Abstract

Background

Chronic pain is typically described as pain on most days for at least three months. Chronic non‐cancer pain (CNCP) is any chronic pain that is not due to a malignancy. Chronic non‐cancer pain in adults is a common and complex clinical issue where opioids are routinely used for pain management. There are concerns that the use of high doses of opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain lacks evidence of effectiveness and may increase the risk of adverse events.

Objectives

To describe the evidence from Cochrane Reviews and Overviews regarding the efficacy and safety of high‐dose opioids (here defined as 200 mg morphine equivalent or more per day) for chronic non‐cancer pain.

Methods

We identified Cochrane Reviews and Overviews through a search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (The Cochrane Library). The date of the last search was 18 April 2017. Two review authors independently assessed the search results. We planned to analyse data on any opioid agent used at high dose for two weeks or more for the treatment of chronic non‐cancer pain in adults.

Main results

We did not identify any reviews or overviews meeting the inclusion criteria. The excluded reviews largely reflected low doses or titrated doses where all doses were analysed as a single group; no data for high dose only could be extracted.

Authors' conclusions

There is a critical lack of high‐quality evidence regarding how well high‐dose opioids work for the management of chronic non‐cancer pain in adults, and regarding the presence and severity of adverse events. No evidence‐based argument can be made on the use of high‐dose opioids, i.e. 200 mg morphine equivalent or more daily, in clinical practice. Trials typically used doses below our cut‐off; we need to know the efficacy and harm of higher doses, which are often used in clinical practice.

Plain language summary

High doses of opioid drugs for the management of chronic non‐cancer pain

Bottom line

There is no high‐quality evidence to show how well high doses of opioids work, or what side effects there are, when these medications are used for the treatment of chronic pain that is not due to cancer in adults. Trials typically used doses below our cut‐off; we need to know how well high‐dose opioid medication works in this situation, and what side effects there may be.

Background

Opioids are a type of pain medication related to morphine. This overview aimed to summarise the knowledge in Cochrane Reviews and Overviews about opioid drugs. We were interested in opioid medications used at high doses (equivalent to 200 mg of morphine per day or more) for pain relief in adults who have chronic pain not due to cancer. We wanted to describe how well high‐dose opioid medications work in this situation, and what side effects there might be.

Key results

Despite a systematic search in April 2017, we did not find any information about this. Studies on opioids rarely reported on high‐dose use and, if so, they did not report separate information for participants who used high‐dose opioids.

Background

Description of the condition

Pain is described as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (Merskey 1994). Chronic pain is typically described as pain on most days for at least three months. Chronic non‐cancer pain (CNCP) is any chronic pain that is not due to a malignancy. CNCP is frequently divided into neuropathic pain, i.e. pain originating in nerves, on the one hand; and non‐neuropathic or nociceptive pain, which is often musculoskeletal in origin and arises for example in muscles, bones, or ligaments.

CNCP is reported to be very common in adults. A recent review estimated the prevalence of CNCP (of moderate or severe intensity, lasting more than three months) at about 20% of adults, with considerable variation between different studies (Moore 2014). The impact of CNCP on various domains of life is substantial, impacting quality of life and affecting activities of daily living, social life, and work — about 20% of chronic pain sufferers are unable to work (Moore 2014).

The personal and subjective nature of pain makes objective measurement impossible; an assessment of pain is subjective and based on individual report (Breivik 2008). A number of self‐report instruments to measure pain and to determine its impact on the physical, social, emotional, and spiritual aspects of life are used.

Description of the interventions

The treatment of pain may encompass a variety of approaches, including pharmacological management. Effective pain therapy has been described as a reduction in pain intensity of at least 50% over baseline, or sometimes as a reduction of at least 30% over baseline, as well as improvement in work‐ and function‐related outcomes. Effective pain therapy results in consistent improvements in fatigue, sleep, depression, quality of life, and work (Moore 2014). Opioid therapy is used for the treatment of both acute and chronic painful conditions. There are large numbers of policies and guidelines to assist with the prescription of opioids for the management of chronic pain. The World Health Organization's (WHO) analgesic ladder guides the use of pain medications (including opioids and non‐opioids such as non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)) in the management of pain (WHO 1996). Although originally formulated for cancer pain, this tool is now utilised for a broad range of chronic pain conditions. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine concludes that quality evidence does not support a superiority of opioids over NSAIDs or other medications for the treatment of CNCP (Hegmann 2014b). This overview addresses the use of high‐dose opioids. As discussed below, we take this to mean opioids at doses of 200 mg morphine equivalent per day or more.

How the intervention might work

Opium is a plant‐derived substance, with the primary ingredients morphine and codeine. The term 'opioids' refers to either naturally occurring compounds (opiates) or synthetic compounds. As centrally acting analgesics, opioids bring about their action in the human body by binding to opioid receptors. The mu, kappa, and delta opioid receptors are widely distributed throughout the nervous system (Rachinger‐Adam 2011). Key among the opioid effects is analgesia, and the focus of this overview is the use of opioids for their analgesic effect. Opioids bring about complex changes at the cellular and molecular level, decreasing pain perception and increasing tolerance to painful stimuli (Rass 2014).

A number of opioid actions other than analgesia have been described. These include euphoria (Schulteis 1996), sedation and drowsiness, and endocrine dysregulation (Vuong 2010). Opioids furthermore alter sleep regulation, and are associated with poor sleep quality, insomnia, respiratory depression, sleep apnoea and sleep‐disordered breathing (Zutler 2011). Physiological dependence on opioids may develop rapidly after the initiation of opioid use, and opioid abuse and dependence (opioid use disorders) are a major concern with this group of medications. Opioid addiction is also a significant problem, and its neurobiology suggests that increasing doses of opioids are desired over time (Kosten 2002).

Due to the effects of opioids on cognitive function, their use is commonly viewed as incompatible with safety‐sensitive work (Hegmann 2014a).

Although a number of adverse effects have been identified with the acute administration of opioids, or in novice users, chronic opioid use has been suggested to result in fewer medical problems (Rass 2014). Some of these adverse effects are, however, serious and potentially lethal and they may not decrease with long‐term use.

Why it is important to do this overview

Opioids are now commonly and increasingly used, and used at higher doses, for the treatment of pain, including chronic pain that is not due to cancer (Zutler 2011). The opioid doses used in the CNCP situation vary between practitioners, payers, and countries. There has been a large increase in the use of opioids for CNCP in recent years despite safety concerns and despite a lack of clear‐cut evidence of effectiveness (Kidner 2009; Chapman 2010; Bohnert 2012). Further evidence of larger doses of opioids now being utilised for the treatment of CNCP is emerging. For example, a recent analysis of Workers' Compensation Board (WCB) data (where most claimants with pain would have non‐malignant pain) from Manitoba, Canada has demonstrated a dramatic increase in the average opioid dose prescribed over time — from less than 500 mg morphine equivalent per year in 1998 to over 6000 mg morphine equivalent per year in 2010. Moreover, compared to other Manitobans, the WCB claimant population was about twice as likely to be prescribed doses above 120 mg morphine equivalent per day (Kraut 2015). Opioid use has been demonstrated to often continue post‐claim; both duration of post‐claim opioid use and post‐claim dose positively correlate with the opioid dose during the claim, as demonstrated by another analysis of WCB Manitoba data (Shafer 2015). The rate of dispensing high‐dose opioids at doses of 200 mg morphine equivalent daily or greater increased in Canada by 23% between 2006 and 2011 (Gomes 2014). Similar increases are now commonly seen in other parts of the world, including the USA and, as recently documented, in the UK (Zin 2014).

The use of high‐dose opioids for CNCP has recently come under review because of questions as to the effectiveness of opioids in this circumstance as well as the potential for adverse events, abuse and addiction (Canadian guideline 2010; Franklin 2014; Häuser 2014; Nuckols 2014; Katz 2015). Three decades ago Portenoy and Foley described an addiction risk of lower than 1% (Portenoy 1986). However, recent evidence suggests that opioid abuse and addiction are well documented and not uncommon among people with chronic pain, with rates of addiction averaging between 8% and 12% (Vowles 2015). There is a potential for opioid addiction to develop even if these drugs are used for the management of severe pain (Kosten 2002; Huffman 2015; Vowles 2015).

With increasing opioid doses the risk for addiction increases. Recently, Huffman and colleagues reported that 50 mg increases in oral morphine dose almost doubled the risk of addiction; a 100 mg increase in dose was associated with a three‐fold increase in risk (Huffman 2015). Furthermore, there is the potential for severe adverse events, such as sleep apnoea, sleep‐disordered breathing and respiratory depression that may lead to opioid‐associated deaths; such adverse outcomes of opioid use demonstrate a clear dose dependency (Walker 2007; Jungquist 2012).

Hegmann and colleagues summarise the substantial increase in the use of opioids, along with the increase in deaths associated with opioid use (Hegmann 2014b). Opioid‐related deaths are common and can occur even when the prescription is in accordance with guidelines. Most opioid‐related deaths in the US (60%) have occurred in people given prescriptions based on prescribing guidelines by medical boards (with 20% of deaths for doses of at most 100 mg morphine equivalent per day, and 40% in people prescribed dosages above that threshold). The remaining 40% of deaths have occurred in people abusing the drugs (Manchikanti 2012a). Abuse of opioids includes multiple prescriptions, double‐doctoring, and drug diversion.

A consensus is emerging that while long‐term opioid therapy for non‐cancer pain may be appropriate for selected individuals, it should not be the rule (Manchikanti 2012b). Further, a strong and reproducible dose‐response relationship for efficacy led to the recommendation for a morphine equivalent dose limit of 50 mg per day; higher doses are only recommended with documented functional improvement, risk‐benefit consideration, and monitoring of adverse events (Hegmann 2014b). Guidelines and research articles vary in what they consider to be a high opioid dose. A previous Canadian guideline designated a dose of opioids in excess of 200 mg morphine equivalent per day as a "watchful dose" (Canadian guideline 2010); of note, since we started the present overview project, this guideline has now been updated and the current Canadian guideline makes reference to recommended dose limits of 90 mg and 50 mg morphine equivalent per day (Busse 2017). This current Canadian guideline is therefore more aligned with the dose recommendations captured in the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) guideline (Hegmann 2014b), as well as the CDC guideline (Dowell 2016). Other recent guidelines recommend maximum doses in the order of 100 or 120 mg morphine equivalent per day. For example, a current German guideline based on a systematic review recommends that the morphine equivalent dose should not exceed 120 mg per day (Häuser 2014). A dose of 200 mg morphine equivalent per day (as per the previous Canadian watchful dose) has been adopted as the 'high‐dose' threshold for this overview.

Another Cochrane overview complements this present overview; this other overview is titled "Adverse events associated with medium‐ and long‐term use of opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane Reviews" (Els 2017).

Objectives

To describe the evidence from Cochrane Reviews and Overviews regarding the efficacy and safety of high‐dose opioids (here defined as 200 mg morphine equivalent or more per day) for chronic non‐cancer pain.

Methods

We aimed to provide an overview of the evidence from Cochrane Reviews and Overviews for the efficacy and safety of any opioid agent used at high dose, administered by any route and frequency of administration, for the treatment of chronic non‐cancer pain in adults. Typically, we would expect trial durations of at least two weeks to be relevant for a chronic painful condition. Reviews including shorter trials would have been critically assessed. If a review included a majority of data from inappropriately short trials, this might have led to exclusion of the review from the overview, depending on the condition studied.

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

We had planned to include all Cochrane Reviews and Overviews of randomised controlled trials that assessed the efficacy and safety of opioids in adults with any chronic non‐cancer pain.

We would have expected the following of a Cochrane Review or Overview in order to be included in our overview.

There is a clearly defined research question relevant to the use of opioids in chronic non‐cancer pain.

The Cochrane Review or Overview performs a systematic search for relevant evidence providing details of databases searched and the search strategies.

The Review or Overview details criteria for the inclusion of studies. Included studies in Cochrane Reviews will typically be randomised controlled trials, as this study design is associated with a lower risk of bias than non‐randomised study designs.

Outcomes of interest and data on the high‐dose range (200 mg morphine equivalent or more per day) are reported.

Outcomes of interest

With regard to choosing outcome measures to assess the efficacy and safety of interventions in our overview, we would have preferred those outcome measures that are of known utility. Our preferred outcome measures were based on guidance for systematic reviews in the pain field (Moore 2010). We had planned to consider group average values if no or insufficient data for responder analyses had been uncovered. Our outcomes of interest are listed below; we planned to extract and analyse data for opioid doses of 200 mg morphine equivalent or more per day.

Pain‐related outcomes

Proportion of participants with at least 50% pain reduction over study baseline.

Proportion of participants with at least 30% pain reduction over study baseline.

Proportion of participants below 30/100 mm on the visual analogue pain scale (no worse than mild pain).

Treatment group average scores for pain intensity or pain relief.

Work‐ and function‐related outcomes

Work time missed.

Interference with work (subjective rating scales).

Function (SF‐36, SF‐12 scales); proportion of participants with at least 30% improvement in functional abilities.

Quality of life (any scale).

Adverse event outcomes

Proportion of participants with any adverse event.

Proportion of participants with any serious adverse event.

Proportion of participants withdrawing due to adverse events.

We planned to note the imputation methods used in the trials and discuss the limitations resulting out of the imputation methods used. We would have preferred data with a 'baseline observation carried forward' methodology over data with last observation carried forward, if there was a choice.

Search methods for identification of reviews

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,(in the Cochrane Library), Issue 4, 2017, across all years. The date of the last search was 18 April 2017. The search strategy is presented in Appendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of reviews

Two of three review authors (CE, TJ, BS) independently screened the results of the electronic search by title and abstract. We obtained the full‐text versions of potentially relevant reviews and overviews, and two of three review authors (CE, TJ, BS) subsequently applied the selection criteria to determine eligibility for inclusion. We would have resolved disagreements by discussion.

Data extraction and management

We planned to have two review authors independently extract data using a standardised form. We planned to resolve discrepancies by consensus and to consult a third review author and make a majority decision should we not have achieved resolution.

Using standardised and piloted data extraction forms, we planned to extract data on the following.

Objectives of the Cochrane Review or Overview.

Number of studies and participants included in the Cochrane Review or Overview.

Study and participant baseline characteristics.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in the Cochrane Review or Overview.

Chronic pain conditions studied.

Opioid medication, dose and frequency of administration.

Our outcomes of interest.

Route of administration covered in the Review or Overview.

Declarations of competing interest and sponsorship of the Cochrane Review or Overview authors.

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

Two authors intended to undertake a formal quality assessment of the Cochrane Reviews and Overviews included in our overview using criteria modified from the AMSTAR guidance (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews; Shea 2007) for the quality assessment of the Cochrane Reviews to be included in an overview (Moore 2015). They would have worked independently and reconciled differences through discussion or, if needed, by consulting a third author.

Data synthesis

Our primary aim, given the expected methodological and clinical heterogeneity between the Cochrane Reviews and Overviews that we would include in our overview, was to perform a qualitative evidence synthesis. If feasible and appropriate, however, we would have conducted quantitative meta‐analyses. For meta‐analysis, we intended to use a fixed‐effect model or alternatively a random‐effects model as determined by between‐study heterogeneity (I² statistic). In addition to assessing statistical heterogeneity, we planned to also consider clinical heterogeneity between the studies. We would have used a fixed‐effect model when there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity of either kind. We would have calculated relative benefit or risk with 95% confidence intervals. We would have calculated numbers needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome or an additional harmful outcome from the pooled number of events using the method of Cook and Sackett (Cook 1995). The methodology for our overview and for meta‐analyses was to follow the guidance detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to perform our analyses across opioid agents (by conversion to mg morphine equivalent) and also for the individual agents. We planned to conduct separate analyses by trial duration. Short‐term treatment was to be taken to mean treatment less than two weeks in duration. Medium term was to be at least two weeks and up to two months. Long‐term was to be two months or greater.

We would have assessed the quality of the body of evidence with the GRADE approach as applied in Cochrane Reviews (Higgins 2011). See Appendix 2 for a further description of the GRADE system.

Results

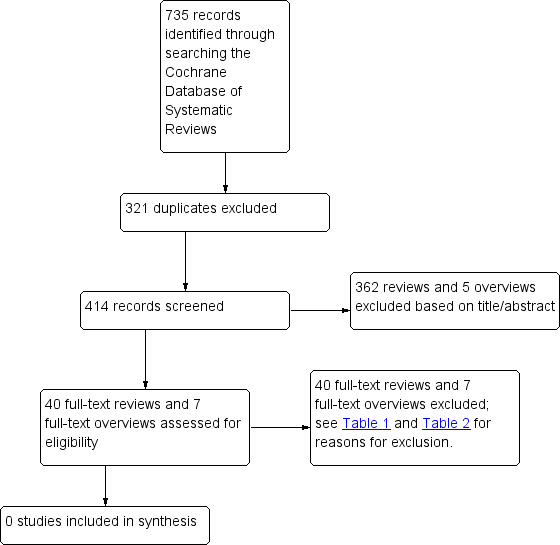

Our study selection is illustrated by the flow diagram in Figure 1.

1.

Review/Overview selection process

We searched the Cochrane Library using a combination of controlled vocabulary (MeSH) and text terms (Appendix 1). The search resulted in 735 records, including 723 Cochrane Reviews and 12 Cochrane Overviews. Three hundred and twenty one of the Cochrane Reviews were duplicates, resulting in 414 records (402 reviews and 12 overviews). We excluded 362 reviews and five overviews based on the title or abstract, leaving 40 reviews and seven overviews for detailed examination. We retrieved all 40 full‐text reviews and the seven overviews. None met the inclusion criteria for our overview. This was primarily due to three reasons. Some reviews focused on cancer or acute pain. Others did not include opioids as an intervention. Furthermore, reviews that did include opioids for CNCP studied a range of opioid doses, with all doses, including those below and above our cut‐off of 200 mg morphine equivalent per day, being analysed together as a single group without separate data for high‐dose use being provided. The reasons for exclusion are detailed in Table 1 for reviews and Table 2 for overviews.

1. Characteristics of excluded reviews.

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

| Alviar 2011 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Bao 2016 | Cancer pain |

| Bell 2012 | Cancer pain |

| Brettschneider 2013 | No opioids studied |

| Cepeda 2006 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Chaparro 2012 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Chaparro 2013 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Cheong 2014 | No opioids studied |

| de Oliveira 2016 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Duehmke 2006 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Enthoven 2016 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Fraquelli 2016 | Acute pain |

| Gaskell 2014 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Gaskell 2016 | Empty review |

| Hadley 2013 | Cancer pain |

| Hróbjartsson 2010 | No opioids studied |

| Marks 2011 | No opioids studied |

| McNicol 2013 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| McNicol 2015 | Withdrawn from publication |

| Moore 2015 | No opioids studied |

| Mujakperuo 2010 | No opioids studied |

| Nicholson 2017 | Cancer pain |

| Quigley 2013 | Withdrawn from publication |

| Radner 2012 | No opioids studied |

| Ramiro 2011 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Richards 2011 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Santos 2015 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Schmidt‐Hansen 2015a | Cancer pain |

| Schmidt‐Hansen 2015b | Cancer pain |

| Seidel 2013 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Singh 2015 | No opioids studied |

| Staal 2008 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Stannard 2016 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Stanton 2013 | No opioids studied |

| Straube 2014 | Cancer pain |

| Whittle 2011 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Wiffen 2015a | Opioids studied but with mixed cancer and non‐cancer group |

| Wiffen 2015b | Cancer pain |

| Wiffen 2016 | Cancer pain |

| Zeppetella 2015 | Cancer pain |

2. Characteristics of excluded overviews.

| Overview | Reason for exclusion |

| da Costa 2014 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Derry 2016 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Haroutiunian 2012 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| Moore 2015 | No opioids studied |

| Noble 2010 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

| O'Connell 2013 | No opioids studied |

| Rubinstein 2011 | Opioids studied but not at high doses specifically |

We also assessed whether component studies in the reviews might have described high‐dose opioid use; from five of the reviews — Chaparro 2012, Chaparro 2013, McNicol 2013, Santos 2015, Wiffen 2015a — we therefore obtained full‐text copies of 27 potentially relevant component studies that had been included in these reviews. None of these studies had separate data on high‐dose use, except for one review (Wiffen 2015a). This included a relevant study where all participants received high doses of opioids, but both cancer and non‐cancer patients were included and the data for non‐cancer pain were not analysed separately (Bohme 2003).

The overviews identified by our search for detailed examination included opioids as possible interventions, but ultimately none of these overviews could be included in the present overview. Table 2 details the reasons for exclusion.

Description of included reviews

No Cochrane Reviews or Overviews met our inclusion criteria.

Effect of interventions

No Cochrane Reviews or Overviews were identified that met our inclusion criteria.

Discussion

Summary of main results

No Cochrane Reviews or Overviews were included in this overview.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There is a lack of high‐quality evidence on the efficacy and safety of high‐dose opioids for the management of CNCP in adults. No evidence‐based statements can be made on the use of high‐dose opioids in clinical practice.

Quality of the evidence

Our overview aimed to assess all of the available evidence from Cochrane Reviews and Overviews on the use of high‐dose opioids in the management of CNCP in adults. No such evidence was found.

Potential biases in the overview process

We know of no potential biases in the overview process. It is unlikely that there exists a substantial body of high‐quality evidence examining how well high‐dose opioids work for CNCP, or what adverse effects they may have.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This overview is consistent with other reviews — Hegmann 2014b and Dowell 2016 — in that there appears to be no body of dependable, high‐quality clinical evidence to support or refute the use of high‐dose opioids for CNCP.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

For persons suffering from chronic non‐cancer pain

There is an absence of high‐quality evidence to support the use of high‐dose opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain. Opioids are associated with increased risks for adverse events, including addiction, overdose, and death (Dowell 2016). When selecting a treatment modality and dosage, risks and benefits have to be considered. Patients should be made aware of the potential risks and the absence of evidence for benefit of high‐dose opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain. Physicians should have frank and open conversations with patients in this regard, supplemented with a discussion on alternative strategies.

For policy makers

There is insufficient evidence to either support or refute the efficacy of high‐dose opioids in chronic non‐cancer pain. In view of the established risks, including addiction, overdose and death, policy makers should consider not supporting the use of high‐dose opioids for treating chronic non‐cancer pain.

For funders

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of high‐dose opioids for the treatment of chronic non‐cancer pain. In the absence of such evidence, it should not be recommended.

Implications for research.

General

Although we know that opioids are more commonly prescribed to patients, and at higher doses, for the treatment of chronic non‐cancer pain than heretofore, there is no evidence to refute or support the efficacy of this clinical practice. The risks associated with high‐dose opioid use are, however, well established. We do not at present have dependable information about how well high‐dose opioids work or what adverse effects may accompany their use when they are used on a long‐term basis for chronic non‐cancer pain.

Design

On the one hand, the absence of high‐quality evidence for high‐dose opioid use would typically call for more randomised controlled trials to be conducted, specifically addressing this question. On the other hand, the potential for significant adverse events with high‐dose opioids provides an argument against conducting these studies. The ethics of conducting studies on high‐dose opioids would need to be considered carefully.

Where possible, data from patients receiving high‐dose opioids in existing datasets should be re‐analysed separately.

Measurement

Many of the outcomes of interest for high‐dose opioids are the same as for opioids studied at a lower dose range. Dworkin 2005 outlined six domains that should be considered for chronic pain clinical trials, including pain, physical functioning, emotional functioning, treatment satisfaction, symptoms and adverse events, and participant disposition.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 January 2018 | Amended | Minor amendment to Declarations of interest section. |

Acknowledgements

Cochrane Review Group funding acknowledgement: this project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Review Group (PaPaS). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (in the Cochrane Library) search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Pain] explode all trees

#2 pain*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#3 #1 or #2

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Analgesics, Opioid] explode all trees

#5 opioid*:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#6 codeine or oxycodone or tramadol or hydromorphone or morphine or fentanyl:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#7 meperidine or pethidine or dextropropoxyphene or methadone or buprenorphine or pentazocine or hydrocodone or opium or butorphanol:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#8 tapentadolol or papaveretum or meptazinol or dipipanone or dihydrocodeine or diamorphine:ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#9 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8

#10 #3 and #9

Appendix 2. GRADE Assessment

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grade of evidence.

High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Grade of evidence is decreased further if the following are present.

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality.

Important inconsistency (‐1).

Some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness.

Imprecise or sparse data (‐1).

High probability of reporting bias (‐1).

Contributions of authors

SS conceived of the idea. CE, RH, DK, BS, VL, and SS contributed to the protocol for this overview. TJ joined the project after the protocol was published. TJ did the searching with the help of the PaPaS Review group. CE, TJ, and BS screened the abstracts. CE, TJ, and BS assessed Cochrane Reviews and Overviews for inclusion, with guidance from SS. CE, TJ, and SS drafted the full overview. All overview authors approve the final version of the overview.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

WCB Alberta, Canada.

We acknowledge funding from the Workers’ Compensation Board of Alberta (Edmonton, Alberta) for the project “Effectiveness and safety of high dose opioid therapy in WCB Alberta claimants”, of which this overview is part.

-

Alberta School of Business, Canada.

We acknowledge funding from the Alberta School of Business, University of Alberta, for the project “Effectiveness and safety of high dose opioid therapy in WCB Alberta claimants”, of which this overview is part.

Declarations of interest

Charl Els: none known.

Tanya Jackson: none known; Tanya Jackson is a clinical psychologist whose practice includes patients with chronic pain.

Reidar Hagtvedt: none known.

Diane Kunyk: none known.

Barend Sonnenberg: none known.

Vernon G Lappi: none known; Vernon G Lappi is a specialist occupational medicine physician. His past practice has included patients with chronic pain.

Sebastian Straube's institution (University of Alberta) received fees for his contribution to an advisory board from Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. (2015). Sebastian Straube is a specialist occupational medicine physician and some of the patients he assesses have chronic pain.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to excluded reviews

Alviar 2011

- Alviar MJM, Hale T, Dungca M. Pharmacologic interventions for treating phantom limb pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 12. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006380.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bao 2016

- Bao YJ, Hou W, Kong XY, Yang L, Xia J, Hua BJ, et al. Hydromorphone for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011108.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bell 2012

- Bell RF, Eccleston C, Kalso EA. Ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003351.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brettschneider 2013

- Brettschneider J, Kurent J, Ludolph A. Drug therapy for pain in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005226.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cepeda 2006

- Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005522.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaparro 2012

- Chaparro LE, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA, Gilron I. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008943.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chaparro 2013

- Chaparro LE, Furlan AD, Deshpande A, Mailis‐Gagnon A, Atlas S, Turk DC. Opioids compared to placebo or other treatments for chronic low‐back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004959.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cheong 2014

- Cheong YC, Smotra G, Williams ACC. Non‐surgical interventions for the management of chronic pelvic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008797.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

da Costa 2014

- Costa BR, Nüesch E, Kasteler R, Husni E, Welch V, Rutjes AWS, et al. Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de Oliveira 2016

- Oliveira CO, Carvalho LB, Carlos K, Conti C, Oliveira MM, Prado LB, et al. Opioids for restless legs syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006941.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Derry 2016

- Derry S, Stannard C, Cole P, Wiffen PJ, Knaggs R, Aldington D, et al. Fentanyl for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011605.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Duehmke 2006

- Duehmke RM, Hollingshead J, Cornblath DR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003726.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Enthoven 2016

- Enthoven W, Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Tulder MW, Koes BW. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012087] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fraquelli 2016

- Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Conte D, Colli A. Non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs for biliary colic. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006390.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gaskell 2014

- Gaskell H, Moore RA, Derry S, Stannard C. Oxycodone for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010692.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gaskell 2016

- Gaskell H, Moore RA, Derry S, Stannard C. Oxycodone for pain in fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012329] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hadley 2013

- Hadley G, Derry S, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ. Transdermal fentanyl for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010270.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haroutiunian 2012

- Haroutiunian S, McNicol ED, Lipman AG. Methadone for chronic non‐cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008025.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hróbjartsson 2010

- Hróbjartsson A, Gøtzsche PC. Placebo interventions for all clinical conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003974.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marks 2011

- Marks JL, Colebatch AN, Buchbinder R, Edwards CJ. Pain management for rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular or renal comorbidity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008952.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McNicol 2013

- McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E. Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McNicol 2015

- McNicol ED, Strassels S, Goudas L, Lau J, Carr DB. NSAIDS or paracetamol, alone or combined with opioids, for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005180.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2015a

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011824] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2015b

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Wiffen PJ. Amitriptyline for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 7. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008242.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mujakperuo 2010

- Mujakperuo HR, Watson M, Morrison R, Macfarlane TV. Pharmacological interventions for pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004715.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nicholson 2017

- Nicholson AB, Watson GR, Derry S, Wiffen PJ. Methadone for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003971.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Noble 2010

- Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, Coates VH, Wiffen PJ, Akafomo C, et al. Long‐term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006605.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Connell 2013

- O'Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, Marston L, Moseley GL. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome‐ an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009416.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quigley 2013

- Quigley C. Hydromorphone for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003447.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Radner 2012

- Radner H, Ramiro S, Buchbinder R, Landewé R, Heijde D, Aletaha D. Pain management for inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthritis) and gastrointestinal or liver comorbidity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008951.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramiro 2011

- Ramiro S, Radner H, Heijde D, Tubergen A, Buchbinder R, Aletaha D, et al. Combination therapy for pain management in inflammatory arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, other spondyloarthritis). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008886.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Richards 2011

- Richards BL, Whittle SL, Buchbinder R. Antidepressants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008920.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rubinstein 2011

- Rubinstein SM, Middelkoop M, Assendelft WJJ, Boer MR, Tulder MW. Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low‐back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008112.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Santos 2015

- Santos J, Alarcão J, Fareleira F, Vaz‐Carneiro A, Costa J. Tapentadol for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009923.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmidt‐Hansen 2015a

- Schmidt‐Hansen M, Bennett MI, Arnold S, Bromham N, Hilgart JS. Oxycodone for cancer‐related pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003870.pub5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schmidt‐Hansen 2015b

- Schmidt‐Hansen M, Bromham N, Taubert M, Arnold S, Hilgart JS. Buprenorphine for treating cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009596.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Seidel 2013

- Seidel S, Aigner M, Ossege M, Pernicka E, Wildner B, Sycha T. Antipsychotics for acute and chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004844.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Singh 2015

- Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, Maxwell LJ. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD005614.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Staal 2008

- Staal JB, Bie R, Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low‐back pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001824.pub3] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stannard 2016

- Stannard C, Gaskell H, Derry S, Aldington D, Cole P, Cooper TE, et al. Hydromorphone for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 5. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011604.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stanton 2013

- Stanton TR, Wand BM, Carr DB, Birklein F, Wasner GL, O'Connell NE. Local anaesthetic sympathetic blockade for complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004598.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Straube 2014

- Straube C, Derry S, Jackson KC, Wiffen PJ, Bell RF, Strassels S, et al. Codeine, alone and with paracetamol (acetaminophen), for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD006601.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Whittle 2011

- Whittle SL, Richards BL, Husni E, Buchbinder R. Opioid therapy for treating rheumatoid arthritis pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 11. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003113.pub3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiffen 2015a

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Moore RA, Stannard C, Aldington D, Cole P, et al. Buprenorphine for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011603.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiffen 2015b

- Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Naessens K, Bell RF. Oral tapentadol for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011460.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wiffen 2016

- Wiffen PJ, Wee B, Moore RA. Oral morphine for cancer pain. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003868.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zeppetella 2015

- Zeppetella G, Davies AN. Opioids for the management of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004311.pub4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bohme 2003

- Bohme K, Likar R. Efficacy and tolerability of a new opioid analgesic formulation, buprenorphine transdermal therapeutic system (TDS), in the treatment of patients with chronic pain. A randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Pain Clinic 2003;15(2):193‐202. [DOI: 10.1163/156856903321579334] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Bohnert 2012

- Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Ignacio RV, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Blow FC. Risk of death from accidental overdose associated with psychiatric and substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 2012;169(1):64‐70. [DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10101476] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Breivik 2008

- Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, Rosseland LA, Romundstad L, Hals EB, et al. Assessment of pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2008;101(1):17‐24. [DOI: 10.1093/bja/aen103] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Busse 2017

- Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ 2017;189(18):E659‐66. [DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.170363] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Canadian guideline 2010

- National Opioid Use Guideline Group (NOUGG). Canadian guideline for safe and effective use of opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain. nationalpaincentre.mcmaster.ca/opioid/documents.html (accessed 12 May 2017).

Chapman 2010

- Chapman CR, Lipschitz DL, Angst MS, Chou R, Denisco RC, Donaldson GW, et al. Opioid pharmacotherapy for chronic non‐cancer pain in the United States: A research guideline for developing an evidence‐base. Journal of Pain 2010;11(9):807‐29. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1995

- Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ 1995;310(6977):452‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dowell 2016

- Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain ‐ United States, 2016. JAMA 2016;315(15):1624‐45. [DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.1464] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dworkin 2005

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2005;113:9‐19. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.019] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Els 2017

- Els C, Jackson TD, Kunyk D, Lappi VG, Sonnenberg B, Hagtvedt R, et al. Adverse events associated with medium‐ and long‐term use of opioids for chronic non‐cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012509] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franklin 2014

- Franklin GM, American Academy of Neurology. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: a position paper of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2014;83(14):1277‐84. [DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gomes 2014

- Gomes T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Dhalla IA, Juurlink DN. Trends in high‐dose opioid prescribing in Canada. Canadian Family Physician 2014;60(9):826‐32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hegmann 2014a

- Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, Branco F, DuBrueler K, Els C, et al. ACOEM practice guidelines: opioids and safety‐sensitive work. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2014;56(7):e46‐53. [DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000237] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hegmann 2014b

- Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, Branco F, DuBrueler K, Els C, et al. ACOEM practice guidelines Opioids for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, and postoperative pain. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2014;56(12):e143‐59. [DOI: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000352] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from handbook.cochrane.org.

Huffman 2015

- Huffman KL, Shella ER, Sweis G, Griffith SD, Scheman J, Covington EC. Nonopioid substance use disorders and opioid dose predict therapeutic opioid addiction. Journal of Pain 2015;16(2):126‐34. [DOI: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.10.011] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Häuser 2014

- Häuser W, Bock F, Engeser P, Tölle T, Willweber‐Strumpfe A, Petzke F. Clinical practice guideline: Long‐term opioid use in non‐cancer pain. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2014;111(43):732‐40. [DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0732] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jungquist 2012

- Jungquist CR, Flannery M, Perlis ML, Grace JT. Relationship of chronic pain and opioid use with respiratory disturbance during sleep. Pain Management Nursing 2012;13(2):70‐9. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pmn.2010.04.003] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Katz 2015

- Katz JA, Swerdloff MA, Brass SD, Argoff CE, Markman J, Backonja M, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology; Author Response. Neurology 2015;84(14):1503‐4. [DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001485] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kidner 2009

- Kidner CL, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ. Higher opioid doses predict poorer functional outcome in patients with chronic disabling occupational musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2009;91(4):919‐27. [DOI: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00286] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kosten 2002

- Kosten TR, George TP. The neurobiology of opioid dependence: implications for treatment. Science & Practice Perspectives 2002;1(1):13‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kraut 2015

- Kraut A, Shafer LA, Raymond CB. Proportion of opioid use due to compensated workers' compensation claims in Manitoba, Canada. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 2015;58(1):33‐9. [DOI: 10.1002/ajim.22374] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manchikanti 2012a

- Manchikanti L, Helm S 2nd, Fellows B, Janata JW, Pampati V, Grider JS, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES9‐38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Manchikanti 2012b

- Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, Balog CC, Benyamin RM, Boswell MV, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non‐cancer pain: Part 2‐‐guidance. Pain Physician 2012;15(3 Suppl):S67‐116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Merskey 1994

- Merskey H, Lindblom U, Mumford JM, Nathan PW, Sunderland S. Part III: Pain terms—a current list with definitions and notes on usage with definitions and notes on usage.. In: Merskey H, Bogduk N editor(s). Classification of Chronic Pain, IASP Task Force on Taxonomy. 2nd Edition. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994:209‐14. [Google Scholar]

Moore 2010

- Moore RA, Eccleston C, Derry S, Wiffen P, Bell RF, Straube S, et al. ACTINPAIN Writing Group of the IASP Special Interest Group on Systematic Reviews in Pain Relief, Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Systematic Review Group Editors. "Evidence" in chronic pain‐‐establishing best practice in the reporting of systematic reviews. Pain 2010;150(3):386‐9. [DOI: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.05.011] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2014

- Moore AR, Derry S, Taylor RS, Straube S, Phillips CJ. The costs and consequences of adequately managed chronic non‐cancer pain and chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Practice 2014;14(1):79‐94. [DOI: 10.1111/papr.12050] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2015

- Moore RA, Derry S, Aldington D, Wiffen PJ. Adverse events associated with single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative pain in adults ‐ an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011407.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nuckols 2014

- Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, Diamant AL, Doyle B, Capua P, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Annals of Internal Medicine 2014;160(1):38‐47. [DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Portenoy 1986

- Portenoy R, Foley K. Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non‐malignant pain: report of 38 cases. Pain 1986;25(2):171‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rachinger‐Adam 2011

- Rachinger‐Adam B, Conzen P, Azad SC. Pharmacology of peripheral opioid receptors. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2011;24(4):408‐13. [doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834873e5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rass 2014

- Rass O, Schacht RL, Marvel CL, Mintzer MZ. Opioids (Chapter 11). In: Allen DN, Woods SP editor(s). Neuropsychological aspects of substance use disorders: Evidence‐based perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014:231‐53. [Google Scholar]

Schulteis 1996

- Schulteis G, Koob GF. Reinforcement processes in opiate addiction: a homeostatic model. Neurochemical Research 1996;21(11):1437‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shafer 2015

- Shafer LA, Raymond C, Ekuma O, Kraut A. The impact of opioid prescription dose and duration during a workers compensation claim, on post‐claim continued opioid use: A retrospective population‐based study. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 2015;58(6):650‐7. [DOI: 10.1002/ajim.22453] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shea 2007

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2007;7:1‐10. [DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vowles 2015

- Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, Frohe T, Ney JP, Goes DN. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 2015;156(4):569‐76. [DOI: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vuong 2010

- Vuong C, Uum SH, O’Dell LE, Lutfy K, Friedman TC. The effects of opioids and opioid analogs on animal and human endocrine systems. Endocrine Reviews 2010;31(1):98–132. [DOI: 10.1210/er.2009-0009] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walker 2007

- Walker JM, Farney RJ, Rhondeau SM, Boyle KM, Valentine K, Cloward TV, et al. Chronic opioid use is a risk factor for the development of central sleep apnea and ataxic breathing. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2007;3(5):455‐61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 1996

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief: with a guide to opioid availability. 2nd Edition. Geneva: WHO, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Zin 2014

- Zin CS, Chen LC, Knaggs RD. Changes in trends and pattern of strong opioid prescribing in primary care. European Journal of Pain 2014;18(9):1343‐51. [DOI: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2014.496.x] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zutler 2011

- Zutler M, Holty JE. Opioids, sleep, and sleep‐disordered breathing. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2011;17(15):1443‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]