Abstract

Purpose:

Diagnosing monogenic diseases facilitates optimal care, but can involve the manual evaluation of hundreds of genetic variants per case. Computational tools like Phrank expedite this process by ranking all candidate genes by their ability to explain the patient’s phenotypes. To use these tools, busy clinicians must manually encode patient phenotypes from lengthy clinical notes. With 100 million human genomes estimated to be sequenced by 2025, a fast alternative to manual phenotype extraction from clinical notes will become necessary.

Methods:

We introduce ClinPhen, a fast, high-accuracy tool that automatically converts clinical notes into a prioritized list of patient phenotypes using Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms.

Results:

ClinPhen shows superior accuracy and 20× speedup over existing phenotype extractors, and its novel phenotype prioritization scheme improves the performance of gene-ranking tools.

Conclusion:

While a dedicated clinician can process 200 patient records in a 40-hour workweek, ClinPhen does the same in 10 minutes. Compared with manual phenotype extraction, ClinPhen saves an additional 3–5 hours per Mendelian disease diagnosis. Providers can now add ClinPhen’s output to each summary note attached to a filled testing laboratory request form. ClinPhen makes a substantial contribution to improvements in efficiency critically needed to meet the surging demand for clinical diagnostic sequencing.

Keywords: medical genetics, Mendelian disease diagnosis, natural language processing, prioritized disease phenotypes

INTRODUCTION

Every year, 7 million children worldwide are born with severe genetic diseases.1 Diagnosing these conditions involves determining which of numerous genetic variants is causing the patient’s symptoms. Proband-only exome sequencing typically results in 100–300 rare coding variants of unknown significance.2 A clinician spends an average of 54 minutes evaluating each variant3 until the causative one is identified (Fig. 1). As sequencing technology improves, the number of clinical applications skyrockets, with 100 million human genomes expected to be sequenced by 2025 (ref. 4). With this surging demand, manual variant curation by a limited pool of experienced clinicians and curators creates a bottleneck in the diagnostic process.

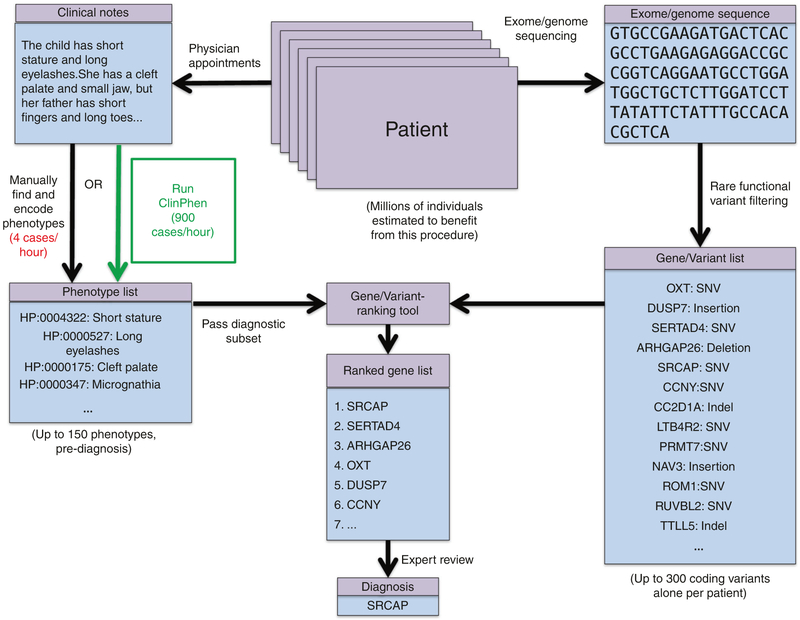

Fig. 1. Steps to diagnose a patient with a Mendelian disease using automated gene-ranking algorithms.

The patient’s genotypic information is encoded using standard formats (variant call format [VCF] file, candidate causative gene list) and a list of patient phenotypes encoded as ontology terms. Extensive tool support exists for obtaining candidate causative variants and genes from an exome sequence. Tool support for obtaining an appropriate list of encoded patient phenotypes from the patient’s clinical notes is limited. Encoded phenotypes are currently acquired by manually reading through the patient’s clinical notes and recording the phenotypes found as their IDs in a phenotype ontology. We introduce ClinPhen, a tool that automates phenotype extraction from clinical notes, optimized to accelerate patient diagnosis. SNV single-nucleotide variant.

Although clinicians must make the final diagnosis, the process leading up to it can be greatly expedited by computational tools. Tools such as ANNOVAR,5 M-CAP,2 VEP,6 and SnpEFF7 can filter out likely benign variants, and narrow down the candidate gene list. Phrank,8 hiPhive,9 Phive,10 PhenIX,11 and other automatic gene-ranking tools12–19 improve the efficiency of evaluating the candidate genes. These algorithms require a list of patient phenotypes from a phenotype ontology (notably, the Human Phenotype Ontology, or HPO20). They use these phenotypes to rank a provided list of candidate genes in order of estimated likelihood of causing the patient’s phenotype. Consequently, clinicians may reach a diagnosis faster by going down the computer’s ranked list.

However, comparable tools for automatically encoding phenotypes mentioned in the patient’s clinical notes are lacking. While gene-ranking tools can considerably shorten the lengthy manual review of a gene list,3 their ability to do so depends on the careful input of coded phenotypes (see below). Manual encoding of phenotypes is a slow and unstructured process, making gene-ranking tools difficult for clinicians to adopt.

Existing natural language processing tools that identify patient phenotypes were not designed to expedite Mendelian disease diagnosis.21–27 Many such tools only look for indications of specific phenotypes or diseases.26,28,29 Others report all of the phenotypes they can find—including negated phenotypes (“The patient does not have symptom X”), unrelated findings in family members (“The patient’s mother has symptom X”), and phenotypes mentioned while discussing a differential diagnosis (“Patients with disease W often have symptom X”).23,27 Two general purpose phenotype extractors, cTAKES25 and MetaMap,21 do aim to extract only the phenotypes that apply to the patient, but they are not optimized for a high-volume workflow. They have relatively slow runtimes and suboptimal accuracy. Importantly, they do not indicate which phenotypes may be more useful in establishing a diagnosis. A patient’s clinical notes can mention over 100 phenotypes, but for disease diagnosis, clinicians typically list only the ones they think will help diagnosis the most.30

Here, we introduce ClinPhen: a fast, easy-to-use, high-precision, and high-sensitivity alternative to existing phenotype extractors. ClinPhen scans through a patient’s clinical notes in seconds, and returns phenotypes that help generanking tools rank the causative gene higher than they would with manually identified phenotypes. Using several cohorts of diagnosed patients, we show how to expedite the diagnosis of Mendelian diseases by letting gene-ranking tools run directly on phenotypes extracted from the clinical notes by ClinPhen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of ClinPhen

ClinPhen extracts phenotypes from free-text notes and translates them into terms from the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), a structured database containing 13,182 human disease phenotypes (Fig. 2, Supplementary Methods).

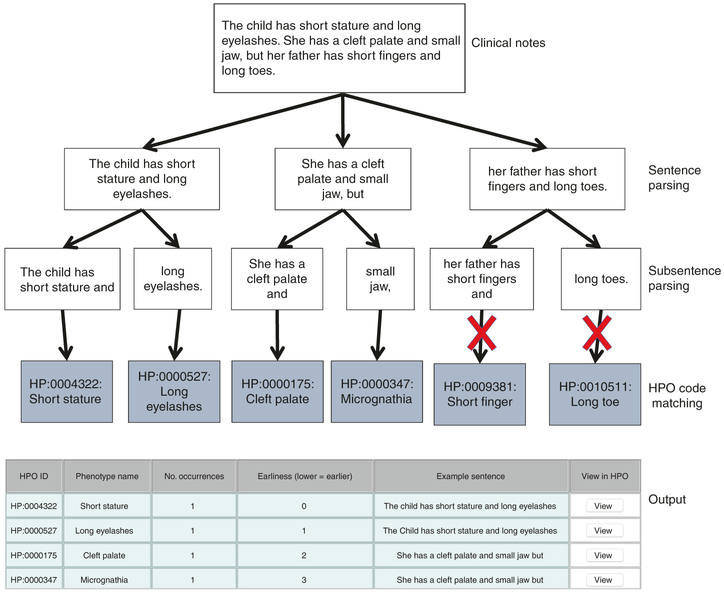

Fig. 2. ClinPhen sentence analysis process.

ClinPhen splits the clinical notes into sentences, and those sentences into subsentences. It then finds phenotypes whose synonyms appear in the subsentences. A high-precision, high-sensitivity, rule-based natural language processing system decides which phenotypes correspond to true mentions and which are false positives. Because the third sentence contains the flag word “father,” for instance, it is assumed that this sentence does not refer to the patient, and any phenotype synonyms found in the sentence will not be associated with the patient. ClinPhen sorts the identified phenotypes first by how many times they appeared in the set of notes (descending), then by the index of the first subsentence in which they were found (ascending), and then by Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) ID (ascending).

To extract HPO terms from the clinical notes, ClinPhen first breaks the free text into sentences, subsentences, and words. ClinPhen normalizes inflected words using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) Lemmatizer.31

Subsequently, ClinPhen matches subsentences against phenotype names and synonyms (Supplementary Methods). Rather than looking for continuous phrases, ClinPhen checks if the subsentence contains all words in the given synonym. For example, “Hands are large” will match the HPO phenotype “Large hands.” For efficiency, ClinPhen passes the clinical documents into a hash table that maps words to the subsentences that contain them.

After identifying phenotypes, ClinPhen decides if each mentioned phenotype applies to the patient. If, for instance, a sentence contains words such as “not” or “cousin,” ClinPhen does not associate with the patient any phenotypes mentioned in the sentence (Fig. 2). ClinPhen also ignores phenotypes that are commonly found in the patient population (Supplementary Methods).

For each HPO phenotype, ClinPhen counts the number of occurrences in the clinical notes, and saves where in the notes it first appears. ClinPhen returns a sorted list of all HPO phenotypes found, with the most- and earliest-mentioned phenotypes at the top (Fig. 2).

Training ClinPhen to recognize phenotypes in free-text notes

Real patient cases used to improve and test ClinPhen

ClinPhen was trained and tested on six sets of real patient data from four different medical centers. The training set (clinical notes of 25 patients with undiagnosed but presumed genetic diseases from Stanford Children’s Health [SCH]) was used to improve the accuracy of ClinPhen; the STARR set (5000 random patients from Stanford’s STARR database32) was used to train ClinPhen’s phenotype-frequency filter (Supplementary Methods); the Stanford test set (clinical notes, genetic data, and diagnoses of 24 diagnosed patients from SCH) was used to test the accuracy and runtime of ClinPhen, as well as the performance of gene-ranking tools when using ClinPhen’s phenotypes; and the Manton test set (21 diagnosed patients from the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, at Boston Children’s Hospital) was used to independently verify the findings from the Stanford test set. The Duke and University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) test sets (14 and 15 diagnosed individuals, respectively), from the respective Undiagnosed Diseases Network (UDN) sites, were used to test the performance of gene-ranking tools when using ClinPhen’s phenotypes in realistic “off-label” settings: notes from the Duke site were taken from PDFs rather than text files, and converted to text without any manual correction (to preserve full automation) using an optical character recognition (OCR) program;33 while the UCLA test set included only one clinical note per patient (other sets had 4–5 notes per patient, on average). In all cases, only notes created by clinical genetics and pediatrics providers before documentation of the patient’s diagnosis were used. Patient characteristics were similar across the four test sets, with average age at last note of 7, 9, 13, and 15. All but one disease diagnosis were unique per center, and only seven diseases were repeated across the different centers. Clinical and genetic data were obtained under research protocols approved by the Stanford institutional review board (IRB), Harvard IRB, and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) central IRB for the UDN. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Testing the accuracy of ClinPhen’s extracted phenotypes

To test the accuracy of the extracted phenotypes, we produced for each patient in the Stanford test set a gold standard set of phenotypes called the All set: a nonphysician and a licensed physician blinded to ClinPhen’s development independently extracted phenotypes from the clinical notes. The physician recorded only the phenotypes that he considered useful for diagnosis (i.e., more likely to pertain to a genetic disease, such as skeletal abnormalities, as opposed to allergies) to generate the Clinician phenotype set. The nonphysician recorded all of the phenotypes he found, regardless of predicted usefulness. The physician then verified the nonphysician’s identified phenotypes to be correctly interpreted and applicable to the patient. These verified phenotypes, plus those in the Clinician set, made up the All phenotype set. We ran each automatic phenotype extractor on the patient’s clinical notes, and measured the extractor’s precision and sensitivity by comparing the extracted phenotypes with the All set.

We compared the All set with the phenotypes returned by ClinPhen, across the Stanford test set. Due to the nature of HPO, the presence of a phenotype in a patient implies the presence of all ancestor phenotypes. For instance, the term “Seizures” is an ancestor node of the term “Grand mal seizures”: a patient presenting with grand mal seizures must also present with seizures. The “closure” of a set of HPO terms S consists of S plus all ancestors of the terms in S up to “Phenotypic abnormality” (HP:0000118). We compared the extracted phenotypes with the true phenotypes using the closures of the two sets.

For each patient in the Stanford test set, we found the closure of the All set and that of the phenotype set returned by ClinPhen. True positives (TP) were defined as the nodes present in both the All and ClinPhen closures. False positives (FP) were defined as the nodes only present in the ClinPhen closure. False negatives (FN) were defined as the nodes only present in the All closure. Standard definitions of precision (TP/TP + FP) and sensitivity (TP/TP + FN) were used.

We used bootstrapping to calculate a 95% confidence interval around the average precision. For each of 1000 trials, we randomly selected (with replacement) a cohort of patients equal to the size of the original cohort, and determined the average phenotype extraction precision across the random cohort. We then sorted the 1000 precision values. The confidence interval was defined to be between the 2.5th and the 97.5th percentiles. The confidence interval around the average sensitivity was calculated similarly.

Because the phenotype extractors cTAKES and MetaMap output Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) terms, while all gene-ranking tools require HPO terms, we converted UMLS terms to HPO using the UMLS Metathesaurus.34

Measuring phenotype extraction times of clinicians and automatic phenotype extractors

For each patient in the Stanford test set, 3 licensed clinicians (blinded to ClinPhen development) timed themselves reading through the clinical notes, manually extracting the phenotypes that they considered useful for diagnosis and finding their matching HPO terms. These times served as reference points for how long a clinician would take to manually extract phenotypes from clinical notes. We also timed each of the automatic phenotype extractors when running them on the same clinical notes. The phenotypes extracted by one clinician across all patients comprised a Clinician set.

To determine runtimes of automatic phenotype extractors, we ran all three extractors on a 2017 15-inch MacBook Pro with macOS High Sierra version 10.13.5 operating system and a 2.9-GHz intel core i7 processor, with 16 GB (2133 MHz) of memory.

Verification of ClinPhen results on patients from different clinical centers

To verify our findings on a patient test set from a different clinical center, we additionally performed the above tests— precision and sensitivity testing, determining the optimal number of phenotypes for gene ranking, comparing extraction times with other gene-ranking algorithms and clinicians, and comparing automatic gene-ranking algorithm performance using automatically and clinician-extracted pheno-types—on a set of patients from the Manton Center at Boston Children’s Hospital. We also tested the gene-ranking performance of Phrank using ClinPhen, cTAKES, or MetaMap on patients from the UDN sites at Duke and UCLA.

RESULTS

ClinPhen extracts the most accurate phenotype sets

We compared the accuracy of three tools that automatically extract patient phenotypes from clinical notes: ClinPhen, cTAKES, and MetaMap. We tested for precision and sensitivity by comparing each extractor’s returned phenotypes to the clinician-approved All phenotype set (defined above).

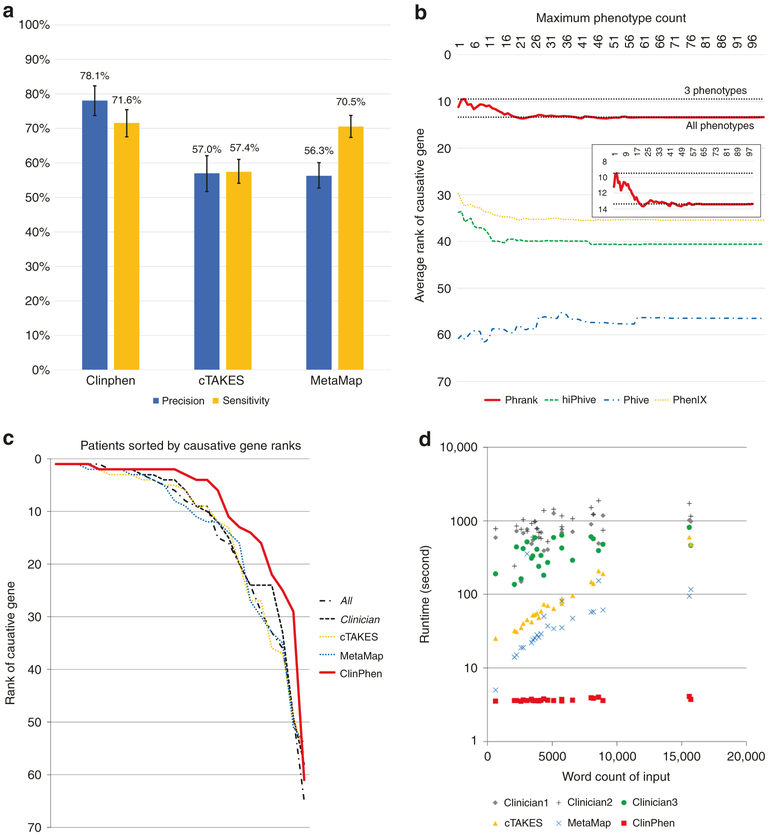

Across the Stanford test patients, cTAKES had an average precision of 57%, and MetaMap 56%. ClinPhen had a superior average precision of 78%. cTAKES had an average phenotype sensitivity of 57%, and MetaMap 71%. ClinPhen had a superior average phenotype sensitivity of 71.6% (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3. Performance of all extraction methods.

(a) Comparison of the extractors’ precision and phenotype sensitivity (higher bars mean higher accuracy). We compared the average precision and sensitivity values of ClinPhen, cTAKES, and MetaMap, using patients from the Stanford test set as subjects, and the All set (all of the phenotypes found manually and confirmed by a physician to apply to the patient) as the correct phenotypes. The average (column) and 95% confidence interval (calculated using bootstrapping with 1000 trials) of the precision and sensitivity values across all patients are displayed for each extractor. ClinPhen achieves the highest average precision and sensitivity. (b) Causative gene-ranking performance of each gene-ranking tool when run with different numbers of phenotypes returned by ClinPhen (lower number means better causative gene rankings). ClinPhen was run on the clinical notes of the Stanford test set, and the gene-ranking tools were called with the patient’s genetic information and the n highest-priority (most-mentioned, first-occurring) extracted phenotypes, with n running from 1 to 100 inclusive. The average causative gene rank across all patients was taken for each phenotype count limit (n)/gene-ranking tool pairing. The better-performing gene-ranking algorithms rank the causative gene higher when run with a few (around 3) high-priority phenotypes than with all extracted phenotypes. (c) Phrank’s causative gene-ranking performance across all extraction methods (lower numbers mean better causative gene rankings). We compared the causative gene ranks obtained by running Phrank on the Stanford test set with various extracted sets of phenotypes (All manually found, physician-verified phenotypes [All] versus a subset of phenotypes considered by a physician to be useful for diagnosis [Clinician] versus automatically extracted phenotypes using various methods). Phrank ranks are sorted lowest to highest for each extractor. Phrank performs better when run with ClinPhen’s 3 highest-priority phenotypes (the most-mentioned, earliest-occurring phenotypes in a patient’s clinical notes) than when run with other phenotype sets, manually or automatically extracted. (d) Extractor runtime comparison on each patient (lower number means faster runtime). We measured the runtime of each extractor (ClinPhen, cTAKES, and MetaMap) on each patient’s clinical notes, in seconds. For each patient, we also measured the time three clinicians took to manually scan through the same notes read by the automatic extractors, and encode the phenotypes considered useful for diagnosis. Each data point is one patient whose clinical notes were scanned by one of the extractors (or clinicians). The horizontal position is the total number of words in the patient’s clinical notes. The vertical position is the time taken for the extractor to run on the notes (logarithmically scaled). While MetaMap’s runtime scales linearly and cTAKES’ runtime scales exponentially with the total length of the clinical notes, ClinPhen runs in near-constant time, and is 15–20× faster than the next fastest tool. All automatic extraction tools are much faster than manual extraction.

Automatic extraction of phenotypes accelerates Mendelian disease diagnosis

Limiting the number of extracted phenotypes leads to better results with automatic gene-ranking methods

A patient undergoing genome sequencing can present hundreds of candidate genes containing potentially deleterious variants,2 and each gene can take an hour to evaluate.3 Gene-ranking tools expedite the process of finding the causative gene by sorting the genes based on how well their associated phenotypes match the patient’s presentation. The closer the causative gene is to rank 1, the sooner clinicians will find it. The rankings depend on a provided list of patient phenotypes, meaning that the ideal phenotype set for diagnosis is the one that helps gene-ranking tools rank the causative gene close to the top. We show that this goal is better accomplished not by the full set of patient phenotypes, but by a subset thereof.

For genetic disease diagnosis, a good phenotype set accurately reflects the patient’s presentation, but an optimal phenotype set reflects only the phenotypes that likely pertain to a genetic disease. Phenotypes caused by a common cold can mislead gene-ranking tools, and make the causative gene harder to identify. ClinPhen, as far as we are aware, is the first phenotype extractor to account for this caveat.

After identifying all phenotypes, ClinPhen removes the phenotypes that occur frequently in a large unselected patient population (Supplementary Methods), and prioritizes remaining phenotypes by number of occurrences in the notes (phenotypes that likely pertain to a genetic disease are usually mentioned multiple times, and in multiple notes), then by earliest occurrence in the notes (expert clinicians often begin a note with a summary of the phenotypes that seem striking and indicative of a genetic disease).

To determine the ideal number of top-priority phenotypes to give to gene-ranking tools, we ran ClinPhen on the Stanford test patients’ clinical notes, and filtered the extracted phenotypes down to the n highest-prioritized phenotypes, for every number n from 1 to 100 inclusive. Each set of n highest-priority phenotypes was used as input to four automatic generanking algorithms: Phrank,8 hiPhive,9 Phive,10 and Phenix.11 For each phenotype count(n)/gene-ranking tool pairing, we found the average causative gene rank across the test patients (Fig. 3b).

The higher-performing gene-ranking tools (Phrank, hiPhive, and PhenIX) ranked the causative genes higher at phenotype maxima below 10 (n < 10). Phrank, the highest-performing of these, yielded the best causative gene rankings at a phenotype maximum of 3. It was thus approximated that the three highest-priority phenotypes returned by ClinPhen generally lead to the best causative gene rankings.

Across the Stanford test patients (with an average of 291 candidate genes per patient), Phrank ranked the causative gene at an average rank of 13.4 with unfiltered ClinPhen phenotypes, and 9.5 with ClinPhen’s three top-priority phenotypes (lower number means better ranking).

As an alternative to prioritizing phenotypes using the above scheme, we tried prioritizing phenotypes by their information content, a metric that estimates how indicative a phenotype is of a genetic disease based on the number of genes known to cause the phenotype (higher-information content phenotypes are prioritized higher8). However, this prioritization scheme was found to result in inferior gene-ranking performance (Supplementary Figure 2a).

Gene-ranking tools perform better when using automatically extracted phenotypes compared with human-extracted phenotypes

To show that ClinPhen saves time in the overall diagnostic process, we set out to show that Phrank does not rank causative genes higher when using manually extracted phenotypes.

We compared two manual extraction techniques: manually subsetting all mentioned phenotypes to those that a clinician thinks are most likely to help with the diagnosis30 (represented by the Clinician phenotype set), and listing all mentioned patient phenotypes, whether or not they are likely to help with the diagnosis (represented by the All phenotype set). The Clinician and All phenotype sets were generated for each test patient.

The Stanford test patients were each run through the automatic gene-ranking tool Phrank using each of five phenotype sets: the All set, the Clinician set, the three top-prioritized phenotypes returned by ClinPhen, the phenotypes returned by cTAKES, and the phenotypes returned by MetaMap (Fig. 3c). Running Phrank with the All set yields an average causative gene rank of 14.3, using the Clinician set yields 12.9, and using ClinPhen’s three top-prioritized phenotypes yields 9.5 (lower number means better ranking). Assuming a clinician examines a ranked gene list from top to bottom, spending an average of one hour evaluating the variants in each gene for their potential to have caused the patient’s phenotypes,3 using the three top-prioritized ClinPhen phenotypes (instead of manually extracted phenotypes) as input to an automatic generanking tool can save 3–4 hours per case in the diagnostic process.

ClinPhen is much faster than previous tools or clinicians′ manual work

A good phenotype extractor runs in a short amount of time. More clinical notes take longer to read through, and some patients have far more clinical notes than others do. Therefore, automatic extractors that quickly extract HPO phenotypes from long collections of clinical notes are ideal.

The Stanford test patients had an average of four free-text, prediagnosis clinical notes per patient. Three clinicians timed themselves manually extracting phenotypes from each patient’s notes. On average, manual phenotype extraction took the clinicians 701 seconds per patient. Running cTAKES took an average of 114 seconds, and MetaMap 58.5 seconds.

The time taken to extract a patient’s phenotypes scaled with the amount of text to read through: for the longest collections of notes, it took over 1000 seconds to produce the Clinician set, over 500 seconds to run cTAKES, and over 100 seconds to run MetaMap. ClinPhen, uniquely, maintained a nearly constant runtime of 3.68 seconds per patient, even when run on the longest collections of clinical notes (Fig. 3d). On average, ClinPhen is more than 15 times faster than the fastest current extractor.

Replication of findings on patients from different clinical centers

We repeated the above tests on patient data from an independent cohort of diagnosed patients from the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research at Boston Children’s Hospital (see above).

ClinPhen extracts the most accurate phenotypes on cohort from different center

Across the Manton test patients, cTAKES and MetaMap had average precisions of 65% and 64%, respectively. ClinPhen significantly outperformed both at a precision of 75.8%. cTAKES and MetaMap had average phenotype sensitivities of 58% and 72%, respectively. ClinPhen had an average phenotype sensitivity of 72.6% (Supplementary Figure 1a).

Limiting number of phenotypes confirmed to yield better gene rankings

The Manton patients had an average of 267 candidate genes. Without limiting the phenotypes, ClinPhen yielded an average causative gene rank of 14.7. Setting ClinPhen’s phenotype limit to 3 resulted in an average causative gene rank of 8.6 (Supplementary Figure 1b). As with the Stanford test set, causative gene ranks generated by the Exomiser algorithms (hiPhive, Phive, and PhenIX) for the Manton test set were better when the number of phenotypes output by ClinPhen was limited below 10. Again, prioritizing and limiting extracted phenotypes by their information content degraded automatic gene-ranking performance (Supplementary Figure 2b).

ClinPhen-extracted phenotypes confirmed to improve the performance of automatic gene-ranking tools

As with the Stanford test set, Phrank performed best with ClinPhen’s three highest-priority phenotypes, yielding an average causative gene rank of 8.6. Using other sources of phenotypes (all mentioned phenotypes, clinician-extracted phenotypes, cTAKES phenotypes, and MetaMap phenotypes) resulted in lower averages of 13.4, 13.0, 16.5, and 15.4, respectively (Fig. 4a). Data derived from the Manton test set suggest that using the three top-prioritized ClinPhen phenotypes (instead of manually extracted phenotypes) as input to Phrank can save roughly 4–5 hours per case in the diagnostic process.

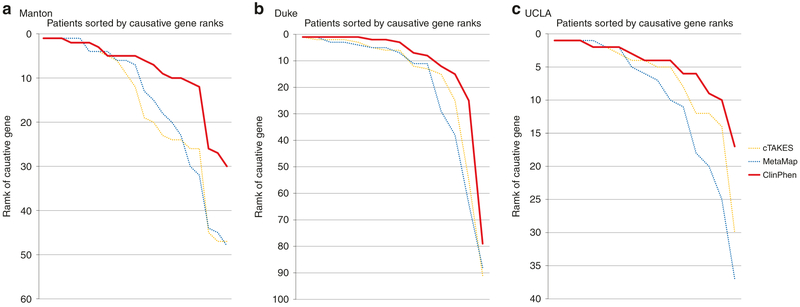

Fig. 4. Replication with patient data from three additional centers.

The same test used to generate Fig. 3c (running Phrank on each patient’s data, given each extracted set of phenotypes, and then sorting the causative gene ranks) was performed using (a) Manton Center patients, (b) Duke Undiagnosed Disease Network (UDN) patients (optical character recognized [OCRed] without manual correction from PDF), and (c) University of California-Los Angeles (UCLA) UDN patients (which had a single consult clinical note per patient) to evaluate the performance of the automatic extractors (ClinPhen, cTAKES, MetaMap). ClinPhen (red line) outperforms other automatic phenotype extractors when its phenotypes are used as input to automatic gene-ranking algorithms (as it did with the Stanford test set).

We performed the same test on the automatic extractors using data from patients at the Duke and UCLA UDN sites. For the Duke test set (with an average of 259 candidate genes), cTAKES’ phenotypes yielded an average Phrank rank of 17.0, MetaMap’s yielded 19.3, and ClinPhen’s top three phenotypes yielded an average rank of 11.3 (Fig. 4b). For the UCLA test set (with an average of 287 candidate genes), cTAKES’ phenotypes yielded an average Phrank rank of 6.9, MetaMap’s yielded 9.8, and ClinPhen’s top three phenotypes yielded an average rank of 4.8 (Fig. 4c).

ClinPhen confirmed to extract phenotypes in less than 5 seconds

The Manton patients’ records had an average of five free-text clinical notes per patient. On these, ClinPhen ran in an average of 3.64 seconds per case. Both cTAKES and MetaMap were more than 20× slower on average, running in an average of 114 seconds and 74.7 seconds, respectively. As with the Stanford test set, ClinPhen’s runtime did not noticeably scale with the length of the record, while those of cTAKES and MetaMap did.

Again, three clinicians (the same as above) manually extracted phenotypes from notes associated with the Manton patients. On average, they compiled a phenotype list in 969 seconds, 266× slower than ClinPhen (Supplementary Figure 1d).

DISCUSSION

Automatic gene-ranking tools expedite genetic disease diagnosis, but currently require manually encoding reported patient phenotypes into phenotype ontology terms. We show here that an automatic phenotype extractor, ClinPhen, produces an accurate phenotype list in under 5 seconds, and potentially saves 3–5 hours of candidate gene evaluation per case.

Most of the diagnosis time saved by ClinPhen stems from its unique ability to prioritize the more-relevant extracted phenotypes. Phenotypes that are likely not caused by a genetic disease can delay a diagnosis. While clinicians use their intuition to filter out these phenotypes, automatic phenotype extractors until now have not done such filtering. Future research can attempt to tackle distinguishing and perhaps differentially weighting phenotypes with either genetic or environmental factors. While current generanking tools we are aware of do not use phenotypes reported in the proband’s family, extracting these correctly may incentivize their incorporation. Attempting to diagnose a case from a handful of the seemingly most telltale phenotypes is common among practitioners.30 However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first work that explicitly tries to estimate an automated method to both prioritize and subset to an optimal number of phenotypes. When limiting ClinPhen’s output to the most-mentioned, then earliest-mentioned phenotypes, automatic gene-ranking algorithms rank the causative gene higher than they would using unfiltered phenotypes, phenotypes ranked by information content,8 or even phenotypes hand-picked by a clinician. ClinPhen enables clinicians to search through 3–5 fewer genes per case, potentially reaching a diagnosis hours sooner.3 Such step-ups in efficiency are needed to meet the high demand and rapid production of diagnostic sequencing data, as well as facilitate periodic case reanalysis.

ClinPhen is available at http://bejerano.stanford.edu/clinphen. It can be immediately incorporated into clinical practice. For example, its output can be added to the clinical note sent to the testing laboratory along with the filled request form. Compared with other phenotype extractors, ClinPhen produces more accurate HPO phenotypes in a shorter amount of time. We optimized ClinPhen to extract HPO terms, commonly used to describe patients with Mendelian diseases.24,35,36 Rapidly growing databases like OMIM37 use HPO terms to describe tens of thousands of disease-phenotype associations. ClinPhen could be used to accelerate the growth of these databases by quickly analyzing patients’ clinical notes and finding new disease-phenotype associations at a rate unachievable by clinical experts.

The large number of undiagnosed patients1,14 with presumed Mendelian diseases necessitates an efficient diagnostic process. The diagnostic process for rare diseases is continually expedited with the help of computer systems that analyze genetic data and prioritize findings.2,38 With the help of ClinPhen, clinicians can handle large batches of patients, and accurately diagnose each case 3–5 hours sooner, advancing the future of precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Julia Buckingham and Morgan Danowski for assistance with obtaining patient data; Paul McDonagh and Margaret Bray for introductions and data sharing; Charlie Curnin, Marta Maria Majcherska, and Colleen McCormack for facilitating access to patient data; and Bejerano Lab members and Elijah Kravets for project feedback. Clinicians’ research was supported by the National Insitutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund, Office of Strategic Coordination/Office of the NIH Director Awards U01HG007690, U01HG007708, U01HG007530, U01HG007942. Manton Center sequence analysis and diagnosis was supported by NIH 1U54HD090255 IDDRC Molecular Genetics Core grant. The Duke UDN site is funded by NIH grant U01HG007672 (principal investigators: V. Shashi and D.B. Goldstein). UCLA′s J.A.M.-A. and R.S. were supported by UDN grant HG007703-05. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. All computational tool building was supported by a Stanford Bio-X Undergraduate Summer Research Program (C.A. D.), a Bio-X Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship (J.B.) and by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Stanford Pediatrics Department (G.B.).

Footnotes

URLs

ClinPhen is publicly available at http://bejerano.stanford.edu/clinphen as a noncommercial, free-to-download tool.

ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0381-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Church G Compelling reasons for repairing human germlines. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1909–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewey FE, Grove ME, Pan C, et al. Clinical interpretation and implications of whole-genome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;311:1035–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephens ZD, Lee SY, Faghri F, et al. Big data: astronomical or genomical? PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164–e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Baets G, Van Durme J, Reumers J, et al. SNPeffect 4.0: on-line prediction of molecular and structural effects of protein-coding variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D935–D939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagadeesh KA, Birgmeier J, Guturu H, et al. Phrank measures phenotype sets similarity to greatly improve Mendelian diagnostic disease prioritization. Genet Med. 2018. July 12; 10.1038/s41436-018-0072-y [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smedley D, Jacobsen JOB, Jager M, et al. Next-generation diagnostics and disease-gene discovery with the Exomiser. Nat Protoc. 2015;10:2004–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson PN, Köhler S, Oellrich A, et al. Improved exome prioritization of disease genes through cross-species phenotype comparison. Genome Res. 2014;24:340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zemojtel T, Köhler S, Mackenroth L, et al. Effective diagnosis of genetic disease by computational phenotype analysis of the disease-associated genome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:252ra123–252ra123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer S, Köhler S, Schulz MH, Robinson PN. Bayesian ontology querying for accurate and noise-tolerant semantic searches. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2502–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James RA, Campbell IM, Chen ES, et al. A visual and curatorial approach to clinical variant prioritization and disease gene discovery in genomewide diagnostics. Genome Med. 2016;8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Javed A, Agrawal S, Ng PC. Phen-Gen: combining phenotype and genotype to analyze rare disorders. Nat Methods. 2014;11:935–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Köhler S, Schulz MH, Krawitz P, et al. Clinical diagnostics in human genetics with semantic similarity searches in ontologies. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:457–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singleton MV, Guthery SL, Voelkerding KV, et al. Phevor combines multiple biomedical ontologies for accurate identification of disease-causing alleles in single individuals and small nuclear families. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smedley D, Schubach M, Jacobsen JO, et al. A whole-genome analysis framework for effective Identification of pathogenic regulatory variants in Mendelian disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:595–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trakadis YJ, Buote C, Therriault J-F, Jacques P-E, Larochelle H, Levesque S. PhenoVar: a phenotype-driven approach in clinical genomics for the diagnosis of polymalformative syndromes. BMC Med Genom. 2014;7:22–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H, Robinson PN, Wang K. Phenolyzer: phenotype-based prioritization of candidate genes for human diseases. Nat Methods. 2015;12:841–843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groza T, Köhler S, Moldenhauer D, et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology: semantic unification of common and raredisease. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;97:111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronson AR. Effective mapping of biomedical text to the UMLS Metathesaurus: the MetaMap program. Proc AMIA Symp. v.2001:17–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/journals/348/. Accessed 28 November 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cui L, Sahoo SS, Lhatoo SD, et al. Complex epilepsy phenotype extraction from narrative clinical discharge summaries. J Biomed Inform. 2014;51:272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonquet C, Shah NH, Musen MA. The Open Biomedical Annotator. Summit Transl Bioinforma. 2009;2009:56–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Köhler S, Vasilevsky NA, Engelstad M, et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2017. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(Database issue): D865–D876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savova GK, Masanz JJ, Ogren PV, et al. Mayo clinical Text Analysis and Knowledge Extraction System (cTAKES): architecture, component evaluation and applications. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shivade C, Raghavan P, Fosler-Lussier E, et al. A review of approaches to identifying patient phenotype cohorts using electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taboada M, Rodríguez H, Martínez D, Pardo M, Sobrido MJ. Automated semantic annotation of rare disease cases: a case study. Database (Oxford). 2014;2014:bau045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cui L, Bozorgi A, Lhatoo SD, Zhang G-Q, Sahoo SS. EpiDEA: extracting structured epilepsy and seizure information from patient discharge summaries for cohort identification. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:1191–1200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao KP, Cai T, Gainer V, et al. Electronic medical records for discovery research in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:1 120–1 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kernohan KD, Hartley T, Alirezaie N, Robinson PN, Dyment DA, Boycott KM. Evaluation of exome filtering techniques for the analysis of clinically relevant genes. Hum Mutat. 2017;39:197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bird S NLTK: the Natural Language Toolkit. COLING-ACL ‘06: Proceedings of the COLING/ACL on Interactive presentation sessions (Sydney, Australia) 2006:69–72. 10.3115/1225403.1225421. Accessed 28 November 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowe HJ, Ferris TA, Hernandez PM, Weber SC. STRIDE-an integrated standards-based translational research informatics platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:391–395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith R An overview of the Tesseract OCR engine. In: Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Vol. 2 Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society; (Parana, Brazil) 2007:629–633. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1304596.1304846. Accessed 14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Son JH, Xie G, Yuan C, et al. Deep phenotyping on electronic health records facilitates genetic diagnosis by clinical exomes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:58–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study. Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature. 2017;542:433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taruscio D, Groft SC, Cederroth H, et al. Undiagnosed Diseases Network International (UDNI): white paper for global actions to meet patient needs. Mol Genet Metab. 2015;116:223–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, Schiettecatte F, Scott AF, Hamosh A. OMIM. org: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM®), an online catalog of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43 (Database issue):D789–D798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jagadeesh KA, Wu DJ, Birgmeier JA, Boneh D, Bejerano G. Deriving genomic diagnoses without revealing patient genomes. Science. 2017;357:692–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.