Abstract

Objective

Mental illness has persistently been found to be a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the year after birth (the perinatal period). This study aims to explore barriers to detection, response and escalation of mental health-related life-threatening near miss events among women with perinatal mental illness.

Design

Qualitative study.

Participants

Healthcare professionals (HCP) working in psychiatry, maternity and primary care (n=15) across community and hospital maternity and perinatal services within the UK.

Methods

In-depth semistructured interviews were conducted with a range of healthcare professionals working with women during the perinatal period. An iterative process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis, informed by systems theories of healthcare and the Three Delays model, was employed to analyse the data.

Results

Three overarching themes were identified: recognition of severity, communication of risk and service provision and access to treatment. Differing perspectives of mental illness severity influenced how life-threatening situations among women with perinatal mental illness were described, recognised and communicated between teams. Under-resourced mental health service provision, particularly within emergency and specialist perinatal mental health services, unclear thresholds for escalating care and poor infrastructure for sharing information all contributed to delays in a timely response to crisis situations. Reluctance to prescribe medication or admit women to psychiatric hospital, stigma and missed appointments created further delays.

Conclusions

Response and escalation of care for life threatening near miss events among women with mental illness is strongly influenced by professional culture and understandings of mental illness embedded within different healthcare disciplines. Focusing on how differences in organisational and professional culture contribute to the recognition of severe mental illness and interdisciplinary communication may help facilitate clearer co-ordination between teams.

Keywords: qualitative, perinatal mental health, maternal mortality, near miss

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to explore maternal near misses among women with a range of perinatal mental illnesses, which identifies several important barriers to detection and response of life-threatening situations.

As a small explorative qualitative study of healthcare professionals in the UK, the study findings may not be generalisable to other settings.

Women’s perspectives are not explored within this study.

Introduction

Mental illness is common during pregnancy and the first year postpartum (the perinatal period), with major depression or anxiety affecting approximately 10% of women.1 Recent confidential inquiries into maternal deaths in the UK suggest that approximately a quarter (24%) of women who died between 2014 and 2016 had a mental illness and one in five women died from suicide in the year following birth.2 As such, maternal suicide is the third largest cause of direct maternal deaths occurring during or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy. However, it remains the leading cause of direct deaths occurring within a year after the end of pregnancy, with a mortality rate of 2.8 per 100 000 maternities.

A near miss approach can be a valuable method for studying the processes in place for recognising and responding to clinical deterioration, and has been widely adopted to study severe maternal morbidity.3 4 A maternal near miss is typically defined as ‘severe life-threatening complications not resulting in death’.4 Several tools for identifying maternal near misses exist,3 5 6 yet despite the high mortality in perinatal period relating to mental rather than physical health, they focus almost entirely on clinical indicators of physical health with limited consideration of mental health.7

This represents a significant research gap, since current approaches to investigating maternal morbidity and mortality rely on identifying preceding clinical characteristics associated with a worsening of condition. Developing strategies to identify women at risk of life-threatening mental illness is therefore of clear clinical importance in order to ensure that timely and appropriate intervention are available to those at greatest risk.

The purpose of this study is to explore potential barriers to detection, response and escalation of mental health-related life-threatening events among women with perinatal mental illness.

Methods

Design

Given the absence of prior research into psychiatric maternal near miss events, an exploratory qualitative study, using in-depth semistructured interviews with healthcare professionals (HCP), was adopted. Patient safety incidence, such as near miss events, are often under-reported; therefore, qualitative methodology may also be useful to explore in-depth the potential complexity of the barriers surrounding detection and response to maternal near miss events.

Participants and setting

This UK-based study aimed to recruit a sample of HCP working with women with mental illness during the perinatal period (ie, during pregnancy and up to the first-year post birth).

Purposeful and convenience sampling were used to recruit a national sample of HCP from five different healthcare disciplines (ie, Psychiatry, Psychology, Midwifery, Obstetrics and Health Visiting), across a range of healthcare settings (ie, inpatient, outpatient and community teams). Rigour and transferability were optimised by sampling respondents with differing characteristics.

Two main recruitment methods were used. First, convenience sampling was used to identify potential participants via direct emails to professional mailing lists and promotion of the study to professional groups via social media (ie, Twitter and Facebook). Second, purposeful sampling (based on healthcare discipline and setting, and geographical location in the UK) was adopted to identify and directly email potential participants that were not represented in the first round of sampling.

Interested participants received an information sheet and were offered the opportunity to discuss the study; those agreeing to participate provided written informed consent prior to the interview. Recruitment to the study was concurrent with data analysis, and data collection proceeded until no further unique themes were identified in successive interviews (saturation). Although there is no agreed method for establishing data saturation, after 15 interviews, a range of HCP experiences had been captured, and it was felt that no new themes were emerging and data saturation was reached.

Data collection

Interviews were semistructured and followed a topic guide. Questions were open-ended and iteratively revised following initial interviews to allow further exploration of the issues that arose. Due to differing definitions of near misses across different disciplines, following a brief exploration of what HCP thought of as a psychiatric near miss event, they were directed to focus on situations that they thought were life-threatening to the service user involved. All interviews were undertaken by one researcher (AE), by phone or face to face. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data were managed using qualitative software, NVIVO V.11. An iterative process of inductive and deductive thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke, was used to identify common themes in the data.8 AE read the transcripts several times to become immersed in the data. Initial line-by-line inductive coding was conducted, before grouping meaningful subthemes into overarching themes. Grouping of themes and subthemes was informed by two key theories, outlined below, to facilitate a more in-depth understanding of barriers to detection and response from a healthcare systems perspective, rather than solely focusing on individual-level factors. The emerging themes were used to modify the interview schedule and inform subsequent interviews and analysis.

Theoretical underpinnings

Data analysis and interpretation was informed by systems theories of healthcare,9 and the ‘Three Delays Model’.10 11

General systems theory views healthcare practices within the context of a complex and interacting system. It asserts that individuals (eg, patients, families, healthcare professionals) do not act in isolation; and therefore can only be understood by exploring the healthcare system as a whole and how different levels of the system interact. Factors that contribute to the healthcare system have been conceptualised as the interplay between three fundamental levels: micro (eg, individual patients and HCP and their interactions), meso (eg, the organisational context) and macro (eg, wider healthcare systems and political context).

The three delays model was originally proposed to help facilitate understanding of the factors that prevent or delay women from accessing safe maternity care. Delays are proposed to occur at three key points: (1) delay in seeking care, (2) delay in reaching care and (3) delay in receiving care once at an appropriate healthcare facility. The model has been used in a variety of international settings to help understand healthcare factors relating to maternal and perinatal mortality, and implement targeted changes in healthcare systems.

These theories were used to help structure the topic guide and help facilitate exploration of potential barriers at different levels of the healthcare system (eg, mico, meso and macro) and within a woman’s care pathway. To draw out the complexity relating to the number of healthcare professionals and disciplines involved in women’s perinatal mental healthcare, the analysis focused on desalinating differing perceptions between HCP.

All authors discussed the initial coding framework and emerging themes to ensure that alternative viewpoints had been considered, reviewed the thematic labels applied and agree on the final overarching and subthemes. This process helped to highlight alternative interpretations, which were reflective of the different academic and clinical background (maternity, psychiatry and psychology) of the research team.

Patient and public involvement

Feedback on the preliminary findings from the thematic analysis was sought from a patient and public involvement (PPI) group consisting of women, and family members, with lived experience of perinatal mental illness. Discussions held with the PPI group helped to refine the labels assigned to codes and themes, and their descriptions as presented in this manuscript. In addition, they have helped to identify areas for future research studies to further understanding of the support needs of women and families.

Results

Participants

A total of 15 HCP participated in the current study: five psychiatrists, five midwives, two health visitors, one general practitioner, one psychologist and one obstetrician. Participants were recruited from the following regions: East of England (n=3), London (n=4), North East England (n=2) South East England (n=1), South West England (n-1), the West Midlands (n=2), Yorkshire and Humber (n=1), Wales (n=1). Five participants were recruited via social media, four responded to mailing lists and six were purposefully recruited via direct email. Participant characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interview participants

| Participant number | Gender | Profession | Setting |

| 01 | F | Psychiatrist | Community Perinatal Psychiatry |

| 02 | M | Psychiatrist | Adult Psychiatry |

| 03 | M | Psychiatrist | Inpatient Mother and Baby Hospital |

| 04 | F | Midwife | Community Midwifery |

| 05 | F | Psychiatrist | Inpatient/Community Perinatal Psychiatry |

| 06 | F | General Practitioner | General Practice |

| 07 | F | Midwife | Community Midwifery/Maternity Hospital |

| 08 | F | Health Visitor | Community Health Visiting/Management |

| 09 | F | Psychologist | Outpatients Clinic |

| 10 | F | Midwife | Community Midwifery/Management |

| 11 | F | Psychiatrist | Community Perinatal Psychiatry |

| 12 | F | Obstetrician | Maternity Hospital |

| 13 | F | Health Visiting | Community Health Visiting |

| 14 | F | Midwife | Community Midwifery/Maternity Hospital |

| 15 | F | Midwife | Community Midwifery |

Inconsistent definitions and criteria

There was considerable inconsistency in how HCP conceptualised a maternal near miss or life-threatening event relating to mental health, which was driven by different definitions in use across the specialisms. The most typical examples were attempted suicides, although self-harm, harm to others and severe mental health relapses were also discussed.

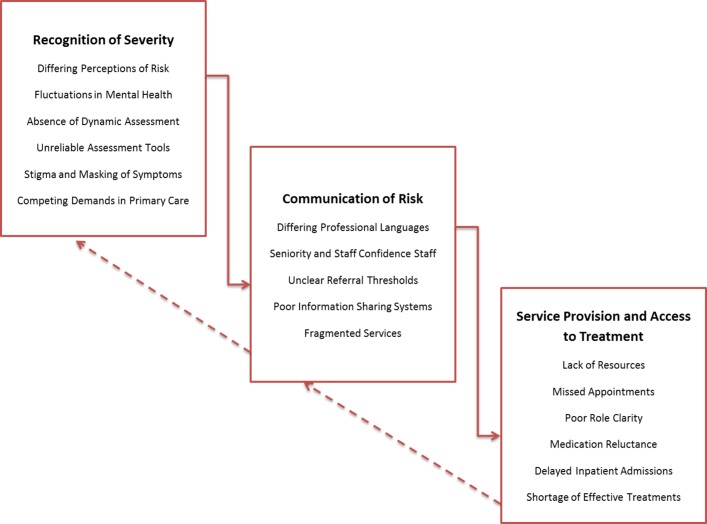

As depicted in figure 1, barriers to identifying and responding to a potentially life-threatening event in mental health occurred at three levels of the healthcare system: recognition of severity, communication of risk and service provision and access to treatment.

Figure 1.

Overview of themes and subthemes.

Recognition of severity

Differing perceptions of risk

A primary requisite to providing appropriate and timely mental health treatment is the ability to accurately determine the severity of a woman’s symptoms and level of risk. However, differing perception of risk and illness severity across healthcare disciplines acted as a key barrier to identifying the level of mental health assessment or treatment a woman needed. This impacted on detection and response to potentially life-threatening situations in two ways. Perinatal psychiatrists described situations where they felt that primary HCP (ie, midwives, health visitors and general practitioners) and non-perinatal psychiatry teams had underestimated the level of risk of a situation, which contributed to delays in accessing specialist care.

…she was someone who in the first two weeks postnatally she’d been referred to the CMHT [Community Mental Health Team] … but, because she wasn’t referred urgently (the GP was just a bit concerned) and she was sent an appointment, but by that time she’d already jumped [off a high building …but survived]. (Perinatal Psychiatrist)

By comparison, primary HCP frequently expressed difficulties escalating care for women that they perceived to be at risk of a life-threating event when their concerns were not shared by mental health teams. This was most often described within the context of self-harm and created uncertainty about whether self-harm represented a risk of a more life-threatening injury and frustration about a lack of prioritisation of such cases.

Maybe in their world of mental health it’s not so bad. Obviously for me, from my perspective we’ve got a woman who is doing that [harming] to herself and God knows what else she could do (Midwife)

Fluctuations in mental illness

Unlike many physical illnesses, which typically have a more linear deterioration prior to a maternal near miss, symptoms of mental illness and levels of risk can fluctuate over time, sometimes very rapidly.12 Fluctuation in symptom severity was identified as a fundamental challenge when trying to identify women at risk of a life-threatening event before it occurred.

…so in actual fact we assessed her as being relatively low risk but … she had just had a visit from her family which had been quite a distressing visit which had obviously changed the risk… In retrospect we didn’t respond appropriately to that. (Perinatal Psychiatrist)

Midwives and Health Visitors highlighted that this lack of regular enquiry about a woman’s mental health status throughout the perinatal period also created barriers to recognising signs of deterioration. Competing role demands sometimes meant that a woman’s mental health or well-being may not be asked about at each visit unless there was cause for concern. This was compounded by a lack of continuity of care, resulting in midwives being less able to detect changes in a woman’s mental health.

…it’s based on booking, so unless the woman actually comes back and says, ‘Do you know what? I’m not feeling very well, I’m not doing very well,’ it won’t be necessarily revisited again during pregnancy and also postnatally. (Midwife)

Risk assessment tools

Although HCP described tools available to assess women’s risk or symptom severity, it was apparent that these tools were not considered to be reliable or regularly implemented. In some cases, this led to disagreements among clinicians about the level of risk woman was presenting with, and contributed to difficulties in communicating risk between teams.

…we really just use a standard clinical interview really to find out what they are telling us and what we work out from psychiatric examination to tell us how risky they actually are. There isn’t really a standardized tool which works, I don’t think. (Psychiatrist)

Communication of risk

During the perinatal period, a range of HCP are involved in women’s care, communication within and between teams is therefore paramount to recognising and responding to high-risk situations; however, several communication barriers were identified.

Differing professional languages

Health Visitors and Midwives spoke about difficulties communicating symptoms and deterioration of mental illness to mental health teams, commenting that it felt as if they ‘spoke different languages’. Primary care staff felt that their training and professional background did not adequately equip them to convey concerns about a mothers’ mental health or accurately describe particular symptoms. In some cases, this resulted in several re-referrals to mental health services, potentially creating delays to receiving care.

…what I used to find is that health visitors would have an issue, a concern, and ring the mental health services, but because they weren’t really clear about what they were saying or what they were doing so they would say, ‘Well, it wasn’t accepted.’ I’d say, ‘Right, ring back and say this […]’ and give them the language. And then once you did that, the referral was accepted. It’s something about the language and the culture that each profession uses as well that makes it more likely that a woman will be seen appropriately. (Health Visitor)

This appeared to be compounded by a lack of confidence among junior primary care staff about communicating with specialist mental health teams in relation to illnesses outside of their discipline, whereas support from senior staff helped facilitate these conversations.

Unclear referral thresholds

During the perinatal period, clinical guidance in the UK recommends a lower threshold for referral and intervention for mental illness.13 However, HCP often described a sense of confusion and frustration about what symptoms would constitute a referral being accepted by secondary mental health teams. This was strongly related to themes of differing perceptions of severity between specialisms and difficulties communicating levels of risk in referral forms. Midwives and Health Visitors often felt that thresholds for secondary mental health services were too high, which led to referrals not being accepted and left primary healthcare professionals unsure of how to manage the mental healthcare of such women.

…we are working very much and saying if they have got these pre-existing conditions that the referral needs to go in and it needs to bypass the lower level of support. It needs to go straight through to the secondary levels so that the Perinatal [Mental Health] Team will pick it up. But it’s just very difficult to write the referral so that you can get it through to meet those thresholds. (Midwife)

By comparison, Psychiatrists sometimes expressed frustration in the number of ‘inappropriate’ referrals to mental health services, which they had limited capacity to manage.

On the referral form, we’ve got risk assessments, suicide risk or self-harm, we particularly highlighted them you could see that. The problem is … we’ve had women who’ve taken an overdose 10 years ago and then the nurses, the midwives read that and they put the highest score for suicide risk and actually it’s very historical. (Psychiatrist)

Poor information sharing and fragmented services

The ability to communicate risks and concerns between different health and social care professionals involved in women’s care was also impacted by a lack of integrated clinical records. HCP often spoke about managing the care of a woman but not being fully aware of involvement from other services, sometimes having to rely on women to provide information about their care.

I find that because we all have different IT systems where we keep our records, nothing speaks to each other; we don’t have access to each other’s records [….] I think that there are issues with that about the fact we can’t see what Mental Health have written, Mental Health can’t see what we’re writing, Social Care can’t see what any of us are writing. (Midwife)

Service provision and access to treatment

Lack of resources

A key theme from all interviews that contributed to missed opportunities for care among women with potentially life-threatening illnesses was a lack of resources for mental health service provision, which affected the capacity for response to high-risk situations. In addition, a lack of appropriate mental health emergency and crisis care services resulted in a deficiency of rapid response in the community. Several HCP viewed Accident and Emergency Departments (A&E) as inappropriate facilities for a mental health crisis, particularly during pregnancy, and highlighted women’s reluctance to attend A&E for their mental health.

In terms of getting the crisis team to attend or getting the GP to attend out of hours has always been… well a bit fraught really and not knowing who to ring for the best and the crisis team saying, ‘Yes, can send someone but it’s going to be six hours, which isn’t exactly considered a crisis. (Health Visitor)

Medication reluctance

It was apparent from some interviews that a reluctance to prescribe psychotropic medication or to recommend an inpatient admission during the perinatal period was also a factor that affected the type of treatment women received for mental illness during pregnancy or during early motherhood. Other interviews emphasised the role of the women and families in deciding to stop medication during the perinatal period which was felt to contribute to deterioration in mental health.

Sometimes there is sort of a resistance from psychiatry services to up medication and be more aggressive with it so that you can actually try and sort out the medical problem. (Obstetrician)

Missed appointments

HCP also spoke about how a perceived stigma and fear of social service involvement led to women ‘masking their symptoms’ from clinical staff or not attending clinical appointments, which created additional difficulties in spotting early warning signs.

It’s the woman who don’t attend or don’t disclose, I think they’re most at risk groups […] The women that I do see in the clinic are the ones at least I’m worried about, it’s those I’m not seeing are the ones I’m most worried about. (Psychiatrist)

Poor role clarity

Several HCP also highlighted that poor role clarity was also a factor that contributed to women deemed at risk of a life-threatening event not receiving an appropriate level of treatment. This was particularly the case in situations where a woman was currently well, but at high risk of relapse or severe mental illness in the postpartum period, which created confusion over whose role it was to monitor the well-being of a woman and escalate care if necessary.

She doesn’t get accepted (for mental health treatment) and then the response from perinatal is for the midwife to monitor and the GP to monitor. I came back and said, ‘There’s (so few) midwives in the team, and what exactly is this midwife, who is a midwife, monitoring? What exactly do want her to monitor? Secondly, what is this about the GP? Don’t we understand how GP’s work?’ Monitor what? […] ‘What do you mean monitor?’ Midwives are there to monitor the pregnancy, but we are not mental health nurses, we are not psychiatrists. (Midwife)

Psychiatrists described discharging women to the primary care staff who did not meet the threshold for specialist mental health services, but required closer monitoring and support. However, primary care staff often expressed feeling unclear or ill equipped in their role and how to monitor the mental healthcare of these women. Some midwives perceived the mental health of the women they were managing to be too severe or high risk and warranted greater support from mental health specialists, highlighting a lack of middle tier mental health services to monitor and support women who may be at risk of deterioration.

Discussion

Accurate identification and treatment of mental illnesses that may become life-threatening during the perinatal period is an important quality and safety issue and crucial to reducing the maternal death rate.14 15 This study illustrates several inter-related barriers to detection, response and escalation of mental healthcare in potentially life-threatening situations that occur at all levels of the healthcare system. Differing perceptions of risk and severity of mental illness between the various HCP involved in a woman’s perinatal care had significant consequences for how situations were interpreted and communicated between teams. In many cases, these barriers to communication were further compounded by a perception of a lack of reliable tools to assess risk, unclear thresholds for escalating care and poor infrastructure for sharing information.

These findings are consistent with recent maternal deaths inquiries which have found poor communication between maternity and mental health services to be a significant factor in many of the mental health-related deaths.16 In particular, the 2017 MBRRACE report highlighted that a narrow interpretation of risk (eg, that focused on a woman’s current symptom presentation) resulted in an under-recognition and treatment of women with mental illness.17 Healthcare communication is a complex process and this study emphasises the important influence of how signs of mental illness are interpreted and communicated, which was strongly embedded within HCP training and experiences, confidence and professional cultures. In order to improve communication between primary and mental healthcare professionals, there is a clear need to adopt strategies that target such cultural factors and help facilitate communication between teams.

Clinical guidelines in the UK recommend the use of two questions (‘the Whooley questions’) to aid identification of depression and other mental illnesses during pregnancy and the early postnatal period.13 Several previous studies have highlighted barriers to implementing these assessments in practice, such as time constraints and lack of training and knowledge about perinatal mental health.18 The present study suggests that the implementation of routine questions to identify mental illness may be more complex within the current healthcare system. For example, lack of ongoing assessment of women’s mental health throughout the perinatal period reduced the ability to identify significant changes in symptom presentation. Furthermore, challenges in interpreting responses to the questions arose from a lack of continuity of care and unclear thresholds and pathways of referral, which created uncertainty among healthcare professionals about the appropriate treatment response.

Under-resourced mental health service provision further contributed to women not being assessed by a specialist within an adequate time frame. A shortage of services for moderate mental illness led to primary care staff monitoring and managing the care of women they perceived to require greater support, creating confusion about referral thresholds. Lack of perinatal mental health services in the UK is well documented,19 and recent government investments aim to increase access by 30 000 women by 2021.20 However, in addition to a lack of specialist services, HCP emphasised several other barriers, which included both healthcare level factors (eg, a reluctance to prescribe medication or admit women to mental health hospitals during pregnancy or early post-birth) and patient-level and family-level factors (eg, stigma and missed appointments).

This is the first study to explore maternal near misses or life-threatening situations among women with perinatal mental illnesses. Interviews with a range of professionals involved in women’s antenatal and postnatal care allowed us to compare the views of different HCP and the impact that this had on recognition and response. Although several previous studies have explored experiences of care among women with perinatal mental illness,21–23 none have distinguished between women with high-risk mental illness, requiring rapid assessment and escalation and those with mild to moderate mental illness. This is important since differing levels of risk and severity require different communication strategies and treatment response. Failure to objectively differentiate between levels of risk and severity in mental health literature is likely to further compound the challenges highlighted in this study.

However, there are some study limitations that require consideration. This is a small qualitative study of HCP in the UK, which may not be generalisable to other settings. Importantly, women’s perspectives are not explored within this study. Given the sensitive nature of the topic, future research should be codesigned with women, and families, with experience of mental illness to adopt appropriate and sensitive research methods.

Furthermore, the utility and applicability of the concept of clinical deterioration and access to timely care, as proposed by the ‘three delay model’ of maternal mortality, requires further consideration within the context of psychiatric near miss events, since not all psychiatric maternal near misses will occur within the context of clinical deterioration. As highlighted by several HCP, an absence of reliable and dynamic methods of risk assessment impeded their ability to predict those at most risk of a life-threatening event. This is supported by a recent meta-analysis of risk scales, which demonstrated the predictive power of such scales on future suicidal behaviours was too low to advocate their use.24 Instead, a focus on individual needs-based assessments and modifiable risk factors is recommended.24 25

In conclusion, response and escalation of care for life threatening near miss events among women with mental illness is strongly influenced by professional culture and understandings of mental illness embedded within different healthcare disciplines. A lack of consensus about what constitutes a psychiatric maternal near miss resulted in discrepancies in reporting, recording and learning from such events. There are several clinical implications arising from this study, which emphasise the need for greater implementation of recommendations made by MBRRACE and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence2 13 (see box 1).

Box 1. Key implications for practice.

Based on the findings of this study, and existing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance and recommendations from the UK maternal deaths enquiry,2 15 the following recommendations aim to improve the detection and response to life-threatening situations among women with mental illness:

Clear referral thresholds and pathway – greater clarity and consensus, between all healthcare professionals involved in providing care for perinatal women, about the thresholds and pathways for referral to secondary mental health services during the perinatal period.

Transparent information sharing – Improved methods of information sharing between primary care, maternity, mental health teams and social services, which use a common language relating to mental health risk.

Ensure continuity of care when possible – greater implementation of continuity of care models for all healthcare professionals involved in a woman’s care during the perinatal period, which clearly state the roles, responsibilities and plans for dedicated care coordination.

Regular monitoring of women’s mental health – training and support for primary and maternity healthcare professionals around regular monitoring of mental health at all appointments (eg, when assessing physical health, mental health should also be assessed) to promote dynamic risk assessment and rapid response to deterioration.

To prevent future tragedies, there is a need for greater clarity and consensus about thresholds for referral to secondary mental health services and the role of Midwives and Health Visitors in monitoring women’s mental health during the perinatal period. Focusing on how differences in organisational and professional culture contribute to the recognition of severe mental illness and interdisciplinary communication may help facilitate clearer co-ordination between teams in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all healthcare professionals for dedicating their time to this study and the Section of Women’s Mental Health Perinatal Service User Advisory Group for their contribution to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AE, LH and JS conceived and designed the current study. AE was responsible for all data collection and primary data analysis; AE, LH and JS contributed to data interpretation. AE drafted the article which was critically revised by all authors. All authors approved the final version of the article to be published.

Funding: AE is funded through a King’s Improvement Science Fellowship award. King’s Improvement Science is part of the NIHR CLAHRC South London and comprises a specialist team of improvement scientists and senior researchers based at King’s College London. Its work is funded by King’s Health Partners (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust), Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity, the Maudsley Charity and the Health Foundation. Prof Howard is funded through a NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R3-12-011) in Maternal Mental Health. Prof Sandall CBE is an NIHR Senior Investigator. AE and JS are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was reviewed and approved by King’s College London Ethics Committee (Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee); Research Ethics Committee Reference LRS-16/17-3861 approval granted 12/12/16.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This is a qualitative study and therefore the data generated is not suitable for sharing beyond that contained within the report. Further information can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, et al. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet 2014;384:1775–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knight M, Bunch K, Tuffnell D, et al. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care - lessons learned to inform maternity are from the UK and Ireland confidential enquiries into maternal deaths and morbidity 2014-16. Oxford: University of Oxford, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications: the WHO near-miss approach for maternal health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tunçalp O, Hindin MJ, Souza JP, et al. The prevalence of maternal near miss: a systematic review. BJOG 2012;119:653–61. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03294.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Patterns of maternity care in English NHS hospitals 2011/12: RCOG Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nair M, Kurinczuk JJ, Knight M. Establishing a national maternal morbidity outcome indicator in england: a population-based study using Routine Hospital Data. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153370 10.1371/journal.pone.0153370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Easter A, Howard LM, Sandall J. Mental health near miss indicators in maternity care: a missed opportunity? A commentary. BJOG 2018;125 10.1111/1471-0528.14805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fanjiang G, Grossman JH, Compton WD, et al. Building a better delivery system: a new engineering/health care partnership: National Academies Press, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med 1994;38:1091–110. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:34 10.1186/1471-2393-9-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28:3–12. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Howard LM, Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, et al. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ 2014;349:g7394 10.1136/bmj.g7394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 2003;67:219–29. 10.1093/bmb/ldg011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Knight MNM, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2012-14 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009-14. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford 2016, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P, et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009-2012. 2014.

- 17. Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, et al. Improving Mothers’ Care Lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2013-2015. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Littlewood E, Ali S, Dyson L, et al. Identifying perinatal depression with case-finding instruments: a mixed-methods study (BaBY PaNDA – Born and Bred in Yorkshire PeriNatal Depression Diagnostic Accuracy). Health Services and Delivery Research 2018;6:1–210. 10.3310/hsdr06060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bauer A, Parsonage M, Knapp M, et al. Costs of perinatal mental health problems. 2014.

- 20. NHS England. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/perinatal/.

- 21. Button S, Thornton A, Lee S, et al. Seeking help for perinatal psychological distress: a meta-synthesis of women’s experiences. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e692–9. 10.3399/bjgp17X692549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Megnin-Viggars O, Symington I, Howard LM, et al. Experience of care for mental health problems in the antenatal or postnatal period for women in the UK: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Arch Womens Ment Health 2015;18:745–59. 10.1007/s00737-015-0548-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth 2006;33:323–31. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00130.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Carter G, Milner A, McGill K, et al. Predicting suicidal behaviours using clinical instruments: systematic review and meta-analysis of positive predictive values for risk scales. Br J Psychiatry 2017;210:387–95. 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.182717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Guidelines Self-Harm: Longer Term Management (CG 133). NICE, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.