Summary

Background

Young people require specific attention when it comes to suicide prevention, however efforts need to be based on robust evidence.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of all studies examining the impact of interventions that were specifically designed to reduce suicide-related behavior in young people.

Findings

Ninety-nine studies were identified, of which 52 were conducted in clinical settings, 31 in educational or workplace settings, and 15 in community settings. Around half were randomized controlled trials. Large scale interventions delivered in both clinical and educational settings appear to reduce self-harm and suicidal ideation post-intervention, and to a lesser extent at follow-up. In community settings, multi-faceted, place-based approaches seem to have an impact. Study quality was limited.

Interpretation

Overall whilst the number and range of studies is encouraging, gaps exist. Few studies were conducted in low-middle income countries or with demographic populations known to be at increased risk. Similarly, there was a lack of studies conducted in primary care, universities and workplaces. However, we identified that specific youth suicide-prevention interventions can reduce self-harm and suicidal ideation; these types of intervention need testing in high-quality studies.

Keywords: Suicide prevention, Self-harm, Young people, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Highlights

-

•

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the full spectrum of youth suicide prevention approaches.

-

•

Findings suggest that interventions designed to reduce suicide risk in young people can be effective.

-

•

Interventions delivered in clinical, educational and community settings appear to reduce self-harm and/or suicidal ideation.

-

•

The quantity and range of studies identified is encouraging, suggesting increased attention and investment in this area.

Research in Context

Evidence Before This Study

Prior to this study systematic reviews in suicide prevention have been limited by either only including RCTs, or by concentrating on particular settings (e.g., schools) or intervention type (e.g., gatekeeper training), and as such do not cover the full spectrum of approaches. The more comprehensive systematic reviews do not focus specifically on youth.

Added Value of This Study

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to synthesize the full spectrum of suicide prevention approaches in young people. It identified a large number of studies conducted across clinical, educational/workplace and community settings. Studies also tested the full spectrum of interventions including universal means restriction and educational interventions, selective interventions such as training programs, indicated interventions such as cognitive or dialectical behavior therapy, and multimodal interventions that combined education with either screening or gatekeeper training. The meta-analysis found that interventions delivered in both clinical and educational settings appear to have an impact on suicide-related outcomes at post-intervention and follow-up. In community settings, multi-faceted, place-based approaches seem to have an impact on rates of suicide and self-harm. Overall, study quality was limited.

Implications of All the Available Evidence

The review identified that specific youth suicide-prevention interventions can reduce both self-harm and suicidal ideation in clinical, school and community settings, challenging the nihilism that often pervades in suicide prevention. Indeed, the number and range of studies identified by this review is encouraging and reflects increasing investment and best practice internationally when it comes to youth suicide prevention. However, there was an absence of studies conducted in low-middle income countries where large numbers of suicides occur, or with specific populations known to be at elevated risk of suicide, such as indigenous or same-sex attracted young people. Similarly, few studies were conducted in primary care, workplace or university settings, and very few utilized digital platforms. Additionally, many studies simply tested interventions that had previously been designed for adults as opposed to young people specifically. Together these findings suggest that important opportunities for youth suicide prevention are currently being missed. These gaps now need to be addressed by researchers, research funders, and by policy makers if we are to successfully address the rising rates of suicide among young people worldwide.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among young people and rates appear to be increasing [1]. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors (defined as suicide attempt or self-harm with clear or unclear suicidal intent) are more common than suicide [2] and predict future suicide and suicide attempts [3], with the period following a first suicide attempt associated with highest risk [4]. Presenting to hospital with self-harm significantly predicts subsequent suicide in youth [5]; with the period immediately following discharge from psychiatric inpatient treatment associated with highest risk for suicide [6]. The period following hospital discharge therefore provides a crucial opportunity for intervention. Suicidal ideation is a necessary precursor to suicide attempt and as such also requires intervention. Although suicidal ideation is arguably a distinct concept from suicidal behavior, for ease of reading it is included under the term “suicide-related behavior” throughout this review unless otherwise specified.

The majority of OECD countries have a national suicide prevention strategy and many identify young people as requiring specific attention [7], [8], [9]. In accordance with international best practice, most strategies recommend a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention spanning universal approaches (i.e., delivered to the whole population), selective approaches (i.e., delivered to groups or communities believed to be at higher risk of suicide) and indicated approaches (i.e., delivered to individuals displaying suicide-related behaviors). Strategies also recommend interventions operate across a range of settings, including clinical, educational, workplace and community settings [1]. More recently, strategies have called for interventions to be delivered in digital, as well as face-to-face, settings [10], [11].

Strategies must encompass evidence-based interventions if they are to reduce suicide [1]. Generating such evidence in suicide prevention, however, is complex [12]. Statistically, suicide is a relatively rare event, therefore it is often unfeasible to obtain sample sizes necessary to demonstrate the impact of interventions on this outcome. Moreover, many interventions do not lend themselves to being tested using randomized controlled trials (RCTs), typically considered the gold-standard [13]. As such, researchers assess changes in other more prevalent outcomes, including self-harm and suicidal ideation, using alternative study designs. Therefore, when synthesizing the evidence regarding what works in youth suicide prevention, alternative study designs warrant consideration.

Whilst previous reviews have synthesized this evidence, many only include RCTs [14]. Additionally, many concentrate on particular settings (e.g., schools) [15], or types of intervention (e.g., gatekeeper training programs) [16], and as such do not cover the full spectrum of approaches. Finally, systematic reviews that include a range of study designs and intervention types do not focus specifically on youth [17], [18]. Hence, a comprehensive review of the literature on youth suicide prevention interventions spanning the range of settings, study designs and intervention types, is required to better understand what works in youth suicide prevention. This will help policy makers, clinicians, service providers and commissioners determine the focus of future suicide prevention efforts.

We conducted a systematic review and, where possible, meta-analysis, of all studies examining the impact of interventions that were specifically designed to reduce suicide-related behavior in young people. Overcoming the limitations of previous reviews, we placed no restriction on study setting, intervention approach, or study design.

2. Methods

The methodology was informed by the Cochrane Collaboration [19] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [20].

2.1. Study Selection and Classification

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies of any design were eligible for inclusion in this review, provided they: [1] evaluated the impact of an intervention specifically designed to reduce suicide-related behavior; [2] assessed a suicide-related outcome, including suicide, suicide attempt, self-harm (defined as intentional self-injury and/or self-poisoning where suicidal intent was either not specified or was unclear), suicidal ideation, suicide risk, and/or reasons for living; [3] targeted young people aged 12–25 and/or if data on young people (mean age between 12·0 and 25·0) was specifically reported; [4] were published in a peer-reviewed journal or identified via the reference lists of included articles; and [5] were written in English.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded from the review if: [1] they were not implemented with the expressed and primary purpose of preventing or reducing suicide-related behavior. Under this criterion, studies of indicated interventions were excluded if they did not recruit participants based on present or recent suicidal ideation or behavior. Additionally, studies of means restriction approaches were included only if the intervention was implemented, wholly or partially, to prevent suicide. As such, studies of firearm regulations implemented with the expressed and primary purpose of preventing homicide were excluded under this criterion. Studies were also excluded if they: [2] did not measure and report on a suicide-related outcome (as defined above); this included studies that exclusively measured non-suicidal self-injury, as this is generally considered to be a separate phenomenon; [3] did not target young people, or if data relating to outcomes for young people could not be disaggregated from that adults; [4] employed a non-experimental design; [5] were not published in a peer-reviewed journal; [6] were not available in English; or [7] did not contain any unique relevant data over and above the first included study.

2.2. Search Strategy

We searched Medline, PsycINFO, and EMBASE from January 1 1990 to September 21, 2017. Keywords relevant to suicide-related behavior, intervention type and youth were combined using standard Boolean operators (see Appendix). Key words were developed by consensus among the author group and in consultation with a librarian. In addition, we hand-searched the reference lists of all previous reviews retrieved via the search.

In the first instance study titles and abstracts were screened by five of the review authors (EB, JR, SH, NS, KW). Due to the large number of studies retrieved two review authors independently screened 10% of the total number of records retrieved. Cohen's Kappa [21] was 0·748 and Prevalence-Adjusted and Bias-Adjusted Kappa (PABAK [22]) was 0·978, indicating excellent agreement regarding inclusion and exclusion of studies. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. In the second stage of screening, full texts of potentially relevant studies were screened for inclusion by four authors (EB, JR, SH, NS). Full text double-screening was not undertaken, but review authors met regularly to resolve any queries.

2.3. Data Extraction and Classification

Data were extracted independently by seven authors (JR, EB, SH, NS, KW, DC, AM) using a pilot tested pro forma. The following information was extracted: (i) author(s) and publication date; (ii) country; (iii) study design; (iv) setting from which participants were recruited; (v) study sample or population characteristics; (vi) intervention description; (vii) details of control or comparison group (classified as treatment as usual (TAU), enhanced TAU and placebo), and; (viii) outcome data on suicide deaths, suicide attempt, suicidal ideation, suicide-related behavior, and/or self-harm at the point of post-intervention and (where appropriate) longest follow-up (note that follow-up periods varied). Where studies used more than one measure for an outcome, data from the measure that was most commonly used across all included studies were used, as has been done previously [23]. Two authors (SH and KW) undertook double data entry of all outcome data.

Studies were classified according to the following taxonomy. In the first instance studies were classified according to the setting from which the participants were recruited (i.e. clinical, education or workplace, and community). If participants were recruited from multiple settings, the study was classified according to the setting from which participants were primarily recruited. Studies were then classified by study design (i.e. RCTs and non-RCTs) and then by intervention approach (i.e. universal, selective, indicated). Some studies combined a number of different intervention approaches. In these cases studies were classified as ‘multi-modal’ when the intervention comprised a number of different components implemented together (e.g. psycho-education AND screening), and ‘multiple’ when studies tested the impact of different interventions that were implemented separately (e.g. psycho-education program in location A and gatekeeper training in location B). They were then classified according to intervention type (e.g. means restriction, educational, therapeutic). For the therapeutic interventions, the therapeutic modality itself was also specified. For example, within this category there were a number of studies that tested cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) and so on.

2.4. Study Quality

An assessment of study quality was conducted. For all RCTs, this was assessed based on the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool [19]. In the majority of trials, as is often the case [24], blinding of participants and therapists was not possible. Each trial was therefore assessed with regard to random sequence generation, allocation concealment, ascertainment of self-harm, outcome assessor blinding, whether analyses were conducted according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, and rates of attrition. For the latter criterion, an attrition rate of 15% or less on the primary outcome at the longest follow-up point indicated low risk of bias.

Non-RCTs were assessed in two ways. For those conducted in clinical, educational, or workplace settings (where a range of study designs were employed) we used a set of criteria based on resources from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) group [25]. We assessed whether or not: [1] the study was adequately powered; [2] outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation (for studies where outcomes were measured via interview); [3] the attrition rate was below 15%; and [4] the authors used statistical testing to measure change.

Studies in community settings employed either an ecological or interrupted time series design. Here two criteria were used to assess quality: whether or not data were collected at multiple time points before and after the intervention [26], and whether or not the intervention itself was likely to affect data collection. “Multiple time points” was defined as at least twice before or after implementation of the intervention. The intervention was considered not to affect data collection if sources and methods of data collection were the same before and after the intervention, or if data were collected from official sources (e.g. coronial records).

2.5. Data Synthesis

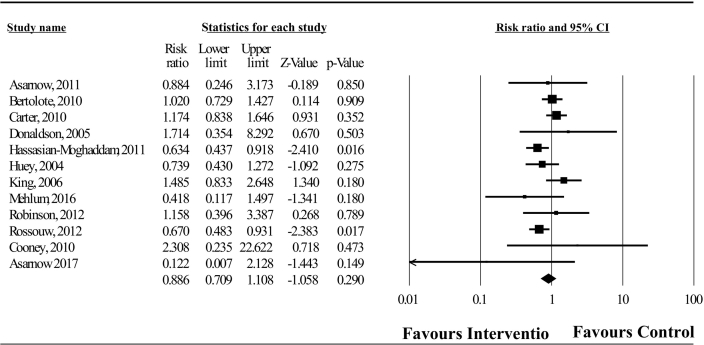

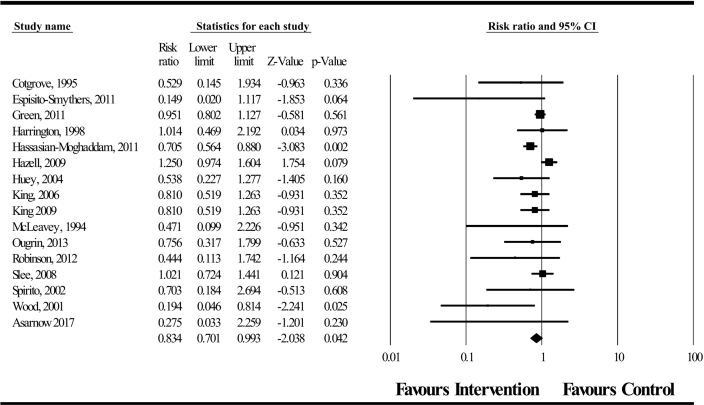

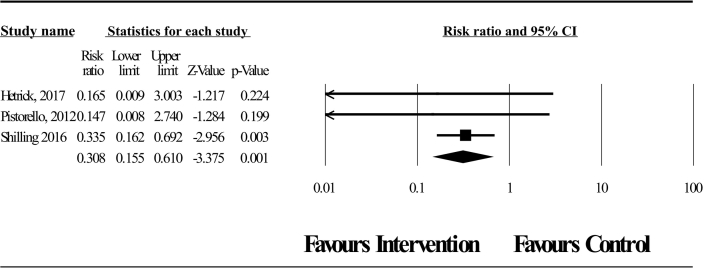

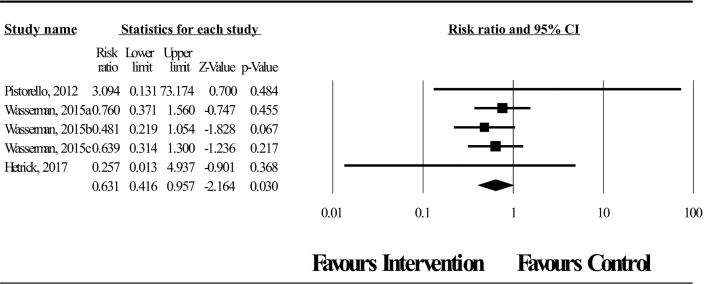

Meta-analysis was only conducted for RCTs. We analyzed data separately according to study setting. Because self-harm can encompass suicide attempts, is a key predictor of future suicide [27], and is more prevalent and more commonly assessed than suicide, self-harm (measured dichotomously) was our primary outcome and all dichotomous self-harm and suicide attempt data were combined. Additional outcomes were self-harm measured continuously, suicide and suicidal ideation (measured dichotomously and continuously). Where studies had more than one intervention arm, we included those arms that provided relevant data and split the control group to avoid double counting [28].

For dichotomous data, we pooled data between studies using the relative risk with 95% confidence interval. For continuous outcomes, given the range of different tools used, means and standard deviations were pooled using the standardized mean difference (SMD) using the Hedges' adjusted g with a 95% confidence interval. SMD effect sizes of 0·2 were considered small, 0·5 were considered medium, and ≥ 0·8 were considered large [29]. Measurement scales were standardized so that higher scores were indicative of greater levels of suicidal ideation. For both continuously- and dichotomously-measured outcomes, pooled effect size estimates were calculated using the DerSimonian-Laird random effects model [30] implemented using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 2·2·064 software [31].

Between-study heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistic. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% or larger are indicative of small, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively [32].

2.5.1. Subgroup Analysis

For the primary outcome we undertook three subgroup analyses to investigate whether the intervention approach, intervention type and, for those interventions coded as psychotherapy, the therapeutic modality modified the pooled effect sizes.

First, intervention approach was coded as universal, selective or indicated. Second, type of intervention was categorized as psychotherapy, brief contact, or educational. Psychotherapy interventions were established psychotherapeutic approaches belonging to a particularly theoretical or philosophical school. Brief contact interventions were defined as those interventions that either: [1] focused on maintaining contact or facilitating re-engagement with services via a minimal amount of supportive contact, including provision of an emergency or crisis card as defined by Milner et al. [33]; or [2] interventions delivered within a very brief period, such as screening and referral or provision of one-off assessment and supportive therapy. Educational interventions delivered psycho-education about suicide-related behaviors, mental illness associated with these behaviors, signs and symptoms to look out for and advice on how to respond. Finally, trials coded as psychotherapy were further categorized by modality as either: CBT; DBT; mentalisation therapy; problem solving; motivational interviewing; supportive therapy; family therapy; interpersonal psychotherapy; combined (where several modes of psychotherapy were combined); or other (where the intervention did not clearly fit any category of named therapeutic approach).

2.5.2. Sensitivity Analysis

The robustness of results of the meta-analysis was checked for the primary outcome by conducting sensitivity analyses. RCTs judged as high or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment, and RCTs where more than 15% of participants were lost to follow-up or where no data were reported, were excluded from this analysis.

For studies in which no data amenable to meta-analysis were reported, a narrative synthesis of results was conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

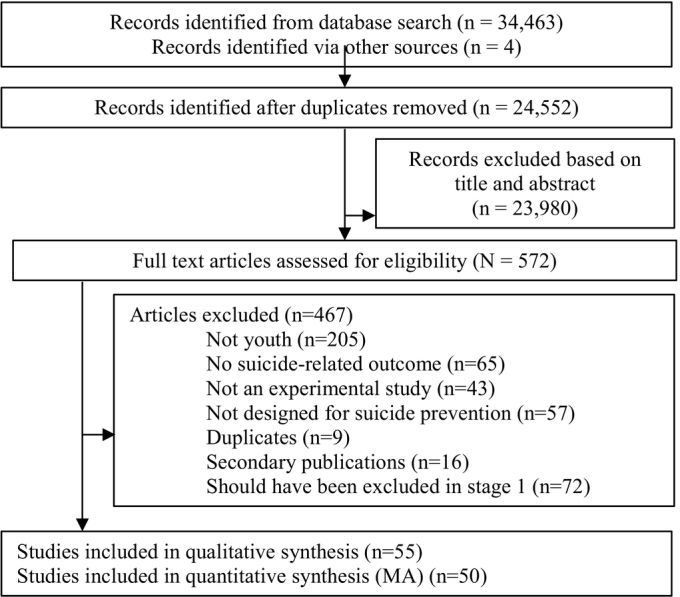

In total, 34,463 articles were retrieved via database searching and an additional four via the reference lists of included articles. Following initial screening, 572 full-text articles were retrieved, of which 105 met our inclusion criteria. Six were secondary publications that were included as they reported novel data [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39]. The review therefore includes findings from 105 articles corresponding to 99 unique studies (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Overall Description of Included Studies

Half (52·5%) of included studies were conducted in clinical settings (Table 1, Table 2), 31 (31·3%) in educational or workplace settings (Table 3, Table 4), and 16 (16·2%) in community settings (Table 5, Table 6). Most studies tested indicated interventions (k = 66; 66·7%), followed by universal (k = 17; 17·2%), multimodal (k = 11; 11·1%), and selective (k = 2; 2·0%) interventions. Three studies (3·0%) evaluated multiple interventions. Forty-eight studies (48·5%) were RCTs. This included 33 (63·5%) of the studies conducted in clinical settings and 15 (48·4%) of those conducted in educational or workplace settings. None of the community-based studies were RCTs.

Table 1.

Randomized controlled trials conducted in clinical settings (N = 33).

| Study; country | Target population | Participants | Intervention description | Comparison condition | Risk of bias | Suicide related outcome(s) assessed; longest follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alavi et al. (2013) [41] Iran |

Inclusion: Young people admitted to hospital for a SA Exclusion: SH w/o intent; no current SI; inability to participate in psychotherapy; diagnosed with bipolar, psychosis, pervasive developmental or substance use disorders Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 30 Mean age: 16.1 (SD: 1.4; Range: 12–18 Gender: 10% male Treatment group N = 15 Mean age: 16.1 (SD: 1.6) Gender: 6.7% male Control group N = 15 Mean age: 16.0 (SD: 1.2) Gender: 13.3% male |

Individual cognitive behavioral therapy plus TAU Length: 12 sessions over 3 months Developed by: Stanley et al. (2009)a Delivered by: NR |

TAU: routine psychiatric intervention and follow up; pharmacotherapy if needed. | Random sequence generation method: Alternate allocation Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Self-report Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

SI (continuous): Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI) Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Asarnow et al. (2011) [65] USA |

Inclusion: Young people who presented to ED with SA or SI Exclusion: Acute psychosis or other symptoms that impede consenting and/or assessment process Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 181 Mean age: 14.7 (SD: 2.0; Range: 10–18) Gender: 30.9% male Treatment group N = 89 Mean age: 14.8 (SD: 2.1) Gender: 33.7% male Control group N = 92 Mean age: 14.6 (SD: 1.9) Gender: 28.3% male |

Brief contact intervention Compliance enhancement measures mixed with family therapy plus TAU Length: 1 month Developed by: Based on Rotheram-Borus et al. (1996)b and adapted by authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

Enhanced TAU: usual ED care, with staff education on linking to treatment, reducing access to means, risks of substance use. | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated algorithm Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate for SH at post-intervention: Yes (11.6%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (dichotomous): DISC-IV, an clinician administered diagnostic interview SA (dichotomous): DISC-IV, an clinician administered diagnostic interview and Harkavy Asnis Scale (HASS) Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Asarnow et al. (2017) [42] USA |

Inclusion: i) Young people who had presented after engaging in SH (SA or NSSI included) within the last three months; ii). history of repetitive SH (≥ 3 lifetime episodes) Exclusion: symptoms interfering with participation in assessments or intervention (psychosis, substance use) and inability to speak English Recruited from: Hospital/ED and MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 42 Mean age: 14.62 (SD: 1.83) Gender: 11.9% male Treatment group N = 20 Mean age: 14.35 (SD: 1.81) Gender: 10.0% male Control group N = 22 Mean age: 14.86 (SD: 1.86) Gender: 13.6% male |

SAFETY program Combined intervention consisting of CBT and DBT informed family intervention that included formulation driven CBT, DBT and family centered interventions. Each family had two therapists: one for the young person and one for the parents and there were joint family sessions as well as separated sessions. Length: 12 sessions over 3 months Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

Enhanced TAU: in-clinic parent education on risk of repetition, accessing treatment; 3 + phone-calls monitoring safety, encouraging treatment attendance. | Random sequence generation method: Computerized randomization program Allocation concealment method: Enrolment and assessment staff masked to randomization status Ascertainment of DSH repetition: Self-report Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (23.8% for self-reported outcomes) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SA (dichotomous): used a slight modification of the clinician administered Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Bertolote et al. (2010) [66]; Fleischmann et al. (2008) [34] Multi-national |

Inclusion: Young people who presented to ED following SH/self-poisoning Exclusion: ‘any clinical condition(s) that would disallow interview’ Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 1867 Mean age: NR (Median = 23.0) Gender: 41.8% male Treatment group N = 922 Mean age: NR Gender: 40% male Control group N = 945 Mean age: NR Gender: 43.3% male |

Brief contact intervention 1 1-hour information session plus 9 phone calls or visits. Length: Up to 10 contacts over 18 months Developed by: study authors (based on existing BIC methods) Delivered by: doctor, nurse or psychologist |

TAU: varied between sites, primarily acute injury management with or without mental health referral. | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (11.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

SA (dichotomous): European Parasuicide Study Interview Schedule (EPSIS) of the WHO/EURO Multicenter Study on Suicidal Behavior Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Byford et al. (1999) [43] UK |

Inclusion: Diagnosis of SH (self-poisoning) Exclusion: Overdose was accidental; psychiatric condition which would preclude engagement with therapy; social situation precluded engagement with family therapy Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 162 Age/gender: NR Treatment group N = 85 Age/gender: NR Control group N = 77 Age/gender: NR |

Individual family therapy plus TAU Length: 1 ½ hour assessment plus 1 h of therapy Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: routine assessment and psychiatric care in outpatient clinic. | Random sequence generation method: Shuffled cards Allocation concealment method: Sealed envelope Ascertainment of SH repetition: interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (8.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

SI (continuous): Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ) Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Carter et al. (2010) [44] Australia |

Inclusion: Females referred for treatment following self-poisoning, meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder, with at least three self-reported episodes of self-harm over the preceding year. Exclusion: Males, those engaging in self-injury without self-poisoning Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 70 Mean age: 24.5 (SD: 6.1; Range: 18–65) Gender: 0% male Treatment group N = 37 Mean age: 24.5 (SD: 6.1) Control group N = 33 Mean age: 24.7 (SD: 6.2) |

Dialectical behavior therapy Individual and group therapy, with telephone coaching. Length: number of sessions not specified, delivered over six months Developed by: based on Linehan et al. (1991)c Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU + Waitlist: 6 month period of unspecified TAU while waitlisted. | Random sequence generation method: Shuffled envelopes Allocation concealment method: Sealed, opaque envelopes Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Mixed methods |

SH (continuous): Linehan's Lifetime Parasuicide Count–2; Parasuicide History Interview SH (dichotomous): Linehan's Lifetime Parasuicide Count–2; Parasuicide History Interview Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Cooney et al. (2010) [45] New Zealand |

Inclusion: History of at least one SA or one episode of SH in past three months Exclusion: i) Intellectual disability; ii) Psychosis Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 29 Mean age: 15.9 (SD: 1.0; Range: 14–18) Gender: 24.1% male Treatment group N = 14 Mean age: 16.2 (SD: 0.98) Gender: 28.6% male Control group N = 15 Mean age: 15.7 (SD: 1.1) Gender: 20% male |

Individual plus group dialectical behavioral therapy Length: weekly sessions for approximately 26 weeks Developed by: based on Linehan (1993)d & Miller et al. (2007)e Delivered by: MH professional |

TAU: type and duration varied: CBT, motivational interviewing, supportive counseling, family therapy; medication and case management as needed. | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated algorithm Allocation concealment method: Sealed, opaque envelopes Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Mixed methods |

SI (continuous): BSSI SA (dichotomous): Linehan's Suicide Attempt-Self-Injury Interview (SASII) Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Cotgrove et al. (1995) [67] UK |

Inclusion: Admitted to hospital following SA/SH Exclusion: Records of the original SA were missing, or were there insufficient follow-up data (p. 572) Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 105 Mean age: 14.9 (SD: NR; Range: 12.2–16.7) Gender: 15.2% male Treatment group N = 4 Age/gender: NR Control group N = 58 Age/gender: NR |

Brief contact intervention Emergency card allowing readmission to hospital on request. Length: NA Developed by: based on Morgan et al. (1993)f Delivered by: NA |

TAU: standard follow-up care per ED site. | Random sequence generation method: Open random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Use of an open random numbers table suggests allocation could not have been concealed Ascertainment of SH repetition: Hospital and clinical notes Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

SA (dichotomous): information collected from clinic and hospital records, and contacting general practitioners and other health professionals involved with young person Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Diamond et al. (2010) [46]g USA |

Inclusion: i) Scored > 31 on the SIQ-JR (Reynolds, 1987)h; ii) score remained elevated 2 days later following a second screen. Exclusion: i) Current psychosis; ii) mental retardation/history of borderline intellectual functioning Recruited from: Hospital/ED and primary care practices (75.0% were recruited from primary care and 25.0% from hospitals/EDs) |

Whole sample N = 66 Mean age: 15.2 (SD: 1.62; Range 12–17) Gender: 16.7% male Treatment group N = 35 Mean age: 15.1 (SD: 1.41) Gender: 8.6% male Control group N = 31 Mean age: 15.3 (SD; 1.83) Gender: 25.8% male |

Individual family therapy plus TAU Length: Up to 15 sessions delivered over a 3-month period Developed by: study authors Delivered by: trained PhD or Masters level therapists |

Enhanced TAU: safety monitoring and facilitated referrals for treatment (incl. Individual, group, or family therapy, or case management). | Random sequence generation method: Adaptive randomization Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: No Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): SIQ-Junior (SIQ-JR) SI (dichotomous): SIQ-JR Longest follow-up: 3 months post-intervention |

| Donaldson et al. (2005) [47] USA |

Inclusion: Presented to general pediatric child psychiatric hospital after SA. Exclusion: Current psychosis Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 39 Mean age: 15.0 (SD: 1.7; Range: 12–17) Gender: 18% male Treatment group: N = NR Age/gender: NR Control group: N = NR Age/gender: NR |

Individual skills-based therapyi by trained therapists Length: 12 sessions delivered over 6 months Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: Trained therapists |

Enhanced TAU: Supportive Relationship Treatment (SRT). | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (20.5%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SI (continuous): SIQ SA (dichotomous): Structured adolescent follow-up interviews Longest follow-up: 6 months post-baseline |

| Esposito-Smythers et al. (2011) [48] USA |

Inclusion: SA in past 3 months or scored > 41 on the SIQ (Reynolds, 1987) Exclusion: Verbal IQ score < 70; ii) Psychosis; iv) Bipolar disorder; iv) Dependent on substances other than alcohol or cannabis Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 40 Mean age: 15.7 (SD: 1.19; Range: 13–17) Gender: 33.3% male Treatment group N = 20 Mean age: 15.8 (SD: 0.98) Gender: 31.6% male Control group N = 20 Mean age: 15.7 (SD: 1.41) Gender: 35.3% male |

Individual cognitive behavioral therapy Length: 24 sessions delivered over 12 months Developed by: based on Donaldson et al. (2005) and Esposito Smythers et al. (2006) and adapted by study authors Delivered by: Trained therapists |

Enhanced TAU: treatment schedule and approach determined by community providers. Diagnostic evaluation report provided. Study psychiatrist assisted with medication management. Access to information and resources. | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated adaptive randomization Allocation concealment method: Unclear Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Assessors could guess allocation due to offhand comments made by participants during interviews Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (25.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): SIQ SA (dichotomous): Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (K-SADS) – clinician administered diagnostic interview. Longest follow-up: 6 months post-intervention |

| Green et al. (2011) [49] UK |

Inclusion: Presented to child and adolescent services with at least two episodes of SH in the past 12 months Exclusion: i) Severe low weight anorexia nervosa; ii) psychosis; iii) learning disability Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 366 Mean age: NR (Range: 12–16) Gender: 11.5% male Treatment group N = 183 Mean age: NR Gender: 11.5% male Control group N = 183 Mean age: NR Gender: 11.5% male |

Group cognitive behavioral therapy Length: 6 sessions during the acute phase & as many sessions needed during the maintenance phase Developed by: based on Wood et al. (2001) Delivered by: Trained therapists |

TAU: routine care provided by local child & adolescent mental health services according to clinical judgment, excluding group interventions. | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated minimization algorithm Allocation concealment method: Independent, off-site researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (4.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SI (continuous): SIQ-JR SI (dichotomous): SIQ-JR SH (dichotomous): SIQ-JR Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Harrington et al. (1998) [50]j UK |

Inclusion: Presented to hospital with self-poisoning Exclusion: i) Other SH (e.g. cutting); ii) Severe suicidality; iii) clinician determined risk of contraindication for family treatment, e.g. psychosis, currently receiving psychiatric treatment, parent/child had a learning difficulty Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 162 Mean age: 14.5 (SD: 1.15; Range: 10–16) Gender: 10.5% male Treatment group N = 85 Mean age: 14.4 (SD: 1.2) Gender: 10.6% male Control group N = 77 Mean age: 14.6 (SD: 1.1) Gender: 10.6% male |

Five sessions of family therapy plus TAU Length: NR Developed by: study authors Delivered by: 2 experienced masters'-level child psychiatric social workers |

TAU: routine psychiatric aftercare including diverse range of interventions, but no home-based family interventions. | Random sequence generation method: Shuffled envelopes Allocation concealment method: Sealed, opaque envelopes Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Attempted but not always possible Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (8.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SI (continuous): SIQ SI (dichotomous): SIQ Suicide: NR Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Hassanian-Moghaddam et al. (2011) [68] Iran |

Inclusion: Presented to hospital with self-poisoning Exclusion: Psychosis Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 2133 Mean age: 24.1 (SD: 8.11; Range: NR) Gender: 33.7% male Treatment group N = 1043 Mean age: 24.7 (SD: 7.97) Gender: 33.3% male Control group N = 1070 Mean age: 24.1 (SD: 8.25) Gender: 34% male |

Brief contact intervention (Postcards from Persia) plus TAU. Length: 8 postcards mailed over 12 months Developed by: based on Carter et al. (2005)k Delivered by: NA |

TAU: follow-up care for self-poisoning in Tehran is “poor”, contact is mainly hospital- or office-based. | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Allocation was concealed, but information on the method used was not provided Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: No Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (8.1%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SI (continuous): follow-up interview SI (dichotomous): follow-up interview SH (continuous): follow-up interview SH (dichotomous): follow-up interview SA (continuous): follow-up interview SA (dichotomous): follow-up interview Suicide: mortality records Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Hazell et al. (2009) [51] Australia |

Inclusion: Presented to hospital with > 2 episodes of SH Exclusion: i) Acute psychosis; ii) intellectual disability Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 72 Mean age: 14.5 (SD: 1.1; Range 12–16) Gender: 9.7% male Treatment group N = 35 Mean age: 14.6 (SD: 1.1) Gender: 8.6% male Control group N = 37 Mean age: 14.4 (SD: 1.2) Gender: 10.8% male |

Group based cognitive behavioral therapy (Moving on from self-harm) plus TAU Length: 6 sessions over 12 months Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: routine care varied but generally included individual/family counseling, medication assessment, and care-coordination. | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a computer generated random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent, offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Mixed methods |

SI (continuous): SIQ SH (dichotomous): Linehan's Parasuicide History Interview Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| Huey et al. (2004) [52] USA |

Inclusion: Presented to hospital with SA/SI Exclusion: Autism spectrum disorder Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 156 Mean age: 12.9 (SD: 2.1; Range 10–17) Gender: 35% male Treatment group N = Unclear Age/gender: NR Control group N = Unclear Age/gender: NR |

Multi-systematic family therapy Length: Unclear Developed by: Henggeler et al. (2002)l Delivered by: MH professionals |

Active placebo: hospitalization at youth inpatient psychiatric unit. | Random sequence generation method: NR Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Unclear Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

SI (dichotomous): Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) SA (dichotomous): Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) Longest follow-up: 12 months post-intervention |

| Husain et al. (2014) [53] Pakistan |

Inclusion: Admitted to hospital following SH Exclusion: i) dementia; ii) substance misuse; iii) organic mental disorder; iv) delirium; v) alcohol and/or drug dependence; vi) schizophrenia; vii) bipolar disorder; viii) intellectual disability Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 221 Mean age: 23.1 (SD: 5.5; Range: 16–64) Gender: 31.2% male Treatment group N = 108 Mean age: 23.2 (SD: 5.8) Gender: 29.6% male Control group N = 113 Mean age: 23.1 (SD: 5.3) Gender: 32.7% |

Individual cognitive behavioral therapy (Life After Self-harm) plus TAU Length: 6 sessions over 3 months Developed by: based on Schmidt & Davidson (2004)m and adapted by study authors Delivered by: masters-level psychologists |

TAU: standard routine care provided by local services. | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent, offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (3.6% by the 6-month follow-up period; could not calculate for final follow-up) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): BSSI Suicide: Not stated Longest follow-up: 6 months post-baseline |

| King et al. (2006) [54] USA |

Inclusion: i) SA or severe SI in past 3 months ii) Score of 20 or 30 on the Self-Harm subscale of the Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale (Hodges, 1989)n Exclusion: i) Severe intellectual disability; ii) Psychosis Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 289 Mean age: 15.3 (SD: 1.5; Range: 12–17) Gender: 31.8% male Treatment group N = 151 Mean age: 15.4 (SD: 1.5) Gender: 31.1% male Control group N = 138 Mean age: 15.2 (SD: 1.4) Gender: 32.6% male |

Supportive intervention Youth nominated support team Version 1 plus TAU One-off brief psycho-education intervention for support team plus up to 9 contacts per week between adolescent and support team Length: 1.5 to 2 h Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professional |

TAU: varied, included psychotherapy, medication, alcohol/drug treatment, partial hospitalization, and community services. | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: No Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (18.3%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): SIQ-JR SI (dichotomous): SIQ-JR SA (dichotomous): Not stated Longest follow-up: 6 months post-baseline |

| King et al. (2009) [55] USA |

Inclusion: SA or severe SI in past 4 weeks Exclusion: NR Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 448 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.31; Range: 13–17) Gender: 28.8% male Treatment group N = 223 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.24) Gender: NR Control group N = 225 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.37) Gender: NR |

Supportive intervention Youth nominated support team Version 2 plus TAU One-off, individual or group-based (as preferred) psycho-education session plus weekly telephone contacts. For adolescents: weekly sessions by telephone or face-to-face as preferred with support team. Length: 1 h Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professional |

TAU: as above. | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a computer generated sequence Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate for: No (23.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Mixed methods |

Suicide: Not stated SA (dichotomous): Clinician administered diagnostic interview DISC-IV Mood Disorders module Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

| King et al. (2015) [56] USA |

Inclusion: Presented to ED with SI, a recent SA or positive screens for both depression plus alcohol/drug abuse Exclusion: Required referral for inpatient psychiatric hospitalization Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 49 Mean age: 17.7 (SD: 1.7; Range: 14–19) Gender: 40% male Treatment group N = 27 Age/gender: NR Control group N = 22 Age/gender: NR |

Individual motivational interview plus TAU Length: 35–45 min Developed by: study authors (based on standard motivational interviewing protocols) Delivered by: trained therapists |

Enhanced TAU: adolescents given a crisis card and written information about depression, suicide, firearm safety, and services. | Random sequence generation method: Shuffled envelopes Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (6.1%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): SIQ-JR Longest follow-up: 2 months post-baseline |

| McLeavey et al. (1994) [57] Republic of Ireland |

Inclusion: Presented to ED with self-poisoning Exclusion: i) Required psychiatric inpatient/day-hospital admission; ii) Psychosis; iii) Intellectual disability; iv) organic cognitive impairment Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 39 Mean age: 24.4 (SD: 7.0; Range 15–45) Gender: 25.6% male Treatment group N = 19 Mean age: 23.6 (SD: 5.9) Gender: 21% male Control group N = 20 Mean age: 25.3 (SD: 8.1) Gender: 30% male |

Individual Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills Training Length: Five weekly one-hour sessions for 5 weeks (with 1 additional session if necessary) Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

Active placebo: brief problem-oriented approach, did not involve skills training. | Random sequence generation method: NR Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: GP questionnaire and hospital records Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (15.4%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Not described |

SH (dichotomous): ED readmission Suicide: Hospital records Longest follow-up: 12 months post-intervention |

| Mehlum et al. (2016) [58]o Norway |

Inclusion: Referred to child & adolescent psychiatric outpatient clinic with a history of > 2 episodes of self-harm; 1 within the past 16 weeks Exclusion: i) Bipolar disorder (except bipolar II); ii) Schizophrenia; iii) Affective disorder; iv) Psychosis NOS; v) Intellectual disability; vi) Asperger's syndrome Recruited from: MH outpatient & Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 77 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.6; Range: 12–18) Gender: 11.7% male Treatment group N = 39 Mean age: 15.9 (SD: 1.4) Gender: 12.8% male Control group N = 38 Mean age: 15.3 (SD: 1.6) Gender: 20.5% male |

Individual and group Dialectical Behavior Therapy Length: 19 weeks – One 1-hour weekly session of individual therapy; one 2-hour weekly session of multifamily skills training; plus family therapy & telephone coaching as needed. Developed by: Miller et al. (2007) Delivered by: MH professionals |

Enhanced TAU: standard care enhanced for the purpose of the trial by requiring that therapists agree to provide at least 1 weekly treatment session per patient. | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a computer generated sequence Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview supplemented with hospital records Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (2.6% by the one-year follow-up period) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): SIQ-JR SH (continuous): ED readmission and self-report SH (dichotomous): ED readmission and self-report Suicide: Mortality records Longest follow-up: 12 months post-intervention |

| Ougrin et al. (2011) [69]; (2013) [39] UK |

Inclusion: Referred to ED following SH Exclusion: i) Psychosis; ii) Intoxication; iii) Learning disability; iv) Required inpatient admission Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 70 Mean age: 15.5 (SD: 1.3; Range: 12–18) Gender: 20% male Treatment group N = 35 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.5) Gender: 20% male Control group N = 35 Mean age: 15.5 (SD: 1.2) Gender: 20% male |

Brief contact intervention Comprised psychosocial history & risk assessment plus brief intervention Length: 1 h plus 30 min Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: standard psychosocial history and risk assessment, report sent to relevant community team | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a computer generated sequence Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview supplemented with clinical records Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (1.4% by the two-year follow-up period) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SH (dichotomous): ED readmission Longest follow-up: 24 months post-baseline |

| Pineda & Dadds, (2013) [59] Australia |

Inclusion: Presented to ED with either SI, SA or SH within the 2 months prior to presentation Exclusion: 1) Overdose of recreational drugs; ii) Intellectual disability Recruited from: ED |

Whole sample N = 48 Mean age: 15.1 (SD: 1.2; Range: 12–17) Gender: 25% male Treatment group N = 24 Mean age: 15.0 (SD: 1.31) Gender: 27.3% male Control group N = 24 Mean age: 15.28 (SD: 1.18) Gender: 22.2% male |

Strengths-based family education program plus TAU: Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program (RAP-P) Length: Four 2-hour sessions delivered in a single family format either once a week or once every two weeks. A total of five, 2-hour sessions were provided over up to 2.5 months. Developed by: based on Shochet et al. (1997)p and adapted by study authors Delivered by: primary author |

TAU: routine care (included any intervention deemed necessary by the treating team other than RAP-P). | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (16.7%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): ASQ-R Longest follow-up: 6 months post-baseline |

| Power et al. (2003) [60] Australia |

Inclusion: Referred to a specialist first episode psychosis clinic with SI or SA Exclusion: NR Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 56 Age/gender: NR Treatment group N = 31 Age/gender: NR Control group N = 25 Age/gender: NR |

Individual cognitive oriented therapy (Lifespan) plus TAU Length: Eight to ten sessions over 10 weeks. Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: standard clinical care. | Random sequence generation method: NR Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Clinical records Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (37.5%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: NR |

Suicide: Not stated Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Robinson et al. (2012) [70] Australia |

Inclusion: Referred but not accepted to a specialist outpatient adolescent MH service with a history of SI, SA or SH Exclusion: i) Intellectual disability; ii) Known organic cause for presentation Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 164 Mean age: 18.6 (SD: NR; Range: 15–24) Gender: 35.4% male Treatment group N = 81 Mean age: NR Gender: 39.5% male Control group N = 83 Mean age: NR Gender: 31.3% male |

Brief contact intervention plus TAU – monthly postcards Length: Twelve postcards over 12 months Developed by: study authors (based on existing BIC methods) Delivered by: NA |

TAU: treatment or support already being received; e.g., from school counselor, GP, psychologist. | Random sequence generation method: Block randomization using a computer generated sequence Allocation concealment method: Independent researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (52.7%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No. However, sensitivity analyses were undertaken which suggested that ITT results with data imputed for all missing observations not materially different to per protocol analysis |

SI (continuous): BSSI SI (dichotomous): BSSI SH (dichotomous): Suicide Behavior Questionnaire-14 item version (SBQ-14) SA (dichotomous): SBQ-14 Longest follow-up: 6 months post-intervention |

| Rossouw & Fonagy, (2012) [61] UK |

Inclusion: Presented to ED or referred to community MH services with SH Exclusion: i) Presentation the result of excessive use of recreational drugs; ii) Psychosis; iii) Severe learning disability; iv) Developmental disorder; v) Eating disorder; vi) Dependence on alcohol/drugs Recruited from: Hospital/ED and MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 80 Mean age: 14.7 (SD: 1.25; Range: 12–17) Gender: 15% male Treatment group N = 40 Mean age: 15.4 (SD: 1.3) Gender: 17.5% male Control group N = 40 Mean age: 14.8 (SD: 1.2) Gender: 12.5% male |

Mentalization therapy: comprised weekly individual sessions plus monthly family therapy. Length: 1 year Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals. |

TAU: routine care provided by community-based adolescent mental health services. Mainly individual therapeutic intervention, combined individual and family therapy, or psychiatric review. | Random sequence generation method: Minimization algorithm Allocation concealment method: Independent, offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (11.2%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

Suicide: Not stated SH (continuous): Risk-Taking and Self-Harm Inventory (RTSHI) SH (dichotomous): RTSHI Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Rudd et al. (1996) [40]q USA |

Inclusion: Referred to outpatient mental health clinics, an inpatient service or an ED with SA, SI Exclusion: i) Substance abuse/dependence ii) Psychosis/thought disorder; iii) Personality disorder Recruited from: Hospital/ED and MH outpatient NB: Setting comprised 1y medical center |

Whole sample N = 264 Mean age: 22.2 (SD: 2.3; Range: NR) Gender: 82.2% male Treatment group N = 143 Mean age: NR Gender: 77.6% male Control group N = 121 Mean age: NR Gender: 87.6% male |

Group-based problem-solving and social competence training Length: 9 h a day for two weeks Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: combination of inpatient and outpatient care. | Random sequence generation method: Sequential randomization Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (73.1% by the 12 month follow-up period) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Unclear |

SI (continuous): Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI)r Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

| Slee et al. (2008) [62]s The Netherlands |

Inclusion: Presented to an outpatient MH service with recent SH Exclusion: Psychiatric disorder requiring inpatient treatment Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 82 Mean age: 24.6 (SD: 5.4; Range: 15–35) Gender: 6.1% male Treatment group N = 40 Mean age: 23.9 (SD: 6.4) Gender: 2.5% male Control group N = 42 Mean age: 25.4 (SD: 4.5) Gender: 9.5% male |

12 out-patient, individual cognitive behavioral therapy sessions plus TAU Length: weekly sessions for up to 5.5 months Developed by: NR (but based on standard CBT protocol) Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: participants' choice, three forms: psychotropic medication, psychotherapy and psychiatric hospitalizations | Random sequence generation method: Computer generated random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent, offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR. Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (21.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Mixed methods |

SH (continuous): Structured clinical interview SH (dichotomous): Structured clinical interview Longest follow-up: 9 months post-baseline |

| Spirito et al. (2002) [71] USA |

Inclusion: Presented to an ED/pediatric hospital with SA Exclusion: NR Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 63 Mean age: 15.0 (1.4; Range: 12–18) Gender: 9.5% male Treatment group N = 29 Mean age: NR Gender: 13.8% male Control group N = 34 Mean age: NR Gender: 5.9% male |

Brief contact intervention Individual compliance enhancement intervention plus TAU Length: one hour Developed by: study authors Delivered by: post-doctoral psychology fellows |

TAU: standard disposition planning. | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (17.1%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SH (dichotomous): Structured interview Suicide: Not stated Longest follow-up: 3 months post-baseline |

| Spirito et al. (2015) [72] USA |

Inclusion: Resided in a specific catchment plus current or past ‘suicidality’ Exclusion: NR Recruited from: MH outpatient and Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 24 Mean age: 14.3 (SD: 1.7; Range: 11–17) Gender: 16.7% male Treatment group N = 16 Mean age: 14.7 (SD: 1.8) Gender: 12.5% male Control group N = 8 Mean age: 14.0 (SD: 1.7) Gender: 25% male |

Parent-Adolescent-cognitive behavioral therapy Individual CBT (for the parents plus adolescents) and family sessions Length: 12 sessions over 12 weeks Developed by: based on protocols used in prior clinical trials with depressed Adolescents. Delivered by: masters and PhD level clinicians |

Active placebo: adolescent-only CBT. | Random sequence generation method: NR Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of DSH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: NR Less than 15% drop-out rate: Unclear Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SI (continuous): BSSI-A Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline Not included in MA2 |

| Wharff et al. (2017) [63] USA |

Inclusion: i) presentation to ED with “suicidality” or suicide attempt; ii) presence of consenting parent or legal guardian Exclusion: i) not fluent in English; ii) Not medically stable, including intoxication; iii) cognitive ‘limitations’ preventing completion of research instruments; iv) active psychosis; v) required physical or medical restraint in ED Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

Whole sample N = 142 Mean age: 15.5 (SD: 1.4) Gender: 28% male Treatment group N = 68 Mean age: 15.4 (SD: 1.3) Gender: 26% male Control group N = 71 Mean age: 15.6 (SD: 1.5) Gender: 30% male |

Family Based Crisis Intervention (based on cognitive behavioral therapy) plus TAU; an emergency crisis intervention Length: 60 to 90-min Developed by: study authors Delivered by: master's level psychiatric social workers |

TAU: standard psychiatric Evaluation and clinical/discharge recommendations. |

Random sequence generation method: NR Allocation concealment method: NR Ascertainment of DSH repetition: NA Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (19.0%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: No |

SI (continuous): Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (RFL-A)t Longest follow-up: 1 month post-intervention |

| Wood et al. (2001) [64] UK |

Inclusion: i) Referred to child & adolescent MH service following SH; ii) Engaged in SH on at least one other occasion during the past year Exclusion: i) ‘Too suicidal’ for ambulatory care; ii) psychosis; iii) learning ‘problems’ Recruited from: MH outpatient |

Whole sample N = 63 Mean age: 14.3 (SD: 1.6; Range: 12–16) Gender: 22.2% male Treatment group N = 32 Mean age: 14.2 (SD: 1.1) Gender: 21.9% male Control group N = 31 Mean age: 14.3 (SD: 2.1) Gender: 25.8% male |

Combined group-based psychotherapy plus TAU. Comprised aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy. Length: “until the young person feels ready to leave” (p. 1247). Developed by: study authors Delivered by: MH professionals |

TAU: variety of interventions delivered by community psychiatric nurses & psychologists. Included family sessions, nonspecific counseling. Psychotropic medication (where indicated). | Random sequence generation method: Random numbers table Allocation concealment method: Independent, offsite researcher Ascertainment of SH repetition: Interview Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (3.1%) Was ITT analysis undertaken: Yes |

SH (continuous): ED readmission (assessed via interview) SH (dichotomous): ED readmission Suicide: Not stated Longest follow-up: 7 months post-randomization |

Notes: ED = Emergency Department; ITT = intention-to-treat; IQR = Interquartile Range; MA = meta-analysis; MH = mental health; NR = not reported; TAU = treatment as usual; SA = suicide attempt; SD = standard deviation; SH = self-harm; SI = suicidal ideation; SRB = suicide-related behavior.

Stanley B, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicide prevention (CBTSP): treatment model, feasibility and acceptability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009; 48 [10]:1005–13.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, et al. Enhancing treatment adherence with aspecialized emergency room program for adolescent suicide attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996; 35:654–663.

Linehan MM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48:1060–1064.

Linehan MM. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press, 1993.

Miller, AL, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal adolescents. New York: Guilford Press, 2007.

Morgan HG et al. Secondary prevention of non-fatal deliberate self-harm. The green card study. BJP 1993; 163: 111–112.

Excluded secondary publications: Diamond G, et al. Sexual trauma history does not moderate treatment outcome in Attachment-Based Family Therapy (ABFT) for adolescents with suicide ideation. J Fam Psychol 2012; 26(4): 595-605; Shpigel MS, et al. Changes in parenting behaviors, attachment, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in attachment-based family therapy for depressive and suicidal adolescents. J Marital Fam Ther 2012; 38(Suppl 1): 271-83.

Reynolds WM. Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources Inc., 1987.

Classified as CBT in the meta-analysis.

Excluded secondary publication: Harrington R, et al. Deliberate self-poisoning in adolescence: why does a brief family intervention work in some cases and not others? J Adolesc 2000; 23(1): 13–20.

Carter GL, et al. Postcards from the EDge project: randomised controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self poisoning. BMJ 2005; 331: 805–7.

Henggeler S, et al. Serious Emotional Disturbance in Children and Adolescents: Multisystemic Therapy. New York: Guilford Press, 2002.

Schmidt U, Davidson KM. Life After Self-Harm: A Guide to the Future. Routledge, 2004.

Hodges K. Child and Adolescent Functional Assessment Scale. Ypsilanti: Eastern Michigan University, 1989.

Excluded secondary publication: Mehlum L, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014; 53(10): 1082–91.

Shochet I, et al. Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program: group leader's manual. Brisbane, Australia: Griffith University, 1997.

Excluded secondary publication: Wingate LR, et al. (Comparison of compensation and capitalization models when treating suicidality in young adults. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2005. 73(4): 756–62.

Miller I, et al. (1986). The modified scale for suicidal ideation: Reliability and validity. J Consult Clin Psychol, 54, 724–725.

Excluded secondary publications: Slee N, et al. Emotion regulation as mediator of treatment outcome in therapy for deliberate self-harm. Clin Psychol Psychother 2008; 15(4): 205–16.; Spinhoven P, et al. Childhood sexual abuse differentially predicts outcome of cognitive-behavioral therapy for deliberate self-harm. J Nerv Ment Dis 2009; 197(6): 455–7.

Osman A, et al. The Reasons for Living Inventory for Adolescents (RFL-A): development and psychometric properties. J Clin Psychol 1998; 54: 1063–1078.

Table 2.

Study characteristics: Non-randomized controlled trials conducted in clinical settings (N = 19).

| Study; country | Study design; level of evidence | Target population | Participants | Intervention description | Comparison condition | Risk of bias | Suicide related outcome(s) assessed; Longest follow-up | Results | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asarnow et al. (2015) [73] USA |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: SA in past 3 months; stable living situation Exclusion: No contact information available for follow-up; psychosis; substance abuse/dependence; not English-speaking; no family to participate Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

N = 35 Mean age: 14.89 (SD: 1.6; Range: 11–18) Gender: 14% male |

Suicide-specific family-based cognitive behavioral therapy comprising psycho-education plus individual therapy. The Safe Alternatives for Teens & Youths program (SAFETY Program) Length: Up to 20 sessions over 12 weeks, incl: 1 × family session then individual (16 x youth-only & parent-only), then up to 16 × family sessions Developed by: Henggeler (2002) Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: NR Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (11.4%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: Harkavy-Asnis Suicide Survey, passive suicidal ideation subscale. SA: Harkavy-Asnis Suicide Survey, suicide attempt subscale. SRB: Harkavy-Asnis Suicide Survey, active suicidal behavior and ideation subscale. Longest follow-up: 6 months post-intervention |

SI: Pre-test Mean (SD): 12.69 (9.79) Post-test Mean (SD): 9.19 (10.14) SA: Pre-test Mean (SD): 0.89 (1.86) Post-test Mean (SD): 0.13 (0.34) SRB: Pre-test Mean (SD): 3.71 (4.42) Post-test Mean (SD): 1.81 (2.69) |

There was evidence of a significant reduction in SI (t-test = 2.56, p = 0.016, Cohen's d = 0.39), SA (t-test = 2.42, p = 0.019), and SRB (t-test = 2.63, p = 0.013) between baseline and three-month follow-up. Four young people either re-attempted suicide and/or re-engaged in NSSI during the treatment period (significance test not reported). |

| Brent et al. (2009) [91] USA |

Study design: Non-randomized, experimental trial Level of evidence: III-2 |

Inclusion: Had major unipolar mood disorder & SA in past 90 days; living with a parent or guardian who could participate in treatment Exclusion: Substance dependence, bipolar disorder, psychosis, or developmental disorder Recruited from: Unclear |

Whole sample N = 124 Mean age: 15.8 (SD: 1.5; Range: 12–18) Gender: 22.6% male Treatment group (1) N = 18 Age/gender: NR Treatment group (2) N = 93 Age/gender: NR Control group N = NR Age/gender: NR |

Suicide-specific individual cognitive behavioral therapy with some elements of dialectical behavior therapy. Length: between 12 and 16 weekly sessions. Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: Unclear |

Medication management or combined medication & CBT | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: Yes Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (33.1%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SA: Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment SRB: Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment. Suicide: not described. Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

SA: NR SRB: NR Suicide: NR |

There was evidence of an increase in SRB between baseline and six-month follow-up in the combination (i.e., psycho- and pharmacotherapy group) compared to either condition alone (22/93 vs. 2/31; Fisher's exact test p = < 0.04). There was one completed suicide after the six-month follow-up, however, it is unclear to which treatment group this young person had been allocated. |

| Courtney & Flament, (2015) [74] Canada |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: BPD features with SI OR SH in past 4 months Exclusion: psychosis; developmental disorder Recruited from: MH outpatient |

N = 61 Mean age: 16.5 (SD: 0.8; Range: 15–18) Gender: 7% male |

Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for adolescents in tertiary care. A-DBT-A Length: 1 x weekly group-based and 1 × weekly individual sessions over 14-weeks (session duration not stated). Developed by: Based on Miller et al. (2006) but adapted by the study authors Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: NR Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (49.2%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ). SRB: Medical/clinical records. Suicide: NR Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

SI: Pre-test Median (IQR): 131.0 (92.0 to 144.0). Post-test Median (IQR): 77.0 (48.5 to 121.0). SRB: NR Suicide: NR |

There was evidence of a significant reduction in SI (t-test = 4.96, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.89) between baseline and the 15-week post-intervention assessment. There was also evidence of a significant reduction in the proportion of young people engaging in SRB over this period (36/42 vs. 16/42, McNemar test p < 0.001). There were no reports of completed suicides. |

| Cwik et al. (2016) [82] USA |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: Apaches with SA in past 90 days Exclusion: none Recruited from: Community suicide surveillance system |

N = 13 Mean age: 14.3 (SD: 2.2) Gender: 8% male |

New Hope, a brief psycho-education intervention for American Indian adolescents Length: 1–2 visits (2–4 h total). Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: Community Mental Health Workers |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (15.4%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: SIQ Longest follow-up: 3 months Post-intervention |

SI: N (%) scoring above clinical cut-off: Pre-test: 7/11 (64%) Post-test: 1/10 (10%) |

The number of participants who scored above the clinical cut-off for the SIQ seemed to decrease over the follow-up period. |

| Diamond et al. (2013) [83]a USA |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: LGB discharged from hospital with SI (admitted for SI or SA) Exclusion: Psychosis or ID Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

N = 10 Mean age: 15.1 (SD: 1.37; Range: 14–18) Gender: 20% male |

Attachment-based family therapy adapted for use with suicidal LGB youth. ABFT-LGB Length: 12 x weekly sessions (range = 8–16). Sessions lasted for 60-min & sessions 3–5 were for parents only. Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: SIQ-Junior (SIQ-JR) Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

SI: Pre-test Mean (SD): 51.00 (13.00) Post-test Mean (SD): 6.88 (7.34) |

There was evidence of a significant reduction in SI between baseline and the 3-month post-intervention assessment (F-test = 18.78, p = 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.21). |

| Duarte-Velez et al. (2016) [75] Puerto Rico |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: Admitted to ED with SI or SA, hospitalized, stabilized and referred to outpatient; legal guardian. Exclusion: Psychosis; developmental disorder; ID; already receiving psychotherapy; involvement in a legal procedure that would require psychological care mandated by the judicial system Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

N = 11 Mean age: 15.36 (SD-NR; Range: 13–17) Gender: 45% male |

Cognitive behavioral therapy adapted for Puerto Rican adolescents with suicidal behavior. Length: Weekly individual sessions lasting for 1 h & delivered over 6 months. Plus 60–120 min family sessions & follow-up bi-weekly as necessary. Phone calls & case management as needed. Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (27.3%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: SIQ-JR Longest follow-up: Post-intervention |

SI: Pre-test Mean (SD): 27.20 (NR) Post-test Mean (SD): 16.00 (NR) |

There was evidence of a reduction in SI between baseline and the six month post-intervention assessment (significance test not reported). |

| Esposito-Smythers et al. (2006) [76] USA |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: Admitted to inpatient unit for SI/SA with co-occurring alcohol abuse/dependence Exclusion: ID, DSM-IV dependence on substances other than alcohol or cannabis. Recruited from: Hospital/ED |

N = 6 Mean age: 15 (SD: 1; Range: 14–16) Gender: 17% male |

Integrated cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with co-occurring alcohol use disorder and suicidality. Length: Acute phase: Weekly sessions lasting 1 h & delivered over 6 months (plus maintenance & booster phases). Developed by: Study authors, incorporating modifications of Monti's (2002)b coping skills training package for youth with co-occurring alcohol use disorder Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (16.7%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: No |

SI: SIQ SRB: NR Longest follow-up: 12 months post-intervention |

SI: Pre-test Mean (SD): 80.80 (NR) Post-test Mean (SD): 32.80 (NR) |

There was evidence of a reduction in SI between baseline and the 12 month post-intervention assessment (significance test not reported). Two young people re-engaged in SRB during this period (significance test not reported). |

| Geddes et al. (2013) [77] Australia |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: At least 3 BPD features & SI/SH in past 12 months Exclusion: Primary diagnosis of psychosis or substance abuse; ID Recruited from: MH Outpatient |

N = 6 Mean age: 15.1 (SD-NR; Range 14–15) Gender: 0% male |

Dialectical behavior therapy modified for adolescents: Life Surfing Length: 1–2 weekly sessions lasting for 1 h & delivered over 26 weeks. Plus a weekly 2 h family skills group delivered over an 18-week period. Developed by: Based on Swales (2000)c but adapted by the study authors. Delivered by: NR |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (16.7% by the three-month follow-up period) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SI: NR SBR: Self-Harm/Suicidal Thoughts Questionnaire: Parent and Adolescent Versions. SA: NR Longest follow-up: 12 months post-baseline |

SA: NR SRB: NR |

There was evidence of a reduction in the proportion of young people reporting SI between baseline and the 18-week post-intervention assessment (significance test not reported). By the 18-week post-intervention assessment, 5 of the 6 young people had had no further episodes of SRB, whilst the sixth reported a 50% reduction in SRB frequency (significance tests not provided). By the 12 month follow-up period, no young person had a further episode of SA (significance test not reported). |

| Gutstein & Rudd (1990) [78] USA |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: Referred to a guidance center following a near-lethal SA/persistent suicide threats (severe risk) Exclusion: NA Recruited from: Hospital/Ed, MH outpatient & community |

N = 47 Mean age: 14.4 (SD-NR; Range: 7–19) Gender: 47% male |

A suicide-specific intensive group crisis intervention: Systemic Crisis Intervention Program Length: Two × 4-hour group meetings over a 2–6 week period. Developed by: Study authors Delivered by: NR |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: Yes (0.0%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: No |

SA: Parental report Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

SA: NR | There was evidence of a reduction in the proportion of young people engaging in SA between baseline and the 18 month follow-up assessment (significance test not reported). |

| James et al. (2011) [79] UK |

Study design: Pre-test/post-test case series Level of evidence: IV |

Inclusion: Living in ‘out of home care’ & engaged in SH for > 6 months Exclusion: diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism spectrum disorder; Moderate–severe mental impairment Recruited from: MH outpatient service |

N = 25 Mean age: 15.5 SD: 1.5; Range: 13–17 Gender: 12% male |

Dialectical behavior therapy comprising a skills training group, individual therapy, telephone support, support for schools/carers & outreach. Length: 1-hour individual sessions plus 2-hour group sessions delivered weekly over 12 months. Developed by: Based on Linehan (1993) and Rathus and Miller (2002)d but adapted by the study authors. Delivered by: a MH professional |

NA | Adequately powered: No Outcome assessor blinding: NA Less than 15% drop-out rate: No (28.0%) Use of statistical testing to measure change from pre-test to post-test: Yes |

SRB: Clinical interview Longest follow-up: Post-intervention only |

SRB: NR | There was evidence of a reduction in the proportion of young people engaging in SRB between baseline and the 12 week post-intervention period (14/18 young people had ceased engaging in SRB altogether) (significance tests not provided). There was also evidence of a reduction in the frequency of these SRB episodes over this period (significance tests not provided). |