Abstract

The human gut microbiome is a critical component of digestion, breaking down complex carbohydrates, proteins, and to a lesser extent fats that reach the lower gastrointestinal tract. This process results in a multitude of microbial metabolites that can act both locally and systemically (after being absorbed into the bloodstream). The impact of these biochemicals on human health is complex, as both potentially beneficial and potentially toxic metabolites can be yielded from such microbial pathways, and in some cases, these effects are dependent upon the metabolite concentration or organ locality. The aim of this review is to summarize our current knowledge of how macronutrient metabolism by the gut microbiome influences human health. Metabolites to be discussed include short-chain fatty acids and alcohols (mainly yielded from monosaccharides); ammonia, branched-chain fatty acids, amines, sulfur compounds, phenols, and indoles (derived from amino acids); glycerol and choline derivatives (obtained from the breakdown of lipids); and tertiary cycling of carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Key microbial taxa and related disease states will be referred to in each case, and knowledge gaps that could contribute to our understanding of overall human wellness will be identified.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s40168-019-0704-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Human gut microbiome, Microbial metabolism, Macronutrients, Human health

Introduction

The human gut microbiota is a complex ecosystem of microorganisms that inhabits and critically maintains homeostasis of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [1]. Most of the contributions made by the gut microbiota to the physiology of the human superorganism are related to microbial metabolism [2–4], with bacteria being the largest of these contributors to ecosystem functioning in terms of relative genetic content [2]. In general, microbial metabolism of both exogenous and endogenous substrates to nutrients useable by the host is the direct benefit, but metabolites can also act to modulate the immune system through impacting the physiology and gene expression of host cells [3, 5, 6]. The colon is the major site of this fermentation, as its relatively high transit time and pH coupled with low cell turnover and redox potential presents more favorable conditions for the proliferation of bacteria [7]. However, that does not preclude the importance of the microbiota at other sites, as for example, the small intestinal microbiota has been shown to regulate nutrient absorption and metabolism conducted by the host [8]. Further, the presence of diverse metabolic activity can allow the microbiota to maximally fill the available ecological niches and competitively inhibit colonization by pathogens at all sites [9–11]. The elevated concentrations of the mostly acidic fermentation by-products also locally reduce the pH to create a more inhospitable environment for these incoming invaders [11]. However, specific fermentation pathways carried out by gut microbes can result in the formation of toxic compounds that have the potential to damage the host epithelium and cause inflammation [12–14].

The three macronutrients consumed in the human diet, carbohydrates, proteins, and fat, can reach the colon upon either escaping primary digestion once the amount consumed exceeds the rate of digestion, or resisting primary digestion altogether due to the inherent structural complexity of specific biomolecules [14–16]. Several factors can influence digestive efficiency, which in turn modulates the substrates available to the gut microbiota for consumption, including the form and size of the food particles (affected by cooking and processing), the composition of the meal (affected by the relative ratios of macronutrients and presence of anti-nutrients such as α-amylase inhibitors), and transit time [17]. Transit time in particular has been shown to increase the richness and alter the composition of fecal microbial communities [18], which itself results from several variables including diet, physical activity, genetics, drugs (e.g., caffeine and alcohol), and psychological status [19]. The bioavailability of micronutrients to the host can also be influenced by gut microbial metabolic processes. Colonic bacteria can endogenously synthesize essential co-factors for host energy metabolism and regulation of gene expression, such as B vitamins [20]. Another example includes the biotransformation of exogenous plant-derived polyphenols that have anti-oxidant, anti-cancer, and/or anti-inflammatory properties by the gut microbiota, which improves their uptake by the host [21]. The following review articles on micronutrients are recommended to readers since this topic encompasses a wide scope of material [20, 21], as such, the predominant food sources that act as precursors for the most highly concentrated metabolites will be the focus of discussion here. The aim of this review is thus to describe the major microbial fermentation by-products derived from macronutrients and their subsequent impacts on host health.

Primary degradation

Dietary polysaccharides can be interlinked in complex ways through a diverse array of bonds between monosaccharide units, reflected by the sheer number of carbohydrate-activating enzymes reported to have been found in the human gut microbiome [22]. For example, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron possesses 260 glycoside hydrolases in its genome alone [23], which emphasizes the evolutionary requirement for adaptation in order to maximize utilization of resistant starch and the assortment of fibers available as part of the human diet. In contrast, human cells produce very few of these enzymes (although they do produce amylase to remove α-linked sugar units from starch and can use sugars such as glucose, fructose, sucrose, and lactose in the small intestine) and so rely on gut microbes to harvest energy from the remaining complex carbohydrates [17, 24]. However, once the rate-limiting step of primary degradation is surpassed, the resulting monosaccharides can be rapidly consumed by the gut microbiota with often little interconversion necessary for substrates to enter the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, Entner-Doudoroff pathway, or Pentose phosphate pathway for pyruvate and subsequent ATP production [25]. Conversely, dietary proteins are characterized by conserved peptide bonds that can be broken down by proteases; gut bacteria can produce aspartic-, cysteine-, serine-, and metallo-proteases, but in a typical fecal sample, these bacterial enzymes are far outnumbered by proteases arising from human cells [26]. However, the 20 proteinogenic amino acid building blocks require more interconversion steps for incorporation into biochemical pathways in comparison to monosaccharide units, and thus it is not typical for a given gut microbial species to have the capacity to ferment all amino acids to produce energy [27]. Additionally, microbial incorporation of amino acids from the environment into anabolic processes would conserve more energy in comparison to their catabolic use, by relieving the necessity for amino acid biosynthesis [13]. It is for this reason that amino acids are generally not considered to be as efficient of an energy source as carbohydrates for human gut-associated microbes, and thus no surprise that the gut microbiota preferentially consume carbohydrates over proteins depending on the ratio presented to them [28, 29]. This metabolic hierarchy is analogous to human cells such as intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), in which increased amounts of autophagy occurs when access to microbially derived nutrients is scarce, as shown in germ-free mouse experiments [30]. However, there are notable exceptions to this general rule, as certain species of bacteria have adopted an asaccharolytic lifestyle, likely as a strategy to evade competition (examples included in Table 1).

Table 1.

Major genera present in the human gut microbiome and their metabolisms

| Phylum | Family | Genus | Substrates | Metabolism | End products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria | Bifidobacteriaceae | Bifidobacterium |

Dietary carbohydrates HMO Mucin |

Bifid shunt pathway |

Acetate Ethanol Formate Lactate |

| Bacteroidetes | Bacteroidaceae | Bacteroides |

Dietary carbohydrates HMO Mucin Proteins Succinate |

1,2-Propanediol pathwayI Acetate production Ethanol production Succinate pathway |

1,2-Propanediol Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Propionate Succinate |

| Porphyromonadaceae | Parabacteroides W |

Dietary carbohydrates Proteins Succinate |

Acetate production Succinate pathway |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate Propionate Succinate |

|

| Prevotellaceae | Prevotella NW |

Dietary carbohydrates Proteins Succinate |

Acetate production Succinate pathwayI/A |

Acetate Formate Propionate Succinate |

|

| Rikencellaceae | Alistipes W |

Dietary carbohydrates Proteins Succinate |

Acetate production Succinate pathway |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate Propionate Succinate |

|

| Firmicutes | Clostridiaceae |

Clostridium (Clostridium cluster I) |

Ethanol and Propionate Lactate Proteins Saccharides |

1,2-Propanediol pathwayI Acetate production Acrylate pathway Butyrate kinase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production Valerate production |

1,2-Propanediol Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate Propionate Butyrate Valerate |

| Eubacteriaceae | Eubacterium |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and hHydrogen Formate Lactate Methanol Proteins Saccharides |

Acetogenesis Acetate production Butyryl c CoA transferase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Butyrate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate |

|

| Erysipelotrichaceae | Erysipelatoclostridium |

Proteins Saccharides |

Acetate production Lactate production |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate Lactate |

|

| Lachnospiraceae |

Blautia (Clostridium cluster XIVa) |

1,2-Propanediol Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Dietary carbohydrates Formate Mucin |

1,2-Propanediol pathway Acetogenesis Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production Succinate pathwayI |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate Propanol Propionate Succinate |

|

|

Coprococcus (Clostridium cluster XIVa) |

Acetate Dietary carbohydrates Lactate |

Acrylate pathway Butyrate kinase pathway Butyryl CoA:acetyl CoA transferase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Butyrate Ethanol Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate Lactate Propionate |

||

|

Dorea (Clostridium cluster XIVa) |

Dietary carbohydrates |

Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate |

||

|

Lachnoclostridium (Clostridium cluster XIVa) |

Proteins Saccharides |

Acetate production Butyrate kinase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Butyrate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate |

||

|

Roseburia (Clostridium cluster XIVa) |

1,2-Propanediol Acetate Dietary carbohydrates |

1,2-Propanediol pathway Acetate production Butyryl CoA:acetyl CoA transferase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Butyrate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate Propanol Propionate |

||

| Lactobacillaceae | Lactobacillus |

1,2-Propanediol Saccharides |

1,2-Propanediol pathway Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Ethanol Formate Lactate Propanol Propionate |

|

| Ruminococcaceae |

Faecalibacterium (Clostridium cluster IV) |

Acetate | Butyryl CoA:acetyl CoA transferase pathway |

Butyrate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate |

|

|

Ruminiclostridium W (Specifically Clostridium cluster IV, which is currently grouped with Clostridium cluster III) |

Dietary carbohydrates Proteins |

Acetate production Butyrate kinase pathway Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Butyrate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate |

||

|

Ruminococcus (Clostridium cluster IV) |

Dietary carbohydrates |

Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production Succinate pathwayI |

Acetate Ethanol Formate Lactate Succinate |

||

| Streptococcaceae | Streptococcus NW |

Mucin Saccharides |

Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production |

Acetate Ethanol Formate Lactate |

|

| Veillonellaceae | Veillonella |

1,2-Propanediol Lactate Proteins Saccharides Succinate |

1,2-Propanediol pathway Acetate production Lactate production Succinate pathway |

Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Formate Lactate Propanol Propionate Succinate |

|

| Proteobacteria | Enterobacteriaceae | Escherichia |

Proteins Saccharides |

1,2-Propanediol pathwayI 2,3-Butanediol production Acetate production Ethanol production Lactate production Succinate pathwayI |

1,2-Propanediol 2,3-Butanediol Acetate Carbon dioxide and Hydrogen Ethanol Formate Lactate Succinate |

Taxa that are listed as part of a ‘core’ gut microbiota found by Falony et al. are in bold [31]. Those genera that were core components of exclusively the ‘Western’ cohorts are denoted with a ‘W’ superscript, whereas the exclusively ‘non-Western’ ones are denoted with a ‘NW’ superscript. If the core taxon could not be resolved to the genus level, the bacterial families are bolded. For the bacterial families that do not already contain several core genera, the most commonly described genus of the human gut microbiome for that family is also listed as a representative. Additionally, genera found to be highly prevalent among the human population, yet typically present in low abundance, are underlined [32]. The possible substrates consumed, metabolisms, and metabolites for each genus are listed. These metabolisms were inferred from the following articles [28, 33–61]. Note that many of these metabolisms are species-specific, and only the substrates commonly utilized among species of the genus are listed. Further, only the most abundant metabolites produced from pyruvate catabolism (i.e., saccharolytic processes) are given. When a particular metabolic pathway is denoted with an ‘I’ superscript, the microorganisms do not possess the full enzymatic pathway, but rather produce the typical intermediate as an end-product instead. Likewise, an ‘I/A’ indicates species of that genus may possess either the full or half pathway

Pyruvate metabolism

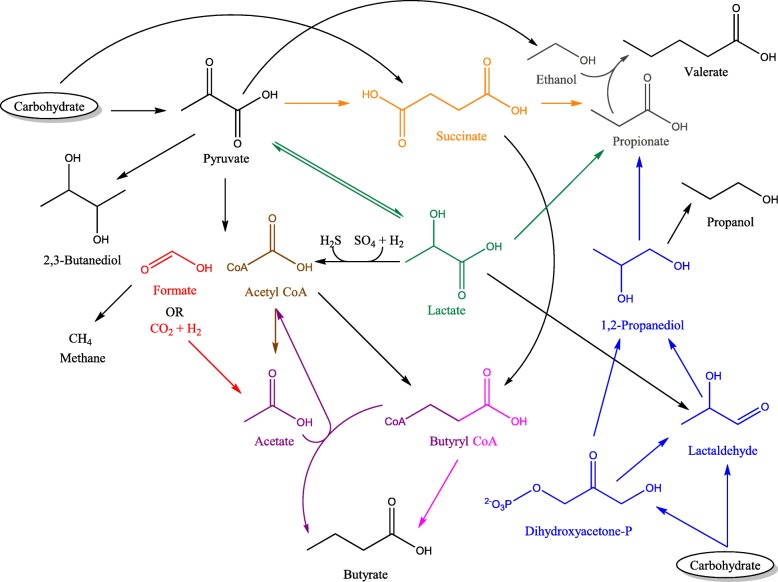

Once pyruvate is produced, primarily from carbohydrates but also from other substrates, the human gut microbiota has developed several fermentation strategies to further generate energy, which are depicted in Fig. 1. Pyruvate can either be catabolized into succinate, lactate, or acetyl-CoA. However, these intermediates do not reach high concentrations in typical fecal samples, as they can be further metabolized by cross-feeders, producing the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) acetate, propionate, and butyrate (Table 1) [33]. These fecal metabolites are the most abundant and well-studied microbial end-products, since their effects are physiologically important: for example, host intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) utilize them as a source of fuel [62]. Indeed, SCFAs contribute approximately 10% of the caloric content required by the human body for optimal functioning [63]. Butyrate is the most preferred source of energy in this respect; its consumption improves the integrity of IECs by promoting tight junctions, cell proliferation, and increasing mucin production by Goblet cells [63, 64]. Butyrate also exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, through stimulating both IECs and antigen presenting cells (APCs) to produce the cytokines TGF-β, IL-10, and IL-18, and inducing the differentiation of naïve T cells to T regulatory cells [65]. Acetate and propionate can also be consumed by IECs (though to a much lesser degree than butyrate) and have some anti-inflammatory effects [33, 63]. Both acetate and propionate can dampen pro-inflammatory cytokine production mediated by toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 stimulation, and propionate, similar to butyrate, can induce the differentiation of T cells to T regulatory cells [33, 34]. Excess SCFAs that are not metabolized by IECs are transported via the hepatic vein to the liver, where they can be incorporated as precursors into gluconeogenesis, lipogenesis, and cholesterologenesis [62]. Specifically, propionate is gluconeogenic, whereas acetate and butyrate are lipogenic. The ratio of propionate to acetate is thought to be particularly important, as propionate can inhibit the conversion of acetate to cholesterol and fat [62, 66]. Indeed, propionate administration alone can reduce intra-abdominal tissue accretion and intrahepatocellular lipid content in overweight adults [67]. The role(s) of SCFAs in glucose homeostasis is/are not yet fully elucidated, although preliminary work has additionally suggested a beneficial effect, since plasma insulin levels are inversely related to serum acetate concentrations [62, 68].

Fig. 1.

Strategies of pyruvate catabolism by the human gut microbiome. Carbohydrates are first degraded to pyruvate. Pyruvate may then be converted to succinate, lactate, acetyl CoA + formate/carbon dioxide + hydrogen, ethanol, or 2,3-butanediol. Succinate may, however, also be a direct product of carbohydrate fermentation. Succinate and lactate do not typically reach high concentrations in fecal samples, as they can be further catabolized to produce energy, but certain species do secrete them as their final fermentation end-product, which enables cross-feeding. Acetate is produced by two pathways; (1) through direct conversion of acetyl CoA for the generation of energy (brown) or (2) acetogenesis (red). Formate/carbon dioxide + hydrogen can also be substrates for methanogenesis. Propionate is produced by three pathways; (1) the succinate pathway (orange), (2) the acrylate pathway (green), or (3) the 1,2-propanediol pathway (blue). 1,2-Propanediol is synthesized from lactaldehyde or dihydroxyacetone phosphate, which both are products of deoxy sugar fermentation (e.g., fucose, rhamnose). Alternatively, lactaldehyde can be produced from lactate, or 1,2-propanediol can be fermented to propanol. Propionate can be coupled with ethanol for fermentation to valerate (gray). The precursor for butyrate, butyryl CoA, is generated from either acetyl CoA or succinate. Butyrate is then produced by two pathways; (1) the butyrate kinase pathway (pink) or (2) the butyryl CoA:acetyl CoA transferase pathway (purple). Butyrate-producing bacteria may also cross-feed on lactate, converting it back to pyruvate. Lactate may also be catabolized as part of sulfate reduction

In addition to SCFAs, small but significant amounts of alcohols, including ethanol, propanol, and 2,3-butanediol, can be formed as end-products of pyruvate fermentation (Table 1; Fig. 1). A further alcohol, methanol, is also produced by the gut microbiota as a result of pectin degradation, demethylation of endogenous cellular proteins for regulation, or vitamin B12 synthesis [69] rather than fermentation. Alcohols are transported to the liver, where the detoxification process involves their conversion to SCFAs, although through pathways that yield toxic aldehydes as precursors [69–71]. Higher concentrations of endogenous alcohols are thus thought to be a contributing factor to the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [70, 72]. Proteobacteria are known to be particularly capable of alcohol generation [69, 72], and are, interestingly, positively associated with dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [73], a disease in which patients are predisposed to developing NAFLD [74]. However, alcohols can also be detoxified by many members of the gut microbiota via pathways similar to those present in mammalian cells, regulating their concentration [69]. Additionally, methanol can be used as a substrate for methanogenesis or acetogenesis [35, 69, 75], and ethanol can be coupled to propionate for fermentation to the SCFA, valerate (Table 1) [36]. Valerate is a poorly studied metabolite, but it has been shown to inhibit growth of cancerous cells [76] and to prevent vegetative growth of Clostridioides difficile both in vitro and in vivo [36].

Hydrogenotrophy

The human body may rapidly absorb SCFAs and alcohols, which helps to reduce their nascent concentrations within the colon, allowing for continued favorable reaction kinetics [15, 77] . In addition, the gaseous fermentation by-products, carbon dioxide and hydrogen, must also be removed to help drive metabolism forward. The utilization of these substrates is mainly the result of cross-feeding between gut microbiota members, rather than host absorption. Three main strategies for this activity exist in the human gut: (1) acetogens, for example, Blautia spp., convert carbon dioxide plus hydrogen to acetate (further examples included in Table 1); (2) methanogens, namely archaea such as Methanobrevibacter, convert carbon dioxide plus hydrogen to methane; and (3) sulfate reducing bacteria, including Desulfovibrio, convert sulfate plus hydrogen to hydrogen sulfide [15, 37]. A higher abundance of these cross-feeders may improve the overall efficiency of metabolism in the gut; for example, an increase in methanogens is observed in the GI tract of anorexia nervosa patients, which may be a coping strategy by the gut microbiota in response to a lack of food sources [78, 79]. Sulfate-reducing bacteria are the most efficient of the hydrogenotrophs, but require a source of sulfate; in the gut, the most prominent source of sulfate is sulfated glycans [80]. Although some of these glycans may be obtained from the diet, the most accessible source is mucin produced by the host [38]. Sulfate-reducing bacteria obtain sulfate from these substrates via cross-feeding with microbes such as Bacteroides, which produce sulfatases [80, 81]. Hydrogen sulfide is both directly toxic to IECs through inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase, and pro-inflammatory via activation of T helper 17 cells [82, 83]. Hydrogen sulfide can additionally directly act on disulfide bonds in mucin to further facilitate mucin degradation [84]. Elevated hydrogen sulfide concentrations and increased proportions of sulfate-reducing bacteria are reported in IBD [85].

Catabolism of amino acids

The digestibility of proteins by the host is more variable than that of carbohydrates and fats, and is influenced by the previously mentioned factors of food processing, macronutrient ratios, and transit time [14, 18], in addition to its source (e.g., plant or animal), which also leads to different amino acid compositions available to the gut microbiota [14, 86]. The extra steps of interconversion required for amino acid fermentation yield a large diversity of by-products. Protein catabolism in the gut generally has a negative connotation, as compounds that are toxic to the host can result from this process, including amines, phenols/indoles, and sulfurous compounds [12–14]. However, it is important to note that not all amino acids are fermented to toxic products as a result of gut microbial activity; in fact, the most abundant end products are SCFAs [13, 14]. Therefore, it may not be protein catabolism per se that negatively impacts the host, but instead specific metabolisms or overall increased protein fermentation activity. It is thus important to examine these subtleties. A microbe can exhibit one of two strategies for the initial step of amino acid catabolism, either deamination to produce a carboxylic acid plus ammonia or decarboxylation to produce an amine plus carbon dioxide [12]. Ammonia can inhibit mitochondrial oxygen consumption and decrease SCFA catabolism by IECs, which has led to the assumption that excess ammonia production can negatively impact the host [87–89]. However, the gut microbiota also rapidly assimilates ammonia into microbial amino acid biosynthetic processes [13], and host IECs can additionally control ammonia concentration through conversion to citrulline and glutamine, or through slow release into the bloodstream [90, 91]. It is thus unclear how much protein catabolism is necessary to achieve toxic ammonia concentrations, and this may vary between hosts. This uncertainty, coupled with the multiple negative impacts amines can have on the host (discussed below), have led to speculation that deamination would improve host outcomes. Fortunately, deamination appears to be the more common strategy of amino acid catabolism by the gut microbiota, because high concentrations of SCFAs are produced from amino acid degradation via this pathway [12, 13]. The next steps depend on the class of amino acid starting substrate, with most eventually resulting in tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates, pyruvate, or coenzyme A-linked SCFA precursors [39, 75]. An exception would be the series of Stickland reactions exhibited by certain Clostridia, in which a coupled oxidation and reduction of two amino acids occurs as an alternative to using hydrogen ions as the electron acceptor [40, 41]. Phosphate is simultaneously added to the reduced amino acid in this case, and thus oxidative phosphorylation for the production of ATP can occur directly from the resultant acyl phosphate. In turn, branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs), such as isovalerate and isobutyrate, can be produced as end-products. Additionally, some gut microbial species, mainly from the class Bacilli, also possess a specialized branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase complex to yield energy from the oxidized forms of the branched-chain amino acids directly, which also leads to BCFA production [13, 75]. The major SCFA and BCFA products generated from degradation of each amino acid are presented in Table 2. BCFAs are often used as a biomarker of protein catabolism, with the promoted goal to reduce their concentration in order to improve health outcomes [14]. However, little is actually known about the impact of BCFAs on host health. In fact, preliminary work has shown that BCFAs are able to modulate glucose and lipid metabolism in the liver similarly to SCFAs [93], and isobutyrate can be used as a fuel source by IECs when butyrate is scarce [94]. What is undisputed, however, are the negative consequences of the pro-inflammatory, cytotoxic, and neuroactive compounds yielded from the sulfur-containing, basic and aromatic amino acids.

Table 2.

Major products of amino acid fermentation by the human gut microbiota

| Amino acid | Amino acid class | Major products |

|---|---|---|

| Aspartate | Acidic | Propionate |

| Glutamate | Acidic | Acetate, Butyrate |

| Alanine | Aliphatic | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate |

| Glycine | Aliphatic |

Acetate Methylamine |

| Isoleucine | Aliphatic | 2-Methylbutyrate or converted to Valine |

| Leucine | Aliphatic | Isovalerate |

| Proline | Aliphatic | Acetate |

| Valine | Aliphatic | Isobutyrate |

| Asparagine | Amidic | Converted to aspartate |

| Glutamine | Amidic | Converted to glutamate |

| Phenylalanine | Aromatic |

Phenolic SCFA Phenylethylamine |

| Tryptophan | Aromatic |

Indolic SCFA Tryptamine |

| Tyrosine | Aromatic |

4-Hydroxyphenolic SCFA Tyramine |

| Arginine | Basic |

Converted to other amino acids (mainly Ornithine) Agmatine |

| Histidine | Basic |

Acetate, Butyrate Histamine |

| Lysine | Basic |

Acetate, Butyrate Cadaverine |

| Serine | Hydroxylic | Butyrate |

| Threonine | Hydroxylic | Acetate, Propionate, Butyrate |

| Cysteine | Sulfur-containing | Acetate, Butyrate, Hydrogen sulfide |

| Methionine | Sulfur-containing | Propionate, Butyrate, Methanethiol |

Listed are the compounds found to be above 1 mM concentration in in vitro fermentation experiments conducted by Smith and Macfarlane [92], in addition to the biogenic amines that can be produced by decarboxylation [12, 13]. Underlined are the products indicated as most abundant as reported in a review article by Fan et al. [12]

Sulfur-containing amino acids

Catabolism of the sulfur-containing amino acids, cysteine and methionine, results in the production of hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol, respectively [13, 14], and a large number of taxonomically diverse bacterial species contain the requisite degradative enzymes within their genomes, including members of the Proteobacteria phylum, the Bacilli class, and the Clostridium and Bifidobacterium genera [13, 75]. Hydrogen sulfide can be methylated to methanethiol, which can be further methylated to dimethyl sulfide, and this methylation is thought to be part of the detoxification process due to the progressively less toxic nature of these compounds [95]. However, methanethiol may also be converted to hydrogen sulfide, then oxidized to sulfate, for detoxification; this sulfate can then be utilized by sulfate-reducing bacteria [80, 81, 95]. Indeed, this latter reaction has been observed in cecal tissue, and is part of the sulfur cycle of the gut [96]. The impact of hydrogen sulfide on host health has already been discussed, thus the focus will shift to the biogenic amines produced by basic amino acid fermentation and the phenol/indole compounds produced by aromatic amino acid fermentation.

Basic amino acids

A wide diversity of bacterial species within the gut microbiota can decarboxylate the basic amino acids, thus resulting in the formation of amine by-products shown in Additional file 1, including bifidobacteria, clostridia, lactobacilli, enterococci, streptococci, and members of the Enterobacteriaceae family [97]. The catabolism of arginine can produce agmatine by deamination, and/or putrescine, spermidine, and spermine as part of the polyamine synthesis pathway (Additional file 1). Agmatine inhibits the proliferation of IECs, which is thought to stem from its ability to reduce the synthesis and promote the degradation of other polyamines [98]. This effect may not be negative depending on the context; for example, the resultant decrease of fatty acid metabolism in tissues reduced both weight gain and the hormonal derangements associated with obesity in rats fed a high fat chow [99]. Agmatine also may be anti-inflammatory through inhibition of nitric oxide synthase [100], and is a candidate neurotransmitter, with agonism for α2-adenoceptors and imidazoline binding sites, while simultaneously blocking ligand-gated cation channels (NMDA class) [101]. The latter activity has therapeutic potential for remediating some forms of hyperalgesia and for its neuroprotectivity. Putrescine, on the other hand, is essential for the proliferation of IECs [102]. It is the precursor to spermidine/spermine, which are both able to relieve oxidative stress and promote cellular longevity through autophagy stimulation [103]. All three polyamines improve the integrity of the gut by increasing expression of tight junction proteins [104], promoting intestinal restitution [105] and increasing mucus secretion [105, 106]. Finally, both putrescine and spermine are able to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α [107, 108]. Therefore, any benefits of agmatine must be weighed against its consequent reduction of these polyamines; it may be effective in the treatment of certain conditions such as metabolic syndrome but could be detrimental in excess under normal conditions. Arginine can additionally be converted to glutamate, which can be deaminated to produce 4-aminobutryate (GABA). GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system, and alterations in the expression of its receptor have been linked to the pathogenesis of depression and anxiety [109]. Administration of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria that produce GABA to mice and rats has resulted in a decrease of depressive behaviors, a reduction of corticosterone induced stress and anxiety, and lessened visceral pain sensation [109–111]. GABA can additionally regulate the proliferation of T cells and thus has immunomodulatory properties [112]. Interestingly, chronic GI inflammation not only induces anxiety in mice, but depression and anxiety often present comorbidity with GI disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [109, 113].

The catabolism of histidine can produce histamine (Additional file 1). Histamine may be synonymous with its exertion of inflammation in allergic responses, but bacterially produced histamine has actually been shown to inhibit the production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α in vivo [114], and IL-1, and IL-12 in vitro [115], while simultaneously preventing intestinal bacterial translocation. Histamine is also a neurotransmitter, modulating several processes such as wakefulness, motor control, dendritic cell activity, pain perception, and learning and memory [116]. Low levels of histamine are associated with Alzheimer’s disease, convulsions, and seizures, and increasing its concentration has antinociceptive properties [117]. However, there is likely a range of suitable concentration, as high levels of histamine are associated with sleep disorders, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and autism [116, 117].

The catabolism of lysine can produce cadaverine (Additional file 1). Cadaverine is a poorly studied metabolite; it can be toxic, but only in high amounts [13, 97]. Cadaverine has, however, been shown to potentiate histamine toxicity [118] and higher concentrations of cadaverine are associated with ulcerative colitis (UC) [119].

Aromatic amino acids

Aromatic amino acid degradation can yield a wide diversity of indolic and phenolic compounds that can act as toxins or neurotransmitters as shown in Additional file 2. The catabolism of tryptophan can produce tryptamine and indoles (Additional file 2). Tryptamine is a neurotransmitter that plays a role in regulating intestinal motility and immune function [120]. Particularly, it is able to interact with both indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor to heighten immune surveillance, and dampen the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, respectively [121, 122]. A lack of these activities has therefore been implicated in the pathology of IBD; although, it should be noted that most tryptophan metabolites can interact with these receptors, thus it is not tryptamine-specific [13, 120, 122]. Tryptamine can also both potentiate the inhibitory response of cells to serotonin and induce its release from enteroendocrine cells [120, 123]. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in many processes including mood, appetite, hemostasis, immunity, and bone development [13, 124]. Its dysregulation is thus reported in many disorders, including IBD [125], IBS [126], cardiovascular disease [127], and osteoporosis [128]. Tryptophan decarboxylation is a rare activity among species of the gut microbiota, but certain Firmicutes have been found to be capable of it, including the IBD-associated species, Ruminococcus gnavus [129, 130]. Indole, on the other hand, is a major bacterial metabolite of tryptophan, produced by many species of Bacteroides and Enterobacteriaceae [120]. It plays an important role in host defense, by interacting with the pregnane X receptor and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor [120]. This activity fortifies the intestinal barrier by increasing tight junction protein expression and downregulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [120, 131]. It also induces glucagon like peptide-1 (an incretin) secretion by enteroendocrine cells, inhibiting gastric secretion and motility, to promote satiety [132, 133]. Indole is additionally a signaling molecule for bacteria, influencing motility, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and virulence, and shown to inhibit the colonization capabilities of pathogens such as Salmonella enterica [134]. However, indole overproduction can increase its export to the liver, where it is sulfated to indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin associated with chronic kidney disease [135]. Further, its effects as a signaling molecule for both enteroendocrine cells and bacteria are dose dependent, with high concentrations rendering it ineffective [120, 132, 134]. Other indole metabolites are additionally able to interact with the pregnane X receptor and/or aryl hydrocarbon receptor in a similar fashion, thus benefiting the host, but are less well studied [120].

The catabolism of tyrosine can produce tyramine, phenols, and p-coumarate (Additional file 2). Tyramine is a neurotransmitter that can be produced by certain gut bacteria via decarboxylation, including Enterococcus and Enterobacteriaceae [97]. It is infamous for causing the ‘cheese reaction’ hypertensive crisis in individuals taking monoamine inhibitor class drugs, although it can additionally cause migraines and hypertension in sensitive individuals or a mild rise in blood pressure when consumed in excess by the general populace [136]. Tyramine facilitates the release of norepinephrine that induces peripheral vasoconstriction, elevates blood glucose levels, and increases cardiac output and respiration [137]. It has also been shown to increase the synthesis of serotonin by enteroendocrine cells in the gut, elevating its release into circulation [124]. Phenol and p-cresol are phenolic metabolites that have been shown to both decrease the integrity of the gut epithelium and the viability of IECs [138, 139], and can be produced by many gut bacterial species, such as members of the Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium clusters I, XI, and XIVa [140]. P-cresol in particular is genotoxic, elevates the production of superoxide, and inhibits proliferation of IECs [141]. P-cresol may additionally be sulfated to cresyl sulfate in the gut or liver, which has been found to suppress the T helper 1-mediated immune response in mice [142], and, interestingly, phenolic sulfation was found to be impaired in the gut mucosa of UC patients [143]. Indeed, the colonic damage induced by unconjugated phenols is similar to that observed in IBD [138]. Cresyl sulfate is also associated with chronic kidney disease, however, as it can damage renal tubular cells through induction of oxidative stress [144]. This compound is also particularly elevated in the urine of autistic patients, but a causative link in this case has not been elucidated [145].

The catabolism of phenylalanine can produce phenylethylamine and trans-cinnamic acid (Additional file 2). Unlike tyrosine and tryptophan, little is known about these phenylalanine-derived metabolites. Phenylethylamine is a neurotransmitter that functions as an ‘endogenous amphetamine’ yielded from decarboxylation [136]. Through facilitating the release of catecholamine and serotonin, phenylethylamine in turn elevates mood, energy, and attention [146]. However, it has been reported that ingesting phenylethylamine can induce headache, dizziness, and discomfort in individuals with a reduced ability to convert it to phenylacetate, suggesting excessive amounts have negative consequences [136]. In terms of its production in the gut, phenylethylamine has thus been positively associated with Crohn’s disease and negatively correlated with Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in one study [147]. The conversion of phenylalanine to trans-cinnamate and tyrosine to p-coumaric acid results in increased phenylpropionate and 4-hydroxyphenylpropionate concentrations, which in turn produce urinary metabolites associated with the ‘chlorogenic acid’ phenotype in rats, as suggested by Clayton [148]. These metabolic pathways were found to so far specifically occur within species of Clostridium and Peptostreptococcus, respectively [149, 150]. The chlorogenic acid phenotype is associated with both autism and schizophrenia, suggesting a role of altered aromatic amino acid metabolism in these disorders [148, 151, 152]. However, further research is still needed, as there remains no mechanistic explanation of these metabolites toward disease development. Further, both trans-cinnamic acid and p-coumaric acid are negatively associated with cardiovascular disease [153, 154]. P-coumaric acid, in particular, is a common phenolic compound derived from plant matter that has anti-inflammatory properties, and has been demonstrated to prevent platelet aggregation [155]. Thus, these metabolites may simply be an indicator of altered microbial metabolism in general, when found in excess.

Catabolism of lipids

A very small proportion of total dietary fat reaches the colon (< 5%) [16, 156]. Microorganisms in the gut are known to possess lipases, which can degrade triglycerides and phospholipids into their polar head groups and free lipids [16, 157]. Triglycerides represent 95% of total dietary fat, whereas phospholipids, mostly in the form of phosphotidylcholine, constitute a minor portion, but are also derived endogenously from bile acids [158]. Certain bacteria inhabiting the GI tract, including species of lactobacilli, enterococci, clostridia, and Proteobacteria, can utilize the backbone of triglycerides as an electron sink, reducing glycerol to 1,3-propanediol [159]. 3-Hydroxypropanal (reuterin) is an intermediate of this process that has been reported to accumulate extracellularly in cultures of Lactobacillus and Enterococcus spp. [160]. Reuterin has antimicrobial properties acting against pathogens and commensals alike [161], but it can also be spontaneously dehydrated to acrolein [71]. Acrolein is a highly reactive genotoxin, with an equivalent mutagenic potency to formaldehyde, raising concerns about this metabolic process [71, 159]. Meanwhile, choline can additionally be metabolized to trimethylamine by species of the gut microbiota, particularly Clostridia (especially members of Clostridium cluster XIVa and Eubacterium spp.) and Proteobacteria [162, 163]. Trimethylamine is oxidized in the liver to trimethylamine N-oxide [163, 164], which exacerbates atherosclerosis by promoting the formation of foam cells (lipid-laden macrophages) [164] and altering cholesterol transport [165]. High levels of serum trimethylamine N-oxide are thus associated with cardiovascular disease [166] and atherosclerosis [167]. However, it should be noted that active research in these areas is in its early stages, and thus the link between the gut microbiota-mediated lipid head group metabolism and health consequences is still unclear. For example, a study on the metabolism of glycerol by fecal microbial communities found that only a subset could reduce it to 1,3-propanediol, and the authors did not detect any reuterin [159]. Further, some members of the gut microbiota (e.g., methylotrophs) can breakdown trimethylamine to dimethylamine, so the actual amount of trimethylamine that is available for transportation to the liver can be diverted, and this is likely to be influenced by inter-individual variability in the composition of the gut microbiota [168].

In contrast to the polar head groups, microorganisms are not thought to have the ability to catabolize free lipids in the anaerobic environment of the gut [169]. However, free lipids have antimicrobial properties [169, 170] and can directly interact with host pattern recognition receptors. Particularly, saturated fatty acids are TLR4 agonists that promote inflammation [171], whereas omega-3 unsaturated fatty acids are TLR4 antagonists that prevent inflammation [172]. Interestingly, chronic inflammation co-occurring with obesity has been well described [173], and could be a result of the aforementioned pro-inflammatory properties of free lipids, the lack of anti-inflammatory SCFAs produced from carbohydrate fermentation (high-fat diets tend to be low in carbohydrates), or a combination of both. High-fat diets do have a reported impact on the composition of the gut microbiota, yet it is unclear whether it is the increased fat content per se or the relative decrease in carbohydrates, which often accompanies these diets, that is the chief influencer [16, 169]. Indeed, Morales et al. observed that a high-fat diet including fiber supplementation induces inflammation without altering the composition of the gut microbiota [16]. Regardless, the gut microbiota is required for the development of obesity, as shown in GF mice experiments, because of the ability of SCFAs to alter energy balance as previously discussed [174].

Effect on endogenous substrate utilization

Metabolism of exogenous substrates greatly affects the use of endogenous substrates by the gut microbiota. Dietary fiber reduces the degradation of mucin, and the utilization of mucin is thought to cycle daily depending on the availability of food sources [175, 176]. Mucin is a sulfated glycoprotein [38], thus the same concepts of carbohydrate and protein degradation from dietary sources discussed above apply. However, it should be noted that mucin turnover by the gut microbiota is a naturally occurring process, and only when it occurs in elevated amounts does it have negative connotations. For example, Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-utilizing specialist that is depleted in the GI tract of IBD [177] and metabolic syndrome [178] patients. A. muciniphila has a demonstrated ability to cross-talk with host cells, promoting an increase in concentration of glucagon-like peptides, 2-arabinoglycerol, and antimicrobial peptides that improve barrier function, reduce inflammation, and induce proliferation of IECs [179]. Through this communication, A. muciniphila also, paradoxically, restored the thickness of the mucin layer in obese mice. Dietary fat intake can also alter the profile of bile acids. Dairy-derived saturated lipids increase the relative amount of taurine-conjugation, and this sulfur-containing compound leads to the expansion of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the gut [180]. Bile acid turnover is, however, a naturally occurring process, which modulates bile acid reabsorption, inflammation, triglyceride control, and glucose homeostasis from IEC signaling [181].

Conclusions

The critical contributions of the gut microbiota toward human digestion have just begun to be elucidated. Particularly, more recent research is revealing how the impacts of microbial metabolism extend beyond the GI tract, denoting the so-called gut-brain (e.g., biogenic amines acting as neurotransmitters) [182], gut-liver (e.g., alcohols) [183], gut-kidney (e.g., uremic toxins such as cresyl sulfate) [135], and gut-heart (e.g., trimethylamine) [184] axes. The primary focus to date has been on the SCFAs derived mainly from complex carbohydrates, and crucial knowledge gaps still remain in this area, specifically on how the SCFAs modulate glucose metabolism and fat deposition upon reaching the liver. However, the degradation of proteins and fats are comparatively less well understood. Due to both the diversity of metabolites that can be yielded and the complexity of microbial pathways, which can act as a self-regulating system that removes toxic by-products, it is not merely a matter of such processes effecting health positively or negatively, but rather how they are balanced. Further, the presentation of these substrates to the gut microbiota, as influenced by the relatively understudied host digestive processes occurring in the small intestine, is equally important. Future work could therefore aim to determine which of these pathways are upregulated and downregulated in disease states, such as autism and depression (gut-brain), NAFLD (gut-liver), chronic kidney disease (gut-kidney), and cardiovascular disease (gut-heart). Further, a combination of human- and culture- (in vitro and in vivo) based studies could resolve the spectrum of protein and fat degradation present among healthy individuals, in order to further our understanding of nutrient cycling in gut microbial ecosystems, and thus gain a necessary perspective for improving wellness.

Additional files

Pathways of basic amino acid fermentation by the human gut microbiome. Pathways have been simplifed to show major end-products. Where ‘SCFA’ is listed, either acetate, propionate or butyrate can result from catabolism of the substrate. (PDF 181 kb)

Pathways of aromatic amino acid fermentation by the human gut microbiome. Pathways have been simplified to show major end-products. Where ‘SCFA’ is listed, either acetate, propionate or butyrate can result from catabolism of the substrate. (PDF 174 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge the National Science and Research Council of Canada scholarship and Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities scholarship to KO for providing funding.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen presenting cell

- BCFA

Branched-chain fatty acid

- GABA

4-Aminobutryate

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IBS

Irritable bowel syndrome

- IEC

Intestinal epithelial cell

- NAFLD

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- SCFA

Short-chain fatty acid

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- UC

Ulcerative colitis

Authors’ contributions

KO researched and wrote the manuscript. EA-V oversaw editing of the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

EA-V is the co-founder and CSO of NuBiyota LLC, a company which is working to commercialize human gut-derived microbial communities for use in medical indications.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kaitlyn Oliphant, Email: koliphan@uoguelph.ca.

Emma Allen-Vercoe, Email: eav@uoguelph.ca.

References

- 1.Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823–1836. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, Jia H, Cai X, Zhong H, Feng Q, Sunagawa S, et al. An integrated catalog of reference genes in the human gut microbiome. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett C, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project: exploring the microbial part of ourselves in a changing world. Nature. 2007;449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Human Microbiome Project Consortium Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belkaid Y, Hand T. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spiljar M, Merkler D, Trajkovski M. The immune system bridges the gut microbiota with systemic energy homeostasis: focus on TLRs, mucosal barrier, and SCFAs. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1353. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillman ET, Lu H, Yao T, Nakatsu CH. Microbial ecology along the gastrointestinal tract. Microbes Environ. 2017;32:300–313. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME17017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez-Guryn K, Hubert N, Frazier K, Urlass S, Musch MW, Ojeda P, et al. Small intestine microbiota regulate host digestive and absorptive adaptive responses to dietary lipids. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sommer F, Anderson JM, Bharti R, Raes J, Rosenstiel P. The resilience of the intestinal microbiota influences health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:630–638. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Theriot CM, Young VB. Interactions between the gastrointestinal microbiome and Clostridium difficile. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:445–461. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stecher B, Hardt W-D. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan P, Li L, Rezaei A, Eslamfam S, Che D, Ma X. Metabolites of dietary protein and peptides by intestinal microbes and their impacts on gut. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2015;16:646–654. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150630133657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portune KJ, Beaumont M, Davila A-M, Tomé D, Blachier F, Sanz Y. Gut microbiota role in dietary protein metabolism and health-related outcomes: the two sides of the coin. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016;57:213–232. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao CK, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Review article: insights into colonic protein fermentation, its modulation and potential health implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:181–196. doi: 10.1111/apt.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krajmalnik-Brown R, Ilhan Z-E, Kang D-W, DiBaise JK. Effects of gut microbes on nutrient absorption and energy regulation. Nutr Clin Pract Off Publ Am Soc Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012;27:201–214. doi: 10.1177/0884533611436116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales P, Fujio S, Navarrete P, Ugalde JA, Magne F, Carrasco-Pozo C, et al. Impact of dietary lipids on colonic function and microbiota: an experimental approach involving orlistat-induced fat malabsorption in human volunteers. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e161. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong JMW, Jenkins DJA. Carbohydrate digestibility and metabolic effects. J Nutr. 2007;137:2539S–2546S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2539S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roager HM, Hansen LBS, Bahl MI, Frandsen HL, Carvalho V, Gøbel RJ, et al. Colonic transit time is related to bacterial metabolism and mucosal turnover in the gut. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16093. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Degen LP, Phillips SF. Variability of gastrointestinal transit in healthy women and men. Gut. 1996;39:299–305. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biesalski HK. Nutrition meets the microbiome: micronutrients and the microbiota. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1372:53–64. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozdal T, Sela DA, Xiao J, Boyacioglu D, Chen F, Capanoglu E. The reciprocal interactions between polyphenols and gut microbiota and effects on bioaccessibility. Nutrients. 2016;8:78. doi: 10.3390/nu8020078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharya T, Ghosh TS, Mande SS. Global profiling of carbohydrate active enzymes in human gut microbiome. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Bjursell MK, Himrod J, Deng S, Carmichael LK, Chiang HC, et al. A genomic view of the human-Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron symbiosis. Science. 2003;299:2074–2076. doi: 10.1126/science.1080029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh RK, Chang H-W, Yan D, Lee KM, Ucmak D, Wong K, et al. Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health. J Transl Med. 2017;15:73. doi: 10.1186/s12967-017-1175-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfe AJ. Glycolysis for the microbiome generation. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3 10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0014-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Vergnolle Nathalie. Protease inhibition as new therapeutic strategy for GI diseases. Gut. 2016;65(7):1215–1224. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin R, Liu W, Piao M, Zhu H. A review of the relationship between the gut microbiota and amino acid metabolism. Amino Acids. 2017;49:2083–2090. doi: 10.1007/s00726-017-2493-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith EA, Macfarlane GT. Enumeration of amino acid fermenting bacteria in the human large intestine: effects of pH and starch on peptide metabolism and dissimilation of amino acids. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:355–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1998.tb00487.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geboes KP, De Hertogh G, De Preter V, Luypaerts A, Bammens B, Evenepoel P, et al. The influence of inulin on the absorption of nitrogen and the production of metabolites of protein fermentation in the colon. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:1078–1086. doi: 10.1017/BJN20061936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donohoe DR, Garge N, Zhang X, Sun W, O’Connell TM, Bunger MK, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian colon. Cell Metab. 2011;13:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falony G, Joossens M, Vieira-Silva S, Wang J, Darzi Y, Faust K, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science. 2016;352:560–564. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G, Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016;8:51. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macfarlane GT, Macfarlane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. J AOAC Int. 2012;95:50–60. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.SGE_Macfarlane. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mountfort DO, Grant WD, Clarke R, Asher RA. Eubacterium callanderi sp. nov. that demethoxylates O-methoxylated aromatic acids to volatile fatty acids. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1988;38:254–258. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald Julie A.K., Mullish Benjamin H., Pechlivanis Alexandros, Liu Zhigang, Brignardello Jerusa, Kao Dina, Holmes Elaine, Li Jia V., Clarke Thomas B., Thursz Mark R., Marchesi Julian R. Inhibiting Growth of Clostridioides difficile by Restoring Valerate, Produced by the Intestinal Microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1495-1507.e15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf PG, Biswas A, Morales SE, Greening C, Gaskins HR. H2 metabolism is widespread and diverse among human colonic microbes. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:235–245. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1182288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tailford LE, Crost EH, Kavanaugh D, Juge N. Mucin glycan foraging in the human gut microbiome. Front Genet. 2015;6:81. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Louis P, Flint HJ. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19:29–41. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischbach MA, Sonnenburg JL. Eating for two: how metabolism establishes interspecies interactions in the gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vladar HP. Amino acid fermentation at the origin of the genetic code. Biol Direct. 2012;7:6. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V, Gasbarrini A. Commensal clostridia: leading players in the maintenance of gut homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 2013;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokusaeva K, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Carbohydrate metabolism in Bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr. 2011;6:285–306. doi: 10.1007/s12263-010-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jumas-Bilak E, Carlier J-P, Jean-Pierre H, Teyssier C, Gay B, Campos J, et al. Veillonella montpellierensis sp. nov., a novel, anaerobic, gram-negative coccus isolated from human clinical samples. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1311–1316. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02952-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paixão L, Oliveira J, Veríssimo A, Vinga S, Lourenço EC, Ventura MR, et al. Host glycan sugar-specific pathways in Streptococcus pneumonia: galactose as a key sugar in colonisation and infection. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121042. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duncan SH, Hold GL, Harmsen HJM, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. Growth requirements and fermentation products of Fusobacterium prausnitzii, and a proposal to reclassify it as Faecalibacterium prausnitzii gen. Nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:2141–2146. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-6-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charalampopoulos D, Pandiella SS, Webb C. Growth studies of potentially probiotic lactic acid bacteria in cereal-based substrates. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:851–859. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taras D, Simmering R, Collins MD, Lawson PA, Blaut M. Reclassification of Eubacterium formicigenerans Holdeman and Moore 1974 as Dorea formicigenerans gen. nov., comb. nov., and description of Dorea longicatena sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:423–428. doi: 10.1099/00207713-52-2-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holdeman LV, Moore WEC. New genus, Coprococcus, twelve new species, and emended descriptions of four previously described species of bacteria from human feces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1974;24:260–277. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu C, Finegold SM, Song Y, Lawson PA. Reclassification of Clostridium coccoides, Ruminococcus hansenii, Ruminococcus hydrogenotrophicus, Ruminococcus luti, Ruminococcus productus and Ruminococcus schinkii as Blautia coccoides gen. Nov., comb. nov., Blautia hansenii comb. nov., Blautia hydrogenotrophica comb. nov., Blautia luti comb. nov., Blautia producta comb. nov., Blautia schinkii comb. nov. and description of Blautia wexlerae sp. nov., isolated from human faeces. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58:1896–1902. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65208-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roh H, Ko H-J, Kim D, Choi DG, Park S, Kim S, et al. Complete genome sequence of a carbon monoxide-utilizing Acetogen, Eubacterium limosum KIST612. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:307–308. doi: 10.1128/JB.01217-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Polansky O, Sekelova Z, Faldynova M, Sebkova A, Sisak F, Rychlik I. Important metabolic pathways and biological processes expressed by chicken cecal microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:1569–1576. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03473-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Reclassification of Bacteroides distasonis, Bacteroides goldsteinii and Bacteroides merdae as Parabacteroides distasonis gen. nov., comb. nov., Parabacteroides goldsteinii comb. nov. and Parabacteroides merdae comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:1599–1605. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rautio M, Eerola E, Väisänen-Tunkelrott M-L, Molitoris D, Lawson P, Collins MD, et al. Reclassification of Bacteroides putredinis (Weinberg et al., 1937) in a new genus Alistipes gen. nov., as Alistipes putredinis comb. nov., and description of Alistipes finegoldii sp. nov., from human sources. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2003;26:182–188. doi: 10.1078/072320203322346029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaneuchi C, Miyazato T, Shinjo T, Mitsuoka T. Taxonomic study of helically coiled, Sporeforming anaerobes isolated from the intestines of humans and other animals: Clostridium cocleatum sp. nov. and Clostridium spiroforme sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 1979;29:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yutin N, Galperin MY. A genomic update on clostridial phylogeny: gram-negative spore-formers and other misplaced clostridia. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:2631–2641. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang K, Shen CR. Selection of an endogenous 2,3-butanediol pathway in Escherichia coli by fermentative redox balance. Metab Eng. 2017;39:181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chassard C, Delmas E, Robert C, Lawson PA. Bernalier-Donadille a. Ruminococcus champanellensis sp. nov., a cellulose-degrading bacterium from human gut microbiota. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62:138–143. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.027375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mashima I, Liao Y-C, Miyakawa H, Theodorea CF, Thawboon B, Thaweboon S, et al. Veillonella infantium sp. nov., an anaerobic, gram-stain-negative coccus isolated from tongue biofilm of a Thai child. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:1101–1106. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Elshaghabee FMF, Bockelmann W, Meske D, de Vrese M, Walte H-G, Schrezenmeir J, et al. Ethanol production by selected intestinal microorganisms and lactic acid bacteria growing under different nutritional conditions. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:47. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kelly WJ, Henderson G, Pacheco DM, Li D, Reilly K, Naylor GE, et al. The complete genome sequence of Eubacterium limosum SA11, a metabolically versatile rumen acetogen. Stand Genomic Sci. 2016;11:26. doi: 10.1186/s40793-016-0147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrison DJ, Preston T. Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes. 2016;7:189–200. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud D-J, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ríos-Covián D, Ruas-Madiedo P, Margolles A, Gueimonde M. de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Salazar N. intestinal short chain fatty acids and their link with diet and human health. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:185. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee W-J, Hase K. Gut microbiota-generated metabolites in animal health and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:416–424. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nishina PM, Freedland RA. Effects of propionate on lipid biosynthesis in isolated rat hepatocytes. J Nutr. 1990;120:668–673. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.7.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chambers ES, Viardot A, Psichas A, Morrison DJ, Murphy KG, Zac-Varghese SEK, et al. Effects of targeted delivery of propionate to the human colon on appetite regulation, body weight maintenance and adiposity in overweight adults. Gut. 2015;64:1744–1754. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Layden BT, Yalamanchi SK, Wolever TM, Dunaif A, Lowe WL. Negative association of acetate with visceral adipose tissue and insulin levels. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2012;5:49–55. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S29244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dorokhov YL, Shindyapina AV, Sheshukova EV, Komarova TV. Metabolic methanol: molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:603–644. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gkolfakis P, Dimitriadis G, Triantafyllou K. Gut microbiota and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2015;14:572–581. doi: 10.1016/S1499-3872(15)60026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Brien PJ, Siraki AG, Shangari N. Aldehyde sources, metabolism, molecular toxicity mechanisms, and possible effects on human health. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005;35:609–662. doi: 10.1080/10408440591002183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhu L, Baker SS, Gill C, Liu W, Alkhouri R, Baker RD, et al. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology. 2013;57:601–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lane ER, Zisman TL, Suskind DL. The microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease: current and therapeutic insights. J Inflamm Res. 2017;10:63–73. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S116088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Principi M, Iannone A, Losurdo G, Mangia M, Shahini E, Albano F, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and risk factors. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:1589–1596. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hinnebusch BF, Meng S, Wu JT, Archer SY, Hodin RA. The effects of short-chain fatty acids on human colon cancer cell phenotype are associated with histone hyperacetylation. J Nutr. 2002;132:1012–1017. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miceli JF, Torres CI, Krajmalnik-Brown R. Shifting the balance of fermentation products between hydrogen and volatile fatty acids: microbial community structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2016;92:fiw195. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mack I, Cuntz U, Grämer C, Niedermaier S, Pohl C, Schwiertz A, et al. Weight gain in anorexia nervosa does not ameliorate the faecal microbiota, branched chain fatty acid profiles, and gastrointestinal complaints. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26752. doi: 10.1038/srep26752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Armougom F, Henry M, Vialettes B, Raccah D, Raoult D. Monitoring bacterial Community of Human gut Microbiota Reveals an increase in lactobacillus in obese patients and methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rey FE, Gonzalez MD, Cheng J, Wu M, Ahern PP, Gordon JI. Metabolic niche of a prominent sulfate-reducing human gut bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13582–13587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312524110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benjdia A, Martens EC, Gordon JI, Berteau O. Sulfatases and a radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) enzyme are key for mucosal foraging and fitness of the prominent human gut symbiont, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25973–25982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nicholls P, Kim JK. Sulphide as an inhibitor and electron donor for the cytochrome c oxidase system. Can J Biochem. 1982;60:613–623. doi: 10.1139/o82-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Figliuolo VR, dos Santos LM, Abalo A, Nanini H, Santos A, Brittes NM, et al. Sulfate-reducing bacteria stimulate gut immune responses and contribute to inflammation in experimental colitis. Life Sci. 2017;189:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ijssennagger N, Belzer C, Hooiveld GJ, Dekker J, van Mil SWC, Müller M, et al. Gut microbiota facilitates dietary heme-induced epithelial hyperproliferation by opening the mucus barrier in colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:10038–10043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507645112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ijssennagger N, van der MR, van MSWC. Sulfide as a mucus barrier-breaker in inflammatory bowel disease? Trends Mol Med. 2016;22:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Madsen L, Myrmel LS, Fjære E, Liaset B, Kristiansen K. Links between dietary protein sources, the gut microbiota, and obesity. Front Physiol. 2017;8:1047. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.01047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andriamihaja M, Davila A-M, Eklou-Lawson M, Petit N, Delpal S, Allek F, et al. Colon luminal content and epithelial cell morphology are markedly modified in rats fed with a high-protein diet. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G1030–G1037. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00149.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hughes Roisin, Kurth Mary Jo, McGilligan Victoria, McGlynn Hugh, Rowland Ian. Effect of Colonic Bacterial Metabolites on Caco-2 Cell Paracellular Permeability In Vitro. Nutrition and Cancer. 2008;60(2):259–266. doi: 10.1080/01635580701649644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cremin JD, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Glucose alleviates ammonia-induced inhibition of short-chain fatty acid metabolism in rat colonic epithelial cells. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G105–G114. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00437.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eklou-Lawson M, Bernard F, Neveux N, Chaumontet C, Bos C, Davila-Gay A-M, et al. Colonic luminal ammonia and portal blood l-glutamine and l-arginine concentrations: a possible link between colon mucosa and liver ureagenesis. Amino Acids. 2009;37:751–760. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mouillé B, Robert V, Blachier F. Adaptative increase of ornithine production and decrease of ammonia metabolism in rat colonocytes after hyperproteic diet ingestion. Am J Physiol-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G344–G351. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00445.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Smith EA, Macfarlane GT. Dissimilatory amino acid metabolism in human colonic bacteria. Anaerobe. 1997;3:327–337. doi: 10.1006/anae.1997.0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Heimann E, Nyman M, Pålbrink A-K, Lindkvist-Petersson K, Degerman E. Branched short-chain fatty acids modulate glucose and lipid metabolism in primary adipocytes. Adipocyte. 2016;5:359–368. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2016.1252011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jaskiewicz J, Zhao Y, Hawes JW, Shimomura Y, Crabb DW, Harris RA. Catabolism of isobutyrate by colonocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;327:265–270. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tangerman A. Measurement and biological significance of the volatile sulfur compounds hydrogen sulfide, methanethiol and dimethyl sulfide in various biological matrices. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:3366–3377. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Furne J, Springfield J, Koenig T, DeMaster E, Levitt MD. Oxidation of hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol to thiosulfate by rat tissues: a specialized function of the colonic mucosa. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62:255–259. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pugin B, Barcik W, Westermann P, Heider A, Wawrzyniak M, Hellings P, et al. A wide diversity of bacteria from the human gut produces and degrades biogenic amines. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2017;28:1353881. doi: 10.1080/16512235.2017.1353881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mayeur C, Veuillet G, Michaud M, Raul F, Blottière HM, Blachier F. Effects of agmatine accumulation in human colon carcinoma cells on polyamine metabolism, DNA synthesis and the cell cycle. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Mol Cell Res. 2005;1745:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nissim I, Horyn O, Daikhin Y, Chen P, Li C, Wehrli SL, et al. The molecular and metabolic influence of long term agmatine consumption. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:9710–9729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.544726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Auguet M, Viossat I, Marin JG, Chabrier PE. Selective inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase by agmatine. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1995;69:285–287. doi: 10.1254/jjp.69.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reis DJ, Regunathan S. Is agmatine a novel neurotransmitter in brain? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:187–193. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mouillé B, Delpal S, Mayeur C, Blachier F. Inhibition of human colon carcinoma cell growth by ammonia: a non-cytotoxic process associated with polyamine synthesis reduction. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA - Gen Subj. 2003;1624:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Büttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1305–1314. doi: 10.1038/ncb1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen J, Rao JN, Zou T, Liu L, Marasa BS, Xiao L, et al. Polyamines are required for expression of toll-like receptor 2 modulating intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G568–G576. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00201.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rao JN, Rathor N, Zhuang R, Zou T, Liu L, Xiao L, et al. Polyamines regulate intestinal epithelial restitution through TRPC1-mediated Ca2+ signaling by differentially modulating STIM1 and STIM2. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C308–C317. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00120.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Buts Jean-Paul, De Keyser Nadine, Kolanowski Jaroslaw, Sokal Etienne, Van Hoof Francois. Maturation of villus and crypt cell functions in rat small intestine. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 1993;38(6):1091–1098. doi: 10.1007/BF01295726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kibe R, Kurihara S, Sakai Y, Suzuki H, Ooga T, Sawaki E, et al. Upregulation of colonic luminal polyamines produced by intestinal microbiota delays senescence in mice. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4548. doi: 10.1038/srep04548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Haskó G, Kuhel DG, Marton A, Nemeth ZH, Deitch EA, Szabó C. Spermine differentially regulates the production of interleukin-12 p40 and interleukin-10 and suppresses the release of the T helper 1 cytokine interferon-gamma. Shock Augusta Ga. 2000;14:144–149. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]