Abstract

Background

Many patients with cancer experience moderate to severe pain that requires treatment with strong analgesics. Buprenorphine, fentanyl and morphine are examples of strong opioids used for the relief of cancer pain. Strong opioids are, however, not effective for pain in all patients nor are they well‐tolerated by all patients. The aim of this Cochrane review is to assess whether buprenorphine is associated with superior, inferior or equal pain relief and tolerability compared to other analgesic options for patients with cancer pain.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and tolerability of buprenorphine for pain in adults and children with cancer.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL (the Cochrane Library) issue 12 or 12 2014, MEDLINE (via OVID) 1948 to 20 January 2015, EMBASE (via OVID) 1980 to 20 January 2015, ISI Web of Science (SCI‐EXPANDED & CPCI‐S) to 20 January 2015, ISI BIOSIS 1969 to 20 January 2015. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/; metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/), the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and the Proceedings of the Congress of the European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP; via European Journal of Pain Supplements) on 16 February 2015. We checked the bibliographic references of identified studies as well as relevant studies and systematic reviews to find additional trials not identified by the electronic searches. We contacted authors of included studies for other relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials, with parallel‐group or crossover design, comparing buprenorphine (any formulation and any route of administration) with placebo or an active drug (including buprenorphine) for cancer background pain in adults and children.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data pertaining to study design, participant details (including age, cancer characteristics, previous analgesic medication and setting), interventions (including details about titration) and outcomes, and independently assessed the quality of the included studies according to standard Cochrane methodology. As it was not feasible to meta‐analyse the data, we summarised the results narratively. We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE approach.

Main results

In this Cochrane review we identified 19 relevant studies including a total of 1421 patients that examined 16 different intervention comparisons.

Of the studies that compared buprenorphine to another drug, 11 studies performed comparative analyses between the randomised groups, and five studies found that buprenorphine was superior to the comparison treatment. Three studies found no differences between buprenorphine and the comparison drug, while another three studies found treatment with buprenorphine to be inferior to the alternative treatment in terms of the side effects profile or patients preference/acceptability.

Of the studies that compared different doses or formulations/routes of administration of buprenorphine, pain intensity ratings did not differ significantly between intramuscular buprenorphine and buprenorphine suppository. However, the average severity of dizziness, nausea, vomiting and adverse events as a total were all significantly higher in the intramuscular group relatively to the suppository group (one study).

Sublingual buprenorphine was associated with faster onset of pain relief compared to subdermal buprenorphine, with similar duration analgesia and no significant differences in adverse event rates reported between the treatments (one study).

In terms of transdermal buprenorphine, two studies found it superior to placebo, whereas a third study found no difference between placebo and different doses of transdermal buprenorphine.

The studies that examined different doses of transdermal buprenorphine did not report a clear dose‐response relationship.

The quality of this evidence base was limited by under‐reporting of most bias assessment items (e.g., the patient selection items), by small sample sizes in several included studies, by attrition (with data missing from 8.2% of the enrolled/randomised patients for efficacy and from 14.6% for safety) and by limited or no reporting of the expected outcomes in a number of cases. The evidence for all the outcomes was very low quality.

Authors' conclusions

Based on the available evidence, it is difficult to say where buprenorphine fits in the treatment of cancer pain with strong opioids. However, it might be considered to rank as a fourth‐line option compared to the more standard therapies of morphine, oxycodone and fentanyl, and even there it would only be suitable for some patients. However, palliative care patients are often heterogeneous and complex, so having a number of analgesics available that can be given differently increases patient and prescriber choice. In particular, the sublingual and injectable routes seemed to have a more definable analgesic effect, whereas the transdermal route studies left more questions.

Plain language summary

Buprenorphine for treating people with cancer pain

Buprenorphine produced good pain relief for most people with moderate or severe cancer pain, but its role in the treatment of cancer pain is still unclear.

Many patients with cancer experience moderate‐to‐severe pain that requires treatment with strong pain relief medicines. Buprenorphine and morphine are examples of strong pain relief medicines that are used for the relief of cancer pain. However, strong pain relief medicines are not effective for pain in all patients nor are they well‐tolerated by all patients. The aim of this Cochrane review is to assess whether buprenorphine is associated with better, worse or equal pain relief and tolerability compared to other pain relief medicines for patients with cancer pain.

We searched the literature on 20 Janurary 2015 and found 19 relevant studies with a total of 1421 patients that compared different types of buprenorphine to each other or to other strong pain relief medicines or to placebo. The reported average ages of the patients ranged from 49.1 years to 67.16 years, and the duration of the studies ranged from single dose treatment to six months.

Generally, the studies showed that buprenorphine is an effective strong pain relief medicine that in some cases may be slightly better than other strong pain relief medicines. However, the evidence provided by these studies were of very low quality and on the basis of the available evidence, it is still hard to say where buprenorphine fits in in the treatment of cancer pain with strong opioids. All the strong pain relief medicines examined in the studies are also associated with a number of unwanted effects, such as vomiting, constipation and drowsiness.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Quality assessment | Summary of findings | |||||||||||||||||

| No of patients | Effect | Quality | ||||||||||||||||

| No of studies | Design | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Bup | Comparison | ||||||||||

| SL Bup versus SD Bup injection: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | SL: 10 | SD: 7 | Onset: SL faster Duration: SL = SD |

Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus SD Bup injection: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | SL: 10 | SD: 7 | SL = SD | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Til+Na: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 20 | 20 | Bup superior | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Til+Na: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 20 | 20 | Bup = Til+Na | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Tra: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 1233 | 1283 | Tra superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Tra: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 1233 | 1283 | Tra superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus SL Bup + oral P versus oral P: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | SL: 25 | SL+ P: 25 | P: 25 | SL = SL+P = P | Very low | |||||||

| SL Bup versus SL Bup + oral P versus oral P: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | SL: 25 | SL+P: 25 | P: 25 | SL = SL+P = P | Very low | |||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Pen: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 1204 | 1204 | Bup superior | Very low | ||||||||

| SL Bup versus oral Pen: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 1204 | 1204 | Bup ≠ Pen | Very low | ||||||||

| Bup tablets/fluid versus Pen Tab/F: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | Serious indirectness5 | Imprecision2 | None | Tab | F | Tab | F | Bup superior | Very low | ||||||

| 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||||||

| Bup tablets/fluid versus Pen Tab/F: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | Serious indirectness5 | Imprecision2 | None | Tab | F | Tab | F | Bup superior or similar | Very low | ||||||

| 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | |||||||||||||||

| TD Bup versus placebo: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | ‐35 μg/h: 102 ‐52.5 μg/h: 82 ‐70 μg/h: 169 |

189 | Bup better or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| TD Bup versus placebo: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | ‐35 μg/h: 102 ‐52.5 μg/h: 82 ‐70 μg/h: 169 |

189 | Apparently similar | Very low | ||||||||

| TD Bup versus controlled‐release Mor: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 26 | 26 | Bup superior | Very low | ||||||||

| TD Bup versus controlled‐release Mor: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 26 | 26 | Bup superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| TD Bup versus TD Fen: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 16 | 16 | Bup = Fen | Very low | ||||||||

| TD Bup versus TD Fen: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 16 | 16 | Fen superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| IM Bup injection versus Bup Sup: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | IM: 35 | Sup: 34 | IM = Sup | Very low | ||||||||

| IM Bup injection versus Bup Sup: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | IM: 35 | Sup: 34 | Sup superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| IM Bup versus IM Mor: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 376 | 376 | Bup superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| IM Bup versus IM Mor: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 274 | 274 | Mor superior or similar | Very low | ||||||||

| IM Bup + SC Bup versus SC Bup versus placebo (Pla) + SC Bup: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | IM+SC: 10 | SC: 10 | Pla+SC: 10 | Not analysed inferentially | Very low | |||||||

| IM Bup + SC Bup versus SC Bup versus placebo + SC Bup: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | IM+ SC: 10 | SC: 10 | Pla+SC: 10 | Pla+SC inferior or similar | Very low | |||||||

| Epidural Bup versus epidural Mor: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 6 | 6 | Bup = Mor | Very low | ||||||||

| Epidural Bup versus epidural Mor: Adverse events | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 6 | 6 | Bup = Mor | Very low | ||||||||

| Intravenous Bup versus intravenous Mor: Efficacy | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | Very serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Imprecision2 | None | 30 + 30 | 30 + 30 | Bup and Mor not compared inferentially | Very low | ||||||||

1The quality of the evidence provided by the included studies was compromised by under‐reporting with or without missing data. 2Low numbers of patients. 3One of the included studies was a crossover trial with a total of 60 patients. These 60 patients are included in the totals for both buprenorphine and tramadol. 4The included study was a crossover trial. The total number of patients are listed in the totals for both interventions. 5Two of the studies included patients with non‐cancer pain. 6Both included studies were crossover trials. The total number of patients are listed in the totals for both intervention.

Abbreviations: Bup = buprenorphine; F = fluid; Fen = fentanyl; IM = intramuscular; Mor = morphine; P = phenytoin; Pen = pentazocine; Pla = placebo; SC = subcutaneous; SD = subdermal; SL = sublingual; Sup = suppository; Tab = tablets; Til+Na = tilidin + naloxone; Tra = tramadol.

Background

Description of the condition

Pain affects approximately 75% of people with advanced cancer (Deandra 2008). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the incidence of cancer was just under 12.7 million new cases in 2008 and is estimated to reach over 15 million cases in 2020 (Ferlay 2010; Frankish 2003). Unrelieved cancer pain is a cause of major suffering worldwide. Globally, millions of people suffer from unrelieved pain, particularly in low‐ and middle‐income countries (World Bank 2013) where cancer is diagnosed in late stages when pain is often severe (Seya 2011; Ferlay 2010). Estimates of cancer pain prevalence vary widely. This has been due in part to a lack of standardisation in the definition of pain and the measures used to assess it, and because of the heterogeneity of cancer diagnoses. There is also heterogeneity in terms of where and in what setting patients with cancer and cancer pain receive their treatments (e.g., in outpatient clinics, in hospitals or in day units). In general, prevalence of pain at the time of cancer diagnosis and early in the course of disease is thought to be approximately 50%, increasing to 75% in the more advanced stages (Portenoy 1989). According to a systematic review, pain prevalence ranges from 33% in patients after curative cancer treatment, to 59% in patients on anticancer treatment and to 64% in patients with metastatic, advanced or terminal phase disease (van den Beuken‐van Everdingen 2007).

Cancer pain may be acute and chronic and is divided into four physiological types: nociceptive (somatic or visceral), neuropathic and sympathetically maintained pain (Foley 1998). Each of these pain types can result from the tumour itself causing compression or infiltration, or it may be more indirectly related to the cancer and its treatments, e.g., constipation, muscle spasms, post‐surgical scars or lymphoedema. Patients with cancer may have painful concurrent disorders which may be exacerbated by the presence of the cancer, e.g., osteoarthritis.

Description of the intervention

Buprenorphine is prescribed in the management of cancer pain, but is not a typical first‐line opioid. However, it is starting to experience a renaissance in the management of both chronic cancer and non‐cancer pain and it is also used in people with opioid‐dependence (Foster 2013).

The WHO classifies buprenorphine as a step III opioid analgesic (WHO 1996). It has mixed agonistic and antagonistic properties. Its opioid agonistic activity is exerted on µ‐opioid receptors and the ORL‐1 receptor, whilst it is a kappa‐ and delta‐opioid receptor antagonist (Lewis 2004; Rothman 1995; Zaki 2000). It is given either transdermally (via a patch), as an injection or via the oral mucosa (sublingually). Mainly metabolised by the liver, buprenorphine goes through dealkylation and glucuronidation and is excreted predominantly in bile. Buprenorphine pharmacokinetics vary with route of administration. Whilst the sublingual (SL) and intramuscular (IM) routes produce similar outcomes in terms of pain‐relief, when taken orally, buprenorphine undergoes extensive pre‐systemic elimination (Bullingham 1981; Bullingham 1983). Oral bioavailability is therefore low (15%) due to extensive first‐pass metabolism in the gastrointestinal mucosa and liver. However, it is longer‐acting than morphine. Whilst buprenorphine is rapidly absorbed via oral mucosa, absorption into the systemic circulation is slow (tmax is 30 minutes to 3.5 hours after a single dose; one to two hours with repeat dosing; Elkader 2005). However, it subsequently has a long duration of action (six to eight hours), which suggests that SL buprenorphine may be not suited for the management of breakthrough pain. Poulain 2008 has demonstrated the successful use of buprenorphine as a breakthrough analgesic for patients on maintenance transdermal (TD) buprenorphine.

Buprenorphine activity as a partial agonist at the µ receptor means it has agonist and antagonist activity. Its long duration of action is thought to be due to an unusually slow dissociation constant for the drug‐receptor complex. Naloxone appears to be relatively ineffective in reversing opioid effects from buprenorphine, despite naloxone's high affinity for the µ‐opioid receptor (Gal 1989), and this is due to buprenorphine's even stronger receptor affinity (Dahan 2010). In humans, a ceiling effect has been shown with buprenorphine for respiratory depression but not for analgesia (Dahan 2005; Dahan 2006). Whilst buprenorphine has been shown to slow intestinal transit, it possibly does this less than morphine (Bach 1991; Robbie 1979); importantly, constipation as an adverse effect may be less severe (Pace 2007). Buprenorphine also exerts little or no pressure on pancreatic and biliary ducts, distinguishing it from morphine in this respect (Staritz 1986). Compared with other opioids, buprenorphine causes little or no immunosuppression (Budd 2004; Sacerdote 2000; Sacerdote 2008). As a drug, buprenorphine does not accumulate in renal failure and is not removed by haemodialysis. This means that analgesia is unaffected, making it potentially clinically useful in these situations (Filitz 2006; Hand 1990).

Examples of buprenorphine patch preparations are three or seven day TD formulations (5, 10, 20, 35, 52.5, 70 µg/hour). It is a highly lipid‐soluble drug, making it ideal for TD delivery. Within patch formulations it is evenly distributed in a drug‐in‐adhesive matrix and its release is governed by the physical attributes of the matrix and proportional to the surface area of the patch. It is also available as an injection (300 µg). Buprenorphine via either the TD or injectable route is approved for managing moderate to severe chronic pain. SL tablets and a SL film preparation are also available in some countries and are combined with naloxone. Currently these are used for the treatment of opioid addiction, although some SL tablets (200 µg and 400 µg) without naloxone are available for chronic moderate to severe pain. It should not be used for acute pain, e.g., when there is a need for rapid dose titration for severe pain in cancer and palliative care settings.

Buprenorphine is most commonly prescribed as a TD formulation for cancer patients. It is estimated to be 70 to 115 times more potent than oral morphine (Likar 2008; Mercadante 2009; Sittl 2005). In practical terms, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has suggested using caution when calculating opioid equivalences for TD patches and that a TD buprenorphine patch of 20 µg/hour equates to approximately 30 mg of oral morphine daily (NICE 2012). All opioid conversions have to take into account inter‐individual differences in such factors as pain perception and opioid receptor affinity. Research into genetic, gender and immunological differences in how people respond to opioids will form an ever‐increasing part of pain management in the future.

Why it is important to do this review

Many patients with cancer experience moderate to severe pain that requires treatment with strong analgesics. In 1986, the WHO published the Method for Cancer Pain Relief (WHO analgesic ladder), advocating a stepwise approach to analgesia for cancer pain and revolutionising the use of oral opioids (WHO 1987). It recommended that morphine be used as a first‐line treatment for moderate to severe cancer pain. Observational studies have suggested that this approach results in pain control for 73% of patients (Bennett 2008) with a mean reduction in pain intensity of 65% (Ventafridda 1987).

Buprenorphine, oxycodone (Schmidt‐Hansen 2015), fentanyl (Hadley 2013), hydromorphone (Quigley 2002), methadone (Nicholson 2007) and morphine (Wiffen 2013) are examples of more commonly used opioids used for the relief of cancer pain worldwide. However, Step III opioids are ineffective for treating pain in all patients (Pergolizzi 2008) and are not well‐tolerated by all patients. However, buprenorphine does not accumulate in renal impairment and is not removed by haemodynamics, making it a practical analgesic in some situations where the use of other strong opioids may be more problematic.

The aim of this Cochrane review is to assess whether buprenorphine is associated with superior, inferior or equal pain relief and tolerability compared to other analgesic options for patients with cancer pain.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and tolerability of buprenorphine for pain in adults and children with cancer.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), with parallel‐group or cross‐over design, comparing buprenorphine (any formulation and any route of administration) with placebo or an active drug (including buprenorphine) for treating people with cancer background pain. We did not examine studies on breakthrough pain.

Types of participants

Adults and children with cancer pain.

Types of interventions

Buprenorphine (any dose, formulation and route of administration) versus buprenorphine (any dose, formulation and route of administration);

Buprenorphine (any dose, formulation and route of administration) versus other active drug (any dose, formulation and route of administration);

Buprenorphine (any dose, formulation and route of administration) versus placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

-

Pain intensity and pain relief:

Both outcomes had to be patient‐reported and could be reported in any transparent manner (e.g., by using numerical or verbal rating scales);

We did not consider these outcomes reported by physicians, nurses or carers;

If possible, we aimed to distinguish between nociceptive and neuropathic pain. However, this was not possible on the basis of the included trials.

In line with Wiffen 2013, we looked for outcomes that are equivalent to 'no worse than mild pain' (Moore 2013) operationalised as either one of the following:

No or mild pain;

≤ 3/10 on a numerical rating scale;

≤ 30/100 mm on a visual analogue scale;

Positive ratings on patient measures of satisfaction (usually very satisfied), or treatment success, or global impression of change (very good, excellent).

Secondary outcomes

Side effects or adverse events (e.g., constipation, nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, confusion, respiratory depression), quality of life and patient preference. We considered all of these outcomes as they were reported in the included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

We did not apply language, date or publication status (published in full, published as abstract or unpublished) restrictions to the search.

Electronic searches

We identified relevant trials by searching the following databases on 20 January 2015:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, (CENTRAL; Issue 12 of 12, 2014, the Cochrane Library);

MEDLINE (OVID; 1948 to 20 January 2015);

EMBASE (OVID; 1980 to 20 January 2015);

Web of Science (ISI) (SCI‐EXPANDED & CPCI‐S) to 20 January 2015;

BIOSIS (ISI) (1969 to 20 January 2015).

We have listed the electronic search strategies in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We checked the bibliographic references of identified studies, as well as relevant studies and systematic reviews in order to find additional trials not identified by the electronic searches. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/), the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct/), the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/) and the Proceedings of the Congress of the European Federation of International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP; via European Journal of Pain Supplements) up to 16 February 2015 as complementary sources for related studies. We contacted authors of the included studies to ask if they knew of any other relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MSH, JH) assessed the titles and abstracts of all the studies identified by the search for potential inclusion. We independently considered the full records of all potentially relevant studies for inclusion by applying the selection criteria outlined in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. We resolved potential disagreements by discussion. We did not restrict the inclusion criteria by date, language or publication status (published in full, published as abstract, unpublished).

Data extraction and management

Using a standardised data extraction form, two review authors extracted data pertaining to study design, participant detail (including age, cancer characteristics, previous analgesic medication and setting), interventions (including details about titration) and outcomes. We resolved potential disagreements by discussion. In studies in which only a subgroup of the participants met the inclusion criteria for this review, we only extracted the data on this subgroup provided randomisation was not broken.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of each included study by using the Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). For each study we assessed the risk of bias for the following domains:

Selection bias (study level: random sequence generation, allocation concealment);

Performance bias (outcome level: blinding of patients, blinding of treating personnel);

Detection bias (outcome level: blinding of outcome assessment);

Attrition bias (outcome level: incomplete outcome data);

Reporting bias (study level: selective reporting).

In addition, we included an item that assesses the adequacy of titration. Each of the items from the above domains required a 'low risk', 'high risk' or 'unclear risk' response. We also documented the reasons for each response in accordance with Higgins 2011. We resolved potential disagreements through discussion. In addition to this strategy for 'Risk of bias' assessment in the individual studies, we considered the impact that study size may have on the validity of the results. We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes we extracted the means and standard deviations (SDs), where possible, with the intention of using these to estimate the mean difference (MD) between the treatments along with the 95% confidence interval (CI), if the outcome were measured on the same scale in the studies. Where the outcome was measured on different scales, we intended to report the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs instead when performing meta‐analyses. However, this was not feasible. For dichotomous outcomes we extracted event rates but did not, as planned, calculate risk ratios (RRs) and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB)/number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), again because no meta‐analyses were performed.

Unit of analysis issues

Our plan to deal with any unit‐of‐analysis issues was to consider the patient the unit of analysis. However, if the data reported in any included cross‐over trials could not be otherwise incorporated into the analyses (see Dealing with missing data), we would include them as if the design had been parallel group. Higgins 2011 points out that this approach, while giving rise to unit‐of analysis error, is nevertheless conservative as it results in an under‐weighting of the data. Moreover, if we included cross‐over trial data in this manner we would perform sensitivity analyses assessing the impact of this strategy. However, as we did not perform any meta‐analyses, this strategy was not used.

Dealing with missing data

In cases where data were missing, we contacted the trial authors to request missing data. However, we received no replies. We planned to limit missing data imputation to the imputation of missing SDs if enough information was available from the studies to calculate the SD according to the methods outlined by Higgins 2011. However no missing data were imputed in this manner as no meta‐analyses were performed. We have recorded the drop‐out/missing data rates in the 'Risk of bias' tables under the items on attrition bias, and we addressed the potential effect of the missing data on the results, not in sensitivity analyses as originally planned, but in the Discussion section. Although we aimed to perform intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses, we were unable to do so in all cases as we were unable to perform meta‐analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic, with I2 values > 50% representing substantial heterogeneity in line with Higgins 2011. We aimed to assess potential sources of heterogeneity through subgroup analyses as outlined in Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity. However as we were unable to undertake any meta‐analyses, we did not perform these subgroup analyses.

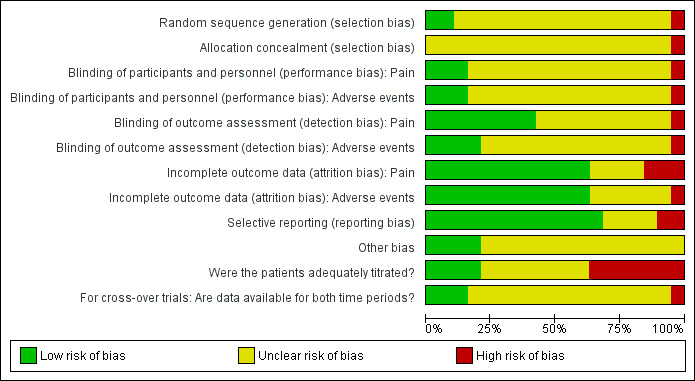

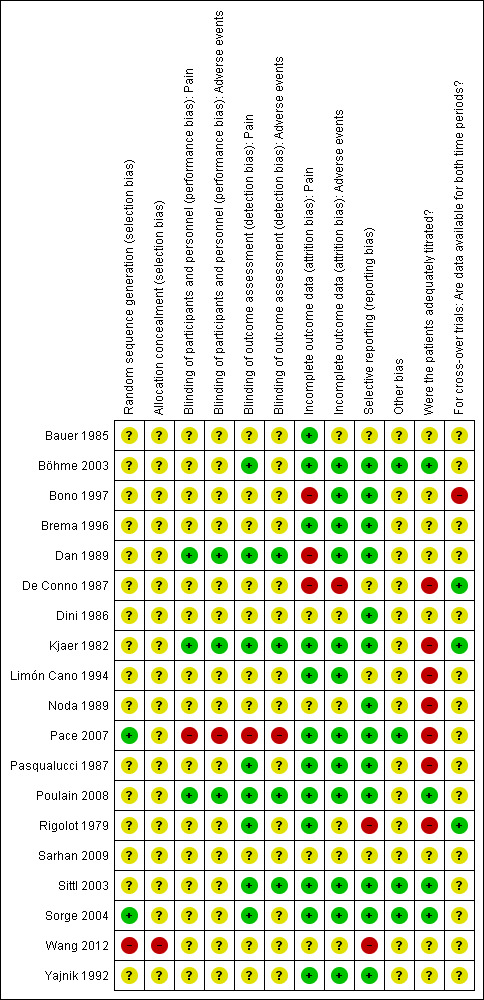

Assessment of reporting biases

In addition to implementing the comprehensive search strategy outlined in the section Search methods for identification of studies, the risk of outcome reporting bias is included in the 'Risk of bias' summary figures (Figure 1; Figure 2) that we constructed for each study and each type of assessed bias.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Data synthesis

We planned to enter the data extracted from the included studies into the Cochrane Collaboration's statistical software, Review Manager 2014, in order to use this for data synthesis. We planned to analyse continuous outcomes using the generic inverse variance method, and dichotomous outcomes using the Mantel‐Haenszel method in accordance with Higgins 2011. If the I2 statistic value was > 50% we planned to use a random‐effects model and consider not reporting a summary estimate of the data (depending on the subgroup analyses; see also the section Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity). Otherwise we would use a fixed‐effect model for the meta‐analyses. However, as it was not feasible to meta‐analyse the data from the included studies, we summarised the data narratively and in tables. We have also, as planned, summarised the results for all the listed outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Different aspects of the trials are likely to contribute heterogeneity to the proposed main analyses. If there were sufficient data, we planned to perform subgroup analyses based on doses, titration, routes of administration (e.g., SL, TD), length of the trials and populations (e.g., opioid‐naive patients, solid/haematological cancer type, adults/children, co‐morbidities). However, there were insufficient data to perform such analyses.

Sensitivity analysis

If sufficient data were available, we aimed:

To examine the robustness of the meta‐analyses by conducting sensitivity analyses using different components of the 'Risk of bias' assessment, particularly those relating to whether allocation concealment and blinding were adequate;

To conduct further sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of missing data on the results if a large proportion of the studies were at an 'unknown' or 'high risk' of attrition bias; and

To perform sensitivity analyses examining whether publication status and trial size influenced the results.

However, we did not perform any sensitivity analyses because there were insufficient data.

Results

Description of studies

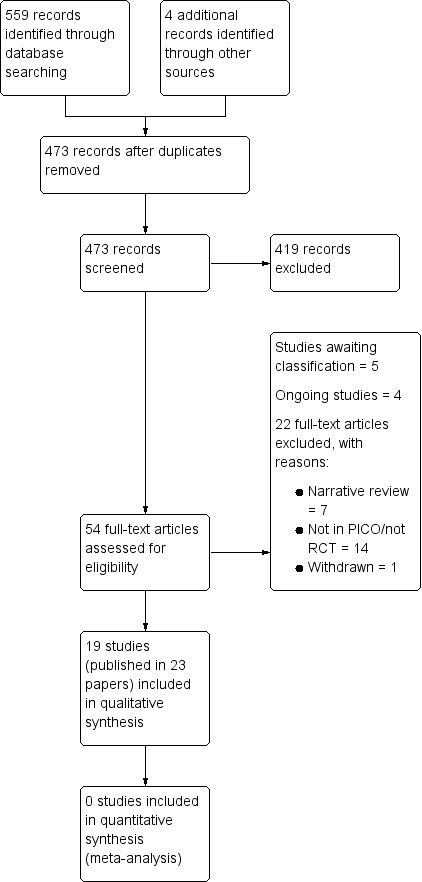

Results of the search

The search identified 473 unique records of which we excluded 419 based on the title/abstract. We retrieved 54 records for full‐text evaluation. Of the 54 records, we included 19 studies published in 23 articles, while we excluded 22 because they were not in PICO (i.e., an RCT conducted in the target population examining the target comparisons as measured by the target outcomes; N = 14), withdrawn (N = 1), or narrative reviews (N = 7) (see Figure 3). In addition to the 19 included studies, we identified four ongoing studies and five potentially relevant studies. We await further information, including study completion and publication, of the latter before we can ascertain their relevance to the current review and classify them accordingly. See also Characteristics of ongoing studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification, respectively.

3.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The 19 included studies were published between 1979 and 2012 and enrolled/randomised a total of 1421 patients (study range 10 to 189) with 1304 (study range 10 to 188) of these analysed for efficacy and 1216 (study range 12 to 189) for safety (Rigolot 1979; Wang 2012 did not report this outcome). The reported mean ages of the patient populations in the studies ranged from 49.1 years to 67.16 years. Four studies were crossover trials (Bono 1997; De Conno 1987; Kjaer 1982; Rigolot 1979) and the remainder were parallel‐group trials, with six studies conducted in Italy (Bono 1997; Brema 1996; De Conno 1987; Dini 1986; Pace 2007; Pasqualucci 1987), two in Japan (Dan 1989; Noda 1989) and in the following countries: Denmark (Kjaer 1982); Germany (Bauer 1985); Austria, Germany and Hungary (Böhme 2003); Mexico (Limón Cano 1994); Austria, Belgium, Croatia, France, Poland and the Netherlands (Poulain 2008); France (Rigolot 1979); Egypt (Sarhan 2009); Austria, Germany and the Netherlands (Sittl 2003); Germany and Poland (Sorge 2004); China (Wang 2012); and India (Yajnik 1992). The treatment groups in the included studies were either comparable at baseline (Dan 1989; Kjaer 1982; Pace 2007; Poulain 2008; Wang 2012; Yajnik 1992), not comparable at baseline (Böhme 2003 (age); Sittl 2003 (age); Sorge 2004 (disease stage)), or it was unclear (e.g., due to lack of reporting of baseline characteristics whether they differed; Bauer 1985 (age); Bono 1997 (baseline pain); Brema 1996 (gender); De Conno 1987; Dini 1986; Limón Cano 1994 (age, gender); Noda 1989 (cancer type and stage); Pasqualucci 1987; Rigolot 1979; Sarhan 2009). Three of the studies included patients with pain of a both malignant and non‐malignant origin (Böhme 2003; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004). One of these studies presented some of the results split by pain origin (32.8% of the patients had cancer pain; Sorge 2004). The other two studies did not present the results separately for the patients with cancer pain, but they were still included as the percentage of patients with malignant pain were above 50 in both studies (55% in Böhme 2003; and 77.1% in Sittl 2003). Trial length ranged from single dose treatment to six months, and the studies reported the following comparisons:

SL buprenorphine versus subdermal (SD) buprenorphine injection (Limón Cano 1994);

SL buprenorphine versus oral tilidin + naloxone (Bauer 1985);

SL buprenorphine versus oral tramadol (Bono 1997; Brema 1996);

SL buprenorphine versus SL buprenorphine + oral phenytoin versus oral phenytoin (Yajnik 1992);

SL buprenorphine versus oral pentazocine (De Conno 1987);

Buprenorphine tablets/fluid versus pentazocine tablets/fluid (Dini 1986);

TD buprenorphine versus placebo (Böhme 2003; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004);

TD buprenorphine versus controlled‐release morphine (Pace 2007);

TD buprenorphine versus TD fentanyl (Sarhan 2009);

IM buprenorphine injection versus buprenorphine suppository (Dan 1989);

IM buprenorphine versus IM morphine (Kjaer 1982; Rigolot 1979);

IM buprenorphine + SC buprenorphine versus SC buprenorphine versus placebo + SC buprenorphine (Noda 1989);

Epidural buprenorphine versus epidural morphine (Pasqualucci 1987);

Intravenous buprenorphine versus intravenous morphine (Wang 2012).

See also Characteristics of included studies for further details about the studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 22 studies because they were not in PICO (i.e., an RCT conducted in the target population examining the target comparisons as measured by the target outcomes; N = 14), withdrawn (N = 1), or narrative reviews (N = 7). One of the studies identified in the search compared buprenorphine in combination with diclofenac against buprenorphine alone (Corli 1988). We excluded this study as it would not answer our primary question which is concerned with the effectiveness of buprenorphine for cancer pain. See also Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

In this section we have described the risk of bias for the included studies. See also Figure 1 and Figure 2 for summaries of the risk of bias judgements.

Allocation

We considered generation of the randomisation sequence to be at low risk of bias in only two included trials (Pace 2007; Sorge 2004). A third study was considered to be at high risk of selection bias because it included only 120 patients that were allocated to one of four treatment groups with stratification for several factors. With each stratification factor it became increasingly conceivable that the group allocation ceased to be truly random or, indeed, concealed given the relatively high number of treatment groups to the relatively low number of patients (Wang 2012). The remaining included studies did not report enough information to enable us to assess the risk of selection bias. Therefore we considered them at unclear risk of selection bias.

Blinding

Lack of reporting was also an issue when assigning risk of bias estimates to the items assessing performance and detection bias, i.e., blinding. Very few trials reported directly who was blinded, so in most cases we inferred on the basis of supplementary information whether we were reasonably certain that blinding had been adequately executed for a given individual (i.e., patient, treating personnel or the outcome assessors, or both, where not the patients themselves). On this basis, we considered the risk of performance bias to be low for the primary outcome of pain and for the secondary outcome of adverse events in three studies (Dan 1989; Kjaer 1982; Poulain 2008), high in one study described as open label (Pace 2007) and unclear in the remaining 13 studies that reported this outcome. We considered eight studies at low risk of detection bias for pain (which according to our criteria had to be patient‐assessed) either because it was clearly stated that the patient was blinded (Dan 1989; Kjaer 1982; Poulain 2008; Rigolot 1979 (although in this study it is not clear whether pain is patient‐assessed)) or because the study was described as double‐blind without stating who was blinded (i.e., patient, treating personnel or outcome assessor) and we considered it sufficiently likely that at least the patient was blinded (Böhme 2003; Pasqualucci 1987; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004; see also Characteristics of included studies). Apart from Pace 2007, judged at high risk due to being open label, we judged the remaining studies to be at unclear risk of detection bias for the outcome of pain. In the case of adverse events, it was often unclear who reported/assessed this outcome. Therefore we felt unable to assume with sufficient confidence that it had be assessed in a blinded manner (unlike with pain as described above), unless it had been clearly stated. We considered the risk of detection bias for adverse events to below in four studies that all clearly stated that the outcome assessor was blinded (Dan 1989; Kjaer 1982; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003), high in one open label study (Pace 2007) and unclear in the remaining 12 studies reporting this outcome.

Incomplete outcome data

Overall the data from 91.8% of the total number of enrolled/randomised patients were analysed for pain. We judged the risk of attrition bias as low in most included studies (Bauer 1985; Böhme 2003; Brema 1996; Kjaer 1982; Limón Cano 1994; Pace 2007; Pasqualucci 1987; Poulain 2008; Rigolot 1979; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004; Yajnik 1992), with three studies considered at high risk (Bono 1997; Dan 1989; De Conno 1987) and four studies considered at unclear risk (Dini 1986; Noda 1989; Sarhan 2009; Wang 2012) of attrition bias, respectively. For adverse events, we analysed the data from 85.6% of the total number of enrolled/randomised patients, and we considered the risk of attrition bias to be low in 12 included studies (Böhme 2003; Bono 1997; Brema 1996; Dan 1989; Kjaer 1982; Limón Cano 1994; Pace 2007; Pasqualucci 1987; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004; Yajnik 1992), high in one study (De Conno 1987) and unclear in the remaining four studies (Bauer 1985; Dini 1986; Noda 1989; Sarhan 2009) that reported this outcome. Rigolot 1979 and Wang 2012 did not report adverse events.

Selective reporting

We considered 13 included studies to be at low risk of reporting bias, with Rigolot 1979 and Wang 2012 considered at high risk of reporting bias as neither reported adverse events. We judged the remaining four studies (Bauer 1985; De Conno 1987; Limón Cano 1994; Sarhan 2009) at unclear risk of reporting bias due to under‐reporting from being available either only in abstract form or in a foreign language.

Other potential sources of bias

Patients appeared to be adequately titrated in only four studies (Böhme 2003; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004), and inadequately or not titrated in a further seven studies (De Conno 1987; Kjaer 1982; Limón Cano 1994; Noda 1989; Pace 2007; Pasqualucci 1987; Rigolot 1979). Titration schedule or adequacy, or both, was unclear in the remaining eight studies.

Apart from five studies which reported to have received commercial funding (Böhme 2003; Kjaer 1982; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004), it was unclear whether the remaining studies received such funding.

Data were available for both cross‐over phases for three of the four crossover trials included (De Conno 1987; Kjaer 1982; Rigolot 1979). We considered these trials to be at low risk of bias, whereas we judged the final trial (Bono 1997) to be at high risk of bias because the pain intensity data did not appear to be inferentially analysed collapsed over phases for any of the seven (per phase) study days, apart from for the first four hours of treatment.

Nine included studies appeared to conduct the analyses according to the ITT principle (Bauer 1985; Brema 1996; Kjaer 1982; Limón Cano 1994; Pace 2007; Pasqualucci 1987; Poulain 2008; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004), although this was often not clearly stated. In the remaining studies it was either unclear if ITT analyses were performed (Böhme 2003; Dini 1986; Noda 1989; Rigolot 1979; Sarhan 2009; Wang 2012; Yajnik 1992) or they were clearly not performed (Bono 1997; Dan 1989; De Conno 1987).

With the exception of four studies (Böhme 2003; Pace 2007; Sittl 2003; Sorge 2004) which we judged at low risk of 'other bias', for most included studies we were unable to evaluate with sufficient confidence whether they were subject to other kinds of bias due to the very limited reporting that this body of evidence generally suffered from (Bauer 1985; Bono 1997; Brema 1996; Dan 1989; De Conno 1987; Dini 1986; Kjaer 1982; Limón Cano 1994; Noda 1989; Pasqualucci 1987; Poulain 2008; Rigolot 1979; Sarhan 2009; Wang 2012; Yajnik 1992).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

SL buprenorphine versus SD buprenorphine

Limón Cano 1994 conducted a placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group study of (it seems) 24‐hour duration comparing SL buprenorphine (N = 10) to SD buprenorphine (N = 7) administered every four to eight hours on a patient‐need basis. Both treatments resulted in a 50% reduction in pain intensity, with faster onset of pain relief observed in the SL group (63 ± 22.1 min) compared to the subdermic group (94.3 ± 22.7 min). The mean duration of analgesia was similar between the SL (7.4 ± 1.2 hours) and the SD (6.8 ± 1.2 hours; P > 0.2) groups, and no significant differences in adverse event rates were reported (see also Table 2).

1. SL buprenorphine comparisons: Adverse events.

| AE | SL Bup versus SD Bup | SL Bup versus oral tilidin‐HCI + naloxone‐HCI | SL Bup versus oral Tra | SL Bup versus SL Bup + oral P versus oral P | SL Bup versus oral Pen | Bup tablets/fluid versus Pen Tab/F | |||||||||||

| Limón Cano 1994 | Bauer 1985 | Bono 1997 | Brema 1996 | Yajnik 1992 | De Conno 1987a | Dini 1986 | |||||||||||

| SL bup | SD bup | SL bup | Til+Na | SL bup | Tra | SL bup | Tra | Bup | Bup + P | P | SL bup | Pen | Bup tablets | Bup fluid | Pen tablets | Pen fluid | |

| Any AEs | 34/60 | 9/60 | 16/63 | 17/68 | 13/25 | 5/25 | 2/25 | 18% | 50% | ||||||||

| Total AEs | 49 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Abdominal pain | 0.6 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Acidity | 0.5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Agitation | 2 | 2.4 | 0/11 | 0/11 | 0/10 | 2/10 | |||||||||||

| Allergy | 0.1 | 0.2 | |||||||||||||||

| Anorexia/appetite loss | 1/60 | 0/60 | |||||||||||||||

| Blood loss | 0.1 | 0.1 | |||||||||||||||

| Bradycardia | 3/25 | 1/25 | 0/25 | ||||||||||||||

| Confusion | 0/11 | 0/11 | 0/10 | 1/10 | |||||||||||||

| Constipation | Bup = Til+Na | 4/60 | 2/60 | 3/63 | 4/68 | ||||||||||||

| Dizziness/confusion | 6/60 | 1/60 | 3/63 | 4/68 | 1.1 | 2 | |||||||||||

| Drowsiness/somnolence | 14/60 | 5/60 | 5/63 | 7/68 | 4/25 | 1/25 | 0/25 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 0/11 | 2/11 | 3/10 | 1/10 | ||||

| Dry mouth | 1/60 | 0/60 | 2.8 | 2.6 | |||||||||||||

| Fatigue | Bup = Til+Na | ||||||||||||||||

| Giddiness | 0/25 | 0/25 | 1/25 | ||||||||||||||

| Hallucinations | 3/10 | 5/7 | 1/60 | 0/60 | |||||||||||||

| Headache | 0/25 | 0/25 | 1/25 | 0.9 | 1.1 | ||||||||||||

| Heartburn | 0.6 | 0.9 | |||||||||||||||

| Heavy head | 1/60 | 0/60 | |||||||||||||||

| Hiccup | 1/60 | 0/60 | |||||||||||||||

| Hypotension | 1/25 | 1/25 | 0/25 | ||||||||||||||

| Irritability | 1/60 | 0/60 | |||||||||||||||

| Nausea | Bup = Til+Na | 8/60 | 0/60 | 7/63 | 8/68 | 1.4 | 1.6 | ||||||||||

| Nausea and vomiting | SL = SD | SL = SD | 6/60 | 0/60 | 2/25 | 1/25 | 0/25 | ||||||||||

| Pruritus | 1.1 | 0.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Respiratory depression | 1/10 | 1/7 | 3/25 | 1/25 | 0/25 | ||||||||||||

| Sedation | SL = SD | SL = SD | |||||||||||||||

| Sweating | 1/60 | 0/60 | 2.4 | 2.1 | |||||||||||||

| Thirst | |||||||||||||||||

| Tremors | 1.1 | 1.7 | |||||||||||||||

| Vomiting | Bup = Til+Na | 6/60 | 1/60 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 2/11 | 2/11 | 2/10 | 0/10 | ||||||||

| Discontinuation due to AE | 0 | 0 | 19/60 | 2/60 | 7/63 | 6/68 | |||||||||||

Abbreviations: AE = adverse events; SL = sublingual; SD = subdermal; Bup = buprenorphine; P = phenytoin; Pen = pentazocine; SC = subcutaneous; SD = subdermal; SL = sublingual; Tab = tablets; Til+Na = tilidin + naloxone; Tra = tramadol; F = fluid. aAverage.

SL buprenorphine versus oral tilidine‐HCI + naloxone‐HCI

Bauer 1985 conducted a parallel‐group, 28‐day study with 20 women in each group comparing SL buprenorphine to oral tilidine with naloxone. This study found that the pain intensity ratings, which were comparable at baseline (7.16 for buprenorphine versus 7.11 for tilidine + naloxone), were significantly lower for the patients who received buprenorphine on days 1 (4.31 for buprenorphine versus 4.97 for tilidine + naloxone), 7 (3.43 for buprenorphine versus 4.58 for tilidine + naloxone), 14 (3.83 for buprenorphine versus 4.54 for tilidine + naloxone) and 21 (4.06 for buprenorphine versus 4.56 for tilidine + naloxone), but not on day 28, where it was only numerically lower (4.07 for buprenorphine versus 4.42 for tilidine + naloxone). The mean number of drug administrations necessary to achieve satisfactory analgesia was 39 (range = 26 to 52) in the buprenorphine group and 60 (range = 36 to 104) in the tilidine + naloxone group over the 28‐day study period (P < 0.05). The mean interval between drug administrations was 17.6 (range = 12.8 to 25.5) hours in the buprenorphine group and 11.85 (range = 6.4 to 17.7) hours in the tilidine + naloxone group (P < 0.05). The trial authors reported that there did not seem to be any detectable increase in analgesic requirements due to tachyphylaxis for any of the drugs, and all the patients in both treatment groups described the analgesic effectiveness as satisfactory. Treatment‐related side effects such as nausea, vomiting and fatigue, and constipation occurred with the same frequency in both groups, and led to no cases of discontinuation of treatment (see also Table 2).

SL buprenorphine versus oral tramadol

Bono 1997 undertook a cross‐over study with two phases, each lasting 7 days, comparing SL buprenorphine to oral tramadol in 60 patients. The pain intensity data did not appear to be inferentially analysed where it was collapsed over phases for (any of) the study days, apart from for the first four hours of treatment, where no differences were observed between the treatments. Other analyses that appeared to include all patients collapsed across phases showed:

Ratings of pain intensity relative to the pain intensity experienced the previous day did not differ significantly between the treatment groups;

Tramadol treatment was associated with significantly better quality of sleep than buprenorphine on days 6 and 7, but not on days one to five where no differences were observed;

Significantly better patient ratings of tolerability (mean = 80.1, SEM = 2.3) compared to buprenorphine (mean = 41.8, SEM = 4.1);

The number of patients with side effects was also lower during tramadol (9/60 patients) than buprenorphine treatment (34/60 patients; see also Table 2).

In a parallel‐group trial planned to last up to six months, Brema 1996 compared SL buprenorphine (N = 63) to slow‐release tramadol (N = 68). The mean duration of treatment was 50.9 days in the buprenorphine group and 57.7 days in the tramadol group. One patient in the buprenorphine group and four patients in the tramadol group completed the six months of treatment. At baseline, 92% buprenorphine and 98.4% tramadol patients reported 'strong‐to‐unbearable' pain, which reduced to 66.7% and 48.4% respectively at seven days and to 54.5% and 43.1%, respectively, at day 14. These percentages differed statistically significantly at day 7, but this significance had disappeared by day 14, and may have been a result of quicker titration with tramadol than buprenorphine in the early stage of the study. No significant differences in the percentage of patients reporting good deep sleep were observed between the buprenorphine and tramadol patients at baseline (buprenorphine 32.7%, tramadol 37.2%), day 7 (buprenorphine 40%, tramadol 51.1%) or day 14 (buprenorphine 43.9%, tramadol 50%). After two weeks of treatment the overall treatment efficacy was rated as higher in the tramadol (mean 100‐mm VAS = 62.3, SD = 26.7) than in the buprenorphine (mean 100‐mm VAS = 57.2, SD = 25.6) group although not significantly so. This was also the case at the end of treatment and at this stage the difference may have become significant although this cannot be ascertained based on the reported results (tramadol: mean 100‐mm VAS = 60.9, SD = 27.8; buprenorphine: mean 100‐mm VAS = 47.4, SD = 26; P ≤ 0.05). After two weeks of treatment the overall treatment acceptability was rated as significantly higher in the tramadol (mean 100‐mm VAS = 70.7, SD = 19.8) than in the buprenorphine (mean 100‐mm VAS = 58.9, SD = 24.5) group. This was also the case at the end of treatment, although it is apparently only marginally significantly higher at this stage (tramadol: mean 100‐mm VAS = 69.2, SD = 19.1; buprenorphine: mean 100‐mm VAS = 58.3, SD = 22.9; P ≤ 0.05). The trial authors also reported that in the tramadol group 71.4% of the patients reported moderate/no pain in the first month and 80% did so in the second month, with the corresponding percentages for the buprenorphine group at 45.4% after one month and 65.2% after two months, but reported no inferential statistics. We have listed the adverse events in Table 2.

SL buprenorphine versus SL buprenorphine + oral phenytoin versus oral phenytoin

Yajnik 1992 conducted a parallel‐group trial of one month duration comparing treatment with SL buprenorphine, with SL buprenorphine + oral phenytoin and with phenytoin in three groups of 25 patients, and found no significant difference in pain relief rates after one month between the buprenorphine (good: 15/25; moderate: 6/25; poor: 4/25; none: 0/25), the buprenorphine + phenytoin (good: 18/25; moderate: 4/25; poor: 2/25; none: 1/25) and phenytoin (good: 4/25; moderate: 14/25; poor: 5/25; none: 2/25) groups. The groups did not differ significantly in incidence of adverse events (see Table 2).

SL buprenorphine versus oral pentazocine

De Conno 1987 compared SL buprenorphine with oral pentazocine in a cross‐over study lasting 14 days (seven days per phase) in 120 patients, of whom 29 did not complete the study. This study found that buprenorphine was associated with significantly better pain relief compared to pentazocine, reducing the mean daily pain intensity 10 to 25 points more than pentazocine. Patients also slept statistically significantly more (on average one hour) during treatment with buprenorphine compared to treatment with pentazocine. Also, they spent 10 to 30 minutes longer a day standing during the buprenorphine treatment phase than pentazocine treatment, although it is unclear whether this difference is statistically significant. Buprenorphine was associated with significantly more drowsiness, whereas pentazocine was associated with significantly more dizziness and stomach pain. Otherwise the side effects profiles did not differ significantly between the treatments (see also Table 2). Of the 29 patients who did not complete the study, more patients stopped study treatment during the pentazocine phase (N = 16) than during the buprenorphine phase (N = 3; P = 0.03).

Buprenorphine tablets/fluid versus pentazocine tablets/fluid

Dini 1986 conducted a parallel‐group study with four experimental groups (buprenorphine SL tablets and vials, pentazocine tablets and vials) of seven days duration with a total of 42 patients, of whom two (one each treated with buprenorphine and pentazocine tablets) did not complete the course of therapy due to excessive nausea and vomiting. Dini 1986 reported that the final daily average pain intensity was significantly lower after treatment with buprenorphine tablets (mean = 58, SE = 19) compared to pentazocine tablets (mean = 118, SE = 23). This pattern of results was also observed when comparing treatment with buprenorphine vials/fluid (mean = 38, SE = 9) and pentazocine vials/fluid (mean = 115, SE = 15). Treatment with buprenorphine vials/fluid was associated with a longer time spent asleep (mean = 8 hours, SE = 0.6 hours) relative to pentazocine vials/fluid (mean = 6.5 hours, SE = 0.4 hours). However, this effect was not observed after treatment with the tablet forms of buprenorphine (mean = 7.2 hours, SE = 0.6 hours) and pentazocine (mean = 7 hours, SE = 0.6 hours), which did not differ statistically significantly. No differences were observed either in time spent awake in the supine position between treatment with buprenorphine vials/fluid (mean = 15 hours, SE = 1.8 hours) and pentazocine vials/fluid (mean = 17 hours, SE = 2.1 hours) or between treatment with buprenorphine tablets (mean = 13.5 hours, SE = 2.2 hours) and pentazocine tablets (mean = 11.9 hours, SE = 2.1 hours). No differences were observed between the treatment groups in time spent sitting or standing either. The trial authors did not report any formal statistical comparisons for the patient ratings of treatment effectiveness and tolerability, which are therefore only reported descriptively: patients rated effectiveness of treatment after treatment with buprenorphine tablets as excellent (three patients), good (six patients) and fair (one patient); as good (one patient), fair (one patient), poor (six patients) and nothing (two patients) after treatment with pentazocine tablets; as excellent (three patients), good (seven patients) and fair (one patient) after treatment with buprenorphine vials/fluid; and as good (two patients), fair (five patients) and poor (three patients) after treatment with pentazocine vials/fluid. Patients rated tolerability of treatment after treatment with buprenorphine tablets as excellent (9 patients), good (one patient) and poor (one patient); as good (two patients), fair (four patients), and poor (four patients) after treatment with pentazocine tablets; as excellent (five patients), good (five patients) and fair (one patient) after treatment with buprenorphine vials/fluid; and as excellent (one patient), good (six patients), fair (one patient) and poor (two patients) after treatment with pentazocine vials/fluid. We have reported adverse events in Table 2.

TD buprenorphine versus placebo

Böhme 2003 is a six day, four‐arm, parallel‐group trial that included patients with pain from both malignant (55%) and non‐malignant (45%) origin and compared placebo (N = 37) to TD buprenorphine at three different doses, 35 μg/h (N = 35), 52.5 μg/h (N = 41) and 70 μg/h (N = 38). Böhme 2003 found that the number of patients who responded to treatment (i.e., patients who obtained at least satisfactory pain relief at all determination points (excluding the final examination) and who took a mean of 0.2 mg/day or less of SL buprenorphine on days seven to 12) and the mean daily doses of rescue medication (SL buprenorphine) did not differ significantly between the four groups. No significant differences in rates of adverse events were observed between the groups (see Table 3).

2. Transdermal buprenorphine comparisons: Adverse events.

| AE | TD Bup versus placebo | TD Bup versus controlled‐release Mor | TD Bup versus TD Fen | |||||||||||||

| Böhme 2003 | Poulain 2008 | Sittl 2003 | Sorge 2004 | Pace 2007 | Sarhan 2009 | |||||||||||

| Placebo | 35 μg/h Bup | 52.5 μg/h Bup | 70 μg/h Bup | Placebo | 70 μg/h Bup | Placebo | 35 μg/h Bup | 52.5 μg/h Bup | 70 μg/h Bup | Placebo | 35 μg/h Bup | TD Bup | CR Mor | TD Bup | TD Fen | |

| At least one AE | 28/38 | 35/41 | 33/41 | 28/37 | ||||||||||||

| Asthenia | 1/95 | 4/94 | ||||||||||||||

| Central nervous system AE | 20/38 | 23/41 | 19/41 | 20/37 | ||||||||||||

| Confusion | 1/26 | 1/26 | ||||||||||||||

| Constipation | 2/95 | 9/94 | 2/26 | 10/26 | ||||||||||||

| Dizziness/confusion | 0/95 | 0/94 | ||||||||||||||

| Drowsiness/somnolence | 3/26 | 2/26 | Bup > Fen | Bup > Fen | ||||||||||||

| Erythema | 7/38 | 12/41 | 12/41 | 12/37 | 0/19a | 0/26a | ||||||||||

| Exanthema | 0/37a | 0/35a | 1/41a | 0/38a | 1/38 | 5/41 | 5/41 | 1/37 | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 2/95 | 0/94 | ||||||||||||||

| Gastrointestinal AE | 26.30% | 17.10% | 36.60% | 43.20% | ||||||||||||

| Headache | 3/26 | 4/26 | ||||||||||||||

| Nausea | 7/95 | 3/94 | 3/26 | 9/26 | ||||||||||||

| Pruritus | 0/37a | 0/35a | 3/41a | 1/38a | 9/38 | 10/41 | 11/41 | 9/37 | 0/19a | 0/26a | ||||||

| Skin complication, local | Bup > Fen | Bup > Fen | ||||||||||||||

| Swelling, non‐inflammatory | 1/38 | 1/41 | 0/41 | 0/37 | ||||||||||||

| Vertigo | 3/26 | 11/26 | ||||||||||||||

| Vomiting | 6/95 | 5/94 | ||||||||||||||

| Discontinuation due to AE | 6/95 | 1/94 | 6/38 | 3/41 | 5/41 | 3/37 | ||||||||||

Abbreviations: Bup = buprenorphine; F = fluid; Fen = fentanyl; IM = intramuscular; Mor = morphine; P = phenytoin; Pen = pentazocine; Pla = placebo; SC = subcutaneous; SD = subdermal; SL = sublingual; Sup = suppository; Tab = tablets; Til+Na = tilidin + naloxone; Tra = tramadol. aSevere.

In a study similar to Böhme 2003, Sittl 2003 conducted a 15‐day long parallel group trial in 157 patients with both malignant (77.1%) and non‐malignant (22.9%) pain comparing placebo (N = 38) to TD buprenorphine at three different doses, 35 μg/h (N = 41), 52.5 μg/h (N = 41) and 70 μg/h (N = 37). Sittl 2003 found that the two lower doses of buprenorphine (35 μg/h: 36.6%; 52.5 μg/h: 47.5%; 70 μg/h: 33.3%) were found to have a significantly higher percentage of responders (i.e., patients requiring no more than one SL tablet of buprenorphine (rescue medication) per day from day 2 until the end of the study and who recorded at least satisfactory pain relief at each application of a new patch) than placebo (16.2%). The percentage reduction in mean daily dose of rescue medication relative to pre‐study was also significantly larger in all the buprenorphine treatment groups (35 μg/h: ‐56.9%; 52.5 μg/h: ‐61.6%; 70 μg/h: ‐51.6%) compared to placebo (‐8%), but did not differ significantly from each other. The mean overall ratings of pain relief were also higher in the buprenorphine groups (35 μg/h: 2.3/4; 52.5 μg/h: 2.4/4; 70 μg/h: 2.5/4) than in the placebo group (1.9/4), but it is unclear if they are significantly so. Moreover, 8/37 (placebo), 9/41 (35 μg/h), 15/40 (52.5 μg/h) and 8/37 (70 μg/h) patients, respectively, rated their pain relief as satisfactory over the course of the study, with a further 12/37 (placebo), 19/41 (35 μg/h), 16/40 (52.5 μg/h) and 16/36 (70 μg/h) patients, respectively, rating their pain relief as good or complete. The mean ratings of daily pain intensity were 'moderate‐very severe' in 60% (placebo), 52% (35 μg/h), 40% (52.5 μg/h) and 37% (70 μg/h) patients, respectively; 'mild' in 31% (placebo), 29% (35 μg/h), 42% (52.5 μg/h) and 43% (70 μg/h) patients, respectively, and 'none' in 9% (placebo), 19% (35 μg/h), 18% (52.5 μg/h) and 20% (70 μg/h) patients, respectively (no inferential statistical analyses reported). The incidence of none of the reported adverse events differed significantly between the four treatment groups (see Table 3 for the reported adverse events).

Another parallel‐group study of two weeks duration, Poulain 2008, compared placebo (N = 95) to 70 μg/h TD buprenorphine (N = 94) and found that the proportion of responders (i.e., patients with a mean pain intensity < five during the last six days of the maintenance phase and a mean daily SL buprenorphine (rescue medication) intake ≤ 2 tablets over the entire maintenance phase) was significantly higher in the buprenorphine group (70/94) compared to the placebo group (47/94). The baseline‐corrected pain intensity and rescue medication tablet intake at the end of the two‐week maintenance phase were also significantly lower in the buprenorphine group (pain intensity: least square mean = 0.23, SE = 0.15; rescue medication tablet intake: least square mean = ‐0.76, SE = 0.14) than in the placebo group (pain intensity: least square mean = 1.14, SE = 0.17; rescue medication tablet intake: least square mean = ‐0.23, SE = 0.15). Also, 51/94 buprenorphine patients and 39/94 placebo patients rated their global satisfaction with treatment as 'excellent' or 'very good' with a further 32 and 33 patients, respectively, giving 'good' or 'fair' ratings and nine buprenorphine patients and 19 placebo patients giving a rating of 'poor' (see Table 3 for the reported adverse events).

Sorge 2004 is a nine‐day, parallel‐group trial that included patients with pain of both malignant (N = 45) and non‐malignant origin (N = 92), but presented some of the results by pain origin (of which only those relating to malignant pain are included here). Sorge 2004 compared placebo (N = 19) to 35 μg/h TD buprenorphine (N = 26). This study found that the mean (SD) daily requirement for SL buprenorphine (rescue medication) tablets was 1.2 (0.3) in the run‐in phase and 0.4 (0.5) in the double‐blind phase for the buprenorphine group and 1 (0.2) and 0.6 (0.3), respectively, in the placebo group. No inferential statistics and no further efficacy results were reported separately for the patients with cancer pain (see Table 3 for the reported adverse events).

TD buprenorphine versus controlled‐release morphine

Pace 2007 compared TD buprenorphine to controlled‐release morphine in an eight‐week long parallel‐group trial with 26 patients in each arm. Pace 2007 found that buprenorphine was associated with significantly lower pain scores from week 2 of treatment and with less interference with sleep from week 1 of treatment as well as with higher quality of life in terms of 'physical pain', 'mental health' and 'vitality', with significant differences between the groups on the quality of life items of 'physical activity', 'limited activity due to physical problems', 'social activity', 'limited activity due to emotional problems' and 'problems of general health'. The study also showed that buprenorphine treatment was associated with lower anger/aversion, fatigue/inertia and total mood disorder scores and significantly higher strength/activity scores than morphine. Twenty‐five of the 26 buprenorphine patients and 19 of the 26 morphine patients indicated that their global impression of change was 'moderately better' or 'considerable improvement'. Eleven buprenorphine patients and 16 morphine patients needed supplemental analgesia with tramadol, with seven and nine buprenorphine and morphine patients, respectively, needing 100 mg tramadol and the remainder needing 200 mg tramadol. The morphine patients had significantly higher rates of vertigo, constipation and nausea, but no differences were observed between the groups in rates of drowsiness, headache and confusion (see Table 3).

TD buprenorphine versus TD fentanyl

In a parallel‐group study lasting six weeks, Sarhan 2009 compared escalating doses of TD buprenorphine (N = 16) and TD fentanyl (N = 16). Sarhan 2009 reported that the only significant differences that this study revealed were that buprenorphine was associated with significantly higher rates of drowsiness and local skin complications compared to fentanyl. The mean pain scores, mean number of each category patch dose, treatment satisfaction, mean daily dose of diclofenac sodium, mean cost of the treatment and other side effects and complications did not differ significantly between the groups during the six weeks (see Table 3).

IM buprenorphine versus buprenorphine suppository

Dan 1989 is a parallel‐group study consisting of two consecutive treatments six to eight hours apart of the study drugs. Dan 1989 found that after the first administration of buprenorphine, the number of people who rated their pain intensity as "none" or "little" changed from 0 out of 34 patients at baseline to 23, 24 and 19 patients at 2, 4 and 6 hours in the rectal buprenorphine group and to 27, 30, and 28 (out of 35) patients, respectively, in the IM buprenorphine group. Before the second administration of the study drugs, 18 and 19 patients in the rectal and IM buprenorphine groups, respectively, described their pain intensity as "none" or "little". This changed to 26, 26 and 24 (out of 33) patients in the rectal buprenorphine group and to 22, 22, 22 (out of 28) patients in the IM buprenorphine group at 2, 4 and 6 hours after the second drug administration. Pain intensity ratings did not differ significantly between the groups at any point. Only one patient rated their pain intensity as "severe" after either the first (at two and six hours, and just before the second administration) or after the second (six hours) study drug administration (of IM buprenorphine). The overall ratings of pain relief at study end showed that most patients rated the drugs as "effective" (32 out of 34 rectal buprenorphine patients and 31 out of 34 IM buprenorphine patients) with the remaining patients rating the drugs as "minor response" and no patients giving a rating of "ineffective" with no statistically significant differences between the groups observed. While the severity of drowsiness, feeling heavy‐headed, sweating, thirst, urinary retention, euphoria and fatigue did not differ significantly between the groups, Dan 1989 found that the average severity of dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and adverse events as a total were all significantly higher in the IM group relatively to the suppository group (see Table 4).

3. Single study comparisons: Adverse events.

| AE | IM Bup versus Bup Sup | IM Bup versus IM Mor | IM Bup + SC Bup versus SC Bup versus placebo + SC Bup | Epi Bup versus Epi Mor | |||||

| Dan 1989a | Kjaer 1982 | Noda 1989 | Pasqualucci 1987 | ||||||

| IM Bup | Sup Bup | IM Bup | IM Mor | IM + SC Bup | SC Bup | Placebo + SC Bup | Epi Bup | Epi Mor | |

| Local toxicity/abnormal effect at injection/infusion site | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Total AEs | 21.80 ± 3.67 | 11.41 ± 1.75 | 80 | 54 | |||||

| Anorexia/appetite loss | 9/31 | 8.5/32.5 | |||||||

| Anxiety | 1/26 | 0/26 | |||||||

| Blurred vision | 3/26 | 0/26 | |||||||

| Chest pain | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Decreased memory | 1/26 | 2/26 | |||||||

| Deep respiration | 1/26 | 0/26 | |||||||

| Depression | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Dizziness/confusion | 1.63 ± 0.53 | 0.24 ± 0.09 | 18/26 | 7/26 | 2/6 | 0/6 | |||

| Drowsiness/somnolence | 5.29 ± 0.8 | 3.44 ± 0.56 | 0/10 | 2/10 | 1/10 | 1/6 | 0/6 | ||

| Drunken feeling | 1/26 | 0/26 | |||||||

| Eruption | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Euphoria | 2.09 ± 0.54 | 2.09 ± 0.56 | 5/26 | 5/26 | |||||

| Fatigue | 0.69 ± 0.43 | 0.26 ± 0.17 | 1/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||

| Hallucinations | 0/10 | 0/10 | 1/10 | ||||||

| Headache | 2/26 | 1/26 | |||||||

| Heavy head | 1.83 ± 0.53 | 0.91 ± 0.31 | |||||||

| Hypotension | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Nausea | 2.89 ± 0.63 | 1.29 ± 0.43 | 11/26 | 4/26 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 2/10 | 3/6 | 1/6 |

| Numbness, hand and feet | 0/26 | 1/26 | |||||||

| Palpitation | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Pruritus | 0/10 | 0/10 | 1/10 | 0/6b | 2/6b | ||||

| Remote feeling | 0/26 | 1/26 | |||||||

| Respiratory depression | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||||

| Sedation | 14/26 | 18/26 | |||||||

| Sweating | 1.31 ± 0.47 | 0.79 ± 0.32 | 10/26 | 3/26 | |||||

| Thirst | 1.94 ± 0.53 | 0.71 ± 0.24 | 2/26 | 7/26 | |||||

| Urinary retention | 1.94 ± 0.72 | 0.91 ± 0.41 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | ||||

| Vertigo | 0/10 | 0/10 | 3/10 | ||||||

| Vomiting | 2.20 ± 0.53 | 0.68 ± 0.21 | 11/26 | 5/26 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 1/10 | 2/6 | 1/6 |

| Discontinuation due to AE | 7/35 | 1/34 | |||||||

Abbreviations: Bup = buprenorphine; Fen = fentanyl; IM = intramuscular; Epi = epidural; Mor = morphine; SC = subcutaneous; SD = subdermal; SL = sublingual; Sup = suppository; Tab = tablets; Til+Na = tilidin + naloxone; Tra = tramadol. aAverage. bOf the face.

IM buprenorphine versus IM morphine

In a crossover study lasting a total of eight days Rigolot 1979 compared IM buprenorphine to IM morphine in 10 patients. Rigolot 1979 reported that, when analysed separately, both morphine and buprenorphine are associated with significantly lower pain intensities at hours one to five compared to baseline. When compared directly, no significant differences were observed between the two treatments in analgesic efficacy at any of the measured times. Rigolot 1979 did not report adverse events.

Kjaer 1982 conducted a cross‐over study with 27 patients comparing single IM doses of buprenorphine and morphine, and found no differences in 'maximum pain intensity difference' between the groups. However the 'total pain relief scores' were significantly greater after buprenorphine treatment than morphine treatment, and the time to re‐medication was significantly longer after buprenorphine (mean = 10 hours) than after morphine (mean = eight hours) treatment. There were no differences between the treatments in severity, onset and duration of euphoria, sweating, blurred vision, thirst, sedation, deep respiration, decreased memory, numbness of hands and feet, headache, anxiety, feeling intoxicated and feeling remote. However, dizziness, nausea and vomiting were more severe, had earlier onset and longer duration after treatment with buprenorphine compared to morphine (see Table 4).

IM buprenorphine + SC buprenorphine versus SC buprenorphine versus placebo + SC buprenorphine

In a parallel‐group trial lasting 48 hours, Noda 1989 compared SC buprenorphine (4 μg/kg/day) preceded by an IM injection of buprenorphine (0.004 μg/kg; N = 10) to SC buprenorphine (4 μg/kg/day, N = 10) and to SC buprenorphine (8 μg/kg/day) preceded by placebo infusion (N = 10). However, Noda 1989 unfortunately did not report the results clearly and inferentially analysed between the treatment groups. Descriptively, it appears that pain intensity was lower, and comparable, in the groups receiving the higher dose of SC buprenorphine or buprenorphine preceded by IM buprenorphine compared to the group that received 4 μg/kg/day SC buprenorphine (see Table 4 for the reported adverse events).

Epidural buprenorphine versus epidural morphine

Pasqualucci 1987 compared single epidural doses of buprenorphine and morphine in a parallel‐group trial with six patients in each arm. This trial found no differences in pain scores after treatment with either buprenorphine or morphine (see Table 4 for the reported adverse events).

Intravenous buprenorphine versus intravenous morphine

In a parallel‐group study with treatment lasting 36 hours, Wang 2012 examined pain scores as assessed by a visual assessment scale for patients who were treated with IV buprenorphine and who had P‐gp+ (P‐glycoprotein; group B1; N = 30) and P‐gp‐ (group B2; N = 30) tumours and in patients who had received IV morphine and who had P‐gp+ (group M1; N = 30) and P‐gp‐ (group M2; N = 30) tumours. Wang 2012 reported that the VAS scores were similar between the four groups at baseline (means (SDs): B1 = 7.8 (1.6); B2 = 7.9 (1.2); M1 = 8.0 (1.5); M2 = 8.1 (1.7)), but then only included analyses between the groups that received the same drug. Wang 2012 reported that the VAS scores of groups B1 and B2 all differed significantly from baseline, but did not differ significantly from each other at four hours (means (SDs): B1 = 1.5 (0.9); B2 = 1.6 (0.8)), 12 hours (means (SDs): B1 = 1.6 (0.7); B2 = 1.5 (1)), 24 hours (means (SDs): B1 = 1.4 (0.7); B2 = 1.4 (0.9)) or 36 hours (means (SDs): B1 = 1.5 (1); B2 = 1.4 (1.1)), whereas for morphine the pattern of results was different. The VAS scores for both groups M1 and M2 were significantly lower than baseline at all times, but the pain scores were higher for group M1 compared to group M2 at four hours (means (SDs): M1 = 4.1 (2.4); M2 = 1.7 (1.1)), 12 hours (means (SDs): M1 = 4.4 (1.9); M2 = 1.8 (1.6)), 24 hours (means (SDs): M1 = 4.3 (1.6); M2 = 1.9 (1.4)) and 36 hours (means (SDs): M1 = 4.3 (2.3); M2 = 1.8 (1.4)). Groups M1 and M2 had received an identical dose of morphine (0.75 mg/kg). A second set of analyses comparing group M2 to group M1 after M1 had received a higher dose of morphine (1.1 mg/kg) showed that the increased dose of morphine brought down the pain scores of group M1 to levels that were comparable to those of group M2 at all the times (means (SDs) for group M1 new: 8 (1.7) at baseline; 1.8 (1.4) at four hours; 1.8 (1.9) at 12 hours; 1.7 (1.6) at 24 hours; 1.9 (1.8) at 36 hours), indicating that patients with P‐gp+ tumours are less sensitive to the analgesic effect of morphine than patients with P‐gp‐ tumours. Wang 2012 did not report on adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results