Abstract

Over the past two decades, the molecular characterization of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) has been revolutionized by the routine implementation of RAS and BRAF tests. As a result, it is now known that patients with mCRC harboring BRAF mutations experience a poor prognosis. Although it accounts for only 10% of mCRC, this group is heterogeneous; only the BRAF-V600E mutation, also observed in melanoma, is associated with a very poor prognosis. In terms of treatment, these patients do not benefit from therapeutics targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). In first-line chemotherapy, there are two main options; the first one is to use a triple chemotherapy combination of 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin, with the addition of bevacizumab, because post hoc analysis of randomized trials have reported interesting results. The other option is to use double chemotherapy plus bevacizumab, since anti-EGFR seems to have modest activity in these patients. Only a small percentage of patients who experience failure of this first-line treatment receive second-line treatment. Monotherapy with BRAF inhibitors has failed in this setting, and different combinations have also been tested. Using the rationale that BRAF inhibitor monotherapy fails due to feedback activation of the EGFR pathway, BRAF inhibitors have been combined with anti-EGFR agents plus or minus MEK inhibitors; however, the results did not live up to the hopes raised by the concept. To date, the best results in second-line treatment have been obtained with a combination of vemurafenib, cetuximab, and irinotecan. Despite these advances, further improvements are needed.

Keywords: BRAF inhibitors, BRAF mutation, chemotherapy, colorectal cancer

Introduction

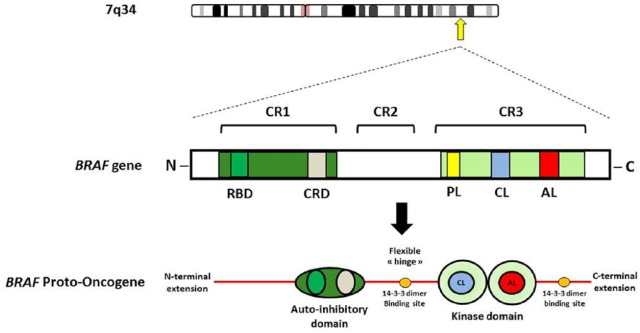

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains one of the main causes of cancer mortality around the world. Although global mortality is decreasing, an increased mortality in young adults (<50 years old) has been reported.1 Virus-induced rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (v-RAF) was first identified as an oncogene through the cloning of a viral mouse gene that had the ability to transform NIH3T3 cells. Its human ortholog CRAF (RAF-1) and subsequently the related kinase genes ARAF and BRAF were later found to be commonly mutated in cancer. This RAF kinase family consists of key components of the RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK signaling cascade (MAPK pathway; Figures 1 and 2). The BRAF (v-RAF murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B; B-type raf kinase) gene is located on chromosome 7. Like RAS, the serine/threonine-protein kinase BRAF is a downstream signaling protein in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-mediated pathway; in vitro experiences have highlighted that some genes are differently expressed in BRAF-mutant and wild-type CRC cell lines.2,3 A characteristic gene expression signature associated with BRAF mutation has been identified.4 However, attempts to directly inhibit the active BRAF protein failed in metastatic CRC (mCRC),5 suggesting a more complex (or at least different) carcinogenic process in this disease. Nevertheless, BRAF mutation testing is now recommended for mCRC in the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.6 We will discuss and review here the more recent literature that specifically concerns BRAF-mutant CRC.

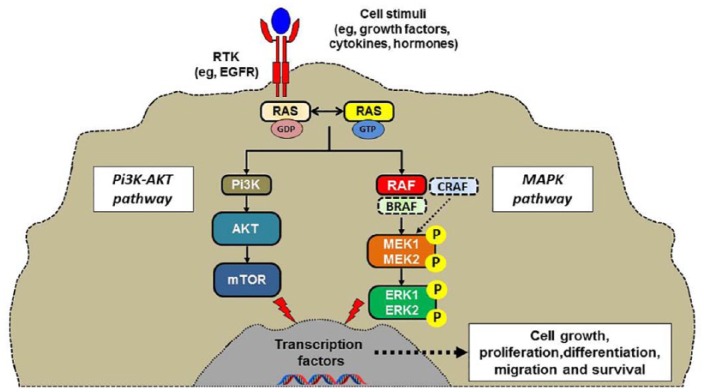

Figure 1.

The RAS–RAF–MEK–ERK cellular signaling cascade.

Figure 2.

BRAF schematic primary structure, showing functional domains.

AL, activation loop; CL, catalytic loop; CR, conserved region; CRD, cysteine-rich domain; KD, kinase domain; P-L, phosphate-binding loop; RBD, RAS-binding domain.

The BRAF pathway and the biological consequences of BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer carcinogenesis

The MAPK pathway plays a major role in homeostasis of cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival, and apoptosis. BRAF-mutant CRC typically harbors a valine to glutamic acid change at codon 600. As for the deleterious KRAS mutation such as G12, this alteration in the BRAF kinase domain results in a constitutively active protein. However, BRAF mutations in certain disease subtypes, such as hypermethylated right-sided CRC, suggest that additional tumor features and alterations are associated with the presence of BRAF-V600E and will determine the final signal output.7 Although the two genes work closely in the same pathway, the gene expression patterns of KRAS-mutant and BRAF-mutant mCRC are very different from each other.8 Furthermore, the oncogenic contribution of mutated BRAF may vary between tumor types, as suggested by the very heterogeneous clinical benefit provided by BRAF inhibition treatment strategies in melanoma and mCRC.5,9

It has been reported that BRAF, and especially V600E mutations lead to constitutive BRAF kinase phosphorylation of MEK and ERK kinases and sustained MAPK pathway signaling. As soon as the RAF kinases are activated, MEK1 and MEK2 are phosphorylated and activated, and as a consequence ERK1 and RK2 are phosphorylated and activated.10 This ERK activation produces phosphorylation of numerous substrates both in the nucleus and the cytosol, leading to an enhancement of cell proliferation and a longer survival. Despite numerous accessible crystal structures of wild-type BRAF and BRAF-V600E, the mechanism by which BRAF‑V600E mutants activate BRAF remains poorly understood. A study of 218 BRAF-V600E-mutated colorectal tumors demonstrated a clear heterogeneity within this group of tumors. This identified two distinct subgroups independent of microsatellite instability (MSI) status, PI3K mutation, sex, and sidedness.11 A subset of tumors was characterized by high KRAS/mTOR/AKT/4EBP1/EMT activation, while cell-cycle dysregulation characterized the other. These different subgroups of BRAF-V600E mutations may explain the nonuniform responses to drug therapies, including BRAF and MEK inhibitors. Considering the difficulty of developing specific BRAF inhibitors, it is clear that the specific structural mechanism of different BRAF mutations still requires further study.

Epidemiology

BRAF mutations are present in 5–15% of CRC, with a higher mutation rate in right-sided colon cancer.12,13 In a report comprising 2530 patients with mCRC included in three randomized trials (COIN, FOCUS, and PICCOLO), the prevalence of BRAF mutations was 9.1%.14 In a population-based study that could better reflect the true incidence, 12% of the patients had BRAF-V600E mutant tumors.15 In another population-based report the percentage of BRAF-mutant tumors was even superior to 20%.16 Dual mutations of RAF and RAS genes are rarely seen: 8 among the 2530 patients (0.3%) and 0.01% of cases in another series.17 There are more BRAF mutations in right-sided colon cancer than in left-sided colon cancer. For instance, the SPECTAcolor trial revealed that the percentage of BRAF-mutant tumors was 10.5% in the total population of 370 patients, and was 22.6% in patients with right-sided colon cancer versus only 5.1% in patients left-sided colon cancer.17 In a large pooled biomarker analysis evaluating the role of biological markers in defining the prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM classification, a stepwise decrease in the prevalence of KRAS or BRAF-V600E mutations was observed when moving from right-sided to left-sided colon cancer. BRAF mutations (and KRAS) were approximately twice as likely to be found in the caecum than the sigmoid colon.18

BRAF-mutant tumors: clinical and histopathological specificity

Patients with BRAF-mutant CRC are more likely than those with wild-type CRC to be female, have right-sided tumors, or have peritoneal or nodal metastases, but are less likely to have lung metastases. In addition, their tumors more frequently have mucinous histology.19 The signet ring cell phenotype also seems to be more frequently observed but this could be related to the MSI status also observed in these patients.20 Classically, BRAF mutations are common in sessile serrated adenomas and seem to appear first in this kind of adenomas.21 In these neoplasms, BRAF mutations are associated with MSI, hypermethylation, and minimal chromosomal instability.22 The association between BRAF mutation and MSI in CRC could be related to the relationship with the high-level CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) and MLH1 promoter methylation. It has also been suggested that there is an association between current or former smoking history and the presence of BRAF-V600E mutations in tumors that could be also related to the CIMP phenotype.23,24 Although the exact mechanism remains unknown, preclinical studies have shown that tobacco exposure can stimulate the DNA methyltransferase activity that is associated with CIMP.25

The patterns of BRAF-mutant tumors have been shown to be so specific that a nomogram for predicting mutational status of mCRC has been published.26 A predictive score was assigned to each of the following variables: the primary site of the tumor, the patient’s sex, and the mucinous characteristics of the cancer. The sum of the scores was converted to the probability of BRAF mutation occurrence, and was 81% in female patients with mucinous-type right-sided colon cancer.

BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer and microsatellite instability

BRAF mutations are observed in 40–60% of the sporadic CRC harboring high MSI (MSI-high); in contrast, BRAF mutations are never seen in patients with Lynch syndrome.27 In a metastatic setting, BRAF-mutant tumors were more likely to have MSI than wild-type tumors (12.6% versus 3.0%, p < 0.001).14 In a pooled analysis on localized colon cancer,28 the prevalence of BRAF-V600E mutations and MSI status paralleled each other, with an increase from the caecum to the hepatic flexure, then a gradual decrease through the sigmoid colon. BRAF-V600E mutations were eight times more prevalent in MSI-high than microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors. In all published series, there is an overlap between MSI and BRAF-V600E tumors, with a major impact on prognosis (see below). Hence, MSI status should always be included in studies that address BRAF mutation status.29

Impact of BRAF mutations on prognosis

Impact of BRAF mutations on prognosis in an adjuvant setting

A retrospective, pooled biomarker study evaluated 4411 tumors for BRAF and KRAS mutations and mismatch repair status; 3934 were MSS and 477 were MSI. In MSS patients, all BRAF-V600E mutations [hazard ratio (HR): 1.54; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.23–1.92, p < 0.001)], KRAS codon 12 alterations, and p.G13D mutations (HR: 1.60; 95% CI: 1.40–1.83, p < 0.001) were associated with shorter time to recurrence and shorter survival after relapse (HR: 3.02; 95% CI: 2.32–3.93, p < 0.001, and HR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.01–1.44, p = 0.04, respectively). Overall survival (OS) in MSS patients was poorer for patients with BRAF-mutant tumors (HR 2.01, 95% CI 1.56–2.57). In the pooled analysis of stage II and III colon cancers, the HR of median OS between BRAF-V600E-mutated and nonmutated tumors was around 2,28 confirming the prognostic role of the BRAF-V600E mutation in an adjuvant setting. There is a relationship between BRAF-V600E mutation and the classification of primary colorectal cancer according to the gene-expression-based consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) that has defined four molecularly and clinically distinct subgroups of tumors.30 In a large Norwegian series of 1197 colorectal cancer (all stages) it was reported that BRAF-V600E mutations are enriched and associated with poor prognosis in CMS1 (immune type) MSS tumors.31

Impact of BRAF mutations on prognosis in metastatic disease

The mechanism resulting to the poor prognosis of patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC is poorly understood. It was rapidly shown that with standard treatment including targeted therapies, the median OS of these patients was around 12 months, much lower than that obtained in BRAF-wild-type patients.32,33 In terms of progression-free survival (PFS), there was no major difference in first-line treatment. However, following progression on first-line chemotherapy, patients with BRAF-mutant CRC had a significantly shorter post-progression survival, and only one-third of patients were able to receive second-line treatment versus more than 50% in patients with BRAF-wild-type mCRC.14 In a study evaluating 5FU/folinic acid/irinotecan (FOLFIRI) plus panitumumab in a pure second-line setting, patients with BRAF-mutant mCRC had a median PFS of 2.5 months and an OS of 4.7 months, compared with a PFS and an OS of 6.9 and 18.7 months, respectively, in patients with BRAF-wild-type tumors.34

In contrast, BRAF mutation did not change the prognosis of patients with MSI-high tumors: in a Finnish population-based series of 762 patients with sporadic CRC, the poor prognostic effect caused by BRAF-V600E mutation (multivariate analysis of 1.88, n = 34) was overpowered by the favorable effect of MSI in the MSI/BRAF-V600E population (HR: 0.83, 60 patients).15 The same series showed that patients with sporadic MSS/BRAF-V600E-mutated rectal tumors had a very poor prognosis.15 Exceptional cases of double mutations are also associated with a very poor prognosis.17

Are all BRAF mutations the same?

As stated previously, the mutation typically observed in CRC is a V600E mutation; this mutation has been described in up to 7% of human cancers and can be present in different tumor types, such as melanoma (66% of cases),7 thyroid cancer (60%),7 and lung cancers (9%).35 The V600E mutation accounts for approximately 95% of the activating mutations in BRAF in mCRC.5

Although V600E has an adverse impact on prognosis, other rarer BRAF mutations do not seem to share the same effect.36 A total of 10 patients with tumors bearing mutations in BRAF codons 594 or 596 were identified and compared with 77 and 542 patients bearing BRAF-V600E-mutant and BRAF-wild-type tumors, respectively. While BRAF-V600E-mutant tumors were more frequently right-sided, mucinous, and with peritoneal spread, BRAF 594 or 596 mutant tumors were more frequently rectal, nonmucinous and with no peritoneal spread. The 10 tumors with BRAF 594 or 596 mutations were MSS. Patients with tumors bearing mutations in BRAF codons 594 or 596 had an OS (62 months) that appears even better than those of BRAF-wild-type tumors, and clearly different from those with BRAF-V600E-mutant tumors (12.6 months; HR: 0.36; 95% CI: 0.20–0.64, p = 0.002).36 In a sample of patients from the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center with mCRC who had next-generation sequencing performed on their tumor specimens, non-V600E mutations made up approximately 20% of all BRAF-mutant tumors. These tumors appear sensitive to EGFR inhibitors.37 These data have been confirmed by more recent studies: in a total of 9643 patients with mCRC analyzed with next-generation sequencing 208 (2.2%) patients with (non-V600) BRAF mutations were identified (22% of all BRAF mutations identified).38 When compared with tumors with BRAF-V600E mutations cancers with (non-V600) BRAF mutations were found in patients who were significantly younger (58 versus 68 years, respectively), who were less frequently female patients (46% versus 65%, respectively), and who had fewer high-grade tumors (13% versus 64%, respectively) or right-sided primary tumors (36% versus 81%, respectively). Median OS was significantly longer in patients with (non-V600) BRAF-mutant metastatic CRC compared with those with both (V600E) BRAF-mutant and wild-type BRAF metastatic CRC (60.7 versus 11.4 versus 43.0 months, respectively; p < 0.001). There is heterogeneity even within BRAF-V600E-mutant tumors, and a prognostic score has been built using data from 395 patients. The global score took into account 18 variables; a simplified score restricted to 11 variables has been proposed.39 Both scores require validation in another series of patients.

Treatment of BRAF-mutant tumors

First-line treatment

BRAF mutation and efficacy of anti-EGFR

While data suggest that BRAF mutation status has clear prognostic value in mCRC, the predictive value of BRAF mutation status for response and benefit from EGFR-directed treatments, such as cetuximab, remains controversial. Retrospective analyses of recent trials have suggested that BRAF mutations are not predictive of outcome with EGFR-directed therapies,40–42 whereas other analyses have suggested that cetuximab and panitumumab are more active in patients with BRAF-wild-type mCRC.43,44 A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials evaluated the effect of BRAF mutations on the treatment benefit from anti-EGFR therapy for mCRC.45 The HR for an OS benefit with anti-EGFR treatment was 0.97 (95% CI: 0.67–1.41) for mutant tumors compared with 0.81 (95% CI: 0.70–0.95) for BRAF-wild-type tumors (RAS wild-type). However, the test of interaction was not statistically significant. The HR for a PFS benefit with anti-EGFR therapy was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.61–1.21) for BRAF-mutant tumors compared with 0.62 (95% CI: 0.50–0.77) for BRAF-wild-type tumors (test of interaction, p = 0.07). The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence to state that anti-EGFR therapy has no effect in BRAF-mutant tumors.45 Another meta-analysis, published the same year, did not show any benefit in favor of the use of cetuximab or panitumumab in BRAF-mutant tumors (HR for OS: 0.91, NS).46 It seems at least that the effect is small; for example, the FIRE3 study reported a low median OS of 12.3 months in patients with BRAF-mutant tumors who received FOLFIRI + cetuximab as first-line treatment.47

BRAF mutation and efficacy of bevacizumab

In the first study reporting major efficacy of bevacizumab,48 median OS was 16 months when patients with a BRAF-mutant tumor received bevacizumab versus 8 months when they received chemotherapy alone. However, the number of patients included in this post hoc analysis was very small (10 patients).49 In the VELOUR study,50 30 patients had BRAF-mutant tumors; among them, 11 patients receiving aflibercept and FOLFIRI had a median OS of 11 versus 5 months in the 19 patients receiving only chemotherapy.51 The FIRE3 study, comparing FOLFIRI + bevacizumab or cetuximab, included 48 patients with BRAF-mutant tumors.47 Median PFS was 4.9 months in the patient group receiving cetuximab and 6.0 months in the group of patients receiving bevacizumab (HR: 0.87, NS). Median OS also showed a small nonsignificant advantage in favor of FOLFIRI + bevacizumab (13.7 versus 12.3 months). The large United States (US) trial comparing bevacizumab with cetuximab in the first-line treatment of mCRC reported a better median OS for patients with BRAF-mutant tumors treated with bevacizumab (median = 15 months in 41 patients) than in patients treated with cetuximab (median = 11.7 months in 31 patients), but this difference did not reach significance (adjusted HR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.35–1.06).52

FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab as first-line treatment of BRAF-mutant tumors: a standard of care?

Despite a lack of evidence to back up the interest in the use of bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy, the most interesting data obtained to date in BRAF-mutant mCRC resulted from a combination of triplet chemotherapy with bevacizumab. Following the results of the first large phase III trial of the GONO group, it has been known for 10 years that triplet chemotherapy with 5FU, folinic acid, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOXIRI) was able to improve efficacy to FOLFIRI in an all-comers patient population.53 The same group evaluated the role of this combination plus bevacizumab. They reported a very good response rate (90%), median PFS (12.8 months), and OS (30.9 months) in a subgroup of 10 patients with BRAF-mutant tumors treated with FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab (post hoc analysis).54 A prospective study performed in 214 patients that included 15 with BRAF-mutant tumors confirmed these results, finding a median PFS and OS of 9.2 and 24.1 months, respectively.55 When retrospective and prospective results were pooled, median PFS and OS were 11.8 and 24.1 months, respectively.55 These data have been confirmed by a subgroup analysis of the TRIBE trial, which showed that the 16 patients with BRAF-mutant tumors treated with FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab in this randomized trial had a median OS of 19.0 months, whereas the 12 patients treated with FOLFIRI + bevacizumab had a shorter median OS of 10.7 months.56 Following these results the consensus European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)-Asian guidelines recommended triplet chemotherapy plus bevacizumab as the standard of care for first-line treatment of BRAF-mutant CRC.57

More recently, a phase II randomized trial showed that addition of panitumumab to the same FOLFOXIRI combination gave an advantage, even in patients with BRAF mutations, in terms of response rate: 71% versus 22% when compared with chemotherapy. However, there was no difference in median PFS (6.5 and 6.1 months with and without panitumumab, respectively).58

On the other hand, due to the weak level of evidence, it can be also suggested another option using FOLFOX bevacizumab in the first line followed by an active second-line combination of irinotecan + cetuximab + vemurafenib recently presented59 that we will discuss later.

Treatment of BRAF-mutant tumors after failure of first-line therapy

Table 1 shows the targeted therapies and treatment of BRAF-mutant mCRC. Surprisingly, it has been reported that although fewer patients with BRAF-mutant tumors receive second-line treatment, BRAF mutation is not associated with inferior second-line outcomes.14 The first attempt to treat BRAF-mutant mCRC used the evident potential resource that was BRAF inhibitors, which had proved to be very effective in the treatment of BRAF-V600E-mutant melanoma.9

Table 1.

Targeted therapies and treatment of BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer.

| Reference | Patients, n

(type of study) |

Treatment | ORR (%) |

PFS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAF inhibitor monotherapy | ||||

| Kopetz and colleagues5 | 21 (phase II) |

Vemurafenib | 5 | 2.1 |

| RAF inhibitor + MEK inhibitor combination therapy | ||||

| Long and colleagues60 | 43 (phase I/II) |

Dabrafenib + trametinib | 12 (one CR) | 3.5 |

| RAF inhibitor + anti-EGFR combination therapy | ||||

| Kopetz and colleagues59 | 27 (phase I/II) |

Vemurafenib + cetuximab | 23 | 3.7 |

| Das Thakur and Stuart61 | 15 (phase I/II) |

Vemurafenib + panitumumab | 13 | 3.2 |

| Prahallad and colleagues62 | 20 (phase I/II) |

Dabrafenib + panitumumab | 10 | 3.5 |

| Corcoran and colleagues63 | 26 (phase Ib) |

Encorafenib + cetuximab | 19 (one CR) | 3.7 |

| Schirripa and colleagues64 | 50 (phase II) |

Encorafenib + cetuximab | 22 | 4.2 |

| MEK inhibitor + anti-EGFR combination therapy | ||||

| Prahallad and colleagues62 | 31 | Trametinib + panitumumab | 0 | 2.6 |

| Triple combination therapy | ||||

| Prahallad and colleagues62 | 91 | Dabrafenib + trametinib + panitumumab | 21 (one CR) | 4.2 |

| van Geel and colleagues65 | 54 (Randomized phase II) |

Vemurafenib+ irinotecan + cetuximab | 16 | 4.4 |

| Schirripa and colleagues64 | 52 (phase II) |

Encorafenib + cetuximab + alpelisib | 27 | 5.4 |

CR, complete response; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ORR, objective response rate; PFS, progression-free survival.

BRAF mutation and efficacy of RAF inhibitors

There are many different BRAF inhibitors.66 Only one compound in the first generation of BRAF inhibitors has obtained approval for the treatment of cancer. This compound, sorafenib, has been tested in the treatment of KRAS-mutant CRC in combination with irinotecan67 but not in BRAF-mutant mCRC. The main representatives of the second generation of BRAF-specific inhibitors are vemurafenib, dabrafenib, and encorafenib. Vemurafenib was initially tested as a single agent in a total of 21 BRAF-mutant mCRC patients, 19 of whom were evaluable for response. Among these 19 patients, there was only 1 partial response (5%) and the median PFS was 3.7 months.5 These results were confirmed when no objective response occurred in a basket study evaluating vemurafenib alone in 10 patients.68 Encorafenib is active in naïve and pretreated melanoma, suggesting that this drug could be effective in mCRC.69 The third generation of BRAF inhibitors has been developed to fight against the two main mechanisms of resistance that have been described.70 It means that some of these compounds will be effective and equipotent inhibitors of dimeric forms, as well as monomeric forms of BRAF and that the other type of third-generation BRAF inhibitors, acting as pan-RAF inhibitors, will not induce RAF paradoxical activation.71

However, even if monotherapy using new generation BRAF inhibitors could produce better results, it seems that combination regimens are likely to work better than monotherapy in these aggressive tumors in which complex signaling pathways are active.

Combination of targeted therapies

Double combinations

There is convincing nonclinical evidence that robust inhibition of MAPK signaling is needed to more effectively treat BRAF-mutant tumors.72,60 Cancer cells with BRAF mutations are highly dependent on MEK/ERK signaling. As demonstrated in melanoma cells, MEK-dependent activation of MAPK signaling occurs following BRAF inhibition and near-complete inhibition of phospho-ERK is required for tumor responses.73 The combination of a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor has been shown to be more active than either agent alone, presumably due to delay or prevention of resistance.61 In a larger study, a total of 43 patients with BRAF-V600E-mutant mCRC were treated with dabrafenib (a BRAF inhibitor) plus trametinib (a MEK inhibitor); 17 of them were enrolled onto a pharmacodynamic cohort undergoing mandatory biopsies before and during treatment. Of 43 patients, 5 (12%) achieved a partial response or better, including 1 (2%) complete response, with a duration of response greater than 3 years; 24 patients (56%) achieved stable disease as best confirmed response. All nine evaluable during-treatment biopsies had reduced levels of phosphorylated ERK relative to pretreatment biopsies.63

On the other hand, nonclinical work in CRC cells has shown that BRAF inhibition causes a rapid feedback activation of EGFR that supports continued proliferation of BRAF-V600E-mutant tumor cells.73,62 These reports suggest that activation of EGFR may partially explain the limited therapeutic effect of BRAF inhibitor monotherapy in patients with BRAF-V600E-mutant mCRC and that this could be overcome with concomitant EGFR inhibition. However, in the VE-BASKET study, the combination of vemurafenib and cetuximab did not substantially improve the efficacy: there was an objective response rate of 15% in 26 patients.68 Similarly, when vemurafenib was combined with panitumumab in 15 patients, of whom 12 were evaluable for response; partial responses were observed only in 2 (13%) patients.74 Encorafenib has been combined with cetuximab and gave a 19% objective response rate in 26 patients.65

Triple combinations

Targeting both potential mechanisms of resistance to BRAF inhibitors requires evaluation of the efficacy of triple combinations of a BRAF inhibitor, a MEK inhibitor, and an EGFR inhibitor. A clinical trial that evaluated the combination of dabrafenib, trametinib, and panitumumab in 91 patients reported confirmed complete and partial response in 19 patients (21%) and stable disease in 59 (65%; disease growth control: 86%).75 Despite these results, it was considered that the proof of concept of the activity of this quite toxic and very expensive triplet combination schedule was not obtained; development of this combination in this indication of BRAF-mutant tumors was abandoned. It has also been suggested that PI3K pathway activation could explain resistance to RAF inhibitors in BRAF-mutant mCRC. Thus, in parallel with the evaluation of the encorafenib and cetuximab combination already discussed, a triple combination with the addition of alpelisib, a PI3K-alpha inhibitor, has been tested.65 The objective response rate observed in this phase I study was similar to that with the double combination: 18%. The duration of response was short at 12 weeks, but median PFS was 4.2 months, slightly higher than in the double combination group. Although it does not appear that this triple combination is highly effective, it will be evaluated further.

In another phase Ib/II study that included 19 patients with BRAF-V600E mutant tumors, vemurafenib, at doses of 480 mg, 720 mg, and 960 mg twice daily, was combined with panitumumab and irinotecan. Of 17 response-evaluable patients, responses were observed in 6 (35%) patients with a median duration of response of 8.8 months and median PFS of 7.7 months. The most common adverse events observed included fatigue (89%), diarrhea (84%), rash (74%), nausea (74%), anemia (74%), and myalgia (53%).76 A recently reported randomized phase II study provides additional data.59 Patients with BRAF-V600E mutant tumors were randomized to receive either vemurafenib, irinotecan, and cetuximab every 2 weeks or irinotecan and cetuximab alone. The study included 106 patients and had PFS as its main endpoint. The median PFS was 4.4 months in the patient group receiving the triple combination with vemurafenib versus 2.0 months in the patient group treated with the standard doublet alone.59 A large phase III trial that only includes patients with BRAF-V600E mutant tumors has been launched; this trial aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination of encorafenib (a BRAF inhibitor) plus binimetinib (a MEK inhibitor) given with the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab in patients with BRAF-V600E-mutant mCRC after one or two prior regimens (BEACON CRC trial). The first safety analysis of this phase III trial has been recently reported.77 First efficacy results will probably be presented in 2019.

Other options

Data from in vitro experiments suggested that patients with BRAF mutations may have sensitivity to microtubule inhibitors such as vinorelbine.78 RANBP2 (also known as NUP358) is a small GTP-binding protein belonging to the RAS superfamily that is a crucial regulator of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Suppression of RANBP2 results in mitotic defects only in BRAF-like CRC cells, leading to cell death. RANBP2 silencing reduces microtubule outgrowth from the kinetochores, thereby inducing spindle perturbations, providing an explanation for the observed mitotic defects. Thus, BRAF-like CRC cells had greater sensitivity to the microtubule poison vinorelbine both in vitro and in vivo, which suggested that this drug could be an effective treatment for BRAF-mutant CRC. Unfortunately, clinical prospective studies did not confirm these preliminary data: a small prospective series of 20 patients reported no objective response, a median PFS of 1 month, and a median OS of 2.1 months.79

Toxicity of BRAF inhibitors: a major concern?

Despite the poor prognosis of this patient population, the toxicity profile of drugs must be considered. Common adverse events associated with dabrafenib and vemurafenib include skin toxicities, arthralgia, fatigue, headache, pyrexia, and gastrointestinal events.80 The incidence of major side effects is not significantly different between dabrafenib and vemurafenib; however, photosensitivity and worsening of liver function tests have been more frequently associated with vemurafenib81 while pyrexia has been more frequently observed with dabrafenib.82 The most common skin toxicities associated with BRAF inhibitors have included rash, alopecia, dry skin, hyperkeratosis, pruritus, photosensitivity, hand–foot syndrome. Furthermore, promotion of both benign and malignant hyperproliferative squamous cutaneous lesions has been reported in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors.83 An increase in the incidence of secondary primary melanoma has also been suggested.84

Other events associated with vemurafenib have included QT interval prolongation and worsening liver function test results. QT interval prolongation with vemurafenib is considered rare, liver function abnormalities are usually asymptomatic, but liver injury leading to functional impairment has been reported.81 Preliminary data suggest also that patients treated with BRAF inhibitors for long periods of time have an increased risk of developing hyperplastic gastric polyps and colonic adenomatous polyps.85

BRAF mutations in MSI-high patients: a completely different therapeutic challenge

In the first report on the efficacy of pembrolizumab in MSI-high patients, only one patient had a BRAF-mutant tumor,86 preventing any specific conclusion about the efficacy of the programmed cell death (PD)-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor; however, subsequent studies included more MSI-high patients and analyzed their overall results according to their BRAF status. A study evaluating the role of nivolumab monotherapy in 74 MSI-high patients reported a response rate of 25% in the 12 patients with BRAF-mutant tumors, 27% in the 26 patients with KRAS-mutant tumors, and 41% in the 29 patients with both BRAF- and KRAS-wild-type tumors;87 there was no statistically significant difference in disease control rate (75, 62, and 78%, respectively). A combination of nivolumab + ipilimumab gave similar results without any influence of BRAF mutations on efficacy parameters in MSI-high patients: a 55% objective response rate and 79% disease control rate in 29 patients with BRAF-mutant tumors, and a 55% objective response rate and 80% disease control rate in the total population of 119 patients.88 It can therefore be concluded that in the population of MSI-high patients, BRAF mutation status does not have any predictive value in determining the efficacy of PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. All these patients share the same standard of care incorporating immunotherapy into their treatment.

BRAF mutations detected with circulating tumor DNA

In mCRC, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis could help to determine a subgroup of patients who have BRAF-mutant tumors but are classified as BRAF wild-type. This false statement can be due to a missed detection in the tumor due to spatial heterogeneity (or therapeutic pressure, that is, temporal heterogeneity). In one study, many more mutations were found by ctDNA analysis than tumor-tissue analysis: 59%, 11.8%, and 14.4% of patients were found to have KRAS-, NRAS- and BRAF-mutant tumors, respectively, by ctDNA analysis compared with 44%, 8.8%, and 7.2% by tumor-tissue analysis.89 In addition, it has been demonstrated that ctDNA has a higher sensitivity than the lactate dehydrogenase test to detect disease progression, including non-RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) progression events in melanoma patients.90 However, there are no data available in patients with mCRC.

Is it possible to propose the same locoregional strategy in patients with BRAF-mutant than in patients with BRAF-wild-type tumors?

The first study of surgery for patients with liver metastases secondary to BRAF-mutant tumors suggested that the risk of appearance of liver metastases is higher in these patients and that OS is poorer after liver resection of their metastases.91 Schirripa and colleagues confirmed this report, demonstrating in a series of 309 patients undergoing liver resection with tumors biologically assessed for RAS and BRAF mutations that patients with BRAF-mutant tumors (n = 12) had a shorter recurrence-free survival: 5.7 months, versus 11.0 and 14.4 months for RAS-mutant (n = 160) and RAS-wild-type (n = 137), respectively.64 The same group reported that after response to FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab, resected patients shared the same prognosis, with a median disease-free survival of 11–12 months independent of their BRAF status.92 However, this retrospective study included only seven patients with BRAF-mutant tumors.

Recent cohorts have given slightly discordant results. In a French cohort,93 66 patients underwent resection for BRAF-mutant liver metastases of mCRC. A case-matched comparison was made with 183 patients who underwent resection for BRAF-wild-type liver metastases of mCRC during the same period. The 1- and 3-year disease-free survival rates were respectively 46% and 19% in BRAF-mutant and 55% and 28% in BRAF-wild-type patients (p = 0.430). However, the 1- and 3-year OS rates after surgery were 93% and 54% in BRAF-mutant and 96% and 83% in BRAF-wild-type patients (p = 0.004). The median survival after disease progression was shorter in patients with BRAF-mutant tumors.

In a large US cohort including 1497 patients who had complete resection and a known BRAF status, 35 (2%) patients had BRAF-mutant tumors; of these, 71% had the V600E mutation. Compared with patients with BRAF-wild-type tumors, patients with BRAF-mutant tumors were older and appeared to have more advanced disease in the liver (more major hepatectomies, for instance) but less extrahepatic disease. Median OS was 81 months for patients with BRAF-wild-type tumors and 40 months for patients with BRAF-mutant tumors (p < 0.001). Median recurrence-free survival was 22 and 10 months for patients with BRAF-wild-type and BRAF-mutant tumors, respectively (p < 0.001). However, long-term survival was possible; it was associated with node-negative primary tumors, CEA ⩽ 200 µg/l, and a clinical risk score < 4.94 A multivariate analysis of a smaller cohort of 849 patients, including 43 (5%) patients with BRAF-mutant tumors, revealed that the presence of a BRAF-V600E mutation but not a non-BRAF-V600E mutation was associated with significantly poorer OS.95 As a conclusion, these data show that results of liver surgery are poorer in patients with BRAF-V600E tumors but that this is still the only hope of cure for these patients. However, considering the aggressiveness of BRAF mutation, it can be stated that surgery has to been done as soon as possible when a therapeutic response allowing resection with a hope of cure is reached.

For the future

BRAF-V600E mutant mCRC are insensitive to RAF inhibitor monotherapy due to the feedback reactivation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Combined RAF and EGFR inhibition exerts a therapeutic effect, but resistance invariably develops through undefined mechanisms. As stated previously, currently approved RAF inhibitors inhibit RAF monomers but not dimers. Mechanisms of resistance converge on the formation of RAF dimers, and inhibition of EGFR and RAF dimers could effectively suppress ERK-driven growth of resistant CRC in the future.96 If their activity is confirmed in clinical trials, third-generation RAF inhibitors that have been selected to have this kind of effect should gain market approval in the future. Pan-RAF inhibitors currently undergoing evaluation are also interesting, because they have been synthesized to be ‘paradox breakers’, by not inducing RAF paradoxical activation.

Conclusion

Patients with BRAF-V600E-mutant mCRC clearly have a poor prognosis and constitute a specific group, making up around at least 10% of all patients with mCRC. FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab is a possible option; however, the level of evidence-based medicine of this approach remains low. The role of the addition of anti-EGFR to FOLFOXIRI is not yet determined. Beyond the first line, despite the failure of RAF inhibitor monotherapy, some second-line treatments, such as the combination of vemurafenib, irinotecan, and cetuximab, have shown activity. Thus, a sequential use of FOLFOX bevacizumab followed by irinotecan, vemurafenib, and cetuximab is the other valid option. The rapid acquisition of resistance, either due to dimerization problems, or to the activation of parallel pathways, needs to be addressed to improve the efficacy of RAF inhibitors. The third generation of RAF inhibitors is under investigation and could revolutionize the landscape of mCRC management. Surgery with curative intent is less potent in the treatment of these tumors than in BRAF-wild-type tumors, but remains useful and should be proposed as soon as possible after a response to first-line therapy is seen. The challenge of treating MSI-high patients with BRAF mutations is completely different, because they respond to immunotherapy in the same way as patients with BRAF-wild-type tumors. New drugs, new combinations, and new targets are urgently required in this disease.

Acknowledgments

The manuscript has been revised in English by an independent scientific language editing service (Angloscribe).

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare the following conflicts of interest:

MD: Personal fees: MSD, Merck Serono, Roche, Bayer, Ipsen, Lilly, Servier, AMGEN, HalioDX, Sanofi; Travel, accommodation, expenses: Roche, MSD, AMGEN.

AC: Personal fees: AMGEN

PLP: Travel accommodation, expenses: Roche, MSD.

CS: None.

AEH: Personal fees: Merck Serono, AMGEN, Gribstone Oncology;

Travel, accommodation, expenses: AMGEN, SERVIER.

PD: None.

ES: Personal fees: Sanofi, Bayer, Servier, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, AMGEN, Merck.

VB: Personal fees: Bayer, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi, Ipsen;

Travel, accommodation: Bayer, Merck Serono, Roche.

DM: Personal fees: AMGEN, Bayer, Merck, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Shire, HalioDx, Agios.

Nonfinancial support: AMGEN, Bayer, Merck, Merck Serono, Roche, Sanofi, Servier.

MG: None.

ORCID iD: Ali Chamseddine  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5701-4268

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5701-4268

Contributor Information

Michel Ducreux, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Université Paris-Saclay, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, 114 rue Edouard Vaillant, Villejuif Cedex, 94805, France.

Ali Chamseddine, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

Pierre Laurent-Puig, Département de Biologie, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris, France; Université Paris-Descartes, Paris, France; INSERM UMRS-1147, Paris, France.

Cristina Smolenschi, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

Antoine Hollebecque, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France; Département d’Innovation Thérapeutique et des Essais Précoces (DITEP), Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

Peggy Dartigues, Département de Biopathologie, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

Emmanuelle Samallin, Département d’Oncologie Digestive, Institut régional du Cancer de Montpellier (ICM), Montpellier, France.

Valérie Boige, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

David Malka, Département d’Oncologie Médicale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

Maximiliano Gelli, Département de Chirurgie Viscérale, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus Grand Paris, Villejuif, France.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 177–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oikonomou E, Makrodouli E, Evagelidou M, et al. BRAF(V600E) efficient transformation and induction of microsatellite instability versus KRAS(G12V) induction of senescence markers in human colon cancer cells. Neoplasia 2009; 11: 1116–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Joyce T, Oikonomou E, Kosmidou V, et al. A molecular signature for oncogenic BRAF in human colon cancer cells is revealed by microarray analysis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 2012; 12: 873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Popovici V, Budinska E, Tejpar S, et al. Identification of a poor-prognosis BRAF-mutant-like population of patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kopetz S, Desai J, Chan E, et al. Phase II Pilot study of vemurafenib in patients with metastatic BRAF-Mutated colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 4032–4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benson AB, III, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: colon cancer, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16: 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002; 417: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tian S, Simon I, Moreno V, et al. A combined oncogenic pathway signature of BRAF, KRAS and PI3KCA mutation improves colorectal cancer classification and cetuximab treatment prediction. Gut 2013; 62: 540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 809–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dhillon AS, Hagan S, Rath O, et al. MAP kinase signalling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007; 26: 3279–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barras D, Missiaglia E, Wirapati P, et al. BRAF V600E mutant colorectal cancer subtypes based on gene expression. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features. Histopathology 2007; 50: 113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiu JW, Krzyzanowska MK, Serra S, et al. Molecular profiling of patients with advanced colorectal cancer: Princess Margaret Cancer Centre experience. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2018; 17: 73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seligmann JF, Fisher D, Smith CG, et al. Investigating the poor outcomes of BRAF-mutant advanced colorectal cancer: analysis from 2530 patients in randomised clinical trials. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seppala TT, Bohm JP, Friman M, et al. Combination of microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation status for subtyping colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1966–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sorbye H, Dragomir A, Sundstrom M, et al. High BRAF mutation frequency and marked survival differences in subgroups according to KRAS/BRAF mutation status and tumor tissue availability in a prospective population-based metastatic colorectal cancer cohort. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0131046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sahin IH, Kazmi SM, Yorio JT, et al. Rare though not mutually exclusive: a report of three cases of concomitant KRAS and BRAF mutation and a review of the literature. J Cancer 2013; 4: 320–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dienstmann R. Tumor side as model of integrative molecular classification of colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24: 989–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2011; 117: 4623–4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alvi MA, Loughrey MB, Dunne P, et al. Molecular profiling of signet ring cell colorectal cancer provides a strong rationale for genomic targeted and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies. Br J Cancer 2017; 117: 203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, et al. Microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105: 1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gonsalves WI, Mahoney MR, Sargent DJ, et al. Patient and tumor characteristics and BRAF and KRAS mutations in colon cancer, NCCTG/Alliance N0147. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014; 106: dju106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Samowitz WS, Albertsen H, Sweeney C, et al. Association of smoking, CpG island methylator phenotype, and V600E BRAF mutations in colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98: 1731–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Limsui D, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, et al. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by molecularly defined subtypes. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010; 102: 1012–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammons GJ, Yan Y, Lopatina NG, et al. Increased expression of hepatic DNA methyltransferase in smokers. Cell Biol Toxicol 1999; 15: 389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Loupakis F, Moretto R, Aprile G, et al. Clinico-pathological nomogram for predicting BRAF mutational status of metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2016; 114: 30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deng G, Bell I, Crawley S, et al. BRAF mutation is frequently present in sporadic colorectal cancer with methylated hMLH1, but not in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10: 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dienstmann R, Mason MJ, Sinicrope FA, et al. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hamilton SR. BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability status in colonic and rectal carcinoma: context really does matter. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105: 1075–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21: 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smeby J, Sveen A, Merok MA, et al. CMS-dependent prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations in primary colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Richman SD, Seymour MT, Chambers P, et al. KRAS and BRAF mutations in advanced colorectal cancer are associated with poor prognosis but do not preclude benefit from oxaliplatin or irinotecan: results from the MRC FOCUS trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5931–5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Masi G, et al. Initial therapy with FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1609–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peeters M, Price TJ, Cervantes A, et al. Final results from a randomized phase 3 study of FOLFIRI {+/–} panitumumab for second-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ilie M, Long E, Hofman V, et al. Diagnostic value of immunohistochemistry for the detection of the BRAFV600E mutation in primary lung adenocarcinoma Caucasian patients. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cremolini C, Di Bartolomeo M, Amatu A, et al. BRAF codons 594 and 596 mutations identify a new molecular subtype of metastatic colorectal cancer at favorable prognosis. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 2092–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yao Z, Yaeger R, Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 2017; 548: 234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jones JC, Renfro LA, Al-Shamsi HO, et al. (Non-V600) BRAF mutations define a clinically distinct molecular subtype of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2624–2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Intini R, Loupakis F, Cremolini C, et al. Clinical prognostic score of BRAF V600E mutated (BM) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): results from the “BRAF, BeCool” platform. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 639(Abs). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tol J, Punt CJ. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. Clin Ther 2010; 32: 437–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Van CE, Kohne CH, Lang I, et al. Cetuximab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: updated analysis of overall survival according to tumor KRAS and BRAF mutation status. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2011–2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bokemeyer C, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, et al. Addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy as first-line treatment for KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: pooled analysis of the CRYSTAL and OPUS randomised clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 1466–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Roock W, Claes B, Bernasconi D, et al. Effects of KRAS, BRAF, NRAS, and PIK3CA mutations on the efficacy of cetuximab plus chemotherapy in chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective consortium analysis. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 753–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Nicolantonio F, Martini M, Molinari F, et al. Wild-type BRAF is required for response to panitumumab or cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 5705–5712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rowland A, Dias MM, Wiese MD, et al. Meta-analysis of BRAF mutation as a predictive biomarker of benefit from anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody therapy for RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1888–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pietrantonio F, Petrelli F, Coinu A, et al. Predictive role of BRAF mutations in patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving cetuximab and panitumumab: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stintzing S, Miller-Phillips L, Modest DP, et al. Impact of BRAF and RAS mutations on first-line efficacy of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab: analysis of the FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) study. Eur J Cancer 2017; 79: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ince WL, Jubb AM, Holden SN, et al. Association of K-RAS, B-RAF, and p53 status with the treatment effect of bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Van CE, Tabernero J, Lakomy R, et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 3499–3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wirapati P, Pomella V, Vandenbosch B, et al. Velour trial biomarkers update: Impact of RAS, BRAF, and sidedness on aflibercept activity. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 3538(Abs).28862883 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Innocenti F, Ou F-S, Zemla T, et al. Somatic DNA mutations, MSI status, mutational load (ML): association with overall survival (OS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 3504(Abs). [Google Scholar]

- 53. Falcone A, Ricci S, Brunetti I, et al. Phase III trial of infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) compared with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan (FOLFIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: the Gruppo Oncologico Nord Ovest. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 1670–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Masi G, Loupakis F, Salvatore L, et al. Bevacizumab with FOLFOXIRI (irinotecan, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and folinate) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11: 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Loupakis F, Cremolini C, Salvatore L, et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment in BRAF mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1306–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yoshino T, Arnold D, Taniguchi H, et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a JSMO-ESMO initiative endorsed by CSCO, KACO, MOS, SSO and TOS. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: 44–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Geissler M, Klingler T, Riera Knorrenschild J, et al. 453PD1st-line mFOLFOXIRI + panitumumab vs FOLFOXIRI treatment of RAS wt mCRC: a randomized phase II VOLFI trial of the AIO (KRK-0109). Ann Oncol 2018; 29: mdy281.001(Abs). [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kopetz S, McDonough SL, Morris VK, et al. Randomized trial of irinotecan and cetuximab with or without vemurafenib in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer (SWOG 1406). J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 520(Abs). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Das Thakur M, Stuart DD. Molecular pathways: response and resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors in BRAF(V600E) tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature 2012; 483: 100–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition with Dabrafenib and Trametinib in BRAF V600-Mutant Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 4023–4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Schirripa M, Bergamo F, Cremolini C, et al. BRAF and RAS mutations as prognostic factors in metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Cancer 2015; 112: 1921–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van Geel R, Tabernero J, Elez E, et al. A phase Ib dose-escalation study of encorafenib and cetuximab with or without alpelisib in metastatic BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2017; 7: 610–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Pan JH, Zhou H, Zhu SB, et al. Development of small-molecule therapeutics and strategies for targeting RAF kinase in BRAF-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res 2018; 10: 2289–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Samalin E, Bouche O, Thezenas S, et al. Sorafenib and irinotecan (NEXIRI) as second- or later-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer and KRAS-mutated tumours: a multicentre Phase I/II trial. Br J Cancer 2014; 110: 1148–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, et al. Vemurafenib in multiple nonmelanoma cancers with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 726–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Delord JP, Robert C, Nyakas M, et al. Phase I dose-escalation and -expansion study of the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib (LGX818) in metastatic BRAF-mutant melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 5339–5348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen SH, Zhang Y, Van Horn RD, et al. Oncogenic BRAF deletions that function as homodimers and are sensitive to inhibition by RAF dimer inhibitor LY3009120. Cancer Discov 2016; 6: 300–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Vakana E, Pratt S, Blosser W, et al. LY3009120, a panRAF inhibitor, has significant anti-tumor activity in BRAF and KRAS mutant preclinical models of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 9251–9266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov 2012; 2: 227–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yaeger R, Cercek A, O’Reilly EM, et al. Pilot trial of combined BRAF and EGFR inhibition in BRAF-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 1313–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Corcoran RB, Andre T, Atreya CE, et al. Combined BRAF, EGFR, and MEK inhibition in patients with BRAF(V600E)-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov 2018; 8: 428–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hong DS, Morris VK, El Osta B, et al. Phase IB study of vemurafenib in combination with irinotecan and cetuximab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with BRAFV600E mutation. Cancer Discov 2016; 6: 1352–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Van Cutsem E, Cuyle P, Huijberts S, et al. O-027BEACON CRC study safety lead-in: Assessment of the BRAF inhibitor encorafenib + MEK inhibitor binimetinib + anti–epidermal growth factor receptor antibody cetuximab for BRAFV600E metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2018; 29: mdy149.026(Abs). [Google Scholar]

- 78. Vecchione L, Gambino V, Raaijmakers J, et al. A vulnerability of a subset of colon cancers with potential clinical utility. Cell 2016; 165: 317–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cremolini C, Pietrantonio F, Tomasello G, et al. Vinorelbine in BRAF V600E mutated metastatic colorectal cancer: a prospective multicentre phase II clinical study. ESMO Open 2017; 2: e000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Daud A, Tsai K. Management of treatment-related adverse events with agents targeting the MAPK pathway in patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncologist 2017; 22: 823–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C, et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Oberholzer PA, Kee D, Dziunycz P, et al. RAS mutations are associated with the development of cutaneous squamous cell tumors in patients treated with RAF inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zimmer L, Hillen U, Livingstone E, et al. Atypical melanocytic proliferations and new primary melanomas in patients with advanced melanoma undergoing selective BRAF inhibition. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2375–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Amaravadi RK, Hamilton KE, Ma X, et al. Multiple gastrointestinal polyps in patients treated with BRAF inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21: 5215–5221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2509–2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JL, et al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 1182–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab plus ipilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Thierry AR, El Messaoudi S, Mollevi C, et al. Clinical utility of circulating DNA analysis for rapid detection of actionable mutations to select metastatic colorectal patients for anti-EGFR treatment. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 2149–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chang GA, Tadepalli JS, Shao Y, et al. Sensitivity of plasma BRAF-mutant and NRAS-mutant cell-free DNA assays to detect metastatic melanoma in patients with low RECIST scores and non-RECIST disease progression. Mol Oncol 2016; 10: 157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yaeger R, Cercek A, Chou JF, et al. BRAF mutation predicts for poor outcomes after metastasectomy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2014; 120: 2316–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cremolini C, Casagrande M, Loupakis F, et al. Efficacy of FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab in liver-limited metastatic colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of clinical studies by Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest. Eur J Cancer 2017; 73: 74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Bachet JB, Moreno-Lopez N, Viganò L, et al. What is the prognostic impact of BRAF mutation in patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases? Results of nationwide intergroup (ACHBT, FRENCH, AGEO) cohort of 249 patients. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 3554 (Abs). [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gagniere J, Dupre A, Gholami SS, et al. Is hepatectomy justified for BRAF mutant colorectal liver metastases? a multi-institutional analysis of 1497 patients. Ann Surg. Epub ahead of print 10 July 2018. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Margonis GA, Buettner S, Andreatos N, et al. Association of BRAF mutations with survival and recurrence in surgically treated patients with metastatic colorectal liver cancer. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: e180996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Yaeger R, Yao Z, Hyman DM, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to BRAF V600E inhibition in colon cancers converge on RAF dimerization and are sensitive to its inhibition. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 6513–6523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]