Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the prevalence of frailty coding within the Dr Foster Global Comparators (GC) international database. We then aimed to develop and validate a risk prediction model, based on frailty syndromes, for key outcomes using the GC data set.

Design

A retrospective cohort analysis of data from patients over 75 years of age from the GC international administrative data. A risk prediction model was developed from the initial analysis based on seven frailty syndrome groups and their relationship to outcome metrics. A weighting was then created for each syndrome group and summated to create the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score. Performance of the score for predictive capacity was compared with an established prognostic comorbidity model (Elixhauser) and tested on another administrative database Hospital Episode Statistics (2011-2015), for external validation.

Setting

34 hospitals from nine countries across Europe, Australia, the UK and USA.

Results

Of 6.7 million patient records in the GC database, 1.4 million (20%) were from patients aged 75 years or more. There was marked variation in coding of frailty syndromes between countries and hospitals. Frailty syndromes were coded in 2% to 24% of patient spells. Falls and fractures was the most common syndrome coded (24%). The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality, 30-day non-elective readmission and long length of hospital stay. The score had significant predictive capacity beyond that of other known predictors of poor outcome in older persons, such as comorbidity and chronological age. The score’s predictive capacity was higher in the elective group compared with non-elective, and may reflect improved performance in lower acuity states.

Conclusions

Frailty syndromes can be coded in international secondary care administrative data sets. The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score significantly predicts key outcomes. This methodology may be feasibly utilised for case-mix adjustment for older persons internationally.

Keywords: frailty, secondary care, measure, administrative, risk prediction

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large multicentre international study across Europe, Australia and the USA utilising a routinely collected administrative data with the aim of providing a simple model for case-mix adjustment for older persons in secondary care.

The data set used represent whole populations, and there was little missing data.

Robust statistical methods were used and the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score was validated on an external data set (Hospital Episode Statistics).

Our model’s predictive capacity is comparable with other recent single country studies.

The variability in frequency of coding of frailty syndromes across countries may limit reliability and generalisability.

Introduction

Increased population ageing stems from a range of diverse factors, including lower childhood and adult mortality, improved fertility, migration, relative world peace and improved health and social care.1 For many, this phenomenon is associated with good health and quality of life.2 For others, there is increased comorbidity,3 functional decline4 and poorer quality of life. Differences in the health and function of individuals as they grow older is not readily explained by chronological age.5 Frailty is common and increasingly prevalent with advancing age and often defined as a decrease in physiological reserve over a life course. Using this pathophysiological model of frailty several underlying processes have been described, including chronic inflammation,6 7 sarcopaenia,8 anaemia9 and coagulopathy, steroid hormone dysregulation,10 11 low vitamin D levels, malnutrition12 13 and insulin resistance14 15. These deficits can accumulate over the course of lifetime exposure to environmental stressors. Frailty manifests as a combination of the pathophysiological consequence of inbuilt senescence and the accumulation of defects throughout a life course. Frailty ultimately results in recognisable clinical manifestations such as recurrent falls and delirium and is associated with increased mortality, disability and high resource utilisation.16 Conceptually and operationally, frailty appears to be related to, but distinct from, disability, comorbidity and chronological age.17 The importance of contributing environmental factors and the psychosocial impact of frailty are increasingly being recognised18 as important.

Assessing frailty in the hospital setting is challenging. Many frailty assessment scores tested have poor reliability, require large amounts of data, or specialised equipment and have poor predictive performance.19 Given these limitations, there is increasing interest in utilising routinely collected administrative data for risk prediction modelling for those at risk of frailty, particularly older persons. Risk prediction models estimate the likelihood of developing a specific outcome, or having a specific condition. These models can be utilised for the purposes of case-mix adjustment or risk stratification. Case-mix risk adjustment allows for more accurate comparison of organisational performance by reducing confounding bias. For example, when considering mortality as an outcome measure for organisations, patient-specific factors such as illness severity influence outcome must be taken into account. Risk stratification allows for possible segmentation of a population into different levels of risk for developing a specific outcome. This segmentation can then be used to health system planning or inform targeting of resources.

In older persons, risk prediction models often use chronological age,20 comorbidity21 and functional dependence22 as patient-specific factors for risk prediction. In the context of long-term care (eg, nursing homes), risk prediction models often use functional dependence as a patient factor, to aid appropriate health resource utilisation and costing.22–24 A recent English study in the primary care setting derived an electronic frailty index from patient records with predictive validity for nursing home admission, hospitalisation and mortality.25 In secondary care, risk prediction models for older persons have utilised measures of demographics, and comorbidity in the form of diagnostic26–29 and procedural codes,30 31 as well as prescription data.28 32 Frailty syndromes are recognised as clinical manifestations of frailty.33 These common presentations in older persons include recurrent falls, cognitive impairment, incontinence and pressure ulcers, are associated with poor outcome. Recent studies have explored the coding of frailty syndromes within secondary care administrative data sets in the UK, and its association with in-hospital mortality, non-elective readmission and functional decline.34 35

In this study, we explored the prevalence of coded frailty syndromes within an international secondary care data set to develop and validate a risk prediction model based on frailty syndromes for the outcomes of mortality, non-elective readmission and long length of stay. We sought to compare the performance of this model with an established prognostic comorbidity model for the above outcomes.

Methods

Data sources

The Global Comparators programme at Dr Foster was an international hospital collaborative which ran from 2011 to 2017, focused on pooling and benchmarking data, knowledge-sharing networks and health services research to better understand variations in outcomes and disseminate international best practice. The hospitals within the collaboration contributed administrative data to be pooled within the Global Comparators data set, using established data cleaning processes.36 This provided a rich patient-level data set containing demographics, diagnostic codes, procedure codes and outcomes, collected primarily for administrative purposes, such as operational needs and costing. To develop and test Dr Foster Global Frailty Score, Global Comparators data were extracted from 34 hospitals in nine countries: Australia, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, UK and USA.

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) is an English national administrative data set, housed within the safe haven of NHS Digital, and contains administrative data from English hospital trusts, which are cleaned and securely stored. This data set was used to validate the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score. We included the 138 English acute non-specialist hospital trusts, excluding hyperspecialist hospitals (eg, single pathology quaternary referral units) and mental health units, which have different case-mix.

Study population

Patient records were included in the analysis if they fulfilled the criteria of patient age ≥75 years and required an elective or non-elective hospital admission of 24 hours or more. Patient spells were excluded if the age, sex or length of stay was recorded as missing or invalid, or the admission was planned and the patient discharged home on the same day, or the admission was unplanned but no procedure was undertaken and the patient went home after recorded length of stay less than 2 days. This was to exclude records with inadequate quality data, and patients admitted into observations units or day-case attendances. Overall, 0.17% of data were missing within the derivation data set.

Coding frailty

Each patient record corresponded to a spell covering a patient’s total length of stay at a hospital. Within HES, these were aggregated into ‘superspells’ (admissions), which encompass the full length of stay for the patient across all hospital trusts before their final discharge. Seven groups of frailty syndromes were chosen to represent the common domains used in comprehensive geriatric assessment: Dementia and Delirium, Mobility Problems, Falls and Fractures, Pressure Ulcers and Weight Loss, Incontinence, Dependence and Care, as well as Anxiety and Depression were coded within International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries and Causes of Death (ICD) diagnostic coding groups, and within all available diagnostic fields. As the Global Comparators data set comprised hospitals which utilised different revisions of ICD (revision 9 and 10), equivalent diagnostic codes for both versions were compiled. These diagnostic coding groups were modified from previously published work on English national administrative data.34 Online supplementary appendix 1 displays the full list of ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes utilised to code for the seven frailty syndrome groups. Trends by calendar year and month, country and frailty syndrome group were plotted to investigate frequency of coding for the years 2010 to 2014. Based on this analysis, years 2012 to 2013 were selected as having stable coding for multivariable risk prediction modelling within the derivation data set.

bmjopen-2018-026759supp001.pdf (359.5KB, pdf)

Risk models

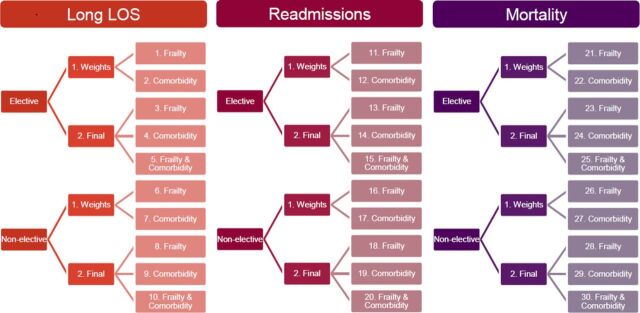

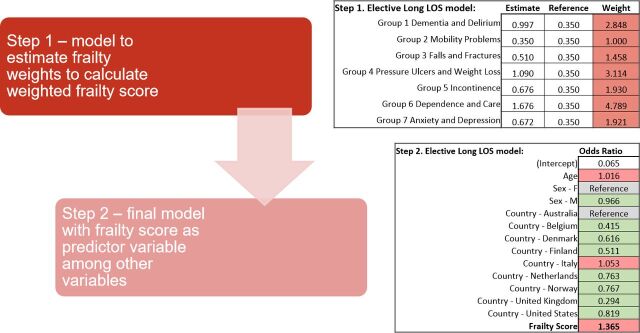

Within the Global Comparators data set, 30 separate regression models were undertaken, to account for admission status, frailty, Elixhauser comorbidity and combination of frailty and Elixhauser for the three outcomes above(figure 1). The characteristics of predictor and outcome variables included within the models are described in tables 1 and 2. Elective and non-elective hospital admission populations were modelled separately. A two-step process for each outcome was utilised to model the frailty and comorbidity scores. First, binary logistic regression was utilised to ascertain ORs for each frailty syndrome group and each outcome, within the population subgroups separately (elective and non-elective). The natural log of OR (ln OR) was used to create weights for each frailty syndrome group, using the smallest ln OR as reference (weighted 1.0). Second, the summation of the weights for each frailty syndrome group was utilised to create a frailty score. The patient-level frailty score was then included within a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for age, gender and country, for each outcome. Figure 2 illustrates an example of this two-step process for the outcome of upper quartile length of stay.

Figure 1.

Summary of 30 risk prediction models undertaken, accounting for admission status, frailty and comorbidity.

Table 1.

Predictors inputs for frailty risk prediction model (independent predictors)

| Name | Time span | Description | Comments |

| Age | Current spell | Age on admission | |

| Gender | Current spell | Gender on admission | |

| Country | Current spell | Country from which hospital contributed data | Nominal; countries were: Australia Belgium Denmark Finland Italy Netherlands Norway UK USA |

| Dementia & delirium | 12 month historical binary indicator | A binary flag indicating whether a relevant diagnosis has been received during any inpatient spell in the past 12 months | Final Dr Foster global frailty score is weighted (see risk stratification models section for further details) |

| Mobility problems | |||

| Falls & fractures | |||

| Pressure ulcers & weight loss | |||

| Dependence and care | |||

| Anxiety & depression | |||

| Comorbidity (Elixhauser) | 12 month historical score | A weighted score (see risk stratification models section for further details) | Integer |

| Number of previous admissions | 12 month historical count | The number of emergency admission spells in the previous 12 months, excluding the current spell | Integer |

Table 2.

Predictor outputs for frailty risk prediction model (dependent variables)

| Name | Time span | Description | Comments |

| In-hospital mortality | Current spell | Indicates if the discharge method was death | |

| 30 day non-elective readmission | 30 days from discharge | Indicates if the patient had an emergency admission with admission date between 1 and 30 days following the discharge date of the index admission | Spells that ended in death are excluded from the analysis |

| Long length of stay | Current spell | Upper quartile length of hospital stay for country |

Figure 2.

Example of two-step multivariable logistic regression process for the outcome of upper quartile length of stay. F, female; LOS, length of stay, M, male.

The Elixhauser comorbidity score was calculated for each outcome using previously described methods.37 To provide comparison, the Elixhauser comorbidity score was then included within a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusting for age, gender and country, for each outcome. Finally, both the Elixhauser comorbidity and Dr Foster Global Frailty Score were then included within a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for age, gender and country, for each outcome. The predicted probabilities from these regression models were utilised to calculate area under the receiver operator characteristic curves (AUC) as a measure of predictive capacity for each outcome. This two-step process was repeated for the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score on HES years 2011 to 2015 for external validation.

Performance metrics

Multicollinearity between predictor variables was investigated by variance inflation factor (VIF), where VIF scores of over 3 were taken to denote unacceptable collinearity. The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic was calculated for each model to ascertain model calibration. The Wald statistic was calculated to explore the explanatory power of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score, Elixhauser Comorbidity Score, age, country and gender for each of the three outcomes. Statistical analysis was undertaken using the R Statistical Package.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study

Results

Descriptive statistics

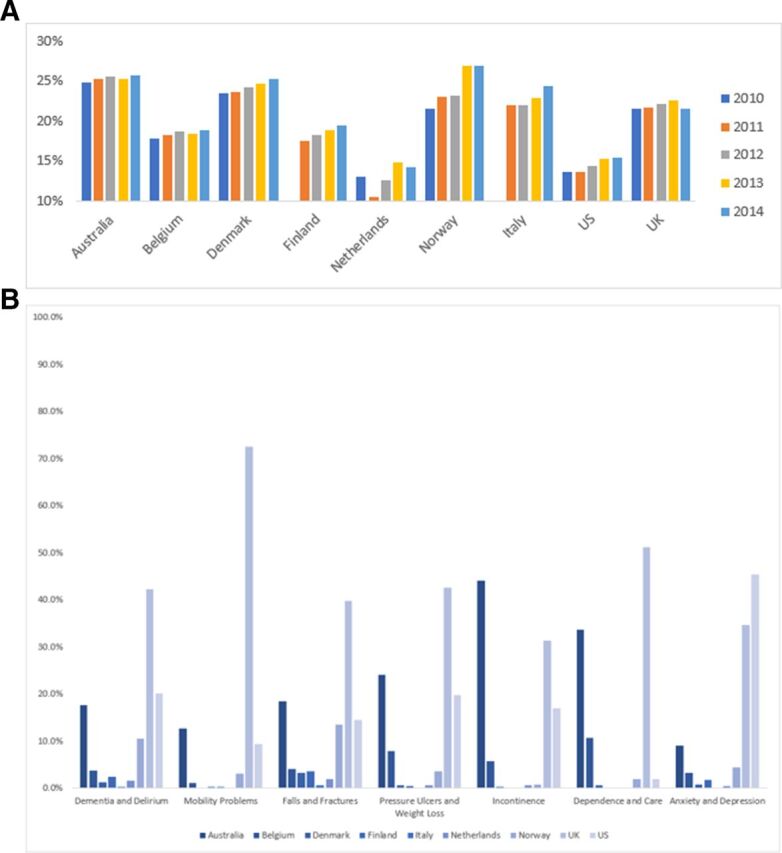

Of the 6 739 790 spells within the Global Comparators Database from 2010 to 2014, 1 366 187 (20%) involved patients aged ≥75 years. There was variation in frequency of coding of frailty syndromes across the countries. The four countries with most volume of coded frailty syndromes were Australia, Belgium, the UK and the USA. Figure 3a and b describes the percentage of spells of patients ≥75 years to total volume by country and year within the database, and the frequency of coding for frailty syndromes by country for the year 2013.

Figure 3.

(A) Percentage volume of patients aged ≥75 year to total volume by country and year within global comparators data set. (B) Frequency of coding for frailty syndromes by country for year 2013 within global comparators data set (colour scale by country) in patients aged ≥75 years.

Coded frailty syndromes

Frailty syndromes were coded in 2% to 24% of patient spells among patients aged ≥75 years from 2010 to 2014 within the Global Comparators database: Falls and Fractures n=326 528 (24%), Dementia and Delirium n=215 629 (16%), Anxiety and Depression n=87 732 (6%), Pressure Ulcers and Weight Loss n=66 208 (5%), Incontinence n=50 277 (4%), Mobility Problems n=39 479 (3%) and Dependence and Care n=28 294 (2%). At least one frailty syndrome was present in 538 766 (39%) of spells.

Derivation cohort

Of the 294 998 patient spells from 2012 to 2013 for those aged ≥75 years used in the predictive models within the derivation cohort from the Global Comparators data set, 221 441 (75%) were non-elective admissions and 158 595 were female (54%). Patient spells that ended with inpatient mortality (42 354, 14%) were excluded from the predictive models exploring non-elective readmission.

Dr Foster global frailty score

Negative scores were set to 0 and positive scores were not capped. The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score varied based on outcome and population (elective and non-elective), and remained significant after multivariable adjustment. Table 3 summarises the ORs of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score and Elixhauser Comorbidity Score after multivariable adjustment for age, gender and country for the outcomes of in-hospital mortality, 30 day non-elective readmission and upper quartile length of stay (for country), by elective and non-elective population groups. Online supplementary appendix 2 displays full multivariable adjustment of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for Elixhauser and Dr Foster global frailty score after multivariable adjustment for age, gender and country

| Outcome | Score range | Population | OR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P value | |

| Dr Foster global frailty score | In-hospital mortality | 0–11 | Elective | 1.277 | 1.247 | 1.308 | <0.001 |

| 0–13 | Non-elective | 1.109 | 1.103 | 1.116 | <0.001 | ||

| 30 day non-elective readmission | 0–6 | Elective | 1.106 | 1.060 | 1.154 | <0.001 | |

| 0–4 | Non-elective | 1.056 | 1.031 | 1.082 | <0.001 | ||

| Upper quartile length of stay (for country) | 0–16 | Elective | 1.365 | 1.347 | 1.382 | <0.001 | |

| 0–17 | Non-elective | 1.199 | 1.194 | 1.205 | <0.001 | ||

| Elixhauser comorbidity score | In-hospital mortality | Elective | 1.309 | 1.290 | 1.329 | <0.001 | |

| Non-elective | 1.130 | 1.126 | 1.133 | <0.001 | |||

| 30 day non-elective readmission | Elective | 1.144 | 1.130 | 1.158 | <0.001 | ||

| Non-elective | 1.045 | 1.042 | 1.048 | <0.001 | |||

| Upper quartile length of stay (for country) |

Elective | 1.101 | 1.097 | 1.105 | <0.001 | ||

| Non-elective | 1.069 | 1.068 | 1.071 | <0.001 |

When both the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score and Elixhauser Comorbidity Score were included in multivariable risk adjustment models for age, gender and country, the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score remained significant for the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and upper quartile length of stay, but not for 30 day non-elective readmission (table 4).

Table 4.

Odds ratios for Elixhauser and Dr Foster global frailty score after multivariable adjustment for age, gender and country with both scores in model

| Outcome | Population | Score | OR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P value |

| In-hospital mortality | Elective | Elixhauser | 1.283 | 1.263 | 1.304 | <0.001 |

| Frailty | 1.114 | 1.085 | 1.144 | <0.001 | ||

| Non-elective | Elixhauser | 1.123 | 1.119 | 1.126 | <0.001 | |

| Frailty | 1.058 | 1.052 | 1.065 | <0.001 | ||

| 30 day non-elective readmission | Elective | Admission history* | 1.273 | 1.234 | 1.314 | <0.001 |

| Elixhauser | 1.142 | 1.128 | 1.157 | <0.001 | ||

| Frailty | 1.032 | 0.988 | 1.077 | 0.160 | ||

| Non-elective | Admission history* | 1.240 | 1.228 | 1.252 | <0.001 | |

| Elixhauser | 1.045 | 1.042 | 1.048 | <0.001 | ||

| Frailty | 1.024 | 1.000 | 1.049 | 0.052 | ||

| Upper quartile length of stay | Elective | Elixhauser | 1.081 | 1.077 | 1.085 | <0.001 |

| Frailty | 1.243 | 1.227 | 1.260 | <0.001 | ||

| Non-elective | Elixhauser | 1.055 | 1.053 | 1.056 | <0.001 | |

| Frailty | 1.137 | 1.131 | 1.142 | <0.001 |

*Admission history included in multivariable model exploring 30 day non-elective readmission.

The predictive capacity of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score and Elixhauser Comorbidity Score are compared in table 5. When the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score and Elixhauser Comorbidity Score are both included in a multivariable model adjusted for age, gender and country, the predictive capacity is moderate-to-good. The predictive capacity of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Score generally exceeds that of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score for all three outcomes.

Table 5.

Area under the receiver operator statistic curve for outcomes by Elixhauser score, Dr Foster global frailty score and population within global comparators data set

| Global comparators dataset | Elixhauser | Dr Foster global frailty score | Elixhauser and Dr Foster global frailty score | |||

| Outcome/AUC | Elective | Non-elective | Elective | Non-elective | Elective | Non-elective |

| In-hospital mortality | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 0.69 |

| 30 day non-elective readmission* | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.64 |

| Upper quartile length of stay | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.65 |

*Admission history included in multivariable model exploring 30 day non-elective readmission.

AUC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curves.

The Wald statistic for independent variables included in final models by population and outcome are displayed in table 6. Overall, the explanatory power of the Elixhauser Comorbidity Score exceeds the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score for all three outcomes.

Table 6.

Wald statistic for independent variables of final models by outcome and population

| Upper quartile length of stay | 30 day non-elective readmission | In-hospital mortality | ||||

| Elective | Non-elective | Elective | Non-elective | Elective | Non-elective | |

| Age | 31.1 | 31.4 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 46.4 | 747.2 |

| Sex | 18.7 | 0.2 | 6.9 | 77.6 | 9.5 | 85.2 |

| Country | 162.0 | 244.2 | 31.1 | 102.1 | 12.8 | 137.8 |

| Admission history | - | - | 225.9 | 1888.4 | - | - |

| Dr Foster global frailty score | 1020.7 | 2579.9 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 62.7 | 318.2 |

| Elixhauser score | 1727.5 | 4075.1 | 420.4 | 848.4 | 973.9 | 4842.1 |

Performance metrics

All our models displayed significance at p<0.05 for the Hosmer-Lemeshow tests for goodness-of-fit test. These findings have been similarly described by others who have produced models on large data sets as the test is recognised to detect unimportant differences.37 38 None of the predictor variables demonstrated unacceptable collinearity.39

Validation cohort

Of the 7 195 950 patient spells from 2011 to 2015 used in the predictive models within the validation cohort from English national Hospital Episode Statistics data, 6 128 811 (85%) were non-elective admissions, and 564 182 (7.8%) patient spells ending with in-hospital mortality were excluded from predictive models exploring non-elective readmission.

The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score remained significant after multivariable adjustment within the validation dataset. However, the predictive capacity and ORs were generally lower across all three outcomes compared with the derivation cohort. Table 7 summarises the ORs and AUC of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score after multivariable adjustment for age, gender and calendar year for the outcomes of in-hospital mortality, 30 day non-elective readmission and upper quartile length of stay (for country), by elective and non-elective population groups. Online supplementary appendix 3 displays full multivariable adjustment of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score within the validation data set.

Table 7.

Odds ratios and for area under the receiver operator statistic curve for global frailty score following multivariable adjustment for age, gender, calendar year by population subgroup and outcome within validation dataset.

| Outcome | Population | AUC | OR | Lower CI | Upper CI | P value |

| In-hospital mortality | Elective | 0.649 | 1.173 | 1.171 | 1.174 | <0.001 |

| Non-elective | 0.655 | 1.108 | 1.107 | 1.109 | <0.001 | |

| 30 day non-elective readmission | Elective | 0.630 | 1.045 | 1.044 | 1.047 | <0.001 |

| Non-elective | 0.630 | 1.030 | 1.030 | 1.031 | <0.001 | |

| Upper quartile length of stay (for country) | Elective | 0.676 | 1.193 | 1.192 | 1.193 | <0.001 |

| Non-elective | 0.677 | 1.055 | 1.055 | 1.055 | <0.001 |

*Admission history included in multivariable model exploring 30 day non-elective readmission.

AUC, area under the receiver operator characteristic curves.

Discussion

Our study found that frailty syndromes are coded with variable frequency within a large (N≈1.3 million) international data set of hospitalised older persons (aged over 75 years) utilising readily available administrative data, with Falls & Fractures and Dementia & Delirium being the most frequently coded syndromes. This is consistent with a previous study using English administrative data.35 The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score was derived from these coded syndromes within this data set, and further validated on an English national secondary care data set (N≈7.2 million). The score was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality, 30 day non-elective readmission and long length of hospital stay. The score’s predictive capacity was generally higher in the elective group compared with the non-elective, and may reflect improved performance in lower acuity states.

The ORs and predictive capacity in the validation cohort were generally lower than the derivation cohort, but are in keeping with other risk prediction models for older persons within the English secondary care administrative data.34 40 There was marked variation in volume and frequency of coding for frailty syndromes across participating countries (figure 2). These differences may reflect different coding practices and contrasting healthcare systems. These differences may contribute to poorer performance within the validation cohort. Nevertheless, within pooled data across all participating sites, the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score appears to significantly predict in-hospital mortality and upper quartile length of stay (for country) after multivariable adjustment for age, gender, country and comorbidity.

When both the Elixhauser Comorbidity Score and Dr Foster Global Frailty Score were included within multivariable adjustment, both scores remain statistically significant for the outcomes of in-hospital mortality and upper quartile length of stay, suggesting they are not collinear.

Although the setting for the validation cohort was sourced only from English data, it was a large data set (n=~7 million spells). After multivariable adjustment for age, gender and year, the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score remained significant for all three outcomes. Predictive power was demonstrated to be similar to a previous study,34 and comparable to the derivation cohort (table 5).

In clinical practice, risk stratification in older persons for the secondary care setting often use demographics (including chronological age), physiological based track-and-trigger systems (eg, National Early Warning Score41), biomarkers (eg, troponin) and understanding about the prognosis of specific disease states (eg, comorbidity). When adjusting for case-mix between systems or at organisational level, registry42 or administrative27 data are often employed, as large scale high quality data from patient records are not readily available. Consequently, risk prediction models using administrative data have sought to differentiate risk by using diagnostic,26–29 procedural30 31 and more recently, prescribing codes.28 32

There are several risk models in the USA utilising frailty-specific groups of diagnostic codes within Medicare administrative data, Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey data and Veteran’s Affairs administrative data. Examples of these risk prediction models include Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG, Johns Hopkins University) frailty-defining diagnoses indicator27 and High-Risk Diagnosis for the Elderly Scale.29 In the UK, studies exploring case-mix adjustment for older persons using administrative data have utilised HES as a data source, with diagnostic groups for multimorbidity37 and complexity,43 as well as frailty34 40 being tested in the literature. Online supplementary appendix 4 summarises the characteristics, setting, data sources, predictor and outcome variables and performance of recent case-mix studies for older persons utilising administrative data. Where predictive capacity is known, the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score performs comparably if not favourably.

Our study benefits from being a large multicentre international study across Europe, Australia and the USA that utilised routinely collected administrative data with the aim of case-mix adjustment for older persons in secondary care. The data sets represent whole populations, and there was little missing data. Our study employed robust statistical methods and included validation of the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score on an external data set. It expands the diagnostic coding, provides external validation for a previous UK study34 and extends it to include elective patients. The approach of targeting frailty syndromes for hospitalised patients has support in existing literature,44 and in keeping with national standards bodies recommendations in the UK.33 45 46 Additionally, our model’s predictive capacity is not improved on by a recent UK study,40 and its predictive capacity is arguably more uniform across the three outcomes. However, we note that our model’s predictive powers are not suitable for clinical risk prediction at the patient’s bedside (AUC >0.80). Further investigation of appropriate cut-points based on desired model sensitivity and specificity for the above outcomes depending on how the model is used (eg, health resource planning) represents future work.

However, some limitations warrant mention. The variability in frequency of coding of frailty syndromes across countries may limit reliability and generalisability, although the country of origin was accounted for in the multivariable regression. Further subgroup analysis in countries with similar frequency of coding, or hierarchical regression to account for clusters, may be the next step. The hospitals that contributed data to the Global Comparators dataset were mainly large academic centres with reputations of clinical excellence. As such, the quality of coding and patient outcomes represented may not be representative of other institutions. The score was developed on hospitalised populations of age ≥75 years as the majority of frail older persons fall within this age-group, particularly in Western Europe. This score is therefore not validated in those who fall below 75 years of age. Additionally, the study focused on hospitalised patients of ≥24 hours to exclude patients admitted to observational units, for investigations or procedures. There is increasing acceptance for the acute medical management of older persons in an ambulatory setting. This methodology will exclude same-day discharges, limiting generalisability.

The accuracy of coding in administrative data has been challenged, and sampling of local clinical units was not feasible. The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score was based on diagnostic codes and thus did not fully encompass all dimensions of frailty such as functional and socio-environmental measures as these are not well coded in the administrative data at this time. Future work linking the data sets to pharmacy, social care, primary care and registry data may provide for a richer comprehensive case-mix adjustment. A small proportion of the validation cohort may have been duplicated from the derivation cohort (eight hospitals in calendar year 2013). However, using national data from several calendar years minimises the effect of this overlap. Lastly, we have not demonstrated population segmentation utilising the Dr Foster Global Frailty Score to show separation of risk for the three outcomes above, and this represents future work.

Our study adds to the existing literature regarding the secondary use of administrative data for case-mix adjustment in general, and for hospitalised older persons in particular. It links the clinically valid concept of frailty syndromes to a reproducible method of measurement within administrative data sets. The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score may potentially be used to routinely identify older persons at risk of adverse outcomes for the purposes of targeted resource allocation, commissioning or service development. It may form the basis of a global comparator of risk adjustment for older persons.

Conclusion

Frailty syndromes can be feasibly coded in international secondary care administrative data sets. The Dr Foster Global Frailty Score based on coded frailty syndromes significantly predicts in-hospital mortality and upper quartile length of stay in international datasets, and additionally 30 day non-elective readmission in England’s national hospital data set. This methodology may be feasibly utilised for case-mix adjustment for older persons across the international setting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JTYS conceived study, designed analysis, interpreted results and wrote first draft. AH conceived study, designed analysis, interpreted results. JK, DL, CP and CC designed analysis, interpreted results and contributed to ongoing writing. AB and DB interpreted results and contributed to ongoing writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CP has shares in Fidelity Health, has been a consultant for Merck and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Ethics approval: Data sharing agreements with all individual hospitals included were in place in order to receive the data. The data used in this study was collected for administrative purposes and anonymised. As per Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees (GAfREC), research limited to secondary use of information previously collected in the course of normal care (without an intention to use it for research at the time of collection), provided that the patients or service users are not identifiable to the research team in carrying out the research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data used for this study was available due to data sharing agreements signed with the individual hospitals as part of their participation in the Global Comparators programme managed by Dr Foster. The Global Comparators programme no longer exists and therefore data sharing agreements are no longer in place to allow for supplementary data sharing.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. World Population Ageing. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Survey of public attitudes and behaviours towards the environment: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 2011;10:430–9. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Family Resources Survey. Department for work & pensions; 2014/2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lacas A, Rockwood K. Frailty in primary care: a review of its conceptualization and implications for practice. BMC Med 2012;10:4. 10.1186/1741-7015-10-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, et al. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:575–84. 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruunsgaard H, Bjerregaard E, Schroll M, et al. Muscle strength after resistance training is inversely correlated with baseline levels of soluble tumor necrosis factor receptors in the oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:237–41. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cesari M, Leeuwenburgh C, Lauretani F, et al. Frailty syndrome and skeletal muscle: results from the Invecchiare in Chianti study. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1142–8. 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roy CN. Anemia in frailty. Clin Geriatr Med 2011;27:67–78. 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Baylis D, Bartlett DB, Syddall HE, et al. Immune-endocrine biomarkers as predictors of frailty and mortality: a 10-year longitudinal study in community-dwelling older people. Age 2013;35. 10.1007/s11357-012-9396-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Varadhan R, Walston J, Cappola AR, et al. Higher levels and blunted diurnal variation of cortisol in frail older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2008;63:190–5. 10.1093/gerona/63.2.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaiser M, Bandinelli S, Lunenfeld B. Frailty and the role of nutrition in older people. A review of the current literature. Acta Biomed 2010;81(Suppl 1):37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hubbard RE, Lang IA, Llewellyn DJ, et al. Frailty, body mass index, and abdominal obesity in older people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2010;65:377–81. 10.1093/gerona/glp186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fulop T, Larbi A, Witkowski JM, et al. Aging, frailty and age-related diseases. Biogerontology 2010;11:547–63. 10.1007/s10522-010-9287-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbatecola AM, Paolisso G. Is there a relationship between insulin resistance and frailty syndrome? Curr Pharm Des 2008;14:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med 2011;27:1–15. 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:M255–63. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu R, Wu W-C, Leung J, et al. Frailty and its contributory factors in older adults: a comparison of two asian regions (Hong Kong and Taiwan). Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:1096. 10.3390/ijerph14101096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hogan DB, Maxwell CJ, Afilalo J, et al. A scoping review of frailty and acute care in middle-aged and older individuals with recommendations for future research. Can Geriatr J 2017;20:22–37. 10.5770/cgj.20.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1108–12. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50268.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharabiani MT, Aylin P, Bottle A. Systematic review of comorbidity indices for administrative data. Med Care 2012;50:1109–18. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31825f64d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eilertsen TB, Kramer AM, Schlenker RE, et al. Application of functional independence measure-function related groups and resource utilization groups-version III systems across post acute settings. Med Care 1998;36:695–705. 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carpenter GI, Turner GF, Fowler RW. Casemix for inpatient care of elderly people: rehabilitation and post-acute care. Casemix for the Elderly Inpatient Working Group. Age Ageing 1997;26:123–31. 10.1093/ageing/26.2.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poss JW, Hirdes JP, Fries BE, et al. Validation of Resource Utilization Groups version III for Home Care (RUG-III/HC): evidence from a Canadian home care jurisdiction. Med Care 2008;46:380–7. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815c3b6c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:353–60. 10.1093/ageing/afw039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bottle A, Aylin P, Bell D. Effect of the readmission primary diagnosis and time interval in heart failure patients: analysis of English administrative data. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:846–53. 10.1002/ejhf.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McIsaac DI, Bryson GL, van Walraven C. Association of frailty and 1-year postoperative mortality following major elective noncardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. JAMA Surg 2016;151:538–45. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.5085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sternberg SA, Bentur N, Abrams C, et al. Identifying frail older people using predictive modeling. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:e392–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desai MM, Bogardus ST, Williams CS, et al. Development and validation of a risk-adjustment index for older patients: the high-risk diagnoses for the elderly scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:474–81. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Faurot KR, Jonsson Funk M, Pate V, et al. Using claims data to predict dependency in activities of daily living as a proxy for frailty. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:59–66. 10.1002/pds.3719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Davidoff AJ, Zuckerman IH, Pandya N, et al. A novel approach to improve health status measurement in observational claims-based studies of cancer treatment and outcomes. J Geriatr Oncol 2013;4:157–65. 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dubois M-F, Dubuc N, Kröger E, et al. Assessing comorbidity in older adults using prescription claims data. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research 2010;1:157–65. 10.1111/j.1759-8893.2010.00030.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Royal College of Physicians. Acute care toolkit 3: acute medical care for frail older people. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Developing and validating a risk prediction model for acute care based on frailty syndromes. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008457. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soong J, Poots AJ, Scott S, et al. Quantifying the prevalence of frailty in English hospitals. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008456. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bottle A, Middleton S, Kalkman CJ, et al. Global comparators project: international comparison of hospital outcomes using administrative data. Health Serv Res 2013;48(6 Pt 1):2081–100. 10.1111/1475-6773.12074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bottle A, Aylin P. Comorbidity scores for administrative data benefited from adaptation to local coding and diagnostic practices. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1426–33. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hosmer DW, Hosmer T, Le Cessie S, et al. A comparison of goodness-of-fit tests for the logistic regression model. Stat Med 1997;16:965–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fox J, Monette G. Generalized collinearity diagnostics. J Am Stat Assoc 1992;87:178–83. 10.1080/01621459.1992.10475190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet 2018;391:1775–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Prytherch DR, Smith GB, Schmidt PE, et al. ViEWS--Towards a national early warning score for detecting adult inpatient deterioration. Resuscitation 2010;81:932–7. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rudd AG, Lowe D, Hoffman A, et al. Secondary prevention for stroke in the United Kingdom: results from the National Sentinel Audit of Stroke. Age Ageing 2004;33:280–6. 10.1093/ageing/afh107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ruiz M, Bottle A, Long S, et al. Multi-Morbidity in Hospitalised Older Patients: Who Are the Complex Elderly? PLoS One 2015;10:e0145372. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Soong JT, Poots AJ, Bell D. Finding consensus on frailty assessment in acute care through Delphi method. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012904. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Banerjee J, Conroy S, Cooke MW. Quality care for older people with urgent and emergency care needs in UK emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2013;30:699–700. 10.1136/emermed-2012-202080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turner G. Recognising Frailty. British Geriatric Society 2014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026759supp001.pdf (359.5KB, pdf)