Abstract

Inbred laboratory mouse strains carry endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) classed as ecotropic, xenotropic or polytropic mouse leukemia viruses (E-, X- or P-MLVs). Some of these MLV ERVs produce infectious virus and/or contribute to the generation of intersubgroup recombinants. Analyses of selected mouse strains have linked the appearance of MLVs and virus-induced disease to the strain complement of MLV E-ERVs and to host genes that restrict MLVs, particularly Fv1. Here we screened inbred strain DNAs and genome assemblies to describe the distribution patterns of 45 MLV ERVs and Fv1 alleles in 58 classical inbred strains grouped in two ways: by common ancestry to describe ERV inheritance patterns, and by incidence of MLV-associated lymphomagenesis. Each strain carries a unique set of ERVs, and individual ERVs are present in 5–96% of the strains, often showing lineage-specific distributions. Two ERVs are alternatively present as full-length proviruses or solo long terminal repeats. High disease incidence strains carry the permissive Fv1n allele, tested strains have highly expressed E-ERVs and most have the Bxv1 X-ERV; these three features are not present together in any low-moderate disease strain. The P-ERVs previously implicated in P-MLV generation are not preferentially found in high leukemia strains, but the three Fv1 alleles that restrict inbred strain E-MLVs are found only in low-moderate leukemia strains. This dataset helps define the genetic basis of strain differences in spontaneous lymphomagenesis, describes the distribution of MLV ERVs in strains with shared ancestry, and should help annotate sequenced strain genomes for these insertionally polymorphic and functionally important proviruses.

Introduction

The multiple inbred strains of laboratory mice carry three host range subgroups of MLVs (reviewed in [1]). MLVs with ecotropic host range (E-MLVs) infect only rodent cells, while the various xenotropic and polytropic MLVs (X-, P-MLVs, collectively X/P-MLVs) infect different subsets of mouse taxa and other mammalian species [2, 3]. The E-MLVs all use the CAT1 receptor [4], and the X/P-MLVs all use the functionally polymorphic XPR1 receptor [5].

These three host range subgroups of MLVs are found as infectious viruses and as endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), which are DNA copies that integrated into the germline during past virus infections and were passed to subsequent generations. Individual ERVs can be present or absent in the various mouse strains. Over 30 distinct E-MLV ERVs (E-ERVs, termed Emvs) are found in laboratory mice, and individual strains can carry up to six Emvs [6], many of which are capable of producing infectious virus [1]. Laboratory strains also carry X-ERVs (Xmvs) [7], some of which can produce virus [8], and two subclasses of P-ERVs, the polytropic murine viruses (Pmvs) and modified polytropic murine viruses (Mpmvs) [9], none of which have infectious virus counterparts, although they can contribute to the generation of intersubgroup recombinant viruses that have the distinctive P-MLV host range [10–13].

The classical inbred strains were derived from mice provided to research laboratories at the turn of the last century by fancy mouse hobbyists. These fancy mice, bred for centuries as pets and for show, were produced by interbreeding wild house mice of three M. musculus subspecies (castaneus, musculus, domesticus) [14]. These classical laboratory strains and their fancy mouse progenitors have been shown to be intersubspecific mosaics [15, 16].

All 3 M. musculus subspecies carry MLV ERVs, but the distribution of ERV subtypes in wild house mice is segregated by geography and subspecies [17]. M. m. domesticus of Western Europe carries only P-MLV ERVs, whereas E-MLV ERVs and X-MLV ERVs are found only in M. m. castaneus and M. m. musculus in eastern Europe and Asia, and in their naturally occurring Japanese hybrid, M. m. molossinus [17–19]. The fancy mouse intersubspecies hybrids and the inbred laboratory strains ultimately acquired all three MLV subtypes, often in the absence of the protective antiviral host factors found in virus-infected wild mouse populations [20]. As a result, fancy mice were afflicted with naturally occurring tumors and were formally studied as mammalian models of cancer as far back as the turn of the last century [21].

Inbred mouse strains have been especially useful in genetic studies and as models of human disease. After their introduction into the laboratory, mice showing a high incidence of spontaneous disease were deliberately inbred to generate, for example, the “high leukemia” strains such as AKR, as well as other models of human disease including strains having high incidence of mammary tumors (C3H) [22], lupus-like autoimmune disorders (NZB) [23], accelerated senescence (SAMP) [24] and diabetes (NOD) [25]. Retroviruses were investigated as causative agents in many of these naturally occurring diseases [26] and MLVs have a well-documented etiological association with the induction of lymphomas [27]. Strain differences in lymphoma incidence have long been attributed to the presence of MLVs and host factors that affect their replication, but these factors have been evaluated in only a selected subset of the laboratory strains, largely through classical genetic crosses [28].

We previously developed oligonucleotide primer sets specific for 43 X/P-ERVs in the sequenced C57BL/6 genome (here termed B6) to trace individual MLV ERVs to their wild mouse progenitors [29]. Here we expanded our analysis of the inbred strains to formally detail the distribution patterns of 45 Pmvs, Mpmvs, and Xmvs in 58 inbred strains and to screen the recently assembled sequenced genomes of 11 of these strains [30] for expected as well as novel MLV ERVs. We describe the ERV content of strains subgrouped in two ways: first, on the basis of their common origins, known breeding histories and genetic differences [15], and second, on the basis of their documented incidence of hematopoietic neoplasms. We show that all 45 of the X/P-ERVs found in the B6 genome are found in other strains, but that each strain has a unique complement of these ERVs, information that should be useful in annotating these repetitive and insertionally polymorphic ERVs in the sequenced genomes of the various mouse strains and species of wild mice. The presence of individual ERVs previously implicated in the generation of P-MLV recombinants [13] was compared with strain disease profiles as was the distribution of alleles of the mouse Fv1 gene which has a major role in restricting MLV spread [31]. High leukemia incidence was linked to the presence of specific expressed E- and X-ERVs and to the permissive Fv1n allele; low leukemia strains generally lack active MLVs and/or carry the restrictive Fv1 alleles.

Materials and methods

Mouse DNAs

DNAs from 41 strains were purchased as DNAs or isolated from mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). DNAs from ten senescence-accelerated (SAM) mice were prepared from tissues obtained from Richard Carp (NY State Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities, NYC, NY). DNAs from six strains (F/St, SIM.R, SIM, DBA/2N, AKR/N and NFS/N) were isolated from livers of mice maintained in our laboratory. The two SIM strains were originally obtained from D. Axelrad [32].

Virus restriction by Fv1

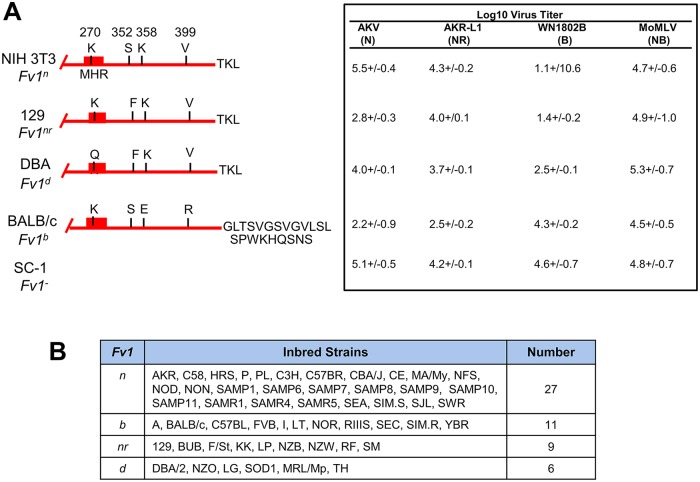

Susceptibility to Fv1-sensitive MLVs was assessed using the UV-XC overlay assay as described previously [33]. The tested cells included NIH 3T3 (Fv1n), BALB 3T3 (Fv1b) and fully permissive SC-1 cells [34] originally obtained from Dr. J. Hartley (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD) and fibroblast lines developed in our laboratory from 129 (Fv1nr) and DBA (Fv1d) mouse embryos. Prototype viruses sensitive or resistant to Fv1 alleles included AKV (N-tropic), WN1802B (B-tropic), AKR-L1 (NR-tropic) and Moloney MLV (MoMLV, NB-tropic), all of which were originally obtained from Dr. J. Hartley.

Distribution of MLV ERVs in inbred strains

Primer pairs were previously designed for 19 Pmvs, 13 Xmvs and 12 Mpmvs to generate diagnostic 3’ and 5’ cell-virus junction fragments and to identify the empty pre-integration sites and possible solo LTRs [29, 35]. Primers flanking an additional Xmv, Xmv16, were: Xmv16F1, 5’-CTCATCTCTGGGTCTTGGTCC; Xmv16R2, 5’-CTCAGTCTACATTCAGCCTTCC.

Strains not previously assessed for Emvs were typed by PCR using AKV E-MLV specific env primers: EcoF: 5’-CGAGAAACGGTGTGGGCAATAAC and EcoR: 5’-GGTTGCCTGGTCTGAGGTTAGATTGTTGCTTACTGTGATG.

40 of the 58 strains had been characterized with single nucleotide pairs and variable intensity oligonucleotides to produce a high-density genotyped dataset [36]. The resulting high-resolution genetic maps were used to define phylogenetic relationships and subspecific origins [37]. We used this dataset, available through the Mouse Phylogeny Viewer (MPV) at the University of North Carolina (http://msub.csbio.unc.edu) [36, 38], to examine the genomic segments surrounding each ERV integration site across the 40 strains, and to identify their wild mouse subspecific origins and their association with shared haplotype segments. This analysis used ERV chromosome coordinates from the NCBI37/mm9 reference assembly identified by BLAT searches [39] for each of the 45 MLV ERVs using the UCSC Genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu).

Draft genome sequences for 11 of the 58 strains have been produced [30]. All 11 were screened for MLV proviruses related to known and novel Emvs, Pmvs, Mpmvs, and 4 subtypes of Xmvs, and for sequences that flank the B6 MLV ERVs. Screens used BLASTn [39] at NCBI or the BLAST/BLAT tool on the Ensembl website [40] (https://useast.ensembl.org/Mus_musculus/Tools/Blast?db=core).

Sequencing of selected insertion sites and Fv1

Pre-integration ERV sites with larger than expected sizes were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced.

Fv1 was amplified from mouse genomic DNAs using primers from Fv1b (GenBank No. X97719): 5’-AGATGAATTTCCCACGTGC, 5’-CATCTATACTATCTTGGTGAG. These primers generate an Fv1b product of 2.5 kb and products of 1.3 kb from strains carrying Fv1n, Fv1nr and Fv1d. Fv1 products from 43 inbred strains were cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO before sequencing.

Sequences were deposited in GenBank for 3 strain-specific insertion sites carrying solo LTRs (MH479985-7) and for Fv1d (MH479988). Identical sequences for Fv1d were identified in DNAs from substrains DBA/2J and DBA/2N, and in strains NZO/HlLtJ, MRL/MpJ, TALLYHO/JnJ, SOD1/EiJ and LG/J.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health and procedures were in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under the NIAID-approved animal study protocol LMM1, which was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eight of the 58 mouse DNAs and two mouse embryo fibroblast lines were produced under this protocol from mice euthanized by CO2 inhalation in accordance with Animal Research Advisory Committee guidelines. Three mouse DNAs were isolated from mouse livers in the early 1980s, prior to the establishment of any Animal Care and Use Committee and the rest of the DNAs were purchased or isolated from livers provided by outside sources named above.

Results and discussion

Distribution of X/P-MLV ERVs in 58 laboratory strains

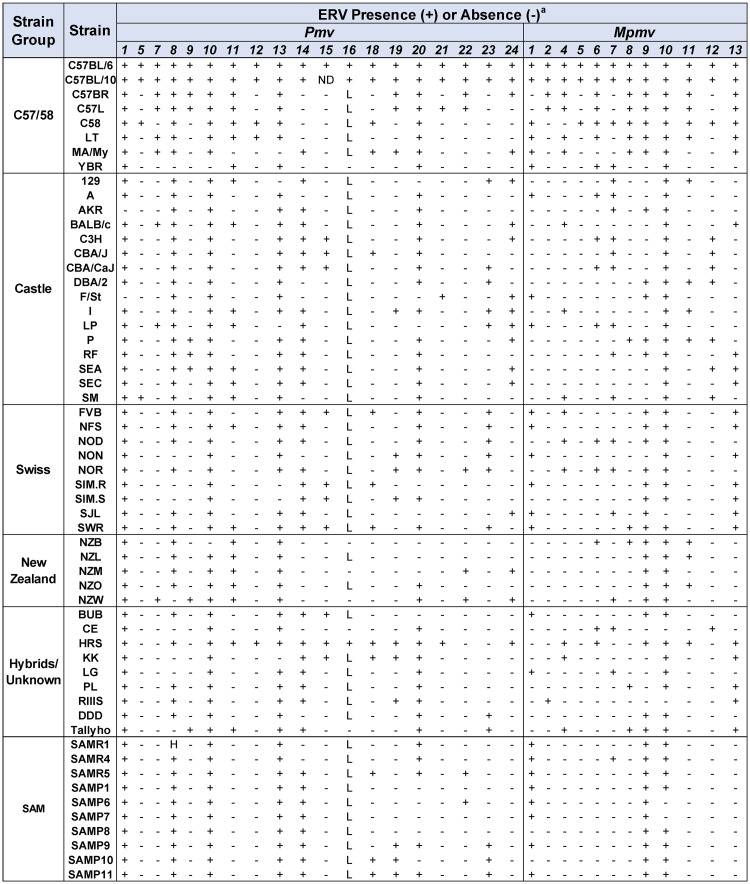

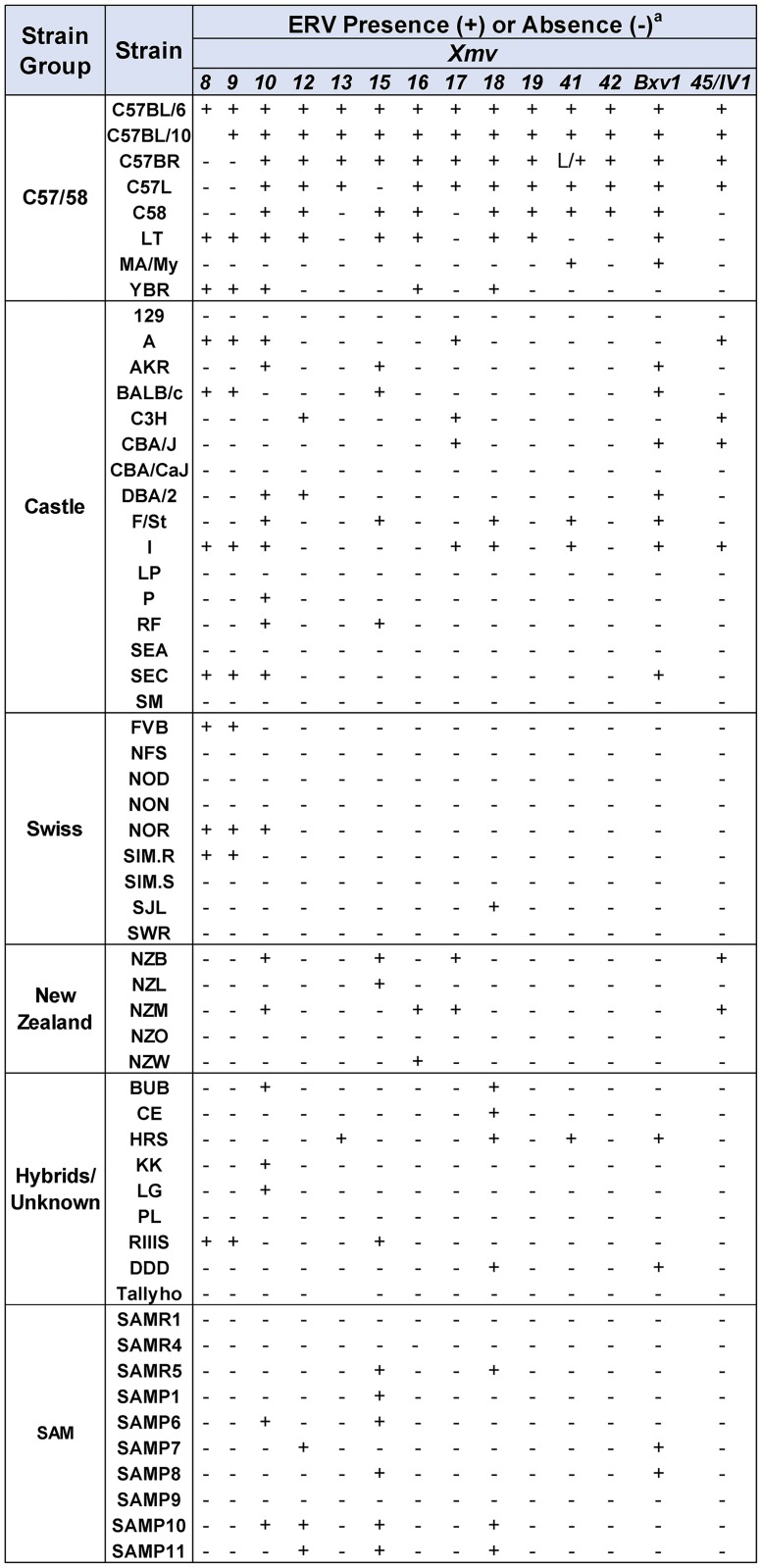

Our 58 mouse strain DNA panel (Figs 1 and 2) includes six sets of strains related by their origins and breeding histories: eight C57/58 strains that derive from a fancy mouse breeding set of three mice provided by hobbyist Abbie Lathrop to C.C. Little, 32 strains from colonies established by William Ernest Castle that also included breeders from Lathrop [14], nine Swiss mouse-derived strains, and nine unrelated strains derived from other, often poorly documented, sources [15]. The five New Zealand strains and ten strains of senescence accelerated mice (SAM) have been grouped with the Castle mice [15], but are discussed separately here.

Fig 1. Classical mouse strains typed for 31 P-MLVs and grouped according to known breeding history.

Substrains AKR/N and AKR/J, and substrains C57BL/6 and C57BL/10 carry identical ERVs, whereas the two CBA substrains differ for six ERVs likely due to genetic contamination [37]. The SIM.R Fv1b congenic differs from its SIM progenitor in the presence of 6 ERVs found in the Fv1b donor strain, three of which are linked to Fv1. a+, presence; -, absence; L, solo LTR; H, heterozygous; ND, not done.

Fig 2. Classical mouse strains typed for 14 Xmvs and grouped according to known breeding history.

a+, presence; -, absence; L, solo LTR.

All mouse DNAs were screened by PCR for 45 X/P-ERVs present in the sequenced B6 genome [41] using ERV insertion-specific primer pairs [29]. These 45 ERVs include 14 Xmvs, 19 Pmvs, and 12 Mpmvs. Each DNA could be unambiguously typed for each ERV because, with a few exceptions described below, the primer sets for each ERV either produced expected cell-virus junction fragments or empty locus products (Fig 3 and S1 Fig). None of the 45 B6 ERVs is unique to B6, and each mouse strain carries a different subset of these ERVs (Figs 1 and 2).

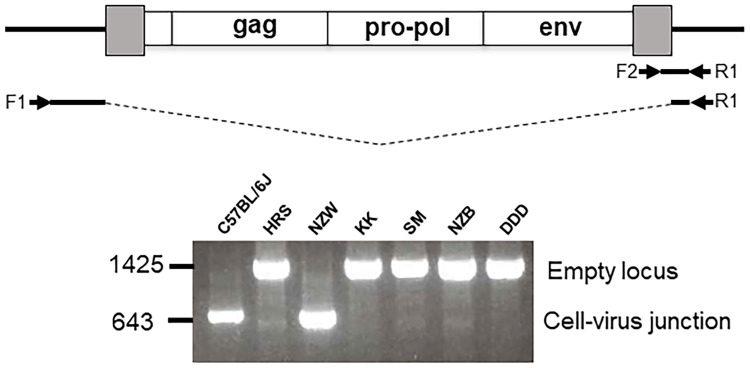

Fig 3. Detection of a representative ERV, Pmv7, in 7 inbred strains.

At the top is a diagram of the provirus and cellular flanks with arrows showing positions of 3 primers and the expected products for mice with and without the Pmv7 insertion. At the bottom are PCR test results for 7 strains using the three primers.

The distribution of each ERV varies widely among the 58 strains. Although all strains carry at least six of the 31 P-ERVs, some individual ERVs are found in as few as three strains (Mpmv5) or in as many as 55 of the 57 strains (Pmv1, Pmv10) (Fig 1). Some of the distributional differences are lineage group-specific. Thus, three ERVs are restricted to the C57/58 strains (Xmv19, Xmv42, Mpmv5), and two (Xmv12, Pmv5), were found only in the two sets of Lathrop-derived strains (C57/58, Castle). Ten ERVs were found in all six strain groups, including one Xmv, six Pmvs, and three Mpmvs, reflecting the intersubspecies mosaicism of inbred mice as well as possible cross-contamination due to inadvertent interbreeding [37]. 16 strains lack all 14 of the B6 Xmvs, and this absence is particularly notable in Swiss-derived strains, which is not surprising for mice derived from Western European stocks that lack X-MLVs [17].

All 14 Xmvs consistently map to MVP-defined genomic blocks in the sequenced mouse genome that are derived from M. m. musculus as shown previously for 13 Xmvs in a subset of these strains [29, 35]. All 31 P-ERV insertion sites map to segments of the mouse genome derived from M. m. domesticus. As shown for six representative ERVs in Fig 4, all P-ERVs also map to conserved haplotype blocks that distinguish the inbred strains, and all strains sharing ERV-linked haplotype blocks carry the relevant ERV. This consistent correlation of ERVs with subspecies and haplotype blocks shows that none are recent insertions and indicates that all predate the origins of laboratory mice. This resource should provide reliable predictions of ERV distributions in strains not typed by PCR that are included in the MPV dataset.

Fig 4. Wild mouse origins and haplotype identities for six ERVs.

The horizontal tracks represent 2–4 megabase chromosome segments surrounding six specific ERV integration sites. ERVs and their genome locations are listed on the left and PCR typing data is on the right. The map locations for each ERV are marked by a vertical black line. Blocks of shared haplotypes are indicated in multiple colors; additional tracks for the three Xmvs show subspecies-specific blocks originating from M. m. domesticus in blue and from M. m. musculus in red.

Inbred strains carry MLV ERVs not found in B6 [42, 43]. We searched the recently reported draft genome assemblies of 11 additional inbred strains [30] for MLV ERVs to support our PCR results and to identify ERVs that do not have B6 orthologs. All 11 of these sequenced and assembled strains (129, A, AKR, BALB/c, C3H/He, CBA, DBA/2, FVB, LP, NOD, NZO) were included in our PCR-typed panel. Not one full-length MLV ERV was identified in any of these 11 genomes despite the fact that eight of these strains are known to carry MLV ERVs capable of producing infectious virus constitutively or after induction (S1 Table). Southern blotting has identified specific Emvs in eight of the 11 genomes, four of which carry the same one, Emv1, and seven of these eight strains have been shown to produce infectious E-MLV (reviewed in [1]) (S1 Table). The virus-producing Bxv1 Xmv is carried by four of the newly assembled genomes. All of these previously mapped active ERVs were identified at the predicted sites in the relevant assemblies except for two of the three AKR Emvs, Emv13 and Emv14. The previously unmapped Emv of LP mice, Emv5, [6] was positioned on Chr 9:17903062–17911495. All of these identified proviruses have substantial sequencing gaps and some also had duplications, insertions or rearrangements (S2 Fig). Screens of these assemblies for other Pmvs, Mpmvs, and Xmv also failed to identify any of the full-length or near full-length B6 ERVs determined to be present by PCR. Additional proviruses with no B6 orthologs were found in the 11 genomes, but all were also highly deleted, and their strain distributions could not be reliably determined. These results underscore the difficulty in reconstructing multicopy, insertionally polymorphic and sequence divergent ERVs in genome assemblies.

Senescence-Accelerated Mouse (SAM) strains

The SAM strains originated from the inadvertent mating of AKR/J mice to mice of an unidentified strain or strains [24]. Because some of these animals showed early aging phenotypes, multiple inbred strains were developed from these mice, some of which were SAM-prone (SAMP) and some SAM-resistant (SAMR). The SAMP mice show a variety of early aging phenotypes such as activity loss, hair loss, and senile amyloidosis [44]. Average lifespans differ for SAMP (9.7 months) and SAMR (13.3 months) strains [45]. Like their AKR progenitor, SAM mice all carry Emvs, including the active AKR-derived Emv11, and most strains produce E-MLVs and some develop lymphomas [46]. E-MLVs have been linked to at least one aging phenotype, greying with age [47], but the individual Emvs in SAM strains cannot be linked to any specific aging phenotype [46].

We typed ten SAM strains by PCR for X/P-MLV ERVs (Figs 1 and 2). All 12 X/P-ERVs found in AKR were identified in one or more of the SAM strains, but seven ERVs not found in AKR were identified in the SAM strains (Xmv12,18; Pmv1,18,19,23; Mpmv1). The other progenitor(s) of the SAM strains have not been identified, but the only strain in our panel that carries all seven of these ERVs is B6. However, the fact that other gene mutations identified in SAMP strains are absent in C57BL [48] suggests that the unknown SAM progenitor is either a strain not included in the present analysis, or that there are multiple SAM progenitors.

Solo LTRs (long terminal repeats)

Solo LTRs are generated by homologous recombination between ERV LTRs leading to excision of the intervening viral coding sequences. Such major deletions between terminal repeats were initially identified in the transposable elements found in yeast, E. coli and Drosophila [49–51], and were first described for MLVs in infected rat cells [52]. Solo LTRs derived from MLV ERVs were first detected for Emv3 in DBA mice; this deletion was easily identified because it causes reversion of the dilute coat color mutation [53].

The number of solo LTRs relative to the number of full length viruses tends to be greater for more ancient ERVs suggesting progressive loss of coding sequences over time [43, 54, 55], but there is also evidence that solo LTRs are most frequently generated at or soon after endogenization and that such deletions decline with time as LTR sequences diverge [56]. In the course of this analysis, we identified five ERVs that produced empty locus amplicons that are ~500 bp larger than expected. Two of these larger amplicons have unrelated genomic inserts, but three contain solo LTRs (Fig 5), two of which correspond to the LTRs of the full-length ERV found at those sites in B6 mice.

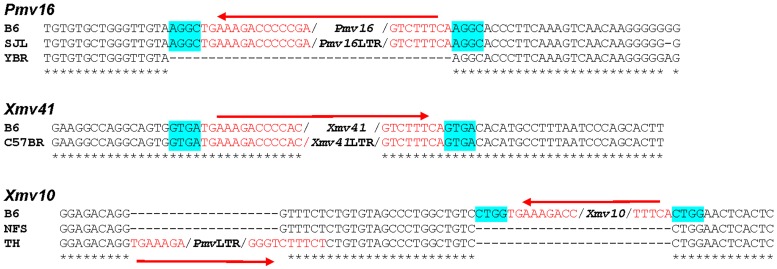

Fig 5. Solo LTRs at insertion sites of Pmv16, Xmv41 and Xmv10.

ERV sequences are in red. Flanking sequences of Pmv16 and Xmv41 show target site duplications, highlighted in blue, and these LTRs are at the same sites as the corresponding ERV in B6 mice. There is a Pmv-like solo LTR adjacent to the Xmv10 site in TH mice; NFS is representative of strains that lack this LTR and Xmv10.

Pmv16 is found as a full-length provirus in B6, C57BL/10 and only one other strain, HRS (Figs 1 and 5). Six strains, such as YBR, carry the empty pre-integration site. The remaining 48 strains all carry a Pmv16 solo LTR, shown for SJL. The prevalence of this deletion in all six strain groups indicates this solo LTR was acquired prior to the development of the inbred strains.

A second solo LTR, for Xmv41, was identified in only one strain, C57BR (Figs 2 and 5), but this deletion was found in only one of two C57BR DNAs tested, while the second sample produced the diagnostic PCR fragment for the empty locus. These two C57BR DNAs were prepared 30 years apart and otherwise showed the same typing results for other ERVs. The limited distribution of this solo LTR indicates that it is a recent, strain-specific deletion.

A third solo LTR was found using primers flanking the Xmv10 insertion (Fig 5). This LTR was identified in two strains, MA/My and TH, strains that have no documented genealogical relationship [15]. 34 strains have the pre-integration site, shown for NFS (Figs 2 and 3). The sequence of this solo LTR, however, shows it is not derived from Xmv10, but is Pmv-like. This LTR is in reverse orientation relative to the Xmv10 provirus, is inserted 19 bp from the Xmv10 insertion site and overlaps the B6 reference sequence at its 3’ end accounting for the absence of a target site duplication (Fig 5). This solo LTR is thus a deletion of a Pmv not found in B6 and not preserved as a full-length provirus or solo LTR in any of the other strains.

Disease links to specific ERVs and Fv1 variants

Hundreds of individual inbred strains have been monitored for genetic and phenotypic variations including differences in strain lifespans, common genetic disorders and susceptibility to disease. We compiled the available data on the incidence of naturally occurring hematopoietic neoplasms, including T cell and non-T cell lymphomas as reported in the strain descriptions in the Mouse Genome Database [57] and in multiple studies and compilations that focused on specific strains or strain sets [23, 44, 58–65]. A 36 strain subset of our 58 strain panel had been typed for spontaneous lymphoma and also carry Emvs, expression of which is a necessary precondition for spontaneous lymphomagenesis. These 36 strains (Table 1) were grouped as high or as moderate-low disease incidence based on disease incidence, type and latency. Eight strains show a high incidence of T-cell lymphomas with early onset. 28 strains show low incidence or develop late onset neoplasms that are mostly B-cell, myeloid or reticular cell. The rest of our original 58 strain panel either do not carry Emvs and have low disease, or the incidence of hematopoietic neoplasms has not been reported.

Table 1. Characterization of inbred strains for naturally occurring hematopoietic neoplasms.

| Disease Incidence, Latency, Typea | Strain | Emvs | X/P-ERVs Involved in P-MLV Generationd | Fv1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locusb | Expressionc | Pmvs | Xmvs | ||||||||||

| High, Early, T Cell | AKR | Emv11-14 | SpH | 13 | 20 | 10 | Bxv1 | n | |||||

| C58 | 4–6 Emvs | SpH | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 10 | Bxv1 | n | ||||

| HRS | Emv1,3 | SpH | 1 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 20 | Bxv1 | n | ||||

| P | Emv3 | NT | 1 | 20 | 10 | 13 | n | ||||||

| PL | 3–4 Emvs | NT | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SAMP7 | Emv11+1Emv | SpH | 1 | 13 | Bxv1 | n | |||||||

| SAMP8 | Emv11+7Emvs | SpH | 1 | 13 | Bxv1 | n | |||||||

| SAMP9 | Emv11+2Emvs | SpH | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| Moderate, Late, Low, T Cell or Non-T Cell | C3H | Emv1 | Ind | 1 | 13 | 15 | 20 | IV1 | n | ||||

| C57BR | Emv2 | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 10 | Bxv1 | IV1 | n | |||

| CBA/J | Emv1 | Ag+ | 1 | 13 | 15 | 20 | 13 | IV1 | n | ||||

| MA/My | Emv8,9 | (Ind),Ag+ | 1 | 20 | Bxv1 | n | |||||||

| NOD | Emv30 | SpL | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SAMP1 | Emv11+2Emvs | SpH | 1 | 13 | n | ||||||||

| SAMP10 | Emv11+5Emvs | SpH | 1 | 13 | 10 | n | |||||||

| SAMR5 | 3Emvs | - | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SEA | Emv1,3 | SpL,Ind | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | n | ||||||

| SJL | Emv9,10 | SpL,Ind,Ag+ | 1 | 13 | n | ||||||||

| NON | Emv30 | SpL | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SAMP6 | 2Emvs | - | 1 | 13 | 10 | n | |||||||

| SAMP11 | Emv11 | SpH | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SAMR1 | 2Emvs | SpL | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| SAMR4 | 2Emvs | SpL | 1 | 13 | 20 | n | |||||||

| F/St | Emv+ | SpH | 13 | 10 | Bxv1 | nr | |||||||

| LP | Emv5 | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | nr | |||||||

| KK | Emv+ | NT | 1 | 15 | 20 | nr | |||||||

| NZW | Emv+ | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | nr | ||||||

| RF | Emv1,2 | Ag+ | 1 | 13 | 20 | 10 | nr | ||||||

| SM | Emv1 | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | nr | ||||||

| DBA/2 | Emv3 | SpL | 1 | 13 | 20 | 10 | Bxv1 | d | |||||

| NZO | Emv+ | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | d | ||||||

| A | Emv1 | Ind,Ag+ | 1 | 13 | 20 | 10 | IV1 | b | |||||

| BALB/c | Emv1 | Ind,Ag+ | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | Bxv1 | b | |||||

| C57BL | Emv2 | (Ind) | 1 | 11 | 13 | 15 | 20 | 10 | Bxv1 | IV1 | b | ||

| I | Emv1,3 | Ag- | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 10 | 13 | Bxv1 | IV1 | b | ||

| YBR | Emv+ | NT | 1 | 11 | 13 | 20 | 10 | b | |||||

bMany Emvs have assigned numbers [6, 46]; Emv+, strains carrying uncharacterized PCR-detected Emv env sequences.

cExpression is identified as: SpH, spontaneous high; SpL, spontaneous low; Ag+, viral antigen positive; Ind, inducible by iododeoxyuridine; -, no expression; NT, not tested.

dThe X/P-MLV ERVs that contribute to P-MLVs were previously identified [13].

E-MLV viremia in mice that develop spontaneous lymphomas is followed by generation of P-MLVs having altered host range and enhanced virulence [13, 66, 67], and insertional mutagenesis by those P-MLVs. We examined the 36 strains for X/P-ERVs previously linked to P-MLV generation [13], and also typed them for variants of Fv1, a host gene that restricts replication of E- and P-MLVs and virus-induced disease [31, 68] (Table 1 and Fig 6).

Fig 6. Fv1 variants in classical inbred strains.

A) The diagrams on the left identify protein sequence differences among the 4 inbred strain alleles. On the right are virus titers for E-MLVs sensitive to Fv1 restriction as determined for NIH3T3 (Fv1n), 129 (Fv1nr), DBA (Fv1d), BALB3T3 (Fv1b), and the wild mouse derived SC-1 (Fv1-). Log10 virus titers were determined by the UV-XC overlay assay; each cell line was tested 3–8 times. B) Inbred strains sequenced for Fv1 alleles. Identical Fv1d sequences were found for substrains DBA/2N and DBA/2J.

Fv1 allelic variation

There are four Fv1 variants in inbred mice which restrict different subsets of mouse-tropic MLVs [69–71] (Fig 6A). E-MLVs from inbred strains are N-tropic, that is, not restricted by the Fv1n allele. The b, nr and d alleles of Fv1 restrict all or some N-tropic viruses (Fig 6A). PCR typing can identify Fv1b due to a C-terminal 1.2kb insertion [72], but cannot distinguish the identically sized Fv1n, -nr and -d amplicons. Because only a handful of strains had been previously sequenced for Fv1 alleles, we sequenced the Fv1 genes in the strain subset typed for disease incidence and in additional strains chosen on the basis of their breeding histories. Fv1nr [73] was found in a total of nine strains (Fig 6B), and Fv1d [71] in six strains, including two strains not otherwise included in this study, SOD1/EiJ and MRL/MpJ. Our Fv1d sequence, which differs from that in a previous report [74], resembles Fv1nr in having the S352F substitution responsible for restricting some N-tropic viruses [75], but also contains a K270Q substitution, a site that is under strong positive selection [76] and has been linked to restriction of retroviruses other than MLVs [74]. Because only one Fv1b gene, from B6, had been sequenced, we also sequenced the Fv1 genes in five other strains typed by PCR as Fv1b (A, BALB/c, I, LT, YBR) [77] (Fig 6B); all five had sequences identical to the Fv1b B6 prototype.

Comparisons of Fv1 allelic variation and lymphomagenesis showed that all 13 of the strains carrying one of the three restrictive Fv1 alleles (Fv1b, nr, d), show moderate-low disease incidence, whereas all eight of the high leukemia strains carry Fv1n.

Active ERVs

The association between spontaneous lymphomagenesis and E-MLV production is clear for early onset thymomas, studied in strains like AKR or HRS. This association has also been demonstrated for late onset B-cell and myeloid leukemias through analysis of NFS.E-MLV+ congenics, AKXD RI strains and CFW Swiss mice carrying E-MLVs [78–80].

All 36 of the strains in Table 1 carry Emvs, but virus production patterns vary significantly. Six of the eight high leukemic strains have been typed for virus production and are all early, high producers. The majority of the low-moderate strains carry Emvs that show low, inducible and/or late virus production. A few moderate-low disease strains like SAMP1, 10, and 11, and F/St, however, show that a relatively high level of E-MLV expression is not sufficient for high disease incidence.

Infectious recombinant P-MLVs can potentially be generated in any mouse with replicating E-MLVs, but P-MLVs judged to be lymphomagenic by the AKR acceleration test [81], have only been isolated from the high leukemic strains [66]. Low disease incidence strains produce less complex P-MLV recombinants [12, 13] that are not lymphomagenic [66]. One factor that might explain the differences between pathogenic and nonpathogenic P-MLVs may be the strain differences in the complement of X/P-ERVs that contribute to the generation of these recombinants.

Our previous analysis of infectious P-MLVs identified segments acquired by recombination that showed homology to four Xmvs (Bxv1, Xmv10,13, IV1), and five Pmvs (Pmv1,11,13,15,20) [13]. Six of these nine ERVs were implicated as likely progenitors of multiple independently isolated recombinant viruses suggesting these ERVs are especially active as recombination partners. The strain distribution of most of these ERVs in our mouse DNA panel is, however, not skewed toward high leukemic strains, with one exception (Table 1). Bxv1 is an expressed X-ERV that is activated by immune stimulation [82]. Bxv1 is present in only 25% of the low-moderate disease strains but is carried by 63% of the high strains. Most of the altered LTRs in pathogenic P-MLVs result from recombination with Bxv1 [13] as also shown by restriction mapping and targeted sequencing of AKR mouse P-MLVs [83–85]. However, pathogenic LTRs can also be produced by mutation in mice that lack Bxv1 [13, 86], indicating that Bxv1 is important but not necessary for the generation of disease-inducing viruses.

The failure to identify specific P-ERVs linked to disease is likely due to several factors. First, late-expressing Emvs may not provide enough time for the necessary multiple rounds of recombination needed to produce complex lymphomagenic recombinants. Second, acquisition of Pmv env sequences is necessary for P-MLV host range, but is not sufficient for the generation of pathogenic P-MLVs, and the segment of the TMenv linked to lymphomagenesis [13] can derive from multiple P-ERVs. Third, inbred strains carry P-ERVs not found in the reference low-incidence B6 mouse genome [42, 43]. Such copies in the high disease strains but not in B6 may be more likely to produce pathogenic P-MLVs, but their identification awaits the completed sequencing of multiple classical strains and the accurate annotation of their ERV content.

Conclusions

Here we characterized 58 strains to describe the distributional patterns of 45 MLV ERVs that can be present, absent or have undergone deletion to produce solo LTRs, and for functional variants of the host Fv1 gene that inhibit MLV spread. This study provides insight into the host factors responsible for strain differences in naturally occurring virus-induced diseases and helps characterize the ERV content of the various classical inbred strain genomes. The distribution of individual ERVs often reflects common strain ancestry, and we identified several ERVs alternatively present as full-length MLVs or deleted solo LTRs. This dataset adds to our understanding of strain relationships and the disease implications of ERV content, and should assist in annotating genomic sequences of strains that differ from the framework B6 sequence in ERV content. While first draft sequencing of additional mouse strains has been completed, the incomplete annotation of their MLV ERV content illustrates the difficulty in reconstructing the sequences of repetitive and insertionally polymorphic ERVs. As shown here and previously [87], even ERVs capable of producing infectious virus have significant sequencing gaps in newly produced assemblies.

Classical inbred strains have long been used to identify genetic differences controlling susceptibility to lifespan-shortening diseases. Our data identified several patterns related to the inheritance and expression of functional MLV ERVs. First, restrictive alleles of Fv1 are linked to lower leukemia incidence. Second, highly expressed Emvs are necessary but not sufficient for early lymphomagenesis. Third, the nonecotropic B6 ERVs previously identified as likely progenitors of pathogenic recombinants are not overrepresented in the high leukemia strains, with the exception of Bxv1 which is a common contributor to the generation of pathogenic viruses [13, 85]. This suggests that high leukemia strains may carry additional P-ERVs that can help create pathogenic recombinants.

Supporting information

Lane 1, markers (Invitrogen Trackit 1Kb Plus DNA Ladder, Cat No. 10488085); Lanes 2–8, products of an unrelated PCR; Lanes 9–15, empty locus and cell-virus junction fragments for Pmv7.

(PPTX)

At the top is a diagram of the MLV proviral genome identifying locations of the LTRs with U3-R-U5 structures and gag, pol and env genes. Proviruses are identified on the right; Emv1 and Bxv1 are each present in multiple strains. Thick lines are viral sequences. Dotted lines are sequencing gaps. Red lines mark duplications. An inserted sequence is in green. Blue lines are misplaced segments with assembly positions shown by arrows. Brown lines are unplaced sequences.

(PPTX)

Listed ERVs are constitutively expressed or inducible and are found in eight of the 11 genomes [88–98]. Three assembled genomes (129, FVB, NZO) have no full-length MLV ERVs capable of producing virus. Emv1-3 have small defects correctable by mutation or recombination.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Alicia Buckler-White for her technical assistance in DNA sequencing.

Data Availability

New DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MH479985-7 and MH479988. All other data are contained within the manuscript and in supporting files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by funding to CAK, Grant: AI000300-37, Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD, https://www.niaid.nih.gov/. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kozak CA. Origins of the endogenous and infectious laboratory mouse gammaretroviruses. Viruses. 2015;7:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oie HK, Russell EK, Dotson JH, Rhoads JM, Gazdar AF. Host range properties of murine xenotropic and ecotropic type-C viruses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1976;56:423–6. 10.1093/jnci/56.2.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan Y, Liu Q, Wollenberg K, Martin C, Buckler-White A, Kozak CA. Evolution of functional and sequence variants of the mammalian XPR1 receptor for mouse xenotropic gammaretroviruses and the human-derived XMRV. J Virol. 2010;84:11970–80. Epub 2010/09/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albritton LM, Tseng L, Scadden D, Cunningham JM. A putative murine ecotropic retrovirus receptor gene encodes a multiple membrane-spanning protein and confers susceptibility to virus infection. Cell. 1989;57(4):659–66. Epub 1989/05/19. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tailor CS, Nouri A, Lee CG, Kozak C, Kabat D. Cloning and characterization of a cell surface receptor for xenotropic and polytropic murine leukemia viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(3):927–32. Epub 1999/02/03. 10.1073/pnas.96.3.927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Taylor BA, Lee BK. Organization, distribution, and stability of endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia virus DNA sequences in chromosomes of Mus musculus. J Virol. 1982;43(1):26–36. Epub 1982/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frankel WN, Stoye JP, Taylor BA, Coffin JM. Genetic analysis of endogenous xenotropic murine leukemia viruses: association with two common mouse mutations and the viral restriction locus Fv-1. J Virol. 1989;63(4):1763–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozak CA. Origins of the endogenous and infectious laboratory mouse gammaretroviruses. Viruses. 2014;7(1):1–26. 10.3390/v7010001 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoye JP, Coffin JM. The four classes of endogenous murine leukemia virus: structural relationships and potential for recombination. J Virol. 1987;61(9):2659–69. Epub 1987/09/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chattopadhyay SK, Cloyd MW, Linemeyer DL, Lander MR, Rands E, Lowy DR. Cellular origin and role of mink cell focus-forming viruses in murine thymic lymphomas. Nature. 1982;295(5844):25–31. Epub 1982/01/07. 10.1038/295025a0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan AS, Rowe WP, Martin MA. Cloning of endogenous murine leukemia virus-related sequences from chromosomal DNA of BALB/c and AKR/J mice: identification of an env progenitor of AKR-247 mink cell focus-forming proviral DNA. J Virol. 1982;44(2):625–36. Epub 1982/11/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lung ML, Hartley JW, Rowe WP, Hopkins NH. Large RNase T1-resistant oligonucleotides encoding p15E and the U3 region of the long terminal repeat distinguish two biological classes of mink cell focus-forming type C viruses of inbred mice. J Virol. 1983;45(1):275–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bamunusinghe D, Liu Q, Plishka R, Dolan MA, Skorski M, Oler AJ, et al. Recombinant origins of pathogenic and nonpathogenic mouse gammaretroviruses with polytropic host range. J Virol. 2017;91(21). 10.1128/JVI.00855-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse HC III. Introduction In: Morse HC III, editor. Origins of inbred mice. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1978. p. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck JA, Lloyd S, Hafezparast M, Lennon-Pierce M, Eppig JT, Festing MFW, et al. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat Genet. 2000;24(1):23–5. 10.1038/71641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H, Bell TA, Churchill GA, Pardo-Manuel de Villena F. On the subspecific origin of the laboratory mouse. Nat Genet. 2007;39(9):1100–7. Epub 2007/07/31. 10.1038/ng2087 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozak CA, O’Neill RR. Diverse wild mouse origins of xenotropic, mink cell focus-forming, and two types of ecotropic proviral genes. J Virol. 1987;61(10):3082–8. Epub 1987/10/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yonekawa H, Moriwaki K, Gotoh O, Miyashita N, Matsushima Y, Shi L, et al. Hybrid origin of Japanese mice "Mus musculus molossinus": evidence from restriction analysis of mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biol Evol. 1988;5(1):63–78. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda H, Kato K, Kitani H, Suzuki T, Yoshida T, Inaguma Y, et al. Virological properties and nucleotide sequences of cas-E-type endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia viruses in south Asian wild mice, Mus musculus castaneus. J Virol. 2001;75(11):5049–58. ISI:000168593600012. 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5049-5058.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kozak CA. Evolution of different antiviral strategies in wild mouse populations exposed to different gammaretroviruses. Current opinion in virology. 2013;3(6):657–63. 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loeb L. Further observations on the endemic occurrence of carcinoma and on the inoculability of tumors. Univ Penn Med Bull. 1907;XX:2–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heston WE, Vlahakis G. Mammary tumors, plaques, and hyperplastic alveolar nodules in various combinations of mouse inbred strains and the different lines of the mammary tumor virus. Int J Cancer. 1971;7(1):141–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Festing MFW. Origins and characteristics of inbred strains of mice In: Lyon MF, Rastan S., Brown S.D.M., editor. Genetic variants and strains of the laboratory mouse. 2 Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 1537–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda T, Hosokawa M, Higuchi K. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM): a novel murine model of senescence. Experimental gerontology. 1997;32(1–2):105–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikutani H, Makino S. The murine autoimmune diabetes model: NOD and related strains. Adv Immunol. 1992;51:285–322. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito K, Baudino L, Kihara M, Leroy V, Vyse TJ, Evans LH, et al. Three Sgp loci act independently as well as synergistically to elevate the expression of specific endogenous retroviruses implicated in murine lupus. J Autoimmun. 2013;43:10–7. 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross L. "Spontaneous" leukemia developing in C3H mice following inoculation in infancy, with AK-leukemic extracts, or AK-embryos. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1951;76(1):27–32. Epub 1951/01/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe WP, Hartley JW. Genes affecting mink cell focus-inducing (MCF) murine leukemia virus infection and spontaneous lymphoma in AKR F1 hybrids. J Exp Med. 1983;158(2):353–64. 10.1084/jem.158.2.353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bamunusinghe D, Liu Q, Lu X, Oler A, Kozak CA. Endogenous gammaretrovirus acquisition in Mus musculus subspecies carrying functional variants of the XPR1 virus receptor. J Virol. 2013;87(17):9845–55. 10.1128/JVI.01264-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lilue J, Doran AG, Fiddes IT, Abrudan M, Armstrong J, Bennett R, et al. Sixteen diverse laboratory mouse reference genomes define strain-specific haplotypes and novel functional loci. Nat Genet. 2018;50(11):1574–83. Epub 2018/10/03. 10.1038/s41588-018-0223-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilly F. Susceptibility to two strains of Friend leukemia virus in mice. Science. 1967;155(761):461–2. Epub 1967/01/27. 10.1126/science.155.3761.461 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ware LM, Axelrad AA. Inherited resistance to N- and B-tropic murine leukemia viruses in vitro: evidence that congenic mouse strains SIM and SIM.R differ at the Fv-1 locus. Virology. 1972;50(2):339–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowe WP, Pugh WE, Hartley JW. Plaque assay techniques for murine leukemia viruses. Virology. 1970;42(4):1136–9. Epub 1970/12/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hartley JW, Rowe WP. Clonal cell lines from a feral mouse embryo which lack host-range restrictions for murine leukemia viruses. Virology. 1975;65(1):128–34. ISI:A1975AD73600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bamunusinghe D, Naghashfar Z, Buckler-White A, Plishka R, Baliji S, Liu Q, et al. Sequence diversity, intersubgroup relationships, and origins of the mouse leukemia gammaretroviruses of laboratory and wild mice. J Virol. 2016;90:4186–98. 10.1128/JVI.03186-15 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang H, Ding Y, Hutchins LN, Szatkiewicz J, Bell TA, Paigen BJ, et al. A customized and versatile high-density genotyping array for the mouse. Nat Methods. 2009;6(9):663–6. 10.1038/nmeth.1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang H, Wang JR, Didion JP, Buus RJ, Bell TA, Welsh CE, et al. Subspecific origin and haplotype diversity in the laboratory mouse. Nat Genet. 2011;43(7):648–55. 10.1038/ng.847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang JR, de Villena FP, McMillan L. Comparative analysis and visualization of multiple collinear genomes. BMC bioinformatics. 2012;13 Suppl 3:S13 10.1186/1471-2105-13-S3-S13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kent WJ. BLAT—the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12(4):656–64. 10.1101/gr.229202 Article published online before March 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zerbino DR, Achuthan P, Akanni W, Amode MR, Barrell D, Bhai J, et al. Ensembl 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D754–D61. Epub 2017/11/21. 10.1093/nar/gkx1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jern P, Stoye JP, Coffin JM. Role of APOBEC3 in genetic diversity among endogenous murine leukemia viruses. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(10):e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frankel WN, Stoye JP, Taylor BA, Coffin JM. A linkage map of endogenous murine leukemia proviruses. Genetics. 1990;124(2):221–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nellaker C, Keane TM, Yalcin B, Wong K, Agam A, Belgard TG, et al. The genomic landscape shaped by selection on transposable elements across 18 mouse strains. Genome Biol. 2012;13(6):R45 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda T, Matsushita T, Kurozumi M, Takemura K, Higuchi K, Hosokawa M. Pathobiology of the senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM). Experimental gerontology. 1997;32(1–2):117–27. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takeda T, Hosokawa M, Takeshita S, Irino M, Higuchi K, Matsushita T, et al. A new murine model of accelerated senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 1981;17(2):183–94. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carp RI, Meeker HC, Chung R, Kozak CA, Hosokawa M, Fujisawa H. Murine leukemia virus in organs of senescence-prone and -resistant mouse strains. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123(6):575–84. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morse HC 3rd, Yetter RA, Stimpfling JH, Pitts OM, Fredrickson TN, Hartley JW. Greying with age in mice: relation to expression of murine leukemia viruses. Cell. 1985;41(2):439–48. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanisawa K, Mikami E, Fuku N, Honda Y, Honda S, Ohsawa I, et al. Exome sequencing of senescence-accelerated mice (SAM) reveals deleterious mutations in degenerative disease-causing genes. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:248 10.1186/1471-2164-14-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roeder GS, Farabaugh PJ, Chaleff DT, Fink GR. The origins of gene instability in yeast. Science. 1980;209(4463):1375–80. 10.1126/science.6251544 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacHattie LA, Jackowski JB. Physical structure and deletion effects of the chloramphenicol resistance element Tn9 in phage lambda In: Bukhari AI, A. SJ, L. AS, editors. DNA Insertion Elements, Plasmids, and Episomes. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Publications; 1977. p. 219–28. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levis R, Rubin GM. The unstable wDZL mutation of Drosophila is caused by a 13 kilobase insertion that is imprecisely excised in phenotypic revertants. Cell. 1982;30(2):543–50. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Varmus HE, Quintrell N, Ortiz S. Retroviruses as mutagens: insertion and excision of a nontransforming provirus alter expression of a resident transforming provirus. Cell. 1981;25(1):23–36. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Copeland NG, Hutchison KW, Jenkins NA. Excision of the DBA ecotropic provirus in dilute coat-color revertants of mice occurs by homologous recombination involving the viral LTRs. Cell. 1983;33(2):379–87. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belshaw R, Watson J, Katzourakis A, Howe A, Woolven-Allen J, Burt A, et al. Rate of recombinational deletion among human endogenous retroviruses. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9437–42. 10.1128/JVI.02216-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katzourakis A, Pereira V, Tristem M. Effects of recombination rate on human endogenous retrovirus fixation and persistence. J Virol. 2007;81(19):10712–7. 10.1128/JVI.00410-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gemmell P, Hein J, Katzourakis A. Phylogenetic Analysis Reveals That ERVs "Die Young" but HERV-H Is Unusually Conserved. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(6):e1004964 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blake JA, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, Richardson JE, Smith CL, Bult CJ, et al. Mouse Genome Database (MGD)-2017: community knowledge resource for the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D723–D9. 10.1093/nar/gkw1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murphy ED. Characteristic tumors In: Green EL, editor. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. New York: Dover Publications, Inc; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith GS, Walford RL, Mickey MR. Lifespan and incidence of cancer and other diseases in selected long-lived inbred mice and their F 1 hybrids. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;50(5):1195–213. 10.1093/jnci/50.5.1195 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Storer JB. Longevity and gross pathology at death in 22 inbred mouse strains. J Gerontol. 1966;21(3):404–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pattengale PK, Taylor CR. Experimental models of lymphoproliferative disease. The mouse as a model for human non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and related leukemias. Am J Pathol. 1983;113(2):237–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brayton CF, Treuting PM, Ward JM. Pathobiology of aging mice and GEM: background strains and experimental design. Vet Pathol. 2012;49(1):85–105. 10.1177/0300985811430696 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ward JM. Lymphomas and leukemias in mice. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2006;57(5–6):377–81. 10.1016/j.etp.2006.01.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nowinski RC, Old LJ, Boyse EA, de Harven E, Geering G. Group-specific viral antigens in the milk and tissues of mice naturally infected with mammary tumor virus or Gross leukemia virus. Virology. 1968;34(4):617–29. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bult CJ, Krupke DM, Begley DA, Richardson JE, Neuhauser SB, Sundberg JP, et al. Mouse Tumor Biology (MTB): a database of mouse models for human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D818–24. 10.1093/nar/gku987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cloyd MW, Hartley JW, Rowe WP. Lymphomagenicity of recombinant mink cell focus-inducing murine leukemia viruses. J Exp Med. 1980;151(3):542–52. Epub 1980/03/01. 10.1084/jem.151.3.542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Evans LH. Characterization of polytropic MuLVs from three-week-old AKR/J mice. Virology. 1986;153(1):122–36. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rowe WP, Hartley JW. Studies of genetic transmission of murine leukemia virus by AKR mice. II. Crosses with Fv-1 b strains of mice. J Exp Med. 1972;136(5):1286–301. 10.1084/jem.136.5.1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hartley JW, Rowe WP, Huebner RJ. Host-range restrictions of murine leukemia viruses in mouse embryo cell cultures. J Virol. 1970;5(2):221–5. ISI:A1970F378500016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kozak CA. Analysis of wild-derived mice for Fv-1 and Fv-2 murine leukemia virus restriction loci: a novel wild mouse Fv-1 allele responsible for lack of host range restriction. J Virol. 1985;55(2):281–5. Epub 1985/08/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kozak CA, Chakraborti A. Single amino acid changes in the murine leukemia virus capsid protein gene define the target of Fv1 resistance. Virology. 1996;225(2):300–5. ISI:A1996VV42100006. 10.1006/viro.1996.0604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Best S, LeTissier P, Towers G, Stoye JP. Positional cloning of the mouse retrovirus restriction gene Fv1. Nature. 1996;382(6594):826–9. ISI:A1996VE34700052. 10.1038/382826a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steeves R, Lilly F. Interactions between host and viral genomes in mouse leukemia. Annu Rev Genet. 1977;11:277–96. Epub 1977/01/01. 10.1146/annurev.ge.11.120177.001425 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yap MW, Colbeck E, Ellis SA, Stoye JP. Evolution of the retroviral restriction gene Fv1: inhibition of non-MLV retroviruses. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(3):e1003968 Epub 2014/03/08. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stevens A, Bock M, Ellis S, LeTissier P, Bishop KN, Yap MW, et al. Retroviral capsid determinants of Fv1 NB and NR tropism. J Virol. 2004;78(18):9592–8. 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9592-9598.2004 ISI:000223701100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yan Y, Buckler-White A, Wollenberg K, Kozak CA. Origin, antiviral function and evidence for positive selection of the gammaretrovirus restriction gene Fv1 in the genus Mus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(9):3259–63. Epub 2009/02/18. 10.1073/pnas.0900181106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baliji S, Liu Q, Kozak CA. Common inbred strains of the laboratory mouse that are susceptible to infection by mouse xenotropic gammaretroviruses and the human-derived retrovirus XMRV. J Virol. 2010;84(24):12841–9. Epub 2010/10/15. 10.1128/JVI.01863-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fredrickson TN, Morse HC 3rd, Rowe WP. Spontaneous tumors of NFS mice congenic for ecotropic murine leukemia virus induction loci. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;73(2):521–4. 10.1093/jnci/73.2.521 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gilbert DJ, Neumann PE, Taylor BA, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Susceptibility of AKXD recombinant inbred mouse strains to lymphomas. J Virol. 1993;67(4):2083–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taddesse-Heath L, Chattopadhyay SK, Dillehay DL, Lander MR, Nagashfar Z, Morse HC 3rd, et al. Lymphomas and high-level expression of murine leukemia viruses in CFW mice. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6832–7. 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6832-6837.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rudali G, Duplan JF, Latarjet R. [Latency of leukosis in Ak mice injected with leukemic alpha-cellular Ak extract]. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des seances de l’Academie des sciences. 1956;242(6):837–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sherr CJ, Lieber MM, Todaro GJ. Mixed splenocyte cultures and graft versus host reactions selectively induce an S-tropic murine type C virus. Cell. 1974;1(1):55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Quint W, Boelens W, van Wezenbeek P, Cuypers T, Maandag ER, Selten G, et al. Generation of AKR mink cell focus-forming viruses: a conserved single-copy xenotrope-like provirus provides recombinant long terminal repeat sequences. J Virol. 1984;50(2):432–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoggan MD, O’Neill RR, Kozak CA. Nonecotropic murine leukemia viruses in BALB/c and NFS/N mice: characterization of the BALB/c Bxv-1 provirus and the single NFS endogenous xenotrope. J Virol. 1986;60(3):980–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stoye JP, Moroni C, Coffin JM. Virological events leading to spontaneous AKR thymomas. J Virol. 1991;65(3):1273–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Speck NA, Renjifo B, Golemis E, Fredrickson TN, Hartley JW, Hopkins N. Mutation of the core or adjacent LVb elements of the Moloney murine leukemia virus enhancer alters disease specificity. Genes Dev. 1990;4(2):233–42. 10.1101/gad.4.2.233 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bamunusinghe D, Skorski M, Buckler-White A, Kozak CA. Xenotropic Mouse Gammaretroviruses Isolated from Pre-Leukemic Tissues Include a Recombinant. Viruses. 2018;10(8). Epub 2018/08/12. 10.3390/v10080418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kozak CA, Rowe WP. Genetic mapping of the ecotropic murine leukemia virus-inducing locus of BALB/c mouse to chromosome 5. Science. 1979;204(4388):69–71. 10.1126/science.219475 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kozak CA, Rowe WP. Genetic mapping of ecotropic murine leukemia virus-inducing loci in six inbred strains. J Exp Med. 1982;155(2):524–34. Epub 1982/02/01. 10.1084/jem.155.2.524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kozak CA, Rowe WP. Genetic mapping of xenotropic murine leukemia virus-inducing loci in five mouse strains. J Exp Med. 1980;152(1):219–28. 10.1084/jem.152.1.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Triviai I, Ziegler M, Bergholz U, Oler AJ, Stubig T, Prassolov V, et al. Endogenous retrovirus induces leukemia in a xenograft mouse model for primary myelofibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(23):8595–600. 10.1073/pnas.1401215111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee EJ, Kaminchik J, Hankins WD. Expression of xenotropic-like env RNA sequences in normal DBA/2 and NZB mouse tissues. J Virol. 1984;51(1):247–50. Epub 1984/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ihle JN, Joseph DR, Domotor JJ Jr. Genetic linkage of C3H/HeJ and BALB/c endogenous ecotropic C-type viruses to phosphoglucomutase-1 on chromosome 5. Science. 1979;204(4388):71–3. Epub 1979/04/06. 10.1126/science.219476 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rowe WP, Hartley JW, Bremner T. Genetic mapping of a murine leukemia virus-inducing locus of AKR mice. Science. 1972;178(4063):860–2. Epub 1972/11/24. 10.1126/science.178.4063.860 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nexo B, Schultz AM, Rein A, Mikkelsen T, et al. Poorly expressed endogenous ecotropic provirus of DBA/2 mice encodes a mutant Pr65gag protein that is not myristylated. J Virol. 1988;62(2):479–87. Epub 1988/02/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Freed EO, Risser R. The role of envelope glycoprotein processing in murine leukemia virus infection. J Virol. 1987;61(9):2852–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Horowitz JM, Risser R. Molecular and biological characterization of the endogenous ecotropic provirus of BALB/c mice. J Virol. 1985;56(3):798–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bedigian HG, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Salvatore K, Rodick S. Emv-13 (Akv-3): a noninducible endogenous ecotropic provirus of AKR/J mice. J Virol. 1983;46(2):490–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Lane 1, markers (Invitrogen Trackit 1Kb Plus DNA Ladder, Cat No. 10488085); Lanes 2–8, products of an unrelated PCR; Lanes 9–15, empty locus and cell-virus junction fragments for Pmv7.

(PPTX)

At the top is a diagram of the MLV proviral genome identifying locations of the LTRs with U3-R-U5 structures and gag, pol and env genes. Proviruses are identified on the right; Emv1 and Bxv1 are each present in multiple strains. Thick lines are viral sequences. Dotted lines are sequencing gaps. Red lines mark duplications. An inserted sequence is in green. Blue lines are misplaced segments with assembly positions shown by arrows. Brown lines are unplaced sequences.

(PPTX)

Listed ERVs are constitutively expressed or inducible and are found in eight of the 11 genomes [88–98]. Three assembled genomes (129, FVB, NZO) have no full-length MLV ERVs capable of producing virus. Emv1-3 have small defects correctable by mutation or recombination.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

New DNA sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MH479985-7 and MH479988. All other data are contained within the manuscript and in supporting files.