Abstract

Background

Engagement in multiple risk behaviours can have adverse consequences for health during childhood, during adolescence, and later in life, yet little is known about the impact of different types of interventions that target multiple risk behaviours in children and young people, or the differential impact of universal versus targeted approaches. Findings from systematic reviews have been mixed, and effects of these interventions have not been quantitatively estimated.

Objectives

To examine the effects of interventions implemented up to 18 years of age for the primary or secondary prevention of multiple risk behaviours among young people.

Search methods

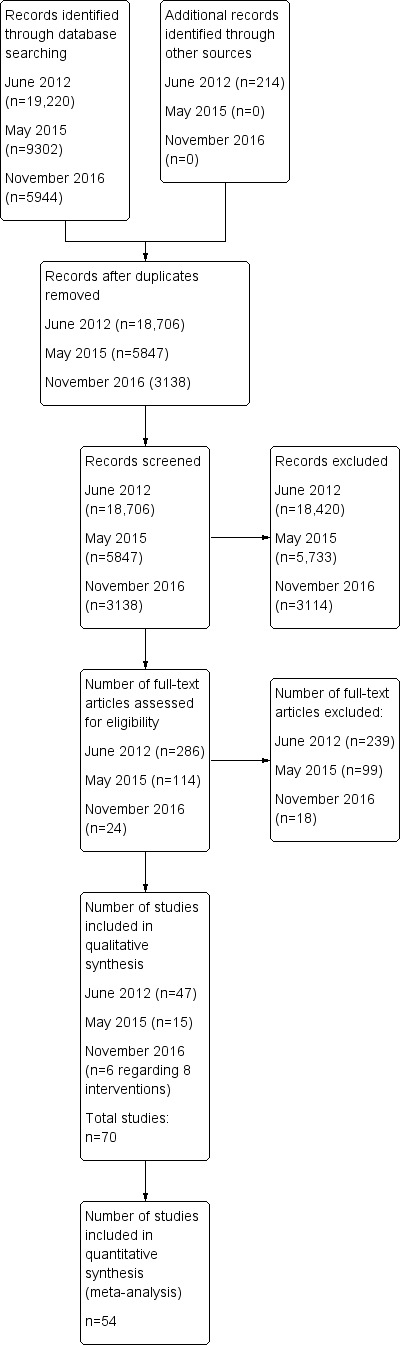

We searched 11 databases (Australian Education Index; British Education Index; Campbell Library; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library; Embase; Education Resource Information Center (ERIC); International Bibliography of the Social Sciences; MEDLINE; PsycINFO; and Sociological Abstracts) on three occasions (2012, 2015, and 14 November 2016)). We conducted handsearches of reference lists, contacted experts in the field, conducted citation searches, and searched websites of relevant organisations.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster RCTs, which aimed to address at least two risk behaviours. Participants were children and young people up to 18 years of age and/or parents, guardians, or carers, as long as the intervention aimed to address involvement in multiple risk behaviours among children and young people up to 18 years of age. However, studies could include outcome data on children > 18 years of age at the time of follow‐up. Specifically,we included studies with outcomes collected from those eight to 25 years of age. Further, we included only studies with a combined intervention and follow‐up period of six months or longer. We excluded interventions aimed at individuals with clinically diagnosed disorders along with clinical interventions. We categorised interventions according to whether they were conducted at the individual level; the family level; or the school level.

Data collection and analysis

We identified a total of 34,680 titles, screened 27,691 articles and assessed 424 full‐text articles for eligibility. Two or more review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion in the review, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias.

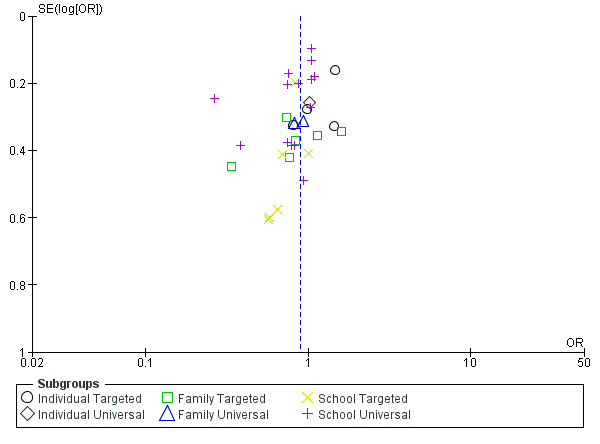

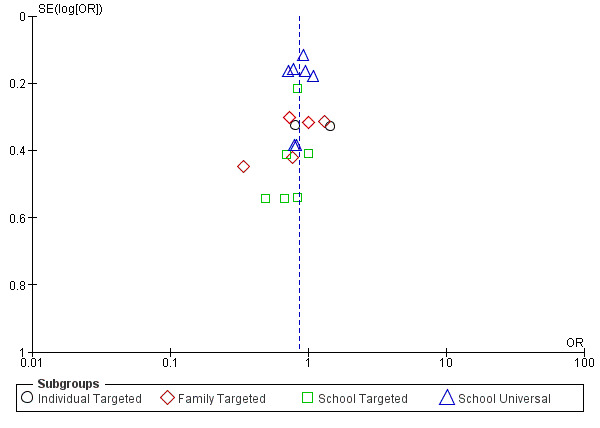

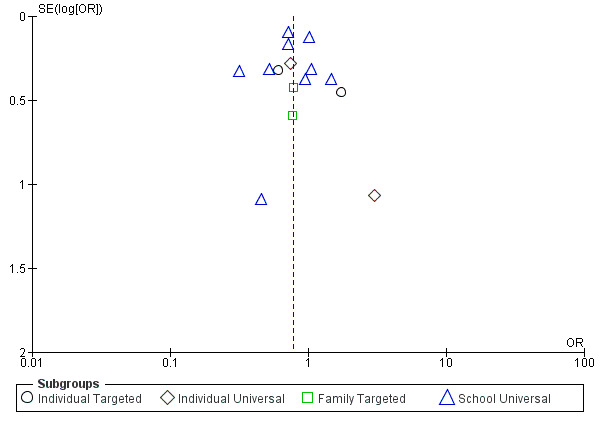

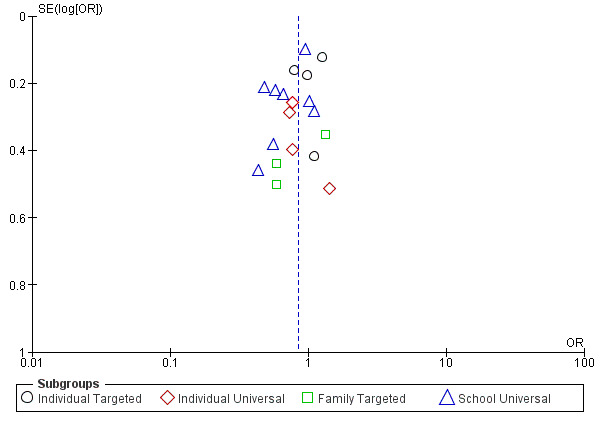

We pooled data in meta‐analyses using a random‐effects (DerSimonian and Laird) model in RevMan 5.3. For each outcome, we included subgroups related to study type (individual, family, or school level, and universal or targeted approach) and examined effectiveness at up to 12 months' follow‐up and over the longer term (> 12 months). We assessed the quality and certainty of evidence using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

We included in the review a total of 70 eligible studies, of which a substantial proportion were universal school‐based studies (n = 28; 40%). Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 55; 79%). On average, studies aimed to prevent four of the primary behaviours. Behaviours that were most frequently addressed included alcohol use (n = 55), drug use (n = 53), and/or antisocial behaviour (n = 53), followed by tobacco use (n = 42). No studies aimed to prevent self‐harm or gambling alongside other behaviours.

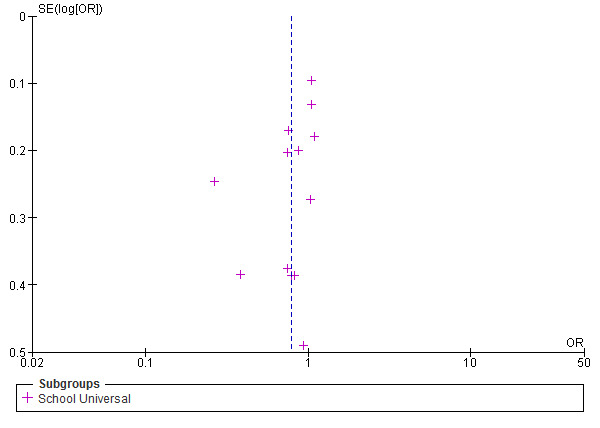

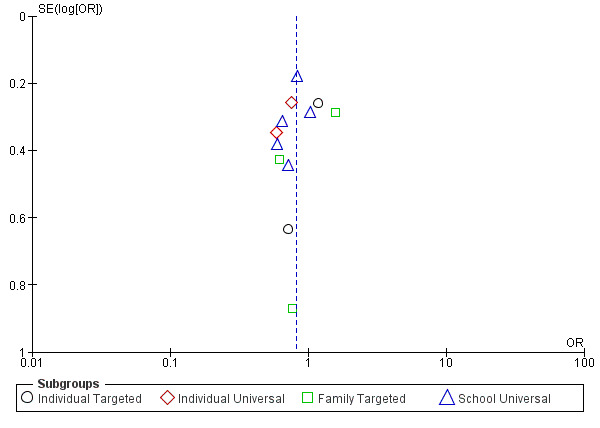

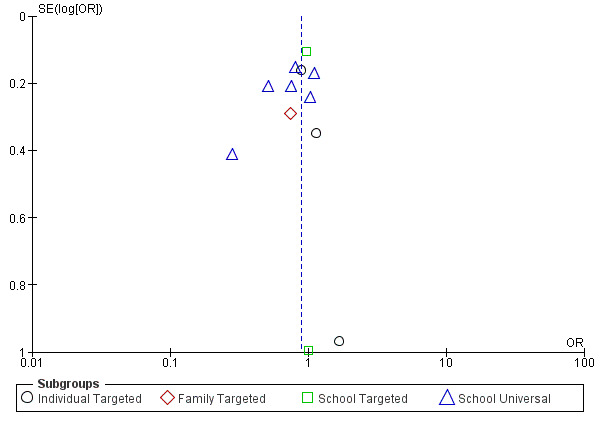

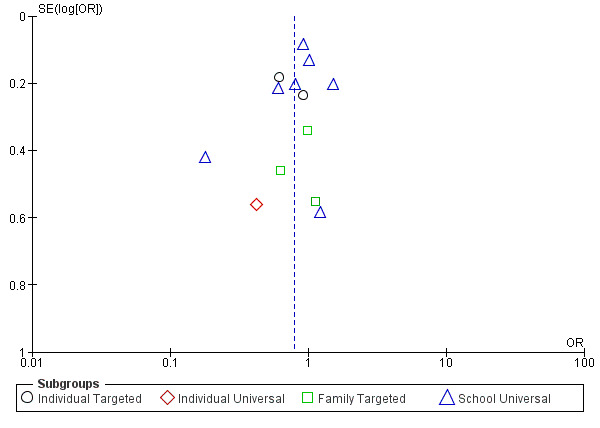

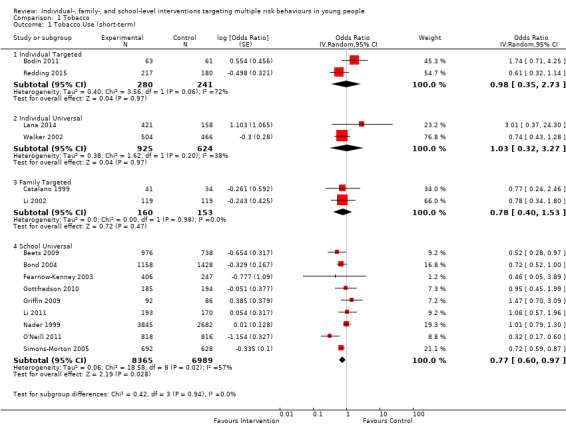

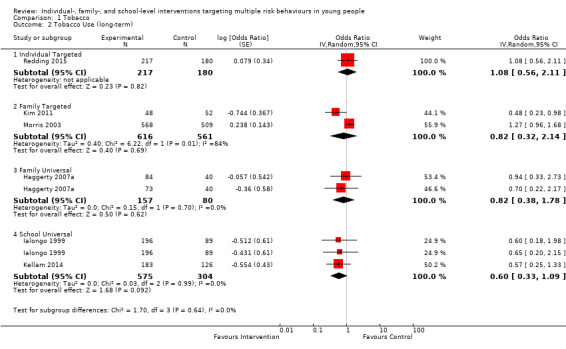

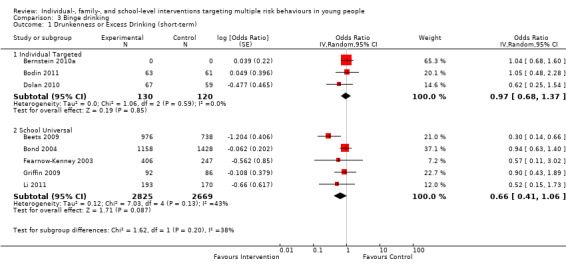

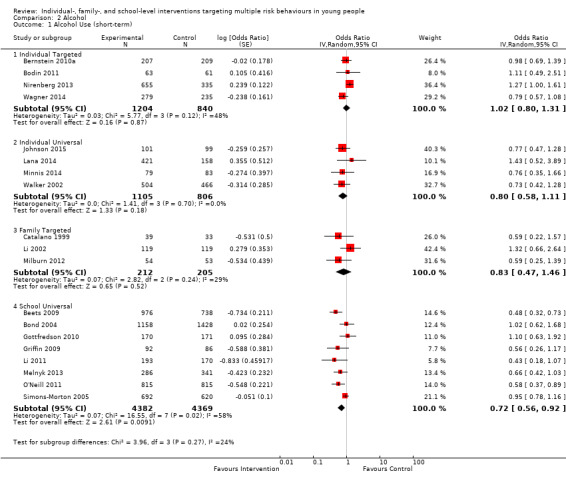

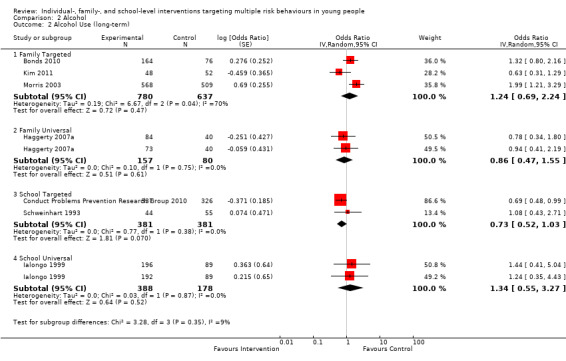

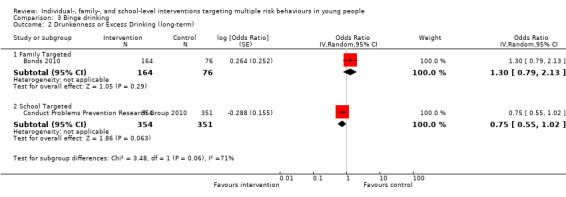

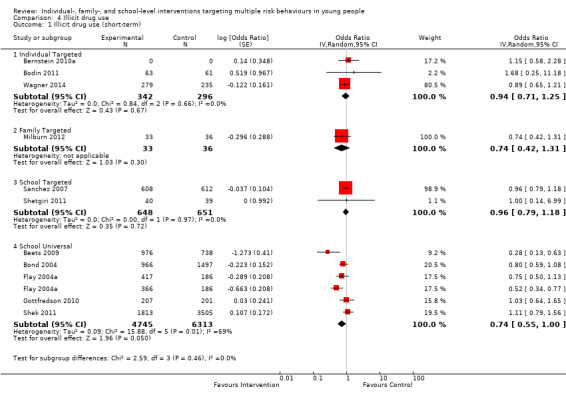

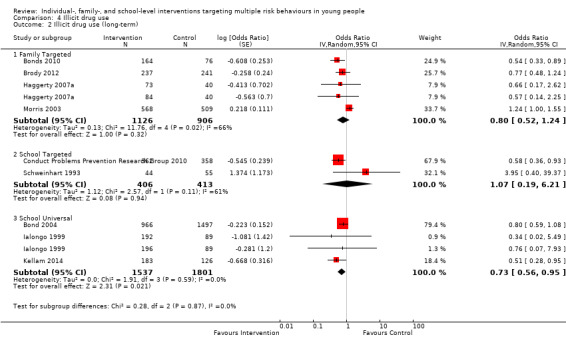

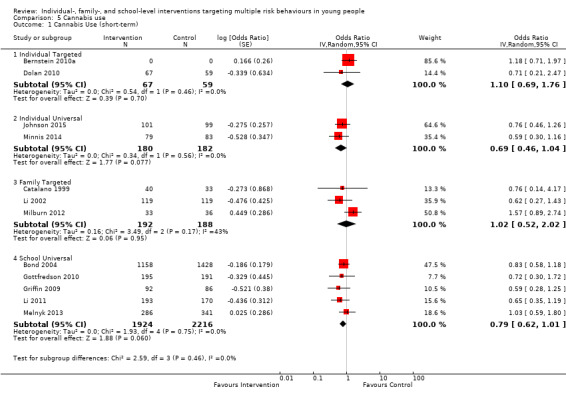

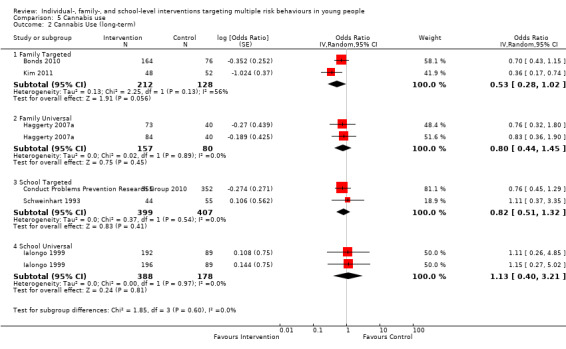

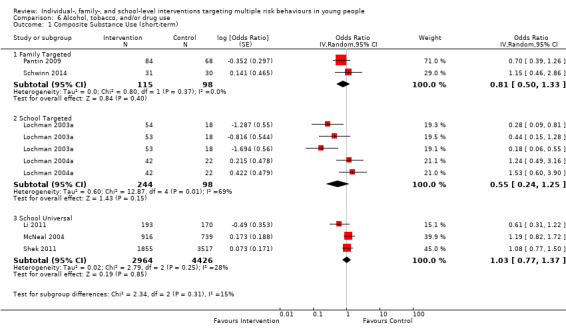

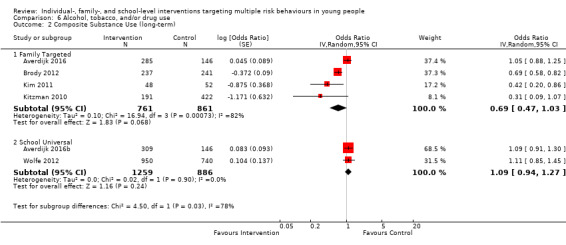

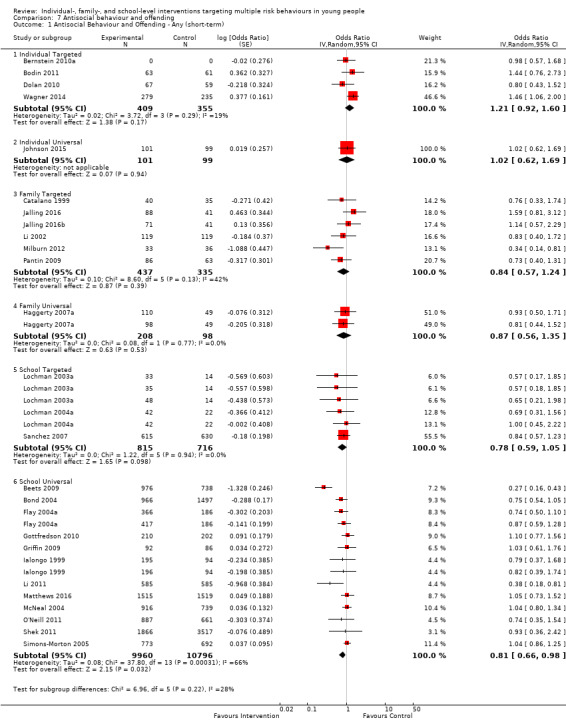

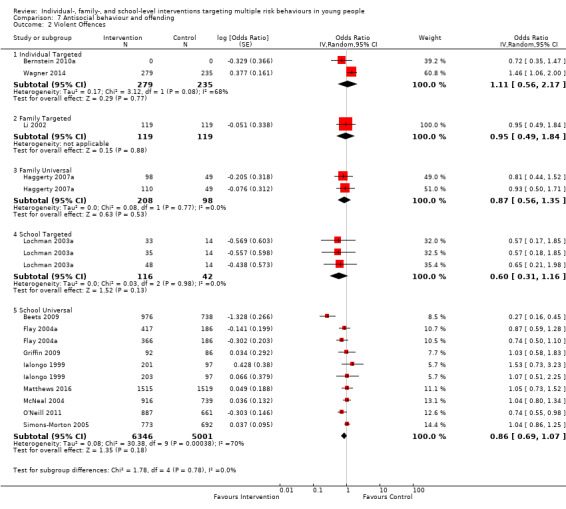

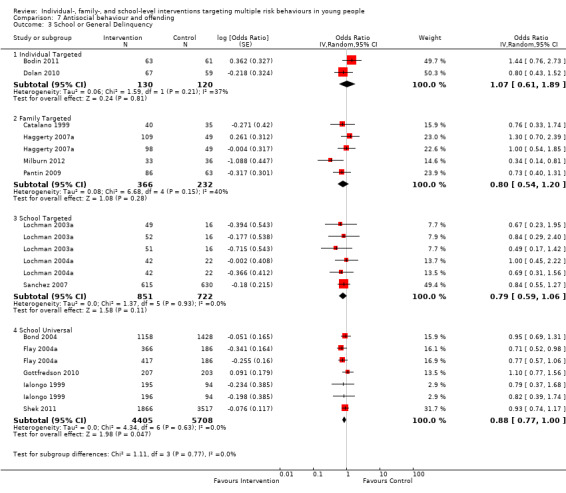

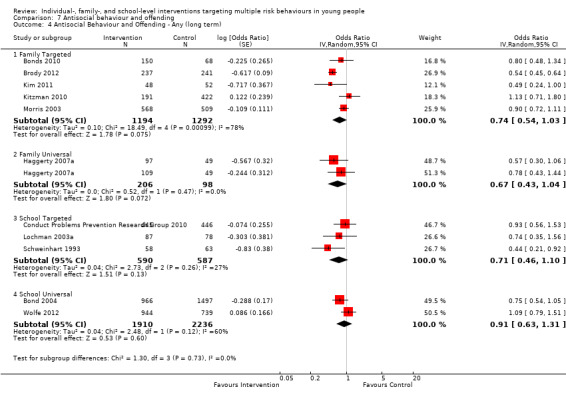

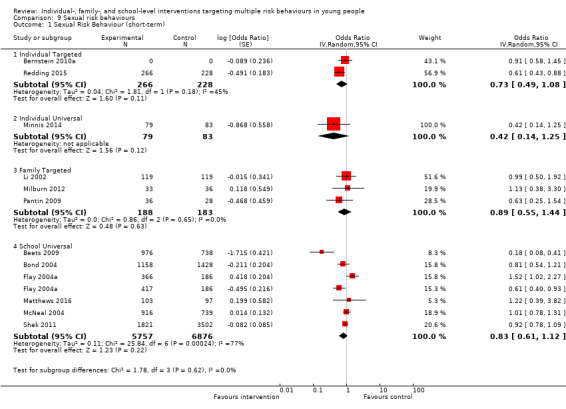

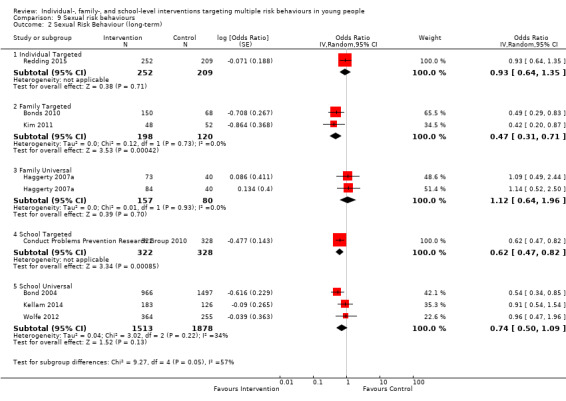

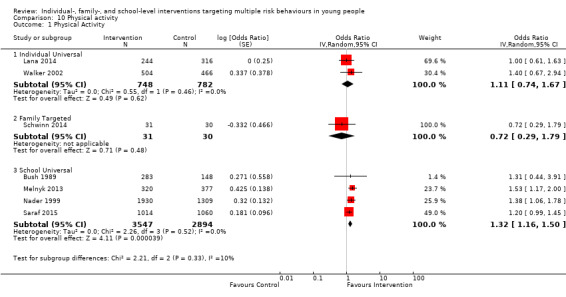

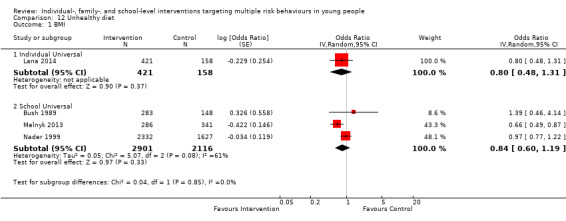

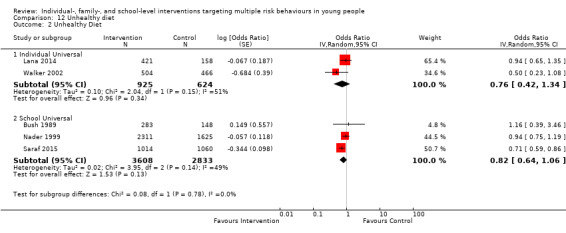

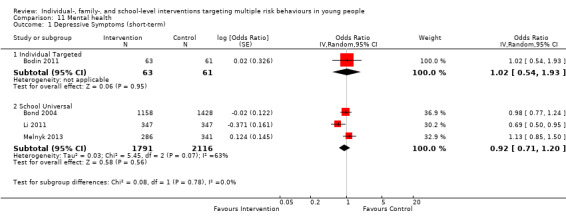

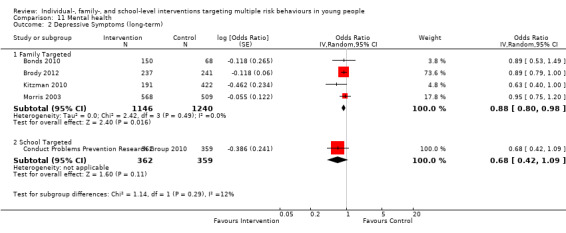

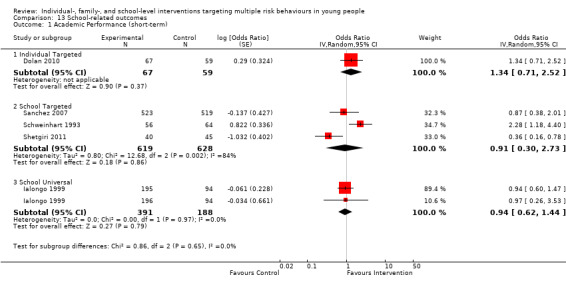

Evidence suggests that for multiple risk behaviours, universal school‐based interventions were beneficial in relation to tobacco use (odds ratio (OR) 0.77, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.60 to 0.97; n = 9 studies; 15,354 participants) and alcohol use (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.92; n = 8 studies; 8751 participants; both moderate‐quality evidence) compared to a comparator, and that such interventions may be effective in preventing illicit drug use (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.00; n = 5 studies; 11,058 participants; low‐quality evidence) and engagement in any antisocial behaviour (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.98; n = 13 studies; 20,756 participants; very low‐quality evidence) at up to 12 months' follow‐up, although there was evidence of moderate to substantial heterogeneity (I² = 49% to 69%). Moderate‐quality evidence also showed that multiple risk behaviour universal school‐based interventions improved the odds of physical activity (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.16 to 1.50; I² = 0%; n = 4 studies; 6441 participants). We considered observed effects to be of public health importance when applied at the population level. Evidence was less certain for the effects of such multiple risk behaviour interventions for cannabis use (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.01; P = 0.06; n = 5 studies; 4140 participants; I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), sexual risk behaviours (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.12; P = 0.22; n = 6 studies; 12,633 participants; I² = 77%; low‐quality evidence), and unhealthy diet (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.06; P = 0.13; n = 3 studies; 6441 participants; I² = 49%; moderate‐quality evidence). It is important to note that some evidence supported the positive effects of universal school‐level interventions on three or more risk behaviours.

For most outcomes of individual‐ and family‐level targeted and universal interventions, moderate‐ or low‐quality evidence suggests little or no effect, although caution is warranted in interpretation because few of these studies were available for comparison (n ≤ 4 studies for each outcome).

Seven studies reported adverse effects, which involved evidence suggestive of increased involvement in a risk behaviour among participants receiving the intervention compared to participants given control interventions.

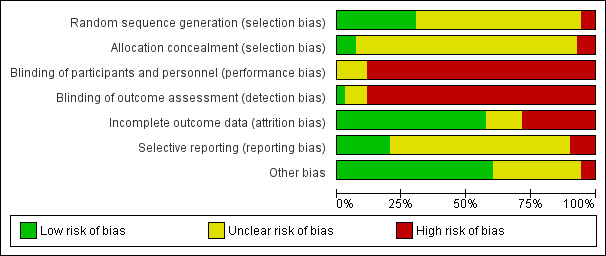

We judged the quality of evidence to be moderate or low for most outcomes, primarily owing to concerns around selection, performance, and detection bias and heterogeneity between studies.

Authors' conclusions

Available evidence is strongest for universal school‐based interventions that target multiple‐ risk behaviours, demonstrating that they may be effective in preventing engagement in tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and antisocial behaviour, and in improving physical activity among young people, but not in preventing other risk behaviours. Results of this review do not provide strong evidence of benefit for family‐ or individual‐level interventions across the risk behaviours studied. However, poor reporting and concerns around the quality of evidence highlight the need for high‐quality multiple‐ risk behaviour intervention studies to further strengthen the evidence base in this field.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Humans; Infant; Young Adult; Exercise; Risk‐Taking; Smoking Prevention; Alcohol Drinking; Alcohol Drinking/prevention & control; Automobile Driving; Family Therapy; Marijuana Abuse; Marijuana Abuse/prevention & control; Program Evaluation; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Schools; Sexual Behavior; Social Behavior Disorders; Social Behavior Disorders/prevention & control; Substance‐Related Disorders; Substance‐Related Disorders/prevention & control

Plain language summary

Interventions for preventing multiple risk behaviours in young people

Background

Health risk behaviours, such as smoking and drug use, can group together during the teenage years, and engagement in these multiple risk behaviours can lead to health problems such as injury and substance abuse during childhood and adolescence, as well as non‐communicable diseases later in life. Currently, we do not know which interventions are effective in preventing or decreasing these risky behaviours among children and young people.

Search methods and selection of studies

We carried out thorough searches of multiple scientific databases to identify studies that looked at ways of preventing or decreasing engagement in two or more risk behaviours, including tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, gambling, self‐harm, sexual risk behaviour, antisocial behaviour, vehicle‐risk behaviour, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition, among young people aged eight to 25 years. We divided these studies into groups (individual‐level, family‐level, and school‐level studies) according to whether researchers worked with individuals, families, or children and young people in schools, respectively. We specifically looked at "gold standard" studies ‐ randomised controlled trials that aimed to examine two or more behaviours of interest.

Main results

In total, 70 studies were eligible for inclusion in this review. Half included populations without any consideration for risk status, and half focused on higher‐risk groups. Most were conducted in the USA or in high‐income countries. On average, studies examined the effects of interventions on four behaviours, most commonly alcohol, tobacco use, drug use, and antisocial behaviour.

We found that for multiple risk behaviours, school‐based studies for all young people are more beneficial than a comparator for preventing tobacco use, alcohol use, and physical inactivity, and that they may also be beneficial in relation to illicit drug use and antisocial behaviour. Findings were weaker for cannabis use, sexual risk behaviour, and unhealthy diet. Evidence suggests that certain school‐based programmes could have a beneficial impact on more than one behaviour. In contrast, we did not find strong evidence of beneficial effects of interventions for families or individuals for the behaviours of interest, although caution must be applied in interpreting these findings because we identified fewer of these studies. Last, we found seven studies that reported increased levels of engagement in risk behaviours among those receiving the intervention compared to those given the control.

Overall, reviewers judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate or low for most behaviours examined using standardised criteria, with one behaviour found to have very low quality evidence. In part, this was due to concerns around how some studies were conducted, which could have introduced bias.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that school‐based interventions offered to all children that aim to address engagement in multiple risk behaviours may have a role to play in preventing tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and antisocial behaviour, as well as in improving physical activity, among young people, but not in the other behaviours examined. We did not find strong evidence of benefit of interventions for families or individuals. Concerns around reporting of studies and study quality highlight the need for additional robust, high‐quality studies to further strengthen the evidence base in this field.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Summary of findings table for the effectiveness of targeted individual‐level multiple risk behaviour interventions compared to usual practice for outcomes up to 12 months post intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and young people aged 0 to 18 years Settings: varied settings (home, kindergarten, primary school, secondary school, clinic, community) Intervention: multiple risk behaviour interventions Comparison: no intervention/usual practice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with usual practice |

Risk with intervention (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Tobacco use | 156 per 1000 | 191 per 1000 (122 to 288) |

OR 1.28 (0.75 to 2.19) | 521 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Alcohol use | 613 per 1000 | 618 per 1000 (559 to 675) |

OR 1.02 (0.80 to 1.31) | 1204 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Cannabis use | 110 per 1000 | 120 per 1000 (79 to 179) |

OR 1.10 (0.69 to 1.76) | 126 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Illicit drug use | 32 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (23 to 400) |

OR 0.94 (0.71 to 1.25) | 638 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Antisocial behaviour | 145 per 1000 | 170 per 1000 (135 to 213) |

OR 1.21 (0.92 to 1.60) | 764 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

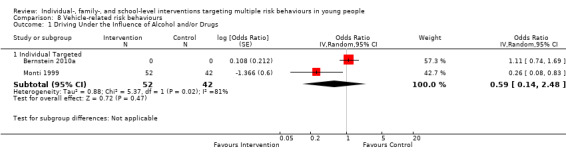

| Vehicle‐related risk behaviour | 81 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (12 to 179) |

OR 0.59 (0.14 to 2.48) |

94 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb | |

| Sexual risk behaviour | 610 per 1000 | 533 per 1000 (434 to 628) |

OR 0.73 (0.49 to 1.08) | 494 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Physical activity | 134 per 1000 | N/A | No studies in meta‐analysis | |||

|

aDowngraded owing to high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and/or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. bDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains, as well as imprecision related to width of the 95% confidence interval of the summary estimate and inconsistency between effect estimates (I² = 81%). Note that variation was evident in measures of risk with usual practice. Baseline risk measures were calculated at follow‐up. When no data were reported for any study in that meta‐analysis, baseline measures were used. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

2.

| Summary of findings table for the effectiveness of universal individual‐level multiple risk behaviour interventions compared to usual practice for outcomes up to 12 months post intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and young people aged 0 to 18 years Setting: varied settings (home, clinic, community) Intervention: multiple risk behaviour interventions Comparison: no intervention/usual practice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with usual practice |

Risk with intervention (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Tobacco use | 32 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (10 to 98) |

OR 1.03 (0.32 to 3.27) | 1549 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa | |

| Alcohol use | 41 per 1000 | 33 per 1000 (24 to 45) |

OR 0.80 (0.58 to 1.11) | 1911 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Cannabis use | 264 per 1000 | 198 per 1000 (142 to 272) |

OR 0.69 (0.46 to 1.04) | 362 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Illicit drug use | ‐‐ | N/A | No studies in meta‐analysis | |||

| Antisocial behaviour | 131 per 1000 | 133 per 1000 (85 to 203) |

OR 1.02 (0.62 to 1.69) |

200 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Sexual risk behaviour | 396 per 1000 | 216 per 1000 (84 to 450) |

OR 0.42 (0.14 to 1.25) | 162 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

| Physical activity | No data available to estimate risk | N/A | OR 1.11 (0.74 to 1.67) | 1,530 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | |

|

aDowngraded owing to high risk of bias in relation to blinding and incomplete outcome data. We also downgraded the certainty of evidence owing to inconsistency because between‐study variance was high and variability was evident in the effect estimates of each study. The 95% CIs of one of the studies were wide, but researchers reported very few events, so certainty of evidence was not downgraded on this basis. bDowngraded owing to high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and/or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. Note that variation was evident in measures of risk with usual practice. Baseline risk measures were calculated at follow‐up. When no data were reported for any study in that meta‐analysis, baseline measures were used. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

3.

| Summary of findings table for the effectiveness of targeted family‐level multiple risk behaviour interventions compared to usual practice for outcomes up to 12 months post intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and young people aged 0 to 18 years Setting: varied settings (home, community) Intervention: multiple risk behaviour interventions Comparison: no intervention/usual practice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with usual practice |

Risk with intervention (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Tobacco use | 176 per 1000 | 143 per 1000 (79 to 246) |

OR 0.78 (0.40 to 1.53) | 313 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Alcohol use | 269 per 1000 | 234 per 1000 (147 to 349) |

OR 0.83 (0.47 to 1.46) | 417 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Cannabis use | 180 per 1000 | 183 per 1000 (102 to 307) |

OR 1.02 (0.52 to 2.02) | 380 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | |

| Illicit drug use | 265 per 1000 | 211 per 1000 (132 to 321) |

OR 0.74 (0.42 to 1.31) | 69 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Antisocial behaviour | 291 per 1000 | 256 per 1000 (190 to 337) |

OR 0.84 (0.57 to 1.24) | 772 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Sexual risk behaviour | 750 per 1000 | 728 per 1000 (623 to 812) |

OR 0.89 (0.55 to 1.44) | 371 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Physical activity | No data available to estimate risk | N/A | OR 0.72 (0.29 to 1.79) | 61 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

|

aDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. bDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. The quality of the evidence was also downgraded on the basis of inconsistency because between‐study variance was high, and although I² was moderate, inconsistency was evident in effect estimates of individual studies, two of which had small sample sizes. Note that variation was evident in measures of risk with usual practice. Baseline risk measures were calculated at follow‐up. When no data were reported for any study in that meta‐analysis, baseline measures were used. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

4.

| Summary of findings table for the effectiveness of targeted school‐level multiple risk behaviour interventions compared to usual practice for outcomes up to 12 months post intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and young people aged 0 to 18 years Setting: school Intervention: multiple risk behaviour interventions Comparison: no intervention/usual practice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with usual practice |

Risk with intervention (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Tobacco use | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No data in meta‐analysis | |||

| Alcohol use | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No data in meta‐analysis | |||

| Cannabis use | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No data in meta‐analysis | |||

| Illicit drug use | 50 per 1000 | 38 per 1000 (27 to 53) | OR 0.75 (0.53 to 1.06) | 2454 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Antisocial behaviour | No data available to estimate risk | N/A | OR 0.78 (0.59 to 1.05) | 1,531 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Sexual risk behaviour | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No data in meta‐analysis | |||

| Physical activity | ‐‐ | ‐‐ | No data in meta‐analysis | |||

|

aDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. Note that variation was evident in measures of risk with usual practice. Baseline risk measures were calculated at follow‐up. When no data were reported for any study in that meta‐analysis, baseline measures were used. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

5.

| Summary of findings table for the effectiveness of universal school‐level multiple risk behaviour interventions compared to usual practice for outcomes up to 12 months post intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and young people aged 0 to 18 years Setting: school Intervention: multiple risk behaviour interventions Comparison: no intervention/usual practice | ||||||

| Outcomes | Risk with usual practice |

Risk with intervention (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Tobacco use | 54 per 1000 | 42 per 1000 (33 to 52) |

OR 0.77 (0.60 to 0.97) | 15,354 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Alcohol use | 163 per 1000 | 123 per 1000 (98 to 152) |

OR 0.72 (0.56 to 0.92) | 8751 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Cannabis use | 110 per 1000 | 89 per 1000 (71 to 111) |

OR 0.79 (0.62 to 1.01) | 4140 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

| Illicit drug use | 41 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (21 to 44) |

OR 0.73 (0.50 to 1.07) | 10,266 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | |

| Antisocial behaviour | 172 per 1000 | 141 per 1000 (117 to 168) |

OR 0.79 (0.64 to 0.97) | 17,722 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowc | |

| Sexual risk behaviour | 131 per 1000 | 112 per 1000 (87 to 146) |

OR 0.84 (0.63 to 1.13) | 12,633 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | |

| Physical activity | 276 per 1000 | 335 per 1000 (307 to 364) |

OR 1.32 (1.16 to 1.50) | 6,441 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | |

|

aDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. bDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. Downgraded an additional level on the basis of inconsistency because substantial heterogeneity was evident (I² = 69%, Chi² = 15.88, P = 0.007), between‐study variance was moderate, and inconsistency between effect estimates of individual studies was apparent, with absence of overlap between 95% CIs of certain studies in the subgroup. cDowngraded owing to high risk of bias on the basis of blinding and/or high or unclear risk of bias across additional domains. The quality of evidence was also downgraded on the basis of inconsistency because heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 68%, Chi² = 36.95, P = 0.0002), between‐study variance was moderate, and lack of overlap was apparent between 95% CIs for certain studies with large sample sizes. Last, evidence was downgraded on the basis of possible publication or small‐study bias. dDowngraded owing to high risk of bias in relation to blinding and/or other domains. Certainty of the evidence was also downgraded owing to substantial heterogeneity (I² = 84%, Chi² = 25.07, P < 0.0001) and high between‐study variance, with lack of overlap between the 95% CIs of certain studies in the subgroup. Although there may be plausible explanations for such heterogeneity, these reasons could not be further investigated in this review. Note that variation was evident in measures of risk with usual practice. Baseline risk measures were calculated at follow‐up. When no data were reported for any study in that meta‐analysis, baseline measures were used. CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomised controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

Background

Description of the condition

Adolescence and young adulthood represent critical periods in the life course in relation to current and future health and wellbeing (Lancet 2012; Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health & Wellbeing; Patton 2012; World Health Organization 2014). Many of the health risk behaviours that give rise to chronic non‐communicable diseases (NCDs) later in life, such as tobacco use, alcohol use, consumption of calorific foods, and physical inactivity, are initiated during adolescence (Resnick 2012; Sawyer 2012), and they can continue into late adolescence and young adulthood (Mahalik 2013; McCambridge 2011;Ortega 2013;Resnick 2012; Sawyer 2012; Wanner 2006). Engagement in such behaviours can increase risks of low educational attainment, antisocial behaviour, sexually transmitted infections, injury, and substance use dependence during adolescence and young adulthood, and can influence morbidity later in life (Chen 1995; Djousse 2009;Hall 2016; Mason 2010;McCambridge 2011;Ortega 2013;Silins 2015), thus affecting health throughout the life course (World Health Organization 2014). Globally, for instance, alcohol use (7% of disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs)), unsafe sex (4%), and illicit drug use (2%) are among the main risk factors for the incidence of DALYs among young people aged 10 to 24 years (Gore 2011; Mokdad 2013).

Estimates of the prevalence of concurrent tobacco smoking, drinking of alcohol, and recent illicit drug or cannabis use for adolescents in the UK, the USA, and Canada range from 6% to 13% (Connell 2009; de Winter 2016; Fuller 2015; Leatherdale 2010; McVie 2005; NHS 2008), and a recent UK report estimated that over 20% of young people aged 16 engage in two or more substance use and delinquent behaviours (Hale and Viner 2016). Critically, risk behaviours such as smoking, antisocial behaviour, alcohol consumption, and sexual risk behaviour have been shown to cluster in adolescence (Basen‐Engquist 1996; Burke 1997; de Looze 2014; Junger 2001; Mistry 2009; Pahl 2010; van Nieuwenhuijzen 2009), and engagement in one risk behaviour increases the likelihood of engagement in others. For example, both smoking and low vegetable intake at age 13.5 increased the odds of engagement in multiple health risk behaviours at age 16 by over twofold (de Winter 2016), and odds ratios for associations between use of individual substances and sexual risk behaviours range between 1.4 and 4.7 (Jackson 2012; Meader 2016).

Engagement in multiple risk behaviours therefore can be viewed as supporting the syndemic concept, whereby synergistic involvement in risk behaviours may worsen the outcomes of engagement in risk behaviours and associated comorbidities later in life (Mendenhall 2017). Given that adolescents comprise a quarter of the world’s population worldwide, and often more than a fifth of a country's population, engagement in multiple health risk behaviours and the impact of such engagement represent a significant public health concern. In recognition of the importance of investment in adolescent health as the foundation of health and wellbeing across the life course, recent literature has highlighted the need for greater focus on adolescent health worldwide and the global application of preventive interventions and policies (Lancet 2012; Patton 2014; Resnick 2012; World Health Organization 2014). Evidence has also highlighted the health, economic, and social returns that could be realised from greater global investment in adolescent health (Catalano 2012; Lancet Commission on Adolescent Health & Wellbeing; Sheehan 2017).

Description of the intervention

This review examines evidence for interventions that are universal in their approach (i.e. that address whole populations with the aim of preventing the onset or advancement of risk behaviours, as well as those that target particular groups who may be at higher risk (e.g. those identified through screening or other assessment of risk factors such as following referral from the criminal justice system)). Interventions provided at individual, family, and school levels, as well as those that encompass more than one of these domains, are considered. Thus, the interventions considered in this review are wide‐ranging in design and may be implemented in a range of settings by providers such as nurses, teachers, or peers, with the goal of impacting behaviours of young people up to 18 years of age.

Interventions focused at the individual level include mentoring, coaching, Internet‐level education, conditional cash transfers, development of prosocial networks, and motivational interviewing. Family‐focused interventions may involve group sessions or home visits and support, and they aim to improve child‐parent interactions, communication, the family environment (e.g. through conflict resolution and problem‐solving), parenting skills, parental support, resilience and wellbeing, and knowledge and awareness. Such programmes may incorporate components for children or adolescents, including adolescent skills‐building and decision‐making curricula, goal‐setting, or practice and reinforcement of skills and behaviours. Targeted family‐based interventions may be targeted to adolescents at higher risk, such as those who are homeless or are experiencing parental substance abuse.

School programmes aim to target normative beliefs, bonding to school, behavioural goals, and commitments to not engage in risk behaviours and knowledge. They do so by utilising a range of diverse strategies, including formal classroom curricula, peer delivery, behaviour management practices, role‐play, goal‐setting, and whole‐school approaches that aim to change the school climate or ethos. Such domains can be implemented either alone or alongside additional parent or community components, such as parent leaflets, parent‐child homework exercises, extracurricular activities, and community engagement activities. Targeted interventions delivered at the school level may focus on particular higher‐risk groups, such as those in lower socioeconomic groups, those demonstrating aggressive behaviour, and those identified as being at high risk of school dropout.

How the intervention might work

The goals of multiple risk behaviour interventions are to prevent engagement in two or more behaviours, to reduce the frequency of engagement in these behaviours, and to reduce the prevalence and impact of short‐ and long‐term negative consequences associated with engagement in those behaviours.

Interventions at individual, family, and school levels may have distinct hypotheses regarding mechanisms of effect, as discussed below. For instance, individual‐level interventions may focus more exclusively on improving motivation to act, identifying goals, obtaining normative feedback, coaching, and modelling positive behaviour, with some models such as mentoring based on the underlying hypothesis that providing positive role models, support, and prosocial aspirations can change behaviour and reduce risk.

Family‐based interventions may focus on provision of skills, knowledge, and support; frequency and quality of parent‐child communications; and reinforcement of shared values and behaviours. Grounding of several interventions in social development theory, with a focus on family as one 'unit of socialisation', suggests that sufficient engagement and involvement with family and subsequent positive reinforcement can enhance family attachment, thus helping to underpin strong bonds to school, increased likelihood of involvement with prosocial peers, and reduced likelihood of risk behaviour (Hawkins and Weis 1985). Building on cognitive models, interventions may also work by influencing perceptions of risk, behavioural intentions, and self‐regulation via recognition that risk behaviours may result from a reaction to circumstances conducive to risk‐taking, depending on the intention and willingness of the individual to engage in the behaviour and perceptions of risk associated with the behaviour (Gibbons 2007). In addition, interventions may act by improving parental monitoring and providing support. In this way, parents serve as a source of socialisation regarding norms and behavioural expectations,but also provide feedback that can influence attitudes and behaviour (Brody 2005; Murry 2009;Murry 2014).

School‐based programmes may aim to enhance knowledge, social and emotional skills, resilience, and social competence, thereby improving self‐esteem and self‐control and reducing the impact of negative peer, family, and/or social influences ‐ all of which can increase the risk of engagement in risk behaviours (Biglan 2004; Chen 1995; Hawkins 2005; Jackson 2010; Mason 2010). Alternatively, programmes may seek to reinforce engagement in healthy behaviours by providing positive role‐modelling, addressing perceptions of behaviours and their consequences, and considering social influences and norms.

Theories that seek to explain why risk behaviours cluster during adolescence are relevant to consideration of how interventions might work. First, Moffitt's theory of adolescence‐limited antisocial behaviour highlights two distinct categories of individuals with differing natural histories and etiologies of antisocial behaviour: the 'adolescence‐limited' group, whose behaviour is limited to adolescence and whose behaviour is normative but in whom risk behaviours may be temporarily sustained via mimicry of antisocial behaviour observed in antisocial peers; and the second, smaller group ‐ the 'life course persistent' group, whose members progress to become lifelong offenders (Moffitt 1993). Second, Jessor's problem behaviour theory (PBT) proposes that clustering of behaviours results from a complex web of interrelated predisposing and protective factors involving interaction between individual and environment (Jessor 1991;Jessor 1992). To date, studies have highlighted shared predisposing or protective factors at individual, intermediate, and structural levels, such as positive mental health, family attachment, peer relationships, socioeconomic status, social environment, and connection with school and religion (Beyers 2004; Catalano 2012; de Looze 2014; Hale and Viner 2016; Jackson 2010; Kipping 2014;Sawyer 2012; Viner 2006).

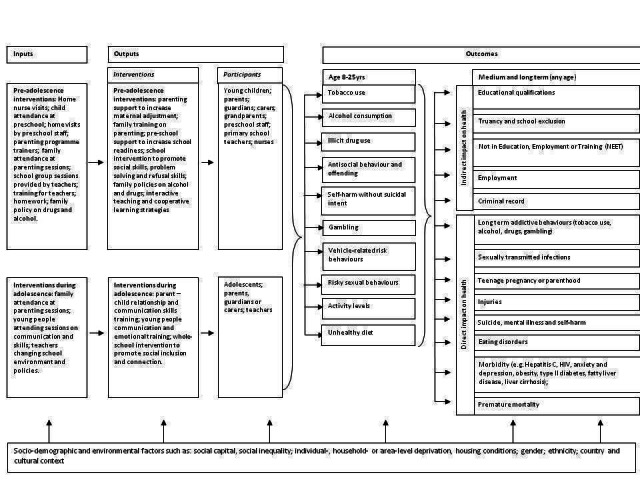

Determinants of engagement in risk behaviours during adolescence are therefore complex, and it is noteworthy that their antecedents may originate before birth or during the early years of life, and may accumulate early in the life course (Biglan 2004; Catalano 2012; Jessor 1991; Kuh 2003). Early adverse experiences and stressors such as violence, disease, and poor nutrition in infancy and early childhood can affect growth, health, and developmental milestones such as school readiness, literacy, and healthy peer relationships. Interventions that influence early determinants of risk are central to a life course approach and may have a greater impact on an individual's propensity to engage in risk behaviours during adolescence than those that focus on reducing behaviours or mitigating harms once the risk behaviours have become established, as outlined in the logic model (Figure 1). Interventions that provide support to mothers during pregnancy, for instance, may enhance maternal skills, promote healthy behaviours, and enhance emotional well‐being, which may increase mother‐child interaction and reduce environmental stressors (Biglan 2004; Eckenrode 2010). Interventions provided during the preschool years, which comprise training in parenting or increased preschool attendance, may prevent multiple risk behaviours later in life by reducing stressors within the family environment and by enhancing maternal and child skills (Biglan 2004; Hawkins 2005, Reid 1999; Shepard and Dickstein 2009; Tremblay 1995; Webster‐Stratton and Taylor 2001). If unchecked, however, risk can continue to accumulate from early life to adolescence, increasing the likelihood of peer rejection, lack of engagement with school, low academic achievement, and a trajectory towards engagement with risk behaviours (Catalano 2012; Sawyer 2012). Thus, interventions implemented during adolescence can build on investment in the early years and target those at higher risk, or can be implemented with the aim of protecting young people from normative increases in engagement in risk behaviours (Catalano 2012; World Health Organization 2014).

1.

Logic Model: interventions to prevent multiple risk behaviours in individuals aged 8 to 25 years.

Why it is important to do this review

Whilst many health interventions aim to prevent single behaviours, and several Cochrane reviews have focused on specific types of interventions to address single behaviours (Carney 2016; Faggiano 2014;Fellmeth 2011; Foxcroft 2011;Livingstone 2010;Mytton 2006), less is known about the effectiveness of interventions that aim to simultaneously prevent a wide range of multiple risk behaviours (Biglan 2004; Jackson 2010). Given that risk behaviours cluster, and that determinants of engagement in these behaviours may overlap, it is possible that multiple‐behaviour interventions may be both efficient and effective. A recent scoping review examined characteristics of interventions to prevent multiple risk behaviours but focused on adult populations (King 2015). Of the two systematic literature reviews that have focused on prevention of multiple risk behaviour in young people, one focused on the impact of interventions to target substance use and sexual risk behaviour (Jackson 2010; Jackson 2011), and the other focused on interventions that target substance use, antisocial behaviour, and sexual risk behaviour (Hale 2014), while including only interventions that reported statistically significant effects. To date, therefore, no single Cochrane review has systematically examined evidence relating to the impact of interventions that address multiple behaviours. Critically, there remains no quantitative estimate of effect to guide public health decision‐making.

This review considers the effectiveness of individual‐, family‐, and/or school‐level interventions that aim to address tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, gambling, self‐harm, vehicle‐risk behaviours, antisocial behaviour, sexual risk behaviour, physical inactivity, and poor nutrition. This review is therefore broader with respect to the number of behaviours, settings, and populations of focus.

Given limited opportunities and resources to prevent risk behaviours, it is important to explore whether targeting multiple behaviours may be more efficient than targeting single behaviours. Greater understanding of the effects of multiple risk behaviour interventions in the context of tightening budgets has substantial potential to influence decisions around commissioning and/or de‐commissioning of risk prevention interventions for children and young people.

Objectives

Primary research objective

To examine the effects of interventions implemented up to 18 years of age for the primary or secondary prevention of multiple risk behaviours among individuals aged eight to 25 years (see MacArthur 2012 for the protocol of this review)

Secondary research objectives

To explore whether effects of the intervention differ within and between population subgroups

To examine whether effects of the intervention differ by risk behaviours and by outcomes

To investigate the influence of the setting of the intervention on design, delivery, and outcomes of the interventions

To investigate the relationship between numbers and/or types of component(s) of an intervention, intervention duration, and intervention effects

To evaluate whether the impacts of interventions differ according to whether behaviours are addressed simultaneously or sequentially and/or whether behaviours are addressed in a particular order

To explore the association between clustering of particular behaviours and effects of the interventions

To assess the cost‐effectiveness of the interventions

To consider the implications of the findings of this review for further research, policy, and practice

In this review, we aim to examine the effects of interventions on each of the studied behaviours, in turn, and through further analyses to ascertain the effects of these interventions on multiple risk behaviours.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster RCTs, that aimed to address at least two risk behaviours of interest. We included only RCTs because studies using this design provide the most reliable type of evidence for assessing effects of interventions in that they minimise the risk that findings may have been influenced by confounding (Akobeng 2005). We included RCTs that primarily assessed effectiveness of interventions but also reported findings of a full or partial economic evaluation, and those that reported resource use or costs associated with an RCT intervention. We included only studies with a combined intervention and follow‐up period of six months or longer, to enable identification of the impact of interventions over the shorter term without exclusion of studies that were not able to monitor outcomes over a longer period.

Types of participants

Participants were children and young people aged up to 18 years. Studies were also included in which participants receiving the intervention were parents, guardians, carers, peers, and/or members of a school, as long as the intervention aimed to impact involvement in multiple risk behaviours among children and young people aged up to 18 years. We included interventions targeting participants in subgroups of the population, but we excluded interventions aimed at individuals with clinically diagnosed disorders.

Types of interventions

Interventions included in this review comprised interventions that aimed to address at least two risk behaviours from among regular tobacco use; alcohol consumption; recent cannabis or other regular illicit drug use; risky sexual behaviours; antisocial behaviour and offending; vehicle‐related risk behaviours; self‐harm (without suicidal intent); gambling; unhealthy diet; high levels of sedentary behaviour; and low levels of physical activity. We excluded interventions that addressed just two risk behaviours including unhealthy diet, low levels of physical activity, and/or high levels of sedentary behaviour, to avoid overlap with a previous Cochrane systematic review (Waters 2012). In addition, we excluded interventions that address two or more risk behaviours from among tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and/or drug use; a separate review will examine these interventions (Hickman 2014). In this way, we excluded interventions that target only healthy eating and physical activity, or only tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and drug use, for example, but included interventions that target healthy eating, physical activity, and risky sexual behaviour; or alcohol use, tobacco use, and antisocial behaviour. Last, we included RCTs delivered at the individual, family, or school level; another Cochrane review will include studies conducted at the community or population level, such as media campaigns or policy, regulatory, or legislative interventions, owing to their distinct study design (Campbell 2012). We classified studies as 'individual' if they recruited participants from the general community setting (but not from the school or family), and if they delivered the bulk of the intervention component(s) in one of the following settings: criminal justice (i.e. prisons or youth offending institutions), general practice surgeries, accident and emergency departments, or community‐based settings (for mentoring‐only interventions delivered to individuals within a community setting). We classified studies as 'school‐based' if researchers recruited participants from schools and delivered most of the intervention components in a school setting, and as 'family‐level' if investigators recruited parent(s) or child(ren) from the community and delivered most of the intervention components to the family within the home or in a neutral centre‐based environment.

Researchers compared those receiving the intervention versus those receiving usual practice, no intervention, or placebo or attention control. Interventions could be conducted at the individual, family, or school level and could include psychological, educational, parenting, or environmental approaches. As described above, interventions could be provided universally, without regard for the young people's level of risk, or they could be targeted to particular young people or families. Thus, for example, studies could be conducted at an individual level without regard for risk status (universal individual‐level interventions), or they could target particular groups of students in schools (targeted school‐level interventions). We classified studies as 'universal' in their approach if all school children within a school (or those in a particular year group), all individuals within a community/organisation, or all families within a community were eligible to participate in those studies. This contrasts with interventions classified as 'targeted', usually defined by participant characteristics (e.g. ethnicity, gender, pre‐existing behavioural problems/issues). However, for studies implementing an intervention for individuals/families in an area with a high crime rate, a high percentage of social deprivation, or a high percentage of black minority ethnic individuals, or for schools specially selected to include a certain percentage of students with a specific student ethnic population, we viewed interventions as 'universal', as not all participants would be subject to these characteristics. Interventions could start before the onset of behaviours (primary prevention), or they could target those currently engaged in risk behaviours (secondary prevention). We excluded stand‐alone clinical interventions (e.g. cognitive‐behavioural therapy).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was the primary or secondary prevention of two or more risk behaviours in individuals aged eight to 25 years. This age range was chosen owing to the likelihood of engagement in risk behaviours over this age range and the impact(s) and public health importance of engaging in risk behaviours during this period of the life course. Relatively few studies have examined the epidemiology of multiple risk behaviours; therefore the review includes behaviours that have an adverse impact on health, whether or not the behaviour involves an active desire for 'risk‐taking' or immediate gratification. We excluded from this review risk behaviours such as lack of ultraviolet (UV) protection, disordered eating, disordered sleep, and the choking game based on available evidence regarding prevalence, adverse impact on health, or relatedness to included behaviours; or we did so to avoid overlap with, or incorporation of, clinically diagnosed disorders. Consultation with the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health ImpRovement (DECIPHer) Public Involvement Advisory Group ALPHA (Advice Leading to Public Health Advancement) and the advisory group for the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) has supported inclusion of the range of behaviours outlined below.

We categorised risk behaviours as follows.

Tobacco use: regular tobacco use.

Alcohol consumption: binge drinking (alcohol); heavy/hazardous drinking; regular or problem drinking.

Drug use: recent cannabis use; recent illicit drug use (other than cannabis); regular illicit drug use.

Antisocial behaviour and offending: murder; aggravated assault; sexual assault; violence (including domestic or sexual violence); assault with or without injury; gang fights; hitting a teacher, parent, or student; racist abuse; criminal damage; robbery; burglary/breaking and entering; vehicle‐related theft; prostitution; selling drugs; joy‐riding; carrying a weapon; engaging in petty theft or other theft; pan‐handling (begging); buying stolen goods; being noisy and rude; exhibiting disorderly conduct; being a nuisance to neighbours; graffiti (Biglan 2004; Hales 2010).

Self‐harm: self‐harm without suicidal intent.

Gambling: gambling; regular/uncontrolled gambling.

Vehicle‐related risk behaviours: cycling without a helmet; not using a car seatbelt; driving under the influence of alcohol, cannabis, or illicit substances.

Risky sexual behaviours: unprotected sexual intercourse; early sexual debut experience.

Activity levels: low levels of physical activity; high levels of sedentary behaviour.

Unhealthy diet: low levels of fruit and vegetable consumption; low‐fibre diet; high‐fat diet; high‐sugar diet.

We excluded behaviours reported as clinical disorders (e.g. substance use disorder representing a clinical diagnosis). We included studies that addressed behaviours via upstream precursors for which a hypothesis or a clear rationale for the pathway of effect from the precursor to the subsequent behaviour was reported. This was particularly relevant for studies targeting young children (e.g. in primary school settings).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include potential medium‐ and longer‐term outcomes that interventions are aiming to effect.

Education and employment: educational qualifications; truancy and school exclusion; employment; not being in education, employment, or training (NEET).

Crime: criminal record/offending; re‐offending.

Long‐term addictive behaviours: smoking, alcohol, drugs, gambling.

Health outcomes: teenage pregnancy or parenthood; sexually transmitted infections; injuries; morbidity (e.g. hepatitis C, HIV, anxiety and depression, obesity, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, liver cirrhosis); suicide/self‐harm; premature mortality.

Harm associated with the process or outcomes of the intervention: for instance, if the extent of engagement in risk behaviours or adverse health outcomes increases as a result of the intervention.

Cost‐effectiveness of the intervention: measures of resource use; costs; or cost‐effectiveness of the intervention (e.g. incremental cost‐effectiveness ratios (ICERs), incremental cost per quality‐adjusted life‐year (QALY); cost‐benefit ratio).

Given the longer‐term adverse consequences of engagement in multiple risk behaviours and the importance of sustained outcomes, we used a primary endpoint for outcome data at the longest follow‐up point post intervention, up to a period of 12 months. We grouped outcome data from interventions with longer duration of follow‐up into a longer‐term category, which included any outcome data collected after 12 months post intervention. When data from more than one time point were reported, we took data from the furthest time point from the end of the intervention for each group.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases in May 2012. We conducted updated searches in 2015 ‐ beginning 6 May 2015 and ending 15 May 2015 ‐ and a third updated search, which commenced 10 November 2016 and ended 14 November 2016.

We did not apply any date or language restrictions to our searches. We did not exclude studies on the basis of their publication status. We included abstracts, conference proceedings, and other 'grey literature' if they met the inclusion criteria.

Australian Education Index (ProQuest) ‐ 1979 to current.

Bibliomap ‐ database of health promotion research (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases/Search.aspx).

British Education Index (ProQuest) ‐ 1975 to current.

Campbell Library (http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (Ovid) ‐ 1950 to present.

Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library ‐ 1950 to 2015.

Dissertation Express ‐ cutdown versions of dissertation abstracts (http://dissexpress.umi.com/dxweb/search.html).

Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER) (http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/webdatabases4/Search.aspx).

Embase (Ovid) ‐ 1974 to 2015, week 16.

Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC; ProQuest) ‐ 1966 to current.

EThOS – British Library electronic theses online (http://ethos.bl.uk/AdvancedSearch.do?new=1).

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ‐ Politics & Economics (ProQuest) ‐ 1950 to current.

MEDLINE (Ovid) ‐ 1950 to 6 May 2015.

PsycINFO (Ovid) ‐ 1806 to 2015, week 17.

Sociological Abstracts (CSA) ‐ 1952 to current.

Several of the databases and most of the websites that we searched in May 2012 yielded no or very few studies eligible for inclusion. The few eligible studies identified via these databases or websites were also available through searches of Cochrane CENTRAL, Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. We therefore chose to exclude the following from our updated searches in 2015 and 2016: Bibliomap, Dissertation Express, Clinicaltrials.gov, DoPHER, and EThOS.

The search strategies that we used to search databases can be found in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We carried out handsearches of reference lists of relevant articles to identify additional relevant studies. We contacted experts in the field to identify ongoing research. We carried out citation searches for key studies identified. We also searched the following websites of organisations actively involved in prevention of risk behaviours.

World Health Organization.

UNICEF; United Nations.

World Bank.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

National Institutes of Health.

National Youth Agency.

Foundations: Joseph Rowntree, Nuffield Trust.

National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

Policy organisations ‐ Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co‐ordinating Centre (EPPI Centre), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), Department of Health, University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, The King's Fund, Institute for Public Policy Research.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently carried out the initial screening process for the first 500 publications retrieved to ensure quality and accuracy of the process. We selected a further 10% of studies at random and double‐screened them to ensure that the screening process was consistent and accurate throughout. In May 2012 and May 2015, we conducted this process, which yielded an overall Kappa statistic of 0.83, reflecting high agreement between study authors. We obtained full‐text articles if we required additional information to assess eligibility for inclusion.

We obtained the full texts of eligible articles and, when necessary, grouped together multiple publications arising from a single study. Two review authors screened full‐text papers using a prespecified set of criteria for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by discussion; when disagreements persisted, we consulted a third review author to enable a consensus to be reached.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently used a data extraction form created for this review to extract data from included studies. Two review authors had piloted the data extraction form to ensure that it captured study data and could be used to assess study quality effectively. Data extracted from full text studies included the following.

Lead author, review title, or unique identifier and date.

Study design.

Study location.

Study setting.

Year of study.

Theoretical underpinning.

Context.

Equity (using PROGRESS Plus (see below for details)).

Interventions (content and activities, numbers/types of behaviours addressed, duration of interventions, and details of any intervention offered to the control group).

Participants in the intervention (including number randomised and number included in each intervention group; age at the start of the intervention; and demographic data when possible (e.g. ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status).

Scope of the interventions (universal or targeted to high‐risk or vulnerable groups).

Methods of measurement of risk behaviour (self‐report or objective measure).

Duration of follow‐up(s).

Attrition rate.

Randomisation.

Allocation concealment.

Outcome measures post intervention at each stage of follow‐up (including unit of measurement).

Effect size and precision (e.g. 95% confidence interval).

Whether clustering was taken into account in cluster RCTs and intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC).

Methods of analysis.

Process evaluation (including fidelity, acceptability, reach, intensity, and context of interventions).

Cost‐effectiveness data when provided (e.g. estimates of resource use, source of resources used, estimates and sources of unit costs, price year, currency, incremental resource use and costs, point estimate and measure of uncertainty for incremental resource use, costs and cost‐effectiveness, economic analytical viewpoint, time horizon for costs and effects, and discount rate).

Any other comments.

We used the PROGRESS Plus checklist to collect data relevant to equity. This includes place of residence, race/ethnicity, occupation, gender, religion, education, social capital, and socioeconomic status, with Plus representing the additional categories of age, disability, and sexual orientation. We collected PROGRESS Plus factors reported at baseline and follow‐up when reported. We resolved disagreements between review authors around data extraction by discussion, or by consultation with a third review author when consensus was not reached by discussion alone. We contacted study authors to obtain additional information or data not available from published study reports, when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias of included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2008). For each domain, two review authors rated studies as having 'high', 'low', or 'unclear' risk of bias. We resolved disagreements by discussion and, when necessary, by referral to a third review author. Selection bias included assessment of both adequate sequence generation and allocation concealment. We assessed studies as having low risk of selection bias when study authors reported a clearly specified method of generating a random sequence; and as having low risk of bias associated with lack of allocation concealment when study authors clearly described methods of concealment, such as use of opaque envelopes. We assessed studies as having high risk of performance bias unless study authors explicitly stated that students were blinded to group allocation, although participants could rarely be blinded to the fact that they were participants in an intervention owing to the nature of the studies. When studies clearly stated that outcome assessors were blinded, we judged them as having low risk of bias. When outcomes were assessed by self‐report, we rated studies as having high risk of bias when students were unlikely to have been adequately blinded. To assess attrition bias, we considered rates of attrition both overall and between groups, and we assessed whether this was likely to be related to intervention outcomes. We assessed studies as having low risk of reporting bias when a published protocol or study design paper was available and all prespecified outcomes were presented in the report; or when all expected outcomes were reported. If we had additional concerns, such as baseline imbalance between groups, we noted this in the ‘other bias’ domain.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous (binary) data, we used odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to summarise results within each study. When ORs were not provided, we calculated ORs and their standard errors (SEs) using reported outcome data. When studies reported ORs that represented the opposite measure (e.g. wearing a condom vs not wearing a condom), we took the inverse of the value.

For continuous outcomes, we extracted or calculated mean differences (MDs) based on final value measurements, ensuring that baseline mean values were sufficiently comparable (i.e. both lay within the standard deviations (SDs) for intervention and control). When this was not the case for baseline mean values in each study arm, we excluded data from the meta‐analysis and included them in a table. We calculated a pooled standard deviation from intervention and control SDs at follow‐up and standardised results to a uniform scale by calculating standardised mean differences (SMDs).

When studies reported an outcome as dichotomous and others provided a continuous measure, we converted results to dichotomous data, assuming that the underlying continuous measurement had an approximate logistical distribution, using the methods described in Borenstein 2009 (see Chapter 7). We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of this on study findings.

Unit of analysis issues

Several interventions that were randomised at the school level did not appear to take clustering of participants into account, for instance, by using a multi‐level model or generalised estimating equations. When clustering was not taken into account, and when study authors could not provide adjusted data, we followed the approach suggested in Chapter 16.3.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, to conduct an 'approximately correct analysis' (Bush 1989; Fearnow‐Kenney 2003; Griffin 2009; Ialongo 1999; Ialongo 1999b; Kellam 2014; Li 2011; Lochman 2003a; Lochman 2004a; McNeal 2004; Nader 1999; O'Neill 2011; Sanchez 2007; Shek 2011). We imputed intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) for each outcome, which provide a measure of the relative variability within and between clusters, from other included studies that reported an ICC for the same outcome, to enable the design effect to be calculated. For all analyses, we selected the most conservative ICC for that behaviour. When no ICC was available for that behaviour, we used the largest available ICC for any behaviour to be conservative. We conducted sensitivity analyses, which utilised the lowest reported ICC for the same behaviour. When no ICC was reported, we calculated an average of available ICCs and used this value. A list of the ICCs used in the data analyses is provided in Additional Table 6.

1. Intracluster correlation coefficients.

| Study | Country | Age | Outcome variable | Reported intracluster correlation coefficient | Published or correspondence (comment) |

| ICCs used in primary analyses | |||||

| Gatehouse Study (Bond 2004) | Australia | 13‐14 | Substance use | 0.06 | Published |

| All Stars 2 (Gottfredson 2010) | USA | 11‐14 | Aggression | 0.025 | Published |

| Fourth R (Wolfe 2012) | USA | 14‐15 | Violence | 0.01 | Published |

| All Stars 2 (Gottfredson 2010) | USA | 11‐14 | Delinquency | 0.025 | Published |

| Fourth R (Wolfe 2012) | USA | 14‐15 | Sexual risk behaviour | 0.01 | Published |

| Gatehouse Study (Bond 2004) | Australia | 13‐14 | Diet/physical activity | 0.06 | Publisheda |

| Positive Action (Chicago) (Li 2011) | USA | 8‐13 | Education | 0.1 | Published |

| Gatehouse Study (Bond 2004) | Australia | 13‐14 | Mental illness | 0.01 | Published |

| ICCs used in sensitivity analyses | |||||

| LIFT/All Stars 2 (DeGarmo 2009; Gottfredson 2010) | USA | 10/11‐14 | Substance use | 0.0 | Published |

| All Stars 2 (Gottfredson 2010) | USA | 11‐14 | Aggression | 0.0 | Published |

| Fourth R (Wolfe 2012) | USA | 14‐15 | Violence | 0.01 | Published |

| All Stars 2 (Gottfredson 2010) | USA | 11‐14 | Delinquency | 0.0 | Published |

| Fourth R (Wolfe 2012) | USA | 14‐15 | Sexual risk behaviour | 0.01 | Published |

| All Stars 2, Gatehouse Study, Fourth R, LIFT, Positive Action (Chicago) (Bond 2004; Gottfredson 2010; Wolfe 2012; DeGarmo 2009; Li 2011) |

USA, Australia |

10‐15 | Diet/physical activity | 0.0263 | Publishedb |

| Gatehouse Study (Bond 2004) | Australia | 13‐14 | Education | 0.01 | Publishedc |

| Gatehouse Study (Bond 2004) | Australia | 13‐14 | Mental illness | 0.01 | Published |

ICC: intracluster correlation coefficient.

aThe highest ICC value was used to be conservative.

bAverage ICC value used from across these studies.

cICC related to school engagement.

A very small number of trials did not report the number of participants in each study arm. If it was reported that attrition was comparable between study arms, we divided the total N by two to yield an approximate number for each arm. When we found interventions with multiple study arms, we split the control group to avoid double‐counting, as outlined in Section 16.5.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Dealing with missing data

When we encountered missing or unclear data related to participants or outcomes, we contacted study authors via email. We noted missing data on the data extraction form and took them into account when judging the risk of bias of each study. We excluded from quantitative analyses studies for which insufficient data were available (e.g. in study reports, and when missing data could not be obtained) and included data from study reports in Additional Table 7.

2. Outcomes not included in meta‐analysis.

| Author and year | Study name | Categorisation | Outcome | Authors' conclusions |

| 1. Tobacco use | ||||

| Bonds 2010 | New Beginnings | Family‐Targeted | Tobacco use disorder (including nicotine withdrawal and dependence) | No difference between study arms in the proportion of participants meeting criteria for nicotine use disorder (6.7% in each arm) |

| Bush 1989 | Know Your Body | School‐Universal | Serum thiocyanate (micromoles/L) | Mean difference from baseline to 1 year follow‐up was ‐9.87 (SE 2.5) in the intervention group, and 20.03 (SE 2.68) in the control group (P < 0.001). These data were based on a 50% subsample stratified at baseline, based on measurement after 1 year of intervention. |

| Connell 2007 | Family Check‐Up | Family‐Universal | Nicotine abuse/dependence | Across treatment and control groups, no significant differences were found for nicotine abuse/dependence (Chi² (1, 998) = 3.09, P > 0.05). No significant correlation between assignment to experimental condition(s) and tobacco use over time |

| DeGarmo 2009 | LIFT | School‐Universal | Initiation of tobacco use | With controls for parental drinking and deviant peer association, the intervention was associated with reduced risk of initiation of tobacco use (beta = ‐0.10, P < 0.01). The effect translated to odds ratios of a 10% reduction in risk for tobacco use. |

| Estrada 2015 | Brief Familias Unidas | Family‐Targeted | Tobacco use in past 90 days | Brief Familias Unidas was not significantly efficacious in reducing tobacco use (beta = ‐0.09, P = 0.85) in the past 90 days. |

| Gonzales 2012 | Bridges to High School | Family‐Targeted | Substance use | Study authors report that substance use at follow‐up was less in the intervention group than in the control group for adolescents who engaged in high levels (85th percentile) of baseline substance use (d = 3.65). |

| LoSciuto 1999 | Woodrock Youth Development Project | School‐Universal | Substance use in past month (tobacco, alcohol, drugs) | Mean substance use in the past month was 1.1 for the intervention group and 1.15 for the control group (SMD 0.18) |

| McNeal 2004 | All Stars | School‐Universal | Tobacco use in past 30 days | The teacher‐delivered All Stars programme was associated with reduced rate of growth in 30‐day usage of cigarettes (7.4% to 7.8%) compared to the specialist condition (11.0% to 13.8%) and the control group (15.1% to 17.9%). |

| Olds 1998 | Nurse Family Partnership | Family‐Targeted | Mean cigarettes per day | 15‐year follow‐up: incidence of cigarettes smoked per day in past 6 months among those who received nurse visitation through pregnancy (group 3) was 0.91 compared to 1.30 among control participants (P = 0.49). Among a subgroup of women from low socioeconomic status (SES) households who were unmarried, the comparison was 1.32 vs 2.50 among control participants (P = 0.07). Incidence of cigarettes smoked per day in the past 6 months among those who received nurse visitation until the child's second birthday was 1.28 compared to 1.30 among control participants (P = 0.76). Subgroup analysis of women from low SES households who were unmarried showed that incidence was 1.50 among the intervention group compared to 2.50 among controls (P = 0.1). |

| Perry 2003 | DARE and DARE‐Plus | School‐Universal | Current smoker (growth rate) | Growth curve analysis showed that for boys: the growth rate of tobacco use was 0.31 (0.05) in the control group, 0.28 (0.05) in the DARE group, and 0.18 (0.05) in the DARE Plus group (DARE vs control P = 0.28; DARE Plus vs control P = 0.02; DARE Plus vs DARE P = 0.08). Among girls: the growth rate was 0.28 (0.07) in the control group, 0.25 (0.07) in the DARE group, and 0.22 (0.07) in the DARE Plus group (DARE vs control P = 0.38; DARE Plus vs control P = 0.25; DARE plus vs DARE P = 0.35). |

| Piper 2000 | Healthy for Life | School‐Universal | Tobacco use in past 30 days | The age‐appropriate condition showed no benefit over the control condition at 12‐month follow‐up (prevalence 24% in both arms; HLM coefficient 0.18, SE 0.12, P > 0.1) or at 24‐month follow‐up, where prevalence was higher in the intervention group (prevalence 36% vs 30% in the control group, coefficient 0.41, SE 0.2, P < 0.1). Among those receiving the intensive condition, prevalence was similar in both study arms (12 months: 22% vs 24% in the control group; coefficient ‐0.3, SE 0.17, P > 0.1; 24 months: 28% vs 30% in the control arm; coefficient ‐0.38, SE 0.15, P < 0.05). |

| Saraf 2015 | (none given) | School‐Universal | Tobacco use | Current smoking (in the past month) changed from 13.1% (95% CI 10.2% to 15.9%) to 3.1% (95% CI 0.2% to 5.9%) in the intervention group; and from 7.7% (95% CI 5.0% to 10.4%) to 5.4% (95% CI 2.6% to 8.2%) in the control group (overall difference between groups in pre‐ to post‐change ‐7.7 (‐10.7 to ‐4.7); P < 0.01. |

| Schweinhart 1980 | High/Scope Perry Preschool Study | School‐Targeted | Tobacco use | No impact of the intervention on smoking cigarettes 22 years after the end of the programme: 45% of those in the intervention group smoked compared to 56% of those in the control group (P = 0.231). Effect size 0.22 |

| Tierney 1995 | Big Brothers Big Sisters | Individual‐Targeted | Likelihood of smoking | Those receiving the intervention were reported to be 19.7% less likely to start smoking compared to controls (males receiving Big Brothers Big Sisters were 24.5% less likely to start smoking, and females 9.9%). Males from an ethnic minority receiving Big Brothers Big Sisters had a 29.9% increased likelihood of smoking compared to controls, but among females there was a 1.9% reduction. White males and females receiving the intervention had a 47.9% and 14.7% reduced likelihood of smoking, respectively. |

| Walter 1989 | Know Your Body | School‐Universal | Smoking | Among the schools in Westchester, results showed a beneficial impact of the intervention: the school mean at the end of the intervention was 3.5% (SD 4.3%) compared to 13.1% (SD 5.2) among control schools; P < 0.005. This is equivalent to a 73% reduction in the rate of initiation of smoking. |

| 2. Alcohol use | ||||

| Bonds 2010 | New Beginnings | Family‐Targeted | Alcohol use, binge drinking, age commencing drinking | 15‐year follow‐up: alcohol use in the past month higher in the intervention arm than in the control arm (d = 0.23, 95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.72). Intervention arm commenced drinking at a mean age 0.47 years younger than the control group (95% CI ‐1.31 to 0.23 years). Binge drinking in the past year higher in the intervention group than in the control arm (d = 0.16, 95% CI ‐0.14 to 0.46). |

| Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2010 | Fast Track | School‐Targeted | Binge drinking problem | The intervention marginally decreased binge drinking at 10‐year follow‐up (adjusted OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.01, P = 0.057). |

| Connell 2007 | Family Check‐Up | Family‐Universal | Alcohol use | No significant association was noted between assignment to experimental condition(s) and alcohol abuse/dependence over time (Chi² (1, 998) = 0.98, P > 0.05), with the exception of Time 2, when a correlation between treatment assignment and alcohol use was observed (r = 0.09, P ≤ 0.05). |

| Cunningham 2012 | SafERteens | Individual‐Targeted | Alcohol use | Reduction in the proportion of participants scoring ≥ 3 on AUDIT‐C from 50% at baseline to 34.4% at 3 months and 37.3% at 12 months (‐12.7% change at 12 months; OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.56) for those in the therapist intervention arm; and a reduction from 45.6% at baseline to 32.7% at 3 months and 28.9% at 12 months (‐16.7% change at 12 months; OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.37) for those in the computer arm . For controls, a reduction from 47.7% to 38.1% at 3 months and 34.7% at 12 months was evident (‐13% change at 12 months). |

| Cunningham 2012 | SafERteens | Individual‐Targeted | Binge drinking | Reduction in the proportion of participants reporting any binge drinking from 52.8% at baseline to 34.4% at 3 months and 38.7% at 12 months (‐14.1% reduction at 12 months; OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.36) among those in the therapist group; and a reduction from 48.5% to 28.8% at 3 months and 30.3% at 12 months (‐18.2% reduction; OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.19) among those in the computer group. Similar reductions were seen in the control group: a reduction from 54% at baseline to 34.6% at 3 months and 36.1% at 12 months (‐17.9% reduction at 12 months). |

| Estrada 2015 | Familias Unidas – Brief | Family‐Targeted | Alcohol use | Brief Familias Unidas was not significantly efficacious in reducing alcohol use (beta = 0.17; P = 0.51) in the past 90 days. |

| Friedman 2002 | Botvin Life Skills Training and Anti‐violence | Individual‐Targeted | Degree of alcohol use | Alcohol use was decreased among intervention participants compared to controls (t = ‐1.24, P > 0.05). |

| Gonzales 2012 | Bridges to High School | Family‐Targeted | Substance use | Study authors report that substance use was less at follow‐up in the intervention group compared to the control group for adolescents who engaged in high levels (85th percentile) of baseline substance use (d = 3.65). |

| Jalling 2016 | Comet 12‐18 | Family‐Targeted | Alcohol use (AUDIT score) | No significant difference was found between groups: at T2, mean AUDIT score was 7.59 (SD 7.60) in the intervention group vs 6.26 (SD 6.79) in the control group. |

| Jalling 2016b | ParentSteps | Family‐Targeted | Alcohol use (AUDIT score) | No significant difference was found between groups: at T2, mean AUDIT score was 5.10 (SD 6.38) in the intervention group vs 6.26 (SD 6.79) in the control group. |

| Kellam 2008 | Good Behaviour Game | School‐Universal | Lifetime alcohol abuse/ dependence | The Good Behaviour Game (GBG) was associated with a reduction in lifetime alcohol abuse/dependence disorders compared to control: 13% for GBG vs 20% for controls (P = 0.08). The effect was similar for males and females. |

| Murry 2014 | SAAF | Family‐Targeted | Escalation of alcohol use | Study authors report through structural equation modelling analysis that youth avoidance of risk opportunity situations served a role in delaying initiation and escalation of use of alcohol and other substances as they transitioned from early to late adolescence. |

| Monti 1999 | Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention | Individual‐Targeted | Alcohol use score | With a 2 × 2 (group × time) repeated measures analysis of variance, time effect showed reductions in alcohol scores (F(1,79) = 24.55, P < 0.001) with no group differences or interactions. |

| Olds 1998 | Nurse Family Partnership | Family‐Targeted | Alcohol use | 15‐year follow‐up: incidence of days drunk alcohol in past 6 months among those who received nurse visitation through pregnancy (group 3) was 1.81 compared to 1.57 among control participants (P = 0.97). Among a subgroup of women from low socioeconomic status (SES) households who were unmarried, the comparison was 1.84 vs 2.49 among control participants (P = 0.41). Incidence of days drunk alcohol in past 6 months among those who received nurse visitation until the child's second birthday was 1.87 compared to 1.57 among control participants (P = 0.96). Subgroup analysis of women from low SES households who were unmarried show the incidence was 1.09 among the intervention group compared to 2.49 among controls (P = 0.03). |