions, which favor the formation of the ferrous/oxygenated heme species, whereas nitrite reduction would be prevalent when the oxygen concentration is low, and the ferrous/deoxygenated species is more abundant. Thus, both processes can synergize to regulate the concentration of NO (593, 594). The presence of an efficient reduction system for Cygb in smooth muscle cells via cytochrome b5 and cytochrome b5 reductase further supports the possible relevance of these processes in vivo (25, 593).

f) cbs.

CBS is a pivotal enzyme for the metabolism of homocysteine (649). Mutations in the CBS gene are associated with hereditary homocystinuria (531). CBS binds heme and 5′-pyridoxal phosphate. The 5′-pyridoxal phosphate group is critical for the reaction of homocysteine with serine or cysteine, whereas the role of the heme domain in the catalysis of CBS in unknown, but this heme appears to be functional and redox active (868). The CBS-mediated reduction of nitrite to NO by the CBS heme has been recently reported (149, 350). The reaction proceeds with rate constants similar to these of T-state Hb, Ngb, or Cygb (Table 3) (149, 350). The presence of CBS in endothelial cells (809) suggests that CBS could play a role in vascular nitrite reduction in vivo.

g) nos.

As NOS proteins contain a heme group, it is conceivable that they can catalyze the reduction of nitrite as observed in other heme enzymes. Indeed, in anoxic conditions, eNOS has been shown to catalyze nitrite reduction to NO (970). The contribution of eNOS to nitrite reduction could be significant in specific tissues, including red blood cells and kidney (654, 998).

3. Molybdoproteins

The relevance of molybdopterins in the generation of NO in the vasculature has been increasingly appreciated since this reaction was first described for XO (650, 1061). As the molybdopterin group does not react directly with oxygen or NO, these reactions that decrease NO release from heme proteins do not limit Mo-dependent nitrite reduction reactions. Thus, the reduction rates by molybdoproteins can be relevant in vivo at lower rate constant values as compared for heme protein reduction rates. The reduction of nitrite by all four mammalian molybdenum-containing enzymes has been characterized. Recent reviews on the nitrite metabolism by molybdenum enzymes are available (614, 616).

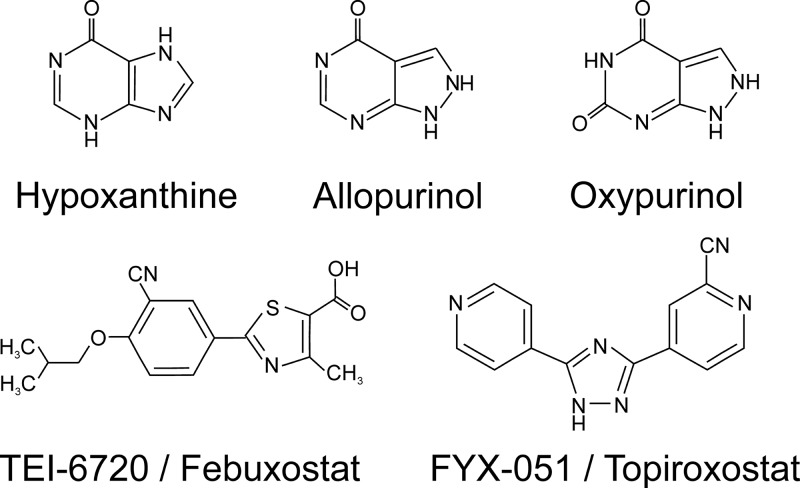

a) xo.

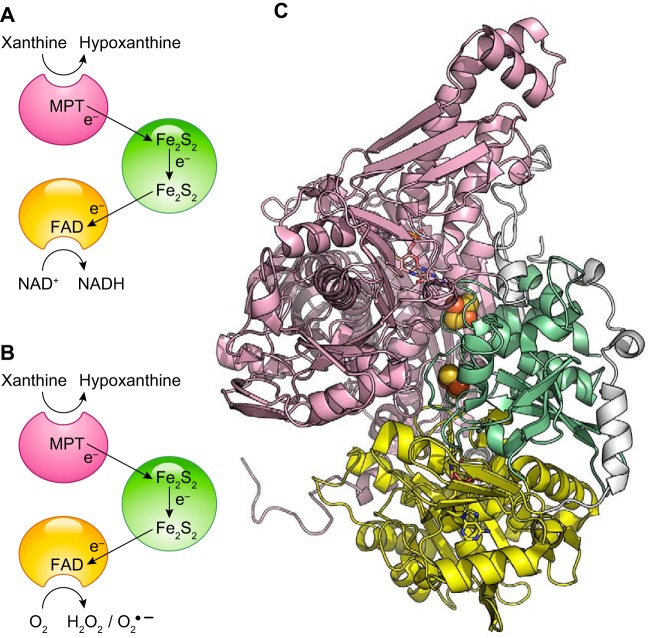

Mammalian molybdopterin-containing enzymes catalyze different oxidation-reduction reactions including, but not limited to, xanthine oxidation, sulfite oxidation, and drug metabolism processes (839, 840). To our knowledge, the ability of mammalian Mo-containing enzymes to reduce nitrite to NO was first described for XO (370, 578, 650, 1061). Earlier work had shown the ability of XO to also reduce nitrate to nitrite (50, 308). Subsequently, several reports have shown that all mammalian Mo-containing enzymes [XO, aldehyde oxidase (AO), sulfite oxidase, and the mitochondrial amidoxime-reducing component (mARC)] are able to reduce nitrite at different intrinsic rates (Table 4) (575, 880, 990).

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters for the reaction of nitrite with selected molybdopterin proteins

| Protein | kcat, s−1 | KM, mM | K, M−1s−1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xanthine oxidase | ||||

| Human, pH 7.4a | 0.41 | 2.2 | 186 | 616 |

| Human, pH 6.3b | 1.2 | 0.67 | 1800 | 616 |

| Rat, pH 7.4a | 0.55 | 1.9 | 289 | 616 |

| Rat, pH 6.3a | 0.58 | 0.25 | 2300 | 616 |

| Aldehyde oxidase | ||||

| Human, pH 7.4a | 0.47 | 4.1 | 115 | 616 |

| Rat, pH 7.4a | 0.67 | 3.6 | 186 | 616 |

| Rat, pH 6.3a | 0.66 | 0.43 | 1500 | 616 |

| Sulfite oxidase | ||||

| Human, pH 7.4c | 0.002 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 990 |

| Human, pH 6.5c | 0.004 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 990 |

| mARC-1 | ||||

| Human, pH 7.4d | 0.1 | 9.5 | 11 | 880 |

Reaction contains 50 μM of reductant (aldehyde); breaction contains 750 μM of reductant (aldehyde); creaction contains 5 μM of reductant (sulfite); dreaction contains 1 mM NADH, 0.2 μM cytochrome b5 reductase and 2 μM cytochrome b5.

Although the architecture of these enzymes is variable, existing evidence indicates that the reduction of nitrite takes place in the molybdopterin site, where Mo reduces nitrite to NO in a single electron transfer reaction similar to that of the heme proteins (615, 616) (Eqs. 9 and 10)

| (9) |

| (10) |

Depending on the redox potential of the enzyme, nitrite reduction may occur by either of the two reactions or only by Mo4+ (Eq. 9) pathways or one specific pathway (614, 616). The pH dependence of the reaction is not linear as in the case of the heme-dependent reactions, probably because of the protonation of important catalytic residues at low pH that offsets the effect of the increased proton concentration. These circumstances lead to a maximal rate for XO-dependent nitrite reduction around pH 6.3 (Table 4) (617). As noted above, unlike nitrite reduction by heme, the Mo cofactor does not bind NO. Thus, this reaction potentially has a higher yield of free NO.

In the vasculature, XO has been identified in the surface of epithelial cells, endothelial cells (5, 798, 979, 1010), and erythrocytes (357, 998). To date, XO is the most relevant nonheme nitrite reductase in vivo. Many studies have shown the relevance of XO in mammalian physiology (357, 568, 577, 578, 998). The use of specific XO inhibitors such as allopurinol and oxypurinol has allowed the determination of specific XO effects on nitrite reduction and NO metabolism (357, 568, 575, 998).

b) ao.

AO is a molybdenum-containing protein with high sequence and structural similarity to XO. Its function is yet unknown, although it has been related to the metabolism of retinoic acid, neurotransmitters, and a variety of xenobiotics (513, 756, 920). AO has been shown to reduce nitrite to NO, albeit a slower rate than XO (Table 4) (568, 575, 617, 1001). As observed for XO, the pH dependence of nitrite reduction shows a bell-shaped pattern with a maximal rate around pH 6.5 (617). The relevance of AO-dependent nitrite reduction has not been studied in so much detail as for XO, but depending on their tissue abundance and the availability of their reducing substrates, some studies suggest that the magnitude of AO activity in the vasculature can be similar to XO (568, 745, 1073).

c) sulfite oxidase.

The molydopterin-containg sulfite oxidase catalyzes the oxidation of sulfite to sulfate, preventing the accumulation of toxic levels of sulfite. Impaired sulfite oxidase function leads to severe neurological damage and death (510). Like XO and AO, the molybdopterin cofactor of sulfite oxidase is able to catalyze nitrite reduction to produce NO (Table 4) (990). Unlike other molydopterin proteins, in sulfite reductase only the Mo4+ center, and not the Mo5+ species, is able to catalyze the reaction (990). The reaction has a marked O2 dependence with very low NO formation in the presence of O2. This is most probably related to the fast oxidation of the Mo4+ species to Mo6+ by molecular oxygen as observed in other molybdopterin proteins (880, 990).

d) marc 1 and 2.

Two isoforms of the mARC are expressed in mammals (705). Sequence homology suggests that mARC proteins belong to the sulfite oxidase family. The structure of the mARC proteins has not been elucidated, but electron paramagnetic resonance data seem to support these similarities (1043). mARC proteins have a not yet understood physiological function. Existing evidence suggests that they may be involved in the detoxification of N-hydroxylated substrates; mARC enzymes are required for the detoxification of some hydroxylamines (706). mARC can also catalyze the reduction of the NOS reaction-intermediate NG-hydroxy-l-arginine to l-arginine in a reaction that may be involved in NO biosynthesis (528).

Both mARC enzymes can reduce nitrite to NO in a process very sensitive to oxygen-mediated inhibition (Table 4) (880). As mARC enzymes can use the cytochrome b5 reductase/cytochrome b5 system as a source of electrons, the three proteins can form a mitochondrial metabolon for the reduction of nitrite to NO under hypoxic conditions (880).

4. Other proteins

a) carbonic anhydrase.

The reduction of nitrite by carbonic anhydrase has been described (1). Unlike heme- or molybdenum-containing proteins, the Zn2+ in the active site of the carbonic anhydrase is not redox active, thus invoking a nitrite anhydrase mechanism as described in Eqs. 1–4. Such reaction would be of notable interest in vascular physiology because of the ubiquitous presence of carbonic anhydrase in erythrocytes; however, this activity remains highly controversial (615).

b) cytochrome c.

The electron carrier cytochrome c has also been noted as a situational nitrite reductase. As cytochrome c is a six-coordinate heme protein with no distal site available for nitrite ligation, the reaction is only observable in conditions where the protein is partly unfolded, a situation that can be elicited by cardiolipin or other anionic phospholipids (477). In the presence of cardiolipin-containing liposomes, cytochrome c has been shown to catalyze nitrite reduction to NO in a reaction that may be prevalent in apoptotic processes (68).

c) cyp and cypor.

The heme P450 cytochromes (CYPs) are involved in a wide range of detoxification processes. CYP 2B4 and microsomal rat liver CYP fractions have been characterized as nitrite reductases (576). Notably, the associated CYP-reducing protein, CYPOR, can reduce nitrate to nitrite, forming a metabolon that can tentatively catalyze the complete process from nitrate to NO (576).

C. The NO Receptor sGC and the Modulation of Vascular Tone

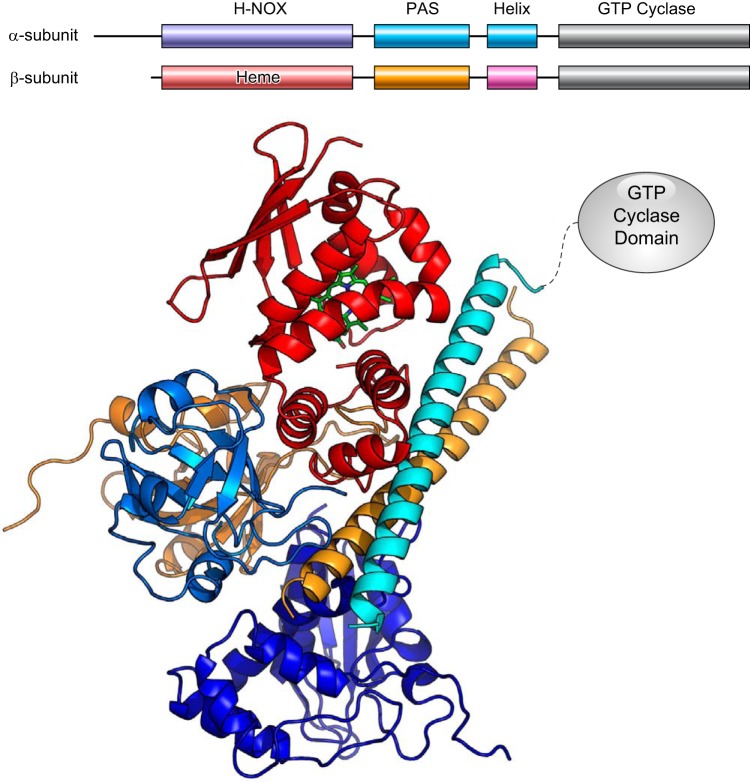

1. Structure and function of sGC

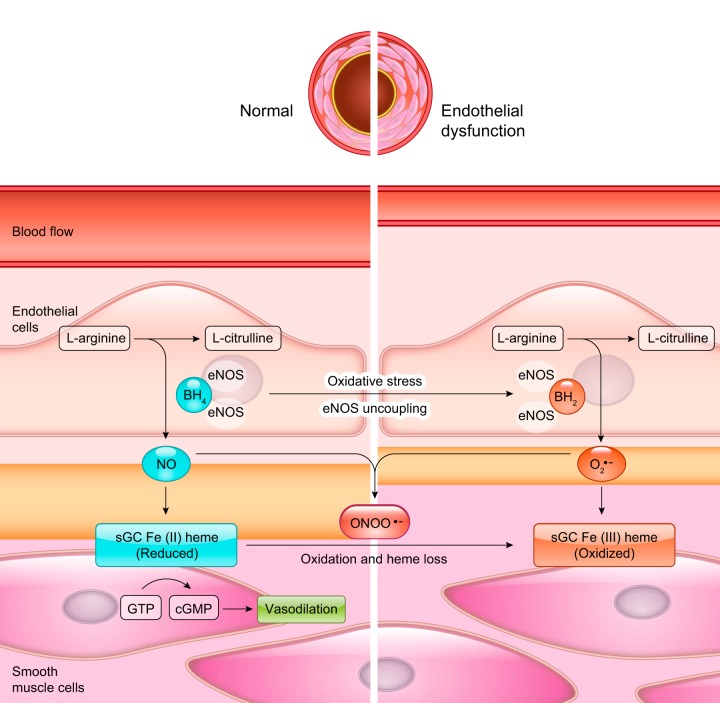

The effects of NO in the vasculature at concentrations in the nM/pM range (397) are mainly mediated through the activation of the canonical NO receptor sGC (223, 662, 711, 751). sGC is a cytosolic, heterodimeric protein comprising two homologous subunits, α and β. Although at least two isoforms for either α and β subunit exist (termed α1, α2 and β1, β2) with different tissue distributions (129), the α1β1 heterodimer is the most common form. Each monomer contains four domains: an N-terminal heme-binding domain, a Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain, a helical/coiled coil motif, and a C-terminal, guanylyl cyclase domain that catalyzes the formation of cGMP from GTP (FIGURE 4). It should be noted that despite the homology between the N-terminal domains, only the N-terminal domain of the β subunit binds heme (489). The heme domain in the β subunit is the NO-sensing center of sGC. Remarkably, unlike most other hemoproteins that bind oxygen, CO and NO, this heme group shows a high selectivity toward NO and can also bind CO weakly but shows no affinity toward molecular oxygen (625). When NO binds to the heme, changes in the heme coordination cause a conformational change in the N-terminal heme domain that relieves an inhibitory interaction between the heme domain and the catalytic C-terminal domain, activating cGMP synthesis (1017). The exact details of the conformational changes that mediate enzyme activation are not yet known and are the focus of ongoing structural studies (145, 313, 958).

FIGURE 4.

Architecture of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC). Top: arrangement of sGC domains in the sequence of α and β subunits. Bottom: model for the interaction of the N-termini domains of the α and β subunits of human sGC. Domains are colored according to the top panel. Catalytic GTP cyclase domains are not shown. The model for the human sGC protein is based on the model for Manduca sexta sGC derived from chemical cross-linking, small-angle X-ray scattering, and homology modeling (312, 313, 662).

The activation of sGC by NO leads to an increase in cGMP synthesis of at least two orders of magnitude (895). cGMP exerts a number of downstream signaling effects on phosphodiesterases such as PDE5 and other targets including cGMP-dependent kinases and cGMP-gated ion channels, eliciting a vasodilatory response (673, 674, 993).

Apart from changes in NO levels or downstream signaling, the activity of sGC itself is compromised in a number of pathological conditions (355, 363, 600, 853, 888, 1022). Situations directly related to sGC that can account for a decrease in sGC activity include changes in the expression of sGC, defective incorporation or loss of sGC heme, a deficient reduction of the sGC heme iron, leading to an NO unresponsive ferric enzyme, posttranslational modifications, ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation, and defects in cGMP synthesis.

Changes in sGC related to the mRNA transcript have been described. For example, expression of a variant α2 subunit (α2i) containing a 31 amino acid insertion has been shown in different tissues. This subunit can form a dimer with β1 but produces an inactive sGC form (80). Alternatively, several splice variants of the α1 and β1 monomers have been identified in vivo (626, 787, 852). These splice forms can be related to decreased sGC activity and appear to be more abundant in disease conditions such as aortic aneurysm (626).

The incorporation of the heme group in the sGC β1 monomer is regulated by the chaperone heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) (95, 354, 356, 818). This process is also regulated by NO, with low NO doses improving Hsp90/sGC interaction and heme insertion, whereas high NO blocks heme insertion (354, 985). The relevance of heme-free sGC in the context of cardiovascular disease is not well characterized. Several lines of evidence suggest the presence of pools of heme-free sGC in vivo (354, 356, 799, 943), and it is reasonable to expect that the exacerbated ROS conditions that exist in the origin and development of many cardiovascular pathologies can promote heme oxidation and subsequent heme loss (312, 363, 888). Thus, a plausible therapeutic strategy can target the inactive, heme-depleted sGC by use of agonists (activators) that can bind to the empty heme site activating the enzyme. Some examples of these drugs are discussed in the next section.

In addition to the presence of heme-free protein, it is increasingly appreciated that a pool of ferric sGC can also exist in smooth muscle cells (641, 769, 891). As noted, the oxidation of the heme iron is probably the intermediate step in the generation of free-heme sGC (312, 363, 888). The generation of ferric sGC is one of the mechanisms of sGC desensitization, and this form of the protein, whereas nonresponsive to stimulator drugs, can be rescued by sGC activators (302, 891). Recent work indicates that CYB5R3 (methemoglobin reductase) may mediate the reduction of ferric sGC to NO-responsive ferrous sGC in cells (769). These findings open the possibility of novel pathways to regulate sGC responses in blood flow regulation and for targeted therapy in diseases associated with oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction.

Posttranslational modifications of sGC have been also described. Prolonged exposure to NO has been long known to cause a decrease in sGC activity, usually characterized as sGC desensitization (85, 671, 831). This process is related to some of the tolerance profiles observed for NO donor treatments (459). sGC desensitization is probably due to different concurrent mechanisms, including S-nitrosation and heme iron–nitrosylation. Recent reports indicate that several cysteine residues in sGC can undergo S-nitrosation, leading to decreased activity (93, 822, 823). The formation of a heme iron–nitrosylated form of sGC, which has decreased guanylyl cyclase activity, has been reported (953). Ubiquitination of sGC targets the protein for proteosomal degradation, a process that can be inhibited by sGC activators (643). Further research on these sGC modifications, and interventions to prevent their occurrence, is ongoing (92).

2. Pharmacological regulation of sGC

Because of the pivotal role of sGC in the regulation of the NO response, substantial efforts have been made to develop pharmacological regulators of sGC function. In theory, direct targeting of sGC offers notable advantages, bypassing the complex mechanisms that may limit NO generation and availability under pathological conditions (FIGURE 5). Two main groups of compounds, activators and stimulators, have been developed with different mechanisms of action. In both cases, the target of the drugs appears to be the NO-sensing, heme domain of the β subunit (662). A large number of sGC agonists have been developed over the last three decades; we discuss below a few of the more widely studied compounds. For a more complete view of the development of these and other sGC-related drugs, the reader is referred to more specific reviews (274, 302, 888).

FIGURE 5.

Soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) function in healthy and endothelial dysfunction states. Oxidative stress conditions cause oxidation of BH4 to BH2, superoxide production in the endothelial cells, and promote oxidation and heme loss in smooth muscle cell sGC.

a) stimulators.

Stimulators are compounds that enhance the activity of functional sGC and require the presence of ferrous (Fe2+) heme-bound sGC. These compounds can cooperate with endogenous NO-mediated activation.

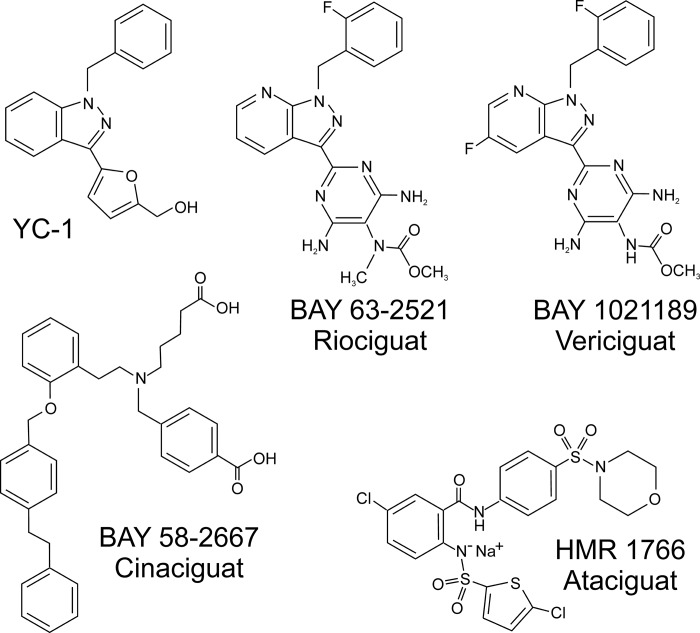

The benzyl indazole YC-1 (FIGURE 6) was the first developed sGC stimulator (524). The effects of YC-1 on sGC activation were found to be synergistic with NO donors and required heme-bound sGC (310, 436, 896). The compound presented some limitations and a lack of specificity with cGMP-independent effects and inhibition of PDE5 (309, 326, 991). Based on YC-1 structure, a number of optimized compounds have been developed such as BAY 41–2272 and BAY 41–8543 (889). These compounds are more specific than YC-1 and despite some poor pharmacokinetic properties, have been extensively used in research (105, 353, 670, 760, 764, 852, 889).

FIGURE 6.

Chemical structure of selected soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) stimulators and activators.

Further studies led to the development of another YC-1–related compound, BAY 63–2521 (riociguat) (83, 655) (FIGURE 6). Riociguat (commercialized as Adempas) was approved in 2013 by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (351, 352).

Another second-generation stimulator compound is BAY 1021189 (vericiguat) (301) (FIGURE 6), which has completed Phase IIB trials (287, 349, 744) and is currently in Phase III clinical trials for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (301) (NCT02861534).

B) activators.

sGC activators are compounds that can trigger the catalytic activity of sGC independently of the redox state of the sGC heme or even in the absence of bound heme. In general, these compounds work as heme analogs, replacing the heme group and triggering a similar conformational change to that of NO-bound heme in the native enzyme, thus activating cGMP formation (302).

High-throughput screening assays led to the discovery of a novel series of sGC regulators that do not require the sGC heme. The first developed drug in this category was the compound BAY 582667 (cinaciguat) (890) (FIGURE 6). Apart from the recovery of sGC synthesis, it was noted that BAY 582667 could limit the degradation of heme-oxidized and heme-free sGC (643). Cinaciguat showed promising results in animal studies and acute decompensated heart failure (553), but the trials were stopped because of the development of low blood pressure (269).

Another sGC stimulator that has reached clinical use is HMR 1766 (ataciguat) (827) (FIGURE 6). Phase II clinical trials are currently evaluating the effect of ataciguat on aortic valve calcification (NCT02481258).

D. S-Nitrosothiols and the Modulation of Vascular Function

1. S-nitrosation and vascular function

Although activation of sGC is considered the predominant mechanism of NO-dependent signaling, it is now recognized that posttranslational modification of cysteine residues by S-nitrosation comprises a significant alternative mechanism of NO signaling. The first protein shown to be S-nitrosated was albumin (885), and its existence was first proposed to represent a reservoir of NO bioactivity. However, S-nitrosated albumin is now considered to be a product of more detrimental NO “scavenging” by the protein (332, 956). It is now well recognized that a plethora of proteins of various function and localization are S-nitrosated physiologically or in pathological conditions. For example, as described above in sect. IIB2, S-nitrosation of Hb is an active area of research and SNO-Hb has been considered a reservoir of NO activity. In this regard, decreased levels of SNO-Hb have been reported in conditions such as pulmonary hypertension and hypothesized to contribute to disease pathogenesis (586, 729).

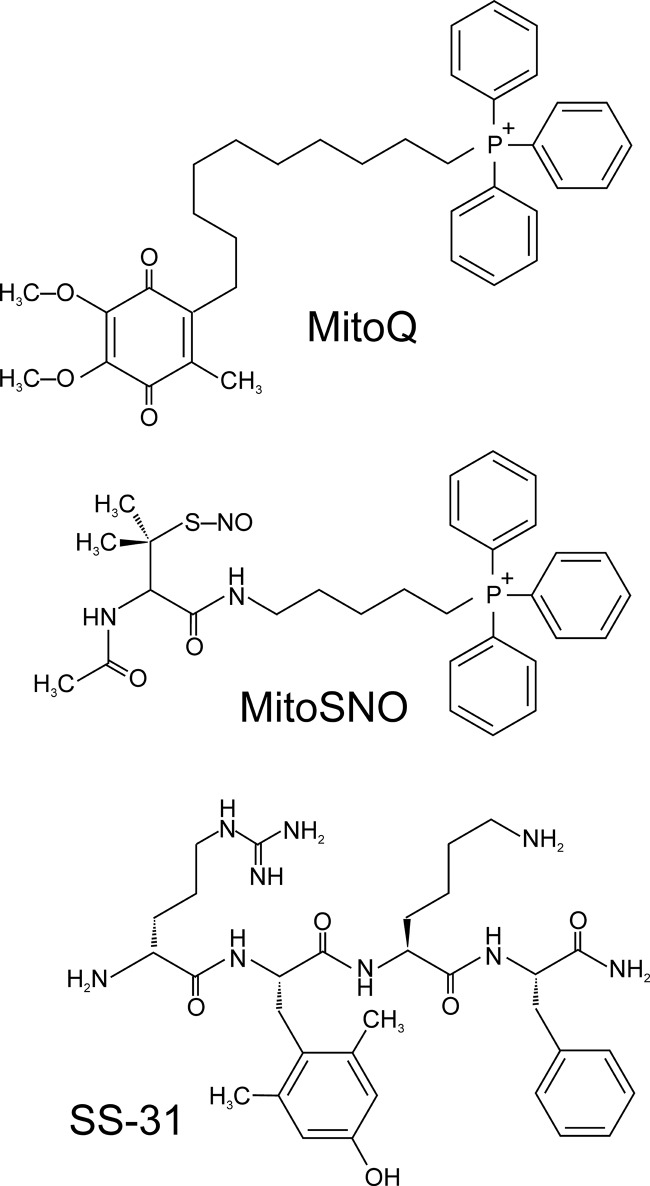

Accumulating studies demonstrate that beyond simply representing a reservoir of NO activity, S-nitrosation is a mechanism of enzymatic regulation. S-nitrosation of specific cysteine residues can modulate enzymatic activity and function. One prototypical example of this paradigm is the type 2 ryanodine receptor (RyR2). The RyR2 is a Ca2+ release channel that releases Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum to mediate cardiac excitation/contraction coupling. The magnitude and duration of Ca2+ release from through the RyR2 determines contractility of the myocyte. Although the RyR2 contains many surface-exposed thiols, physiological S-nitrosation of specific cysteine residues activate the protein and contribute to maintainance of healthy excitation contraction coupling (1038). A lack of this S-nitrosation has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias as well as heart failure (131, 372, 373). Similar to the RyR2, a multitude of enzymes have now been shown to be activated or inhibited by S-nitrosation. Although review of all these proteins is beyond the scope of this manuscript, the S-nitrosation of mitochondrial complex I and its cardioprotective signaling is discussed in sect. IIIC3, and the S-nitrosation of eNOS as a regulator of its activity is outlined in sect. IIA1. The role of S-nitrosation in regulating cardiovascular function has been reviewed elsewhere (586, 677, 914).

In the following section, we review the chemical mechanisms by which S-nitrosothiols are formed. It is important to note that physiological levels of S-nitrosothiols are determined not only by the rate of S-nitrosation but also by protein denitrosation. Although S-nitrosothiols degrade through transnitrosation reactions (outlined below) and interaction with other low molecular–weight thiols, the existence of denitrosating enzymes has been reported. The best characterized enzyme in this class is S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR), a member of the aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme group, which catalyzes the denitrosation of glutathione and thus regulates the equilibrium of S-nitrosation (592).

2. Formation of S-nitrosothiols

The formation of S-nitrosothiols is, on occasion, described as the reaction of NO with a thiol (R-SH) group to generate a protein-bound nitrosothiol (R-SNO). However, it should be noted that NO is not a nitrosating species and does not react directly with thiols. Formation of S-nitrosothiols involves the reaction of the deprotonated thiol (R-S−) and a formal nitrosonium ion (NO+) (Eq. 11)

| (11) |

In physiological conditions, the thiolate is generally provided by glutathione or cysteine, yielding GSNO or Cys-NO, respectively. The nature of the nitrosating species can vary, generating different possible mechanisms for the reaction. Most of these routes require the formation of the nitrogen dioxide radical intermediate (NO2·) (Eqs. 12a, 12b)

| (12a) |

| (12b) |

The reaction of NO2· with a thiolate in the presence of NO can generate the S-nitrosothiol via a thiyl (RS·) radical (Eqs. 13a, 13b)

| (13a) |

| (13b) |

The reaction of NO2· with another molecule of NO2· or NO generates dinitrogen tetroxide (N2O4) or dinitrogen trioxide (N2O3), respectively, which are strong nitrosating species and can react directly with the thiolate (691, 692, 1018) (Eqs. 14a–d)

| (14a) |

| (14b) |

| (14c) |

| (14d) |

Peroxynitrite (sect. IVA), formed by the reaction of NO and superoxide, is another source of NO2·, either through homolytic decomposition, via peroxynitrous acid, into NO2· and OH· radicals (Eqs. 15a–b) or via reactions with CO2 (Eq. 15c) or metal centers (Eq. 15d)

| (15a) |

| (15b) |

| (15c) |

| (15d) |

These reactions leading to the formation of NO2· are well characterized (123, 548, 585, 1018). Global kinetic analysis of the reactions involved suggests that the main source of NO2· in vivo may be the decomposition of peroxynitrite (585). This result is consistent with the unfavorable rates for the direct formation of NO2· from oxygen and NO in vivo, (1018) although the exact mechanisms of formation remain a topic of current research (123, 872).

An additional pathway involves the formation of a ferric nitrosyl heme which can be in transient equilibrium with a ferrous-nitrosonium species (Eqs. 16a–c)

| (16a) |

| (16b) |

| (16c) |

Finally, the reaction of an existing S-nitrosothiol with a thiolate group can result in transnitrosation (Eq. 17)

| (17) |

Transnitrosation is a fundamental reaction of S-nitrosothiols and allows for the formation of GSNO or S-nitrosated proteins to mediate the formation of other S-nitrosothiols and probably serve as a reservoir for S-nitrosothiols in the cellular environment. Altogether, we want to note that the formation of the S-nitrosothiols is a complex process, and existing evidence indicates the requirement of significant concentrations of NO and usually the presence of superoxide and/or peroxynitrite.

The formation of S-nitrosothiols and their functional roles in vivo is a growing field, with protein S-nitrosation identified in most physiological pathways. It should be considered that the stability and precision of this modification is under intense study to determine its parallels with other protein modifications such as phosphorylation (1023, 1024). Recent studies of the proteome of eNOS−/− mice compared with wild type mice identify a more limited set of S-nitrosated proteins (125, 378). Altogether, it appears that the detection of S-nitrosated proteins in the presence of exogenous NO or R-SNO species can lead to nonphysiological S-nitrosation and more sensitive methods, monitoring protein S-nitrosation levels in vivo are necessary for accurate detection of these modifications.

III. SUPEROXIDE AND HYDROGEN PEROXIDE GENERATION AND VASCULAR FUNCTION

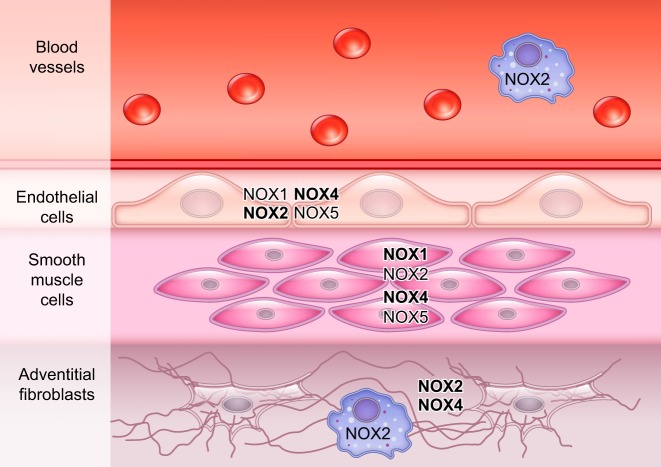

The presence of ROS in the vasculature has historically been considered detrimental and a consequence of abnormal generation and/or an inability of the endogenous reductant and antioxidant systems to scavenge these reactive species. The excess of superoxide, or other ROS, in the cell causes the modification of different parts of the cellular machinery and is a known player in the genesis and progression of cardiovascular disease (227, 408, 409, 570, 672, 700, 893). Conversely, the signaling properties of many of these molecules are increasingly recognized. Indeed, the generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, among others, has been shown to mediate critical processes such as angiogenesis, hypoxic adaptation, and energy homeostasis (96, 249, 291, 720, 778, 825, 960). In this section, we will discuss the main sources of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation in the vasculature and their endogenous and pharmacological regulation. Among these, NADPH oxidases (NOXs) appear to be the most important sources quantitatively. In healthy situations, the generation of ROS by eNOS, mitochondria, or XO is limited, and in the case of mitochondria, it is probably more related to signaling pathways (289, 290). However, there is significant evidence that not only NOXs but also the generation of ROS by uncoupled eNOS, mitochondria, or XO has particular relevance in the origin and development of cardiovascular disease.

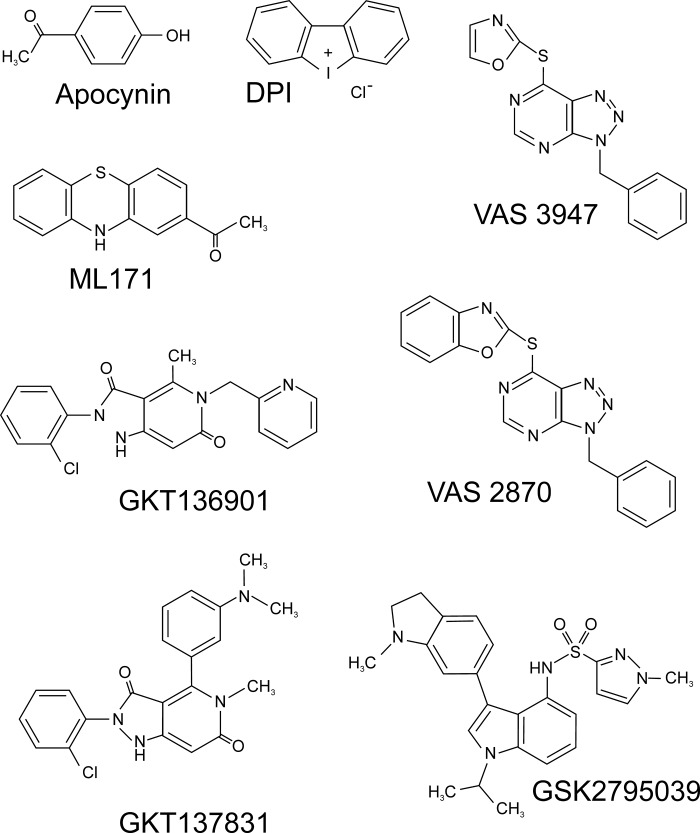

A. NOXs

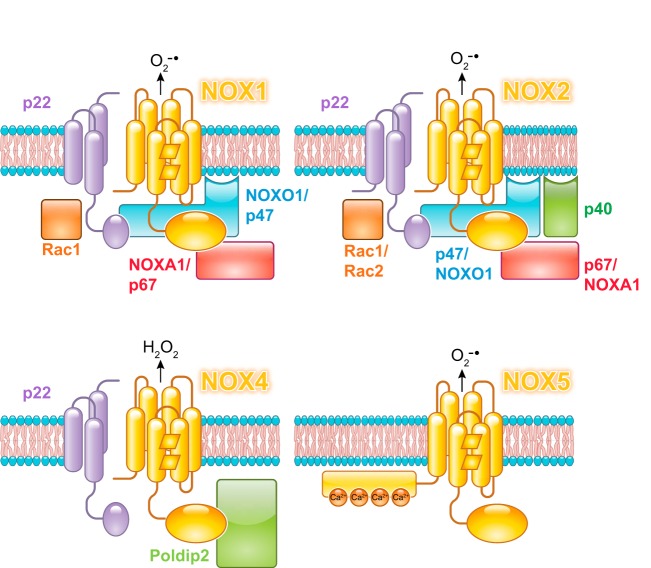

NOXs are multiprotein enzyme complexes that catalyze the electron transfer to molecular oxygen to form ROS, more commonly superoxide, but also hydrogen peroxide (79, 252, 383, 546, 912). To date, seven isoforms have been described [NOX 1–5 and dual oxidases (DUOX) 1 and 2]. Each isoform consists of a core, catalytic subunit with a transmembrane domain and a variable number of regulatory subunits. The core subunit defines the name of the NOX complex. Thus, NOXs complexes show differences in their molecular architecture, activator proteins, localization, and function. NADPH is the preferred substrate for all NOX isoforms, with the NOX2 isoform being particularly NADPH specific (48, 63, 177, 1047).

The putative mechanism of all NOX proteins can be described as an electron transfer chain in which electrons are transferred from NADPH to the FAD cofactor in the flavoprotein/dehydrogenase domain and from FAD to the heme moieties (Eqs. 18, 19), where molecular oxygen is reduced to superoxide. The specific mechanism of superoxide generation is still unknown. According to one hypothesis, the reduced (Fe2+) heme moiety binds oxygen to form a ferrous/oxy species that decays to ferric heme and superoxide (Eq. 20) (245, 980). Routes that do not involve the formation of a stable heme/oxy complex are also possible (Eq. 21) (456). Notably, the reaction of NOX1–3 and 5 generates superoxide, whereas NOX4 and DUOX1/2 produce hydrogen peroxide (26, 936). Existing evidence suggests that the primary species generated is superoxide in all isoforms, and the formation of hydrogen peroxide is mediated by the peroxidase-like domain in DUOX or by the dismutation of superoxide molecules in NOX4 (Eq. 22). The mechanism of NOX4 is still controversial, but elegant work by Takac et al. indicates that the E-loop (sequence between helices V and VI) of NOX4 shows notable differences with the other NOX isoforms (925). This loop in NOX4 seems to provide steric hindrance to slow down superoxide release, forcing two superoxide molecules to react with each other in a reaction that appears to be catalyzed, in part, by a histidine residue (925).

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20a) |

| (20b) |

| (21) |

| (22) |