Abstract

Background

Several treatment options are available for stress urinary incontinence (SUI), including pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), drug therapy and surgery. Problems exist such as adherence to PFMT regimens, side effects linked to drug therapy and the risks associated with surgery. We have evaluated an alternative treatment, electrical stimulation (ES) with non‐implanted devices, which aims to improve pelvic floor muscle function to reduce involuntary urine loss.

Objectives

To assess the effects of electrical stimulation with non‐implanted devices, alone or in combination with other treatment, for managing stress urinary incontinence or stress‐predominant mixed urinary incontinence in women. Among the outcomes examined were costs and cost‐effectiveness.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register, which contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and handsearches of journals and conference proceedings (searched 27 February 2017). We also searched the reference lists of relevant articles and undertook separate searches to identify studies examining economic data.

Selection criteria

We included randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials of ES with non‐implanted devices compared with any other treatment for SUI in women. Eligible trials included adult women with SUI or stress‐predominant mixed urinary incontinence (MUI). We excluded studies of women with urgency‐predominant MUI, urgency urinary incontinence only, or incontinence associated with a neurologic condition. We would have included economic evaluations had they been conducted alongside eligible trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened search results, extracted data from eligible trials and assessed risk of bias, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. We would have performed economic evaluations using the approach recommended by Cochrane Economic Methods.

Main results

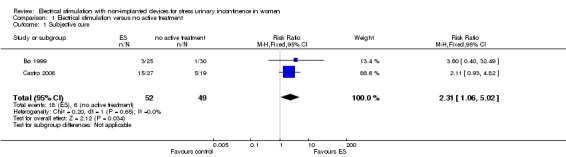

We identified 56 eligible trials (3781 randomised participants). Eighteen trials did not report the primary outcomes of subjective cure, improvement of SUI or incontinence‐specific quality of life (QoL). The risk of bias was generally unclear, as most trials provided little detail when reporting their methods. We assessed 25% of the included trials as being at high risk of bias for a variety of reasons, including industry funding and baseline differences between groups. We did not identify any economic evaluations.

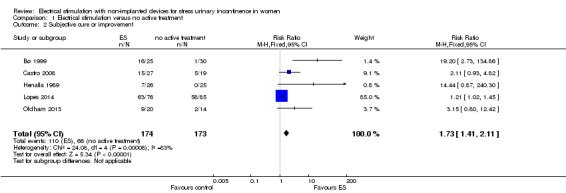

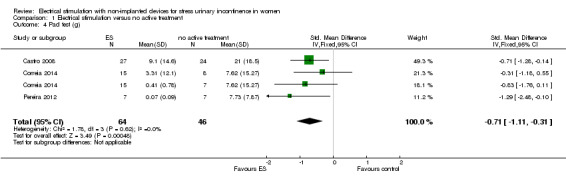

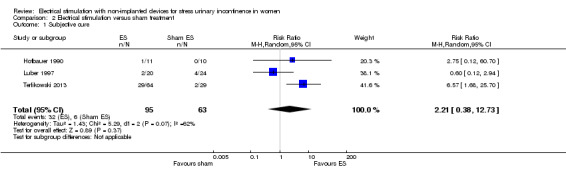

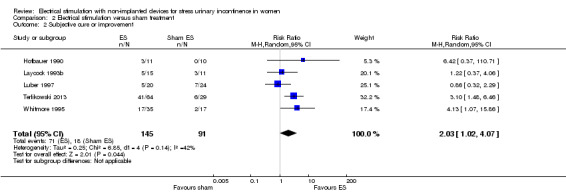

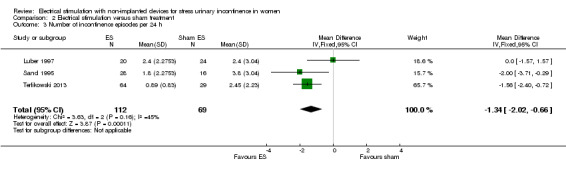

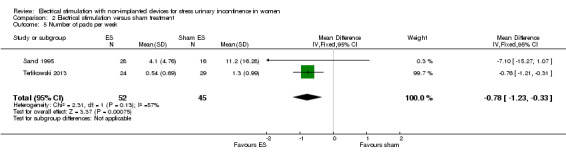

For subjective cure of SUI, we found moderate‐quality evidence that ES is probably better than no active treatment (risk ratio (RR) 2.31, 95% CI 1.06 to 5.02). We found a similar result for cure or improvement of SUI (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.41 to 2.11), but the quality of evidence was lower. We are very uncertain if there is a difference between ES and sham treatment in terms of subjective cure because of the very low quality of evidence (RR 2.21, 95% CI 0.38 to 12.73). For subjective cure or improvement, ES may be better than sham treatment (RR 2.03, 95% CI 1.02 to 4.07). The effect estimate was 660/1000 women cured/improved with ES compared to 382/1000 with no active treatment (95% CI 538 to 805 women); and for sham treatment, 402/1000 women cured/improved with ES compared to 198/1000 with sham treatment (95% CI 202 to 805 women).

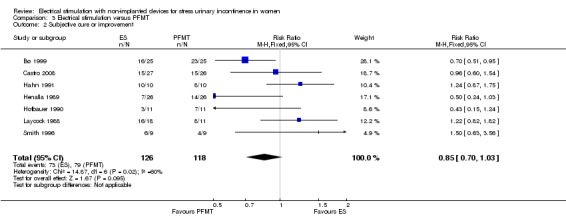

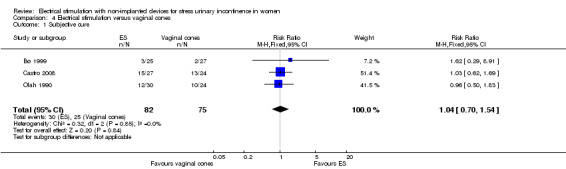

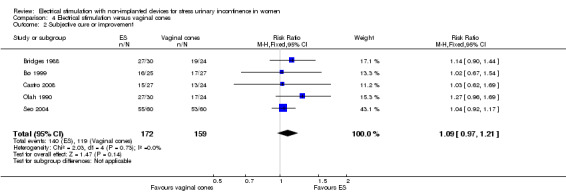

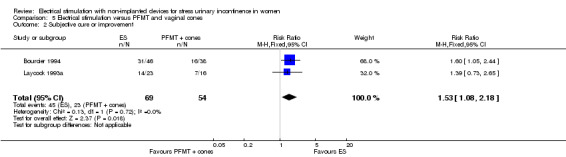

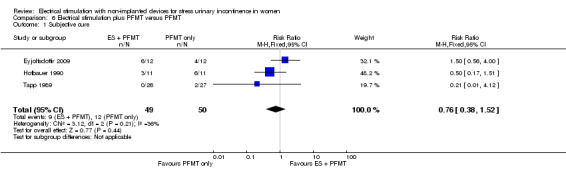

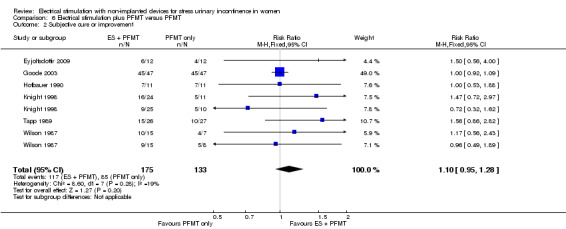

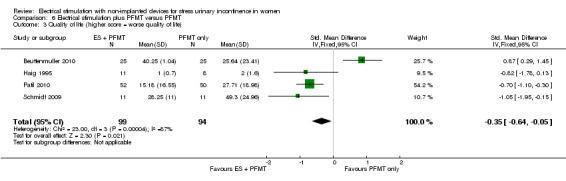

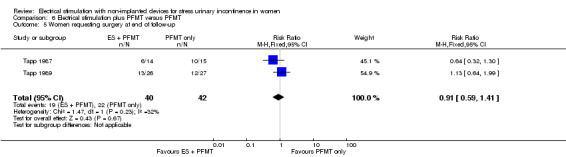

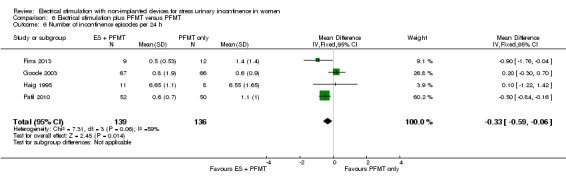

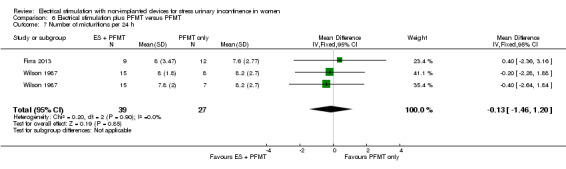

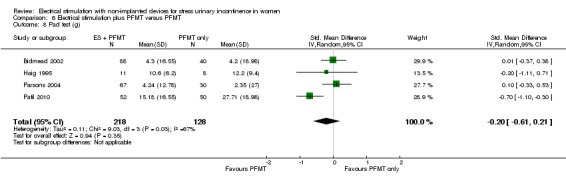

Low‐quality evidence suggests that there may be no difference in cure or improvement for ES versus PFMT (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.03), PFMT plus ES versus PFMT alone (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.28) or ES versus vaginal cones (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.97 to 1.21).

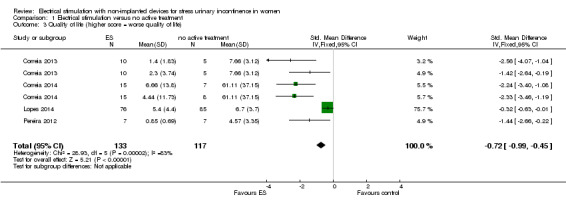

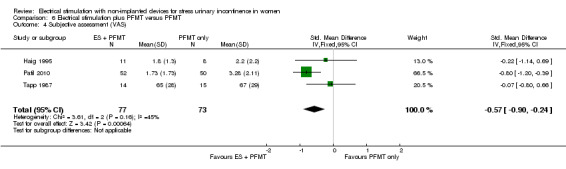

Electrical stimulation probably improves incontinence‐specific QoL compared to no treatment (moderate quality evidence) but there may be little or no difference between electrical stimulation and PFMT (low quality evidence). It is uncertain whether adding electrical stimulation to PFMT makes any difference in terms of quality of life, compared with PFMT alone (very low quality evidence). There may be little or no difference between electrical stimulation and vaginal cones in improving incontinence‐specific QoL (low quality evidence). The impact of electrical stimulation on subjective cure/improvement and incontinence‐specific QoL, compared with vaginal cones, PFMT plus vaginal cones, or drugs therapy, is uncertain (very low quality evidence).

In terms of subjective cure/improvement and incontinence‐specific QoL, the available evidence comparing ES versus drug therapy or PFMT plus vaginal cones was very low quality and inconclusive. Similarly, comparisons of different types of ES to each other and of ES plus surgery to surgery are also inconclusive in terms of subjective cure/improvement and incontinence‐specific QoL (very low‐quality evidence).

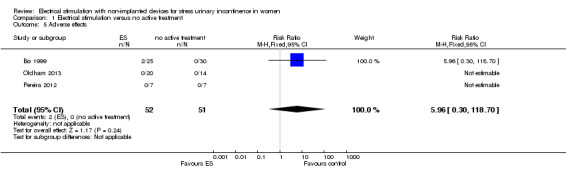

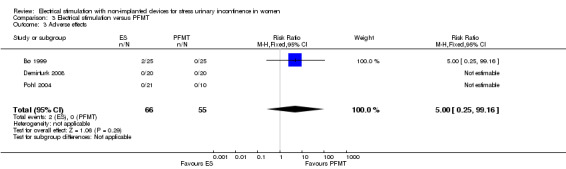

Adverse effects were rare: in total nine of the women treated with ES in the trials reported an adverse effect. We identified insufficient evidence to compare the risk of adverse effects in women treated with ES compared to any other treatment. We were unable to identify any economic data.

Authors' conclusions

The current evidence base indicated that electrical stimulation is probably more effective than no active or sham treatment, but it is not possible to say whether ES is similar to PFMT or other active treatments in effectiveness or not. Overall, the quality of the evidence was too low to provide reliable results. Without sufficiently powered trials measuring clinically important outcomes, such as subjective assessment of urinary incontinence, we cannot draw robust conclusions about the overall effectiveness or cost‐effectiveness of electrical stimulation for stress urinary incontinence in women.

Plain language summary

Non‐invasive electrical stimulation for stress urinary incontinence in women

Review question

We investigated whether electrical stimulation was better than no treatment at all or better than other available treatments for curing or improving stress urinary incontinence (SUI) symptoms in women. We also investigated whether SUI was cured or improved by adding electrical stimulation to other treatments, compared to other treatments and to different types of electrical stimulation. Finally, we investigated whether electrical stimulation represented value for money.

Background

About 25% to 45% of women worldwide have problems with leaking urine involuntarily. Women with SUI often leak urine with physical exertion such as coughing or sneezing. SUI can be treated with pelvic floor muscle exercises, vaginal cones, drug therapy or surgery, but there are various problems with these treatments. A possible alternative is electrical stimulation with non‐implanted devices, whereby an electrical current is delivered through vaginal electrodes.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to 27 February 2017.

Study characteristics

We found 56 trials (involving a total of 3781 women, all with stress urinary incontinence but some with urgency urinary incontinence as well) comparing electrical stimulation to no treatment or to any other available treatment.

Key results

For cure or improvement of SUI, electrical stimulation was probably better than no active or sham treatment. There was not enough evidence to say whether it was any better than pelvic floor muscle training for curing or improving SUI, or for quality of life. Adding electrical stimulation to pelvic floor muscle training may not make much difference to cure or improvement of SUI. It is uncertain whether it offers any improvement in quality of life compared with pelvic floor muscle training.

We found that few women reported adverse effects with electrical stimulation, but there was not enough reliable evidence comparing electrical stimulation to other treatments to know more about its safety.

There was not enough evidence comparing electrical stimulation to other existing treatments such as drug therapy, pelvic floor muscle training plus vaginal cones, surgery, or different forms of electrical stimulation, to provide evidence‐based guidance on which would be better, and for which women, in curing or improving SUI or in improving quality of life. There was no information from these studies to judge value for money.

Quality of the evidence

There is some evidence to support the use of electrical stimulation for stress urinary incontinence in women, but we are still very uncertain about the full potential of this treatment because of the low quality of the existing evidence. While we found evidence indicating that electrical stimulation may be better than no treatment, we did not find enough well‐designed trials with enough women to fully answer our review questions, so we do not yet know if ES is better or worse than other treatments.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Urinary incontinence (UI) affects 25% to 45% of women worldwide (ICI 2013). UI presents in the following forms.

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI): involuntary loss of urine through physical exertion or effort, coughing or sneezing.

Urgency urinary incontinence (UUI): involuntary loss of urine associated with a sudden and compelling desire (urgency) to urinate that is difficult to delay.

Mixed urinary incontinence (MUI): involuntary loss or urine associated with both stress and urgency.

Symptomatic diagnosis of SUI is typically based on whether urine leakage occurs with physical exertion or effort, as reported by women themselves.

In addition, urodynamically proven stress incontinence (USI) is diagnosed when an observer can see urine leakage on stress such as coughing during urodynamic examination, in the absence of a detrusor contraction (ICI 2013). Symptomatic diagnosis of MUI is based on self‐report of urine leakage through both physical exertion and urgency.

This review includes women with SUI, USI and stress‐predominant MUI.

Several mechanisms are thought to contribute to stress urinary incontinence.

Suboptimal pelvic floor muscle strength.

Hypermobility or significant displacement of the urethra and bladder neck during exertion.

Intrinsic urethral sphincter deficiency (ICI 2013).

In women, these mechanisms may coexist (Kursh 1994), but few clinical trials have distinguished between them as underlying causes. We will consider women whose incontinence may be due to any of these mechanisms together in this review.

Prevalence estimates of SUI range from 3% to 25% of adult women, with older women more likely to be affected (ICI 2013). Quality of life and sexual function are often substantially impaired by the fear of leakage, resulting in avoidance of social or physical activities which might cause it, embarrassment and poor sleep (Oh 2008). SUI can severely impact the ability to carry out daily activities, resulting in debilitating embarrassment, social isolation and considerably decreased health‐related quality of life (Bartoli 2010). Women with SUI may be less likely to participate in physical activity, which in turn has a detrimental impact on overall health because inactivity is a risk factor for many diseases (Bø 2004). Other evidence has shown that up to 50% of women with UI will avoid intimacy with their partners (Roos 2014).

Furthermore, SUI is associated with a considerable economic burden for women and for healthcare providers. For instance, routine care, such as sanitary pads, can entail considerable cost for each woman affected, while conservative treatment and surgery may cost the equivalent of several thousand GBP for each woman (ICI 2013).

Description of the intervention

In Europe and the USA, conservative interventions such as pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), with or without biofeedback, are recommended as first‐line treatment for SUI (EAU 2015; NICE 2013; Qaseem 2014); however, many women may find it difficult to adhere to these methods in the long‐term (Bø 2005; Dumoulin 2014).

Surgery is usually suggested as a second‐line option where conservative treatment has not improved a woman's symptoms or she is unwilling or unable to continue the treatment. Synthetic mid‐urethral tape, open or laparoscopic colposuspension and autologous rectus fascia sling procedures are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), although the use of surgery with tapes in the management of UI remains controversial in terms of safety and adverse effects (Scottish Government 2015). Several Cochrane Reviews have investigated the effects of surgical management for SUI (Dean 2017; Lapitan 2017; Nambiar 2017; Rehman 2011). Other older surgical procedures, such as anterior repair or bladder neck needle suspension, have generally fallen out of use due to lower effectiveness (Glazener 2017a; Glazener 2017b).

Other less invasive second‐line treatment options available in some countries include bulking agents, where a substance is injected into the urethral wall to increase its size and allow it to remain closed, or pharmacological therapy, typically with duloxetine. The disadvantages of these treatments are that they are likely to be less effective than surgery, and, in the case of drug therapy, long‐term adherence is usually necessary and is associated with unpleasant side effects (Alhasso 2005; Mariappan 2005). Bulking agents can cause discomfort or bleeding when urinating, and their effectiveness decreases over time, requiring retreatment. Other available treatments for SUI include artificial urinary sphincters and complementary therapies such as acupuncture.

Electrical stimulation (ES) has emerged as a first‐line alternative to PFMT in women who are unable to contract their pelvic floor muscles voluntarily or as a second‐line treatment if PFMT alone is not sufficiently effective. It may also be beneficial to combine ES with the use of vaginal cones and drug therapy.

How the intervention might work

When a nerve is stimulated, signals travel both toward the periphery and toward the central nervous system. Electrical stimulation may elicit responses to these signals, which may come from the central nervous system or the innervated tissues, or the central nervous system may be modified to reinterpret some signals (Chancellor 2002; Fall 1994).

With respect to lower urinary tract dysfunctions, electrical stimulation is applied particularly to the pelvic floor muscles, bladder and sacral nerve roots. In the context of SUI, the aim of ES is to improve pelvic floor muscle function so that the pelvic floor muscles can be used when needed to occlude (close) the urethra (such as before a cough) and to increase muscle bulk, which may help reduce urine loss by closing up the urethral walls.

Direct ES of the pelvic floor is intended to stimulate motor‐efferent fibres of the pudendal nerve, which may elicit a direct contraction of the pelvic floor muscles or the striated peri‐urethral musculature, supporting the intrinsic part of the urethral sphincter‐closing mechanism (Fall 1991; Scheepens 2003). As such, ES might contribute to compensating for a weak intrinsic sphincter, but it is questionable whether or not ES in such cases would be the first‐choice treatment option or would have any additional value to pelvic floor muscle training (Ayeleke 2015).

Different authors have suggested that ES may restore continence in women with SUI by:

strengthening the structural support of the urethra and the bladder neck by increasing muscle bulk (Plevnik 1991);

securing the resting and active closure of the proximal urethra (Erlandson 1977);

strengthening the pelvic floor muscles and hence their ability to close the urethra (Sand 1995);

inhibiting reflex bladder contractions (Berghmans 2002; Fall 1994);

modifying the vascularity (improving blood supply) of the urethral and bladder neck tissues (Fall 1991; Fall 1994; Plevnik 1991).

In the context of conservative or non‐surgical, non‐medical therapy, ES can be applied using surface electrodes in the form of transcutaneous or percutaneous ES. Transcutaneous ES is administered via suprapubic or vulval surface electrodes, or vaginal/anorectal plug electrodes. Percutaneous ES uses needle electrodes that penetrate the skin in conjunction with a surface electrode placed close to the needle to act as a reference electrode (e.g. posterior tibial nerve stimulation, percutaneous nerve evaluation). Percutaneous ES is normally used for women with overactive bladder symptoms, not SUI, so we exclude it from this review (see companion review of ES for overactive bladder; Stewart 2016a).

The frequency, dosage and duration of treatment with ES varies considerably. Although authors have claimed success for a wide range of parameters, there is no agreement on the optimal set of parameters for each type of urinary incontinence. Clinical consensus from the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) underlines this uncertainty:

"EStim is provided by clinic‐based mains powered machines or portable battery powered stimulators with a seemingly infinite combination of current types, waveforms, frequencies, intensities, electrode types and placements. Without a clear biological rationale it is difficult to make choices about different ways of delivering EStim. Additional confusion is created by the relatively rapid developments in the area of EStim, and a wide variety of stimulation devices and protocols have been developed even for the same condition" (ICI 2013).

Evidence from a systematic review has suggested that, in men, ES with non‐implanted devices may be more effective than sham treatment for urinary incontinence and that ES might enhance the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training in the short term (Berghmans 2013). Other evidence suggests that ES is more effective than sham, placebo or no active intervention for treating overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence, but the quality of evidence identified was generally low (Stewart 2016a). It is not yet clear whether ES has similar effects in women with SUI.

Why it is important to do this review

ES has shown promise in the treatment of UUI, but the evidence base for its use in SUI is inconclusive (Schreiner 2013). Given the adherence issues with conservative treatment, the side effects of drug therapy and the safety concerns regarding some kinds of surgical intervention, it is important to investigate alternative options for women with SUI.

Many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been undertaken investigating ES for SUI, compared to a variety of conservative interventions for SUI such as pelvic floor muscle exercises, drug therapy, vaginal cones, sham ES and no active treatment. Some trials have found no evidence of a difference in treatment effect, while others have found ES to be more effective than a comparator intervention. Given the heterogeneity of ES treatments, it is important to attempt to synthesise the available evidence relating to the diverse ES devices and protocols. Previous publications have synthesised some of the earlier evidence relating to ES for SUI (ICI 2013; Imamura 2010), but with a growing number of trials addressing this question, an up‐to‐date and comprehensive systematic review is needed to obtain the best possible estimate of the effectiveness of ES.

Objectives

To assess the effects of electrical stimulation with non‐implanted devices, alone or in combination with other treatment, for managing stress urinary incontinence or stress‐predominant mixed urinary incontinence in women. Among the outcomes evaluated are costs and cost‐effectiveness.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included parallel or cross‐over RCTs, quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment is by methods such as alternate medical records, date of birth, or other predictable methods) and cluster‐randomised trials.

To critically appraise and summarise current evidence on the cost effectiveness of ES, we included relevant health economics studies conducted alongside effectiveness studies that met the eligibility criteria for the effectiveness component of the review. This includes:

full economic evaluation studies of ES compared to other treatments (i.e. cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses, cost‐benefit analyses);

partial economic evaluations of ES (i.e. cost analyses, cost‐description studies, cost‐outcome descriptions);

RCTs reporting more limited information, such as estimates of resource use or costs associated with ES.

Types of participants

Eligible studies included adult women (18 years or older, or according to study authors' definitions of adult) with SUI or stress‐predominant MUI on the basis of symptoms, signs or urodynamic diagnosis. We used the trialists' definitions to classify women with SUI or stress‐predominant MUI.

We excluded studies in women with urgency‐predominant MUI, UUI only, or incontinence associated with a neurologic condition or frailty. We also excluded studies in men and women that did not report data separately by sex and studies including only men or children. We included trials of participants with MUI, UUI and SUI only if the data for women with SUI were presented separately. We included trials in women with MUI if the condition was SUI‐predominant.

Types of interventions

Eligible interventions included any method of delivering electrical stimulation with non‐implanted devices (see Table 12 and Characteristics of included studies for details of methods used). These devices could be placed in the vagina or anus or on a skin surface, but we excluded those that penetrated the skin or had to be placed surgically, which a different Cochrane Review covers (Herbison 2009). Health professionals or participants themselves could administer the treatment in any setting.

1. Description of electrical stimulation interventions.

| Study | Current | Current intensity | Pulse shape & duration | Frequency (Hz) | Duty cycle | Electrodes | Treatment duration/supervision |

| Aaronson 1995 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Intravaginal | Unclear |

| Abel 1997 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Alves 2011 | Unclear | Maximum tolerable intensity | Biphasic 2000 Hz 100 ms | 50 | 4 s on: 8 s off | Intravaginal | Twice a week for 6 weeks (12 sessions) |

| Biphasic 2000 Hz 700 ms | |||||||

| Bernardes 2000 | Unclear | 10‐30 mA up to maximum tolerable intensity | Symmetrical bidirectional 1 ms | 60 | 6 s on: 12 s off | Intravaginal | 20 min daily for 10 days (10 sessions) |

| Beuttenmuller 2010 | Unclear | Maximum tolerable intensity | 0.2‐0.5 ms | 50 | Rest time at least twice the time of current | Intravaginal | Two 20 min sessions per week for 6 weeks (12 sessions) |

| Bidmead 2002 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Bø 1999 | Unclear | 0‐120 mA up to maximum tolerable intensity | 0.2 ms | 50 | 0.5‐10 s on: 0‐30 s off, adapted on basis of ability to hold voluntary contraction | Intravaginal | 30 min daily |

| Bourcier 1994 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Twelve 30 min sessions over 6 weeks (20 min maximal ES, 10 min EMG/pressure biofeedback) |

| Bridges 1988 | Unclear | Maximum tolerable intensity | Unclear | 0‐100 | Unclear | Unclear | Three 15 min session per week for 4 weeks (12 sessions) |

| Brubaker 1997 | Bipolar | 0‐100 mA | Bipolar square wave 0.1 µs | 20 | 2 s on: 4 s off | Intravaginal | 20 min daily for 8 weeks (56 sessions) |

| Castro 2008 | Bipolar | 0‐100 mA up to maximum tolerable intensity | Bipolar square wave 0.5 milliseconds | 50 | 5 s on: 10 s off | Intravaginal | Three 20 min session per week under supervision of trained physical therapist |

| Correia 2013 | Unclear | Maximum tolerable intensity | 700 µs | 50 | Unclear | 4 surface electrodes: 2 in the suprapubic region and 2 medial to the ischial tuberosity | Two 20 min session per week for 3 weeks (6 sessions) |

| Intravaginal | |||||||

| Correia 2014 | Unclear | Maximum tolerable intensity | 700 µs | 50 | 4 s on: 8 s off | 4 surface electrodes: 2 in the suprapubic region and 2 medial to the ischial tuberosity | Two 20 min session per week for 6 weeks (12 sessions) |

| Intravaginal | |||||||

| Delneri 2000 | Unclear | "According to the patient's sensations" | Unclear | 15 min: 20 15 min: 50 |

4 s on: 8 s off | Unclear | 12 x 30 min sessions on consecutive days, excluding Saturdays and Sundays. |

| Demirturk 2008 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 0‐100 Hz | Unclear | 4 vacuum electrodes: 2 in the suprapubic region, 2 near to the medial side of the ischial tuberosity, crosswise | 3 x 15 min session per week for 5 weeks (15 sessions) |

| Edwards 2000 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Eyjolfsdottir 2009 | Unclear | Unclear | 200 µs | 50 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Firra 2013 | Unclear | Unclear current, intensity according to participant tolerance | Unclear | 12.5 | 5 s on: 10 s off | Intravaginal | 14 x 30 min sessions |

| Goode 2003 | Biphasic | According to participant tolerance, up to 100 mA | Biphasic, 1 millisecond | 20 | 1 s on: 1 s off1 | Intravaginal | Home use, 15 min every second day for 8 weeks |

| Hahn 1991 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 50 | Unclear | Intravaginal | Home use, 6‐8 hours per night for 12 months |

| Haig 1995 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 10‐40 | Intravaginal | 20 min sessions, treatment for 3 months (unclear how many sessions) | |

| Henalla 1989 | Unclear | According to participant tolerance | Unclear | 0‐100 | Unclear | Unclear | 1 x 20 min session per week for 10 weeks (10 sessions) |

| Hofbauer 1990 | Unclear | Intensity increased until participant felt a contraction | Unclear | Unclear | 10 ms on: 15 ms off | Unclear | 3 sessions per week for 6 weeks (18 sessions) |

| Huebner 2011 | Unclear | 20−80 mA | Unclear | 50 | 8 s on: 15 s off | Intravaginal | 2 x 15 min sessions per day for 12 weeks |

| Jeyaseelan 1999 | Unclear | Up to 90 mA | Balanced, asymmetrical biphasic pulse width 250 µs | Background low frequency (to target slow twitch fibres), and intermediate frequency with initial doublet (to target fast twitch fibres) | 10 s on: 50 s off | Intravaginal | Home use (portable device), 1 hour daily for 8 weeks (except when menstruating) |

| Jeyaseelan 2002 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 1 hour daily for 8 weeks (except when menstruating) |

| Jeyaseelan 2003 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | A range of frequencies in conjunction with a longer duty cycle than is traditionally used | Unclear | Unclear |

| Knight 1998 | Unclear | Low intensity, barely perceptible tingling sensation | Pulse width 200 ms | Preset frequencies of 10 Hz with bursts of 35 Hz to maintain fast twitch fibre activity | 5 s on: 5 s off | Intravaginal | Home use (3 hours per day) for 6 months, except during menstruation (overnight) |

| According to maximum participant tolerance | 35 | 16 x 30 min sessions in clinic | |||||

| Laycock 1988 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 2‐3 30 min sessions per week for 4‐6 weeks |

| Laycock 1993a | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | Three different frequencies: 10 min 1 Hz, 10 min 10‐40 Hz, 10 min 40 Hz | Unclear | Transcutaneous: one medium electrode placed over perineal body and a small electrode positioned immediately inferior to the symphasis pubis | 10 sessions; 1 x 15 min, 9 x 30 min |

| Laycock 1993b | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | Three different frequencies: 10 min 1 Hz, 10 min 10‐40 Hz, 10 min 40 Hz | Unclear | Transcutaneous: one medium electrode placed over perineal body and a small electrode positioned immediately inferior to the symphasis pubis | 10 sessions; 1 x 15 min, 9 x 30 min |

| Lo 2003 | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | 0‐100 | Unclear | Transcutaneous: 2 anterior flat electrodes placed over obturator foramen 1.5‐2 cm lateral to symphasis, 2 posterior electrodes placed medial to ischial tuberosities, either side of anus | One 15 min session, 11 x 30 min sessions. 3 sessions per week for 4 weeks (12 sessions) |

| Lopes 2014 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 3 x 30 min sessions per week at home |

| Luber 1997 | Unclear | 10−100 mA | 2 ms | 50 | 2 s on: 4 s off | Intravaginal | 2 x 15 min sessions per day for 12 weeks |

| Maher 2009 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | External electrodes | Home use, at least 4 x 30 min sessions per week for 8 weeks |

| Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Intravaginal | Home use, at least 4 x 30 min sessions per week for 8 weeks | |

| Min 2015 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Olah 1990 | Unclear | 0−100 mA, up to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Transcutaneous: 2 electrodes placed on abdomen and 2 on inner thighs | 3 x 15 min sessions per week for 4 weeks |

| Oldham 2013 | Unclear | Pre‐programmed to increase intensity over 24 s to reach therapeutic level and switch off automatically after 30 min. All devices same level of stimulation (average intensity considered comfortable and capable of producing contractions of pelvic floor muscles) | Unclear | During the 10 s 'on time' the device delivers 10 repeats of a short high intensity burst of 50 Hz stimulation immediately preceded by a doublet (125 Hz), superimposed on continuous low frequency 2 Hz stimulation | 10 s on: 10 s off | Intravaginal ‐ single use tampon‐like Pelviva device | One disposable device per day for 12 weeks except during menstruation |

| Parsons 2004 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Intravaginal | Home use |

| Patil 2010 | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | 0‐100 | Unclear | Surface ES: 2 flat electrodes placed anteriorly over obturator foramen, 1.5‐2cm lateral to the symphysis; 2 electrodes placed posteriorly medial to ischial tuberosity on either side of the anus | 1st session 15 min, if no ill effects then 30 min for all subsequent sessions. 3 times a week, for 4 weeks (12 sessions) under supervision of a physiotherapist. Participants were asked to perform 8‐12 pelvic floor contractions 3 times a day at home |

| Pereira 2012 | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Pulse width 700 µs | 50 | 4 s on: 8 s off | Surface ES: 2 electrodes in suprapubic region, 2 medial to the ischial tuberosity | 2 x 20 min sessions per week for 6 weeks (12 sessions). "The women were not instructed to perform the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles in conjunction with electrical stimulation" |

| Pohl 2004 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Preisinger 1990 | Unclear | Surging faradic‐type current | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 3 x 10 min sessions per week for 10‐12 weeks |

| Sand 1995 | Unclear | Gradually adjusted amperage to 60‐80 mA or highest tolerable level | Unclear | Unclear | First 2 weeks: 5 s on: 10 s off. Weeks 3‐4: 5s: 5s; weeks 5‐6: 5 s: 10 s; weeks 7‐12: 5 s: 5 s | Vaginal electrode ( 2.6 cm diameter, 6.35 cm length) with electrode resistance 85 Ω | Women instructed to use device twice daily for 12 weeks. First 4 weeks: 15 min sessions. Weeks 5‐12: 30 min |

| Santos 2009 | Unclear | 10‐100 mA | 1 ms | 50 | Unclear | Intravaginal: electrode: 10cm long, 3.5 cm wide with double metallic ring and cylindrical shape, positioned in medium third of the vagina | 2 x 20 min sessions per week for 4 months |

| Schmidt 2009 | Unclear | Unclear | 300 μs | 50 | Unclear | Unclear | 12 weeks (unclear how many sessions or duration of sessions) |

| Seo 2004 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | "Simultaneous electrical stimulation of 35 Hz and 50 Hz for 24 secs" | Unclear | Unclear | 2 x 20 min sessions per week for 6 weeks (12 sessions) (plus biofeedback) |

| Shepherd 1984 | Unclear | Up to 40 v | Unclear | 10‐50 | Unclear | Maximum perineal stimulation: Scott electrode in vagina, large indifferent electrode under buttocks | Single 20 min session |

| Shepherd 1985 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | 10 | Unclear | Intravaginal cushion attached to stimulator worn around waist | Cushion worn for 8/24 hours, day or night according to participant preference |

| Smith 1996 | Biphasic | 5 mA ‐ 10 mA, increased each month to 80 mA max (range 1‐100) | Asymmetric balanced biphasic pulse, 300 μs, | Channel 1: 50 Hz; channel 2: 12.5 Hz | 5 s contraction time (range 5‐15), duty cycle 1‐2 (range 1 to 1 to 2) | Unclear | 16 weeks (unclear how many sessions); increasing treatment time from 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes |

| Tapp 1987 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Intravaginal. Faradic stimulation using vaginal probe | 2 sessions per week for 1 month (session duration not reported) |

| Tapp 1989 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Intravaginal. Faradic stimulation using vaginal probe | 2 sessions per week for 1 month (session duration not reported) |

| Terlikowski 2013 | Unclear | Unclear | 200‐250 μs | 10‐40 | 15 s; 30 s | Intravaginal | 2 x 20 min sessions per day at home for 8 weeks |

| Whitmore 1995 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Wilson 1987 | Unclear | According to maximum participant tolerance | Unclear | Unclear | Groups of 12 surges/min, 2 min rest in between each group | Faradism. Surface electrodes. Saddle shaped indifferent electrode placed over the sacrum, active electrode applied to perineum | 6 weeks' treatment (session duration not reported) |

| Unclear | 20−25 mA | Unclear | Unclear | 15 pulses at pressure peak 0.25‐0.30 Pa/cmb | Interferential. 4 suction electrodes (2 on abdomen, 2 on adductor muscles) | First treatment 10 min, if no ill effects then duration increased to 15 min | |

| Wise 1993 | Unclear | 0‐90 mA, according to participant tolerance | Unclear | 20 | Unclear | Intravaginal | 1 session per day (at home) for 6 weeks |

EMG: electromyography; ES: electrical stimulation.

We excluded trials of magnetic stimulation and electro‐acupuncture.

Eligible comparators were no active treatment, placebo or sham treatment as well as drug therapy, surgery or any other intervention intended to decrease SUI, including conservative treatment (such as complementary therapies like acupuncture, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and vaginal cones). We also included studies comparing different ES methods. There were no restrictions by type of device, stimulation parameters (such as continuous, interrupted, duration of stimulation), duration of treatment, route of administration (vaginal, rectal, skin, pretibial area, etc.), or other similar factors. We excluded trials of different combinations of treatments if it was not possible to identify the effect of the ES intervention (e.g. ES plus another treatment versus other combined treatments).

We made the following comparisons.

ES versus no active treatment.

ES versus placebo or sham treatment.

ES versus other conservative treatment (e.g. bladder training, PFMT, biofeedback, magnetic stimulation).

ES versus drugs (e.g. duloxetine).

ES versus surgery or injection of bulking agents.

ES plus another treatment versus the other treatment alone.

One type of ES versus another.

We did not include studies where the comparator interventions, alone or as a supplement to ES, were different in the intervention and control arms (i.e. ES plus treatment A versus treatment B, with or without ES).

Types of outcome measures

We extracted outcome data reported at the end of treatment and at the end of the longest available follow‐up period. We considered the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence (no urinary incontinence, as reported by women)

Cure or improvement: number of women with self‐reported cure or improvement in urinary incontinence

Incontinence‐specific quality of life (QoL) measures (however defined by authors or by any validated measurement scales such as the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire)

Secondary outcomes

Satisfaction with treatment

Need for further treatment

QoL measures of general health status, e.g. the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36); QoL measures of sexual function or satisfaction; measures of psychological or emotional well‐being

Quantification of symptoms (e.g. number of incontinence episodes (every 24 hours), number of micturitions every 24 hours, pad tests)

Adverse effects (e.g. skin or tissue damage, pain or discomfort, vascular, visceral or nerve injury, voiding dysfunction)

Economic data (e.g. costs of interventions, resource implications, cost‐effectiveness of interventions in terms of incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs), costs per quality‐adjusted life year (QALY) or cost‐benefit ratios)

Tertiary outcomes

We extracted data related to the following assessments as indirect measures of the physiological effect of treatment.

Clinicians' observations (e.g. objectively measured cure, improvement or incontinence, such as observation of leakage, leakage observed at urodynamics study, urodynamic measurement parameters).

Pelvic floor muscle function, strength or ability to contract the pelvic floor muscles.

Any other outcomes judged important when performing the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not impose any restrictions, for example language or publication status, on the searches described below.

Electronic searches

We drew on the search strategy developed for Cochrane Incontinence. We identified relevant trials from the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register. For more details of the search methods used to build the Specialised Register, please see the Group's module in the Cochrane Library. The register contains trials identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print, ClinicalTrials.gov, WHO ICTRP and handsearching of journals and conference proceedings. Many of the trials in the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register are also contained in CENTRAL. The date of the last search for this review was 27 Feburary 2017.

The terms that we used to search the Cochrane Incontinence Specialised Register are in Appendix 1.

Economic data searches

We also undertook separate searches to identify studies examining the economic data of ES for SUI. Using the search strategies presented in Appendix 1, we searched the following databases on 10 February 2016. No limits were applied. The first four databases were searched via OvidSP and the last two were searched on their own websites.

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to January week 4 2016).

Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations (covering to 9 February 2016).

Embase (1974 to 9 February 2016).

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (1983 to 9 February 2016).

Cost‐Effectiveness Analysis Registry (CEA Registry) (from inception to 9 February 2016).

Research Papers in Economics (RePEc) (from inception to 9 February 2016).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of the identified relevant studies for additional citations. We consulted with clinical specialists and contacted the authors of included trials where appropriate to obtain unpublished data or to seek clarification on ambiguous data in published trial reports.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted the review in accordance with the methods outlined in the published protocol unless otherwise stated in the Differences between protocol and review section (Stewart 2016b).

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently screened the trials identified by the literature search, resolving any disagreements by discussion or by referring to a third party.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors extracted data independently, resolving any disagreements by discussion or by referring to a third party. We used a standard data extraction form to extract data on study characteristics (design, methods of randomisation), participants, interventions and outcomes.

We would have developed a data extraction form for economic evaluations based on the format and guidelines used to produce structured abstracts of economic evaluations for inclusion in the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), according to the specific requirements of this review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risks of bias with the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011), which addresses the following kinds of bias.

Selection bias (randomisation and allocation concealment).

Performance bias (blinding of participants, caregivers).

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors).

Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data or differential withdrawal).

Reporting bias (selective reporting of outcomes).

Other bias.

Two review authors independently carried out risk of bias assessments and resolved any disagreements by consulting a third author.

We would have assessed the overall methodological quality of included economic evaluations by applying a combination of Consolidated Health Economics Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement (Husereau 2013) and CHEC Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations (Evers 2005).

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). For continuous data, we present the mean difference (MD) with a 95% CI. We calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measure the same outcome but using different methods such as different quality of life instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed studies with multiple treatment groups by splitting the 'shared' group to create independent comparisons. For instance, we would analyse a trial comparing one kind of ES versus another kind of ES versus PFMT by splitting the PFMT group to create two smaller groups.

We would have analysed studies with non‐standard designs, such as cross‐over trials and cluster‐randomised trials, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Had data from randomised cross‐over trials been incomplete, we would have included data from the first period of randomisation only.

The unit of analysis was each woman recruited into the trials.

Dealing with missing data

We followed an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle as far as possible, analysing data from all participants according to the groups to which they were randomised. Where participants were excluded after allocation or withdrew from the trial, we reported any available details in full.

Where trials reported mean values without standard deviations (SDs) but with P values or 95% CIs, we used the Review Manager 5 (RevMan 5) calculator to estimate the SD (RevMan 2014). Where trials reported mean values only, we assumed the outcome to have an SD equal to the highest SD from the other trials within the same analysis.

We made all reasonable attempts to contact authors for clarification of missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining the trial methods and tested for statistical heterogeneity between trial results using the Chi² test and the I² statistic (Higgins 2011). We considered that heterogeneity may not be important if less than 30%, may be moderate if valued at 30% to 50%, and may be substantial if above 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to assess the likelihood of potential publication bias using funnel plots, provided that we identified 10 or more eligible trials contributing to an outcome, but there were insufficient trials.

Data synthesis

We used the fixed‐effect model to analyse data. Where there was significant heterogeneity (for example I² higher than 50%), we computed pooled estimates of the treatment effect for each outcome using a random‐effects model.

We would have summarised the characteristics and results of included economic evaluations using additional tables, supplemented by a narrative summary to compare and evaluate methods used and principal results between studies. Unit cost data were be tabulated.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If data permitted, we intended to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Population: trials with participants with SUI only versus participants with MUI.

Different approaches to electrode placement (transcutaneous (e.g. perineal skin, sacral) versus vaginal or anorectal).

If we found substantial heterogeneity (I² more than 50%), we investigated the possible causes and would have carried out subgroup analyses if appropriate.

Sensitivity analysis

If data permitted, we intended to perform sensitivity analysis comparing trials at low risk of selection bias to those at high risk of selection bias to test the robustness of the results, but there were insufficient numbers of trials in the meta‐analyses.

'Summary of findings' table

We applied the principles of the GRADE system to assess the quality of the body of evidence (Guyatt 2008). This approach uses four categories (very low, low, moderate and high) to rate the quality of evidence available for selected outcomes; for instance, evidence from RCTs starts at a level of high quality but may be downgraded if there are other indications of low quality, such as small sample sizes or high risk of bias.

We included the following outcomes in 'Summary of findings' tables.

Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence.

Improvement: number of women with self‐reported improvement in SUI (cured or improved).

QoL measures due to SUI.

Adverse effects: pain or discomfort due to treatment.

Cost‐effectiveness of interventions.

We used GRADEpro GDT 2015 software to create the 'Summary of findings' tables.

We pre‐specified seven comparisons, but in this review we present 11 'Summary of findings' tables because several of our pre‐specified comparisons were broad categories encompassing heterogeneous interventions (e.g. one type of ES versus another), and we considered it to be more meaningful to present 'Summary of findings' tables separately for each subcomparison.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

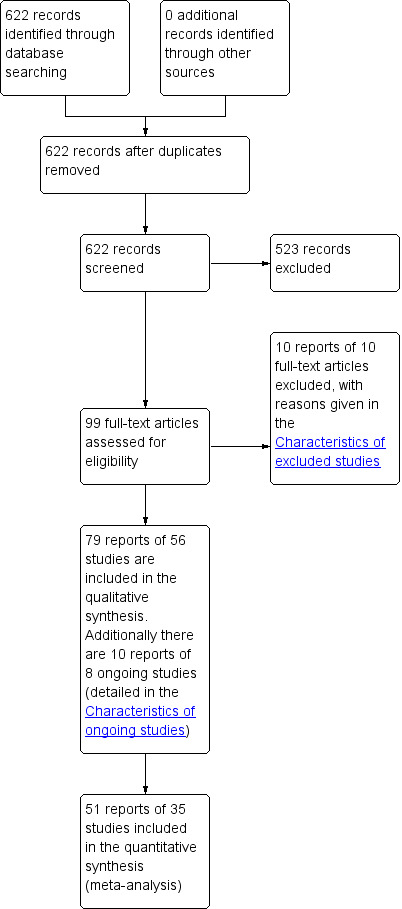

The electronic searches yielded 622 records, 99 of which we selected for full‐text screening. Fifty‐six studies (79 reports), involving 3781 randomised women, met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review. Additionally, there were 10 reports of 8 ongoing studies (see the Characteristics of ongoing studies). Figure 1 shows the flow of literature through the assessment process.

1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

The searches for economic data yielded 215 records, 31 of which we selected for full‐text screening. However, none of these met our eligibility criteria.

Included studies

Design

All of the studies were randomised controlled trials.

Sample size

The sample sizes in the included trials ranged from 14 to 200 women (mean N = 67, median N = 56).

Setting

Most of the trials took place in hospital settings, with the exception of nine trials investigating types of ES for home or portable use (Goode 2003; Hahn 1991; Jeyaseelan 1999; Jeyaseelan 2002; Knight 1998; Lopes 2014; Maher 2009; Oldham 2013; Parsons 2004).

The included trials were based in the following countries.

Twenty in the UK (Bidmead 2002; Bridges 1988; Edwards 2000; Haig 1995; Henalla 1989; Jeyaseelan 1999; Jeyaseelan 2002; Jeyaseelan 2003; Knight 1998, Laycock 1988, Olah 1990; Oldham 2013; Parsons 2004; Patil 2010; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985; Tapp 1987; Tapp 1989; Wilson 1987; Wise 1993).

Nine in Brazil (Alves 2011; Bernardes 2000; Beuttenmuller 2010; Castro 2008; Correia 2013; Correia 2014; Pereira 2012; Santos 2009; Schmidt 2009).

Seven in the USA (Brubaker 1997; Firra 2013; Goode 2003; Luber 1997; Sand 1995; Smith 1996; Whitmore 1995).

Two each in Austria (Hofbauer 1990; Preisinger 1990), France (Bourcier 1994; Lopes 2014), and Germany (Huebner 2011; Pohl 2004).

One each in Australia (Lo 2003), China (Min 2015), Denmark (Abel 1997), Iceland (Eyjolfsdottir 2009), Ireland (Maher 2009), Italy (Delneri 2000), Korea (Seo 2004), Norway (Bø 1999), Poland (Terlikowski 2013), Sweden (Hahn 1991), and Turkey (Demirturk 2008).

Three trials did not report any details on their setting (Aaronson 1995; Laycock 1993a; Laycock 1993b).

Participants

Almost all trials included only women with stress urinary incontinence.

Nine trials included women with other kinds of incontinence (Beuttenmuller 2010; Demirturk 2008; Goode 2003; Huebner 2011; Lo 2003; Lopes 2014; Schmidt 2009; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985).

Three of these included some women with stress urinary incontinence alone and others with stress‐predominant MUI (Goode 2003; Huebner 2011; Lopes 2014).

Four trials did not separate data according to type of incontinence or excluded women with urgency urinary incontinence (Lo 2003; Schmidt 2009; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985).

Two trials did not define the type of incontinence (Beuttenmuller 2010; Demirturk 2008).

One trial was restricted to women who had been referred for continence surgery (Hahn 1991).

Pereira 2012 and Goode 2003 restricted their inclusion criteria on the basis of age; over 60 years and over 40 years, respectively.

The mean age in the included trials ranged from 41 to 69 years. Fourteen trials did not report age (Bidmead 2002; Bourcier 1994; Jeyaseelan 1999; Jeyaseelan 2002; Jeyaseelan 2003; Knight 1998; Pohl 2004; Schmidt 2009; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985; Tapp 1987; Tapp 1989; Whitmore 1995; Wise 1993).

Interventions

The included trials reported a range of different kinds of ES; most were intravaginal ES interventions, while others used surface electrodes. The intervention regimens were characterised by their wide diversity in terms of current, current intensity, pulse shape and duration, frequency (Hz), duty cycle, electrodes, and duration of treatment and its supervision. In most cases trialists failed to report at least one of these parameters. Table 12 shows the full details of the types, frequencies and parameters of the ES interventions.

Comparators included:

no active treatment (Correia 2013; Correia 2014; Bidmead 2002; Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Henalla 1989; Hofbauer 1990; Oldham 2013; Pereira 2012);

sham electrical stimulation (Abel 1997; Bidmead 2002; Brubaker 1997; Hofbauer 1990; Jeyaseelan 1999; Laycock 1993b; Luber 1997; Preisinger 1990; Sand 1995; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985; Terlikowski 2013; Whitmore 1995); Table 13 presents details of the sham interventions;

placebo (Abel 1997);

pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) (Aaronson 1995; Bernardes 2000; Bidmead 2002; Bø 1999; Bourcier 1994; Castro 2008; Demirturk 2008; Eyjolfsdottir 2009; Hahn 1991; Lo 2003; Hofbauer 1990; Huebner 2011; Jeyaseelan 2002; Jeyaseelan 2003; Pohl 2004; Preisinger 1990; Smith 1996).

vaginal cones (Bridges 1988; Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Delneri 2000; Olah 1990; Santos 2009; Seo 2004; Wise 1993);

PFMT plus vaginal cones (Bourcier 1994; Laycock 1993a; Wise 1993);

drug therapy (Abel 1997; Henalla 1989);

vaginal oestrogen cream (Henalla 1989).

2. Description of sham electrical stimulation interventions.

| Study | Description of sham interventiona |

| Brubaker 1997 | Identical device to the intervention group with disconnected wire so no electricity supplied |

| Hofbauer 1990 | Electrodes placed in the lumbar region |

| Jeyaseelan 1999 | One 250 μ impulse every minute for 60 min (proven to have no physiological effect on muscle) |

| Laycock 1993b; | Machine modified to bypass the patient circuit and divert the interferential current to a separate circuit within the machine so the participant received no current. Participants told to expect no sensation |

| Luber 1997 | Wiring from the unit to the probe was covertly discontinuous |

| Sand 1995 | Same system as intervention group but limited to maximum output 1 mA |

| Shepherd 1984 | Vaginal electrode but no current |

| Shepherd 1985 | Identical device to intervention group but not activated |

| Terlikowski 2013 | Women were provided with a placebo set to parameters proven to have no physiological effect |

aFour of 13 trials comparing ES with sham ES did not describe the sham intervention in detail.

Fifteen trials compared ES plus another treatment to the other treatment alone.

ES plus PFMT (Beuttenmuller 2010; Bidmead 2002; Edwards 2000; Firra 2013; Goode 2003; Haig 1995; Hofbauer 1990; Huebner 2011; Knight 1998; Jeyaseelan 2002; Jeyaseelan 2003; Parsons 2004; Patil 2010; Schmidt 2009; Tapp 1987; Tapp 1989).

ES plus behavioural training (Goode 2003).

ES plus surgery (Min 2015).

Six trials compared different types of ES to each other (Alves 2011; Correia 2013; Correia 2014; Knight 1998; Maher 2009; Wilson 1987).

The control group in Castro 2008 received a motivational phone call once a month for six months. In another trial, the control group received "any other therapy at the discretion of the investigator" (Lopes 2014). For the purposes of our review, we treated these two comparators as no active treatment.

Follow‐up

Five trials reported outcomes at more than one follow‐up point, usually once the end of the treatment period and again at a further follow‐up point.

Outcomes

Eleven of the included trials did not report any usable data suitable for analysis in this review (Aaronson 1995; Abel 1997; Bidmead 2002; Correia 2013; Lo 2003; Maher 2009; Parsons 2004; Shepherd 1984; Shepherd 1985; Whitmore 1995; Wise 1993).

Eighteen of the included trials did not report any usable data relating to our primary outcomes of woman‐reported cure or improvement, or incontinence‐specific quality of life. No trials provided information about sexual function or psychological or emotional well‐being. We did not identify any economic evaluations conducted alongside included trials.

The Characteristics of included studies provides further information.

Excluded studies

After full‐text screening, we excluded 43 trials from the review. The main reasons for exclusion were ineligible study design (i.e. non‐RCTs), ineligible population (i.e. participants did not have SUI) and ineligible interventions such as sacral neuromodulation with implanted devices or magnetic stimulation.

See the Characteristics of excluded studies for full details of the most important excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

We identified eight ongoing studies, investigating the following comparisons (two of the ongoing studies are three‐arm trials).

ES versus placebo (Robson 2013).

ES versus PFMT (Jha 2013; NCT02185235 2014).

ES versus vaginal cones (ACTRN12610000254099).

ES compared with kinesiotherapy (ACTRN12610000254099).

ES plus PFMT versus PFMT alone (Maher 2010).

ES version A plus PFMT compared with ES version B plus PFMT (Maher 2010).

One type of ES versus another (Maher 2010; NCT00762593 2006; NCT02423005 2015; Robson 2014).

Further details are available in the Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

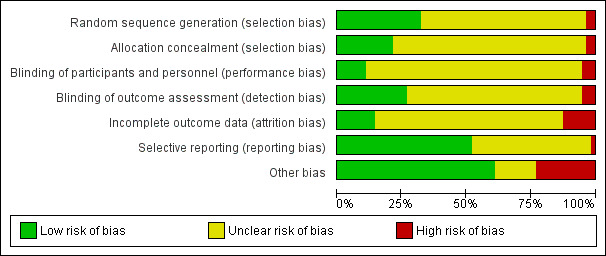

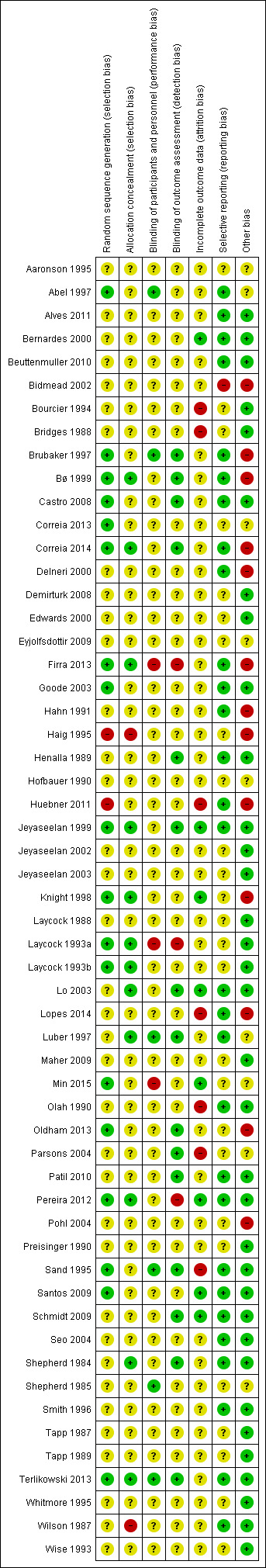

Please see Figure 2 for a summary of the risk of bias in the included trials and Figure 3 for the results of the risk of bias assessment in each trial for each domain.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Most trials (36/56) did not adequately report randomisation methods and so were at unclear risk of selection bias. Two trials were at high risk of selection bias because group allocation was not carried out on a truly randomised basis (Haig 1995; Huebner 2011). We judged the remaining trials (18/56) to have undertaken sufficiently robust randomisation procedures and considered them at low risk of selection bias.

Allocation concealment

We assessed two trials as being at high risk of selection bias because of inadequate allocation concealment (Haig 1995; Wilson 1987). Twelve trials reported adequate allocation concealment methods, meriting a judgment of low risk of selection bias, and the remainder did not report allocation methods in sufficient detail to make a clear determination.

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

We judged three trials as being at high risk of performance bias because of inadequate blinding of participants (Firra 2013; Laycock 1993a; Min 2015). In many other cases, it was not possible to blind participants, and the risk of performance bias was unclear. Six trials reported adequate methods for blinding participants appropriately and were therefore at low risk of performance bias (Abel 1997; Brubaker 1997; Luber 1997; Sand 1995; Shepherd 1985; Terlikowski 2013).

Blinding of outcome assessment

Fifteen trials reported adequate blinding of outcome assessment (Brubaker 1997; Bø 1999; Castro 2008; Correia 2014; Henalla 1989; Jeyaseelan 1999; Lo 2003; Luber 1997; Oldham 2013; Parsons 2004; Patil 2010; Sand 1995; Schmidt 2009; Shepherd 1984; Terlikowski 2013). We considered three trials to be at high risk of detection bias because the outcome assessors were not blinded to the participants' group allocation (Firra 2013; Laycock 1993a; Pereira 2012). The remaining trials did not report blinding of outcome assessment in sufficient detail, and their risk of detection bias was therefore unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

Seven trials were at high risk of attrition bias for reasons such as differential withdrawal, unclear reporting of withdrawals per group and disparities between attrition data reported in the text and in the tables (Bourcier 1994; Bridges 1988; Huebner 2011; Lopes 2014; Olah 1990; Parsons 2004; Sand 1995). We judged eight trials to be at low risk of attrition bias because they had undertaken robust statistical methods for dealing with missing data, or they reported very low attrition in all groups (Bernardes 2000; Jeyaseelan 1999; Knight 1998; Lo 2003; Min 2015; Pereira 2012; Santos 2009; Schmidt 2009). The remaining trials did not report sufficient detail regarding attrition to make a clear determination on their risk of bias.

Selective reporting

We judged one trial to be at high risk of reporting bias because authors reported having collected data relating to symptom scores and quality of life outcomes, but the trial report did not include the details of the data (Bidmead 2002).

Twenty‐six trials did not report sufficient detail for us to judge their risk of reporting bias (Aaronson 1995; Bourcier 1994; Bridges 1988; Correia 2013; Demirturk 2008; Edwards 2000; Eyjolfsdottir 2009; Haig 1995; Hofbauer 1990; Jeyaseelan 2002; Jeyaseelan 2003; Knight 1998; Laycock 1988; Laycock 1993a; Laycock 1993b; Maher 2009; Min 2015; Oldham 2013; Parsons 2004; Pohl 2004; Preisinger 1990; Shepherd 1985; Tapp 1987; Tapp 1989; Whitmore 1995; Wise 1993). We judged the remaining trials to be at low risk of reporting bias because there was sufficient indication that they had reported all pre‐specified outcomes in full for each treatment group.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged 14 trials to be at high risk of bias for various reasons.

Technical problems with intervention equipment (Brubaker 1997).

Unclear role of funders likely to have vested interests in one of the interventions (Bø 1999; Eyjolfsdottir 2009; Hahn 1991; Lopes 2014; Oldham 2013).

Differences in intervention delivery procedures between the protocol and the trial report (Correia 2014).

Baseline differences between groups (Bidmead 2002; Delneri 2000; Firra 2013; Haig 1995; Huebner 2011; Knight 1998; Pohl 2004).

Some trials were reported only as abstracts with limited information, and we judged these to be at unclear risk of bias from other sources (Aaronson 1995; Abel 1997; Correia 2013; Parsons 2004; Shepherd 1985). The risk of other bias was also unclear in three non‐English language trials where only partial translation was available (Eyjolfsdottir 2009; Hofbauer 1990; Min 2015), plus one more that stopped early because interim analysis suggested no difference between groups (Luber 1997).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Electrical stimulation versus no active treatment.

| Electrical stimulation versus no active treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home and/or hospitals (Brazil, France, Norway, UK) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: no active treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no active treatment | Risk with electrical stimulation | |||||

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence Follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 2.31 (1.06 to 5.02) | 101 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — | |

| 122 per 1000 | 283 per 1000 (130 to 615) | |||||

| Improvement: number of women with self‐reported improvement in SUI (cured or improved) Follow‐up: range 12 weeks to 9 months | Study population | RR 1.73 (1.41 to 2.11) | 347 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | — | |

| 382 per 1000 | 660 per 1000 (538 to 805) | |||||

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life (higher score = worse quality of life) assessed with: King's Health Questionnaire, Incontinence Severity Index, ICI‐Q Follow‐up: median 6 weeks | The mean incontinence‐specific quality of life score was 0.72 standard deviations lower (0.99 lower to 0.45 lower). | — | 250 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | A standard deviation of 0.80 represents a large difference between groups | |

| Adverse effects Follow‐up: range 6 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 5.96 (0.30 to 118.70) | 103 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,d | 2 trials reported no women with adverse effects in either group. 1 trial reported 2 women with adverse effects in the ES group (1 tenderness and bleeding, 1 discomfort) |

|

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ES: electrical stimulation; ICI‐Q: International Consultation on Incontience Questionnaire; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SUI: stress urinary incontinence. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (small sample sizes, few events and wide confidence intervals around estimates of effect). bDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (manufacturer involved in some trials). cDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (small sample sizes, few events and wide confidence intervals around estimates of effect). dDowngraded one level due to risk of serious risk of bias (detection, performance, attrition bias or manufacturers' involvement).

Summary of findings 2. Electrical stimulation versus sham treatment.

| Electrical stimulation versus sham treatment | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home and/or hospital (Austria, Denmark, Poland, UK, USA) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: sham treatment | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with sham treatment | Risk with electrical stimulation | |||||

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence Follow‐up: range 12 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 2.21 (0.38 to 12.73) | 158 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — | |

| 95 per 1000 | 210 per 1000 (36 to 1000) | |||||

| Improvement: number of women with self‐reported improvement in SUI (cured or improved) Follow‐up: range 12 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 2.03 (1.02 to 4.07) | 236 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | — | |

| 198 per 1000 | 402 per 1000 (202 to 805) | |||||

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life assessed with: IIQ, UDI, I‐QoL Follow‐up: range 8 weeks to 16 weeks | One trial found significantly better I‐QoL scores in the ES group, while another trial found no evidence of a difference between groups in IIQ or UDI scores. | — | 117 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | — | |

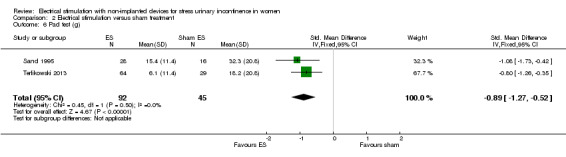

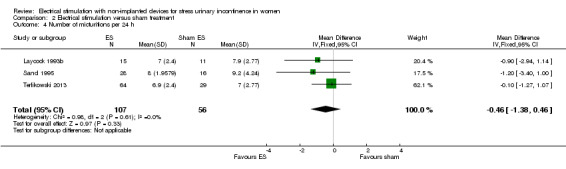

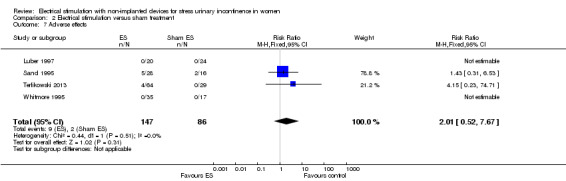

| Adverse effects Follow‐up: range 12 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 2.01 (0.52 to 7.67) | 233 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc | 2 trials reported no women with adverse effects in either group. 2 trials reported vaginal irritation, bleeding and discomfort in the ES groups. |

|

| 23 per 1000 | 47 per 1000 (12 to 178) | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ES: electrical stimulation; IIQ: incontinence impact questionnaire; I‐QoL: Incontincence Quality of Life questionnaire; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SUI: stress urinary incontinence; UDI: urogenital distress inventory. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to unclear risk of bias in most domains). bDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (different directions of effect). cDowngraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (few trials and events, small sample sizes, wide confidence intervals around estimates of effect)

Summary of findings 3. Electrical stimulation versus pelvic floor muscle training.

| Electrical stimulation versus PFMT | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home and/or hospital (Austria, Brazil, France, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Turkey, UK, USA) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PFMT | Risk with Electrical stimulation | |||||

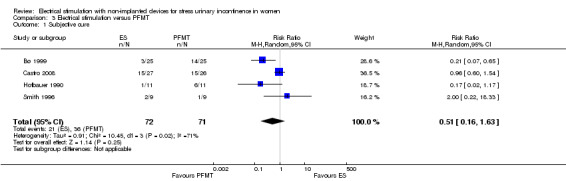

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence Follow‐up: median 6 months | Study population | RR 0.51 (0.16 to 1.63) | 143 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 507 per 1000 | 259 per 1000 (81 to 826) | |||||

| Improvement: number of women with self‐reported improvement in SUI (cured or improved) Follow‐up: range 3 months to 4 years | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.70 to 1.03) | 244 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 669 per 1000 | 569 per 1000 (469 to 690) | |||||

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life assessed with: I‐QoL and unvalidated instrument Follow‐up: range 5 weeks to 6 months | None of the trials found any evidence of a difference between groups. | — | 93 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — | |

| Adverse effects Follow‐up: range 5 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 5.00 (0.25 to 99.16) | 121 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | 2 trials reported no women with adverse effects in either group. 1 trial reported 2 women with adverse effects in the ES group (1 tenderness and bleeding, 1 discomfort) |

|

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ES: electrical stimulation; I‐QoL: Incontincence Quality of Life questionnaire; PFMT: pelvic floor muscle training; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SUI: stress urinary incontinence. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (unclear risk of bias in most domains). bDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (different directions of effect). cDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (very small sample sizes). dDowngraded two levels due to serious imprecision (estimate based on single trial with very wide confidence intervals).

Summary of findings 4. Electrical stimulation versus vaginal cones.

| Electrical stimulation versus vaginal cones | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home and/or hospital (Brazil, Italy, Korea, Norway, UK) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: vaginal cones | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with vaginal cones | Risk with electrical stimulation | |||||

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence Follow‐up: median 6 months | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.70 to 1.54) | 157 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 363 per 1000 | 454 per 1000 (341 to 606) | |||||

| Subjective cure or improvement Follow‐up: range 4 weeks to 6 months | Study population | RR 1.09 (0.97 to 1.21) | 331 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | — | |

| 685 per 1000 | 768 per 1000 (678 to 863) | |||||

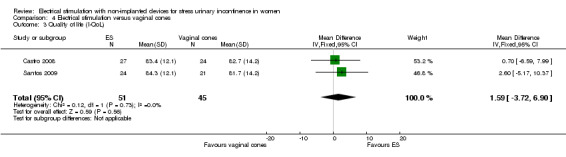

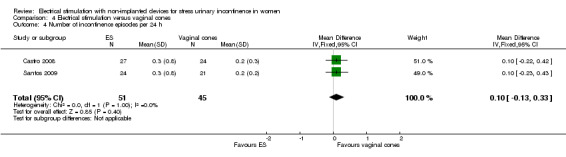

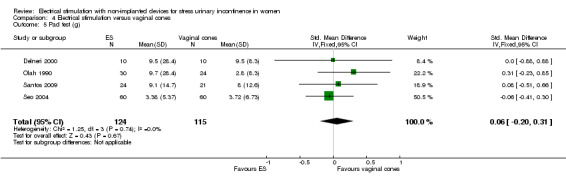

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life assessed with: I‐QoL (range of possible scores: 0‐100) Follow‐up: range 4 months to 6 months | — | MD 1.59 higher (3.72 lower to 6.9 higher) | — | 96 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | Minimum clinically important difference between treatments is 2.5 points |

| Adverse effects Follow‐up: mean 6 months | Study population | RR 0.54 (0.11 to 2.70) | 52 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe,f | Adverse effects in the ES group:

Adverse effects in the vaginal cones group:

|

|

| 148 per 1000 | 80 per 1000 (16 to 400) | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; ES: electrical stimulation; I‐QoL: Incontincence Quality of Life questionnaire; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious risk of attrition bias. bDowngraded one levels due to serious imprecision (few trials and events, small sample sizes, wide confidence intervals around estimates of effect). cDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (unclear risk of bias in most domains). dDowngraded one level due to serious imprevision (small sample sizes, wide confidence intervals around estimates of effect). eDowngraded one level due to serious risk of bias (manufacturer's funding and provision of intervention equipment). fDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (single trial with small sample size).

Summary of findings 5. Electrical stimulation versus PFMT plus vaginal cones.

| Electrical stimulation versus PFMT plus vaginal cones | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home (UK) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: PFMT plus vaginal cones | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PFMT plus vaginal cones | Risk with electrical stimulation | |||||

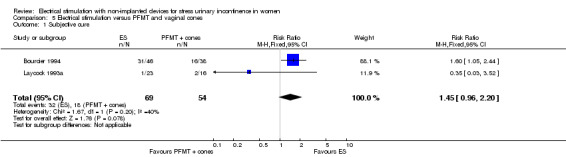

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.45 (0.96 to 2.20) | 123 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | — | |

| 333 per 1000 | 483 per 1000 (320 to 733) | |||||

| Subjective cure or improvement Follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | Study population | RR 1.53 (1.08 to 2.18) | 123 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | — | |

| 426 per 1000 | 652 per 1000 (460 to 929) | |||||

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse effects | Not reported | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to serious risk of performance and detection bias. bDowngraded one level due to serious imprecision (small sample sizes, few events). cDowngraded one level due to serious inconsistency (different directions of effect).

Summary of findings 6. Electrical stimulation versus drug therapy.

| Electrical stimulation versus drug therapy | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with stress urinary incontinence Setting: home and hospital (UK) Intervention: electrical stimulation Comparison: drug therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with drug therapy | Risk with electrical stimulation | |||||

| Cure: number of women with self‐reported continence | Not reported | |||||

| Subjective cure or improvement Follow‐up: mean 9 months | Study population | RR 13.89 (0.84 to 230.82) | 50 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | — | |

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Incontinence‐specific quality of life | Not reported | |||||

| Adverse effects | Not reported | |||||

| Cost‐effectiveness | Not reported | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||