Abstract

Background

Cutaneous leishmaniasis, caused by a parasitic infection, is considered one of the most serious skin diseases in many low‐ and middle‐income countries. Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis (OWCL) is caused by species found in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and India. The most commonly prescribed treatments are antimonials, but other drugs have been used with varying success. As OWCL tends to heal spontaneously, it is necessary to justify the use of systemic and topical treatments. This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2008.

Objectives

To assess the effects of therapeutic interventions for the localised form of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Search methods

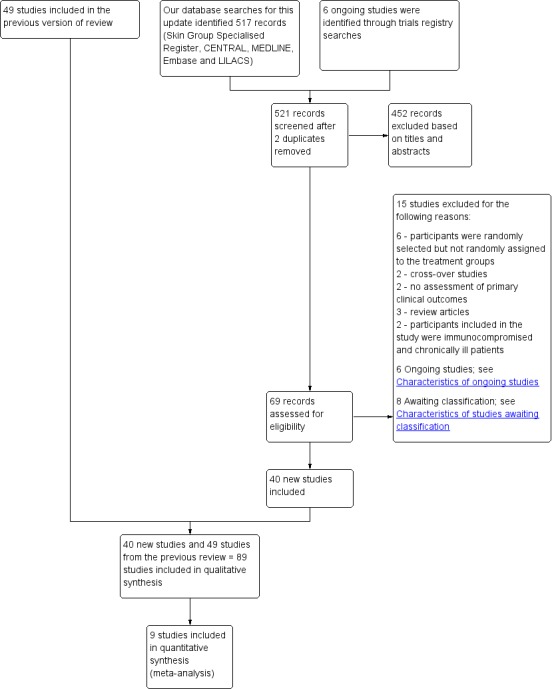

We updated our searches of the following databases to November 2016: the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and LILACS. We also searched five trials registers and checked the reference lists of included studies for further references to relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We wrote to national programme managers, general co‐ordinators, directors, clinicians, WHO‐EMRO regional officers of endemic countries, pharmaceutical companies, tropical medicine centres, and authors of relevant papers for further information about relevant unpublished and ongoing trials. We undertook a separate search for adverse effects of interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis in September 2015 using MEDLINE.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials of either single or combination treatments in immunocompetent people with OWCL confirmed by smear, histology, culture, or polymerase chain reaction. The comparators were either no treatment, placebo/vehicle, and/or another active compound.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias and extracted data. We only synthesised data when we were able to identify at least two studies investigating similar treatments and reporting data amenable to pooling. We also recorded data about adverse effects from the corresponding search.

Main results

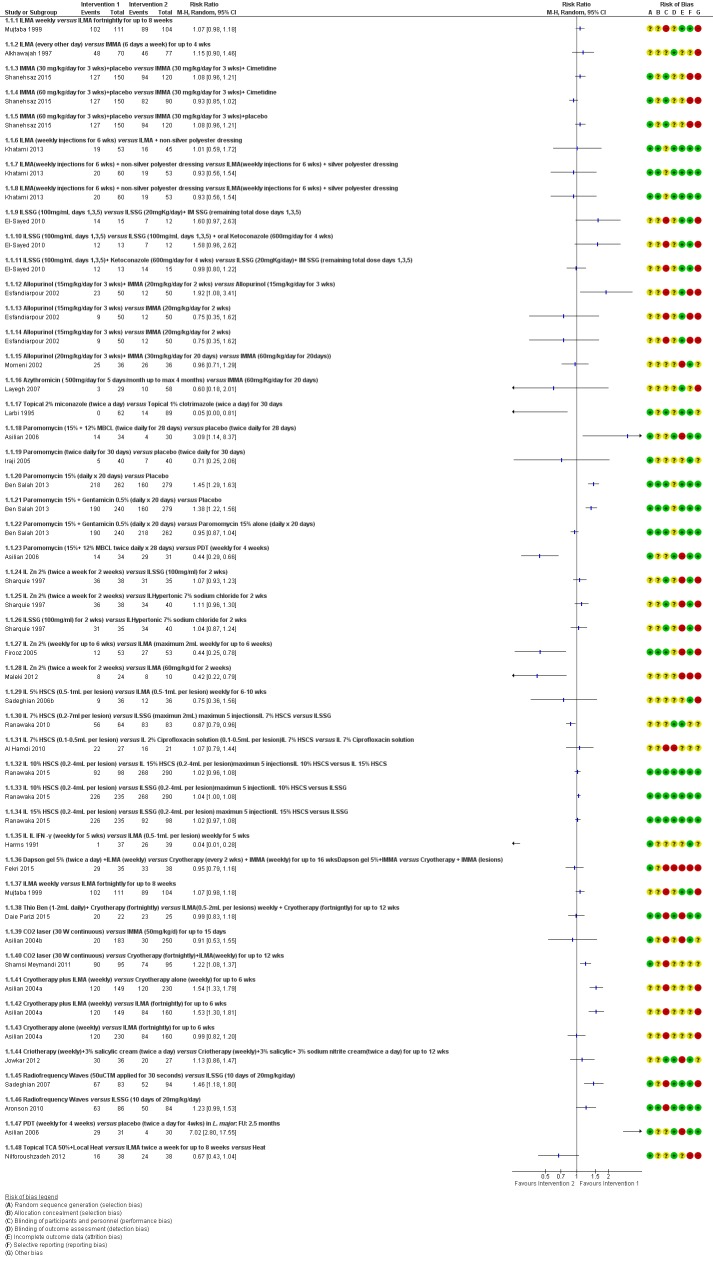

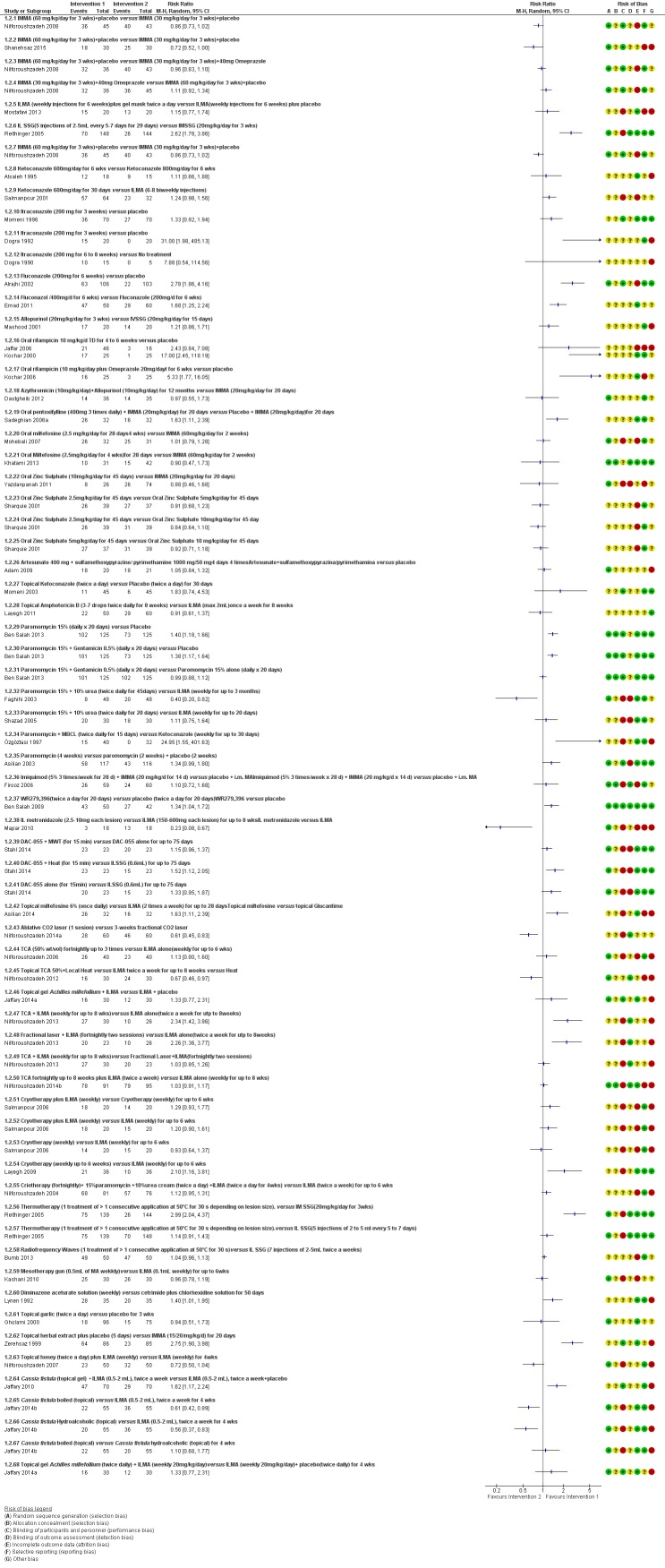

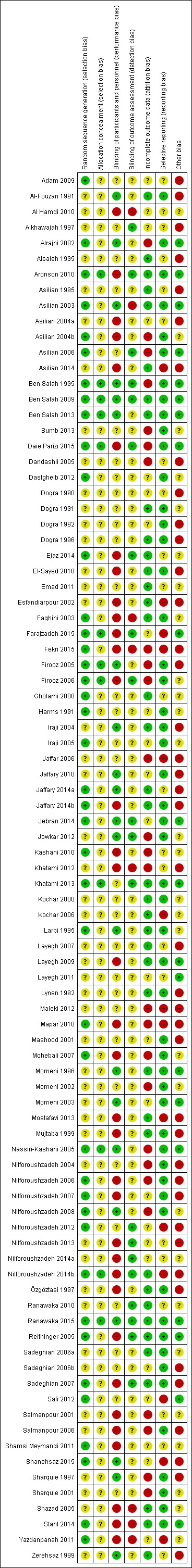

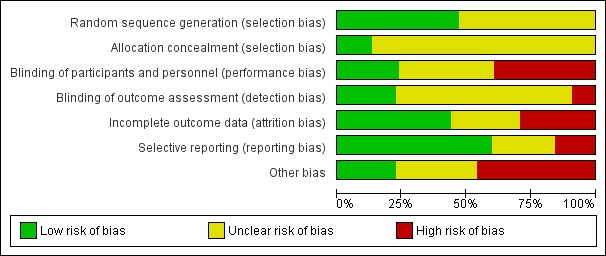

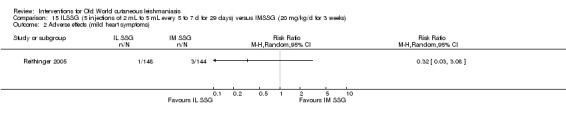

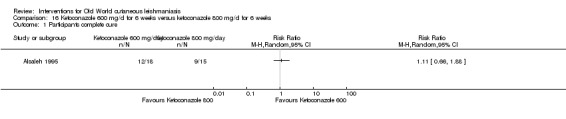

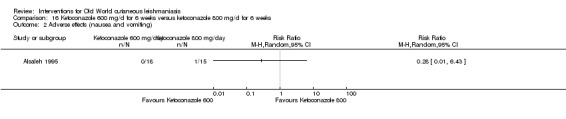

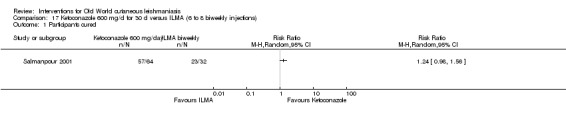

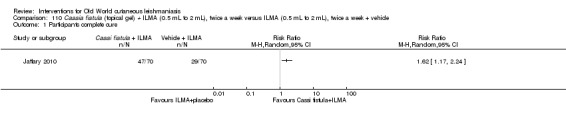

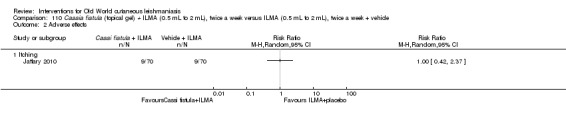

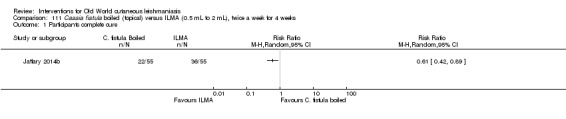

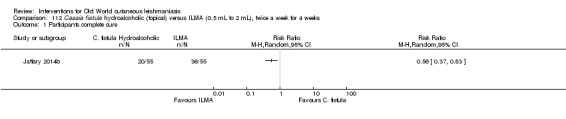

We included 89 studies (of which 40 were new to this update) in 10,583 people with OWCL. The studies included were conducted mainly in the Far or Middle East at regional hospitals, local healthcare clinics, and skin disease research centres. Women accounted for 41.5% of the participants (range: 23% to 80%). The overall mean age of participants was 25 years (range 12 to 56). Most studies lasted between two to six months, with the longest lasting two years; average duration was four months. Most studies were at unclear or high risk for most bias domains. A lack of blinding and reporting bias were present in almost 40% of studies. Two trials were at low risk of bias for all domains. Trials reported the causative species poorly.

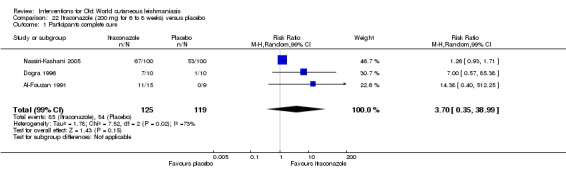

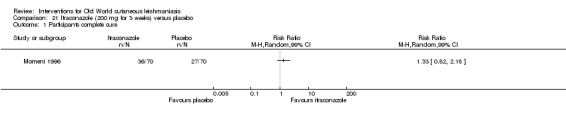

Here we provide results for the two main comparisons identified: itraconazole (200 mg for six to eight weeks) versus placebo; and paromomycin ointment (15% plus 10% urea, twice daily for 14 days) versus vehicle.

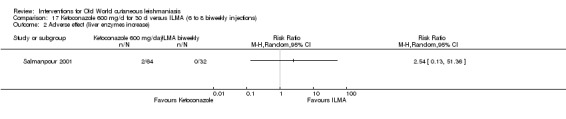

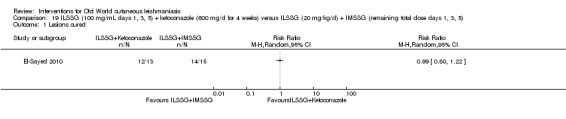

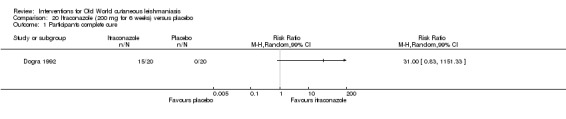

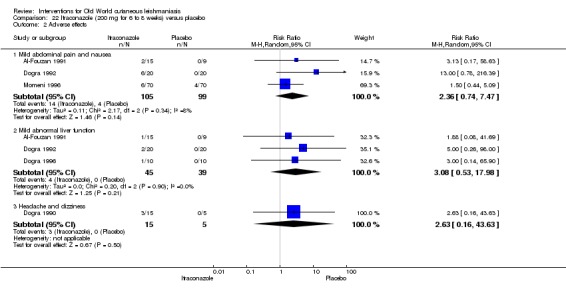

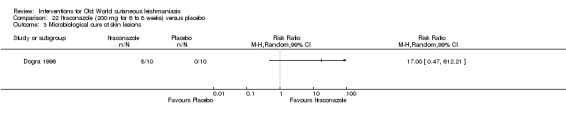

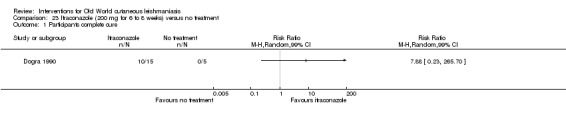

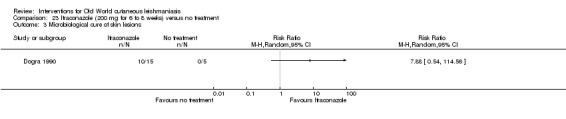

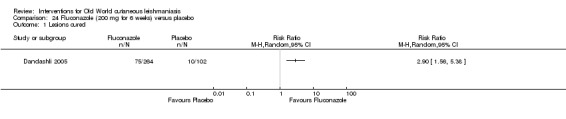

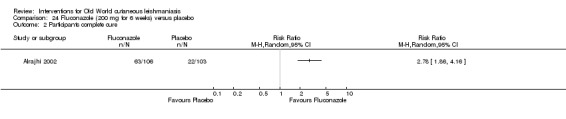

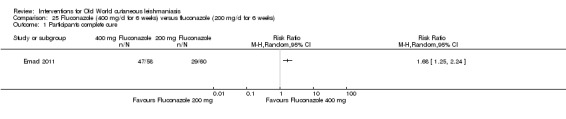

In the comparison of oral itraconazole versus placebo, at 2.5 months' follow up, 85/125 participants in the itraconazole group achieved complete cure compared to 54/119 in the placebo group (RR 3.70, 95% CI 0.35 to 38.99; 3 studies; 244 participants). In one study, microbiological or histopathological cure of skin lesions only occurred in the itraconazole group after a mean follow‐up of 2.5 months (RR 17.00, 95% CI 0.47 to 612.21; 20 participants). However, although the analyses favour oral itraconazole for these outcomes, we cannot be confident in the results due to the very low certainty evidence. More side effects of mild abdominal pain and nausea (RR 2.36, 95% CI 0.74 to 7.47; 3 studies; 204 participants) and mild abnormal liver function (RR 3.08, 95% CI 0.53 to 17.98; 3 studies; 84 participants) occurred in the itraconazole group (as well as reports of headaches and dizziness), compared with the placebo group, but again we rated the certainty of evidence as very low so are unsure of the results.

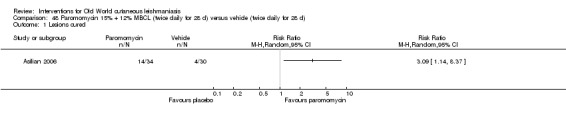

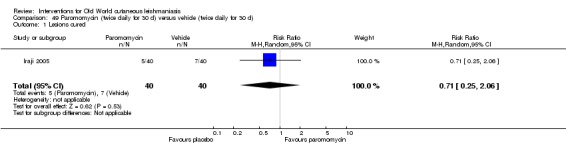

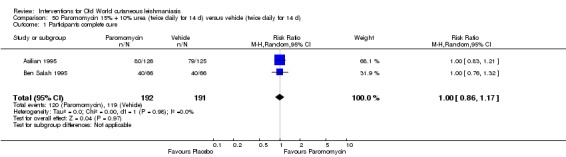

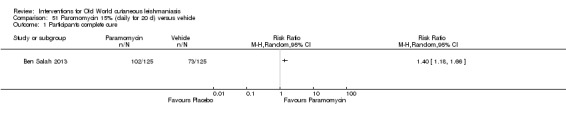

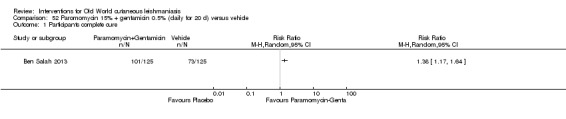

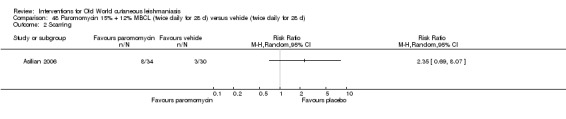

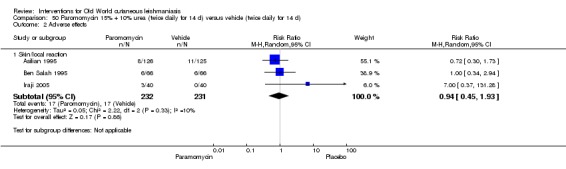

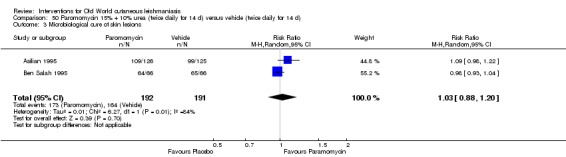

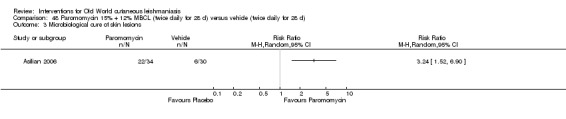

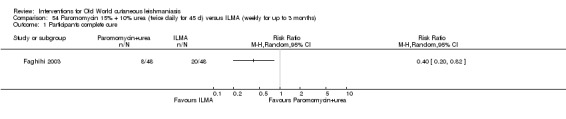

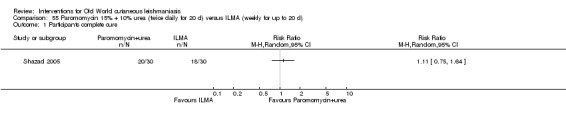

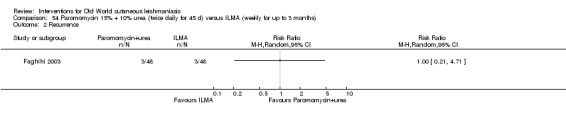

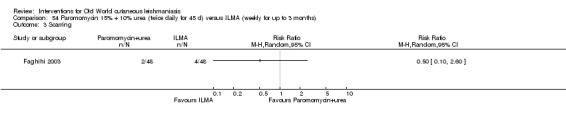

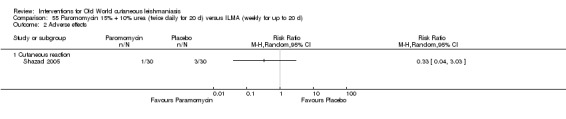

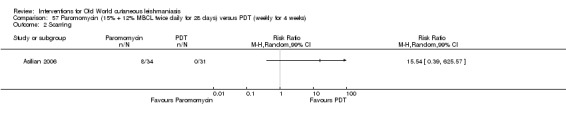

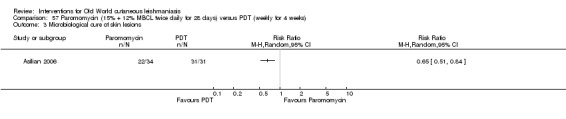

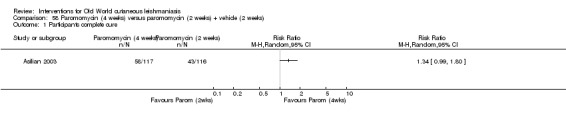

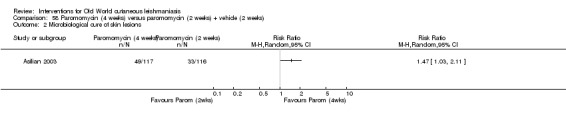

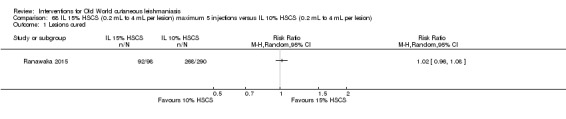

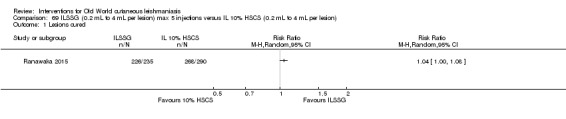

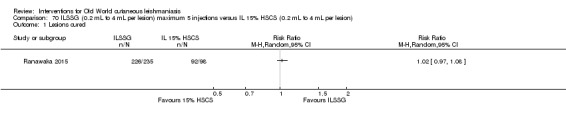

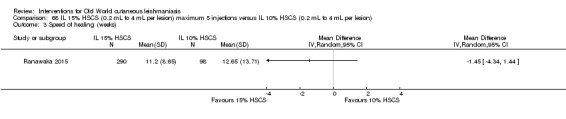

When comparing paromomycin with vehicle, there was no difference in the number of participants who achieved complete cure (RR of 1.00, 95% CI 0.86, 1.17; 383 participants, 2 studies) and microbiological or histopathological cure of skin lesions after a mean follow‐up of 2.5 months (RR 1.03, CI 0.88 to 1.20; 383 participants, 2 studies), but the paromomycin group had more skin/local reactions (such as inflammation, vesiculation, pain, redness, or itch) (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.01; 4 studies; 713 participants). For all of these outcomes, the certainty of evidence was very low, meaning we are unsure about these results.

Trial authors did not report the percentage of lesions cured after the end of treatment or speed of healing for either of these key comparisons.

Authors' conclusions

There was very low‐certainty evidence to support the effectiveness of itraconazole and paromomycin ointment for OWCL in terms of cure (i.e. microbiological or histopathological cure and percentage of participants completely cured). Both of these interventions incited more adverse effects, which were mild in nature, than their comparisons, but we could draw no conclusions regarding safety due to the very low certainty of the evidence for this outcome.

We downgraded the key outcomes in these two comparisons due to high risk of bias, inconsistency between the results, and imprecision. There is a need for large, well‐designed international studies that evaluate long‐term effects of current therapies and enable a reliable conclusion about treatments. Future trials should specify the species of leishmaniasis; trials on types caused by Leishmania infantum, L aethiopica, andL donovani are lacking. Research into the effects of treating women of childbearing age, children, people with comorbid conditions, and those who are immunocompromised would also be helpful.

It was difficult to evaluate the overall efficacy of any of the numerous treatments due to the variable treatment regimens examined and because RCTs evaluated different Leishmania species and took place in different geographical areas. Some outcomes we looked for but did not find were degree of functional and aesthetic impairment, change in ability to detect Leishmania, quality of life, and emergence of resistance. There were only limited data on prevention of scarring.

Keywords: Animals; Humans; Anti‐Infective Agents; Anti‐Infective Agents/therapeutic use; Antiprotozoal Agents; Antiprotozoal Agents/therapeutic use; Complementary Therapies; Cryotherapy; Hot Temperature; Hot Temperature/therapeutic use; Laser Therapy; Leishmania major; Leishmania tropica; Leishmaniasis, Cutaneous; Leishmaniasis, Cutaneous/therapy; Photochemotherapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Treatments for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis

Background

Old World cutaneus leishmaniasis (OWCL) is an infection caused by the Leishmania parasite, which is passed onto humans by the bite of sandflies. It is a serious skin disease associated with a broad range of signs, symptoms, and degrees of severity. We wanted to assess the competence and safety of all available treatments for OWCL.

Review question

We assessed participants with a healthy immune response who had OWCL diagnosed by laboratory methods. Treatments had to be given alone or in combination with another treatment, and they were compared against no treatment, placebo (an inactive substance) only, or another active treatment. Some of the main outcomes we were interested in included the percentage of wounds cured after the end of treatment, the number of participants completely cured after the end of treatment, speed of healing, side‐effects of treatment, and clearance of parasites (i.e. infection).

Study characteristics

We reviewed 89 clinical trials, which included 10,583 people, in total, with OWCL. We included participants of both sexes and all ages (mean 24.5 years); most participants were over 18 years of age. Most studies were carried out in single centres in different countries, mainly in the Far or Middle East, and lasted between two to six months. We included a variety of treatments, such as antimonials, antifungals, and antibiotics, which were administered either directly onto the skin or into a wound, taken by mouth, or physically applied (e.g. laser treatment, heat therapy, etc.). Most of the included studies assessed OWCL caused by two species of parasites known as Leishmania major (L. major) andLeishmania tropica (L. tropica).

Key results

The evidence is current to November 2016.

Two of the most important treatments that we assessed in this review were itraconazole, an antifungal drug taken by mouth, and paromomycin, an antibiotic applied as an ointment. Trials compared both to a placebo tablet or inactive cream (vehicle).

Participants received 200 mg itraconazole for six to eight weeks or paromomycin ointment at a concentration of 15% plus 10% urea, twice daily for 14 days.

When assessed on average 2.5 months after treatment, more participants were completely cured and cleared of the infection‐causing parasites with itraconazole than placebo, but they also had more side effects (mild stomach pain, sickness, and abnormal liver function, as well as headaches and dizziness).

When paromomycin ointment was compared with placebo, there was no difference in the number of completely cured participants or the number who were found to be cleared of parasites when assessed on average 2.5 months after treatment, but those in the paromomycin treatment group had more contained skin reactions (such as swelling, blistering, pain, redness, or itch).

However, as the certainty of the evidence for these outcomes for these particular comparisons was very low, we are not sure of the accuracy of these results.

Neither of our key treatment comparisons assessed the percentage of wounds cured after the end of treatment and speed of healing (i.e. time taken to be cured).

Quality of the evidence

The overall certainty of the evidence for the different outcomes in the two main comparisons was very low. Important reasons for this were that studies were not blinded, or had a small sample size, making the results less precise. Some of the evidence only focused on young people, and the results greatly varied between each study.

We need more research to fill in the following research gaps: 1) trials of OWCL caused by other types of infection such as L. infantum, L. aethiopica,or L. donovani; 2) involving specific subgroups of people such as children; 3) assessing effectiveness and safety of different anti‐Leishmania drugs compared with placebo in self‐healing forms of leishmaniasis or with traditional first‐choice antimonial treatment in complicated form (defined as more than four lesions over 4 cm in size, located close to an opening or small joints, for which previous treatment has failed); and 4) assessing areas such as wound healing and patient‐reported outcomes, such as quality of life. In addition, few studies assessed relevant issues such as drug resistance. International collaboration is required to improve the quality and standardisation of future trials in order to develop a better evidence‐based approach.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison.

Itraconazole (200 mg for 6 to 8 weeks) versus placebo for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis

| Itraconazole (200 mg for 6‐8 weeks) versus placebo for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis Settings: Kuwait, India, and Iran Intervention: itraconazole (200 mg for 6‐8 weeks) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Itraconazole (200 mg for 6‐8 weeks) | |||||

| Percentage of lesions cured after the end of treatment | Not measured in this comparison | |||||

| Percentage of participants with complete cure Follow‐up: mean 2.5 months | Study population | RR 3.70 (0.35 to 38.99) | 244 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | — | |

| 454 per 1000 | 1000 per 1000 (159 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 100 per 1000 | 370 per 1000 (35 to 1000) | |||||

|

Adverse effects Mild abdominal pain and nausea Adverse effects Mild abnormal liver function |

40 per 1000 0 per 1000 |

95 per 1000 (30 to 302) 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

RR 2.36 (0.74 to 7.47) RR 3.08 (0.53 to 17.98) |

204 (3 studies) 84 (3 studies) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc |

— |

| Speed of healing (time taken to be 'cured') | Neither of the studies reported speed of healing (time taken to be 'cured') in this comparison. | |||||

| Microbiological or histopathological cure of skin lesions Follow‐up: mean 2.5 months | Not estimable | Not estimable | RR 17.00 (0.47 to 612.21) | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | There were zero events in the placebo group |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality/certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality/certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality/certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality/certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aDowngraded by 4 levels due to: risk of bias (2 RCTs have many uncertain items), inconsistency (there is considerable heterogeneity ‐ I² = 73%), and imprecision (2 levels due to wide 95% confidence intervals, crossing the line of no effect). bDowngraded by 3 levels due to: risk of bias (many uncertain items in the risk of bias judgment), and imprecision (2 levels due to wide 95% confidence intervals, crossing the line of no effect). cDowngraded by 3 levels due to: risk of bias (many uncertain items in the risk of bias judgment), and imprecision (2 levels due to wide 95% confidence intervals, crossing the line of no effect). dDowngraded by 3 levels due to: risk of bias (many uncertain items in the risk of bias judgment), and imprecision (2 levels due to wide 95% confidence intervals; this outcome is only reported for one study involving 20 participants).

Summary of findings 2.

Paromomycin ointment versus vehicle for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis

| Paromomycin ointment versus matched vehicle for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis | |||||

| Patient or population: patients with Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis Settings: primary health centres, Iran and Tunisia Intervention: paromomycin ointment (15% + 10% urea) twice daily for 14 days Comparison: vehicle | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Vehicle | Paromomycin ointment (15% + 10% urea) twice daily for 14 days | ||||

| Percentage of lesions cured after the end of treatment | Not measured in this comparison | ||||

| Percentage of participants with complete cure Follow‐up: mean 2.5 months | Study population | RR 1.00 (0.86 to 1.17) | 383 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa | |

| 623 per 1000 | 623 per 1000 (536 to 729) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 619 per 1000 | 619 per 1000 (532 to 724) | ||||

| Adverse effects Skin/local reactions | Study population | RR 1.42 (0.67 to 3.01) | 713 (4 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | |

| 96 per 1000 | 136 per 1000 (64 to 287) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 90 per 1000 | 128 per 1000 (60 to 271) | ||||

| Speed of healing (time taken to be 'cured') | Not measured in this comparison | ||||

| Microbiological or histopathological cure of skin lesions Follow‐up: mean 2.5 months | Study population | RR 1.03 (0.88 to 1.2) | 383 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | |

| 859 per 1000 | 884 per 1000 (756 to 1000) | ||||

| Moderate | |||||

| 792 per 1000 | 816 per 1000 (697 to 950) | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; N/A: not applicable. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality/certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality/certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality/certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality/certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aDowngraded by 4 levels due to risk of bias (1 RCT has many uncertain risks), indirectness (2 levels because one of the studies focused on young people), and imprecision (the confidence interval around the estimate risk ratio ranges from a 14% reduction to a 17% increase in the risk ratio for healing with paromomycin). bDowngraded by 4 levels due to risk of bias (2 RCTs have many uncertain risks), indirectness (2 levels because one of the studies focused on young people), and imprecision (the confidence interval crosses the line of no effect). cDowngraded by 5 levels due to risk of bias (1 RCT has many uncertain risks), inconsistency (there is considerable heterogeneity ‐ I² = 84%), indirectness (2 levels because one of the studies focused on young people), and imprecision (the confidence interval around the estimate risk ratio ranges from a 12% reduction to a 20% increase in the risk ratio for healing with paromomycin).

Background

Please see Table 117 for a glossary of terms used.

Table 1.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

| Antimonials | Pharmaceutical agents containing antimony. Antimony‐containing compounds (meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate) are the principal medications used to treat leishmaniases, an infection caused by a protozoan parasite. |

| Arthralgia | Pain in the joints. The causes of arthralgia are varied and range, from a joints perspective, from degenerative and destructive processes such as osteoarthritis and sports injuries to inflammation of tissues surrounding the joints, such as bursitis. |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | An arrhythmia is an abnormal heart rhythm. Many types of arrhythmia have no symptoms. When symptoms are present these may include palpitations or feeling a pause between heartbeats. More seriously there may be lightheadedness, passing out, shortness of breath, or chest pain. |

| Cutaneous necrosis | The death of living tissues in response to disease or injury. |

| Cytolysis | The degeneration or dissolution of cell caused by the disruption of cell membrane. |

| Exudate | A fluid with a high content of protein and cellular debris that has escaped from blood vessels and has been deposited in tissues or on tissue surfaces, usually as a result of inflammation. |

| Human monocytes | Monocytes are the biggest type of white blood cell in the immune system. Originally formed in the bone marrow, they are released into our blood and migrate into the connective tissue where they differentiate into macrophages. When certain germs enter the body, they quickly rush to the site of attack. |

| Hypotension | A systolic blood pressure reading (the top number) of 90 millimetres of mercury (mmHg) or less a diastolic blood pressure reading (the bottom number) of 60 mmHg or less is generally considered low blood pressure. The causes of low blood pressure can range from dehydration to serious medical or surgical disorders. |

| Immune response modifier | Any of a broad family of biomolecules that up‐ or down‐regulate, or restore immune responsiveness, which are generated after T cells recognise an antigen present on the surface of a self‐antigen‐presenting cell, which, once activated, produce multiple cytokines. |

| Immunolabeling | A biochemical process that enables the detection and localisation of an antigen to a particular site within a cell, tissue, or organ. Antigens are organic molecules, usually proteins, capable of binding to an antibody. These antigens can be visualised using a combination of antigen‐specific antibodies as well as a means of detection, called a tag, that is covalently linked to the antibody. If the immunolabeling process is meant to reveal information about a cell or its substructures, the process is called immunocytochemistry. Immunolabeling of larger structures is called immunohistochemistry. |

| In vitro | Biological processes or reactions made to occur outside the living organism in an artificial environment, such as a culture medium. |

| Intralesional meglumine antimoniate | Meglumine antimoniate (or Glucantime) is a medicine used for treating leishmaniasis. It belongs to a group of compounds known as the pentavalent antimonials. |

| Lymphadenopathies | Lymph nodes that have an abnormal in size, number or consistency; often used as a synonym for swollen or enlarged lymph nodes. Common causes of lymphadenopathy are infection, autoimmune disease, or malignancy. |

| Lymphatic channels | The vessels that transport lymph throughout the body. Lymph is a clear fluid that contains cells important for forming antibodies that fight infection. |

| Lymphokine | Any of various soluble protein mediators released by sensitised lymphocytes on contact with antigen, and believed to play a role in macrophage activation, lymphocyte transformation, and cell‐mediated immunity. They regulate immune responses through differentiation, amplification, and inhibition of cell functions. Lymphokines may also have a cytotoxic effector function. Used as biologic response modifiers in the treatment of cancer. |

| Macrophages | White blood cells (activated monocytes) that protect the body against infection and foreign substances by breaking them down into antigenic peptides recognised by circulating T cells. |

| Miltefosine | An oral alkyl phosphocholine analogue used to treat cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis. Interacts with lipids and sterols in the Leishmania membrane resulting in inhibition of mitochondria and apoptotic cell death. |

| Mucous membranes | The mucous membranes (or mucosae or mucosas; singular mucosa) are linings of mostly endodermal origin, covered in epithelium, which are involved in absorption and secretion. They line cavities that are exposed to the external environment and internal organs. |

| Myalgia | Myalgia, or muscle pain, is a symptom of many diseases and disorders. The most common causes are the overuse or over‐stretching of a muscle or group of muscles. Myalgia without a traumatic history is often due to viral infections. Long‐term myalgias may be indicative of a metabolic myopathy, some nutritional deficiencies or chronic fatigue syndrome. |

| Nodular lymphangitis | Nodular lymphangitis is a distinct clinical entity, separate from lymphangitis. This disorder is characterised by inflammatory nodules along the lymphatics draining a primary skin infection |

| Papule | A solid, rounded growth that is elevated from the skin, usually inflammatory but nonsuppurative. A papule is usually less than 1 cm across. |

| Parenteral | Administration of a medicinal or therapeutic substance, other than through the gastrointestinal or respiratory tracts, e.g. by intravenous, intramuscular or subcuticular injection. |

| Pentamidine | Pentamidine (e.g. isethionate) is an antiprotozoal and antifungal agent of the class of aromatic diamidines, administered intravenously or intramuscularly in treatment of early African trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis, and intravenously, intramuscularly, or by oral inhalation in treatment and prophylaxis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. |

| Pentavalent antimony | Pentavalent antimonials are a group of compounds used for the treatment of leishmaniasis. The first pentavalent antimonial used was urea stibamine: first introduced in the 1930s, it fell out of favour in the 1950s due to higher toxicity compared to sodium stibogluconate. The compounds currently available for clinical use are: sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam; manufactured by GlaxoSmithKline; available in the USA and UK), which is administered by slow intravenous injection, intralesional or intramuscular injection, and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime; manufactured by Aventis; available in Brazil, France and Italy), which is administered by intramuscular, intralesional, or intravenous injection. |

| Promastigotes | Term now generally used instead of 'leptomonad' or 'leptomonad stage' to avoid confusion with the flagellate genus Leptomonas. It denotes the flagellate stage of a trypanosomatid protozoan in which the flagellum arises from a kinetoplast in front of the nucleus and emerges from the anterior end of the organism; usually an extracellular phase, as in the insect intermediate host (or in culture) of Leishmania parasites. |

| Protozoan | Any of a group of single‐celled, usually microscopic, eukaryotic organisms, such as amoebas, ciliates, flagellates, and sporozoans. |

| ThermoMed device | The ThermoMed is a battery‐operated device that delivers precisely controlled localised current field radiofrequency heat to selectively destroy certain diseased tissue and is recommended by the World Health Organization as an alternative therapy for cutaneus leishmaniasis. |

| Thermotherapy | The treatment of disease by the application of heat. Thermotherapy may be administered as dry heat with heat lamps, diathermy machines, electric pads, or hot water bottles or as moist heat with warm compresses or immersion in warm water. Warm soaks or compresses may be used to treat local infections, relax muscles and relieve pain in patients with motor problems, and promote circulation in peripheral vascular disorders such as thrombophlebitis. |

Description of the condition

Definition

Desjeux 1996 describes leishmaniasis as "a group of diseases caused by infection with protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania", transmitted by bites from sandflies infected with the parasite. Leishmaniasis has two main clinical forms of presentation (cutaneous and visceral), which are associated with a broad range of signs, symptoms, and degrees of severity (Herwaldt 1999; Reithinger 2007). Depending on its geographical distribution, cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is classified as New World cutaneous leishmaniasis (NWCL) or Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis (OWCL). The latter commonly – though not exclusively – presents as chronic, painless ulcers or nodules. Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis is complex and should depend on the Leishmania species involved, the area of acquisition of the infection, and the clinical form (Monge‐Maillo 2013). Management may vary from local or systemic treatment to no treatment.

Epidemiology and impact

In many tropical and subtropical low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), protozoan parasites are amongst the most common infectious agents and have serious consequences for socioeconomic development (Alvar 2006; WHO 2002). The World Health Organization (WHO) considers leishmaniasis to be one of the most serious parasitic diseases, and the World Health Assembly has advocated for prioritising their control (WHO 2007).

An estimated 700,000 to 1.2 million new CL cases occur each year (Alvar 2012). CL is widely distributed, with 70% to 75% of the global incidence located mainly in 10 countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Colombia, Brazil, Iran, Syria, Ethiopia, North Sudan, Costa Rica, and Peru (Alvar 2012). Global incidence of OWCL is estimated at more than 900,000 cases per year, distributed from the Mediterranean basin across the Near East to Northwest India, with a few foci in Central China as well as a thin band across West Africa and in the Horn of Africa (Alvar 2012; Pigott 2014). OWCL is also increasingly present in immigrants, military personnel, humanitarian aid workers, tourists, and travellers from endemic areas (Reithinger 2007).

Immunosuppression is also a factor that can increase the prevalence of CL, altering its clinical presentation and treatment response (van Griensven 2014). This factor is most closely associated with HIV, but recent years have seen a worldwide increase in other immunosuppressive conditions, mainly because of better medical care for chronic illnesses and the use of immunosuppressive drugs like tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (van Griensven 2014). In any case, the reported leishmaniasis case figures seem to be only a fraction of the true burden, and the disease appears to be underestimated and on the rise in several countries (Alvar 2012). Leishmaniasis, as with many other neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), occurs mostly in LMICs, affecting rural and remote locations that may escape official data sources (WHO 2010).

Aetiology and transmission

Five Leishmania species cause OWCL: L major, L tropica, L infantum, L donovani, andL aethiopica (Pace 2014). Most cases are due to L major, with around 500,000 cases per year; L tropica, with 400,000 cases per year; followed by L aethiopica, with 50,000 cases per year (den Boer 2011). Transmission of leishmaniasis is through a complex life cycle involving sandflies belonging to the Phlebotomus species (Pace 2014). Non‐vector transmission (e.g. by accidental laboratory infection, blood transfusion, or organ transplantation) is possible but rare (Cardo 2006). Transmission of leishmaniasis can be either anthroponotic or zoonotic (Pace 2014).

Zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL), occurring mostly in rural areas, is where the parasite is transmitted from a range of animals to humans (WHO 2010). It is geographically distributed in the Middle East, North‐western China, and North Africa, where it may be caused by L major, and in the Mediterranean basin where it is mostly caused by L infantum (Pace 2014). The Old World ZCL often heals spontaneously after two to four months, although in some cases it may persist for as long as five years (WHO 2010).

Anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) is transmitted from person to person, mainly in urban areas; it is geographically distributed in the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and western Asia (WHO 2010). ACL is mostly caused by L tropica and also by L donovani, which may cause post‐kala‐azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in Asia (India, Nepal, and Bangladesh) and in East Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan) (Alvar 2012).

Clinical manifestations

CL can affect the skin and mucous membranes and has been categorised into five different clinical forms: localised, recidivans, diffuse, mucosal, and PKDL.

Localised leishmaniasis

In the localised form, the parasite is confined to the skin (Gonzalez 2008). After an incubation period of 1 to 12 weeks, a papule or bump develops at the site of the insect bite, and the papule grows and turns into an ulcer (González 2009). A typical lesion of the localised form of CL is a painless papule or ulcer covered with an adherent crust of dried exudate and located on exposed parts of the body such as the face, arms, or legs (Gonzalez 2008; González 2009). CL due to L infantum usually causes single lesions. By contrast, L tropica frequently causes multiple lesions, as does L major, in this case often severely inflamed and ulcerated lesions that heal slowly and cause large disfiguring or disabling scars. Other variations exist as well: some people may have as many as 200 simple skin lesions, with some growing but not ulcerating (sporotrichoid), while certain Leishmania species also infect the lymphatic system, producing lesions along the lymphatic channels (nodular lymphangitis) (Gonzalez 2008). Secondary bacterial infection is common, causing pain and serious disability (Blum 2014). Most lesions heal spontaneously over months or years, leaving permanent scarring with skin thinning. Scarring of leishmaniasis typically displays a depigmented centre and a pigmented border (Reithinger 2007).

Leishmaniasis recidivans

This form appears in around five per cent of people with CL by L tropica and is characterised by microsatellite and confluent lesions that relapse and finally ulcerate on the border of previous scars (Sharifi 2010; WHO 2010).

Diffuse leishmaniasis

This form affects only the skin but with generalised skin lesions; it is seen mainly in Africa and transmitted by L aethiopica (Alrajhi 2003).

Mucosal leishmaniasis

In mucosal leishmaniasis, the parasite may spread to the mucous membranes, especially those of the nose, mouth, and throat, causing extensive damage and disfiguration. It mainly occurs in South America, but it can also be caused by species from Old World countries including L tropica, L major, and L infantum (WHO 2010).

Post‐kala‐azar dermal leishmaniasis

PKDL is a form of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis and a sequel of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) that may appear in affected individuals up to 20 years after being partially treated or untreated or even in those who supposedly received adequate treatment (Rathi 2005). PKDL is mostly seen in areas where L donovani is endemic, such as in Asia (India, Nepal, and Bangladesh) and East Africa (Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sudan) (Alvar 2012).

Diagnosis

Clinically diagnosed OWCL should be confirmed using the traditional diagnostic techniques of smear, parasite culture, and histological analysis of skin by aspiration, scrapings, or biopsies (Saab 2015). Circulating antibodies in the bloodstream are generally low or undetectable in cases of OWCL (Masmoudi 2013). Modern molecular diagnostic techniques, mainly the polymerase chain reaction test (PCR), appear to be the most sensitive single diagnostic test for species identification in skin samples (Faber 2003; Schallig 2002). Identification of the Leishmania species involved is essential for selecting the most appropriate treatment.

Description of the intervention

Issues of treatment in CL are difficult to deal with because there are many factors that can influence the efficacy of drugs: the size, the number, and the appearance of the lesions; the duration of the disease prior to treatment; the frequency and time to self‐healing; the frequency of relapse and re‐infection; the frequency and severity of either mucosal or diffuse involvement; immunosuppression; co‐infections; prior anti‐Leishmania treatment; and the knowledge of resistance to anti‐Leishmania drugs (Gonzalez 2008). Laboratory studies have described acquired resistance to anti‐Leishmania drugs for decades, but only recently has clinical resistance been described. Monitoring resistance is currently controversial due to an inadequate correlation between clinical and in vitro resistance and a need for knowledge about the biochemical and molecular mechanisms of resistance (Croft 2006).

The location of the lesion (e.g. face or joints) and the patient's sex and age often determine the choice of treatment (González 2009). Other factors are intrinsic and related to the different Leishmania species (Safi 2012). An effective treatment in one geographical area for a given organism may not work in a different geographical area or for a different organism in the same location. In these cases, efficacy depends not only on the Leishmania species but also on the response of the person to the parasite and factors such as immunity, variable clinical response to treatments, drug toxicity, drug resistance, HIV co‐infection and adherence (Blum 2014).

Different authors have described many treatments for OWCL (Modabber 2007; WHO 2008; WHO 2010), of which we summarise the most relevant in Table 118. Nonetheless, several authors have pointed out the lack of properly controlled clinical trials (Hepburn 2001, Herwaldt 1999; Moskowitz 1999; Monge‐Maillo 2013). Another disadvantage and paradox is the lack of availability of most of these drugs in rural and poorer areas where leishmanias appears most frequently (Gonzalez 2008). Systemic treatments are generally given to those with CL who present with big (≥ 5 cm), multiple (> 5), or disseminated lesions; in those who have simple lesions involving cosmetically sensitive areas or joints, with mucosal reaction, or with the presence of nodular lymphangitis or lymphadenopathies; or for whom local therapy has failed (Blum 2014). For people with immunosuppression, there is controversy. Some experts consider that acquired or induced immunosuppression is a risk factor for developing mucosal leishmaniasis, so they recommend systemic treatment. Meanwhile, other experts have considered different treatment for the same type of people (Blum 2012).

Table 2.

Interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis

| Drug | Doses |

| Systemic antimonials | |

| Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam, Stibanate) Meglumine antimonate (Glucantime) Combined with pentoxifylline |

20 mgSb v+/kg/d intramuscularly or intravenously for 20‐30 days 400 mg orally 3 times a day for 10–20 days |

| Intralesional antimonials | |

| Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam, Stibanate) Meglumine antimonate (Glucantime) |

1–5 mL per session every 3–7 days. Up to 10 sessions depending on the clinical response, but most patients require ≤ 5 sessions |

| Non‐antimonial systemic treatments | |

| Fluconazole | 200 mg orally daily for 6 weeks |

| Miltefosine | 50 mg orally three times daily for 28 days |

| Liposomal amphotericin B | 3 mg/kg/d IV on days 1‐5 and 10 (18 mg/kg total dose) |

| Non‐antimonial topical or intralesional therapies | |

| 15% paromomycin/12% methylbenzethonium chloride | Ointment twice daily for 10‐20 days |

| 15% paromomycin/0.5% gentamicin sulphate | Twice a day for 20 days |

| Physical therapies | |

| Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen | Frozen for 10‐30 s and thaw applied locally 2‐3 times in each session, repeated every 1‐4 weeks to complete healing (usually 2‐4 sessions) |

| Local heat therapy | 50°‐55ºC for 30 s by: Infrared light Direct current electrical stimulation Ultrasound Laser Radiofrequency waves ThermoMed device |

Systemic and intralesional antimonials

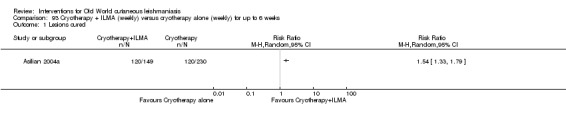

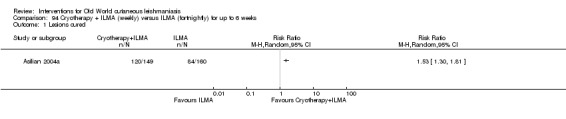

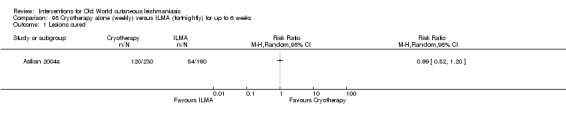

Meglumine antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate

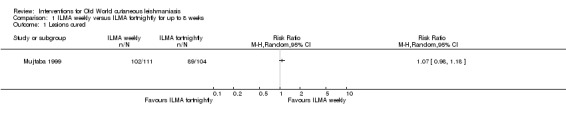

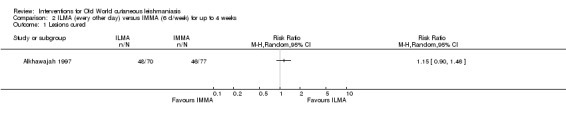

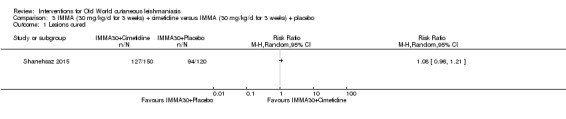

The current mainstays of systemic treatment for OWCL are the pentavalent antimony (Sbv+) compounds sodium stibogluconate (SSG) (Pentostam, Stibanate) and meglumine antimoniate (MA) (Glucantime) (Asilian 2004a; WHO 2010); they often constitute the control condition in trials of new treatments. The recommended dosage is 20 mgSbv+/kg/d intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) for 20 to 30 days (WHO 2010); oral administration is not an option. SSG and MA can also be administered intralesionally (IL) with the recommended dosage of 1 mL to 5 mL per session every 3 to 7 days. Up to 10 sessions are needed depending on the clinical response, but most people require less than five sessions.

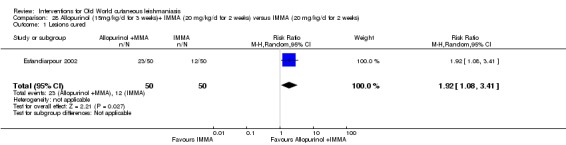

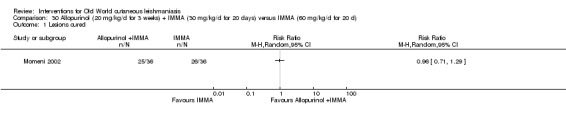

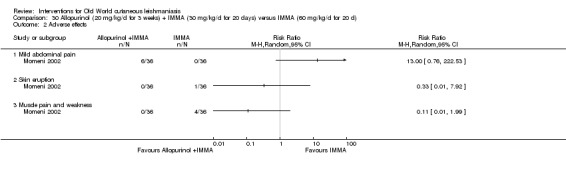

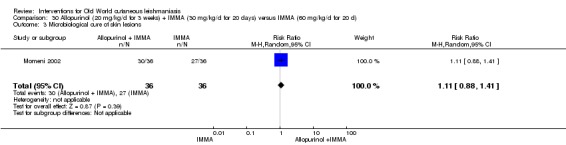

Despite the widespread use of SSG and MA, there are concerns about their cost, toxicity, and the development of drug resistance. Parenteral antimonial drugs are associated with severe adverse and often dose‐dependent effects, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, skin eruptions, dizziness, cardiac arrhythmia, hypotension, arthralgia, myalgia, abdominal discomfort, headache, reversible elevation of hepatocellular enzymes, occasional anaemia, and thrombocytopaenia (Aronson 2010; Ejaz 2014; Esfandiarpour 2002; Farajzadeh 2015; Mohebali 2007; Momeni 2002). Pain at the site of the injection is greater in intralesional administration than in the intravenous/intramuscular route (Iraji 2005; Momeni 2002; Salmanpour 2006). Whilst there is no general consensus on optimum treatment, there are active lines of research to identify alternatives to systemic antimonials (Jowkar 2012). Momeni 2002 has investigated combination therapies with allopurinol, and Sadeghian 2006a with pentoxifylline, as treatments that may help to reduce drug resistance by increasing the efficacy of the antimonials, reducing their doses, or both.

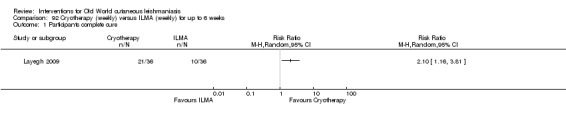

Infiltration of skin lesions (injecting a substance directly into the infected lesion) can be very painful. Adverse effects of IL treatments are burning at the site of injection, itching, inflammation, and vasovagal shock due to severe pain (Layegh 2009; Mapar 2010). A safe and efficient therapeutic method for IL injection is the use of a Dermojet device (Bogenrieder 2003). Preventing blood‐borne transmission of other infectious diseases in LMICs entails reducing the use of injections, implementing blood safety practices, and providing sterile injection equipment in healthcare centres (Kermode 2004; Simonsen 1999). Several studies provide evidence for the efficacy of intralesional pentavalent antimonials for OWCL, mainly in Asia and the Mediterranean basin (Alkhawajah 1997; Uzun 2004). Moreover, local administration reduces the systemic toxicity of antimonials; people may receive anywhere from a few injections or – for those with multiple or complicated lesions – daily injections for up to 40 days (Mujtaba 1999). (Complicated CL is defined as more than 4 lesions over 4 cm in size, which are periorificial or located close to small joints, for which previous treatment has failed. Clinically important lymphatic dissemination is present, as well as underlying immunosuppressive conditions, and "there is significant comorbidity for which systemic treatments could be contraindicated in a benefit–risk assessment (e.g. unbalanced diabetes, malnutrition)" (Gradoni 2017).)

Self‐limiting lesions are normally amenable to weekly or alternate day IL injections of SSG or MA (Alkhawajah 1997; Mujtaba 1999). According to some authors, deficient infiltration of the lesions is one of the most common and important causes of treatment failure with IL antimonials (Faghihi 2003). There are also other studies that have evaluated the association of intralesional pentavalent antimonials as a way to increase the efficacy (Asilian 2003; Munir 2008).

Non‐antimonial systemic treatments

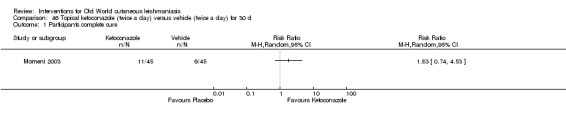

Oral antifungal

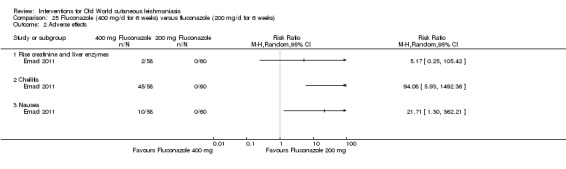

Oral azole antifungal drugs (fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) are potential therapeutic agents in CL. The first reports of oral ketoconazole for the treatment of CL in both the New and the Old World came out in the early 1980s (Urcayo 1982; Weinrauch 1983a; Weinrauch 1983b). However, reports of liver toxicity and low cure rates for certain species led to ketoconazole being withdrawn from the market, making it necessary to search for other azoles (Alrajhi 2002). In the mid‐ to late 1980s, another azole called itraconazole was touted as a treatment for CL (Borelli 1987; Cauwenberg 1986), with different cure rates depending on the species involved (Momeni 1996; Nassiri‐Kashani 2005). Fluconazole, another antifungal azole, has also been used as an alternative therapy for CL, with good cure rates at different doses (Alrajhi 2002; Emad 2011).

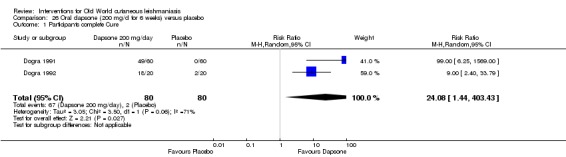

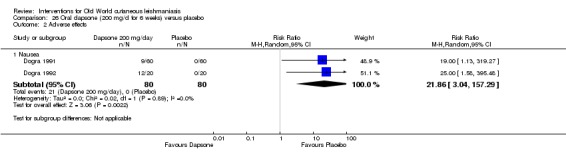

Oral dapsone

Some studies have proposed the antibiotic/antileprotic drug dapsone as an inexpensive oral alternative to the treatment currently used for CL (Dogra 1986; Dogra 1991), although the main side effect of dapsone is blood cell destruction and anaemia (Dogra 1991).

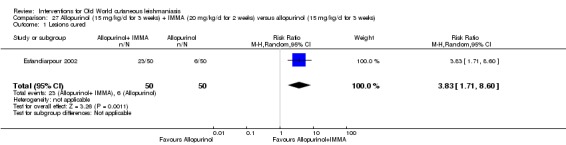

Oral allopurinol

Allopurinol (a medicine used to treat gout) alters protein synthesis and inhibits the growth of Leishmania in vitro (Momeni 2002); different authors have assessed its use as a potential therapeutic agent for the treatment of both CL and VL, mainly in combination with pentavalent antimonials (Chunge 1985; Jha 1983; Kager 1981; Momeni 2002).

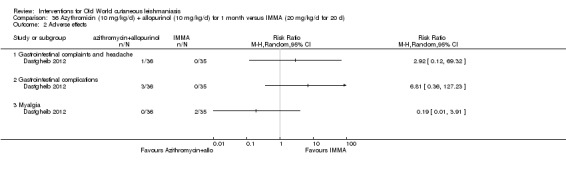

Oral antibiotics

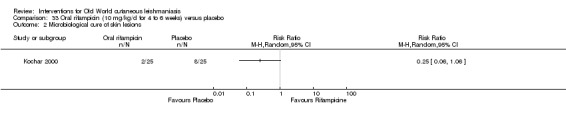

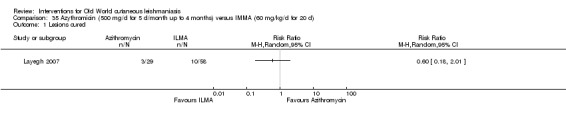

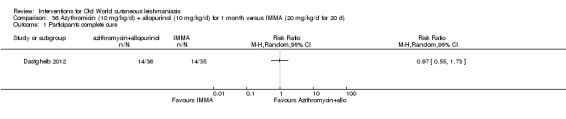

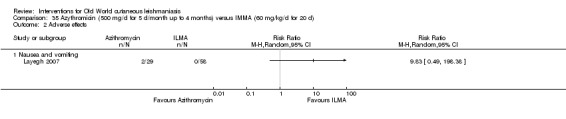

Researchers have also reported several other oral antibiotics like metronidazole and cotrimoxazole as possibly promising anti‐Leishmania agents in the treatment of VL (Rodriguez‐Cuartero 1990), while others have looked into the efficacy of a short‐term course of antibiotic rifampicin for CL (Bygbjerg 1980). Oral azithromycin is another antibiotic that is effective in vitro and in mice (Minodier 2007), but research has not established it as superior to antimonials for OWCL in humans (Layegh 2007), even when combined with allopurinol (Dastgheib 2012). Thus, azithromycin needs further investigation for human leishmaniasis.

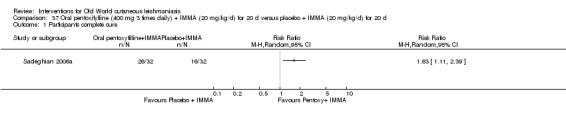

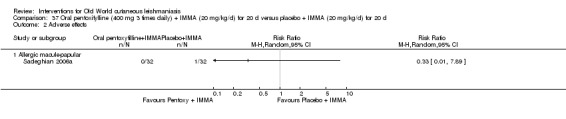

Oral pentoxifylline

Oral pentoxifylline, used in people with vascular diseases, also has anti‐Leishmania effects (Lessa 2001), decreasing the inflammatory reaction and the resulting tissue damage (Sadeghian 2006a). Pentoxifylline has a good safety profile, although nausea, arthralgias, dizziness, abdominal pain, and diarrhoea can occur (Lessa 2001).

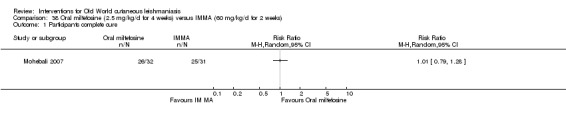

Oral miltefosine

Oral miltefosine, which was originally developed as an anticancer drug, is active against the Leishmania membrane (Croft 2006). Miltefosine was included in the WHO essential medicines list as an anti‐leishmaniasis medicine in March 2011 (WHO 2011), and in March 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved oral miltefosine for visceral, cutaneous, and mucosal leishmaniasis (FDA 2014). Miltefosine seems active against most Leishmania species, but with variable efficacy depending on geographical regions, even for the same species (Monge‐Maillo 2015; Soto 2004; Stojkovic 2007). Limited experience with miltefosine for OWCL shows efficacy, mostly against L major (Dorlo 2011; Mohebali 2007; Stojkovic 2007). The most commonly reported adverse drug reactions associated with miltefosine are transient gastrointestinal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and mild elevation of liver enzymes and serum creatinine (Mohebali 2007). Women of childbearing age require contraception beyond the end of treatment because this drug is contraindicated during pregnancy (Sindermann 2006).

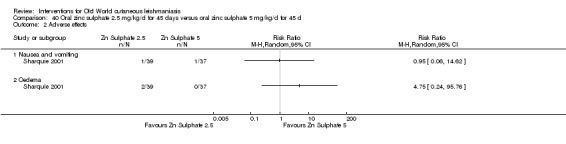

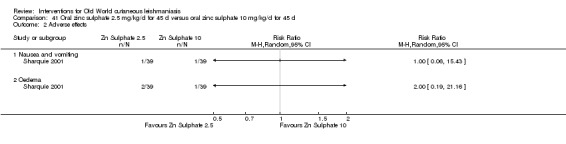

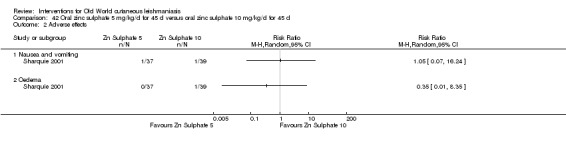

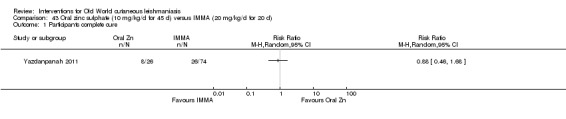

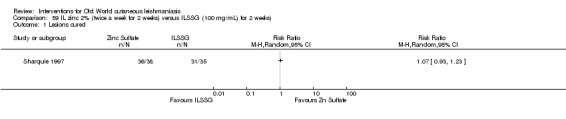

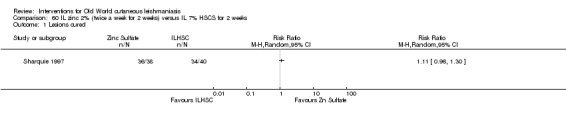

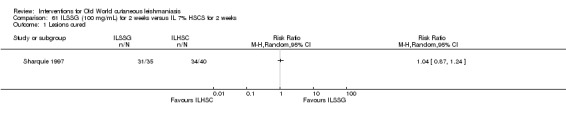

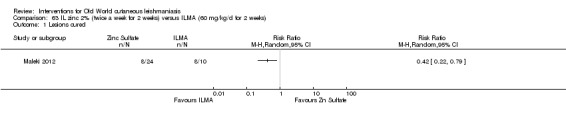

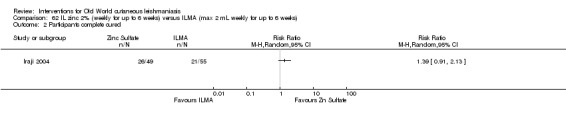

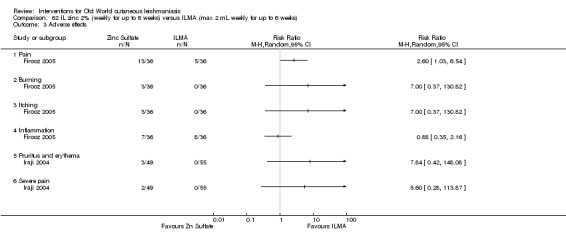

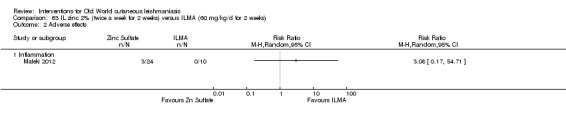

Oral zinc sulphate

Early studies on oral zinc sulphate reported promising results for the treatment of CL (Sharquie 1996; Sharquie 1997; Sharquie 2001), although more recent studies have not reported good cure rates (Yazdanpanah 2011).

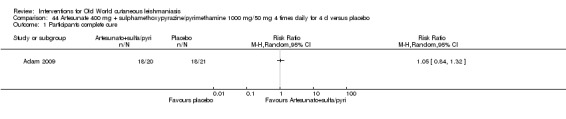

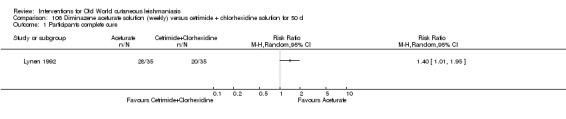

Oral artesunate

Artemisinin is effective against promastigotes in vitro, and artemisinin and artemether are leishmanicidal for amastigotes in infected murine macrophages (Adam 2008; Keiser J 2007). However, an RCT performed in Sudan did not show that artesunate combined with sulphamethoxypyrazine/pyrimethamine was better than placebo for OWCL (Adam 2009).

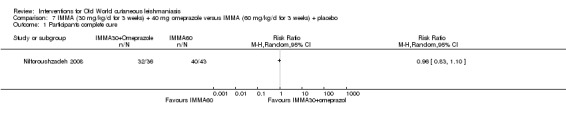

Other oral drugs

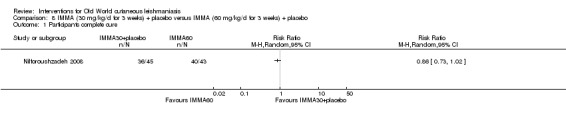

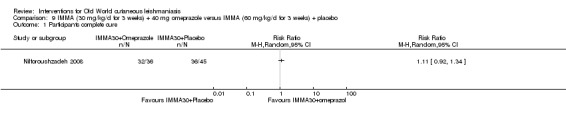

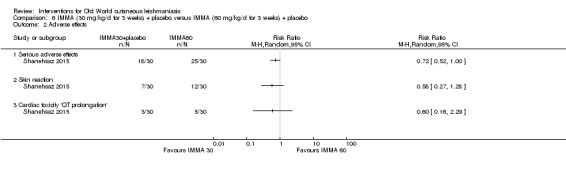

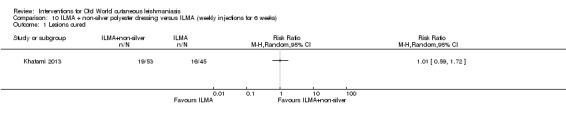

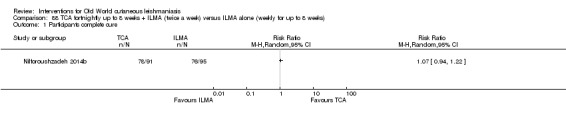

Jiang 2002 was the first to describe using omeprazole, a common treatment for peptic ulcer diseases, as a potential antiparasitic drug for the growth of L donovani in a laboratory setting, and Nilforoushzadeh 2008 concluded it was a good alternative to antimonials when these have to be given in a lower dose.

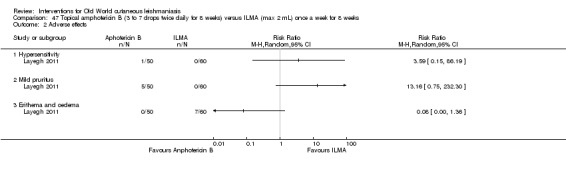

Parenteral liposomal amphotericin B

Amphotericin B, an antifungal drug used since 1960 (Sampaio 1960), is commonly used for treating American mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, HIV co‐infection, and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in areas where Leishmania is resistant to antimonial and pentamidine drugs (Karamian 2007; Laguna 1999; Musa 2005; Sampaio 1997; Sundar 2007a; Thakur 1996). There has been little experience with this drug for OWCL due to pentavalent antimonials' dominance as the most commonly systemic regimens until now. However, the toxicity of pentavalent antimonials has prompted an increase in the administration of amphotericin B (mostly the lipid formulations), with promising results mainly with L major and L tropica (Solomon 2011; Wortmann 2010). Zanger 2011 also reported a case of OWCL due to L aethiopica in a immunosuppressed person with response to liposomal amphotericin B.

Non‐antimonial topical or intralesional therapies

Mild disease caused by L major is often self‐healing (Alkhawajah 1997; Nilforoushzadeh 2006). OWCL can be managed with local care alone and may not require other specific therapies when it is a simple CL (Shazad 2005), defined as CL: not caused by Leishmania species with common mucosal dissemination; not a diffuse, recurrent or post‐kala‐azar CL; with no lymphatic nodes affected; with small lesions; with fewer than five lesions; with lesions that are not localised in joints or aesthetic areas; or in people who are not immunocompromised (Nilforoushzadeh 2006). Topical and local therapies are attractive options that are appropriate for early self‐limiting lesions, offering reduced systemic toxicity and possibilities for outpatient treatment (Iraji 2004).

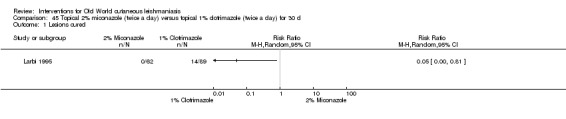

Topical antifungals

Early research on topical antifungals was based on clotrimazole, miconazole, and ketoconazole. The only RCT performed was in Saudi Arabia; investigators compared clotrimazole and miconazole and concluded that clotrimazole was more effective (Larbi 1995). Topical ketoconazole was tested in Afghanistan, but it did not significantly change the course of the lesions (Storer 2005).

Topical paromomycin (aminosidine)

Topical formulations often offer easier administration, fewer adverse effects, and sometimes cost‐effectiveness, although there may be difficulties in getting enough of the active drug absorbed through the skin (Jowkar 2012). Paromomycin is an antibiotic in the aminoglycoside family, originally identified as an anti‐Leishmania drug in the 1960s. Parenteral formulations have been used for VL (Sundar 2007b), and topical preparations for CL since 1987 (Asilian 1995). The literature uses the names paromomycin, aminosidine, monomycin, and neomycin E interchangeably, although the active principle is the same (Bryceson 1994). Two main topical preparations are available for CL: 15% paromomycin sulphate dissolved in a soft white paraffin base, either with 12% methyl benzethonium chloride (MBCL) or with 10% urea (Faghihi 2003; Shazad 2005). Paromomycin ointment combined with MBCL has been shown to be more efficacious than with urea (Iraji 2005). The original paromomycin formulation is no longer used because of its toxicity, and newer penetration‐enhancing formulations have been subjected to clinical evaluation (Davis 2003). More recently, studies have also evaluated new combinations of paromomycin plus gentamycin (Ben Salah 2009). Of the topical preparations, paromomycin ointment is commonly the first‐line treatment in uncomplicated CL (Asilian 2006). Adverse effects encountered were redness, pruritus, burning, oedema, local pain, inflammation, contact dermatitis, urticaria, or lymphadenitis with pain (Ben Salah 2013).

Intralesional zinc sulphate

Intralesional zinc sulphate had a direct anti‐Leishmania effect against L major and L tropica species in both an in vitro and in vivo study (Firooz 2005; Najim 1998).

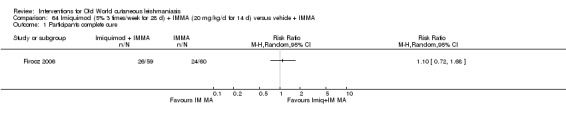

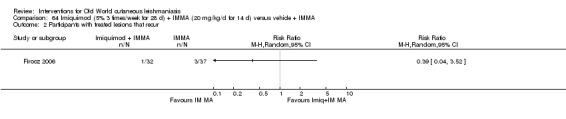

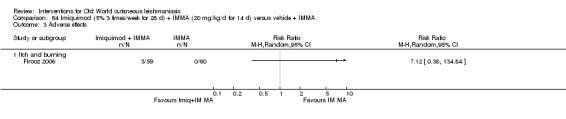

Topical imiquimod

Topical imiquimod is an immune response modifier used for treating genital warts and premalignant skin cancer conditions, first used in combination with antimony for American CL (Arevalo 2007).

Intralesional hypertonic sodium chloride

Intralesional hypertonic sodium chloride solution (HSCS) can act by its osmotic effect to destroy the parasite as well as the surrounding tissue of the granuloma (Sharquie 1995; Sharquie 1997). It appears to be a cheap, safe, and effective local method for treating CL.

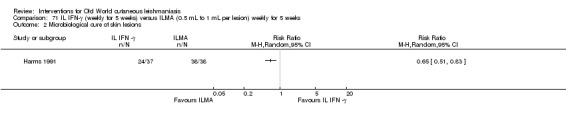

Intralesional interferon‐gamma (IFN‐γ)

Intralesional interferon (IFN‐ɣ) is a lymphokine originally used for the treatment of leprosy, cancer, HIV, and chronic granulomatous disease, and it has been shown to enhance the leishmanicidal capacity of human monocytes in vitro (Badaro 1990; Passwell 1986).

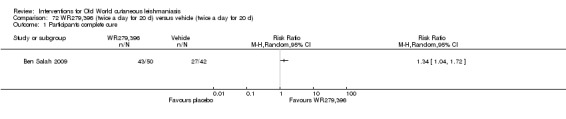

Topical aminoglycoside ointment (WR279,396)

The topical aminoglycoside ointment (WR279,396) is a hydrophilic formulation of paromomycin 15% plus a second aminoglycoside (gentamicin 0.5%) that was developed for topical administration, avoiding the potential skin irritation of other combinations performed with MBCL. Researchers in Tunisia have studied this combination of ointment (WR279,396) for L major, with better results than vehicle (Ben Salah 2009).

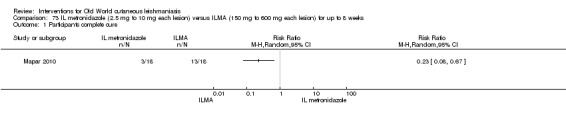

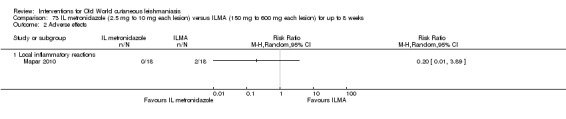

Intralesional metronidazole

Metronidazole was initially the first line treatment for trichomoniasis and later for amoebiasis and giardiasis. Its effectiveness for cutaneous leishmaniasis is controversial. Several case reports and a clinical trial performed in Iraq showed good cure rates for OWCL with intralesional metronidazole (Al‐Waiz 2004). However, a more recent clinical trial performed in Iran showed that metronidazole is ineffective (Mapar 2010). Moreover intralesional metronidazole injection was very painful.

Topical miltefosine

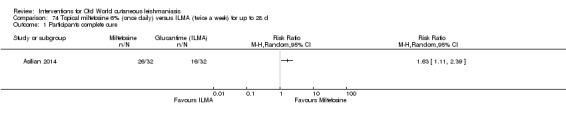

Pre‐clinical animal studies initially evaluated topical miltefosine, showing a potential benefit for NWCL and OWCL (Schmidt‐Ott 1999). A trial in Syria did not demonstrate efficacy of topical miltefosine for OWCL (Garnier 2002). However, a recent RCT in Iran showed that topical miltefosine was significantly more efficacious than meglumine antimoniate (Asilian 2014).

Topical dapsone

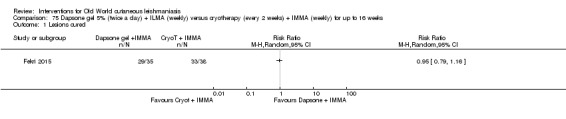

Dapsone is a synthetic sulfone employed orally for infectious diseases such as leprosy and for certain cutaneous disorders such as nodulocystic acne. However, the potential for systemic toxicity has limited its use in many cases. Topical formulations have also been developed especially for acne, thus reducing the possible systemic secondary effects (Stotland 2009). For OWCL an RCT in Iran compared dapsone 5% gel mask plus intralesional meglumine antimoniate (ILMA) versus cryotherapy plus ILMA, but investigators did not find any statistically significant difference in cure rates (Fekri 2015).

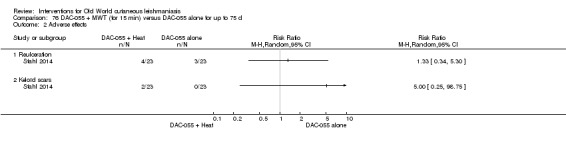

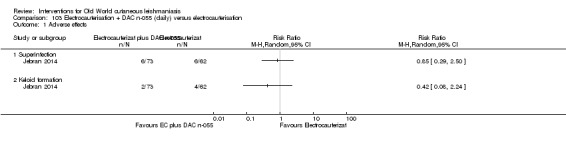

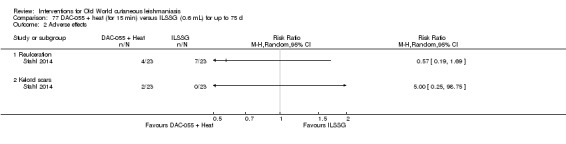

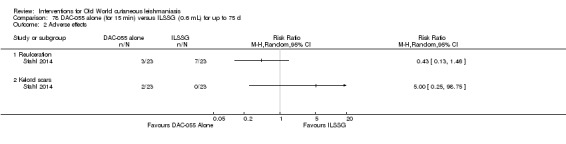

Topical 0.045% pharmaceutical chlorite (DAC N‐055)

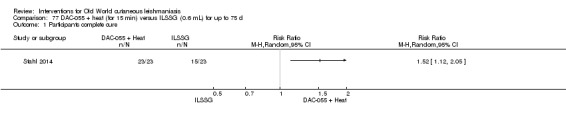

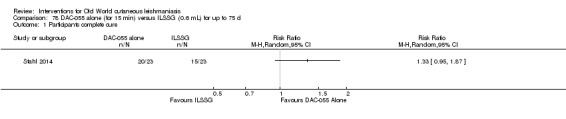

DAC N‐055 seems to promote tissue regeneration, which may be of benefit for cutaneous lesions due to OWCL (Migdal 2011). A clinical trial in Afghanistan compared this treatment, both alone and in combination with bipolar high frequency electrocauterisation, versus intralesional antimonials (Stahl 2014). Use of electrocauterisation is based on the fact that physical wound debridement practised with bipolar high frequency electrosurgical cauterisation (HF‐EC) seems to speed up wound healing (Jebran 2014). The results of the RCT showed that DAC N‐055 alone was significantly more efficacious than ILMA (Stahl 2014).

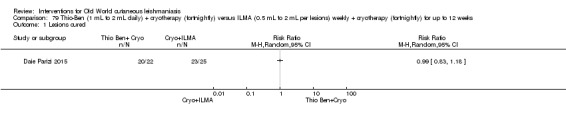

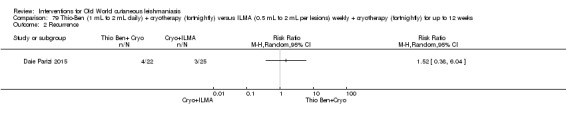

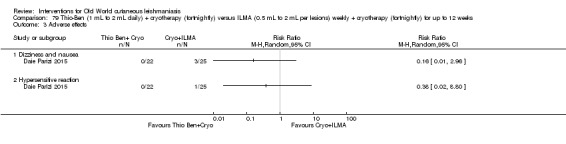

Topical Thio‐Ben

An Iranian study reported promising results in OWCL using topical thioxolone plus benzoxonium chloride, or Thio‐Ben (Daie Parizi 1992; Daie Parizi 1996). Thioxolone, which has long been topically administered for the treatment of acne and psoriasis, is recognised as a safe drug. A later RCT from Iran compared topical Thio‐Ben plus cryotherapy versus meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) plus cryotherapy (Daie Parizi 2015), showing that topical Thio‐Ben plus cryotherapy had good efficacy for OWCL, with fewer side affects than ILMA.

Physical therapies

People with OWCL may receive a range of physical treatments, including vaporisation, cauterisation, freezing, surgical excision, and the application of local heat.

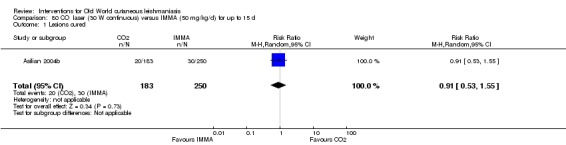

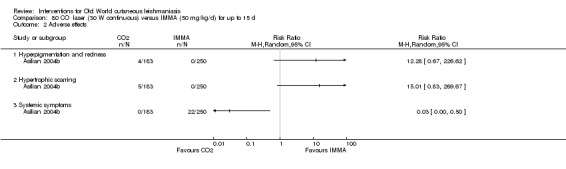

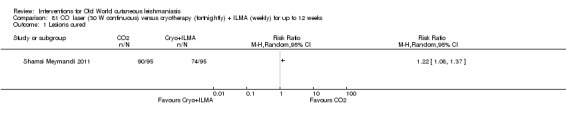

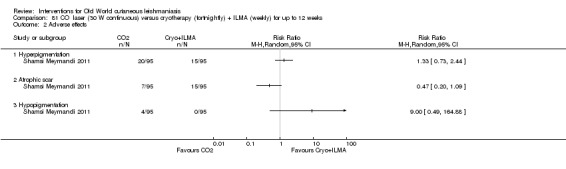

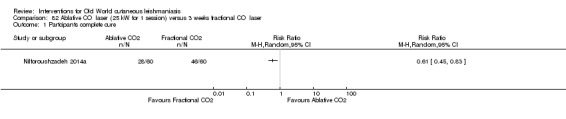

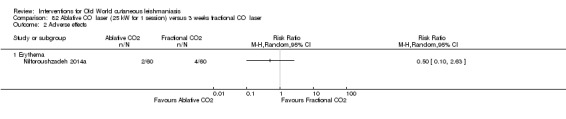

Laser

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) lasers have been used to vaporise CL lesions, thereby destroying affected tissue without significant side effects in normal tissue (Asilian 2004b). Studies have shown that a single session is enough, with lesions healing within three to four weeks, with quite admissible cosmetic results, although the procedure is painful and requires local anaesthetic (Shamsi Meymandi 2011).

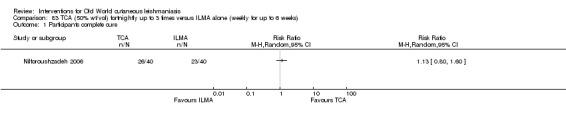

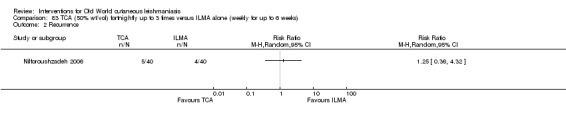

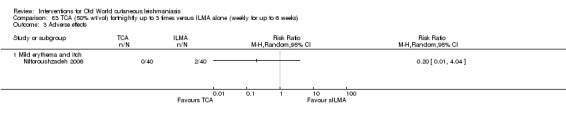

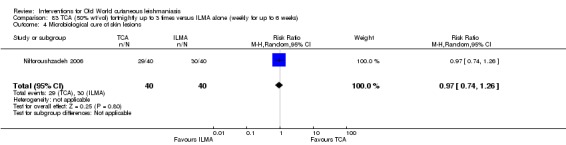

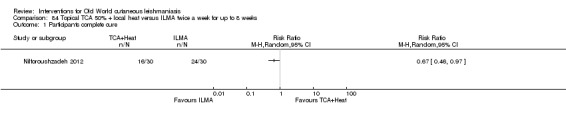

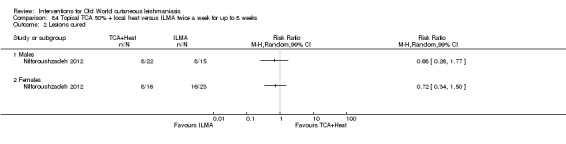

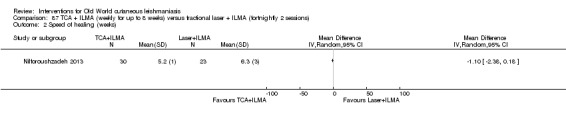

Trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

The efficacy of TCA for treating CL could be due to the destruction of infected tissue and skin regeneration (Nilforoushzadeh 2006).

Cryotherapy

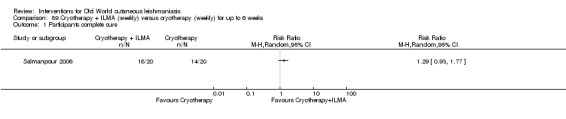

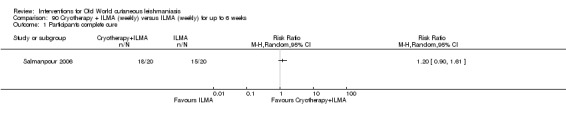

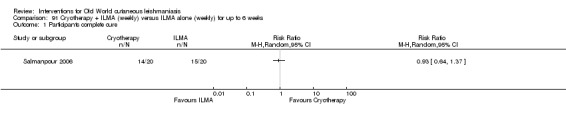

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen has been used to treat individual lesions, destroying infected tissue, but it is labour intensive (Layegh 2009). As an effective, painless, low‐cost technique with few side effects, it is an especially good option for children (Layegh 2009; Salmanpour 2006). However, it is not suitable for multiple or complicated lesions (Alrajhi 2003; Bassiouny 1982; Layegh 2009; Leibovici 1986; Minodier 2007; Mosleh 2008; Ranawaka 2011).

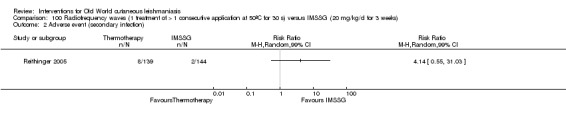

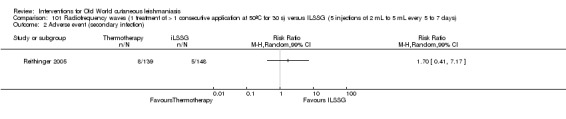

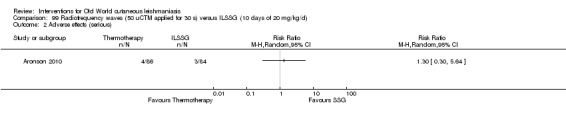

Thermotherapy

Laboratory studies have reported that Leishmania parasites cannot multiply in macrophages when temperatures are greater than 39ºC (Berman 1981; Sacks 1983). These findings have stimulated investigations into the efficacy of thermotherapy for CL with direct‐current electrical stimulation (Sharquie 1998), ultrasound (Aram 1987), infrared light (Junaid 1986), hot‐water baths (Neva 1984), laser (Asilian 2004b; Babajev 1991; Meawad 1997; Rodriguez 1990), radiofrequency waves, and ThermoMed device (Reithinger 2005; Sadeghian 2007; Aronson 2010). The procedure is painful and may require local anaesthetic (Sadeghian 2007).

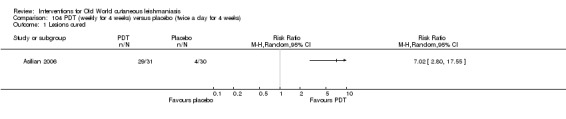

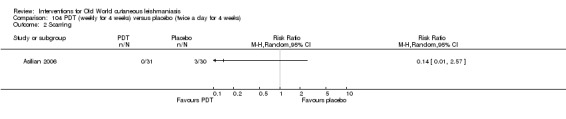

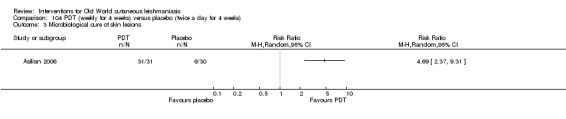

Topical photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a light‐mediated technique that causes cytolysis of Leishmania parasites, resulting in an effective and safe therapeutic option for OWCL (Asilian 2006).

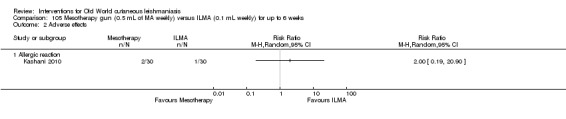

Mesotherapy

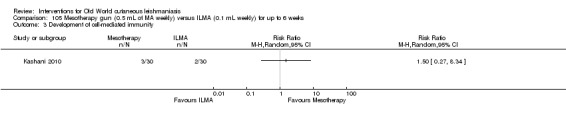

Mesotherapy is based on the use of a specific amount of variable substance (hormones, nutrients, enzymes, pharmaceuticals, and detergents, among others) and is not an invasive technique. People have received it for treating cellulite and acne scars, reducing aging skin, and rejuvenating the hands and neck (Amin 2006; Rohrich 2003). One RCT performed in Iran compared mesotherapy with ILMA, finding no difference in cure rates between the two therapeutic options (Kashani 2010).

Methods for promoting healing

Methods used in wound healing, including dressing and antiseptics, are often employed in ulcerative lesions of CL to accelerate cure, normalise epithelialisation, and reduce scarring, especially at cosmetic sites (Stahl 2014). Compromised wound healing due to repetitive trauma, contamination, and infection are major problems encountered in people with OWCL, and it is important to improve scar formation or at least not interfere with the natural healing process (Gonzalez 2008). A recent consensus panel on recommendations for chronic and acute wound dressings reported that "hydrocolloid (polymer dressings with medium absorption properties and containing carboxymethylcellulose) and low‐adherent dressings seem to be the most suitable dressings for the epithelialisation stage of chronic and acute wounds" (Vaneau 2007). The highest impact of scarring and ulcerative lesions is on the faces of young women, which exposes them to stigma and which may affect their marriage prospects (Weigel 2001; Reithinger 2005b). To assess the cosmetic impact, clinicians often use the Burn Scar Index (also known as the Vancouver Scar Scale) to document change in scar appearance (Baryza 1995), which should be ideally measured six months after completion of treatment (Modabber 2007).

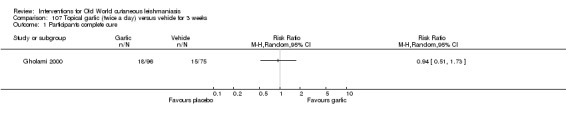

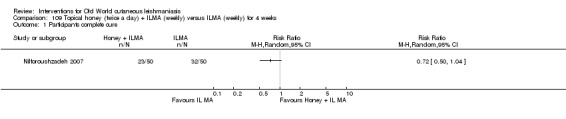

Alternative therapies

Increasing treatment failure with antimonial drugs has accelerated the search for alternative therapies (Nilforoushzadeh 2007). Up to 80% of the world's population may depend on medicinal plants as the only source of remedies for this disease; modern drugs may be either too expensive or wholly inaccessible (Fatima 2005). Practitioners of both traditional and modern medicine in Iran have long used herbal remedies and honey (Nilforoushzadeh 2007; Zerehsaz 1999). Different plants with medicinal value (Azadirachta indica, Acacia nilotica, and Allium sativa), traditionally used in the west and central parts of Sudan, have proven to have active anti‐Leishmania activity on L major promastigotes in vitro (Fatima 2005; Khalid 2005). Honey is effective for wound healing through enhancement of granulation and epithelialisation stages, enhancement of debridement, and downsizing of wound malodour (Moore 2001; Pieper 2003). Studies have described that honey from flowers in Australia and New Zealand has antibacterial effects (Pieper 2003).

How the intervention might work

OWCL is a heterogeneous group of diseases that differ in their clinical presentation, prognosis, and response to different the therapeutic interventions. There are two main factors affecting response to treatment: the species of Leishmania and the clinical form of the disease.

The mechanisms of action of the different therapeutic options for OWCL are diverse and may act over different targets, which can result in a complementary effect when working in combination (González 2009). There are two main types of therapeutic options: local physical therapies and local or systemic pharmacological therapies (Gonzalez 2008). Physical therapies such as HSCS, CO₂ lasers, TCA, cryotherapy, thermotherapy, and photodynamic therapy can destroy the parasite, the infected tissues, and the locally formed granulomas (González 2009). Pharmacological therapies, such as pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B and its lipid formulations, miltefosine, paromomycin, and pentamidine, seem to enter the host cells and act against amastigotes, compromising the parasite metabolism, altering the parasite membrane fluidity or damaging the parasite mitochondria, among other mechanisms of action (Gonzalez 2008).

Therapeutic interventions could work in several ways: healing the forms of disease that would run a chronic course without treatment (L aethiopica); avoiding the progression of the disease to more complex clinical forms (mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, leishmaniasis recidivans, etc.); speeding the healing of those forms that would naturally cure (L major); avoiding sequelae and disfiguring residual lesions (L major, L tropica, L infantum); and decreasing the human reservoir in anthroponotic forms (L tropica).

As a wide range of interventions are available, from physical or pharmacological local therapy to parenteral treatment, and response to treatment varies depending on the Leishmania species, knowing the optimal therapeutic approach in each situation is of great interest. This review aims to analyse the different interventions in order to provide the best treatment options for OWCL.

Why it is important to do this review

Controlling CL currently depends on early detection and rapid treatment (González 2009). The mainstays of treatment have been pentavalent antimonials, but other oral and topical treatment alternatives have become available in recent years (Gonzalez 2008). Global health development policies have mainly focused on innovative research to develop effective and affordable tools to tackle neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and provide necessary new knowledge (WHO 2010). WHO is now prioritising the delivery of drugs that are currently available and using existing resources to reduce mortality, morbidity, and disability as a result of NTDs in low‐income countries (Savioli 2006). However, evidence for the comparative effectiveness, cost‐effectiveness, and safety of different treatment strategies is needed to improve disease control.

This systematic review focused on addressing the effects of treatments for the localised form of CL due to L tropica and L major, which account for more than 90% of CL in the Old World (WHO 2010). Since the overwhelming majority of OWCL cases heal spontaneously within 3 to 18 months (Blum 2014), the rationale for using systemic and topical treatments needs to be well established and preferably stratified for different geographic regions and Leishmania species. Separate Cochrane Reviews have addressed treatments for American CL and prevention measures for all types of cutaneous and mucosal leishmaniasis (González 2009; González 2015).

The protocol of this review was first entitled 'Interventions for solitary or limited cutaneous leishmaniasis'. However, we split the clinical subject into two reviews. We amended the title of the present review, first published in 2008 (Gonzalez 2008), to 'Interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis', and we also published a separate Cochrane Review, entitled 'Interventions for American cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis' (González 2009). Thus, some parts of the Background and Methods sections are common to both reviews.

Objectives

To assess the effects of therapeutic interventions for the localised form of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

All immunocompetent people who had localised OWCL confirmed by parasitological diagnostic methods (i.e. tissue smears, histology, culture or PCR).

Types of interventions

The interventions were either single therapy or combination therapy. The comparators were either no treatment, placebo/vehicle only, or another active compound.

1. Systemic and intralesional antimonials

1.1 Meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) 1.2 Sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam)

2. Non‐antimonial systemic treatments

2.1 Oral antifungals 2.2 Oral dapsone 2.3 Oral allopurinol 2.4 Oral antibiotics 2.5 Oral pentoxifylline 2.6 Oral miltefosine 2.7 Oral zinc sulphate 2.8 Oral artesunate

3. Non‐antimonial topical or intralesional therapies

3.1 Topical antifungals 3.2 Topical paromomycin (aminosidine) 3.3 Intralesional zinc sulphate 3.4 Topical imiquimod 3.5 Intralesional hypertonic sodium chloride (HSCS) 3.6 Intralesional interferon‐gamma (IFN‐γ) 3.7 Topical aminoglycoside ointment (WR279,396) 3.8 Intralesional metronidazole 3.9 Topical miltefosine 3.10 Topical dapsone 3.11 Topical 0.045% pharmaceutical chlorite (DAC N‐055) 3.12 Topical Thio‐Ben

4. Physical therapies

4.1 Laser 4.2 Trichloroacetic acid 4.3 Cryotherapy 4.4 Thermotherapy 4.5. Topical photodynamic therapy 4.6. Mesotherapy

5. Measures for promoting healing

6. Alternative therapies

Types of outcome measures

We did not limit the measurement of any outcomes based on length of follow‐up.

Primary outcomes

Percentage of lesions cured after the end of treatment

Percentage of participants with a complete cure after the end of treatment

By cured, we meant that all inflammatory signs disappeared (either skin oedema, hardening, or both) and that complete scarring or healthy repair occurred in ulcerative lesions. We did not consider lesions to be healed if there was no re‐epithelialised skin, or if inflammatory signs remained after follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

Speed of healing (time taken to be 'cured')

Duration of remission and percentage of people with treated lesions that recur within six months, one year, two years, and three years

Degree of functional and aesthetic impairment

Prevention of scarring

Quality of life

Adverse effects

Tertiary outcomes

Change in ability to detect Leishmania by parasitological diagnostic methods (e.g. smear, PCR, or culture)

"Emergence of treatment failures (defined as a decline in the efficacy of a drug against a population of parasites previously susceptible to that compound. The definition assumes that the original susceptibility of the population is known, which is not always the case for Leishmania)" (Ponte‐Sucre 2003)

Microbiological or histopathological cure of skin lesions

Development of cell‐mediated immunity (i.e. positive leishmanin skin test)

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

For this update, we revised all our search strategies in line with current Cochrane Skin practices. Details of the previous search strategies are available in Gonzalez 2008.

We searched the following databases up to 17 November 2016:

Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, using the search strategy in Appendix 1.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2016, Issue 10) in the Cochrane Library, using the strategy in Appendix 2.

MEDLINE via Ovid (from 1946), using the strategy in Appendix 3

Embase via Ovid (from 1974) using the strategy in Appendix 4.

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database, from 1982) using the strategy in Appendix 5.

Trials registers

We searched the following trials registers in October 2015 using the term 'cutaneous leishmaniasis'.

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com).

ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (www.anzctr.org.au).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

EU Clinical Trials Register (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu).

Searching other resources

References from unpublished studies

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and key papers identified by our searches for further references to relevant trials.

Unpublished literature

We wrote to national programme managers, general coordinators, directors, clinicians, regional officers from endemic countries in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, pharmaceutical companies, and relevant authors for further information about unpublished and ongoing trials. We also contacted the following tropical medicine centres.

Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine at the University of Munich, Germany.

Swiss Tropical Institute, Switzerland; Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Belgium.

McGill Centre for Tropical Disease, Canada.

Tulane University School of Public Health & Tropical Medicine, USA.

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK.

Tropical Medicine at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK.

Department of Public Health and Tropical Medicine James Cook, University of North Queensland, Australia.

Institut Pasteur, France.

Bernhard Nocht Institute, Germany.

TropEdEurop, Spain.

Adverse effects

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid) from 1946 to 30 September 2015 for adverse or side effects of interventions for Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis using the search strategy in Appendix 6.

Data collection and analysis

Some parts of this review use text that was originally published in other Cochrane Reviews (predominantly van Zuuren 2015, Ingram 2015, and Delamere 2008; the latter was an exemplar Cochrane Review at the time the original review was written).

Selection of studies

We checked the titles and abstracts identified from the searches by at least two authors (JHM, PC, PLP, BMM, EGM). If it was unclear, then two authors obtained the full text study for independent assessment (BMM, EGM). The authors decided which trials met the inclusion criteria. The authors resolved any disagreements by discussion, with referral to a third author (AR) if necessary. We describe excluded studies and reasons for exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

At least two independent authors (MP, LR, JHM, PLP) carried out data extraction using a pre‐designed data extraction form. We extracted data for all outcomes for all relevant drugs, paying attention particularly to the doses and therapy frequencies. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We obtained the missing data from trial authors when possible.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality assessment included an evaluation of the following components for each included study, since there is some evidence that these are associated with biased estimates of treatment effect (Higgins 2011).

The method for generating the randomisation sequence.

The method for concealing allocation – it was considered 'adequate' if personnel and participants could not have foreseen assignment.

Blinding (participants, clinicians, outcome assessors).

Loss to follow‐up in each arm (split into postrandomisation exclusions and later losses if possible), and whether participants were analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomised (intention‐to‐treat).

In addition, the quality assessment also included the following.

Declaration of sample size calculation.

Definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Reporting of Leishmania species involved.

Time of follow‐up.

Baseline comparability of severity of infection, age, sex, and duration of complaint.

Conflict of interest.

We assessed these other risks of bias. When trials reported two or more incorrectly, we judged them to be at high risk. When trials reported only one incorrectly, we judged them to be at unclear risk. We recorded the information in 'Risk of bias' tables (Characteristics of included studies) and described the quality of each study based on these components.

Measures of treatment effect

We reported all outcome data with their associated 95% confidence interval (CI). We expressed results as risk ratios (RR) and 95% CIs for dichotomous outcomes. We presented continuous outcomes with the same scale as reported in each trial, with a mean change from baseline with its associated standard deviation (SD), or as weighted mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) if more than one study was available.

If enough information was available in the study reports, we decided to describe hazard ratios (HR) for time‐to‐event outcome data.

Unit of analysis issues

We found that most RCTs included in this review assessed participants instead of lesions as the unit of analysis. When lesions were used as unit of analysis, comparisons were performed with lesions cured over lesions at start, not taking into account the correlation of multiple lesions per participant. We only pooled together studies which reported number of participants cured (not number of lesions), due to unit of analysis issues.

The approach followed to 3‐arm trials, was comparing the arms in pairs (A vs B, B vs C, and A vs C).

We only considered parallel group designs for all clinical trials. We did not consider cross‐over trials in this review because they are an inappropriate design for treatments that can potentially cure an infectious disease. We did not find any particular additional important information in the specific search for adverse effects for every particular treatment. Authors described these qualitatively in the Results and Discussion sections.

Dealing with missing data

For all missing data from trials that were less than 10 years old, we tried to contact the authors. Only six of the trials explicitly stated intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. Where an ITT was not stated, we used the numbers originally randomised to the groups in order to calculate effect estimates.

For each study, we took all participants that were randomised into account when introducing the data in our tables. We sent emails to study authors asking for more information, and we recorded these emails and their responses. When we had no response, we assumed that missing data were treatment failures. Concerning the losses to follow‐up, it was not always possible to determine the arm in which the losses occurred, making ITT analyses impossible. In that case, we introduced only available data into the tables for analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To assess the consistency of the study results, we obtained the I² statistic, which measures the proportion of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance. I² lies between 0% and 100%. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and larger values show increasing heterogeneity. We analysed statistical heterogeneity using a Chi² test (on 1 degree of freedom, with a significance level of 0.05) (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

In this review, the low number of studies evaluating similar interventions and comparisons did not permit an assessment of publication bias. In future updates, if a sufficient number of trials assessing similar effects are identified for inclusion in this review, publication bias will be assessed according to the recommendations on testing for funnel plot asymmetry (Egger 1997) as described in section 10.4.3.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If asymmetry is identified we will try to assess other possible causes and these will be explored in the discussion if appropriate

Data synthesis

We performed data synthesis only when we were able to identify at least two studies investigating similar treatments and reporting data amenable to pooling. Although there is inevitably a degree of heterogeneity between the studies included in a review, we entered these into a meta‐analysis if clinical reasoning could explain the heterogeneity and if there was a coherent argument for combining the studies. We used the random‐effects model, as this is more conservative in the presence of heterogeneity.

The percentage of lesions cured after the end of treatment was the primary outcome measure if available. If this were not available, we used secondary and tertiary outcomes. To estimate differences between treatments, we pooled trials that evaluated similar interventions and controls and calculated a weighted treatment effect across trials, using a random‐effects model. Where it was not possible to perform a meta‐analysis, we summarised the data for each trial.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In view of the limited number of included studies covering any one specific intervention, we did not conduct any of the subgroup analyses that we originally planned: Leishmania species, location and severity of infection, geographical setting, diagnostic techniques, type of treatment (topical, systemic, or combination), and relapse or re‐infection.

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining the characteristics of the studies, the similarity between the types of participants, the interventions, the comparisons, and the outcomes as specified in the criteria for included studies.

Sensitivity analysis

We plan to carry out a sensitivity analysis by excluding studies at high risk of bias.

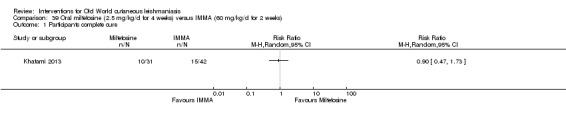

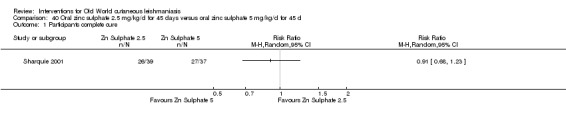

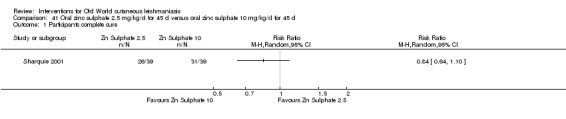

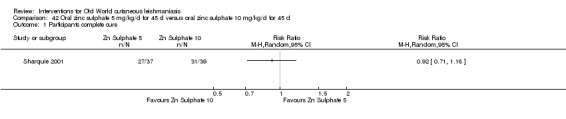

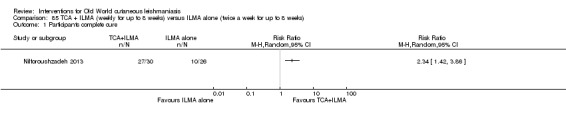

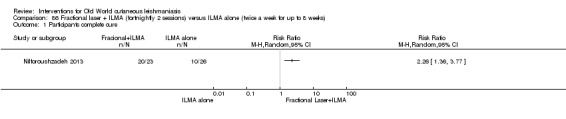

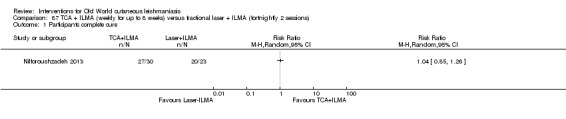

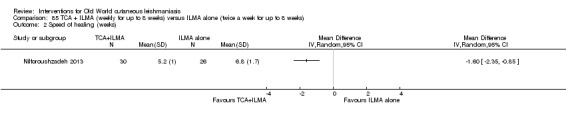

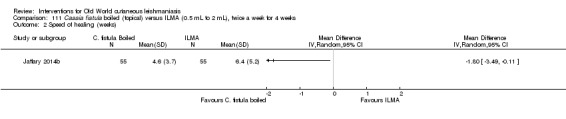

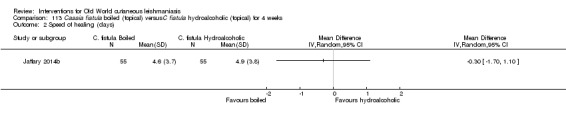

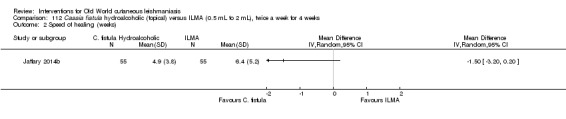

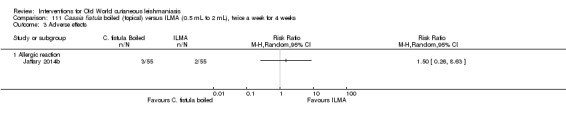

Summary of findings tables